SYNOPSIS

Objective

This study examined how parents’ optimism influences positive parenting and child peer competence in Mexican-origin families.

Design

A sample of 521 families (521 mothers, 438 fathers, and 521 11-year-olds) participated in the cross-sectional study. We used structural equation modeling to assess whether effective parenting would mediate the effect of parents’ optimism on child peer competence and whether mothers’ and fathers’ optimism would moderate the relation between positive parenting and child social competence.

Results

Mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were associated with effective parenting, which in turn was related to children’s peer competence. Mothers’ and fathers’ optimism also moderated the effect of parenting on child peer competence. High levels of parental optimism buffered children against poor parenting; at low levels of parental optimism, positive parenting was more strongly related to child peer competence.

Conclusions

Results are consistent with the hypothesis that positive parenting is promoted by parents’ optimism and is a proximal driver of child social competence. Parental optimism moderates effects of parenting on child outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Research has shown that positive parenting, involving warmth, affection, monitoring, and positive engagement, is associated with more positive child adjustment (Caspi et al., 2004; Smith, Landry, & Swank, 2000). Numerous studies have also documented the benefits and detriments of children’s peer relationships (for a review, see Rubin, Chen, Coplan, Buskirk, & Wojslawowicz, 2005). The pervasive effects of parenting on child adjustment and the importance of children’s peer relationships highlight the need to understand parent characteristics that predict effective and ineffective parenting and factors that promote positive peer functioning. Previous research suggests that parental dispositional traits can influence parenting behaviors. Although robust relations are reported between the Big Five personality factors and three dimensions of parenting: warmth, behavioral control, and autonomy support) (Prinzie, Stams, Dekovic, Reijntjes, & Belsky, 2009), the effects of dispositional optimism on parenting have not been studied and are one of the foci of this investigation.

In considering specific family processes and parental characteristics that promote healthy peer relationships for children, we also considered the fact that immigrant families constitute an increasing proportion of the U.S. population. Nearly 17% of children in the U.S. under the age of 18 are living with a foreign-born householder, and this percentage doubles for children under the age of 6 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). One of these subgroups, the Latino population, is expected to grow to nearly 25% of the U.S. population by 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau 2008). Latinos of Mexican origin account for almost 60% of U.S. Latinos. Despite these trends, very little developmental research has focused on children in Mexican-origin families. To help address this need, the California Families Project (CFP) was initiated in 2006 to study over 670 Mexican-origin children and their families.

The present investigation uses data from the CFP to identify parental behaviors and characteristics in Mexican-origin families that facilitate the development of children’s peer competence. First, we attempted to replicate the documented relation between positive parenting and child peer competence found in European American (Conger & Conger, 2002), African American (Conger et al., 2002), and recent Mexican immigrant families (Leidy, Guerra, & Toro, 2010). In addition, we examined the relation of parent personality—specifically dispositional optimism—with child peer competence. Although it has not been linked directly to peer competence, previous research and theory suggest that optimism is an enduring resource that facilitates a wide range of positive developmental outcomes (Assad, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007; Carver, Scheier, & Fulford, 2008). Moreover, given repeated calls to move beyond main effects and test for interactions between personality and parenting (Belsky, 1984; Belsky & Barends, 2002; Shiner & Caspi, 2003), we examined whether mothers’ and fathers’ dispositional optimism modified the effects of positive parenting on children’s peer competence.

Positive Parenting

Positive parenting has been found to foster positive and discourage negative child adjustment. For example, parent behaviors like warmth, affection, monitoring, and positive engagement predict optimal social and cognitive functioning of children (Smith et al., 2000) and are associated with improved academic performance and social skills with peers (Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997) and fewer externalizing problems (Caspi et al., 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Pettit et al., 1997) and internalizing symptoms (Dumka, Roosa, & Jackson, 1997). Germane to this study, Dumka et al. (1997) found that mothers’ supportive parenting mediates relations between family risk factors and children’s depression and misconduct for children of Mexican origin, and Leidy et al. (2010) corroborated the finding that positive parenting predicts social self-efficacy using a sample of children of Mexican immigrant families.

Peer Relationships

Existing literature on children’s peer relationships asserts advantages and disadvantages of social bonds with particular peer groups. For example, children who associate with positive peer groups exhibit higher levels of social competence and cognitive abilities (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995; Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993; Rubin et al., 2005). Conversely, children who associate with negative peer groups exhibit lower levels of academic achievement and higher levels of aggression, social withdrawal, delinquency, school suspensions and dropout, and unemployment (Kupersmidt & Coie, 1990; Newcomb et al., 1993; Rubin et al., 2005). Furthermore, peer competence has been related to better grade point average and higher levels of global adaptive functioning (Rockhill, Stoep, McCauley, & Katon, 2009).

Dispositional Optimism

In light of the parenting and peer relationships literatures, we directed our attention to understanding how parents might encourage positive peer functioning and identifying parental characteristics that might be associated with positive parenting. There is reason to believe that optimism may promote positive parenting behaviors. For example, Scheier and Carver (1985) conceptualized dispositional optimism as a relatively stable, generalized tendency of individuals to expect positive outcomes in life. Research shows that individuals who are high in optimism enjoy better physical health, increased longevity, higher levels of emotional well-being, more positive social relationships, and improved capacity to cope with a broad range of stressful situations (Assad, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007; Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002; Carver, Scheier, & Fulford, 2008; Kochanska, Aksan, Penny, & Boldt, 2007; Segerstrom, Taylor, Kemeny, & Fahey, 1998). The influence of optimism on physical, psychological, and social adjustment is generally attributed to the superior coping strategies of optimistic individuals (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Optimists tend to rely on active, problem-focused coping when faced with stressful life events, whereas pessimists tend to disengage when goal pursuit becomes too stressful (Nes & Sergerstrom, 2006; Scheier & Carver, 1992).

