Abstract

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative disorder caused by expression of the fusion gene BCR-ABL following a chromosomal translocation in the hematopoietic stem cell.1 Therapeutic management of CML uses tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which blocks ABL-signaling and effectively kill peripheral cells with BCR-ABL. However, TKIs are not curative, and chronic use of is required in order to treat CML. The primary failure for TKIs is through development of a resistant population due to mutations in the TKI binding regions.2, 3 This led us to develop the mutant coiled-coil, CCmut2, an alternative method for BCR-ABL signaling inhibition by targeting the N-terminal oligomerization domain of BCR, necessary for ABL activation.4 In this report we explore additional pathways which are important for leukemic stem cell survival in K562 cells. Using a candidate-based approach we test the combination of CCmut2 and inhibitors of unique secondary pathways in leukemic cells. Transformative potential was reduced following silencing of the leukemic stem cell factor Alox55 by RNA interference. Furthermore, blockade of the oncogenic protein MUC-16 by the novel peptide GO-201 yielded reductions in proliferation and increased cell death. Finally, we found that inhibiting macroautophagy7 using chloroquine in addition to blocking BCR-ABL signaling with the CCmut2 was most effective in limiting cell survival and proliferation. This study has elucidated possible combination therapies for CML using novel blockade of BCR-ABL and secondary leukemia-specific pathways.

Keywords: CML, Coiled-Coil, CCmut2, zileuton, GO-210, chloroquine, combination therapy, K562, BCR-ABL

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) manifests following a reciprocal chromosomal translocation between the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene and the Abelson tyrosine kinase (ABL) gene [t(9;22)(q34;q11)] in the hematopoietic stem cell.1, 8 Upon expression of the BCR-ABL fusion protein (a constitutively active tyrosine kinase) a leukemic stem cell (LSC) is generated, driving LSC self-renewal and expansion of BCR-ABL-expressing lineages including myeloid and lymphoid blasts.9, 10 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are competitive inhibitors for the ATP binding site of ABL and make up the therapeutic arsenal for disease management.3 We have previously described a unique interfering peptide, CCmut2, able to disrupt BCR-ABL homooligomers. 4 Moreover, oligomerization is necessary for ABL activation.11 Interestingly, oligomeric disruption of trans-auto phosphorylation by CCmut2 exacts its activity via the coiledcoil domain in BCR, leading to an overall similar effect seen with TKIs – reduced phosphorylation of ABL and downstream targets STAT5 and Crk-L, induction of apoptosis and reduction in proliferation.4, 12

Single-agent TKI therapy for CML has effectively limited disease progression for the majority of patients.3 However, resistance to therapy and persistence of a subset of leukemic cells despite TKI activity13 demonstrate the necessity for multiple-agent therapy, especially to address the LSC population.10, 14 Previous reports have demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity when using a TKI in combination with a second agent targeting a BCR-ABL independent pathway,6, 7, 15, 16 two of which have moved into clinical trials (NCT01130688; NCT01227135). Though these are promising developments to circumvent molecular failure, the TKI component will likely continue to have problems with resistance.3, 17, 18 The CCmut2 may be less prone mutational resistance selection, mainly due to the highly specific and selective nature of a large interaction domain.4 This draws a parallel similar to differences in specificity between small molecules versus antibodies for cancer therapy.19 Therefore, a multiple-agent therapeutic approach involving the CCmut2 may be superior to TKI single-agent therapy (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

A) Model of multi-agent vs. single agent therapy for CML. The BCR-ABL translocation is thought to arise in the stem cell population, giving rise to leukemic stem cells (LSC). If untreated, the progeny from the LSC expressing the constitutively active tyrosine kinase fusion protein BCR-ABL give rise to expanded cell populations which is fatal to the patient. Current clinical care uses targeted therapy against the kinase ABL, which does treat the disease. However, mutations within the ABL gene can generate a resistant population which can lead to leukemic cell survival. Using a BCR-targeted inhibitor is hypothesized to decrease the possibility of resistance, and adding a second agent can enhance cell killing. B) Left: A CML cell and a simplified disease pathway of CML (black arrows). Current treatment modalities (TKIs) can act to reverse these effects; however a potential escape from conventional therapy through the autophagy pathway is depicted with grey arrows. Right: Experimental strategies for addressing untreated, or resistant populations of CML disease states. (1) The CCmut2 targets the BCR domain with a similar effect on in vitro cells as TKIs; (2) The oncoprotein MUC-1C can be disrupted by RNA interference (RNAi) or the peptide inhibitor GO-201; (3) Autophagy blockade can be achieved by chloroquine (CQ) or by RNAi targeting Atg7; (4) The LSC enhancing factor Alox5 is inhibited by targeting 5-LO metabolism with zileuton (zil) or degrading Alox5 message using RNAi.

