INTRODUCTION

The health status of Native American adolescents in the United States is below that of the general adolescent population with striking differences in areas such as depression, suicide, anxiety, substance abuse, general health status, and leaving school before completion (1). The death rate for Native American adolescents is twice that of adolescents of other racial or ethnic backgrounds and for Native American adolescent boys, the rate is nearly three times higher (2). Furthermore, most of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality for Native American adults can be traced to the health compromising behaviors of adolescence. Alcohol abuse is the leading and perhaps most costly risk factor among Native American youth today, underlying many major causes of Native American deaths and contributing to an array of physical conditions and premature death. Alcohol abuse is also a warning for co-occurring risky behaviors such as: (a) the use of tobacco, and marijuana, drunk driving and riding with a drunk driver; (b) risky sexual behaviors; and (c) suicidal behaviors (3,4). While Native American youth generally report that they use substances as frequently, or more frequently than other youth, there is a major difference in the age of first involvement and the degree of involvement (2). Native American youth begin abusing substances at an earlier age, with greater degrees of frequency and amount and they experience more negative consequences. By twelfth grade, 80% of Native American youth are active drinkers and usually have close ties to substance abusing peers, do not perform well in school, do not strongly identify with Native American culture, and come from families where family members also abuse substances (5).

Currently, Oklahoma contains the second largest population of Native Americans in the United States. Most of the data regarding substance abuse among Oklahomans are reported as aggregate for the overall population without specific detail concerning Native Americans. In 2008, the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (ODMHSAS) reviewed state and national data to create a State of the State report on mental health and substance abuse in Oklahoma. The report indicated that Oklahomans in general and especially children need more health services than are currently available. Access to behavioral health services is much more limited for children and adolescents, with less than half the youth needing services receiving them. According to the ODMHSAS (6), 80% of youth in Oklahoma who need substance abuse services are not receiving them and Oklahoma ranks 47th out of 50 states for Child Well-Being.

STUDY SETTING

The study was conducted in Oklahoma with the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians who are the 8th largest tribe in Oklahoma and inhabit a 14 county jurisdictional area. Historically, the Keetoowah-Cherokee were known as “Kituwah” and referred to themselves as the “principle people” (7). The way of life and roles of the Keetoowah-Cherokee began to change as a result of colonization. Most of the land in the southeast inhabited by the Keetoowah-Cherokees was taken away through government treaties and force of arms. In the late 1700’s and early1800’s, most of the Keetoowah-Cherokee decided to relocate to the west to avoid further deterioration of the Kituwah culture and way of life. The federal government also established the American Indian Boarding School during this period. This and other events were done as an attempt to strip the Native American of his/her identity. For example, traditional dress and speaking tribal language were prohibited. As a result, the physical, emotional, psychosocial, economic, and spiritual well-being of Native Americans were impacted.

METHOD

Theoretical Framework

Cherokee self-reliance was the theoretical basis for this study. Self-reliance is a concept within the Keetoowah-Cherokee holistic worldview where all things are believed to come together to form a whole (8). Keetoowah-Cherokee leaders have noted self-reliance to be the mainstay and way of life that influences health and helps to keep balance among the Keetoowah-Cherokee (9).

The Cherokee Self-Reliance Model was developed from findings of studies that explored the meaning of how self-reliance is conceptualized by the Keetoowah-Cherokee (10,11,12). The perspective of self-reliance endorsed by the Keetoowah-Cherokee is a composite of three categories that include: (a) being responsible, (b) being disciplined, and (c) being confident. Being responsible refers to being responsible to care for oneself and to care for others by getting assistance, respecting self, respecting others and respecting the Creator. Being disciplined refers to setting goals and pursing goals by taking the initiative to make decisions and taking risks. Being confident refers to having a sense of identity and self-worth. Knowing who one is as a Keetoowah-Cherokee relates to being proud of one’s heritage with strong values and beliefs that are consistent with Keetoowah-Cherokee values and beliefs. Two cultural themes cut across all three categories which include: (a) being true to oneself, and (b) being connected which refers to identifying and utilizing the resources within the creation.

