Abstract

Purpose

Women with early-onset (age ≤40) breast cancer are at high risk of carrying deleterious mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes; genetic assessment is thus recommended. Knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation status is useful in guiding treatment decisions. To date, there has been no national study of BRCA1/2 testing among newly diagnosed women.

Methods

We used administrative data (2004–2007) from a national sample of 14.4 million commercially-insured patients to identify newly-diagnosed, early-onset breast cancer cases among women ages 20–40 (n=1,474). Cox models assessed BRCA1/2 testing, adjusting for covariates and differential lengths of follow-up.

Results

Overall, 30% of women age ≤40 received BRCA1/2 testing. In adjusted analyses, women of Jewish ethnicity were significantly more likely to be tested (HR=2.83, 95% CI 1.52–5.28), while black women (HR=0.34, 95% 0.18–0.64) and Hispanic women (HR=0.52, 95% CI 0.33–0.81) were significantly less likely to be tested than non-Jewish white women. Those enrolled in an HMO (HR=0.73, 95% CI 0.54–0.99) were significantly less likely to receive BRCA1/2 testing than those POS insurance plans. Testing rates rose sharply for women diagnosed in 2007 compared to 2004.

Conclusions

In this national sample of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients at high risk for BRCA1/2 mutations, genetic assessment was low, with marked racial differences in testing.

Keywords: breast cancer, BRCA1/2, race, ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

Little is known about the diffusion and appropriate use of established genetic tests in the U.S. healthcare system. Cancer genetics is one of the most developed areas of clinical genetics. Testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutations to assess risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) is among the most established genetic tests in clinical use.1–3 Guidelines and commercial testing for BRCA1/2 mutations have been available for more than a decade,4 and most health insurers now reimburse at least partially for these tests in individuals at high risk for mutations.5 National guidelines recommend that women diagnosed with early onset breast cancer receive BRCA1/2 testing in order to guide treatment decisions.6 Among patients newly-diagnosed with cancer, a positive test result will often prompt more aggressive surgical treatment (e.g., bilateral salpingo oopherectomy or prophylactic contralateral mastectomy) with the goal of minimizing the potential for second primary cancers.3, 7–8 A positive test result may also prompt consideration of BRCA1/2 testing among at-risk relatives of the cancer patient so that those testing positive can benefit from more aggressive prevention and screening.3

Despite advances in testing criteria and knowledge about treatment strategies for mutation carriers, studies suggest that few women at high risk of hereditary breast cancer are offered genetic testing.9 High risk black women are less likely to be counseled or tested than high risk white women,10–11 mirroring racial disparities found in other aspects of cancer care and outcomes.12–13 Among newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients, studies have examined the use of BRCA1/2 testing only in the context of site-specific patient populations.11, 14 We are aware of no national study that assesses BRCA1/2 testing among early onset breast cancer patients, and the extent to which patterns of testing reflect national guidelines. The present study addresses this important gap in the literature.

Specifically, we evaluated the use of testing for BRCA1/2 mutations in a large, national sample of newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients ages 20–40 using medical claims and demographic data from a large commercially-insured population representing more than 14.4 million covered lives in the U.S. We focused on women with early-onset breast cancer because this subpopulation is indicated for BRCA1/2 testing according to National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) guidelines, and we can reliably indentify this subset of women in claims data. We assessed rates of BRCA1/2 testing in this group, determined whether minority and low-income women were less likely to receive testing, and tracked the diffusion of testing over the 2004–2007 period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and Case Definition

We analyzed medical claims and administrative information from a database of privately insured individuals residing in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The database, covering January 2004 to May 2007, included approximately 14.4 million members annually. To identify incident breast cancer patients, we first selected patients with a primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code of female breast cancer (174.x) or ductal carcinoma in situ (233.0) during the study period. New cancer cases were defined as those with a primary diagnosis of breast cancer attached to surgical removal of the cancer. Removal was identified using Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition (CPT4) codes and ICD-9-CM procedure codes (see Appendix). Second, absent a surgery claim, a biopsy claim was considered evidence of a new breast cancer case if it was followed within 6 months by ≥4 dates of service with radiation or chemotherapy treatments assigned a breast cancer primary diagnosis. Third, lumpectomy or mastectomy without an accompanying primary diagnosis code of breast cancer was assumed to be evidence of incident breast cancer if was followed within 6 months by ≥4 dates of service with radiation or chemotherapy treatments assigned a primary diagnosis code of breast cancer. Our analysis was further restricted to patients ages 20 to 40. We required that patients have a minimum three-month continuous enrollment immediately prior to their initial treatment for cancer in order to confirm that we were capturing the initial diagnosis date. Those with claims containing codes for a personal history of breast cancer prior to the first observed date of treatment were also excluded from our sample of incident cases. While the stringent criteria used to identify incident cases may have excluded some new breast cancer cases, we intentionally used a conservative approach since our goal was to assess adherence to national guidelines.

