Abstract

Objectives To assess the completeness of reporting of sample size determinations in unpublished research protocols and to develop guidance for research ethics committees and for statisticians advising these committees.

Design Review of original research protocols.

Study selection Unpublished research protocols for phase IIb, III, and IV randomised clinical trials of investigational medicinal products submitted to research ethics committees in the United Kingdom during 1 January to 31 December 2009.

Main outcome measures Completeness of reporting of the sample size determination, including the justification of design assumptions, and disagreement between reported and recalculated sample size.

Results 446 study protocols were reviewed. Of these, 190 (43%) justified the treatment effect and 213 (48%) justified the population variability or survival experience. Only 55 (12%) discussed the clinical importance of the treatment effect sought. Few protocols provided a reasoned explanation as to why the design assumptions were plausible for the planned study. Sensitivity analyses investigating how the sample size changed under different design assumptions were lacking; six (1%) protocols included a re-estimation of the sample size in the study design. Overall, 188 (42%) protocols reported all of the information to accurately recalculate the sample size; the assumed withdrawal or dropout rate was not given in 177 (40%) studies. Only 134 of the 446 (30%) sample size calculations could be accurately reproduced. Study size tended to be over-estimated rather than under-estimated. Studies with non-commercial sponsors justified the design assumptions used in the calculation more often than studies with commercial sponsors but less often reported all the components needed to reproduce the sample size calculation. Sample sizes for studies with non-commercial sponsors were less often reproduced.

Conclusions Most research protocols did not contain sufficient information to allow the sample size to be reproduced or the plausibility of the design assumptions to be assessed. Greater transparency in the reporting of the determination of the sample size and more focus on study design during the ethical review process would allow deficiencies to be resolved early, before the trial begins. Guidance for research ethics committees and statisticians advising these committees is needed.

Introduction

The determination of sample size is central to the design of randomised controlled trials.1 To have scientific validity a clinical study must be appropriately designed to meet clearly defined objectives.2 3 Clinical trials should provide precise estimates of treatment effects, thus allowing healthcare professionals to make informed decisions based on sound evidence.3 Equally, trials should not be too large, as these may expose some patients to unnecessary risks. An extensive literature on sample size calculations in clinical research now exists for a wide variety of data types and statistical tests.4 5 6 7 8 9 The International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use, topic E9, sets down the requirements for sample size reporting in research protocols for studies supporting the registration of drugs for use in humans.1 Although these standards primarily concern commercial sponsors, the principles (box 1) have broad application to all clinical trials. The consolidated standards of reporting trials statement provides similar guidance for published randomised trials.10 11

Box 1: Core components of the sample size determination (International Conference on Harmonisation topic E9)1

Trial objective

For example, superiority, non-inferiority, equivalence

Study design

For example, parallel group, crossover, factorial

Primary variables

Clinically most relevant endpoints from the patients’ perspective

Statistical test procedure

For example, t test for continuous variables, χ2 test for binary variables

Allocation ratio

Ratio of number of participants in each treatment arm

Treatment difference sought

Minimal effect that has clinical relevance or the anticipated effect of the new treatment, where this is larger

Other design assumptions

For example, variance, response rates, and event rates, used in the calculation

Type I error

Probability of erroneously rejecting the null hypothesis

Type II error

Probability of erroneously failing to reject the alternative hypothesis:

Expected rate of treatment withdrawals

Expected proportion of subjects with no post-randomisation information

Key considerations

Justification of treatment difference sought and other design assumptions

Investigation of how sample size changes under different assumptions (sensitivity analyses)

Other components depending on study design

Accrual and total study duration used to estimate the number of patients required in event driven studies

Adjustments for multiple testing—for example, multiple endpoints, multiple checks during interim monitoring

Surprisingly few evaluations have been made of the quality of the sample size determination in randomised controlled trials. Those that have been performed are mainly based on published data owing to the difficulty in obtaining access to unpublished research protocols.12 13 These reviews have several limitations. Firstly, the reporting of the sample size determination in the study publication is less detailed than in the research protocol. Secondly, they are affected by publication bias. Thirdly, one study showed that there are often discrepancies between the research protocol and the publication.14 Consequently, definitive conclusions about the quality of sample size determinations should be based on a review of original research protocols.

