Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a key endpoint in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), but heterogeneous definitions limit comparisons across RCTs or meta-analyses. The 2000 European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology MI redefinition and the 2007 universal MI definition consensus documents made recommendations to address this issue. In cardiovascular randomized trials, we evaluated the impact of implementation of three key recommendations from these reports—troponin use to define MI; separate reporting of spontaneous and procedure-related MI; and infarct size reporting. We searched ClinicalTrials.gov and MEDLINE databases for cardiovascular RCTs with more than 500 patients in which enrolment began between September 2000 and July 2012 and that listed MI in the primary endpoint. We searched English-language publications with primary results or design papers. Of 3222 studies screened, 96 (3.0%) met our criteria. We extracted enrolment start date, number of patients and MI events, follow-up duration, and coronary revascularization rate. Data extraction quality was assessed by duplicated extractions. Of 96 RCTs, 80 had a primary results publication, comprising 608 091 patients and 43 621 endpoint MIs. Myocardial infarction represented 45.3% (95% confidence interval, 40.2–50.4) of events in the primary composite endpoint. Troponin defined MI in 57% (53/93) of trials with an MI definition available. Of these RCTs, three used troponin only if creatine kinase-MB was unavailable, six used troponin to define peri-procedural MI, seven specified the 99th percentile as the MI decision limit, and three reported spontaneous and procedure-related MI separately. None reported biomarker-based infarct size, but five reported MI as multiples of the assay upper limit of normal. Although MI is a major component of cardiovascular RCT primary endpoints, standardized MI reporting and implementation of consensus document recommendations for MI definition are limited. Developing appropriate strategies for uniform implementation is required.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Clinical trials, Systematic reviews

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a widely accepted non-fatal cardiovascular endpoint employed to assess efficacy and/or safety of new treatments in clinical trials. However, failure to use a standard MI definition has emerged as a major challenge. In September 2000, recognizing the superior sensitivity and prognostic utility of troponin compared with creatine kinase (CK)-MB, an expert consensus document from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) provided guidance to the scientific and clinical communities on redefining MI and proposed troponin as the diagnostic ‘gold standard’.1 To improve consistency across randomized controlled trials (RCTs), this document specified that MI endpoints in RCTs be classified as spontaneous vs. related to coronary revascularization procedures and that the quantity of myonecrosis be determined. A 2007 and, most recently, a 2012 update reasserted troponin as the preferred biomarker for myonecrosis and also recommended that clinicians and investigators categorize MI type according to a five-category classification scheme, including whether the MI was spontaneous or revascularization-related.2,3 Prior to the release of the 2012 Universal Definition of MI document, we undertook the current study to evaluate the extent to which the 2000 and 2007 consensus recommendations had been implemented in contemporary cardiovascular RCTs.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of cardiovascular RCTs with more than 500 patients in which MI was part of the primary endpoint. The 500-patient threshold was selected to identify RCTs with enough MI endpoints to adequately assess all recommended components of MI reporting and that would be most likely to affect clinical practice. For the same reason, we limited our search to published trials. Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.4

Search strategy

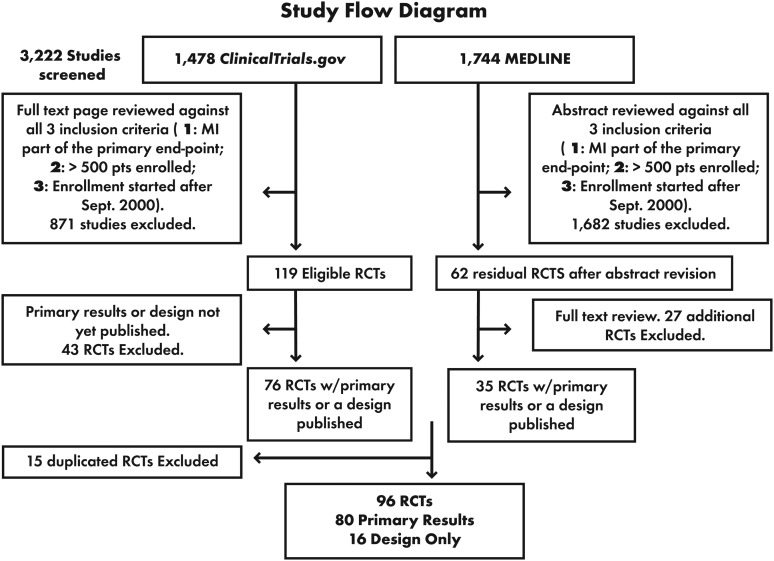

We separately searched two databases: ClinicalTrials.gov, the official source of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) for clinical trial registration, and the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database. Although RCTs could be registered on ClinicalTrials.gov for the entire period explored (1 September 2000 through 4 July 2012), the NIH mandated registration of all RCTs only after 27 September 2007.5 Because some trials that started before September 2007 may not have been captured, we used MEDLINE to complement the ClinicalTrials.gov search. Finally, we reviewed online materials using the Google search engine. We restricted our search to RCTs in cardiovascular disease, but did not restrict the type of intervention to which patients were randomized. From this pool of RCTs, those with an enrolment start date before September 2000 were excluded from further analysis. Figure 1 outlines the results of our database searches, culminating in a final set of 96 RCTs for our study; 80 had primary results published and 16 had only a design paper. Additional details of our search methodology are explained in Supplementary material online, Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic review and selection of clinical trials.

Data abstraction

We abstracted study name; enrolment start date; publication year; numbers of patients, MI events, and components in the primary endpoint composite; reference within the publication to the 2000 ESC/ACC consensus document and the 2007 Universal Definition of MI; use of a clinical events classification committee; follow-up duration; and text of the endpoint MI definition used. Accuracy of the MI definition abstracted from the design paper and/or primary manuscript was assessed by contacting trial investigators and obtaining the endpoint MI definition for their respective trials. To ensure the quality of the data extraction process, a 30% random sample of included RCTs was re-reviewed, and the data were collected in a second abstraction sheet. In addition, a random 30% of records from each database was re-reviewed after initial screening was finalized as a quality check on RCT selection. No errors in data abstraction were identified by these quality control measures.

Metrics of guideline recommendations adherence

We determined the proportion of RCTs in which the ESC/ACC 2000 document and the 2007 Universal Definition of MI were referenced by manually reviewing the reference list of the design paper, primary results manuscript, or both. We also determined the proportion of RCTs referencing other consensus documents endorsed by the ESC, ACC, or American Heart Association (AHA). Then, we examined each trial for the use of the following key recommendations in the 2000 ESC/ACC consensus document for MI redefinition and in the 2007 Universal Definition of MI:

- Recommendation 1: Use of troponin for MI diagnosis and MI decision limit provided. We evaluated this recommendation in RCTs for which the MI definition (including biomarkers employed) used in the trial was published. In five trials, the biomarker employed was unavailable in the design paper or primary manuscript but was obtained by contacting the investigators.6–10 We also explored adherence to this recommendation according to coronary revascularization group and tertiles of duration of time between the publication of the ESC/ACC 2000 MI redefinition document and the start of enrolment. To explore the level of adherence to Recommendation 1 as a function of coronary revascularization rate, we created three RCT categories:

- Interventional RCTs: RCTs in which percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was required by protocol either as part of the randomized intervention or as an inclusion criterion. Only protocol violators did not undergo coronary revascularization, and the rate of revascularization was assumed to be near 100%.

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) RCTs: RCTs in which a coronary revascularization could be performed as part of treatment for the index ACS event but was not required.

- Other RCTs: RCTs in which coronary revascularization was possible but not expected (e.g. secondary prevention trials enrolling patients with risk factors but no prior MI or patients with chronic stable coronary artery disease).

- Recommendation 2: Separate reporting of spontaneous MI and procedure-related (PCI or CABG) MI.

- Recommendation 3: Report of infarct size using area under the troponin or CK-MB curve or peak biomarker values (ESC/ACC 2000 recommendation) or as a multiple of the upper limit of normal (ULN) of the applied cardiac biomarker (2007 Universal Definition of MI recommendation).

Finally, for the subgroup of trials that started after the publication of the 2007 Universal Definition of MI, we also assessed adherence to the five-type classification scheme proposed.