Our dependent variable was having a paid claim for BRCA1/2 testing. Tests for mutations in these genes were identified using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes specific to those tests. HCPCS codes are preferred by Myriad Genetics, the vendor that currently performs nearly all testing for BRCA1/2 mutations.

Independent variables in our analyses included patient demographic data (age, race/ethnicity, household income); insurance product (health maintenance organization/HMO, preferred provider organization/PPO, point of service/POS, exclusive provider organization/EPO; contextual data (average educational attainment at the Census block level, Census region, year of diagnosis); and clinical characteristics (type of treatment received, additional cancer diagnoses, family history of breast or ovarian cancer). Table 2 contains the specific categories included for each of these variables. Race/ethnicity was assigned based on imputation by a commercial firm under contract to the insurer using name recognition algorithms (incorporating first, middle, and last names) and Census data specific to individuals’ geographic locations.15 The imputation method used has been shown in previous studies to have moderate sensitivity (48%), excellent specificity (97%), and moderate positive predictive value (71%) for the purpose of identifying black cancer patients in particular.16 The characteristics of imputed Jewish ethnicity have not been assessed, but the imputation does identify 2% of the study sample as having Jewish ancestry, which is similar to national estimates.17 We also test whether our results are sensitive to reclassifying all those identified as Jewish to non-Jewish white. Individuals for whom the algorithm was unable to impute an ethnicity and individuals for whom ethnicity was not imputed (e.g., because they were added to the dataset after the imputation had been performed) were combined into the “other/unknown” category. Household income was also imputed and validated by a commercial vendor18 under contract to the insurer, based on income for a nationally-representative sample of 150,000 households, consumer survey data, and ZIP code-level data from the Internal Revenue Service. Education level associated with patients’ Census block was coded as unknown when patients lacked data on Census block of residence. Clinical characteristics were determined based on diagnosis, procedure, and revenue codes (see Appendix). While family history is likely to be under-reported in claims data, it is likely to be accurate when reported. We included family history codes as a potential predictor of genetic testing only when the code occurred ≥30 days prior to a genetic test claim, thereby minimizing spurious correlations that may occur when family history coding is used to justify genetic testing.

Table 2.

Population characteristics and use of genetic tests.

| Characteristics | Population N (%) |

Had BRCA 1/2 Test N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1,474 (100) | 446 (30) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Jewish) | 808 (55) | 271 (34) |

| Black | 82 (6) | 10 (12) |

| Hispanic | 116 (8) | 21 (18) |

| Asian | 56 (4) | 15 (27) |

| Jewish | 32 (2) | 18 (56) |

| Other/Unknown | 380 (26) | 111 (29) |

| Household Income | ||

| $0–29,999 | 53 (4) | 11 (21) |

| $30,000–49,999 | 194 (13) | 48 (25) |

| $50,000–99,999 | 571 (39) | 173 (30) |

| $100,000–149,999 | 234 (16) | 94 (40) |

| ≥$150,000 | 38 (3) | 17 (45) |

| Unknown | 384 (26) | 103 (27) |

| Education | ||

| ≤ High School | 400 (27) | 97 (24) |

| ≥ College | 802 (54) | 272 (34) |

| Unknown | 272 (18) | 77 (28) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 199 (14) | 52 (26) |

| South | 644 (44) | 211 (33) |

| Midwest | 424 (29) | 111 (26) |

| West | 207 (14) | 72 (35) |

| Provider Type | ||

| Exclusive Provider Organization | 207 (14) | 73 (35) |

| Health Maintenance Organization | 250 (17) | 53 (21) |

| Point of Service | 851 (58) | 278 (33) |

| Preferred Provider Organization | 166 (11) | 42 (25) |

| Family History of Breast/Ovarian Cancer | ||

| No | 1,188 (81) | 362 (30) |

| Yes | 286 (19) | 84 (29) |

| Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis | ||

| No | 1,468 (99.6) | 445 (30) |

| Yes | 6 (.4) | 1 (17) |

| Breast Conserving Surgery | ||

| No | 521 (35) | 169 (32) |

| Yes | 953 (65) | 277 (29) |

| Unilateral Mastectomy | ||

| No | 1,049 (71) | 302 (29) |

| Yes | 425 (29) | 144 (34) |

| Bilateral Mastectomy | ||

| No | 1,425 (97) | 434 (30) |

| Yes | 49 (3) | 12 (24) |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 468 (32) | 96 (21) |