We were interested in discovering whether enhanced apoptotic activation or reduction in proliferation could be achieved by combining CCmut2 with secondary agents having independent mechanisms of action.20 Here we detail the results of this peptide (delivered as a gene and transcribed in vitro) in combination with additional small molecule or biologic agents. Secondary target candidates were selected based on previous reports of drugs known to be effective when used in combination with imatinib, and those drugs found to be effective only against leukemic (vs. normal hematopoietic) cells.18 Additional criteria lead to the selection of key proteins involved in CML progression, namely ATG7,7 MUC-1,21 and Alox5.15 These targets were chosen because they do not cause loss of hematopoietic stem cell function. RNA interference (RNAi) or molecular disruption of these pathways was investigated.

The selection of and rationale for pathways and molecular agents for combination with the CCmut2 are as follows: 1) ATG7 and chloroquine (CQ). Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy from this point on) is a cellular process activated in starvation conditions to improve recycling of cell components and enhance cell survival.22 This pathway is becomes important in cancer as a mechanism for cells escape elimination when treated with anticancer agents.23 ATG7 is necessary for autophagy, and its inhibition blocks formation of the autophagosome, an early step in the autophagy process; while CQ inhibits lysosomal acidification, which eliminates breakdown of products contained in the autophagosome blocking cellular autophagy in the later stages.23 Specifically in CML, combination of imatinib and CQ enhance leukemic cell killing.7 For this reason we were interesting in blocking autophagy in combination with CCmut2. 2) Alox5 and zileuton (zil). The arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (Alox5) gene product 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LO) is responsible for leukotriene synthesis from arachadonic acid (AA), reports indicate increased AA in CML cells.5, 18 This enhances proliferation and inhibits differentiation in leukemic stem cells (with Bcr-Abl). Knockout of Alox5 or treatment with a 5-LO inhibitor (zil) is known to change the proliferative capacity of CML cells.15, 24, 25 3) MUC-1C and GO-201. MUC-1 is a known oncogene widely expressed in cancer cells in general and in CML cells specifically.21, 26 Kufe and colleagues have reported association of the cytoplasmic portion of MUC-1 (MUC-1C) with BCR-ABL, enhancing the oncogenic cytoplasmic signaling of BCR-ABL. Furthermore, the use of GO-201, a specific inhibitor of MUC-1C with imatinib have shown reduction in proliferation and induced differentiation in CML cells.6, 16 These interactions are depicted in Figure 1B.

In this report, these agents in combination with CCmut2 were found to improve therapeutic potency in K562 cells. Transformative ability was most reduced by inhibiting protein expression of Alox5 using RNAi in combination with the CCmut2. Reduction in proliferative capacity resulted largely due to CCmut2 alone, but was further decreased by GO-201. Finally, increased caspase activity was seen with CQ and CCmut2, while combinations of either GO-201 or CQ and CCmut2 enhanced the apoptotic and necrotic cell population as visualized by Annexin-V and 7-AAD staining.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

RNAi constructs were targeted against human Atg7, Alox5, MUC-1 or luciferase control. Target sequences for Atg7 or MUC-1 were derived from previous reports6, 7 while Alox5 (NM_000698) RNAi sequence was designed using BLOCK-iT™ RNAi Designer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). RNAi sequences are as follows: Alox5 (5’- ggaatgacttcgccgactttg-3’); Atg7 (5’-cagtggatctaaatctcaaactgat-3’)7; MUC-1C (5’- aagttcagtgcccagctctac-3’)6. Oligonucleotides encoding short hairpins against the following transcripts were synthesized at the University of Utah core facilities: Alox5 top (5’-gatccggaatgacttcgccgactttggaagcttgcaaagtcggcgaagtcattccttttttggaagc-3’) and bottom (5’-ggccgcttccaaaaaaggaatgacttcgccgactttgcaagcttccaaagtcggcgaagtcattccg-3’); Atg7 top (5’-gatccgcagtggatctaaatctcaaactgatgaagcttgatcagtttgagatttagatccactgttttttggaagc-3’) and bottom (5’-ggccgcttccaaaaaacagtggatctaaatctcaaactgatcaagcttcatcagtttgagatttagatccactgcg-3’); MUC-1 top (5’-gatccgaagttcagtgcccagctctacgaagcttggtagagctgggcactgaacttttttttggaagc-3’) and bottom (5’-ggccgcttccaaaaaaaagttcagtgcccagctctaccaagcttcgtagagctgggcactgaacttcg-3’). Top and bottom strands were annealed and then cloned into the Gene Silencer shRNA Expression Vector pGSH1-GFP (Genlantis, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer instructions. The pEGFP-C1 parent plasmid was purchased from Clontech laboratories (Mountain View, CA); the coiled-coil (pEGFP-CC) or mutant coiled-coil (pEGFP-CCmut2 ) are described elsewhere.4