Survey

To assess underpinnings of gaps in implementing consensus document recommendations, we surveyed principal investigators of all 96 RCTs via an online questionnaire. Because some investigators (n = 17) led more than 1 RCT, 66 individual investigators were surveyed. The full text of question and answer options is provided in Supplementary material online, Appendix 2. To encourage full participation, we sent e-mail reminders and scheduled telephone calls or in-person visits as needed. Responses were received from 61 of 66 investigators (92.4%), corresponding to responses for 91 of 96 RCTs. Every investigator who responded answered all survey questions completely.

Statistical analysis

The contribution of MI to the primary composite endpoint was examined using a random effects meta-analysis to estimate the mean proportion. This approach assigns weights to trials accounting for both (i) sampling error due to finite sample size within trials and (ii) random variability due to heterogeneous populations among trials. Results are presented using mean point estimates [95% confidence intervals (CIs)] of the proportion. This proportion was also evaluated considering RCTs by coronary revascularization group and groupings of follow-up duration (timing of endpoint assessment). The same method was used to identify the revascularization proportion in ACS RCTs and Other RCTs. To address the primary hypotheses, for each recommendation, the level of adherence was calculated as the proportion of RCTs fulfilling that recommendation. In addition, for Recommendation 1, we also explored adherence by coronary revascularization group and by time from the publication of the 2000 consensus document to the start of enrolment. In a sensitivity analysis, we examined the use of the three consensus document recommendations in RCTs with more than 100 but 500 or less patients (Supplementary material online, Appendix 3).

Results

Table 1 shows RCTs with a primary results publication available. Of these 80 RCTs, all but 4 (5%)26,27,30,78 reported the use of a clinical events classification committee blinded to treatment assignment. These MI definitions are detailed in Supplementary material online, Table S1A–C, and grouping of trials by coronary revascularization rate is provided in Supplementary material online, Table S2. The rate of coronary revascularization was 50.6% (95% CI 40.0–61.1) in ACS RCTs and 4.4% (95% CI 2.1–9.0) in Other RCTs. One published trial reported MI event rates only graphically.26

Table 1.

Characteristics of 80 cardiovascular published randomized clinical trials ordered by the start date of enrolment

| Study name | Start date | PubYear | Patients | MI, n | MI, % | Follow-up duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REPLACE 111 | November 2000 | 2004 | 1056 | 50 | 75.8 | 48 h |

