Abstract

Locked in syndrome is typically associated with significant morbidity and mortality. We report a patient who had an unusually good recovery from locked in syndrome due to pontine infarction. The good recovery exhibited by our patient may have resulted from resolution of oedema at the site of infarction and brainstem plasticity being augmented by initial supportive measures in the intensive care unit and early, intensive rehabilitation.

INTRO

The term ‘locked in’ refers to the syndrome of tetraplegia and anarthria with preserved awareness. It was first coined by Plum and Posner in 1966, and is usually due to a lesion of the ventral pons1. It was initially believed to have a grim prognosis, but prolonged survival has been demonstrated in some cases in the last three decades2-4. The condition continues to have significant associated mortality and morbidity, and considerable functional impairment persists in the vast majority of survivors2-4. We report a patient who was ‘locked-in’ due to bilateral pontine infarction, who exhibited an unusually good functional recovery.

CASE REPORT

A 37 year-old previously well female, with a history of migraine with aura, with no other known vascular risk factors experienced a transient episode of diplopia, vertigo and vomiting with subsequent complete recovery. She felt that this was an unusual for her typical aura. The following day she was found unresponsive in her car, with no evidence to suggest a road traffic accident had occurred. Leg twitching was observed by paramedics, and the patient was intubated, ventilated, and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at a district general hospital where a computed tomography (CT) brain scan demonstrated no abnormality. She was subsequently transferred to the regional ICU on the following day, and on sedation withdrawal she was breathing spontaneously, but tetraplegic and anarthric. Full range of eye movements was observed and upper eyelid movements were preserved, which facilitated appropriate ‘yes/no’ responses. A clinical diagnosis of locked-in syndrome was made and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain demonstrated bilateral pontine and right cerebellar infarction (Figure 1). These areas exhibited restricted diffusion, consistent with acute infarction. A magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of her intra-cranial vessels was normal, indicating presumed spontaneous recanalisation of the basilar artery. Full blood count, inflammatory markers, fasting glucose, renal and liver function tests were all normal. Fasting lipid profile revealed and elevated cholesterol (6.16 mmol/L) and triglycerides (4.63 mmol/L) levels, and a raised cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio. A thrombophilia screen was negative, and no abnormality was detected in an electrocardiograph or transoesophageal echocardiogram.

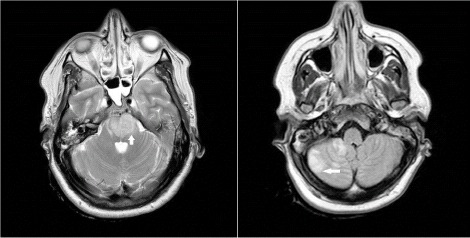

Fig 1a & b.

T2-weighted axial MRI brain demonstrating bilateral pontine and right cerebellar infarction (August 2008)

A method of communication was established using her preserved eye and upper eyelid movements, similar to that described in a previous review of LIS5. Aspirin and atorvastatin were commenced for vascular disease secondary prevention. Two weeks after her initial presentation, she was transferred to a neurology ward at which stage she remained anarthric and tetraplegic. There was early and intensive involvement from physiotherapists (PT), occupational therapists (OT) and speech and language therapists (SALT). A gastrostomy feeding tube was inserted and she also had early and regular review by the neurorehabilitation team. She remained completely quadriplegic for three weeks and completely anarthric for six weeks. At three weeks, a flicker of voluntary left leg movement was observed. Subsequently, she exhibited a slow but surprisingly continual recovery in limb power initially and bulbar function later (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of recovery

| Initial assessment | Transfer to RABIU (8 weeks) | Discharge from RABIU (18 weeks) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech | Anarthric | Significant dysarthre | Easily intelligible |

| Swallo | Nil by mouth | Soft diet | Soft-normal diet |

| Transfers | Hoist | Hoist | Independent |

| Walking | Not applicable | Rollator, maximum assistance of 2 | Independent |

| 10m walk time | Not applicable | 1 min 30 secs | 10 secs (witk rollator) 42 secs (independently) |

| Activities of daily living (ADLs) | Assistance with all ADLs | Assistance with all ADLs | Independent with all ADLs |

