Abstract

Implementation evaluations, also called process evaluations, involve studying the development of programmes, and identifying and understanding their strengths and weaknesses. Undertaking an implementation evaluation offers insights into evaluation objectives, but does not help the researcher develop a research strategy. During the implementation analysis of the UNAIDS drug access initiative in Chile, the strategic analysis model developed by Crozier and Friedberg was used. However, a major incompatibility was noted between the procedure put forward by Crozier and Friedberg and the specific characteristics of the programme being evaluated. In this article, an adapted strategic analysis model for programme evaluation is proposed.

Keywords: Crozier and Friedberg, implementation evaluation, process evaluation, strategic analysis

Introduction

There are numerous definitions of programme evaluation (Shortell and Richardson, 1978; Patton, 1982), but reviewing them is not the objective of the present article. Instead, we propose a new theoretical approach inspired by the strategic analysis model developed by Crozier and Friedberg (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992; Friedberg, 1993, 1994) to carry out implementation analysis. While by its very nature, implementation analysis refers to the implementation of a new programme, there are many variations and no single definition. In the evaluation research literature, it is often approached under the heading process analysis. This article takes its inspiration from the implementation analysis of the UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) access to anti-retroviral (ARV) drugs project in Chile carried out between September 1999 and September 2000.

In 1997, UNAIDS set up an experimental treatment access project for HIV/AIDS in developing countries as a first step for a wider strategy. UNAIDS decided to implement pilot-projects in four countries: Ivory Coast, Uganda, Vietnam and Chile. To be selected, countries had to:

demonstrate political and social stability;

demonstrate their political engagement in combating HIV;

have a national AIDS programme;

demonstrate good conditions for evaluation; and

have a high HIV infection prevalence or a high incidence of AIDS.

Availability of medical equipment and location in diverse geographical zones also constituted selection criteria (UNAIDS, 2000). The objective was to widen access to HIV/AIDS therapies, which implied negotiating drug prices corresponding to the economic reality of the country, and creating rational conditions for treatment access. The Drug Access Initiative was based on the assumption that drugs should be affordable, i.e. adapted to the country’s ability to pay (UNAIDS, 2000).

Our research was part of the evaluation programme of the UNAIDS Drug Access Initiative (DAI) in Chile, co-ordinated by the National Agency of Research on AIDS in France (ANRS) and mandated by UNAIDS. Since the launch of the DAI, UNAIDS wanted the pilot projects to be evaluated independently. In particular, the objective of this implementation-evaluation research was to examine how far the politico-organizational dynamic explained the development of the DAI, with the aim of identifying factors that helped or impeded its implementation. The goals of this research were to understand the dynamic of implementation of the project and to generate information for countries that are interested in participating in similar initiatives or willing to offer ARV treatment at large. The aim of this article is not to present our evaluation results (Brousselle, 2002; Brousselle and Champagne, 2004), but rather to discuss the use and utility of the conceptual framework we used to conduct the implementation analysis of the DAI in Chile.

The strategic systemic analysis model which was used poses successive research questions as it associates the research approach to the conceptualization of the model. However, during the project familiarization stage of our research, a major incompatibility was noted between the procedure put forward by Crozier and Friedberg ([1977] 1992), especially with regard to bringing to the fore a Concrete Action System (CAS) – a structural game between independent actors (see below) – and the specific characteristics of the programme being evaluated. Despite this observation, the strategic analysis model continued to suggest interesting conceptual elements for programme evaluation. In this article, an adapted strategic analysis model is proposed that allows the use of this approach even in cases where the programme does not constitute a CAS and only traces of the programme are observable. The interest the strategic analysis model holds for implementation analysis will be explained, showing how it meets the objectives of this type of evaluation, presenting its theoretical and methodological foundations, and the criticisms of its application. We then relate our experience, highlighting the incompatibilities observed between the proposed model and the programme being evaluated. Lastly, a strategic analysis approach for programme evaluation will be presented.

Strategic Analysis as a Model for Implementation Analysis

Implementation Analysis Defined

There is no consensus on the definition of implementation analysis beyond a very general definition that refers to the study of the implementation conditions of a programme. Implementation analysis is either defined solely through analysis of the processes, or it is the study of the production conditions of the effects.

Mary Ann Scheirer (1994) approaches it in relation to process evaluation. According to Scheirer, process evaluation aims to answer three main questions:

what is the programme intended to be? (methods to be developed and specified programme components);

what is delivered, in reality? (methods for measuring programme implementation); and

why are there gaps between programme plans and programme delivery? (assessing influences on the variability implementation). (Scheirer, 1994: 40)

Rossi et al. (1999) use Scheirer’s definition to define process evaluation and implementation analysis; they use the two terms interchangeably. They make a distinction between this type of evaluation and impact analysis: while process evaluation may be viewed as one step in the carrying out of an impact analysis, it can also be considered as an evaluation on its own. For Champagne et al. (1991: 95), the aim of implementation analysis is the study of the influence of organizational and contextual factors on the results obtained following the introduction of an innovation (Champagne et al., 1991: 95). Contrary to Scheirer’s definition, this one includes a consideration of the effects. For Champagne and Denis (1990), implementation analysis:

is conceptually based on three components, that is, the analysis of influences: of contextual factors on the degree of implementation of interventions; of variations in implementation on its efficiency (…); of the interaction between the implementation context and the intervention on the observed effects (…). (Champagne and Denis, 1990: 151)

It may be approached from various perspectives, using different models: the rational model, the organizational development model, and the psychological, political, and structural model (Denis and Champagne, 1990).

