Background: G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) modulate a plethora of physiological processes.

Results: The determination of 38 ligand/receptor contacts enabled the evidence-based modeling of a GPCR structure.

Conclusion: The proposed GPCR structure assumes four interaction clusters with its ligand, which adopts a vertical binding mode.

Significance: Elucidating the structure of GPCRs is central to their understanding and has several implications, e.g. rational drug design.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Chemical Biology, Chemical Modification, Computer Modeling, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Homology Modeling, Molecular Docking, Peptide Interactions, Photoaffinity Labeling, Protein Structure

Abstract

Breakthroughs in G protein-coupled receptor structure determination based on crystallography have been mainly obtained from receptors occupied in their transmembrane domain core by low molecular weight ligands, and we have only recently begun to elucidate how the extracellular surface of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) allows for the binding of larger peptide molecules. In the present study, we used a unique chemoselective photoaffinity labeling strategy, the methionine proximity assay, to directly identify at physiological conditions a total of 38 discrete ligand/receptor contact residues that form the extracellular peptide-binding site of an activated GPCR, the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. This experimental data set was used in homology modeling to guide the positioning of the angiotensin II (AngII) peptide within several GPCR crystal structure templates. We found that the CXC chemokine receptor type 4 accommodated the results better than the other templates evaluated; ligand/receptor contact residues were spatially grouped into defined interaction clusters with AngII. In the resulting receptor structure, a β-hairpin fold in extracellular loop 2 in conjunction with two extracellular disulfide bridges appeared to open and shape the entrance of the ligand-binding site. The bound AngII adopted a somewhat vertical binding mode, allowing concomitant contacts across the extracellular surface and deep within the transmembrane domain core of the receptor. We propose that such a dualistic nature of GPCR interaction could be well suited for diffusible linear peptide ligands and a common feature of other peptidergic class A GPCRs.

Introduction

The structural basis of GPCR3 function has been the focus of intense academic and industrial research efforts in view of their tremendous potential as validated drug targets. For years, the only high resolution crystal structure available was that of bovine rhodopsin (1), which was a critical initial step toward a molecular understanding of these receptors. New advances in the determination of the crystal structures of several members of the class A GPCR family occupied by either low molecular weight molecules (2–9) or cyclic peptide and peptidomimetic (10–14) antagonists have led to remarkable insights. Those insights notwithstanding, little is known about the respective involvement of the remarkably divergent extracellular domains and of the more conserved TMD of GPCRs in the formation of a binding site for agonist peptides.

Contrary to more experimentally manageable soluble target proteins, GPCRs are intrinsic membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize without extensive engineering (15). Hence, more accessible methods for addressing GPCR structures in their physiological environment would be required to assess the dynamic nature of those proteins that cannot be captured by the static snapshots provided by crystallography. Furthermore, recent community-wide modeling surveys demonstrated that one of the most challenging aspects of GPCR structure prediction is to accurately assess ligand interactions with receptor extracellular residues (16, 17). These reports highlight the need for experimental data that can be used to further refine GPCR homology models.

In the present study, we utilized a unique chemoselective photoaffinity labeling strategy, the methionine proximity assay (see Fig. 1a), to collect such data on a class A peptidergic GPCR, AT1R (see Fig. 1c), bound to its cognate AngII peptide agonist (see Fig. 1b) (18). A ligand bearing the receptor-reactive p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (Bpa) photoprobe is preferentially incorporated into introduced methionine residues of target protein only when located in its immediate surroundings (19). Unambiguous identification of the incorporation site is directly achieved by a highly specific chemical proteolysis reaction. For this purpose, a Bpa scan was performed through the AngII peptide sequence and applied to a single point-mutated receptor template (i.e. a Met scan), AT1R-N111G, which has a much more tolerant structure-activity relationship than AT1R-WT. This allowed us to systematically identify the discrete ligand/receptor contact residues that constitute the extracellular ligand-binding site of AT1R for AngII. These methionine proximity assay (MPA)-derived parameters were used as molecular distance restraints in homology modeling with several GPCR crystal structure templates to deduce an experimentally based structure of the AngII-liganded AT1R. The receptor was probed in cell membranes at physiological conditions, thus enabling the characterization of the dynamic nature of the ligand-stabilized receptor conformations.

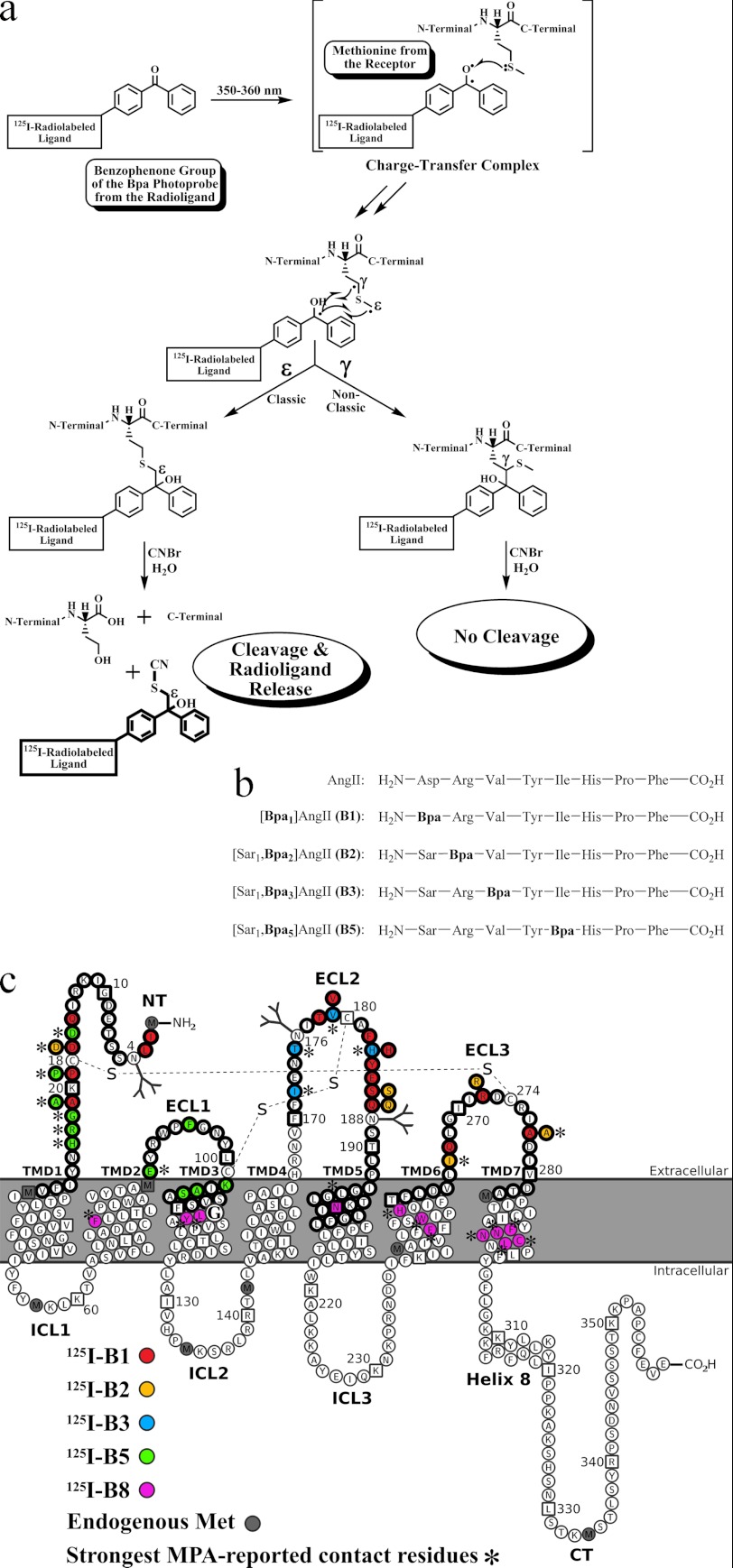

FIGURE 1.

