Abstract

Objective

To determine how central field loss (CFL) affects reaction time to pedestrians and test the hypothesis that scotomas lateral to the preferred retinal locus will delay detection of hazards approaching from that side.

Methods

Eleven participants with binocular CFL (scotoma diameter 7°-25°; VA 0.3-1.0 logMAR) using lateral preferred retinal fixation loci and eleven matched controls with normal vision drove in a simulator for about an hour and a half per session, for two sessions a week apart. Participants responded to frequent virtual pedestrians that appeared on either the left or right sides, and approached the participants’ lane on a collision trajectory that, therefore, caused them to remain in approximately the same area of the visual field.

Results

CFL participants reacted more slowly to pedestrians that appeared in the area of visual field loss than in non-scotomatous areas (4.3 vs. 2.4 seconds, p<0.001), and had more late and missed responses than controls (29% vs. 3%, p< 0.001). Scotoma size and contrast sensitivity predicted outcomes in blind and seeing areas, respectively. Visual acuity was not correlated with response measures.

Conclusions

In addition to causing visual acuity and contrast sensitivity loss, the central scotoma per se delayed hazard detection even though small eye movements could potentially compensate for the loss. Responses in non-scotomatous areas were also delayed, though to a lesser extent, possibly due to the eccentricity of fixation. Our findings will help practitioners in advising patients with CFL about specific difficulties they may face when driving.

INTRODUCTION

Central visual field loss (CFL) is a scotoma encompassing the fovea, commonly caused by age-related macular degeneration (AMD); but, there are many other causes.(1, 2) People with CFL almost always use a preferred retinal locus (PRL) (3, 4), an extra-foveal location near the scotoma, to fixate targets that would normally be foveally fixated (we will refer to scotoma location/direction relative to the PRL in visual field space, not in retinal directions). The scotoma is lateral to the PRL in ~65% of cases, but can be above or, rarely, below.(4, 5) CFL also reduces visual acuity (VA) and contrast sensitivity as these are normally poorer in peripheral retina. In some countries (e.g., the UK(6) and Canada(7)) driving regulations address central visual field integrity and peripheral field extent. In the USA, however, driving regulations do not explicitly address CFL and it is thus considered only as acuity loss.(8) We hypothesize that vision loss due to CFL may have a greater impact on driving than just acuity loss.

People with AMD report difficulty driving. (9-13) However, many continue driving even when their VA falls below the legal limit, and even when they have CFL.(13, 14) Delayed responses to stop signs and traffic lights have been reported for people with CFL in driving simulator studies (12, 15). In an on-road study, 25% of current drivers with AMD passed a driving test compared to 42% of people with peripheral field loss and 64% with other mild visual field impairments.(16)

Although CFL is associated with driving difficulty, it is not known how the scotoma and its location affect driving skills. In a recent driving simulator study, people with hemianopia frequently failed to detect pedestrians appearing in their blind side of the road.(17) We therefore hypothesized that scotomas lateral to the PRL would cause difficulty in detecting pedestrians appearing on that side despite the smaller size of the scotomas.

Visual acuity is widely used in driving regulations but it is a poor predictor of performance.(18) Contrast sensitivity is more predictive of driving outcomes in older adults with normal vision (NV) (18) and is correlated with driving skills in people with moderate peripheral field loss.(19) We therefore examined the relationship between pedestrian detection performance and a range of clinical vision measures, including scotoma size and location. We hypothesized that better contrast sensitivity, and smaller scotoma size, but not better VA, would permit faster detection.

METHODS

The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by institutional review boards at Schepens and the Veterans Administration Boston Healthcare System.

Participants

Participants had at least 120° horizontal binocular field extent, measured with Goldmann kinetic perimetry (V4e target). Corrected binocular single letter VA was 20/200 or better for CFL participants, 20/25 or better for NV controls. Thus, all had vision sufficient for a restricted drivers’ license or better in some states in the U.S.A.(20) Each CFL participant had a binocular absolute central scotoma as measured with custom kinetic perimetry (21) (74 cd/m2 bright 0.74° square target, grey background (24 cd/m2), 1m distance). Binocular scotoma location was categorized left or right of the binocular PRL in visual field space (i.e., equivalent to a right PRL or left PRL, respectively). Individuals with PRLs above or below the scotoma were not included. A similar classification, based upon the relative location of the PRL and former fovea, shows moderate repeatability; kappa=0.92 for 20 eyes of 12 participants (Recker and Woods, personal communication, May 24, 2012).

