Abstract

pRb is frequently inactivated in tumours by mutations or phosphorylation. Here, we investigated whether pRb plays a role in obesity. The Arcuate nucleus (ARC) in hypothalamus contains antagonizing POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons for negative and positive energy balance, respectively. Various aspects of ARC neurons are affected in high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity mouse model. Using this model, we show that HFD, as well as pharmacological activation of AMPK, induces pRb phosphorylation and E2F target gene de-repression in ARC neurons. Some affected neurons express POMC; and deleting Rb1 in POMC neurons induces E2F target gene de-repression, cell-cycle re-entry, apoptosis, and a hyperphagia-obesity-diabetes syndrome. These defects can be corrected by combined deletion of E2f1. In contrast, deleting Rb1 in the antagonizing AGRP/NPY neurons shows no effects. Thus, pRb-E2F1 is an obesity suppression mechanism in ARC POMC neurons and HFD-AMPK inhibits this mechanism by phosphorylating pRb in this location.

Keywords: E2F1, high-fat diet, obesity, POMC neurons, pRb phosphorylation

Introduction

The retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and its gene RB1 (Rb1 in mouse) were discovered by their absence in most retinoblastomas due to inherited or sporadic inactivating mutations (Weinberg, 1992). Naturally occurring mutations occur at low frequencies; an RB1-deficient cell becomes detectable only when it grows up to become a tumour mass. Since mouse Rb1−/− embryos die in utero, it is unlikely that an RB1 null individual would be generated by RB1 heterozygous parents. It is therefore unknown whether inactivation of pRb also plays roles in diseases other than in cancer.

Although retinoblastoma is a rare cancer, it is believed that pRb function is lost in most tumours since pRb function can also be inactivated by protein phosphorylation chiefly by cyclin-dependent kinases (Sherr, 1996). In theory, phosphorylation of pRb could occur in larger numbers of cells within a local environment that induces pRb phosphorylation and this kind of pRb inactivation could lead to detectable local cellular pathology with or without the tumour-like expansion of pRb-deficient cells. Here, we used this rationale to investigate whether pRb is physiologically involved in neuronal regulation of energy balance.

Anorexigenic POMC neurons and orexigenic AGRP/NPY neurons co-reside in the Arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the mediobasal hypothalamus and play antagonizing roles to maintain energy balance (Schwartz et al, 2000). An increase in energy store in the form of adipose tissue elevates blood concentration of adipocyte cytokine leptin. Leptin activates POMC neurons but inhibits AGRP/NPY neurons. Activated POMC neurons secrete more neuropeptide α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), which binds to its receptor (MC4R) on downstream neurons to inhibit feeding and promote energy expenditure. AGRP/NPY neurons secrete neuropeptide AGRP to counter α-MSH, and NPY, a most potent physiological appetite stimulator known in mammals. This combined activation of POMC neurons and inhibition of AGRP/NPY neurons corrects the increase in energy store. Inactivating mutations in leptin (ob/ob), its receptor (db/db), or the Pomc gene (Pomc−/−) explain the development of obesity in the most satisfying fashion, but they account for rare cases of obesity in humans.

High-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity (DIO) provides a mechanistically distinct obesity model since it is associated with, counter-intuitively, elevated levels of leptin. This model suggests the development and presence of leptin resistance as the cause of obesity and mimics the vast majority of human obesity cases. Many studies have provided insights into the causes of leptin resistance; some of them reveal that HFD can affect neurons in ARC (Munzberg and Myers, 2005).

For example, after 16 weeks of HFD, leptin-activated pStat3 signalling was reduced and SOCS3, an inhibitor of leptin receptor signalling, was increased in ARC neurons (Munzberg et al, 2004). In another example, HFD led to gliosis as a reaction to neuron injury in ARC (Thaler et al, 2012). Increases in ARC neuron apoptosis in response to HFD has also been reported (Moraes et al, 2009), which might lead to the observed 25% loss of POMC neurons after 8 months of HFD (Thaler et al, 2012). On the other hand, while the DIO model shows leptin resistance, treatment with CNTF (ciliary neurotrophic factor) was able to achieve and maintain reduced body weight because it stimulated neurogenesis in ARC (Kokoeva et al, 2005). HFD reduced ARC neurogenesis as determined by reduced numbers of BrdU-labelled cells (Li et al, 2012; McNay et al, 2012) and Sox-2-labelled cells (Li et al, 2012), further suggesting hypothalamus neurogenesis being important for negative energy balance. In a similar study, however, HFD increased ARC neurogenesis, and depleting proliferating cells with focal radiation protected the mice from HFD-induced obesity, implicating ARC neurogenesis in promoting positive energy balance (Lee et al, 2012). These findings uncovered connections between HFD and ARC neuron homeostasis and, at the same time, demonstrate the pressing need for further studies.

Two best-established mechanisms of tumorigenesis following loss of pRb are de-repression of E2F transcription factors (whose target genes promote proliferation) (Trimarchi and Lees, 2002) and de-repression of Skp2 ubiquitin ligase (which targets p27 for degradation to promote survival of pRb-deficient cells) (Wang et al, 2010). Since some of the ARC alterations by HFD relate to cell proliferation and survival, we investigated whether pRb in ARC neurons was preferentially susceptible to effects of HFD. Postnatal neurons are generally postmitotic and pRb is expected to be in the hypophosphorylated form to repress E2F. We hypothesized that HFD may inhibit pRb function by inducing its phosphorylation. If it were functionally inhibitory, then the phosphorylation would be accompanied by de-repression of E2F target gene expression. If these effects occurred to many neurons in ARC, then they would become detectable with or without the expansion of the affected cells. These findings would then indicate that inhibition of pRb function is physiologically involved in HFD DIO. Here, we report that HFD could induce pRb phosphorylation and E2F target gene de-repression in most neurons in ARC.

The co-residence of antagonizing POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons in ARC poses a logistic question about the purpose of pRb phosphorylation in this location. If HFD indiscriminately induces pRb phosphorylation in ARC neurons and POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons were similarly compromised by pRb phosphorylation, which direction would the energy balance be tilted? These questions must be addressed by neuron-specific inactivation of pRb, which has been made possible by previously established Pomc-Cre and Agrp-Cre lines. Here, we used these lines to delete Rb1 in POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons, and found that Rb1 is required for maintaining POMC neurons but is dispensable in AGRP/NPY neurons. Thus, the outcome of widespread phosphorylation and inhibition of pRb in ARC would reflect the impairment of POMC neurons.

Finally, we investigated the functional mechanism for the required role of Rb1 in POMC neurons. We show that E2f1 is not required for the development and maintenance of POMC neurons but must be repressed by Rb1 for POMC neuron maintenance. Together, these studies suggest that pRb-E2F1 is a uniquely important mechanism in POMC neurons in ARC, is vulnerable to HFD effects in this location, and is an attractive intervention target for the ill effects of HFD in ARC.

Results

Long-term HFD induces pRb phosphorylation in ARC neurons

pRb contains 16 Ser or Thr residues in phosphorylation consensus sequences for cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK, S/TPxK/R, ‘x’ is any residue), 8 of them have been shown to modulate pRb-E2F interaction. pRb sequences can be divided into three parts: the N terminus (1–380, human pRb sequences), the Pocket (380–787), and the C terminus (787–928). Mapping experiments and X-ray crystal structures show that pRb Pocket interacts with the transactivation domain (TD) at the C termini of E2F proteins, and pRb C terminus interacts with the Coiled Coil and Marked Box domains (CM) in the centre of E2F proteins. Phosphorylation of the T356/T373 cluster and the S608/S612 cluster dissociates the Pocket–TD interaction, while phosphorylation of the S788/S795 cluster and the T821/T826 cluster destabilizes the C terminus–CM interaction (Rubin et al, 2005). Overall, however, phosphorylation of pRb is a progressive and cumulative process through various combinations of phosphorylation sites, resulting in progressive and cumulative disruption of pRb-E2F interactions leading to gradual activation of E2F in cell-cycle progression from G1 to S phase.