Eight weeks after her ictus, she was transferred to the Regional Acquired Brain Injury Unit (RABIU). At that point, she had significant dysarthria and could only safely swallow soft foods. She required a hoist for all transfers and could walk using a rollator with the maximum assistance of two physiotherapists. Her 10 metre walking time was 1 minute and 39 seconds. Functionally she required assistance with all activities of daily living (ADLs). During a ten week in-patient stay at RABIU, with ongoing multi-disciplinary rehabilitation team input, her recovery continued. On discharge from RABIU 18 weeks after her initial presentation, her speech was easily intelligible and she was managing a soft to normal diet safely. She was independent with all ADLs, transfers and could walk independently, but preferred the additional security of a rollator, her 10 metre walking time being 18 seconds. An MRI brain was repeated 9 months after her symptom onset, which demonstrated an extensive gliotic scar incorporating nearly all of the left pons (Figure 2). She has continued to improve since discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and is considering a return to employment.

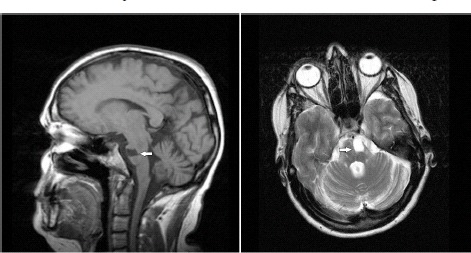

Fig 2a & b.

T1-weighted sagittal and T2-weighted axial MRI brain demonstrating an extensive left pontine gliotic scar (May 2009)

Discussion

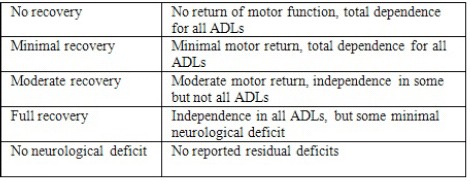

Despite the improvements in outcomes from LIS reported in recent decades, the degree of recovery experienced by our patient is notable. A sub-classification of LIS exists in which Plum and Posner's original description, where vertical eye movements are the only preserved motor activity, is termed the classical form6. Incomplete LIS is similar to the classical variety but also has remnants of other voluntary movements in addition to vertical eye movements. Using this sub-classification, our patient initially had incomplete LIS as there was preservation of horizontal eye movements. However, she was undoubtedly at the most extreme limit of the incomplete LIS sub-category. The only classification scale of recovery from LIS is for motor recovery (Figure 3), and has been used in the majority of the literature relating to LIS recovery and outcomes2. In accordance with this scale, our patient exhibited a ‘full recovery’ of motor function. Table 2 summarises the 15 previous cases of LIS that we considered to be comparable to our case, in terms of aetiology (vascular), initial severity and duration of locked-in state and extent of recovery3, 6-14. Very few prognostic indicators pertaining to LIS exist, but non-vascular aetiologies and early preservation of horizontal eye movements have been associated with better outcomes2, 10. Horizontal eye movements are initiated in the brainstem in the paramedian pontine reticular formation beside the sixth nerve nucleus in the pons. Vertical eye movements are initiated higher in the brainstem in the midbrain and diencephalon15. The favourable outcome sometimes associated with preserved horizontal eye movements in LIS is believed to be reflective of a more limited pontine lesion.

Fig 3.

Classification of recovery from LIS

Table 2.