| Yes | 1,006 (68) | 350 (35) |

| Radiation | ||

| No | 746 (51) | 190 (25) |

| Yes | 728 (49) | 256 (35) |

| Trastuzumab Therapy | ||

| No | 1,350 (92) | 403 (30) |

| Yes | 124 (8) | 43 (10) |

| Hormone Therapy | ||

| No | 858 (58) | 218 (25) |

| Yes | 616 (42) | 228 (37) |

| Year | ||

| 2004 | 390 (26) | 108 (28) |

| 2005 | 450 (31) | 121 (27) |

| 2006 | 481 (33) | 172 (36) |

| 2007 | 153 (10) | 45 (29) |

The 2004 National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) guidelines for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment19 are representative of the knowledge base available to clinicians during our study period. These guidelines detail various criteria indicating high risk of hereditary cancer and thus appropriateness for genetic testing. For breast cancer patients, age ≤40, Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity, diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and family history of breast or ovarian cancer indicate high HBOC risk. Among these criteria, age is most reliably measured in administrative data. We therefore conducted our analysis including only newly-diagnosed “early onset” breast cancer patients (≤40), all of whom should be considered for genetic assessment according to the NCCN guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, assessing the time from first cancer diagnosis to receipt of a genetic test, to assess the likelihood of receiving genetic testing at any point in time following cancer diagnosis as a function of patient characteristics, while accounting for the different durations of follow-up observation that were possible depending on how long a patient’s treatment lasted or when she was first observed in the data. Time of initial breast cancer diagnosis was defined as the earliest primary diagnosis of breast cancer coded within three months prior to the first date of breast cancer treatment. The Cox models allowed us to assess trends in utilization over time and identify patient characteristics associated with testing. Earlier research found different effects of race on testing when testing occurs in the first year following diagnosis compared to when it occurs beyond that point.11 We estimated one model truncating follow-up at a maximum of one year and another in which follow-up was not restricted. The Cox models necessarily excluded a small number of patients (n=11) for whom we observed genetic testing prior to initial diagnosis.

Because the study used only de-identified data, it was deemed exempt from review by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

