Abstract

The anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) shows promise for the treatment of neuropathic pain, but for IL-10 to be clinically useful as a short-term therapeutic its duration needs to be improved. In this study, IL-10 was covalently modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG) with the goal of stabilizing and increasing protein levels in the CSF to improve the efficacy of IL-10 for treating neuropathic pain. Two different PEGylation methods were explored in vitro to identify suitable PEGylated IL-10 products for subsequent in vivo testing. PEGylation of IL-10 by acylation yielded a highly PEGylated product with a 35-fold in vitro biological activity reduction. PEGylation of IL-10 by reductive amination yielded products with a minimal number of PEG molecules attached and in vitro biological activity reductions of ~3-fold. In vivo collections of cerebrospinal fluid after intrathecal administration demonstrated that 20 kDa PEG attachment to IL-10 increased the concentration of IL-10 in the cerebrospinal fluid over time. Relative to unmodified IL-10, the 20 kDa PEG-IL-10 product exhibited an increased therapeutic duration and magnitude in an animal model of neuropathic pain. This suggests that PEGylation is a viable strategy for the short-term treatment or, in conjunction with other approaches, the long-term treatment of enhanced pain states.

Keywords: glia, interleukin-10, intrathecal delivery, neuropathic pain, PEGylation

INTRODUCTION

Neuropathic pain is a chronic condition caused by physical injury, surgery, viral infection, or chemotherapy.1 Recent evidence suggests that activated spinal cord glia play a major role in neuropathic pain2,3 by releasing proinflammatory cytokines that include interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6,4 which ultimately act to sensitize and enhance pain processing.5,6 The production of proinflammatory cytokines by activated glia, however, is subject to targeted negative-feedback suppression by interleukin-10 (IL-10).7–9 IL-10 prevents the onset of spinal mediated mechanical allodynia, the development of enhanced pain behaviors by spinal cord excitotoxic injury10 and can be used to affect the proinflammatory functions of activated glia without a direct effect on neurons.11

Systemic administration of IL-10 as a treatment for neuropathic pain is not feasible as it is too large to cross the blood-brain barrier.12 Direct intrathecal IL-10 administration is a viable option, but is not efficacious for a prolonged period due to its rapid clearance (t1/2 ~2 h) from the subarachnoid space.13 As an alternative to direct IL-10 protein administration, injection of viral and non-viral vectors that encode for the IL-10 gene have been shown to provide long-term (>30 day) therapeutic efficacy.14,15 For those conditions that necessitate a long-term treatment approach, IL-10 protein administration may be used in combination with gene therapy to eliminate the delay in therapeutic onset (24–48 h) that is typically observed following administration of the IL-10 gene.15,16 Efforts to improve intrathecal IL-10 protein administration, however, are still needed as not all neuropathies warrant the long-term therapeutic treatment that can be achieved by gene therapy.

The covalent attachment of a polymer to a protein can enhance its biodistribution and preserve its biological activity for extended periods of time when administered to a tissue. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is the most common polymer used for this modification which is known as PEGylation.17,18 In addition to increasing the half-life of a protein following administration, PEGylation can also enhance the stability of proteins encapsulated within polymeric drug delivery systems which are designed to slowly release a therapeutic over the course of days to months depending on device design.19–21 Hence, as a treatment for neuropathic pain, a PEGylated IL-10 protein would be useful as a short-term analgesic to counteract the effects of proinflammatory cytokines acutely. It may also benefit long-term therapeutic approaches, for example PEGylated IL-10 co-administered with the gene encoding for IL-10 may overcome the delay in therapeutic onset often observed with gene therapy approaches.15,16 PEGylated IL-10 may one day be useful in and of itself as a long-term treatment for neuropathic pain if encapsulated and released from a polymeric drug delivery device, which slowly releases PEGylated IL-10 over the course of months.

To develop a PEGylated IL-10 product suitable for these objectives, in this study, two PEGylation strategies for IL-10 were explored (acylation and reductive amination) with the goal of identifying an approach that minimally reduces the biological activity of the protein, increases protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and reverses neuropathic pain for a greater length of time than unmodified IL-10. Using an in vitro bioassay reductive amination was determined to better preserve the relative biological activity of PEGylated IL-10 products. Reductive amination was then used to prepare two PEGylated IL-10 products that had identical biological activities, but different molecular weights, one prepared utilizing 5 kDa PEG and the other utilizing 20 kDa PEG. These two PEGylated IL-10 products were individually injected into the CSF with the goal of identifying an effect of PEG molecular weight on the dose of IL-10 remaining in the CSF over time, as it has been shown that a higher molecular weight PEG molecule can increase the half-life of a PEGylated protein22 in the bloodstream and improve its therapeutic potential in vivo. The level of IL-10 present in the CSF was indeed greater for the higher molecular weight PEGylation product. Behavioral testing of this PEGylated IL-10 product demonstrated that it more effectively reversed neuropathic pain for a greater length of time than its unmodified counterpart, thereby validating the merits of PEGylated IL-10 both as a short-term therapeutic agent and as a potential complement to longer-term approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IL-10 PEGylation

Recombinant human interleukin-10 (IL-10) (R&D Systems, #217 IL/CF lot ET11507A) was brought to a concentration of 1.19 mg/mL in reaction buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate with 100 mM sodium chloride at a pH of 6.3. Reactions were highly reproducible and provided consistent degrees of conjugation with repetition. Reaction schematics for these two chemistries have been published previously.23 For reductive amination to attach 5 kDa PEG to IL-10, 10 mg of mPEG-ButyrALD-5000 (Nektar #082M0H01) was added to 0.658 mL of the reaction buffer as the polymer mix and 1.72 mg of sodium cyanoborohydride (Sigma-Aldrich #156159) was added to 10 mL of reaction buffer as the reducing agent mix; 125 µL of the IL-10 protein solution, 200 µL of the polymer mix, and 175 µL of the reducing agent mix were combined in a polypropylene tube and agitated at room temperature for 24 h. Identical conditions were used for 20 kDa PEGylation of IL-10 with reductive amination except that 10 mg of mPEG-ButyrALD-20K (Nektar #082M0P01) was added to 0.198 mL of reaction buffer as the polymer mix. Rat serum albumin (RSA; Accurate Chemical and Scientific #AIF5011) at a concentration of 4 mg/mL in the reaction buffer was also PEGylated under identical conditions with mPEG-ButyrALD-20K. These conditions represented a 60-fold PEG to IL-10 monomer excess and a 60-fold reducing agent to IL-10 monomer excess on a molar basis. Reactions were stopped by transferring the products to −80°C until further use.

