Abstract

Up to half of all postmenopausal women will experience changes in the genitourinary tract induced by the hypoestrogenic state, collectively known as vaginal atrophy. Vaginally administered local estrogen therapy (LET) is the standard of care for symptoms of vaginal atrophy that do not respond to nonhormonal interventions. Several LET formulations are available, and choice of therapy is based largely on patient needs and preferences. This online survey of postmenopausal LET users was conducted to investigate reasons for switching to vaginal estradiol tablets from other formulations and to evaluate factors associated with patient preference for and compliance with use of LET. Data was analyzed from 73 respondents currently using estradiol vaginal tablets who have previously used the estradiol vaginal ring, estradiol vaginal cream, and/or conjugated estrogen vaginal cream. Patients in this survey rated vaginal symptoms of vaginal atrophy as being more bothersome than urinary symptoms. Respondents preferred their current treatment with the vaginal tablet to their previous treatment with a cream or ring. The preference for tablets over creams was mainly related to formulation and application rather than to any perceived safety issues. Tablets were perceived as efficacious, convenient, and neat to apply. The study participants also reported a longer duration of tablet use compared with creams or rings, and greater compliance with vaginal tablets than with vaginal cream. This study provides new insights into reasons for patient noncompliance with estrogen cream or ring therapy that can be used to maximize patient adherence with LET.

Keywords: vaginal atrophy, local estrogen therapy, estradiol, vaginal ring, vaginal tablet, vaginal cream, conjugated estrogen vaginal cream

Introduction

Vaginal atrophy is a consequence of the hypoestrogenic state and resulting anatomical and physiological changes in the genitourinary tract.1,2 Symptoms of vaginal atrophy include decreased vaginal moisture, increased vaginal pH, and increased risk of vaginal infections. Urinary symptoms such as problems of incontinence and recurrent urinary tract infection can also occur in women with vaginal atrophy, because the cells of the bladder epithelium are sensitive to decreased estrogen levels.1,2

The North American Menopause Society3 estimates that 10%–40% of menopausal women will experience one or more symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Vaginal dryness, increased nerve activity, and decreased genital blood flow contribute to dyspareunia and decreased physiological and subject-reported arousal.4 Although sexual desire decreases during menopause,5 measures of sexual dysfunction are present at higher rates in women with vaginal atrophy than in unaffected menopausal women.6 In one study, 30% of women experiencing dyspareunia reported that it was severe enough to cause disruption or termination of sexual activity.7 Together these symptoms have a detrimental effect on women’s quality of life, including their intimate relationships and their feelings of self-esteem.8

Vaginally administered local estrogen therapy (LET) is the prescription therapy recommended by the North American Menopause Society and the International Menopause Society for the treatment of symptoms of vaginal atrophy that do not respond to nonhormonal interventions.3,9–12 Systemic administration (eg, oral, transdermal) of estrogen therapy is an effective treatment for a variety of postmenopausal symptoms, but it may be contraindicated in or unacceptable to some women because of its potential for systemic adverse effects, especially with chronic use.9,10 The LETs approved in the United States for the treatment of vaginal atrophy are a conjugated estrogen cream, an estradiol cream, an estradiol ring, and an estradiol vaginal tablet. Because each of these treatments has been shown to be safe and effective, the specific therapy selected is based largely on patient needs and preferences.3 This article describes data from a survey of LET users conducted to investigate reasons for switching to vaginal estradiol tablets from other formulations and to evaluate factors associated with patient preference for and compliance with the use of LET.

Materials and methods

Eligible participants were US residents aged 18 years and older who were postmenopausal (ie, women who had not presented with a spontaneous menstrual period for more than 1 year) or who had received bilateral oophorectomy. Participants were currently receiving LET in the form of estradiol vaginal tablets (Vagifem®, 10 μg, Novo Nordisk Inc, Princeton, NJ, USA). These women were required to have had prior experience using other formulations of LET: the estradiol vaginal ring (Estring®, reservoir of 2 mg estradiol, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals [a division of Pfizer], Philadelphia, PA, USA); estradiol vaginal cream (Estrace®, estradiol cream, 0.1 mg estradiol/g USP, Contract Pharmaceuticals Limited, Buffalo, NY, USA for Warner Chilcott, LLC); and/or conjugated estrogen vaginal cream (Premarin®, 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens/g USP, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals). Women who reported current concomitant treatment with a vaginal cream and a vaginal tablet were excluded from participation, as were those currently employed as a health care provider (physician, nurse, pharmacist, or physician’s assistant) or those who had a household member currently employed as a health care provider.

