Background: VEGF-D is a secreted protein that promotes cancer metastasis; it comprises a receptor-binding domain flanked by cleavable propeptides but the functions of the propeptides were unclear.

Results: Propeptides determine heparin binding, VEGF receptor heterodimerization, and rates of metastasis.

Conclusion: Propeptides influence molecular interactions of VEGF-D and its bioactivity in cancer.

Significance: This study defines the biological significance of VEGF-D propeptides.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Cancer, Heparin, Lymphangiogenesis, Metastasis, VEGF-D, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, Propeptides, Receptor Heterodimers

Abstract

VEGF-D is an angiogenic and lymphangiogenic glycoprotein that can be proteolytically processed generating various forms differing in subunit composition due to the presence or absence of N- and C-terminal propeptides. These propeptides flank the central VEGF homology domain, that contains the binding sites for VEGF receptors (VEGFRs), but their biological functions were unclear. Characterization of propeptide function will be important to clarify which forms of VEGF-D are biologically active and therefore clinically relevant. Here we use VEGF-D mutants deficient in either propeptide, and in the capacity to process the remaining propeptide, to monitor the functions of these domains. We report for the first time that VEGF-D binds heparin, and that the C-terminal propeptide significantly enhances this interaction (removal of this propeptide from full-length VEGF-D completely prevents heparin binding). We also show that removal of either the N- or C-terminal propeptide is required for VEGF-D to drive formation of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers which have recently been shown to positively regulate angiogenic sprouting. The mature form of VEGF-D, lacking both propeptides, can also promote formation of these receptor heterodimers. In a mouse tumor model, removal of only the C-terminal propeptide from full-length VEGF-D was sufficient to enhance angiogenesis and tumor growth. In contrast, removal of both propeptides is required for high rates of lymph node metastasis. The findings reported here show that the propeptides profoundly influence molecular interactions of VEGF-D with VEGF receptors, co-receptors, and heparin, and its effects on tumor biology.

Introduction

Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis are key processes in embryogenesis, wound healing, and immune function, and in diseases including metastatic cancer, inflammatory disorders and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)2 (1–4). Members of the VEGF family of secreted glycoproteins promote lymphangiogenesis and/or angiogenesis by activating cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases on endothelial cells, such as VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-2 and VEGFR-3. For example, human VEGF-D activates both VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (5), and drives growth of blood vessels and lymphatics in various settings (6–12). In animal models of cancer, expression of VEGF-D promotes growth of blood vessels and small lymphatics in and around tumors, facilitating tumor growth and enhancing lymph node and distant organ metastasis (13–15). VEGF-D also promotes dilation of tumor-draining collecting lymphatics, which facilitates transport of tumor cells and further enhances metastasis (16).

VEGF-D is expressed in a range of human tumors, and can correlate with lymph node metastasis and poor patient outcome (Refs. 17–21); for review see Refs. 2, 22). Clinicopathological as well as experimental data indicate that the VEGF-D signaling pathway may be a therapeutic target for restricting the spread of cancer (23, 24). Further, it has been proposed that VEGF-D is an alternative mediator of tumor angiogenesis to VEGF-A (25, 26), that might contribute to mechanisms of resistance to bevacizumab, a widely used anti-cancer drug targeting VEGF-A (27). The analysis of VEGF-D in clinical samples, such as tumor tissues, is complicated by the fact that this is a proteolytically processed protein (28), which can be detected in various forms of different sizes and subunit compositions. It will be essential to understand the functions of the various domains of VEGF-D to design optimal therapeutic and diagnostic approaches targeting the clinically important form(s) of the protein.

The full-length form of VEGF-D is an antiparallel homodimer consisting of subunits comprising a central VEGF homology domain (VHD), containing binding sites for VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3, and N- and C-terminal propeptides flanking the VHD (5). The full-length form can be proteolytically processed outside the cell, by enzymes such as proprotein convertases (29) and plasmin (30), to generate a partially processed form, in which the C-terminal propeptide is cleaved from the VHD, but remains attached to the molecule via disulfide bonding between the N- and C-terminal propeptides on different subunits (28, 31). This partially processed form can be converted to mature VEGF-D, consisting of VHD dimers, via cleavage of the N-terminal propeptide. The mature form has enhanced binding affinities for VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (28). The capacity of cells to promote proteolytic processing varies (29, 32), indicating this is a regulated process, and the relative abundance of the various forms of VEGF-D in the conditioned cell culture media of primary cells or cell lines can consequently be very different. For example, transfected LoVo colon carcinoma cells, which cannot promote VEGF-D processing, accumulate only full-length VEGF-D in the media (29); mouse primary embryonic fibroblasts, Balbc/3T3 cells, and transfected 293EBNA-1 cells, which have an intermediate capacity for VEGF-D processing, accumulate almost all forms of VEGF-D in media including full-length and partially processed material (28, 29, 33); transfected Capan-1 pancreatic cancer cells, which process VEGF-D very efficiently, accumulate predominantly mature VEGF-D (32).

It has been shown that proteolytic processing is absolutely required for VEGF-D-mediated tumor growth and spread (34); however, little is known about the functions of the propeptides in these events. Analysis of propeptide function is complicated by difficulty in purifying, or specifically expressing, partially processed VEGF-D (in which either propeptide has been cleaved from the VHD) in the absence of full-length or mature material (28, 34). Here we circumvent this problem using forms of VEGF-D, in which either propeptide has been deleted, and processing of the other propeptide is blocked by mutation. This allowed us to test the hypothesis that propeptides modulate a variety of interactions of VEGF-D, and its effects in cancer. We show that propeptides determine binding of VEGF-D to VEGF receptor heterodimers, co-receptors and heparin, and influence key aspects of tumor biology such as rates of primary tumor growth and metastasis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

293EBNA-1 and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) were cultured as previously (28, 34), and Suspension FreestyleTM 293-F cells according to the supplier (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

VEGF-D Protein Constructs

The VEGF-D derivatives used in this study are as follows. (i) VEGF-DSSTS.IISS: an N-terminally FLAG-tagged full-length form of human VEGF-D containing mutations in the proteolytic cleavage sites that prevent cleavage of both propeptides (29); (ii) VEGF-DΔNΔC: a mature form of human VEGF-D consisting of the VHD tagged with FLAG at the N terminus (5, 28); (iii) VEGF-D-CPRO: the C-terminal propeptide of human VEGF-D (amino acid residues 206–354) tagged at the N terminus with FLAG (35); (iv) VEGF-DΔNIISS: an N-terminally FLAG-tagged form of VEGF-D (encompassing amino acids 89–354) lacking the N-terminal propeptide, and containing mutations (R204S and R205S) that prevent cleavage of the C-terminal propeptide; (v) VEGF-DΔCSSTS: an N-terminally FLAG-tagged form of VEGF-D (encompassing amino acids 24–205) lacking the C-terminal propeptide, and containing mutations (R85S and R88S) that prevent cleavage of the N-terminal propeptide. VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔNΔC contain the N-terminal region of the VHD thought to be important for interaction with VEGFR-3 (36). Expression vectors for these proteins were generated from pApex-3 (Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Cheshire, CT).

