Graphical abstract

Highlights

► The distribution of GABAA receptor subunits is highly heterogeneous. ► The distribution of mRNAs corresponds to that of proteins. ► The distribution in the mouse correlates largely to that in rats although there are distinct differences.

Abbreviations used in the text: CA, cornu ammonis; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISH, in situ hybridization; TBS, Tris–HCl-buffered saline

Abbreviations used in Figure legends: BLA, basolateral amygdala; CEA, central amygdala; DG, dentate gyrus; DLG, dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus; DS, dorsal subiculum; Ent, entorhinal cortex; EP, entopeduncular nucleus; EPl, external plexiform layer; Gl, glomerular layer bulbus olfactorius; GP, globus pallidus; gr, granule cell layer bulbus olfactorius; Gr, granule cell layer cerebellum; h, hilus; Hb, habenula; I, intercalated nucleus; LD, laterodorsal thalamic nucleus; MA, medial amygdaloid nucleus; Mi, mitral cell layer bulbus olfactorius; ml, molecular layer of dentate gyrus; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; Mol, molecular layer cerebellum; PaS, parasubiculum; PG, pregeniculate nucleus; PrS, presubiculum; PV, paraventricular thalamic nucleus; Rt, reticular thalamic nucleus; so, stratum oriens; sr, stratum radiatum; St, striatum; STT, spinal trigeminal tract; VPL, ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus; VPM, ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus; VS, ventral subiculum

Key words: GABAA receptor subunits, mouse brain, in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry

Abstract

The GABAA receptor is the main inhibitory receptor in the brain and its subunits originate from different genes or gene families (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1–γ3, δ, ε, θ, π, or ρ1–3). In the mouse brain the anatomical distribution of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs so far investigated is restricted to subunits forming benzodiazepine-sensitive receptor complexes (α1–α3, α5, β2, β3 and γ2) in the forebrain and midbrain as assessed by in situ hybridization (ISH). In the present study the anatomical distribution of the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1–γ2 and δ was analyzed in the mouse brain (excluding brain stem) by ISH and immunohistochemistry (IHC). In several brain areas such as hippocampus, cerebellum, bulbus olfactorius and habenula we observed that mRNA levels did not reflect protein levels, indicating that the protein is located far distantly from the cell body. We also compared the distribution of these 12 subunit mRNAs and proteins with that reported in the rat brain. Although in general there is a considerable correspondence in the distribution between mouse and rat brains, several species-specific differences were observed.

Introduction

The GABAA receptor is the main inhibitory receptor in the brain. It is composed of five subunits that form a central chloride channel. Depending on the chloride gradient at the cell membrane that is built up by the chloride transporters NKCC1 and KCC2 (Owens and Kriegstein, 2002), stimulation of the GABAA receptor by GABA results in a hyperpolarizing (chloride influx). Under conditions of high intracellular chloride concentrations stimulation of the GABAA receptor can also result in depolarization. GABAA receptor subunits originate from different genes or gene families (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1–γ3, δ, ε, θ, π, or ρ1–3). The majority of GABA receptors in the brain consists of two α-subunits, two β-subunits and one γ- or δ-subunit. The most abundant subunit combination consists of two α1-, two β2-subunits and one γ2-subunit. The subunit constitution determines the physiological and pharmacological properties of the GABAA receptors. Thus GABAA receptors containing subunits α1, α2, α3, or α5, together with two β subunits and a γ subunit respond to benzodiazepines or the hypnotic substance zolpidem. These and other compounds exert their action via the benzodiazepine-binding site, located at the αγ interface of GABAA receptors (Richter et al., 2012). The two GABA binding sites of these receptors are located at the two βα interfaces (Ernst et al., 2003).

In the rat brain the distribution of the various GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs and proteins has been examined in detail (Laurie et al., 1992; Wisden et al., 1992; Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Sperk et al., 1997; Tsunashima et al., 1997; Pirker et al., 2000; Schwarzer et al., 2001). In the mouse brain knowledge of the anatomical distribution of mRNAs of the GABAA receptor subunits is focused on those forming benzodiazepine-sensitive receptor complexes (α1–α3, α5, β2, β3 and γ2) in the fore- and midbrain, without inclusion of the bulbus olfactorius and cerebellum (Heldt and Ressler, 2007a). Each gene has been shown to have a unique region-specific distribution pattern. The distribution of other subunit mRNAs and proteins (α4, α6, β1, γ1 and δ) has been studied in individual brain regions of the mouse brain so far (e.g. Kato, 1990; Jones et al., 1997; Peng et al., 2002, 2004; Prenosil et al., 2006; Sassoè-Pognetto et al., 2009; Tasan et al., 2011; Marowsky et al., 2012).

It is noteworthy that the benzodiazepine-insensitive α4-, α6- and δ-subunits are predominantly or exclusively extrasynaptic providing preferentially tonic inhibition (for review see Farrant and Nusser, 2005). Therefore the knowledge of their anatomical distribution in the mouse brain is of considerable importance. In the rat the δ subunit is known to form receptors specifically with the α6- and β2/3-subunits in cerebellar granule cells and with α4 and βx in several areas of the forebrain including thalamus, neostriatum and dentate gyrus (for review see Farrant and Nusser, 2005). Interestingly, in mice α4-, α5-, α6- and δ-subunit-containing GABAA receptors were shown to be present exclusively in the extrasynaptic somatic and dendritic membranes of cerebellar granule cells as well as extrasynaptic and peri-synaptic locations in hippocampal dentate gyrus granule cells (Wie et al., 2003). These predominantly extrasynaptic GABAA receptors are sensitive to neurosteroids and have been implicated in altered seizure susceptibility and altered states of anxiety during the ovarian cycle and in postpartum depression (Maguire et al., 2005; Maguire and Mody, 2008). Recent evidence indicates that mutations of the δ-subunit-containing GABAA receptors are associated with a reduction in channel open duration, resulting in an increased neuronal excitability and thus contributing to the common generalized epilepsies (Feng et al., 2006; Lu and Wang, 2009). In addition, evidence for a role for tonic inhibition mediated by δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors in neuroprotection against excitotoxic insults in the adult mice striatum has been provided (Santhakumar et al., 2010).

Significant differences in GABAA receptor composition between rat and mouse brain have been detected. Particular brain areas of mRNA variance between mice and rats include the subthalamic nucleus, medial septum, thalamus and amygdala (Heldt and Ressler, 2007a). The total percentage of δ-containing receptors in mouse cerebellum was significantly higher than in the rat cerebellum (Pöltl et al., 2003).

Discrepancies also exist concerning the presence of the α5-subunit in the cerebellum of rat and mouse. According to Laurie et al. (1992) α5-subunit mRNA is not detectable in the rat cerebellum, whereas the expression of α5-subunit mRNA has been described in granule cells (Persohn et al., 1992). On the protein basis small but significant quantities of α5-subunit protein seem to be present in rat, but not in mouse (Pöltl et al., 2003) and moderate immunoreactivity was detected throughout the rat cerebellum (Pirker et al., 2000). On the other hand, on mapping the rat brain distribution of α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors using quantitative autoradiography with the α5-selective ligand [3H]L-655,708, no binding was detected in the cerebellum (Sur et al., 1999).

The aim of the present investigation was to complete the anatomical distribution of mRNAs for 12 GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse brain by in situ hybridization (ISH) and to define the anatomical distribution of these GABAA receptor subunits at the protein level by immunohistochemistry (IHC). The juxtaposition of ISH and IHC results will provide a better overview about synthesis and final location of each individual subunit. Moreover, differences in the distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse and rat brains will be discussed at the mRNA and protein level.

Experimental procedures

Animals

All procedures involving animals and animal care were conducted in accordance with international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 86/609, OJ L 358, 1, December 12, 1987; Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals, U.S. National Research Council, 1996) and were approved by the Austrian Ministry of Science. All effort was taken to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Experiments were carried out on adult male C57Bl/6NCrl mice (n = 23) at 12–15 weeks of age obtained from Charles River (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) and consequently bred in the animal facility of the Department of Pharmacology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria. Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions (12:12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00) with food and water available ad libitum. Mice were housed in groups of 4–5 animals per cage.

Histochemistry

Tissue preparation

Mice were killed by carbon dioxide gas inhalation or by injecting an overdose of thiopental (Thiopental, Sandoz, Austria) for ISH or IHC, respectively. Brains were either snap frozen (isopentane, −70 °C, 3 min) for ISH or perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde for IHC (Tasan et al., 2010). Using a cryostat, coronal sections of 20 and 40 μm were cut for ISH and IHC, respectively. Every 7th section was Nissl stained and a series of matching sections were selected for subsequent histochemistry.

ISH

ISH was performed as described previously in detail (Tsunashima et al., 1997; Tasan et al., 2010). Oligonucleotide probes targeting diverse subunits of the GABAA receptor are listed in Table 1. They were custom synthesized (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland, purified by HPLC). Oligonucleotides (2.5 pmol) were 3′ end-labeled by incubation with [35S]α-dATP (50 μCi; 1300 Ci/mmol, Hartmann Analytic GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) and terminal transferase (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), as described previously in detail (Tsunashima et al., 1997). Hybridization was performed in 50% formamide, 4× SSC (1× SSC is 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.2), 500 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, 250 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 1× Denhardt’s solution (0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 0.02% bovine serum albumin), 10% dextran sulfate, and 20 mM dithiothreitol (all from Sigma) at 42 °C for 18 h. The slides containing the sections were washed at stringent conditions (50% formamide in 2× SSC, 42 °C) and briefly rinsed in water followed by 70% ethanol, and dried. Sections were exposed to BioMax MR films (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) together with [14C]-microscales for 7 to 14 days. The BioMax MR films were developed with Kodak D19 developer. Sections were counterstained with Cresyl Violet, dehydrated, cleared in butyl acetate, and covered with a coverslip using Eukitt (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequence for in situ hybridization

| mRNA | Access code | Oligonucleotide sequence |

|---|---|---|

| α1 | NM_010250.3 | 5′ CCT GGC TAA GTT AGG GGT ATA GCT GGT TGC TGT AGG AGC ATA TGT 3′ |

| α2 | NM_008066.3 | 5′ CAT CGG GAG CAA CCT GAA CGG AGT CAG AAG CAT TGT AAG TCC 3′ |

| α3 | NM_008067.3 | 5′ GGC CAG ATT GAT AGG ATA GGT GGT ACC CAC TAT GTT GAA GGT GGT G 3′ |

| α4 | NM_010251.2 | 5′ GGA TGT TTC TGT GTG TTT CTC CTT CAG CAC AGG AGC AGC TGG 3′ |

| α5 | NM_176942.3 | 5′ TTG GGA TGT TTG GAG GAT GGG TCA GCT TTC CAG TTG T 3′ |

| α6 | NM_001099641 | 5′ GCT GAT TCT CTT CTT CAG ATG GTA CTT GGA GTC AGA GTG CAC AAC 3′ |

| β1 | NM_008069.4 | 5′ TGC CTG TCC AGC CCA CGC CCG AAG CCC TCG CGG CTG CTC AGT GG 3′ |

| β2 | NM_008070.3 | 5′ ACT GTT TGA AGA GGA ATC CAG TCC TTG CTT CTC ACG GAA GGC TG 3′ |

| β3 | NM_001038701.1 | 5′ CTG TCT CCC ATG TAC CGC CCA TGC CCT TCC TTG GGC ATG CTC TGT 3′ |

| γ1 | NM_010252.4 | 5′ GGG AAT GAG AGT GGA TCC AGC ATG GAG ACC TGG GGA 3′ |

| γ2 | NM_008073.2 | 5′ GGC AAT GCG AAT ATG TAT CCT CCC ATG TCT CCA GGC TCC TGT TCG GC 3′ |

| δ | NM_008072.1 | 5′ GGC AAG GTC CAT GTC ACA GGC CAC TGT GGA GGT GAT GCG GAT GCT GTA T 3′ |

Semi-quantitative evaluation of ISH was done using digitized images of the autoradiographs (Epson Perfection 4870 Photo; eight bit digitized picture, 256 gray values). Gray values were measured by the public domain program ImageJ 1.38x (NIH, USA; 255 = white; 0 = black) and converted to relative optical density. Relative optical density values obtained from autoradiographic images were plotted against standard curves obtained from images of [14C]-microscales exposed to the same film to ensure that signal values are within the linear range of radioactivity. Each value was obtained from the innermost 90% of the respective brain area. Adjacent background levels with no hybridization signal (internal capsule) were obtained separately for each brain section and side. The anatomical level was verified in sections counterstained with Cresyl Violet using a mouse brain atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 2007).