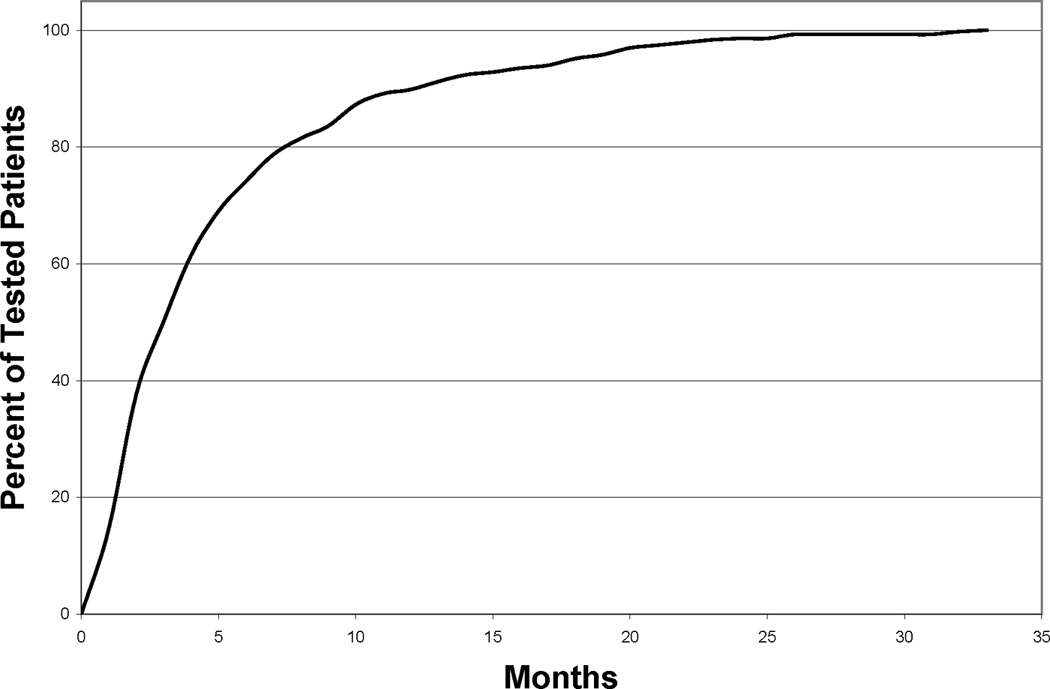

After applying stringent exclusion criteria, we identified a sample of 1,474 newly-diagnosed early-onset breast cancer cases (Table 1). Six percent of patients were black, 8% Hispanic, 4% Asian, 2% Jewish, 55% non-Jewish white, and 26% “other or unknown” race/ethnicity (Table 2). Seventeen percent had family incomes under $50,000 per year. Only 30% (n=446) of our study sample was tested for BRCA1/2 mutations. There was substantial variation in testing rates by patient characteristics absent adjustment for confounders or differential durations of observation. Fourteen percent of those tested underwent testing prior to their treatment. The median time from diagnosis to testing was 4 months and 91% were tested within one year of diagnosis (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Application of Exclusion Criteria to Identify New Cancer Patients

| Criterion | # remaining after application of criterion |

|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | |

| Applicable breast cancer diagnosis and surgical treatment | 41,548 |

| Females | 41,155 |

| Age 20–64 | 32,978 |

| ≥3 Months enrollment prior to 1st treatment date | 22,145 |

| No personal history code prior to 1st treatment date | 14,348 |

| No missing data for multivariate analysis | 14,235 |

| Age 20–40 | 1,474 |

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution of time from diagnosis to genetic testing for patients receiving testing

Our primary findings relate to the multivariate model with unrestricted follow-up (Table 3). Our model truncated at 1 year follow-up gave results that were nearly indistinguishable from the unrestricted model, so we only report the latter. We found a number of important predictors of BRCA1/2 testing among this cohort of newly diagnosed women. As one would expect, women of Jewish ethnicity, a key indicator of high risk for BRCA1/2 mutations, were nearly three times as likely to receive testing compared to non-Jewish white women (HR 2.83, 95% CI 1.52–5.28). Though a contemporaneous diagnosis of ovarian cancer would also warrant BRCA1/2 testing, there were very few such diagnoses in the study sample and we did not find a significant association between ovarian cancer diagnosis and BRCA1/2 testing.

Table 3.

| Characteristic d | HR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity (vs. White) | |

| Black | 0.34 (0.18–0.64) |

| Hispanic | 0.52 (0.33–0.81) |

| Asian | 0.65 (0.38–1.12) |

| Jewish | 2.83 (1.52–5.28) |

| Other/Unknown | 0.90 (0.65–1.23) |

| Household Income (vs. <$30K) | |

| $30,000–49,999 | 1.31 (0.67–2.56) |

| $50,000–99,999 | 1.41 (0.75–2.69) |

| $100,000–149,999 | 1.77 (0.90–3.48) |

| $150,000+ | 2.02 (0.91–4.49) |

| Unknown | 1.15 (0.59–2.22) |

| Education (vs.≤ High School) | |

| ≥ College | 1.18 (0.89–1.55) |

| Unknown | 1.56 (0.95–2.55) |

| Region (vs. Northeast) | |

| South | 1.46 (1.07–2.00) |

| Midwest | 1.03 (0.73–1.45) |

| West | 1.31 (0.91–1.89) |

| Provider Type (vs. Point of Service) | |

| Exclusive Provider Organization | 1.09 (0.84–1.42) |

| Health Maintenance Organization | 0.73 (0.54–0.99) |

| Preferred Provider Organization | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) |

| Family History of breast or ovarian cancer, Yes (vs. No) | 0.85 (0.66–1.08) |

| Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis Yes (vs. No) | 0.48 (0.07–3.59) |

| Breast Conserving Surgery, Yes (vs. No) | 1.07 (0.60–1.88) |

| Unilateral Mastectomy, Yes (vs. No) | 1.22 (0.69–2.17) |

| Bilateral Mastectomy, Yes (vs. No) | 1.00 (0.45–2.21) |

| Chemotherapy, Yes (vs. No) | 1.72 (1.36–2.18) |

| Radiation, Yes (vs. No) | 1.24 (1.01–1.52) |

| Trastuzumab, Yes (vs. No) | 0.88 (0.64–1.22) |

| Hormone Therapy, Yes (vs. No) | 1.29 (1.06–1.58) |

| Year (vs. 2004) | |

| 2005 | 0.99 (0.75–1.30) |

| 2006 | 2.04 (1.58–2.64) |

| 2007 | 3.79 (2.59–5.55) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Bolded text indicates significance (p<0.05).

