Abstract

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum. The prevalence of this disease has recently increased worldwide. However, pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis is extremely rare. A 51-year-old heterosexual male patient presented with multiple pulmonary nodules with reactive serology from the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test and positive fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing. A hematogenous metastatic malignancy was suspected and an excisional lung biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination showed only central necrosis with abscess and plasma cell infiltration, but no malignant cells. The patient reported sexual contact with a prostitute 8 weeks previously and a penile lesion 6 weeks earlier. Physical examination revealed an erythematous papular rash on the trunk. Secondary syphilis with pulmonary nodules was suspected, and benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units, was administered. Subsequently, the clinical signs of syphilis improved and the pulmonary nodules resolved. The final diagnosis was secondary syphilis with pulmonary nodular involvement.

Keywords: Syphilis, Treponema pallidum, Multiple pulmonary nodules

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by infection with the spirochete bacterium, Treponema pallidum [1]. Until the 1980s, the prevalence of syphilis decreased and remained low for nearly a decade. However, the incidence of syphilis has since then increased worldwide. In particular risk groups, the prevalence has increased by a factor of 12 over the last 5 years [2].

Acquired syphilis can be divided into primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary stages [3]. The inoculation of treponemes into tiny abrasions from sexual trauma can cause a chancre, a painless ulcer. While local immunity leads to healing of the ulcer, hematogenous dissemination of the treponemes results in secondary syphilis. Secondary syphilis is characterized by multisystem involvement: typically, a skin rash, condylomata lata, mucosal lesions, and generalized lymphadenopathy. However, pulmonary involvement in patients with secondary syphilis is extremely rare [4]. This is then followed by a latent phase and, if untreated, about 40% of patients will go on to develop the tertiary stage, characterized by gummatous, cardiovascular, and neurological involvement [1,3,5]. Pulmonary involvement is occasionally found in patients with tertiary syphilis.

Here, we report a case of secondary syphilis with pulmonary involvement in a patient presenting with multiple pulmonary nodules, initially suspected to be due to a metastatic carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old heterosexual male with no significant medical history presented with multiple pulmonary nodules on a plain chest radiograph. The nodules were detected during an evaluation for right pleuritic chest pain, fever, and myalgia that started 2 weeks earlier. The patient denied weight loss, respiratory, or gastrointestinal symptoms.

A physical examination revealed a normal body temperature, normal breath sounds, no mucosal or genitourinary lesion, but an erythematous papular rash on the trunk, right cervical, and bilateral inguinal nontender, nonmovable lymphadenopathy was noted. Laboratory tests showed no leukocytosis, normal alkaline phosphatase levels, and a normal urinary analysis. However, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, > 120 mm/hr (normal range, < 9), high sensitivity C-reactive protein, 4.8 mg/dL (normal range, < 0.3), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 73 IU/L (normal range, < 50), and alanine aminotransferase, 55 IU/L (normal range, < 50) were elevated. Carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and prostate specific antigen were within normal ranges. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing was negative.

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test was positive. A diagnosis of syphilis was suspected; fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) and VDRL titers were assessed, resulting in reactive FTA-ABS immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin G, and a 1 : 64 VDRL titer. A plain chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scan showed multiple variably sized nodules in both lungs, suggesting the possibility of a hematogenous metastatic malignancy (Fig. 1A). Screening tests for malignancy including gastrointestinal endoscopies, bronchoscopy, and CT scans of the neck, abdomen, and pelvis revealed only cervical and pancreatic lymphadenopathy. Positron emission tomography CT scanning was performed and showed hypermetabolic lesions, including the multiple pulmonary nodules, as well as the cervical and pancreatic lymph nodes, with no other organ involvement.

