Background: Some of the enzymes that are required for LPS modification(s) are unknown.

Results: LPS modifications involving addition of glucuronic acid to heptose III and phosphoethanolamine transfer to heptose I require products of two new genes waaH and eptC, respectively.

Conclusion: Glucuronic acid addition requires PhoB/R activation, and phosphoethanolamine transfer confers detergent resistance.

Significance: Nonstoichiometric LPS alterations reflect LPS structural flexibility in response to stress conditions.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, Glycobiology, Glycosyltransferases, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Oligosaccharide, Glucuronic Acid, Phosphoethanolamine

Abstract

It is well established that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) often carries nonstoichiometric substitutions in lipid A and in the inner core. In this work, the molecular basis of inner core alterations and their physiological significance are addressed. A new inner core modification of LPS is described, which arises due to the addition of glucuronic acid on the third heptose with a concomitant loss of phosphate on the second heptose. This was shown by chemical and structural analyses. Furthermore, the gene whose product is responsible for the addition of this sugar was identified in all Escherichia coli core types and in Salmonella and was designated waaH. Its deduced amino acid sequence exhibits homology to glycosyltransferase family 2. The transcription of the waaH gene is positively regulated by the PhoB/R two-component system in a growth phase-dependent manner, which is coordinated with the transcription of the ugd gene explaining the genetic basis of this modification. Glucuronic acid modification was observed in E. coli B, K12, R2, and R4 core types and in Salmonella. We also show that the phosphoethanolamine (P-EtN) addition on heptose I in E. coli K12 requires the product of the ORF yijP, a new gene designated as eptC. Incorporation of P-EtN is also positively regulated by PhoB/R, although it can occur at a basal level without a requirement for any regulatory inducible systems. This P-EtN modification is essential for resistance to a variety of factors, which destabilize the outer membrane like the addition of SDS or challenge to sublethal concentrations of Zn2+.

Introduction

The outer membrane (OM)2 of Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli is an asymmetric bilayer with the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet (1). LPS are the major amphiphilic constituents of the outer leaflet of the OM. LPS is essential for the bacterial viability and integrity of the OM and provides the permeability barrier function. LPS in general share a common structure composed of an acylated and 1,4′-diphosphorylated β(1→6)-linked glucosamine (GlcN) disaccharide, called lipid A (2, 3). To the lipid A is attached a proximal core oligosaccharide and, in smooth-type bacteria, a distal O-polysaccharide (2). In E. coli, the core oligosaccharide can be subdivided into the inner and outer core, and distinct core types have been described (R1, R2, R3, R4, and K12) that differ in the outer core structure (4–6). The inner core is a more conserved structural element of 3-deoxy-α-d-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosonic acid (Kdo), l-glycero-α-d-manno-heptopyranose (Hep), and phosphate residues. Kdo2-lipid A is considered to be the minimal LPS structure required for viability of bacteria like E. coli under optimal growth conditions. The predominant core types among clinical isolates are R1 and R3 (4). Importantly, verotoxigenic isolates belonging to the common enterohemorrhagic E. coli such as serogroups O157, O111, and O26 produce LPS of the R3 core type (4, 7). Both of these core types contain structural modifications of the side-chain heptose (HepIII) of the inner core due to a nonstoichiometric incorporation of an α(1→7)-linked GlcN residue (5, 6, 8, 9). This modification is accompanied by a concomitant loss of phosphate at the HepII (10), thereby modifying the charge distribution of the inner core.

The importance of heptose incorporation into the inner core is manifested by our discovery that all genes whose products are required either for heptose biosynthesis or its incorporation are also required for growth at critical high temperatures (11). These include biosynthetic genes for heptose (gmhA, gmhB, and gmhD) and the heptosyltransferases I (waaC) and II (waaF) (11).

Phosphorylation of the inner core HepI plays a crucial role in the OM stability (12). In the absence of phosphorylation of HepI, HepIII is not incorporated, and HepII phosphorylation is impaired, leading to a truncation of LPS accompanied by permeability and motility defects (deep-rough phenotype) (12). A requirement for the OM permeability/barrier function therefore seems to place structural constraints on the inner core of LPS, accounting for conservation of its base structure (3, 8).

Despite conservation of lipid A and inner core structure, challenges to different stresses, like changes in pH, concentrations of specific ions, and phosphate starvation, are structurally modified by nonstoichiometric substituents. These modifications often result in a modulation of the number of net negative charges. Among the nonstoichiometric substitutions commonly observed in the lipid A are the addition of phosphoethanolamine (P-EtN) and 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (Ara4N) (13). Some of these substitutions provide advantages under specific growth niches. For example, the incorporation of P-EtN and Ara4N is known to confer resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides like polymyxin B (13). Nonstoichiometric structural variations of the E. coli inner core include phosphate, GlcN, rhamnose (Rha), P-EtN, and additional Kdo (8). Some of these substitutions are specific to the individual core type of E. coli. Among these, the physiological significance of P-EtN addition to the second Kdo and phosphorylation of HepI have been addressed to some extent (12, 14, 15).

The nonstoichiometric modifications of the lipid A are positively regulated by the BasS/R two-component system (13). These modifications in the lipid A part arise due to incorporation of P-EtN and Ara4N. In E. coli, EptA is required for the P-EtN transfer to lipid A. The addition of P-EtN to the second Kdo requires EptB (14). The transcription of the eptB gene is induced under conditions of envelope stress and is also negatively controlled by mgrR sRNA (16, 17). The E. coli genome also contains three additional ORFs (ybiP, ybhX, and yijP) whose encoded amino acid sequence bears significant homology to EptA, EptB, and other P-EtN transferases. The nonstoichiometric incorporation of P-EtN to the inner core phosphate of HepI in Salmonella is positively regulated by the PmrA/B two-component system (18). In E. coli, the gene required for this modification was not known, and the corresponding two-component system BasS/R did not seem to be required for changes in the structure of the inner core (15).

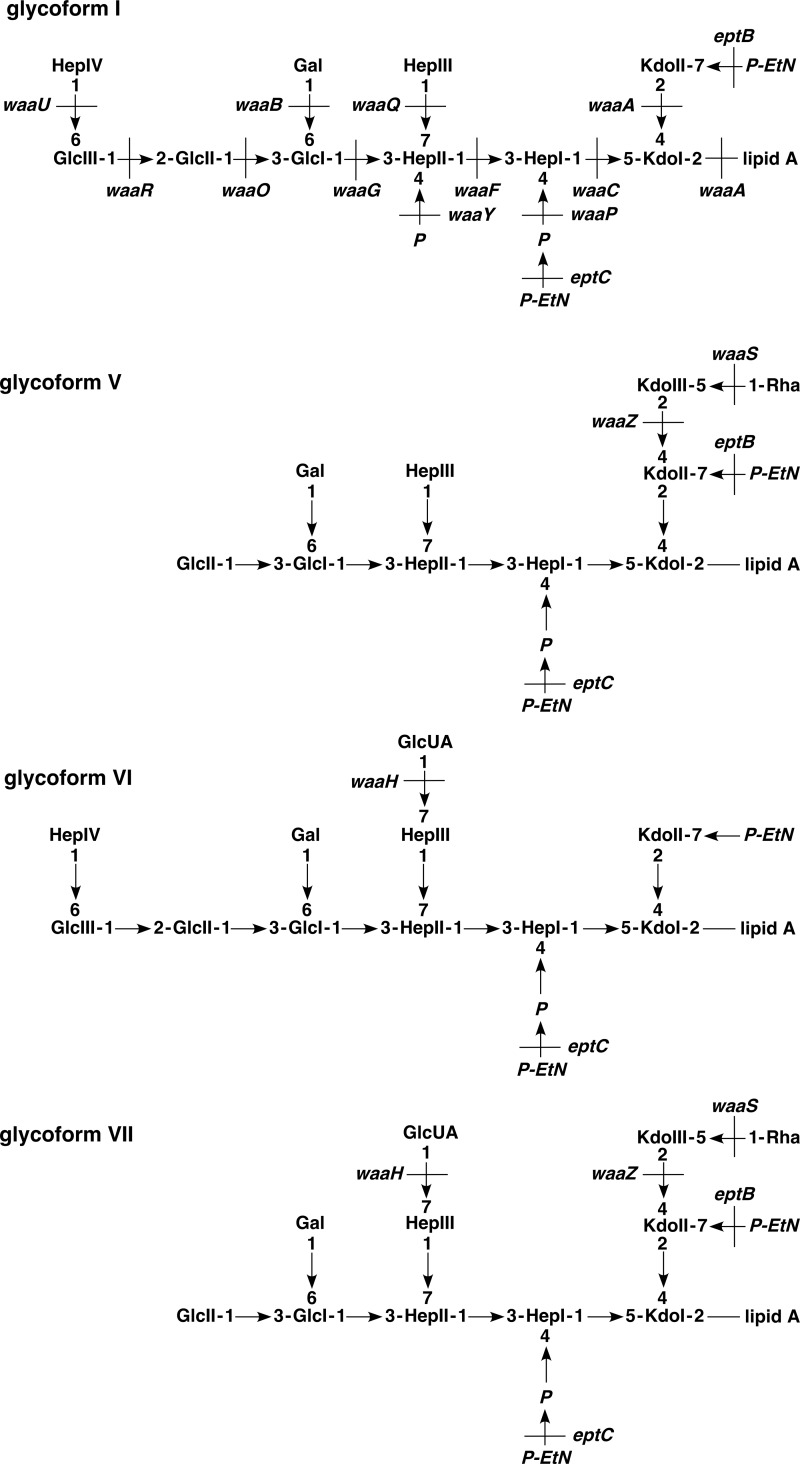

We recently addressed the molecular basis of LPS heterogeneity in E. coli K12 (15). During this analysis, we addressed the role of RpoE and its regulators, because RpoE controls and responds to major outer membrane defects (15). Induction of RpoE was found to lead to the increased abundance of glycoforms with a third Kdo accompanied by a truncation in the outer core. This was found to be regulated by the translational repression of WaaR glycosyltransferase due to RpoE-dependent rybB sRNA (15). Furthermore, RpoE induction causes preferential accumulation of glycoform V with Rha attached to the third Kdo and P-EtN on the second Kdo (Fig. 1) (15).

FIGURE 1.

Proposed LPS structures from E. coli K12 in phosphate-limiting growth conditions. Schematic drawing of LPS glycoforms I, V, VI, and VII composition with various nonstoichiometric substitutions in the LPS core region is presented. Glycoforms VI and VII have GlcUA addition on the HepIII. The cognate genes, whose products are involved at different steps, are indicated.

We also showed that LPS heterogeneity is additionally regulated by two-component systems PhoB/R and BasS/R (15). PhoB/R system responds to phosphate limitations, which partially overlaps with BasS/R system. However, the latter was found to be highly inducible under phosphate-limiting conditions when the culture medium was supplemented by submillimolar concentrations of Zn2+ and Fe3+ (17). Under such growth conditions, we showed by mass spectrometry that the LPS of the wild-type E. coli K12 as well as that of E. coli B contains several signals 96 mass units higher than the LPS obtained from bacteria grown under phosphate-rich growth conditions in M9 or LB medium. This modification, specific to the core region, was found to occur in the most common glycoform I as well as in glycoforms IV and V (Fig. 1) and was not induced by the extracytoplasmic function σ factor RpoE or the BasS/R two-component system (15). Also, such modified LPS contained up to three P-EtN residues. One of them was assigned to the lipid A and another to the second Kdo, and the third was predicted to modify phosphorylated HepI (15, 17).