Scotoma size was quantified as the average diameter of 4 main meridians passing through the center of the scotoma. For participant S3, who had several distinct scotomas, each scotoma was measured and summed. Letter contrast sensitivity (2.5° letters) was measured with a custom, computer-based test with single letter scoring, sequential decreasing contrast, and a 2-incorrect response stopping rule. (22) The results are similar to those obtained with Pelli-Robson and Mars tests for low vision patients.

Participants were recruited from the Veterans Administration, Schepens, and the Harvard Cooperative Program on Aging. Participants with cognitive decline were excluded (>4 errors on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, SPMSQ).(23) All had > 15 years of driving experience. None had previously used our simulator.

We screened 28 individuals with CFL, 11 completed the study. Eight did not meet vision criteria and nine withdrew: 2 for health reasons; 2 for simulator sickness; and 5 for other reasons (e.g., transportation difficulties). For each CFL participant, a current driver with normal vision (NV) of the same gender and age (within three years) was recruited. We screened 17, 11 completed testing and were matched to a CFL participant.

Driving simulator

The simulator has been detailed previously.(17, 24) It is a PP1000-x5 simulator (FAAC Corp., Ann Arbor, MI), with five 60×45cm CRTs (1024×768 pixels, 60Hz) providing 225° by 32° field of view.

Procedure

Two driving assessments were conducted roughly one week apart. Due to fatigue or discomfort, 5 participants completed assessments across more than 2 visits. Participants completed a series of acclimation and practice drives during which they rated their physical comfort and vehicle control on 10-point scales (“lousy” to “great”). If vehicle control was below 7, they continued to practice before progressing. Average acclimation time was 18 minutes (SD=7).

Each assessment consisted of 3 city and 2 rural undivided highway scenarios, each lasting 8-12 minutes. We encouraged participants to drive 30mph in the city and 60mph on highways and to obey all standard road rules. Participants drove different scenarios during their first and second assessments and 6 different counterbalance orders were used. Average driving time for each session was 84 minutes (SD=11).

Participants pressed the horn as soon as they detected pedestrians, that appeared every 15-60 seconds (8-12 per scenario, 52 per session) at one of four eccentricities (-14°,-4°, 4°, 14°). Pedestrians walked or ran (exhibiting biological motion) toward the road at a speed that would result in a collision with the car (Supplemental Figure S1). (25, 26) Thus pedestrians stayed in approximately the same visual field location (Figure S2), assuming the driver looked straight down the road. Although drivers may scan from side-to-side, even experienced drivers mainly look down the road in the direction of travel.(27) Pedestrians stopped before entering the participant’s lane.

Pedestrians appeared 67m/134m (city/highway) from the participant’s vehicle. These distances are double the 2.5 s perception-brake time used in the calculation of minimum recommended sight distances for safe roadway design.(28) At initial appearance the pedestrians (2m tall, light shirt, dark pants), subtended 1.5° vertical and 0.5° horizontal in the city (half that on highways). Small eccentricities (-4° and 4°) represented pedestrians approaching from an adjacent lane (crossing the street), or the sidewalk. The larger eccentricities represented hazards approaching more quickly from a greater distance (e.g., a bicyclist).

Data Analyses

Primary measures were pedestrian detection rates and reaction times (latency from pedestrian appearance to horn-press). We used logistic regression to predict whether subjects detected each pedestrian. Factors included visual field area in which each pedestrian appeared (i.e., seeing or blind), drive type (city or highway), and vision (CFL or control). For CFL participants, whether pedestrians appeared in blind or seeing areas was based on the position and size of the scotoma in the binocular visual field plot (Figure 1). Visual field area (“blind” or “seeing”) was defined for controls by their matched CFL participant.

