Background: The protein kinase Mst1 is activated by oxidative stress, but substrates of oxidatively activated Mst1 are not known.

Results: Mst1 interacts with Prdx1, an enzyme that regulates cellular H2O2, and inhibits Prdx1 by phosphorylating it at two sites.

Conclusion: Mst1 sustains a pro-oxidative state by inactivating Prdx1.

Significance: These results help us understand how Mst1 exerts its tumor suppressor activity.

Keywords: Peroxiredoxin, Protein Kinases, Redox Signaling, Signal Transduction, Tumor Suppressor Gene

Abstract

The serine/threonine protein kinases Mst1 and Mst2 can be activated by cellular stressors including hydrogen peroxide. Using two independent protein interaction screens, we show that these kinases associate, in an oxidation-dependent manner, with Prdx1, an enzyme that regulates the cellular redox state by reducing hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. Mst1 inactivates Prdx1 by phosphorylating it at Thr-90 and Thr-183, leading to accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in cells. These results suggest that hydrogen peroxide-stimulated Mst1 activates a positive feedback loop to sustain an oxidizing cellular state.

Introduction

Mammalian sterile twenty (Mst)1 and Mst2 are closely related serine/threonine-specific protein kinases that have an important and highly conserved role in tumor suppression in metazoa (1–3). In many organisms, Mst1/2 regulates organ size, chiefly through effects on cell proliferation and survival (1, 2, 4). The cellular functions of Mst1 are not fully known, in large part due to our limited information regarding the regulation and substrates of this kinase.

We know very little about how Mst1/2 are regulated, particularly in mammalian cells. In Drosophila, the Mst1 ortholog Hippo is thought to relay signals from cytoskeletal proteins such as Expanded, Kibra, and Merlin, polarity proteins such as Crumbs, Lgl, and atypical PKC, as well as by atypical cadherin proteins such as Fat, but the biochemical links between these proteins, especially in mammalian cells, remain elusive (5). In mammalian cells, Msts are also positively regulated by the phosphatase PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) (6, 7) and by binding partners such as RASSF1A (8–10) and in flies, they are negatively regulated by a protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) protein phosphatase complex, Striatin interacting phosphatase and kinase (STRIPAK) (11).

In mammalian cells, early studies established that Mst1 is strongly activated by oxidative stress stimuli, such as H2O2 (12, 13). How such oxidative stress activates Mst1 is unknown. Levels of cellular H2O2 are maintained by a variety of oxidase and reductase systems. The latter include glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and peroxiredoxins (14–17). Interestingly, peroxiredoxin-1 (Prdx1),3 a cysteine-containing, highly conserved enzyme that reduces H2O2 to H2O and O2, was recently found to interact with Mst1 (18). Knockdown of Prdx1 was reported to be associated with loss of Mst1 activity, suggesting that Prdx1 participates in the activation of Mst1 by H2O2.

Among the known targets of Mst1/2 are cardiac troponin I, histones H2B and H2AX, the protein kinase large tumor suppressor (LATS) (as well as Mob1, a binding partner of LATS), the transcription factor FOXO3, and the adaptor protein WW45 (13, 19–23). Mst1-catalyzed phosphorylation of these proteins affects cell proliferation, growth, survival, and motility, and together likely accounts for a large portion of the tumor-suppressive activity of Mst1.

In this work, we sought to better define the role of Mst1 in cells under oxidant stress. To do so, we carried out two independent screens to identify Mst1 interactors: a yeast two-hybrid screen, with LexA-Mst1 as bait, and a co-immunoprecipitation screen, using doubly tagged Mst1 as bait in basal or oxidatively stressed mammalian cells. Both screens identified Prdx1 as a prominent interactor, especially in cells grown under conditions of oxidative stress. Furthermore, we also established that Mst2, in addition to Mst1, interacts with Prdx1 in an H2O2-dependent manner, that Mst1 phosphorylates, and thereby inactivates Prdx1 in vitro, and that these events increase H2O2 levels in cells. These findings establish a potential feedback stimulation system to sustain an oxidizing state in cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents, Antibodies, and Cell Culture

Antibodies to Mst1 and Prdx1 were obtained from Abcam, antibodies to actin, HA tag, phospho-Thr, and Mst2 were from Cell Signaling Technologies, antibody to phospho-H2AX (Ser-139) was from Millipore, and Myc tag antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-HA-agarose was purchased from Sigma, and Strep-Tactin beads were from IBA Technologies. 6-carboxy-2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) and PDGF-BB were from Invitrogen. Recombinant Mst1 was purchased from ProQinase and recombinant Prdx1, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, and NADPH were from Sigma. PreScission protease and glutathione-Sepharose beads were obtained from GE Healthcare. Blasticidin was from Calbiochem, and hygromycin was from Cellgro. Prdx1 siRNA was obtained from Dharmacon.

Yeast Two-hybrid Screen

Human Mst1 cDNA from pJ3H-Mst1 (24) was cloned in-frame to lexA into pEG202-92, a high copy yeast vector containing HIS3 as the selectable marker and lexA under control of the constitutive ADH1 promoter (25). This construct and pSH18–34 (which contains eight lexA operators fused to a lacZ reporter) and a human fetal brain cDNA library in pJG4–5 (a high copy yeast vector containing a human cDNA library fused to an acidic activation domain and under control of the inducible GAL1 promoter) were used to transform yeast strain EGY48 (ura3 trp1 his3 lexA operator, LEU2) (25). Approximately 4 × 105 independent transformants were obtained and screened. Transformants were grown in minimal medium with galactose as the carbon source. Interaction was assessed by two methods: β-galactosidase activity and the ability of transformants to grow in the absence of leucine. The library inserts from individual yeast colonies were retrieved by colony PCR and sequenced. These inserts were purified and retransformed, along with EcoRI/XhoI-digested pJG4–5, into yeast to reconfirm the phenotype.

Tandem Affinity Purification

Mst1 cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA5/FRT/TO/SH/GW destination vector (obtained from M. Gstaiger (26)) by gateway cloning to generate a tetracycline-inducible SH-tagged (streptavidin-binding peptide and HA tag) version of Mst1. Flp-In HEK-293 cells (Invitrogen) were co-transfected with Mst1-pcDNA5/FRT/TO/SH/GW and a Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid to allow integration of Mst1 in Flp-In HEK-293 genome. After 2 days of transfection, cells were selected in 100 μg/ml hygromycin for 2–3 weeks to generate stable cell line (supplemental Fig. S1A). Mst1 expression was induced by 1 μg/ml tetracycline and was confirmed by HA antibody (supplemental Fig. S1B).