IHC

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on free-floating, paraformaldehyde-fixed, 40-μm thick coronal sections using indirect peroxidase labeling, as described previously (Tasan et al., 2011). Polyclonal rabbit antisera against the indicated residues of the GABAA receptor subunits used are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identity, source and characterization of antibodies

| GABAA receptor subunit | Code | Host | Epitope | Protein concentration (μg/ml) | Dilution for IHC | Incubation | Previously used in study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1-subunit | α1N | Rabbit | residue 1–9 | 592 | 1:150 | 72 h at 4 °C | |

| α2-subunit | α2C | Rabbit | residue 416–424 | 540 | 1:100 | 24 h at RT | |

| α2-subunit | α2L | Rabbit | residue 322–357 | 290 | 1:15 | 72 h at 4 °C | 4 |

| α3-subunit | α3N | Rabbit | residue 1–11 | 837 | 1:150 | 24 h at RT | 1, 2 |

| α4-subunit | α4N | Rabbit | residue 1–14 | 600 | 1:300 | 72 h at 4 °C | |

| α4-subunit | α4L | Rabbit | residue 379–421 | 623 | 1:2000 | 72 h at 4 °C | 4 |

| α5-subunit | α5L | Rabbit | residue 337–380 | 410 | 1:100 | 24 h at RT | 3 |

| α6-subunit | α6 | Rabbit | residue 429–434 | 350 | 1:70 | 72 h at 4 °C | 1, 2 |

| β1-subunit | β1L | Rabbit | residue 350–404 | 360 | 1:300 | 72 h at 4 °C | |

| β1-subunit | β1L2 | Rabbit | residue 350–375 | 453 | 1:200 | 24 h at RT | 4 |

| β2-subunit | β2L | Rabbit | residue 351–404 | 684 | 1:200 | 24 h at RT | 5 |

| β3-subunit | β3L | Rabbit | residue 345–408 | 479 | 1:200 | 24 h at RT | 4, 5 |

| γ1-subunit | γ1L | Rabbit | residue 324–366 | 210 | 1:100 | 24 h at RT | 1, 2 |

| γ2-subunit | γ2L | Rabbit | residue 319–366 | 270 | 1:300 | 72 h at 4 °C | |

| δ-subunit | δN | Rabbit | residue 1–44 | 449 | 1:300 | 72 h at 4 °C | 1, 2, 3 |

RT: room temperature; IHC: immunohistochemistry.

The respective antibodies were previously used in the following studies:

1. Sperk et al. (1997), rat; 2. Pirker et al. (2000), rat; 3. Scimemi et al. (2005), rat; 4. Tasan et al. (2010), mouse; 5. Pirker et al. (2003), human.

In brief, free-floating coronal sections were incubated in 10% normal goat serum (Biomedica, Vienna, Austria) in Tris–HCl-buffered saline (TBS; 50 mM, pH 7.2) for 90 min, followed by incubation with primary antiserum (24 h at room temperature or 72 h at 4 °C as indicated for the different GABAA receptor subunits). The resulting complex was visualized by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (1:250 P0448; Dako, Vienna, Austria) at room temperature for 150 min. Sections were further incubated in a solution containing 0.03% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.005% H2O2 in TBS for 6 min. They were then mounted on slides, air-dried, dehydrated and coverslipped. After each incubation step (with the exception of preincubation with 10% normal goat serum), sections were washed three times for 5 min each with TBS. All buffers and antibody dilutions, except the buffer used for washing after peroxidase treatment and the diaminobenzidine reaction buffer, contained 0.4% Triton X-100. Normal goat serum (10%) was included in all buffers containing antibodies. In each experiment, sections without primary antibody were included as a control. No immuno-positive elements were detected in these control sections.

Knock out mice were provided by Dr. Delia Belelli, Neurosciences Institute, Division of Pathology and Neuroscience, University of Dundee, UK for subunit α2 (Panzanelli et al., 2011) and β2 (Blednov et al., 2003), by Prof. Jean-Marc Fritschy, Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Zurich, Switzerland for subunit α3 (Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2008) and by Dr. Gregg E. Homanics, Departments of Anesthesiology/Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, USA for subunit δ (Mihalek et al., 1999). The animals were perfused with paraformaldehyde as described above, 40μm sections were obtained at the level of the dorsal hippocampus and the amygdala and incubated (together with sections from wild type mice) with the respective antibodies. Whereas the sections from wild type mice revealed clear labeling of the respective GABAA receptor subunits, no labeling was obtained in the respective knock out mice.

Results

Overall distribution of individual GABAA receptor subunits at the mRNA and protein level

In Figs. 1–6 the overall mRNA and protein distribution of 12 different GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse brain is presented in two horizontal and one sagittal section. In general, the localization of mRNA resembled that of the protein. The regional distribution of the individual GABAA receptor subunit was rather heterogeneous. The localization of the α6 subunit mRNA and immunoreactivity was largely restricted to the cerebellum, where mRNA and protein were abundantly expressed. A faint immunoreactivity of the α6-subunit was also detected in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and spinal trigeminal tract (see Fig. 6). With the exception of the striatum, the α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits displayed the most widely distributed mRNAs and immunoreactivities. This distribution is in good agreement with previous ISH data and immunohistochemical data in the rat brain. With the exception of hippocampus, cerebellum and bulbus olfactorius closely matching distribution patterns of α4 and δ subunit mRNAs and immunoreactivities were obtained. An overlapping distribution was also observed for α2- and β3-subunits. The α3-subunit had a unique distribution especially concerning the hippocampus and thalamus, which did not match that of any other subunit.

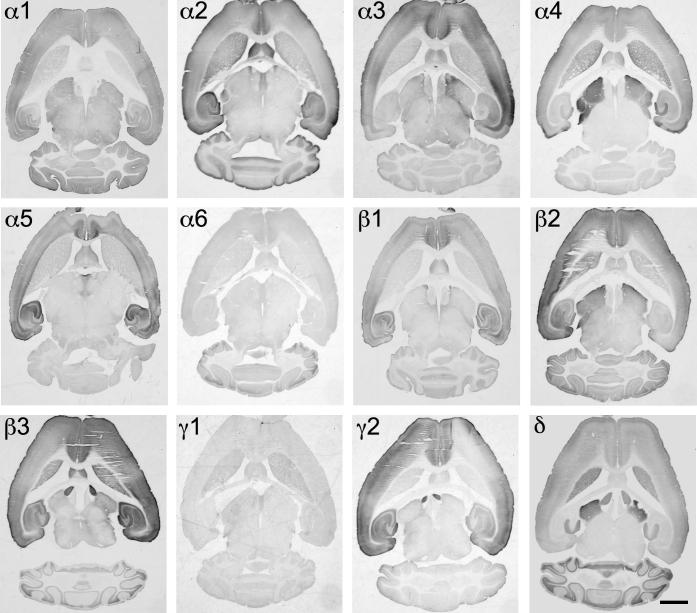

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in horizontal sections of the mouse brain at the level of Bregma −3.60 to −4.00 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Note the widespread distribution of α1-, β2- and γ2-subunit mRNAs in this horizontal section of the brain. α4- and δ-subunit mRNAs are co-localized in the striatum, thalamus and bulbus olfactorius, but not in the cerebellum. Expression of α6-subunit mRNA was restricted to the cerebellum. Scale bar = 2 mm.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in horizontal sections of the mouse brain at the level of Bregma −3.60 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). In general, the localization of the protein resembled that of mRNA. Note the widespread distribution of α1- and β2-subunits. In contrast to mRNA labeling the immunoreactiv for γ2 was less intense in the striatal and thalamic area. α4- and δ-subunit proteins are co-localized in the striatum, thalamus and bulbus olfactorius, but not in the cerebellum. The arrow indicates the immunoreactivity of the α6-subunit in the cerebellum. Scale bar = 2 mm.

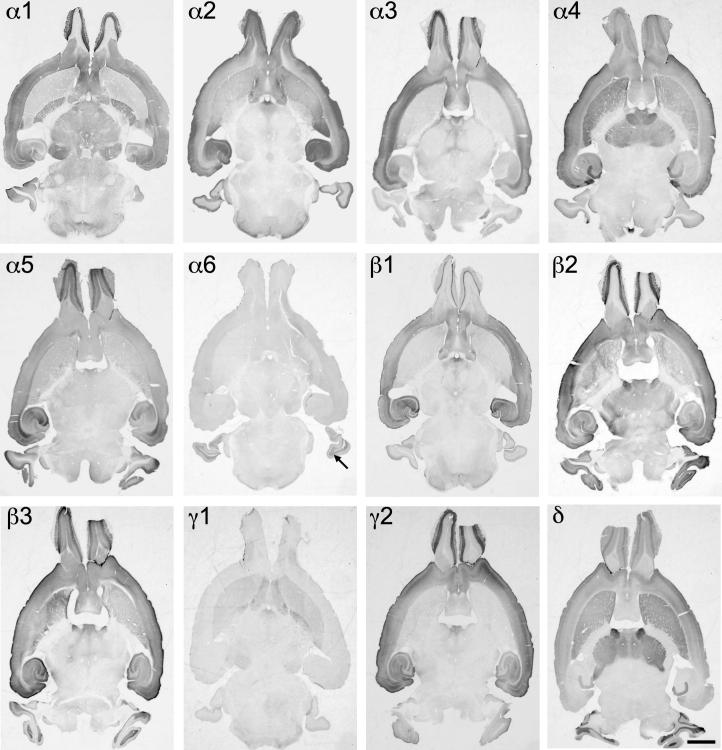

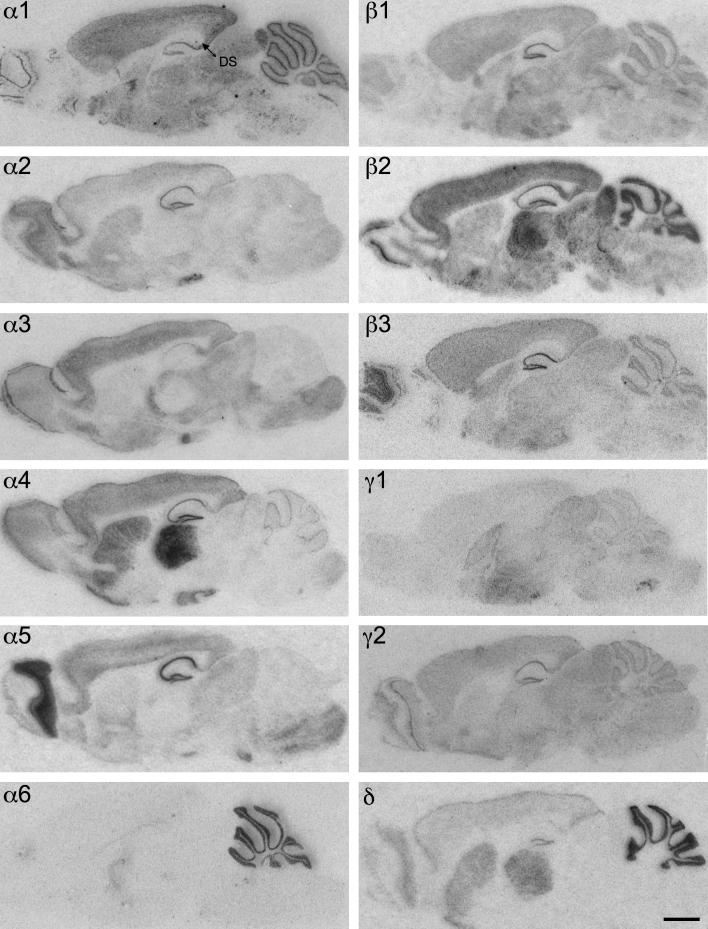

Fig. 3.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in horizontal sections of the mouse brain at the level of Bregma −2.56 to −2.36 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Note the widespread distribution of α1, β2 and γ2 mRNAs in this horizontal section of the brain. α4 and δ mRNAs are co-localized in the striatum, thalamus and bulbus olfactorius, but not in the cerebellum. Expression of α6 mRNA was restricted to the cerebellum. In the hippocampus strong labeling occurs especially for α2, α5 and β2. Scale bar = 2 mm.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in horizontal sections of the mouse brain at the level of Bregma −2.56 to −2.36 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). In general, the localization of the protein resembled that of mRNA. Note the widespread distribution of α1- and β2-subunits. In contrast to mRNA labeling the immunoreactiv for γ2 was less intense in the striatal and thalamic area. α4 and δ proteins are co-localized in the striatum and thalamus, but not in the cerebellum and CA1–CA3 of the hippocampus. The immunoreactivity of the α6-subunit is restricted to the cerebellum. Scale bar = 2 mm.