Cell Lines and Transfections

Cells culture and transfections were carried out as described previously.4 Briefly, K562 cells were cultured in complete RPMI medium with 10% FBS, 1% Pen-Strep-Glut, and 0.1% Gentamycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. DNA constructs were transfected with the Amaxa nucleofection system (Lonza Bio, Basel, Switzerland), using 6 µg of DNA in 100 NL Solution V with 2 million cells, and then returned to complete RPMI medium.

Western Blotting

Cells were counted on a hemocytometer, pelleted and frozen at −80°C overnight. Cell pellets were resuspended in RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Scientific/Pierce Protein Biology Products, #89900, Kalamazoo, MI ). A BCA Protein assay was performed (Thermo Scientific, #23225) and 10 µg of protein was loaded in each lane of a denaturing gel. Standard western blotting procedures were used.4 Antibodies used to detect Atg7 (Sigma-Aldrich, #A2856, St. Louis, MO), LC3A/B (Sigma-Aldrich, #L8918), MUC-1C (Thermo Scientific, #MUC-1 Ab-5/HM-1630), Alox5 (Abcam, #ab115764, Cambridge, MA), Actin (Abcam, #ab1801), and eIF4E (Cell Signaling Technology, #C46H6, Danvers, MA) primary antibodies were used. HRP conjugated secondary antibodies were anti-Armenian hamster (Abcam, #ab5745) or anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, #7074). Quantification of bands using relative densitometry was completed using AlphaView SA (Protein Simple, v3.0, Santa Clara, CA). For LC3II/I ratios, background corrected sum values for each band were calculated as a ratio to eIF4E control. Then LC3-II percent control was divided by LC3-I percent control. This gives a relative ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I conversion.

Colony Forming Assay

pGSH1 constructs expressing shRNA sequences against Atg7, MUC-1, or Alox5 were transfected and cultured 4 days to ensure knockdown. One day following transfection, Genticin reagent (Life Technologies) was added at a concentration of 500 µg/ml in complete RPMI. On day 4, a second construct was transfected (pEGFP-C1; -CC; or -CCmut2). Dual-transfected cells were resuspended in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco's Medium containing 2% FBS (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), and 1,000 cells were seeded in Methocult H4230 methylcellulose medium (Stem Cell Technologies). Imatinib mesylate (IM #CT-IM001, Chemie-Tek, Indianapolis, IN) was added to untransfected K562 cells in Methocult at the time of seeding. Transformation potential was assessed 7 days after seeding cells by counting colonies in 200 µM2.

Drug Treatments

In all cases, small molecule or peptide-based inhibitors were added to transfected cells 6 hours after transfections unless otherwise noted. GO-201 (Sigma-Aldrich, #G7923) is a well-described peptide inhibitor of MUC-1C,27 and was used at a final concentration of 5 µM in 1X PBS (Life Technologies, #14190-144). Zileuton (Sigma-Aldrich, #Z4277) is a small molecule inhibitor active against 5-lipoxygenase (the protein product of Alox5) and was used at a final concentration of 20 µM dissolved in DMSO. Chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich, #C6628) is an inhibitor of lysosomal acidification (autophagosomal activation) and was used at a final concentration of 10 µM.

Cell Proliferation

K562 cells were transfected with EGFP, CC or CCmut2, followed by drug treatment 6 hours later. Trypan blue exclusion4 was assessed 48 hours after transfection to determine cell proliferation/viability.