To identify Mst1 interactors, double affinity purification was performed as described (26). Briefly, Mst1-Flp-In 293 cells were grown to 90% confluence in ten 15-cm dishes. Mst1 expression was induced by the addition of 500 ng/ml tetracycline for 4 h. Mst1 protein complex was purified in two steps using strep-Tactin beads (IBA Technologies) and anti-HA-agarose (supplemental Fig. S1C). The purified complex was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, and the peptides were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility (Harvard Medical School).

Co-immunoprecipitation

WT-Mst1, KD-Mst1 (kinase dead), and WT-Mst2 were cloned in pCMV6 vector to append a Myc tag to the N terminus. WT-Prdx1 and C52S/C173S Prdx1 were cloned in pCDNA5/FRT/TO to tag them with HA tag. These constructs were transfected in HEK-293 cells. After 48 h, cells were lysed, and the proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA-agarose overnight at 4 °C. The agarose beads were then washed four times with lysis buffer and analyzed by immunoblot.

RNA Interference

The siRNA duplexes targeted to Mst1 comprised a mixture of four different oligonucleotides (SMARTpool). Equal amounts of sense and antisense RNA oligonucleotides were mixed and annealed according to the manufacturer's instructions. HEK-293 cells were transfected with 10 nm siRNA for Mst1 or the control siRNA duplex using Lipofectamine siRNA max reagent for 72 h.

Expression and Purification of WT and Mutant Prdx1

Prdx1 was subcloned into a Prdx1-pcDNA5/FRT/TO/SH/GW (SH-Prdx1) mammalian expression vector. Alanine and aspartic acid mutants of Prdx1 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis, and the mutated Prdx1 was cloned in pDEST15 bacterial expression vector by gateway cloning or by conventional cloning into pGEX-4T. The WT and mutant Prdx1 plasmids were transformed in BL21 cells, and proteins were purified by standard purification methods using glutathione-agarose.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Recombinant Prdx1 was incubated with recombinant Mst1 in kinase buffer containing 20 μm ATP and 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 2× SDS sample buffer and boiling for 10 min.

Immunoprecipitate Kinase Assay

Mst1 immunoprecipitates were incubated with 2 μg of myelin basic protein in kinase buffer containing 20 μm ATP and 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 2× SDS sample buffer and boiling for 10 min.

Identification of Prdx1 Phosphorylation Sites

Recombinant Prdx1 (2 μg) was phosphorylated by recombinant Mst1 (400 ng) by incubation in kinase buffer in the presence of 20 μm ATP for 30 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the Prdx1 band was excised and analyzed by LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer at the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility (Harvard Medical School).

Purification of Phosphorylated Prdx1

Recombinant Prdx1 (500 μg) was phosphorylated by recombinant Mst1 (20 μg) by incubation in kinase buffer in the presence of 1 mm ATP for 2 h. After phosphorylation, the reaction mixture was dialyzed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and 20 mm NaCl to remove residual ATP. Phosphorylated Prdx1 and unphosphorylated Prdx1 were separated by applying the dialyzed solution to a MonoQ-Sepharose column equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5). The proteins were eluted by increasing concentration of NaCl and were collected in 500-μl fractions. The fractions were analyzed for unphosphorylated and phosphorylated proteins by immunoblot analysis with anti-phosphothreonine antibodies.

Peroxidase Assay

For peroxidase assays, the GST tag was removed by incubating GST-Prdx1 (WT and mutant) bound to the glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare). Peroxidase activity of Prdx1 was determined by coupling H2O2 reduction by Prdx1 to NADPH oxidation. Briefly, H2O2 (100 μm) was added as a substrate in a reaction mixture containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.0), 5 μg of thioredoxin, 50 nm thioredoxin reductase, 0.2 mm NADPH, and 2 μg of Prdx1. To calculate Prdx1 activity, the rate of NADPH oxidation was measured as a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm at 30 °C.

Construction of Prdx1−/− Stable Cell Lines

Immortalized Prdx1−/− MEFs (27) were infected with retrovirus containing empty vector, WT-Prdx1, T183A-Prdx1, or T183D-Prdx1. After 2 days of infection, cells were selected with 4 μg/ml puromycin for 2 weeks to generate Prdx1−/−EV, Prdx1−/−WT, Prdx1−/−T183A, and Prdx1−/−T183D MEFs.

Intracellular Hydrogen Peroxide

Intracellular H2O2 was measured with a fluorescent dye, carboxy-H2DCFDA. MEFs were grown to 40–50% confluence in a 6-cm dish. They were serum-starved overnight and were stimulated with platelet-derived growth factor (5 ng/ml) for 10 min in minimum Eagle's medium without phenol red. They were then washed with PBS and stained with carboxy-H2DCFDA at a final concentration of 10 μm. Cells were incubated with carboxy-H2DCFDA at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS and scraped in 500 μl of ice-cold PBS. Carboxy-H2DCFDA fluorescence was determined for 10,000 events/sample using flow cytometer. All the samples were run in triplicate.

RESULTS

Mst1 and Mst2 Associate with Prdx1

We used human Mst1 fused to the DNA-binding domain of LexA as bait and a human fetal brain cDNA library fused to the B42 activation domain as prey. Seventy-one Leu (+)/lacZ (+) clones (CC1–CC71) expressing putative Mst1 interactors were selected. Inserts from these putative interactors was recovered, recloned into pJG4–5, and retested for interaction with Mst1 in yeast. Twenty-one inserts, representing 16 distinct cDNAs, conferred growth on Leu (−)/galactose plates (supplemental Table S1). The most frequently recovered inserts (4 of 21) encoded partial or full-length versions of Prdx1, an enzyme that reduces H2O2 in cells (28). Other notable interactors found in this screen were WW45, Mob1, and Mst1 itself, which is known to homodimerize (29), as well as another enzyme involved in redox regulation, manganese superoxide dismutase (30, 31). Other interactors represented proteins that are frequent false positives in yeast two-hybrid screens (ubiquitin, ribosomal proteins, AAA ATPase), proteins that seem unrelated to Mst1 function, or uncharacterized open reading frames.

