Abstract

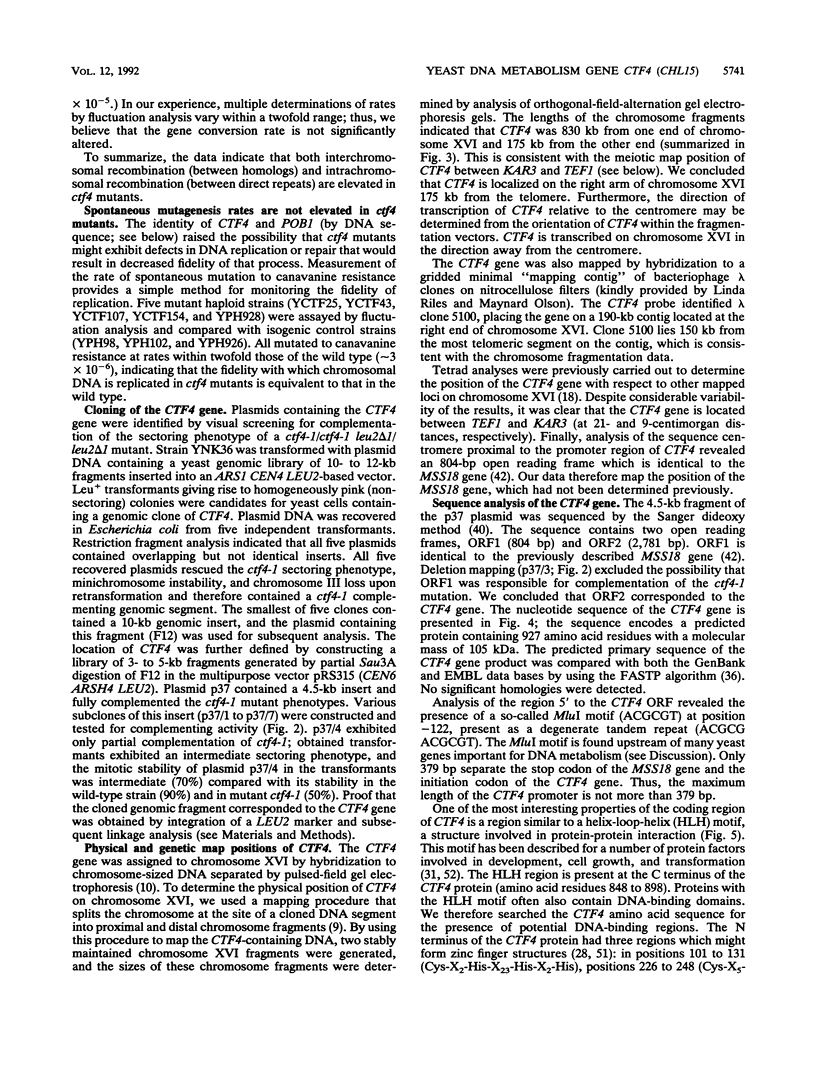

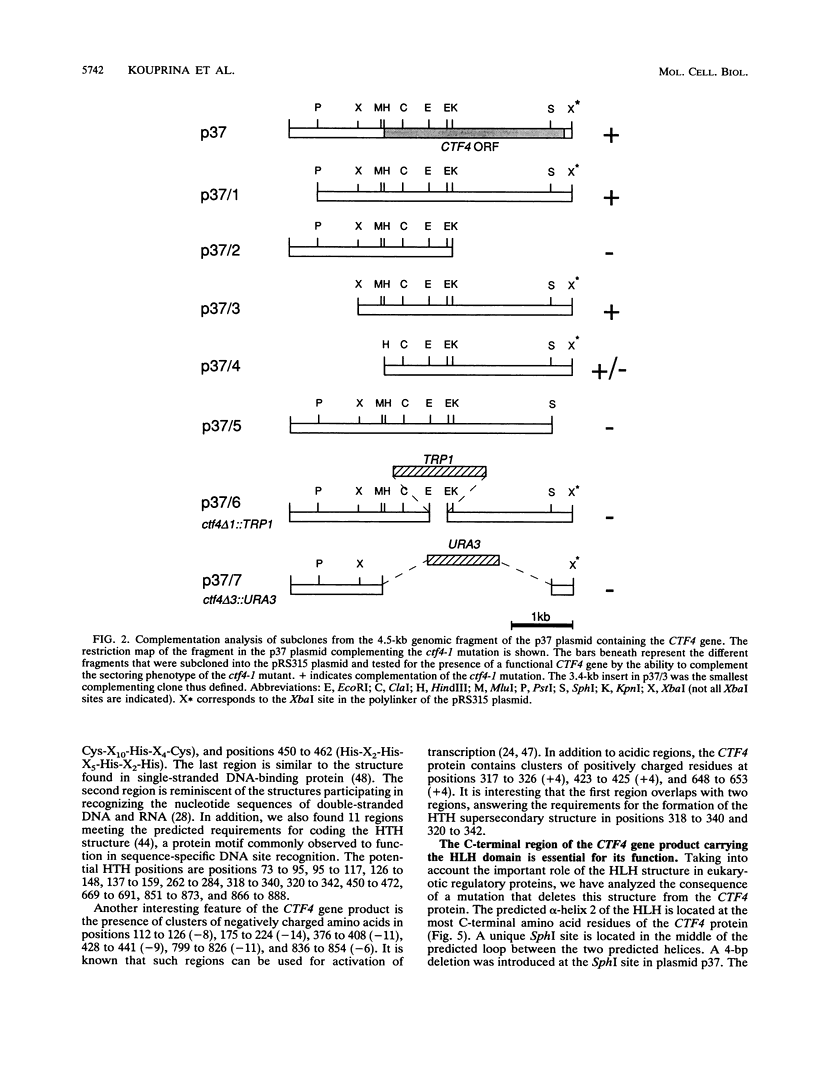

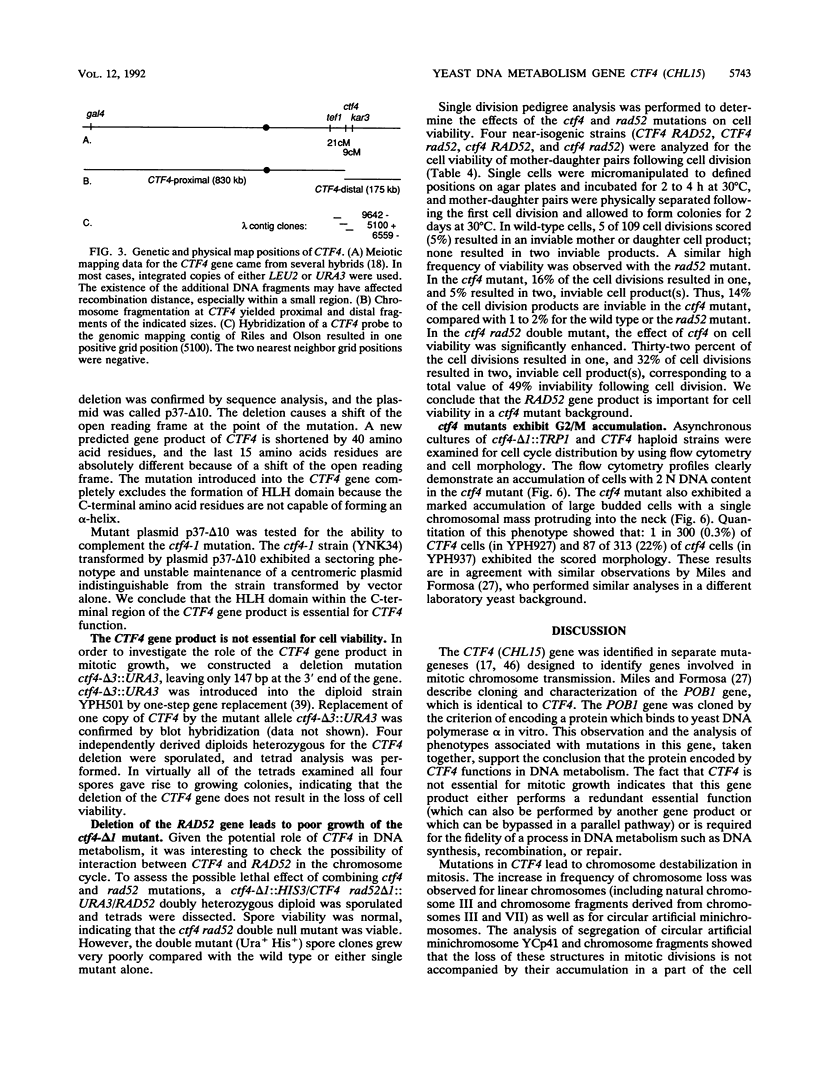

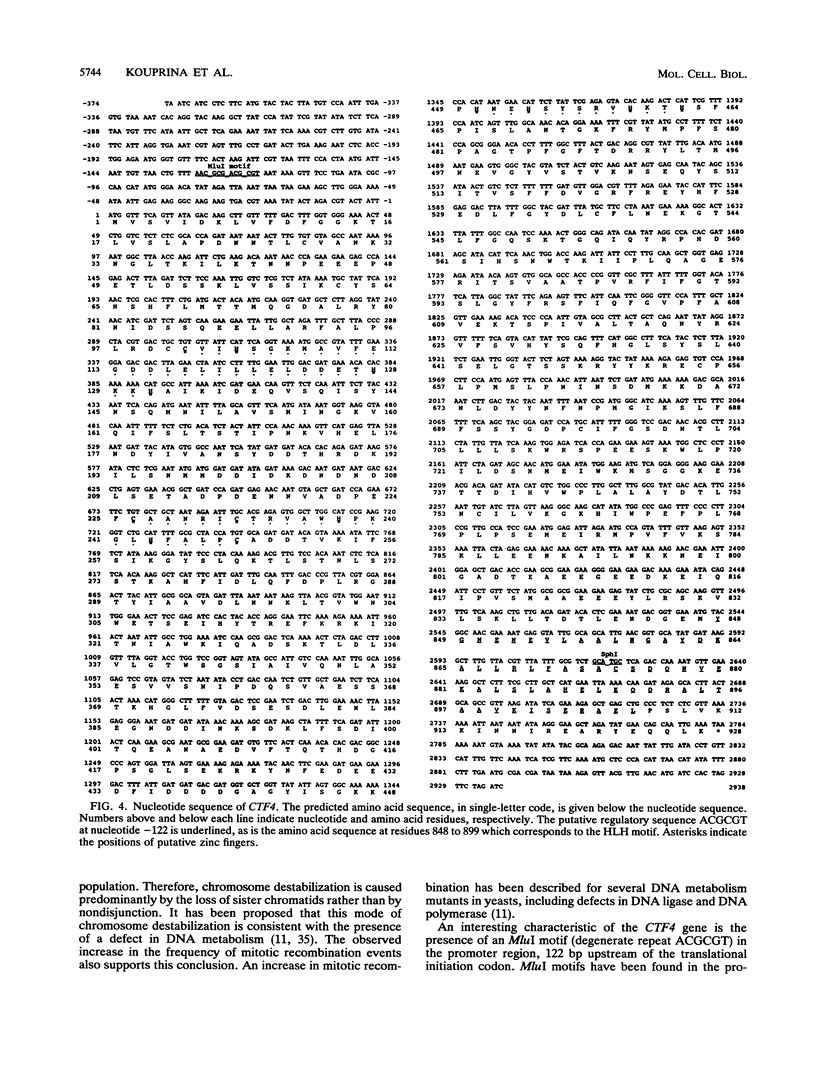

We have analyzed the CTF4 (CHL15) gene, earlier identified in two screens for yeast mutants with increased rates of mitotic loss of chromosome III and artificial circular and linear chromosomes. Analysis of the segregation properties of circular minichromosomes and chromosome fragments indicated that sister chromatid loss (1:0 segregation) is the predominant mode of chromosome destabilization in ctf4 mutants, though nondisjunction events (2:0 segregation) also occur at an increased rate. Both inter- and intrachromosomal mitotic recombination levels are elevated in ctf4 mutants, whereas spontaneous mutation to canavanine resistance was not elevated. A genomic clone of CTF4 was isolated and used to map its physical and genetic positions on chromosome XVI. Nucleotide sequence analysis of CTF4 revealed a 2.8-kb open reading frame with a 105-kDa predicted protein sequence. The CTF4 DNA sequence is identical to that of POB1, characterized as a gene encoding a protein that associates in vitro with DNA polymerase alpha. At the N-terminal region of the protein sequence, zinc finger motifs which define potential DNA-binding domains were found. The C-terminal region of the predicted protein displayed similarity to sequences of regulatory proteins known as the helix-loop-helix proteins. Data on the effects of a frameshift mutation suggest that the helix-loop-helix domain is essential for CTF4 function. Analysis of sequences upstream of the CTF4 open reading frame revealed the presence of a hexamer element, ACGCGT, a sequence associated with many DNA metabolism genes in budding yeasts. Disruption of the coding sequence of CTF4 did not result in inviability, indicating that the CTF4 gene is nonessential for mitotic cell division. However, ctf4 mutants exhibit an accumulation of large budded cells with the nucleus in the neck. ctf4 rad52 double mutants grew very slowly and produced extremely high levels (50%) of inviable cell division products compared with either single mutant alone, which is consistent with a role for CTF4 in DNA metabolism.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Benezra R., Davis R. L., Lockshon D., Turner D. L., Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990 Apr 6;61(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet A., Simon M., Faye G., Bauer G. A., Burgers P. M. Structure and function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC2 gene encoding the large subunit of DNA polymerase III. EMBO J. 1989 Jun;8(6):1849–1854. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Davis R. W. Yeast centromere binding protein CBF1, of the helix-loop-helix protein family, is required for chromosome stability and methionine prototrophy. Cell. 1990 May 4;61(3):437–446. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90525-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon J., Clarke L. Centromere structure and function in budding and fission yeasts. New Biol. 1990 Jan;2(1):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carle G. F., Olson M. V. Separation of chromosomal DNA molecules from yeast by orthogonal-field-alternation gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984 Jul 25;12(14):5647–5664. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.14.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Carbon J. Isolation of a yeast centromere and construction of functional small circular chromosomes. Nature. 1980 Oct 9;287(5782):504–509. doi: 10.1038/287504a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangman W. L., Brewer B. J. Activation of replication origins within yeast chromosomes. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:375–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983 Jul 1;132(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerring S. L., Connelly C., Hieter P. Positional mapping of genes by chromosome blotting and chromosome fragmentation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:57–77. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerring S. L., Spencer F., Hieter P. The CHL 1 (CTF 1) gene product of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is important for chromosome transmission and normal cell cycle progression in G2/M. EMBO J. 1990 Dec;9(13):4347–4358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Smith D. Altered fidelity of mitotic chromosome transmission in cell cycle mutants of S. cerevisiae. Genetics. 1985 Jul;110(3):381–395. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieter P., Mann C., Snyder M., Davis R. W. Mitotic stability of yeast chromosomes: a colony color assay that measures nondisjunction and chromosome loss. Cell. 1985 Feb;40(2):381–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt M. A., Stearns T., Botstein D. Chromosome instability mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that are defective in microtubule-mediated processes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Jan;10(1):223–234. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter K. J., Eipel H. E. Flow cytometric determinations of cellular substances in algae, bacteria, moulds and yeasts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1978;44(3-4):269–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00394305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. M., Snyder M., Chang L. M., Davis R. W., Campbell J. L. Isolation of the gene encoding yeast DNA polymerase I. Cell. 1985 Nov;43(1):369–377. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouprina NYu, Pashina O. B., Nikolaishwili N. T., Tsouladze A. M., Larionov V. L. Genetic control of chromosome stability in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1988 Dec;4(4):257–269. doi: 10.1002/yea.320040404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larionov V. L., Karpova T. S., Zhouravleva G. A., Pashina O. B., Nikolaishvili N. T., Kouprina N. Y. The stability of chromosomes in yeast. Curr Genet. 1987;11(6-7):435–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00384604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouy E., DePinho R., Zimmerman K., Collum R., Yancopoulos G., Mitsock L., Kriz R., Alt F. W. Structure and expression of the murine L-myc gene. EMBO J. 1987 Nov;6(11):3359–3366. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman D. J., Pearson W. R. Rapid and sensitive protein similarity searches. Science. 1985 Mar 22;227(4693):1435–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.2983426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liras P., McCusker J., Mascioli S., Haber J. E. Characterization of a mutation in yeast causing nonrandom chromosome loss during mitosis. Genetics. 1978 Apr;88(4 Pt 1):651–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes N. F., Johnson A. L., Johnston L. H. Coordination of expression of DNA synthesis genes in budding yeast by a cell-cycle regulated trans factor. Nature. 1991 Mar 21;350(6315):247–250. doi: 10.1038/350247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Ptashne M. Deletion analysis of GAL4 defines two transcriptional activating segments. Cell. 1987 Mar 13;48(5):847–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks-Wagner D., Hartwell L. H. Normal stoichiometry of histone dimer sets is necessary for high fidelity of mitotic chromosome transmission. Cell. 1986 Jan 17;44(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meluh P. B., Rose M. D. KAR3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell. 1990 Mar 23;60(6):1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90351-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles J., Formosa T. Evidence that POB1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein that binds to DNA polymerase alpha, acts in DNA metabolism in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Dec;12(12):5724–5735. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J., McLachlan A. D., Klug A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985 Jun;4(6):1609–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A., Araki H., Clark A. B., Hamatake R. K., Sugino A. A third essential DNA polymerase in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990 Sep 21;62(6):1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90391-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer R. K., Contopoulou R., Schild D. Mitotic chromosome loss in a radiation-sensitive strain of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Sep;78(9):5778–5782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C., McCaw P. S., Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989 Mar 10;56(5):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C., McCaw P. S., Vaessin H., Caudy M., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N., Cabrera C. V., Buskin J. N., Hauschka S. D., Lassar A. B. Interactions between heterologous helix-loop-helix proteins generate complexes that bind specifically to a common DNA sequence. Cell. 1989 Aug 11;58(3):537–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff N. F., Thomas J. H., Grisafi P., Botstein D. Isolation of the beta-tubulin gene from yeast and demonstration of its essential function in vivo. Cell. 1983 May;33(1):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlon C. S. Yeast chromosome replication and segregation. Microbiol Rev. 1988 Dec;52(4):568–601. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.4.568-601.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer R. E., Hogan E., Koshland D. Mitotic transmission of artificial chromosomes in cdc mutants of the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1990 Aug;125(4):763–774. doi: 10.1093/genetics/125.4.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirojkov V., Tsouladze A., Kouprina N., Larionov V. Determination of probability of plasmid loss per generation. Gene. 1984 May;28(2):237–239. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M. A., Martin P. The repair of double-strand breaks in the nuclear DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its genetic control. Mol Gen Genet. 1976 Jan 16;143(2):119–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00266917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. J. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz P. J., Solomon F., Botstein D. Genetically essential and nonessential alpha-tubulin genes specify functionally interchangeable proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;6(11):3722–3733. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shestopalov B. V. Amino acid sequence template useful for alpha-helix-turn-alpha-helix prediction. FEBS Lett. 1988 Jun 6;233(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989 May;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer F., Gerring S. L., Connelly C., Hieter P. Mitotic chromosome transmission fidelity mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1990 Feb;124(2):237–249. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. Promoters, activator proteins, and the mechanism of transcriptional initiation in yeast. Cell. 1987 May 8;49(3):295–297. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers M. F. Zinc finger motif for single-stranded nucleic acids? Investigations by nuclear magnetic resonance. J Cell Biochem. 1991 Jan;45(1):41–48. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P., Prakash L., Matson S. W., Prakash S. RAD3 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a DNA helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Dec;84(24):8951–8955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Séraphin B., Simon M., Faye G. MSS18, a yeast nuclear gene involved in the splicing of intron aI5 beta of the mitochondrial cox1 transcript. EMBO J. 1988 May;7(5):1455–1464. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumper G., Carbon J. Sequence of a yeast DNA fragment containing a chromosomal replicator and the TRP1 gene. Gene. 1980 Jul;10(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee B. L., Coleman J. E., Auld D. S. Zinc fingers, zinc clusters, and zinc twists in DNA-binding protein domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Feb 1;88(3):999–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronova A., Baltimore D. Mutations that disrupt DNA binding and dimer formation in the E47 helix-loop-helix protein map to distinct domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jun;87(12):4722–4726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. A., Hartwell L. H. The RAD9 gene controls the cell cycle response to DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1988 Jul 15;241(4863):317–322. doi: 10.1126/science.3291120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. H., Green S. R., Barker D. G., Dumas L. B., Johnston L. H. The CDC8 transcript is cell cycle regulated in yeast and is expressed coordinately with CDC9 and CDC21 at a point preceding histone transcription. Exp Cell Res. 1987 Jul;171(1):223–231. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakian V. A. Structure and function of telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 1989;23:579–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]