Abstract

Delirium (acute confusion) complicates 15% to 50% of major operations in older adults and is associated with other major postoperative complications, prolonged length of stay, poor functional recovery, institutionalization, dementia, and death. Importantly, delirium may be predictable and preventable through proactive intervention. Yet clinicians fail to recognize and address postoperative delirium in up to 80% of cases. Using the case of Ms R, a 76-year-old woman who developed delirium first after colectomy with complications and again after routine surgery, the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of delirium in the postoperative setting is reviewed. The risk of postoperative delirium can be quantified by the sum of predisposing and precipitating factors. Successful strategies for prevention and treatment of delirium include proactive multifactorial intervention targeted to reversible risk factors, limiting use of sedating medications (especially benzodiazepines), effective management of postoperative pain, and, perhaps, judicious use of antipsychotics.

Dr Delbanco: Ms R is a 76-year-old woman who experienced delirium following complicated surgery for removal of a polyp of the colon. A self-employed, active therapist, she lives alone with children nearby. She has no family history of dementia. She does not smoke and does not abuse alcohol or other substances. She has Medicare and supplemental insurance. For many years, Ms R received care at a hospital-based primary care unit.

Her medical history includes depression, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, irritable bowel syndrome, and gastrointestinal bleeding due to diverticulosis. She took only vitamins and prophylactic aspirin. She has had long-standing, low-grade anemia, with hemoglobin levels of about 11 g/dL, along with multiple normal creatinine, electrolyte, calcium, and glucose measurements. She received a hip replacement in 2008 for degenerative osteoarthritis, a procedure that was uneventful and was not associated with delirium.

In early 2010, a polyp measuring approximately 3.5 cm was found in Ms R’s sigmoid colon during a screening colonoscopy. In a “difficult” and extensive transabdominal procedure complicated by the presence of extensive diverticula, the polyp was removed by anterior colectomy. She did well immediately postoperatively, with some pain but no sign of confusion noted by the clinicians or her family. Three days after surgery, Ms R developed acute confusion, followed by high fever and hypotension. She was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where she was treated with fluids and antibiotics. Workup revealed an anastomotic leak requiring diverting loop ileostomy. She never required intubation, sedation, or pressors but developed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation requiring cardioversion. Her confusion persisted throughout her 4-day ICU stay, and psychiatric evaluation led to a diagnosis of delirium, which cleared slowly as her medical condition stabilized. She went to a skilled nursing facility and then home, where no further delirium was noted.

Three months after her initial surgery, Ms R returned to the hospital to have her ileostomy closed. Despite uneventful surgery and an otherwise routine postoperative course, she developed delirium immediately postoperatively and in the following days appeared both confused and depressed. She was hospitalized for major depression, which was treated with quetiapine and citalopram. Toward the end of that stay she fell, fractured her sacrum, and was managed without surgical intervention. She required several weeks of care in a skilled nursing facility.

Four months after discharge, Ms R returned to her profession as a therapist, living alone and driving her car. Her only medications were aspirin and vitamins. At the time of the interview, there was no evidence of thought disorder. She appeared well and denied any symptoms of confusion or depression.

MS R: HER VIEW

I remember nothing about the admissions. I do remember, strangely enough, the rooms and the beds and some of the staff who were surrounding my care during that time.

Now, 4 months later, I have resumed my practice of psychotherapy almost up to the full amount as before. I drive, I feel optimistic, and I’m enjoying my friends and relatives. I think that I could say I’m neither depressed nor in any kind of physical or emotional pain. I would certainly not refuse to have an operation that was necessary to save my life, nor can I imagine undergoing, under any circumstances, elective surgery with a light heart. I would hire an expert in delirium with the hope that that person might have some way of intervening early to avoid this from happening.

MS R’S DAUGHTER: HER VIEW

My mother was very confused and would repeat herself many times about what the plan was. She would contradict herself, really just wanting to get home. I just remembered my mother after that last surgery really losing a sense of reality and just mixing up names and times during our conversations. It was also very difficult trying to set up her discharge plan. During this time, I was feeling very hopeless about her future; it was very scary for the family to see this happen. We didn’t know what to do and we were confused about what was happening to her. It wasn’t like her; her baseline was just gone. I reached out to the surgeons through our primary care. I called a lot of people about her confusion too.

I think the staff was pretty confused about how to continue my mother’s care, and as the family, we had to do much advocacy. It was frustrating, and at times I felt angry, but I think they were just as confused as she was on some level. I kept screaming at them, “She hasn’t really healed!” and they would say, “No? Well, her body is fine,” and I’d say, “She’s not fine.” I felt with the surgical team that she was opened up and then sewed back up and she physically healed, but mentally she was nowhere near.