a, MPA (59). Following the binding of the Bpa-substituted ligand with its target, the benzophenone group of the Bpa photoprobe is photoactivated at 350–360 nm to generate a reactive triplet biradical ketone intermediate (19). This photoactivated intermediate may then be rapidly and selectively quenched by a charge transfer complex (60) with a side chain of a Met residue within 3–6 Å (19, 59) in the target to produce a covalent bond between the ligand and the target. The electron transfer quench is more than 104-fold quicker for Met than toward other residues such as Ala for example; it results in an increased incorporation yield of the Bpa photoprobe into Met residues (61, 62). Hence, the charge transfer complex accounts for the strong photochemical selectivity to Met of the Bpa photoprobe. Direct identification of the Bpa incorporation within iteratively mutated Met residues is achieved by a highly specific CNBr-mediated proteolysis reaction (63). Depending on the Bpa regiochemistry of reaction with Met residues, the CNBr proteolysis yields two different pathways. The classical ϵ-pathway of proteolysis (64) generates receptor fragments issued from the C-terminal hydrolysis of Met and more importantly a radioligand methyl isothiocyanate derivative release issued from the hydrolysis of the Cγ–S bond of the Met side chain. This radioligand release indicates that the Bpa photoprobe of the radioligand is covalently cross-linked to the Cϵ of a Met residue in close vicinity. On the other hand, the non-classical γ-pathway of proteolysis (65) is refractory to CNBr hydrolysis at that particular photolabeled Met and thus does not produce radioligand release. In the case where no Met residue is in close vicinity of the Bpa, the photoprobe will photolabel other residues of the target structure protein, e.g. in the case of AT1R and 125I- B8, residues Phe293 and Asn294 (66). CNBr treatment of the resulting photolabeled adducts generates receptor fragments issued from C-terminal cleavage of the different endogenous Met residues without any radioligand release. Contrary to nitrene- or carbene-generating photoprobes, the Bpa presents an extremely low reactivity toward water molecules; this is particularly valuable for the study of hydrophilic receptor domains (67–69). Finally, the 125I radioisotope is used for SDS-PAGE autoradiographic detection of photolabeled complexes, CNBr products of proteolysis, and radioligand release. b, primary amino acid structure of the AngII peptide and of the photoreactive analogues used in this study. The Bpa photoprobe is indicated in bold within the name and sequence of the peptide. For photoaffinity labeling, each photoreactive analogue was radiolabeled at Tyr4 with the 125I radioisotope (not illustrated). c, AT1R-N111G secondary structure and MPA-reported contact residues. Met-mutated residues are represented by bold circles, whereas MPA-identified ligand/receptor contact residues are represented in bold circles of the corresponding color that refer to the appropriate photoreactive radioanalogue. The strongest MPA-reported contact residues that compose the different extracellular clusters are indicated by *. Endogenous Met residues are represented by bold black M in gray circles and squares. The N111G mutation is indicated in TMD3 by a bigger circle and font. Squares indicate 10-residue increments. The disulfide bridges and putative N-glycosylation are also shown. CT, C terminus; ICL, intracellular loop.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All organic chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Starting materials and reagents for the peptide syntheses were from Novabiochem. The Bpa photoprobe amino acid was from Chem-Impex International Inc. (Wood Dale, IL). IODO-GEN iodination reagent (1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3R,6R-diphenylglycoluril) was from Pierce. Na125I was from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences. Solvents and all inorganic chemicals were from Fisher Scientific.

Synthesis and Radiolabeling of the Photoreactive Radioanalogues

125I-[Bpa1]AngII (125I-B1), 125I-[Sar1,Bpa2]AngII (125I-B2), 125I-[Sar1,Bpa3]AngII (125I-B3), and 125I-[Sar1,Bpa5]AngII (125I-B5) were synthesized as described previously (20).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kits as described by Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Mutants were generated using human AT1R-N111G cDNA subcloned into the HindIII-XbaI sites of the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.0 (Invitrogen) as a template. Sets of forward and reverse oligonucleotides were constructed and used to introduce a single Met mutation at diverse positions of the receptor. Site-directed mutations were then confirmed by automated DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Preparation

COS-7 cell culture and preparation were conducted as described previously (20). Transient transfections were performed using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (18 μl/100-mm dish) and plasmid DNA (6 μg/100-mm dish) as described by Roche Applied Science.

Photoaffinity Labeling Experiments

COS-7 cell membranes transiently expressing the Met mutant AT1Rs (50–100 μg of total protein) were photolabeled and partially purified to remove free radioligands from the photolabeled receptor complexes as described previously (20). The partially purified photolabeled complexes were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Under these conditions, we typically recovered at least 70% of the initial radioactivity.

Specific CNBr-promoted Proteolysis of Met Residues

The partially purified photolabeled receptor complexes (0.1–1 ng containing 3–15 nCi) were treated with CNBr, and the products of proteolysis were analyzed as described previously (20). CNBr is particularly toxic and was handled in a fume hood.

Binding Affinity Assay

Equilibrium dissociation binding constant (Ki) values were determined by a heterologous competition binding assay using 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]AngII as tracer and transiently transfected COS-7 cell membranes as described previously (20). The values of maximal specific binding of the ligand (Bmax) were assessed using Ki values and a protein standard curve as described previously (21).

Inositol 1-Monophosphate Production Assay

COS-7 cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates (Corning, Corning, NY; 5,000 cells/well) and transiently transfected using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (1.5 μl/well) and plasmid DNA (0.5 μg/well) as described by Roche Applied Science. To determine basal (vehicle) and stimulated (1 × 10−6 m final concentration of AngII or photoreactive analog) inositol 1-monophosphate production the IP-One HTRF assay (Terbium) kit was used as described by Cisbio (Bedford, MA). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate and normalized for receptor expression levels. FRET fluorescence readouts were performed with a Tecan Infinite M1000 premium Quad4 Monochromator.

Homology Modeling

The homology models were generated using the primary sequence of human AT1R (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot accession code P30556) in which we had inserted the N111G mutation and were based on the crystal structures of the bovine rhodopsin (Protein Data Bank code 1L9H), the human β2-adrenergic receptor (Protein Data Bank code 2RH1), and the human CXCR4 (Protein Data Bank code 3OE0). The rhodopsin- and CXCR4-based models were generated using the LOMETS server (22). The β2-adrenergic receptor-based model was generated with using the MODELLER module within the InsightII software suite (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). For this specific model, the ECL2 was manually built for the MPA-reported contacts of 125I-B3 to be in an α-helical fold facing the binding site and rotated for the putative glycosylations of residue Asn176 and Asn188 to clear the binding site entrance. The sequence alignments for the TMD were carried out based on the most conserved residue of each TMD. The solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of the AngII molecule (Protein Data Bank code 1N9V) was used to dock the ligand. The AngII C terminus was first positioned within the receptor core formed by the TMDs 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 as suggested by previous data (21, 23–25). The N terminus was positioned to accommodate the spatially grouped clusters of MPA-reported contact residues for 125I-B2, 125I-B3, and 125I-B5. All figures were created using PyMOL software. The molecular dynamics simulations were performed as described in detail in the supplemental data.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The GROMACS software suite (26) running on a desktop computer (Intel Core-i7 2.67-GHz processor, 12 GB of RAM, Ubuntu 10.04 OS) was used to perform energy minimization and a molecular dynamics simulation of the AT1R-N111G·AngII complex. The MPA-reported contact residues were quantified according to both direct count of gel band radioactivity and densitometric analysis as reported previously (25). The strongest MPA-reported contacts for each 125I-AngII analogue were used as molecular distance restraints and implemented in the topology file using r0 = 0 Å, r1 = 7 Å, and r2 = 12 Å between the Cβ atoms of the corresponding residues with a force constant of 3,000 kJ/mol/nm2. More specifically, AngII Asp1 was restrained to Thr178, Glu185, Arg272, and Ala277. AngII Arg2 was restrained to Asp17, Ile266, and Arg272. AngII Val3 was restrained to His183. AngII Ile5 was restrained to Asp16, Pro19, Ala21, Gly22, Arg23, His24, and Glu91. AngII Phe8 was restrained to Phe77, Leu112, Tyr113, Phe249, Trp253, His256, Phe293, Asn294, Asn295, Cys296, and Leu297. The backbone heavy atoms of the TMD were position-restrained with a force constant of 1,000 kJ/mol/nm2. The intra- and extracellular loops, the C- and N-terminal ends, and the side chains of the receptor were unrestrained and free to move like the AngII peptide. The Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations with all atom (OPLS/AA) force field with the GBSA implicit solvent model was used. Energy minimization was performed using one step of steepest descent algorithm every 100 steps of conjugate gradient algorithm until the energy converged to machine precision. This was followed by a 1-ns molecular dynamics simulation during which the system was gradually heated to 310 K over the first 500 ps of the simulation. The last frame of each simulation was energy-minimized, and the PROCHECK server assessed the quality of all the models (26). At least 95% of the residues were in the most favored regions or additional allowed regions.