| PROVE IT TIMI 2212 | November 2000 | 2004 | 4162 | 292 | 28.8 | 2 yearsa |

| MATCH13 | December 2000 | 2004 | 7599 | 121 | 9.8 | 18 months |

| ESTEEM14 | January 2001 | 2003 | 1883 | 83 | 32.7 | 6 months |

| ISAR SWEET15 | January 2001 | 2004 | 701 | 32 | 54.2 | 1 year |

| SIRIUS16 | February 2001 | 2003 | 1058 | 32 | 20.5 | 9 months |

| PROactive6 | May 2001 | 2005 | 5238 | 223 | 20.5 | 34.5 monthsa |

| ADVANCE17 | June 2001 | 2007 | 11 140 | 91 | 5.1 | 4.3 yearsa |

| ICTUS18 | July 2001 | 2005 | 1200 | 149 | 56.7 | 1 year |

| SYNERGY19 | August 2001 | 2004 | 10 027 | 1207 | 85.1 | 30 days |

| FIRE20 | October 2001 | 2003 | 651 | 124 | 88.6 | 30 days |

| REPLACE 221 | October 2001 | 2003 | 6010 | 392 | 68.3 | 30 days |

| OnTARGET22 | November 2001 | 2008 | 25 620 | 1291 | 30.6 | 56 monthsb |

| PRIMO CABG23 | January 2002 | 2004 | 3099 | 252 | 85.4 | 30 days |

| JIKEI HEART24 | January 2002 | 2007 | 3081 | 36 | 14.9 | 3.1 yearsb |

| CHOIR25 | March 2002 | 2006 | 1432 | 38 | 17.1 | 16 monthsb |

| ALMICAD26 | April 2002 | 2007 | 1233 | NAc | NAc | 24 months |

| Lee et al.27 | April 2002 | 2005 | 689 | 13 | 81.3 | 30 days |

| RACS28 | April 2002 | 2007 | 1004 | 20 | 64.5 | 180 days |

| ExTRACT TIMI 2529 | October 2002 | 2006 | 20 479 | 767 | 34.2 | 30 days |

| HEART 2D30 | October 2002 | 2009 | 1115 | 136 | 35.5 | 32 monthsa |

| CHARISMA31 | October 2002 | 2006 | 15 603 | 301 | 27.2 | 28 monthsb |

| Nussmeier et al.32 | January 2003 | 2005 | 1671 | 2 | 2.0 | 40 days |

| CLARITY TIMI 2833 | February 2003 | 2005 | 3491 | 108 | 16.9 | Index H |

| ARTS II34 | February 2003 | 2007 | 607 | 38 | 44.2 | 30 days, 1 year |

| PASSION35 | March 2003 | 2006 | 619 | 11 | 16.7 | 1 year |

| OASIS 536 | March 2003 | 2006 | 20 078 | 527 | 45.7 | 9 days |

| Windecker et al.37 | April 2003 | 2005 | 1012 | 32 | 37.2 | 9 months |

| ARISE38 | June 2003 | 2008 | 6144 | 243 | 22.9 | 24 monthsa |

| ACTIVE W39 | June 2003 | 2006 | 6706 | 59 | 14.8 | 1.28 yearsb |

| PROXIMAL40 | July 2003 | 2007 | 594 | 7 | 12.3 | 30 days |

| ACUITY41 | August 2003 | 2006 | 13 819 | 704 | 45.6 | 30 days |

| OASIS 642 | August 2003 | 2006 | 12 092 | 317 | 25.1 | 30 days |

| EASY43 | October 2003 | 2006 | 1005 | 107 | 51.2 | 30 days |

| TYPHOON44 | October 2003 | 2006 | 2019 | 9 | 11.7 | 1 year |

| PRIMO CABG II45 | July 2004 | 2011 | 4254 | 549 | 82.7 | 30 days |

| SORT OUT II46 | August 2004 | 2008 | 2098 | 98 | 43.4 | 18 months |

| MULTI STRATEGY47 | October 2004 | 2008 | 744 | 15 | 48.4 | 30 days |

| MERLIN TIMI 3648 | October 2004 | 2007 | 6560 | 477 | 32.9 | 30 days |

| TRITON TIMI 3849 | November 2004 | 2007 | 13 608 | 1095 | 76.9 | 15 months |

| EARLY ACS50 | November 2004 | 2009 | 9492 | 690 | 76.0 | 96 h |

| BEAUTIFUL51 | December 2004 | 2008 | 10 917 | 425 | 25.4 | 19 monthsb |

| DOORS52 | January 2005 | 2012 | 900 | 62 | 66.0 | 30 days |

| SYNTAX53 | March 2005 | 2009 | 1800 | 71 | 26.9 | 1 year |

| HORIZONS-AMI54 | March 2005 | 2008 | 3602 | 65 | 16.9 | 30 days |

| PRECOMBAT55 | March 2005 | 2011 | 600 | 8 | 13.3 | 1 year |

| I CARE56 | April 2005 | 2008 | 1434 | 24 | 49.0 | 18 monthsd |

| COSTAR II57 | May 2005 | 2008 | 1700 | 50 | 33.3 | 8 months |

| ISAR LEFT MAIN58 | July 2005 | 2009 | 607 | 29 | 32.6 | 1 year |

| AIM HIGH10 | September 2005 | 2011 | 3414 | 172 | 30.9 | 3 yearsa |

| ISAR REACT 359 | November 2005 | 2008 | 4570 | 238 | 61.2 | 30 days |

| CRESCENDO60 | December 2005 | 2010 | 18 695 | 282 | 38.2 | 13.8a |

| CHAMPION-PCI61 | April 2006 | 2009 | 8877 | 534 | 94.3 | 48 h |

| CURRENT62 | June 2006 | 2010 | 25 086 | 514 | 47.6 | 30 days |

| RIVAL63 | June 2006 | 2011 | 7021 | 125 | 46.8 | 30 days |

| ISAR REACT 464 | July 2006 | 2011 | 1721 | 117 | 61.9 | 30 days |

| SPIRIT IV65 | August 2006 | 2010 | 3687 | 82 | 45.1 | 1 year |

| CH. PLATFORM66 | September 2006 | 2009 | 5022 | 368 | 93.2 | 48 h |

| PLATO67 | October 2006 | 2009 | 18 093 | 1097 | 58.4 | 12 months |

| MEND CABG II68 | November 2006 | 2008 | 3023 | 243 | 89.0 | 30 days |

| LEADERS69 | November 2006 | 2008 | 1707 | 88 | 52.4 | 9 months |

| ZEST70 | November 2006 | 2010 | 2645 | 164 | 56.9 | 1 year |

| CORONARY71 | November 2006 | 2012 | 4752 | 328 | 68.6 | 30 days |

| PRODIGY72 | December 2006 | 2012 | 2013 | 80 | 40.4 | 24 months |

| COMPARE73 | February 2007 | 2010 | 1800 | 43 | 71.7 | 1 year |

| REAL LATE74 | July 2007 | 2010 | 2701 | 17 | 53.1 | 2 years |

| ECLAT STEMI75 | July 2007 | 2012 | 786 | 74 | 77.9 | 30 days |

| ISAR TEST 476 | September 2007 | 2009 | 2603 | 99 | 27.6 | 1 year |

| TRA 2°P TIMI 5077 | September 2007 | 2012 | 26 449 | 1237 | 56.1 | 30 monthsb |

| MI FREEE78 | November 2007 | 2011 | 5855 | 423 | 40.1 | 13.1 months |

| ISAR CABG79 | November 2007 | 2011 | 610 | 30 | 27.3 | 1 year |

| TRACER80 | December 2007 | 2011 | 12 944 | 1319 | 61.8 | 502 daysb |

| ISAR TEST 581 | February 2008 | 2011 | 3002 | 77 | 19.7 | 1 year |

| RESOLUTE AC82 | May 2008 | 2010 | 2292 | 93 | 50.0 | 1 year |

| AIDA STEMI83 | July 2008 | 2012 | 2065 | 34 | 25.0 | 90 days |

| ISAR REACT 3A84 | August 2008 | 2010 | 2505 | 209 | 92.5 | 30 days |

| ATLAS ACS85 | November 2008 | 2012 | 15 526 | 613 | 61.2 | 13 months |

| PLATINUM86 | January 2009 | 2011 | 1530 | 21 | 28.8 | 1 year |

| APPRAISE 287 | March 2009 | 2011 | 7392 | 376 | 65.7 | 241 days |

| Litt et al.88 | July 2009 | 2012 | 1370 | 15 | 100.0 | 30 days |

PubYear is the year of publication; MI, n is the absolute number of myocardial infarction within the primary endpoint; MI, % is the proportion of myocardial infarction endpoint events within the primary composite.

aMean follow-up duration.

bMedian follow-up duration.

cThe ALMICAD trial did report the actual number of MI events.

dThe I CARE trial was terminated early at 18 months for efficacy.

Contribution of myocardial infarction to the primary endpoint

Using 79 RCTs with primary results provided as MI counts, we estimated that MI contributed 45.3% (95% CI 40.2–50.4) of events in the primary composite outcomes of large cardiovascular RCTs. The proportion that MI contributed to the primary composite endpoint decreased with increasing number of endpoint components (Supplementary material online, Figure S1) and was highest among Interventional RCTs and trials with a follow-up duration of ≤1 month (Table 2).

Table 2.

Myocardial infarction contribution to the primary endpoint by revascularization group and by follow-up duration

| Category | Group | n | MI % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revascularization rate | Interventional | 46 | 53.2 (45.7–60.5) |

| ACS | 16 | 46.8 (37.1–56.8) | |

| Other | 17 | 24.3 (18.1–31.8) | |

| Follow-up duration | ≤1 month | 31 | 64.3 (55.5–72.1) |

| Between 1 month and 1 year | 25 | 35.6 (29.0–42.9) | |

| >1 year | 23 | 32.2 (24.8–40.6) |

Proportion of MIs in the primary composite endpoint was calculated using random effects estimates with 95% CIs.

CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction.

Proportion of RCTs referencing published myocardial infarction definition documents

Among 96 RCTs with a primary results and/or design paper, 7 (7.3%) referenced the ESC/ACC 2000 document for endpoint MI definition and 18 (18.8%) referenced the Universal Definition of MI 2007 publication. In addition, 34 (35.4%) cited another consensus document (27 referenced the Academic Research Consortium definition89,90; 7 referenced the ACC Key Standards document,91 both of which referred to the ESC/ACC 2000 document). Fourteen (14.6%) RCTs published no MI definition.16,17,22,24,31,39,46,51,58,74,92–95 After contacting investigators, we received and examined 93 of 96 endpoint MI definitions (96.9%). Table 3 presents an overview of key features of these definitions in the 10 largest RCTs, which accounted for 199 448 patients (32.8% of all patients in RCTs we evaluated). In these trials, both the threshold for spontaneous MI (1× or 2× ULN) and the biomarker used (CK-MB or troponin) varied. Definitions of re-infarction in RCTs that enrolled patients with acute MI also varied (Supplementary material online, Appendix 4 and Table S3).

Table 3.

Key features of the myocardial infarction definition in the 10 largest randomized clinical trials

| Trial | Spontaneous MI |

PCI-related MI |

CABG-related MI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred biomarker | Fold elevation above ULN | Preferred biomarker | Fold elevation above ULN | Preferred biomarker | Fold elevation above ULN | |

| TRA 2°P TIMI 5077a | cTn | 1 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB/cTn | 5 |

| ONTARGET22b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CURRENT62 | CK-MB/cTn | 2 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ Qw) or 10 (w/o Qw) |

| ExTRACT TIMI 2529 | CK-MB/cTn | 1 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ Qw) or 10 (w/o Qw) |

| OASIS 536 | CK-MB | 2 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 or Qw |

| CRESCENDO60 | CK-MB/cTn/CK | 2/1/2 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ Qw) or 10 (w/o Qw) |

| PLATO67 | CK-MB/cTn | 1 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ Qw) or 10 (w/o Qw) |

| CHARISMA31c | CK-MB/cTn | 2/1 | – | – | – | – |

| ATLAS85d | CK-MB/cTn | 1 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ com) or 10 (w/o com) |

| ACUITY96 | CK-MB/cTn | 1 | CK-MB | 3 | CK-MB | 5 (w/ Qw) or 10 (w/o Qw) |

aTRA 2°P TIMI 50 definition of CABG-related MI required additional complications beyond biomarker criterion (new Q-waves or new left-bundle branch block; angiographically documented graft or native coronary artery occlusion; or imaging evidence of new loss or viable myocardium).

bNo MI definition published for ONTARGET.

cThe CHARISMA trial did not use a separate MI definition for procedure-related MI.

dATLAS definition of CABG-related MI required additional complications beyond biomarker criterion (new Q-waves or new left-bundle branch block; angiographically documented graft or native coronary artery occlusion; or imaging evidence of new loss or viable myocardium) for CK-MB elevation between 5× and 10× the ULN.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CK-MB, creatine-kinase-MB; com, additional complications; cTn, cardiac troponin; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not available; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Qw, Q-waves; ULN, upper limit of normal; w/, with; w/o, without.

Recommendation 1: use of troponin for myocardial infarction diagnosis and myocardial infarction decision limit provided

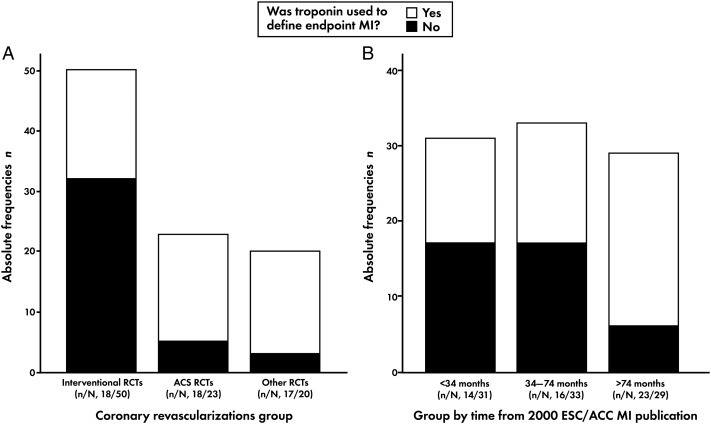

Among 93 RCTs with an MI definition provided, troponin was used to define the MI endpoint in 53 (57%). This proportion was 66.7% (n = 34) among 51 RCTs that referenced any consensus document for MI definition. Three of 93 RCTs used troponin to define endpoint MI only if CK-MB was unavailable,36,62,88 6 used troponin to define procedural MI, and 7 specified the 99th percentile as the MI decision limit. All other RCTs (n = 40) used CK-MB or total CK to define endpoint MI. The use of troponin to define endpoint MI by revascularization group and by time between ESC/ACC 2000 publication and the start of RCTs enrolment is shown in Figure 2A and B, respectively. Among trial types, adherence to Recommendation 1 was lowest among Interventional RCTs, and by time from publication to enrolment start, the highest use of troponin occurred among RCTs that began >74 months after the publication of the ESC/ACC 2000 document.