As a second, independent screen for potential Mst1 interactors, we performed tandem affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry analysis (supplemental Fig. S1A). We transfected 293-Flp-in cells, which allow for defined, single site integration into the genome of HEK-293 cells with a suitable vector (26) that confers tetracycline-regulated control of Mst1 expression. Mst1 was doubly epitope-tagged at its N terminus with consecutive streptavidin and hemagglutinin (HA) tags to allow for tandem affinity purification (commonly referred to as “tap tagging”). We chose a 4-h induction time for tagged Mst1 because it closely matched endogenous Mst1 levels of expression (Fig. 1D). Because Mst1 is known to be activated in cells grown under conditions of oxidative stress, we purified protein complexes from cells under non-stress or oxidative stress conditions using a sequence of streptavidin and anti-HA-agarose column chromatography. In Mst1-complexes purified from non-stressed cells, mass spectrometry analysis revealed a number of known Mst1 interactors, including WW45, Rassf1, Rassf2 (9, 32, 33) and, interestingly, Mst2, implying the existence of Mst1/2 heterodimers in cells. Thus, our tap-tagging procedure was effective in capturing many known Mst1 interactions from cells cultured under basal conditions. We then compared the identity of Mst1 interactors from non-stressed cells versus those identified from cells cultured under conditions of oxidative stress. Extracts were prepared from control and H2O2-treated Mst1-Flp-In 293 cells, and purification of Mst1 and associated proteins was carried out. Although all interactors identified in non-stressed cells were also identified in cells grown under oxidative stress, Prdx1 uniquely was found to interact with Mst1 only in cells cultured under oxidative stress conditions (supplemental Tables S2 and Table S3). As Mst1 is known to play a role in regulating liver size and tumorigenesis (1–3), we further confirmed this redox-regulated Mst1/Prdx1 interaction in a second cell line, human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells (supplemental Table S4).

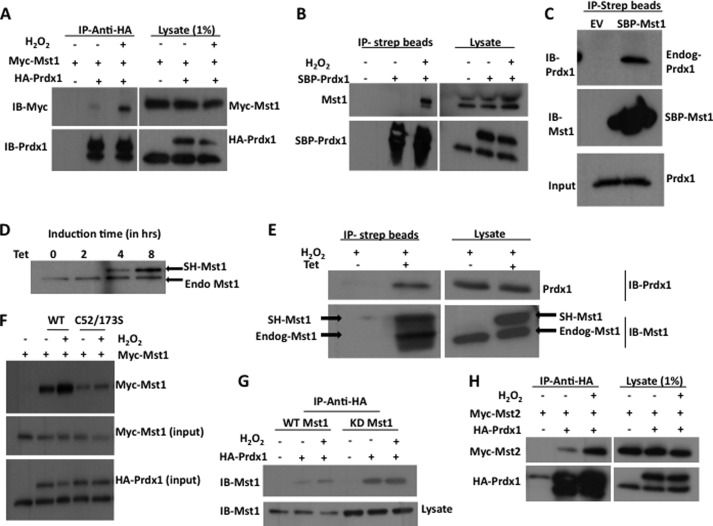

FIGURE 1.

Both Mst1 and Mst2 undergo stress-inducible interaction with Prdx1. A, HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated combinations of plasmids. Cells were stimulated with H2O2 for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HA antibodies. The resulting immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-Myc antibodies. B, HEK-293 cells were transfected either with EV or with SBP-Prdx1. Cells were stimulated with H2O2 for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with streptavidin beads (IP-strep beads). The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Mst1 antibodies. C, HEK-293 cells were transfected either with EV or with SBP-Mst1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with streptavidin beads. The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Prdx1 antibodies. Endog-Prdx1, endogenous Prdx1. D, time-dependent SH-Mst1 expression. Cells were treated with 500 ng/ml tetracycline for different time points as indicated. Expression of SH-Mst1 and endogenous Mst1 (Endo Mst1) was monitored by immunoblotting using anti-Mst1 antibodies. E, Mst1-Flp-In 293 cells were treated with 500 ng/ml tetracycline (Tet) for 4 h followed by treatment with H2O2 for 30 min. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with streptavidin beads, and the resulting immunoprecipitated proteins were probed with anti-Prdx1 antibodies. F and G, HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated combination of plasmids. Cells were stimulated with H2O2. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and probed with Mst1 antibodies. C52/173S, C52S/C173S. H, HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated combinations of plasmids. Cells were stimulated with H2O2 for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. The resulting immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Mst2 antibodies.

To validate the finding of our tandem affinity purification and mass spectrometry analysis, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with Myc-Mst1 and HA-Prdx1 and treated with H2O2. HA-Prdx1 was then immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibodies. Myc-Mst1 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with HA-Prdx1, and this interaction was strongly induced by H2O2 (Fig. 1A). We also confirmed interaction between overexpressed Mst1 and endogenous Prdx1 and vice versa (Fig. 1, B and C). To further confirm this interaction, we induced our Mst1-Flp-In 293 cells with tetracycline for 4 h to express SH-Mst1 at levels equivalent to endogenous Mst1 and stimulated these cells with H2O2. We used streptavidin beads to pull down SH-Mst1 and probed the protein complex with anti-Prdx1 antibodies. Detection of Prdx1 in the protein complex confirmed interaction between endogenous Prdx1 and SH-Mst1 expressed at endogenous levels (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, the streptavidin-captured protein complex also contained endogenous Mst1, perhaps as a result of dimerization between SH-Mst1 and endogenous Mst1. The association between Prdx1 and Mst1 is direct, as shown by the interaction of recombinant GST-Mst1 and recombinant Prdx1 in vitro (supplemental Fig. S2). To further characterize this association, we investigated whether the catalytic activities of Mst1 and Prdx1 are required for binding. We co-expressed Myc-Mst1 with WT-Prdx1 or C52S/C173S Prdx1, a catalytically inactive form of Prdx1 (Fig. 1F). Forty-eight hours after transfection, we treated these cells with 100 μm H2O2 for 30 min and immunoprecipitated Prdx1. We found that WT-Prdx1, but not the C52S/C173S Prdx1 mutant, interacted with Mst1 in an oxidative stress-inducible manner (Fig. 1F). Next, we co-transfected cells with Prdx1 and WT-Mst1 or Mst1 K59R, a kinase-dead form of Mst1 (29). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that the kinase activity of Mst1 was not required for interaction with Prdx1; in fact, when corrected for differences in protein expression, kinase-dead Mst1 showed slightly increased binding to Prdx1 (Fig. 1G). We also tested whether Mst2, which is similar to Mst1 in structure and function, can associate with Prdx1. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that Mst2 also displayed oxidative stress-inducible interaction with Prdx1 (Fig. 1H).