Studies that are too large or too small have been branded as unethical.2 15 16 The view that underpowered studies are in themselves unethical has been challenged by some researchers, who argue that this is too simplistic.17 18 19 We believe that a study must be judged on whether it is appropriately designed to answer the research question posed, and the validity of the sample size calculation is germane to this assessment. This is not merely a matter of whether the sample size can be recalculated, since the calculation can be correct mathematically but still be of poor quality if the assumptions used have not been suitably researched and qualified.20 Greater transparency in the reporting of the sample size determination and more focus on study design during the ethical review process would allow deficiencies to be resolved early, before the trial begins; once the trial starts it is too late. We assessed the quality of sample size determinations reported in research protocols with the aim of developing guidance for research ethics committees.

Methods

We searched the research ethics database, a web based database application for managing the administration of the ethical review process in the United Kingdom, using filter criteria (see supplementary file) to identify all validated applications for randomised (phase IIb, III, and IV) clinical trials of investigational medicinal products submitted to the National Research Ethics Service for ethical review during 2009. We designed these criteria to create a large database of recently submitted protocols (2009 was the last complete year before the project started in 2010) for randomised controlled trials.

Creation of the protocol database

Three researchers extracted the characteristics of the studies (table 1) from the research ethics database according to prespecified rules and entered the data into the protocol database. Two reviewers independently assessed each research protocol. The researchers met regularly to discuss and agree on the final data to be entered into the database.

Table 1.

Study characteristics entered into research protocol database

| Study identifier or research ethics committee reference number |

| Commercial or non-commercial sponsor |

| Therapeutic area and disease category |

| Standard drug treatments for medical condition. Was there an accepted “standard treatment” for the medical condition at the time the study was being designed? |

| Clinical phase: IIb, III, or IV |

| Primary outcome variables |

| Form of primary outcome variables (continuous, binary, time to event) and test procedure |

| Objectively assessed outcome—that is, one that is not influenced by investigators’ judgment (for example, all cause mortality and recognised laboratory variables)21 |

| Study blinding such as open label, partial blind, or double-blind |

| Comparators such as placebo and active-control |

| Study design, such as parallel group, crossover, group sequential |

| Study objective: superiority, non-inferiority, or therapeutic equivalence |

| Allocation ratio |

| Treatment difference sought (or margin). Data on which assumption was based; why plausible for planned study |

| Clinical importance of the treatment difference discussed |

| Standard deviation of treatment difference (or margin) or hazard rates, median survival, event rate, or responder rate in each study arm. Data on which assumption was based; why plausible for the planned study |

| Type I error: one sided or two sided test |

| Type II error (power of a trial is 1−probability of a type II error) |

| Sample size: evaluable number of patients required for analysis or in the case of an event driven study, the number of events. The evaluable number of patients required for analysis (obtained from the sample size calculation before adjusting for withdrawals). If only the total number of subjects to be enrolled was reported then the number of evaluable patients was calculated using the assumed withdrawal rate. If the research protocol only reported one value for the sample size with no information on assumed withdrawals then this figure was entered into the database |

| Withdrawal or dropout rate |

| Interim analysis and strategy to control type I error |

| Multiple comparisons and strategy to control type I error |

| Additional information: additional variables needed to perform sample size calculations for specific statistical tests—for example, analysis of covariance, negative binomial model, non-parametric tests; and sensitivity analyses |

To verify the data sources we checked that the information in the research ethics database was consistent with the research protocol on file at the research ethics committee office.

Data analysis

The database was analysed using SPSS Version 19. We describe the results using frequency tables with percentages, cross tabulations, relative risks with 95% confidence interval, and box and Bland-Altman plots.

Assessing the sample size determination

We assessed sample size determination based on three factors: the reporting of how the sample size was determined, the reporting of and justification for the design assumptions, and recalculation of the original sample size determination.

Reporting of sample size determination

We reviewed each protocol to determine the presence or absence of the core sample size components. Reporting of additional information such as adjustment for multiple testing (for example, multiple endpoints, multiple checks during interim monitoring) required for the sample size calculation was also documented. We did not assess the appropriateness of the proposed methods of analysis.

Reporting and justifying design assumptions

Each design assumption was categorised (box 2). We also documented the reporting of sensitivity analyses and consideration of an adaptive design. We did not independently assess the appropriateness of the design assumptions.