AT THE CROSSROADS: QUESTIONS FOR DR MARCANTONIO

What is postoperative delirium? How common is it? What is its impact on surgical outcomes? How often is postoperative delirium recognized? How is it assessed and diagnosed? Can a patient’s risk of delirium be defined before surgery? Can postoperative delirium be prevented? What are the appropriate evaluation, management, and long-term follow-up for postoperative delirium? What steps can be taken to reduce the risk of recurrence? What do you recommend for Ms R?

Dr Marcantonio: Ms R is a 76-year-old woman who, despite having several medical conditions, was totally independent and actively practiced psychotherapy prior to surgery. Her course is notable for 2 distinct episodes of postoperative delirium. The first episode, following her low anterior sigmoid colectomy, developed on postoperative day 3 and subsequently led to diagnosis of an anastomotic leak requiring emergency loop ileostomy. The second episode occurred 3 months later when she underwent closure of this ileostomy. This time the delirium developed immediately postoperatively and there were no other complications. In both instances, the delirium took several weeks to clear, and the second episode was further complicated by severe depression requiring psychiatric hospitalization.

POSTOPERATIVE DELIRIUM

Delirium is an acute confusional state characterized by inattention, abnormal level of consciousness, thought disorganization, and a fluctuating course.1,2 These diagnostic criteria, found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition)3 and in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision,4 help to distinguish delirium from dementia. Any delirium that occurs after surgery may be called “postoperative delirium,” but as Ms R’s first episode of delirium illustrates, not all such instances are directly attributable to surgery or anesthesia.

Incidence and Persistence of Postoperative Delirium

The incidence of postoperative delirium varies significantly depending on the patient’s age and preoperative status, whether the surgery is elective vs emergent, the type of surgery, and the development of postoperative complications.5 In general, older patients undergoing emergency surgery or long, complicated surgical procedures tend to have a higher frequency of delirium. eTable 1 (available at http://www.jama.com) summarizes the incidence of delirium in several major surgical populations.6–19

At least 2 of 3 cases of delirium develop in the first 2 postoperative days, with the peak incidence on postoperative day 1 and the peak prevalence on postoperative day 2.7 Later-onset delirium is often associated with either a major postoperative complication or withdrawal from alcohol or sedatives. As an example, Ms R developed delirium on postoperative day 3 shortly before she developed sepsis due to her anastomotic leak.

The duration of delirium also has a bimodal distribution. Approximately half the episodes resolve within 2 days of onset, while nearly one-third persist until hospital discharge.7,10 Among patients discharged from the hospital, delirium can be slow to clear, with up to 50% still showing signs of delirium a month later.20,21

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is used to describe longer-term cognitive deficits that occur after surgery,5 often measured by serial performance on a neurocognitive battery.22 Very few studies have used state-of-the-art methods to measure both delirium and POCD, so whether these 2 entities are related remains uncertain. A POCD-like syndrome has also been described in ICU and severe sepsis survivors.23–25

Delirium and Surgical Outcomes

Delirium is strongly associated with poor surgical outcomes. In the hospital, postoperative delirium is associated with a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of major postoperative complications, including an increased risk of death.7,16,17 Patients who develop delirium stay in the hospital 2 to 5 days longer than similar patients without delirium and have a 3-fold increased risk of requiring institutional placement at discharge.6,7,14–16 Delirium is associated with $60 000 of incremental costs over the following year. These costs accrue both during the hospitalization and after discharge.26,27

A recent meta-analysis that included both medical and surgical patients showed that in the long term, delirium was associated with increased mortality for up to 2 years, institutionalization for up to 14 months, and new dementia for up to 4 years.28 Separate studies have demonstrated an association of delirium with poor functional recovery after surgery for up to 6 months.6,10,29 The specific role of delirium in the etiology of these poor outcomes remains controversial. It is possible that delirium contributes directly or that its development may define a state of vulnerability. It is likely that both scenarios are true, and further research is necessary to determine whether prevention and treatment of delirium leads to improved outcomes.