For Weiss (1998), three situations call for a process analysis:

One is when the key questions concern process. Evaluation sponsors want to know what is going on. Another is when key questions concern outcome, but we want to be sure what the outcomes were outcomes of (…). The third situation is when the evaluator wants to associate outcomes with specific elements of program process (…). (Weiss, 1998: 9)

For Weiss, the difference between process analysis and implementation analysis is that the latter does not deal with the processes that occur between programme services and meeting programme objectives: its focus is the implementation of services as defined by the programme.

For Rossi et al. (1999), implementation analysis is a component of programme monitoring. Weiss (1998: 181) admits there are similarities, but she maintains that the main difference is at the level of evaluation objectives, that is, whether it is carried out in such a way that it is accountable to high-level officials or programme sponsors (programme monitoring) or whether it is carried out in order to understand what is going on and to find ways to improve the programme (process evaluation).

According to Patton (1997), the aim of implementation analysis is essentially to know what is going on with the programme being implemented. Implementation analysis complements effects analysis in the sense that it firstly confirms that the programme has, in fact, been implemented. It also supplies information on the characteristics of the programme being implemented. According to Patton (1997), process analysis is one of the five dimensions of implementation analysis, along with effort evaluation, monitoring, components evaluation, and treatment specification.

Process evaluations search for explanations of the successes, failures, and changes in the program. Under field conditions in the real world, people and unforeseen circumstances shape programs and modify initial plans in ways that are rarely trivial. (…) Process evaluations not only look at formal activities and anticipated outcomes, but also investigate informal patterns and unanticipated consequences in the full context of program implementation and development. Finally, process evaluations usually include perceptions of people close to the program about how things are going. A variety of perspectives may be sought from people inside and outside the program. (…) There differing perspectives can provide unique insights into program processes as experienced and understood by different people. (Patton, 1997: 206)

The implementation analysis of the UNAIDS access to ARV programme was carried out in Chile. The aim of this programme was to make HIV/AIDS therapies accessible in developing countries (specifically Ivory Coast, Uganda, Vietnam and Chile). Our research was part of the evaluation process of the initiatives in the different countries. The programme’s implementation conditions were studied and the objectives were:

to explain how organizational dynamics influenced the implementation of the initiative; and

to identify the factors that facilitated or hindered the implementation process of the project; in order

to make recommendations.

This research corresponds with Patton’s definition of process evaluation. The strategic analysis model (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992) was used, as it is a very interesting conceptual framework for process analysis.

Theoretical Concepts of Strategic Analysis

The strategic analysis model developed by Crozier and Friedberg ([1977] 1992) is an organizational analysis model that centres on understanding the relationships between interdependent actors. This model is in keeping with the process analysis of the political networks movement (Kingdon, 1984; Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992; Friedberg, 1993; Klijn et al., 1995; Klijn, 1996; Gervais, 1998). This theoretical framework cannot be disassociated from the research approach. It does not assume a priori relationships between variables, but offers a conceptualization of collective action that integrates notions of contingency.

The conceptualization of collective action is done through the analysis of CASs. As previously noted, a CAS is a set of structured games between interdependent actors whose interests may be divergent, even contradictory. A system is defined as ‘an interdependent set’ (Crozier, 1987), the interdependence of the parties constituting the basic definition of a system (Ackoff, 1960). As soon as participants are dependent on each other, every collective action can be interpreted as an action system (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992). This definition is similar to that of political networks, which are characterized by the interdependence of multiple actors with multiple rationalities (Marsh and Rhodes, 1992; Kickert, 1993).

Every actor integrated in a collective action maintains privileged relationships with certain interlocutors called relays (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992). The process of making the network of interdependent actors apparent reveals the existence of a CAS. Within a CAS, the actors participate in games guided by certain more specific objectives. The CAS is composed of structured and regulated games (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992: 285). The definition of games is reminiscent of issue streams as used by Langley et al. (1995) in their study of decision-making processes. In the context of a CAS, the games are more or less integrated and linked to each other. All actors do not necessarily participate in the various games (Klijn et al., 1995); however, the game may modify the CAS, just as the CAS influences the games (Klijn et al., 1995). These therefore suppose an overall regulation: mechanisms that allow the CAS to exist. In the CAS, as in the games, the interaction processes are regulated by the rules of the game, by which the actors ‘regulate and manage their mutual dependencies’ (Friedberg, 1993). The rules may be defined on the basis of the formal structure of the organization or on the informal practices of the actors. The rules are an indication of the existence of power relations between various actors. They can either be constraints or zones of uncertainty that provide the actors room to manoeuvre (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992). The use that is made of the rules is part of the set of strategies that the various actors use to attain their goals. According to Crozier and Friedberg, every collective action structure is constituted as a power system. Power is:

the ability of an actor to structure more or less durable exchange processes in his favour by exploiting the constraints and opportunities of the situation in order to impose terms of exchange that are favourable to his interests. (Friedberg, 1993)