Acylation, or NHS ester chemistry, to attach 5 kDa PEG to IL-10 was conducted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a pH of 7.4., 0.595 mg of IL-10 was added to 1 mL of PBS as the protein mix. For a 60-fold PEG to IL-10 molar excess 10 mg of mPEG-SPA-5000 (Nektar #2M4M0H01) was added to 1.012 mL of PBS as the polymer mix; 50 µL of the protein mix and 50 µL of the polymer mix were combined in a polypropylene tube and agitated at room temperature for 24 h. Reactions were stopped by transferring the products to −80°C until further use.

Prior to injections into animal models for in vivo efficacy testing PEG-20000-IL-10-amination products and PEG-20000-RSA-amination products were further prepared by exchanging into PBS at a pH of 7.4 using 3000 MWCO Microcon centrifugal filters (Millipore #42403). Concentrations were retested with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce #23227) before dilution to a final concentration in PBS. IL-10 in PBS as supplied by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, #217 IL/CF lot ET11507A) was also diluted in PBS prior to injections for behavioral assessments.

Gel electrophoresis

Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% pre-cast gels according to manufacturer recommended reagents and protocols (Bio-Rad #161–1155). Coomassie staining (Bio-Rad #161–0786) was conducted with gels that had been loaded with 8.94 µg of total protein.

Mass spectrometry

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (Voyager-DE STR, Perkin Elmer) was used to obtain mass information on the various IL-10 products; 0.5 µL samples were co-crystallized with 0.5 µL of matrix (sinapinic acid, Agilent) on gold-coated sample plates. Data were summed over 100 acquisitions in the delayed linear extraction mode with a 25 kV accelerating voltage, 50 V guide wire voltage, and a 300 ns delay.

The characterization of PEGylated IL-10 products relied upon both gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry as complementary techniques for assessing the abundance of conjugate species and determining more precise molecular weights of conjugate species, respectively. As PEGylation creates a significant hydration layer around a protein24,25 mass spectrometry is necessary to overcome the inherent limitations of hindered electrophoretic migration for PEG-proteins in SDS-PAGE26 and thereby more accurately estimate species molecular weights. Coomassie staining in SDS-PAGE, however, will equally stain all protein species based on their relative abundance while large molecular weight PEG molecules are less prone to desorption and ionization from a crystallized matrix and hence matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight is not reliably quantitative for assessing the relative species abundance of large molecular weight PEG-proteins.26 Mass spectrometry was therefore useful in identifying the molecular weights of the highly abundant product species observed in SDS-PAGE, and exhibited an increased sensitivity for the detection of trace species, but SDS-PAGE, within in its limits of detection, was relied upon to make qualitative statements about the relative abundance of the mass spectrometry verified conjugates with different molecular weights due to the limitations and appropriate interpretation of the two complementary techniques.

In vitro biological activity assessments

Complete medium for the murine mast cell line (MC/9) consisted of 10% FBS (heat-inactivated, VWR #16777-538), 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma #M7522), 6 mM l-glutamine (VWR #45000-676) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% Rat T-STIM (BD #354115). Incomplete medium was made by replacing Rat T-STIM with additional Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium. Healthy cells at a density of 0.75 to 1.0 × 106 cells/mL were seeded into incomplete medium containing 10 pg/mL of IL-4 (R&D Systems #404-ML) and IL-10 products over a range of 0.03 to 60 ng/mL of IL-10 (total protein basis) in 96-well vee-bottom tissue culture plates (Sarstedt #83.1838). Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 h and the plates were then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min to pellet the cells. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and 100 µL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% TritonX-100) was added to each well. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 10 min and transferred to ice to prevent further product degradation.

A CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega #G7571) was then used to determine the concentration of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) according to manufacturer recommended reagents and protocols. The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) value along with 95% confidence intervals and the goodness of fit parameter (R2) were determined using GraphPad Prism 5 software using a nonlinear regression of a dose-response stimulation curve with shared values for the baseline and maximum responses.

Intrathecal injections

All animal procedures were in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado at Boulder and NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publication #85-23 Rev. 1985) were also observed. Pathogen-free adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were used in all experiments. Rats (250–275 g at the time of arrival; Harlan Labs, Madison, WI) were housed in temperature (23°C ± 3°C) and light (12:12 light:dark; lights on at 0700 h) controlled rooms with standard rodent chow and water available ad libitum. The route of drug delivery for all experiments was intrathecal (sub-dural, peri-spinal) and took 2–3 min to complete. An acute catheter application method under brief isoflurane anesthesia (1.5–2.0% volume in oxygen) was employed, as described previously,14 to inject IL-10 products at the level of the lumbosacral enlargement.

In vivo CSF collections and analysis

At pre-determined time points after intrathecal injections (0.5, 2, 4, and 24 h) lumbosacral (lumbar) CSF samples were collected under isoflurane anesthesia,4 after which point the rats were cervically dislocated; 15 µL injection volumes of products at total protein concentrations of 0.298 µg/µL in reaction buffer (4.5 µg total protein) were administered to each animal and CSF was collected from six different animals at each time point. CSF samples were immediately transferred to liquid nitrogen and samples were subsequently stored at −80°C for further analysis. An ELISA development kit with color substrates (R&D Systems #DY217B and #DY999) was used for the quantitative detection of IL-10 according to manufacturer recommended reagents and protocols, and individual conjugate products at known concentrations were used to generate the standard curves used for the detection of each conjugate product in the CSF. Area under the CSF concentration curve values were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule for numerical approximation from the detected CSF concentration values at each condition over time. The administration dose used in these studies was higher than the dose used for the in vivo behavioral assessments to increase the accuracy of product detection over time.

Chronic-constriction injury surgery and behavioral assessment of mechanical allodynia

Chronic-constriction injury (CCI) was performed under isoflurane anesthesia (1.5–2.0% volume in oxygen) by loosely tying four chromic gut sutures around the gently isolated sciatic nerve in the left hindleg at mid-thigh level as described previously.13,27 Behavioral testing for bilateral mechanical allodynia that develops after neuropathy produced by CCI within the sciatic and saphenous innervation area of the hindpaws was also conducted as described previously13 for six rats at each condition. Briefly, a series of calibrated Semmes-Weinstein monofilament fibers (von Frey hairs; Stoelting) were applied to the left and right hindpaws to elicit paw-withdrawal responses. The 10 stimuli fibers are calibrated on a log-stiffness scale, which produce a logarithmically graded slope where the force in mg equals the antilog of the stiffness divided by 10. Data are presented as the 50% paw-withdrawal threshold (grams) and the log10 transformation of that value as log10 (milligrams × 10). The range of values for the 50% paw-withdrawal thresholds and the log-stiffness values (parenthesis) are 0.407 (3.61), 0.692 (3.84), 1.202 (4.08), 1.479 (4.17), 2.041 (4.31), 3.630 (4.56), 5.495 (4.74), 8.511 (4.93), 11.749 (5.07), and 15.136 (5.18). Assessments were made prior to CCI surgery (baseline), at days 3 and 10 after CCI surgery, and at indicated times after intrathecal drug injections. The behavioral response patterns, indicated by the number of non-withdrawal and withdrawal responses, were used to calculate the 50% paw-withdrawal threshold (absolute threshold), by fitting a Gaussian integral psychometric function using a maximum-likelihood fitting method.4,28 During behavioral assessments for mechanical allodynia, the tester was blind with respect to the treatment groups, 14 µL injection volumes at total protein concentrations of 0.141 µg/µL in PBS (2.0 µg total protein) were used for in vivo behavioral assessments, which dosage was targeted to facilitate an appropriate therapeutic level for the sensitive assessment of allodynic reversal while avoiding the ceiling effects of higher dosages.