Caspase 3/7 Assay

Cells were transfected as indicated above (in "Cell Lines and Transfections") followed by drug treatment 6 hours later. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were counted, pelleted and frozen at −80°C overnight. Cells were resuspended, lysed and processed according Caspase Glo 3/7 manufacturer instrutions (Promega, Madison, WI). Luminescence was measured after one hour at 26°C on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Annexin-V/7-AAD Assay

Cells were transfected and treated as described above (in "Cell Lines and Transfections") followed by drug treatment 6 hours later. At 48, 72, or 96 hours cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL Annexin-V binding buffer (Life Technologies, #V13246) stained with 1 nM 7-AAD (Life Technologies, # A1310) and a 1:20 dilution of Annexin-V-APC (Life Technologies, #A35110). Samples were sorted using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer according to GFP positivity (10,000 GFP events were collected). Cells were then sorted according to apoptotic (Annexin-V) and necrotic (7-AAD) markers. Data was further analyzed using FlowJo flow cytometry analysis software (Tree Star Inc, Ashland, OR).

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. from at least 3 independent experiments. Significance of differences between groups was assessed in GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) using either a student’s t-test, two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test, or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

BCR-based inhibition of BCR-ABL with Alox5 knockdown reduces transformation potential of K562 cells

5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), the protein product of Alox5, mediates processes such as inflammation and oxidative stress through leukotriene synthesis. Because of this, 5-LO antagonists are an important therapy for inflammatory diseases and have also been suggested for cancer therapy.28 Reports of potential anti-proliferative effects in hematologic malignancies from loss of Alox5 or 5-LO inhibitors surfaced in the 1980’s29, 30 and recently were bolstered in a CML in vivo model by data from Chen and colleagues.5, 15, 31

To determine the contribution of several pathways to transformative ability (measured by colony forming cells), selected pathways were disrupted by knockdown of key genes regulating each pathway using shRNA expressing constructs. Western blotting for protein products of Atg7, MUC-1 and Alox5 demonstrated successful knock down of all targets (Figure 2A, second lane of each pair) when compared to control shRNA against luciferase control (Figure 2A, shLuc, first lane of each pair). These data are quantified using band densitometry and expressed as percent shLuc (Figure 2B). These constructs were then used in combination with GFP control, wild-type coiled-coil (CC), or mutant coiled-coil (CCmut2)4 in a week long transformation study. Transient expression of shAlox5 and CC or CCmut2 resulted in significant reduction of colonies (Figure 3, shAlox5 group - far right bars) compared to GFP control and shAlox5 dual expression (Figure 3, shAlox5 group – 3rd to right bar, grey).

Figure 2.

A) Representative western blot of protein expression for Atg7, MUC-1, and Alox5 after 96 hours following transfection with pGSH1-shLUC-GFP (left lane) compared to RNA interference targeting genes of interest (right lane). B) Knockdown via RNAi is depicted based on semi-quantitative band densitometry for each construct compared to shLuc control. Each short-hairpin RNAi construct resulted in significant knockdown of their targets. Student’s t-test, **p<0.01; *p<0.05; n=3.

Figure 3.

Colony forming assay of dual-transfected short-hairpin and experimental constructs reveals a significant combination effect of Alox5 and CC or CCmut2. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, *p<0.05, n≥3.

Chloroquine combinations block an upregulated autophagy pathway following BCR-ABL inhibition

Autophagy is a degradative process used by cells to break down intracellular material via lysosomes. Autophagy can promote or suppress oncogenesis depending on the cellular context;22 however, induction of autophagy provides a survival mechanism in BCR-ABL cells treated with imatinib (cells undergoing stress – see Figure 1B).7, 32 Though previous reports indicated enhanced autophagy following introduction of kinase inhibitors,7, 32, 33 this pathway has not been previously investigated following expression of the CCmut2. Additionally, since no reduction in transformative ability was observed following knockdown of Atg7, we proceeded to investigate whether autophagy is activated following transfection of GFP, CC or CCmut2. The conversion of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) from LC3-I to LC3-II was used to monitor autophagy. This is the case when comparing lanes 3 and 4 or lanes 7 and 8. Because cellular levels of LC3-II are indicative of the number of autophagosomes (e.g. an increase in autophagy),34 increases in LC3-II protein expression were measured by immunobloting. When no autophagy occurs, a more prominent LC3-I band will be visible, indicating presence of the precursor and cytoplasmic LC3-I (i.e. LC3II/I <1.0). This is visible in Figure 4, lanes 1–2; 5–6. When autophagy occurs, and inhibitors are added to eliminate LC3-II breakdown via the lysosome, LC3-II becomes the prominent band (i.e. LC3II/I >1.0).34, 35

Figure 4.