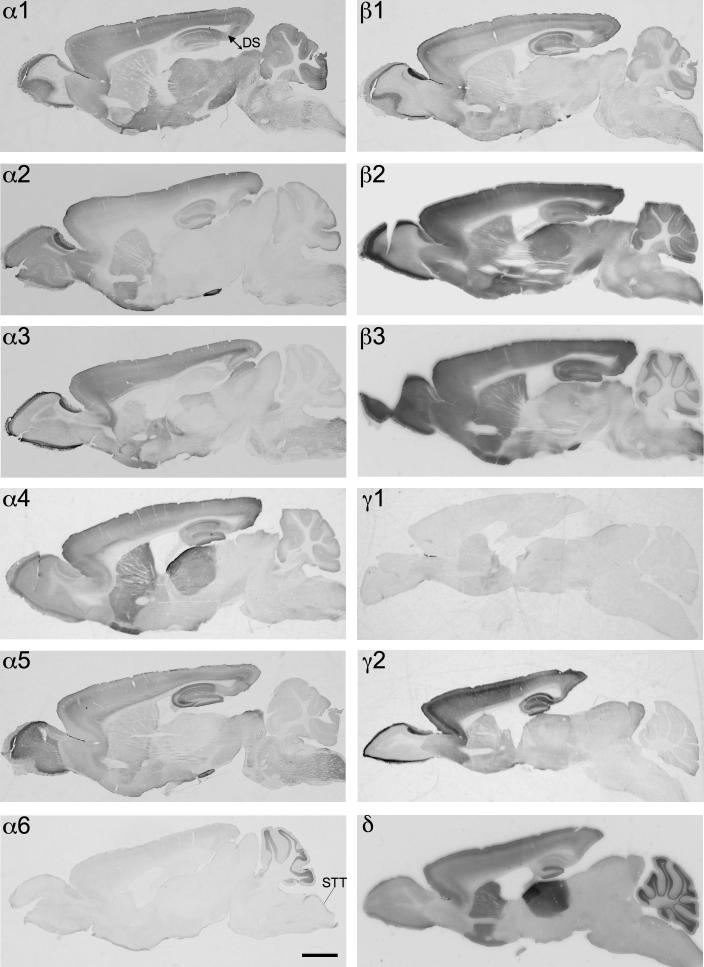

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in sagittal sections of the mouse brain approximately at the lateral level 1.20 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Note the widespread distribution of α1-, β2- and γ2-subunit mRNAs in this sagittal section of the brain. α4- and δ-subunit mRNAs are co-localized in the striatum and thalamus but not in the cerebellum. Expression of α6 mRNA was restricted to the cerebellum. Note the strong label of α1-and β2-subunit in the dorsal subiculum (DS). Scale bar = 2 mm.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in sagittal sections of the mouse brain approximately at the lateral level 1.20 mm (according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). In general, the localization of the protein resembled that of mRNA. Note the widespread distribution of α1- and β2-subunits. In contrast to mRNA labeling the immunoreactiv for γ2 was less intense in the striatal and thalamic area. α4 and δ proteins are co-localized in the striatum and thalamus, but not in the cerebellum and CA1–CA3 of the hippocampus. The immunoreactivity of the α6-subunit is restricted to the cerebellum and the spinal trigeminal tract (STT). Note the strong label of α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits in the dorsal subiculum (DS). Scale bar = 2 mm.

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the cortical areas of the mouse

In the neocortex no evidence for the expression of the α6-subunit was found. The labeling for the γ1-subunit was very faint especially in the ISH. All other subunits were widely distributed throughout the cortical areas including piriform cortex and endopiriform nucleus, entorhinal and perirhinal cortices (summarized in Table 3). In general a good correspondence between the ISH and immunohistochemical signal was obvious. With the exception of the subunits α6, γ1, and δ a high expression of mRNA and protein was found in the piriform, entorhinal and perirhinal cortices.

Table 3.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse cerebral cortex

| Cerebral cortex | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Layer 1 | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | ++ | – | – |

| Layer 2 | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| Layer 3 | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | ||

| Layer4 | +++ | +++ | +(+) | + | (+) | (+) | ++ | ++ | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| Layer 5 | + | + | + | + | ++(+) | ++ | + | + | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| Layer 6 | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++(+) | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | – | – |

| Piriform cortex | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| Endopiriform nuc | + | +++ | + | + | +++ | +++ | (+) | + | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| Entorhinal cortex | ++(+) | +++ | ++ | +(+) | ++ | +++ | +(+) | +++ | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| Perirhinal cortex | ++ | +++ | ++ | +(+) | ++ | +++ | +(+) | +++ | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Layer 1 | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | (+) | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Layer 2 | +(+) | + | ++ | + | +(+) | + | (+) | + | +(+) | + | ++ | ++ |

| Layer 3 | +(+) | + | ++ | + | +(+) | + | (+) | + | +(+) | + | ++ | ++ |

| Layer4 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | (+) | + | ++(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Layer 5 | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | (+) | (+) | +(+) | + | + | + |

| Layer 6 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | (+) | + | +(+) | + | +(+) | + |

| Piriform cortex | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | (+) | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Endopiriform nuc | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | + | +(+) | ++ | (+) | + |

| Entorhinal cortex | +++ | +++ | +(+) | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | + | ++ | +++ | (+) | + |

| Perirhinal cortex | +++ | +++ | +(+) | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | + | ++ | +++ | (+) | + |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling.

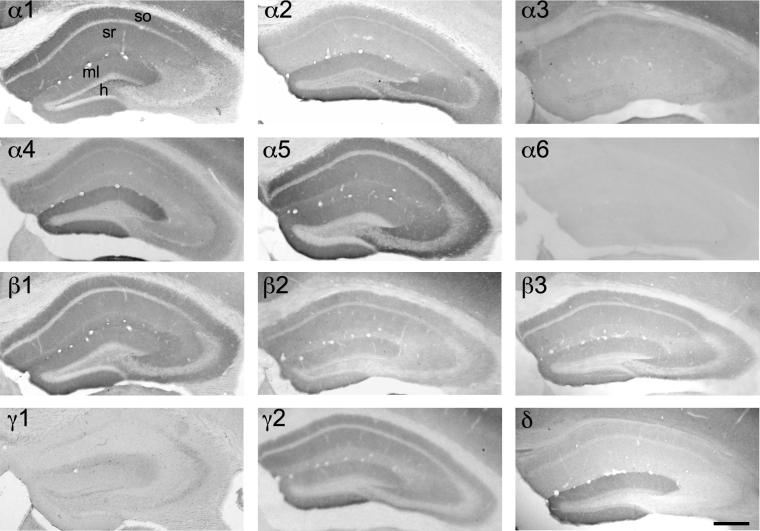

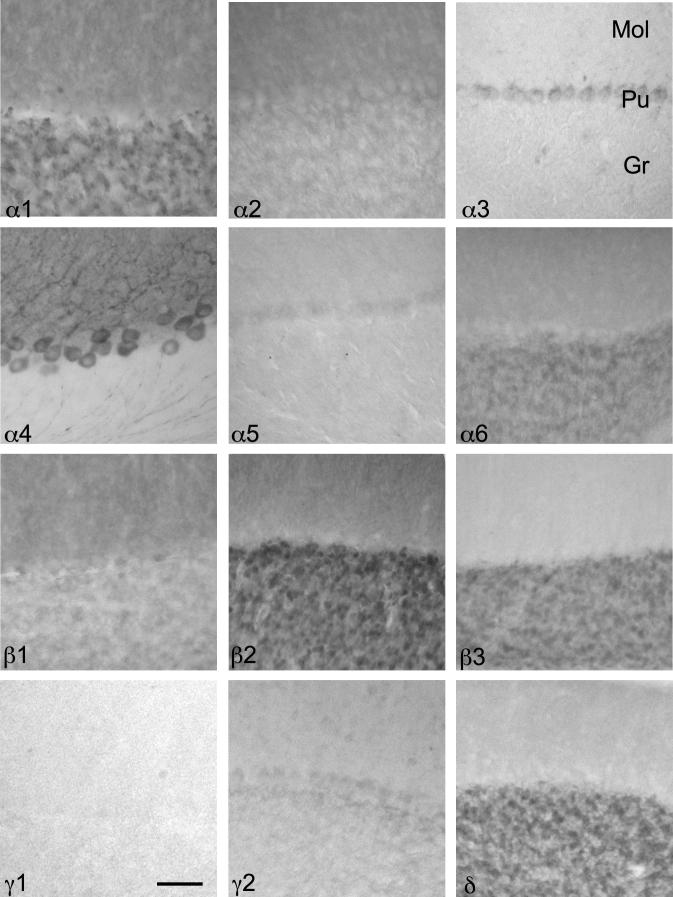

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse hippocampal formation

In the hippocampus a clear dissociation between the location of mRNAs and proteins was observed. ISH signals were restricted to the pyramidal cell layer of cornu ammonis (CA) CA1 to CA3, the granule cell layer and the hilus of the dentate gyrus. Immunohistochemical labeling, however, was predominantly found in the respective dendritic fields, the strata oriens and radiatum of CA1 to CA3 and in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (see Figs. 7–9; Table 4). Within the hippocampal formation ISH signals and labeling intensity of the immunoreactive proteins appeared to be different for individual subunits.

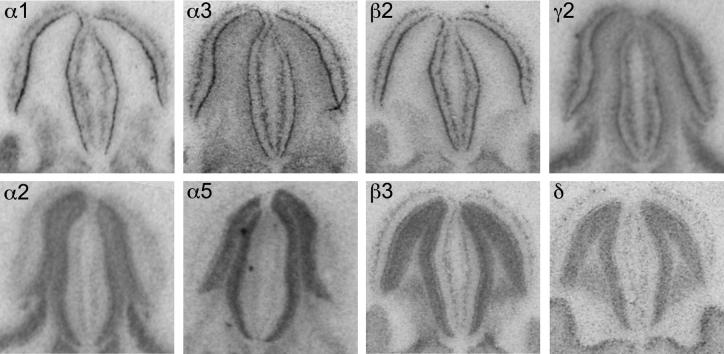

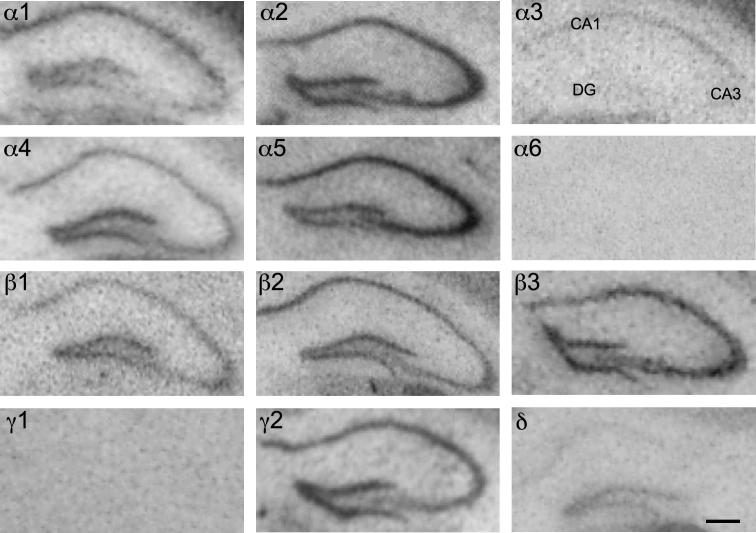

Fig. 7.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the dorsal hippocampus (coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.82 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). In situ hybridization signals were restricted to the pyramidal cell layer of cornu ammonis CA1 to CA3, the granule cell layer and the hilus of dentate gyrus. Note the strong signals of α2-, α5- and β3-subunits throughout the hippocampus. α1-subunit mRNA labeling was weak in the CA3 area in comparison to a strong label in CA1 and dentate gyrus. α3-subunit mRNA was weakly expressed and restricted to CA1, whereas δ-subunit mRNA was almost exclusively restricted to the dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 300 μm. DG = dentate gyrus.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the dorsal hippocampus (coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.82 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Immunohistochemical labeling was predominantly found in the respective dendritic fields, the strata oriens (so) and radiatum (sr) of CA1 to CA3 and in the molecular layer (ml) of the dentate gyrus. Note the faint labeling of the α3-subunit restricted to the CA1 region. A strong expression of α2- and α5-subunits occurred throughout the hippocampus proper with highest intensity in the CA3 area. Note the co-distribution of α4- and δ-subunit protein in the dentate gyrus, but not in the CA1–CA3 region. Scale bar = 300 μm. h = hilus.