Design

This study consisted of a three year plan using a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach guided by Stringer’s (13) three phases of participatory action research: look; think; and act. Year one (look and think phase) consisted of developing community partnerships and collecting data that informed the development of the intervention for testing in years two and three. A Community Partnership Steering Committee (CPSC) of 6 Keetoowah-Cherokee community representatives was assembled and met monthly. A Keetoowah-Cherokee tribal elder who served as the Community Liaison/Interventionist, led the monthly CPSC meetings to (a) review/revise the intervention manual attending to Cherokee language, community needs and culturally appropriate content; (b) review/select the most culturally appropriate measures for substance abuse and stress; and (c) become familiar with the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire. The instruments were pilot tested with Keetoowah-Cherokee adolescents (14). The adolescents provided recommendations and feedback which became part of the discussion with the CPSC. Additionally, as a way to build community capacity, the Community Liaison/Interventionist selected a community member to mentor who participated in the CPSC meetings and helped to conduct the group sessions in years two and three. A two-condition quasi-experimental design in which the culturally-based intervention, Cherokee Talking Circle (CTC), was compared in years two and three to standard care/standard education, Be A Winner/Drug Abuse Resistance Education (SE).

Participants who were recruited included Keetoowah-Cherokee high school students between 13-18 years of age who had been referred for substance abuse counseling and were enrolled in one of the participating high schools within the tribal jurisdictional area. Ninety-two students were recruited for the CTC condition and eighty-seven students were recruited for the SE condition with an attrition of four students who moved with their families to another school district. Parental and child consents were obtained. The eligible students had not participated in other substance use/abuse programs/interventions.

Cherokee Talking Circle Intervention (CTC)

The Cherokee Talking Circle is a 10-session manual-based intervention designed for Keetoowah-Cherokee students who were in the early stages of abusing substances and experiencing negative consequences as a result. The goal was to reduce substance abuse, with abstinence as the ideal outcome. The Keetoowah-Cherokee student participants engaged in a group led by a counselor and cultural expert that met for a 45-minute session in the format of a talking circle once a week over a 10-week period. Each participant committed to the group to be respectful by maintaining confidentiality of what was shared. The manual used both English and Cherokee languages.

Standard Substance Abuse Education (SE)

The SE condition participants were enrolled in a program entitled “Be A Winner”. This program is a revision of the “Drug Abuse Resistance Education” (D.A.R.E.) program designed as a youth substance abuse education program that promotes a school/law partnership approach to substances/drug education. It provided a police officer implementing the program with an organized curriculum and workbook to present substances/drug education within a classroom setting that occurred for 45-minute sessions. Each session occurred once a week for ten weeks.

Measurements

Pre-intervention, immediate post-intervention, and 90-day post-intervention were the three data collection points. A demographic instrument was included which asked for several routine socio-demographic variables. Also, the participants were asked if they had been involved in intervention(s) other than that offered through the study.

The CPSC participated in the selection of instruments that were most culturally acceptable and sensitive to changes in Native American adolescents. The Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire, Global Assessment of Individual Needs - Quick (GAIN-Q), and Written Stories of Stress were selected and administered at the same data collection points. The Written Stories of Stress was analyzed with Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) and has been successfully used with other substance abuse populations (15). The Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire includes 24-items rated using a Likert scale which was used to evaluate the presence of Cherokee Self-Reliance and has a test-retest reliability coefficient alpha of .84.

The GAIN-Q includes four major scales – General Life Problem Index (GLPI), Internal Behavior Scale (IBS), External Behavior Scale (EBS), and Substance Problem Scale (SPS).

The GAIN-Q has been used previously with Native American adolescent and adult substance abuse projects and produces a Total Symptom Severity Scale (TSSS), which is the sum of the four major scales, to reflect an individual’s overall health problems (16). The four major scales include the General Life Problem Index (GLPI), Internal Behavior Scale (IBS), External Behavior Scale (EBS), and Substance Problem Scale (SBS). Each major scale contains questions on recency of problems, breadth of symptoms, and recent prevalence in days or times. Studies with adults and adolescents have found good reliability in test retest situations on days of substance use and symptom counts (r=.7 to.8), as well as diagnosis (Kappa of .5 to .7). Self reports were consistent (kappa in the .5 to .8 range) with parent reports, on-site urine and saliva testing, and laboratory based EMIT and GC/MS urine testing. Additionally, self-reports were found to be consistent with a multi-method estimate for any drug (kappa=.56), cocaine (kappa=.52), opioids (kappa=.55) and marijuana (kappa=.75), with no method being superior across all drugs (16).