We used three male C57BL6 mice that had been on HFD for 11 months to determine whether pRb phosphorylation in ARC was altered compared with three age- and sex-matched mice on Chow diet. BW was 55–60 g for HFD mice and 30–35 g for Chow mice. We used a rabbit antibody specific for Ser608 phosphorylated pRb to perform immunofluorescence staining as previous reported (Kim et al, 2007). pRb is a nuclear protein; positive staining by the pRbS608p antibody is nuclear. As shown in Figure 1B, pRbS608p antibody showed widespread nuclear staining in ARC of the HFD mice that merged with most of the co-stained NeuN (a neuronal nuclear marker) positive nuclei. In comparison, control Chow mice showed few positive staining that did not merge with NeuN (Figure 1A). We found that this HFD-associated pRb phosphorylation is enriched in ARC. As an example, the granular zone of dentate gyrus (DG) contains densely packed neurons as shown by NeuN stain; but none of them showed positive co-stain with pRbS608p in the same HFD brain sections (Supplementary Figure S1A). When pRbS608p co-staining was performed with a GFAP antibody (an astrocyte marker), most nuclear pRbS608 staining in HFD brains did not merge with GFAP staining (Supplementary Figure S1B). We conclude that long-term HFD induced pRb phosphorylation in ARC neurons, but not in DG neurons.

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of pRb and de-repression of cyclin A and E2F1 in ARC neurons in response to HFD or AICAR. (A, B) ARC from C57/Bl wild-type mice fed on HFD for 11 months and matched mice fed on Chow co-stained with antibodies to pRbS608p and NeuN, as marked. (C) ARC from wild-type mice at 2 and 6 h after third ventricle injection of ACSF or AICAR stained with antibodies to pRbS608p, E2F1, or cyclin A, as marked. (D) ARC from Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP mice fed on HFD or Chow for 8 weeks following their 1 month birthday were stained with the indicated antibodies. Direct YFP was photographed in green. (E) Quantification of stain-positive cells versus YFP-positive cells in ARC presented as %, from samples in (D) and Supplementary Figure S2C (n=3). Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. Unpaired t-tests were performed, *P<0.05, **P<0.005 and ***P<0.0005. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Pharmacological activation of AMPK induces pRb phosphorylation and E2F de-repression in ARC

HFD induces a wide spectrum of effects, including locally in ARC such as inflammatory injury (Thaler et al, 2012). We considered the possibility that these tissue injuries might result in non-specific binding of the pRbS608p antibody to ARC. We sought to identify a stimulus that could induce pRb phosphorylation in ARC independent of HFD but might mediate pRb phosphorylation downstream of HFD. We considered AMPK as a candidate. In Chow mice, leptin can inhibit AMPK in ARC as one mechanism to inhibit feeding but in HFD-induced obesity, leptin lost this ability resulting in constitutively activated AMPK (Martin et al, 2006; Steinberg et al, 2006). Conversely in CaMKK2 knockout mice, hypothalamic activation of AMPK is defective, and these mice are resistant to HFD-induced obesity (Anderson et al, 2008). AMPK substrates include pRb (Dasgupta and Milbrandt, 2009). AMPK can be specifically activated by AICAR, which can be administered directly to the ARC of Chow mice via third ventricle intra-cerebral-ventricular (i.c.v.) injection.

Also, if pRbS608p antibody detected true pRb phosphorylation in ARC, positive staining by pRbS608p antibody might be accompanied by detection of E2F target gene de-repression as functional consequences of pRb inactivation.

We therefore performed AICAR i.c.v. experiments with Chow mice and examined ARC at 2 and 6 h time points for positive staining with the pRbS608p antibody and with antibodies to cyclin A and E2F1, two established E2F target genes (Figure 1C). The results show that pRbS608p staining was negative in control ACSF injection at both time points and in AICAR injection at 2 h point. At 6 h, AICAR-injected ARC showed positive pRbS608p staining. Further, both negative and positive pRbS608p staining correlated with negative and positive staining with cyclin A and E2F1 antibodies in consecutive sections. We also performed ISH for cyclin A and observed positive staining in ARC at 6 h post AICAR injection but not post ACSF injection, while some positive staining was observed in DG in both AICAR- and ACSF-injected brains (Supplementary Figure S1C). These findings document that AICAR can induce positive staining of ARC with the pRbS608p antibody independent of HFD and this positive staining was associated with positive staining for E2F target genes E2F1 and cyclin A.

Since hypothalamus AMPK activity is regulated by fasting and refeeding (Minokoshi et al, 2004), our AICAR injection experiments suggested that ARC of fasted mice should contain more phosphorylated pRb than ARC of refed mice. Experiments shown in Supplementary Figure S1D tested and confirmed this expectation. Positive staining by the pRbS608p antibody of ARC was observed after a 24-h fasting, which was, remarkably, reverted to baseline negative staining following a 3-h refeeding.

Previous studies showed that ARC AMPK is constitutively active in HFD-induced obesity; our findings show that pharmacological activation of AMPK can induce pRb phosphorylation in ARC, suggesting that HFD might induce pRb phosphorylation via AMPK. S804 (S811 in human) of pRb is in a combined CDK and AMPK phosphorylation consensus (IxPxxSPxKI, ‘P’ and ‘K’ are CDK consensus; ‘I’ and ‘P’ are AMPK consensus). Immunopurified AMPK can phosphorylate S804 (S811 in human) of pRb in vitro (Dasgupta and Milbrandt, 2009). However, structural studies of pRb-E2F interaction suggested that phosphorylation of S811 did not affect pRb-E2F binding (Rubin et al, 2005). It is likely that AMPK initiates pRb phosphorylation, while cyclin-dependent kinases perform most of the phosphorylation on sites that disrupt pRb-E2F interaction to induce de-repression of E2F target gene expression.

HFD induces pRb phosphorylation and E2F de-repression in ARC POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons

We generated Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP mice (on mixed strain background) for HFD to determine the identities of ARC neurons with pRb phosphorylation by HFD. Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP marks POMC neurons and up to a quarter of AGRP/NPY neurons in ARC (Padilla et al, 2010). We also determined the length of HFD necessary to induce pRb phosphorylation in ARC and whether pRb phosphorylation was associated with E2F target gene de-repression. We started HFD when the mice reached the age of 4 weeks. At the end of 8-week treatment, HFD mice gained on average 10% more weight than matched Chow mice. As shown in Figure 1D, positive staining for pRbS608p, E2F1, and cyclin A was detected in ARC at 8 weeks after HFD but not Chow. Similarly to AICAR 3v i.c.v., increased cyclin A expression in ARC, but not in DG, was also detected by ISH (Supplementary Figure S2A). With another set of wild-type mice on Chow or HFD for 8 weeks, we detected increased E2F1 expression on western blot of their hypothalami using an anti-E2F1 antibody that was validated for its ability to detect increased E2F1 expression following deletion of Rb1 in E2f1 WT MEF but not in E2f1 KO MEF (Supplementary Figure S2B).