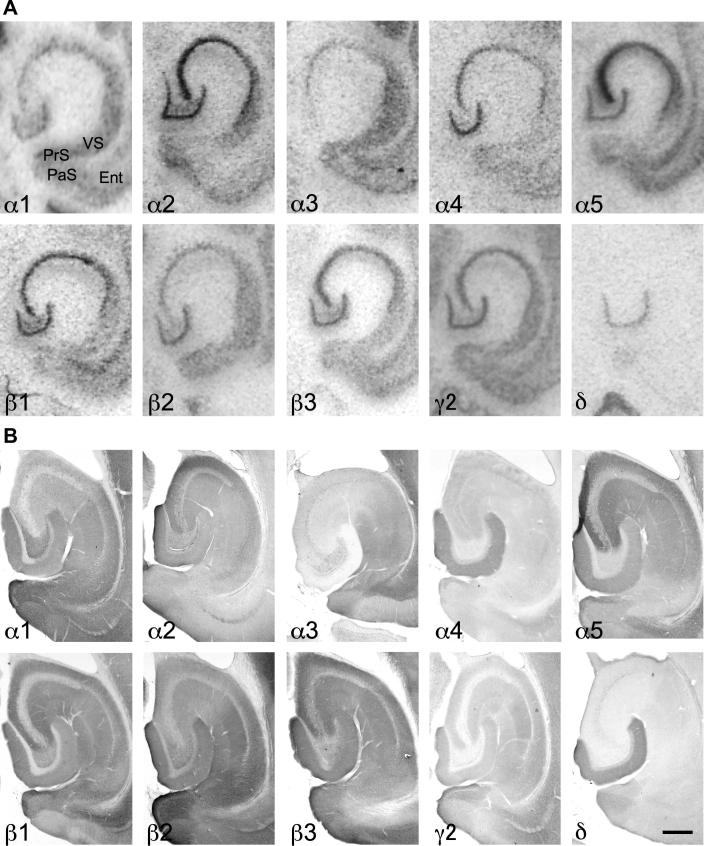

Fig. 9.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor (A) subunit mRNAs and (B) immunoreactivities (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ2 and δ) in the ventral hippocampus, ventral subiculum (VS), parasubiculum (PaS) and presubiculum (PrS) and entorhinal cortex (Ent). Note the strong labeling of the α3-subunit mRNA and protein in VS, PaS and PrS, in contrast to the weak labeling in CA1 and missing labeling in the dentate gyrus. The α5-unit is strongly expressed in CA1–CA3, but faint in VS, PaS and PrS. Note the exclusive expression of the δ-subunit in the dentate gyrus (horizontal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −3.28 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Scale bar = 300 μm.

Table 4.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse hippocampus

| Hippocampus | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Dentate gyrus | ++(+) | ++ | +++ | +++ | – | – | +++ | +++ | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| Hilus | + | ++(+) | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CA1 | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | +(+) | + | ++ | ++(+) | – | – |

| CA2 | ++ | +(+) | +++ | ++ | + | (+) | +(+) | + | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| CA3 | + | + | +++ | +++ | – | (+) | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| Ventral subiculum | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | – | – |

| Dorsal subiculum | +++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | +++ | + | + | ++ | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| Parasubiculum | ++(+) | +++ | + | + | +(+) | ++ | +(+) | +++ | + | ++ | – | – |

| Presubiculum | ++(+) | +++ | ++(+) | + | +(+) | ++ | +(+) | +++ | + | ++ | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Dentate gyrus | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | – | – | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++(+) |

| Hilus | + | + | + | +(+) | + | – | – | – | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| CA1 | +++ | +++ | ++ | +(+) | +++ | ++(+) | – | – | ++ | ++ | (+) | (+) |

| CA2 | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | – | – | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| CA3 | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | – | – | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Ventral subiculum | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | – | – | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| Dorsal subiculum | + | + | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | – | – | + | ++ | – | – |

| Parasubiculum | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | – | +++ | ++(+) | + | + |

| Presubiculum | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | – | ++(+) | ++(+) | + | + |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling.

The α1 mRNA and protein were both abundantly found in the dentate gyrus and hilus, CA1 region as well as in the dorsal (Figs. 5 and 6) and ventral subiculum (Fig. 9), whereas the expression in the CA3 area was considerably weaker.

The α2-subunit was present in all subfields of the hippocampus including the dentate hilus with the highest concentrations in the dentate gyrus and area CA3, both at the mRNA and protein level. The concentrations in the ventral subiculum were much lower than in other parts of the hippocampal formation and almost no signals were present in the dorsal subiculum.

Similar to that seen in the rat brain the α3-subunit was beside α6- and γ1-subunits the least expressed subunit in the hippocampus. The mRNA signal was restricted to CA1, where a very faint immunohistochemical labeling was found. In contrast, strong labeling of both ISH and IHC was found in the ventral (Fig. 9) and dorsal subiculum and moderate labeling in the hilus of the dentate gyrus.

For the α4-subunit strong labeling was observed in the granule cell layer and molecular layer of the DG by ISH and IHC, respectively. In CA1 to CA3 the concentration was lower and no signal was detected in the hilus. In the ventral and dorsal subiculum only a faint signal was present.

The α5-subunit displayed a distribution within the hippocampus, and ventral and dorsal subiculum similar to the α2-subunit with the strongest signals of both ISH and IHC in the CA3 area and the dentate gyrus. Almost no labeling was observed in the ventral and dorsal subiculum and dentate hilus.

The β-subunit mRNAs and proteins were present throughout the hippocampus including subiculum. Labeling for the β2-subunit very much resembled that of the α1-subunit.

For the γ1-subunit no ISH signal, and similar to that seen in the rat, only a very faint and diffuse immunoreactivity was detected throughout the hippocampus. The γ2-subunit provided mRNA signals and immunohistochemical labeling with equal intensity throughout the hippocampus.

The distribution of the δ-subunit in the hippocampus and subiculum was almost exclusively restricted to the dentata gyrus with only a very faint signal in the CA1 area. No labeling was found in the CA3 area, in the ventral and dorsal subiculum and in the hilus of the dentate gyrus.

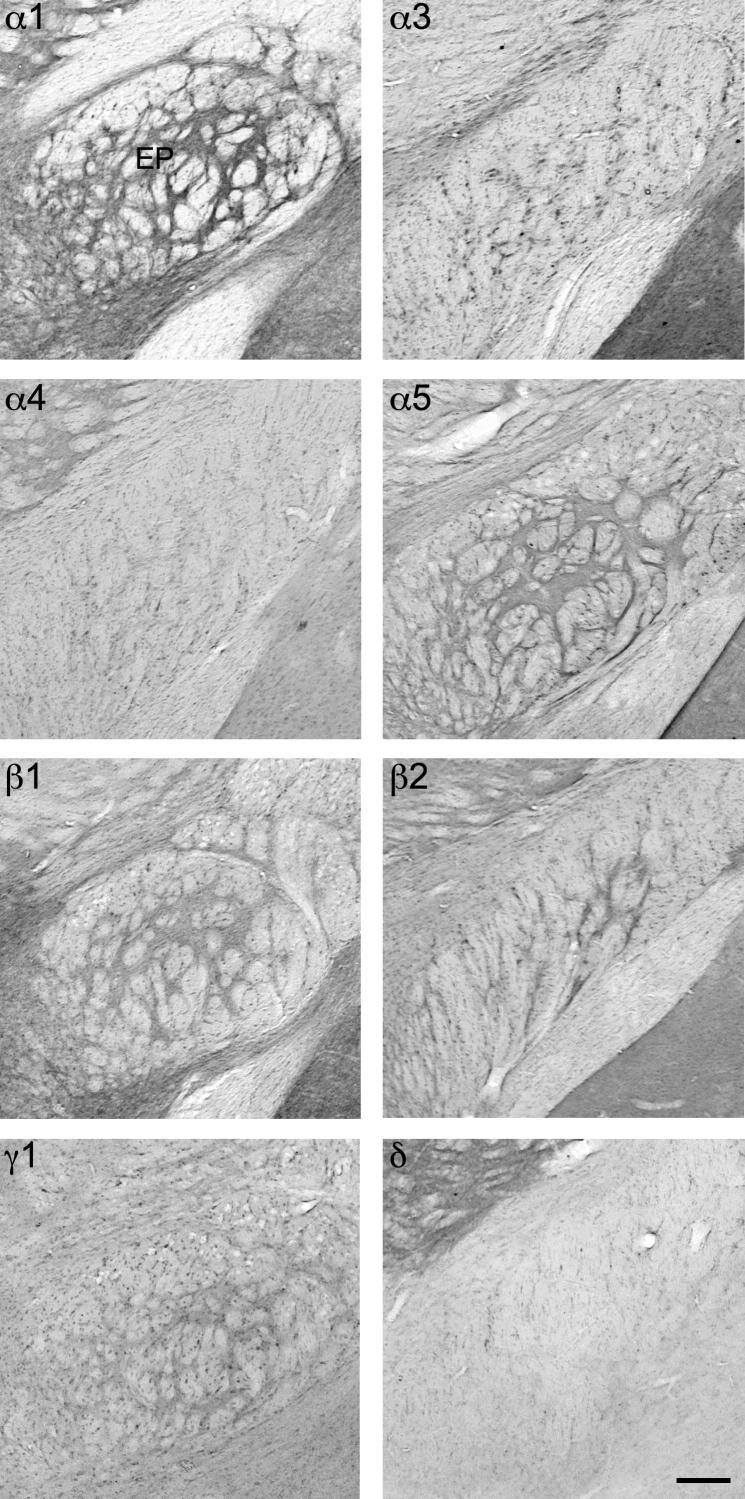

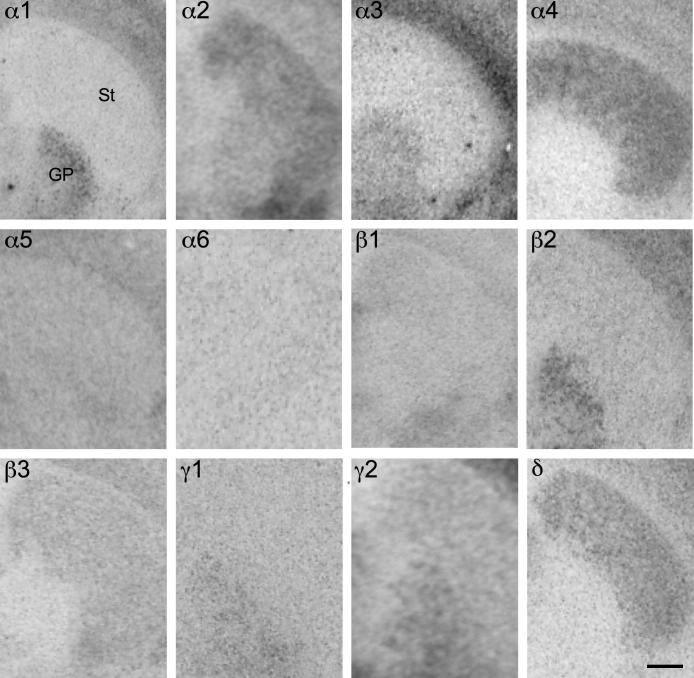

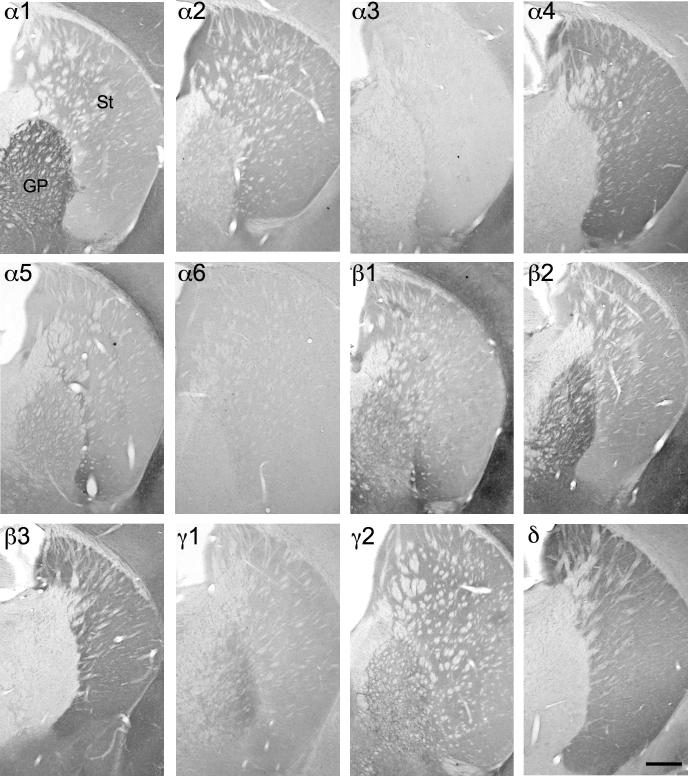

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse striatal and pallidal areas

Similar to that seen in the rat a frequently complementary distribution of individual subunits within different nuclei of the basal ganglia was detected. The subunits α2, α4, β3 and δ were considerably more concentrated in the striatum and the associated brain areas of nucleus accumbens core and shell than in the globus pallidus and entopeduncular nucleus (Fig. 12) both on the level of mRNA and protein. In contrast, the globus pallidus and its related brain nuclei, entopeduncular nucleus and ventral pallidum displayed considerably stronger ISH signal and immunoreactivity for α1-, β2-, γ1- and γ2-subunits than the striatum and nucleus accumbens (Figs. 10–12; Table 5).