Pathophysiology of Postoperative Delirium

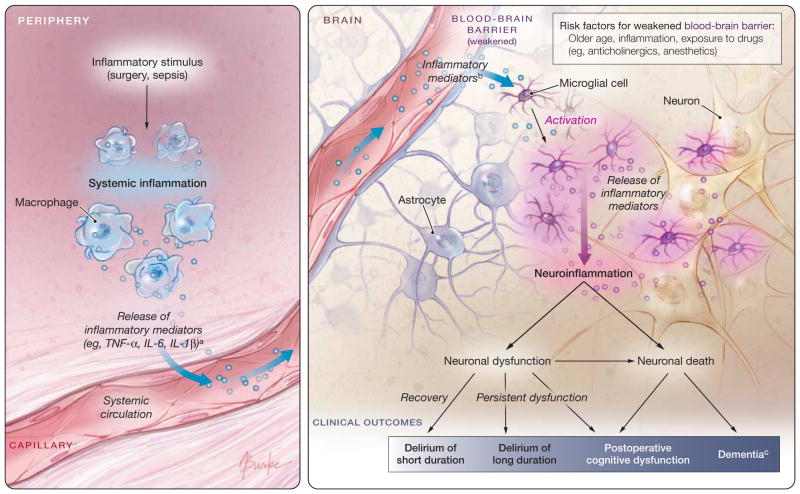

The pathophysiology of delirium is largely unknown, and different mechanisms may pertain in different circumstances.30 Cholinergic deficiency, or a failure of cholinergic neurons, is thought to be the final common pathway.31 Procholinergic drugs can reverse anticholinergic poisoning32 but have not demonstrated efficacy in more typical postoperative delirium (see “Preventability of Postoperative Delirium” section). Patients who develop postoperative delirium may have an accentuated inflammatory response to surgery33,34 or, in the case of Ms R, may have an intense inflammatory stimulus related to a postoperative infection. This inflammation may cross the blood-brain barrier and directly injure neurons, causing elevated biomarkers of neuronal injury and perhaps some of the long-term adverse effects of delirium35,36 (Figure). So far, this model is speculative and no specific treatment strategy is linked to these mechanisms.

Figure.

Inflammatory Model of the Pathophysiology of Postoperative Delirium

This figure depicts a theoretical inflammatory model for the pathophysiology of delirium that has direct relevance for Ms R and is gaining acceptance in the literature.34,36,102

aThe extent and magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response varies widely among individuals, possibly related to chronic activity of stress response systems.34

bIt is unknown which specific cytokines or mediators cross the blood-brain barrier.

cLikely risk factors for the long-term consequences of neuroinflammation include preexisting cognitive impairment, cerebrovascular disease, and severe illness.

Recognition and Diagnosis of Delirium

Delirium is a clinical diagnosis that requires assessment by care providers. No blood test or other laboratory or radiology test is available. A recent review of bedside diagnostic instruments recommended the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), which requires the presence of (1) acute change in mental status with a fluctuating course; (2) inattention; and either (3) disorganized thinking or (4) altered level of consciousness.37,38 The CAM has excellent sensitivity (86%) and specificity (93%) relative to an expert clinician’s diagnosis when administered by trained staff after a brief, targeted mental status evaluation.38 Simple tests of attention include having the patient repeat a sequence of random numbers in forward or backward order, recite the days of week or months of year backward, or raise his/her hand whenever he/she hears a certain letter or number in a list. Importantly, noncomatose patients who do not respond to these simple tests of attention most likely are demonstrating profound inattention due to delirium. Several ICU delirium instruments exist,39,40 including a variant of the CAM that uses only nonverbal responses, the CAM-ICU.40 The CAM-ICU is most appropriate for intubated patients and has lower sensitivity when used in verbal patients.41,42

Despite the availability of diagnostic algorithms, systematic assessment for delirium has not been widely adopted in practice. Studies that compare a research diagnosis of delirium with documentation by physicians and nurses suggest recognition rates of 20% to 50%.43–45 Risk factors for failure to recognize delirium include advanced age of the patient, preexisting dementia, and, most strongly, presence of the hypoactive or quiet form of delirium.45 Yet hypoactive patients are at risk of complications such as aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and malnutrition and their long-term outcomes are equal to or worse than those of patients with agitated delirium.46 Importantly, the hypoactive form of delirium is very noticeable to family members, as indicated by Ms R’s daughter,47 and some medical centers now encourage family members to bring mental status changes to the attention of the care team (GRADE48 level C).

Risk Factors for Delirium

A useful model divides delirium risk factors into 2 categories: predisposing factors that increase vulnerability to delirium and precipitating factors that initiate the event.49 The risk of delirium is the sum of predisposing and precipitating factors. Therefore, patients with a high burden of predisposing factors need fewer precipitants, while patients with a low burden of predisposing factors need strong precipitants to become delirious.49

Several validated clinical prediction rules summarize the preoperative risk of postoperative delirium.7,18,50 Consistent predisposing factors include advanced age (>70–75 years), preexisting dementia, and functional disability. Factors that appear in some models include laboratory abnormalities, increased comorbidity (especially cardiovascular disease), and history of depression. Using these models, patient predisposition for postoperative delirium can be stratified into low-, medium-, and high-risk groups.

In terms of precipitating factors, the most ubiquitous in the perioperative setting are the surgical procedure itself as well as anesthesia. Different surgeries represent varying degrees of physiological insult, with correspondingly different rates of delirium (eTable 1). For instance, major cardiac and vascular surgeries are much more likely to be associated with delirium than is cataract surgery. Intraoperative anesthesia also contributes to precipitating delirium, although the route (general vs regional) does not seem to have a major impact.51 This is likely because of the concomitant administration of sedatives with regional anesthesia (see “Preventability of Postoperative Delirium” section). Other common precipitating factors in the postoperative setting include exposure to sedating medications,52 poorly controlled postoperative pain,53 prolonged ICU stay,54 and the development of postoperative complications.5

Ms R has relatively few predisposing factors for delirium, the primary ones being her age and history of depression. Accordingly, one would expect a high burden of precipitating factors to initiate delirium. This was the case after her colectomy, as she did not develop delirium related to the initial surgery and anesthesia but became delirious only when she developed sepsis. This first episode seemed to render her more vulnerable, so she became delirious after the ileostomy closure when there were no complications. Table 1 summarizes how predisposing and precipitating factors may contribute to delirium risk.