Comparable cases

| Authors | Year | Journal | Total cases (n) | Comparable Recovery (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer et al | 1979 | J Neurol | 12 | 2 |

| Kurana et al | 1980 | Ann Neurol | 3 | 3 |

| McCusker et al | 1982 | Arch Neurol | 4 | 1 |

| Ebinger et al | 1985 | Int Care Med | 2 | 1 |

| 1989 | Yang et al | Arch Phys Med Rehab | 1 | 1 |

| Richard et al | 1995 | Paraplegia | 11 | 2 |

| 2003 | Casanova et al | Arch Phys Med Rehab | 14 | 1 |

| Doble et al | 2003 | Arch Phys Med Rehab | 29 | 0 |

| New et al | 2005 | Arch Phys Med Rehab | 1 | 1 |

| Heyer et al | 2010 | Brain Injury | 9 | 2 |

| Leema & Schinider | 2010 | Rev Med Suisse | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 15 |

The impressive recovery observed in our patient may partly be explained by an eventual resolution of oedema surrounding the site of infarction. In addition, the development of a large gliotic scar encompassing the left pons on her repeat MRI scan (Figure 2) in a patient with marked and symmetrical motor recovery is suggestive of a degree of brainstem plasticity. These intrinsic mechanisms of recovery are also likely to be supplemented by the initial supportive care she received in ICU and her subsequent rehabilitation. Improved long-term survival rates and functional outcomes have been observed in patients who had early and intensive rehabilitation2, 4, 14. Furthermore, in the cases comparable to ours, all had access to critical care environments if necessary and initiated intensive rehabilitation early at dedicated rehabilitation units.

In summary, this case demonstrates an unusually good functional outcome following LIS from pontine infarction. Similarly good outcomes from LIS have rarely been reported. In concordance with previous reports, there was good recovery after early intensive rehabilitation. Such cases also strengthen the claim that the full range of supportive therapies, including management in critical care units, should be considered in patients presenting with LIS.

The author has declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plum F, Posner JB. Contemporary neurology series. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 1966. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson JR, Grabois M. Locked-in syndrome: a review of 139 cases. Stroke. 1986;17(4):758–64. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doble JE, Haig AJ, Anderson C, Katz R. Impairment, activity, participation, life satisfaction, and survival in persons with locked-in syndrome for over a decade: follow-up on a previously reported cohort. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18(5):435–4. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova E, Lazzari RE, Lotta S, Mazzucchi A. Locked-in syndrome: improvement in the prognosis after an early intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(6):862–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith E, Delargy M. Locked-in syndrome. BMJ. 2005;330(7488):406–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7488.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer G, Gerstenbrand F, Rumpl E. Varieties of the locked-in syndrome. J Neurol. 1979;221(2):77–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00313105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khurana RK, Genut AA, Yannakakis GD. Locked-in syndrome with recovery. Ann Neurol. 1980;8(4):439–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.410080418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCusker EA, Rudick RA, Honch GW, Griggs RC. Recovery from the ‘locked-in’ syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1982;39(3):145–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510150015004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebinger G, Huyghens L, Corne L, Aelbrecht W. Reversible “locked-in” syndromes. Intensive Care Med. 1985;11(4):218–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00272409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang CC, Lieberman JS, Hong CZ. Early smooth horizontal eye movement: a favorable prognostic sign in patients with locked-in syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70(3):230–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richard I, Pereon Y, Guiheneu P, Nogues B, Perrouin-Verbe B, Mathe JF. Persistence of distal motor control in the locked in syndrome. Review of 11 patients. Paraplegia. 1995;33(11):640–6. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New PW, Thomas SJ. Cognitive impairments in the locked-in syndrome: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(2):338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoyer E., et al. Rehabilitation including treadmill therapy for patients with incomplete locked-in syndrome after stroke; a case series study of motor recovery. Brain Inj. 24(1):34–45. doi: 10.3109/02699050903471805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leemann B, Schnider A. [Unusually favorable recovery from locked-in syndrome after basilar artery occlusion] Rev Med Suisse. 2010;6(241):633–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The neurology of eye movements. Contemporary neurology series. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]