Autophagy occurs in K562 cells and is increased following exposure to IM or the mutant coiled-coil (CCmut2). Shown is a representative western blot for LC3-I/II and at 24 hours. Treatment with imatinib or transfection CCmut2 in concert with CQ treatment increases autophagic flux, indicated by LC3-II expression compared to LC3-I. This is given as the LC3-II/I ratio at 24 hours indicated in table below figure. n=3

LC3-II/LC3-I ratios7, 35 were calculated following exposure to 5 µM imatinib (Figure 4, lanes 3 and 4) or transfections and with or without CQ at 12 hours (Figure 4, lanes 5–8). The data represented in figure 4 demonstrate little to no activation of autophagy in untreated or GFP transfected K562 cells (Figure 4, lanes 1–2; 5–6). Autophagy is activated by inhibition of BCRABL using either BCR or ABL inhibitors at 24 hours (Figure 4, lanes 3–4; 7–8). Similar trends were seen at 12 hours (data not shown).

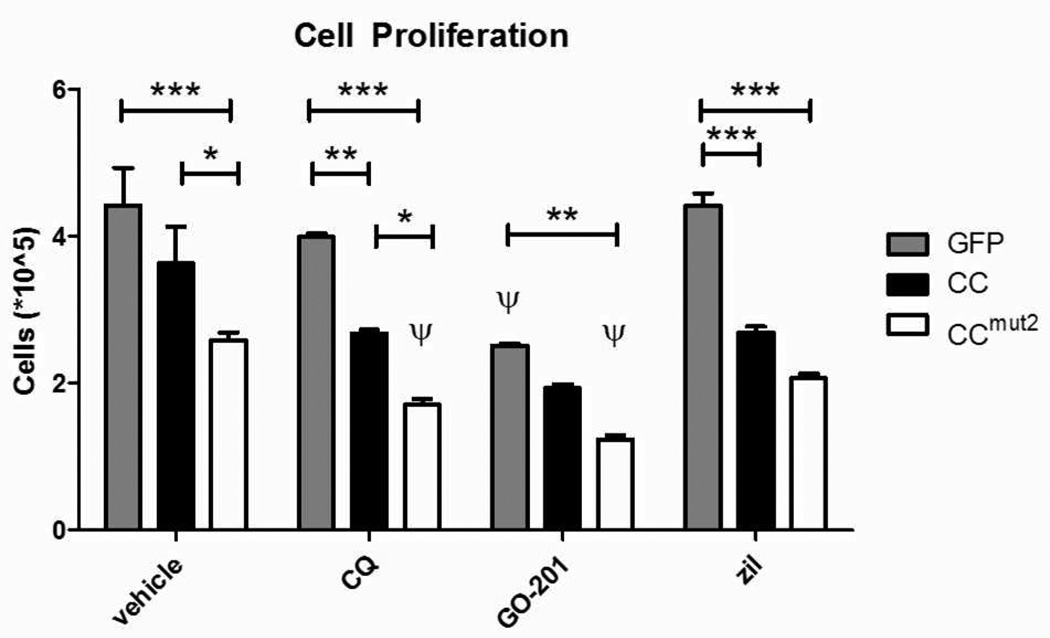

CQ and GO-201 further diminish proliferative capacity of K562 cells beyond reductions seen using CCmut2 alone

MUC-1 is a membrane-bound glycosylated phosphoprotein whose normal function protects the body from chemicals/bacteria through its polarized expression on epithelial cell surfaces.21 The cytoplasmic domain of MUC-1, called MUC-1C, interacts with the BCR portion of BCR-ABL to promote continued oncogenic signaling.6 A peptide inhibitor of MUC-1C has been shown to downregulate BCR-ABL and inhibit cell growth,16 indicating its value as a therapeutic target.

We previously demonstrated4 decreased proliferation following transient expression of CCmut2, and this data is represented here (Figure 5, vehicle treated). To determine the effects of selected pathways in combination with BCR-mediated inhibition of ABL by the mutant coiled-coil, additional experiments were carried out as before4 with drugs added six hours after transfection. Untreated groups were scaled to previous data and compared to treated cells at 48 hours. A significant reduction was seen across all samples when treated with the CCmut2 (Figure 5, white bars), consistent with previous work,4 and further reductions were seen in the CQ and GO-201 treated groups when transfected with CCmut2 (CQ and GO-201 groups, white bars). In fact, GO-201 treatment reduces proliferation independent of transfected group, but further diminishes reduction in proliferation most in combination with the mutant coiled-coil (GO-201 group, white bars).

Figure 5.