Table 1.

Risk of Postoperative Delirium: Sum of Predisposing and Precipitating Factorsa

| Risk Factor Category | Predisposing Factors (Preoperative) | Precipitating Factors

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative | Postoperative | ||

| Major (2 points) | Advanced age (≥80 y) Dementia or recent delirium, not resolved |

High-risk surgical procedure (eg, major cardiac, open vascular, abdominal surgery) Emergency surgery Major complication |

Intensive care unit stay ≥2 d Major complication |

| Minor (1 point) | Older age (70–79 y) Mild cognitive impairment History of stroke Functional disability Laboratory abnormalities High medical comorbidity, including cardiovascular risk factors Alcohol/sedative abuse Depressive symptoms |

Moderate-risk surgical procedure (eg, most abdominal, orthopedic, ear, nose, and throat, gynecologic, urologic surgery) Unscheduled surgery General anesthesia Regional anesthesia with intravenous sedation Minor complication |

Intensive care unit stay <2 d Minor complication Poorly controlled pain, exposure to high-dose opiates/meperidine Exposure to sedatives |

The risk scores have not been validated but are based on the author’s evaluation of the literature. Overall risk strata based on risk scores are as follows (approximate rates of delirium are given in parentheses): low risk (<10%): 0–2 points7,13; moderate risk (10%–30%): 3–5 points7–11,19; high risk (30%–50%): 6–8 points6,10–12,14–18; and very high risk (>50%): ≥9 points.6,10,16–18

Relationship With Dementia and Depression

Both preexisting dementia and depression are risk factors for delirium and have an additive effect on risk.18,55 Recently, mild cognitive impairment has also been identified as a risk factor for delirium.18 Because delirium has been identified as an independent risk factor for incident dementia,28 these relationships may be bidirectional. A potential relationship of delirium with subsequent development of new-onset or worsening depression is less well studied, but examples similar to the experience of Ms R suggest that this relationship may also be present.

INTERVENTIONS FOR POSTOPERATIVE DELIRIUM

Preventability of Postoperative Delirium

A robust literature demonstrates the preventability of delirium, both in medical and surgical populations (Table 2 and eTable 2). The strongest evidence supports proactive, multifactorial interventions targeted to established risk factors for delirium (GRADE level B). The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) was originally tested in general medical patients, where it demonstrated a 40% relative risk reduction for delirium in a controlled clinical trial.56 HELP assesses 6 risk factors for delirium on admission and implements targeted interventions for each risk factor, largely through nonpharmacological, low-technology interventions carried out by trained volunteers. The HELP model has recently been expanded to surgical patients.57

Table 2.

Summary of Intervention Trials for Postoperative Delirium

| Nonpharmacological Trials | Pharmacological Trials | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | Multifactorial intervention programs | Anesthesia and analgesia practices

|

| Treatment | Multifactorial intervention programs

|

Antipsychotics |

Another prevention model with substantial support in surgical patients is geriatrics consultation, in which a proactive multifactorial protocol is implemented through targeted recommendations made by the consultant. In a randomized trial of hip fracture patients, this model led to a 36% relative risk reduction in delirium and a greater than 50% relative risk reduction in severe delirium.58 This model can been modified to co-management rather than strict consultation and expanded to other disciplines, such as hospital medicine. A similar multifactorial intervention for hip fracture patients implemented by nursing staff did not affect the incidence of delirium but did reduce its duration and severity.59

Several pharmacological interventions have been tested with medication administered proactively, rather than waiting for delirium to occur. Three classes of medications have been examined: antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, and sedatives in the ICU and during regional anesthesia.

With respect to antipsychotics, a study of low-dose haloperidol in hip surgery patients demonstrated no reduction in the incidence of delirium but a reduction of severity and duration.60 Another study of low-dose olanzapine, also in major lower extremity orthopedic surgery, demonstrated a reduction in incidence but an increase in duration and severity.61 A third study of intravenous haloperidol given to non–cardiac surgery patients admitted to the ICU showed a reduced incidence of delirium and shorter ICU stay.62 Clinicians worry about exposing large populations of patients to antipsychotics, reflecting concern about their safety profile.63,64 However, short-term use, as in the above trials, is likely of quite low risk (GRADE level I).