RESULTS

MPA Analysis of the AT1 Met Mutant Receptors

Previous MPA investigations with 125I-[Sar1,Bpa8]AngII (125I-B8) addressed the TMD core of AT1R (Fig. 1c) (21, 23–25). In the present MPA study, we assessed the extracellular surface by use of the photoreactive radioanalogues 125I-B1, 125I-B2, 125I-B3, and 125I-B5 with the aim of deciphering the interaction between AT1R and AngII. Of the 101 Met mutant AT1R-N111G receptors produced for the present study, 10 were refractory to AngII binding and photoaffinity labeling. The 91 remaining mutants were photolabeled in a specific manner with at least one of the four photoreactive radioanalogues, which were recently reported to label the respective extracellular domains (20). Following partial purification to remove free radioligand, the 125I-B1-, 125I-B2-, 125I-B3-, and 125I-B5-photolabeled receptor complexes were found to migrate as broad glycoprotein bands with an apparent molecular mass >30 kDa, whereas no dissociable radioligand was detected (Figs. 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a, lane 1 for a representative example). This was also shown earlier with 125I-B1, 125I-B3, and 125I-B8 (20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28).

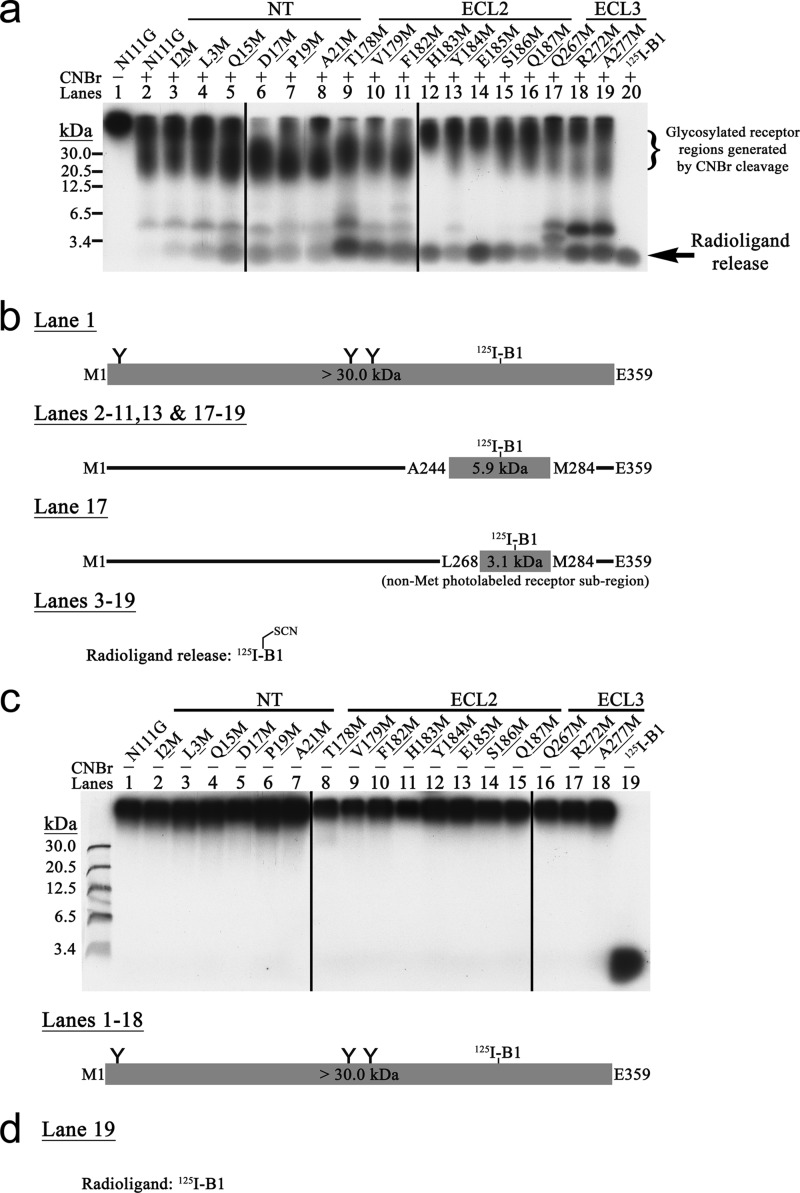

FIGURE 2.

a, MPA analysis of AT1R-N111G using 125I-B1. 125I-B1-photolabeled complexes were incubated in the absence (see lane 1 for a representative example) or presence (lanes 2–19) of CNBr and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. b, schematic CNBr fragmentation pattern of the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. 125I-B1-photolabeled receptor regions together with their calculated molecular masses that include the mass of 125I-B1 are represented. The three putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated by Y. All the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs displayed a radioligand release band that co-migrated below the 3.4-kDa protein standard marker with the corresponding free photoreactive radioanalogue that was run in parallel. c, CNBr proteolysis specificity for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. The specificity of CNBr-promoted chemical cleavage of Met residues was assessed by incubation of the various 125I-B1-photolabeled complexes under the same reaction conditions as for a but without CNBr (lanes 1–18). These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. d, schematic pattern without CNBr for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. Refer to b for key. None of the 125I-B1 MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs in the absence of CNBr exhibited a radioligand release band of apparent molecular mass below 3.4 kDa, attesting to the CNBr-promoted proteolysis specificity.

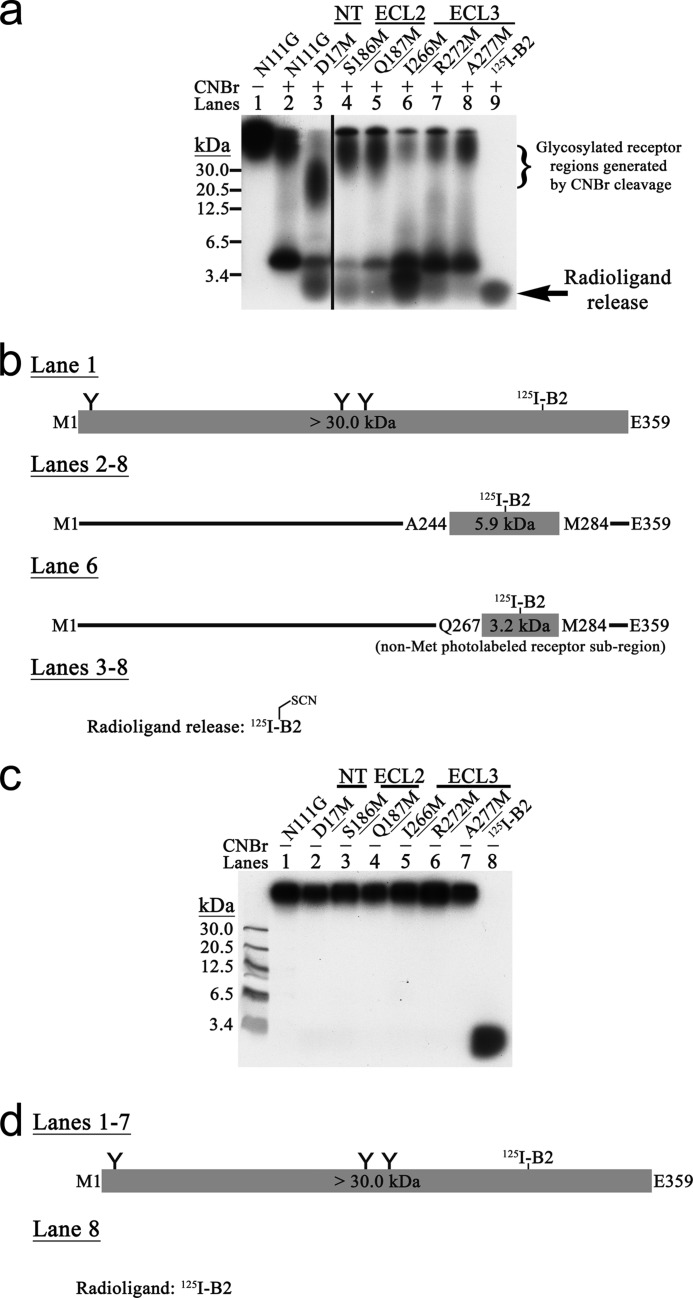

FIGURE 3.

a, MPA analysis of AT1R-N111G using 125I-B2. 125I-B2-photolabeled complexes were incubated in the absence (see lane 1 for a representative example) or presence (lanes 2–8) of CNBr and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. b, schematic CNBr fragmentation pattern of the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. 125I-B2-photolabeled receptor regions together with their calculated molecular masses that include the mass of 125I-B2 are represented. The three putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated by Y. All the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs displayed a radioligand release band that co-migrated below the 3.4-kDa protein standard marker with the corresponding free photoreactive radioanalogue that was run in parallel. c, CNBr proteolysis specificity for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. The specificity of CNBr-promoted chemical cleavage of Met residues was assessed by incubation of the 125I-B2-photolabeled complexes under the same reaction conditions as for a but without CNBr (lanes 1–7). These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. d, schematic pattern without CNBr for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. Refer to b for key. None of the 125I-B2 MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs in the absence of CNBr exhibited a radioligand release band of apparent molecular mass below 3.4 kDa, attesting to the CNBr-promoted proteolysis specificity.