Power is the natural, not to say, normal, manifestation of human co-operation that always supposes a mutual and unbalanced dependence between the actors. (Friedberg, 1993)

According to Crozier and Friedberg ([1977] 1992), the study of power relations allows representation of relatively stable actor strategies. The actors’ strategies represent their position; their hand in the game. Actors’ strategies are not only a function of their interests, but also of their resources. Resources can take the form of knowledge, expertise, status, legitimacy, etc., depending on the perceptions of the various actors (Klijn et al., 1995).

Research Method

Since it favours an ‘inductive hypothesis’ approach (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992), this theoretical framework is intimately related to the research strategy.

Forced to recognize and assume the irreducible contingency of the phenomenon that it is trying to study, strategic analysis has no choice but to adopt an inductive hypothesis approach, used to constitute and define the object of its study through successive steps including observation, and comparison and interpretation of the multiple interaction and exchange processes that make up the backdrop of life within the action system under study. In short, it is an approach that uses the participants’ real-life experiences to propose and confirm more and more general hypotheses on the characteristics of the whole. (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992)

It is impossible to establish a clear boundary between the research approach and the theoretical model. According to the research approach favoured by Crozier and Friedberg ([1977] 1992), the first step consists in familiarizing oneself with the programme. This implies that one first makes sure that it conforms with the hypothesized existence of a CAS and then identifies the primary characteristics of that system. Second, various games need to be identified and studied in depth in order for one to understand their characteristics. Once the games have been analysed, the evaluator must ‘propose and confirm more and more general hypotheses about the characteristics of the whole’ (Crozier and Friedberg, [1977] 1992) in order to understand the regulation of the system in its entirety. The research questions are thus logically sequential and represent the steps in order to follow to understand the system.

Uses and Criticisms

Strategic analysis has been widely used in many different fields: the arts (Leloup, 1996); politics (Donneur and Padioleau, 1982); the prisons and criminal justice, and the police (Mouhanna, 1993; Proulx, 1993; Faivre, 1993); and the health sector (Bélanger, 1998; Gonnet, 1994; Funck-Brentano, 1994; Moisdon, 1994; de Pouvourville, 1994; Kuty and Vrancken, 1994; Binst, 1994). It is also used in the study of organizations in the public (Worms, 1994; de Closets, 1994; Trosa, 1994; Bienaymé, 1994; Chelimsky, 1994) and private sectors (Guiraud, 1994; Sainsaulieu, 1994; Berry, 1994; Morin, 1994; de Vulpian, 1994). This model may be used whenever there is a dynamic system ‘in action’.

Several criticisms have been levelled at the strategic analysis model. Jobert (1976) maintains that one cannot carry out the analysis of a CAS by analysing the components of this system and their relations independently of ‘their relations to groups and social classes as well as of the struggles’ (Jobert, 1976: 634); this model rejects these as a ‘negligible residue’ (Jobert, 1976: 634). Dion follows up on this criticism, stating that not everything is a system and that, while strategic analysis may explain the nature of exchanges within a system, it cannot explain ‘the reasons for the struggles or the aims of the actors’ (Dion, 1982: 99). It is also said that strategic analysis does not sufficiently take culture and ideology into account (Dion, 1994). Jobert (1976) also underlines the fact that in strategic systemic analysis, balance of power relations are less important than power relations. This is a criticism of the conceptualization of power, which has no independent existence in strategic analysis; it is relative (Friedberg, 1994), exercised by ‘some’ over ‘others’ (Foucault, 1982). According to Crozier, ‘The Power, with a capital P, of those who have it and those who do not, is a myth’ (Crozier, 1987: 788). This criticism can be related to Dion’s (1982) analysis, which underlines that unpredictability, considered by Crozier and Friedberg as a privileged area for the exercise of power and the acquisition of new influences, is not always a source of power, but that predictability can be. In fact, in order for predictability to be a source of power, the latter must be considered as an entity held by the actor and not as something that merely exists as an act (Foucault, 1982). While Bacharach and Lawler (1980) point out that the introduction of the notion of power in organizational theory in strategic analysis is interesting, they lament the fact that intra-organizational policy patterns are not more clearly identified.

The Use of Strategic Analysis for Implementation Analysis

There are a number of reasons that support the use of strategic analysis for implementation analysis – and in particular for process analysis (as defined by Patton). First, the aim of process evaluation is the study of the internal dynamics of a programme, which strategic analysis facilitates through in-depth study of strategic relationships. Second, the aim of process analysis is the study of formal and informal activities, which the conceptualization of strategic analysis facilitates through notions of systems, power relations and games between actors. Third, process analysis is based on the actors’ perceptions, as is strategic analysis, which takes into consideration their divergent interpretations.