Quantification and time course experiments (Figure 1E; Supplementary Figure S2C) showed gradually increased staining for these three antibodies from 1 week of HFD to about half of the Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP marked ARC neurons. We noted that positive staining for E2F1 and cyclin A showed faster kinetics than pRbS608p staining, suggesting that de-repression of certain E2F target genes could take place when pRb was partially phosphorylated. These results reveal that pRb function could be progressively inhibited in ARC neurons marked by Pomc-Cre in response to HFD in a timeframe of 2 months.

Rb1 is required for POMC neuron maintenance

Our finding that HFD induced pRb phosphorylation and E2F target gene de-repression in ARC POMC and some AGRP/NPY neurons suggests that pRb inactivation may be an important causal mechanism for ARC neuron malfunction in obesity development by HFD. Alternatively, pRb phosphorylation and E2F de-repression could be secondary to neuron injuries by HFD as described in Introduction. To distinguish between these two alternatives, we used targeted Rb1 deletion to directly determine the roles of Rb1 in defined neurons in ARC of mice on Chow.

Previous studies suggested that pRb and its family member p107 function to activate the Pomc promoter (Batsche et al, 2005a, 2005b). We first deleted Rb1 in pan-neuronal progenitors using Nestin-Cre;Rb1lox/lox, and found that Rb1 was not required for the activation of Pomc gene expression in embryogenesis (unpublished results). We then generated Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice, which were born in normal Mendelian frequency. Assuming that POMC expression continued after Rb1 deletion, we used POMC IHC to visualize POMC neurons in ARC. As shown in Figure 2A, POMC neurons in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice appeared normal at 1 week of age. However, POMC neuron numbers in ARC reduced significantly from 4 weeks of age (Figure 2A and B), and the remaining POMC neurons progressively increased their soma sizes (Figure 2A and C). It is of note that anti-POMC IHC experiments do not detect POMC neurons that stopped expressing POMC following Rb1 deletion. We addressed this issue with RosaYFP marking in Supplementary Figure S3G and H and some of the later studies below.

Figure 2.

Rb1 is required for POMC neuron maintenance. (A) ARC POMC neurons were visualized by anti-POMC stain in indicated mice; ARC sections were from Bregma −1.75 to −1.8 mm. (B) POMC neuron numbers were counted on sections at comparable Bregma positions. ARC1 at about −1.34, ARC2 about −1.58, ARC3 about −1.75 (n=3). (C) Soma areas of ARC POMC neurons were measured in 1-, 4-, 8-week-old mice (n=3). (D) POMC immunoreactive axon fibres in PVH of 8-week-old mice and their quantification based on POMC stain density (n=3). (E) Control mice densities were set as 1.0. (F) POMC expression was determined by RT–qPCR of hypothalamus (n=6). POMC/Actin ratios in control mice were set as 1.0. (G) Hypothalamus content of POMC pre-peptide, α-MSH, and β-endorphin (n=6). Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. Unpaired t-test was performed, *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005. Scale bars: 200 μm.

We also used POMC stain to investigate whether Rb1-deficient POMC neurons were able to extend axons to arborize PVH, which is located anterior (∼2 mm) and rosterior (∼1 mm) to ARC. Figure 2D shows that the characteristic outlines of PVH, as visualized by POMC stain, were indistinguishable between Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox and control mice, but the stain intensity was significantly reduced (Figure 2D and E). Similar results were obtained for aborization to DMH, which is rosterior (∼1 mm) to ARC. To quantify POMC expression output, we performed RT–qPCR on hypothalamus and found that POMC expression was slightly elevated at 1 week of age but significantly reduced by 5 weeks of age (Figure 2F). We measured the amounts of POMC pre-peptide and its proteolytically processed products, α-MSH and β-endorphin, in the hypothalamus. Figure 2G shows that the amounts of these peptides were reduced, but remained proportional to the reduction in POMC pre-peptide therefore suggesting that these proteolytic processing steps were preserved in the absence of Rb1. The consequences of Rb1 deletion in AGRP/NPY neurons were examined in Figure 6 below.

The Pomc-Cre line expresses Cre in a number of sites in addition to ARC, including the pituitary gland, the NTS, and the DG. We used Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP to examine the effects of Rb1 deletion in these additional sites and found that deleting Rb1 in pituitary melanotrophs is tumorigenic as expected, while POMC neurons in NTS and newborn neurons in DG appear unaffected by Rb1 deletion (please see Supplementary Figure S3 for more details). Thus, the observed effects of Rb1 deletion in POMC neurons are neuron type specific.

We conclude that Rb1 is not required for ARC POMC neuron development but plays important maintenance roles in them starting at a young age. Without Rb1, POMC neurons undergo progressive loss while maintaining the ability to express POMC, to process POMC pre-peptide, and to arborize distant sites. Nevertheless, due to reduction in POMC neuron numbers, POMC output after 1 week of age was significantly reduced.

Pomc-Cre;Rb1 lox/lox mice develop a hyperphagia-obesity-diabetes syndrome

We determined the effects of Pomc-Cre mediated deletion of Rb1 on energy balance. Figure 3A shows that Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice were significantly heavier than control mice from 1 month of age. Since increases in fat % (Figure 3B) can mostly account for the increases in body weight, these mice were obese, although they were also larger as shown by nasoanal length (Figure 3C). Food intake was significantly increased in these mice (Figure 3D), providing an explanation for body weight gain. Serum leptin concentrations were greatly increased (Figure 3E), consistent with their high fat % and indicating a leptin-resistant state. Obesity is often associated with diabetes; insulin concentrations were increased starting at 2 months of age (Figure 3F). By 4 months, Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice exhibited frank diabetes with high blood glucose levels (Figure 3G) and glucose intolerance (Figure 3H). These characteristics of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice suggest that targeted deletion of Rb1 in ARC POMC neurons could essentially reproduce HFD DIO.

Figure 3.

Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice developed a hyperphagia-obesity-diabetes syndrome, and lost melanocortinergic tone in the hypothalamus. (A) Body weights of Rb1lox/lox and Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (n=5–12 for various age points). (B) Fat % of the mice in (A). (C) Nasoanal length. (D) Daily food intake during light and dark cycles (n=4). (E) Following an overnight fasting, tail vein blood was collected to measure leptin levels (n=5). (F) Fasting serum insulin concentration (n=4–8). (G) Fasting blood glucose concentration (n=6–8). (H) Glucose tolerance test was performed at 4 months of age (n=3). (I) Cumulative food intake measured for 6 h following i.c.v. administration of ACSF or SHU9119 (n=5–6). (J) Cumulative food intake measured for 3.5 h following i.c.v. administration of ACSF or PYY (n=5–6). (K) Cumulative food intake in response to i.c.v. administration of ACSF or MTII (n=5–6). Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. Unpaired t-tests were performed, *P<0.05, **P<0.005 and ***P<0.0005. For (I–K), # refers to differences in the same genotypes performed with paired t-test, #P<0.05 and ##P<0.005.

Although the above body phenotypes of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice were consistent with POMC neuron defects by Rb1 deletion in them, we cannot be certain that these defects were completely responsible for the body phenotypes since defects in other cells that experienced Pomc-Cre expression (see Supplementary Figure S3) could be involved. In Supplementary Figure S4, we show that Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;p27T187A/T187A mice and Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;Skp2+/− mice did not develop pituitary tumours but still show POMC neuron defects and obesity, indicating that POMC neuron defects, rather than pituitary tumours, caused obesity in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice.