Transfection and Protein Purification

293EBNA-1 cells were transfected, and stably expressing clones selected, as described (34). 293F cells were transfected according to the supplier (Invitrogen). VEGF-D proteins were purified from conditioned media by affinity chromatography on M2 (anti-FLAG) gel as described previously (28), and quantitated spectrophotometrically.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

VEGF-D derivatives were immunoprecipitated and detected in Western blots as described (33, 34). For analysis of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers, HMVECs were treated with growth factors for 10 min, after which cells were lysed for 15 min in ice-cold buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm activated sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). VEGFR-2 was immunoprecipitated and targeted in Western blots with a mab to the C terminus of human VEGFR-2 (55B11, Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), and VEGFR-3 with a polyclonal antibody to the C terminus of human VEGFR-3 (sc-321, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Phosphotyrosine residues were targeted with a mab against Phosphotyramine (4G10, Millipore, Billerica, MA), and VEGF-A with a mab against VEGF-A165 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). For detection, secondary 800 IRDye®-conjugated IgG antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NB) were used. Proteins were visualized, and relative band intensities were measured, on an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Biosensor Analysis

Protein interactions were monitored in real-time on an instrumental optical biosensor using surface plasmon resonance detection (Biacore 3000, GE Healthcare, Giles, UK). Fusion proteins, consisting of the extracellular domains of human VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3 and the Fc portion of human IgG (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), were immobilized onto a CM5 sensor surface using amine coupling chemistry [N-hydroxysuccinimide and N-ethyl-N dimethylaminopropyl-carbodiimide] at a flow rate of 5 ml/min as reported previously (29, 37, 38). Immobilization levels were 5,500 and 5,000 RU for VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3, respectively. VEGF-D derivatives, purified by anti-FLAG affinity chromatography, were subjected to BSA-depletion, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (under reducing and non-reducing conditions) to confirm the presence of dimers, although this approach did not exclude the possibility that aggregated protein was present in the samples. VEGF-D derivatives were diluted in Biacore buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, containing 3.4 mm EDTA, 0.15 mm NaCl and 0.005% (v/v) Tween 20) to the appropriate concentrations (125–2,000 nm) for kinetic analysis. Samples (30 μl) were injected sequentially over the sensor surfaces at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. Following completion of the injection phase, dissociation was monitored in Biacore buffer alone at the same flow rate with running temperature of 25 °C (see supplemental Fig. S1 for representative sensorgrams). The sensor surface was regenerated between injections using 10 μl of 1 m diethanolamine, pH 10, at a flow rate of 20 μl/min. This treatment did not denature the sensor surface as shown by equivalent signals on repeat injection of the same sample. Kinetic rate constants were determined using the BIAevaluation software version 4.1 (GE Healthcare). KD values were determined from kinetic analyses.

ELISAs for Receptor Activation

HMVECs were stimulated with growth factors for 10 min, and samples used in Total and Phospho VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3 ELISAs (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Heparin Affinity Chromatography

Proteins were loaded onto a 1-ml column of heparin-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with PBS to remove unbound protein, and bound protein eluted with a 0.1–2.0 M gradient of NaCl in PBS in 2-ml fractions which were subsequently analyzed by Western blotting.

Binding to Neuropilins

Binding of VEGF-D derivatives to neuropilins was assessed using fusion proteins consisting of the extracellular domains of rat neuropilin-1 or human neuropilin-2, and the Fc portion of human IgG (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as described previously (34).

Mouse Tumor Xenograft Model

Female SCID/NOD mice (Animal Resources Centre, Perth, Australia), 11–12 weeks old, were used. Tumors were generated by injecting 293EBNA-1 cell lines subcutaneously into the mouse flank, and tumor volume determined as described (13). Each study group contained 10 mice and the experiment was conducted twice with similar results in each case. Detection of PECAM-1 or LYVE-1 in tissue sections, immunoprecipitation and Western blotting of tumor tissue to monitor levels of VEGF-D proteins and detection of tumor cells in lymph nodes were carried out as described previously (34), when primary tumors reached ∼2,500 mm3. Statistical analyses were as described previously (34).

RESULTS

Expression and Receptor Binding of VEGF-D Propeptide Mutants

To study the role of propeptides in the molecular interactions and biological functions of VEGF-D, mutants were created in which either propeptide had been deleted, and the processing site for the remaining propeptide mutated to block processing. These proteins, tagged with the FLAG octapeptide, were designated VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS, and are represented in Fig. 1A. Expression of these proteins in 293F or 293EBNA-1 cells, and reducing SDS-PAGE analysis, revealed that the subunits of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS were ∼43 kDa and ∼31 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1B), as expected based on the known sizes of the VHD and propeptides (28). Neither protein was processed to generate mature VEGF-D, the subunit of which is ∼21 kDa (5).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS, and of receptor binding and activation. A, schematic representation of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS, asterisks denote arginine residues in the proteolytic cleavage sites that have been mutated to serine, N-pro and C-pro denote the propeptides, F denotes FLAG peptide and numbers denote positions in the primary structure of VEGF-D. The processing site mutated in VEGF-DΔCSSTS is the one at which the N-terminal propeptide has been reported to be most commonly cleaved from the VHD (defined previously as the “major” site) (28). B, immunoprecipitation and Western blotting (IP, Blot) and Coomassie Blue staining (Coom). Conditioned media from transiently transfected 293F cells expressing VEGF-DΔNIISS (ΔN-IISS) or VEGF-DΔCSSTS (ΔC-SSTS) were subjected to immunoprecipitation, reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The immunoprecipitation and Western blots were conducted with M2 anti-FLAG antibody for VEGF-DΔNIISS, and with anti-VHD antibodies for VEGF-DΔCSSTS. For Coomassie staining, VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS stably expressed in 293EBNA cells were purified by anti-FLAG affinity chromatography and subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE. Sizes of molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown to the left and schematics of VEGF-D species to the right. C, results from biosensor analysis of purified VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS binding to the extracellular domains of VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3. Previously published results for purified VEGF-DSSTS.IISS and VEGF-DΔNΔC (29) are shown for comparison. Representative sensorgrams for the interactions of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS with receptor constructs are shown in supplemental Fig. S1. D, receptor activation. HMVECs were stimulated for 10 min with the indicated concentrations of purified VEGF-D variants and used in VEGFR-2 (left panel) or VEGFR-3 (right panel) phosphorylated and total ELISAs. Receptor activation is measured by the ratio of phosphorylated to total VEGF receptor. Error bars indicate S.E., and asterisks denote p < 0.05 (Student's t test).