Finally, both process evaluation and strategic analysis favour an inductive approach. Strategic analysis is particularly useful in the analysis of the third stage of Scheirer’s (1994) process analysis framework. This consists of explaining the observed differences between the planned programme and the one that was implemented. Scheirer argues that few evaluation reports examine the organizational structure and processes that influence the offer of services. This would be explained by the fact that evaluators wait for the results of impact studies to identify implementation problems, but it is then too late to collect valid data – real-time data – on the organizational processes affecting implementation (Scheirer, 1994: 61). The inductive approach favoured by strategic analysis renders the three research stages described by Scheirer inseparable. Although it necessarily implies research stages, research on programme components, their degree of implementation, and the explanation of the discrepancy with respect to the planned programme – these are carried out simultaneously. There is no time lag in terms of data collection that would make it impossible to explain the discrepancies observed. Strategic analysis allows the carrying out of a process implementation analysis that provides the evaluator with a guide for the conceptualization and realization of their research, without limitation to pre-existing research categories. The inductive process also raises the interest of stakeholders in participating in the evaluation project because it helps to increase the relevance and appropriateness of the evaluation design.

The use of a theoretical model for strategic analysis is a way of structuring the whole research process (e.g. themes under investigation, data collection, process of analysis), aiding the demystification of the evaluation and favouring a collaborative approach with stakeholders. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that it is based on three essential premises (Friedberg, 1994). First, since an actor is capable of strategy, they are rational. Second, this model uses a:

view of human relations as mediatized by power relations, that is, relations of unequal exchange that always include negotiation at their core. (Friedberg, 1994: 137)

Third, there is the use of the notion of a system.

The use of this notion is not related to any substantive hypothesis on the nature, the properties, or the limits of the systems we are trying to understand. It is simply the formulation of a research postulate, or, if one prefers, a heuristic hypothesis on the existence of a minimal order and interdependence behind the apparent disorder of the strategies of the individual and collective actors of a given field of action. It is up to the research process to show the existence of a minimal order through the empirical reconstruction of its limits or its boundaries, its regulation mechanisms and their effects. This system can thus only be characterized in fine, the research process allowing explanation of how the behaviours and the strategies of the actors both keep the system in action and constantly modify it. (Friedberg, 1994: 139)

The notion of a system is absolutely necessary to the use of the strategic analysis model for implementation analysis. As we have seen, several analogies lead one to suppose that strategic analysis is a very interesting conceptual tool for carrying out such an evaluation. However, to make its use possible, the researcher must necessarily formulate the hypothesis that the programme being studied is a CAS. In process analysis, showing that a programme is a system is not problematic – as long as the programme acts as a catalyst and the actors are interdependent, i.e. as long as the programme is in fact a system. But what happens to an evaluation project if it is not verified that the programme is a system?

Our Experience with Strategic Analysis

The Fall

Upon arrival in Chile, we contacted the local leaders of the organization responsible for the implementation of the project to discuss its progress, in order to familiarize ourselves with its development and the actors involved. In collaboration with the project leaders, we then identified the games that would be studied and the actors it would be interesting to meet with first. We decided to study two types of games. The first was the drugs importation process; this involved negotiations between the Department of Health division in charge of HIV/AIDS (CONASIDA) and pharmaceutical laboratories, through to the distribution of drugs to patients. The second type of game related to the four work groups that were set up to advise CONASIDA on the management of the project. Each group was to deal with one specific aspect of the project. The actors were interviewed in order to document the project and to discover the nature of their involvement in the implementation process. After having interviewed several actors and having consulted documents, we noted that the programme had not uncovered any real interdependence between the actors participating in its implementation; this was the case at both the drugs importation-process level and the working-group level. It was thus impossible to consider the programme as a CAS! Yet, theoretically, this was an essential condition of the research strategy. The evaluator then had to decide whether to end the evaluation process or continue, aiming to meet the evaluation objectives. The two games will be discussed in order to examine what occurred.

The Landing

Game 1: Importation/distribution of drugs

The aim of the UNAIDS programme was to allow the importation of drugs in developing countries at reduced prices. The UNAIDS representative met several times with local leaders in Chile, to set up an importation strategy in order to obtain the drugs at attractive prices. The situation in Chile is detailed below.

After evaluating drug needs based on epidemiological studies and the health-care protocol in place at the time, CONASIDA negotiated directly with the pharmaceutical laboratories’ subsidiaries in order to try to obtain commercial benefits (price reductions, bonuses on quantities bought). Once an agreement was reached, CONASIDA sent a purchase order to the central government office in charge of all commercial transactions between the government and private companies. The central office would call for bids and the laboratories would respond. The laboratories would then distribute the drugs directly to the health centres, and the hospitals sent the invoices to CONASIDA. Two taxes were levied on the purchase of drugs: a tax on imported goods, and a value-added tax corresponding to approximately 30 percent of the price of the drugs. During negotiations in the context of the project, the pharmaceutical companies agreed to provide new benefits on condition that the Chilean government agree to exempt the laboratories from the two taxes. The UNAIDS representative succeeded in negotiating a temporary mid-term agreement respecting this condition. The drugs would no longer be ordered through the central government office but rather through UNDP, which, as an international organization, is exempt from all import and value-added taxes. The government had ratified this agreement a few months prior to our arrival in the country. In order for the agreement to become totally legal it remained necessary for it to be approved by the ‘Contraloria’, an independent body that ensured the legitimacy of all governmental agreements. However, even after the ‘Contraloria’ had approved the agreement, it was not used for several months despite the benefits it offered in terms of therapeutic access for patients. There seemed to have been no further development in this dossier since the last visit of the UNAIDS representative.