Box 2: Categorisation of design assumptions

Variable with no justification

Variable and data on which assumption based (the “basis”)

Details of the data underpinning the variable—for example, previous studies with the new drug or products in the same therapeutic class, physician survey, meta-analysis, literature search given

Treatment difference and data on which assumption based and discussion of its clinical importance

Required more than a simple statement that the “treatment difference was clinically important”. Reference to a specific study or studies in which the clinically relevant difference has been determined, or a detailed clinical discussion of why the investigators considered the difference sought to be meaningful

Variable and data on which assumption based and a reasoned explanation for choice

Required a discussion of the data underpinning the variable and an explanation why the value used in the sample size calculation was plausible for the planned study

Recalculation of original sample size determination

The three researchers who created the protocol database recalculated the original sample size according to prespecified rules. Two independent reviewers carried out each recalculation; the researchers met regularly to discuss and agree the final data to be entered into the database. Any outstanding questions were referred to a fourth reviewer for resolution (n=65).

If the sample size determination stated that a specific statistical software had been used (for example, nQuery Advisor, East, PASS) or referenced a specific publication, then we used the same software or published methodology to recalculate the sample size. If the protocol stated that the sample size was based on a more complex method of analysis, such as analysis of covariance then we used PASS 11 or nQuery 6.01. Otherwise we used standard formulas for normal, binary, or survival data.4 5 6

Missing information was imputed in four ways. Firstly, if the withdrawal rate was not specified we recalculated the sample size using the variables given. This recalculated sample size was then compared with the sample size reported in the protocol. Secondly, if the type I error or type II error (power of a trial is 1−probability of a type II error) was not specified, we recalculated the sample size using a two sided 5% type I error or a 20% type II error. Thirdly, when adjustments for multiple testing were not reported we assumed no adjustment had been applied. Finally, if the sample size was based on a more complex method of analysis, but insufficient information was reported to allow the sample size to be recalculated for the planned method, we used standard formulas to recalculate the sample size.

We defined two populations for analysis: protocols where missing information was imputed and protocols that reported all core components and any additional information such as adjustments for multiple testing required to accurately recalculate the sample size (complete reporting).

If the ratio of the number of evaluable patients or events reported in the protocol to that calculated fell within the range 0.95 to 1.05, then we reproduced the sample size, since a difference of 5% or less either way represented an inconsequential reduction or increase in power (approximately 2% for normal, binary, or survival data).

Results

A total of 929 research protocols were identified by the initial search. Of these, 446 met the inclusion criteria (see supplementary figure 5). Table 2 lists the main characteristics of the 446 research protocols (also see supplementary table 5). The most common therapeutic areas were oncology (94; 21%) and endocrinology (49; 11%). Most studies were sponsored by industry (314; 70%), were in phase III (251; 56%), had a parallel group design (319; 72%), and had superiority of the test over control medicinal product as the primary objective (375; 84%). Six (1%) protocols included sample size re-estimation in the study design.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the 446 research protocols

| Study characteristics | No (%) of protocols (n=446) |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic area: | |

| Oncology | 94 (21) |

| Endocrinology | 49 (11) |

| Infectious disease | 38 (9) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 36 (8) |

| Central nervous system | 35 (8) |

| Respiratory system | 34 (8) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 34 (8) |