A segment of 6974 women who had self-identified as estradiol vaginal tablet users in an online Web-based patient portal (managed by gcConnect) were contacted via personal email with a request to participate in the study. Approximately 10–15 minutes were required to complete the online questionnaire. The methodology was tested for soundness prior to initiation of data collection, for example, for logical sequencing, unbiased ordering, appropriate forced-choice responses, predetermined eligibility requirements, properly programmed skip patterns based on responses previously given in the questionnaire, and responses required for all questions.

The null hypothesis of statistical independence of symptom frequencies between the age groups (young versus old) was tested at a significance level of 0.05 using the likelihood-ratio Chi-Square statistic and its asymptotic distributions, based on SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Data were collected over a 5-week period, from March 6, 2012, through April 9, 2012. The data were tabulated and subjected to testing of statistical significance at the 95% level of confidence.

Results

A total of 423 women accessed the study; of these, 344 failed to meet the inclusion criteria (69 were employed either as a health care provider or had a household member who was a health care provider, 24 did not meet the definition of menopausal, 92 were not using vaginal tablet therapy at the time of data collection, and 159 had not been previously treated with a vaginal cream or vaginal ring). The remaining 79 participants met all inclusion criteria and completed the questionnaire. These women were mainly white, approximately half were younger than 58 years, and 66% were sexually active (Table 1). Most (85%) had used a vaginal cream rather than the vaginal ring (9%), while 6% of patients had used both the cream and the ring (Table 1) before switching to the vaginal tablet.

Table 1.

Demographic information for survey respondents

| Patient characteristics, n (%) | n = 79 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 35–57 | 41 (52) |

| ≥58 | 38 (48) |

| Ethnic background | |

| White | 72 (91) |

| Black | 3 (4) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) |

| Asian | 0 |

| Declined to answer | 3 (4) |

| Sexual status | |

| Active | 52 (66) |

| Inactive | 18 (23) |

| Declined to answer | 9 (11) |

| Current regimen | |

| Vaginal tablets | 61 (77) |

| Vaginal tablets and OTC lubricant or moisturizer | 18 (23) |

| Prior regimen | |

| Cream user | 67 (85) |

| Ring user | 7 (9) |

| Cream and ring user | 5 (6) |

Abbreviation: OTC, over the counter.

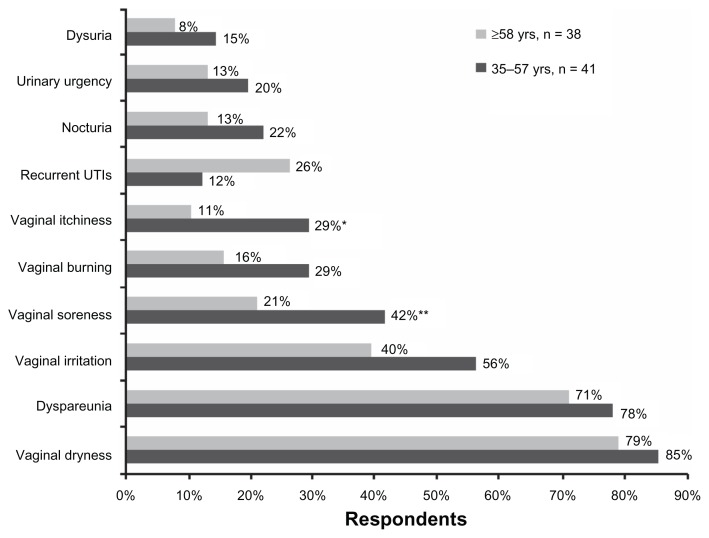

Respondents were asked to choose the symptoms of vaginal atrophy that they found most bothersome from a list that included both urinary and vaginal symptoms (Figure 1). A greater percentage of these women were bothered by vaginal symptoms than were bothered by urinary symptoms. The symptoms cited as bothersome by most women were vaginal dryness (82% of all respondents) and dyspareunia (75% of all respondents), and these were chosen by an equal proportion of younger (aged 35–57 years) and older (aged ≥58 years) women. For most symptoms, a greater percentage of younger women were bothered compared with older women; the difference between older (21% and 11%) and younger (42% and 29%) women bothered by their symptoms reached statistical significance for soreness (P = 0.0492) and itchiness (P = 0.0345), respectively (Figure 1). Conversely, a higher percentage of older women than younger women found recurrent urinary tract infections to be bothersome, although the difference between age groups did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Symptoms of vaginal atrophy considered bothersome by patients, according to age group.