Thus, in this work, we determined the chemical structure of the modified LPS. We describe a novel inner core modification of E. coli LPS arising from the addition of glucuronic acid (GlcUA) to HepIII, with concomitant loss of phosphate on HepII. We also identified the required gene whose product encodes the candidate glycosyltransferase. Mutational analysis and structural examination of LPS allowed us to identify the P-EtN transferase responsible for the addition of P-EtN to phosphorylated HepI. We designated the corresponding gene as eptC and examined the physiological significance of this modification.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Media

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, M9, and 121 phosphate-limiting minimal media were prepared as described (15, 19, 20). When necessary, media were supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (50 μg ml−1), or chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1). The indicator dye 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) was used at a final concentration of 40 μg ml−1 in the agar medium.

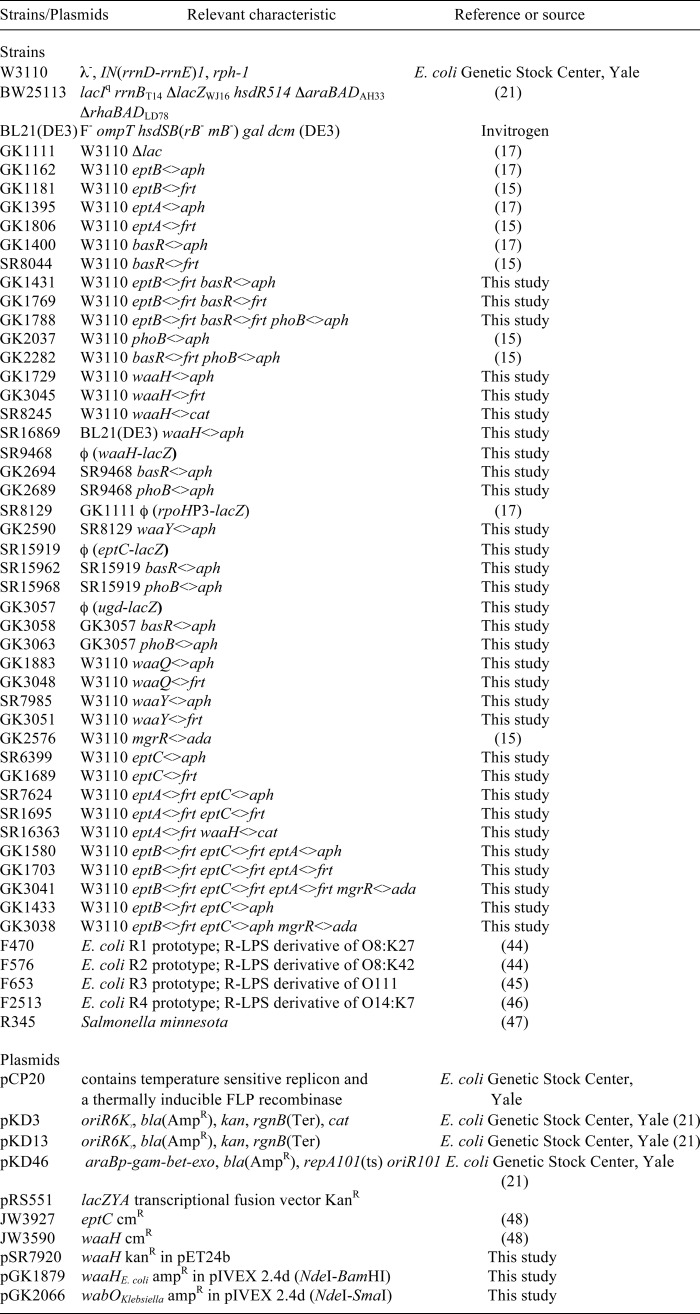

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

Generation of Null Mutations and Construction of Their Combinations

Nonpolar antibiotic-free deletion mutations of various genes were constructed by using the λ Red recombinase/FLP-mediated recombination system (21). The coding sequence of each gene was replaced with either the kanamycin (aph) or chloramphenicol (cat) resistance cassette flanked by FRT recognition sequences, using plasmid pKD13 and pKD3 as templates (21). PCR products were used for recombineering on the chromosome of either E. coli K12 strain BW25113 or E. coli B strain BL21 (DE3) containing the λ Red recombinase-encoding plasmid pKD46. Gene replacements and their exact chromosomal locations were verified by PCR and further transduced into either W3110 or in BL21. Multiple null combinations were made through a series of bacteriophage P1-mediated transductions, followed by the removal of the aph or cat cassettes. All the deletions were confirmed to be nonpolar. Construction of deletion derivatives of the eptA, eptB, basR, phoB, and mgrR genes in W3110 were described previously (15, 17).

For protein induction, the minimal coding sequence of the waaH gene of E. coli was cloned in expression vectors pET24b (NdeI-XhoI) (pSR7920) and pIVEX 2.4d (NdeI-BamHI) (pGK1879). In parallel, the wabO gene (ORF10) from Klebsiella pneumoniae was cloned to verify any complementation or overlap in function. WabO is responsible for transfer of galacturonic acid (GalA) linked to HepIII in K. pneumoniae (22). The minimal coding sequence of the wabO gene from K. pneumoniae was amplified by PCR and used to express in pIVEX 2.4d vector (NdeI-SmaI) (pGK2066).

Analysis of Permeability Defects

Growth of the wild type and its isogenic ΔwaaH, ΔeptA, ΔeptB, and ΔeptC derivatives and their combinations was analyzed either in phosphate-limiting medium or LA in the presence of different concentration of SDS, Fe3+, or Zn2+. Bacterial cells grown overnight at 30 °C were diluted to an A595 of 0.1. Such cultures were further serially diluted (10−1–10−6). Five μl of each dilution was spotted on plates containing SDS (concentration 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2%) or 1.5 mm Fe3+ or Zn2+ (20 and 150 μm). Expression of the cloned wild-type eptC gene was achieved by the addition of 0.05 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h.

β-Galactosidase Assays

To measure the activity of waaH, ugd, and eptC promoters, single copy chromosomal promoter fusions to the lacZ gene were constructed. The induction of the RpoE pathway was monitored in strains carrying an rpoHP3-lacZ promoter fusion, whose construction has been previously described (23). The putative promoter regions of waaH, ugd, and eptC genes were amplified by PCR, using specific oligonucleotides (supplemental Table S1). After PCR amplification, gel-purified DNA was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, cloned into either pRS551 or pRS415 promoter probe vectors, and transferred to the chromosome in single copy by recombination with λRS45, selecting for lysogens as described previously for other promoter fusions (23–25). β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described previously (15).

Protein Purification

Expression of hexa-His-tagged WaaH was induced in the strain E. coli BL21 at an absorbance of 0.1 at 600 nm in a 1-liter culture by the addition of 1 mm IPTG. After induction (4 h at 37 °C), cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole (buffer A)) supplemented with lysozyme to a final concentration of 200 μg ml−1. After incubation on ice for 20 min, the mixture was sonicated and centrifuged at 45,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Soluble proteins (15 ml) were applied over nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen), washed, and eluted with buffer A containing 150 mm imidazole.

LPS Extraction

For most of the experiments, cultures of isogenic bacteria were grown in a rotary shaker at 190 rpm in the phosphate-limiting medium with appropriate antibiotic at 37 °C until an absorbance of 0.8–1.0 at 600 nm. In specific cases, LPS from Salmonella and different representative E. coli core types was obtained from cultures grown in LB medium with or without supplementation of 25 mm ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO3). Four hundred-ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 30 min and dried. LPS was extracted by the phenol/chloroform/petroleum ether procedure (26) and lyophilized. For the LPS analysis, lyophilized material was dispersed in water by sonication and resuspended at a concentration of 2 mg ml−1.

For the LPS analysis by NMR spectroscopy, E. coli BL21 strain was grown in 40 liters of phosphate-limiting 121 medium at 37 °C for 24 h under shaking (150 rpm). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (8671 × g, 20 min, 4 °C) and were washed once with ethanol, twice with acetone, and once with diethyl ether and then dried at ambient temperature (yield 12 g). The LPS was obtained by the phenol/chloroform/petrol ether extraction (yield 654 mg) and successively O- and N-deacylated by hydrazinolysis (37 °C, 30 min, yield 431 mg) and a modified alkaline hydrolysis under reducing conditions, respectively. The dry de-O-acylated sample was dissolved in 18 ml of 4 m KOH containing 25 mm NaBH4 and incubated at 100 °C for 16 h. After acidification with 4 m HCl, fatty acids were extracted with chloroform three times, and the water phase was desalted using BioGel P2 (Bio-Rad) in water and lyophilized (yield 195 mg). Of these, 50 mg were separated by high performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC; 5 runs of 10 mg each) using a semi-preparative CarboPak PA100 column (9 × 250 mm) and a DX300 chromatography system (Dionex). Fractions were analyzed by analytical HPAEC, and those containing the main oligosaccharide were combined and desalted on Sephadex G-10 (GE Healthcare) in 10 mm NH4HCO3 buffer (yield 3.6 mg). Conditions for semi-preparative and analytical HPAEC were essentially as described previously (6).

NMR Spectroscopy

For NMR spectroscopy, 3 mg of the purified and lyophilized main oligosaccharide were exchanged three times with D2O by rotary evaporation and finally dissolved in 400 μl of D2O (99.98%, Deutero GmbH). To ensure a uniformly charged state of the oligosaccharide, NaOD (4 μl of 40%) was added. NMR spectra were recorded at 300 K on a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz ultrashield plus spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm CPQCI 1H-31P/13C/15N/D Z-GRD probe head. One-dimensional 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra, two-dimensional 1H,1H-DQF-COSY (cosydfphpr), NOESY (noesyphpr, 200-ms mixing time), TOCSY (mlevphpr, 90-ms spin lock, 26-μs 90° low power pulse at −1.33 db power), ROESY (roesyphpr, 200-ms spin lock pulse at 8.43 db), and 1H,13C-HSQC (hsqcphpr), HSQC-TOCSY (hsqcgpmlph, 120-ms spin lock, 90° spin lock pulse 26 μs at −1.33 db), and a 1H,13C-HMBC optimized for long range coupling constants of 10 Hz (hmbcgplpndqf) were recorded using the indicated Bruker standard pulse programs. The spectra were referenced to the methyl signals of acetone (1H, 2.225 ppm) (13C, 31.5 ppm) and external phosphoric acid (85% in water, 31P, 0 ppm) and analyzed using Bruker TopSpin version 3.0 software.