| Pain and anaesthesia | 27 (6) |

| Other therapeutic areas (each <5%) | 99 (22) |

| Commercial status: | |

| Commercial | 314 (70) |

| Non-commercial | 132 (30) |

| Clinical phase: | |

| Phase IIb | 102 (23) |

| Phase II/III | 5 (1) |

| Phase III | 251 (56) |

| Phase IV | 88 (20) |

| Trial design: | |

| Parallel group | 319 (72) |

| Group sequential | 88 (20) |

| Crossover | 18 (4) |

| Factorial | 13 (3) |

| Adaptive | 6 (1) |

| Withdrawal | 2 (0.5) |

| Test hypothesis: | |

| Superiority | 375 (84) |

| Non-inferiority and equivalence | 58 (13) |

| Superiority and non-inferiority | 11 (2) |

| Not stated | 2 (0.4) |

Reporting of sample size components

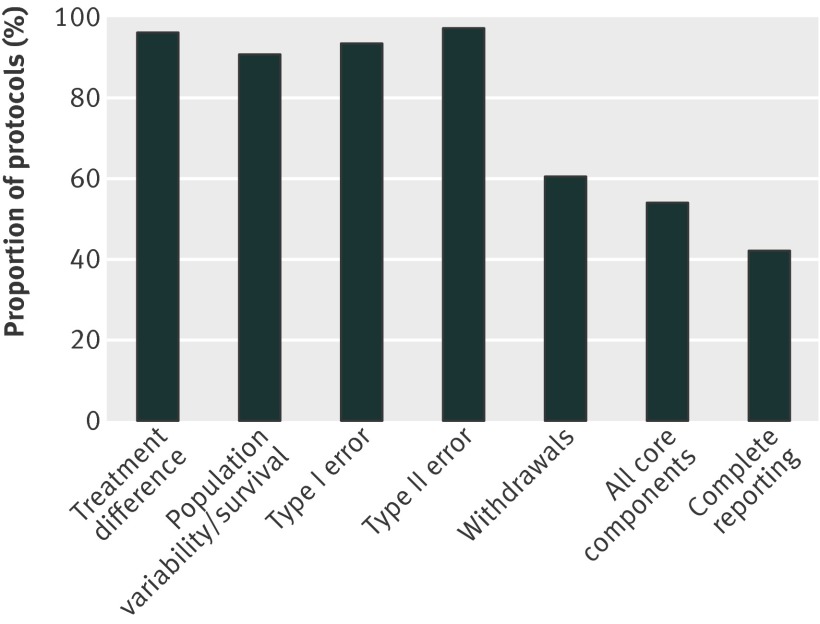

The individual core components of the sample size were generally reported in the 446 protocols, with the exception of withdrawals (269; 60%, fig 1) (also see supplementary table 6). Of the 446 protocols, 240 (54%) reported all the core components; withdrawal rate was the only element missing in 143 out of 206 (69%) protocols that did not report all core components.

Fig 1 Reporting of core sample size components

When we considered protocols that reported all core components and additional information such as adjustments for multiple testing to accurately recalculate the sample size (complete reporting) then the number reduced to 188 protocols (42%).

Reporting design assumptions

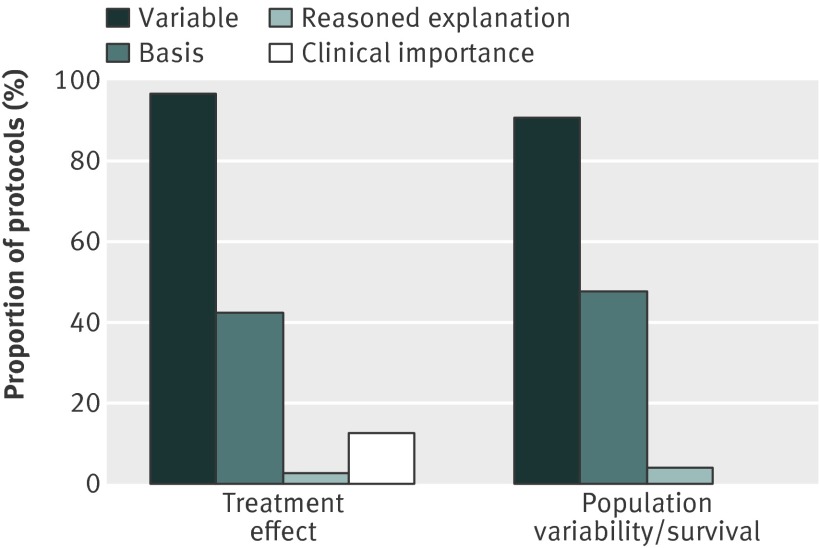

Less than half of the 446 protocols (190; 43%) reported the data on which the treatment difference (or margin) was based. Of the 190 protocols that did report the basis of the treatment difference, 92 (48%) cited previous studies with the product or a product in the same class and 38 (20%) cited a literature search (fig 2 and supplementary table 7). In only four (2%) protocols was the estimated treatment difference based on a meta-analysis. Reporting the basis for the treatment difference was lowest in studies on oncology (28/94; 30%) and cardiovascular disease (12/36; 33%) and highest in those on pain and anaesthesia (16/27; 59%) (see supplementary table 8).