We used surface plasmon resonance to assess binding affinities of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS for the extracellular domains of VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (Fig. 1C; see supplemental Fig. S1 for representative sensorgrams). VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS had ∼50- and ∼100-fold greater VEGFR-2 affinity, respectively, than VEGF-DSSTS.IISS (a form of full-length VEGF-D, which cannot be processed (29)). In contrast, VEGF-DΔNΔC (a form of mature VEGF-D (5)) had much stronger VEGFR-2 affinity than both VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS. The VEGFR-3 affinities of VEGF-DSSTS.IISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS were similar, 17–20-fold lower than that of VEGF-DΔNΔC. The VEGFR-3 affinity of VEGF-DΔNIISS was 3–4-fold lower than those of VEGF-DSSTS.IISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS, and 68-fold lower than that of VEGF-DΔNΔC. These data show that removal of either propeptide significantly enhances VEGFR-2 affinity, which is further enhanced when both propeptides are removed. However, removal of either propeptide does not greatly affect VEGFR-3 affinity (full-length VEGF-D exhibits reasonable VEGFR-3 affinity (29)), but removal of both propeptides significantly enhances this affinity. The ability of VEGF-D variants to activate VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 on HMVECs was analyzed (Fig. 1D). Both VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS activated VEGFR-2 (in contrast, VEGF-DSSTS.IISS cannot activate VEGFR-2 (34)) indicating that removal of either propeptide allows VEGFR-2 activation. VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS activated VEGFR-3 (Fig. 1D), as can VEGF-DSSTS.IISS (34).

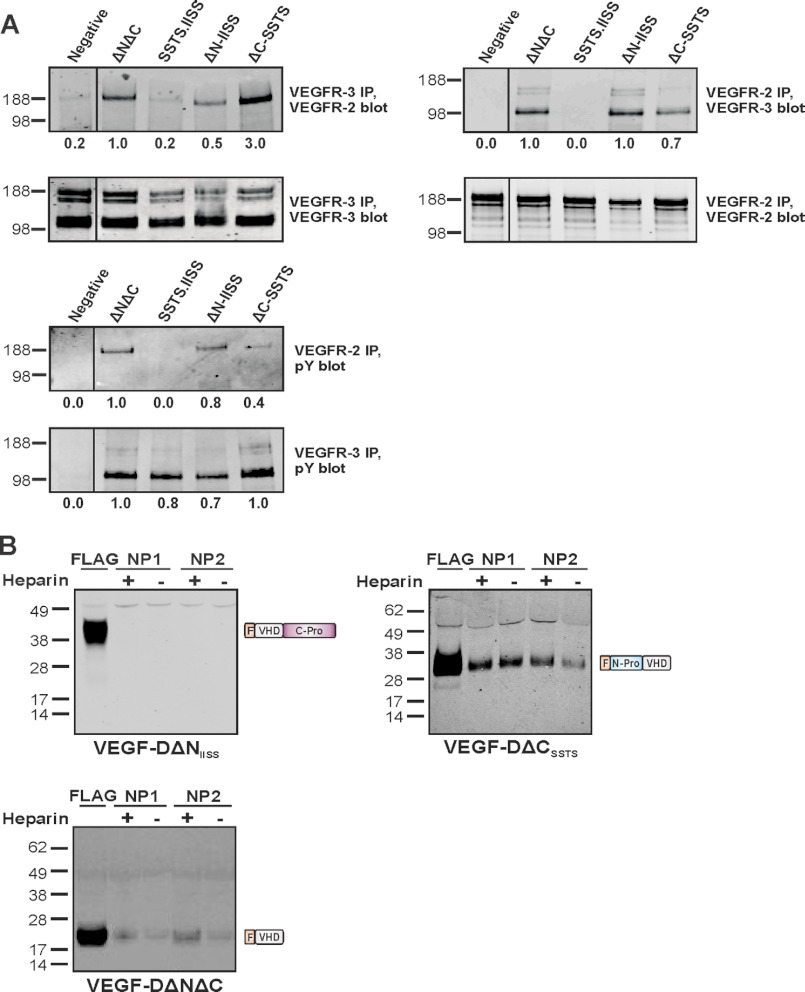

VEGF-D Propeptides Determine Receptor Heterodimerization and Interactions with Neuropilins

VEGF-D induces formation of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers on endothelial cells, which are thought to positively regulate angiogenic sprouting (39), although it was unclear which forms of VEGF-D promote this heterodimerization. To monitor the influence of propeptides on the formation of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers, HMVECs were stimulated with VEGF-D variants, and receptor heterodimers assessed by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting (Fig. 2A). VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers were induced by either VEGF-DΔNIISS or VEGF-DΔCSSTS at 500 ng/ml, but not at 200 ng/ml (data not shown). In contrast, receptor heterodimers were not observed following stimulation with VEGF-DSSTS.IISS at 500 ng/ml. As expected from previous studies (39), VEGF-DΔNΔC at 200 ng/ml induced receptor heterodimers. Tyrosine phosphorylation of both VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 was observed in response to all forms of VEGF-D tested (Fig. 2A), with the exception that VEGF-DSSTS.IISS did not induce VEGFR-2 phosphorylation. These results indicate that VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS activate VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3, and drive heterodimer formation, but suggest that processing to remove both propeptides enhances these effects.

FIGURE 2.