RESULTS

A total of 187 Cherokee students were recruited for this study. Contact with eight students was lost after the baseline measure. For the remaining 179 students, 87 were in the SE group and 92 were in the CTC group. It was randomly determined which group would receive the talking circle intervention. All subjects completed the interventions and the three measurements. The following reports the data analysis of the measurements except for the Written Stories of Stress which will be reported in other publications.

To examine whether the subjects significantly differed between the SE and CTC groups, age and gender were compared by using the t-test and chi square test, respectively. The CTC subjects with an average age of 16.53 (SD = 1.27) were not significantly different from the SE subjects with an average age of 16.37 (SD = 1.30), t = .86, p = .39. The CTC group had 33 female and 59 male subjects, while the SE group had 43 female and 44 male subjects. The Chi square test showed that the gender distribution among the two groups are not different, χ2 = 3.36, p = .07. The outcome measures were found to be sufficiently reliable. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of TSSS, GLPI (47 items), IBS (17 items), EBS (16 items), SPS (16 items), and Cherokee self-reliance (24 items) were .85, .80, 78, .73, .94, and .92, respectively.

The General Linear Model (GLM) Repeated Measures procedure in SPSS 17.0 was used to compare the outcome variables between the SE and CTC groups. Time (three data collection waves) was entered as a within-subjects variable. Group (SE vs. CTC) and gender were entered as between-subjects factors. Age was entered as a covariate. A GLM model was estimated for each of the six outcome variables. Accordingly, the Total Symptom Severity Scale (TSSS) had five, the General Life Problem Index (GLPI) had one, the Internal Behavior Scale (IBS) had four, and the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire had three missing values. Both the External Behavior Scale (EBS) and the Substance Problem Scale (SPS) had no missing values. Since missing values accounted for only a small percentage of the data, they were unlikely to bias the GLM analyses.

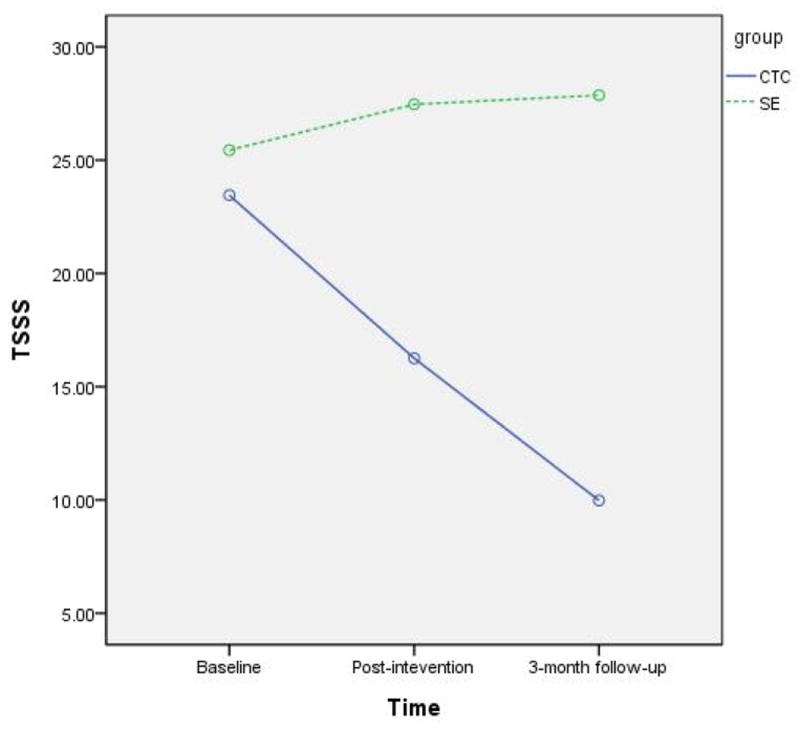

First, Total Symptom Severity Scale (TSSS) scores between the CTC and SE groups were significantly different (F = 13.14.10, p < .001) and there was also a significant interaction effect between time and group (F = 27.95, p < .001). Table 1 displays the TSSS scores between groups and across time. The comparison is further illustrated in Figure 1. At baseline, TSSS was not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups (t = -.50, p = .62). At post-intervention, the CTC group’s TSSS decreased while the SE group’s TSSS increased, and their difference became significant (t = -4.04, p < .001). At 3-month follow-up, the difference in TSSS between the CTC and the SE group was still significant (t = -5.35, p < .001) and the magnitude increased. These results suggested that as time went by, the TSSS difference between the two groups increased.

