Abstract

Retrovirus is frequently used in the genetic modification of mammalian cells and the establishment of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) via cell reprogramming. Vector-induced genotoxicity could induce profound effect on the physiology and function of these stem cells and their differentiated progeny. We analyzed retrovirus-induced genotoxicity in somatic cells Jurkat and two iPSC lines. In Jurkat cells, retrovirus frequently activated host gene expression and gene activation was not dependent on the distance between the integration site and the transcription start site of the host gene. In contrast, retrovirus frequently down-regulated host gene expression in iPSCs, possibly due to the action of chromatin silencing that spreads from the provirus to the nearby host gene promoter. Our data raises the issue that some of the phenotypic variability observed among iPSC clones derived from the same parental cell line may be caused by retrovirus-induced gene expression changes rather than by the reprogramming process itself. It also underscores the importance of characterizing retrovirus integration and carrying out risk assessment of iPSCs before they can be applied in basic research and clinics.

Keywords: Retrovirus, Genotoxicity, Insertional mutagenesis, Gene expression, Somatic cells, Induced pluripotent cells

1. Introduction

Progress in reprogramming both mouse and human somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a major technical breakthrough (Okita et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2007; Wernig et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007). Not only it lends important insight into the molecular nature of cell reprogramming and pluripotency, it also represents a rational approach to generate patient-specific stem cell lines for modeling different diseases in vitro, for screening drugs and advancing the clinical application of cell-based therapy. The use of somatic cells to generate iPSCs also avoids the controversial approach of establishing embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines from human embryos. To derive iPSCs, a defined set of transcription factors is co-expressed in somatic cells to reprogram the differentiated cells. Retroviral vectors are frequently used for this purpose due to their high efficiency in gene delivery into somatic cells. However, since retrovirus integrates into the host genome semi-randomly, the risk of insertional mutagenesis that affects host cell physiology remains a concern (Baum et al., 2003; von Kalle et al., 2004). This risk will directly impact on the suitability of using iPSCs to model human diseases in vitro and the safety of applying iPSCs in disease treatment.

Insertional mutagenesis could arise from interruption of a reading frame if retrovirus integrates into the coding region, although the unaffected allele should continue to provide the wild-type gene product. However, haploinsufficiency, i.e., inactivation of a single allele, may be sufficient to contribute to a specific phenotype, such as tumorigenesis (Berger and Pandolfi, 2011). Since a significant portion of a gene is consisted of intron sequences and most retrovirus integrates into introns, the risk of interrupting a reading frame by retrovirus integration remains relatively low. The polyadenylation signal and any cryptic splice site in the viral genome could also generate premature transcription termination or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. However, little evidence supports the involvement of these mechanisms in influencing host gene expression. One other mechanism involves transcription activation of the host gene mediated by the enhancer in the long terminal repeat (LTR) of the provirus. Multiple studies in mice have shown the potential of host gene activation via this mechanism (Nienhuis et al., 2006; Uren et al., 2005). Adverse events including T-cell leukemia and myelodysplasia caused by vector-induced proto-oncogene activation have been reported in several human gene therapy clinical trials (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2008; Howe et al., 2008; Stein et al., 2010). However, such a risk is expected to be rare in cell reprogramming because the enhancer activity of retroviral LTR is generally down-regulated during the process, leading to gene expression silencing of the introduced reprogramming factors in established iPSCs (Okita et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2007). Initiation of the reprogramming event in somatic cells triggers the transcription activation of the endogenous counterparts of the four reprogramming factors and makes continued expression of the exogenous genes (Okita et al., 2007) dispensable. Silence of the retroviral promoter and enhancer activities in ESCs and pre-implantation embryos is well documented by various previous studies (Gautsch, 1980; Gorman et al., 1985; Jaenisch et al., 1981; Jahner and Jaenisch, 1985). However, fortuitous reactivation of the silent exogenous gene in iPSCs could still occur. This was demonstrated by the development of tumors in 20% of the murine F1 offspring derived from iPSCs due to reactivation of the retrovirally introduced c-myc gene (Okita et al., 2007). Whether random retroviral integration can alter host gene expression through other mechanisms in established iPSC lines remains unclear at present.

In this study, we examined retrovirus-induced insertional mutagenesis in Jurkat cells, a lineage-committed T lymphoid line, and two iPSC lines derived from the fibroblasts of a spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patient (Chang et al., 2011). We mapped the retrovirus integration sites in these cell lines and measured the expression of the host gene near the virus integration site. As predicted, we observed host gene activation induced by retrovirus integration in Jurkat cells. In contrast, we observed frequent down-regulation of host gene expression near the retrovirus integration site in iPSCs. Although the reason for the reduced gene expression in iPSCs remains unclear, our results demonstrate that the retrovirus-induced genotoxicity in somatic cells and stem cells is most likely mediated through different mechanisms. Our studies underscore the importance of characterizing retroviral integration and carrying out risk assessment of iPSCs before considering their application in basic study and clinics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid construction

Construction of pHIV7/C-GFP has been described previously (Yam et al., 2002). To construct pRV/C-GFP, a 2-kb CMV-GFP cassette was isolated from pHIV7/C-GFP with BamH1 and BglII digestion and cloned into the unique BamH1 site in pCLSA (Hall et al., 2007).

2.2. Cell culture, DNA transfection and vector production

Human 293T and HT1080 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/ml gentamicin and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37°C in 10% CO2. Jurkat cells were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml gentamicin and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2. Normal human ESC line H9 was obtained from National Stem Cell Bank (Madison, WI) and grown on irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) in ESC medium containing D-MEM/F12 supplemented with 20% knockout serum replacement, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM L-glutamine and 4 ng/ml bFGF. IPSC lines SMA-23 and SMA-25 were generated as described before (Chang et al., 2011) and cultured under the same condition as H9 except that the concentration of bFGF was increased to 16 ng/ml. For embryoid body (EB) formation, ESCs or iPSCs were harvested by collagenase IV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) treatment. Cell clumps were transferred to agar-coated Petri dish in ESC medium without bFGF for 7 days before harvest.