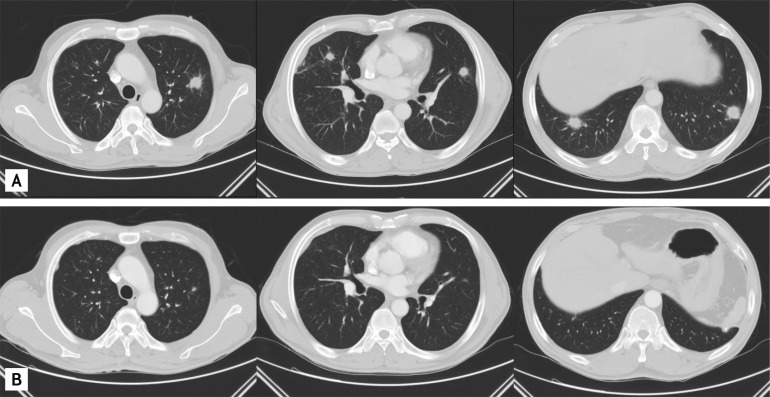

Figure 1.

(A) Chest computed tomography scan shows multiple pulmonary nodules in both lungs. (B) After benzathine penicillin G treatment, the multiple pulmonary nodules had largely disappeared 10 months later.

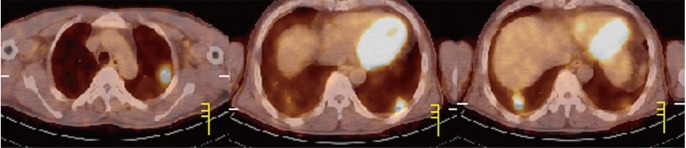

The standardized uptake values of the pulmonary nodules were from 4.37 to 5.59, strongly suggesting a malignancy (Fig. 2). A pulmonary malignancy was suspected and percutaneous needle aspirations of the pulmonary nodules and inguinal lymph nodes were performed. The cytopathological examination showed only many neutrophils and lymphocytes.

Figure 2.

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose activity in multiple pulmonary nodules.

Additional history revealed that the patient had sexual contact with a prostitute 8 weeks previously and a painless genital ulcer developed about 6 weeks earlier, which disappeared spontaneously. A generalized erythematous papular rash appeared on trunk for 1 week that did not itch. Thus, the history and laboratory findings were compatible with secondary syphilis.

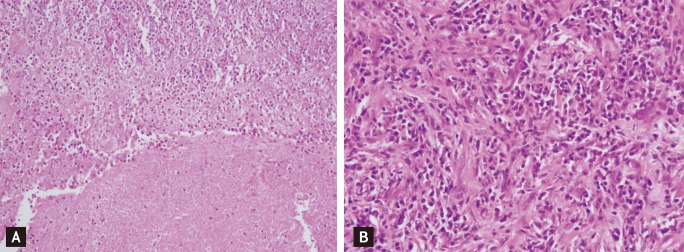

Because pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis is extremely rare and the radiological findings suggested malignancy, a pulmonary malignancy was still strongly suspected. Thus, a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical lung biopsy and cervical lymph node excisional biopsy were performed. Histopathological examination of a pulmonary nodule showed central necrosis with abscess formation and the infiltration of plasma cells and lymphocytes, with fibrosis in the periphery, but no evidence of malignancy or other specific pulmonary diseases (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Histopathological examination shows extensive central necrosis with abscess formation (A, H&E, ×200). In the periphery, massive plasma cells and scattered lymphocytes with fibrosis were seen (B, H&E, ×400).

Clinical information and laboratory data, including the history, physical findings, and the reactive FTA-ABS and VDRL, supported a clinical diagnosis of secondary syphilis with multiple pulmonary nodules. Thus, the patient was treated with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G, injected intramuscularly. The skin lesions and lymphadenopathy resolved after 2 weeks. A follow-up chest CT scan after 1 month showed improved pulmonary nodules, which had nearly disappeared at 10 months (Fig. 1B). The VDRL titer decreased to 1 : 2 after 3 months and was nonreactive after 10 months.

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary involvement is well described in cases of congenital and tertiary syphilis [4]. However, pulmonary involvement is extremely rare in patients with secondary syphilis. In fact, one prior report denied the existence of parenchymal pulmonary disease in patients with secondary syphilis. In a study conducted between 1939 and 1944, 1,500 patients with secondary syphilis showed no pulmonary involvement in radiographic studies [6]. However, nine cases of pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis have been reported since 1966 [4]. Pulmonary lesions appeared as an infiltration [7], consolidation with pleural effusion [8], solitary pulmonary nodule [9], or multiple ill-defined nodules [6]. This is the third case of secondary syphilis presenting as multiple pulmonary nodules. However, this case differed from previous reports in that the appearance of the nodules was well defined, and mimicked hematogenous metastatic carcinoma.