Table 1.

GAIN-Q scores across time and group

| Baseline (95% CI) | Post-intervention (95% CI) | 3-mon follow-up (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSSS | CTC | 23.53 (19.44 – 27.62) | 16.22 (12.38 – 20.07) | 10.34 (6.20 – 14.49) |

| SE | 25.36 (21.12 – 29.59) | 27.50 (23.52 – 31.48) | 27.47 (23.18 – 31.77) | |

| GLPI | CTC | 11.84 (10.00 – 13.67) | 8.99 (7.27 – 10.71) | 6.16 (4.25 – 8.07) |

| SE | 11.73 (9.84 – 13.63) | 12.43 (10.65 – 14.21) | 13.31 (11.34 – 15.29) | |

| IBS | CTC | 4.39 (3.41 – 5.37) | 2.92 (2.05 – 3.80) | 1.68 (0.78 – 2.58) |

| SE | 5.65 (4.64 – 6.65) | 5.46 (4.56 – 6.36) | 5.46 (4.53 – 6.39) | |

| EBS | CTC | 4.95 (4.09 – 5.80) | 3.39 (2.48 – 4.30) | 2.26 (1.37 – 3.15) |

| SE | 5.63 (4.75 – 6.51) | 5.76 (4.82 – 6.70) | 5.22 (4.30 – 6.13) | |

| SPS | CTC | 2.71 (1.79 – 3.62) | 1.26 (0.37 – 2.15) | 0.65 (-0.17 – 1.47) |

| SE | 2.44 (1.50 – 3.38) | 3.77 (2.86 – 4.68) | 3.46 (2.61 – 4.31) | |

| SR | CTC | 89.50 (86.14 – 92.86) | 93.07 (89.34 – 96.80) | 100.53 (97.38 – 103.68) |

| SE | 88.77 (85.25 – 92.29) | 85.61 (81.70 – 89.51) | 85.00 (81.70 – 88.30) |

Figure 1.

The comparison of TSSS scores between group and across time

Second, the CTC and SE groups were significantly different in General Life Problem Index (GLPI) scores (F = 7.83, p = .006) and there was a significant interaction effect between time and group (F = 27.99, p < .001). As revealed in Table 1, GLPI was not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups at baseline (t = .08, p = .94). The GLPI difference between the CTC and SE groups became significant at post-intervention (t = -2.63, p = .009) and 3-month follow-up (t = -5.05, p < .001). Thus, it is shown that the GLPI difference between the two groups kept increasing even after the intervention was completed.

Third, the CTC and SE groups significantly differed from each other in the Internal Behavior Scale (IBS) scores (F = 16.12, p < .001), and there was a significant time by group interaction (F = 8.77, p < .001). As Table 1 reveals, while IBS was not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups at baseline (t = -1.74, p = .08), the difference in the GLPI between the two groups became significant at post-intervention (-4.18, p < .001) and 3-month follow-up (t = -5.45, p < .001). The results indicated that the IBS difference between the two groups became more dramatic after the intervention.

Fourth, the External Behavior Scale (EBS) scores between the CTC and SE groups were significantly different (F = 12.53, p = .001), and the time-by-group interaction was also significant (F = 8.20, p < .001). As Table 1 reveals, EBS was not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups at baseline (t = -1.10, p = .27). The EBS difference between the two groups were significant at post-intervention (t = -3.58, p < .001) and 3-month follow-up, (t = -4.56, p < .001). This suggests that the EBS difference between the two groups was relatively stable over time after the intervention.