Induction of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers and neuropilin interactions. A, induction of receptor heterodimers. HMVECs were stimulated for 10 min with purified VEGF-DΔNIISS (ΔN-IISS), VEGF-DΔCSSTS (ΔC-SSTS), VEGF-DSSTS.IISS (SSTS.IISS) (all at 500 ng/ml), or VEGF-DΔNΔC (200 ng/ml), or left unstimulated (Negative). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against VEGFR-3 and analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot with an antibody against VEGFR-2 to assess heterodimers, or with an antibody against VEGFR-3 to confirm the presence of this receptor (upper, left panels). Alternatively, lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against VEGFR-2 and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blot with an antibody against VEGFR-3 to assess heterodimers, or with an antibody against VEGFR-2 to confirm the presence of this receptor (upper right panels). Activation of receptors was assessed by immunoprecipitation with VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3 antibodies and SDS-PAGE/Western blot with an antibody against phosphotyrosine (bottom panels). VEGFR-2 migrates predominantly at ∼230 kDa, whereas VEGFR-3 migrates as three bands, a ∼125 kDa cleaved form and two uncleaved forms of ∼175 kDa and ∼195 kDa that differ in the degree of glycosylation (56). Sizes of molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown to the left. Numbers below panels represent the relative intensities of the major bands, with the values for the major ΔNΔC band in each blot defined as 1.0. Black lines within Western blots indicate removal of irrelevant tracks from the images, all lanes in a blot come from the same exposure of the same membrane. B, neuropilin interactions. Conditioned media from 293EBNA-1 cells expressing VEGF-D variants were precipitated with NP1- or NP2-Ig fusion proteins, in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml heparin, and analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for VEGF-D with antibodies recognizing the FLAG tag. Tracks labeled FLAG indicate controls in which VEGF-D variants were precipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Sizes of molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown to the left and schematics of VEGF-D variants to the right.

It has been reported that partially processed, but not full-length, VEGF-D binds neuropilin (NP)1 and NP2 (34, 40) which act as co-receptors with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (41, 42) and are key molecules in the development of blood vessels and lymphatics (43, 44). To further characterize the binding of VEGF-D to NPs, we tested the capacity of VEGF-D variants to bind fusion proteins comprised of the extracellular domains of NP1 or NP2 and the Fc portion of human IgG1 (Fig. 2B). These experiments were conducted in the presence or absence of heparin, a molecule which can be required for binding of VEGF-C to NP1 (40). VEGF-DΔNIISS did not bind either the NP1 or NP2 construct irrespective of the presence or absence of heparin, however, VEGF-DΔCSSTS bound both constructs. Heparin slightly enhanced the binding of VEGF-DΔCSSTS to NP2, but not to NP1. To further assess the domain(s) of VEGF-D that binds NPs, NP constructs were used to precipitate VEGF-DΔNΔC. VEGF-DΔNΔC bound both NP1 and NP2, interactions that were slightly enhanced by heparin. However, binding of VEGF-DΔCSSTS to NP1 and NP2 generated more intense bands indicating that the N-terminal propeptide enhances NP interactions.

The C-terminal Propeptide Mediates Heparin Binding

The ability of VEGF family members, including VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF, to bind heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) in the extracellular matrix or at the cell surface can influence the concentration gradient and bioavailability of growth factor, which can in turn modulate bioactivity (45). As the ability of VEGF-D to bind HSPGs or heparin has not been documented, we subjected VEGF-D variants to heparin Sepharose affinity chromatography using VEGF-A165, which binds HSPGs (46, 47), as positive control. VEGF-A165 was retained on the column and subsequently eluted from the heparin Sepharose at NaCl concentrations from 0.9 to 1.4 m, reflecting its interaction with heparin (Fig. 3). Likewise, significant proportions of VEGF-DSSTS.IISS and VEGF-DΔNIISS were retained on the column, and subsequently eluted at 0.6 to 1.1 m and 0.6 to 1.2 m NaCl, respectively, indicating that these derivatives bind heparin. In contrast, VEGF-DΔCSSTS was not retained on the column. To further assess the domains of VEGF-DΔNIISS that confer binding to heparin, preparations of VEGF-DΔNΔC or the C-terminal propeptide (VEGF-D-CPRO) were assessed. Most of the VEGF-DΔNΔC protein did not bind to the column, however a small proportion was retained and eluted at 0.1 to 0.5 m NaCl, whereas most of the VEGF-D-CPRO did bind and was eluted at 0.6 to 1.2 m NaCl. These data indicate that binding of VEGF-DΔNΔC to heparin is modest, and that the interaction of VEGF-DΔNIISS to heparin is mediated predominantly by the C-terminal propeptide.

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of heparin binding. Binding of VEGF-D variants, and VEGF-A165, to heparin was analyzed by affinity chromatography. Purified proteins were loaded onto heparin-Sepharose columns and flowthrough (FT), containing unbound protein, was collected. Bound proteins were eluted from columns using buffers of increasing NaCl concentration (M), as indicated above the blots. Fractions were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies targeting FLAG, to detect VEGF-D variants, or with an anti-VEGF-A antibody. Purified protein samples (S) that had not been subjected to heparin Sepharose affinity chromatography are shown for comparison. Sizes of molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown to the left.

Propeptides Influence Primary Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis

The data presented above indicate that the two VEGF-D propeptides modulate interactions with distinct signaling molecules known to influence angiogenesis or lymphangiogenesis, which are important processes in the growth and spread of cancer. We therefore monitored the effects of the VEGF-D propeptides in a mouse tumor xenograft model, involving 293EBNA-1 cell lines stably expressing VEGF-DΔNIISS or VEGF-DΔCSSTS. The 293EBNA-1 model was chosen because it does not express significant quantities of VEGF family members and it produces slow growing and poorly vascularized epithelioid-like tumors in mice (13). Hence it provides an appropriate “background” in which to monitor the effects of VEGF-D on tumor biology. Further, expression of mature VEGF-D in this model (via stable transfection) promotes angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, primary tumor growth, and lymph node metastasis, whereas a full-length form of VEGF-D that cannot be processed (i.e. VEGF-DSSTS.IISS) did not promote any of these key features of tumor biology (34). For our study, a 293EBNA-1 cell line stably transfected with expression vector lacking VEGF-D sequence (designated “Vector Control”) was used as negative control, and a cell line stably expressing VEGF-DΔNΔC was the positive control. The cell lines expressing forms of VEGF-D produced comparable levels of these N-terminally FLAG-tagged proteins as assessed by Western blotting using an anti-FLAG antibody (data not shown). These cell lines were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of SCID/NOD mice to generate tumors. Tumors did not process either VEGF-DΔNIISS or VEGF-DΔCSSTS to mature VEGF-D (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Growth and morphology of tumors expressing VEGF-D variants, and analysis of angiogenesis. 293EBNA-1 cells stably expressing various forms of VEGF-D were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of SCID/NOD mice to generate tumors (n = 10 per study group). A, VEGF-D expression in tumors. VEGF-D proteins in lysates from tumors expressing VEGF-DΔNΔC (ΔNΔC), VEGF-DΔNIISS (ΔN-IISS) or VEGF-DΔCSSTS (ΔC-SSTS), or from Vector Control tumors, were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using antibodies targeting the VHD. Sizes of molecular weight markers (in kDa) are shown to the left. The black line within the Western blot indicates removal of irrelevant tracks from the image, all lanes in the blot come from the same exposure of the same membrane. The blot compares one tumor from each study group, and the results are representative of a series of immunoprecipitations/Western blots comparing five tumors from each group. Protein concentrations of all lysates were measured by spectrophotometry to ensure that all lysate samples used for immunoprecipitations were matched for total protein content. B, growth rates of subcutaneous tumors. Asterisks indicate days on which VEGF-DΔNIISS tumors were significantly smaller than both VEGF-DΔNΔC and VEGF-DΔCSSTS tumors (p < 0.05; Student's t test). Error bars represent S.E. C, macroscopic appearance of tumors upon reaching a volume of ∼2,500 mm3. Data generated from VEGF-DΔNΔC tumors has been reported previously (34) and is shown for comparison. D, analysis of tumor blood vessels. Tissue sections from tumors expressing different forms of VEGF-D were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with antibodies to PECAM-1 (brown staining) for blood vessels (left panels). Graph shows quantitation of blood vessel endothelium in tumor sections as assessed by the number of pixels positively stained for PECAM-1. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in the abundance of blood vessel endothelium (p < 0.01; Student's t test). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. The experiments described in this figure were conducted twice with similar results in each case, the results of one experiment are shown here.