K562 cell proliferation as indicated by trypan blue dye exclusion reveals that transfected cells subsequently treated with drugs can further depress proliferative capacity of K562 cells. CCmut2 has a significant effect alone, compared to GFP control. Drug addition does not significantly affect GFP-treated cells, with the exception of GO-201. CC + drug and CCmut2 + drug have further reductions in proliferation compared to vehicle treated cells. GO-201 combined with CCmut2 has a potent reduction in proliferation compared to other drugs at 48 hours. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test have the following significance levels: *p<0.05, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, n≥3. ψ indicates at least p<0.05 following a one-way ANOVA comparing drug treated to control (vehicle treated) in matched transfected groups, Bonferroni post-test.

CQ enhances activity of effector caspases 3/7 in concert with CCmut2

We next investigated whether increases in apoptotic signaling could be enhanced using transient transfection of constructs with drug combinations at 48 hours. Early apoptotic events can be indicated by executioner caspase 3 or 7 cleavage products. These products were measured using a luminescent DEVD substrate.36 The only combination which resulted in a significant (3 fold) increase in caspase 3/7 activity was the CCmut2 with CQ treated group (Figure 6, compare GFP and CCmut2 bars in the CQ group). Other combinations did not significantly enhance caspase 3/7 activity.

Figure 6.

Apoptosis induction measured by activated caspase 3 or 7 is increased in CQ treated cells when comparing GFP control and CCmut2. Data is expressed as fold vehicle control. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests. n=5; *p<0.05

Increased apoptotic and necrotic activity are observed following CQ combinations

In addition to effector caspase activity, later stage apoptosis and necrosis were measured using cell permeable reagents demonstrating apoptotic (phosphotidylserine externalization recognized by Annexin-V) or necrotic (nuclear membrane permeability by DNA intercalation of 7-AAD) events. At the earliest time measured, CQ and GO-201 increased cell death response (Figure 7A and D), though GO-201 affected only the CCmut2 transfected population, and was not significantly different than the vehicle treated group (Figure 7D), CQ has a broader impact potentiating CC transfected population specifically (Figure 7A). 72 hours after initial transfection, the singular impact of the CCmut2 transfected cells becomes clear as significant increases are seen in the apoptotic population (Figure 7B). The GO-201 apoptotic increase seen at 48 hours (Figure 7A) is reflected in the necrotic population at 72 hours (Figure 7E). CCmut2 alone significantly increases apoptosis at 96 hours (Figure 7C) and is significantly enhanced by addition of CQ. While zil also increases apoptosis, it is not above vehicle control levels. Necrosis at 96 hours appears only to be impacted by CCmut2 (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Transfected and treated cells were subjected to Annexin-V (apoptotic, A-C) and 7- AAD (necrotic, D-F) analysis at 48, 72, and 96 hours. Drug-treated populations have a larger initial effect on apoptosis and necrosis, followed by a transfection-caused increase in apoptosis beginning at 72 hours. GO-201 significantly shifts the CCmut2 treated cells towards apoptosis at 48 hours and this affect can be seen to reflect an enhanced necrotic population at 72 hours within the GO-201 group, however neither of these are significantly different than untreated control. A significant apoptotic increase is observed in the vehicle conditions including in the CCmut2 transfected cells after 72 hours, translating to increased necrosis at 96 hours in all conditions, due only to CCmut2. The CQ treated group shows an early enhancement of apoptosis (48–72 hours) compared to vehicle control in the CC group. At 96 hours, within the CQ treatment group, both GFP and CCmut2 are significantly increased compared with vehicle control. n=3; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. ψ indicates at least p<0.05 following a one-way ANOVA comparing drug treated to control (vehicle treated) in matched transfected groups, Bonferroni post-test.

Discussion

In this study, we report that drug and transfection combinations can enhance elimination of K562 CML cells. Using a novel genetic therapy (CCmut2) we demonstrated enhanced apoptotic cell death and reduced proliferation ability of CCmut2 expressing K562 cells consistent with previous reports.4, 12 We then evaluated transformative and proliferative capacity of cells using a combination of constructs or drugs focused on inhibiting BCR-ABL signaling and other leukemia-specific pathways. Though we did not see a significant reduction in transformative ability with transfection of single plasmid alone, the combination of constructs targeting Alox5 knockdown with CCmut2 elucidated the importance of Alox5 in long-term cell survival and colony forming ability (Figure 3). Previous studies involving Alox5 in CML do not address transformative ability of K562 cells, but focus more on stem-like cells in in vivo models. 5, 15, 24, 31, 37 Though other assays did not indicate a robust role for Alox5 in apoptosis or proliferation, the fact that Alox5 could be an important target in blast-phase CML cells in addition to a primordial CML stem cell is an interesting observation.