Fig. 12.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1, α3, α4, α5, β1, β2, γ1 and δ) in the entopeduncular nucleus (EP; coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.22 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). A strong immunoreactivity in EP was observed for α1-, α5, β1-, β2- and γ1-subunis. Scale bar = 150 μm.

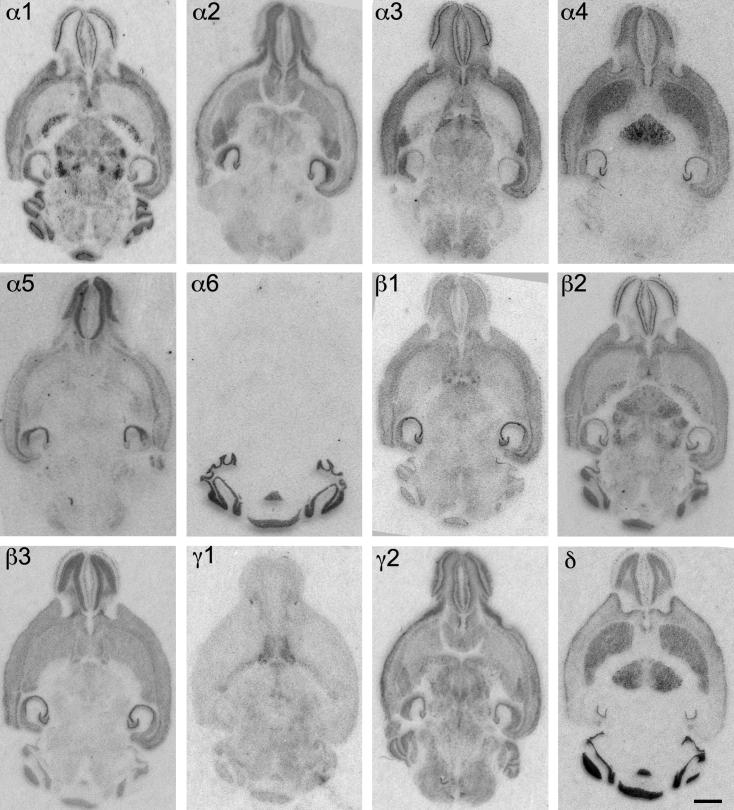

Fig. 10.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the striatum (St) and globus pallidus (GP; coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −0.34 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). The subunits α2, α4, β3 and δ were considerably more concentrated in St than in GP, whereas in situ hybridization signal for α1-, β2-, γ1- and γ2-subunits are much stronger in GP than in St. Scale bar = 400 μm.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the striatum (St) and globus pallidus (GP; coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −0.34 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). The distribution of the subunits protein very well agrees with that of the mRNA. Scale bar = 400 μm.

Table 5.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse basal ganglia and septal and basal forebrain

| Basal ganglia | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Caudate putamen | (+) | + | ++ | ++ | – | (+) | +++ | +++ | – | + | – | – |

| N. accumbens core | (+) | (+) | +++ | ++ | – | (+) | ++ | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| N. accumbens shell | (+) | (+) | +++ | ++ | + | (+) | ++ | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| Globus pallidus | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | (+) | – | – | – | (+) | – | – |

| Ventral pallidum | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | (+) | – | – | (+) | + | – | – |

| Entopeduncular nuc | ++ | ++ | – | (+) | – | (+) | – | (+) | – | + | – | – |

| Subthalamicus | +++ | ++(+) | + | + | ++(+) | ++ | – | (+) | – | + | – | – |

| Substantia nigra ret | +++ | +++ | – | + | + | + | (+) | (+) | – | (+) | – | – |

| Substantia nigra comp | ++ | + | – | + | + | + | – | (+) | – | (+) | – | – |

| Septal and basal forebrain | ||||||||||||

| Lateral septum | + | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | + | +(+) | – | – |

| Medial septum | ++(+) | ++ | + | – | ++ | – | (+) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bed nuc stria terminalis | – | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | + | + | + | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Caudate putamen | + | (+) | + | + | ++ | ++(+) | (+) | + | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| N. accumbens core | ++ | (+) | +(+) | + | ++ | +(+) | (+) | (+) | + | – | +++ | ++ |

| N. accumbens shell | + | (+) | +(+) | + | ++ | +(+) | (+) | (+) | + | – | +++ | ++ |

| Globus pallidus | (+) | + | +++ | ++ | – | – | ++ | +++ | +(+) | + | – | – |

| Ventral pallidum | – | (+) | +++ | ++ | – | – | + | +++ | ++ | + | – | – |

| Entopeduncular nuc | – | +(+) | ++ | ++ | – | – | – | + | – | (+) | – | – |

| Subthalamicus | (+) | +(+) | ++ | +++ | – | + | – | – | ++ | +(+) | – | + |

| Substantia nigra ret | + | (+) | +++ | + | – | – | + | (+) | +(+) | (+) | – | – |

| Substantia nigra comp | + | (+) | +++ | +++ | – | – | + | (+) | +(+) | (+) | – | – |

| Septal and basal forebrain | ||||||||||||

| Lateral septum | +++ | +++ | +(+) | ++(+) | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +(+) | + | – | – |

| Medial septum | + | – | +++ | ++ | – | – | (+) | – | +++ | (+) | – | – |

| Bed nuc stria terminalis | +++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | – | – |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling; nuc = nucleus; ret = reticularis; comp = compacta.

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse diencephalon (thalamus, hypothalamus and epithalamus)

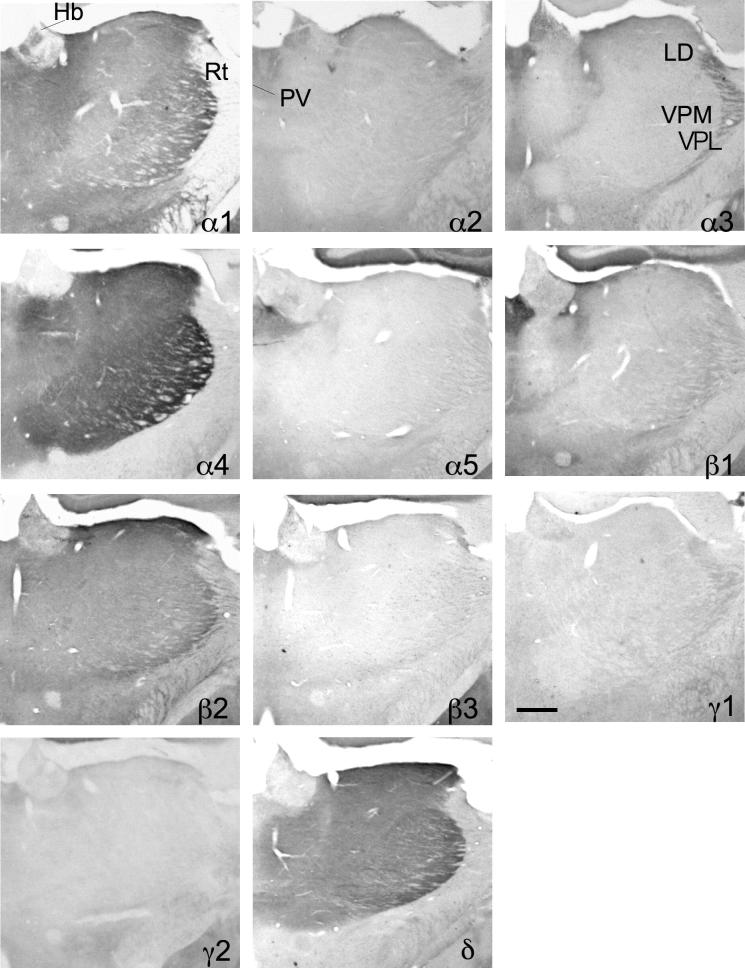

In Fig. 13 and Table 6 the distribution and labeling intensities of the 12 subunits investigated in the thalamic nuclei are summarized. Most thalamic nuclei were extremely rich in mRNA (Table 6) and protein of α1-, α4-, β2- and δ-subunits (Fig. 13). All other subunits were less abundant. No signals for the α6-subunit were detectable. Interestingly, the paraventricular thalamic nucleus was the only thalamic area containing mRNA and immunoreactivity of all subunits except the α6-subunit. The reticular thalamic nucleus exhibited a distinct subunit repertoire. The highest labeling both of ISH and IHC was achieved for the α3-subunit, associated with a much weaker labeling for the β1- and γ1-subunits. In contrast to most other thalamic nuclei the reticular nucleus was almost devoid of labeling for α1, α4, β2 and δ.

Fig. 13.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the thalamus (coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.58 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Most thalamic nuclei are extremely rich in protein of α1-, α4-, β2- and δ-subunits. The paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PV) is the only thalamic area containing immunoreactivity of all subunits except the α6-subunit. The reticular thalamic nucleus (Rt) is characterized by a high expression of the α3-subunit. Scale bar = 500 μm. Hb = habenula, LD = laterodorsal thalamic nucleus, PV = paraventricular thalamic nucleus, Rt = reticular thalamic nucleus, VPL = ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus, VPM = ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus.

Table 6.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse thalamus

| Thalamus | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Anteroventral nuc | ++ | +++ | – | + | + | – | +++ | +++ | – | + | – | – |

| Anterodorsal nuc | +++ | +++ | – | – | + | + | +++ | +++ | – | + | – | – |

| Anteromedial nuc | ++ | +++ | – | – | + | – | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| Parafascicular thal nuc | ++ | ++ | + | + | +++ | ++ | + | – | – | – | ||

| Post. Thalam. nuclei | ++(+) | +++ | – | – | – | – | +++ | ++ | – | – | – | – |

| Ventromedial area | ++(+) | ++ | – | – | – | – | +++ | ++ | – | ++ | – | – |

| Ventrolateral nuc | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | – | +++ | ++ | – | – | – | – |

| Mediodorsal nuc | +++ | ++ | – | – | ++ | – | +++ | +++ | – | + | – | – |

| Laterodorsal nuc | +++ | +++ | + | +(+) | + | +(+) | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| Reticular nuc | – | – | – | + | ++(+) | ++(+) | – | – | – | (+) | – | – |

| Paraventricular thal nuc | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++(+) | +(+) | +(+) | – | – |

| Central medial thal nuc | + | +++ | + | – | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | – | – | – | – |

| Centrolateral thal nuc | + | ++ | – | – | + | + | +++ | ++ | – | – | – | – |

| Reuniens thal nuc | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | +(+) | +++ | ++(+) | (+) | – | – | – |

| Dorsal geniculate nuc | ++ | +++ | + | + | (+) | + | +++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| Perigeniculate nuc | ++ | +++ | +(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+) | (+) | (+) | + | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Anteroventral nuc | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | – | (+) | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Anterodorsal nuc | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | (+) | + | – | + | +(+) | – | +++ | +++ |

| Anteromedial nuc | ++ | – | +++ | +++ | (+) | + | – | (+) | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Parafascicular thal nuc | +++ | – | +++ | +(+) | – | – | – | – | +(+) | – | + | ++ |

| Post. Thalam. nuclei | ++ | – | +++ | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Ventromedial area | + | – | +++ | + | – | + | – | (+) | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Ventrolateral nuc | + | – | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | (+) | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Mediodorsal nuc | +++ | – | +++ | + | – | + | (+) | (+) | ++ | – | +++ | +++ |

| Laterodorsal nuc | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | – | + | – | +(+) | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| Reticular nuc | + | + | – | (+) | – | (+) | – | + | + | – | – | – |

| Paraventricular thal nuc | +++ | +++ | + | +(+) | +(+) | + | + | + | ++(+) | + | +(+) | + |

| Central medial thal nuc | ++(+) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | – | +++ | + |

| Centrolateral thal nuc | +(+) | + | + | + | – | (+) | – | – | + | – | +++ | + |

| Reuniens thal nuc | +(+) | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | +(+) |

| Dorsal geniculate nuc | + | + | ++(+) | +++ | (+) | + | – | – | +(+) | + | +++ | +++ |

| Perigeniculate nuc | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+) | + | – | – | +(+) | +(+) | (+) | (+) |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling; nuc = nucleus; thal = thalamic.