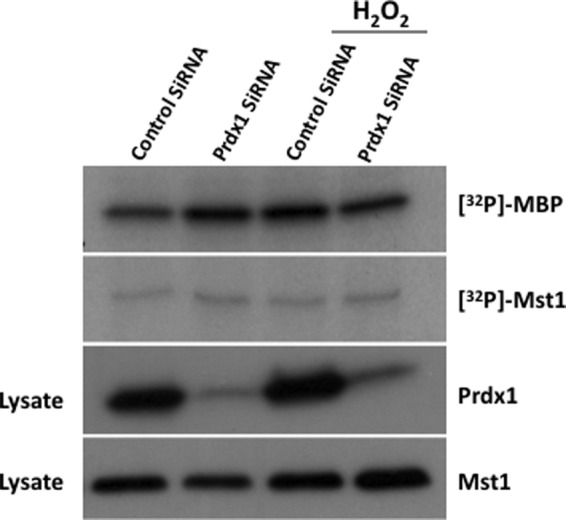

Mst1 Activity Is Not Dependent on Prdx1

To determine whether Prdx1 is required for efficient Mst1 activation by H2O2, we knocked down Prdx1 in HEK-293 cells and assayed for activity of endogenous Mst1 in cells grown under basal or oxidant-stressed conditions. Prdx1 was efficiently knocked-down by a pool of siRNAs, and reduced Prdx1 levels did not affect endogenous Mst1 expression (Fig. 2). Mst1 kinase activity was slightly elevated by Prdx1 knockdown in non-stressed cells, but this effect was not noted in cells treated with H2O2. Thus, we found that Mst1 kinase activity was not dramatically altered by loss of Prdx1.

FIGURE 2.

Prdx1 is not required for Mst1 activation by H2O2. HEK-293 cells were transfected with control or Prdx1-specific siRNA pools. Seventy-two h after transfection, the cells were exposed to H2O2 for 30 min. The cells were then lysed, and Mst1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Mst1 antibodies. Cell lysates were analyzed for expression of Prdx1 and Mst1, and the Mst1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed for kinase activity using myelin basic protein (MBP) as substrate.

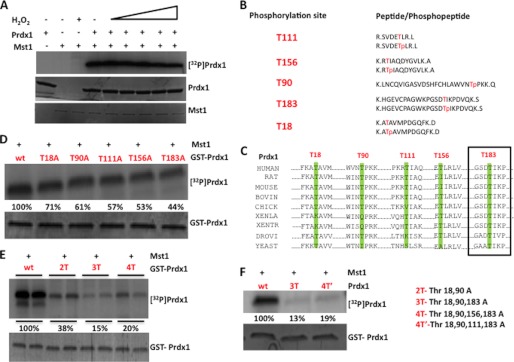

Mst1 Phosphorylates Prdx1

Having confirmed the interaction between Mst1 and Prdx1, we asked whether Prdx1 can serve as a Mst1 substrate. We performed an in vitro kinase assay using recombinant Prdx1 and Mst1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. This experiment showed that Prdx1 was phosphorylated by Mst1 and that the level of phosphorylation was not affected by hydrogen peroxide in vitro (Fig. 3A). Next, we sought to identify the site(s) at which Mst1 phosphorylates Prdx1. Recombinant Prdx1 was subjected to in vitro phosphorylation by Mst1, and the phosphorylation sites of Prdx1 were identified by mass spectrometry. We identified five phosphorylation sites: Thr-18, Thr-90, Thr-111, Thr-156, and Thr-183 (Fig. 3B), with the highest apparent stoichiometry of phosphorylation at Thr-90 and Thr-183 (data not shown). Notably, the Thr-90 and Thr-183 sites closely match the optimal consensus sequence for Mst substrates, as defined by peptide arrays (34). We also aligned the sequences of these phosphosites from Prdx1 from different species to assess the degree to which they are conserved. We found that of the five identified phosphorylation sites, only Thr-183 is invariant from yeast to man (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Prdx1 is phosphorylated by Mst1 predominantly at Thr-18, Thr-90, and Thr-183. A, recombinant Prdx1 (2 μg) was subjected to in vitro kinase assay with Mst1 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and increasing concentration of H2O2. Phosphorylated Prdx1 and phospho-Mst1 were visualized by autoradiography. B, mass spectrometry results showing all the phosphorylation sites identified for Prdx1 and the corresponding phosphopeptides. C, sequence alignment of Prdx1 from different species. D–F, both single and combination alanine mutants of Prdx1 were incubated with Mst1 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE; phosphorylated Prdx1 was visualized by autoradiography, and total Prdx1 by Coomassie Blue stain.

To determine the predominant site(s) at which Mst1 phosphorylates Prdx1, we individually mutated these five threonine residues to alanine, alone or in tandem. The mutant proteins were produced in and purified from bacteria and then subjected to in vitro kinase assay with Mst1. All five single site mutants showed slight changes in phosphorylation when compared with WT Prdx1, but none showed significant reduction (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that under routine in vitro conditions, Mst1 phosphorylates Prdx1 at several sites. To further analyze the phosphorylation sites, we made combination mutants of Prdx1, termed 2T (T18A/T90A), 3T (T18A/T90A/T183A), 4T (T18A/T90A/T156A/T183A), and 4T′ (T18A/T90A/T111A/T183A). When subjected to in vitro kinase assay with Mst1, the 3T and 4T Prdx1 mutants showed the most significant reduction in phosphorylation when compared with WT-Prdx1, suggesting that Thr-18, Thr-90, and Thr-183 are the predominant sites that are phosphorylated by Mst1 in vitro (Fig. 3, E and F).