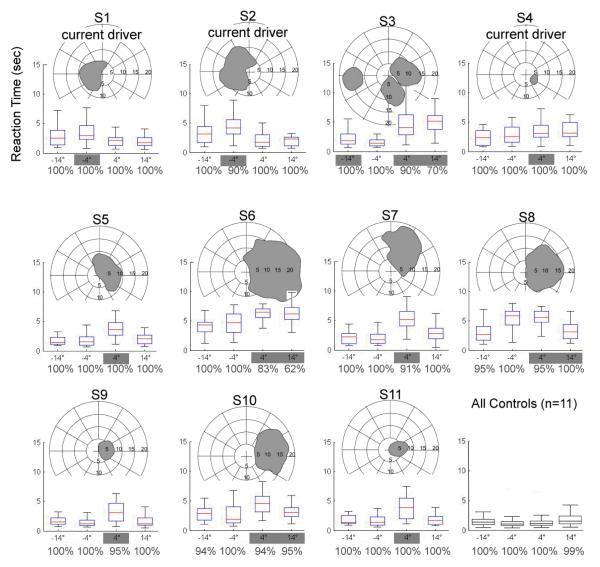

Figure 1.

Binocular visual field plots for each subject and their individual reaction times for the 4 pedestrian eccentricities (8 to 26 appearances at each eccentricity, median 22). Reaction times for the group of normally-sighted control participants are shown at bottom right. CFL subjects S1& S2 have scotomas to the left of their PRL in visual field space and were predicted to have longer reaction times to the-4° pedestrians than to pedestrians at the other 3 eccentricities; predictions for each participant are shown with gray highlight over the relevant eccentricities. Box lengths show the 25% to 75% extent and whiskers show the maximum extent of cases that are not outliers. Percentages under each plot show detection rates.

We analyzed median reaction times separately for: 1) blind and seeing visual field areas; 2) drive type (city vs. highway), and 3) first or second assessment. Medians were used because reaction times were not normally distributed. Medians did not include detection failures; these were used in the untimely reaction analysis below. The medians were normally distributed, and analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance, with area (blind/seeing), drive type, and assessment as within-subjects factors and vision (CFL/control) as a between-subjects factor (alpha was 0.05).

We calculated whether participants could have stopped in time, given their reaction time and vehicle speed, for each pedestrian appearance. A deceleration rate of 5m/s2 was used, representing a car and road both in good condition.(29) We classified each appearance as: 1) timely: pedestrian detected with enough time to stop if necessary; 2) untimely: reaction was not quick enough to stop, or the pedestrian was missed. Binary logistic regression was conducted in SPSS v.11.5 using backward stepwise entry conditional based upon significance of the Wald statistic.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Eight CFL participants had binocular scotomas to the right of their PRL (S4-S10), 2 to the left (S1, S2) and 1 to both the left and right (S3) (Figure 1). CFL participants had poorer VA and contrast sensitivity than NV participants (Table 1) and the two groups were similar for gender and age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants.

| CFL (n= 11) | NV (n= 11) | Test for group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current driver: n (%) | 3 (33%) †† | 11 (100%) | M-W U = 16.5, p = 0.002 |

| Years Driving (years)* | 44 ±17.5 [19-65] | 48 ±16.6 [23 - 70] | t(20) = 0.5 p = 0.61 |

| Years Since Stopped Driving* |

7 ±5 [0.5-13] | n/a | n/a |

| Male: n (%) | 7 (64%) | 7 (64%) | ns |

| Age (years)* | 65 ±16.2 [42-87] | 65 ±15.1 [40-84] | t(20) = 0.06, p = 0.96 |

| SPMSQ* | 10 ±0.74 [9-11] | 11 ±0.85 [9-11] | t(16) = 0.33, p = 0.75 |

| Binocular VA (logMAR)* | 0.66 ±0.24 [0.32-1] | −0.05 ±0.06 [−0.12-0.06] | t(11.3) = 9.8, p < 0.001 |

| Contrast Sensitivity (log units)* |

1.23 ±0.21 [0.85-1.5] | 1.81 ±0.13 [1.55-1.95] | t(16.8) = 7.75, p < 0.001 |

| CFL cause | |||

| AMD: n | 7 | n/a | n/a |

| Stargardt’s: n | 1 | ||

| Other†: n | 3 |

Note: some degrees of freedom are fractional as they are adjusted for inequality of variances.

Mean ±Standard deviation [Range].

optic nerve atrophy, optic nerve degeneration, and presumed ocular histoplasmosis.

one non-driver later resumed driving. In all, four participants with CFL were licensed to drive.