We determined the functional status of the POMC axis in hypothalamus regulation of food intake in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice. To do so, we measured the responses of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice to third ventricle i.c.v. of melanocortin receptor antagonist SHU9119. We found that injection of SHU9119 increased food intake in control mice (Figure 3I), demonstrating that there is normally a melanocortin-mediated inhibition of food intake (i.e., presence of a melanocortinergic tone). In comparison, same amount of SHU9119 did not increase food intake in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice, indicating a lack of melanocortinergic tone in them. To test whether the mutant mice could still be stimulated to increase food intake, we injected the orexigenic peptide YY (PYY) (Hagan, 2002) and observed a significant increase in food intake in both groups (Figure 3J). These findings demonstrate that the central melanocotin system was functioning inadequately in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice.

To test the functions of α-MSH target neurons in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice, we injected melanocortin receptor agonist MT-II. Since MT-II administration significantly suppressed food intake in both genotypes (Figure 3K), melanocortin target neurons in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice remained functional. These findings, together with well-established roles of POMC neurons for negative energy balance, built a compelling case that reduction in α-MSH levels in the hypothalamus, as a result of POMC neurons defects by Rb1 deletion, caused obesity of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice.

Rb1 is required to maintain ARC POMC neurons postmitotic postnatally

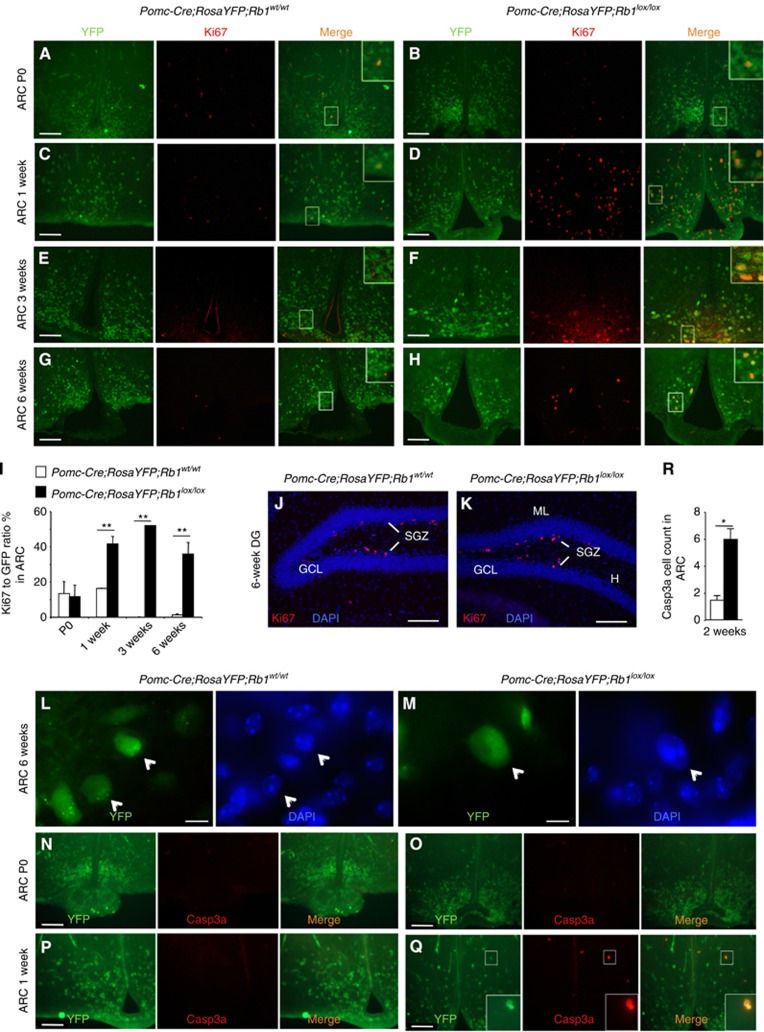

To study the cellular mechanisms of pRb function in POMC neurons, we performed Ki67 staining to determine the proliferation status of Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP marked ARC neurons. In newborns (P 0), we detected a few Ki67-positive cells in control and Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice, some of which merged with YFP-positive cells (Figure 4A and B). These results indicate that most cells in ARC have exited cell cycle at birth and deletion of Rb1 did not prevent cell-cycle exit of POMC neurons. Remarkably, a burst of Ki67-positive cells emerged in the ARC of 1-week-old Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice, while control littermates remained mostly negative for Ki67 in this region. The majority of Ki67-positive cells merged with YFP-positive cells, and amounted to >40% of YFP-positive cells (Figure 4C, D). This finding reveals that Rb1 is required for maintaining ARC POMC neurons in a postmitotic state postnatally. This Ki67-positive status persisted at 3 and 6 weeks of age (Figure 4E–I).

Figure 4.

Proliferation, nuclear morphology, and apoptosis in ARC and DG of Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice. (A–H) ARC sections with native YFP (green) and anti-Ki67 stain at the indicated age (P0=newborn). (I) Quantification of Ki67-positive cells as ratio to YFP-positive cells (n=3). (J, K) Sections containing DG stained with DAPI and anti-Ki67. (L, M) ARC sections with native YFP (green) and DAPI stain. White arrowheads point to the same cells in each green-blue pairs. (N–Q) ARC sections with native YFP (green) and anti-Casp3a stain. (R) Quantification of Casp3a-positive cells in ARC (n=3). Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. Unpaired t-test was performed, *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: 100 μm (10 μm for L and M).

We next examined postnatal born neurons in DG, which enter and exit the cell cycle postnatally. Results in Figure 4J and K revealed Ki67-positive cells in the SGZ (these cells are being born and Pomc-Cre is not yet expressed in them). After they were born, Pomc-Cre is expressed in them and the newborn neurons are permanently labelled with RosaYFP in Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP mice (Supplementary Figure S3K). Since, unlike RosaYFP labelling, there are no Ki67-positive cells in GCL of Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice, Rb1 is not required for maintaining the postmitotic status of these postnatal born neurons. Thus, cell-cycle re-entry is also a neuron type-specific effect of Rb1 deletion with Pomc-Cre.

We performed staining for pHH3 to determine whether cell-cycle re-entry of ARC neurons progressed to mitosis but did not detect any (data not shown). We observed with Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP and DAPI staining that the enlarged neurons in Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP; Rb1lox/lox mice contained enlarged nuclei (Figure 4L and M). These two types of results suggest that cell-cycle re-entry of ARC POMC neurons failed to progress to cell division.

We performed staining for Caspase3a to determine whether the reduction in ARC POMC neurons was associated with apoptosis. Results shown in Figure 4P–R reveal increases in Caspase3a-positive cells (overlapping with RosaYFP-positive cells) in the ARC of 1- to 2-week-old Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice. Since Caspase3a-positive cells were not detected in P0 Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice, neuron apoptosis at 1 week of age was associated with the abnormal and blunted cell-cycle re-entry. We conclude from these experiments that Rb1 is required for maintaining ARC POMC neurons postmitotic postnatally. However, cell-cycle re-entry of Rb1-deficient POMC neurons does not lead to neuron proliferation but to cell-cycle block in G2/M and apoptosis.

Repression of E2F1 is a major function of pRb in POMC neurons

A large number of pRb targets have been identified. When a pRb target is physiologically relevant, its deregulation following Rb1 loss would be responsible for the defects caused by Rb1 deletion. Here, we investigated whether deregulation of the two best-established Rb1 targets, pRb-E2F and pRb-Skp2-p27, are the underlying mechanisms for POMC neuron defects. We introduced the p27T187A knockin mutation (p27T187A/T187A) or deleted one allele of Skp2 (Skp2+/−) in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice and found that pituitary tumorigenesis was blocked as expected (Supplementary Figure S4Ba and Ca, compared with Aabc). The pituitary IL was mostly ablated in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;p27T187A/T187A mice, but was mostly retained at the WT sizes in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;Skp2+/− mice. In both cases, the POMC neuron losses (Supplementary Figure S4Bbc, D, Cbc and G) and obesity phenotypes (Supplementary Figure S4E, F, H, and I) were not corrected. These findings indicate that Skp2 deregulation was not the mechanism for, and pituitary tumours was not the cause of, obesity of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice.