The retroviral vector was generated from 293T cells by calcium phosphate co-precipitation. Cells grown in a 100-mm culture dish were cotransfected with 10 μg of the vector, 10 μg of pCMV-GP and 2 μg of pCMV-G (Hall et al., 2007). Vectors were harvested 40 h later and tittered in HT1080 cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to detect GFP-positive cells. The two lentiviral constructs expressing the small hairpin RNA (shRNA) against PMCA2, LV/1304 and LV/3505, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo). The shRNA gene sequences in LV/1304 and LV/3505 are 5′CGAGATGGTAAAGAAGGTGATCTCGAGATCACCTTCTTTACCATCT CG3′ and 5′CCAGTGGATGTGGTGCATATTCTCGAGAATATGCACCACTTCCACT GG3′, respectively. The lentiviral vector was similarly generated and tittered as the retroviral vector except that the cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of the vector, 10 μg of pC-gp, 4 μg of pCMV-rev-2 and 2 μg of pCMV-G (Yam et al., 2002).

2.3. Transduction and isolation of Jurkat clones

Proliferating Jurkat cells were transduced with the vector at multiplicity of infection ranging from 0.2 to 2. Transduced cells were subjected to limiting dilution in 96-well plates 24 h later and GFP-positive wells were scored under a fluorescence microscope 1 wk later. GFP-positive clones were expanded and serially transferred into T-75 flasks.

2.4. Ligation-Mediated PCR (LM-PCR)

To map the vector integration site, the strategy described previously by Wu et al., 2003). The genomic DNA from individual Jurkat clones, H9 or iPSCs was isolated, and digested with MseI and either PstI or BglII. MseI cuts human genomic DNA frequently (the median fragment length is 70 bp) to reduce PCR bias against large fragments. Digestion with the second enzyme prevents the amplification of an internal vector fragment from the 5′LTR. The digested fragments were ligated to the MseI linker (linker: 5′GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCCGCTTAAGGGAC3′; linker: 5′-PO4-TAGTCCC TTAAGCGGAG-NH2-3′). LM-PCR was carried out using one primer specific to the LTR (5′GACTTGTGGTCTCGCTGTTCCTTGG3′) and the other specific to the linker (5′GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC3′). The PCR reaction was carried out in 25 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min. The PCR products were diluted 1:50 and nested PCR was performed under the same conditions. The primers for the nested PCR include LTR: 5′GGTCTCCTCTGAGTGATTGACTACC3′; linker: 5′AGGGCTCCGCTTAAGGGAC3′. Nested PCR products were cloned into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced. To map vector integration sites, the BLAT program was used to search the human genome (UCSC Human Genome Project Working Draft) as described (Schroder et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2003).

2.5. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total cellular RNA was isolated from transduced Jurkat cells, H9 and iPSCs using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). To generate cDNA, 1μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the high capacity RNA-to-cDNA master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed using comparative Ct method with power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), and the PCR thermal cycling conditions were set as 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s, 60°C for 60s. Two primer sets were used to amplify different regions of the same mRNA to corroborate the changes in the mRNA level. In the case that vector integration occurs within a gene, one of the two primer sets was designed to span across the vector integration site, to ensure that no additional mRNA species due to aberrant RNA splicing emerged. The constitutively expressed β-actin or Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was similarly amplified and used as the standard for normalizing the mRNA level. RT-PCR primer pairs with the following sequences were used to analyze SSH2 expression; Primer pair 1: 5′ACCTGTATCTGTGCAGGCAATGTG3′ & 5′AAGTGAGAAATAGGCTGCCTGGG3′; Primer pair 2: 5′CATCCACACCAAGAATCAGCCACA3′ & 5′TGATGTTGTCTTCTGGG CGGAGTA3′; The primer pairs with the following sequences were used to analyze PMCA2 expression; Primer pair 1: 5′TCAAGATCAAGGAGACTTATGGG3′ & 5′TTTGGCTTCTTTGGAGGTATAAA3′; Primer pair 2: 5′GGACCAGTGGATGTGGTGC ATATT3′ & 5′TGCCTCCTTGAGGAACTTGAGTCT3′.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with the R-statistical (version 2.9.2; http://www.r-project.org) or GraphPad Prism 45.0 software (GraphPad Software). Data was shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). For all statistical comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered significant (* P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01).

3. Results

3.1. Retrovirus integration activated host gene expression in Jurkat cells

To measure the vector-induced genotoxicity, we used a GFP gene-containing retroviral vector, RV/C-GFP, to transduce Jurkat T cells and GFP-positive clones were randomly picked. The retrovirus integration sites were amplified by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (LM-PCR) (Wu et al., 2003). As these Jurkat clones were derived from low multiplicity of infection (MOI), a single amplified DNA fragment containing the retroviral 3′LTR and the flanking host cellular DNA was detected in each clone and a total of 17 integration sites were unambiguously mapped. Out of these integration sites, 12 of them were mapped within genes and other 5 mapped at variable distances from a transcription unit (Table 1). Analysis of the cellular gene adjacent to the vector integration site based on the Retrovirus Tagged Cancer Gene Database (RTCGD) revealed that 7 sites had previously been mapped to retrovirus integration sites in the mouse genome (Table 1) (Akagi et al., 2004). Of interest, two independent integration sites from our study were mapped to the upstream region of the gene encoding zinc finger protein 217 (ZFP217) with a distance of 18 kb and 39 kb respectively from the transcription start site. The zfp217 gene was recognized previously as a common integration site (CIS) for retrovirus as it was repeatedly isolated via retrovirus-induced insertional mutagenesis in different studies (Sauvageau et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2002; Yanagida et al., 2005). Unlike those previous studies which relied on the generation of tumor in susceptible mouse strains, the clones in our study were isolated from a human cell line in the absence of any selection pressure. The fact that the zfp217 locus was repeatedly isolated with or without selection pressure suggested that this gene represented a true hot spot for retrovirus integration. Favored integration by retrovirus to this locus may be caused by the unique genomic architecture of the gene or by a specific interaction between a viral protein such as integrase and a sequence-specific DNA binding protein of the host.