Mass Spectrometry

Electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron-mass spectrometry was performed on intact and deacylated LPS in the negative ion mode using an APEX QE (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) equipped with a 7 tesla actively shielded magnet and dual ESI-MALDI. LPS samples were dissolved at a concentration of ∼10 ng μl−1 and analyzed as described previously (17, 27). Mass spectra were charge-deconvoluted, and the mass numbers given refer to the monoisotopic peaks. Mass calibration was done externally using well characterized similar compounds of known structure (27).

For gas-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (GLC-MS) analysis, authentic glucuronic acid (kindly provided by Tim Steffens, Research Center Borstel), the purified OS1 (100 μg), and native LPS (500 μg) were subjected to methanolysis (0.5 m HCl in methanol, 45 min, 85 °C), dried under a stream of nitrogen, and peracetylated in pyridine/acetic anhydride (1:1). The sample was then carboxyl reduced with NaBD4 (1 mg of NaBD4 in 150 μl of MeOH/H2O, 4 h, room temperature). To convert the remaining disaccharides into the methyl glycosides, a second methanolysis was performed (2 m HCl in methanol, 3 h, 85 °C); the sample was peracetylated, and after hydrolysis with trifluoroacetic acid (4 m TFA, 2 h, 100 °C), carbonyl was reduced with NaBH4 (1 mg of NaBH4 in 150 μl of MeOH/H2O, 4 h, room temperature) and peracetylated. GLC-MS analysis was performed on an Agilent 5975 system equipped with an HP 5NS column. The measurement was performed under S-tune conditions. The samples were applied at an initial temperature of 70 °C, which was held constant for 1.5 min, and a pressure of 10 p.s.i. corresponding to a flow rate of ∼1 ml/min. The temperature was raised to 150 °C using a linear gradient of 60 °C/min, held for 3 min at this temperature, and finally increased to 320 °C over 5 min. The spectra were analyzed using Software MSD ChemStation D.02.00.275 (Agilent Technologies).

RESULTS

Structural Analysis of Deacylated LPS

As shown earlier, the E. coli B LPS is less heterogeneous than LPS from E. coli K12 because it is mainly composed of a hexaacylated lipid A containing two Kdo, three Hep, two Hex, and a phosphate (15). In this LPS, a large proportion of molecules is 96 mass units higher than the known corresponding glycoforms of E. coli K12 (15). Therefore, we analyzed E. coli B LPS, which, after successive O- and N-deacylation of extracted LPS, yielded one main oligosaccharide and several minor fractions in HPAEC. The major signals of Glc, Hep, Kdo, and a hexuronic acid were identified in addition to minor signals from disaccharides composed of hexuronic acid-Hep, Hep2, and GlcN2. The fragmentation pattern of the hexuronic acid in GLC-MS was identical to authentic peracetylated GlcUA. After carboxyl reduction with NaBD4, hydrolysis, reduction with NaBH4, and peracetylation, only derivatives of Glc, GlcN, and Hep were present.

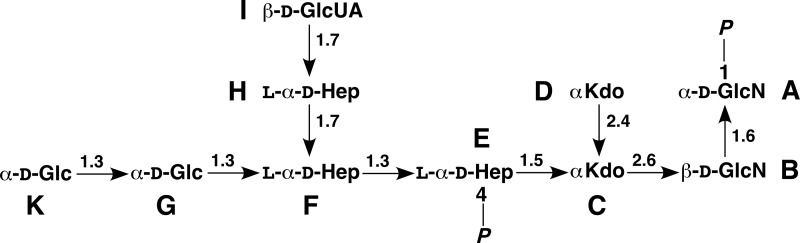

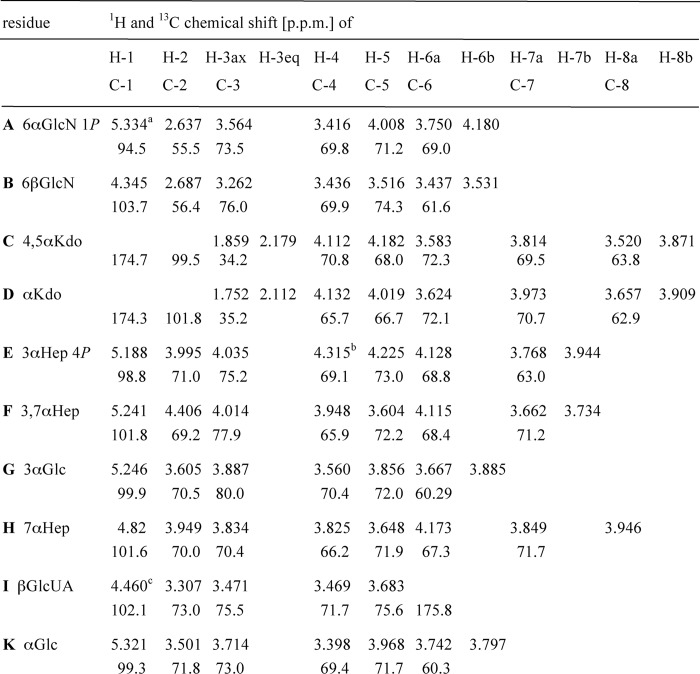

The mass spectrometric analysis of the deacylated LPS by electrospray ionization-Fourier transform-ion cyclotron MS showed a major ion signal with 2016.5307 m/z in the charge-deconvoluted mass spectrum. The chemical structure of the isolated main oligosaccharide was determined by one- and two-dimensional 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectroscopy (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). The assignment of signals (Table 2) revealed that it was a decasaccharide composed of two αGlc (residues G and K, 3JH1,H2 3.6 and 3.8 Hz, respectively), three l-glycero-α-d-manno-heptoses (Hep, residues E, F, and H, all 3JH1,H2 <2 Hz), two Kdo (residues C and D), one αGlcN (residue A), one βGlcN (residue B, 3JH1,H2 8 Hz), and one hexuronic acid, which was identified by vicinal 3JH,H coupling constants as βGlcUA (residue I, 3JH1,H2 8 Hz) as depicted in Fig. 2. This composition (Mtheoret. 2016.53) was consistent with the mass spectrometric analysis. All residues were present as pyranoses. Only two signals of phosphates appeared in the 31P NMR spectrum, which were located at O-1 of the αGlcN (residue A) and at O-4 of Hep (residue E) according to cross-correlation signals in a two-dimensional 1H,31P-HSQC spectrum. The 4′-phosphate was according to mass spectrometry almost quantitatively substituted with Ara4N in the LPS (m/z 3770.7) and therefore eliminated under the strong alkaline conditions used for the N-deacylation. This assignment was indirectly confirmed by additional coupling constants of the proton signals (3JP,H 8 Hz (residue A) and 3JP,H 10 Hz (residue E)) at the substitution sites. The βGlcN was attached to position 6 of the αGlcN1P, which were thus the residues of lipid A. The chemical shift analysis was consistent with the presence of an α(2→4)-linked Kdo disaccharide (residues C and D) attached to position 6 of the βGlcN (residue B) (28). This was confirmed by NOE analysis (strong NOE from H-6 of residue D to H-3e of residue C, see Table 3) (29). Low field chemical shifts of 1H and 13C signals at linkage sites and cross-correlation signals in NOESY showed that the Hep residues formed the trisaccharide αHep-(1→7)-αHep (1→3)αHep common to the E. coli LPS core region, which was connected to position O-5 of the inner Kdo (residue C). The αGlc residues were the first two (1→3)-linked residues of the outer core connected to position O-3 of the middle Hep (residue F). Finally, the βGlcUA was attached to O-7 of the side-chain Hep (residue H), which was inferred from NOESY correlation signals between the anomeric proton and H-7a and -7b of this Hep and low field chemical shifts of the latter signals. Simultaneously, the phosphate commonly found at position O-4 of the middle Hep (residue F) was absent. Thus, these results for the first time show that E. coli LPS obtained under phosphate-limiting growth conditions contains GlcUA attached to HepIII, and its presence coincides with the absence of phosphate on HepII.

TABLE 2.

Chemical shift analysis of the main oligosaccharide from E. coli B deacylated LPS

a 3JP,H1 was 8 Hz.

b 3JP,H4 was 10 Hz.

c 3JH1,H2 was 7.8 Hz; 3JH2,H3 was 10 Hz; 3JH3,H4 was 10 Hz; and 3JH4,H5 was 7 Hz.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structure of the main oligosaccharide from deacylated E. coli B LPS.

TABLE 3.

Observed NOE in two-dimensional NOESY of the main oligosaccharide from E. coli B LPS

| Residue | Proton | Contact proton |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraresidual | Inter-residual | |||

| A | 6αGlcN 1P | H-1 | A2 | |

| B | 6βGlcN | H-1 | B2,3,5 | A6b |

| C | 4,5αKdo | H-3a | C4,5 | H1, E1,E5, D6, F7a,F7b,E7b,D8a |

| H-3e | C4,5 | E2,E5, D6,8b | ||

| D | αKdo | H-3a | D4 | |

| H-3e | D4 | E1,E5,E7b,E7a | ||

| E | 3αHep 4P | H-1 | E2 | C5,7 |

| F | 3,7αHep | H-1 | F2,5 | E2,3 |

| G | 3αGlc | H-1 | G2 | F3,4 |

| H | 7αHep | H-1 | H2 | F6,F7a/b |

| I | βGlcUA | H-1 | I2,I3,I5 | H7a,H7b |

| K | αGlc | H-1 | K2 | G3 |

Determination of the Minimal in Vivo LPS Structure That Supports the Incorporation of GlcUA

Previous analyses of LPS composition of E. coli K12 strains grown in phosphate-limiting growth conditions revealed several new molecules differing from known glycoforms by an additional 96 mass units (15). Such mass peaks with an additional 96 Da were found in glycoforms with either two or three Kdo residues with complete inner core (15), resulting in new glycoforms VI and VII (Fig. 1). Because the same modification was observed in E. coli B and is shown above to arise due to GlcUA addition, we examined the molecular basis of its incorporation in genetically well defined E. coli K12. Mass spectrometric analyses of LPS obtained from isogenic strains with in-frame deletions in various structural genes of the waa region revealed that this structural modification was absent in LPS of waaC or waaO mutants (15, 17) as well as in ΔwaaP, ΔwaaG, and ΔwaaQ derivatives.3 Confirming our earlier results (15), it was also present in the LPS of ΔwaaR mutants, which lack the terminal Hex-Hep disaccharide, arguing that this modification should occur proximal to GlcII. Because it was also present in ΔwaaB mutants, Gal apparently was not required for GlcUA incorporation.