Figure 2.

(A) Troponin use for endpoint myocardial infarction definition by coronary revascularization group. (B) Troponin use for endpoint myocardial infarction definition by time from the publication of 2000 ESC/ACC MI document to the start of trial enrolment.

Recommendation 2: separate reporting of spontaneous myocardial infarction and myocardial infarction related to surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization procedures

Three trials (3.7%) reported spontaneous and procedural MI separately.18,77,80 The ICTUS trial, which adhered to the 2000 ESC/ACC MI redefinition, compared an early invasive strategy with a selective invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.18 Overall, 149 MIs occurred; 32.9% were spontaneous and 67.1% were procedure-related. The TRACER80 and TRA 2°P TIMI 5077 trials reported MI using the five-type classification scheme proposed by the 2007 Universal Definition of MI.

Recommendation 3: report of comparison of size of myocardial infarction between treatment and control groups in addition to the presence/absence of myocardial infarction

No trials reported a comparison of infarct size between treatment and control groups, using area under the biomarker curve. Five trials compared MI rates between treatment and control groups, using size thresholds (e.g. 3×–5× ULN, 5×–10× ULN, or >10× ULN), but did not provide actual peak levels.11,20,21,40,68

Similar results for the use of the three recommendations explored were observed in sensitivity analyses of RCTs with more than 100 but 500 or less patients (Supplementary material online, Table S4).

2007 Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction adherence

Of the 96 trials included, 25 (26.0%) started enrolment after the publication of the 2007 Universal Definition of MI. Of these, 11 (44.0%) referenced this definition in the design or primary results paper. Troponin defined endpoint MI in 19 (76.0%). Nine (36.0%) used the five-type classification scheme to define endpoint MI, but seven of these nine adapted this classification, typically for PCI-related (type 4a) MI definition, by using CK-MB instead of troponin.

Survey results

A survey was administered to the investigators between April 2011 and July 2012. Of 61 unique investigators responding to the survey, 54 (88.5%) responded that the use of a standard MI definition in RCTs was important, but 40 of those 54 (74.1%) also indicated that the ESC/ACC/AHA/WHF (World Heart Federation) task force definition created challenges related to assay variability and definition of re-MI and PCI-related MI. Overall, 54 investigators (88.5%) said troponin should be used to define MI in RCTs, but 18 added that they would not use high-sensitivity troponin assays. Of these 54, 38 (70.4%) specified their preference for troponin to define spontaneous but not procedural MI. The most common reasons for not favouring troponin in the procedural setting were as follows: (i) the recommended diagnostic threshold for troponin was too low (n = 23, 60.5%); (ii) a belief that there was a lack of clinical relevance of asymptomatic troponin elevations after procedures (n = 10, 26.3%); and (iii) these elevations are a marker of atherosclerosis burden but have no independent relationship with mortality (n = 10, 26.3%).

For each of the 96 trials in our analysis, we asked the principal investigator to specify whether a standardized MI definition was used; we obtained responses for 91 trials. A standard MI definition was reported in 49 trials (53.8%); 22 reported using the universal MI definition.

Discussion

In this large and broad cross-section of contemporary RCTs in cardiovascular disease, we estimated that MI contributes an average of 45.3% of events in primary endpoint composites. Despite the frequency and importance of MI as an endpoint component in RCTs that establish the evidence for the use of therapies in cardiovascular practice, MI definition was heterogeneous and implementation of recent consensus recommendations for defining MI was low. Overall, only 57.0% of RCTs used troponin to define endpoint MI, whereas 43.0% of trials used the less-specific CK-MB or total CK. This trend was especially evident among RCTs studying revascularization, of which only six trials specified troponin to define procedure-related MI. One in seven trials failed to publish any criteria for MI definition. Although the use of troponin was more frequent among RCTs in which enrolment started >74 months after the publication of the 2000 ESC/ACC consensus MI definition document, overall these findings suggest a lack of standardized implementation of one of the most important endpoint definitions in cardiovascular RCTs.

Use of troponin to define endpoint myocardial infarction

Owing to nearly absolute myocardial specificity, the use of troponins I and T was emphasized in the ESC/ACC 2000 redefinition of MI consensus statement1 and reinforced in the 2007 Universal Definition of MI document.2 Thus, it is noteworthy that slightly more than half of cardiovascular RCTs we examined used troponin to define endpoint MI. Even among RCTs that referenced a consensus document, only 66.7% used troponin to define endpoint MI and only 7 specified the recommended 99th percentile as the MI decision limit. These findings are in sharp contrast to the rapid uptake of troponins to define MI in clinical practice.97

Because failure to implement a standard approach to define MI in RCTs impairs systematic comparison of results across trials, our findings underscore the need to (i) increase awareness of consensus documents; (ii) overcome impediments to implementation of consensus recommendations in RCTs; and (iii) develop uniform standards for determining and reporting endpoint MI in RCTs and defining the role of troponin.

Spontaneous and procedural myocardial infarction reporting and infarct size

Remarkably, only three of 80 RCTs separately reported spontaneous and procedural MI, whereas five reported MI rates between treatment arms, using threshold biomarker size, and no RCT provided actual peak biomarker levels. Although there is general agreement that procedure-related myocardial necrosis has some prognostic implication, it remains controversial as to how best to weigh its impact relative to spontaneous MI.96 Indeed, separate reporting was a key consideration driving the five-group classification in the 2007 and 2012 MI definition documents.2,3 Finally, it may be useful to compare the effect of treatments using a more sensitive, continuous measure of myonecrosis, such as the peak biomarker value, in addition to the presence/absence of MI. Without consistently defining and reporting MI, it will remain challenging to compare studied populations and reported results across trials.

Understanding gaps in the implementation of consensus document recommendations

Implementation of consensus recommendations for MI definition and reporting is likely time-dependent. The use of troponin to define endpoint MI was higher in RCTs that began >74 months after ESC/ACC MI 2000 redefinition, compared with earlier trials. This may reflect increased acceptance over time of troponin as the preferred biomarker to define MI. It may also reflect that establishing endpoint definitions in the design phase of clinical trials often precedes the start of enrolment. However, even at 34–74 months (about 3–6 years after the 2000 redefinition document was published), only 48.5% of trials used troponin to define endpoint MI: this suggests it was unlikely the only factor in our findings.