Findings such as these suggest that individuals with higher levels of optimism should have better skills for dealing with the stresses and challenges of parenting. Studies by Brody and colleagues (Brody & Flor, 1997; Brody, Murry, Kim, & Brown, 2002) demonstrated that mothers with more optimistic outlooks and higher self-esteem are more likely to use competence-promoting parenting practices, which predict higher child cognitive competence, social competence, and psychological adjustment across time. For instance, Jones, Forehand, Brody, and Armistead (2002) found that maternal optimism was associated with positive parenting and that positive parenting was associated with lower internalizing and externalizing child behaviors in inner-city single-parent African American families. Taylor, Larsen-Rife, Conger, Widaman, and Cutrona (2010) also found that, for African American single-mother families with adolescent children, maternal optimism predicted lower levels of maternal internalizing symptoms and higher levels of effective child management. Optimism may also bolster the quality of parent-child relationships. Hjelle, Busch, and Warren (1996) reported that dispositional optimism was positively correlated with maternal warmth and acceptance and negatively correlated with aggression, hostility, neglect, indifference, and rejection during middle childhood. Kochanska et al. (2007) found that optimistic parents remained warm and affectionate toward their children despite experiencing high demographic risks, whereas demographic risk decreased positive parenting for those with lower levels of optimism.

The Current Study

Together, these studies suggest that dispositional optimism serves as an important psychological resource that promotes better parenting. In addition, these studies reflect the general tendency in the field to gather data primarily from mothers in parenting research. Although this trend is changing, work that includes father data deserves attention. In instances where both mothers and fathers participate in a study, it seems reasonable to ask whether fathers’ effects differ from mothers’ effects. Thus, we predicted that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism will promote positive parenting which will, in turn, be associated with higher levels of child peer competence; that is, we predicted that effective parenting would mediate the effect of optimism on peer competence. Moreover, we predicted that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism will moderate the relation between positive parenting and child social competence. Specifically, we expected that children who experienced both positive parenting and high parental optimism would achieve the greatest benefits in terms of the development of social competence. Our reasoning is that, when both positive parenting and parental optimism are high, children learn from parents both through direct social interaction and by having an optimistic model for effective coping behaviors in social relationships. Simply put, we expected optimism to amplify the benefits of positive parenting in relation to child social competence. Finally, we investigated whether mothers and fathers have equal roles in the predicted associations.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

The California Families Project (CFP) is an ongoing longitudinal study in which families of Mexican origin, as indicated by their heritage and self-identification, were recruited from a large metropolitan area in northern California. Eligible families had a typically functioning child (first, second, or third generation of Mexican origin) in the 5th grade of a public or Catholic school, who had been living with his or her biological mother. Both two-parent (N = 548) and single parent (N = 124) families were recruited for the study. The father in two-parent families had to be the child’s biological father.

Rosters of 5th grade children from two school districts were used to select randomly the families who were invited to participate. Of the eligible families, 72.5% agreed to participate. Data were collected during the 2006–2007 and 2007–2008 school years. For this report, 671 5th grade children (333 females, 338 males), 671 mothers, and 438 fathers had data available for analysis. However, we restricted our focus to the 521 children (M age = 10.86 years, SD = .51, age range: 10–13 years; 521 mothers and 438 fathers) from two-parent families for whom peer competence data were available.

Trained research staff interviewed the participants in their homes. All interviewers were fluent in both Spanish and English and were either Latino/a or had extensive experience in the Latino community. They visited the families on two separate occasions within a 1-week period to avoid respondent fatigue. Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English based on the preference of the participant. On average, mothers had spent 16.1 years (SD = 10.6) in the United States and were 36.8 years old (SD = 5. 9), and fathers had spent 19.4 years (SD = 9.8) in the United States and were 39.4 years old (SD = 6.1). The educational level ranged from no schooling to Master’s degree for the mothers (81.7% completed high school or less) and from 1 year of schooling to doctoral or other advanced degree for the fathers (82.4% completed high school or less).

Measures

Dispositional optimism

The revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) was used to measure dispositional optimism (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). This is the most widely used and best validated measure of optimism, with two decades of research demonstrating its construct validity in a wide range of contexts (for a review see Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010). In the second interview visit, mothers and fathers were instructed to indicate their agreement with each of the six statements using an anchored 4-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree and 4 = Strongly Agree. Sample items included “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best.” and “If something can go wrong for me, it will.” The coefficient alpha for this scale was .51 for mothers and .52 for fathers. Following the recommendations of Little, Oettingen, and Baltes (1995), the 3 negatively keyed items were reversed scored, and then three parcels with 2 items each (one positively keyed and one negatively keyed) were computed, separately for mothers and fathers. Prior work suggests the use of parcels as indicators of latent variables is defensible (Bandalos & Finney, 2001). Parcels result in higher reliability, better model fit, and more stable statistical solutions (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Furthermore, research has shown that the use of parcels in latent variable models reduces the biasing effects of measurement error (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005), an important consideration given the coefficient alpha for this scale. Little et al. (1995) recommended coupling positively and negatively worded items to decrease acquiescence bias relative to the construct. The resulting aggregate reliability for the parcels used in the analyses was .61 for mothers and .65 for fathers.

Positive parenting

Positive parenting was measured using three different informants: mother, father, and child. During the second interview visit, each informant reported on three different scales: parental warmth, parental monitoring, and parental positive reinforcement and inductive reasoning. Mothers reported on fathers, fathers reported on mothers, and children reported on both mothers and fathers. The self-reports of mothers and fathers were not included to reduce reporter method factors in the structural equation models (this was necessary due to parceling methods described below). All ratings were made using an anchored 4-point Likert scale in which 1 = Almost never or never and 4 = Almost always or always.