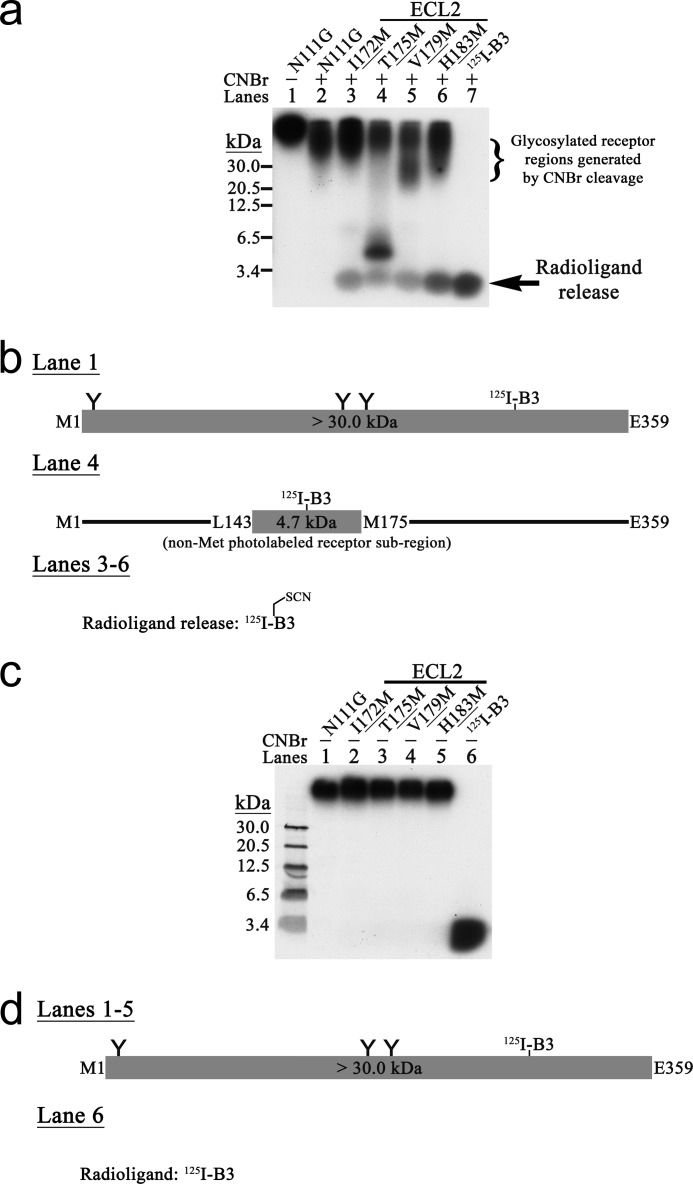

FIGURE 4.

a, MPA analysis of AT1R-N111G using 125I-B3. 125I-B3-photolabeled complexes were incubated in the absence (see lane 1 for a representative example) or presence (lanes 2–6) of CNBr and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. b, schematic CNBr fragmentation pattern of the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. 125I-B3-photolabeled receptor regions together with their calculated molecular masses that include the mass of 125I-B3 are represented. The three putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated by Y. All the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs displayed a radioligand release band that co-migrated below the 3.4-kDa protein standard marker with the corresponding free photoreactive radioanalogue that was run in parallel. c, CNBr proteolysis specificity for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. The specificity of CNBr-promoted chemical cleavage of Met residues was assessed by incubation of the 125I-B3-photolabeled complexes under the same reaction conditions as for a but without CNBr (lanes 1–5). These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. d, schematic pattern without CNBr for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. Refer to b for key. None of the 125I-B3 MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs in the absence of CNBr exhibited a radioligand release band of apparent molecular mass below 3.4 kDa, attesting to the CNBr-promoted proteolysis specificity.

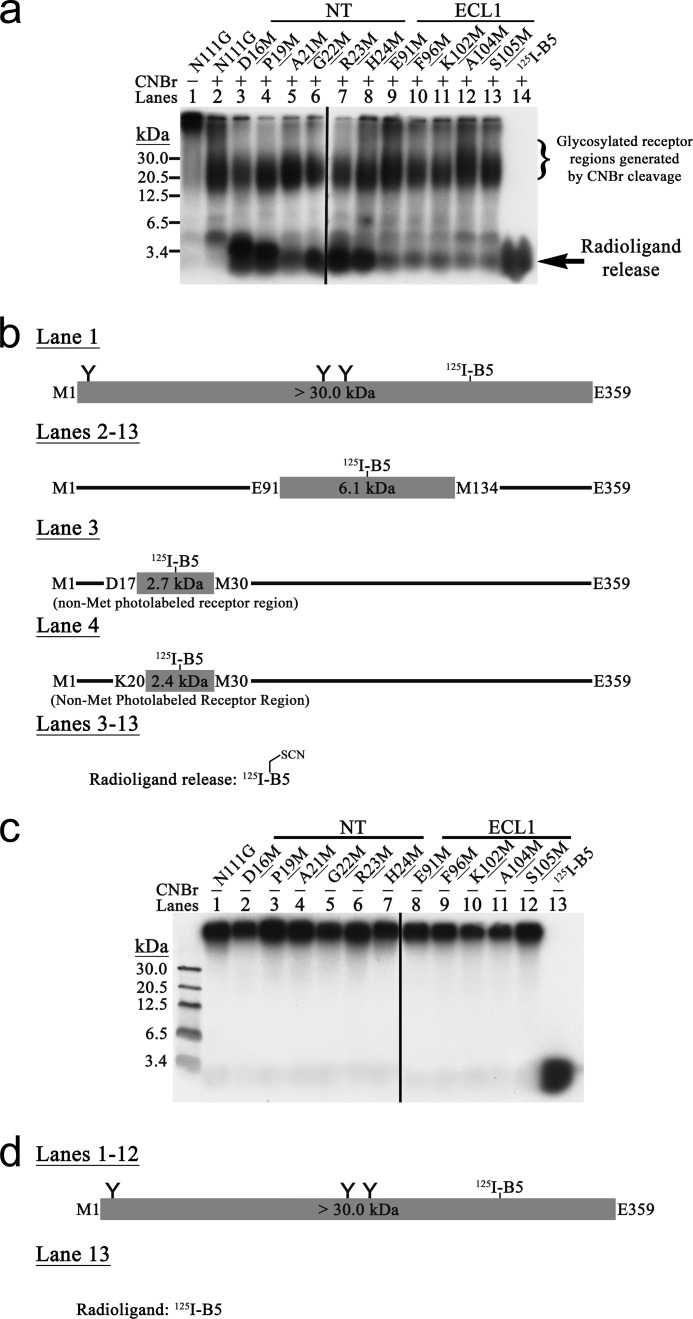

FIGURE 5.

a, MPA analysis of AT1R-N111G using 125I-B5. 125I-B5-photolabeled complexes were incubated in the absence (see lane 1 for a representative example) or presence (lanes 2–13) of CNBr and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. b, schematic CNBr fragmentation pattern of the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. 125I-B5-photolabeled receptor regions together with their calculated molecular masses that include the mass of 125I-B5 are represented. The three putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated by Y. All the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs displayed a radioligand release band that co-migrated below the 3.4-kDa protein standard marker with the corresponding free photoreactive radioanalogue that was run in parallel. c, CNBr proteolysis specificity for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. The specificity of CNBr-promoted chemical cleavage of Met residues was assessed by incubation of the 125I-B5-photolabeled complexes under the same reaction conditions as for a but without CNBr (lanes 1–12). These results are representative of at least three independent experiments. d, schematic pattern without CNBr for the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. Refer to b for key. None of the 125I-B5 MPA-positive Met mutant AT1Rs in the absence of CNBr exhibited a radioligand release band of apparent molecular mass below 3.4 kDa, attesting to the CNBr-promoted proteolysis specificity.

Of the 219 photolabeled complexes produced, 38 MPA-positive Met mutants were identified by CNBr treatment because their fragmentation patterns in 16.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels were different from that of the non-Met-mutated AT1R-N111G. An additional radioactive band corresponding to radioligand release was observed for all MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G. It migrated below the 3.4-kDa protein standard marker and co-migrated with the free photoreactive radioanalogue that was run in parallel (Figs. 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a, last lane of each). 125I-B1 (Fig. 2a, lanes 3–19) and 125I-B2 (Fig. 3a, lanes 3–8) identified 17 and six MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G receptors, respectively, in the NT, ECL2, and ECL3. 125I-B3 (Fig. 4a, lanes 3–6) identified four MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G receptors in the ECL2, whereas 125I-B5 (Fig. 5a, lanes 3–13) identified 11 MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G receptors in both the NT and ECL1. Furthermore, no endogenous Met contact was reported by the MPA analysis of AT1R-N111G (Figs. 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a, lane 2). The proteolysis specificity of the CNBr treatment for all the MPA-positive Met mutant AT1R-N111G receptors was also assessed in the absence of this reagent (Figs. 2–5, c and d).