Follw-up time for this model is not restricted

Reference categories are listed in parentheses.

Controlling for other risk factors and all other covariates, black and Hispanic women were significantly less likely to receive BRCA1/2 testing compared to non-Jewish white women (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.18–0.64; HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.33–0.81, respectively). There was a monotonically increasing likelihood of testing as a function of family income, though these associations were not statistically significant. However, when income was coded as an ordinal variable, a statistically significant association emerged, where women with family incomes >$150,000/year were 1.99 times as likely to be tested as women with incomes <$30,000/year (95% CI 1.10–28.51; results not shown).

Several other factors were also significantly associated with the probability of testing. Patients who received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or hormone therapy were more likely to receive testing than those not receiving those therapies (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.36–2.18; HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01–1.52; and HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.06–1.58 respectively). Women covered by an HMO insurance product were less likely to be tested than those with a POS product (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54–0.99). Those living in the South were more likely to be tested than patients in the Northeast (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.07–2.00). After adjusting for covariates, the likelihood of testing increased consistently and substantially over the study period, with women diagnosed in 2007 3.79 times as likely to be tested as those diagnosed in 2004 (95% CI 2.59–5.55).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis regarding the potential for bias in measuring differences between blacks or Hispanics and non-Jewish whites due to the misclassification of Jewish women as non-Jewish white women. If Jewish women more likely to be tested were misclassified as non-Jewish white women, that would increase the difference between non-Jewish whites and groups less likely to be tested. We intentionally reclassified the 32 women in the study identified as Jewish as non-Jewish white and recalculated our hazard ratios. The new hazard ratios (not reported) were nearly identical to those reported in Table 3. This suggests there would have to be an implausibly high degree of misclassification to drive the differences we calculate between non-Jewish white women and black and Hispanic women.

DISCUSSION

Overview

Commercial testing for BRCA1/2 mutations and clinical guidelines outlining when and how these tests can be useful to guide cancer care have been available for over a decade, yet outside a handful of site-specific studies, very little is known about the use of these tests to guide cancer treatment. This is the first study, to our knowledge, assessing the rate of BRCA1/2 testing among a group of high-risk breast cancer patients in a large national sample. In this population of commercially insured patients with newly-diagnosed early onset breast cancer, we found low rates of testing even though such patients are all considered appropriate candidates for BRCA1/2 testing according to national guidelines.

Our finding that only 30% of newly diagnosed early onset breast cancer patients received BRCA1/2 testing is substantially lower than rates reported in other more specialized populations. A study of breast cancer patients seen between 1998 and 2007 in the University of North Carolina (UNC) Cancer Genetics Clinic, for example, found that 69% of patients with at least a 5% risk of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation according to the BRCAPro model received BRCA1/2 testing.11 A separate study of newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., found that among patients determined to have a 10% prior probability of BRCA1/2 mutations (also based on BRCAPro), 76% underwent testing. These earlier studies are distinct from ours in that they report testing rates conditional on women receiving advice to undergo testing. Our analysis measures the proportion of women who actually got tested, and does not assume that all women were offered testing. These prior studies were also conducted in large academic medical centers, while ours assesses routine clinical practice in diverse national clinical settings. As such, it is more reflective of the extent to which genetic testing has become integrated into clinical oncology as a tool for guiding treatment decisions nationally. Our results suggest that guideline-indicated BRCA1/2 genetic assessment among women with breast cancer may be occurring less frequently that previously realized.

Furthermore, few women who are tested do so prior to their initial breast cancer treatment when results might inform initial treatment decisions, for example whether or not to undergo prophylactic contralateral mastectomy. Without access to testing results, we were unable to determine whether or not those who got pre-treatment testing used the results to guide their initial treatment decisions. Those who were tested after treatment may have done so with an eye towards future prophylactic care (e.g. bilateral salpingo oopherectomy) or informing potentially at-risk relatives.