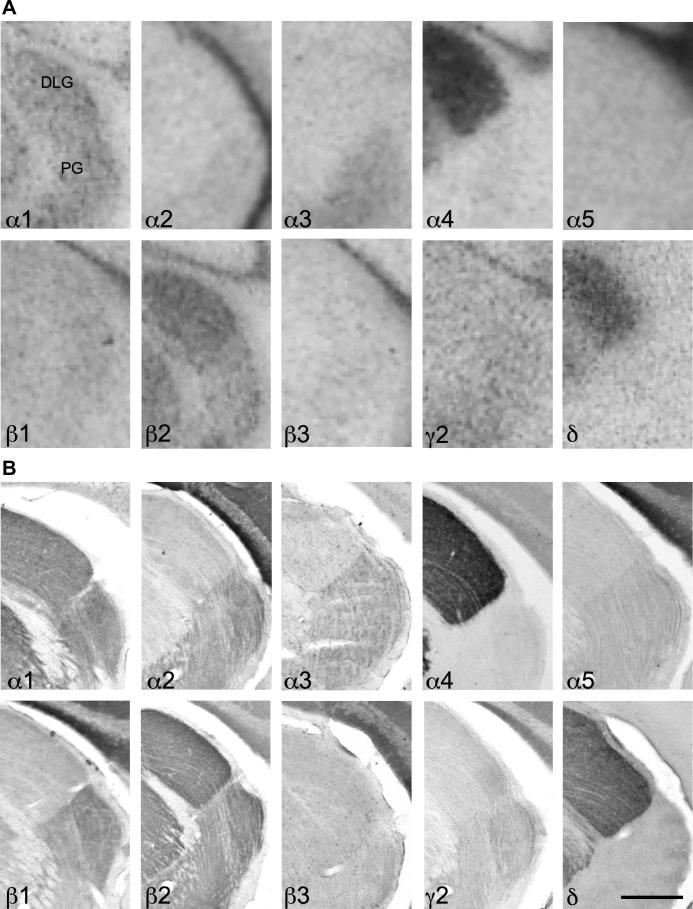

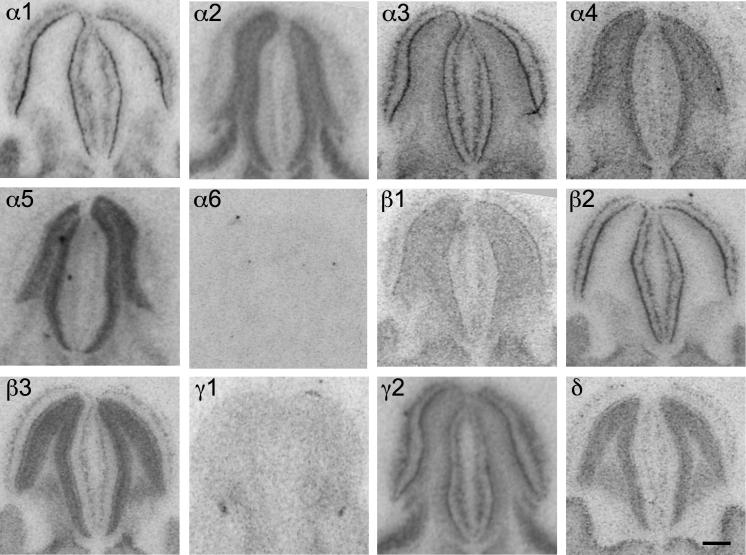

Comparable to the rat brain, a remarkable segregation of GABAA receptor subunit distribution was observed between the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus and the pregeniculate nucleus (Fig. 14; Table 6). Both geniculate nuclei were strongly labeled for α1- and β2-subunits both at the mRNA and protein level with the highest intensity in the dorsal part. Labeling for α4- and δ-subunits was extremely strong in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus with only a faint intensity in the pregeniculate area. In contrast, labeling for subunits α2, α3, β1, β3 and γ2 was much less intense in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus and more concentrated in the pregeniculate nucleus.

Fig. 14.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor (A) subunit mRNAs and (B) immunoreactivities (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ2 and δ) in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (DLG) and pregeniculate nucleus (PG; coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma -2.70 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). The distribution of the subunits protein very well agrees with that of the mRNA. Note the clear co-distribution of α4- and δ-subunits. Only α1- and β2-subunits were detected in both nuclei. Scale bar = 400 μm.

In the medial habenula the most prominent subunit was the α2-subunit both at the mRNA and protein level associated with moderate ISH signal but missing immunoreactivity for the β1- and γ2-subunits. The lateral habenula was characterized by the presence of α1-, α2-, α3-, β1- and γ1-subunits (Table 7).

Table 7.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse hypothalamus and epithalamus

| Hypothalamus | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Preoptic area | +(+) | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| Lateral hypothalamic area | +(+) | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++(+) | + | + | + | ++ | – | – |

| Anterior hypothalamus | +(+) | +(+) | +++ | + | ++(+) | + | + | + | + | +(+) | – | – |

| Posterior hypothalamus | ++(+) | + | + | + | ++(+) | + | – | – | + | + | – | – |

| Paraventricular nuc | + | + | +++ | +(+) | + | + | – | – | (+) | + | – | – |

| Arcuate nuc | + | – | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | – | (+) | ++ | +(+) | – | – |

| Ventromedial nuc | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Dorsomedial nuc | + | ++ | + | + | ++(+) | + | – | – | + | +(+) | – | – |

| Mamillary nuclei | + | +++ | +(+) | ? | + | + | (+) | – | +(+) | +(+) | – | – |

| Epithalamus | ||||||||||||

| Medial habenular nuc | – | – | +++ | + | – | (+) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lateral habenular nuc | + | + | + | (+) | + | (+) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Preoptic area | +++ | +++ | ++ | (+) | ++(+) | + | ++ | +(+) | +++ | (+) | + | – |

| Lateral hypothalamic area | +(+) | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | – | – | |

| Anterior hypothalamus | +++ | +++ | +(+) | ++ | ++ | ++(+) | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Posterior hypothalamus | +(+) | + | +(+) | (+) | + | (+) | – | +++ | (+) | – | – | |

| Paraventricular nuc | +(+) | +(+) | + | (+) | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | – | – |

| Arcuate nuc | + | + | – | + | – | +(+) | ++ | + | + | (+) | – | – |

| Ventromedial nuc | ++ | (+) | +(+) | (+) | + | +(+) | + | + | + | – | – | |

| Dorsomedial nuc | +++ | +++ | +(+) | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | +(+) | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| Mamillary nuclei | +(+) | + | + | (+) | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | – | – |

| Epithalamus | ||||||||||||

| Medial habenular nuc | + | – | – | – | (+) | – | – | (+) | +(+) | – | – | – |

| Lateral habenular nuc | + | + | – | (+) | (+) | – | +(+) | + | + | – | – | (+) |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling; nuc = nucleus.

The distribution and labeling intensities of the 12 subunits investigated in the hypothalamic nuclei are summarized in Table 7. Besides the missing expression of the α6-subunit labeling for the α4- and δ-subunits was hardly detectable both on the mRNA and protein level. All other subunits were distributed all over the hypothalamus. Comparable to the rat (Pirker et al., 2000) the subunit α1, β2 and γ2-antibodies labeled most parts of the hypothalamus associated with a corresponding intensity of ISH. The β1-subunit was highly expressed in most parts of the hypothalamus both at the mRNA as well as the protein level, a finding contrasting with ISH data (Wisden et al., 1992) but well agreeing with the protein expression of the rat hypothalamus (Pirker et al., 2000). Remarkably, in contrast to most other brain areas, the ISH signal for the γ1-subunit was considerably high throughout the hypothalamus similar to the rat hypothalamus (Wisden et al., 1992).

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse amygdala

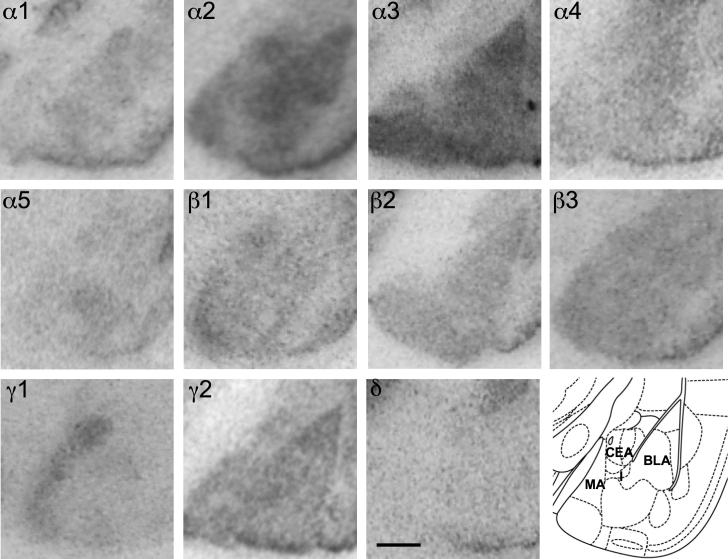

Male C57BL/6NCrl mice revealed a similar distribution of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the amygdaloid nuclei as previously described for CD1 and C57BL/6J mice (Heldt and Ressler, 2007a,b; Tasan et al., 2011). As shown in Fig. 15 and Table 8, expression for GABAA receptor subunits α1, α2, α3, β3 and γ2 was high. Subunits α1 and β2 mRNA were preferentially detected in the lateral and basolateral amygdala. Low expression was observed for subunits α4, α5 and δ. Subunit γ1 mRNA was restricted to the central and medial amygdaloid nucleus (Fig. 15). Also GABAA receptor protein was rather equally distributed in many instances. Subunits α1-, β2- and γ2-immunoreactivities, however, were only weakly expressed in the central nucleus, in contrast to the comparably high staining for subunits α2, α3, α4, β1 and γ1 protein in this nucleus. Subunits α3-, α4- and δ-immunoreactivities were strongly expressed in the intercalated cell masses, whereas these cell groups appeared to be devoid of α1, β1 and γ2 (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the amygdala (coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.58 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Scale bar = 500 μm. In the bottom right a schematic drawing adapted from Franklin and Paxinos, 2007 is included. CEA = central amygdala, BLA = basolateral amygdala, I = intercalated nucleus. Note preferential presence of the subunits α1 and β2 mRNA in the lateral and basolateral amygdala. Low expression is visible for subunit α4, α5 and δ. Subunit γ1 mRNA is restricted to the central and medial amygdaloid nucleus.

Table 8.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse amygdala

| Amygdala | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Central nuc | – | – | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | + | +++ | – | – |

| Basomedial nuc | + | ++(+) | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | +(+) | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| Basolateral nuc | ++ | +(+) | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | – | – |

| Lateral nuc | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | +(+) | + | – | – |

| Intercalate nuc | – | +(+) | +++ | ++(+) | ++ | |||||||

| Medial nuc | +(+) | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +(+) | ++ | + | ++ | – | – |

| Anterior cortical nuc | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| Posterior cortical nuc | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | +(+) | ++ | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Central nuc | +++ | +++ | – | (+) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | – | + |

| Basomedial nuc | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Basolateral nuc | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++(+) | (+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Lateral nuc | ++ | ++(+) | ++ | +++ | + | ++(+) | (+) | + | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| Intercalate nuc | (+) | + | +++ | (+) | + | +(+) | ||||||

| Medial nuc | +++ | ++(+) | +(+) | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | +(+) | +(+) | – | (+) |

| Anterior cortical nuc | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++(+) | ++ | ++(+) | + | + | ++ | +(+) | + | + |

| Posterior cortical nuc | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++(+) | +++ | ++(+) | + | + | ++ | +(+) | + | + |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling; nuc = nucleus.

Fig. 16.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the amygdala (coronal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −1.58 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Scale bar = 500 μm. In the bottom right a schematic drawing adapted from Franklin and Paxinos, 2007 is included. CEA = central amygdala, BLA = basolateral amygdala, I = intercalated nucleus, MA = medial amygdaloid nucleus. The distribution of the subunits protein very well agrees with that of the mRNA with, e.g. no or only faint immunoreactivity for the subunits α1, β2 and γ2, but a relatively strong labeling for subunit γ1 in the central amygdala.