E2F is a family of eight members. pRb primarily binds and represses the ‘activator’ sub-family of E2F1, 2, and 3, whose target genes include those encoding for DNA replication enzymes and cyclin-dependent kinases. Figure 5A, B shows that expression of the DNA replication licensing factor MCM3 and cyclin A, both are E2F target genes, was not detectable in ARC of 1-week-old control mice but became positive in about half of RosaYFP marked cells in Pomc-Cre;RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice, demonstrating that E2F target genes were postnatally de-repressed when Rb1 was absent.

Figure 5.

pRb maintained POMC neurons postmitotic postnatally by repressing E2F1. ARC sections with YFP (pictured in green) and anti-MCM3 (A–C) or anti-cyclin A (E–G) stain of the indicated mice at 1 week of age. Consecutive sections of the same brains were stained with anti-Ki67 (I–K). (D, H, L) Quantification of stain-positive cells as ratio of YFP-positive cells (n=3). (M–P) ARC POMC neurons of the indicated mice were visualized by POMC stain and counted (n=3) (Q). Scale bar: 100 μm. Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. Unpaired t-test was performed *P<0.05, ***P<0.0005.

E2F1 is special in being able to induce apoptosis in addition to S-phase entry. Since POMC neurons in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/loxmice exhibited S-phase re-entry and apoptosis, we generated Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;E2f1−/− mice to test the hypothesis that repression of E2F1 is the major functional mechanism of pRb in POMC neurons. Figure 5C, D shows that ectopic expression of the E2F target genes following Rb1 deletion was largely (MCM3) or completely (cyclin A) corrected with combined deletion of E2f1. We further show that cell-cycle re-entry of POMC neurons at 1 week of age in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/loxmice was completely prevented by combined deletion of E2f1 (Figure 5I–L). Caspase3a, which was increased in ARC POMC neurons following Rb1 deletion (Figure 4P–R) was undetectable in the ARC of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;E2f1−/− mice (data not shown). When POMC neurons were examined directly with POMC staining, the results show that the reduction in POMC neuron numbers (Figure 5M–Q), in POMC neuron axon projection to PVH (Supplementary Figure S5A–D), and in POMC expression in hypothalamus (Supplementary Figure S5E) were all completely or nearly completely corrected by combined deletion of E2f1.

Deletion of E2f1 delayed pituitary tumorigenesis in Rb1+/− mice (Yamasaki et al, 1998). In Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;E2f1−/− mice, pituitary IL was of WT sizes at 8 weeks of age (Supplementary Figure S5Fb, compare Supplementary Figure S4Aabc). When examined at 6 months of age, however, Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox;E2f1−/− mice still developed macroscopic IL tumours. These findings together demonstrate that Rb1 represses E2f1 to suppress tumorigenesis in melanotrophs in the pituitary and to maintain POMC neurons postnatally in the hypothalamus. Importantly, E2f1 KO mice show normal pituitary (Supplementary Figure S5Fa), normal POMC expression in hypothalamus (Supplementary Figure S5E), and normal POMC neuron appearance and numbers in ARC (Figure 5O and Q). Thus, E2f1 is not required for the development and maintenance of melanotrophs and POMC neurons, but must be repressed by pRb to prevent melanotroph tumorigenesis and to maintain POMC neurons.

Combined E2f1 deletion also prevented obesity development in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (Supplementary Figure S5G). This corrective effect was nearly complete for body weight and fat % in 1-month-old mice. Although Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/loxE2f1−/− mice still showed significant fat accumulation compared to control mice when they grew to 2 and 3 months of age, the correction from Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice remained significant at 2 months and just missed significance (P=0.056) at 3 months. The correction of body weight gain appeared more durable in these periods. The exact mechanisms for these body phenotype changes, however, could be multi-fold, since E2f1 deletion also delayed pituitary tumorigenesis and E2f1−/− mice showed low adiposity on Chow feed and resisted obesity development on HFD (Fajas et al, 2002).

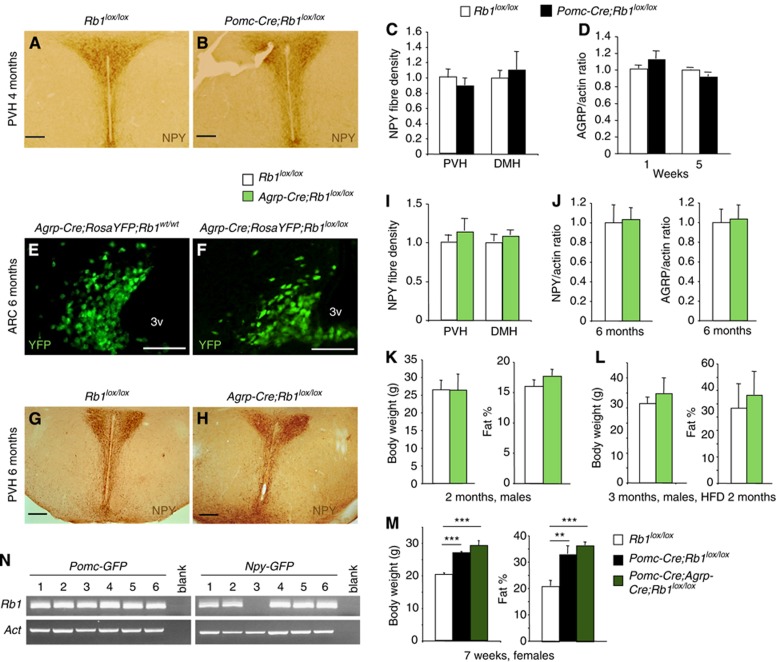

Deletion of Rb1 in AGRP/NPY neurons does not cause neuron defects or body weight changes

Since a quarter of AGRP/NPY neurons originate from Pomc-expressing progenitors (Padilla et al, 2010) and therefore also incurred Rb1 deletion in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice, we first examined the status of AGRP/NPY neurons in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice. Figure 6A–C shows that NPY stain in the projection sites in PVH was not different between testing and control mice. Merge of immunofluorescence co-staining for POMC and NPY demonstrated reduction of POMC stain, but not NPY stain, in the ARC of Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (Supplementary Figure S6A). RT–qPCR revealed that expression of NPY and AGRP was not different in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice compared to control mice (Figure 6D; Supplementary Figure S6B). These findings provided the first indications that Rb1 deletion by Pomc-Cre affected POMC neurons but spared AGRP/NPY neurons.

Figure 6.

Rb1 is dispensable in AGRP/NPY neurons. The role of Rb1 in AGRP/NPY neurons was studied in three lines of mice. (A–C) NPY immunoreactive axons in PVH of 4-month-old Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox and control mice, and quantification of density of NPY stained axon fibres in PVH and DMH (n=3). (D) AGRP expression in hypothalamus was measured by RT–qPCR in 1- and 5-week-old Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox and control mice (n=3). Values in control mice were set as 1.0. (E, F) ARC sections of the indicated genotypes. AGRP/NPY neurons were visualized with direct YFP (pictured in green). (G–I) NPY immunoreactive axons in PVH of 6-month-old mice of the indicated genotypes and quantification of density of NPY stained axon fibres in PVH and DMH (n=3). (J) AGRP and NPY expression was determined by RT–qPCR (n=6). Values in control mice were set as 1.0. (K) Body weight and fat % of 2-month-old male mice on Chow. (L) Body weight and fat % of 3-month-old male mice that were on HFD for the last 2 months. (M) Body weight and fat % of 7-week-old female mice of the indicated genotypes (n=3–6). (N) Single cell RT–PCR detected Rb1 expression in POMC neurons and AGRP/NPY neurons. Data are expressed as average±s.e.m. **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005. Scale bars: 100 μm.