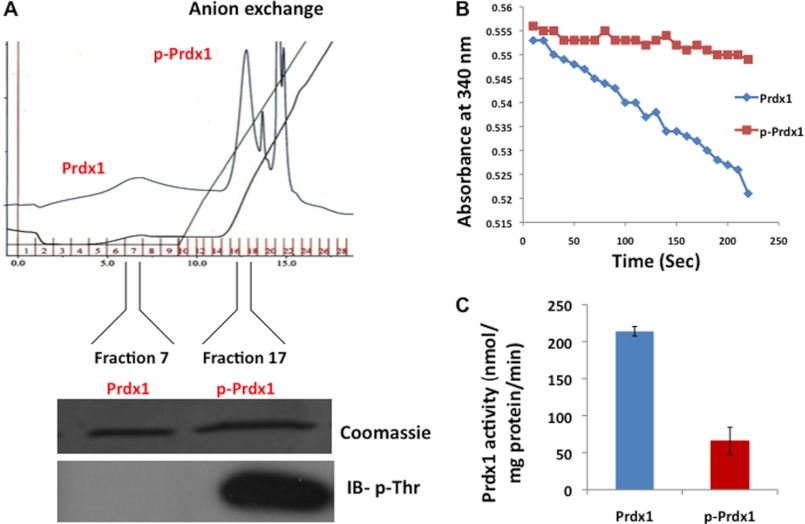

Prdx1 Is Inactivated by Mst1-mediated Phosphorylation

Next, we asked whether phosphorylation by Mst1 affects the peroxidase activity of Prdx1. We determined the conditions for maximal phosphorylation of Prdx1 by phosphorylating Prdx1 with different amounts of Mst1 and for different time periods. For all studies of Prdx1 activity, the GST leader sequence was removed from GST-Prdx1 fusion proteins by protease cleavage. For maximum Prdx1 phosphorylation, we used 40 ng of Mst1/1 μg of Prdx1 and performed the kinase assay for 2 h. Following the kinase reaction, we separated phosphorylated and unphosphorylated Prdx1 using anion exchange chromatography (Fig. 4A). It should be noted that we attempted to produce specific anti-phospho Thr-183 antibodies, but each of these attempts yielded antibodies that recognized phospho-Thr-containing peptides irrespective of the surrounding amino acid sequence. After separating these proteins, the H2O2 peroxidase activity of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated Prdx1 was monitored by measuring decreases in NADPH levels in a coupled assay (35). In this assay, the unphosphorylated form of Prdx1 showed 4-fold greater activity than that of phosphorylated Prdx1, suggesting inactivation of Prdx1 upon phosphorylation by Mst1 (Fig. 4, B and C).

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation of Prdx1 by Mst1 results in its inactivation. A, following kinase assay, the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated proteins were separated by anion exchange as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p-Prdx1, phosphorylated Prdx1; IB, immunoblot; p-Thr, phosphothreonine. B, peroxidase activity of Prdx1 and phosphorylated Prdx1 was monitored by measuring absorbance at 340 nm for 200 s. C, Prdx1 activity was calculated from plot in B, and the results are presented as mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

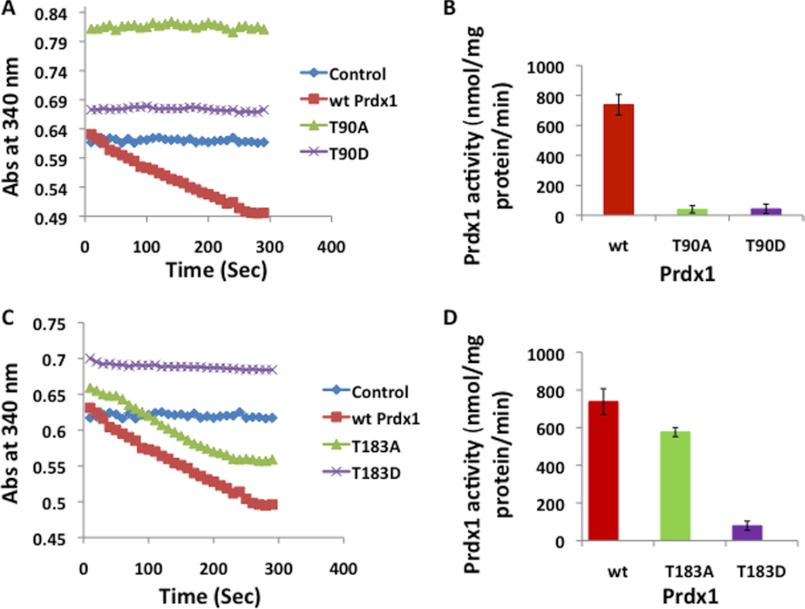

Phosphorylation at Thr-90 and Thr-183 Contributes to Prdx1 Inactivation

To identify the phosphorylation sites that contribute to Prdx1 inactivation, we mutated the three predominant phosphorylation sites (Thr-18, Thr-90, and Thr-183) to aspartic acid to mimic phosphorylation, as well as to alanine, to enforce the unphosphorylated state. We produced these mutants in bacteria (supplemental Fig. S3) and, following purification and removal of GST leader sequences, performed peroxidase assays in the presence of 100 μm H2O2. One of the mutants, Prdx1 T18D, did not express well and could not be used for the peroxidase assay. Prdx1 T90D was inactive in this assay (Fig. 5, A and B), consistent with previous studies demonstrating that phosphorylation of Prdx1 Thr-90 by Cdc2 kinase results in inactivation of Prdx1 (36). Interestingly, the T90A mutant also showed reduced peroxidase activity, similar to the findings of Chang et al. (36), who reported that T90A mutant also has reduced peroxidase activity when compared with WT-Prdx1. The T183D mutant showed very low peroxidase activity when compared with WT-Prdx1, suggesting that phosphorylation at Thr-183 causes inactivation of Prdx1 (Fig. 5, C and D). As expected (and unlike the T90A mutant), the T183A mutant showed nearly normal activity when compared with WT-Prdx1 (Fig. 5, C and D). These results suggest that reversible phosphorylation of Thr-183 by Mst1 contributes to Prdx1 inactivation.