The parental warmth scale consisted of a subset of 9 items from the Behavioral Affect Rating Scale (BARS; Conger, 1989a). Respondents were asked to indicate how often during the past 3 months parents displayed warmth toward the child (e.g., “How often did parent ask child for his/her opinion about an important matter.”, “Help child do something that was important to child.”, and “Act supportive and understanding toward child.”). Coefficient alpha reliabilities for the warmth scale across all informants were .82 for reports on mothers and .87 for reports on fathers.

The parental monitoring items consisted of an adapted version of a scale developed by Small and Kerns (1993) and Small and Luster (1994). The original scale was designed as a self-report measure for adolescents. However, because the present study includes both child reports and parent reports of parenting behaviors, we created an equivalent 14-item version for the parents to assess their partner’s parenting over the last 3 months (e.g. “Father knew how child spent his/her money.”) and for the children to assess their parents parenting also over the last 3 months (e.g. “Your dad knew the parents of your friends.” and “Your mom knew what you were doing after school.”). Reliabilities across all informants for the monitoring scale were .88 for reports on mothers and .91 for reports on fathers.

The parental positive reinforcement and inductive reasoning scale consisted of a subset of 9 items from the Iowa Parenting Scales (Conger, 1989b). For these items, respondents were asked to indicate how often parents provided positive reinforcement to the child when he or she does a good thing or participates in an event (e.g., gets good grades or is involved in sports). Respondents also reported how often parents encouraged the child to engage in inductive reasoning; sample items included “How often does parent give child reasons for his/her decisions?” and “How often does parent discipline child by reasoning, explaining, or talking to him/her?” Alpha reliabilities across informants for the positive reinforcement and inductive reasoning scale were .83 for mothers and .85 for fathers.

We created two parcels for each of the parenting components (for a total of six parcels: mothers’ and fathers’ warmth, mothers’ and fathers’ monitoring, and mothers’ and fathers’ positive reinforcement and inductive reasoning) following the domain-representative procedure outlined by Kishton and Widaman (1994), which allows rater-specific variance and variance common across raters to contribute to the latent factor. The construction of domain-representative parcels allows information from each reporter to be treated as equally valid (or equally biased) and unit-weights the raters by distributing their information across the parcels. A two-factor (i.e., mothers’ positive parenting and fathers’ positive parenting) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of these parcels revealed a correlation between mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting of r = .67. Given this high degree of association and preliminary analyses, we created three parcels that represented both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting in each of the parenting components. The coefficient alpha reliability of the three resulting parcels was .88.

Child’s peer competence

To assess child peer competence, we used the peer competence subscale from the Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter, 1982). The 9 items were administered during the first interview visit and are intended to measure manifest behaviors, rather than the ability to behave in a particular way. Sample items included “You have a lot of arguments or fights with kids your age in your neighborhood.” and “Compared to others your age, you have a lot of friends.” An anchored 4-point Likert scale was used in which 1 = Not at all true and 4 = Very true. After reversing the 3 negatively keyed items, three parcels (with 3 items each) were computed (Little et al., 1995). That is, rather than grouping items that are more similar to each other, we included 1 negatively worded item in each of the parcels to reduce acquiescence bias. The coefficient alpha reliability of the peer competence scale items was .64, and the coefficient alpha of the resulting parcels was .70.

All measures were submitted to forward- and back-translation as well as pilot testing prior to administration.

Analytic Techniques

Our proposed model involves testing moderation effects with latent variables. Although interactive effects can be tested using manifest variables in the General Linear Modeling framework, testing interactions with latent variables in Structural Equation Modeling is preferred because measurement error does not contaminate estimates of effects (Moulder & Algina, 2002). Several methods for testing latent variable interactions have been proposed (for a comparison of methods, see Marsh, Wen, & Hau, 2004). For our model, we chose to use the Latent Moderated Structural Equations (LMS) approach (Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000) implemented in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) with Maximum Likelihood estimation. This technique does not require specification of nonlinear constraints or the computation of new product variables as indicators; importantly, the LMS approach has been shown to have higher efficiency of parameter estimates and more reliable standard errors when compared to other methods (Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000).

Our choice of the LMS approach comes with certain implications. First, the LMS does not produce overall model fit statistics (such as CFI or RMSEA), as these have not been developed for this type of model. However, Klein and Moosbrugger (2000) suggested using log likelihood ratio tests to compare the interaction model against a model that excludes the interaction. This, together with the overall fit statistics from the model without interaction effects, can be helpful in assessing the goodness of fit. Second, standardized coefficients are not available from Mplus output. Thus, raw estimates are reported for all our results. Third, the LMS approach does not permit the estimation of bootstrapped standard errors and confidence intervals. Therefore, we used a Sobel test to assess the significance of the indirect effects in our model. Bootstrapping has become a common choice for testing the significance of indirect effects in mediation models, but the Sobel test has been shown to provide accurate results in samples of 500 or more (MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995). Finally, the LMS technique does not allow for multiple-group comparisons.

To identify the models reported below, we set the variances of all latent variables to unity, allowing for the free estimation of factor loadings, with the exception of the optimism latent variables. For the optimism latent variables, the mothers’ optimism latent variable variance was set to 1, the fathers’ optimism latent variable variance was freely estimated, and the factor loadings and intercepts for these two latent variables were set to be equal across mothers and fathers (formal tests of the appropriateness of these equality constraints are reported below). This was done with the purpose of facilitating comparisons among the parental influences on parenting and child peer competence.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

All analyses were performed using Mplus version 5.21 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Before testing our proposed model, we investigated whether parental optimism was better represented as a single factor, combining reports of mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors into a single parental latent variable (e.g., parental optimism), or as two separate factors (e.g., one factor for mothers’ optimism and a second factor for fathers’ optimism). We specified a model that included the three mother parcels as indicators of a mother optimism group factor, the three father parcels as indicators of a father optimism group factor, and all six parcels as indicators of a parental optimism general factor. This approach leads to a bi-factor model representation, also termed a hierarchical model by Yung, Thissen, and McLeod (1999). The results showed that optimism is best represented as a two-factor model (with separate, modestly correlated factors for mothers and fathers), because the general factor explained very little variance in the observed data.