For a very few of the MPA-positive Met mutant receptors, the typically observed fragmentation patterns of AT1R-N111G were faint or even absent. Given the Met selectivity of Bpa, this was an expected and commonly observed consequence of the monopolization of the photolabeling process by Met (21, 23, 24). For instance, the insertion of Met into ECL2 suppressed 125I-B1 photolabeling of ECL3, which contains the Ala244–Met284 region (Fig. 2a, lanes 12 and 14–16, ∼6 kDa). Conversely, additional bands were observed in the fragmentation patterns of some MPA-positive Met mutant receptors. However, this was also to be expected because of concomitant non-Met photolabeling in the vicinity of an introduced Met. The non-Met photolabeling produced a lower molecular mass band in the fragmentation pattern due to CNBr cleavage of the introduced Met. For instance, the 125I-B1-photolabeled N111G,Q267M receptor fragmentation pattern had an additional ∼4-kDa band corresponding to non-Met photolabeling in the Leu268–Met284 subregion (Fig. 2a, lane 17). The same observation and reasoning also applies to the 125I-B2-photolabeled N111G,I266M receptor fragmentation pattern, which displayed photolabeling of a non-Met residue in the Gln267–Met284 subregion (Fig. 3a, lane 6). The 125I-B3-photolabeled N111G,T175M receptor fragmentation pattern had an additional ∼5-kDa band and displayed predominantly non-Met photolabeling in the non-glycosylated Leu143–Met175 subregion (Fig. 4a, lane 4). This band was also present in the fragmentation pattern of AT1R-WT (27). The 125I-B5-photolabeled N111G,D16M and N111G,P19M receptor fragmentation patterns both had radioligand release bands together with additional overlapping ∼4-kDa bands corresponding to non-Met photolabeling in the Asp17–Met30 and Lys20–Met30 subregions, respectively (Fig. 5a, lanes 3 and 4).

Pharmacological Properties of Relevant Met Mutant Receptors

The evaluation of both the Ki and Bmax values and the inositol 1-monophosphate production levels assessed the conservation of the structural and functional integrity of the 38 MPA-positive Met mutant receptors. These receptors all displayed Ki and Bmax values for the respective photoreactive radioanalogues that were similar to those of natural AngII for both WT and AT1R-N111G (supplemental Table 1). They also had constitutively active inositol 1-monophosphate levels similar to those of AT1R-N111G, whereas photoreactive radioanalogues stimulated levels similar to those of both WT and AT1R-N111G (supplemental Table 2).

The 10 Met mutant receptors (e.g. K12M, I14M, K20, Y92M, W94M, G97M, I193M, L197M, F204M, and D278M) that were refractory to photolabeling were equally assessed for Ki and Bmax. None demonstrated detectable binding affinity activity, suggesting that they possessed non-measurable receptor expressions or binding affinities.

Homology Modeling

Three different GPCR crystal structures were used for homology modeling: both the prototypal bovine rhodopsin and β2-adrenergic receptor along with CXCR4, which is phylogenetically even closer to AT1R (29). Constitutive activity is conferred to these three receptors by mutating exactly the same residue as in AT1R-N111G (30–32).

A total of 51 ligand/receptor contact residues were considered in the process of positioning the AngII molecule inside the ligand-binding site, which are the herein reported 38 contacts along with the 13 contacts derived from the previous studies of all the TMDs with 125I-B8 (21, 23–25). Nevertheless, because all these contact residues do not present the same photoaffinity labeling intensity at physiological temperature, we focused primarily on the more intense results to generate the several models. The strongest MPA-reported contact residues for 125I-B2, 125I-B3, and 125I-B5 along with results derived from the previous studies of all the TMDs with 125I-B8 (21, 23–25) were thus found to spatially group into four defined AngII interaction clusters within the receptor structures. Results from 125I-B1 were not strong contact residues and were spread across the surface of AT1R; this is in line with the observed dynamic behavior of the GPCR extracellular surface (33).

For the most part, cluster I (shown in orange in Figs. 1c and 6) consists of 125I-B2 residues Asp17 in the NT that is adjacent to the Cys18-Cys274 disulfide bridge only common to both AT1R and CXCR4, Ile266 in TMD6, and Arg272 in ECL3. Cluster II (shown in blue in Figs. 1c and 6) is on the middle portion of the ECL2 solely and encompasses all the 125I-B3 residues, Ile172, Thr175, Val179, and His183. These residues are all located on both sides of the ECL2 bridgehead of the Cys101-Cys180 disulfide bridge, which is >80% conserved among all GPCR families (34). Cluster III (shown in green in Fig. 1c and 6) is composed of 125I-B5 residues Asp16, Pro19, Ala21, Gly22, Arg23, and His24 in the NT that are all located on the proximal portion of the NT and adjacent to the Cys18-Cys274 non-conserved disulfide bridge, as well as Glu91 in TMD2. Cluster IV (shown in magenta in Figs. 1c and 6) is formed by 125I-B8 residues Phe77 in TMD2; Leu112 and Tyr113 in TMD3; Asn200 in TMD5; Phe249, Trp253, and His256 in TMD6; and Phe293, Asn294, Asn295, Cys296, and Leu297 in TMD7. These residues are all located deep in the ligand-binding site toward the middle of the TMD bundle.

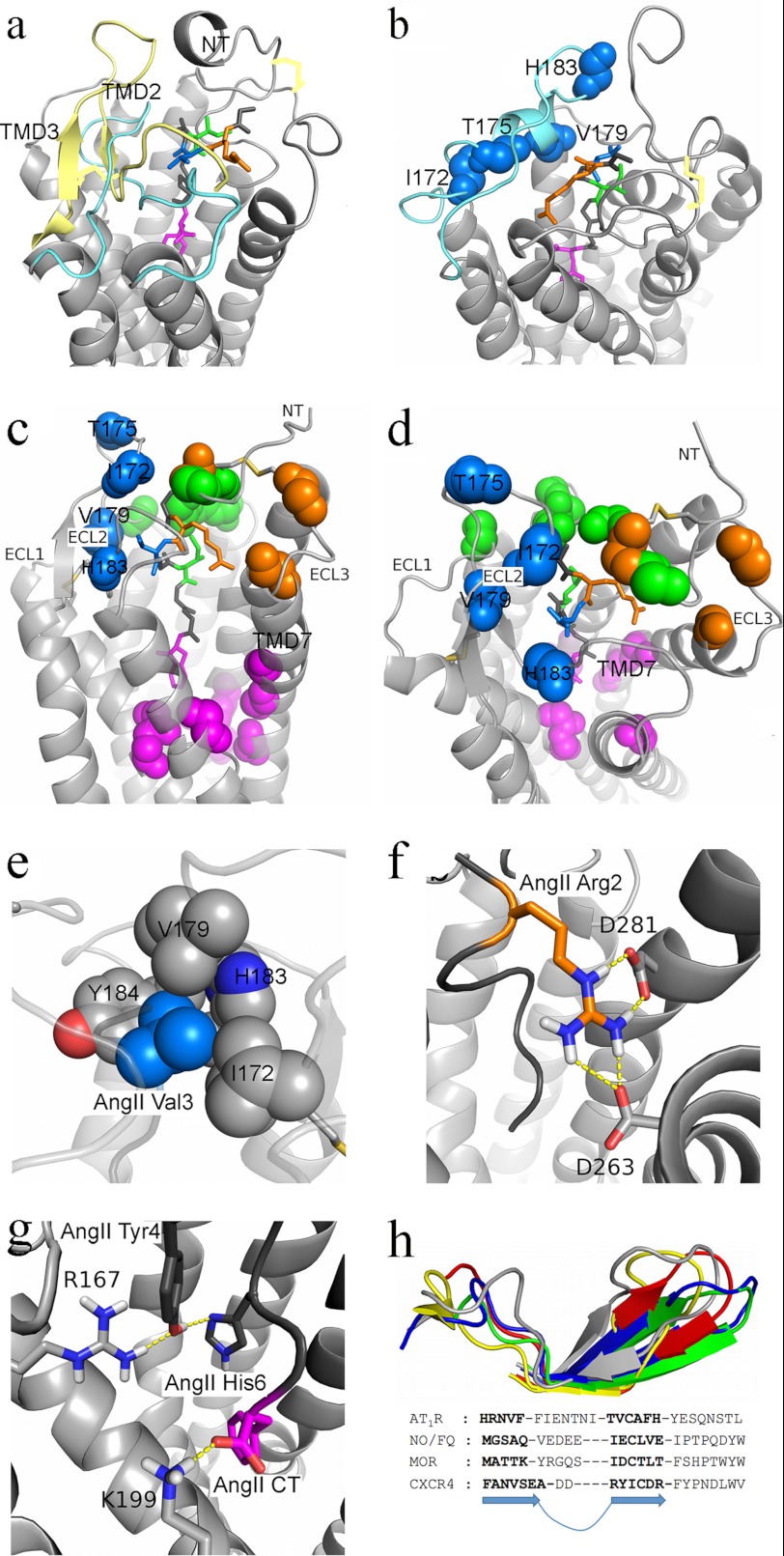

FIGURE 6.