Table 1.

Distribution of retrovirus integration sites in the Jurkat clones.

| Gene Name | Chra | Gene Description | genomic coordinates | Locationb | Directionc | Distanced | RISe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSH2 | 17 | slingshot 2 | 25,024,304 | 7 | same | 88 | 1 |

| FAT | 4 | FAT tumor suppressor 1 precursor | 187,749, 822 | 26 | inverse | 132 | 0 |

| C9org013 | 9 | gluconokinase-like protein | 85,429,765 | 1 | inverse | 2 | 0 |

| DKFZp547E087 | 16 | Hypothetical protein DKFZp547E087 | 22,369,480 | 1 | inverse | 14 | 0 |

| ZFP217 | 20 | zinc finger protein 217 | 51,671,544 | 5 prime | same | 39 | 6 |

| LOC284757 | 20 | hypothetical protein LOC284757 | 58,384,758 | 3 prime | inverse | 59 | 0 |

| C12orf32 | 12 | chromosome 12 open reading frame 32 | 2,857,594 | 1 | same | 1 | 0 |

| CACNA1C | 12 | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type | 2,672,109 | 50E | inverse | 639 | 0 |

| FNBP1 | 9 | formin binding protein 1 | 131,747, 972 | 6 | same | 58 | 5 |

| PTGES2 | 9 | prostaglandin E synthase 2 | 129,837, 977 | 3 prime | same | 59 | 0 |

| C21orf58 | 21 | hypothetical protein LOC54058 | 46,570,245 | 3 | inverse | 20 | 0 |

| ZFP217 | 20 | zinc finger protein 217 | 51,662,350 | 5 prime | inverse | 18 | 6 |

| ZFAT1 | 8 | zinc finger protein 406 isoform ZFAT-1 | 136,186, 630 | 5 prime | same | 37 | 0 |

| TGIF1 | 18 | TG-interacting factor | 3,439,454 | 2 | same | 37 | 1 |

| PMCA2 | 3 | plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2 | 10,454,517 | 2 | same | 270 | 1 |

| HTT | 4 | huntingtin | 3,173,187 | 41 | inverse | 127 | 0 |

| PITPNC1 | 17 | phosphatidylinositol transfer protein | 62,868,470 | 1 | inverse | 64 | 1 |

Human chromosome containing the provirus.

The position of the integration site relative to the nearest cellular gene. Each number indicates the intron containing the provirus. “E” denotes the exon. 5 prime: 5′ to the transcription start site; 3 prime: 3′ to the polyadenylation site.

The orientation of vector transcription relative to that of cellular gene transcription.

The distance (in kb) between the provirus and the transcription start site of the cellular gene.

The number indicates the frequency of the retrovirus integration site previously mapped in the mouse genome.

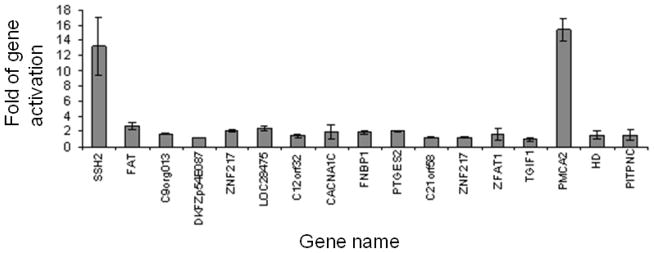

To determine the effect of vector integration on cellular gene expression, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to measure the gene expression level. Two sets of PCR primer that amplified different regions of the same mRNA were designed to corroborate the changes in the level of mRNA. Cellular gene expression was minimally affected in most clones (Fig. 1). However, two clones showed significant activation of the cellular gene harboring the provirus: expression of the slingshot 2 (ssh2) gene increased approximately 13 fold whereas expression of the plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2 (pmca2) gene increased approximately 15 fold (Fig. 1). We also carried out qRT-PCR to determine whether the cellular genes flanking the ssh2 and pmca2 genes were similarly affected. Our results showed that retrovirus integration only affected the gene containing the provirus but not other nearby genes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Activation of cellular gene expression by RV/C-GFP integration in Jurkat cells. The expression level of the cellular gene near each vector integration site was determined by qRT-PCR. Sample to sample variations were corrected by using the endogenous level of the β-actin transcript determined simultaneously. The expression level of each gene was then normalized to that in parental Jurkat cells which was arbitrarily set at 1. Results show means of duplicates + standard deviations (SD).