The growth rates of tumors expressing VEGF-DΔNΔC or VEGF-DΔCSSTS were similar, and they grew significantly faster than Vector Control tumors or tumors expressing VEGF-DΔNIISS (Fig. 4B; morphology of the tumors is shown in Fig. 4C). The growth of tumors expressing VEGF-DΔNIISS was not statistically different from Vector Control tumors. Given that VEGF-DSSTS.IISS, a full-length form that cannot be processed, does not promote tumor growth in this model at all (34), these findings indicate that removal of the C-terminal propeptide, but not the N-terminal propeptide, from full-length VEGF-D enhances tumor growth.

Blood vessel endothelium in the tumors was quantitated by immunostaining for PECAM-1 (Fig. 4D). There was no statistically significant difference in staining between VEGF-DΔNΔC and VEGF-DΔCSSTS tumors, and both tumor groups contained significantly more blood vessel endothelium than VEGF-DΔNIISS or Vector Control tumors. Given that VEGF-DSSTS.IISS does not promote angiogenesis in this model (34), these data indicate that removal of the C-terminal propeptide, but not the N-terminal propeptide, from full-length VEGF-D promotes angiogenesis which likely led to the fast growth of VEGF-DΔCSSTS tumors.

Propeptides Influence Lymph Node Metastasis and Tumor Lymphangiogenesis

As VEGF-D can promote lymph node metastasis (13), axillary lymph nodes were assessed for the presence of tumor cells which were easily identified due to their dark staining, enlarged nuclei and irregular shape (Fig. 5A). The expression of VEGF-DΔNΔC in tumors significantly enhanced lymph node metastasis compared with Vector Control tumors, which did not exhibit any metastatic spread to lymph nodes (Fig. 5B). When tumors expressed VEGF-DΔNIISS or VEGF-DΔCSSTS, metastatic spread to lymph nodes did occur but was significantly reduced compared with VEGF-DΔNΔC tumors. These findings indicate that removal of both propeptides is required for VEGF-D to most efficiently promote lymph node metastasis.

FIGURE 5.

Impact of N- and C-terminal propeptides on lymph node metastasis and lymphangiogenesis. A, effects on lymph node metastasis. Representative images of lymph node tissue sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, that were taken from mice with primary tumors ∼2,500 mm3 in size. Top panel shows lymph node from a mouse with a metastatic VEGF-DΔNΔC tumor; bottom panel shows a lymph node from a mouse with a non-metastatic Vector Control tumor. Arrowheads indicate clusters of tumor cells. B, occurrence of lymph node metastasis in tumor xenografts. Mice were scored positive for metastasis if tumor cells were observed in the axillary lymph nodes. Numbers indicate the proportion of mice with primary tumors that scored positive for lymph node metastasis. Asterisks indicate those groups with significantly lower rates of metastasis than the VEGF-DΔNΔC study group, as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05). Data generated from VEGF-DΔNΔC tumors has been reported previously (34) and is shown for comparison. The data from two independent experiments is combined in the table. C, analysis of tumor lymphatic vessels. Tissue sections were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with antibodies to LYVE-1 (brown staining) for lymphatic vessels (left panels). Graph shows quantitation of lymphatic endothelium in tumor sections as assessed by the number of pixels positively stained for LYVE-1. ΔN-IISS denotes VEGF-DΔNIISS and ΔC-SSTS denotes VEGF-DΔCSSTS. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in abundance of lymphatic endothelium (p < 0.01: Student's t test). Error bars represent S.E. The experiments described in this figure were conducted twice with similar results in each case, the results of one experiment are shown here in panels A and C.

The abundance of lymphatic vessel endothelium in tumors was monitored by immunohistochemistry for LYVE-1 (Fig. 5C). VEGF-DΔNΔC tumors contained regions with abundant lymphatics, particularly at the tumor periphery. Vector Control and VEGF-DΔCSSTS tumors both had a low abundance of lymphatic endothelium, i.e. significantly less than for VEGF-DΔNΔC tumors. VEGF-DΔNIISS tumors contained regions at the tumor periphery with abundant lymphatics and exhibited significantly greater overall LYVE-1 staining than Vector Control or VEGF-DΔCSSTS tumors. Given that VEGF-DSSTS.IISS does not promote lymphangiogenesis in this model (34), these data indicate that removal of the N-terminal propeptide from full-length VEGF-D (as indicated by VEGF-DΔNIISS) leads to an increase in tumor lymphangiogenesis.