Rhodopsin- (a) and β2-adrenergic receptor-based (b) models of AT1R are shown. The receptor backbone is shown in light gray. The disulfide bridges are shown as yellow sticks. The AngII ligand backbone is shown as gray sticks with residues 2, 3, 5, and 8 colored orange, blue, green, and magenta, respectively. The ECL2 of both the rhodopsin- and β2-adrenergic receptor-based models is shown in light blue, whereas the ECL2 from the CXCR4-based model is shown in light yellow for comparison. Backbone atoms of the MPA-reported hits of 125I-B3 are shown as blue spheres on the β2-adrenergic receptor-based model. c and d, CXCR4-based model of AT1R. The TMD view (c) shows the AngII binding mode, and the ECL view (d) shows the several clusters of interaction with AngII. Backbone atoms of the spatially clustered residues are shown in colored spheres. Cluster I and AngII position 2 are shown in orange, cluster II and AngII position 3 are shown in blue, cluster III and AngII position 5 are shown in green, and cluster IV and AngII position 8 are shown in magenta. e–g, interactions of the AT1R CXCR4-based structure with AngII. e, ECL2 residues Ile172, Val179, Ala181, His183, and Tyr184 (shown as gray spheres with nitrogen atom in dark blue and oxygen atom in red) of the AT1R form a hydrophobic interaction cluster with Val3 (shown as light blue sphere) of AngII. f, hydrogen bonding network of residue Asp281 and Asp263 with Arg2 of AngII. g, hydrogen bonding network of residue Arg167 with Tyr4 and His6 of AngII as well as of residue Lys199 with the carboxyl of Phe8 of AngII. h, structural comparison of the ECL2 from AT1R based on the CXCR4 template with that of the CXCR4 and some opioid receptors. The ECL2 of the AT1R as initially generated by the LOMETS server and after molecular dynamics simulation with AngII is shown in blue and gray, respectively. The ECL2 of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) and μ-opioid (MOR) receptors and that of CXCR4 are shown in yellow, red, and green, respectively. CT, C terminus.

Finally, the solution NMR structure of the AngII molecule (35) was actually very well adapted to satisfy the side chain locations and orientations suggested by these four clusters. The linear AngII C-terminal portion orients to the TMD core of AT1R, whereas the AngII midsequence portion resides at the extracellular domain/TMD interface, and the AngII N-terminal portion ends up at roughly the same height relative to the cell surface because of its almost corkscrew-like structure. Furthermore, positioning AngII at the center of the TMD core and orienting Arg2 toward the first cluster resulted in Val3 automatically facing the second cluster exactly as the MPA-reported contact residues suggested. From this position, Ile5 was slightly further away from the third cluster compared with the distances of both Arg2 and Val3 for their corresponding clusters. The AngII N terminus is positioned so that it can sustain extensive interaction across the receptor extracellular surface as suggested with 125I-B1.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, several molecular photoprobes, large scale protein mutagenesis, and homology modeling approaches were combined to identify 38 discrete residues of the AT1R extracellular surface that are involved in the formation of the AngII ligand-binding site. We previously reported that photoreactive AngII analogues substituted at positions 1, 2, 3, and 5 with either Bpa or aryldiazirine-based photoprobes all labeled exactly the same domains of the AT1R-binding site with only a single exception for analogues substituted in position 2, thus enabling the actual detailed MPA analysis of AT1R (20). Interestingly, an exhaustive literature survey on previously available mutagenesis data appears to corroborate these findings because nearly half of the actual ligand/receptor contact residues that we found in the NT (36), ECL1 (36–44), ECL2 (36, 41, 45–47), and ECL3 (36, 43, 44, 47–49) were postulated to be involved in ligand binding and receptor functions or were adjacent to such residues. The present study suggests that those mutated residues do not have an indirect influence on the ligand-binding site but instead may directly contact the bound ligand.

Recently, AT1R-N111G has been found to have a more tolerant structure-activity relationship than AT1R-WT for the photoprobe substitutions within the AngII octapeptide sequence, allowing the photoreactive radioanalogues 125I-B1, 125I-B2, 125I-B3, and 125I-B5 to bind with sufficient affinities for meaningful photoaffinity labeling investigations (20). The pharmacological properties of AT1R-N111G liganded by these same analogues were shown to be similar to those of AT1R-WT liganded by AngII. Moreover, the present (supplemental Tables 1 and 2) and the previous (21, 23, 24) studies demonstrate that the introduction of Met residues has in general a minimal impact on the pharmacological properties of AT1R. Hence, we used AT1R-N111G as a system model based on these similarities.

Although all three homology models of AT1Rs can house the AngII molecule within their binding site with careful positioning of the ligand and energy minimization, the important differences in the long ECL2 structures mean they do not all accommodate the MPA results and AngII binding equally well. Hence, the ECL2 structure and its interactions had a major impact for the validity of these models. Differences became apparent as we started positioning the AngII in the AT1R models prior to energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations.

On the rhodopsin-based model (Fig. 6a), the ECL2 is located lower and inside the ligand-binding site when compared with the other models. This renders the site considerably smaller, and significant steric clashes were inevitable for the initial ligand positioning prior to energy minimization. The subsequent energy minimizations and molecular dynamics simulations produced a lateral movement of ECL2 toward TMD2 and TMD3 as well as toward the extracellular space, which altogether significantly hampered AngII binding. As a consequence, the AngII molecule adopted an odd shape with Val3 being lower than Ile5 to accommodate the results on ECL2 and NT, respectively. A reporter-cysteine accessibility mapping study proposed previously that bound AT1R can adopt a lid conformation similar to that of ECL2 in rhodopsin and thus resulted in an ECL2 structure different from that actually suggested by our results (50). This discrepancy underlines the need for evaluating various templates with respect to experimental data.

On the β2-adrenergic receptor-based model (Fig. 6b), an α-helix within the ECL2 central region is held in the periphery of the ligand-binding site by the conserved TMD3/ECL2 disulfide bridge and enables accessibility to AngII. From a photoaffinity labeling perspective, this helix was suggested because 125I-B3 had revealed four discontinuous ECL2 contacts, namely residues Ile172, Thr175, Val179, and His183, and displayed an i + 3/i + 4 periodical helix sequence pattern of residue detection. Such a helical pattern could be compatible with the photolabeling of 125I-B3 on a narrow surface of an α-helix as obtained earlier during the MPA analysis of TMD6 of AT1R using 125I-B8 (21, 23). Although the model was compelling because of the possibility of having an α-helix in ECL2 for AT1R, the strongest MPA-reported contact residue for 125I-B3 is residue His183, which is the second most distant residue of 125I-B3 and thus does not favor such a strong contact. Moreover, the residues forming the putative and manually built ECL2 α-helix have a low propensity to form such a structure, and during the ensuing molecular dynamics simulation, this helix instability became apparent.

On the CXCR4-based structure (Fig. 6, c and d), a β-hairpin fold in ECL2 is positioned roughly above TMD3 and TMD4, projecting toward the extracellular space by the conserved TMD3/ECL2 disulfide bridge. This enables the 125I-B3 strongest residue, His183, to be located right in front of the AngII Val3, which is surrounded by the hydrophobic residues Ile172, Val179, Ala181, and Tyr184 and represents an energetically favorable environment (Fig. 6e) by comparison with both the rhodopsin- and β2-adrenergic receptor-based models. Moreover, the two glycosylations at residues Asn176 and Asn188 of the ECL2 extended outward from the ligand-binding site and appeared not to be involved in any direct interactions with AngII in agreement with previous results (51).

Besides the distinctive Cys18-Cys274 disulfide bridge, CXCR4 also shares with AT1R an insertion of 7–9 residues in ECL3 that makes the extracellular end of TMD7 two turns longer and allows hydrogen bonding between the AngII Arg2 and residue Asp281 (Fig. 6f), which was previously documented as being important for full agonism by AngII (47). Other contact residues derived from this structure were also of particular interest. The residue Arg167, which was previously proposed to be important for AngII binding (52), was found to interact with the AngII Tyr4 in a manner that is not influenced by the distance restraints imposed by the MPA results (Fig. 6g). Moreover, the AngII C terminus carboxylate formed a charged hydrogen bond with residue Lys199 as was reported previously (53, 54). This placed the AngII Phe8 close to residue Trp253, whose possible action as the “global toggle switch” during AT1R activation (55) could be linked to the presence of the AngII Phe8 through hydrophobic and π-stacking interactions.