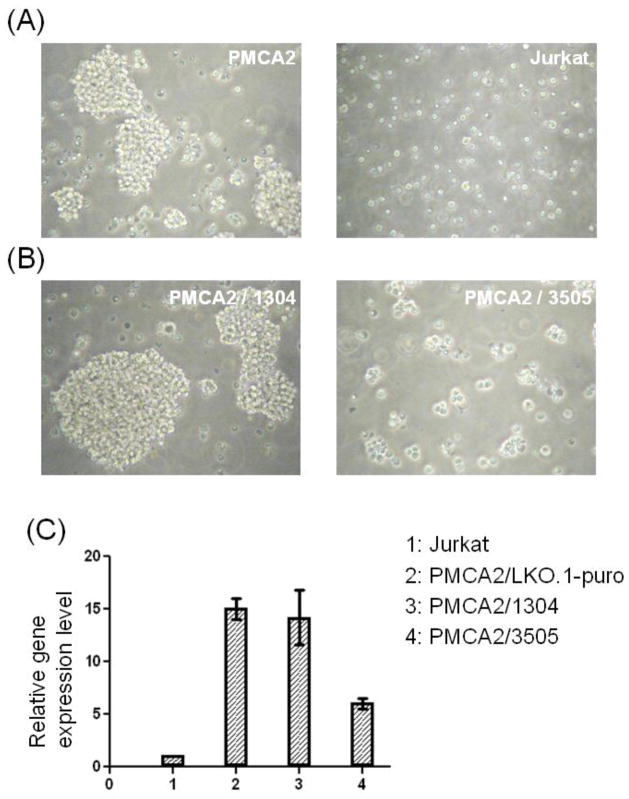

One unique phenotype of the clone with activated pmca2 expression was the tendency of proliferating cells to form large aggregates with few free-floating cells whereas parental Jurkat cells or cells from all other retrovirus-transduced Jurkat clones did not show such a phenotype (Fig. 2A). To determine whether this phenotype was caused by pmca2 activation, we down-regulated its expression with lentiviral vectors expressing pmca2-specific small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) 1304 and 3505, respectively. Cells expressing 1304 continued to exhibit the similar cell aggregation phenotype as the parental clone whereas cells expressing 3505 exhibited much smaller aggregates (Fig. 2B). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that the 1304 failed to reduce pmca2 expression whereas 3505 reduced pmca2 expression by approximately 60% (Fig. 2C). This result provides further support that in differentiated cells, retrovirus-induced insertional mutagenesis is frequently associated with gene activation, most likely caused by the enhancer sequence in the LTR. The gene activation event can lead to gross phenotypic changes to the host as demonstrated in the case of pmca2 activation.

Figure 2.

Altered morphology of Jurkat cells induced by PMCA2 activation. (A) The morphology of the Jurkat clone with activated PMCA2 expression and parental Jurkat cells. (B) Partial restoration of normal Jurkat cell morphology by PMCA2 shRNAs. The PMCA2-expressing clone was transduced with lenti-1304 and lenti-3505 carrying shRNA genes against PMCA2. Puromycin-resistance clones were pooled and the morphology of proliferating cells was shown. (C) A correlation between PMCA2 down-regulation and Jurkat cell morphology. Total RNA was isolated from parental Jurkat cells, PMCA2-expressing Jurkat cells transduced with a control lentiviral vector containing only the puromycin gene (LKO.1-puro), lenti-1304 and lenti-3505, respectively. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out, and the level of PMCA2 expression in each cell population was normalized against that in Jurkat cells which was arbitrarily set at 1.

3.2. Retrovirus integration down-regulated host gene expression in iPSC cells

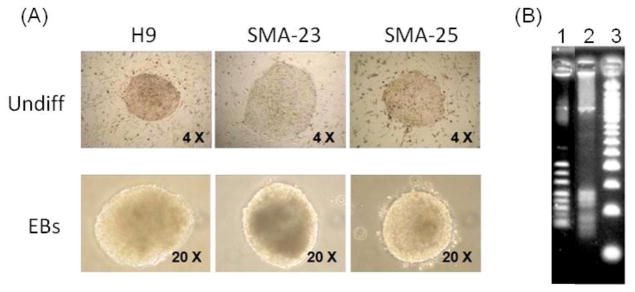

We previously used retroviral vectors expressing Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc to establish several human iPSC clones from GM09677, a SMA patient’s fibroblasts (Chang et al., 2011). Upon induction, these iPSC clones were readily differentiated into embryoid bodies (EBs) (Fig. 3A). Motoneurons derived from these iPSC clones were shown to exhibit some characteristics disease phenotypes (Chang et al., 2011). To measure the effect of retrovirus integration on host gene expression, we employed LM-PCR to map the retrovirus integration sites in two SMA iPSC clones, SMA-23 and SMA-25. As shown in Fig. 3B, LM-PCR showed approximately 8–9 prominent bands with variable sizes in SMA-23 and 5–6 bands in SMA-25. Upon cloning and DNA sequencing, 9 and 6 integration sites were unambiguously mapped in SMA-23 and SMA-25 cells, respectively. The number of mapped sites was consistent with the LM-PCR result and indicated that the vast majority of the integration site present in each clone had been identified. Of the 15 sites, 8 of them were mapped in introns and 1 was mapped in a 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (Table 2). The remaining 6 sites were mapped in the intergenic regions with variable distances from the nearby cellular gene. Whereas most of the integration sites showed the normal junction between the retroviral LTR and the flanking host genomic sequence, DNA rearrangement in the LTR-host DNA junction was detected surrounding the integration site in intron 6 of the anxa2 gene (Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Mapping of retroviral integration sites in SMA iPSC clones. (A) Morphology of undifferentiated H9 and SMA iPSC clones and differentiated embryoid bodies. (B) LM-PCR amplification of retroviral integration sites in the two SMA iPSC clones. Lane 1: SMA-23; 2: SMA-25; 3: size markers.

Table 2.