Troponin was used least often to define MI in Interventional RCTs. Although the association of CK-MB elevation (mainly defined as >3× ULN) with death after coronary revascularization has been demonstrated, whether this relationship exists for troponin and at what level of elevation above the 99th percentile is less certain.98–100 This has prompted debate about the use of troponin to define procedure-related MI.101 Our investigator survey revealed a reluctance to use troponin to define procedure-related MI; only 16 of 61 investigators favoured troponin to define procedure-related MI. The most common reason cited (60.5%) was the low recommended diagnostic threshold (i.e. 3× ULN for PCI-related MI). It is reassuring that the most recent version of the Universal Definition of MI has addressed this concern by raising the recommended threshold for peri-PCI MI from 3× ULN to 5× ULN, although the task force recognizes that these thresholds are arbitrary.3

About one-fourth of respondents were concerned about clinical relevance, including that asymptomatic troponin elevation post-procedure is not clinically important or that it is a marker of atherosclerosis burden but has no independent relationship with mortality. Concerns have also been raised that interpreting peri-procedural troponin elevations is challenging and may be less relevant among patients with pre-procedural elevation.102,103 Increasingly sensitive troponin assays will add more complexity to this debate by increasing the proportion of patients with elevated baseline troponin levels. However, a recent analysis of pooled data from more than 10 000 clinical trial patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS that assessed troponin trends before and at the time of PCI found that (i) in using pre-procedural troponin trends to identify patients with stable or falling troponin levels, 57% of patients could be assessed for peri-PCI MI, and (ii) if troponin levels were stable or falling before PCI, then a new troponin re-elevation post-PCI was associated with worse outcomes, even after accounting for pre-procedural troponin levels.104 The importance of assessing cardiac marker trends before PCI in adjudicating peri-PCI MI was also emphasized by the recent 2012 Universal Definition of MI.2,3 Thus, enhanced use of a standard MI definition that incorporates troponin will likely be most successful by iteratively addressing investigator concerns. Only reassessment of the degree of implementation of the 2012 Universal Definition of MI in several years will confirm whether the changes (which are consistent with our survey findings of reasons for failure of significant implementation to date) were successful in increasing standardized MI definition in clinical trials. We believe our survey not only has provided important insights into investigator concerns about implementing standard MI definitions in clinical trials, but it can also serve as the framework for the future reassessments of implementation.

Concern about the relevance of peri-procedural troponin elevations and MI definition thresholds does not entirely explain the low implementation of the Universal Definition of MI. Even ACS RCTs and Other RCTs incompletely incorporated ESC/ACC consensus recommendations for troponin use to define MI, particularly at the 99th percentile. This may reflect ongoing concerns about precision of some assays at the 99th percentile. Even if assays are very precise at the 99th percentile, it is also unknown whether smaller MIs that may be detected and that generally are associated with lower risk for adverse outcomes would affect the ability to detect overall treatment differences in RCTs. New generation troponin assays with even higher sensitivity will likely add more uncertainty, as recently acknowledged by the Third Universal Definition of MI.3 It is noteworthy that more than one-quarter of investigators surveyed favoured troponin to define MI, but not the use of high-sensitivity assays due to potential ‘noise’ or non-clinically relevant MI event detection. Although these concerns could lead to troponin use at a cutoff above the 99th percentile, they would not solely explain overall low rates of incorporation of troponin testing into MI endpoint definitions. To this point, 11.5% of investigators felt troponin should not be used at all to define MI in RCTs.

Future directions

The low use of consensus document recommendations we observed identifies a pressing need to implement standard definition and reporting of MI endpoints in cardiovascular RCTs. We believe that the reporting criteria developed by the ACC/AHA/ESC/WHF Writing Group for Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction should be required as part of the standardized CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) reporting system for clinical trials now adopted by major medical journals.105 Using this type of standardized reporting system, such as that recently developed for bleeding,106 would make it easier for both clinicians and clinical trialists to understand findings of RCTs. Moreover, we suggest that the redefinition of MI writing group consider modifications that address concerns and perspectives among investigators that were identified in our survey. Other specific efforts and measures that may facilitate uniform definition and reporting include the following: (i) requirements from regulatory authorities for standard MI definition in RCTs in which MI is a key component of the primary endpoint, including appropriate distinction of MI types; and (ii) requirements by journal editors that actual data for necrosis markers used to determine MI endpoints in RCTs be submitted as a supplementary file with each primary results manuscript so that they are publically available. This would provide an important opportunity for investigators, regulators, and critics to examine varying definitions of MI (e.g. varying troponin thresholds for MI) and how they affect trial results.

To successfully implement standard definition and reporting of MI in RCTs, logistical issues, including pros and cons of local laboratory vs. core laboratory troponin measurement, must be addressed. In particular, if local measurements are used, how best to incorporate and account for the wide variety and lack of standardization of available troponin assays and their varying performance characteristics must be resolved.

Limitations and strengths

We acknowledge some limitations of our systematic review but also would point to its strengths. Whereas one author (S.L.) screened and abstracted all the data, we implemented rigorous quality checks to ensure complete and consistent data abstraction. Also, the inclusion/exclusion criteria and parameters assessed were stringent, reducing the likelihood of bias that could substantially alter the results. These contentions are supported by our sensitivity analysis that examined smaller RCTs, revealing similar findings. Furthermore, we limited our search to primary results and/or design papers. RCTs may report the incidence of spontaneous and procedural MI in a secondary publication.107 However, because the consensus recommendations were designed for use in primary MI endpoint determination, we felt that a stringent approach to addressing their implementation for primary results presentation was important. More importantly, reporting results according to these key recommendations in secondary publications, which are more difficult to identify and often occur well after the primary results are published, creates unnecessary obstacles to understanding the primary results. Finally, the quality of data management and monitoring, which is usually not publicly or readily available, was not analysed in our systematic review.

Conclusions

Although MI contributes significantly to primary outcome measures in contemporary RCTs, low implementation of the 2000 ESC/ACC MI redefinition and 2007 Universal Definition of MI consensus recommendations was evident. This was particularly true regarding the use of troponin to define MI. Given the importance of MI as a metric in clinical practice, clinical trials, and epidemiological studies, it is necessary to better understand this failure and to create appropriate strategies for uniform implementation of recommendations. Our survey, from a broad cross-section of contemporary RCTs, underscores the need for further investigation to establish the most appropriate and clinically meaningful definition of peri-procedural MI.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by the investigators and by the National Institutes of Health (T32HL079896 to P.J.S.). No other commercial, foundation, philanthropic, or government funding sources were used.

Conflict of interest: S.L. and P.J.S. report no conflicts of interest with the submitted work. P.W.A.: Consultancy—F. Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd., Axio/Orexigen, Eli Lilly & Co. Merck & Co., Inc. in conjunction with DCRI. Grant/grant pending—Boehringer Ingelheim, F. Hoffman-LaRoche Ltd. & Sanofi-Aventis Canada, Inc.; Sanofi-Aventis Canada Inc.; Scios, Inc., Ortho Biotech, Johnson & Johnson, Jansen Ortho in conjunction with DCRI; GlaxoSmithKline; Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. in conjunction with DCRI; Merck & Co., Inc. in conjunction with DCRI. Payment for development of educational presentations—AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly & Co. L.K.N.: Board membership—Society of Chest Pain Centers. Consultancy—Amgen, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly & Co., Genentech, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis. Grants/grants pending—Amylin, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, diaDexus, GlaxoSmith Kline, Merck & Co., Inc. MURDOCK Study, NHLBI, Regado Biosciences, Roche. Payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus—Johnson & Johnson, American Diabetes Association. Travel/accommodations/meeting expenses unrelated to activities listed—AHA, Society of Chest Pain Centers. E.M.O.: Consultancy—AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences Inc., Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., LipoScience, Merck & Co., Inc. Pozen, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company, WebMD. Grants/grants pending—Daiichi Sankyo, Daiichi Sankyo, Maquet.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Morgan deBlecourt for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript for submission. Finally, the authors are grateful to the investigators who participated in the survey for their important feedback and contributions.

References

- 1.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction: The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2173–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD the Writing Group on behalf of the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guidance on New Law (Public Law 110-85) enacted to expand the scope of ClinicalTrials.gov: registration http://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/fdaaa.html. Accessed 4 May 2010.