Cholinesterase inhibitors are a class of medications used widely in patients with dementia, in whom they have demonstrated modest efficacy in slowing cognitive decline.65 Since cholinergic deficiency may contribute to delirium,31 these drugs have a plausible role in prevention. However, randomized trials, performed largely in surgical populations, have not demonstrated benefit66–69 (GRADE level D).

Another prevention strategy is to modify use of sedating medications, particularly benzodiazepines, which have been associated with both delirium and long-term cognitive impairments after surgery and in the ICU.52,70–72 Three recent trials randomized patients to sedation with the α-adrenergic agonist dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam or midazolam in the ICU73,74 or vs propofol after cardiac surgery.75 All 3 trials showed equal levels of sedation and significantly reduced delirium days in the dexmedetomidine group, suggesting that this drug may be a less delirium-causing sedative for patients in the ICU setting73–75 (GRADE level B). Two trials of early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients in the medical ICU resulted in decreased sedative use, which also reduced delirium.76,77

A recent trial examined the use of conscious sedation in patients receiving spinal anesthesia for surgical repair of hip fracture. Patients’ propofol sedation was titrated using a bispectral monitor, and those randomized to the light sedation group had substantially less postoperative delirium than those in the deep sedation group78 (GRADE level I). The message of these trials is clear: reducing sedatives, particularly benzodiazepines, results in less delirium.

Taken as a whole, these studies suggest a role both for assessing patient’s risk of delirium preoperatively and for implementing proactive strategies to reduce this risk. For all high-risk patients, these strategies should include pro-active, multifactorial nonpharmacological approaches plus targeted pharmacological approaches.

Treatment of Delirium

Compared with the literature on prevention, rigorous evidence supporting the benefits of treatment for delirium is more limited (Table 2 and eTable 2). Nonetheless, guidelines have been developed documenting consensus on optimal practices. I will review the published evidence briefly and then suggest a “best practices” approach.

Studies of treatment of delirium must address challenges with recognition. Prevention models do not require identification of patients with delirium except for outcome ascertainment. However, for treatment studies, clinicians must be able to identify who is delirious. This has been a major barrier. Yet it is possible to improve the detection of delirium by clinicians.79

Treatment studies again divide into nonpharmacological multifactorial approaches and those that have evaluated the effect of drugs. The nonpharmacological studies largely have been performed outside the United States. They have used either specialized teams trained for systematic detection and treatment of delirium or reorganization of nursing care such that it becomes more patient centered rather than task centered. The results of these studies have been mixed, but they demonstrate at least some benefit in terms of shortened duration of delirium, reduced severity, and shortened hospital length of stay80–82 (GRADE level C). One nonpharmacological model within the United States is the “delirium room,”83 where patients with agitated delirium are treated supportively without use of sedating medications (GRADE level I).

Pharmacological treatment trials for delirium have been small and have not focused on surgical patients. A randomized trial of haloperidol, lorazepam, and chlorpromazine in younger patients with AIDS showed that all 3 drugs were effective in sedation, with haloperidol having the best adverse effect profile.84 Until recently, randomized trials of the newer atypical antipsychotics have been small comparative effectiveness studies with no placebo group; they have failed to demonstrate superiority of these agents over haloperidol.85–87 Recently, several small placebo-controlled trials of haloperidol and the atypical antipsychotics have been conducted in the ICU.88–90 Results have been mixed, and, importantly, the delirium severity scales91 used as the outcome measures for some trials heavily weight hyperactive symptoms; thus, conversion of a hyperactive patient to hypoactive could be interpreted as improvement (GRADE level I). In one study, treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor, rivastigmine, in an ICU population resulted in harm92 (GRADE level D).

In the absence of a definitive treatment trial, guidelines have outlined key steps in the treatment of delirium93–95:

There should be systematic case-finding in high-risk patients.

If delirium is identified, a thorough search for underlying contributing factors should be undertaken.

To the extent possible, factors identified in step 2 should be corrected.

Patient safety and support should be ensured, largely through nonpharmacological means, with judicious use of antipsychotics such as low-dose haloperidol when necessary (GRADE level B).

Management of Postoperative Pain

An issue particularly relevant to the surgical population is the management of postoperative pain in patients with delirium or at high risk of delirium. Evidence suggests that postoperative pain should be treated, but in the most judicious manner possible (GRADE level C). Opiate use is not a risk factor for delirium, but exposure to meperidine and high opiate doses increase risk.52,71,72 Use of local or regional analgesia and nonopiate analgesics may be helpful in limiting the total dose of opiate required.96,97 Opiates should be administered in a low-dose, scheduled fashion rather than as needed.98 If the patient reports that he/she is not having any pain, the scheduled medication can be held rather than relying on patients to request more medication when in pain. Patient-controlled analgesia can be effective for patients with adequate cognitive function99 and therefore is appropriate as a delirium prevention strategy (GRADE level I).