Distribution of retrovirus integration sites in the SMA iPSC clones.

| iPSC line | Gene Name | Chr | Gene Description | genomic coordinates | Location | Direction | Distance | RIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA-23 | FGF1 | 5 | fibroblast growth factor 1 (acidic) | 141998353 | 1 | inverse | 2.6 | 0 |

| LMO7 | 13 | LIM domain 7 | 76196309 | 1 | same | 1.7 | 0 | |

| C8orf34 | 8 | chromosome 8 open reading frame 34 | 69681667 | 10 | inverse | 331 | 0 | |

| ANKUB1 | 3 | ankyrin repeat and ubiquitin domain containing 1 | 149495731 | 3 | same | 15 | 0 | |

| TEK | 9 | TEK tyrosine kinase | 27090265 | 5 prime | inverse | 18 | 0 | |

| ANXA2 | 15 | annexin A2 | 60648772 | 6 | same | 41 | 0 | |

| SUFU | 10 | suppressor of fused homolog (Drosophila) | 104392662 | 3′ UTR | same | 129 | 0 | |

| PDC | 1 | phosducin | 186472009 | 5 prime | inverse | 42 | 0 | |

| ZNF598 | 16 | zinc finger protein 598 | 2060006 | 5 prime | inverse | 0.2 | 0 | |

| SMA-25 | FLJ44054 | 13 | uncharacterized LOC643365 (non-coding RNA) | 114598757 | 2 | inverse | 12 | 0 |

| GRAMD3 | 5 | GRAM domain containing 3 | 125783814 | 1 | same | 88 | 0 | |

| RTP3 | 3 | receptor (chemosensory) transporter protein 3 | 46529670 | 5 prime | same | 10 | 0 | |

| RAPGE F2 | 4 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 2 | 160217720 | 1 | same | 29 | 0 | |

| HAAO | 2 | 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase | 43144324 | 5 prime | inverse | 125 | 0 | |

| SP110 | 2 | SP110 nuclear body protein | 114598757 | 3 prime | same | 86 | 0 |

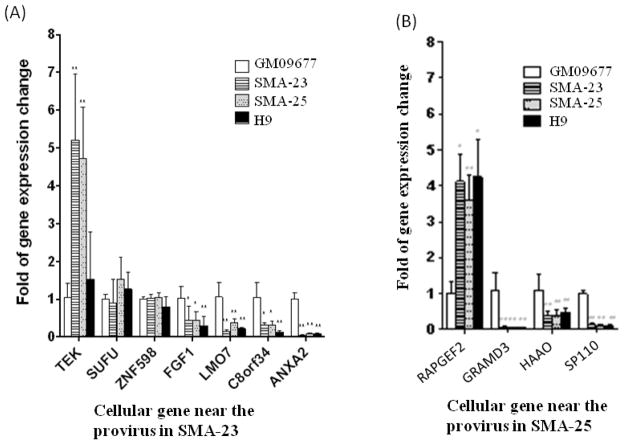

To determine the effect of retrovirus integration on cellular gene expression, total RNAs from GM09677 fibroblasts, SMA-23 and SMA-25 iPSCs were analyzed by qRT-PCR. As a control, the total RNA from normal human ESC line H9 was also subjected to the same analysis. Out of the 15 genes mapped, 11 genes including 7 genes from SMA-23 cells and 4 genes from SMA-25 cells exhibited detectable expression in GM09677 parental fibroblasts. This is consistent with the finding that retrovirus preferentially integrates into active genes (Bushman et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2003). The remaining 4 genes, including ankub1, pdc, flj44054 and rtp3, were expressed below detectable levels in the parental fibroblasts as well as in the two iPSC clones (data not shown). These genes were therefore excluded from our studies. Analysis of the 7 expressed genes in SMA-23 cells showed a significant increase in tek expression in SMA-23 cells relative to that in the parental fibroblasts (Fig. 4A). This increase was not caused by retrovirus integration since a similar increase was also observed in SMA-25 cells in which retrovirus integration was not detected near the tek locus (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the level of tek expression in the control H9 cells remained as low as that in the parental fibroblasts (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the cell reprogramming process might have triggered the activation of this gene. Relative to the expression of sufu and znf598 genes in GM09677 fibroblasts, no dramatic changes in the expression of these two genes were detected in H9, SMA-23 or SMA-25 (Fig. 4A). Expression of the remaining 4 genes near a retrovirus integration site in SMA-23 cells, including fgf1, lmo7, c8orf34, and anxa2, was reduced significantly when compared with that in GM09677 fibroblasts. Since expression of these 4 genes in both SMA-25 and H9 cells was down-regulated as well, retrovirus integration could not account for the reduced expression. It was shown before that suppression of lineage-specific genes in fibroblasts was a prerequisite for the transition of somatic cells from the differentiated state to a pluripotent state during cell reprogramming (Stadtfeld et al., 2008). Reduced expression of these genes in iPSCs may reflect such a transition.

Fig. 4.

Alteration in the expression of cellular genes near the provirus in parental fibroblasts and iPSC clones. The expression level of the cellular gene near each provirus was determined by qRT-PCR. Sample to sample variations were corrected by using the endogenous level of the GAPDH transcript determined simultaneously. The expression level of each gene harboring the provirus was then normalized to that in GM09677 fibroblasts which was arbitrarily set at 1. The figure indicates the expression of the cellular gene near each provirus in (A) SMA-23; (B) SMA-25. * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01.

We carried out a similar analysis to determine the effect of vector integration in SMA-25 cells. Expression of the rapgef2 gene was increased 4–5 fold in SMA-25 cells relative to that in parental fibroblasts (Fig. 4B). This increase was not caused by retrovirus integration since SMA-23 cells exhibited a similar increase in rapgef2 expression. Unlike the expression of the tek gene, rapgef2 expression in H9 cells was elevated to a similar level as that in the two SMA iPS cell lines (Fig. 4B), suggesting that cell reprogramming did not cause the increase. The remaining 3 genes with nearby vector integration, including gramd3, haao and sp110, all exhibited significantly reduced expression in both SMA iPSC clones and H9 cells relative to that in the parental fibroblasts (Fig. 4B). This is consistent with the notion that silencing linage-specific gene expression was important for cell reprogramming (Stadtfeld et al., 2008).