Approval of the agreement by the ‘Contraloria’ may be one reason why the UNDP structure was not used by CONASIDA, but it was probably not the only one. The other divisions of the Health Department started using the agreement as soon as it had been ratified by the Chilean government and UNDP had declared that it was ready to start the importation of the drugs. Also, CONASIDA stated several times that it did not want to use the UNDP structure, not only as long as it had not been approved by the ‘Contraloria’, but also as long as UNAIDS financial support had not been received (CONASIDA had been waiting for several months for money UNAIDS had agreed to supply to finance certain activities related to the programme). Finally, it is important to note that following the supply of the funds from UNAIDS, CONASIDA still did not use the UNDP structure for drug purchase at the beginning of 2000.

Only the agreement with UNDP could be associated with UNAIDS’ ARV access programme. Yet at the time of our arrival and during the three months of our stay, the agreement was not used; nor was any development observed apart from the approval of the agreement by the ‘Contraloria’. Though whilst the agreement did legally exist, this was not evident in the field. Even if, theoretically, it implied the presence of co-ordinated activities between various actors that were not necessarily involved in the importation of drugs before its ratification, in practice, no change was observed. The programme had therefore not created any interdependence between the actors at the drug importation level, meaning that we could not consider it a sub-system of the CAS. This dossier was, nonetheless, a meaningful one as it shed light on CONASIDA’s political role at the national level and on the power it derived from the therapeutic distribution and access process (see Brousselle, 2002; Brousselle and Champagne, 2004).

Game 2: The Advisory Board

UNAIDS recommended the establishment of an Advisory Board to guide CONASIDA in the implementation of the ARV access project. Theoretically, this Board was to follow the progress of the project from its conception to its execution. CONASIDA set up four working groups (ethics, therapeutic protocol, treatment observance, resource mobilization), which included various representatives of organizations participating in the issue of access to care for individuals living with HIV/AIDS (e.g. representatives of healthcare personnel, NGOs, patient groups, etc.). These groups were expected to work independently to produce a reference document.

At the time of our arrival, the working groups, which existed in theory, were in fact dissolved; three of the four groups had not finished their work. We met with the working-group participants, none of whom said they continued their work excepting one participant who stated that he consulted with CONASIDA on an ad hoc basis. The Advisory Board was supposed to guide CONASIDA throughout the pilot project; instead, CONASIDA had taken control. The working groups served to boost the implementation of the project, but their involvement, such as had been defined in the pilot project plan, did not continue. Once again, it was impossible to establish any interdependence between the actors who participated in the working groups. It was therefore not possible to consider the working groups as sub-systems of the CAS.

The System and the Programme

Since, at the time of our study, no interdependence between the actors at the games level could be observed, the necessary conclusion following the logic of the theoretical framework would have to have been that none existed at the system level either. Such a conclusion, however, would have contradicted the actual situation in the field. Although the games observed could not be considered as sub-systems of the CAS, the project itself continued to exist. CONASIDA still considered giving access to tri-therapy and continued recognizing the existence of the UNAIDS programme, even though there was a re-appropriation of the project at the national level. The fact that the project no longer had a sufficient existence to allow its analysis in real time did not mean that the evaluation should be ended. Just as there are non-decisions on certain taboo subjects (Miller et al., 1996), there are non-games in certain organizational systems that a researcher would do well to study in order to better interpret the political phenomena. In dealing with non-decisions, Miller et al. (1996: 297) underline that ‘A knowledge of what these issues are is likely to be as revealing, or more so, as knowledge of what is overtly being discussed’. In such cases it is important to know why the project took such a turn, and why it is only its traces that could be observed. It is, above all, the result of a local dynamic and it is by studying this underlying context that the evaluator will be in a position to explain the level of implementation of the project and the orientation it took.

Data collection was reoriented in order to understand why the project had taken such a turn. First, observation of the games – or rather, the non-games –continued, but from a slightly different perspective. The aim ceased to be to study games in real time, which was in any case impossible given the evolution of the project, but became to try to go back in time in order to know what had really happened. The difficulty of such an approach is making sure the actors do not rationalize a posteriori their own past behaviour or situations (Bourdieu, 1993; Brousselle, 2002). The data collection strategy consisted rather of seeking objective information from the actors, with the hope that this would naturally lead participants to comment on the evolution of the project without forcing them into self-examination. Second, the HIV/AIDS context in the country was fully documented. All the actors that seemed to play a central role in access to HIV/AIDS therapies were met (several supply networks parallel to government sources existed), as well as all the actors that had been identified at the time of our interviews as having played a role in the HIV/AIDS issue in the country (e.g. NGOs, associations, etc.). Finally, every opportunity was seized to observe the relations between actors: during work meetings; during observations at health centres; during the annual Convention of people living with HIV/AIDS; in order to analyse the relations, be they co-operative or antagonistic.