Very recently, the crystal structures of the four opioid receptors (10, 11, 13, 14) were disclosed, enabling the comparison of the CXCR4-based AT1R model with these closely related peptidergic class A GPCRs. Not only are ECL2 domains of all the opioid receptors very similar in terms of conformation and position, but they also were found to be highly congruent to the ECL2 of the preferred AT1R structure (Fig. 6h). Furthermore, querying the I-TASSER server (56) to generate multiple template homology models of AT1R also suggests that the ECL2 adopts a β-strand conformation.

The present study offers a comprehensive view of the molecular structure of a class A GPCR in its active state that could explain how its extracellular surface topology accounts for the formation of a peptide-binding site. We found that the AT1R homology model based on the template of the peptidergic and phylogenetically close CXCR4 accommodated our experimental data much better than the other templates evaluated. Ligand/receptor contact residues were spatially grouped into defined interaction clusters with AngII. Such close homologs with more than 35% sequence identity in the TMD are likely to be amenable for accurate comparative homology modeling (57). The wide ranging contacts of those clusters appeared to outline a dualistic and novel nature of peptide/GPCR interaction where the bound AngII molecule adopts a somewhat vertical binding mode with its N terminus interacting across the extracellular surface and its C terminus interacting more deeply within the TMD core. At the surface of the receptor, a β-hairpin fold in ECL2 in conjunction with the extracellular disulfide bridges appeared to shape the entrance of the ligand-binding site by maintaining in close vicinity the residues of the extracellular domain that are important for AngII binding and functions. This could explain why these bridges have long been known to be critical for AT1R (58). Based on our results along with the recently disclosed crystal structures of the four opioid receptors, we suggest that such a receptor extracellular architecture and ligand binding mode could be well adapted for diffusible midsize peptide ligands and could represent a common feature of other class A GPCRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie-Reine Lefebvre for expert help and technical assistance, Dr. Brian J. Holleran for critical reading of the manuscript, and Philip Doudounne Boulais Fillion for broad ranging and often passionate discussions.

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grants MOP-69019 and MOP-13193 as well as Quebec Chapter of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Grant G-09-ES-3595 (to E. E.).

This manuscript is dedicated to Dr. Robert Schwyzer for his 92nd anniversary; the chemical biology approach to the AT1 receptor applied in this report was initiated by Robert Schwyzer more than 40 years ago.

This article contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- AT1

- angiotensin II type 1

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- MPA

- methionine proximity assay

- AT1R

- angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- AngII

- angiotensin II

- CXCR4

- CXC chemokine receptor type 4

- ECL

- extracellular loop

- Bpa

- p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine

- Sar

- sarcosine

- NT

- N terminus.