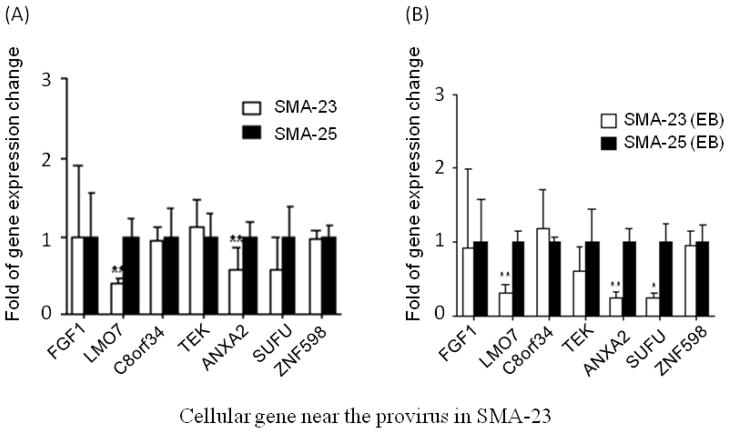

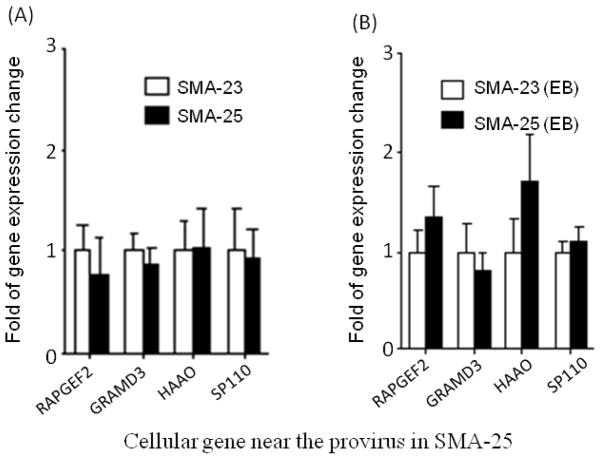

The above study suggests that the increased gene expression in iPSCs is most likely due to the intrinsic stem cell properties or the process of cell reprogramming. No evidence supports retrovirus-mediated gene activation in these two iPSC clones. However, when we directly compared the down-regulated genes in SMA-23 and SMA-25 clones, expression of 3 genes in SMA-23 cells, including lmo7, anxa2 and sufu, was reduced relative to that in SMA-25 cells (Fig. 5A). The reduced expression of the 3 genes in SMA-23 cells persisted after the cells were differentiated into EBs (Fig. 5B). Since these two cell lines were derived from the same parental fibroblasts, genetic variations could not be attributed to the observed difference in gene expression. The fact that the reduced gene expression occurred only in SMA-23 cells with retrovirus integrated near the 3 genes suggested that this reduction was likely caused by the retrovirus integration. Analysis of the 4 genes near the retrovirus integration sites in SMA-25 cells showed similar expression levels in SMA-23 and SMA-25 cells (Fig. 6A & B). We conclude from this data that the retroviruses used for cell reprogramming down-regulate the expression of some cellular genes near the integration site in iPSCs. The risk of reduced host gene expression could lead to unforeseeable outcome in iPSC proliferation and differentiation both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 5.

Suppression of cellular gene expression by retrovirus integration in undifferentiated SMA-23 and EBs. The relative gene expression level in undifferentiated SMA-23 iPSCs (A) and EBs (B) was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Fig. 4. The expression level of the provirus-containing gene in SMA-23 was normalized to that of the same gene in SMA-25 which was arbitrarily set at 1. * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01.

Figure 6.

No change in cellular gene expression in undifferentiated SMA-25 and EBs. The relative gene expression level in undifferentiated SMA-25 iPSCs (A) and EBs (B) was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Fig. 4. The expression level of the provirus-containing gene in SMA-25 was normalized to that of the same gene in SMA-23 which was arbitrarily set at 1.

4. Discussion

Our study shows frequent changes in cellular gene expression upon retrovirus integration both in a somatic cell line Jurkat and in pluripotent stem cells like SMA iPSCs. In Jurkat cells, 2 out of 17 retrovirus integration events led to the activation of host gene expression for more than 10 fold whereas in SMA iPSCs, 3 out of 11 integration events led to the suppression of host gene expression for up to 3 fold. Distinct mechanisms therefore mediate retrovirus-induced genotoxicity in different cell types. In somatic cells, activated host gene expression may lead to uncontrolled cell growth, or it can be inconsequential since most somatic cells have definite lifespan and limited capacity to proliferate. Retrovirus exhibits preferential integration near the transcription start site of an active gene (Wu et al., 2003). However, this bias may not account for the high gene activation efficiency since the distance between a provirus and the nearest host gene promoter is not correlated with the ability of the provirus to activate the host gene (Table1 and Fig. 1). The retrovirus integration sites of the two activated genes, ssh2 and pmca2, were mapped approximately 88 and 270 kb away from the respective promoter. Several other retrovirus integration sites were mapped much closer to the host gene promoter but failed to activate host gene expression (Fig. 1). Since many of the cellular genes near the retrovirus integration sites were active in Jurkat cells (data not shown), the transcription status of a gene could not account for the selective activation of ssh2 and pmca2. Long-range activation of c-myc expression by an integrated retrovirus has been reported previously(Lazo et al., 1990). It was proposed that chromosome looping that linked the endogenous promoter and the retrovirus enhancer in close proximity might be one mechanism that activated c-myc (Sotelo et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2010). The three-dimensional architecture of a gene may be important for the selective activation of its expression by a distant provirus although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Retrovirus integration activated pmca2 expression in Jurkat cells. PMCA, a major calcium pump that expels calcium from cells, is a P-type ATPase encoded by four genes (pmca1–4) in mammals (Strehler and Zacharias, 2001). PMCA4 is the dominant form in Jurkat cells whereas PMCA2 is expressed mainly in heart and brains (Caride et al., 2001; Stahl et al., 1992). Different PMCAs were activated by calcium at different rates: PMCA2 and PMCA3 being the fastest and PMCA4 the slowest (Caride et al., 2001). Increased expression of the more efficient PMCA2 pump in Jurkat cells by retrovirus integration should result in higher rates of calcium export which may account for the observed cell aggregation phenotype (Fig. 2A). Using shRNA to down-regulate PMCA2 expression in the Jurkat clone clearly demonstrated the link between the cell aggregation phenotype and the activated PMCA2 expression. Thus, besides cell immortalization and transformation, retrovirus integration can cause other overt physiological alterations in transduced cells.