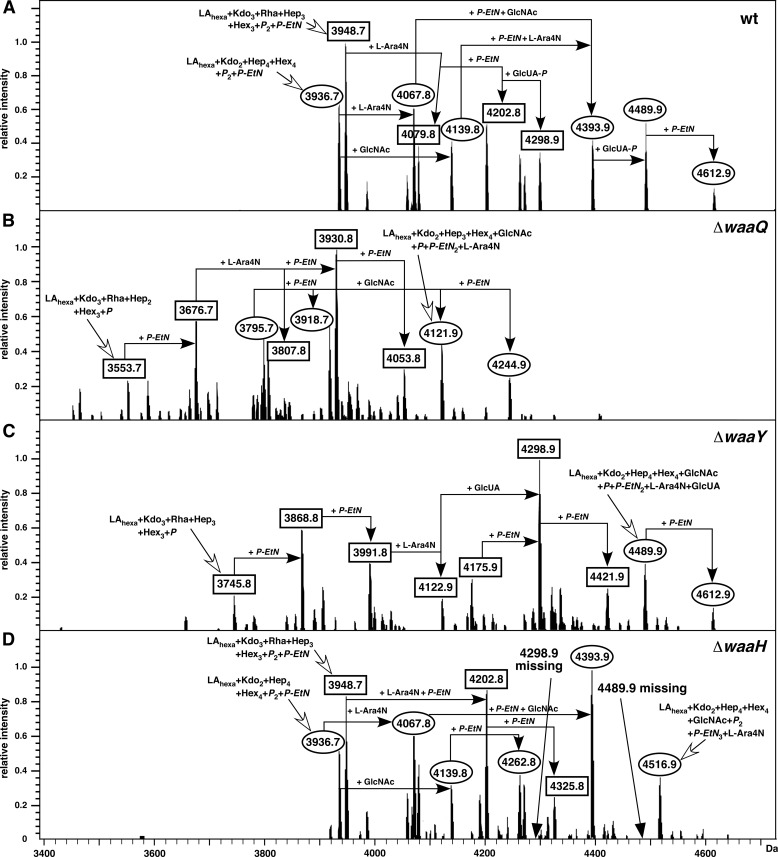

The waaQ gene encodes heptosyltransferase III, and in its absence phosphorylation of HepII is known to be lacking (12). Comparison of mass spectra of LPS obtained from ΔwaaQ and isogenic wild-type strains showed the loss of either 272 or 368 mass units from the main peaks (Fig. 3) corresponding to glycoform I or IV/V (Fig. 1). The mass change of 272 units is the result of a concomitant absence of a heptose (192 Da) and a phosphate (80 Da). Whereas WaaP-dependent HepI phosphorylation is required for the synthesis of the complete core, phosphorylation of HepII is thus dispensable for the biosynthesis of the complete core. The signals shifted to lower mass by 368 units lacked a further 96 mass units. Thus, the mass peak at 3676.7 Da and its derivatives in the LPS of ΔwaaQ mass spectra (Fig. 3B) corresponded to glycoforms, containing three Kdo and Rha but lacking HepIII and one phosphate of the wild-type LPS (3948.7 Da). Likewise, in the ΔwaaQ mutant the mass peak at 3930.8 Da arises from the wild-type structure with 4298.9 Da (LAhexa + Kdo3 + Rha + Hep3 + Hex3 + P + P-EtN2 + Ara4N + GlcUA) by the loss of 368 Da (lacking HepIII and GlcUA). Both of them represent derivatives of glycoform V. Other mass peaks in the LPS of ΔwaaQ mutants correspond to glycoform I derivatives lacking either 272 or 368 Da and are represented, for example, by molecules of 3795.7 Da and 4244.9 Da in mass, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

WaaH is required for the incorporation of the glucuronic acid. Charge-deconvoluted ESI FT-MS spectrum in negative ion mode of LPS obtained from the wild-type (A) and isogenic ΔwaaQ (B), ΔwaaY (C), and ΔwaaH (D) strains. LPS was extracted from cultures grown at 37 °C in the phosphate-limiting medium. The mass numbers refer to monoisotopic peaks. The predicted composition with varying numbers of substitutions of P-EtN and with Ara4N substitution is indicated. Mass peaks corresponding to the glycoform containing the third Kdo are marked as rectangular boxes and glycoform I with complete core derivatives as circles. Glycoforms VI and VII containing GlcUA are marked as GlcUA-P except in the case of ΔwaaY (C). Note that the mass peaks representing glycoforms corresponding to the presence of the GlcUA (4298.9 and 4489.9 Da) are absent in the LPS of ΔwaaY (D).

Lack of WaaY Enhances the GlcUA Addition

Because in the absence of WaaQ HepII is not phosphorylated, the role of phosphorylation of HepII for the modification by GlcUA was examined. Thus, LPS from the isogenic derivative carrying a nonpolar deletion in the waaY gene was analyzed. WaaY is the predicted kinase responsible for HepII phosphorylation based on previous mutant analysis in strains synthesizing R1 and R3 LPS core types (12). Interestingly, LPS from ΔwaaY revealed relatively more prominent peaks corresponding to incorporation of GlcUA (Fig. 3C). Examination of mass peaks from LPS of several isogenic E. coli K12 or E. coli B derivatives revealed that the GlcUA addition was always associated with concomitant loss of one phosphate residue. These results argue that GlcUA addition to the side-chain HepIII is incompatible with the presence of phosphate on HepII. This explains the preponderance of mass peaks containing GlcUA in ΔwaaY mutants of E. coli K12 (Fig. 3C). Because among the tested mutants LPS of the ΔwaaY derivative shows predominant presence of GlcUA at the expense of the phosphate residue on HepII, we analyzed if global RpoE-dependent envelope stress response was also induced. Measurement of RpoE-dependent promoter activity revealed that ΔwaaY mutants do not have significant alterations in envelope stress response (supplemental Fig. S4). Thus, the enhanced GlcUA incorporation in a ΔwaaY mutant is due to the presence of a nonphosphorylated acceptor for this modification.

Identification of the Regulatory Gene Responsible for the GlcUA Addition

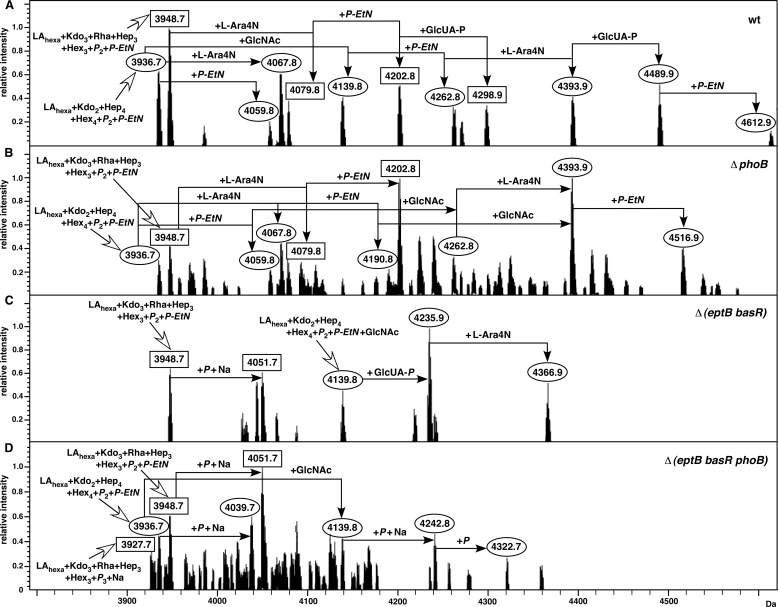

As GlcUA-containing glycoforms were uniquely observed in LPS obtained from bacteria grown in phosphate-limiting growth conditions, it was reasonable to assume that a gene encoding such a potential glycosyltransferase could be either induced or its product activated upon PhoB/R activation. The PhoB/R two-component system was directly responsible for phosphate sensing and was strongly induced upon phosphate starvation. To confirm a direct role for the positive regulation of the putative gene encoding the GlcUA transferase, a mutational analysis of PhoB/R regulatory genes was carried out. Thus, a nonpolar deletion in the phoB gene was constructed and LPS analyzed from such a derivative. The LPS of ΔphoB was nearly identical to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A), but it did not contain GlcUA (Fig. 4B). The distribution of mass peaks corresponding to glycoforms I as well as glycoforms with three Kdo was unaffected. The mass peaks prominently missing from the spectra of ΔphoB correspond to 4298.8 Da (glycoform V) and 4489.9 and 4612.9 Da (glycoform I). All of these missing peaks are derivatives containing GlcUA. Confirming these results, LPS of all deletion derivatives of phoB such as Δ(phoB basR) and Δ(eptB basR phoB) and similar others were found to lack any mass peaks that can arise due to incorporation of GlcUA (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Requirement of the PhoB/R two-component system for the incorporation of P-EtN on the first heptose. Mass spectra of LPS obtained from phosphate-limiting growth conditions of the wild type (A), its isogenic derivatives ΔphoB (B), Δ(eptB basR) (C), and Δ(eptB basR phoB) (D) are depicted. Charge-deconvoluted ESI FT-MS spectra in negative ion mode are presented. The mass numbers refer to monoisotopic peaks with proposed composition. Unlabeled mass peaks mostly correspond to Na+ and/or with phosphate adducts. Mass peaks corresponding to glycoform containing the third Kdo are marked as rectangular boxes and glycoform I with complete core derivatives as circles.

Identification of the waaH Gene Encoding the GlcUA Transferase

Examination of published microarrays from PhoB-inducing conditions led us to study the putative ORF yibD, because its deduced amino acid sequence suggests homology to the glycosyltransferase 2 family (GT-A type). Modeling revealed similarity with members of this family like SpsA from Bacillus subtilis, a nucleotide-diphospho-sugar transferase involved in sporulation (30). YibD amino acid sequence also exhibits significant homology (up to 34% in conserved N-terminal domain) to proteins like PgaC biofilm PGA synthase (31) and WcaA protein required for colonic acid synthesis (32). Among the PhoB/R regulon members without any assigned function, the transcription of the yibD gene is strongly induced upon the activation of this two-component system (33). However, a direct in vivo regulation has not been addressed. Furthermore, its predicted promoter region does indeed contain Pho boxes (33). The ORF yibD is located outside the waa locus on the E. coli chromosome at 81.62 min between ORF yibO of unknown function and the tdh gene. The tdh gene encodes threonine 3-dehydrogenase and is transcribed as the tdh kbl operon without any known role for the LPS biosynthesis (34). The minimal coding sequence of the yibD ORF was cloned under the tight ptac promoter and under the T7 polymerase expression system. Based on the presented function (core modification due to the hexuronic acid addition), we have designated the yibD ORF as waaH. The deduced amino acid composition of this glycosyltransferase is predicted to be a polypeptide of 344 amino acid residues. Upon mild induction and cellular fractionation, followed by affinity purification, it was found to be membrane-associated. Homology searches with different databases revealed that its deduced amino acid sequence bears nearly 20% sequence identity with WabO from K. pneumoniae. WabO has been shown to be a glycosyltransferase specific for the GalA incorporation into K. pneumoniae LPS (22).

Next, nonpolar in-frame chromosomal deletion derivatives of the waaH gene were constructed. These mutations were transduced into W3110 using bacteriophage P1. Examination of the LPS obtained from ΔwaaH revealed the absence of mass peaks carrying modification by GlcUA (addition of 96 or 176.1 mass units). The notable mass peaks of 4298.9, 4489.9, and 4612.9 Da corresponding to glycoforms VI and VII, respectively, are missing in LPS of ΔwaaH (Fig. 3D). These are the same mass peaks, which are absent in the LPS of ΔphoB (Fig. 4B), but are present in the LPS from the isogenic wild type (Fig. 4A). MS/MS analysis of isolated mass peaks at 4298.9 and 4489.9 Da revealed fragmentation spectra with predicted hexuronic acid linked to the inner core heptose (data not shown). The absence of GlcUA from the LPS of ΔwaaH was confirmed by GLC-MS as opposed to its presence in the parental wild type. This defect in the ΔwaaH mutant was completely restored when the LPS was examined from the complemented strain using the cloned waaH minimal coding sequence expressed from a tightly controlled ptac promoter.