We repeated these analyses to test whether positive parenting was better represented as a single factor or as two separate factors. In contrast to optimism, positive parenting was best represented by a single factor (combining mothers and fathers), because the general factor explained almost all of the reliable variance and the remaining group factors explained very little variance. These results reflect the fact that paternal and maternal optimism were only weakly correlated, whereas positive parenting was quite consistent across mothers and fathers in a given family in our sample.

Modeling Effects of Optimism and Parenting on Child Peer Competence

Correlations among latent variables

We hypothesized that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism would be associated with positive parenting, which would, in turn, be associated with child peer competence. Also, we hypothesized that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism would moderate the parenting-competence relation in addition to having direct effects on child peer competence. In our model, we controlled for family income and education by adding these variables as covariates. Specifically, we allowed these variables to correlate with mothers’ and fathers’ optimism and to predict parenting and child peer competence. Correlations among the latent variables specified in our model are presented in Table 1. These correlations suggest that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were related to positive parenting, and the latter was associated with child peer competence. Fathers’ optimism was related to child peer competence; the relation between mothers’ optimism and peer competence was not significant, but was in the expected direction. Furthermore, family income was not associated with any constructs of interest, except parental education, which was related to the optimism and parenting constructs. Table 2 shows covariances (above the diagonal), correlations (below the diagonal), means, and standard deviations for the manifest indicators in the structural model. As expected, the highest correlations were among those parcels that were used as indicators of a given common factor. Also, the means suggested that a majority of individuals reported slightly higher than average levels of all parenting facets, optimism, and peer competence.

TABLE 1.

Correlations among Latent Variables Specified in Hypothesized Model

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fathers’ optimism | -- | |||||

| 2. Mothers’ optimism | .17* | -- | ||||

| 3. Positive parenting | .26*** | .17* | -- | |||

| 4. Child peer competence | .14* | .08 | .49*** | -- | ||

| 5. Family income | .01 | .07 | −.03 | .03 | -- | |

| 6. Parental education | .19*** | .21*** | .19*** | .09 | .33*** | -- |

p < .05.

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Covariances (above diagonal), Correlations (below diagonal), Means, and Standard Deviations of the Parcels Used as Indicators of the Proposed Model

| Parcels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive parenting parcel 1 | -- | .09 | .10 | .06 | .09 | .09 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .02 |

| 2. Positive parenting parcel 2 | .70 | -- | .08 | .05 | .07 | .08 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .02 |

| 3. Positive parenting parcel 3 | .78 | .68 | -- | .04 | .06 | .07 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .01 |

| 4. Peer competence parcel 1 | .24 | .22 | .18 | -- | .25 | .21 | .01 | .00 | .02 | .03 | .02 | .01 |

| 5. Peer competence parcel 2 | .33 | .29 | .25 | .49 | -- | .23 | −.01 | .02 | .01 | −.01 | −.01 | .02 |

| 6. Peer competence parcel 3 | .37 | .37 | .31 | .46 | .52 | -- | −.01 | .02 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .02 |

| 7. Mothers’ optimism parcel 1 | .06 | .03 | .07 | .03 | −.02 | −.04 | -- | .06 | .07 | .01 | .01 | .03 |

| 8. Mothers’ optimism parcel 2 | .08 | .04 | .05 | .00 | .06 | .08 | .25 | -- | .11 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| 9. Mothers’ optimism parcel 3 | .08 | .09 | .04 | .06 | .02 | .07 | .34 | .49 | -- | .01 | .01 | .00 |

| 10. Fathers’ optimism parcel 1 | .14 | .14 | .12 | .10 | −.03 | .13 | .06 | .05 | .03 | -- | .10 | .06 |

| 11. Fathers’ optimism parcel 2 | .12 | .11 | .11 | .07 | −.04 | .08 | .03 | .03 | .04 | .48 | -- | .08 |

| 12. Fathers’ optimism parcel 3 | .13 | .12 | .07 | .04 | .05 | .05 | .15 | .03 | .02 | .29 | .33 | -- |

|

| ||||||||||||

| M | 2.92 | 3.49 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 3.16 | 3.41 | 2.90 | 2.92 | 2.91 | 2.90 | 2.93 | 2.94 |