Fig 2 Reporting the design assumptions

Overall, 55 out of 446 (12%) protocols reported both the basis of the treatment effect and its clinical importance, 135 (30%) protocols reported the basis only, and 256 (57%) reported neither. Limited information on the nature of the data underpinning the treatment effect was usually given, and just 13 (3%) protocols gave a reasoned explanation why the value chosen was plausible for the planned study.

The same pattern was observed with population variability or survival, with less than half (213/446; 48%) of the protocols reporting the basis of the variable used in the calculation (fig 2 and supplementary table 9). Previous studies, a literature search, or both, were again most commonly cited. The variability or survival estimate was based on a meta-analysis in only two of the 213 (1%) protocols. Again, limited information was usually given, and just 17 (4%) protocols explained the plausibility of the value chosen.

Only 11 out of the 446 (3%) protocols reported analyses investigating the sensitivity of the sample size to deviations from the assumptions used in the calculation.

Reporting of strategies to control type I (false positive) and type II (false negative) error

Adjustments for multiple comparisons (81/144; 56%) or interim analyses (56/95; 59%) were reported in just over half of the research protocols with these design features (see supplementary table 10). The potential for increasing the type II error was not considered in any study with multiple comparisons. If all co-primary variables must be significant to declare success then the type II error rate can be inflated, resulting in reduction in the overall study power.1 22

Recalculation of the original sample size determination

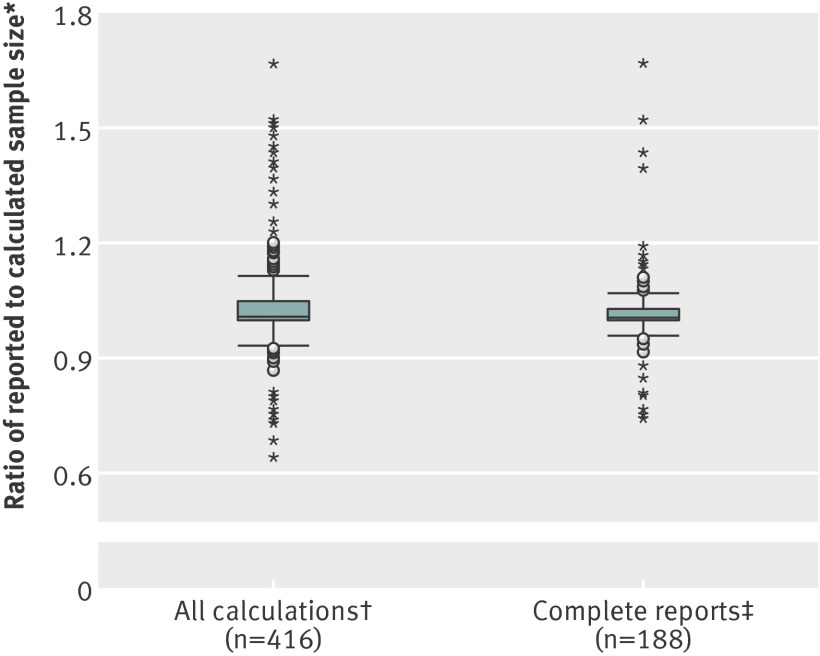

If all protocols were considered using the rules for imputing missing information then 262 of out 446 (59%) sample size determinations could be reproduced, with 51 (11%) under-estimated and 103 (23%) over-estimated. Thirty (7%) of the original sample size calculations could not be recalculated (see supplementary table 11). Figure 3 shows a box plot of the relative differences between the reported and recalculated sample sizes.

Fig 3 Difference between reported and calculated sample size. *Ratio of number of evaluable patients or events reported in protocol to that calculated. †All calculations (n=416) with missing data imputed. Observations below 2.5th (0.61) or above the 97.5th (1.74) centile are excluded. Minimum and maximum values (not shown) observed were 0.12 and 5.21, respectively. ‡Complete reporting (n=188): no data imputation. Minimum and maximum values (not shown) observed were 0.32 and 2.45, respectively. Central boxes span 25th (1.00 for both plots) and 75th (1.05 and 1.03, respectively) centiles, the interquartile range. Horizontal line within box represents median (1.01 in both plots)

A total of 134 of the 188 (71%) sample size calculations from protocols with complete reporting could be reproduced, with 20 (11%) under-estimated and 34 (18%) over-estimated, respectively. The reproducibility of the sample size increased with more comprehensive reporting, primarily withdrawal rates and adjustments for multiple testing. None the less, both analyses showed a tendency for over-estimation, and in total only 134 of the 446 (30%) original sample size calculations could be accurately reproduced.