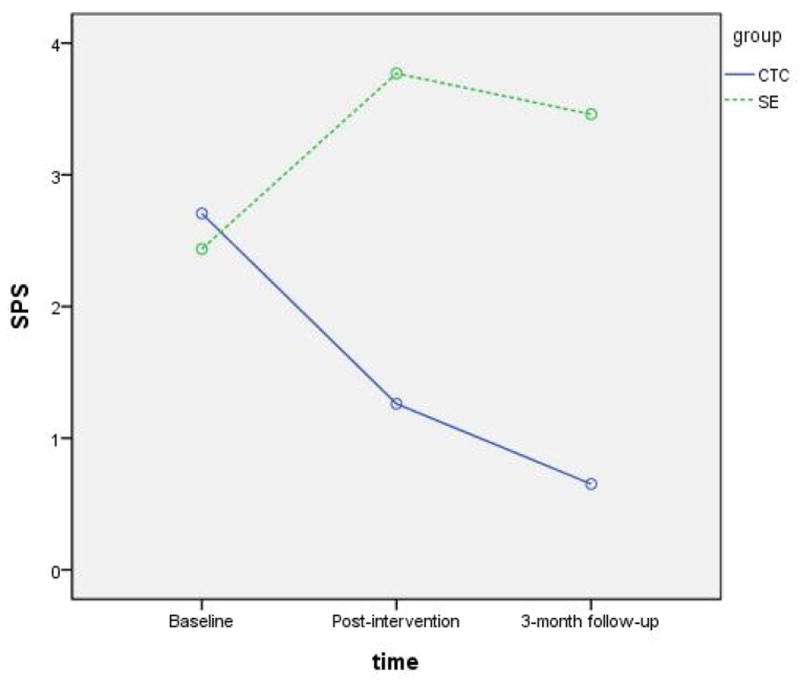

Fifth, the Substance Problem Scale (SPS) scores were significantly different between the CTC and SE groups (F = 10.38, p = .002). The within-subjects effect of time was significant between post-intervention and 3-month follow-up (F = 4.31, p = .04). There was an interaction effect between time and group (F = 14.64, p < .001). Table 1 and Figure 2 displays how the SPS scores vary between groups and across time. The SPS was not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups at baseline (t = .41, p = .69). The difference in SPS between the CTC and the SE group became significant at post-intervention (t = -3.89, p < .001) and 3-month follow-up, (t = -4.69, p = .001). The results revealed that the SPS difference between the two groups had a significant increase from baseline to post intervention and the difference kept increasing at the 3-month follow up.

Figure 2.

The comparison of SPS scores between group and across time

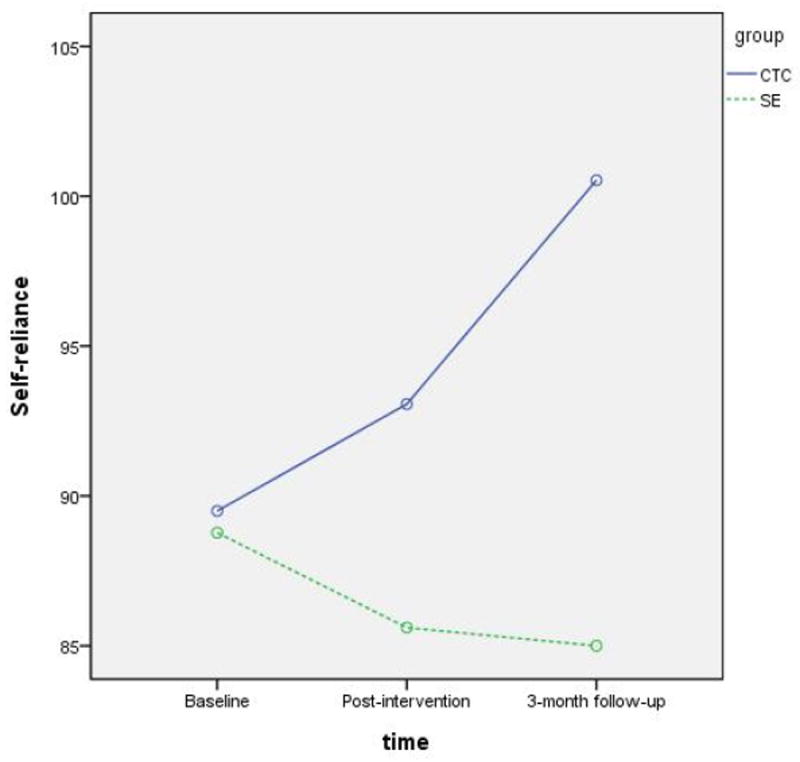

Finally, Cherokee self-reliance scores at baseline were not significantly different between the CTC and SE groups (t = .29, p = .77). At post-intervention, the CTC group had higher scores than the SE group (t = 2.72, p = .007). At 3-month follow-up, the difference between the two groups became larger (t = 6.74, p < .001). Figure 3 depicts the group changes over time. The self-reliance scores also differed by gender at 3-month so that female subjects had higher scores than male subjects (95.07 vs. 90.29, F = 5.60, p = .02).