| SD | .38 | .33 | .34 | .72 | .75 | .66 | .45 | .47 | .47 | .44 | .50 | .48 |

Fit of the a priori model

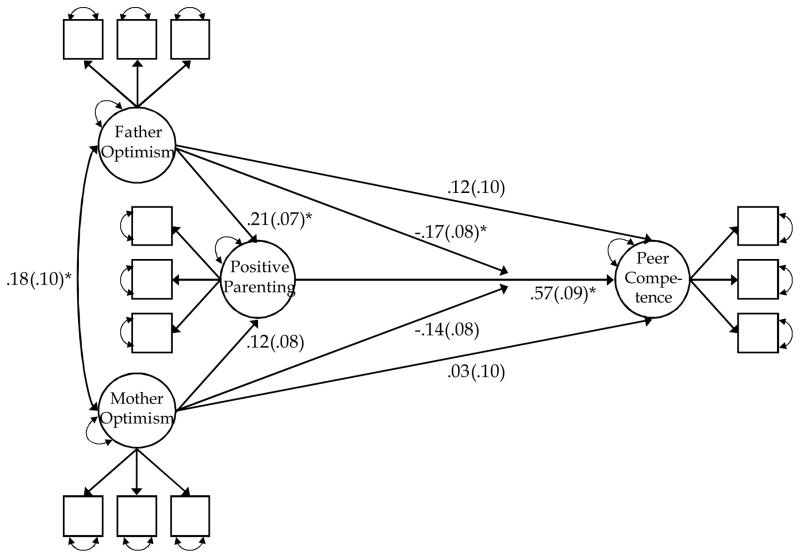

The proposed model was specified and fit to the data. We also fit a second model to the data; in this alternative model, the interaction effects of mothers’ optimism and fathers’ optimism with positive parenting were deleted. Relative fit indices and standardized parameters were not available for our first model due to the inclusion of two multiplicative latent variables (Mothers’ optimism X Parenting and Fathers’ optimism X Parenting). However, a likelihood ratio test between the two models showed that the proposed latent interaction model was preferable, Δχ2 (2) = 11.84, p < .01. Furthermore, fit indices for the model without interaction effects showed excellent fit, χ2(66) = 60.79, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = 0.00, respectively. Results for the proposed model are presented on Figure 1. This model shows that fathers’ optimism positively predicted positive parenting (b = 0.21, SE = 0.07, p < .05), which in turn predicted higher child peer competence (b = 0.57, SE = 0.09, p < .01). Furthermore, fathers’ optimism significantly moderated the association between positive parenting and child peer competence (b = −0.17, SE = 0.08, p < .05). According to this model, mothers’ optimism did not play a significant role in positive parenting or child peer competence.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized regression parameters for the proposed model with standard errors in parentheses. Empty boxes represent parcels which serve as indicators of the corresponding latent variables. The arrows pointing from mothers’ and fathers’ optimism to the arrow connecting positive parenting to peer competence are used to indicate interaction effects. Not illustrated in this path diagram, family income and parental education were controlled by specifying them as correlates of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism and parenting and child peer competence. * p < .05.

Testing differences in magnitude of mothers’ and fathers’ effects

Because our proposed model hypothesized direct effects from mothers and fathers to parenting and child peer competence as well as interaction effects of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism on the link between parenting and child peer competence, an important theoretical question emerges: Are the mothers’ and fathers’ predictive paths equivalent? Results from the proposed model suggested that only fathers’ optimism played a significant role in positive parenting and peer competence. However, tests of significance in that model simply indicate if a parameter estimate differs significantly from zero, not if it differs significantly from another parameter in the model. By placing equality constraints across mothers’ and fathers’ structural paths in the proposed model, we can investigate if mothers’ and fathers’ paths differ significantly. Given our model, three separate equality constraints can be considered. First, equality constraints can be set on the direct effect paths from optimism to parenting. Second, constraints can be placed on the direct effect paths from optimism to child peer competence. Third, the interaction effect paths can also be constrained to equality.

Prior to taking these steps, one must check that the conceptualization of optimism is the same across mothers and fathers. This can be done by conducting tests of factorial invariance. To ensure that mothers’ reports of optimism had the same meaning as fathers’ reports, the factor loadings and intercepts of the indicators of these latent variables need to be constrained to equality without significant loss of model fit. In other words, strong factorial invariance must be established (see Widaman & Reise, 1997).