Serological testing remains the major method for the diagnosis of syphilis [1]. There are two types of tests: treponemal and nontreponemal [10]. Treponemal tests are treponemal antigen-based, such as the treponemal enzyme immunoassay, T. pallidum particle agglutination, or hemagglutination, and FTA-ABS. Advantages of treponemal tests include their high sensitivity and specificity. The FTA-ABS test is generally accepted as the most sensitive and is considered the gold standard method of diagnosis [10].

Nontreponemal tests are cardiolipin-based, such as the rapid plasma reagin, or VDRL. These are still commonly used as screening tests; they are cheap and easy to perform. After successful treatment of syphilis, the titer of nontreponemal tests falls and becomes negative. However, treponemal tests remain positive for life [10]. In this case, the VDRL was reactive, and the FTA-ABS test confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. VDRL titers decreased, from 1 : 64 to nonreactive, after benzathine penicillin G treatment.

The diagnosis of secondary syphilis can be determined by history, the presence of the typical skin rash, and positive serological findings. However, the diagnosis of pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis is difficult. Differential diagnostic considerations should include primary or metastatic cancer, tuberculosis, mycotic or bacterial abscess formation, sarcoidosis, pulmonary infarction, collagen vascular disease, and bronchiectasis [9]. In this case, because the multiple pulmonary nodules suggested metastatic cancer, a complete medical evaluation, including a biopsy, was performed.

For the diagnosis of pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis, the following criteria should be satisfied [7]: 1) history and physical findings typical of secondary syphilis, 2) serological testing positive for secondary syphilis, 3) pulmonary abnormalities seen on radiographs, with or without associated symptoms, 4) exclusion of other pulmonary disease, by serological tests, sputum smears, cultures, and sputum cytology, and 5) therapeutic response of the radiologic findings to antisyphilitic therapy. In this case, each of these criteria was met, so pulmonary involvement in secondary syphilis was confirmed.

Penicillin is still the treatment of choice for all stages of syphilis [5]. Treatment consists of a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units, for primary and secondary syphilis, as well as early latent syphilis. Late latent and tertiary syphilis requires three doses of benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units, at weekly intervals. Oral doxycycline is an alternative for patients with penicillin allergy [5].

Many surveys have reported recent increases in the prevalence of syphilis worldwide [5]. One reason for the re-emergence of syphilis is the increase in promiscuous sexual behavior, possibly associated with the successful introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy that has to some degree reduced HIV-related phobia. Clinicians should be reminded of this largely forgotten disease and know the proper therapeutic approaches, along with screening for other sexually transmitted diseases in patients with syphilis.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

References

- 1.Lee V, Kinghorn G. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med. 2008;8:330–333. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.8-3-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker JD, Chen XS, Peeling RW. Syphilis and social upheaval in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1658–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goh BT. Syphi l is in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:448–452. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.015875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David G, Perpoint T, Boibieux A, et al. Secondary pulmonary syphilis: report of a likely case and literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:e11–e15. doi: 10.1086/499104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wohrl S, Geusau A. Clinical update: syphilis in adults. Lancet. 2007;369:1912–1914. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60895-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biro L, Hill AC, Kuflik EG. Secondary syphilis with unusual clinical and laboratory findings. JAMA. 1968;206:889–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman DL, McPhee SJ, Ross TF, Naughton JL. Secondary syphilis with pulmonary involvement. West J Med. 1983;138:875–878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaharopoulos P, Wong J. Cytologic diagnosis of syphilitic pleuritis: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:35–38. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199701)16:1<35::aid-dc8>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cholankeril JV, Greenberg AL, Matari HM, Reisner MR, Obuchowski A. Solitary pulmonary nodule in secondary syphilis. Clin Imaging. 1992;16:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0899-7071(92)90126-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokolovskiy E, Frigo N, Rotanov S, et al. Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of syphilis in East European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:623–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]