Supplementary figure 6 shows a Bland-Altman plot comparing reported and calculated sample sizes.

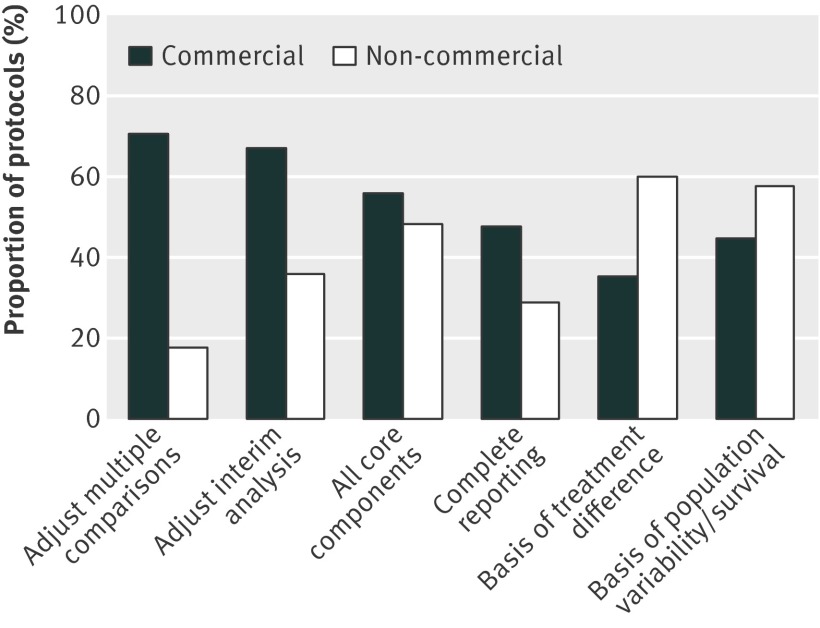

Commercial versus non-commercial sponsors

The reporting of the core components of the sample size determination did not differ noticeably between studies with commercial and non-commercial sponsors (fig 4 and supplementary table 12). Studies with non-commercial sponsors were more likely than those with commercial sponsors to report the basis for design assumptions (relative risk 1.69, 95% confidence interval 1.38 to 2.08 for treatment difference and 1.29, 1.07 to 1.56 for variance and survival). Conversely, studies with non-commercial sponsors were less likely than those with commercial sponsors to report adjustments for multiple comparisons (0.26, 0.13 to 0.50) and interim analyses (0.54, 0.31 to 0.93) and provide complete reporting (0.60, 0.45 to 0.81); the sample size calculation from protocols of studies with non-commercial sponsors was also less likely to be reproduced (0.72, 0.59 to 0.88).

Fig 4 Reporting by commercial status

Discussion

Our review suggests that the reporting of the sample size determination in the research protocol often lacks essential information. Treatment difference and type I error were usually given, but withdrawal rates and adjustments for multiple testing were often missing. Only 188 of 446 (42%) protocols contained sufficient information to accurately recalculate the sample size. More than half of the research protocols provided no justification for the assumptions used in the sample size calculation. When a justification was given, it generally lacked detail. Sensitivity analyses, which can help investigators understand the reliability of the variables used in the sample size calculation and whether sample size re-estimation should be included in the study design, were rarely reported.23 24 25

Imputing missing information resulted in 262 out of 446 (59%) reproduced sample sizes. This increased to 134 out of 188 (71%) when only complete reports were considered. Overall, only 134 of the 446 (30%) sample size calculations could be accurately reproduced. Study size tended to be over-estimated rather than under-estimated.