RESULTS

Product characterization

Two different PEGylation strategies were utilized; acylation with a 5000 Da molecular weight PEG molecule (PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation) was used to target accessible amine groups, while reductive amination with two different molecular weight molecules (5000 Da and 20,000 Da PEG molecules; PEG-5000-IL-10-amination and PEG-20000-IL-10-amination) was used to preferentially target the N-terminal α-amine group. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was then conducted to verify conjugation by the different approaches (Fig. 1). The PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product did not contain detectable unmodified IL-10, it exhibited faint detection of secondary conjugate (two PEG molecule attachments) and multiple higher order (greater than three PEG molecule attachments) conjugate species [Fig. 1(a)]. The PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product contained detectable unreacted IL-10 in addition to primary (one PEG molecule attachment) and secondary conjugate species (two PEG molecule attachments) [Fig. 1(b)]. The PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product also contained high levels of primary and secondary conjugate species in addition to unreacted IL-10 [Fig. 1(c)]. It should be noted that the PEG-20000 species present in the mixtures consistently distorted banding patterns in the lanes of 10% polyacrylamide gels due to the large molecular weight of the PEG molecule.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE for the detection of PEG-IL-10 product species using coomassie staining. (a) Lane 1: Mw Marker, Lane 2: PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product. (b) Lane 1: Mw Marker, Lane 2: unmodified IL-10, Lane 3: PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product. (c) Lane 1: Mw Marker, Lane 2: unmodified IL-10, Lane 3: PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product. 1° indicates primary conjugate, 2° indicates secondary conjugate and so forth.

Although SDS-PAGE provided insight into the formation of primary, secondary, and higher order conjugate species after PEGylation, the covalent attachment of PEG significantly slows the rate of protein migration in a porous matrix, which renders molecular weight determination by SDS-PAGE inaccurate.24 Mass spectrometry was subsequently used to obtain a more accurate molecular weight for each conjugate species in the products and verify the conclusions for the number of PEG molecules attached to IL-10 for the various species produced. Analysis of the unreacted PEG products demonstrated that the PEG-5000 molecule used for acylation exhibited a nominal molecular weight of 5.84 kDa, that the PEG-5000 molecule used for amination exhibited a nominal molecular weight of 5.81 kDa and that the PEG-20000 molecule used for amination exhibited a nominal molecular weight of 21.7 kDa, with inherent polydispersities (data not shown).

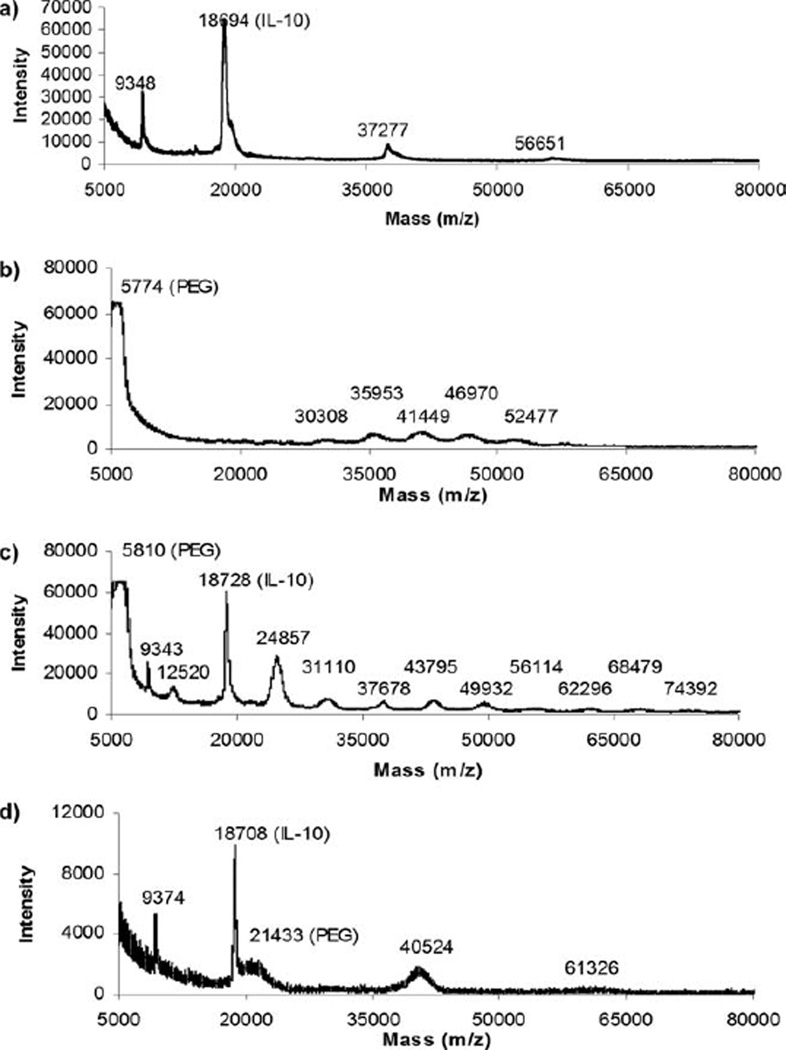

The unmodified recombinant human interleukin-10 (IL-10) used for conjugation displayed large peaks at 9.35 kDa, 18.7 kDa, 37.3 kDa, and a small peak at 56.6 kDa [Fig. 2(a)]. The 18.7 kDa and 37.3 kDa peaks were attributed to IL-10 monomer and dimer, respectively, as the mature human IL-10 is an 18-kDa7,29 protein containing 160 amino acid residues and two intramolecular disulphide bonds,29–32 which exists in solution as a noncovalent homodimer.7,29,31,32 The 56.6 kDa peak showed that there was a slightly detectable trimeric association after co-crystallization of the protein in a sinapinic acid matrix, and the 9.35 kDa peak was the doublet species of the 18.7 kDa peak characteristic of matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight analysis.