Detection Rates

Overall detection rates were high (Figure 1). CFL participants had more detection failures than controls, 2.7% vs. 0.3% (Wald = 14.8, df = 1, p < 0.001, Exp(β) = 10.3), and 2.1 times more misses for pedestrians in blind than seeing areas, which in turn was many times more than controls’ corresponding areas (6.4% vs. 0.2%), (Wald = 19.4, df = 1, p < 0.001, Exp(β) = 5.24). Drive type (city/highway) was not significant (p = 0.2), nor were any interactions.

Reaction Times

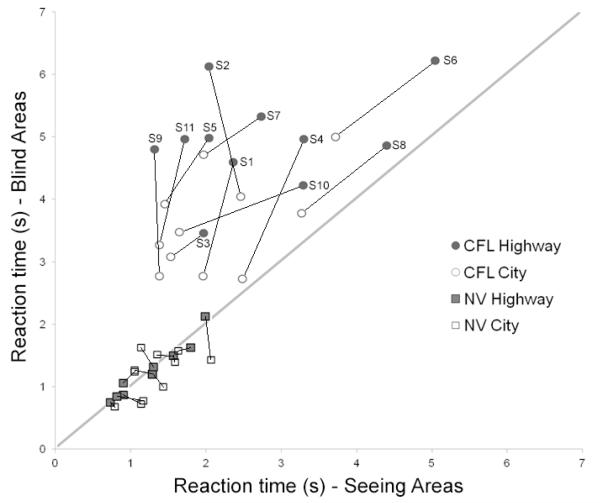

Participants reacted 0.16 seconds faster at the second assessment, but this difference was not significant (p = 0.08). Overall, CFL participants reacted significantly slower than controls (3.35 vs.1.27s) (F(1,20) = 72.5, p < 0.001; Figure 2), in both seeing and blind areas. As expected, CFL participants reacted faster in seeing than blind areas (2.43 vs. 4.28s) (F(1,21) = 50.4, p < 0.001), while controls did not differ (1.29 vs. 1.25s). For CFL participants, the difference between seeing and blind areas was greater for rural highway than city drives (interaction of drive type (city v. highway) by area within CFL subjects, F(1, 21) = 9.3, p = 0.006). Controls did not differ for drive type.

Figure 2.

Median reaction times for seeing and blind areas. Data for each participant on city and highway drives are connected by straight lines. CFLs had reaction times longer than controls, and longer to pedestrians in their blind than seeing areas (above diagonal). As expected, NVs had similar reaction times in “blind” and seeing areas. CFL medians were longer on rural highway drives (filled circles shifted up and right).

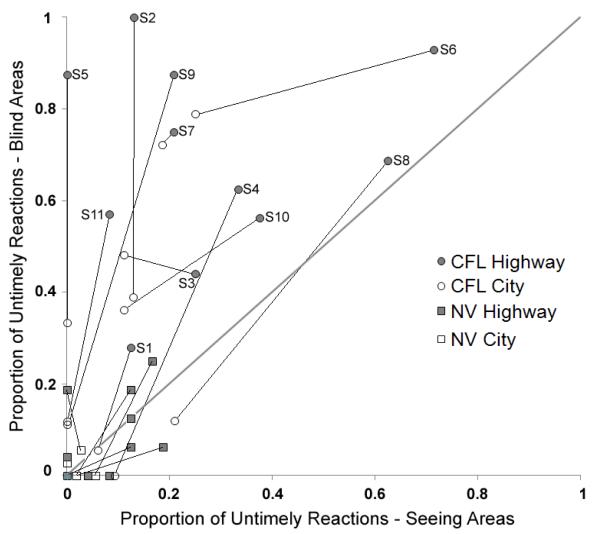

Untimely Reactions

CFL participants were more likely to have untimely reactions than controls (Wald = 44.44, df = 1, p< 0.001, Exp(β) = 0.02; Figure 3). These were to pedestrians in blind areas (50% vs 19%) for CFL participants, but not controls (5% vs 5%); vision by area interaction (Wald = 7.37, df = 1, p= 0.007, Exp(β) = 7.1; Figure 3). All participants had more untimely reactions in highway drives (48% highway vs 21% city for CFL, 8% vs 1% for controls), Wald = 9.89, df = 1, p= 0.002, Exp(β) = 0.12.