Our analysis of iPSCs revealed frequently reduced gene expression of those cellular genes adjacent to provirus. Out of 11 cellular genes in SMA-23 cells, 3 genes were down-regulated in both undifferentiated iPSCs and differentiated EBs. Although retrovirus-induced DNA rearrangement in the anxa2 gene may explain the reduced expression of this gene, no genomic abnormality adjacent to the retrovirus integration site could be detected in the lmo7 and sufu genes. Since the enhancer activity of the retrovirus LTR is known to be silent in iPSCs (Takahashi et al., 2007), one possibility is that the action of chromatin silencing spreads from the retrovirus LTR to the nearby host gene promoter, leading to the suppression of its activity (Talbert and Henikoff, 2006). Since a retroviral integration occurred in the 3′UTR of the sufu gene, we could not exclude the possibility that this integration affects the stability of the sufu mRNA. Interestingly, the selective suppression of the nearby host gene is not correlated with the physical distance between the provirus and the host gene promoter, analogous to the long-distance promoter activation by a provirus in somatic cells. This result is somewhat different from the work reported by Winkler et al. (Winkler et al., 2010). They analyzed the effect of the lentiviral vector on host gene expression in iPSCs and showed that both gene activation and gene suppression could occur after lentivirus integration. Unlike the retroviral LTR, the EF1α internal promoter Winkler et al. used for the expression of the reprogramming factors was shown to be active in stem cells (Hong et al., 2007; Xia et al., 2007). Variations in the EF1α promoter activity in Winkler et al.’ study may account for the differential effect on the expression of the host gene near the integration site.

At present, retrovirus remains one of the most popular choices to establish iPSCs due to its high efficiency for gene delivery and silencing of the exogenous genes in reprogrammed stem cells. However, iPSCs derived from retroviral transduction generally harbored multiple vector copies, resulting in efficient transgene expression considered critical to reprogram the differentiated cells (Okita et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2007). The risk of insertional mutagenesis induced by multiple retrovirus integration can complicate data analysis and preclude the clinical application of iPSCs. Our current data reinforces these concerns. It remains unclear whether a reduction in the expression of the lmo7, anxa2 and sufu genes affects the proliferation and differentiation of the iPSCs. Down-regulation of lmo7 expression affected heart development in zebrafish and caused dystrophic muscle in mice (Holaska et al., 2006; Ott et al., 2008). The reduced expression of lmo7 in SMA-23 could therefore compromise the capacity of this iPSC clone to differentiate into cardiomyocyte or cells of muscle lineages, a hypothesis that can be tested. Our data also raises the issue that some of the phenotypic variability observed among iPSC clones derived from the same parental cell line may be caused by retrovirus-induced gene expression changes rather than by the reprogramming process itself. Our results support the use of episomal vectors as the preferred strategy to derive iPSCs to avoid the problems caused by retrovirus-induced insertional mutagenesis (Okita et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2009). It also underscores the importance of characterizing retrovirus integration and carrying out risk assessment of iPSCs before they can be applied clinically.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates high frequencies of insertional mutagenesis induced by retrovirus integration into somatic cells and iPSCs. However, the induced genotoxicities are different: in somatic cells, host gene activation is frequently observed whereas in iPSC, host gene suppression is observed. Our studies underscore the importance of characterizing retroviral integration and carrying out risk assessment of iPSCs before considering their application in basic study and clinics.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Retrovirus integration activates host gene expression in somatic cells

Most host gene expression changes in cell reprogramming is not caused by retrovirus

Retrovirus integration often suppresses host gene expression in iPSCs

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIAID program Project AI061839. We wish to thank Gary Felsenfeld (NIH) for providing pJC13-1 and Cheryl Xia for her help to isolate some of the Jurkat clones. We also wish to thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at the City of Hope for expert assistance in this work.