There are many possible reasons for the low rates of testing we observe, arising anywhere along a continuum of care from breast cancer diagnosis to the ultimate action taken with respect to BRCA1/2 testing. Clinicians must be aware of and understand the latest evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and care; collect and interpret family and clinical history information from the patient; and discuss possible testing with the patient and/or refer the patient for genetic counseling. There must be resources available from an insurer or the patient to pay for the test. Lastly, the patient must decide to proceed with the test. Factors at any point along this continuum – at the health system, provider or patient level – will affect BRCA1/2 testing rates.

The UNC and Georgetown studies found relatively high rates of testing conditional upon its offer (particularly when restricting their analyses to the year following diagnosis),11, 14 suggesting provider or systemic barriers are important contributors to the low utilization we observe in the present study.20 Physician knowledge of and compliance with practice guidelines is generally low, which may result in too few recommendations for testing.21 System characteristics may also impede testing. Genetic counseling is a strongly recommended component of the genetic testing process,1 and thus BRCA1/2 testing typically requires an additional appointment for the patient. This provides another opportunity for women to be lost to follow-up. The short supply of genetic counselors has also been a concern, although it is not known whether patients are seeking and failing to find genetic counselors.22 Our finding that HMO patients are less likely to be tested suggests administrative barriers such as prior authorization requirements or the use of restricted provider lists may also play a role in low utilization.

Beyond barriers affecting access to testing, some patients may have refused genetic testing when offered due to lower knowledge of hereditary cancer testing,23–26 personal preferences or beliefs,27 or fears that genetic risk information may used by an insurer or employer to discriminate against them.28–30 Differences in testing rates by race (see below) suggest that for blacks this may be of particular concern,31 reflecting historic injustices in medical research and genetics.32–34 Going forward, some of these fears may be allayed by the 2008 Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act.35

BRCA1/2 Testing and Underserved Populations

We observed significantly lower rates of BRCA1/2 testing for black, Hispanic, and low income women compared to others being served in the same large commercial health plans. It is these underserved populations that experience poorer treatment and higher mortality rates for breast cancer.13

Our finding of lower testing rates among black women mirrors the differences in genetic counseling and testing observed in other studies. Armstrong et al. employed a case-control design to study genetic counseling rates for women with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer, but without a cancer diagnosis themselves, in a large metropolitan health system and found that black women had one fifth the odds of pursuing genetic counseling compared to white women.10 It should be noted that these women were at risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer in the future, which has different implications for discrimination than testing among women with incident breast cancer where a key purpose of testing is tailoring treatment. A study of ovarian cancer patients seen at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center who were at high risk of BRCA1/2 mutations found that compared to white women, black women had a 75% lower odds of receiving offers of or referrals for genetic counseling, suggesting provider behavior is an important barrier to testing.20 The authors found no significant difference between white and Hispanic women. The UNC and Georgetown studies involved breast cancer patients specifically. When focusing on testing in the year following breast cancer diagnosis, the UNC study found that 66% of blacks received BRCA1/2 testing compared with 72% of whites (p=0.27) and the Georgetown study found that 78% of non-whites were tested compared with 85% of whites (p=0.66). However, when restricting their analysis to women who were tested more than one year after diagnosis, the UNC study found black breast cancer patients had less than half the odds of undergoing BRCA1/2 testing as white patients, despite similar access to counseling and care. Our findings are notable for demonstrating significantly lower rates of testing for blacks regardless of whether the analysis focused on the first year after diagnosis of not.

Ours is the first to report on BRCA1/2 testing rates among Hispanic breast cancer patients compared to whites. However, others have noted seemingly low rates of testing among Hispanic women, despite findings that the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among Hispanics is similar to other groups.36–38 Future studies are needed to confirm our results and explore how BRCA1/2 testing is affected by the relationship between provider characteristics among those serving Hispanic women with breast cancer and the preferences, beliefs, and barriers experienced by various Hispanic communities .

How might these data inform efforts to reduce disparities in BRCA1/2 testing? Care for black patients in particular is generally concentrated among a relatively small number of inpatient and outpatient providers, and these providers may face special challenges in providing high quality care for their patients.39–40 Hospitals serving more minority patients have poorer outcomes for breast cancer patients12 and lower quality of care, generally.41 A national survey of primary care physicians found that minority-serving physicians were significantly less likely to have ever ordered genetic testing to assess breast cancer risk.42 The extent to which care for minority cancer patients is concentrated among relatively few oncologists is unknown. Identifying that subset of oncologists who treat the vast majority of black and Latino women with breast cancer may prove a useful strategy for targeting provider and patient education and outreach efforts, as well as targeting additional resources for service delivery infrastructure.