Figure 3.

Proportion of untimely reactions for seeing vs. blind areas. Data for each participant are connected by straight lines. Participants with CFL had much higher untimely reaction rates than controls, particularly in their blind areas and on rural highways. Controls also had more untimely reactions in rural highway than in city drives.

Vision Measures and Detection Performance

Larger scotomas were correlated with lower detection rates and more untimely reactions for pedestrians in blind areas on city drives (Table 2). Poorer contrast sensitivity significantly correlated with longer reaction times and more untimely reactions in seeing areas on highways and also worse detection rates in blind areas on city and highway drives. Age and VA were not correlated with the response measures. The multiple planned comparisons were not corrected.(30, 31)

Table 2.

Spearman correlations between vision and performance measures for participants with CFL (n=11).

| Visual Acuity |

Contrast Sensitivity |

Scotoma Size |

Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Times |

City, Seeing | 0.46 | −0.59 | 0.27 | −0.19 |

| City, Blind | 0.37 | −0.41 | 0.49 | 0.01 | |

| Highway, Seeing | 0.48 | −0.77 | 0.31 | −0.14 | |

| Highway, Blind | 0.39 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.14 | |

| Detection Rates |

City, Seeing | 0.31 | 0.27 | −0.09 | −0.13 |

| City, Blind | −0.01 | 0.61 | −0.76 | 0.35 | |

| Highway, Seeing | −0.48 | 0.20 | 0.00 | −0.45 | |

| Highway, Blind | −0.13 | 0.61 | −0.54 | 0.38 | |

| Untimely Reaction |

City, Seeing | 0.54 | −0.51 | 0.34 | 0.22 |

| City, Blind | 0.10 | −0.47 | 0.71 | −0.06 | |

| Highway, Seeing | 0.41 | −0.83 | 0.39 | 0.06 | |

| Highway, Blind | 0.24 | −0.10 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

Significant correlations bolded (two-tailed).

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis that lateral CFL delays reactions to pedestrian targets in scotoma areas was strongly supported. Participants with scotomas (regardless of right or left PRL) had longer reaction times to pedestrians appearing in their blind areas than in their seeing areas. One participant (S3) with scotomas on both sides had delays on both, except for the-4° targets, where there was residual vision. Despite the relatively small sample, our repeated measures of hazards at multiple eccentricities were sufficiently powerful to produce significant large median reaction time differences. Although our sample is unbalanced (8 right CFL, 2 left), the proportions are close to those reported in a larger sample.(32)

It is important to note that the longer reaction times in blind areas were due to the scotoma, and not simply due to the loss of acuity and contrast sensitivity. Such large scotoma effects might not be expected, as small eye movements might be sufficient to compensate for obscuration by a scotoma. However, in our sample, such scanning, if it took place, was not sufficient for full compensation.

The effects of CFL have been anticipated(6) but have not been previously documented due to the difficulties of studying visually impaired driving. One on-road study of mild CFL(33) used a “stunt” pedestrian and cyclist, and found no apparent differences between people with CFL and controls in reaction times. This may be because: 1) the timing of the actors could not be precisely implemented, and 2) the authors stated that actors only appeared in seeing areas of the subjects’ visual fields. Thus, in that study there was no ex post facto reason to have expected differences, except those due to acuity or contrast sensitivity.

CFL participants also had longer reactions than controls in seeing areas of their visual field. This may be due to the majority of seeing-area pedestrians appearing at larger absolute retinal eccentricities for participants with CFL, as they used non-foveal PRLs, whereas controls fixated foveally. For example, a 4° pedestrian to a participant with a 6° PRL, will be projected to 10° from the former fovea where contrast sensitivity is lower. This reduction in sensitivity did cause more substantial effects at highway speeds (as detection needed to be made at a greater distance).

By comparison, in a recent study of drivers with para-central scotomas, who used foveal fixation and thus had VA and contrast sensitivity similar to that of NV drivers, there were no significant delays to pedestrian figures in seeing areas of their visual field using the same methods.(34) Supporting the retinal eccentricity hypothesis, NV participants had longer reaction times to pedestrians at the larger (+/-14°) eccentricities than the small (+/-4°) by 0.3 s, paired t(10) = 5.9, p<.001.