Figure 3.

The comparison of self-reliance scores between group and across time

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provides evidence that a culturally-based intervention was significantly more effective for the reduction of substance abuse and related problems than a non-culturally based intervention for Native American adolescents. Cultural considerations may enhance the degree to which specific interventions address substance abuse problems among people from specific cultural groups (17). Substance abuse treatment programs for Native American adults are increasingly incorporating traditional Native American rituals with some non-Native American approaches (18,19). While there is recognition that culture affects substance abuse treatment, little empirical research has examined this issue, especially among Native American adolescents (20, 21). This study helps to validate that prevention and treatment from a cultural perspective is an obvious course of action against substance abuse among Native American adolescents.

The largest significant differences between the CTC and SE intervention groups for all of the four major QAIN-Q scales occurred at the 3-month post intervention follow-up. The CTC cultural based groups had significantly better results over time than the standard non-cultural based SE groups. Previous studies have demonstrated that when Keetoowah-Cherokee values are integrated into interventions, the impact on the reduction of substance abuse and related problems were greatly increased (22, 23). Other studies report findings that suggest the loss of cultural values and identity have greatly contributed to the substance abuse of Native American Indians (24, 5). The cultural values of the Keetoowah-Cherokee were integrated in this study during the talking circle group sessions. The talking circle provided an appropriate setting because it is a coming-together and a place where stories are shared in a respectful manner and in a context of complete acceptance by participants. Native Americans have long used the Circle to celebrate the sacred inter-relationship that is shared with one another and with their world (25). The values of the Cherokee self-reliance model which describes the holistic worldview, values, beliefs, and behaviors within Keetoowah-Cherokee culture were integrated into the CTC intervention. Unlike the CTC, the SE intervention utilized the “Be A Winner” educational program that promotes a school/law partnership approach to substances/drug education. It provided the officer implementing the program with an organized curriculum and workbook to present substances/drug education within a classroom setting. Keetoowah-Cherokee cultural values were not integrated in the curriculum. The significantly higher Cherokee self-reliance scores among the CTC participants reflect the impact of the use of a culturally-based intervention.

The decrease in substance abuse over time post the CTC intervention may also be explained by the holistic thinking process of Native Americans. New information is processed by Native Americans in a circular manner as compared to cultures that rely on linear thinking. The entire picture or the depth and breadth of a particular subject is perceived without breaking it down into parts. It is similar to viewing an entire landscape. Circular thought processes move from concept to concept without being linear or sequential. Information is not placed within a stepwise methodology. Life is perceived and experienced as a circular process. This is especially true concerning information about substance abuse because of its profound impact on Native Americans (26, 27). As a result, the internalization of the information and changes in thinking and behavior may not occur immediately. These may not be measureable until some time has elapsed since first receiving new information. Other studies have demonstrated that internalization and receptivity of information occurs greater if the information is delivered in accordance with Native American values (28, 29). Internalization of information for Native Americans usually occurs when cultural identity is addressed along with the information (30, 28).

Gender responses was another significant finding within the CTC groups. The adolescent Keetoowah-Cherokee females were found to show a faster response in relation to Cherokee self-reliance. Historically, Keetoowah-Cherokee culture has been a matrilineal society where females were known to be the head of the household (31). Native American women have in general been considered sacred life givers, teachers, socializers of children, healers, and warriors (32). Their status in these powerful roles have positioned them to be the informal and formal leaders which has required them to process and internalize new information at a faster rate than their male counterparts. The faster response among the Keetoowah-Cherokee female demonstrate a consistency within the cultural role of the female. This finding suggests implications for the important role the Keetoowah-Cherokee female may have when planning substance abuse and other health related interventions.

A limitation of this study lies in the generalization of the findings to other Native American tribal groups. Future research should involve the tailoring of the talking circle intervention sessions to be consistent with the cultural values of other tribes. Additionally, the Cherokee Self-Reliance model should be tailored and tested for appropriate use with other Native American tribes. Tribal leaders, school officials and health care providers can use these findings to plan and develop cultural appropriate substance abuse prevention and treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

This study was endorsed by the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians tribe and supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse R01DA021714.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Contributor Information

John Lowe, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, Florida Atlantic University.