Long-term Follow-up of Delirium

Patients with delirium are at high risk of poor long-term outcomes. Surgeons and other clinicians who focus primarily on hospitalized patients may not be aware of all of its “downstream” effects on patient recovery.100,101 With recent increased emphasis on transitions of care, hospital-based clinicians should clearly document whether postoperative delirium developed, what workup was done to evaluate its causes, what treatment plan was initiated, and the status of the patient at discharge. Patients with delirium that is worsening or not adequately evaluated should not be discharged, particularly since such patients are likely to be readmitted quickly101 (GRADE level B).

Once discharged, patients who have experienced postoperative delirium need both short- and long-term follow-up. In the short term, mental status should be monitored closely for recurrence and intensive rehabilitation efforts initiated to reverse the cognitive and functional declines typical in these patients. Patients who are not improving should receive a comprehensive evaluation from their primary care physician or from a geriatrician or rehabilitation specialist2 (GRADE level I).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MS R

To summarize, delirium or acute confusion is perhaps the most common postoperative complication, yet it is often unrecognized by clinicians caring for surgical patients. Patients’ risk of delirium can be defined based on the sum of predisposing and precipitating factors. Effective approaches exist for the prevention of delirium, and the quest for improved detection and treatment is growing. Delirium may have long-term consequences, and these patients need careful follow-up to maximize their likelihood of full recovery.

If such patients require surgery again, a thorough preoperative evaluation by a physician expert is indicated.2 If a patient’s cognitive status has not returned to baseline, it might be best to postpone additional surgery until recovery is complete. When surgery is undertaken, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and medical specialists should carefully consider ways to minimize the stress of surgery and the total dose of anesthesia and sedation administered. Postoperatively, these patients should be actively co-managed by geriatricians, hospitalists, or intensivists, with daily delirium case finding. If delirium is detected, appropriate evaluation and management should commence promptly. Delirium diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment should be documented in the medical record and discharge summary to facilitate management across transitions of care.

Regarding what I would recommend in particular for Ms R if she faced surgery again, Ms R said, “I would hire an expert in delirium with the hope that that person might have some way of intervening early and avoid this from happening.” I concur fully. But I believe her risk of delirium with future surgery is quite small. Her predisposing risk factors for delirium were relatively few, and she developed delirium after her first surgery only in the setting of sepsis. She developed delirium immediately after her second surgery, which was without complications, but it is not clear whether she had fully recovered from the first surgery. Regardless, I would recommend the management strategy described herein to minimize her risk of recurrent delirium and maximize her chances for prompt and complete postoperative recovery.

EPILOGUE

Shortly after completing her interview for Clinical Crossroads, Ms R fell while getting out of her car and had a femoral fracture below her artificial hip, requiring emergency surgical repair. She received the careful perioperative care recommended herein and did not develop postoperative delirium. She was discharged on postoperative day 3 and recovered uneventfully.

QUESTIONS AND DISCUSSION

Question: It is important that one recognize that the brain is not just a neurologic but an immunologic organ and that this is probably the basis of delirium and POCD. One concern that I have is that plasma biomarker concentrations may not be reflective of concentrations in the brain. Would you care to comment?

Dr Marcantonio: I agree that examining immunological markers in the brain would be ideal, but it is challenging to obtain cerebrospinal fluid serially in surgical patients. Therefore, to complement human studies, a number of investigators are developing animal models for delirium and POCD that have some advantages of being able to control perioperative variables and to obtain fluids and tissues.102 Hopefully, these models will help to elucidate pathophysiology.

Question: This is probably the first formal discussion of postoperative delirium that most people in this audience have heard, both in their training and in their career. Why do you think that is? And how do we get the message out?

Dr Marcantonio: While delirium has been described since antiquity, the first official diagnosis did not appear until 1980, and we have developed good ways to measure it only in the past 15 years. It is very hard to pay attention to something you cannot measure well. Now that measurement strategies have been developed and there is a growing literature on prevention and treatment, there is need for more education and awareness of delirium. As older patients constitute more and more of the surgical population, delirium is going to be very difficult to ignore.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Marcantonio receives support from grants R01AG030618, P01AG031720, and Mid-Career Investigator Award K24 AG035075, all from the National Institute on Aging.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institute on Aging had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The conference on which this article is based took place at the Surgical Grand Rounds at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, on March 30, 2011.

Clinical Crossroads at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is produced and edited by Risa B. Burns, MD, series editor; Tom Delbanco, MD, Howard Libman, MD, Eileen E. Reynolds, MD, Marc Schermerhorn, MD, Amy N. Ship, MD, and Anjala V. Tess, MD.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The author has completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Online-Only Material: eTables 1 and 2 are available at http://www.jama.com.

Additional Contributions: We thank Ms R and her daughter for sharing their stories and for providing permission to publish them.