We next used an Agrp-Cre line to delete Rb1 in AGRP neurons. In Figure 6E and F, RosaYFP showed no cell number reduction or size enlargement in the ARC of Agrp-Cre:RosaYFP;Rb1lox/lox mice. NPY stain did not decrease in PVH of Agrp-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (Figure 6G–I), and RT–qPCR did not reveal any reduction in expression levels of NPY or AGRP in the hypothalamus of Agrp-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (Figure 6J). AGRP/NPY neurons maintained their postmitotic state in the absence of Rb1 (data not shown). Body weight and fat % were normal in Agrp-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice on Chow (Figure 6K), and they gained similar amount of body weight and fat on HFD (Figure 6L). Thus, Rb1 is dispensable for AGRP/NPY neuron maintenance and, consistently, its loss in AGRP/NPY neurons had no disruptive effects on energy balance.

To further determine the role of Rb1 in body weight control by the antagonizing POMC neurons and AGRP/NPY neurons, we deleted Rb1 in both of them; and found that Pomc-Cre;Agrp-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice were as obese as Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice (Figure 6M). These results suggest that if pRb was inactivated in ARC indiscriminately of anorexigenic POMC neurons and orexigenic AGRP/NPY neurons, such as by HFD induced pRb phosphorylation (Figure 1) the consequence would be obesity.

To investigate the possibility that Rb1 was not expressed in AGRP/NPY neurons, as an explanation for its dispensability in them, we used Pomc-GFP and Npy-GFP mice to mark and isolate POMC and AGRP/NPY neurons, respectively, for single cell RT–PCR to detect Rb1 expression. This experiment detected Rb1 expression in both types of neurons (Figure 6N). Another possibility for further study is that pRb family member p107/p130 may express highly in AGRP/NPY neurons to compensate for the loss of Rb1.

Discussion

DIO mouse model mimics the majority of human obesity cases in that the obesity is caused by over-nutrition and increased leptin is unable to produce an anorexigenic effect. Recent research has begun to connect these two aspects by showing that HFD can cause injuries to ARC neurons. Since ARC neurons play important roles in the regulation of food intake and energy expenditure, a better understanding of how HFD causes injuries to them may hold the key to a better understanding of how HFD induces obesity. Our discovery that HFD can inhibit pRb and de-repress E2F target genes in ARC neurons links HFD to perhaps the most fundamental mechanism for maintaining cellular homeostasis. The distinctly different roles of Rb1 in anorexigenic POMC neurons (essential for maintenance) and orexigenic AGRP/NPY neurons (not required for maintenance) provide a straightforward basis on which HFD’s induction of pRb phosphorylation in ARC could promote obesity.

The tumour suppressor role of pRb in pituitary melanotrophs provides a contrast for us to study the non-tumour suppressor role of pRb in ARC neurons in the same Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice. In the absence of Rb1, POMC neurons still properly differentiated and exited the cell cycle at birth. However, these cells were unable to maintain their postmitotic state and re-entered the cell cycle within 1 week after birth. This defect is consistent with the tumour suppressor function of Rb1. The events following cell-cycle re-entry in POMC neurons are opposite from the tumour suppressor role of pRb. Instead of progressing to cell division and expansion, Rb1-deficient POMC neurons show enlarged nuclei and apoptosis.

Further studies using the ‘rescue-by-combined-deletion’ approach help shed light on the outcomes of Rb1 deletion in POMC neurons. Since E2F1, 2, and 3 (the three members in the activating E2F subgroup) share overlapping functions and similar physical interactions with pRb, the near complete correction of POMC neuron defects by E2f1 deletion would suggest that E2f2 and E2f3 might not be expressed in POMC neurons and/or might not increase their expression to compensate for the loss of E2f1. E2f1 therefore is the major source of activating E2F activity in POMC neurons. However, E2f1 KO mice do not show detectable defects in ARC POMC neurons, indicating that E2f1 is not required for POMC neuron development and maintenance, or E2f1’s role in these aspects of POMC neurons can be compensated by other E2F members. It is therefore possible that, when E2F1 is de-repressed by the loss of Rb1, the de-repressed E2F1 may have an abnormally activated function that is not shared with other E2Fs, and is disruptive to POMC neuron homeostasis.

Indeed, apoptotic activity is generally regarded as unique to E2F1. When E2F1, 2, and 3 were ectopically expressed at similar protein levels in quiescent REF52 cells, only E2F1 could induce apoptosis (Hallstrom and Nevins, 2003). pRb contains a binding domain (792 to the C terminus) specifically for E2F1 (the binding sequences are in the N terminal 374 aa of the 437 full-length E2F1) to inhibit E2F1’s apoptotic function (Dick and Dyson, 2003). We therefore propose that E2F1 might be highly expressed in POMC neurons and repression of E2F1 by pRb is a critical mechanism for maintaining POMC neurons postnatally. A notable component within this maintenance mechanism is that E2F1 is not required for POMC neuron development and maintenance. Since this pRb-E2F1 pathway appears to be vulnerable to inhibition by HFD’s effects in ARC, an activated E2F1 is potentially causative of central positive energy imbalance and therefore an attractive target for the prevention and treatment of DIO.

AMPK regulates metabolism based on the cell’s fuel levels. In the hypothalamus, AMPK is activated by fasting and deactivated by subsequent refeeding. Activation of AMPK in hypothalamus promotes food intake, and at least part of leptin’s anorexigenic effects are mediated by inhibiting hypothalamus AMPK (Andersson et al, 2004; Minokoshi et al, 2004). In HFD-induced obesity, leptin loses this effect, leaving AMPK constitutively activated (Martin et al, 2006; Steinberg et al, 2006). Since our data show that pharmacological activation of AMPK in ARC can induce pRb phosphorylation and E2F target gene de-repression, hypothalamus AMPK might be the upstream kinase for pRb in HFD fed mice, likely function in an HFD-AMPK-pRb-E2F1 pathway in POMC neurons to promote positive energy imbalance.

Using overexpression of E2F1 in REF53 cells, the AMPKα2 subunit was identified as an E2F1 target gene (Hallstrom et al, 2008). Such a link between E2F1 and AMPK, if proven in hypothalamus, together with the HFD-AMPK-pRb-E2F1 pathway discussed above, would suggest a feed-forward HFD-AMPK-pRb-E2F1-AMPK loop. AMPK could be activated to initiate this loop by low energy status signals such as fasting or by resisting downregulation under HFD. Once initiated, this loop may autonomously enhance itself leading to higher AMPK activity to promote eating and higher E2F1 activity to disrupt POMC neuron homeostasis, both of which can contribute to DIO. In the opposite direction, inhibition of E2F1 may have synergistic effects in dampening this feed-forward loop with inhibition of AMPK.

Materials and methods

Animals and genotyping

All procedures were reviewed and approved by Einstein Animal Care Committee, conforming to accepted standards of humane animal care. Mice were maintained on Picolab chow 5053 (minimum protein 20%, minimum fat 4.5%; PMI Nutrition International). Rb1lox/lox mice (Sage et al, 2003), Nestin-Cre mice (Betz et al, 1996), Pomc-Cre mice (Balthasar et al, 2004), Agrp-Cre mice (Tong et al, 2008), Rosa26EYFP mice (Srinivas et al, 2001), Skp2−/− mice (Nakayama et al, 2000), p27T187A/T187A mice (Malek et al, 2001), E2f1−/− mice (Yamasaki et al, 1998), Pomc-GFP mice (The Jackson Lab, MGI Ref ID J:120992), and Npy-GFP mice (The Jackson Lab, MGI Ref ID J:120993) have been described. Genotyping primers are listed in Supplementary data.