Huigang Liang, East Carolina University.

Cheryl Riggs, Central Public Schools.

Jim Henson, Interventionist and Community Liaison.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Health Statistics. Summary health statistics for the U.S. Population: National health interview survey, 2009. 2010 Dec; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_248.pdf.

- 2.U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. American Indian/Alaska Native profile. 2011 Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=52.

- 3.Clarke A. Social and emotional distress among American Indian and Alaska Native Students. Research findings. ERIC Digest. Charleston, WV: ERIC Clearinghouse; 2002. ED459988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveheart MYH. The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schinke S, Tepavac L, Cole K. Preventing substance use among Native American youth. Three-year results. Addic Behav. 2000;25(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ODMHSAS. Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. State of the State: Children’s Behavioral Health in Oklahoma 2008 September. Retrieved April 18, 2011 from http://www.odmhsas.org/press%20releases%20new/StateofState2008.pdf.

- 7.Ehle J. Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of Cherokee Nation. New York: Doubleday; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrett JT. Meditations with the Cherokee. Rochester, VT: Bear and Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henson J. Letter of research support. Tahlequah, OK: Cherokee Nation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe J. Cherokee self-reliance. J Transcul Nur. 2002;13(4):287–295. doi: 10.1177/104365902236703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe J. The self-reliance of the Cherokee adolescent male. J Addict Nur. 2003;14:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe J. Being influenced: A Cherokee way of mentoring. J Cul Div. 2005;72(2):37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stringer ET. Action Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe J, Riggs C, Henson J, Liehr P. Cherokee Self-Reliance and Word-Use in Stories of Stress. J Cul Div. 2009;16(1):5–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slatcher RB, Pennebaker JW. How do I love thee? Let me count the words: The social effects of expressive writing. Psych Sci. 2006;7(8):660–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennis M, Scott C, Godley M, Funk R. Comparisons of Adolescents and Adults by ASAM Profile Using GAIN Data from the Drug Outcome Monitoring Study (DOMS): Preliminary Data Tables. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs D. Spirituality in education: A matter of significance for American Indian Cultures. Paths of Learning: Options for Fam & Commun. 2002;12:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novins D, Harmon C, Mitchell C, Manson S. Factors associated with the receipt of alcohol treatment services among American Indian adolescents. J Amer Acad of Child and Adol Psych. 1996;35(1):110–117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schinke S, Brounstein P, Garner S. DHS Publication No (SMA) 03-3764. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2002. Science-Based Prevention Programs and Principles. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez-Way R, Johnson S. Cultural practices in American Indian prevention programs. Juv Just. 2000;7(2):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal B. Summary Progress Report: Healing Practices. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Federation of Natives; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe J. Teen intervention project - Cherokee (TIP-C) Ped Nur. 2006;32(5):495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowe J. A Cultural Approach to Conducting HIV/AIDS and HCV Education Education Among Native American Adolescents. J Sch Nur. 2008;24:229–238. doi: 10.1177/1059840508319866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beauvais F. Trends in drug use among American Indian students and dropouts, 1975 to 1994. Amer J Pub Hlth. 1996;86(11):1594–1598. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson L. Stories, dreams, and ceremonies: Native ways of learning. Tribal Col J Amer Indian Higher Edu. 2000;17(4):26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crow K. Multiculturalism and pluralistic thought in nursing education: Native American world view and the nursing academic world view. J Nur Educ. 1993;32(5):198–204. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19930501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowe J. The Need for Historically Grounded HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Among Native Americans. J Assoc Nur in AIDS Care. 2007;18(2):15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrett M. Counseling Native Americans. In: Vacc NA, DeVaney SB, Brendal JM, editors. Counseling multicultural and diverse populations. 4. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scholl M. Native American Identity Development and Counseling Preferences: A Study of Lumbee Undergraduates. J Col Coun. 2006 Spring;9:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baruth L, Manning M. Multicultural counseling and psychotherapy: A lifespan perspective. 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perdue T. Cherokee Women. NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress coping model. Amer J Pub Hlth. 2002;92(4):520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]