REFERENCES

- 1. Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Hori T., Behnke C. A., Motoshima H., Fox B. A., Le Trong I., Teller D. C., Okada T., Stenkamp R. E., Yamamoto M., Miyano M. (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haga K., Kruse A. C., Asada H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Shiroishi M., Zhang C., Weis W. I., Okada T., Kobilka B. K., Haga T., Kobayashi T. (2012) Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature 482, 547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimamura T., Shiroishi M., Weyand S., Tsujimoto H., Winter G., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Cherezov V., Liu W., Han G. W., Kobayashi T., Stevens R. C., Iwata S. (2011) Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature 475, 65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chien E. Y., Liu W., Zhao Q., Katritch V., Han G. W., Hanson M. A., Shi L., Newman A. H., Javitch J. A., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2010) Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science 330, 1091–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warne T., Serrano-Vega M. J., Baker J. G., Moukhametzianov R., Edwards P. C., Henderson R., Leslie A. G., Tate C. G., Schertler G. F. (2008) Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 454, 486–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaakola V. P., Griffith M. T., Hanson M. A., Cherezov V., Chien E. Y., Lane J. R., Ijzerman A. P., Stevens R. C. (2008) The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science 322, 1211–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rasmussen S. G., Choi H. J., Rosenbaum D. M., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Edwards P. C., Burghammer M., Ratnala V. R., Sanishvili R., Fischetti R. F., Schertler G. F., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2007) Crystal structure of the human β2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 450, 383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kruse A. C., Hu J., Pan A. C., Arlow D. H., Rosenbaum D. M., Rosemond E., Green H. F., Liu T., Chae P. S., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E., Weis W. I., Wess J., Kobilka B. K. (2012) Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 482, 552–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanson M. A., Roth C. B., Jo E., Griffith M. T., Scott F. L., Reinhart G., Desale H., Clemons B., Cahalan S. M., Schuerer S. C., Sanna M. G., Han G. W., Kuhn P., Rosen H., Stevens R. C. (2012) Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science 335, 851–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thompson A. A., Liu W., Chun E., Katritch V., Wu H., Vardy E., Huang X. P., Trapella C., Guerrini R., Calo G., Roth B. L., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2012) Structure of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor in complex with a peptide mimetic. Nature 485, 395–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Granier S., Manglik A., Kruse A. C., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K. (2012) Structure of the δ-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature 485, 400–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu B., Chien E. Y., Mol C. D., Fenalti G., Liu W., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Brooun A., Wells P., Bi F. C., Hamel D. J., Kuhn P., Handel T. M., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2010) Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science 330, 1066–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu H., Wacker D., Mileni M., Katritch V., Han G. W., Vardy E., Liu W., Thompson A. A., Huang X. P., Carroll F. I., Mascarella S. W., Westkaemper R. B., Mosier P. D., Roth B. L., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2012) Structure of the human κ-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature 485, 327–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manglik A., Kruse A. C., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Mathiesen J. M., Sunahara R. K., Pardo L., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K., Granier S. (2012) Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 485, 321–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker M. (2010) Making membrane proteins for structures: a trillion tiny tweaks. Nat. Methods 7, 429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Michino M., Abola E., GPCR Dock 2008 participants, Brooks C. L., 3rd, Dixon J. S., Moult J., Stevens R. C. (2009) Community-wide assessment of GPCR structure modelling and ligand docking: GPCR Dock 2008. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 455–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kufareva I., Rueda M., Katritch V., Stevens R. C., Abagyan R. (2011) Status of GPCR modeling and docking as reflected by community-wide GPCR Dock 2010 assessment. Structure 19, 1108–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Gasparo M., Catt K. J., Inagami T., Wright J. W., Unger T. (2000) International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 415–472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dormán G., Prestwich G. D. (1994) Benzophenone photophores in biochemistry. Biochemistry 33, 5661–5673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fillion D., Lemieux G., Basambombo L. L., Lavigne P., Guillemette G., Leduc R., Escher E. (2010) The amino-terminus of angiotensin II contacts several ectodomains of the angiotensin II receptor AT1. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2063–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clément M., Martin S. S., Beaulieu M. E., Chamberland C., Lavigne P., Leduc R., Guillemette G., Escher E. (2005) Determining the environment of the ligand binding pocket of the human angiotensin II type I (hAT1) receptor using the methionine proximity assay. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27121–27129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu S., Zhang Y. (2007) LOMETS: a local meta-threading-server for protein structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 3375–3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clément M., Chamberland C., Pérodin J., Leduc R., Guillemette G., Escher E. (2006) The active and the inactive form of the hAT1 receptor have an identical ligand-binding environment: an MPA study on a constitutively active angiotensin II receptor mutant. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 26, 417–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clément M., Cabana J., Holleran B. J., Leduc R., Guillemette G., Lavigne P., Escher E. (2009) Activation induces structural changes in the liganded angiotensin II type 1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26603–26612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arsenault J., Cabana J., Fillion D., Leduc R., Guillemette G., Lavigne P., Escher E. (2010) Temperature dependent photolabeling of the human angiotensin II type 1 receptor reveals insights into its conformational landscape and its activation mechanism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 990–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boucard A. A., Wilkes B. C., Laporte S. A., Escher E., Guillemette G., Leduc R. (2000) Photolabeling identifies position 172 of the human AT1 receptor as a ligand contact point: receptor-bound angiotensin II adopts an extended structure. Biochemistry 39, 9662–9670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laporte S. A., Boucard A. A., Servant G., Guillemette G., Leduc R., Escher E. (1999) Determination of peptide contact points in the human angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1) with photosensitive analogs of angiotensin II. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fredriksson R., Lagerström M. C., Lundin L. G., Schiöth H. B. (2003) The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 1256–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W. B., Navenot J. M., Haribabu B., Tamamura H., Hiramatu K., Omagari A., Pei G., Manfredi J. P., Fujii N., Broach J. R., Peiper S. C. (2002) A point mutation that confers constitutive activity to CXCR4 reveals that T140 is an inverse agonist and that AMD3100 and ALX40–4C are weak partial agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24515–24521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Robinson P. R., Cohen G. B., Zhukovsky E. A., Oprian D. D. (1992) Constitutively active mutants of rhodopsin. Neuron 9, 719–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zuscik M. J., Porter J. E., Gaivin R., Perez D. M. (1998) Identification of a conserved switch residue responsible for selective constitutive activation of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3401–3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bokoch M. P., Zou Y., Rasmussen S. G., Liu C. W., Nygaard R., Rosenbaum D. M., Fung J. J., Choi H. J., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Puglisi J. D., Weis W. I., Pardo L., Prosser R. S., Mueller L., Kobilka B. K. (2010) Ligand-specific regulation of the extracellular surface of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 463, 108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karnik S. S., Gogonea C., Patil S., Saad Y., Takezako T. (2003) Activation of G-protein-coupled receptors: a common molecular mechanism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 14, 431–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tzakos A. G., Bonvin A. M., Troganis A., Cordopatis P., Amzel M. L., Gerothanassis I. P., van Nuland N. A. (2003) On the molecular basis of the recognition of angiotensin II (AII). NMR structure of AII in solution compared with the x-ray structure of AII bound to the mAb Fab131. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hjorth S. A., Schambye H. T., Greenlee W. J., Schwartz T. W. (1994) Identification of peptide binding residues in the extracellular domains of the AT1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30953–30959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miura S., Kiya Y., Kanazawa T., Imaizumi S., Fujino M., Matsuo Y., Karnik S. S., Saku K. (2008) Differential bonding interactions of inverse agonists of angiotensin II type 1 receptor in stabilizing the inactive state. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 139–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin S. S., Boucard A. A., Clément M., Escher E., Leduc R., Guillemette G. (2004) Analysis of the third transmembrane domain of the human type 1 angiotensin II receptor by cysteine scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51415–51423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perlman S., Costa-Neto C. M., Miyakawa A. A., Schambye H. T., Hjorth S. A., Paiva A. C., Rivero R. A., Greenlee W. J., Schwartz T. W. (1997) Dual agonistic and antagonistic property of nonpeptide angiotensin AT1 ligands: susceptibility to receptor mutations. Mol. Pharmacol. 51, 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Monnot C., Bihoreau C., Conchon S., Curnow K. M., Corvol P., Clauser E. (1996) Polar residues in the transmembrane domains of the type 1 angiotensin II receptor are required for binding and coupling. Reconstitution of the binding site by co-expression of two deficient mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1507–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Noda K., Saad Y., Kinoshita A., Boyle T. P., Graham R. M., Husain A., Karnik S. S. (1995) Tetrazole and carboxylate groups of angiotensin receptor antagonists bind to the same subsite by different mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2284–2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Groblewski T., Maigret B., Nouet S., Larguier R., Lombard C., Bonnafous J. C., Marie J. (1995) Amino acids of the third transmembrane domain of the AT1A angiotensin II receptor are involved in the differential recognition of peptide and nonpeptide ligands. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 209, 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Costa-Neto C. M., Miyakawa A. A., Pesquero J. B., Oliveira L., Hjorth S. A., Schwartz T. W., Paiva A. C. (2002) Interaction of a non-peptide agonist with angiotensin II AT1 receptor mutants. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 80, 413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Costa-Neto C. M., Miyakawa A. A., Oliveira L., Hjorth S. A., Schwartz T. W., Paiva A. C. (2000) Mutational analysis of the interaction of the N- and C-terminal ends of angiotensin II with the rat AT1A receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 130, 1263–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takezako T., Gogonea C., Saad Y., Noda K., Karnik S. S. (2004) “Network leaning” as a mechanism of insurmountable antagonism of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor by non-peptide antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15248–15257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamano Y., Ohyama K., Kikyo M., Sano T., Nakagomi Y., Inoue Y., Nakamura N., Morishima I., Guo D. F., Hamakubo T., Inagami T. (1995) Mutagenesis and the molecular modeling of the rat angiotensin II receptor (AT1). J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14024–14030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Feng Y. H., Noda K., Saad Y., Liu X. P., Husain A., Karnik S. S. (1995) The docking of Arg2 of angiotensin II with Asp281 of AT1 receptor is essential for full agonism. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12846–12850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Correa S. A., Zalcberg H., Han S. W., Oliveira L., Costa-Neto C. M., Paiva A. C., Shimuta S. I. (2002) Aliphatic amino acids in helix VI of the AT1 receptor play a relevant role in agonist binding and activity. Regul. Pept. 106, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Correa S. A., França L. P., Costa-Neto C. M., Oliveira L., Paiva A. C., Shimuta S. I. (2002) Relevant role of Leu265 in helix VI of the angiotensin AT1 receptor in agonist binding and activity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 80, 426–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Unal H., Jagannathan R., Bhat M. B., Karnik S. S. (2010) Ligand-specific conformation of extracellular loop-2 in the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16341–16350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lanctôt P. M., Leclerc P. C., Escher E., Leduc R., Guillemette G. (1999) Role of N-glycosylation in the expression and functional properties of human AT1 receptor. Biochemistry 38, 8621–8627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yan L., Holleran B. J., Lavigne P., Escher E., Guillemette G., Leduc R. (2010) Analysis of transmembrane domains 1 and 4 of the human angiotensin II AT1 receptor by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2284–2293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Noda K., Saad Y., Karnik S. S. (1995) Interaction of Phe8 of angiotensin II with Lys199 and His256 of AT1 receptor in agonist activation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28511–28514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yamano Y., Ohyama K., Chaki S., Guo D. F., Inagami T. (1992) Identification of amino acid residues of rat angiotensin II receptor for ligand binding by site directed mutagenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 187, 1426–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schwartz T. W., Frimurer T. M., Holst B., Rosenkilde M. M., Elling C. E. (2006) Molecular mechanism of 7TM receptor activation—a global toggle switch model. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 46, 481–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Y. (2007) Template-based modeling and free modeling by I-TASSER in CASP7. Proteins 69, Suppl. 8, 108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Katritch V., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2012) Diversity and modularity of G protein-coupled receptor structures. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 17–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ohyama K., Yamano Y., Sano T., Nakagomi Y., Hamakubo T., Morishima I., Inagami T. (1995) Disulfide bridges in extracellular domains of angiotensin II receptor type IA. Regul. Pept. 57, 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rihakova L., Deraët M., Auger-Messier M., Pérodin J., Boucard A. A., Guillemette G., Leduc R., Lavigne P., Escher E. (2002) Methionine proximity assay, a novel method for exploring peptide ligand-receptor interaction. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 22, 297–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marciniak B., Bobrowski K., Hug G. L. (1993) Quenching of triplet states of aromatic ketones by sulfur-containing amino acids in solution. Evidence for electron transfer. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 11937–11943 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bobrowski K., Marciniak B., Hug G. L. (1992) 4-Carboxybenzophenone-sensitized photooxidation of sulfur-containing amino acids. Nanosecond laser flash photolysis and pulse radiolysis studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10279–10288 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Marciniak B., Hug G. L., Bobrowski K., Kozubek H. (1995) Mechanism of 4-carboxybenzophenone-sensitized photooxidation of methionine-containing dipeptides and tripeptides in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 13560–13568 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kaiser R., Metzka L. (1999) Enhancement of cyanogen bromide cleavage yields for methionyl-serine and methionyl-threonine peptide bonds. Anal. Biochem. 266, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kage R., Leeman S. E., Krause J. E., Costello C. E., Boyd N. D. (1996) Identification of methionine as the site of covalent attachment of a p-benzoyl-phenylalanine-containing analogue of substance P on the substance P (NK-1) receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 25797–25800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sachon E., Bolbach G., Chassaing G., Lavielle S., Sagan S. (2002) Cγ H2 of Met174 side chain is the site of covalent attachment of a substance P analog photoactivable in position 5. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50409–50414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pérodin J., Deraët M., Auger-Messier M., Boucard A. A., Rihakova L., Beaulieu M. E., Lavigne P., Parent J. L., Guillemette G., Leduc R., Escher E. (2002) Residues 293 and 294 are ligand contact points of the human angiotensin type 1 receptor. Biochemistry 41, 14348–14356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tate J. J., Persinger J., Bartholomew B. (1998) Survey of four different photoreactive moieties for DNA photoaffinity labeling of yeast RNA polymerase III transcription complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 1421–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Deseke E., Nakatami Y., Ourisson G. (1998) Intrinsic reactivities of amino acids toward photoalkylation with benzophenone—a study preliminary to photolabelling of the transmembrane protein glycophorin A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 243–251 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Weber P. J., Beck-Sickinger A. G. (1997) Comparison of the photochemical behavior of four different photoactivatable probes. J. Pept. Res. 49, 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]