Initial studies of pRb phosphorylation in ARC in response to HFD (Figure 1A and B; Supplementary Figure S1A and B) used WT C57Bl6 mice. All transgenic mice used in later studies were maintained and mated as mixed background hybrids, including C57Bl6, 129Sv, and FBV. We did not select for or against any particular strain background in the course of our studies. Pituitary tumours, POMC neuron loss, and obesity in Pomc-Cre;Rb1lox/lox mice and, in contrast, lack of AGRP/NPY neuron defects, and lack of obesity in Agrp-Cre;Rb1loxlox mice are robust phenotypes among littermates and among large numbers of litters. The block of pituitary tumours, the non-correction of POMC neuron defects and obesity by Skp2+/− and p27T187A/T187A are also robust phenotypes. The delay in pituitary tumour development and correction of POMC neuron defects by E2f1−/− are robust, while the correction of obesity by E2f1−/− is less robust and subject to complex interpretations as discussed in the text.

HFD treatment

Regular chow (3.75 kcal/g, 22% calories from fat, 23% calories from protein, 55% calories from carbohydrates) was from Lab Diet (5058) and HFD (5.6 kcal/g, 58% kcal from fat, 16% calories from protein, 26% calories from carbohydrate) was from Research Diets (D-12331), Male C57BL/6 mice were treated with Chow and HFD for 11 months. Male mixed strain background mice were divided into two cohorts at 4 weeks of age. One cohort was fed with Chow and other with HFD, as described previously (McNay et al, 2012). Mice were sacrificed and their brains were harvested after 1, 4, and 8 weeks on the respective diets.

i.c.v. injection of AICAR

Male mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane before i.c.v. injection of AICAR (6 μg) in 2 μl of ACSF (Artificial CerebroSpinal Fluid), the control cohort was injected with the vehicle (ACSF). i.c.v. injections were delivered into the third ventricle with a calibrated 10 μl Hamilton syringe 1 h before the start of the dark cycle. Two hours and six hours after i.c.v. injection, hypothalami were harvested (Kim et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005).

Measurement of food intake after i.c.v. injection

Cannulae were stereotaxically implanted into the third cerebral ventricle. After 7 days of recovery and acclimatization to single housing, mice were challenged by MC3R/MC4R agonist and antagonist. Mice eating ad libitum were administrated i.c.v. with 1 μl of ACSF (basal condition), 1 nmol of SHU9119 (Calbiochem) or 0.1 nmol of MT-II (Calbiochem) at 1300, h (compounds were delivered in 1 μl of ACSF). Cumulative food intake (Bio-Serv, precision dustless food pellet, #F0163) was measured for 6 h after i.c.v. injection. In all, 5 μg of PYY in 1 μl of ACSF (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) was administrated i.c.v. and cumulative food intake was measured for 3.5 h after i.c.v. injection.

Body composition analysis

Body composition was measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) using an EchoMRI (Echo Medical Systems).

Immunostaining

Mice were anaesthetized and perfused through the left ventricle with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS or 10% formalin. Brains were post-fixed at 4°C for 2 h to overnight and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose for 48 h or longer. Antibodies and detailed protocols used in this study are listed in Supplementary data.

Western blotting

Freshly dissected hypothalamus was homogenized in RIPA buffer to obtain total protein extract, which was separated on SDS–PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-E2F1 antibody (C20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and tubulin. Mouse embryo fibroblasts were isolated from E13.5 embryos and used at p5.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Mice were anaesthetized and perfused with 1 × PBS for 5 min, followed by another 5 min with 4% PFA. Dissected brain was post-fixed in 4% PFA for 12 h (O/N) in 4°C and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose for 48 h. Tissues were embedded in OCT gel (Tissue Tek), 20 μm thick coronal sections were collected on Superfrost Plus slides.

Hybridization steps were modified as previous described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008; Draper et al, 2010; Padilla et al, 2010). Briefly, sections were permeabilized for 30 min at 37°C with TE buffer containing either 1 μg/ml Proteinase K and post-fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at 4°C. Antisense digoxigenin-labelled riboprobes were generated from plasmids containing PCR fragments of Cyclin A2 using the following primers set: 5′-GACGTCGACGAATGTCAA CCCCGAAAA-3′/5′- GCTGAATTCCTTCTGCTTCATCCACAT-3. Brain sections were hybridized with Cyclin A2 riboprobes (15 ng/μl) at 55°C for 20 h, followed by stringent wash with 2 × SSC and 0.2 × SSC at 55°C for 30 min each. After that, HRP was introduced by Anti-Digoxigenin-POD (Roche 11207733910). Signal amplification steps were carried out based on the TSA Plus Cy3 System manual (Perkin-Elmer).

Quantification of POMC neurons number and cell size determination

POMC-stained cells were counted in about three ARC sections per mouse and an average of POMC neuron number was determined for each mouse. Brain slices were chosen at equivalent anatomical position in the ARC. Measurement of the soma area of the POMC neurons was performed with the Image J software with 300–350 POMC-stained neurons for each genotypes.

Projection density quantification

Projection density in the DMH and the PVH was measured according to Bouret et al (2008). For each animal, two sections through the PVH or DMH were acquired. Image analysis was performed using Image J software. Each image was binarized and the integrated intensity was then calculated for each image.

Hypothalamic neuropeptide assays and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

Peptides were extracted from hypothalamus in 0.1N HCl for measuring β-Endorphin and α-MSH by radioimmunoassay (Wardlaw, 1986). POMC precursor was measured by ELISA with reagents provided by Anne White at the University of Manchester (Tsigos et al, 1993).

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as average with s.e.m. Paired and unpaired Student’s t-tests were performed as indicated in figure legends. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 and significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T Jacks for providing Rb1lox/lox mice, B Lowell for Pomc-Cre and Agrp-Cre mice, Keiko Nakayama and Keiich Nakayama for Skp2 knockout mice, Jim Roberts for p27T187A knockin mice, Lili Yamasaki for E2f1 knockout mice, and F Costantini for Rosa26YFP mice. We are grateful to Dr Joe Locker for consultation on mouse pathology throughout this study. This work was supported by a Pilot and Feasibility Study grant from the Albert Einstein Diabetes Research and Training Center to LZ, RO1CA127901 (LZ), RO1CA87566 (LZ), RO1DK057621 (SC), PO1DK26687 (SC), Skirball Foundation (SC), DK080003 (SW); Albert Einstein Diabetes Research and Training Center (PO1DK052956), Liver Research Center (5P30DK061153), and Comprehensive Cancer Research Center (5P30CA13330) provided core facility support. LZ was a recipient of the Irma T Hirschl Career Scientist Award.