- 6.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM, Tan MH, Lefèbvre PJ, Murray GD, Standl E, Wilcox RG, Wilhelmsen L, Betteridge J, Birkeland K, Golay A, Heine RJ, Korányi L, Laakso M, Mokán M, Norkus A, Pirags V, Podar T, Scheen A, Scherbaum W, Schernthaner G, Schmitz O, Skrha J, Smith U, Taton J PROactive Investigators. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhry NK, Brennan T, Toscano M, Pettell C, Glynn RJ, Rubino M, Schneeweiss S, Brookhart AM, Fernandes J, Mathew S, Christiansen B, Antman EM, Avorn J, Shrank WH. Rationale and design of the Post-MI FREEE trial: a randomized evaluation of first-dollar drug coverage for post-myocardial infarction secondary preventive therapies. Am Heart J. 2008;156:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfisterer M, Bertel O, Bonetti PO, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Eberli FR, Erne P, Galatius S, Hornig B, Kiowski W, Pachinger O, Pedrazzini G, Rickli H, De Servi S, Kaiser C BASKET-PROVE Investigators. Drug-eluting or bare-metal stents for large coronary vessel stenting? The BASKET-PROVE (PROspective Validation Examination) trial: study protocol and design. Am Heart J. 2008;155:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, Jiang F, White HD, Fox KA, Sharma D, Chew P, Braunwald E ExTRACT-TIMI 25 Investigators. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin as antithrombin therapy in patients receiving fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Design and rationale for the Enoxaparin and Thrombolysis Reperfusion for Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 25 (ExTRACT-TIMI 25) Am Heart J. 2005;149:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoff AM, Bittl JA, Kleiman NS, Sarembock IJ, Jackman JD, Mehta S, Tannenbaum MA, Niederman AL, Bachinsky WB, Tift-Mann J, III, Parker HG, Kereiakes DJ, Harrington RA, Feit F, Maierson ES, Chew DP, Topol EJ REPLACE-1 Investigators. Comparison of bivalirudin versus heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention (the Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events [REPLACE]-1 trial) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ MATCH investigators. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331–337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallentin L, Wilcox RG, Weaver WD, Emanuelsson H, Goodvin A, Nyström P, Bylock A ESTEEM Investigators. Oral ximelagatran for secondary prophylaxis after myocardial infarction: the ESTEEM randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:789–797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Schühlen H, Dibra A, Dotzer F, von Beckerath N, Bollwein H, Pache J, Dirschinger J, Berger PP, Schömig A Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Is Abciximab a Superior Way to Eliminate Elevated Thrombotic Risk in Diabetics (ISAR-SWEET) Study Investigators. Randomized clinical trial of abciximab in diabetic patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary interventions after treatment with a high loading dose of clopidogrel. Circulation. 2004;110:3627–3635. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148956.93631.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O'Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, Harrap S, Poulter N, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee DE, Hamet P, Heller S, Liu LS, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan CY, Rodgers A, Williams B ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:829–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, Dunselman PH, Janus CL, Bendermacher PE, Michels HR, Sanders GT, Tijssen JG, Verheugt FW Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable Coronary Syndromes (ICTUS) Investigators. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1095–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson JJ, Califf RM, Antman EM, Cohen M, Grines CL, Goodman S, Kereiakes DJ, Langer A, Mahaffey KW, Nessel CC, Armstrong PW, Avezum A, Aylward P, Becker RC, Biasucci L, Borzak S, Col J, Frey MJ, Fry E, Gulba DC, Guneri S, Gurfinkel E, Harrington R, Hochman JS, Kleiman NS, Leon MB, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pepine CJ, Ruzyllo W, Steinhubl SR, Teirstein PS, Toro-Figueroa L, White H SYNERGY Trial Investigators. Enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an intended early invasive strategy: primary results of the SYNERGY randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:45–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone GW, Rogers C, Hermiller J, Feldman R, Hall P, Haber R, Masud A, Cambier P, Caputo RP, Turco M, Kovach R, Brodie B, Herrmann HC, Kuntz RE, Popma JJ, Ramee S, Cox DA FilterWire EX Randomized Evaluation Investigators. Randomized comparison of distal protection with a filter-based catheter and a balloon occlusion and aspiration system during percutaneous intervention of diseased saphenous vein aorto-coronary bypass grafts. Circulation. 2003;108:548–553. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080894.51311.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lincoff AM, Bittl JA, Harrington RA, Feit F, Kleiman NS, Jackman JD, Sarembock IJ, Cohen DJ, Spriggs D, Ebrahimi R, Keren G, Carr J, Cohen EA, Betriu A, Desmet W, Kereiakes DJ, Rutsch W, Wilcox RG, de Feyter PJ, Vahanian A, Topol EJ REPLACE-2 Investigators. Bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention: REPLACE-2 randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:853–863. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, Schumacher H, Dagenais G, Sleight P, Anderson C The ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verrier ED, Shernan SK, Taylor KM, Van de Werf F, Newman MF, Chen JC, Carrier M, Haverich A, Malloy KJ, Adams PX, Todaro TG, Mojcik CF, Rollins SA, Levy JH PRIMO-CABG Investigators. Terminal complement blockade with pexelizumab during coronary artery bypass graft surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;291:2319–2327. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mochizuki S, Dahlöf B, Shimizu M, Ikewaki K, Yoshikawa M, Taniguchi I, Ohta M, Yamada T, Ogawa K, Kanae K, Kawai M, Seki S, Okazaki F, Taniguchi M, Yoshida S, Tajima N Jikei Heart Study Group. Valsartan in a Japanese population with hypertension and other cardiovascular disease (Jikei Heart Study): a randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint morbidity-mortality study. Lancet. 2007;369:1431–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60669-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, Reddan D CHOIR Investigators. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanal S, Obeidat O, Hudson MP, Al-Mallah M, Bloome M, Lu M, Greenbaum AB, Kugelmass AD, Weaver WD. Active Lipid Management In Coronary Artery Disease (ALMICAD) Study. Am J Med. 2007;120:734.e11–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SW, Park SW, Hong MK, Lee CW, Kim YH, Park JH, Kang SJ, Han KH, Kim JJ, Park SJ. Comparison of cilostazol and clopidogrel after successful coronary stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:859–862. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardi V, Szarfer J, Summay G, Mendiz O, Sarmiento R, Alemparte MR, Gabay J, Berger PB. Long-term versus short-term clopidogrel therapy in patients undergoing coronary stenting (from the Randomized Argentine Clopidogrel Stent [RACS] trial) Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:349–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, Murphy SA, Ruda M, Sadowski Z, Budaj A, López-Sendón JL, Guneri S, Jiang F, White HD, Fox KA, Braunwald E ExTRACT-TIMI 25 Investigators. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raz I, Wilson PW, Strojek K, Kowalska I, Bozikov V, Gitt AK, Jermendy G, Campaigne BN, Kerr L, Milicevic Z, Jacober SJ. Effects of prandial versus fasting glycemia on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: the HEART2D trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:381–386. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhatt DL, Fox KAA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, Flather MD, Haffner SM, Hamm CW, Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Mak KH, Mas JL, Montalescot G, Pearson TA, Steg PG, Steinhubl SR, Weber MA, Brennan DM, Fabry-Ribaudo L, Booth J, Topol EJ CHARISMA Investigators. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, Langford RM, Hoeft A, Parlow JL, Boyce SW, Verburg KM. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1081–1091. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, López-Sendón JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, Claeys MJ, Cools F, Hill KA, Skene AM, McCabe CH, Braunwald E CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1179–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuchida K, Colombo A, Lefèvre T, Oldroyd KG, Guetta V, Guagliumi G, von Scheidt W, Ruzyllo W, Hamm CW, Bressers M, Stoll HP, Wittebols K, Donohoe DJ, Serruys PW. The clinical outcome of percutaneous treatment of bifurcation lesions in multivessel coronary artery disease with the sirolimus-eluting stent: insights from the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study part II (ARTS II) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:433–442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laarman GJ, Suttorp MJ, Dirksen MT, van Heerebeek L, Kiemeneij F, Slagboom T, van der Wieken LR, Tijssen JG, Rensing BJ, Patterson M. Paclitaxel-eluting versus uncoated stents in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1105–1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Pogue J, Granger CB, Budaj A, Peters RJ, Bassand JP, Wallentin L, Joyner C, Fox KA The Fifth Organization to Assess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes Investigators. Comparison of fondaparinux and enoxaparin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1464–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Windecker S, Remondino A, Eberli FR, Jüni P, Räber L, Wenaweser P, Togni M, Billinger M, Tüller D, Seiler C, Roffi M, Corti R, Sütsch G, Maier W, Lüscher T, Hess OM, Egger M, Meier B. Sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:653–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tardif JC, McMurray JJ, Klug E, Small R, Schumi J, Choi J, Cooper J, Scott R, Lewis EF, L'Allier PL, Pfeffer MA Aggressive Reduction of Inflammation Stops Events (ARISE) Trial Investigators. Effects of succinobucol (AGI-1067) after an acute coronary syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1761–1768. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60763-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Chrolavicius S, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Yusuf S ACTIVE Writing Group of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1903–1912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mauri L, Cox D, Hermiller J, Massaro J, Wahr J, Tay SW, Jonas M, Popma JJ, Pavliska J, Wahr D, Rogers C. The PROXIMAL trial: proximal protection during saphenous vein graft intervention using the Proxis Embolic Protection System: a randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1442–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone GW, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, Bertrand ME, Lincoff AM, Moses JW, White HD, Pocock SJ, Ware JH, Feit F, Colombo A, Aylward PE, Cequier AR, Darius H, Desmet W, Ebrahimi R, Hamon M, Rasmussen LH, Rupprecht HJ, Hoekstra J, Mehran R, Ohman EM ACUITY Investigators. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2203–2216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Pogue J, Granger CB, Budaj A, Peters RJ, Bassand JP, Wallentin L, Joyner C, Fox KA OASIS-6 Trial Group. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1519–1530. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.joc60038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertrand OF, De Larochellière R, Rodés-Cabau J, Proulx G, Gleeton O, Nguyen CM, Déry JP, Barbeau G, Noël B, Larose E, Poirier P, Roy L Early Discharge After Transradial Stenting of Coronary Arteries Study Investigators. A randomized study comparing same-day home discharge and abciximab bolus only to overnight hospitalization and abciximab bolus and infusion after transradial coronary stent implantation. Circulation. 2006;114:2636–2643. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spaulding C, Henry P, Teiger E, Beatt K, Bramucci E, Carrié D, Slama MS, Merkely B, Erglis A, Margheri M, Varenne O, Cebrian A, Stoll HP, Snead DB, Bode C TYPHOON Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting versus uncoated stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1093–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith PK, Shernan SK, Chen JC, Carrier M, Verrier ED, Adams PX, Todaro TG, Muhlbaier LH, Levy JH PRIMO-CABG II Investigators. Effects of C5 complement inhibitor pexelizumab on outcome in high-risk coronary artery bypass grafting: combined results from the PRIMO-CABG I and II trials. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galloe AM, Thuesen L, Kelbaek H, Thayssen P, Rasmussen K, Hansen PR, Bligaard N, Saunamäki K, Junker A, Aarøe J, Abildgaard U, Ravkilde J, Engstrøm T, Jensen JS, Andersen HR, Bøtker HE, Galatius S, Kristensen SD, Madsen JK, Krusell LR, Abildstrøm SZ, Stephansen GB, Lassen JF SORT OUT II Investigators. Comparison of paclitaxel- and sirolimus-eluting stents in everyday clinical practice: The SORT OUT II randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:409–416. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Percoco G, Bolognese L, Vassanelli C, Colangelo S, de Cesare N, Rodriguez AE, Ferrario M, Moreno R, Piva T, Sheiban I, Pasquetto G, Prati F, Nazzaro MS, Parrinello G, Ferrari R Multicentre Evaluation of Single High-Dose Bolus Tirofiban vs Abciximab With Sirolimus-Eluting Stent or Bare Metal Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction Study (MULTISTRATEGY) Investigators. Comparison of angioplasty with infusion of tirofiban or abciximab and with implantation of sirolimus-eluting or uncoated stents for acute myocardial infarction: the MULTISTRATEGY randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1788–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.15.joc80026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrow DA, Scirica BM, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Murphy SA, Budaj A, Varshavsky S, Wolff AA, Skene A, McCabe CH, Braunwald E MERLIN-TIMI 36 Trial Investigators. Effects of ranolazine on recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: The MERLIN-TIMI 36 randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1775–1783. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giugliano RP, White JA, Bode C, Armstrong PW, Montalescot G, Lewis BS, van 't Hof A, Berdan LG, Lee KL, Strony JT, Hildemann S, Veltri E, Van de Werf F, Braunwald E, Harrington RA, Califf RM, Newby LK EARLY ACS Investigators. Early versus delayed, provisional eptifibatide in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2176–2190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R BEAUTIFUL Investigators. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:807–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Houlind K, Kjeldsen BJ, Madsen SN, Rasmussen BS, Holme SJ, Nielsen PH, Mortensen PE for the DOORS Study Group. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly patients: results from the Danish on-pump versus off-pump randomization study. Circulation. 2012;125:2431–2439. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.052571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serruys PW, Morice M-C, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Ståhle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ, Van Dyck N, Leadley K, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW SYNTAX Investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, Kornowski R, Hartmann F, Gersh BJ, Pocock SJ, Dangas G, Wong SC, Kirtane AJ, Parise H, Mehran R HORIZONS-AMI Trial Investigators. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2218–2230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park SJ, Kim YH, Park DW, Yun SC, Ahn JM, Song HG, Lee JY, Kim WJ, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, Park SW, Chung CH, Lee JW, Lim DS, Rha SW, Lee SG, Gwon HC, Kim HS, Chae IH, Jang Y, Jeong MH, Tahk SJ, Seung KB. Randomized trial of stents versus bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1718–1727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milman U, Blum S, Shapira C, Aronson D, Miller-Lotan R, Anbinder Y, Alshiek J, Bennett L, Kostenko M, Landau M, Keidar S, Levy Y, Khemlin A, Radan A, Levy AP. Vitamin E supplementation reduces cardiovascular events in a subgroup of middle-aged individuals with both type 2 diabetes mellitus and the haptoglobin 2-2 genotype: a prospective double-blinded clinical trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:341–347. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krucoff MW, Kereiakes DJ, Petersen JL, Mehran R, Hasselblad V, Lansky AJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Garg J, Turco MA, Simonton CA, III, Verheye S, Dubois CL, Gammon R, Batchelor WB, O'Shaughnessy CD, Hermiller JB, Jr, Schofer J, Buchbinder M, Wijns W COSTAR II Investigators Group. A novel bioresorbable polymer paclitaxel-eluting stent for the treatment of single and multivessel coronary disease: primary results of the COSTAR (Cobalt Chromium Stent With Antiproliferative for Restenosis) II study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Byrne RA, Bruskina O, Iijima R, Schulz S, Pache J, Seyfarth M, Massberg S, Laugwitz KL, Dirschinger J, Schömig A. LEFT-MAIN Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Drug-Eluting Stents for Unprotected Coronary Left Main Lesions Study Investigators. Paclitaxel-versus sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1760–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, Byrne RA, Iijima R, Büttner HJ, Khattab AA, Schulz S, Blankenship JC, Pache J, Minners J, Seyfarth M, Graf I, Skelding KA, Dirschinger J, Richardt G, Berger PB, Schömig A ISAR-REACT 3 Trial Investigators. Bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:688–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Topol EJ, Bousser MG, Fox KA, Creager MA, Despres JP, Easton JD, Hamm CW, Montalescot G, Steg PG, Pearson TA, Cohen E, Gaudin C, Job B, Murphy JH, Bhatt DL CRESCENDO Investigators. Rimonabant for prevention of cardiovascular events (CRESCENDO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:517–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60935-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrington RA, Stone GW, McNulty S, White HD, Lincoff AM, Gibson CM, Pollack CV, Jr, Montalescot G, Mahaffey KW, Kleiman NS, Goodman SG, Amine M, Angiolillo DJ, Becker RC, Chew DP, French WJ, Leisch F, Parikh KH, Skerjanec S, Bhatt DL. Platelet inhibition with cangrelor in patients undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2318–2329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, Diaz R, Eikelboom JW, Fox KA, Granger CB, Jolly S, Joyner CD, Rupprecht HJ, Widimsky P, Afzal R, Pogue J, Yusuf S CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:930–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, Niemelä K, Xavier D, Widimsky P, Budaj A, Niemelä M, Valentin V, Lewis BS, Avezum A, Steg PG, Rao SV, Gao P, Afzal R, Joyner CD, Chrolavicius S, Mehta SR RIVAL Trial Group. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1409–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, Schulz S, Massberg S, Byrne RA, Ferenc M, Laugwitz KL, Pache J, Ott I, Hausleiter J, Seyfarth M, Gick M, Antoniucci D, Schömig A, Berger PB, Mehilli J ISAR-REACT 4 Trial Investigators. Abciximab and heparin versus bivalirudin for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1980–1989. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, Mastali K, Wang JC, Caputo R, Doostzadeh J, Cao S, Simonton CA, Sudhir K, Lansky AJ, Cutlip DE, Kereiakes DJ SPIRIT IV Investigators. Everolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1663–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM, Gibson CM, Stone GW, McNulty S, Montalescot G, Kleiman NS, Goodman SG, White HD, Mahaffey KW, Pollack CV, Jr, Manoukian SV, Widimsky P, Chew DP, Cura F, Manukov I, Tousek F, Jafar MZ, Arneja J, Skerjanec S, Harrington RA CHAMPION PLATFORM Investigators. Intravenous platelet blockade with cangrelor during PCI. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2330–2341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Freij A, Thorsén M PLATO Investigators. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alexander JH, Emery RW, Jr, Carrier M, Ellis SJ, Mehta RH, Hasselblad V, Menasche P, Khalil A, Cote R, Bennett-Guerrero E, Mack MJ, Schuler G, Harrington RA, Tardif JC MEND-CABG II Investigators. Efficacy and safety of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (MC-1) in high-risk patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: the MEND-CABG II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1777–1787. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.15.joc80027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Windecker S, Serruys PW, Wandel S, Buszman P, Trznadel S, Linke A, Lenk K, Ischinger T, Klauss V, Eberli F, Corti R, Wijns W, Morice MC, di Mario C, Davies S, van Geuns RJ, Eerdmans P, van Es GA, Meier B, Jüni P. Biolimus-eluting stent with biodegradable polymer versus sirolimus-eluting stent with durable polymer for coronary revascularisation (LEADERS): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park DW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, Park SW, Seong IW, Lee JH, Tahk SJ, Jeong MH, Jang Y, Cheong SS, Yang JY, Lim DS, Seung KB, Chae JK, Hur SH, Lee SG, Yoon J, Lee NH, Choi YJ, Kim HS, Kim KS, Kim HS, Hong TJ, Park HS, Park SJ. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting stents with sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization: the ZEST (comparison of the efficacy and safety of zotarolimus-eluting stent with sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stent for coronary lesions) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, Taggart DP, Hu S, Paolasso E, Straka Z, Piegas LS, Akar AR, Jain AR, Noiseux N, Padmanabhan C, Bahamondes JC, Novick RJ, Vaijyanath P, Reddy S, Tao L, Olavegogeascoechea PA, Airan B, Sulling TA, Whitlock RP, Ou Y, Ng J, Chrolavicius S, Yusuf S CORONARY Investigators. Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1489–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, Vranckx P, Percoco G, Tumscitz C, Castriota F, Colombo F, Tebaldi M, Fucà G, Kubbajeh M, Cangiano E, Minarelli M, Scalone A, Cavazza C, Frangione A, Borghesi M, Marchesini J, Parrinello G, Ferrari R Prolonging Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading Stent-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia Study (PRODIGY) Investigators. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2015–2026. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kedhi E, Joesoef KS, McFadden E, Wassing J, van Mieghem C, Goedhart D, Smits PC. Second-generation everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in real-life practice (COMPARE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:201–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park SJ, Park DW, Kim YH, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, Han KH, Park SW, Yun SC, Lee SG, Rha SW, Seong IW, Jeong MH, Hur SH, Lee NH, Yoon J, Yang JY, Lee BK, Choi YJ, Chung WS, Lim DS, Cheong SS, Kim KS, Chae JK, Nah DY, Jeon DS, Seung KB, Jang JS, Park HS, Lee K. Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1374–1382. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim JS, Park SM, Kim BK, Ko YG, Choi D, Hong MK, Seong IW, Kim BO, Gwon HC, Hong BK, Tahk SJ, Park SW, Kim CJ, Jeong MH, Yoon J, Jang Y ECLAT-STEMI Trial Investigators. Efficacy of clotinab in acute myocardial infarction trial-ST elevation myocardial infarction (ECLAT-STEMI) Circ J. 2012;76:405–413. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Byrne RA, Kastrati A, Kufner S, Massberg S, Birkmeier KA, Laugwitz KL, Schulz S, Pache J, Fusaro M, Seyfarth M, Schömig A, Mehilli J Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Test Efficacy of 3 Limus-Eluting Stents (ISAR-TEST-4) Investigators. Randomized, non-inferiority trial of three limus agent-eluting stents with different polymer coatings: the Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Test Efficacy of 3 Limus-Eluting Stents (ISAR-TEST-4) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2441–2449. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, Ameriso SF, Dalby AJ, Fish MP, Fox KA, Lipka LJ, Liu X, Nicolau JC, Ophuis AJ, Paolasso E, Scirica BM, Spinar J, Theroux P, Wiviott SD, Strony J, Murphy SA TRA 2P–TIMI 50 Steering Committee and Investigators. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1404–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, Antman EM, Schneeweiss S, Toscano M, Reisman L, Fernandes J, Spettell C, Lee JL, Levin R, Brennan T, Shrank WH Post-Myocardial Infarction Free Rx Event and Economic Evaluation (MI FREEE) Trial. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2088–2097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mehilli J, Pache J, Abdel-Wahab M, Schulz S, Byrne RA, Tiroch K, Hausleiter J, Seyfarth M, Ott I, Ibrahim T, Fusaro M, Laugwitz KL, Massberg S, Neumann FJ, Richardt G, Schömig A, Kastrati A Is Drug-Eluting-Stenting Associated with Improved Results in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts? (ISAR-CABG) Investigators. Drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents in saphenous vein graft lesions (ISAR-CABG): a randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tricoci P, Huang Z, Held C, Moliterno DJ, Armstrong PW, Van de Werf F, White HD, Aylward PE, Wallentin L, Chen E, Lokhnygina Y, Pei J, Leonardi S, Rorick TL, Kilian AM, Jennings LH, Ambrosio G, Bode C, Cequier A, Cornel JH, Diaz R, Erkan A, Huber K, Hudson MP, Jiang L, Jukema JW, Lewis BS, Lincoff AM, Montalescot G, Nicolau JC, Ogawa H, Pfisterer M, Prieto JC, Ruzyllo W, Sinnaeve PR, Storey RF, Valgimigli M, Whellan DJ, Widimsky P, Strony J, Harrington RA, Mahaffey KW TRACER Investigators. Thrombin-receptor antagonist vorapaxar in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:20–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Massberg S, Byrne RA, Kastrati A, Schulz S, Pache J, Hausleiter J, Ibrahim T, Fusaro M, Ott I, Schömig A, Laugwitz KL, Mehilli J Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Test Efficacy of Sirolimus- and Probucol-Eluting Versus Zotarolimus- Eluting Stents (ISAR-TEST 5) Investigators. Polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting versus new generation zotarolimus-eluting stents in coronary artery disease: the Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Test Efficacy of Sirolimus- and Probucol-Eluting versus Zotarolimus-eluting Stents (ISAR-TEST 5) trial. Circulation. 2011;124:624–632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Serruys PW, Silber S, Garg S, van Geuns RJ, Richardt G, Buszman PE, Kelbaek H, van Boven AJ, Hofma SH, Linke A, Klauss V, Wijns W, Macaya C, Garot P, DiMario C, Manoharan G, Kornowski R, Ischinger T, Bartorelli A, Ronden J, Bressers M, Gobbens P, Negoita M, van Leeuwen F, Windecker S. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:136–146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thiele H, Wöhrle J, Hambrecht R, Rittger H, Birkemeyer R, Lauer B, Neuhaus P, Brosteanu O, Sick P, Wiemer M, Kerber S, Kleinertz K, Eitel I, Desch S, Schuler G. Intracoronary versus intravenous bolus abciximab during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379:923–931. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61872-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schulz S, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, Schuster T, Massberg S, Valina C, Seyfarth M, Pache J, Laugwitz KL, Büttner HJ, Ndrepepa G, Schömig A, Kastrati A Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT) 3A Trial Investigators. ISAR-REACT 3A: a study of reduced dose of unfractionated heparin in biomarker negative patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2482–2491. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KA, Goto S, Murphy SA, Plotnikov AN, Schneider D, Sun X, Verheugt FW, Gibson CM ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 Investigators. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stone GW, Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, Farah B, Dubois CL, Feldman RL, Dens J, Hagiwara N, Allocco DJ, Dawkins KD PLATINUM Trial Investigators. A prospective, randomized evaluation of a novel everolimus-eluting coronary stent: the PLATINUM (a Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Trial to Assess an Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System [PROMUS Element] for the Treatment of Up to Two de Novo Coronary Artery Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]