Despite deploying pedestrians at double the perception-brake sight distance in the AASHTO guidelines (28) (2×2.5s travel time), CFL participants frequently did not react in a timely fashion, especially in rural highway drives (69% untimely, blind areas, 28% seeing). Timely detections on highways were challenging even for normally-sighted participants (8% untimely) because doubling speed quadruples stopping distance.

Our primary measure was how quickly the pedestrian was detected. We also derived the measure “untimely reactions”, including vehicle speed and distance to the pedestrian, which imparts more real-world meaning to the measurement. We did not measure actual collisions and we did not consider other possible maneuvers to avoid collisions. An advantage of simulator-based studies is that pedestrian challenges are safe, controlled, and more frequent than in on-road studies, enabling reliable measurement of response latencies. The greater frequency in the simulator should have primed the participants, making it easier for them to anticipate the events. In the real world, such occurrences would be unexpected and therefore would probably result in longer reaction times. It is not uncommon in mobility research to include events at a higher frequency or higher density than in the real world in order to have sufficient events for analysis.(35) (36)

Larger scotomas were significantly correlated with poorer blind-area detection performance; larger blind areas should make it more difficult to detect pedestrians in that area. That contrast sensitivity correlated with worse detection rates in blind areas may be due to its correlation with scotoma size. For the acuity range of our CFL participants (20/40 to 20/200), VA was uncorrelated with performance measures, despite being the primary vision screening measure for licensing in the U.S. Higgins has pointed out that VA should not be expected to correlate with outcome measures when there are range restrictions. (37) We should note that within our CFL or within our NV groups, VA was not correlated with performance measures. However, across all our subjects, VA was correlated with most performance measures.

Our CFL participants had vision sufficient for a restricted driver’s license in some U.S. states, but not in the U.K or Canada because of their CFL.(6, 7) Although most had stopped driving, all had considerable driving experience, and the three who were current drivers had blind-area reaction times similar to the others.

In conclusion, people who fixate lateral to a binocular scotoma, showed relatively late reactions to potential hazards that appeared in scotoma locations. Vertical PRLs, more common in Juvenile macular degeneration, may have a lesser impact on hazard detection, but confirmation is needed. Contrast sensitivity may also help differentiate those who are fit to drive. However, none of these measures is currently considered in driver licensing in the U.S. CFL may affect driving safety independent from its effect on acuity; thus CFL patients may be more vulnerable to hazards than other drivers with reduced acuity alone.

Our study was not designed to oppose nor advocate for people with visual impairments as drivers. However, knowledge about how specific aspects of vision loss (CFL, VA, and CS) affect certain aspects of performance should help improve vision rehabilitation and the design of mobility aids. The results may help practitioners in advising CFL patients about difficulties they may face when driving.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Christina Gambacorta, Egor Ananev, and Alex Hwang made helpful comments on the manuscript. Joseph Rizzo (Center for Innovative Visual Rehabilitation, Veterans Administration Boston Healthcare System), provided the simulator. The Harvard Cooperative Program on Aging assisted in recruitment. Supported by National Institutes of Health grants EY12890 (EP), EY018680 (ARB), and 2P30EY003790, which had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis or writing. The first author had full access to all study data and is responsible for data integrity and analysis accuracy.