The reorganization of data collection led to the identification of the networks of actors, increased understanding of alliances or antagonistic relationships, and increased understanding of the actors’ interests and the strategies used to reach their aims. The political dynamic of the HIV/AIDS theme at the global level was analysed. This study of the context underlying the project revealed the political games at the level of the HIV/AIDS theme. Thus it later became possible to draw conclusions regarding the evolution of the programme. In fact, understanding the games between the actors and the power relations present at the global level made it possible to infer the relations between actors at the narrower programme level. The actors were the same at the global and UNAIDS project level. The only difference was that all the actors participating in the theme did not necessarily play a role at the project dynamic level. Thus, the actors’ interests, their strategies – that is, the whole global political dynamic – were repeated at the local level. This research approach is the exact opposite of that favoured by Crozier and Friedberg ([1977] 1992). Instead of transferring the games dynamic to the CAS, we derived the political dynamic specific to the programme from the contextual dynamic. This led us to propose a new theoretical framework inspired by strategic analysis, and adapted to the context of implementation evaluation.

Proposal for a New Approach to Implementation Analysis

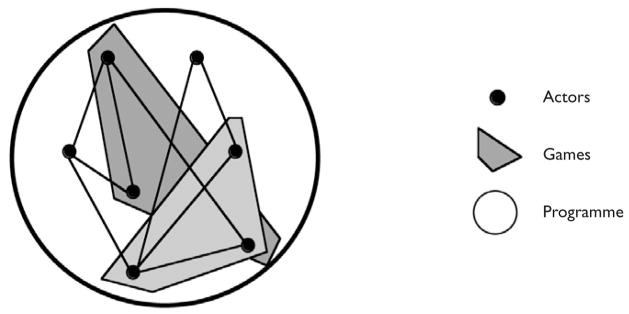

The use of the conceptual framework of network analysis implies considering the programme as a system of concrete action, i.e. as a network of interdependent actors. The first step thus consists in confirming or refuting this hypothesis. If the programme acts sufficiently as a catalyst to mobilize actors involved in its realization, the evaluator can use the now classic approach that consists of identifying the primary characteristics of the system, selecting various games that form an integral part of the programme, and studying them in order to understand the interests of the actors participating in these games, their strategies, alliances and conflicts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

From Internal Games to the Programme

Once the evaluator fully understands the interactions between actors at the local level of the games, she can extrapolate her conclusions to the programme level in order to establish what the politico-organizational dynamic is at the project level. The evaluator would then be in a position to explain the degree of project implementation and its orientation at the time the evaluation was carried out.

In cases where it is not possible to identify a network of interdependent actors involved in the realization of the programme and where there are in fact traces of programme implementation (it is presumed that the programme was in fact implemented before it was evaluated), following the above approach is not possible. The evaluator must then check the organizational context underlying the project. When a new programme is implemented, it generally becomes attached to an existing organizational setting. It is less common for a programme to be implemented with no previous organizational links. If this were the case, it would be surprising to only find traces of the programme during the implementation phase. In this relational network, some actors participated in the implementation of the programme, while others did not. In every case, the programme was subject to the alliances and conflicts characteristic of relations between actors at the organizational field level. Where a programme is not sufficiently present to allow implementation analysis through the identification of the sub-systems represented by the games, it is possible to carry out an implementation analysis through the analysis of the regulation patterns of the organizational context underlying the programme and through the retrospective analysis of the development of the project. The evaluation can be continued by approaching the project dynamic through the study of the games which are identified at the level of the underlying organizational framework, and which involve some of the actors who participated in the implementation of the project that is being evaluated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

From the Underlying Organizational Framework to the Programme

Such an approach implies carrying out significant parallel research on particularly important events in the development of the project in order to try to obtain the most complete picture of its evolution. This stage is present even in cases where the programme can be considered as a CAS. But if the programme is no longer directly observable, its study becomes more difficult, obliging even greater precision. If there is no organizational context, the evaluator has no other choice but to cease her evaluation. The different alternatives that the researcher is faced with are presented in Figure 3, by means of an algorithm.

Figure 3.