To further reinforce these results, a ΔwaaH derivative of E. coli B was constructed. The waaH gene is located at the identical chromosomal location between yibO and tdh genes in E. coli B. Analysis of LPS of E. coli B ΔwaaH mutant did not reveal any mass peaks corresponding to GlcUA modification as compared with their presence in the parental wild type (supplemental Fig. S5). Interestingly, unlike E. coli K12, the E. coli B strain BL21 (DE3) was found to have constitutively induced BasS/R and PhoB/R regulons even in LB medium. This is manifested by mass peaks representing the incorporation of Ara4N and P-EtN in the lipid A part. This can explain the occurrence of a mass peak at 3551.7 Da and further derivatives, which have predicted P-EtN and Ara4N substitutions both in the parental BL21 strain and its ΔwaaH derivatives. A mild overexpression of the cloned waaH gene (upon the addition of 0.01 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside) expressed from T7 polymerase in BL21 ΔwaaH derivative was used for LPS analysis. LPS from such a strain even without phosphate starvation revealed most prevalent mass peaks with predicted GlcUA incorporation (supplemental Fig. S5). Taken together, these results demonstrate that WaaH is required for the incorporation of GlcUA in E. coli K12 and E. coli B.

GlcUA in Other E. coli Core Types and Salmonella

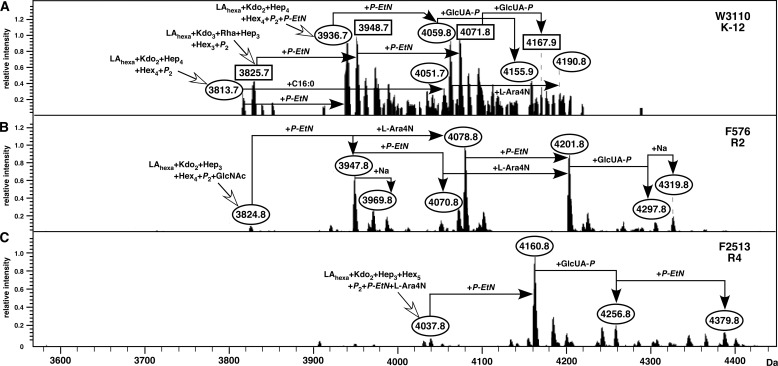

Examination of the genomic sequence representing different E. coli core types and that of Salmonella revealed that all of them contain the waaH gene. Indeed, the waaH (yibD) gene in Salmonella is part of the Pmr (BasS/R) regulon (35). However, until now no GlcUA has been reported in Salmonella or in E. coli. This can be explained by our results that induction of PhoP/Q and Pmr regulons in low Mg2+ conditions did not lead to any detectable levels of GlcUA in the LPS of Salmonella as determined by chemical and mass spectrometric analysis (data not shown). To identify conditions in which incorporation of GlcUA can be observed, we used ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO3)-supplemented growth media to grow E. coli and Salmonella derivatives. NH4VO3 is a nonspecific phosphatase inhibitor (36), which potentially induces a variety of two-component systems. Thus, LPS was obtained from the wild-type E. coli K12, representative R1, R2, R3, and R4 strains, and Salmonella minnesota R345. Among these, mass peaks indicating the incorporation of GlcUA were observed in all the cases except for the R1 and the R3 core type (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S3). These results were confirmed by a GLC-MS analysis of these LPS, which showed the presence of hexuronic acid (GlcUA) by comparison with a hyaluronic acid standard.

FIGURE 5.

Addition of ammonium metavanadate inducing the waaH transcription reveals the incorporation of GlcUA in different E. coli core types. Mass spectra of LPS were obtained from the wild-type E. coli K12 strain W3110 (A), E. coli strain F756 representing R2 core type (B), and E. coli strain F2513, representing R4 core type (C). LPS was extracted from culture grown in LB medium supplemented by 25 mm ammonium metavanadate at 37 °C and incubated with shaking for 24 h. Charge-deconvoluted ESI FT-MS spectra in negative ion mode are presented. The mass numbers refer to monoisotopic peaks with proposed composition.

Regulation of waaH and ugd Genes

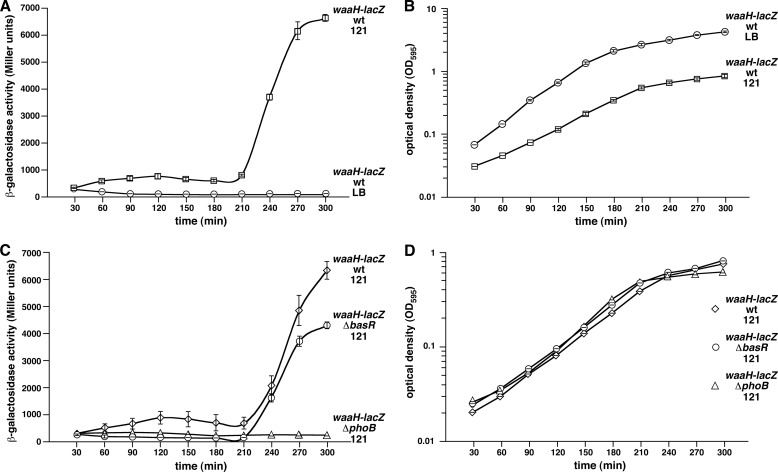

To address the molecular basis of GlcUA incorporation, the putative promoter activities of waaH and ugd genes were monitored from a chromosomal single copy (37). Transcription of the ugd gene was included because GlcUA incorporation requires conversion of UDP-glucose into UDP-glucuronic acid by the ugd gene product (2). The β-galactosidase activity driven from the waaH promoter was induced up to 200-fold upon the shift to 121 medium (Fig. 6A). This induction was abolished in a ΔphoB derivative but not in a ΔbasR background (Fig. 6C). This strong 200-fold induction was specifically observed in a growth phase-dependent manner (Fig. 6D). No induction was observed in phosphate-rich M9 or LB medium, which are noninducing conditions for PhoB/R regulon. These results strongly argue that the promoter of the waaH gene is specifically positively regulated by PhoB/R and does not require BasS/R. Because 121 medium is inducing for both BasS/R and PhoB/R regulons (17), these results assume significance and unequivocally prove that the WaaH-dependent GlcUA addition primarily requires induction of PhoB/R without any requirement for the BasS/R two-component system in E. coli K12. Thus, the presence of predicted PhoB boxes in the promoter region of the waaH gene (33) supports our results. After the completion of this work, direct PhoB-binding sites have been found upstream of the waaH (yibD) gene, although the function of the gene remained elusive (38).

FIGURE 6.

Growth phase-dependent activity of the waaH promoter in phosphate-limiting conditions (A), which requires induction of the PhoB/R two-component system (C). Cultures of E. coli wild-type strain GK1111 carrying single copy chromosomal waaH-lacZ promoter fusion or its isogenic derivative with ΔbasR or ΔphoB mutation were grown to early log phase in LB medium at 37 °C, washed, and adjusted to an A595 of 0.02 in either LB medium or phosphate-limiting 121 medium. Aliquots of samples were drawn every 30 min and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. Data corresponding to phosphate-limiting growth conditions are marked 121 in each case. The experiments were performed on four independent transductants. Error bars represent S.E. of four such cultures. B and D correspond to A595 indicating growth corresponding to different time intervals in which the β-galactosidase activity assay was performed.

The activity of the ugd promoter was also induced upon shift to phosphate-limiting growth conditions from 15- to 30-fold in a growth phase-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). Approximately 50% reduction in the basal level activity of the ugd promoter in the phosphate-limiting growth medium is observed in exponential growth phase in a ΔphoB derivative (Fig. 7C). Very low activity of the ugd promoter was observed in a ΔbasR derivative. However, a dramatic increase in the ugd-lacZ activity was observed in a ΔbasR mutant in the stationary phase but not in a ΔphoB. Thus, the transcription of the ugd promoter requires both PhoB/R and BasS/R activation. This dual mode of transcription control by these two-component systems provides precursor UDP-glucuronic acid for GlcUA and Ara4N synthesis. Because BasS/R regulates Ara4N synthesis (lipid A modifications) and PhoB/R regulates core alterations, including GlcUA transfer, the transcription of the ugd promoter is intricately balanced.

FIGURE 7.

Growth phase-dependent transcriptional activity of the promoter of the ugd gene in phosphate-limiting conditions (A), which requires the functional presence of PhoB/R and BasS/R two-component systems (C). Cultures of E. coli wild-type strain carrying single copy chromosomal ugd-lacZ promoter fusion or its isogenic derivative with ΔbasR or ΔphoB mutation were grown to early log phase in LB medium at 37 °C, washed, and adjusted to an A595 of 0.02 in either LB medium or phosphate-limiting 121 medium. Aliquots of samples were drawn every 30 min and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. Data corresponding to phosphate-limiting growth conditions are marked 121 in each case. The experiments were performed on four independent isolates. Error bars represent S.E. of four such cultures. B and D correspond to A595 indicating growth corresponding to different time intervals in which the β-galactosidase activity assay was performed.

eptC Gene Is Required for the P-EtN Addition to HepI in the Inner Core

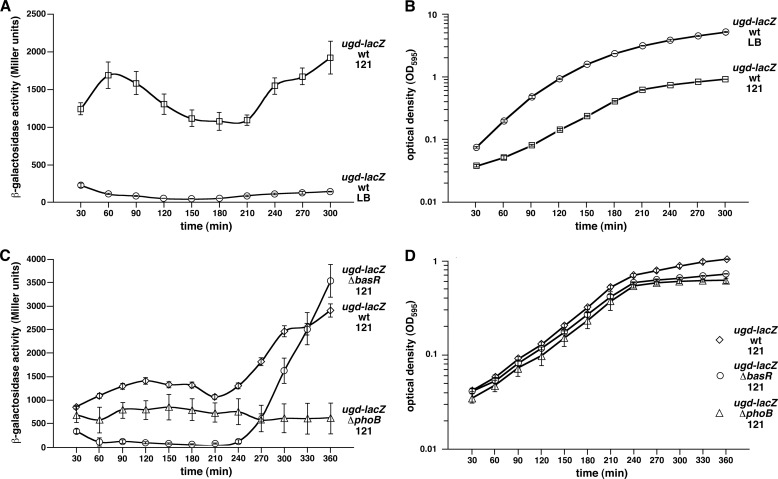

It is known that the LPS of E. coli K12 often contains nonstoichiometric substitutions by P-EtN residues. These P-EtN substitutions can occur in lipid A, on the second Kdo, as well as in the inner core on HepI. The genes whose products are responsible for the P-EtN addition to Kdo (the eptB gene) and a BasS/R-inducible modification of lipid A (the eptA gene) are known. However, the gene responsible for the P-EtN addition to HepI and its regulation is not known in E. coli. Based on mass spectrometric analysis of LPS obtained from several isogenic strains in phosphate-limiting growth conditions, we could observe mass peaks with a predicted presence of all three P-EtN residues. E. coli contains three additional orthologs of EptA and EptB. These three orthologs are encoded by ORFs designated as ybiP, yhjX, and yijP. Deletion derivatives of these three individual ORFs were constructed and combined with deletion mutation of either the eptA gene alone or the eptB gene alone, or their combinations. Among the three deletion derivatives of these ORFs, LPS of ΔyijP alone resulted in the absence of mass peaks with three P-EtN residues (4612.9 Da) (Fig. 8B). Thus, this gene was designated as the eptC gene. Furthermore, accumulation of mass peaks at 3813.7 and 3825.7 Da corresponding to glycoforms I and IV, respectively, were only observed in the LPS of strains lacking either the eptA or eptB or eptC gene (Fig. 8). However, these mass peaks are absent in the spectra of the wild type (Fig. 8A). These mass peaks, as indicated, lack any substitution of predicted P-EtN addition even in conditions in which the wild type can incorporate all three P-EtN residues.