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylation at Thr-90 and Thr-183 inactivates Prdx1. A and C, peroxidase activities of WT-Prdx1, T90A, T90D, T183A, and T183D mutants of Prdx1 were determined by measuring decrease in absorbance (Ab) of NADPH at 340 nm for 300 s. B and D, peroxidase activities of WT-Prdx1, T90A, T90D, T183A, and T183D mutants of Prdx1 were calculated from the graph in A and C. The results are represented as mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

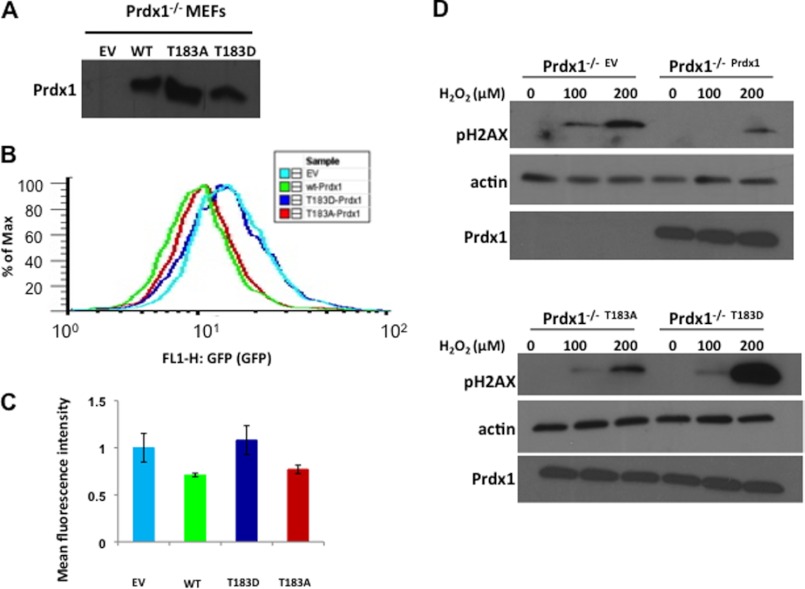

Phosphorylation of Prdx1 at Thr-183 Regulates Hydrogen Peroxide Level in Cells

To understand the physiological relevance of Prdx1 inactivation by Mst1, we tested the effects of Prdx1 phosphosite mutants on the cellular redox state. The most important function of peroxiredoxins is to catalyze the reduction of H2O2 in cells (14, 15). We reasoned, therefore, that phosphorylation and inactivation of Prdx1 by Mst1 would lead to increase in H2O2 level in cells. For these reasons, we measured H2O2 levels in Prdx1−/− MEFs that had been infected with empty vector (EV) or WT, T183A, or T183D versions of Prdx1, respectively. To measure intracellular H2O2, we used carboxy-H2DCFDA, an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye (37). Cells were stimulated with platelet-derived growth factor, which has been shown to induce H2O2 production (38), followed by carboxy-H2DCFDA to image H2O2 levels and allow measurement by flow cytometry (37). As shown in Fig. 6A, WT and mutant forms of Prdx1 were equally expressed in the Prdx1−/− cells. Flow cytometry data showed a marked shift in the histogram corresponding to empty vector and T183D cells, suggesting higher H2O2 levels in these cells when compared with WT and T183A cells (Fig. 6B). Quantification of these results revealed 30% higher DCFDA fluorescence in empty vector and T183D cells when compared with WT and T183A cells (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that phosphorylation at Thr-183 inactivates Prdx1, resulting in increased levels of H2O2 in cells.

FIGURE 6.

Phosphorylation of Prdx1 at Thr-183 increases H2O2 levels and DNA damage in cells. A, Western blot showing expression of WT, T183A, and T183D Prdx1 in Prdx1−/−WT, Prdx1−/−T183A, and Prdx1−/−T183D MEFs, respectively. B, Prdx1−/−EV, Prdx1−/−WT, Prdx1−/−T183A, and Prdx1−/−T183D MEFs were stimulated with 5 ng/ml PDGF for 10 min and were stained with 10 μm carboxy-H2DCFDA for 30 min. DCFDA fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. The curve represents the DCFDA fluorescence for 10,000 events. % of Max, percent of maximum. C, mean fluorescence values ± S.E. of triplicate samples calculated for Prdx1−/−EV, Prdx1−/−WT, Prdx1−/−T183A, and Prdx1−/−T183D MEFs. D, Prdx1−/−EV, Prdx1−/−WT, Prdx1−/−T183A, and Prdx1−/−T183D MEFs were treated with different concentrations of H2O2 for 2 h. DNA damage was measured by performing immunoblot using phospho-H2AX (pH2AX) (Ser-139) antibodies.

If Prdx1 is inactivated by phosphorylation at Thr-183, then cells expressing a Prdx1 T183D mutant should be more susceptible to DNA damage induced by H2O2. To test this idea, we transfected Prdx1−/− MEFs with EV or WT, T183A, or T183D versions of Prdx1 and then treated the cells with different concentrations of H2O2 and measured DNA damage using γH2AX antibodies. As expected, Prdx1−/− cells expressing EV showed higher γH2AX signal at both 100 μm and 200 μm H2O2 when compared with cells expressing WT-Prdx1 (Fig. 6D). Similarly, Prdx1−/− cells expressing the inactive mutant of Prdx1 T183D showed much higher γH2AX signal when compared with cells expressing the T183A mutant (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that increase in H2O2 level upon Prdx1 phosphorylation at Thr-183 leads to increased DNA damage.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we sought to better define Mst1 substrates in cells under oxidant stress. It has been established that Mst1 is activated by a variety of apoptotic and stress stimuli, including oxidative stress induced by the addition of H2O2 (12, 13). We carried out two screens: a yeast two-hybrid screen, with LexA-Mst1 as bait, and a co-immunoprecipitation screen, using doubly tagged Mst1 in basal and stressed mammalian cells as bait. Both screens revealed Prdx1 as a Mst1 interactor. In mammalian cells, we showed that the Mst/Prdx1 interaction is greatly augmented in cells grown under conditions of oxidative stress.

The main known function of Prdx1 is to catalyze the reduction of H2O2 to maintain appropriate cellular redox levels. A number of protein kinases have been shown to regulate Prdx1 activity and hence H2O2 levels. For example, Cdc2 kinase phosphorylates Prdx1 at Thr-90 and inactivates it during mitosis (36). Prdx1 is also inactivated by phosphorylation at Tyr-194 by Src family kinases, resulting in H2O2 accumulation and promotion of growth factor signaling (39). In another study, Prdx1 phosphorylation at Ser-32 by T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase was shown to activate Prdx1, leading to reduced H2O2 accumulation and inhibition of UVB-induced apoptosis (40). In the present study, we demonstrated that Mst1 phosphorylates Prdx1 at several sites and that phosphorylation of Prdx1 at the highly conserved Thr-183 site results in inactivation of Prdx1 with subsequent increased H2O2 levels in cells.