Figure 2.

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry of (a) unmodified IL-10, (b) PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product, (c) PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product, and (d) PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product.

Mass spectrometry of the PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product [Fig. 2(b)] detected peaks at 5.7, 30.3, 36.0, 41.4, 47.0, and 52.5 kDa. The peak at 5.7 kDa represented unreacted PEG-5000, while the remaining peaks represented the successive attachment of PEG molecules to the IL-10 protein with the first detected peak at 30.3 kDa representing the attachment of two PEG molecules to IL-10 (secondary conjugate). Peaks for the 18.7 kDa IL-10 monomer as well as single PEG molecule attachment (primary conjugate) to IL-10 for the PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product were not detected either by SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry, which verified the preferential attachment of multiple PEG molecules to IL-10 with this reaction chemistry and also indicated that the highly abundant quaternary and quinary species observed after SDS-PAGE represented the attachment of four or five respective PEG molecules to IL-10.

Mass spectrometry of the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product [Fig. 2(c)] detected peaks at 5.81, 9.34, 12.5, 18.7, 24.8, and 31.1 kDa and smaller peaks at 37.7, 43.8, 49.9, 56.1, 62.3, 68.5, and 74.4 kDa. The 5.81 peak represented unreacted PEG-5000, and the 9.34 and 18.7 kDa peaks represented unreacted IL-10. The 24.8 peak was attributed to the covalent attachment of one PEG molecule to IL-10 with the characteristic doublet species at 12.5 kDa. The rest of the detected peaks successively increased in the increments of 5.8–6.5 kDa, which represented the successive attachment of an increasing number of polydisperse PEG molecules to IL-10. While the coomassie stain after SDS-PAGE did not detect these trace higher order conjugate species due to limitations in sensitivity, the major peaks detected by mass spectrometry are consistent with the two major bands observed by SDS-PAGE and reflect the attachment of one and two PEG molecules to IL-10. Mass spectrometry of the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product detected peaks at 9.37, 18.7, 21.4, 40.5, and 61.3 kDa [Fig. 2(d)]. The 9.37 and 18.7 kDa peaks represented unreacted IL-10 and the 21.4 kDa peak represented unreacted PEG-20000. The 40.5 and 61.3 peaks (representing primary and secondary conjugate species) were therefore attributed to the covalent attachment of one and two respective PEG molecules to IL-10.

Overall, these reaction conditions, which all started with the same molar excess of PEG to IL-10, generated PEG-IL-10 product mixtures with different resultant characteristics. The PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product exhibited significant amounts of higher order conjugates (> three PEG molecules attached) with no detectable primary conjugate and unreacted IL-10, where quaternary conjugate (four PEG molecules attached) was the most abundant species detected by mass spectrometry and SDS-PAGE. The majority of the PEGylated species for this product mixture fell in a mass range of 36.0 and 47.0 kDa. The PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product was composed of a high amount of primary conjugate (one PEG molecule attached), followed by secondary conjugate (two PEG molecules attached) and unreacted IL-10, where the most abundant species (primary conjugate) was 24.8 kDa. The PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product was also composed of a high amount of primary conjugate and a lesser amount of secondary conjugate with unreacted IL-10, where the most abundant species (primary conjugate) was 40.5 kDa. The PEG-5000-acylation and PEG-20000-amination products were primarily composed of species with similar molecular weights (~40 kDa), but different numbers of PEG molecule attachments, while the PEG-5000-amination and PEG-20000-amination products were primarily composed of species with different overall molecular weights (25 kDa vs. 40 kDa) but the same number of PEG molecules attached (~1 PEG molecule per protein). The biological activity of these product mixtures which differed by either molecular weight or the number of PEG molecules was then assessed in vitro to identify the best candidates for subsequent in vivo testing and therapeutic efficacy assessment in animal models of neuropathic pain.

In vitro biological activity testing

In the literature it has been shown that PEGylation can result in a biological activity reduction, due to steric hindrance of the attached PEG, however, this loss in bioactivity is often compensated for by an improvement in protein-half in vivo.33,34 In this study, the goal was to minimize this biological activity loss while preserving the therapeutic benefits of PEGylation in vivo. The relative in vitro biological activities of the various IL-10 products were assessed by determining the half-maximal concentration (EC50) of a product necessary to stimulate proliferation of the MC/9 murine mast cell line (Fig. 3). Previous findings have indicated that IL-10 is sensitive to reducing agents,31 however, exposure of IL-10 to the reducing agent concentrations used in these studies did not significantly alter the EC50 of IL-10 (data not shown). The EC50 value of unmodified IL-10 was 1.032 ng/mL. The PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product had an EC50 value of 35.47 ng/mL for an EC50 increase of ~35-fold relative to unmodified IL-10. The EC50 values of the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination and PEG-20000-IL-10-amination products were 3.190 and 3.257 ng/mL, respectively. This represented an EC50 increase of only 3-fold for both of the reductive amination products relative to unmodified IL-10.

Figure 3.

In vitro dose-response of MC/9 cells to IL-10 products. (a) Proliferation of cells measured by total ATP concentrations in cell culture lysates relative to IL-10 product concentrations in the growth medium, error bars are ± standard error of the mean and (b) EC50 values and 95% confidence intervals for IL-10 products.

In vivo CSF collection after intrathecal administration

The PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product with a significantly reduced in vitro biological activity relative to the other conjugate products was eliminated from further testing to minimize the use of animals, while the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination and PEG-20000-IL-10-amination products, which exhibited relatively preserved in vitro biological activities but different molecular weight PEG molecule attachments, were administered intrathecally to surgically naïve animals. CSF samples were collected at various time points after administration and ELISA was used to assess the concentration of the IL-10 products over time in the intrathecal space and to estimate the amount of IL-10 that would remain in the CSF circulation over a 24 h time interval, represented by the area under a graph of CSF concentration versus time (Table I). The PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product did not exhibit a significantly increased concentration relative to the unmodified IL-10 over time, and its calculated area under the CSF concentration curve was 29.32 ± 1.85 µg h/mL compared to 28.10 ± 5.72 µg h/mL for unmodified IL-10. The PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product exhibited elevated concentrations relative to unmodified IL-10 at all of the analyzed time points with a calculated area under the CSF concentration curve of 97.51 ± 16.72 µg h/mL, for an improvement of over 3-fold compared to both IL-10 and the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product.

TABLE I.