References

- 1.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcantonio ER. In the clinic: delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):itc6-1-ITC6-15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(5):1202–1211. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafson Y, Berggren D, Brännström B, et al. Acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36 (6):525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weed HG, Lutman CV, Young DC, Schuller DE. Preoperative identification of patients at risk for delirium after major head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(10):1066–1068. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199510000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneko T, Takahashi S, Naka T, Hirooka Y, Inoue Y, Kaibara N. Postoperative delirium following gastrointestinal surgery in elderly patients. Surg Today. 1997;27(2):107–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02385897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, Resnick NM. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galanakis P, Bickel H, Gradinger R, Von Gumppenberg S, Förstl H. Acute confusional state in the elderly following hip surgery: incidence, risk factors and complications. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(4):349–355. doi: 10.1002/gps.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider F, Böhner H, Habel U, et al. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in vascular surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milstein A, Pollack A, Kleinman G, Barak Y. Confusion/delirium following cataract surgery: an incidence study of 1-year duration. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):301–306. doi: 10.1017/s1041610202008499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böhner H, Hummel TC, Habel U, et al. Predicting delirium after vascular surgery: a model based on pre- and intraoperative data. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):149–156. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000077920.38307.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benoit AG, Campbell BI, Tanner JR, et al. Risk factors and prevalence of perioperative cognitive dysfunction in abdominal aneurysm patients. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(5):884–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olin K, Eriksdotter-Jönhagen M, Jansson A, Herrington MK, Kristiansson M, Permert J. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients after major abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92(12):1559–1564. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganai S, Lee KF, Merrill A, et al. Adverse outcomes of geriatric patients undergoing abdominal surgery who are at high risk for delirium. Arch Surg. 2007;142(11):1072–1078. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.11.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229–236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.795260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morimoto Y, Yoshimura M, Utada K, Setoyama K, Matsumoto M, Sakabe T. Prediction of postoperative delirium after abdominal surgery in the elderly. J Anesth. 2009;23(1):51–56. doi: 10.1007/s00540-008-0688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiely DK, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Orav EJ, Marcantonio ER. Characteristics associated with delirium persistence among newly admitted postacute facility patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(4):344–349. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.4.m344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, Zhong L. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):19–26. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudolph JL, Schreiber KA, Culley DJ, et al. Measurement of postoperative cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(6):663–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkins RO, Jackson JC. Short- and long-term cognitive outcomes in intensive care unit survivors. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30(1):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):955–962. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000119429.16055.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, de Jonghe JFM, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudolph JL, Inouye SK, Jones RN, et al. Delirium: an independent predictor of functional decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):643–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flacker JM, Lipsitz LA. Neural mechanisms of delirium: current hypotheses and evolving concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(6):B239–B246. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.6.b239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hshieh TT, Fong TG, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK. Cholinergic deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(7):764–772. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaver KM, Gavin TJ. Treatment of acute anticholinergic poisoning with physostigmine. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16(5):505–507. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramlawi B, Rudolph JL, Mieno S, et al. C-reactive protein and inflammatory response associated to neurocognitive decline following cardiac surgery. Surgery. 2006;140(2):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maclullich AMJ, Ferguson KJ, Miller T, de Rooij SEJA, Cunningham C. Unravelling the pathophysiology of delirium: a focus on the role of aberrant stress responses. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramlawi B, Rudolph JL, Mieno S, et al. Serologic markers of brain injury and cognitive function after cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4):593–601. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000239087.00826.b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Gool WA, van de Beek D, Eikelenboom P. Systemic infection and delirium: when cytokines and acetylcholine collide. Lancet. 2010;375(9716):773–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, Straus SE. Does this patient have delirium? value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010;304(7):779–786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859–864. doi: 10.1007/s001340100909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Ely EW, Gifford D, Inouye SK. Detection of delirium in the intensive care unit: comparison of Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit with Confusion Assessment Method ratings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):495–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neufeld KJ, Hayat MJ, Coughlin JM, et al. Evaluation of 2 intensive care delirium screening tools for non–critically ill hospitalized patients. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemiengre J, Nelis T, Joosten E, et al. Detection of delirium by bedside nurses using the Confusion Assessment Method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):685–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spronk PE, Riekerk B, Hofhuis J, Rommes JH. Occurrence of delirium is severely underestimated in the ICU during daily care. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(7):1276–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM., Jr Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467–2473. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.20.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiely DK, Jones RN, Bergmann MA, Marcantonio ER. Association between psychomotor activity delirium subtypes and mortality among newly admitted postacute facility patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):174–179. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morita T, Hirai K, Sakaguchi Y, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. Family-perceived distress from delirium-related symptoms of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(2):107–113. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.US Preventive Services Task Force. [Accessed June 4, 2012.];GRADE definitions. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