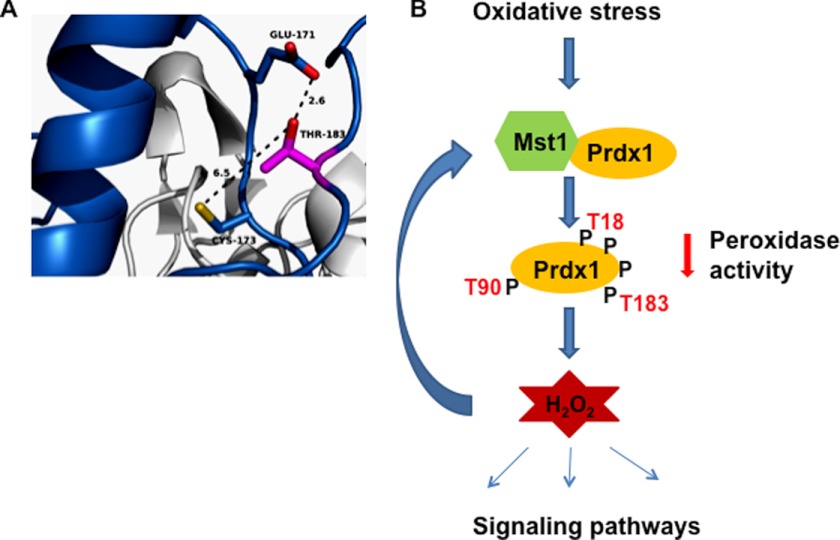

Phosphorylation of Prdx1 at Thr-18 and Thr-183 has previously been identified in unbiased phosphoproteomic analyses of rat inner medullary collecting duct cells and HEK-293T cells, respectively (41, 42), whereas phosphorylation of Thr-90 has been identified by Chang et al. (36). We found that phosphorylation of both Thr-90 and Thr-183 leads to loss of Prdx1 peroxidase activity. Because phosphorylation of Thr-90 has already been reported and the possible mechanism of inactivation has been described (36), we analyzed the crystal structure of Prdx1 to understand how phosphorylation of Thr-183 might affect Prdx1 activity. The three-dimensional structure of Prdx1 revealed that the hydroxyl group on Thr-183 is positioned within 2.6 Å of the carboxyl group of Glu-171, forming a hydrogen bond with Glu-171 (Fig. 7A). Phosphorylation of Thr-183 would be expected to disrupt hydrogen bond formation and might also result in electrostatic repulsion between the negative charges of phosphate group and the carboxyl group of Glu-171. These interactions are likely to cause conformational changes in Prdx1 and inactivate the enzyme (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Proposed model for Mst1 regulation by H2O2. A, crystal structure of Prdx1 showing relative positions of Thr-183 and Glu-171. B, under oxidative stress conditions, Mst1 associates with Prdx1. Mst1 interaction with Prdx1 induces Prdx1 phosphorylation at several sites. Phosphorylation (indicated by P) at Thr-90 and Thr-183 leads to Prdx1 inactivation and hence increase in hydrogen peroxide level in cells. This increase in H2O2 may result in further activation of Mst1 by a feedback loop and induction of apoptosis by Mst1 under oxidative stress conditions.

We also tested Prdx1 association to another Mst family member, Mst2. Mst2 has 78% sequence homology to Mst1 and is similar to Mst1 both in structure and in function. Accordingly, we found that Mst2 binds Prdx1 under oxidative stress conditions and phosphorylates Prdx1 in vitro (data not shown). These observations suggest that Mst2 also regulates Prdx1 in a manner similar to Mst1.

Similar to our findings, Morinaka et al. (18) recently reported that Prdx1 interacts with Mst1 under conditions of oxidative stress. In that study, the authors used RNA interference to demonstrate that Prdx1 is required for Mst1 activation by H2O2. We observed only minor effects on Mst1 kinase activity when Prdx1 was knocked down by siRNA (Fig. 2) or in Prdx1−/− MEFs (data not shown). It is possible that these differences are related to the particular substrates and/or cell lines tested, which may express other members of the Prdx enzyme family with redundant functions to Prdx1 (43, 44). Thus, our data support the view that Prdx1 represents a downstream target, rather than an upstream regulator, of Mst1. In this scenario, Mst1 augments cellular H2O2 levels via inactivation of Prdx1 and perhaps other members of the Prdx family (Figs. 6 and 7B). As Mst1 itself is activated by H2O2, inactivation of Prdx1 might enforce a feedback stimulation system to prolong or intensify Mst1 activation (Fig. 7B). However, the biochemical mechanism by which elevated levels of H2O2 lead to Mst1 activation remains unclear. Some clues may be provided by the protein kinase Ask1, which, like Mst1, is activated by H2O2 and also associates with Prdx1. In this case, H2O2 signals are relayed when oxidized Prdx1 forms a transient mixed disulfide linkage with Ask1, which is resolved by oxidation of Ask1 to a disulfide-linked multimer, representing the active form of the kinase (45). This mechanism seems unlikely to apply to Mst1, however, as knockdown of Prdx1 did not appreciably affect activation of Mst1 by H2O2 (Fig. 2).

Given our findings that Mst1 phosphorylates and inactivates Prdx1, our results suggest that once activated by oxidant stress, Mst1 sustains a pro-oxidant state by reducing the ability of Prdx1 to hydrolyze H2O2 (Fig. 7B). Such a feedback stimulation system, resulting in higher oxidant levels and DNA damage, might represent a tumor suppressor function of Mst1 and Mst2 to prevent the accumulation of mutations in cells (Fig. 7B).

Acknowledgments

We thank Carola Neumann for Prdx1 plasmids and Prdx1−/− MEFs, Matthias Gstaiger for the tap-tagging vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO/SH/GW, and Steven Gygi and the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with analysis of protein complexes and phosphorylation site determinations. The Fox Chase Cancer Center was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (Grant P30 CA006927).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA58836 and R01 CA098830 (to J. C.), as well as by an appropriation from the state of Pennsylvania.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1–S4.