In Vivo Assessment of IL-10 Product Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentrations (µg/mL ± STD Error of the Mean) Over Time After Intrathecal Administration

| Time (h) | Unmodified IL-10 (µg/mL) |

PEG-5000-IL-10- Amination (µg/mL) |

PEG-20000-IL-10- Amination (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 9.72 ± 3.79 | 9.07 ± 3.01 | 44.20 ± 6.08** |

| 2 | 3.14 ± 1.29 | 7.91 ± 2.22 | 6.19 ± 0.78* |

| 4 | 1.24 ± 0.53 | 0.59 ± 0.16 | 4.35 ± 1.58 |

| 24 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.06** |

| AUC (µg h/mL) | 28.10 ± 5.72 | 29.32 ± 1.85 | 97.51 ± 16.72 |

Area under the CSF concentration time curve values were calculated from the detected IL-10 concentrations at each time point using the linear trapezoidal rule of numerical approximation.

Indicates p < 0.005 compared to time-matched unmodified IL-10.

Indicates p < 0.05 compared to time-matched unmodified IL-10 (one-way unequal variance t-tests on a 95% confidence interval), ± error values are standard error of the mean.

In vivo behavioral assessments

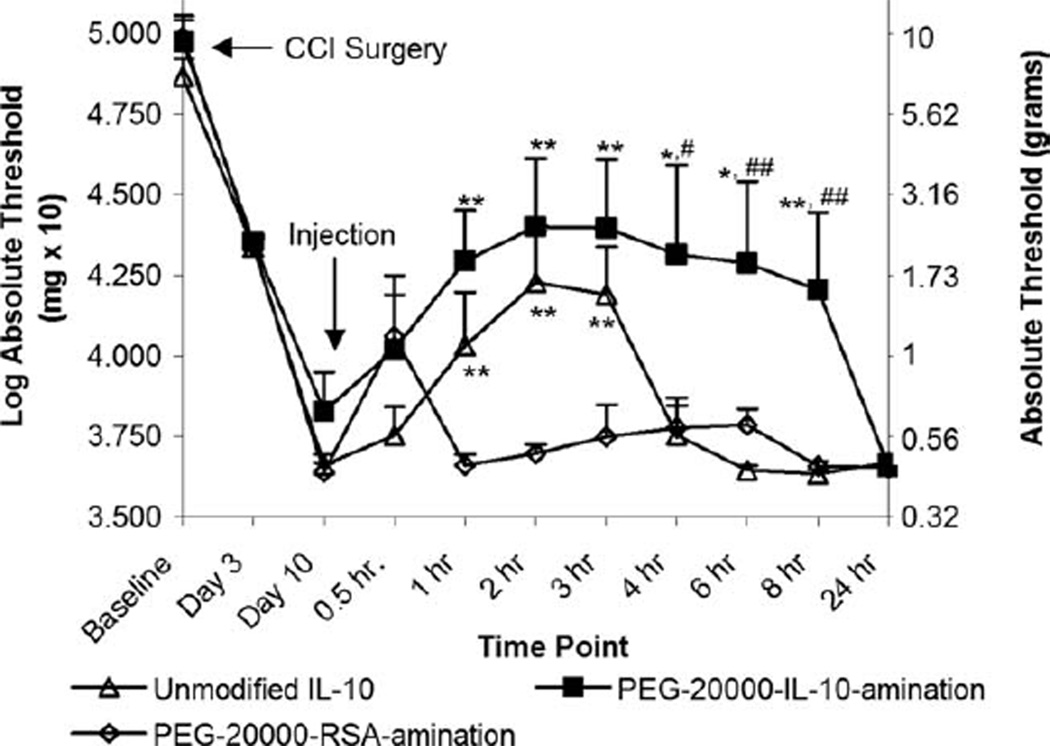

Because of its enhanced performance relative to the PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation and the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination products after preliminary testing, the therapeutic efficacy of the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product relative to unmodified IL-10 for the short-term treatment of enhanced pain states was then assessed (Fig. 4). It has been shown previously that neuropathy leads to heightened sensitivity to light mechanical touch, known as allodynia, and that bilateral allodynia develops after neuropathy produced by CCI.14,35,36 Unmodified IL-10, the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product and a PEG-20000-RSA-amination product (as a vehicle control) were intrathecally administered to animal models and the reversal of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia was measured over time. The administered dosages of IL-10 (2.0 µg on a total protein basis) were selected to facilitate only a partial reversal of allodynia from unmodified IL-10 (based on preliminary doseresponse testing) so that potential enhancements in both the duration and magnitude of allodynic reversal after PEGylation could be assessed. The selected PEG-IL-10 product and unmodified IL-10 both reduced the effects of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia for 3 h after intrathecal administration relative to PEG-RSA (p < 0.05) for a full preservation of IL-10 therapeutic efficacy after PEGylation. Additionally, PEGylated IL-10 increased the magnitude of reversal relative to unmodified IL-10 at all of the measured time points and increased the duration of the therapeutic effects from 3 h to 8 h for a stronger reversal that persisted for a longer period of time.

Figure 4.

Assessment of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia after intrathecal administration of unmodified IL-10, PEG-20000-IL-10-amination, and PEG-20000-RSA-amination. Intrathecal administration was conducted 10 days after CCI surgery to induce bilateral mechanical allodynia; 50% absolute withdrawal threshold responses to Von Frey fibers were the average of ipsilateral and contralateral hindpaws, **indicates p value < 0.05 compared to time-matched PEG-20000-RSA-amination, *indicates p value < 0.1 compared to time-matched PEG-20000-RSA-amination, ##indicates p value < 0.05 compared to time-matched unmodified IL-10, #indicates p value < 0.05 compared to time-matched unmodified IL-10 (one-way unequal variance t-tests on a 95% confidence interval), error bars are + standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

IL-10 is considered to be the most powerful antiinflammatory cytokine that can counter-regulate the production and function of proinflammatory cytokines on multiple levels.7,37 As blockage of any one proinflammatory cytokine (including tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6) can be offset by the actions of the others for a continuation of inflammation and pain facilitation, the ability of IL-10 to regulate multiple proinflammatory cytokines is particularly advantageous.38,39 These studies have demonstrated that IL-10 modification by the covalent attachment of large molecular weight PEG molecules (20,000 kDa) by reductive amination not only enables substantial in vitro biological activity retention and significantly improves its concentration over time in the CSF, but also enhances its relevance as a potent anti-inflammatory agent for the short-term and rapid reversal of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia. Moreover, the efficacy of PEG-IL-10 in reducing neuropathic pain is an indicator that it down-regulated proinflammatory cytokines, as the link between proinflammatory cytokines and neuropathic pain has been clearly established.8,40

The acylation approach resulted in the formation of IL-10 conjugates containing four attached PEG molecules, corresponding to a molecular weight of ~40 kDa. In vitro biological activity assessment of the PEG-5000-IL-10-acylation product demonstrated that this PEGylation approach resulted in a mixture with a significantly reduced biological activity relative to unmodified IL-10 (35-fold reduction). The reduction in biological activity observed was most likely not due to an overall increase in the molecular weight of the IL-10 product as the biological activity of a product of similar molecular weight (the PEG-20000-IL-10 amination product) was reduced only 3-fold when tested in vitro. Instead, the reduction in biological activity observed following the acylation reaction is likely due to the fact that more PEG molecules are attached to amine residues within the protein, thereby increasing the likelihood for potential binding site disruptions,33,34 which could decrease biological activity. Because of its substantial in vitro biological activity reduction, and to minimize the use of animals, this product was eliminated from subsequent in vivo testing.