The Abbreviation List

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- SMA

spinal muscular atrophy

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- EB

embryoid bodies

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- LM-PCR

ligation-mediated PCR

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- RTCGD

retrovirus tagged cancer gene database

- CIS

common integration site

- ssh2

slingshot 2

- pmca2

plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akagi K, Suzuki T, Stephens RM, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. RTCGD: retroviral tagged cancer gene database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D523–527. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum C, Dullmann J, Li Z, Fehse B, Meyer J, Williams DA, von Kalle C. Side effects of retroviral gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003;101:2099–2114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AH, Pandolfi PP. Haplo-insufficiency: a driving force in cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223:137–146. doi: 10.1002/path.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman F, Lewinski M, Ciuffi A, Barr S, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, Hoffmann C. Genome-wide analysis of retroviral DNA integration. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caride AJ, Filoteo AG, Penheiter AR, Paszty K, Enyedi A, Penniston JT. Delayed activation of the plasma membrane calcium pump by a sudden increase in Ca2+: fast pumps reside in fast cells. Cell Calcium. 2001;30:49–57. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T, Zheng W, Tsark W, Bates S, Huang H, Lin RJ, Yee JK. Brief report: phenotypic rescue of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived motoneurons of a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Stem Cells. 2011;29:2090–2093. doi: 10.1002/stem.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautsch JW. Embryonal carcinoma stem cells lack a function required for virus replication. Nature. 1980;285:110–112. doi: 10.1038/285110a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman CM, Rigby PW, Lane DP. Negative regulation of viral enhancers in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. Cell. 1985;42:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, Soulier J, Lim A, Morillon E, Clappier E, Caccavelli L, Delabesse E, Beldjord K, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SL, Lau KH, Chen ST, Felt JC, Gridley DS, Yee JK, Baylink DJ. An improved mouse Sca-1+ cell-based bone marrow transplantation model for use in gene- and cell-based therapeutic studies. Acta Haematol. 2007;117:24–33. doi: 10.1159/000096785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaska JM, Rais-Bahrami S, Wilson KL. Lmo7 is an emerin-binding protein that regulates the transcription of emerin and many other muscle-relevant genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3459–3472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Hwang DY, Yoon S, Isacson O, Ramezani A, Hawley RG, Kim KS. Functional analysis of various promoters in lentiviral vectors at different stages of in vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1630–1639. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe SJ, Mansour MR, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, Hubank M, Kempski H, Brugman MH, Pike-Overzet K, Chatters SJ, de Ridder D, et al. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3143–3150. doi: 10.1172/JCI35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R, Jahner D, Nobis P, Simon I, Lohler J, Harbers K, Grotkopp D. Chromosomal position and activation of retroviral genomes inserted into the germ line of mice. Cell. 1981;24:519–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahner D, Jaenisch R. Retrovirus-induced de novo methylation of flanking host sequences correlates with gene inactivity. Nature. 1985;315:594–597. doi: 10.1038/315594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo PA, Lee JS, Tsichlis PN. Long-distance activation of the Myc protooncogene by provirus insertion in Mlvi-1 or Mlvi-4 in rat T-cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:170–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienhuis AW, Dunbar CE, Sorrentino BP. Genotoxicity of retroviral integration in hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2006;13:1031–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, Okada A, Morizane A, Okamoto S, Hong H, Nakagawa M, Tanabe K, Tezuka K, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott EB, van den Akker NM, Sakalis PA, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Te Velthuis AJ, Bagowski CP. The lim domain only protein 7 is important in zebrafish heart development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3940–3952. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvageau M, Miller M, Lemieux S, Lessard J, Hebert J, Sauvageau G. Quantitative expression profiling guided by common retroviral insertion sites reveals novel and cell type specific cancer genes in leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:790–799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo J, Esposito D, Duhagon MA, Banfield K, Mehalko J, Liao H, Stephens RM, Harris TJ, Munroe DJ, Wu X. Long-range enhancers on 8q24 regulate c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3001–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906067107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, Hochedlinger K. Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl WL, Eakin TJ, Owens JW, Jr, Breininger JF, Filuk PE, Anderson WR. Plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase isoforms: distribution of mRNAs in rat brain by in situ hybridization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;16:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein S, Ott MG, Schultze-Strasser S, Jauch A, Burwinkel B, Kinner A, Schmidt M, Kramer A, Schwable J, Glimm H, et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler EE, Zacharias DA. Role of alternative splicing in generating isoform diversity among plasma membrane calcium pumps. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:21–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Minehata K, Akagi K, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Tumor suppressor gene identification using retroviral insertional mutagenesis in Blm-deficient mice. EMBO J. 2006;25:3422–3431. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Shen H, Akagi K, Morse HC, Malley JD, Naiman DQ, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. New genes involved in cancer identified by retroviral tagging. Nat Genet. 2002;32:166–174. doi: 10.1038/ng949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Spreading of silent chromatin: inaction at a distance. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:793–803. doi: 10.1038/nrg1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren AG, Kool J, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis: past, present and future. Oncogene. 2005;24:7656–7672. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kalle C, Fehse B, Layh-Schmitt G, Schmidt M, Kelly P, Baum C. Stem cell clonality and genotoxicity in hematopoietic cells: gene activation side effects should be avoidable. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:303–318. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler T, Cantilena A, Metais JY, Xu X, Nguyen AD, Borate B, Antosiewicz-Bourget JE, Wolfsberg TG, Thomson JA, Dunbar CE. No evidence for clonal selection due to lentiviral integration sites in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:687–694. doi: 10.1002/stem.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JB, Brown SJ, Cole MD. Upregulation of c-MYC in cis through a large chromatin loop linked to a cancer risk-associated single-nucleotide polymorphism in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01384-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, Burgess SM. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X, Zhang Y, Zieth CR, Zhang SC. Transgenes delivered by lentiviral vector are suppressed in human embryonic stem cells in a promoter-dependent manner. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:167–176. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam PY, Li S, Wu J, Hu J, Zaia JA, Yee JK. Design of HIV vectors for efficient gene delivery into human hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2002;5:479–484. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida M, Osato M, Yamashita N, Liqun H, Jacob B, Wu F, Cao X, Nakamura T, Yokomizo T, Takahashi S, et al. Increased dosage of Runx1/AML1 acts as a positive modulator of myeloid leukemogenesis in BXH2 mice. Oncogene. 2005;24:4477–4485. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.