Our research, the first extensive review of unpublished research protocols, raises several problems with the statistical planning of randomised controlled trials, in particular the limited consideration afforded to the choice of design assumptions. Sample size determinations are highly sensitive to changes in design assumptions, which behoves sponsors to be rigorous when estimating these variables.26 Moreover, if the degree of uncertainty is high then design assumptions should be checked during the course of the trial.26

Limitations of this review

We only reviewed the research protocol submitted to the research ethics committee and had no access to any other documents. Moreover, our review was completely independent of the ethical review process. The protocols were submitted in 2009 to the UK National Research Ethics Service and reflect clinical research practice at that time. None the less, the sample is relatively recent and many sponsors planned to include sites both within and outside the United Kingdom, so we believe our findings can be generalised to other countries and regions for commercial studies where global regulatory requirements exist. For non-commercial studies, the quality of reporting depends on the investigators experience. We did not verify the appropriateness of the design assumptions used in the sample size determination in this research project.

Implications of the findings

In many instances the validity of the sample size determination and by extension the scientific validity of the study—one of the main aspects of the ethical review process—could not be judged.2 The available evidence suggests that key sample size assumptions are not determined in a rigorous manner. This may explain why large differences have been observed between design assumptions and observed data.13 27 Furthermore, sample sizes tended to be over-estimated, which is a concern given the challenges of recruiting to randomised controlled trials.28 Finally, methodologies to check assumptions and re-estimate sample size during the study are often not applied, despite the fact that these methods are encouraged by regulatory authorities.29 30

Investigators should be rigorous in the determination of design assumptions. There is no “one size fits all” approach. Sufficient information should be reported to allow the sample size to be reproduced and show that there is solid reasoning behind the assumptions used in the calculation (box 3).

Box 3: Recommended information to be reported in research protocols

All components necessary to reproduce the sample size, in particular withdrawal or dropout rate and adjustments for multiple comparisons or interim analyses

Confidence interval for variables used in the calculation

A concise summary of the data from which variable estimates are derived. If the variable is based on previous studies then give details of the study design, clinical phase, study population, relevant outcome measures, relevant results, and study size, ideally in a table

Discussion of the clinical importance of the treatment effect

-

A reasoned explanation of why the treatment difference and other design assumptions are plausible for the planned study, taking into account:

All existing data, for example, previous clinical studies, relevant clinical pharmacology (dose effect relation, etc) and non-clinical data

How any differences between the previous studies and the one planned impact on the design assumptions

How robust the sample size and/or statistical power is to different assumptions (sensitivity analysis). If the variable estimates are considered unreliable then re-estimation of the sample size could be considered

We would also ask the suppliers of software used to calculate sample size to consider including the withdrawal and dropout rate in the package to ensure that this is taken into account and reported in the research protocol.

A poorly designed trial cannot be saved once it is completed. Greater transparency in the reporting of sample size determinations in research protocols would facilitate the early detection of deficiencies in the study design. Moreover, better justification of the design assumptions in the research protocol would facilitate the overall ethical review process.31

Despite calls for a different approach to sample size determination, we believe that there is no substitute for spending time designing the study and giving due consideration to the risks and how these can be tackled.13 32

Wherever the responsibility for scientific and statistical review lies, we believe clear guidance on the sample size determination should be provided and followed. Individuals with appropriate statistical expertise should also play a central role in the ethical review of research protocols.33 Improving the review process to place more focus on study design was the aim of the National Research Ethics Service at the start of this project and we propose to use the results of our research to develop guidance, working with the ethics service and others interested in this area.

What is already known on this topic

Sample size determination is an accepted and important part of the planning process for randomised controlled trials

Sample size reporting in publications is often lacking essential information

What this study adds

Sample size reporting in original research protocols is often incomplete and in many instances the reliability of the design assumptions and hence the validity of the sample size determination cannot be judged

The ethical review process should place greater focus on study design

Withdrawal and dropout rate are frequently not reported and therefore suppliers of sample size software could include this variable in the package to improve reporting

We thank the National Research Ethics Service for its support; IBE research assistants Mathias Heibeck and Linda Hayanga for their contribution to this project; and Michael Campbell, Sir Iain Chalmers, Douglas Altman, Gary Collins, and Hugh Davies for their comments on this work.

Contributors: UM had full access to all of the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. He is guarantor. TC and UM conceived and designed the study. TC, Mathias Heibeck, and Linda Hayanga collected the data. TC and UB carried out the statistical analyses. TC, Mathias Heibeck, Linda Hayanga, and UM recalculated the sample sizes. TC, UM, and UB interpreted the data. TC drafted the manuscript. UM and UB critically reviewed the manuscript. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Research Ethics Service, which became a part of the Health Research Authority in December 2011.