In vitro biological activity assessments indicated that IL-10 PEGylation by reductive amination substantially preserved its biological activity with an EC50 increase of only 3-fold. Marginal in vitro biological activity reductions after PEGylation are consistent with the findings from other PEG-proteins, and these losses are often compensated for by significant improvements in protein half-life in vivo.18,41 As the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination and PEG-5000-IL-10-amination products both exhibited similar degrees of conjugation and similar EC50 values (no statistical difference from one another), the molecular weight of the attached PEG molecule was not found to significantly impact in vitro biological activity. With reductive amination, the primary conjugate was the most abundant species in the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination and PEG-5000-IL-10-amination products, which represents the attachment of one PEG molecule to IL-10. Previous findings with N-terminal directed PEGylation by reductive amination with other proteins have shown that the primary conjugate species generated by reductive amination consists primarily of PEG covalently bonded to the N-terminus of a protein,42–46 which is advantageous for IL-10, as its N-terminal region is not responsible for its cytokine inhibitory properties47 or receptor binding potential.37,48

CSF collections on the 5 kDa and 20 kDa PEG-IL-10 products generated by reductive amination were conducted to determine if PEGylation would increase the level of protein present in the lumbar region of the CSF over time following intrathecal injection and if increasing the molecular weight of the attached PEG species would further improve protein levels in the CSF. It should be noted that these experiments focused on the lumbar region near the injection site, but that the timescale and relative amount of conjugate product diffusion into the entire CSF volume were not assessed herein. The PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product exhibited significantly increased concentrations in the lumbar CSF over time relative to the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product and unmodified IL-10. While clearance of conjugate products to the bloodstream via bulk flow is likely a major factor in protein removal,23 the enhance improvements upon PEGylation are most likely be attributed to the benefits of PEGylation in shielding a protein against enzymatic degradation and antigenic determinants.25,49 These agents are less abundant in the CSF than in the bloodstream, but there is increasing evidence of serine proteases and antigenic determinants in the CSF.50,51 While the ELISA method may not entirely discriminate between degraded and nondegraded products, it has been shown that PEGylation can shield against degradation and the increased shielding effect of the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product relative to the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product against proteolytic and antigenic determinants is likely due to the increased hydrodynamic and steric effects of the 20 kDa PEG relative to the 5 kDa PEG attached to IL-10.24,25,34,52 The significantly increased in vivo stability realized by increasing the molecular weight of the attached PEG molecule is also consistent with prior results in the bloodstream for other proteins including BDNF,53 octreotide,44 and EGF22 but this is the first analysis of the effect in the CSF.

The therapeutic efficacy of the PEG-20000-IL-10-amination product was tested in vivo because of its improved CSF concentration over time relative to the PEG-5000-IL-10-amination product. The efficacy of IL-10 in reversing CCI-induced allodynia is consistent with prior studies of this neuropathic pain model14,15 and in this study, a dose of IL-10 that provided partial reversal of allodynia was purposefully chosen so that differences in the magnitude and duration of pain relief when a PEGylated protein is delivered could be observed. At all time points, the magnitude of the reversal was greater in animals receiving PEGylated IL-10 relative to unmodified IL-10. In addition, the duration of reversal was greater in animals receiving PEGylated IL-10 relative to unmodified IL-10. Animals receiving unmodified IL-10 returned to allodynia 3 h after administration whereas animals receiving PEGylated IL-10 remained reversed through 8 h. They did return to allodynia by 24 h, but the exact time point that the therapeutic effect ended was not determined due to inherent experimental limitations, as accurate behavioral testing cannot interfere with habituated light: dark cycles for the animals.

The increased exposure of cells to therapeutic levels of IL-10 in the CSF over time that is observed when PEGylated protein is injected into the CSF may sustain the ability of IL-10 to block signals responsible for the persistence of mechanical allodynia. Prior work has demonstrated that the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 is involved in maintaining persistent mechanical allodynia, and that temporarily blocking the effects of this cytokine causes a temporary reversal of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia.16 The ability of PEGylated IL-10 to reverse the effects of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia is attributed to its ability to down-regulate the effects of this and other proinflammatory cytokines, and is also consistent with prior work demonstrating that allodynic reversal from IL-10 protein administration corresponds to its concentration profile in the CSF13 and that IL-10 levels in the CSF are inversely correlated with pain symptoms.8

Although the effects of PEG-IL-10 protein administration were still relatively short-term, the effects were also rapid as therapeutic onset occurred within 1 h of administration. An acute intrathecal injection via percutaneous lumbar puncture is similar to current clinical practices in spinal pain intervention and exhibits a good safety record.54 Additionally, IL-10 does not have a direct effect on neurons,11 does not alter baseline responsivity to normal pain,13 and can delay the development of morphine tolerance and withdrawal-induced pain facilitation.55 Consequently, direct IL-10 administration still presents unique advantages relative to currently available short-term pain treatment approaches. PEGylated IL-10 with preserved and enhanced short-term efficacy for the reversal of mechanical allodynia would likely improve its ability to function in other diverse therapeutic paradigms where acute IL-10 administration has been shown to suppress the development of spinal mediated pain facilitation.10,56–59 Protein PEGylation additionally imparts several advantages for controlled delivery systems including improved stability during and after polymeric encapsulation21,44 along with improved encapsulation and release from these systems.19,20,60 If long-term treatments are necessary, a gene therapy approach, in which viral14 and non-viral15 methods of delivery are employed to deliver the gene encoding for IL-10, can be utilized, however, in this approach, there is a 24–48 period between administration and therapeutic onset. PEGylated IL-10 with an improved short-term efficacy and compatibility with polymeric delivery systems could potentially augment long-term therapy as an early-onset therapeutic strategy in combination with late-onset methods to facilitate short- and long-term therapeutic treatments in a single intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions from this set of experiments indicate that PEGylated IL-10 exhibits potential for use in the therapeutic treatment of enhanced pain states. The in vitro biological activity of IL-10 was substantially retained after PEGylation by reductive amination, and increasing the molecular weight of the attached PEG molecule increased protein levels in the CSF over time. PEGylated IL-10 exhibited enhanced efficacy for the reversal of CCI-induced mechanical allodynia. PEGylated IL-10, therefore, offers potential as an improved therapeutic to reverse enhanced pain states in short-term treatment approaches, and may be useful in combination with controlled release applications or alternative long-term treatment approaches that currently exhibit a delayed therapeutic onset. The ability to alter the size, structure, and functionality of the covalently attached PEG molecules to increase the potential of IL-10 as a stand-alone or combinatorial therapeutic with other delivery approaches is an especially promising avenue for future work with PEGylated IL-10 to enhance the clinical relevance of this therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Avigen Inc. (Alameda, CA) for the gift of activated mPEG molecules, IL-10, MC/9 cell culture reagents, and the Sprague-Dawley rats used in this work.