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse cerebellum

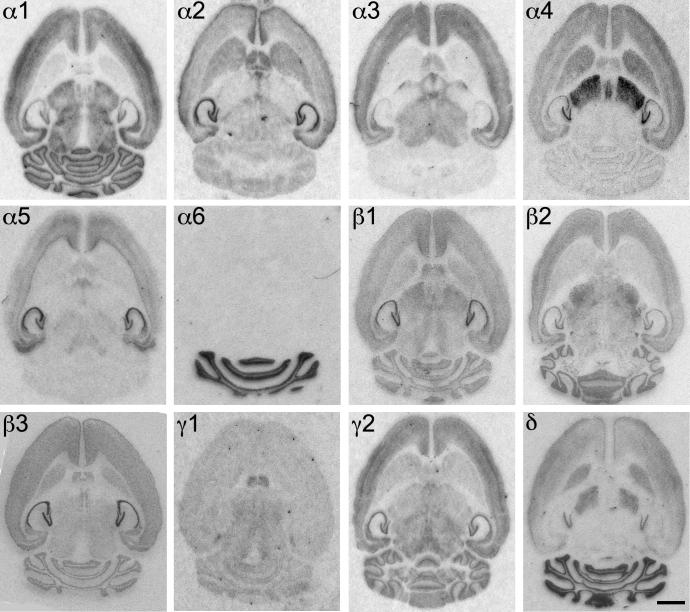

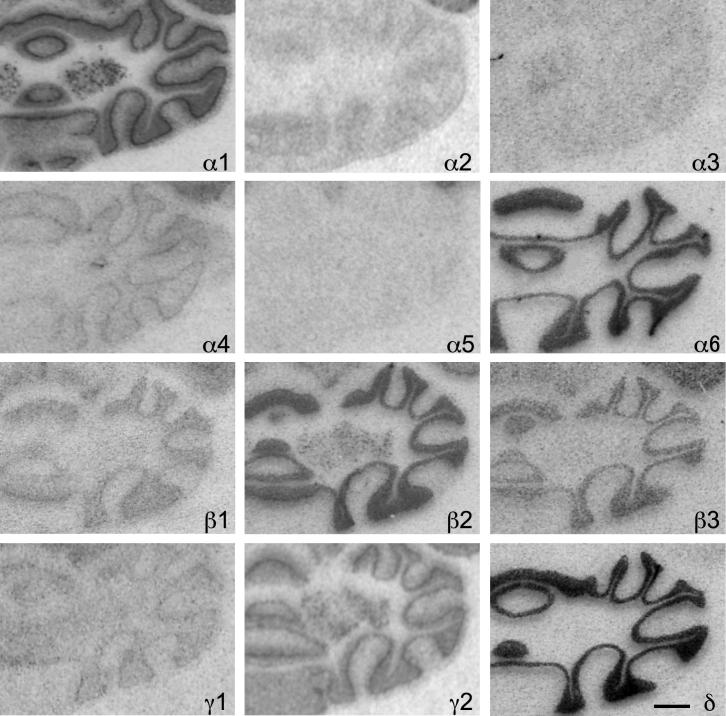

The cerebellum was characterized by high concentrations and a wide heterogeneity of most GABAA receptor subunits as demonstrated by ISH and IHC (Figs. 17 and 18; Table 9). In agreement with the subunit distribution in rat cerebellum the granule cell layer of the mouse cerebellum displayed high concentrations of the α1-, α6-, β2-, β3-, γ2-, and δ-subunits concerning both mRNA and protein. In contrast, ISH signals and immunolabeling were weak or absent in the granule cell layer for α2-, α3-, α4-, α5-, β1- and γ1-subunits (Fig. 18).

Fig. 17.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the cerebellum (horizontal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −3.28 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). The mouse cerebellum displays high concentrations of the α1-, α6-, β2-, β3-, γ2, and δ-subunits mRNA. Note the co-distribution of α6- and δ-subunits. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Fig. 18.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the cerebellar cortex (horizontal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −3.28 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Note the dark subunit α1-, α6- β2-, β3- and δ-immunoreactivity in the granule cell layer (Gr). In the Purkinje cell layer (Pu) a strong immunoreactivity can be seen for α3- and extraordinarily for α4-subunits, but modest Immunoreactivity for α5-, β1- and γ2-subunits. Molecular layer (Mol). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Table 9.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse cerebellum

| Cerebellum | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Molecular layer | + | ++ | + | +++ | (+) | + | (+) | ++ | (+) | (+) | – | + |

| Purkinje cell layer | +++ | – | + | – | (+) | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | (+) |

| Granule cell layer | ++ | +++ | + | + | (+) | (+) | (+) | – | (+) | (+) | +++ | +++ |

| Cerebellar nuclei | +++ | +(+) | – | – | + | +(+) | – | – | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Molecular layer | – | ++ | + | ++ | (+) | + | + | +(+) | + | + | (+) | + |

| Purkinje cell layer | ++(+) | ++ | ++ | (+) | ++ | (+) | (+) | + | +++ | +(+) | (+) | (+) |

| Granule cell layer | +(+) | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | ++ | +(+) | +++ | +++ |

| Cerebellar nuclei | (+) | (+) | + | + | (+) | (+) | + | + | ++ | + | – | (+) |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling.

In the Purkinje cell layer strong ISH signals were apparent for the α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits and modest signals for α4-, β1- and γ1-subunits. In contrast to rat cerebellum a strong immunoreactivity was detected for α3- and extraordinarily for α4-subunits. Immunoreactivity for β1- and γ2-subunits was modest. The remaining subunits revealed no or only faint labeling of the Purkinje cells (Fig. 18).

In the molecular layer rather weak ISH signals occurred for α1-, α2-, β2-, γ1- and γ2-subunits and no labeling for the remaining subunits. Concerning the protein distribution, in contrast to the rat, the strongest immunoreactivity was confined to the α4-subunit. Comparatively high immunoreactivity was found for α1-, α2-, β1- and β2-subunits and modest to weak labeling for α5-, β3-, γ2- and δ-subunits.

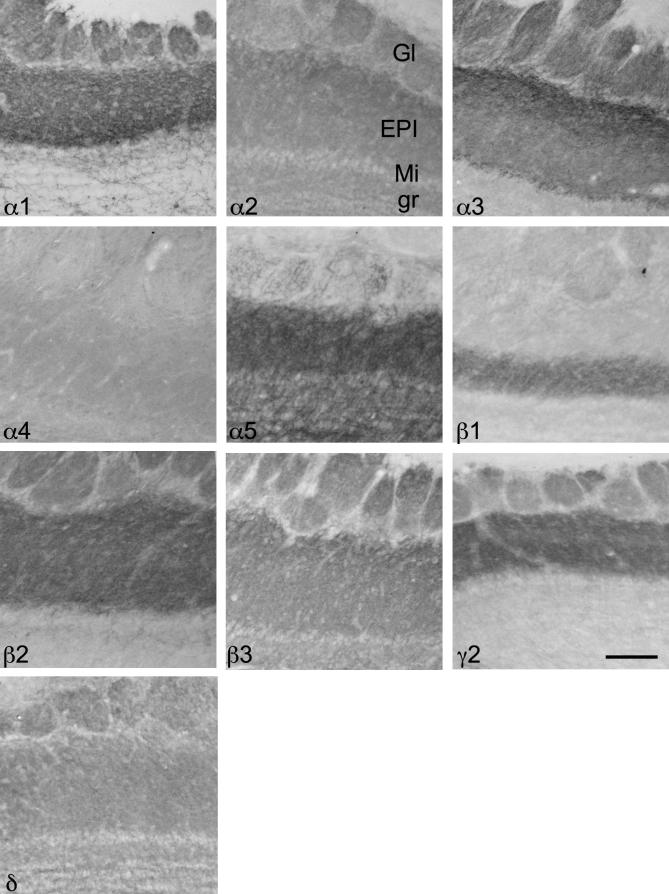

Distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the mouse olfactory bulb

The distribution of mRNA and protein labeling for the GABAA receptor subunits are summarized in Figs. 19 and 20 as well as in Table 10. ISH revealed a strong and layer specific labeling for all subunits except for α6 and a very faint labeling for γ1. A comparable distribution pattern was obtained for α1-, α3-, β2- and γ2-subunits, namely strong signals in mitral cell layer and glomerular layer and a weak or almost no signal in the granular cell layer. A comparable distribution for ISH signals was observed for α2-, α5-, β3- and δ-subunits revealing a strong labeling of the granular layer.

Fig. 19.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ) in the bulbus olfactorius (horizontal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −3.60 to −3.28 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). In situ hybridization reveals a strong and layer specific labeling for all subunits except for α6 and a very faint labeling for γ1. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Fig. 20.

Distribution of the GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities (α1–α5, β1–β3, γ2 and δ) in the bulbus olfactorius (horizontal sections of the mouse brain approximately Bregma −3.60 to −3.28 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos, 2007). Note the strong signals for α1-, α3-, β2- and γ2-subunits in the external plexiform layer (EPI) and glomerular layer (Gl), and only a weak labeling in the granular cell layer (gr). A strong labeling of the mitral cell layer (Mi) only occurs for the α3-subunit. In gr a strong labeling for α5- and β3-subunits and moderate labeling for α2- and δ-subunits is visible. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Table 10.

Density of in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) labelings for the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in various regions of the mouse bulbus olfactorius

| Bulbus olfactorius | α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Glomerular layer | +(+) | +++ | (+) | ++ | +++ | +++ | (+) | + | (+) | (+) | – | – |

| Ext. plexiform layer | + | +++ | + | +++ | + | +++ | + | ++ | + | +++ | – | – |

| Mitral cell layer | +++ | (+) | + | (+) | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | – | – |

| Granular cell layer | – | + | ++(+) | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| β1 |

β2 |

β3 |

γ1 |

γ2 |

δ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | ISH | IHC | |

| Glomerular layer | + | + | +(+) | +++ | ++ | +++ | (+) | (+) | +++ | ++ | +(+) | +(+) |

| Ext. plexiform layer | + | +++ | + | +++ | + | +++ | (+) | (+) | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| Mitral cell layer | ++ | (+) | +++ | (+) | ++ | + | (+) | + | +++ | (+) | ++ | (+) |

| Granular cell layer | ++ | (+) | (+) | (+) | +++ | ++ | (+) | (+) | +(+) | + | +++ | +(+) |

– no labeling; (+) faint labeling; + weak labeling; ++ moderate labeling; +++ strong labeling.

On the protein level a comparable labeling pattern was obtained for α1-, α3-, β2- and γ2-subunits, namely strong signals in the external plexiform layer and glomerular layer and only a weak labeling in the granular layer. A strong labeling of the mitral cells only occurred for the α3-subunit. In the granular cell layer a strong labeling for α5- and β3-subunits and moderate labeling for α2- and δ-subunits was seen. Interestingly, in the external plexiform layer the presence of most subunits was proven with the exception of α6- and γ1-subunits. For the β1-subunit only the inner half of the external plexiform layer was strongly labeled (for more details see Fig. 20; Table 10).

Discussion

The present study provides, for the first time, a concomitant comprehensive analysis of the mRNA and protein distribution of 12 GABAA receptor subunits, α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1, γ2 and δ in the mouse brain. Our findings mostly confirm the mRNA distribution pattern of seven GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1–α3, α5, β2, β3 and γ2) previously described in the forebrain and midbrain (Heldt and Ressler, 2007a). Our data are also consistent with previous reports on the distribution of some of the mouse GABAA receptor subunit proteins in the amygdala (Tasan et al., 2011), hippocampus (Peng et al., 2004; Sassoè-Pognetto et al., 2009), thalamus (Peng et al., 2002) and cerebellum (Jones et al., 1997). Moreover, the presented anatomical localization of the β2-subunit in thalamus and dentate gyrus is in good agreement to the electrophysiological findings of Belelli et al. (2005) and Herd et al. (2008), who confirmed the β2-subunit gene expression by using β2-subunit gene knockout and knock-in point mutations.

One of the aims of the present study was to define the location of the synthesis and final location of the protein of each individual subunit by juxtaposition of ISH and IHC. A second aim was to analyze possible differences in the distribution of the 12 subunits investigated between mouse and rat brains. Moreover, we tried to define co-distributions of specific subunits and to compare these between mouse and rat brains.

Differences in the distribution of mRNA and protein

There is general consensus that the location of mRNA not always reflects that of the protein. In the present study we differentiate whether the protein is located at the cell soma or in dendrites or axon terminals far from the cell body where the mRNA resides. Differences in the location of ISH and immunohistochemical signals for the 12 subunits investigated were observed most frequently in different parts of the hippocampus, the bulbus olfactorius, cerebellum and habenula. Thus, in the hippocampus ISH signals were restricted to the pyramidal cell layer of CA1 to CA3, the granule cell layer and hilus of dentate gyrus, whereas GABAA receptor subunit proteins were predominantly located in the strata oriens and radiatum of CA1 to CA3 and in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and hilus. This implies that the GABAA receptor subunits are predominately targeted to dendrites of granule cells, pyramidal cells and interneurons of these layers. In the hilus of the dentate gyrus the presence of subunits (mRNA and protein) was mainly confined to subunits α1, α2, β1 and β2. In addition faint signals for β3- and γ2-subunit mRNAs were detected.

In the amygdala the rather high expression of the γ1-subunit mRNA in the medial amygdaloid nucleus was associated with only weak immunolabeling.