Funding: This study received no funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that: TC received support for travel from the National Research Ethics Service and has worked as a consultant for the clinical research organisation ICON in the previous three years; they have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f1135

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Filter criteria used to identify studies in research ethics database

Additional figures and tables

References

- 1.ICH harmonised tripartite guideline. Statistical principles for clinical trials E9. Current Step 4 version dated 5 February 1998.

- 2.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA 2000;283:2701-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victor N. Prüfung der wissenschaftlichen Qualität und biometriespezifischer Anforderungen durch die Ethikkommissionen? Medizinrecht 1999;9:408-12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julious SA. Sample sizes for clinical trials. Chapman and Hall, 2009.

- 5.Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Sample size calculations in clinical research. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2003.

- 6.Machin D, Campbell M, Tan SB, Tan SH. Sample size tables for clinical studies, 3rd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- 7.Julious SA. Tutorial in biostatistics: sample sizes for clinical trials with normal data. Stat Med 2004;23:1921-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Julious SA, Campbell MJ, Altman DG. Estimating sample sizes for continuous, binary and ordinal outcomes in paired comparisons: practical hints. J Biopharm Stat 1999;9:241-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell MJ, Julious SA, Altman DG. Estimating sample sizes for binary, ordered categorical, and continuous outcomes in two group comparisons. BMJ 1995;311:1145-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:663-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan AW, Upshur R, Singh JA, Ghersi D, Chapuis F, Altman DG. Research protocols: waiving confidentiality for the greater good. BMJ 2006;332:1086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles P, Giraudeau B, Dechartres A, Baron G, Ravaud P. Reporting of sample size calculation in randomised controlled trials: review. BMJ 2009;338:b1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PE, Altman DG. Discrepancies in sample size calculations and data analyses reported in randomised trials: comparison of publications with protocols. BMJ 2008;337:a2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG. Statistics and ethics in medical research III: how large a sample? BMJ 1980;281:1336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halpern SD, Karlawish JHT, Berlin JA. The continuing unethical conduct of underpowered clinical trials. JAMA 2002;288:358-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Sample size calculations in randomised trials: mandatory and mystical. Lancet 2005;365:1348-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacchetti P, Wolf LE, Segal MR, McCulloch CE. Ethics and sample size. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:105-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalmers I. Cardiotocography v Doppler auscultation: all unbiased comparative studies should be published. BMJ 2002;324:483-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, Witte S, Krämer J, Maier C, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Juni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Julious SA, McIntyre NE. Sample sizes for trials involving multiple correlated must-win comparisons. Pharm Stat 2012;11:177-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senn SJ. Statistical issues in drug development. Wiley, 2007:198-9.

- 24.Bacchetti P. Current sample size conventions: flaws, harms, and alternatives. BMC Med 2010;8:17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kieser M, Wassmer G. On the use of the upper confidence limit for the variance from a pilot sample for sample size determination. Biom J 1996;38:941-9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julious SA. Designing clinical trials with uncertain estimates of variability. J Pharm Stat 2004;3:261-8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Magazin A, Schroen A, Soares H, Hozo I, et al. Optimism bias leads to inconclusive results—an empirical study. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:583-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, Entwistle VA, Grant AM, Cook JA, et. al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 2006;7:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA draft guidance for industry, adaptive design clinical trials for drugs and biologics. FDA, Feb 2010.

- 30.Kieser M, Friede T. Simple procedures for blinded sample size adjustment that do not affect the type I error rate. Stat Med 2003;22:3571-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savulescu J, Chalmers I, Blunt J. Are research ethics committees behaving unethically? Some suggestions for improving performance and accountability. BMJ 1996;313:1390-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norman G, Monteiro S, Salama S. Sample size calculations: should the emperor’s clothes be off the peg or made to measure? BMJ 2012;345:e5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williamson P, Hutton JL, Bliss J, Blunt J, Campbell MJ, Nicholson R. Statistical review by research ethics committees. J R Stat Soc Ser A 2000;163:5-13. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Filter criteria used to identify studies in research ethics database

Additional figures and tables