Notes: *Vaginal itchiness: older versus younger (P = 0.0345). **Vaginal soreness: older versus younger (P = 0.0492).

Abbreviation: UTIs, urinary tract infections.

At the time of the survey, respondents had been receiving vaginal tablets as therapy for a mean ± standard deviation of 20.7 ± 15.0 months. They had previously used vaginal cream for a mean of 17.0 ± 14.9 months and the ring for 11.6 ± 10.0 months before switching to the vaginal tablet. In addition to having used these therapies for a shorter amount of time, approximately 20% of women who had used vaginal creams and 100% who had used the vaginal ring reported having delayed filling their prescriptions at some point during treatment.

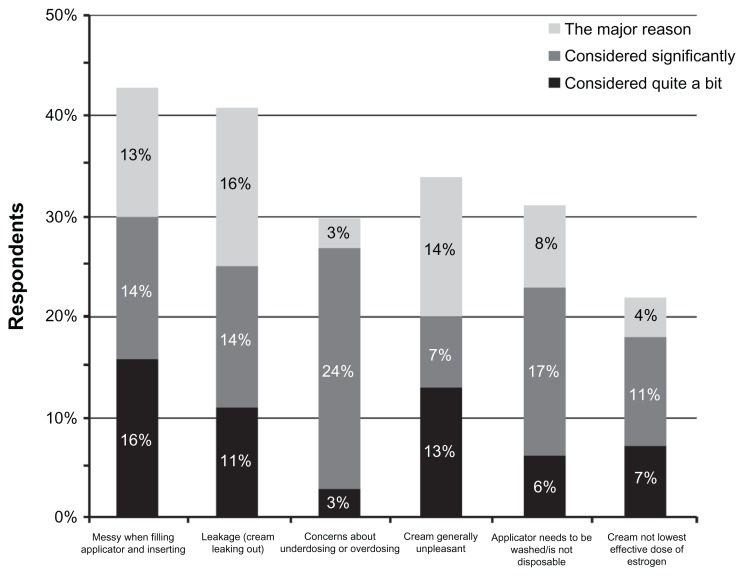

Many of the women who had been treated with vaginal cream (n = 71) also reported missing doses at least once a month, and this avoidance was often because of attributes of the cream formulation. These attributes included messiness when filling and inserting the applicator (61% of vaginal cream users), general unpleasantness of the cream (53%), the need to wash the applicator (48%), and leakage of cream following application (37%). The percentage of total respondents who reported missing a dose at least once a week for these reasons was 37% for messiness, 25% for filling and inserting applicator, 30% for general unpleasantness, and 23% for leakage. These factors were also the most common reasons for switching from vaginal creams to the vaginal tablet (Figure 2). Safety-related perceptions were not often cited as the major reason for switching from cream to tablet; however, among women who switched from creams, concerns about underdosing or overdosing (24%) and concern that creams were not the lowest effective estrogen dose (11%) were “significant considerations” (Figure 2). Among previous ring users (n = 8), the reasons for having delayed filling a prescription were difficulty removing the ring (n = 4), the patient or their partner could feel the ring (n = 2 each), concern about vaginal infections (n = 2), concern about hygiene and cleanliness (n = 1), difficulty inserting the ring (n = 1), and concern that the ring was not the lowest effective dose of estrogen that could be prescribed (n = 1).

Figure 2.

Reasons for switching from vaginal cream to vaginal tablet.

For the majority of respondents (52%), the switch to vaginal tablets was recommended by health care providers. Other triggers were general requests by the patients to change treatments (18%), patient-specific requests for the vaginal tablet (15%), and pharmacist recommendation of the tablet (3%). Regarding compliance, 66% said they would be “much more likely” to use their current tablet treatment compared with the cream that they previously used, 10% were “somewhat more likely” to use the tablet, and 21% were “just as likely” to use either agent. One percent of patients were “somewhat less likely” and 1% were “much less likely” to use the tablet than the cream.