- 49.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275(11):852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalisvaart KJ, Vreeswijk R, de Jonghe JF, van der Ploeg T, van Gool WA, Eikelenboom P. Risk factors and prediction of postoperative delirium in elderly hip-surgery patients: implementation and validation of a medical risk factor model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):817–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Mattis S, Szatrowski TP, Charlson ME. Cognitive effects after epidural vs general anesthesia in older adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1995;274(1):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, et al. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1518–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lynch EP, Lazor MA, Gellis JE, Orav J, Goldman L, Marcantonio ER. The impact of postoperative pain on the development of postoperative delirium. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(4):781–785. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291 (14):1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Givens JL, Sanft TB, Marcantonio ER. Functional recovery after hip fracture: the combined effects of depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1075–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen CCH, Lin MT, Tien YW, Yen CJ, Huang GH, Inouye SK. Modified hospital elder life program: effects on abdominal surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Milisen K, Foreman MD, Abraham IL, et al. A nurse-led interdisciplinary intervention program for delirium in elderly hip-fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):523–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1658–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larsen KA, Kelly SE, Stern TA, et al. Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(5):409–418. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.51.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang W, Li HL, Wang DX, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis decreases delirium incidence in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):731–739. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182376e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(22):2335–2341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):56–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liptzin B, Laki A, Garb JL, Fingeroth R, Krushell R. Donepezil in the prevention and treatment of post-surgical delirium. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(12):1100–1106. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.12.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sampson EL, Raven PR, Ndhlovu PN, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil hydrochloride (Aricept) for reducing the incidence of postoperative delirium after elective total hip replacement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):343–349. doi: 10.1002/gps.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gamberini M, Bolliger D, Lurati Buse GA, et al. Rivastigmine for the prevention of postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery—a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1762–1768. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819da780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marcantonio ER, Palihnich KA, Appleton P, Davis RB. Pilot randomized trial of donepezil hydrochloride for delirium after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11 suppl 2):S282–S288. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK. Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):177–183. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192fcf9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik Y. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644–2653. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine Compared With Midazolam Study Group. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(5):489–499. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maldonado JR, Wysong A, van der Starre PJ, Block T, Miller C, Reitz BA. Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):206–217. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(4):536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sieber FE, Zakriya KJ, Gottschalk A, et al. Sedation depth during spinal anesthesia and the development of postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture repair [published correction appears in Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(4):400] Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):18–26. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marcantonio ER, Bergmann MA, Kiely DK, Orav EJ, Jones RN. Randomized trial of a delirium abatement program for postacute skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(6):1019–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lundström M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):622–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pitkälä KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(2):176–181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178–186. doi: 10.1007/BF03324687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Flaherty JH, Tariq SH, Raghavan S, Bakshi S, Moinuddin A, Morley JE. A model for managing delirious older inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):1031–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):231–237. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Campbell N, Boustani MA, Ayub A, et al. Pharmacological management of delirium in hospitalized adults—a systematic evidence review. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):848–853. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0996-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lacasse H, Perreault MM, Williamson DR. Systematic review of antipsychotics for the treatment of hospital-associated delirium in medically or surgically ill patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(11):1966–1973. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grover S, Kumar V, Chakrabarti S. Comparative efficacy study of haloperidol, olanzapine and risperidone in delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(4):277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, et al. MIND Trial Investigators. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428–437. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181c58715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Devlin JW, Roberts RJ, Fong JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):419–427. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9e302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tahir TA, Eeles E, Karapareddy V, et al. A randomized controlled trial of quetiapine vs placebo in the treatment of delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69 (5):485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, Norton J, Jimerson N. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the Delirium Rating Scale and the Cognitive Test for Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229–242. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van Eijk MM, Roes KC, Honing ML, et al. Effect of rivastigmine as an adjunct to usual care with haloperidol on duration of delirium and mortality in critically ill patients: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1829–1837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bergmann MA, Murphy KM, Kiely DK, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER. A model for management of delirious postacute care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1817–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shekelle PG, MacLean CH, Morton SC, Wenger NS. ACOVE quality indicators. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8 pt 2):653–667. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Young J, Murthy L, Westby M, Akunne A O’Mahony R; Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c3704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schug SA, Sidebotham DA, McGuinnety M, Thomas J, Fox L. Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patient-controlled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(2):368–372. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199808000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Leung JM, Sands LP, Rico M, et al. Pilot clinical trial of gabapentin to decrease postoperative delirium in older patients. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1251–1253. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233831.87781.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paice JA, Noskin GA, Vanagunas A, Shott S. Efficacy and safety of scheduled dosing of opioid analgesics: a quality improvement study. J Pain. 2005;6(10):639–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mann C, Pouzeratte Y, Boccara G, et al. Comparison of intravenous or epidural patient-controlled analgesia in the elderly after major abdominal surgery. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(2):433–441. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Morris JN. Delirium symptoms in post-acute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):4–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marcantonio ER, Kiely DK, Simon SE, et al. Outcomes of older people admitted to postacute facilities with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6):963–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Terrando N, Eriksson LI, Ryu JK, et al. Resolving postoperative neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(6):986–995. doi: 10.1002/ana.22664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]