Author contributions: HW and LZ conceived the research; ZL, GM, HW, SC, and LZ designed the research; ZL, GM, FB, HW, HF, SLD, HZ, XL, YHJ, and SW performed the research; ZL, GM, YHJ, ND, SC, and LZ analysed the data; ZL, GM, and LZ wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson KA, Ribar TJ, Lin F, Noeldner PK, Green MF, Muehlbauer MJ, Witters LA, Kemp BE, Means AR (2008) Hypothalamic CaMKK2 contributes to the regulation of energy balance. Cell Metab 7: 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson U, Filipsson K, Abbott CR, Woods A, Smith K, Bloom SR, Carling D, Small CJ (2004) AMP-activated protein kinase plays a role in the control of food intake. J Biol Chem 279: 12005–12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB (2004) Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42: 983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsche E, Desroches J, Bilodeau S, Gauthier Y, Drouin J (2005a) Rb enhances p160/SRC coactivator-dependent activity of nuclear receptors and hormone responsiveness. J Biol Chem 280: 19746–19756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsche E, Moschopoulos P, Desroches J, Bilodeau S, Drouin J (2005b) Retinoblastoma and the related pocket protein p107 act as coactivators of NeuroD1 to enhance gene transcription. J Biol Chem 280: 16088–16095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz UA, Vosshenrich CA, Rajewsky K, Muller W (1996) Bypass of lethality with mosaic mice generated by Cre-loxP-mediated recombination. Curr Biol 6: 1307–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouret SG, Gorski JN, Patterson CM, Chen S, Levin BE, Simerly RB (2008) Hypothalamic neural projections are permanently disrupted in diet-induced obese rats. Cell Metab 7: 179–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B, Milbrandt J (2009) AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates retinoblastoma protein to control mammalian brain development. Dev Cell 16: 256–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick FA, Dyson N (2003) pRB contains an E2F1-specific binding domain that allows E2F1-induced apoptosis to be regulated separately from other E2F activities. Mol Cell 12: 639–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper S, Kirigiti M, Glavas M, Grayson B, Chong CN, Jiang B, Smith MS, Zeltser LM, Grove KL (2010) Differential gene expression between neuropeptide Y expressing neurons of the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus and the arcuate nucleus: microarray analysis study. Brain Res 1350: 139–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajas L, Landsberg RL, Huss-Garcia Y, Sardet C, Lees JA, Auwerx J (2002) E2Fs regulate adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell 3: 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MM (2002) Peptide YY: a key mediator of orexigenic behavior. Peptides 23: 377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrom TC, Mori S, Nevins JR (2008) An E2F1-dependent gene expression program that determines the balance between proliferation and cell death. Cancer Cell 13: 11–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrom TC, Nevins JR (2003) Specificity in the activation and control of transcription factor E2F-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10848–10853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Dai Y, Prentki M, Chohnan S, Lane MD (2005) A role for hypothalamic malonyl-CoA in the control of food intake. J Biol Chem 280: 39681–39683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EK, Miller I, Aja S, Landree LE, Pinn M, McFadden J, Kuhajda FP, Moran TH, Ronnett GV (2004) C75, a fatty acid synthase inhibitor, reduces food intake via hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 279: 19970–19976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Goodman J, Anderson KV, Niswander L (2007) Phactr4 regulates neural tube and optic fissure closure by controlling PP1-, Rb-, and E2F1-regulated cell-cycle progression. Dev Cell 13: 87–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoeva MV, Yin H, Flier JS (2005) Neurogenesis in the hypothalamus of adult mice: potential role in energy balance. Science 310: 679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DA, Bedont JL, Pak T, Wang H, Song J, Miranda-Angulo A, Takiar V, Charubhumi V, Balordi F, Takebayashi H, Aja S, Ford E, Fishell G, Blackshaw S (2012) Tanycytes of the hypothalamic median eminence form a diet-responsive neurogenic niche. Nat Neurosci 15: 700–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tang Y, Cai D (2012) IKKbeta/NF-kappaB disrupts adult hypothalamic neural stem cells to mediate a neurodegenerative mechanism of dietary obesity and pre-diabetes. Nat Cell Biol 14: 999–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek NP, Sundberg H, McGrew S, Nakayama K, Kyriakidis TR, Roberts JM (2001) A mouse knock-in model exposes sequential proteolytic pathways that regulate p27Kip1 in G1 and S phase. Nature 413: 323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TL, Alquier T, Asakura K, Furukawa N, Preitner F, Kahn BB (2006) Diet-induced obesity alters AMP kinase activity in hypothalamus and skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 281: 18933–18941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNay DE, Briancon N, Kokoeva MV, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS (2012) Remodeling of the arcuate nucleus energy-balance circuit is inhibited in obese mice. J Clin Invest 122: 142–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue B, Mu J, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Birnbaum MJ, Stuck BJ, Kahn BB (2004) AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature 428: 569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes JC, Coope A, Morari J, Cintra DE, Roman EA, Pauli JR, Romanatto T, Carvalheira JB, Oliveira AL, Saad MJ, Velloso LA (2009) High-fat diet induces apoptosis of hypothalamic neurons. PLoS ONE 4: e5045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzberg H, Flier JS, Bjorbaek C (2004) Region-specific leptin resistance within the hypothalamus of diet-induced obese mice. Endocrinology 145: 4880–4889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzberg H, Myers MG Jr (2005) Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat Neurosci 8: 566–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Nagahama H, Minamishima YA, Matsumoto M, Nakamichi I, Kitagawa K, Shirane M, Tsunematsu R, Tsukiyama TI, Shida N, Kitagawa M, Nakayama K, Hatakeyama S (2000) Targeted disruption of Skp2 results in accumulation of cyclin E and p27(Kip1), polyploidy and centrosome overduplication. EMBO J 19: 2069–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla SL, Carmody JS, Zeltser LM (2010) Pomc-expressing progenitors give rise to antagonistic neuronal populations in hypothalamic feeding circuits. Nat Med 16: 403–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin SM, Gall AL, Zheng N, Pavletich NP (2005) Structure of the Rb C-terminal domain bound to E2F1-DP1: a mechanism for phosphorylation-induced E2F release. Cell 123: 1093–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage J, Miller AL, Perez-Mancera PA, Wysocki JM, Jacks T (2003) Acute mutation of retinoblastoma gene function is sufficient for cell cycle re-entry. Nature 424: 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404: 661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ (1996) Cancer cell cycles. Science 274: 1672–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F (2001) Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 1: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg GR, Watt MJ, Fam BC, Proietto J, Andrikopoulos S, Allen AM, Febbraio MA, Kemp BE (2006) Ciliary neurotrophic factor suppresses hypothalamic AMP-kinase signaling in leptin-resistant obese mice. Endocrinology 147: 3906–3914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, Nguyen HT, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Wisse BE, Morton GJ, Horvath TL, Baskin DG, Tschop MH, Schwartz MW (2012) Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 122: 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B (2008) High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc 3: 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Q, Ye CP, Jones JE, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB (2008) Synaptic release of GABA by AgRP neurons is required for normal regulation of energy balance. Nat Neurosci 11: 998–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Lees JA (2002) Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Crosby SR, Gibson S, Young RJ, White A (1993) Proopiomelanocortin is the predominant adrenocorticotropin-related peptide in human cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76: 620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Bauzon F, Ji P, Xu X, Sun D, Locker J, Sellers RS, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Cobrinik D, Zhu L (2010) Skp2 is required for survival of aberrantly proliferating Rb1-deficient cells and for tumorigenesis in Rb1+/− mice. Nat Genet 42: 83–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw SL (1986) Regulation of beta-endorphin, corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide, and alpha-melanotropin-stimulating hormone in the hypothalamus by testosterone. Endocrinology 119: 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA (1992) The retinoblastoma gene and gene product. InTumour Suppressor Genes, the Cell Cycle and Cancer Levine AJ (ed)Vol. 12: pp43–57New York, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki L, Bronson R, Williams BO, Dyson NJ, Harlow E, Jacks T (1998) Loss of E2F-1 reduces tumorigenesis and extends the lifespan of Rb1(+/−)mice. Nat Genet 18: 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.