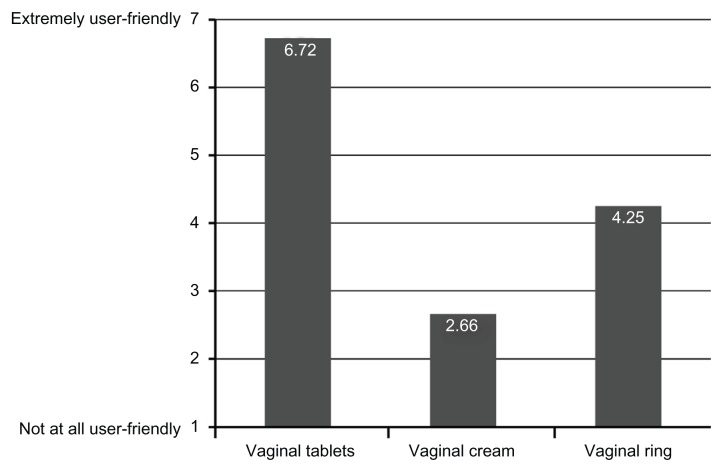

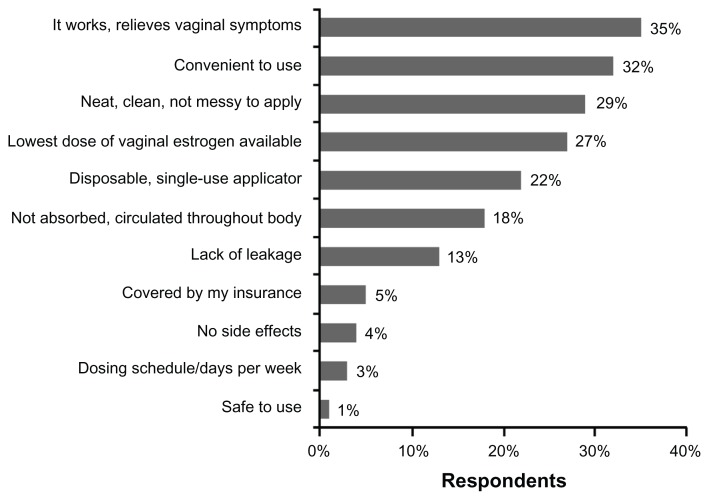

Patients were asked to rate how user-friendly these therapies were on a seven-point Likert scale where 1 indicated “not at all user-friendly” and 7 indicated “extremely user-friendly” (Figure 3). Mean scores were 6.72 ± 0.87 for the tablet (n = 75 users), 2.66 ± 1.48 for the cream (n = 71 users), and 4.25 ± 2.38 for the ring (n = 8 users). Patient-selected positive attributes of the vaginal tablet are shown in Figure 4. These positive attributes included effectiveness in relieving symptoms (35%); convenience of use (32%); neat, clean, and not messy to apply (29%); and lowest dose of estrogen available (27%).

Figure 3.

User-friendliness ratings of the different local estrogen therapy formulations.

Figure 4.

Positive attributes of vaginal estradiol tablets.

Respondents were also asked if they were aware that regulatory agencies and medical societies have recommended using the lowest effective dose of estrogen to alleviate symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Of the total survey respondents, 44% said they were “very much aware” of these recommendations, 24% were “somewhat aware,” 11% were “vaguely aware,” and 21% were “not at all aware.”

Discussion

Patients in this survey rated the vaginal symptoms of vaginal atrophy as being more bothersome than the urinary symptoms. Similar to these data, an online survey of US women over the age of 45 years showed that 66% of hormone therapy users considered dryness and dyspareunia to be detrimental to their quality of life.13 Few surveys have examined attitudes toward vaginal and urinary symptoms in the same patient population. In the VIVA (Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes) survey, a similar percentage of patients were “concerned” about vaginal dryness (36%), dyspareunia (24%), and involuntary urination (35%).14

For all symptoms of vaginal atrophy except urinary tract infection, a larger percentage of younger women rated their symptoms as bothersome. This difference between age groups was significant in regard to itchiness and soreness. The lack of disparity between age groups for dyspareunia and dryness might be surprising, given the known decrease in sexual activity with increasing age; however, other surveys have found that the absence of sexual activity does not seem to decrease the perceived impact of vaginal symptoms.13

Patient preference can play a major role in health care provider treatment algorithms for vaginal atrophy and lead to better adherence, and thus greatly increase the chance of successful treatment. The group of women who had been treated with both the vaginal estradiol cream or the vaginal ring and vaginal tablets for their symptoms of vaginal atrophy preferred a vaginal tablet to the cream or ring. Tablets were perceived as efficacious, convenient, and neat to apply; these positive attributes may have contributed to the greater duration of tablet use compared with creams or rings. In addition, respondents also reported greater compliance with vaginal tablets than with vaginal cream. These results are similar to those in a previous study investigating the real-world clinical use of LETs which found that adherence with and duration of therapy were higher for vaginal tablets than for vaginal creams.15

The majority of women surveyed (52%) switched therapies at the suggestion of their health care provider. This is in keeping with surveys of menopausal women in which women most commonly learned about vaginal atrophy from their health care providers, including gynecologists and general practitioners.8,16 These data further suggest that health care providers play an important role in maximizing adherence with therapy by asking patients what they do and do not like about their LET and suggesting alternatives as appropriate.