Strategic Analysis: A Conceptual Framework for Implementation Evaluation

Conclusion

Strategic analysis, as a sociological research model, has been widely applied in many fields of study including programme evaluation. The use of this theoretical model as a conceptual framework for the design of process analysis has various advantages for both stakeholders and evaluators. Relations between stakeholders and evaluators are often not easy. An evaluation project is time intensive and implies the mobilization of resources which can constrain the action of the organization being evaluated. Furthermore, as stakeholders do not have perfect control over the evaluation process, they are often reluctant to ‘open their doors’. Evaluations can also appear as threatening: what will the evaluator conclude? Who will have access to evaluation results? What consequences will we have to face? When stakeholders are reluctant, the evaluator has to face barriers to access during data collection, difficult relationships, and pressures during validation and publication of results. The solution is to find a compromise between the scientific and the political spheres from the beginning of the study, i.e. to realize a positive ‘contamination’ by ‘politicizing’ the scientific field while ‘scientifizing’ the political one (Brousselle, 2003). Strategic analysis is a good instrument to do this by establishing participatory relationships: the reasons for this are listed below. First, as it is a step-by-step investigation process, it is easy for stakeholders to understand and to follow, which is reassuring. Second, it is based on an inductive procedure with a pragmatic approach for determining the themes being studied. Stakeholders have to play a role in the evaluation design and contribute in order to increase relevance and sensibility to local research priorities. For the evaluators, the use of this model – which proposes a structured and tested inductive process of research – bridges the gap between the use of a theoretical framework and a locally adapted evaluation. It is also a solid argument against criticism stakeholders often make against methodology when they are disturbed by evaluation conclusions (Chelimsky, 1994). Furthermore, since the investigation procedure is based on a thorough understanding of the context under study, recommendations are contingent (Friedberg, 1994), which leads to an easier appropriation of analysis and initiation of change. The use of a model that creates cross-fertilization of both spheres allows evaluators to realize their study under positive conditions, which increases the credibility and the validity of evaluation research. Alternatively, the stakeholder has a better understanding of the process of research and will be more willing to participate; this maximizes the chance of the study being realized, which in turn responds to the accountability exercise of which the evaluation is often part.

It is right that the model being proposed is not directly a strategic analysis but rather a modified form adapted to reflect hazards of programme implementation. Yet, it retains all the characteristics we have just described, as only the levels of analysis are used differently. As the programme did not demonstrate sufficient synergy to be considered as a CAS and to be studied directly, the understanding of its development is through the strategic context of action of ‘the underlying organizational framework’. Models of implementation evaluation that propose pre-established categories are of little interest when programmes are not completely implemented or when they are significantly changed through appropriation by local organizations. Such models would therefore offer poor insights as to why the programme had such a peculiar evolution. This is where the adapted model we propose is a particularly interesting tool for implementation analysis. Whatever the level of implementation of the programme, the evaluator will have rich information and a deep understanding of its development and orientation.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank François Champagne and Gilles Bibeau of the University of Montreal, for their useful comments.

The Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC/CRM), the International Development Research Centre (IRDC/CRDI) and the ‘Groupe de Recherche Interdisciplinaire en Santé’ (GRIS, University of Montreal) contributed to the realization of this research. The author received a fellowship of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Biography

ASTRID BROUSSELLE is a post-doctoral researcher at the Douglas Hospital Research Centre. She has a PhD in public health and developed interests in program evaluation, health services organization, health economics and qualitative studies.

Footnotes

The title is inspired by the music from Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 film, La haine.

References

- Ackoff RL. Systems, Organizations, and Interdisciplinary Research. In: Emery FE, editor. Systems Thinking. New York: Penguin Books; 1960. pp. 330–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach S, Lawler EJ. The Social Psychology of Conflict Coalitions and Bargaining. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 980. Power and Politics in Organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger PR. Santé et services sociaux au Québec: un système en otage ou en crise? De l’analyse stratégique aux modes de régulation. Revue internationale d’action communautaire. 1988;20(60):145–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. L’analyse stratégique et les transformations de l’entreprise. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bienaymé A. Guider le changement. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Binst M. Vertus et limites de l’analyse stratégique pour l’intervention à l’hôpital. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 369–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. La misère du monde. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle A. Thèses et mémoires, ID 7653. Montréal: GRIS, Université de Montréal; 2002. Les enjeux de l’initiative d’ONUSIDA de mise à disposition de la trithérapie au Chili. [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle A. L’évaluation de qui, par qui, pour qui? L’influence des intérêts triangulaires sur la pratique de l’évaluation. Paper presented at the Congrès 2003 de la Société canadienne d’évaluation; Vancouver, Canada. 2–4 June..2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle A, Champagne F. How Was the UNAIDS Drug Access Initiative Implemented in Chile? Evaluation and Program Planning. 2004;27(3):295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Denis JL. Pour une évaluation sensible à l’environnement des interventions: l’analyse d’implantation. Service social: L’avenir des services ou services d’avenir. 1990;41(1):143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Denis JL, Pineault R, Contandriopoulos AP. Structural and Political Models of Analysis of the Introduction of an Innovation in Organizations: The Case of the Change in the Method of Payment of Physicians in Long-term Care Hospitals. Health Services Management Research. 1991;4(2):94–111. doi: 10.1177/095148489100400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelimsky E. Remarques sur l’évaluation de programmes. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier M. L’analyse stratégique en milieu hospitalier: pertinence et méthodologie. Gestions hospitalières. 1987;261(Décembre 86/Janvier 87):787–91. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier M, Friedberg E. L’acteur et le système. Les contraintes de l’action collective. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; [1977] 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Closets F. La réforme modeste. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- De Pouvourville G. Le sociologue, l’ingénieur et l’hôpital. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 357–61. [Google Scholar]