In the bulbus olfactorius differences in the distribution of mRNA and protein of the various subunits were especially observed in the external plexiform layer and mitral cell layer. In the external plexiform layer a rather weak ISH signal associated with a strong immunohistochemical label was found for all subunits expressed in the bulbus olfactorius. In contrast, in the mitral cell layer a high level of mRNA associated with a faint or low immunohistochemical label occurred for the subunits α1, α5, β1, β2, β3, γ2 and δ. These findings indicate that GABAA receptor subunits synthesized in the cell bodies of mitral cells are transported to the inhibitory dendrodendritic synapses formed with dendritic spines of granule cells in the external plexiform layer as well as with nerve terminals of periglomerular neurons in the glomerular layer (Schoppa and Urban, 2003; Sassoè-Pognetto et al., 2009). Our data on the distribution of α1- and α3-subunits IHC in the external plexiform layer confirm the previous data by Sassoè-Pognetto et al. (2009) demonstrating a uniform distribution of the α1-subunit throughout the external plexiform layer, but a more abundant expression of the α3-subunit in the superficial one-third of the external plexiform layer containing the dendrites of middle and external tufted cells. Moreover, the strong protein expression of α5-, β1-, β2-, β3- and γ2-subunits and moderate expression of α2-, α4- and δ-subunits in the external layer, demonstrated in the present study, indicate the involvement of various GABAA receptor subtypes in the dendrodendritic inhibition of mitral and tufted cells by granule cells. This similarly refers to the glomerular layer.

In the medial habenular nucleus a strong ISH signal for the α2- and γ2-subunits was not followed by an immunohistochemical signal. In the medial septum a moderate presence of α3-mRNA as described previously (Heldt and Ressler, 2007a) has been confirmed. However the α3-mRNA expression was not associated with the corresponding presence of the α3-protein. Likewise, for the γ2-subunit in the medial septum a strong ISH signal, but in contrast to the rat septum only a faint immunohistochemical signal existed.

Differences in the distribution of GABAA receptor subunits between mouse and rat brains

To analyze possible differences in the distribution of the 12 subunits investigated between mouse and rat brains, distributions of mRNA and protein in the rat brain described by Wisden et al. (1992) and Laurie et al. (1992) and by Sperk et al. (1997) and Pirker et al. (2000), respectively, were used. Comparing the overall distribution of GABAA receptor subunit immunoreactivities in the rat (Pirker et al., 2000: Fig. 1) and mouse (Fig. 6) some apparent differences are obvious. Thus immunolabeling of subunits α1, β1, and γ2 appeared to be somewhat stronger in the rat than in the mouse, whereas labeling for α4 and δ was generally stronger in the mouse brain. These differences may either reflect a higher expression of the respective GABAA receptor subunits, or may be due to technical differences in the two studies. Although we used mostly similar but not identical antisera for both studies, the individual antisera in the individual incubations may yield different results in respect to the intensities of labeling. Moreover, it has to be pointed out that differences in staining intensities do not necessarily reflect differences in actual subunit concentrations.

In the hippocampus several differences were obvious. In the dentate gyrus of the mouse, the α3-subunit was not expressed both at the mRNA and protein level. On the other hand an obviously much higher protein expression for the α5- and a higher expression for the δ-subunit were observed in the mouse as compared to rat in the dentate gyrus. In the CA3 area, the immunohistochemical label for α1-, β2- and δ-subunits was much weaker in the mouse than in the rat. The hippocampal distribution of the α3-subunit in the mouse differed strikingly from that in the rat. Whereas in the rat hippocampus mRNA and protein labeling was almost exclusively detected in the dentate gyrus and CA3 (Wisden et al., 1992; Pirker et al., 2000), α3-subunit mRNA and protein labeling in the mouse hippocampus was almost restricted to the CA1 area. Despite the weak and exclusive expression of the α3-subunit in CA1 of the mouse hippocampus, a strong signal both at the mRNA and protein level occurred in the ventral subiculum, parasubiculum and presubiculum, a distribution, which was not seen in the rat. In the hippocampus the labeling of δ-subunit mRNA and protein was most prominent in the dentate gyrus of rat and mouse. However, in the rat subiculum a moderate δ-subunit immunoreactivity in cell bodies and diffuse staining was described (Pirker et al., 2000), which was not detected in the mouse subiculum.

In contrast to the rat hypothalamus immunolabeling of the δ-subunit was not detectable throughout the hypothalamus in the mouse. The absence of δ-subunit protein has been reported previously (Peng et al., 2002). Comparable to the mouse hypothalamus, δ-subunit mRNA was not detectable in the rat hypothalamus according to Wisden et al. (1992).

Among the thalamic nuclei the rat reticular thalamic nucleus displayed high intensities of α3-, β1-, β3- and γ2-subunit-immunoreactivities, whereas in the mouse reticular thalamic nucleus the high intensity of α3-subunit-labeling was associated with a much weaker labeling of α2-, β1-, and γ1-subunits both at the mRNA and protein level (Table 6).

In the amygdala the most obvious mouse-rat-differences were observed in the central nucleus, where no or very faint immunolabeling for α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits occurred in the mouse contrasted by a strong labeling in the rat. In addition, a considerably stronger expression of the α3-subunit in the mouse central and basolateral nucleus was observed both at the mRNA and protein level as compared to rat amygdala. The immunolabeling of the α5-subunit revealed a much stronger signal in the central nucleus than in the basolateral amygdala, a difference which was not described in the rat amygdala (Pirker et al., 2000). The strong immunolabeling of the γ1-subunit in the medial amygdaloid nucleus detected in the rat (Pirker et al., 2000) was not visible in the mouse (Fig. 16).

In the cerebellum the most striking difference was the strong protein signal for α3-, α4- and γ2-subunits in the Purkinje cell layer, but almost no labeling in the Purkinje cell layer of the rat (Laurie et al., 1992; Pirker et al., 2000). In the molecular layer of the mouse cerebellum the strongest immunoreactivity was confined to the α4-subunit, which highly contrasts the distribution of the α4-subunit protein in the rat cerebellum. In the mouse cerebellum rather faint α5-subunit protein was located in the Purkinje cell layer, whereas in the rat cerebellum α5-subunit protein has been demonstrated to be distributed in all three layers, with a stronger labeling of the molecular layer (Pirker et al., 2000).

In the bulbus olfactorius mouse versus rat differences were observed especially in the mitral cell layer and granular layer, where only weak immunolabeling was found for α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits in the mouse, but strong labeling in the rat. On the other hand a much stronger immunolabeling existed for the α3- and α4-subunits in the mouse mitral cell layer than in that of the rat. In contrast to the rat, δ-subunit protein was absent in the mouse mitral cell layer. At the mRNA level striking differences were seen especially for the distribution of α3-, α4-, β1-, γ2- and δ-subunits in the mouse bulbus olfactorius (Fig. 19, Table 10) in comparison to the rat (Wisden et al., 1992; Laurie et al., 1992).

Co-distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in various areas of the mouse brain

The co-distribution of GABAA receptor subunits is of special interest, since the subunit composition defines the synaptic or extrasynaptic localization and influences the biophysical and pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors. Thus, whereas α1-, α2- and γ2-subunit-containing receptors are mainly located within the synapse and mediate phasic inhibition, α4-, α5-, α6- and γ2- and δ-subunit-containing receptors are often located extrasynaptically mediating tonic inhibition.

Co-distribution of α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits

In the rat brain α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits are considered as the most abundant GABAA receptor subunits (Pirker et al., 2000; Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). Similarly, in the mouse brain a co-distribution, intensity of labeling and/or co-missing of these three subunits on the mRNA as well as protein level was observed all over the brain. This refers to all layers of the bulbus olfactorius and cerebellum (exception: higher immunolabeling for γ2-subunit in the rat). An excellent co-distribution of α1-, β2- and γ2-subunits with corresponding labeling intensity was detected in all areas of the hippocampus including ventral subiculum, parasubiculum and presubiculum. Moreover, comparable labeling patterns for these three subunits appeared throughout the basal ganglia and the amygdala. With the exception of the perigeniculate nucleus the staining intensity of the γ2-subunit in the thalamus was considerably lower than that of the α1- and β2-subunits.

Co-distribution of α4- and δ-subunits

As demonstrated in the rat brain (Pirker et al., 2000) subunit α4- and δ-immunoreactivity displayed typical patterns of co-distribution preferentially in the thalamus, striatum, accumbens and dentate gyrus. The co-distribution is extended in the mouse to the bulbus olfactorius both at the mRNA and protein level. However, in the granule cell layer of rat cerebellum it is well established that the δ-subunit no longer co-localizes with the α4-subunit, but is associated with the α6- and β2/3-subunits in extrasynaptic location (Nusser et al., 1998; Pirker et al., 2000). This co-distribution, specific for the cerebellum, has also been demonstrated in the mouse cerebellum (Jones et al., 1997) and was now confirmed both by ISH and IHC. Notably, evidence has been provided that α6-subunit gene inactivation inhibits the expression of the δ-subunit in the membrane without changing levels of δ-subunit mRNA (Jones et al., 1997). The inhibition of δ-subunit expression was underlined by the almost total loss of high-affinity binding of [3H]-muscimol, a selective autoradiographic probe for α6- and δ-subunit association, from the cerebellar granule cell layer in the α6-subunit−/− mice (Jones et al., 1997).

On the other hand, the α4-subunit was found expressed independently of the presence of the δ-subunit in the lateral septum, central nucleus of the amygdala and in the CA1–CA3 region of the mouse hippocampus. This localization of the α4-subunit independent of the δ-subunit e.g. in the CA1 region agrees with previous mRNA findings in the rat hippocampus (Wisden et al., 1992).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present data provide for the first time a clear overview on the localization of the GABAA receptor subunits α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1–γ2 and δ in the mouse brain at the mRNA level as well as the protein level. In different brain areas we were able to demonstrate that mRNA levels did not reflect protein levels, indicating that the protein is located far distant from the cell body. Moreover, although in general there is a considerable correspondence in the anatomical distribution and co-distribution of the 12 subunits investigated between mouse and rat brains, several species-specific differences have to be taken into account.

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF Projects S10204 and P19464 to G.S.).

Contributor Information

H. Hörtnagl, Email: heide.hoertnagl@i-med.ac.at.

G. Sperk, Email: guenther.sperk@i-med.ac.at.

References

- Belelli D., Peden D.R., Rosahl T.W., Wafford K.A., Lambert J.J. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors of thalamocortical neurons: a molecular target for hypnotics. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11513–11520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2679-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov Y.A., Jung S., Alva H., Wallace D., Rosahl T., Whiting P.J., Harris R.A. Deletion of the alpha1 or beta2 subunit of GABAA receptors reduces actions of alcohol and other drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:30–36. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M., Brauchart D., Boresch S., Sieghart W. Comparative modeling of GABA(A) receptors: limits, insights, future developments. Neuroscience. 2003;119:933–943. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M., Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H.-J., Kang J.-Q., Song L., Dibbens L., Mulley J., Macdonald R.L. δ Subunit susceptibility variants E177A and R220H associated with complex epilepsy alter channel gating and surface expression of α4β2δ GABAA receptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1499–1506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2913-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K.B.J., Paxinos G. third ed. Elsevier; London: 2007. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy J.-M., Mohler H. GABAA receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt S.A., Ressler K.J. Forebrain and midbrain distribution of major benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptor subunits in the adult C57 mouse as assessed with in situ hybridization. Neuroscience. 2007;150:370–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt S.A., Ressler K.J. Training-induced changes in the expression of GABAA-associated genes in the amygdala after the acquisition and extinction of Pavlovian fear. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3631–3644. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd M.B., Haythornthwaite A.R., Rosahl T.W., Wafford K.A., Homanics G.E., Lambert J.J., Belelli D. The expression of GABAA β subunit isoforms in synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor populations of mouse dentate gyrus granule cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:989–1004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A., Korpi E.R., McKernan R.M., Pelz R., Nusser Z., Mäkelä R., Mellor J.R., Pollard S., Bahn S., Stephenson F.A., Randall A.D., Sieghart W., Somogyi P., Smith A.J.H., Wisden W. Ligand-gated ion channel subunit partnerships: GABAA receptor 6 subunit gene inactivation inhibits δ subunit expression. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1350–1362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01350.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K. Novel GABAA receptor alpha subunit is expressed only in cerebellar granule cells. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:619–624. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90276-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie D.J., Seeburg P.H., Wisden W. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the brain. II. Olfactory bulb and cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1063–1076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01063.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wang X. Genes associated with idiopathic epilepsies: a current overview. Neurol Res. 2009;31:135–143. doi: 10.1179/174313209X393942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]