DISCUSSION

The findings reported here show that the propeptides of VEGF-D are critical determinants of a range of molecular interactions with receptors, co-receptors and heparin. For example, the presence of both propeptides in the full-length protein prevents VEGF-D-mediated formation of VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers, whereas removal of either, or both, propeptides allows receptor heterodimerization to occur. The inability of full-length VEGF-D to drive receptor heterodimerization likely reflects its poor affinity for VEGFR-2 (29). However, full-length VEGF-D can drive activation of VEGFR-3 (34). Given that VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers have altered trans-phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the VEGFR-3 subunit compared with those of VEGFR-3 homodimers (48), the removal of propeptides from full-length VEGF-D would result in mechanistically distinct modes of signaling via VEGFR-3. Importantly, VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers are thought to positively regulate angiogenic sprouting (39). It is therefore noteworthy that VEGF-D is localized in vascular smooth muscle surrounding large arteries in adult human tissues (35, 49, 50). This indicates that VEGF-D could access blood vessels and promote angiogenesis, possibly via VEGFR-2/VEGFR-3 heterodimers on angiogenic sprouts, in response to tissue damage. It was recently shown that mature VEGF-C binds heparan sulfate from lymphatic endothelial cells as well as heparin-Sepharose (51), however, the capacity of other forms of VEGF-C to bind heparin is unknown. Here we show that mature VEGF-D binds heparin, although this interaction did not appear to be of high affinity. Further, the C-terminal propeptide of VEGF-D binds heparin strongly, and confers this property on full-length VEGF-D indicating that proteolytic processing to remove the C-terminal propeptide would be a determinant of this interaction. Although there is no obvious heparin-binding domain in the C-terminal propeptide of VEGF-D (as assessed by comparison of the primary structure with VEGF-A (46, 52) or other heparin-binding proteins), it is possible that basic residues are clustered together in the 3-dimensional structure of this propeptide to allow heparin binding. However, the crystal structure of the C-terminal propeptide remains to be elucidated. The interactions of VEGF-A isoforms with HSPGs can influence VEGF-A stability and bioavailability, and the amplitude and duration of signaling interactions with receptors (45), whether there is similar functional relevance to the interaction of VEGF-D with HSPGs remains to be determined. A variety of cells (i.e. cell lines or primary cell cultures) have been reported to produce significant quantities of full-length VEGF-D and the most abundant partially processed form, in which the C-terminal propeptide has been cleaved but the N-terminal propeptide has not (28, 29). The latter is thought to retain the C-terminal propeptide due to disulfide bonding between N- and C-terminal propeptides on different subunits in the antiparallel dimer. The presence of the C-terminal propeptide in these forms of VEGF-D should allow them to bind HSPGs. If so, cleavage of both propeptides would be required to maximally enhance the solubility of VEGF-D in a biological setting.

NP1 and NP2 act as co-receptors with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (41, 42), and are important during embryogenesis for development of blood vessels and lymphatics (43, 44). It was already known that full-length VEGF-D cannot bind NPs but processing of the C-terminal propeptide allows binding (34, 40). Here we show that mature VEGF-D binds both NP1 and NP2, and that binding is enhanced for both receptors by the presence of the N-terminal propeptide (i.e. VEGF-DΔCSSTS binds better than VEGF-DΔNΔC). However, the C-terminal propeptide inhibits binding to both NPs, i.e. VEGF-DΔNIISS cannot bind NPs despite the presence of the VHD. The inhibitory effect of the C-terminal propeptide also explains why full-length VEGF-D does not bind NPs.

It has been reported that mature VEGF-D promotes tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, as well as tumor growth and lymph node metastasis, but a form of full length-VEGF-D which cannot be processed (i.e. VEGF-DSSTS.IISS) does not promote any of these aspects of tumor biology (34). However, the contribution of each propeptide to these observations was unkown. We observed that tumors expressing VEGF-DΔCSSTS contained significantly more blood vessel endothelium and grew faster than VEGF-DSSTS.IISS and VEGF-DΔNIISS tumors. This may reflect the enhanced affinity of VEGF-DΔCSSTS for VEGFR-2 compared with VEGF-DSSTS.IISS. While VEGF-DΔNIISS has a similar affinity for VEGFR-2 as VEGF-DΔCSSTS, it is not able to bind NPs. Interactions with both NP1 and VEGFR-2 may be central to the enhanced angiogenesis induced by VEGF-DΔCSSTS compared with VEGF-DΔNIISS. This finding is consistent with previous studies which have demonstrated that the formation of a complex of NP1 and VEGFR-2 can enhance VEGF-A binding and promote VEGFR-2 activation, thereby enhancing angiogenesis (41, 53, 54). The extensive angiogenesis in tumors expressing VEGF-DΔCSSTS likely accounts for their fast growth rate, and shows that a species of VEGF-D containing the N-terminal propeptide and VHD is angiogenic. These findings are the first to indicate that removal of the C-terminal propeptide is rate-limiting for VEGF-D to promote angiogenesis and tumor growth.

It was previously shown that a partially processed form of VEGF-D, containing the N-terminal propeptide and VHD, bound NP2 (40) and VEGFR-3 (28), and that interaction between these receptors mediates lymphatic vessel sprouting in response to VEGF-C (55). Hence it was unexpected that VEGF-DΔCSSTS did not promote significant lymphangiogenesis in the tumor model. In contrast, VEGF-DΔNIISS induced growth of lymphatics, indicating that a species of VEGF-D containing the VHD and C-terminal propeptide is lymphangiogenic. As the affinities of VEGF-DΔNIISS and VEGF-DΔCSSTS for VEGFR-3 as assessed by biosensor are comparable, the explanation for why VEGF-DΔCSSTS lacks lymphangiogenic activity is unclear. However, it is possible that the capacity of VEGF-DΔNIISS to bind HSPGs, which is not shared by VEGF-DΔCSSTS, may explain these observations. Importantly, a recent study indicated that heparan sulfate, present on lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), enhances binding of VEGF-C to VEGFR-3, phosphorylation of VEGFR-3, and migration, proliferation and sprouting of LEC in response to VEGF-C (51). If VEGF-D is similar to VEGF-C in these respects, the capacity of VEGF-DΔNIISS to bind HSPGs should enhance its potency, relative to VEGF-DΔCSSTS, for driving signaling via VEGFR-3 in LEC, and for promoting lymphangiogenesis. Our observation that VEGF-DΔNIISS can induce lymphangiogenesis at comparable levels to VEGF-DΔNΔC, despite having a 68-fold lower VEGFR-3 affinity, may also be due to the stronger binding of VEGF-DΔNIISS to HSPGs.

Our data show that the propeptides of VEGF-D are critical determinants of VEGF receptor heterodimerization, and interactions with neuropilin co-receptors and heparin. The propeptides exert profound effects on the capacity of VEGF-D to drive tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, and thereby promote the growth and spread of cancer.