FIGURE 8.

Incorporation of P-EtN on HepI requires the functional presence of the eptC gene. Mass spectra of LPS obtained from the wild-type strain W3110 (A) and its isogenic derivatives lacking eptC (B), Δ(eptA eptC) (C), and Δ(eptA eptB eptC) (D) are depicted. Cultures were grown at 37 °C in phosphate-limiting medium, and LPS was extracted under identical conditions. Charge-deconvoluted ESI FT-MS spectra in the negative ion mode are presented. The mass numbers refer to monoisotopic peaks with proposed composition.

Next, we analyzed by mass spectrometry the LPS of strains carrying combinations of null mutations in various ept genes and disruptions of the other two ORFs. Again, no differences in mass spectra were observed when ΔybiP or ΔyhjX was introduced into Δept strains (data not shown). However, strains carrying either Δ(eptA eptC) or Δ(eptB eptC) or Δ(eptA eptB) combinations revealed incorporation of only one P-EtN substitution. Data presented here correspond to Δ(eptA eptC) (Fig. 8C). The main striking difference between mass spectra of LPS obtained from ΔeptC and Δ(eptA eptC) mutants is the predicted composition of Δ(eptA eptC) LPS, which contains only one P-EtN substitution, as compared up to two P-EtN substitutions in ΔeptC LPS. This explains the absence of a mass peak at 4489.9 Da in Δ(eptA eptC), which is present in either ΔeptC or the wild type (Fig. 8). These results further show that the eptC gene product is required for the P-EtN incorporation. Consistent with these results, LPS of Δ(eptA eptB eptC) strain did not reveal any mass peaks with a predicted incorporation of P-EtN (Fig. 8D). It should be noted that the LPS obtained from the Δ(eptA eptB eptC) strain lacking all three ept genes reveals mass peaks indicative of an incorporation of Ara4N and GlcUA (Fig. 8D). Thus, in the absence of P-EtN transferases other nonstoichiometric modifications do not seem to be influenced to any significant levels. Thus, LPS of ΔeptC did not exhibit any other major differences either in the accumulation of different glycoforms or the lipid A composition. Hence, EptC function seems to be specific for P-EtN incorporation on phosphorylated HepI, given the known function of the two other P-EtN transferases. Furthermore, unlike EptB, which is required for P-EtN addition to the second Kdo and regulates the shift of Rha to the third Kdo and hence the presence of glycoform V, no such differences in the LPS were observed in ΔeptC.

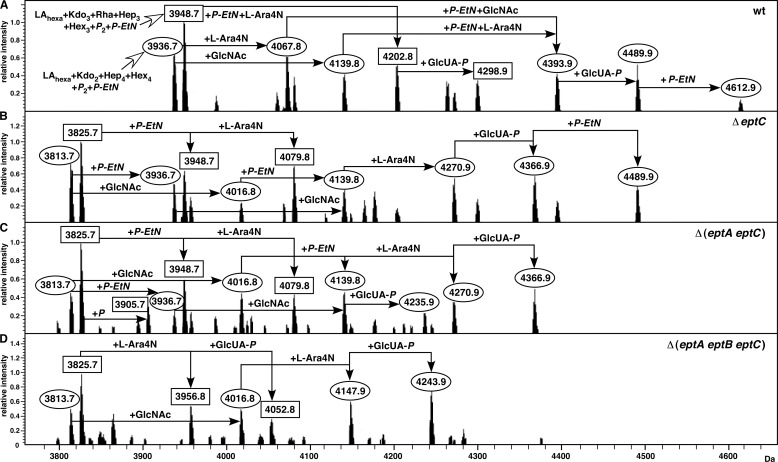

Regulation of the eptC Gene

As shown previously, LPS obtained from phosphate-rich M9 growth conditions lack any P-EtN modifications (15). However, mass peaks with up to three predicted P-EtN substitutions seemed to be enriched in the LPS obtained from phosphate-limiting medium. Growth in this medium can induce both BasS/R and PhoB/R two-component systems. Examination of mass spectra of LPS of ΔphoB revealed incorporation of up to three P-EtN residues indicating that activity/expression of none of the three phosphoethanolamine transferases is abolished (Fig. 4B). This is evident from the presence of the mass peak at 4516.9 Da in the spectra of LPS obtained from the ΔphoB mutant strain. Thus, we addressed the relative role of PhoB/R and BasS/R regulatory systems in the P-EtN addition to HepI. It is known that the transcription of the eptA gene requires BasS/R induction. Thus, ΔbasR mutants lack P-EtN in lipid A (17). Similarly, EptB is required for the P-EtN addition to the second Kdo (14). Thus, a Δ(eptB basR) strain should depict activity of the eptC gene independent of the BasS/R two-component system. As can be seen, most of the assigned mass peaks of LPS obtained under PhoB/R-inducible conditions from the Δ(eptB basR) strain contain one P-EtN (Fig. 4C). This is evident from the predicted composition of main mass peaks at 3948.7 and 4139.8 Da and their derivatives (Fig. 4). These results suggest that induction of PhoB/R must play a major role in the transcriptional activation of the eptC gene. Furthermore, the BasS/R induction does not seem to contribute significantly to the transcription of the eptC gene based on the observed P-EtN modification of phosphorylated HepI in ΔbasR.

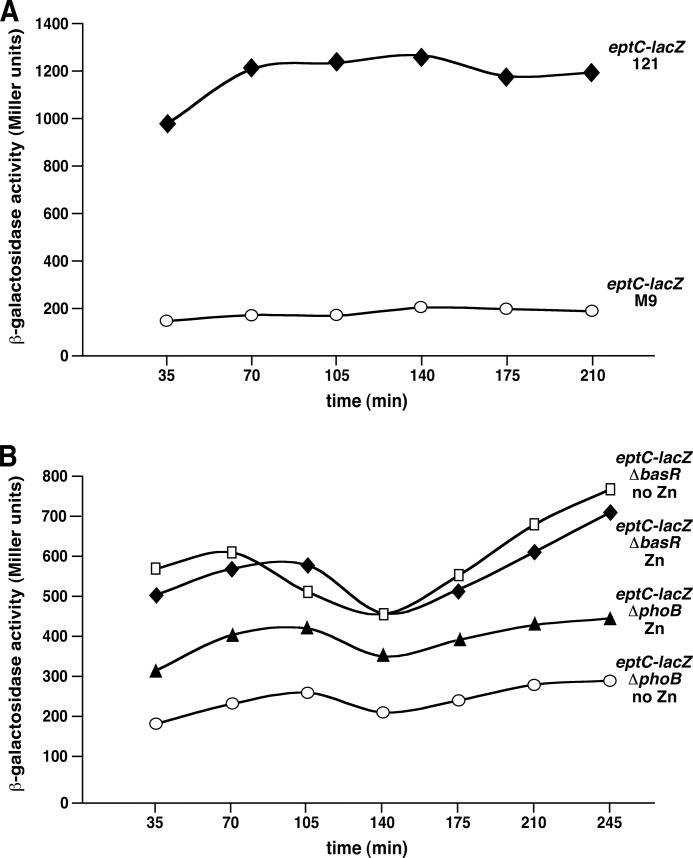

To further investigate the regulation of the eptC gene, a single copy chromosomal eptC-lacZ transcriptional fusion was constructed. Thus, we analyzed in parallel the eptC-lacZ promoter fusion activity in phosphate-rich (M9) versus phosphate-limiting (121) growth conditions at different intervals of growth. As can be seen, β-galactosidase activity was about 6-fold higher in the phosphate-limiting medium (Fig. 9A). Next, we analyzed relative eptC promoter activity in isogenic ΔphoB and ΔbasR mutants in phosphate-limiting growth conditions. Because the 121 medium is supplemented with 10 μm Zn2+ and eptC mutants are sensitive to Zn2+, β-galactosidase assays were performed in the absence or in the presence of Zn2+. It needs to be mentioned that with the supplementation of 10 μm Zn2+, no growth differences were observed between the wild type and the eptC mutant. Introduction of a ΔphoB mutation led to a dramatic decrease in the eptC-lacZ promoter fusion activity (Fig. 9B). This is more pronounced when Zn2+ was omitted. However, eptC-lacZ activity was only reduced 2-fold in ΔbasR mutants as compared with a 4–5-fold reduction in ΔphoB derivatives. Furthermore, the presence or the absence of Zn2+ in a ΔbasR background did not significantly reduce the eptC-lacZ promoter fusion activity. These data are consistent with the data from LPS analysis that the major positive regulator of the eptC transcription is PhoB-dependent. As the activity of the eptC-lacZ transcriptional fusion was not totally abolished in ΔphoB mutants, it suggests that a constitutive basal transcriptional activity is present, which is independent of both PhoB and BasR. These results are supported by the presence of few mass peaks with the predicted P-EtN incorporation in a strain derivative Δ(eptB phoB basR). Interestingly, these results also show that the induction of the eptC gene of E. coli K12 does not require the BasS/R induction.

FIGURE 9.

Induction of transcription of the eptC promoter requires induction of the PhoB/R two-component system and the presence of Zn2+. Cultures of E. coli wild-type strain GK1111 carrying single copy chromosomal eptC-lacZ promoter fusion or its isogenic derivative with ΔbasR or ΔphoB mutations were grown to early log phase in LB medium at 37 °C, washed, and adjusted to an A595 of 0.02 in either M9 or phosphate-limiting 121 medium. Aliquots of samples were drawn at 35-min intervals and analyzed for the β-galactosidase activity. Data corresponding to phosphate-limiting growth conditions are marked 121 and phosphate-rich as M9 (A). The experiments were performed on four independent isolates. B, data with and without supplementation by Zn2+ in the phosphate-limiting 121 medium are presented.