We also demonstrated further reduction in proliferative capacity resulting from the combination of GO-201 or CQ and CCmut2 transfections (Figure 5). Additionally, effector caspases 3 and 7 activation increased following combination with CQ at 48 hours (Figure 6). Finally, combining CQ and CCmut2 appear to enhance apoptosis/necrosis when both exist in the cell long enough to have an affect individually (Figure 7). Interestingly, increases in apoptosis and necrosis were primarily due to the small molecule drug (CQ) or peptide therapeutic (GO-7201) (Figure 7A, D) then later affected by the transfection (Figure 7B-C; E-F). This indicates a temporal shift in the activity and effect of the therapeutic which may become important in future studies. Together, these data suggest further increases are achievable using a second agent in addition to the therapeutic interfering peptide CCmut2. Specifically, combinations with CCmut2 and CQ appear to have the broad effect on proliferation and apoptosis, followed by GO-201. In fact, the hydroxychloroquine derivative of CQ is currently being investigated as an adjuvant to IM therapy for CML in a clinical study (NCT01227135). Future studies will evaluate the most potent combinations in primary patient samples, including stem-like CML cells. Importantly, this report demonstrates the efficacy of a combination based approach using small molecule or peptide-based inhibitors to target both the causative oncogenic BCR-ABL, but also key alternative pathways in a blast-crisis CML cell line.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the use of DNA/Peptide Core and Flow Cytometry Core (NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA042014, Huntsman Cancer Institute). We would like to thank graphic artist Diana Lim for contributions to figure 1. We would also like to thank Klara Howard, Geoff Miller, Ben Bruno, Rian Davis, Mohanad Mossalam, Abood Okal and Karina Matissek for scientific discussions.

Funding Sources

This project was funded by NCI CA129528-05 (C.S.L.) and in part by a grant to the University of Utah from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute through the Med into Grad Initiative (D.W.W.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CML