References

- 1.Miller G. The dark side of glia. Science. 2005;308:778–781. doi: 10.1126/science.308.5723.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suter MR, Wen YR, Decosterd I, Ji RR. Do glial cells control pain? Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:255–268. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mika J. Modulation of microglia can attenuate neuropathic pain symptoms and enhance morphine effectiveness. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milligan ED, O’connor KA, Nguyen K, Armstrong CB, Twining C, Gaykema RPA, Holguin A, Martin D, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Intrathecal HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 induces enhanced pain states mediated by spinal cord proinflammatory cytokines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2808–2819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02808.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve AJ, Patel S, Fox A, Walker K, Urban L. Intrathecally administered endotoxin or cytokines produce allodynia, hyperalgesia and changes in spinal cord neuronal responses to nociceptive stimuli in the rat. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:247–257. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oka T, Aou SJ, Hori T. Intracerebroventricular injection of interluekin-1-beta enhances nociceptive neuronal responses of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis in rats. Brain Res. 1994;656:236–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore KW, Malefyt RD, Coffman RL, O’garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backonja MM, Coe CL, Muller DA, Schell K. Altered cytokine levels in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of chronic pain patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csuka E, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Lenzlinger PM, Joller H, Trentz O, Kossmann T. IL-10 levels in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: relationship to IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta 1 and blood-brain barrier function. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;101:211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plunkett JA, Yu CG, Easton JM, Bethea JR, Yezierski RP. Effects of interleukin-10 (IL-10) on pain behavior and gene expression following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;168:144–154. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledeboer A, Wierinckx A, Bol J, Floris S, De Lavalette CR, De Vries HE, Van Den Berg TK, Dijkstra CD, Tilders FJH, Van Dam AM. Regional and temporal expression patterns of interleukin-10, interleukin-10 receptor and adhesion molecules in the rat spinal cord during chronic relapsing EAE. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136:94–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V, Pan WH. Interleukin-10 as a CNS therapeutic: The obstacle of the blood-brain/blood-spinal cord barrier. Mol Brain Res. 2003;114:168–171. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milligan ED, Langer SJ, Sloane EM, He L, Wieseler-Frank J, O’connor K, Martin D, Forsayeth JR, Maier SF, Johnson K, Chavez RA, Leinwand LA, Watkins LR. Controlling pathological pain by adenovirally driven spinal production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2136–2148. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Langer SJ, Cruz PE, Chacur M, Spataro L, Wieseler-Frank J, Hammack SE, Maier SF, Flotte TR, Forsayeth JR, Leinwand LA, Chavez R, Watkins LR. Controlling neuropathic pain by adeno-associated virus driven production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10. Mol Pain. 2005;1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Langer SJ, Hughes TS, Jekich BM, Frank MG, Mahoney JH, Levkoff LH, Maier SF, Cruz PE, Flotte TR, Johnson KW, Mahoney MM, Chavez RA, Leinwand LA, Watkins LR. Repeated intrathecal injections of plasmid DNA encoding interleukin-10 produce prolonged reversal of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2006;126:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milligan ED, Soderquist RG, Malone SM, Mahoney JH, Hughes TS, Langer SJ, Sloane EM, Maier SF, Leinwand LA, Watkins LR, Mahoney MJ. Intrathecal polymer-based interleukin-10 gene delivery for neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:293–308. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X07000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts MJ, Bentley MD, Harris JM. Chemistry for peptide and protein PEGylation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:459–476. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailon P, Berthold W. Polyethylene glycol-conjugated pharmaceutical proteins. Pharm Sci Technol Today. 1998;1:352–356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinds KD, Campbell KM, Holland KM, Lewis DH, Piche CA, Schmidt PG. PEGylated insulin in PLGA microparticles. In vivo and in vitro analysis. J Control Release. 2005;104:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pean JM, Boury F, Venier-Julienne MC, Menei P, Proust JE, Benoit JP. Why does PEG 400 co-encapsulation improve NGF stability and release from PLGA biodegradable microspheres? Pharm Res. 1999;16:1294–1299. doi: 10.1023/a:1014818118224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diwan M, Park TG. Pegylation enhances protein stability during encapsulation in PLGA microspheres. J Control Release. 2001;73:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H, Jang IH, Ryu SH, Park TG. N-terminal site-specific mono-PEGylation of epidermal growth factor. Pharm Res. 2003;20:818–825. doi: 10.1023/a:1023402123119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soderquist RG, Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Harrison JA, Douvas KK, Potter JM, Hughes TS, Chavez RA, Johnson K, Watkins LR, Mahoney MJ. PEGylation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor for preserved biological activity and enhanced spinal cord distribution. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91:719–729. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhalluin C, Ross A, Leuthold LA, Foser S, Gsell B, Muller F, Senn H. Structural and biophysical characterization of the 40 kDa PEG-interferon-alpha(2a) and its individual positional isomers. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:504–517. doi: 10.1021/bc049781+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molineux G. Pegylation: Engineering improved biopharmaceuticals for oncology. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:3S–8S. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.9.3s.32886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veronese FM. Peptide and protein PEGylation: A review of problems and solutions. Biomaterials. 2001;22:405–417. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milligan ED, Mehmert KK, Hinde JL, Harvey LO, Martin D, Tracey KJ, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia produced by intrathecal administration of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein, gp120. Brain Res. 2000;861:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pletnev S, Magracheva E, Wlodawer A, Zdanov A. A model of the ternary complex of interleukin-10 with its soluble receptors. BMC Struct Biol. 2005;5 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X. Current Drug Targets, Immune, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. Hilversum, Netherlands: Bentham Science Publishers; 2005. Boosting Interleukin-10 Production; pp. 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter MR, Nagabhushan TL. Crystal-structure of interleukin-10 reveals an interferon gamma-like fold. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12118–12125. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zdanov A. Structural features of the interleukin-10 family of cytokines. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3873–3884. doi: 10.2174/1381612043382602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark R, Olson K, Fuh G, Marian M, Mortensen D, Teshima F, Chang S, Chu H, Mukku V, Canova-Davis E, Somer T, Cronin M, Winkler M, Wells JA. Long-acting growth hormones produced by conjugation with polyethylene glycol. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21969–21977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koumenis IL, Shahrokh Z, Leong S, Hsei V, Deforge L, Zapata G. Modulating pharmacokinetics of an anti-interleukin-8 F(ab‘)(2) by amine-specific PEGylation with preserved bioactivity. Int J Pharmaceutics. 2000;198:83–95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paulson PE, Casey KL, Morrow TJ. Long-term changes in behavior and regional cerebral blood flow associated with painful peripheral mononeuropathy in the rat. Pain. 2002;95:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paulson PE, Morrow TJ, Casey KL. Bilateral behavioral and regional cerebral blood flow changes during painful peripheral mononeuropathy in the rat. Pain. 2000;84:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00216-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasche C, Grundtner P, Zwirn P, Reinisch W, Shaw SH, Zdanov A, Sarma U, Williams LM, Foxwell BM, Gangl A. Novel variants of the IL-10 receptor 1 affect inhibition of monocyte TNF-alpha production. J Immunol. 2003;170:5578–5582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opal SM, Depalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;117:1162–1172. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyen JRR, Ye SM, Finck BN, Johnson RW. Interleukin (IL)-10 inhibits IL-6 production in microglia by preventing activation of NF-kappa B. Mol Brain Res. 2000;77:138–147. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ledeboer A, Jekich BM, Sloane EM, Mahoney JH, Langer SJ, Milligan ED, Martin D, Maier SF, Johnson KW, Leinwand LA, Chavez RA, Watkins LR. Intrathecal interleukin-10 gene therapy attenuates paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in dorsal root ganglia in rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:686–698. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esposito P, Barbero L, Caccia P, Caliceti P, D’antonio M, Piquet G, Veronese FM. PEGylation of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GRF) analogs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(03)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basu A, Yang K, Wang ML, Liu S, Chintala R, Palm T, Zhao H, Peng P, Wu DC, Zhang ZF, Hua J, Hsieh MC, Zhou J, Petti G, Li XG, Janjua A, Mendez M, Liu J, Longley C, Zhang Z, Mehlig M, Borowski V, Viswanathan M, Filpula D. Structure-function engineering of interferon-beta-1b for improving stability, solubility, potency, immunogenicity, and pharmacokinetic properties by site-selective mono-PEGylation. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:618–630. doi: 10.1021/bc050322y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards CK, Martin SW, Seely J, Kinstler O, Buckel S, Bendele AM, Cosenza ME, Feige U, Kohno T. Design of PEGylated soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type I (PEG sTNF-RI) for chronic inflammatory diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1315–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(03)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Na DH, Lee KC, Deluca PP. PEGylation of octreotide: II. Effect of N-terminal mono-PEGylation on biological activity and pharmacokinetics. Pharm Res. 2005;22:743–749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee H, Park TG. Preparation and characterization of mono-PEGylated epidermal growth factor: Evaluation of in vitro biologic activity. Pharm Res. 2002;19:845–851. doi: 10.1023/a:1016113117851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arduini RM, Li ZF, Rapoza A, Gronke R, Hess DM, Wen DY, Miatkowski K, Coots C, Kaffashan A, Viseux N, Delaney J, Domon B, Young CN, Boynton R, Chen LL, Chen LQ, Betzenhauser M, Miller S, Gill A, Pepinsky RB, Hochman PS, Baker DP. Expression, purification, and characterization of rat interferon-beta, and preparation of an N-terminally PEGylated form with improved pharmacokinetic parameters. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;34:229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gesser B, Leffers H, Jinquan T, Vestergaard C, Kirstein N, Sindet-Pedersen S, Jensen SL, Thestrup-Pedersen K, Larsen CG. Identification of functional domains on human interleukin 10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14620–14625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zdanov A, Schalkhihi C, Wlodawer A. Crystal structure of human interleukin-10 at 1.6 angstrom resolution and a model of a complex with its soluble receptor. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1955–1962. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenwald RB, Yang K, Zhao H, Conover CD, Lee S, Filpula D. Controlled release of proteins from their poly(ethylene glycol) conjugates: Drug delivery systems employing 1,6-elimination. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:395–403. doi: 10.1021/bc025652m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scarisbrick IA, Towner MD, Isackson PJ. Nervous system-specific expression of a novel serine protease: Regulation in the adult rat spinal cord by excitotoxic injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8156–8168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08156.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitsui S, Okui A, Uemura H, Mizuno T, Yamada T, Yamamura Y, Yamaguchi N. In: Decreased cerebrospinal fluid levels of neurosin (KLK6), an aging-related protease, as a possible new risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Delatorre JC, Kalaria R, Nakajima K, Nagata K, editors. New York: Acad Sciences; 2002. pp. 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris MJ, Martin NE, Modi M. Pegylation: A novel process for modifying pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharm. 2001;40:539–551. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakane T, Pardridge WM. Carboxyl-directed pegylation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor markedly reduces systemic clearance with minimal loss of biologic activity. Pharm Res. 1997;14:1085–1091. doi: 10.1023/a:1012117815460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenblum LY, Johnson RC, Schmahai TJ. Preclinical safety evaluation of recombinant human interleukin-10. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35:56–71. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2001.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston IN, Milligan ED, Wieseler-Frank J, Frank MG, Zapata V, Campisi J, Langer S, Martin D, Green P, Fleshner M, Leinwand L, Maier SF, Watkins LR. A role for proinflammatory cytokines and fractalkine in analgesia, tolerance, and subsequent pain facilitation induced by chronic intrathecal morphine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7353–7365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laughlin TM, Bethea JR, Yezierski RP, Wilcox GL. Cytokine involvement in dynorphin-induced allodynia. Pain. 2000;84:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu CG, Fairbanks CA, Wilcox GL, Yezierski RP. Effects of agmatine, interleukin-10, and cyclosporin on spontaneous pain behavior after excitotoxic spinal cord injury in rats. J Pain. 2003;4:129–140. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chacur M, Milligan ED, Sloan EM, Wieseler-Frank J, Barrientos RM, Martin D, Poole S, Lomonte B, Gutierrez JM, Maier SF, Cury Y, Watkins LR. Snake venom phospholipase A2s (Asp49 and Lys49) induce mechanical allodynia upon peri-sciatic administration: Involvement of spinal cord glia, proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide. Pain. 2004;108:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abraham KE, Mcmillen D, Brewer KL. The effects of endogenous interleukin-10 on gray matter damage and the development of pain behaviors following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2004;124:945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daly SM, Przybycien TM, Tilton RD. Adsorption of poly(ethylene glycol)-modified ribonuclease A to a poly(lactide-coglycolide) surface. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;90:856–868. doi: 10.1002/bit.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]