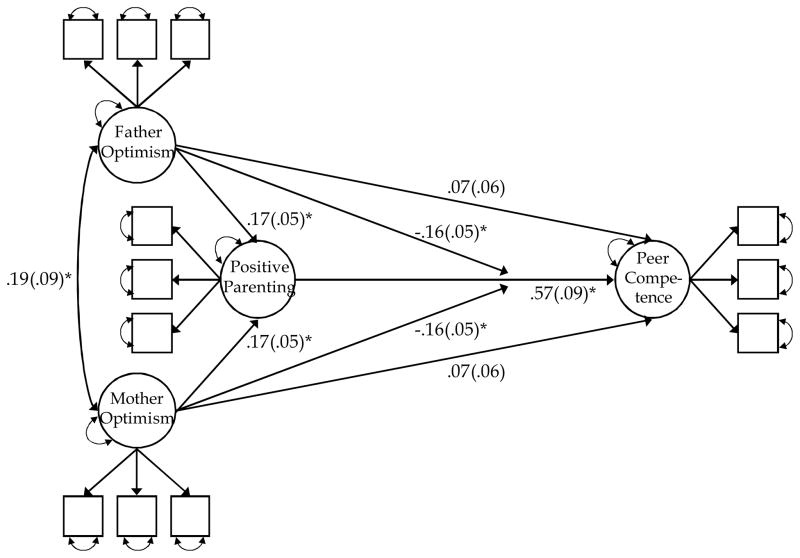

We proceeded to carry out this test with our model. The configural invariance model resulted in a −2*Log Likelihood of 11542.08, which follows a chi-square distribution with df = 48. The −2*LL for the strong factorial invariance model was 11547.83 with df = 53. A likelihood ratio test of difference in model fit (with the configural invariance model as reference for comparison) revealed that constraints invoked in the strong factorial invariance did not affect model fit, Δχ2 (5) = 5.75, p = .33, suggesting that the measurement parameter estimates for mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were comparable. The next step entailed comparing the equivalence of the structural paths. A likelihood ratio test indicated that setting equality constraints on the mothers’ and fathers’ direct effects from optimism to parenting and to child peer competence as well as the mothers’ and fathers’ interaction effects on the relations between parenting and child peer competence did not affect the model fit significantly, Δχ2 (3) = 1.18, p = .76, suggesting that mothers’ and fathers’ direct paths to parenting and child peer competence did not differ from each other. Figure 2 shows the unstandardized regression parameters from the proposed model with the equality constraints imposed. We fit a CFA with the latent variable indicators included in our final model (i.e., the three parcels for mothers’ optimism, the three parcels for fathers’ optimism, the three parcels for positive parenting, and the three parcels for child peer competence). The CFA model had excellent fit, χ2(64) = 56.04, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, and the standardized factor loadings ranged from a low 0.42 to a high 0.90, and averaged 0.68, suggesting a good measurement model. Adding the equality constraints to the final model allowed for higher precision in parameter estimation, as reflected in smaller standard errors and a more precise and parsimonious representation of the data (see Figure 2). The improved precision of parameter estimation was the principal reason why parameter estimates for mothers’ effects that were not significant in the model without equality constraints were now statistically significant. Because the model with equality constraints did a better job at representing the data (as indicated by fit indices, model comparisons, and standard errors), we considered the results from this model superior from the model without the equality constraints. The hypothesized mediated effect of parents’ optimism on child peer competence through positive parenting was observed for mothers and fathers. That is, a significant direct effect from mothers’ and fathers’ optimism to positive parenting was found, b = 0.17, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.07, 0.27], for both, and in turn, positive parenting had a significant direct effect on child peer competence, b = 0.57, SE = 0.09, p < .001, 95% CI [0.39, 0.75]. The indirect effects for mothers’ and fathers’ optimism to child peer competence of .10, SE = .03, were statistically significant, z = 3.00, p < .005, 95% CI [0.04, 0.16], as indicated by a Sobel test.

Figure 2.

Unstandardized regression parameters for the proposed model with standard errors in parentheses and equality constraints. Empty boxes represent parcels which serve as indicators of the corresponding latent variables. The arrows pointing from mothers’ and fathers’ optimism to the arrow connecting positive parenting to peer competence are used to indicate interaction effects. Not illustrated in this path diagram, family income and parental education were controlled by specifying them as correlates of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism and parenting and child peer competence. * p < .05.

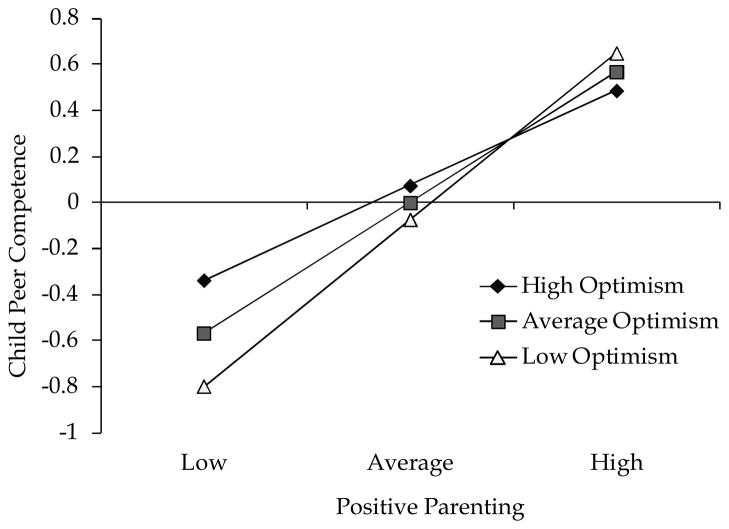

We also found the predicted interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ optimism and positive parenting, b = −0.16, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.26, −0.06]. To understand the nature of this interaction, we computed and plotted simple slopes of the relations between positive parenting and peer competence for high (1 SD above the mean), medium (at the mean), and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of mothers’/fathers’ optimism (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Figure 3 illustrates the predicted level of child peer competence as a function of mothers’/fathers’ optimism and positive parenting. We computed factor score estimates and tested the significance of the simple slopes using the steps outlined by Aiken and West (1991). Results from these analyses showed both high and low optimism slopes to be statistically significant1. In addition, Figure 3 shows the effect of optimism on peer competence is not as influential at high versus low levels of positive parenting. Contrary to expectations, we did not find that high parental optimism and positive parenting amplified one another. That is, the group with the highest levels of both positive parenting and optimism did not demonstrate the highest level of child peer competence. Rather, at low levels of positive parenting, mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were important factors moderating child peer competence. Mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were positively correlated, r = .17, SE = 0.08, p < .05, 95% CI [.01, .33], but the magnitude of this relation was small. Finally, mothers’ and fathers’ optimism explained 10% of the variance in parenting, and the main and interactive effects of optimism and parenting explained 32% of the variance in child peer competence.

Figure 3.

Child peer competence as a function of mothers’/fathers’ optimism and positive parenting.

Because the direct effects of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism on child peer competence were not significant, effects of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism on child peer competence were indirect only. Because of this, parental optimism is associated with child peer competence through its relation to positive parenting and through its moderating of effects of positive parenting on child peer competence.

Moderation by Gender of Child

To ensure the results presented above were representative of patterns for both male and female youth, we conducted post hoc analyses by fitting the proposed model separately for each gender. As noted above, multiple-group modeling cannot be performed when models include latent interaction effects. The results showed the same patterns of relations for boys and girls as in the original model. That is, the same significant and non-significant effects were replicated in both subgroups. We used a formal test of the difference between regression coefficients (Cohen et al., 2003) to test whether any of the structural relations differed significantly for boys and girls. All of these tests were non-significant (ts = 0.01 to 1.44), indicating a lack of moderation by child gender.