This work was supported by a Program Grant and Research Fellowships (to S. A. S. and M. G. A.) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, a Melbourne Research Scholarship (to N.C. H.) and funds from the Operational Infrastructure Support Program provided by the Victorian Government, Australia. S. A. S. and M. G. A. are consultants to Vegenics Ltd., a company developing anti-cancer therapeutics.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- LAM

- lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- VHD

- VEGF homology domain

- HSPG

- heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- LEC

- lymphatic endothelial cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tammela T., Alitalo K. (2010) Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell 140, 460–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Achen M. G., McColl B. K., Stacker S. A. (2005) Focus on lymphangiogenesis in tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell 7, 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Potente M., Gerhardt H., Carmeliet P. (2011) Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146, 873–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seyama K., Kumasaka T., Kurihara M., Mitani K., Sato T. (2010) Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a disease involving the lymphatic system. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 8, 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Achen M. G., Jeltsch M., Kukk E., Mäkinen T., Vitali A., Wilks A. F., Alitalo K., Stacker S. A. (1998) Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 548–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhardwaj S., Roy H., Gruchala M., Viita H., Kholova I., Kokina I., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A., Hedman M., Alitalo K., Ylä-Herttuala S. (2003) Angiogenic responses of vascular endothelial growth factors in periadventitial tissue. Hum. Gene Ther. 14, 1451–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wise L. M., Ueda N., Dryden N. H., Fleming S. B., Caesar C., Roufail S., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A., Mercer A. A. (2003) Viral vascular endothelial growth factors vary extensively in amino acid sequence, receptor-binding specificities, and the ability to induce vascular permeability yet are uniformly active mitogens. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38004–38014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rutanen J., Rissanen T. T., Markkanen J. E., Gruchala M., Silvennoinen P., Kivelä A., Hedman A., Hedman M., Heikura T., Ordén M. R., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Hartikainen J., Ylä-Herttuala S. (2004) Adenoviral catheter-mediated intramyocardial gene transfer using the mature form of vascular endothelial growth factor-D induces transmural angiogenesis in porcine heart. Circulation 109, 1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rissanen T. T., Markkanen J. E., Gruchala M., Heikura T., Puranen A., Kettunen M. I., Kholová I., Kauppinen R. A., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A., Alitalo K., Ylä-Herttuala S. (2003) VEGF-D is the strongest angiogenic and lymphangiogenic effector among VEGFs delivered into skeletal muscle via adenoviruses. Circ. Res. 92, 1098–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haiko P., Makinen T., Keskitalo S., Taipale J., Karkkainen M. J., Baldwin M. E., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Alitalo K. (2008) Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and VEGF-D is not equivalent to VEGF receptor 3 deletion in mouse embryos. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4843–4850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baldwin M. E., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2002) Molecular control of lymphangiogenesis. Bioessays 24, 1030–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Achen M. G., Stacker S.A. (2012) Vascular endothelial growth factor-D:signalling mechanisms, biology and clinical relevance. Growth Factors 30, 283–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stacker S. A., Caesar C., Baldwin M. E., Thornton G. E., Williams R. A., Prevo R., Jackson D. G., Nishikawa S., Kubo H., Achen M. G. (2001) VEGF-D promotes the metastatic spread of tumor cells via the lymphatics. Nature Med. 7, 186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kopfstein L., Veikkola T., Djonov V. G., Baeriswyl V., Schomber T., Strittmatter K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Alitalo K., Christofori G. (2007) Distinct roles of vascular endothelial growth factor-D in lymphangiogenesis and metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 1348–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shayan R., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A. (2006) Lymphatic vessels in cancer metastasis: bridging the gaps. Carcinogenesis 27, 1729–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karnezis T., Shayan R., Caesar C., Roufail S., Harris N. C., Ardipradja K., Zhang Y. F., Williams S. P., Farnsworth R. H., Chai M. G., Rupasinghe T. W., Tull D. L., Baldwin M. E., Sloan E. K., Fox S. B., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A. (2012) VEGF-D promotes tumor metastasis by regulating prostaglandins produced by the collecting lymphatic endothelium. Cancer Cell 21, 181–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Debinski W., Slagle-Webb B., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A., Tulchinsky E., Gillespie G. Y., Gibo D. M. (2001) VEGF-D is an X-linked/AP-1 regulated putative onco-angiogen in human glioblastoma multiforme. Mol. Med. 7, 598–608 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. White J. D., Hewett P. W., Kosuge D., McCulloch T., Enholm B. C., Carmichael J., Murray J. C. (2002) Vascular endothelial growth factor-D expression is an independent prognostic marker for survival in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 62, 1669–1675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jüttner S., Wissmann C., Jöns T., Vieth M., Hertel J., Gretschel S., Schlag P. M., Kemmner W., Höcker M. (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor-D and its receptor VEGFR-3: two novel independent prognostic markers in gastric adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 228–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Iterson V., Leidenius M., von Smitten K., Bono P., Heikkilä P. (2007) VEGF-D in association with VEGFR-3 promotes nodal metastasis in human invasive lobular breast cancer. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 128, 759–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakamura Y., Yasuoka H., Tsujimoto M., Yang Q., Imabun S., Nakahara M., Nakao K., Nakamura M., Mori I., Kakudo K. (2003) Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor D in breast carcinoma with long-term follow-up. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 716–721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stacker S. A., Williams R. A., Achen M. G. (2004) Lymphangiogenic growth factors as markers of tumor metastasis. APMIS 112, 539–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Achen M. G., Mann G. B., Stacker S. A. (2006) Targeting lymphangiogenesis to prevent tumour metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 94, 1355–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Achen M. G., Stacker S. A. (2008) Molecular control of lymphatic metastasis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1131, 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moffat B. A., Chen M., Kariaapper M. S., Hamstra D. A., Hall D. E., Stojanovska J., Johnson T. D., Blaivas M., Kumar M., Chenevert T. L., Rehemtulla A., Ross B. D. (2006) Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A causes a paradoxical increase in tumor blood flow and up-regulation of VEGF-D. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 1525–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grau S., Thorsteinsdottir J., von Baumgarten L., Winkler F., Tonn J. C., Schichor C. (2011) Bevacizumab can induce reactivity to VEGF-C and -D in human brain and tumour derived endothelial cells. J. Neurooncol. 104, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurwitz H., Fehrenbacher L., Novotny W., Cartwright T., Hainsworth J., Heim W., Berlin J., Baron A., Griffing S., Holmgren E., Ferrara N., Fyfe G., Rogers B., Ross R., Kabbinavar F. (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 350, 2335–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stacker S. A., Stenvers K., Caesar C., Vitali A., Domagala T., Nice E., Roufail S., Simpson R. J., Moritz R., Karpanen T., Alitalo K., Achen M. G. (1999) Biosynthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor-D involves proteolytic processing which generates non-covalent homodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32127–32136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McColl B. K., Paavonen K., Karnezis T., Harris N. C., Davydova N., Rothacker J., Nice E. C., Harder K. W., Roufail S., Hibbs M. L., Rogers P. A., Alitalo K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2007) Proprotein convertases promote processing of VEGF-D, a critical step for binding the angiogenic receptor VEGFR-2. FASEB J. 21, 1088–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McColl B. K., Baldwin M. E., Roufail S., Freeman C., Moritz R. L., Simpson R. J., Alitalo K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2003) Plasmin activates the lymphangiogenic growth factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D. J. Exp. Med. 198, 863–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baldwin M. E., Roufail S., Halford M. M., Alitalo K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2001) Multiple forms of mouse vascular endothelial growth factor-D are generated by RNA splicing and proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44307–44314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Von Marschall Z., Scholz A., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Jackson D. G., Alves F., Schirner M., Haberey M., Thierauch K. H., Wiedenmann B., Rosewicz S. (2005) Vascular endothelial growth factor-D induces lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in models of ductal pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 27, 669–679 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baldwin M. E., Halford M. M., Roufail S., Williams R. A., Hibbs M. L., Grail D., Kubo H., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2005) Vascular endothelial growth factor d is dispensable for development of the lymphatic system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2441–2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris N. C., Paavonen K., Davydova N., Roufail S., Sato T., Zhang Y. F., Karnezis T., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2011) Proteolytic processing of vascular endothelial growth factor-D is essential for its capacity to promote the growth and spread of cancer. FASEB J. 25, 2615–2625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Achen M. G., Williams R. A., Minekus M. P., Thornton G. E., Stenvers K., Rogers P. A., Lederman F., Roufail S., Stacker S. A. (2001) Localization of vascular endothelial growth factor-D in malignant melanoma suggests a role in tumour angiogenesis. J. Pathol. 193, 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leppänen V. M., Jeltsch M., Anisimov A., Tvorogov D., Aho K., Kalkkinen N., Toivanen P., Ylä-Herttuala S., Ballmer-Hofer K., Alitalo K. (2011) Structural determinants of vascular endothelial growth factor-D receptor binding and specificity. Blood 117, 1507–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nice E. C., Catimel B. (1999) Instrumental biosensors: new perspectives for the analysis of biomolecular interactions. Bioessays 21, 339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baldwin M. E., Catimel B., Nice E. C., Roufail S., Hall N. E., Stenvers K. L., Karkkainen M. J., Alitalo K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G. (2001) The specificity of receptor binding by vascular endothelial growth factor-D is different in mouse and man. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19166–19171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nilsson I., Bahram F., Li X., Gualandi L., Koch S., Jarvius M., Söderberg O., Anisimov A., Kholová I., Pytowski B., Baldwin M., Ylä-Herttuala S., Alitalo K., Kreuger J., Claesson-Welsh L. (2010) VEGF receptor 2/-3 heterodimers detected in situ by proximity ligation on angiogenic sprouts. EMBO J. 29, 1377–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kärpänen T., Heckman C. A., Keskitalo S., Jeltsch M., Ollila H., Neufeld G., Tamagnone L., Alitalo K. (2006) Functional interaction of VEGF-C and VEGF-D with neuropilin receptors. FASEB J. 20, 1462–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Soker S., Takashima S., Miao H. Q., Neufeld G., Klagsbrun M. (1998) Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell 92, 735–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Favier B., Alam A., Barron P., Bonnin J., Laboudie P., Fons P., Mandron M., Herault J. P., Neufeld G., Savi P., Herbert J. M., Bono F. (2006) Neuropilin-2 interacts with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 and promotes human endothelial cell survival and migration. Blood 108, 1243–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kawasaki T., Kitsukawa T., Bekku Y., Matsuda Y., Sanbo M., Yagi T., Fujisawa H. (1999) A requirement for neuropilin-1 in embryonic vessel formation. Development 126, 4895–4902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yuan L., Moyon D., Pardanaud L., Bréant C., Karkkainen M. J., Alitalo K., Eichmann A. (2002) Abnormal lymphatic vessel development in neuropilin 2 mutant mice. Development 129, 4797–4806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ferrara N. (2010) Binding to the extracellular matrix and proteolytic processing: two key mechanisms regulating vascular endothelial growth factor action. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 687–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keyt B. A., Berleau L. T., Nguyen H. V., Chen H., Heinsohn H., Vandlen R., Ferrara N. (1996) The carboxyl-terminal domain (111–165) of vascular endothelial growth factor is critical for its mitogenic potency. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7788–7795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Houck K. A., Leung D. W., Rowland A. M., Winer J., Ferrara N. (1992) Dual regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioavailability by genetic and proteolytic mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 26031–26037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dixelius J., Makinen T., Wirzenius M., Karkkainen M. J., Wernstedt C., Alitalo K., Claesson-Welsh L. (2003) Ligand-induced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR-3) heterodimerization with VEGFR-2 in primary lymphatic endothelial cells regulates tyrosine phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40973–40979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Partanen T. A., Arola J., Saaristo A., Jussila L., Ora A., Miettinen M., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Alitalo K. (2000) VEGF-C and VEGF-D expression in neuroendocrine cells and their receptor, VEGFR-3, in fenestrated blood vessels in human tissues. FASEB J. 14, 2087–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rutanen J., Leppänen P., Tuomisto T. T., Rissanen T. T., Hiltunen M. O., Vajanto I., Niemi M., Häkkinen T., Karkola K., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Alitalo K., Ylä-Herttuala S. (2003) Vascular endothelial growth factor-D expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. Cardiovasc. Res. 59, 971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yin X., Johns S. C., Lawrence R., Xu D., Reddi K., Bishop J. R., Varner J. A., Fuster M. M. (2011) Lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency results in altered growth responses to vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 14952–14962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keck R. G., Berleau L., Harris R., Keyt B. A. (1997) Disulfide structure of the heparin binding domain in vascular endothelial growth factor: characterization of posttranslational modifications in VEGF. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 344, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shraga-Heled N., Kessler O., Prahst C., Kroll J., Augustin H., Neufeld G. (2007) Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 enhance VEGF121 stimulated signal transduction by the VEGFR-2 receptor. FASEB J. 21, 915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Oh H., Takagi H., Otani A., Koyama S., Kemmochi S., Uemura A., Honda Y. (2002) Selective induction of neuropilin-1 by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): A mechanism contributing to VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 383–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu Y., Yuan L., Mak J., Pardanaud L., Caunt M., Kasman I., Larrivée B., Del Toro R., Suchting S., Medvinsky A., Silva J., Yang J., Thomas J. L., Koch A. W., Alitalo K., Eichmann A., Bagri A. (2010) Neuropilin-2 mediates VEGF-C-induced lymphatic sprouting together with VEGFR3. J. Cell Biol. 188, 115–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pajusola K., Aprelikova O., Pelicci G., Weich H., Claesson-Welsh L., Alitalo K. (1994) Signalling properties of FLT4, a proteolytically processed receptor tyrosine kinase related to two VEGF receptors. Oncogene 9, 3545–3555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]