EptC Is Required for the Outer Membrane Function

Because the main function of the LPS is to provide the permeability barrier function, the potential role of LPS modification by nonstoichiometric substitution of LPS with P-EtN was addressed. Thus, a panel of isogenic strains carrying either the deletion of individual ept genes or their combinations was examined for different growth defects related to the membrane permeability. Thus, bacteria were challenged with SDS under phosphate-limiting growth conditions that promote the incorporation of P-EtN residues into the LPS core and lipid A. As shown, ΔeptC mutant bacteria exhibited a severe growth defect in the presence of low concentrations of SDS (0.25%) with a reduction of the colony forming ability by 103 (Table 4). At this concentration, the wild type and its isogenic derivatives ΔeptB or ΔeptA showed no growth defects. At higher concentrations of SDS (1%), the colony forming ability was reduced by 105 in ΔeptC mutants, although no significant effect on the viability of wild-type or that of other ept mutants was observed (Table 4). This SDS-sensitive phenotype was not observed in the phosphate-rich medium, consistent with induction of the eptC gene expression primarily in phosphate-limiting growth conditions.

TABLE 4.

EptC is required for OM stability

Colony forming ability in the phosphate-limiting 121 medium at different concentrations of SDS or in the presence of 150 μm Zn2+. Cultures were adjusted to an A595 of 0.1, and viability was measured after plating 10-fold serial dilutions on agar plates containing 121 medium. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h.

| Strain | 0.25% SDS | 0.5% SDS | 1% SDS | 150 μm Zn2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 3 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 2 × 107 | 3 × 107 |

| ΔeptA | 2 × 107 | 2 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 2 × 107 |

| ΔeptB | 2 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 2 × 107 | 3 × 107 |

| ΔeptC | 2 × 104 | 7 × 103 | 3 × 102 | 3 × 102 |

| Δ(eptB eptC) | 6 × 106 | 2 × 106 | 5 × 106 | 2 × 106 |

| ΔeptC + vector | 2 × 104 | 6 × 103 | 5 × 102 | 60 |

| ΔeptC + peptC+ | 3 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 3 × 107 | 3 × 107 |

Because the expression of the eptC gene is enhanced in the presence of Zn2+, we also tested if EptC is required for the tolerance to its increased concentrations. Although wild-type bacteria can support growth up to a concentration of 200 μm Zn2+, growth of the ΔeptC mutant was highly attenuated even at 150 μm Zn2+. Again, just like in the case of sensitivity to SDS, ΔeptC mutants alone were sensitive to Zn2+, but not the ΔeptB or ΔeptA mutant bacteria. Interestingly, introduction of the ΔeptB mutation suppressed this Zn2+-sensitive phenotype (Table 4). Such a suppression was not observed in Δ(eptA eptC) combination. However, this restoration/suppression by ΔeptB seems to be limited to Zn2+ and SDS-sensitive growth defects only. As shown in LPS compositional analysis, introduction of the ΔeptB mutation does not cause any new P-EtN addition in the LPS as seen by the total absence of any mass peaks with predicted P-EtN in Δ(eptA eptB eptC) mutants.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we analyzed the genetic and structural basis of inner core nonstoichiometric alterations in the LPS of E. coli. The incorporation of βGlcUA (glucuronic acid) as a novel modification of HepIII is shown here for the first time. Furthermore, a new gene, designated waaH, whose product is responsible for the βGlcUA incorporation into the LPS was identified. In parallel experiments, the modification of phosphorylated HepI by P-EtN and its physiological significance was studied. The responsible P-EtN transferase was identified and according to its function designated EptC.

The definitive assignment of GlcUA was based on the structural analysis of a purified oligosaccharide from an E. coli B strain. In GLC-MS, the fragmentation pattern and the retention time of the derivatized hexuronic acid was identical to a standard GlcUA obtained from hyaluronic acid. The NMR analysis showed that the βGlcUA was attached to O-7 of the side-chain Hep. Furthermore, the phosphate residue commonly found at position O-4 of the middle Hep was absent.

To understand structural and regulatory basis of the GlcUA incorporation, LPS was analyzed from strains carrying nonpolar deletions in genes comprising the waa locus and its regulatory systems. These studies revealed that GlcUA is specifically incorporated in phosphate-limiting growth conditions into the LPS of E. coli K12 derivatives, which requires the presence of HepII. This incorporation requires activation of the PhoB/R two-component system without any requirement for BasS/R induction. The minimal in vivo LPS structure supporting the GlcUA incorporation requires the presence of a core oligosaccharide up to GlcII of the outer core. Furthermore, the absence of terminal HepIV-HexIII disaccharide due to a waaR mutation or even a waaB mutant lacking Gal was found to contain GlcUA.

The gene encoding putative glycosyltransferase for the GlcUA incorporation was identified outside the waa locus. Nonpolar deletion derivatives were constructed in E. coli K12 as well as E. coli B. Analysis of LPS of such mutants revealed a unique lack of GlcUA without any other structural alterations. Thus, the gene was designated as waaH. Hence, the waaH gene is not a regulatory gene for GlcUA incorporation but is a structural gene.

A strong induction of the waaH transcription was observed upon entry in the stationary phase in PhoB-inducing conditions. The growth phase and PhoB-dependent transcriptional regulation of the waaH gene draw an interesting parallel with the observed induction of the promoter activity of the ugd gene in stationary phase. The ugd gene encodes UDP-glucose dehydrogenase that converts UDP-glucose into UDP-glucuronic acid. The transcriptional regulation of the ugd gene has been mainly examined in Salmonella, wherein it is regulated by PhoP/Q, Pmr, and Rcs two-component systems (39). In E. coli, transcription of ugd and waaH genes seems to respond to similar signals but with interesting differences. Because UDP-glucuronic acid serves as precursor for GlcUA as well as Ara4N synthesis, the transcription of the ugd gene in E. coli K12 was found to be controlled by two overlapping two-component systems (PhoB/R and BasS/R), which control GlcUA and lipid A modifications, respectively. The transcription induction in the late stationary phase of both ugd as well as waaH genes requires PhoB/R induction but not BasS/R. However, the transcription of the ugd gene does not require PhoB/R in exponential growth phase but requires BasS/R. Because ΔrpoS mutants contain GlcUA substitutions in the LPS (15), the growth phase-dependent waaH and ugd regulation is not RpoS-dependent.

We observed that the addition of the nonspecific phosphatase inhibitor NH4VO3 to phosphate-rich LB medium also induces the LPS modification by GlcUA substitution. The GlcUA addition upon such treatment can also be ascribed to PhoB/R-dependent transcriptional induction of the waaH gene. Previously, it has been shown that NH4VO3 induces BasS/R-dependent lipid A modification as well as the RpoE-dependent envelope stress-response regulon (36, 40). Addition of NH4VO3 is also known to induce the transcription of the waaH gene (41). However, in that work the authors did not study the effects of PhoB/R induction (41). Because we previously observed the presence of mass peaks with GlcUA-modified structures in both ΔbasR as well as ΔrpoE mutants (15), we can conclude that this modification is PhoB/R-dependent.

Thus, using growth medium supplemented with NH4VO3, GlcUA was also found to be present in the LPS preparations of Salmonella as well as E. coli R2 and R4 core types. Intriguingly, using NH4VO3-supplemented growth medium, no detectable GlcUA was observed in the LPS of R1 and R3 core types. It is possible that under such conditions GlcN incorporation on HepIII in R1 and R3 core types is the preferred modification and may preclude GlcUA incorporation. Consistent with such an idea, GlcN incorporation in R3 core type is present in derivatives even with only GlcI in the outer core as shown in the case of E. coli J-5 structure (10).

Although we did not observe GlcUA incorporation in the R3 core type, the waaH gene was also identified in the signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis approach as one of the candidates required for the colonization by E. coli O157:H7 (42). In that study, transposon mutants that were impaired in their ability to colonize host were sought. It is likely that the waaH gene in such cases might be regulated in a different manner than in the case of E. coli K12. At present, no comparative knowledge about regulation of the wabB gene responsible for GlcN addition in the R3 core type vis à vis the waaH gene is available. The plasmid-encoded wabB gene is co-transcribed as the shf-wabB-virK-msbB operon. However, the wabB gene seems to be thermoregulated (43). Until now, the physiological significance of WabB-mediated GlcN incorporation is not known. As waaQ and waaH genes are present in all the E. coli core types and in several Enterobacteriaceae members like Salmonella and Shigella, we speculated that GlcUA-modified LPS must be present in such bacteria. It is quite likely that WaaH-dependent GlcUA incorporation has an adaptive significance under growth conditions like phosphate starvation, which can naturally occur in bacteria growing outside the host. In the case of E. coli K12, ΔwaaH mutants were found to be more sensitive to Fe3+, in backgrounds like arnT mutants.3 It is interesting because both GlcUA and Ara4N syntheses require Ugd-dependent UDP-glucuronic acid synthesis (2, 39).

In this work, it was also observed that the presence of GlcUA is always associated with a lack of phosphate at HepII. This is reminiscent of the situation in the LPS of R1 and R3 core types, wherein nonstoichiometric incorporation of GlcN on HepIII is accompanied by the absence of O-4 phosphate of HepII (6). As presented in this work and consistent with earlier results (12), phosphorylation of HepII requires prior WaaQ-mediated incorporation of HepIII. It is likely that the incorporation of GlcUA precludes WaaY-mediated phosphorylation of HepII or that the presence of a negatively charged GlcUA is incompatible with the presence of an additional negative charge at HepII. Furthermore, it seems that nonphosphorylated HepII LPS is a better substrate for the GlcUA incorporation in vivo, because this modification was highly preferred in waaY mutants. This incorporation of GlcUA at the expense of phosphate could be both structural as well as a compensatory mechanism to regain negative charge by the addition of this acidic sugar. Thus, WaaH-mediated GlcUA substitution precluding HepII phosphorylation can be explained on the basis of substrate preference on lines similar to that proposed for GlcN incorporation by WabB on HepIII in E. coli R3 core type (9).

It seems that HepIII in E. coli can accept various substitutions at the expense of phosphate on HepII depending upon the LPS core type. This substitution can be GlcN, GlcNAc, and GlcUA. In K. pneumoniae, which lacks any phosphates in the core region, HepIII can be substituted by GalA (22). Taken together, in all cases such substitutions by uronic acid is suggested to contribute to retaining net negative charges (2). WaaH shares 20% amino acid sequence similarity with WabO of K. pneumonia, which is responsible for GalA incorporation (22). However, expression of the wabO gene in E. coli K12 or E. coli B strains neither complemented E. coli waaH mutants nor caused any LPS modification.