Low-income women are also less apt to receive BRCA1/2 testing, even after controlling for race/ethnicity, insurance coverage, and average levels of educational attainment within one’s neighborhood. Previous studies have considered income as a predictor of genetic testing for hereditary cancers, but their findings were either borderline43 or insignificant.10 Although we use imputed income data, the monotonically increasing likelihood of BRCA1/2 testing we observe across five income categories is an indication of an income effect. The role of genetic counseling in the BRCA1/2 testing process may prove a greater burden to low-income women, who are more likely to hold less flexible jobs and rely on public transportation, thus may have more difficulty getting to medical appointments. Even modest cost-sharing requirements for testing may prove sufficiently burdensome to deter testing among low-income women. Our family income variable may also reflect education above and beyond the area-level measures of education we used, and thus reflect education-related differences in understanding of genetics and/or willingness to undergo genetic testing. Further investigation of the effect of socioeconomic status on test uptake is warranted.

Limitations and Conclusions

The strength of analyses based on administrative data is the ability to reliably capture specific trends and patterns in utilization over a large number of patients.44 However, there are limitations of our study that deserve mention. Our findings represent the experience of commercially insured patients with uneven national geographic distribution, and may not be generalizable to the U.S. as a whole. Some patients may have undergone genetic testing prior to our study period and others may have paid for testing out of pocket, rendering those tests invisible in our analyses. Certain variables may have been misspecified due to incomplete use or documentation in administrative data (e.g. family history), imputation processes (e.g., race/ethnicity, income), or incomplete data (addresses needed to compute neighborhood characteristics, such as average education level). With respect to the imputed race/ethnicity variable, additional research using validated, self-reported race/ethnicity is needed to further establish our findings. We believe, however, that potential miscoding is likely concentrated in the reference group (whites), which is large, and would therefore most likely bias results towards the null hypothesis of no association. Despite the limitations of our race variable, the magnitude of our results strongly suggest that disparities observed elsewhere in cancer care also exist in the provision of BRCA1/2 testing, and this warrants further investigation. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides the first national data on utilization of genetic testing to guide cancer treatment among a large national sample of newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients, documents low rates of testing among patients identified as appropriate for genetic assessment by national guidelines, and points to critical needs for further research investigating racial and socioeconomic differences in utilization of BRCA1/2 testing.

Despite calls for greater awareness on the part of patients and physicians,29 use of recommended genetic tests to assess risk of hereditary cancer remains low, even among younger cancer patients at high risk of mutations. Nevertheless, testing rates are rising. Efforts to educate providers about the benefits of genetic assessment45 and recent legislative protections against genetic discrimination35 may further stimulate additional usage in the future. Disparities in BRCA1/2 testing rates may lead to or compound disparities in cancer treatment and cancer outcomes. Intensified efforts are needed to ensure that poor and minority patients have access to clinical innovations, such as genetic assessment, shown to provide clinical value in tailoring cancer treatment and improving long-term outcomes. Low rates of BRCA1/2 testing among patients who would realize clinical benefit from knowing their mutation status represents a lost opportunity to tailor women’s individual treatment plans and maximally reduce risk of recurrence.

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support: This work was supported by a Nodal Award grant (A Shields, PI) from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center as part of the Center’s grant from the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA06516-43). Dr. Byfield was supported by a training grant from NCI (R25 CA92203-04).

We thank Anna Boonin Schachter, MPH and Nicole D. Colucci, BA for research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge Wylie Burke, MD, and John Z. Ayanian, MD, MPP for their comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jun 15;21(12):2397–2406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Sep 6;143(5):355–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed September 28, 2009];Genetic/Familial High-Risk Asessment: Breast and Ovarian V.1.2009. 2009 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/genetics_screening.pdf.

- 4.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, Adopted on February 20, 1996. J Clin Oncol. 1996 May;14(5):1730–1736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1730. discussion 1737–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myriad Genetics. [Accessed May 14, 2008];Myriad Genetics Awarded Three U. S. Patents And Eight International Patents. 2001 News release. Available at: http://www.myriad.com/news/release/210288.

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed September 28, 2009];Colorectal Cancer Screening V.1.2009. 2009 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/colorectal_screening.pdf.