chronic myeloid leukemia

- BCR

breakpoint cluster region

- ABL

Abelson

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- ATP

Adenosine-5'-triphosphate

- LSC

leukemic stem cell

- IM

imatinib

- CC

coiled-coil

- RNAi

RNA interference

- shRNA

short-hairpin RNA

- GFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- LC3

light chain-3

- zil

zileuton

- CQ

chloroquine

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The project was conceived by D.W.W. with guidance from C.S.L. Experiments were planned and performed by D.W.W. with advice from C.S.L., and were analyzed by D.W.W. and C.S.L. D.W.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartram CR, de Klein A, Hagemeijer A, van Agthoven T, Geurts van Kessel A, Bootsma D, Grosveld G, Ferguson-Smith MA, Davies T, Stone M, et al. Translocation of c-ab1 oncogene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306(5940):277–280. doi: 10.1038/306277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hare T, Eide CA, Deininger MW. Bcr-Abl kinase domain mutations, drug resistance, and the road to a cure for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110(7):2242–2249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-066936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woessner DW, Lim CS, Deininger MW. Development of an effective therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer J. 2011;17(6):477–486. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318237e5b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon AS, Pendley SS, Bruno BJ, Woessner DW, Shimpi AA, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Lim CS. Disruption of Bcr-Abl coiled coil oligomerization by design. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(31):27751–27760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Li D, Li S. The Alox5 gene is a novel therapeutic target in cancer stem cells of chronic myeloid leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(21):3488–3492. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano T, Ito M, Raina D, Wu Z, Rosenblatt J, Avigan D, Stone R, Kufe D. MUC1 oncoprotein regulates Bcr-Abl stability and pathogenesis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Cancer research. 2007;67(24):11576–11584. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellodi C, Lidonnici MR, Hamilton A, Helgason GV, Soliera AR, Ronchetti M, Galavotti S, Young KW, Selmi T, Yacobi R, Van Etten RA, Donato N, Hunter A, Dinsdale D, Tirro E, Vigneri P, Nicotera P, Dyer MJ, Holyoake T, Salomoni P, Calabretta B. Targeting autophagy potentiates tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced cell death in Philadelphia chromosome-positive cells, including primary CML stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119(5):1109–1123. doi: 10.1172/JCI35660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowley JD. Letter: A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243(5405):290–293. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anafi M, Gazit A, Gilon C, Ben-Neriah Y, Levitzki A. Selective interactions of transforming and normal abl proteins with ATP, tyrosine-copolymer substrates, and tyrphostins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(7):4518–4523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson E, Holyoake T. The chronic myeloid leukemia stem cell. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(Suppl 4):S376–S381. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.s.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Subrahmanyam R, Wong R, Gross AW, Ren R. The NH(2)-terminal coiled-coil domain and tyrosine 177 play important roles in induction of a myeloproliferative disease in mice by Bcr-Abl. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21(3):840–853. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.840-853.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon AS, Miller GD, Bruno BJ, Constance JE, Woessner DW, Fidler TP, Robertson JC, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Lim CS. Improved coiled-coil design enhances interaction with Bcr-Abl and induces apoptosis. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2012;9(1):187–195. doi: 10.1021/mp200461s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbin AS, Agarwal A, Loriaux M, Cortes J, Deininger MW, Druker BJ. Human chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells are insensitive to imatinib despite inhibition of BCR-ABL activity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121(1):396–409. doi: 10.1172/JCI35721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Hare T, Deininger MW, Eide CA, Clackson T, Druker BJ. Targeting the BCR-ABL signaling pathway in therapy-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(2):212–221. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Hu Y, Zhang H, Peng C, Li S. Loss of the Alox5 gene impairs leukemia stem cells and prevents chronic myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):783–792. doi: 10.1038/ng.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin L, Ahmad R, Kosugi M, Kawano T, Avigan D, Stone R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Terminal differentiation of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells is induced by targeting of the MUC1-C oncoprotein. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(5) doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.5.12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warsch W, Kollmann K, Eckelhart E, Fajmann S, Cerny-Reiterer S, Holbl A, Gleixner KV, Dworzak M, Mayerhofer M, Hoermann G, Herrmann H, Sillaber C, Egger G, Valent P, Moriggl R, Sexl V. High STAT5 levels mediate imatinib resistance and indicate disease progression in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(12):3409–3420. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naka K, Hoshii T, Hirao A. Novel therapeutic approach to eradicate tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistant chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cancer science. 2010;101(7):1577–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai K, Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):714–727. doi: 10.1038/nrc1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaelin WG., Jr The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(9):689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brossart P, Schneider A, Dill P, Schammann T, Grunebach F, Wirths S, Kanz L, Buhring HJ, Brugger W. The epithelial tumor antigen MUC1 is expressed in hematological malignancies and is recognized by MUC1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Cancer research. 2001;61(18):6846–6850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. Death by design: apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(6):663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livesey KM, Tang D, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. Autophagy inhibition in combination cancer treatment. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10(12):1269–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng C, Chen Y, Shan Y, Zhang H, Guo Z, Li D, Li S. LSK Derived LSK(-) Cells Have a High Apoptotic Rate Related to Survival Regulation of Hematopoietic and Leukemic Stem Cells. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Baghdadi T, Abonour R, Boswell HS. Novel combination treatments targeting chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12(2):94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong XY, Kaul S, Bastert G. Evaluation of MUC1 and EGP40 in bone marrow and peripheral blood as a marker for occult breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;264(4):177–181. doi: 10.1007/s004040000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin L, Ahmad R, Kosugi M, Kawano T, Avigan D, Stone R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Terminal differentiation of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells is induced by targeting of the MUC1-C oncoprotein. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(5):483–491. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.5.12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: regulation of expression and enzyme activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(7):332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder DS, Castro R, Desforges JF. Antiproliferative effects of lipoxygenase inhibitors on malignant human hematopoietic cell lines. Experimental hematology. 1989;17(1):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukada T, Nakashima K, Shirakawa S. Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors show potent antiproliferative effects on human leukemia cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;140(3):832–836. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Peng C, Sullivan C, Li D, Li S. Novel therapeutic agents against cancer stem cells of chronic myeloid leukemia. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10(2):111–115. doi: 10.2174/187152010790909326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ertmer A, Huber V, Gilch S, Yoshimori T, Erfle V, Duyster J, Elsasser HP, Schatzl HM. The anticancer drug imatinib induces cellular autophagy. Leukemia. 2007;21(5):936–942. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han W, Pan H, Chen Y, Sun J, Wang Y, Li J, Ge W, Feng L, Lin X, Wang X, Jin H. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors activate autophagy as a cytoprotective response in human lung cancer cells. PloS one. 2011;6(6):e18691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140(3):313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3(6):542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayascas JR, Yuste VJ, Benito E, Garcia-Fernandez J, Comella JX. Isolation of AmphiCASP-3/7, an ancestral caspase from amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae). Evolutionary considerations for vertebrate caspases. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9(10):1078–1089. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan C, Peng C, Chen Y, Li D, Li S. Targeted therapy of chronic myeloid leukemia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(5):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.