The biosynthesis of the inner core of LPS, including the phosphorylation of HepI and addition of P-EtN, is critical for the outer membrane permeability. Although the role of WaaP has been addressed, the gene encoding the P-EtN transferase has not been described in E. coli. Phosphorylation of the HepI residue requires WaaP kinase and is also the site of attachment for the third P-EtN in E. coli. In E. coli, the genes encoding P-EtN transferases for the modification of lipid A (eptA) and the second Kdo (eptB) have been identified. The E. coli genome contains three additional distinct ORFs without any demonstrated function, whose deduced amino acid sequence exhibits homology to EptA and EptB. In this work, we showed that the gene encoded by ORF yijP is responsible for the P-EtN transfer to phosphorylated HepI. We designated this gene as the eptC gene. Mass spectrometric analysis of LPS obtained from ΔeptC showed nonstoichiometric incorporation of P-EtN in lipid A, and only the core-specific P-EtN substitution was missing. Furthermore, MS/MS analysis of isolated mass peaks from Δ(eptA eptC) with a predicted P-EtN substitution unequivocally showed that P-EtN was only present on Kdo. The modification of Kdo by P-EtN is solely dependent on EptB, and hence, we can assume that EptC function is dedicated to the modification of P-EtN on HepI. Consistent with such arguments, any mass peaks indicative of such a modification were absent in the spectra of LPS from a Δ(eptA eptB eptC) strain. These results suggest that two other homologs, YbhX and YbiP, may have some other unidentified non-LPS substrate for the incorporation of P-EtN.

We also found that among ept mutants, only an eptC mutant exhibited sensitivity to the mild addition of detergents like SDS or sublethal concentrations of Zn2+ in the phosphate-limiting medium. Sensitivity to SDS suggested that the P-EtN addition to the phosphorylated HepI is critical for the outer membrane stability. Thus, the EptC-dependent modification seems to be critical for the permeability function and challenges to sublethal concentrations of Zn2+.

Examination of the transcriptional regulation of the eptC gene revealed that it is expressed at the basal level in complex-rich medium like LB medium. However, the transcription of the eptC promoter is induced upon shift to the phosphate-limiting medium supplemented by micromolar concentrations of nontoxic Fe3+ and Zn2+ salts. This induction was PhoB/R-dependent and did not require the BasS/R activation. Consistent with these results, putative PhoB boxes were found in the promoter region. These boxes are located at −176 and −96, respectively, upstream of the eptC gene (CTCTTCTGCAAACCCTCGTGCTTTTGCG and CTGTCTGCATTTTATTCAAATTCTGAATA). The observed positive regulation of the eptC gene in E. coli K12 by the PhoB/R two-component system is interesting, because the corresponding modification in Salmonella is Pmr-dependent (18). This induction of EptC is important for bacterial viability under specific growth conditions such as phosphate starvation and upon challenge with agents that disrupt OM permeability.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of V. Susott, U. Agge, and B. Kunz, and we thank H. Moll for GLC-MS analyses. S. R. thanks members of his laboratory for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by National Science Centre Grant 2011/03/B/NZ1/02825 (to S. R.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

G. Klein, B. Lindner, N. Kobylak, and S. Raina, unpublished results.

- OM

- outer membrane

- GlcUA

- glucuronic acid

- Kdo

- 3-deoxy-α-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid

- P-EtN

- phosphoethanolamine

- l-Ara4N

- 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose

- Hep

- l-glycero-α-d-manno-heptopyranose

- Rha

- rhamnose

- GLC-MS

- gas-liquid chromatography-MS

- HPAEC

- high performance anion exchange chromatography

- Hex

- hexose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nikaido H. (2003) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 593–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raetz C. R., Whitfield C. (2002) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gronow S., Xia G., Brade H. (2010) Glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of the inner core region of different lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89, 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amor K., Heinrichs D. E., Frirdich E., Ziebell K., Johnson R. P., Whitfield C. (2000) Distribution of core oligosaccharide types in lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68, 1116–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vinogradov E. V., Van Der Drift K., Thomas-Oates J. E., Meshkov S., Brade H., Holst O. (1999) The structures of the carbohydrate backbones of the lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli rough mutants F470 (R1 core type) and F576 (R2 core type). Eur. J. Biochem. 261, 629–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Müller-Loennies S., Lindner B., Brade H. (2002) Structural analysis of deacylated lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli strains 2513 (R4 core-type) and F653 (R3 core-type). Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5982–5991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Currie C. G., Poxton I. R. (1999) The lipopolysaccharide core type of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other non-O157 verotoxin-producing E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 24, 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frirdich E., Whitfield C. (2005) Lipopolysaccharide inner core oligosaccharide structure and outer membrane stability in human pathogens belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae. J. Endotoxin Res. 11, 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaniuk N. A., Vinogradov E., Li J., Monteiro M. A., Whitfield C. (2004) Chromosomal and plasmid-encoded enzymes are required for assembly of the R3-type core oligosaccharide in the lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31237–31250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Müller-Loennies S., Holst O., Lindner B., Brade H. (1999) Isolation and structural analysis of phosphorylated oligosaccharides obtained from Escherichia coli J-5 lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 260, 235–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murata M., Fujimoto H., Nishimura K., Charoensuk K., Nagamitsu H., Raina S., Kosaka T., Oshima T., Ogasawara N., Yamada M. (2011) Molecular strategy for survival at a critical high temperature in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 6, e20063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yethon J. A., Heinrichs D. E., Monteiro M. A., Perry M. B., Whitfield C. (1998) Involvement of waaY, waaQ, and waaP in the modification of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide and their role in the formation of a stable outer membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26310–26316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raetz C. R., Reynolds C. M., Trent M. S., Bishop R. E. (2007) Lipid A modification systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 295–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reynolds C. M., Kalb S. R., Cotter R. J., Raetz C. R. (2005) A phosphoethanolamine transferase specific for the outer 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid residue of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Identification of the eptB gene and Ca2+ hypersensitivity of an eptB deletion mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21202–21211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klein G., Lindner B., Brade H., Raina S. (2011) Molecular basis of lipopolysaccharide heterogeneity in Escherichia coli: envelope stress-responsive regulators control the incorporation of glycoforms with a third 3-deoxy-α-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid and rhamnose. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42787–42807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moon K., Gottesman S. (2009) A PhoQ/P-regulated small RNA regulates sensitivity of Escherichia coli to antimicrobial peptides. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 1314–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klein G., Lindner B., Brabetz W., Brade H., Raina S. (2009) Escherichia coli K12 suppressor-free mutants lacking early glycosyltransferases and late acyltransferases: minimal lipopolysaccharide structure and induction of envelope stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15369–15389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamayo R., Choudhury B., Septer A., Merighi M., Carlson R., Gunn J. S. (2005) Identification of cptA, a PmrA-regulated locus required for phosphoethanolamine modification of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide core. J. Bacteriol. 187, 3391–3399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20. Torriani A. (1960) Influence of inorganic phosphate in the formation of phosphatases by Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 38, 460–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fresno S., Jiménez N., Canals R., Merino S., Corsaro M. M., Lanzetta R., Parrilli M., Pieretti G., Regué M., Tomás J. M. (2007) A second galacturonic acid transferase is required for core lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis and complete capsule association with the cell surface in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1128–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raina S., Missiakas D., Georgopoulos C. (1995) The rpoE gene encoding the σE(σ24) heat shock σ factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14, 1043–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simons R. W., Houman F., Kleckner N. (1987) Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusion. Gene 53, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dartigalongue C., Missiakas D., Raina S. (2001) Characterization of the Escherichia coli σE regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20866–20875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galanos C., Lüderitz O., Westphal O. (1969) A new method for the extraction of R lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 9, 245–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kondakova A., Lindner B. (2005) Structural characterization of complex bacterial glycolipids by Fourier-transform mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 11, 535–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gronow S., Lindner B., Brade H., Müller-Loennies S. (2009) Kdo-(2→8)-Kdo-(2→4)-Kdo but not Kdo-(2→4)-Kdo-(2→4)-Kdo is an acceptor for transfer of l-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose by Escherichia coli heptosyltransferase I (WaaC). Innate Immun. 15, 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bock K., Thomsen J. U., Kosma P., Christian R., Holst O., Brade H. (1992) A nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic investigation of Kdo-containing oligosaccharides related to the genus-specific epitope of Chlamydia lipopolysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 229, 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tarbouriech N., Charnock S. J., Davies G. J. (2001) Three-dimensional structures of the Mn and Mg dTDP complexes of the family GT-2 glycosyltransferase SpsA: a comparison with related NDP-sugar glycosyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 655–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steiner S., Lori C., Boehm A., Jenal U. (2013) Allosteric activation of exopolysaccharide synthesis through cyclic di-GMP-stimulated protein-protein interaction. EMBO J. 32, 354–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hagiwara D., Sugiura M., Oshima T., Mori H., Aiba H., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. (2003) Genome-wide analyses revealing a signaling network of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5735–5746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baek J. H., Lee S. Y. (2006) Novel gene members in the Pho regulon of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264, 104–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aronson B. D., Somerville R. L., Epperly B. R., Dekker E. E. (1989) The primary structure of Escherichia coli l-threonine dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 5226–5232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamayo R., Ryan S. S., McCoy A. J., Gunn J. S. (2002) Identification and genetic characterization of PmrA-regulated genes and genes involved in polymyxin B resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 70, 6770–6778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou Z., Lin S., Cotter R. J., Raetz C. R. (1999) Lipid A modifications characteristic of Salmonella typhimurium are induced by NH4VO3 in Escherichia coli K12. Detection of 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine, and palmitate. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18503–18514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raina S., Mabey L., Georgopoulos C. (1991) The Escherichia coli htrP gene product is essential for bacterial growth at high temperatures: mapping, cloning, sequencing, and transcriptional regulation of htrP. J. Bacteriol. 173, 5999–6008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoshida Y., Sugiyama S., Oyamada T., Yokoyama K., Kim S.-K., Makino K. (2011) Identification of PhoB binding sites of the yibD and ytfK promoter regions in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. 49, 285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mouslim C., Groisman E. A. (2003) Control of the Salmonella ugd gene by three two-component regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tam C., Missiakas D. (2005) Changes in lipopolysaccharide structure induce the σE-dependent response of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1403–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Froelich J. M., Tran K., Wall D. (2006) A pmrA constitutive mutant sensitizes Escherichia coli to deoxycholic acid. J. Bacteriol. 188, 1180–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dziva F., van Diemen P. M., Stevens M. P., Smith A. J., Wallis T. S. (2004) Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 150, 3631–3645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoon J. W., Minnich S. A., Ahn J. S., Park Y. H., Paszczynski A., Hovde C. J. (2004) Thermoregulation of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 pO157 ecf operon and lipid A myristoyl transferase activity involves intrinsically curved DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 419–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmidt G., Jann B., Jann K. (1969) Immunochemistry of R lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia coli. Different core regions in the lipopolysaccharides of O group 8. Eur. J. Biochem. 10, 501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmidt G., Fromme I., Mayer H. (1970) Immunochemical studies on core lipopolysaccharides of Enterobacteriaceae of different genera. Eur. J. Biochem. 14, 357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schmidt G., Jann B., Jann K. (1974) Genetic and immunochemical studies on Escherichia coli O14:K7:H−. Eur. J. Biochem. 42, 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lüderitz O., Galanos C., Risse H. J., Ruschmann E., Schlecht S., Schmidt G., Schulte-Holthausen H., Wheat R., Westphal O., Schlosshardt J. (1966) Structural relationships of Salmonella O and R antigens. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 133, 349–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kitagawa M., Ara T., Arifuzzaman M., Ioka-Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., Toyonaga H., Mori H. (2005) Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]