In a 24-week study of 159 postmenopausal women, fewer patients using a vaginal tablet experienced endometrial proliferation or hyperplasia than those using a conjugated estrogen vaginal cream, perhaps due to lower circulating estradiol levels with the tablet relative to the cream.17 However, a Cochrane review of LETs has suggested that there are no discernible safety differences among the available options for LET.12 The preference for vaginal tablets over creams was mainly related to formulation and application rather than safety issues. Interestingly, although more than 68% of women claimed to be “very much” or “somewhat” aware of recommendations for the lowest effective dose of estrogen to be used, only 22% of patients considered this factor “quite a bit,” “significantly,” or as “the major reason” for switching from the cream to a tablet, compared with 43% of patients who were concerned by the messiness of the cream.

This study was designed to evaluate why women would switch from the cream and ring formulations of estrogen to the vaginal tablet approach for the treatment of vaginal atrophy, a common chronic condition suffered by many postmenopausal women. All of the available LET formulations are comparable in efficacy, so the choice of treatment depends on clinical experience and patient preference.3

Findings from this study underscore the importance of a patient-friendly local estrogen formulation for the treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy, because product attributes influence women’s choices of treatment and should assist health care professionals in optimization of treatment. Other interesting findings from this study included bladder issues also being important to the younger population (as we expected for the older women), and that in general, postmenopausal women were aware of the recommended use of the lowest dose of estrogen which also seemed to be a strong motivator for the use of and adherence to vaginal tablets.

One of the major weaknesses of this study is that women who completed the survey were currently using vaginal tablets, so the total duration of use of the vaginal tablets cannot be determined. In addition to collecting only self-reported data, this study preselected only women switching from cream or ring to tablets, so patients who switched from tablets to other LET therapies were not included. Therefore, the study design was selected for patients who were dissatisfied with previous therapies and might be predisposed to liking vaginal tablets. Nonetheless, this study provides new insights into reasons for patient noncompliance with estrogen cream and ring therapy, and reports the opinions of patients regarding the advantages and disadvantages of different LET formulations. Data such as these can contribute to development of methods to improve patient adherence throughout treatment.

Acknowledgment

Editorial assistance was provided by Amy Troy, Ethos Health Communications, Newtown, PA, USA, with financial assistance from Novo Nordisk Inc, Princeton, NJ, USA, in compliance with international guidelines on Good Publication Practice.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors received no remuneration of any kind for the development of this manuscript.

References

- 1.MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87–94. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS. Diagnosis and treatment of atrophic vaginitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(10):3090–3096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 1):355–369. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31805170eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lara LA, Useche B, Ferriani RA, et al. The effects of hypoestrogenism on the vaginal wall: interference with the normal sexual response. J Sex Med. 2009;6(1):30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(3):442–452. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine KB, Williams RE, Hartmann KE. Vulvovaginal atrophy is strongly associated with female sexual dysfunction among sexually active postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008;15(4 Pt 1):661–666. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31815a5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyeth. REVEAL Revealing Vaginal Effects At Mid-Life: Surveys of postmenopausal women and health care professionals who treat postmenopausal women. [Accessed April 6, 2012]. Available from: http://www.revealsurvey.com/pdf/reveal-survey-results.pdf.

- 8.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14(3):357–369. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31805170eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13(6):509–522. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.522875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kingsberg S, Kellogg S, Krychman M. Treating dyspareunia caused by vaginal atrophy: a review of treatment options using vaginal estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2010;1:105–111. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.647840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shulman LP, Portman DJ, Lee WC, et al. A retrospective managed care claims data analysis of medication adherence to vaginal estrogen therapy: implications for clinical practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(4):569–578. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA) - results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.647840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rioux JE, Devlin C, Gelfand MM, Steinberg WM, Hepburn DS. 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablet versus conjugated equine estrogen vaginal cream to relieve menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Menopause. 2000;7(3):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]