- 7.Eisen A, Lubinski J, Klijn J, et al. Breast cancer risk following bilateral oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: an international case-control study. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 20;23(30):7491–7496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metcalfe K, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. Contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jun 15;22(12):2328–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy DE, Garber JE, Shields AE. Guidelines for genetic risk assessment of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: early disagreements and low utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Jul;24(7):822–828. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Jama. 2005 Apr 13;293(14):1729–1736. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susswein LR, Skrzynia C, Lange LA, Booker JK, Graham ML, 3rd, Evans JP. Increased uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among African American women with a recent diagnosis of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jan 1;26(1):32–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslin TM, Morris AM, Gu N, et al. Hospital factors and racial disparities in mortality after surgery for breast and colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 20;27(24):3945–3950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004 Mar-Apr;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Brogan B, et al. Utilization of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Apr;14(4):1003–1007. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ethnic Technologies LLC. South Hackensack, NJ: [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeFrank JT, Bowling JM, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Skinner CS. Triangulating differential nonresponse by race in a telephone survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007 Jul;4(3):A60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobin G, Groeneman S. Surveying the Jewish Population in the United States. San Francisco, CA: Institute for Jewish and Community Research; 2003. [Accessed October 6, 2010]. http://www.jewishdatabank.org/Archive/N-HARI-2001-Surveying_the_Jewish_Population_of_the_United_States.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.KnowledgeBase Marketing. AmeriLINK data. Richardson, TX: [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Asessment: Breast and Ovarian V.1.2004. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer LA, Anderson ME, Lacour RA, et al. Evaluating women with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: missed opportunities. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;115(5):945–952. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da08d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. Jama. 1999 Oct 20;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal E. Shortage of genetics counselors may be anecdotal, but need is real. Oncology Times. 2007;29(19):34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong K, Weber B, Ubel PA, Guerra C, Schwartz JS. Interest in BRCA1/2 testing in a primary care population. Prev Med. 2002 Jun;34(6):590–595. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Benkendorf J, et al. Ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about BRCA1 testing in women at increased risk. Patient Educ Couns. 1997 Sep-Oct;32(1–2):51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, Croyle RT, Freedman AN. Awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Community Genet. 2003;6(3):147–156. doi: 10.1159/000078162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, Trapido E. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Apr;15(4):618–623. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sankar P, Wolpe PR, Jones NL, Cho M. How do women decide? Accepting or declining BRCA1/2 testing in a nationwide clinical sample in the United States. Community Genet. 2006;9(2):78–86. doi: 10.1159/0000XXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong K, Calzone K, Stopfer J, Fitzgerald G, Coyne J, Weber B. Factors associated with decisions about clinical BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000 Nov;9(11):1251–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall M, Olopade OI. Confronting genetic testing disparities: knowledge is power. Jama. 2005 Apr 13;293(14):1783–1785. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson EA, Milliron KJ, Lewis KE, Goold SD, Merajver SD. Health insurance and discrimination concerns and BRCA1/2 testing in a clinic population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Jan;11(1):79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters N, Rose A, Armstrong K. The association between race and attitudes about predictive genetic testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004 Mar;13(3):361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones JH. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gamble VN. [Accessed July 30, 2010];Tuskegee Lessons. 2002 http://www.npr.org/programs/morning/features/2002/jul/tuskegee/commentary.html.

- 34.King PA. The past as prologue: race, class, and gene discrimination. In: Annas GJ, Elias S, editors. Gene Mapping: Using Law and Ethics as Guides. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harmon A. Congress Passes Bill to Bar Bias Based on Genes. The New York Times. 2008 May 2; [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE, et al. Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Mar 15;20(6):1480–1490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall MJ, Reid JE, Burbidge LA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in women of different ethnicities undergoing testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2009 May 15;115(10):2222–2233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Jul;14(7):1666–1671. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004 Aug 5;351(6):575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Jun 11;167(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Jun 25;167(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields AE, Burke W, Levy DE. Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: results of a national survey. Genet Med. 2008 Jun;10(6):404–414. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181770184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Duteau-Buck C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of BRCA counseling and testing decisions among urban African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Dec;11(12):1579–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnick DW, Hendricks AM, Comstock CB. Measuring quality of care: fundamental information from administrative datasets. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994 Jun;6(2):163–177. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/6.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins FS, Guttmacher AE. Genetics moves into the medical mainstream. Jama. 2001 Nov 14;286(18):2322–2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]