- De Vulpian A. De l’évolution paradigmatique des gens ordinaires à l’adaptation des entreprises. Comment guider le changement? In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Denis JL, Champagne F. L’analyse d’implantation: modèles et méthodes. La revue canadienne d’évaluation de programme. 1990;5(2):47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dion S. Pouvoirs et conflits dans l’organisation: grandeur et limites du modèle de Michel Crozier. Revue Canadienne de science politique [Canadian Journal of Political Science] 1982;15(1):85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dion S. Une stratégie pour l’analyse stratégique. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Donneur AP, Padioleau JG. Local Clientelism in Post-Industrial Society: The Example of the French Communist Party. European Journal of Political Research. 1982;10(4):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre J-L. Ce que fait la police: le travail des policiers en tenue dans un commissariat central parisien. In: Ackermann W, editor. Police, Justice, Prisons. Trois études de cas. Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Le sujet et le pouvoir. In: Foucault M, editor. 1994 Dits et Écrits 1954–1988. Montréal: Éditions Gallimard; 1982. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg E. Le Pouvoir et la Règle: Dynamiques de l’action Organisée. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg E. Le raisonnement stratégique comme méthode d’analyse et comme outil d’intervention. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Funck-Brentano J-L. L’analyse stratégique dans les activités de santé. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 345–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais M. Repenser le concept d’évaluation de l’efficacité d’une organisation. The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation. 1998;13(2):98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gonnet F. Application du raisonnement stratégique et systémique aux hôpitaux publics. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 337–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guiraud F. Applications de l’analyse stratégique aux problèmes de l’entreprise. de l’obéissance à la responsabilité diffusée. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jobert B. L’essentiel et le résidu (bis). Pour une critique de l’analyse systémique stratégique. Revue française de Sociologie. 1976;17:633–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kickert W. Complexity, Governance and Dynamics: Conceptual Explorations of Public Network Management. In: Kooiman J, editor. Modern Governance. New Government–Society Interactions. London: Sage; 1993. pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. New York: Harper-Collins; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn EH. Analysing and Managing Policy Processes in Complex Networks: A Theoretical Examination of the Concept Policy Network and its Problems. Administration and Society. 1996;28(1):90–119. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn EH, Koppenjan J, Termeer K. Managing Networks in the Public Sector: A Theoretical Study of Management Strategies in Policy Networks. Public Administration. 1995;73(3):438–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kuty O, Vrancken D. Stratégies et identités professionnelles. La nouvelle valeur d’autonomie en gériatrie. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 362–8. [Google Scholar]

- Langley A, Mintzberg H, Pitcher P, Posada E, Saint-Marcary J. Opening Up Decision Making: The View from the Black Stool. Organization Science. 1995;6(3):260–79. [Google Scholar]

- Leloup X. Statut professionnel et champ artistique. Recherches sociologiques. 1996;3:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D, Rhodes RAW. Policy Networks in British Politics: A Critique of Existing Approches. In: Marsh D, Rhodes RAW, editors. Policy Networks in British Government. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1992. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SJ, Hickson DJ, Wilson DC. Decision-Making in Organizations. In: Clegg SR, Hardy C, Nord WR, editors. Handbook of Organization Studies. London: Sage; 1996. pp. 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Moisdon J-C. Hôpital, instrumentation de gestion et analyse stratégique. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. pp. 350–6. [Google Scholar]

- Morin P. Le raisonnement de l’analyse stratégique: son application à l’intervention dans l’entreprise. In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhanna C. L’impossible décloisonnement: analyse de la réforme des services sociaux de l’Administration pénitentiaire. In: Ackermann W, editor. Police, Justice, Prisons. Trois études de cas. Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Practical Evaluation. London: Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Utilization-Focused Evaluation. The New Century Text. 3. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx M. Laisser-faire et gestion par la crise: sur le fonctionnement de quelques tribunaux d’instance parisiens. In: Ackermann W, editor. Police, Justice, Prisons. Trois études de cas. Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PH, Freeman HE, Lipsey MW. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. 6. London: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsaulieu R. Entreprise et société. Quelles sociologies? In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA. Designing and Using Process Evaluation. In: Wholey JS, Hatry HP, Newcomer KE, editors. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1994. pp. 40–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Richardson WC. Health Program Evaluation. St Louis, MO: CV Mosby; 1978. Program Evaluation: Historical Antecedents and Contemporary Developments; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Trosa S. Qui a vu passer la décentralisation? In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Program On HIV/AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2000. UNAIDS HIV Drug Access Initiative. Providing Wider Access to HIV-related Drugs in Developing Countries. Pilot Phase. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CH. Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Worms J-P. Mais si, on peut changer la société par décret! In: Pavé F, editor. L’analyse stratégique autour de Michel Crozier. Sa genèse, ses applications et ses problèmes actuels. Paris: Éditions du Seuil; 1994. [Google Scholar]