DISCUSSION

This investigation focused on parents’ optimism as a potential resource for the peer competence of Mexican-origin children. Specifically, we tested whether mothers’ and fathers’ dispositional optimism were associated with parenting behaviors, and whether the positive parental trait of optimism would amplify benefits of positive parenting on peer competence. As hypothesized, our analyses revealed that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism were positively associated with quality of parenting and that positive parenting, in turn, was positively associated with children’s peer competence. Moreover, we found no difference in magnitude between effects of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism on positive parenting. These results held equally for boys and girls and while controlling for family income and education.

Although we expected to find a greater benefit on peer competence when a high level of parent optimism was coupled with positive parenting, our results showed this was not the case. As illustrated in Figure 3, the benefits of being an optimistic parent were most prominent when positive parenting was low. In general, mothers and fathers who had optimistic personalities were more likely to have socially competent children, but this effect was most pronounced at low levels of parenting. Thus, high levels of parental optimism buffered children against poor parenting; at low levels of parental optimism, positive parenting was more important for engendering a high degree of child peer competence. This result suggests that optimism takes second place to parenting in terms of predicting greater child peer competence. Overall, our model is consistent with the hypothesis that positive parenting is the proximal driver of social competence and positive parenting is promoted by parents’ optimism, but longitudinal data would provide a direct test of these causal assertions.

As reported in prior research, optimistic individuals have better psychological and physical adjustment to stressful events, have better physical health, and, most importantly for our findings, have more positive social networks (Assad et al., 2007; Brissette et al., 2002; Carver et al., 2008; Kochanska et al., 2007; Segerstrom et al., 1998). Thus, optimistic parents are more likely to model behaviors (such as effective social interaction strategies) that promote peer competence, even if they rank low in their positive parenting. Another possibility is that children exposed to optimistic parents, on average, tend to develop similar kinds of optimistic attitudes themselves and benefit from the superior coping mechanisms, physical health, well-being, and social relationships that characterize optimistic people. Unfortunately, we did not collect data on children’s dispositional optimism, so this hypothesis cannot be tested. Future work should investigate whether child optimism mediates relations between parent optimism and child peer competence. A potential limitation of this investigation is that we did not include child temperament in our model or use a genetically informed design that would allow us to tease apart environmental and genetic influences. Studies have reported interactions of parenting behaviors with child temperament (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Lengua, Wolchik, Sandler, & West, 2000) and genetic makeup (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Pijlman, Mesman, & Juffer, 2008). Three-way interactions may exist among child temperament/genes, parent optimism, and parenting behaviors in affecting child peer competence. Thus, future research incorporating child temperament and genetic information could extend the results from the present study.

Our results are in line with multiple studies reporting important direct effects of maternal optimism on parenting and children’s outcomes (Brody & Flor, 1997; Brody et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2002; Kochanska et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2010). Similar to these studies, our findings suggest that optimistic mothers of Mexican origin, along with their husbands, are likely to use better parenting practices, which are associated with higher levels of child peer competence. Notably, the present investigation extends the current literature by additionally showing the benefits that optimistic fathers have in the peer competence of their children. These results show the value of testing models that consider the role of fathers as well as mothers.

We believe our model should replicate in other cultures, because many aspects of parents and their parenting are likely to function similarly across cultures. But, cultures also have their unique aspects, and familism – getting along with family members and contributing to the well-being of the family, including the extended family (Cauce & Domenech Rodriguez, 2002) – and respect, are central constructs in the Mexican-origin culture that might play a role in the current results. In other words, while instilling familism and respect in their children, optimistic parents of Mexican origin may also introduce social skills to their children that become useful with their peers when parenting is poor. Thus, future work should investigate whether any differences arise in samples from different cultural backgrounds. An additional consideration for future research is to investigate whether optimism has similar effects in single-parent families, as the personality resources of single parents might be especially important. Moreover, the causal process surrounding optimism should be further developed; variables like social support could be included in future models to assess whether they affect optimism or mediate relations between optimism and parenting, particularly using longitudinal designs.

The current results support previous theoretical models in which parental personality is expected to influence parenting beyond traditional direct effects (Belsky, 1984; Belsky & Barends, 2002; Shiner & Caspi, 2003). In our case, we found a significant moderation effect of mothers’ and fathers’ optimism on the direct effect of positive parenting on child peer competence. Furthermore, this study provides support for the association between positive parenting and child peer competence, extending to Mexican-origin families the work reported by Conger and Conger (2002) in European American families and by Conger et al. (2002) with African American families.

In addition, none of the parents’ Big Five traits was included in our model. These might also provide insightful results as previous literature reports robust links between the Big Five dimensions and parenting (Prinzie et al., 2009). Another consideration is the use of cross-sectional data; as subsequent times of measurement become available in the CFP, longitudinal models will provide information about the role of parents’ optimism and parenting practices on child peer competence across time. Longitudinal data will also allow us to test the potential reciprocal influence that children’s peer competence may have on parents’ parenting style. This is important because the cross-sectional design of this investigation hinders our ability to speak to the directionality of effects. Future research with Mexican-origin families should further examine the effects of additional aspects of mothers’ and fathers’ personality on parenting and child adjustment to provide a better understanding of how parent personality influences their families.

Even though we made efforts to reduce reporter biases in the model specification, children reported on the positive parenting factor, and the peer competence factor was based on children’s reports. Similarly, the optimism factors included only parent self reports, and parents also reported on the positive parenting factor. Thus, this overlap of rater-related method variance might have influenced the strength of the associations between positive parenting and child peer competence and dispositional optimism and positive parenting.