References

- 1.Sunness JS, Applegate CA, Haselwood D, Rubin GS. Fixation patterns and reading rates in eyes with central scotomas from advanced atrophic macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1458–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petzold A, Plant GT. Central and paracentral visual field defects and driving abilities. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219:191–201. doi: 10.1159/000085727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timberlake GT, Peli E, Essock EA, Augliere RA. Reading with macular scomata II: Retinal locus for scanning text. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;28:1268–121274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verezen CA, Hoyng CB, Meulendijks CF, Keunen JE, Klevering BJ. Eccentric gaze direction in patients with central field loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2011;88:1164–1171. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31822891e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher DC, Schuchard RA. Preferred retinal loci relationship to macular scotomas in a low-vision population. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:632–638. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauscher FG, Chisholm CM, Crabb DP, et al. Central Scotomata and Driving. Department of Transport; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazdan-Ashoori P, ten-Hove M. Vision and Driving: Canada. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30:177–185. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181dfa982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peli E. Low vision driving in the USA: who, where, when, and why. CE Optometry. 2002;5:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangione CM, Berry S, Spritzer K, Janz NK, Klein R, Owsley C, Lee PP. Identifying the content area for the 51-item National Eye Institute visual function questionnaire. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1998;116:227–233. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scilley K, Jackson GR, Cideciyan AV, Maguire MG, Jacobson SG, Owsley C. Early age-related maculopathy and self-reported visual difficulty in daily life. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1235–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball K, Owsley C, Stalvey B, Roenker DL, Sloane ME, Graves M. Driving avoidance and functional impairment in older drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1998;30:313–322. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szlyk JP, Pizzimenti CE, Fishman GA, et al. A comparison of driving in older subjects with and without age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1033–1040. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100080085033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeCarlo DK, Scilley K, Wells J, Owsley C. Driving habits and health-related quality of life in patients with age-related maculopathy. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2003;80:207–213. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowers AR, Apfelbaum DH, DeCarlo D, Peli E. Use of bioptic telescopes by drivers with age-related macular degeneration (abstract) Investigative Ophthalmological & Visual Science. 2007;48:2351. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szlyk JP, Fishman GA, Severing K, Alexander KR, Viana M. Evaluation of driving performance in patients with juvenile macular dystrophies. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1993;111:207–212. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090020061024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coeckelbergh TRM, Brouwer WH, Cornelissen FW. Predicting practical fitness to drive in drivers with visual field defects caused by ocular pathology. Hum. Factors. 2004;46:748–760. doi: 10.1518/hfes.46.4.748.56818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowers AR, Mandel AJ, Goldstein RB, Peli E. Driving with hemianopia: 1. Detection performance in a driving simulator. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:5137–5147. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owsley C, McGwin G., Jr. Vision and driving. Vision Res. 2010;50:2348–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowers AR, Peli E, Elgin J, McGwin G, Owsley C. On-road driving with moderate visual field loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2005;82:657–667. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000175558.33268.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peli E, Peli D. Driving with Confidence: A Practical Guide to Driving with Low Vision. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; Singapore: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods RL, Apfelbaum HL, Peli E. DLP-based dichoptic vision test system. J. Biomed. Optics. 2010;15:1–13. doi: 10.1117/1.3292015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arditi A. Improving the design of the letter contrast sensitivity test. Investigative Ophthalmological & Visual Science. 2005;46:2225–2229. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peli E, Bowers AR, Mandel AJ, Higgins K, Goldstein RB, Bobrow L. Design of driving simulator performance evaluations for driving with vision impairments and visual aids. Transport. Res. Record: J. Trans. Res. Board. 2005;1937:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regan D, Kaushal S. Monocular discrimination of the direction of motion in depth. Vision Res. 1994;34:163–177. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chardenon A, Montagne G, Buekers MJ, Laurent M. The visual control of ball interception during human locomotion. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;334:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01000-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underwood G. Visual attention and the transition from novice to advanced driver. Ergonomics. 2007;50:1235–1249. doi: 10.1080/00140130701318707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American_Association_of_State_Highway_and_Transportation_Officials . A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. AASHTO; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans L. Traffic Safety. Science Serving Society; Bloomfield Hills, Michigan: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC medical research methodology. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing--when and how? Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2001;54:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verezen CA, Hoyng CB, Meulendijks CF, Keunen J, Klevering BJ. Eccentric gaze direction in patients with central field loss. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2011;88:1164–1171. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31822891e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamble D, Summala H, Hyvarinen L. Driving performance of drivers with impaired central visual field acuity. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2002;34:711–716. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bronstad PM, Bowers AR, Albu A, Goldstein RG, Peli E. Hazard detection by drivers with paracentral homonymous field loss: A small case series. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2011;S5:001. doi: 010.4172/2155-9570.S4175-4001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuhr PS, Liu L, Kuyk TK. Relationships between feature search and mobility performance in persons with severe visual impairment. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2007;84:393–400. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31804f5afb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood JM, Chaparro A, Lacherez P, Hickson L. Useful field of view predicts driving in the presence of distracters. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2012;89:373–381. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31824c17ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins KE. Low vision driving among normally-sighted drivers. In: Rosenthal B, Cole R, editors. Remediation and Management of Low Vision. St. Louis; MO, Mosby: 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.