Studies investigating the influence of positive parental traits on parenting behaviors remain scarce. Importantly, the current study found support for the hypothesis that mothers’ and fathers’ optimism can act as moderators of the relation between parenting and child peer competence in a sample of Mexican-origin families. Other positive traits such as self-esteem, positive emotionality, gratitude, coping, and patience are likely to exert important influences on children’s outcomes via their impact on parenting. We hope the present results motivate researchers to pursue additional questions in this area of research with culturally diverse samples.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, APPLICATION, AND POLICY

Results from this study support the robust finding of positive parenting influencing the social competence of children. Above all, positive parenting practices involving warmth, affection, monitoring, and positive engagement should be employed by parents and encouraged by clinicians and policy makers. However, because parents range in their levels of positive parenting, clinicians and policy makers can try alternatives that could buffer children’s social competence from the adverse consequences of poor parenting. One such alternative is encouraging parents to be optimistic. The current investigation suggests that this personality characteristic is associated with increased positive parenting behaviors and reduced negative consequences for children in the event of poor parenting. According to this study, mothers and fathers, equally, should aim to adopt an optimistic view of life given that both parents exert influences on child social competence.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by grant DA 017902 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Rand Conger, Richard Robins, and Keith Widaman, Joint-PIs).

Footnotes

Regression equations from these analyses are available upon request from the first author.

Contributor Information

Laura Castro-Schilo, Email: castro@ucdavis.edu, Department of Psychology, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA.

Emilio Ferrer, University of California, Davis.

Zoe E. Taylor, University of California, Davis

Richard W. Robins, University of California, Davis

Rand D. Conger, University of California, Davis

Keith F. Widaman, University of California, Davis

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Assad KK, Donnellan MB, Conger R. Optimism: An enduring resource for romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:285–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Pijlman FTA, Mesman J, Juffer F. Experimental evidence for differential susceptibility: Dopamine D4 receptor polymorphism (DRD4 VNTR) moderates intervention effects on toddlers’ externalizing behavior in a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:293–300. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos DL, Finney SJ. Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–995. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Barends N. Personality and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 3. Being and becoming a parent. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 415–438. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:102–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal psychological functioning, family processes, and child adjustment in rural, single-parent, African-American families. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1000–1011. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African-American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Development. 2002;73:1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Fulford D. Self-regulatory processes, stress, and coping. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality. 3. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 725–742. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Morgan J, Rutter M, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Polo-Tomas M. Maternal expressed emotion predicts children’s antisocial behavior problems: Using monozygotic-twin differences to identify environmental effects on behavioral development. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:149–161. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras J, editor. Latino Youth and Families Facing the Future. NY: Basic Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, MacCallum RC. Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:235–259. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Developed from diverse sources for the Iowa Youth & Family Project. Ames, IA: Iowa State University; 1989a. Behavioral Affect Rating Scale (BARS) [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Developed from diverse sources for the Iowa Youth & Family Project. Ames, IA: Iowa State University; 1989b. Child Rearing Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody G. Economic pressure in African-American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mothers’ parenting, and children’s adjustment in low-income, Mexican immigrant, and Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1997;59:309–323. doi: 10.2307/353472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Perceived Competence Scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–89. doi: 10.2307/1129640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle LA, Busch EA, Warren JE. Explanatory style, dispositional optimism, and reported parental behavior. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1996;157:489–499. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1996.9914881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L. Positive parenting and child psychosocial adjustment in inner-city, single-parent, African-American families: The role of maternal optimism. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:464–481. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Widaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. doi: 10.1177/0013164494054003022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Moosbrugger H. Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika. 2000;65:457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Penney SJ, Boldt LJ. Parental personality as an inner resource that moderates the impact of ecological adversity on parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:136–150. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD. Preadolescent peer status, aggression, and school adjustment as predictors of externalizing problems in adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1350–1362. doi: 10.2307/1130747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidy MS, Guerra NG, Toro RI. Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:252–260. doi: 10.1037/a0019407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, West SG. The additive and interactive effects of parenting and temperament in predicting adjustment problems of children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:232–244. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the questions, weighting the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Oettingen G, Baltes PB. The revised control, agency, and means-ends interview (CAMI): A multi-cultural validity assessment using mean and covariance (MACS) analyses (Materialen aus der Bildungsforschung, No 49) Berlin: Max Planck Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Wen Z, Hau K. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:275–300. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder BC, Algina J. Comparison of methods for estimating and testing latent variable interactions. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:1–19. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Computer software and manual. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. Mplus user’s guide. [Google Scholar]

- Nes LS, Segerstrom SC. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:235–251. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bagwell CL. Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:306–347. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM, Pattee L. Children’s peer relations: A meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:99–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological context, and children’s adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68:908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Stams GJJM, Deković M, Reijntjes AHA, Belsky J. The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0015823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill CM, Stoep AV, McCauley E, Katon WJ. Social competence and social support as mediators between comorbid depressive and conduct problems and functional outcomes in middle school children. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:535–553. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, Coplan R, Buskirk AA, Wojslawowicz JC. Peer relationships in childhood. In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, editors. Developmental science: An advanced textbook. 5. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 469–512. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16:201–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01173489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Fahey JL. Optimism is associated with mood, coping, and immune change in response to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1646–1655. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Kerns D. Unwanted sexual activity among peers during early and middle adolescence: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:941–952. doi: 10.2307/352774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent sexual activity: An ecological, risk-factor approach. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:181–192. doi: 10.2307/352712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Landry SH, Swank PR. The influence of early patterns of positive parenting on children’s preschool outcomes. Early Education & Development. 2000;11:147–169. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1102_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Z, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD, Widaman K, Cutrona CE. Life stress, maternal optimism, and adolescent competence in single-mother, African-American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:468–477. doi: 10.1037/a0019870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Race and Hispanic origin of the foreign-born population in the United States: 2007. American Community Survey Reports. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/acs-11.pdf.

- Widaman KF, Reise SP. Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance use research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 281–324. [Google Scholar]

- Yung Y, Thissen D, McLeod LD. On the relationship between the higher-order factor model and the hierarchical factor model. Psychometrika. 1999;64:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02294531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]