- Prdx1

- peroxiredoxin-1

- carboxy-H2DCFDA

- 6-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DCFDA

- dihydrofluorescein diacetate

- EV

- empty vector

- LATS

- large tumor suppressor

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- Mst

- mammalian sterile twenty

- PHLPP

- PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase

- STRIPAK

- striatin interacting phosphatase and kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Song H., Mak K. K., Topol L., Yun K., Hu J., Garrett L., Chen Y., Park O., Chang J., Simpson R. M., Wang C. Y., Gao B., Jiang J., Yang Y. (2010) Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1431–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou D., Conrad C., Xia F., Park J. S., Payer B., Yin Y., Lauwers G. Y., Thasler W., Lee J. T., Avruch J., Bardeesy N. (2009) Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell 16, 425–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu L., Li Y., Kim S. M., Bossuyt W., Liu P., Qiu Q., Wang Y., Halder G., Finegold M. J., Lee J. S., Johnson R. L. (2010) Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1437–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeng Q., Hong W. (2008) The emerging role of the Hippo pathway in cell contact inhibition, organ size control, and cancer development in mammals. Cancer Cell 13, 188–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Staley B. K., Irvine K. D. (2012) Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Dev. Dyn. 241, 3–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Neill A. K., Niederst M. J., Newton A. C. (2013) Suppression of survival signalling pathways by the phosphatase PHLPP. FEBS J. 280, 572–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qiao M., Wang Y., Xu X., Lu J., Dong Y., Tao W., Stein J., Stein G. S., Iglehart J. D., Shi Q., Pardee A. B. (2010) Mst1 is an interacting protein that mediates PHLPPs' induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell 38, 512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo C., Zhang X., Pfeifer G. P. (2011) The tumor suppressor RASSF1A prevents dephosphorylation of the mammalian STE20-like kinases MST1 and MST2. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6253–6261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oh H. J., Lee K. K., Song S. J., Jin M. S., Song M. S., Lee J. H., Im C. R., Lee J. O., Yonehara S., Lim D. S. (2006) Role of the tumor suppressor RASSF1A in Mst1-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 66, 2562–2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Del Re D. P., Matsuda T., Zhai P., Gao S., Clark G. J., Van Der Weyden L., Sadoshima J. (2010) Proapoptotic Rassf1A/Mst1 signaling in cardiac fibroblasts is protective against pressure overload in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3555–3567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ribeiro P. S., Josué F., Wepf A., Wehr M. C., Rinner O., Kelly G., Tapon N., Gstaiger M. (2010) Combined functional genomic and proteomic approaches identify a PP2A complex as a negative regulator of Hippo signaling. Mol. Cell 39, 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kakeya H., Onose R., Osada H. (1998) Caspase-mediated activation of a 36-kDa myelin basic protein kinase during anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 58, 4888–4894 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lehtinen M. K., Yuan Z., Boag P. R., Yang Y., Villén J., Becker E. B., DiBacco S., de la Iglesia N., Gygi S., Blackwell T. K., Bonni A. (2006) A conserved MST-FOXO signaling pathway mediates oxidative-stress responses and extends life span. Cell 125, 987–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rhee S. G., Chae H. Z., Kim K. (2005) Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 1543–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhee S. G., Kang S. W., Jeong W., Chang T. S., Yang K. S., Woo H. A. (2005) Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goyal M. M., Basak A. (2010) Human catalase: looking for complete identity. Protein Cell 1, 888–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rhee S. G., Yang K. S., Kang S. W., Woo H. A., Chang T. S. (2005) Controlled elimination of intracellular H2O2: regulation of peroxiredoxin, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase via post-translational modification. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 7, 619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morinaka A., Funato Y., Uesugi K., Miki H. (2011) Oligomeric peroxiredoxin-I is an essential intermediate for p53 to activate MST1 kinase and apoptosis. Oncogene 30, 4208–4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. You B., Yan G., Zhang Z., Yan L., Li J., Ge Q., Jin J. P., Sun J. (2009) Phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I by mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1. Biochem. J. 418, 93–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheung W. L., Ajiro K., Samejima K., Kloc M., Cheung P., Mizzen C. A., Beeser A., Etkin L. D., Chernoff J., Earnshaw W. C., Allis C. D. (2003) Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell 113, 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wen W., Zhu F., Zhang J., Keum Y. S., Zykova T., Yao K., Peng C., Zheng D., Cho Y. Y., Ma W. Y., Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2010) MST1 promotes apoptosis through phosphorylation of histone H2AX. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39108–39116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Praskova M., Xia F., Avruch J. (2008) MOBKL1A/MOBKL1B phosphorylation by MST1 and MST2 inhibits cell proliferation. Curr. Biol. 18, 311–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Callus B. A., Verhagen A. M., Vaux D. L. (2006) Association of mammalian sterile twenty kinases, Mst1 and Mst2, with hSalvador via C-terminal coiled-coil domains, leads to its stabilization and phosphorylation. FEBS J. 273, 4264–4276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creasy C. L., Chernoff J. (1995) Cloning and characterization of a human protein kinase with homology to Ste20. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21695–21700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Estojak J., Brent R., Golemis E. A. (1995) Correlation of two-hybrid affinity data with in vitro measurements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5820–5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glatter T., Wepf A., Aebersold R., Gstaiger M. (2009) An integrated workflow for charting the human interaction proteome: insights into the PP2A system. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao J., Schulte J., Knight A., Leslie N. R., Zagozdzon A., Bronson R., Manevich Y., Beeson C., Neumann C. A. (2009) Prdx1 inhibits tumorigenesis via regulating PTEN/AKT activity. EMBO J. 28, 1505–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neumann C. A., Cao J., Manevich Y. (2009) Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling. Cell Cycle 8, 4072–4078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Creasy C. L., Ambrose D. M., Chernoff J. (1996) The Ste20-like protein kinase, Mst1, dimerizes and contains an inhibitory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21049–21053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukai T., Ushio-Fukai M. (2011) Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 1583–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu J. L., Hsieh Y., Tu C., O'Connor D., Nick H. S., Silverman D. N. (1996) Catalytic properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17687–17691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luo X., Li Z., Yan Q., Li X., Tao D., Wang J., Leng Y., Gardner K., Judge S. I., Li Q. Q., Hu J., Gong J. (2009) The human WW45 protein enhances MST1-mediated apoptosis in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 23, 357–362 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song H., Oh S., Oh H. J., Lim D. S. (2010) Role of the tumor suppressor RASSF2 in regulation of MST1 kinase activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 969–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller M. L., Jensen L. J., Diella F., Jørgensen C., Tinti M., Li L., Hsiung M., Parker S. A., Bordeaux J., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Olhovsky M., Pasculescu A., Alexander J., Knapp S., Blom N., Bork P., Li S., Cesareni G., Pawson T., Turk B. E., Yaffe M. B., Brunak S., Linding R. (2008) Linear motif atlas for phosphorylation-dependent signaling. Sci. Signal. 1, ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chae H. Z., Kang S. W., Rhee S. G. (1999) Isoforms of mammalian peroxiredoxin that reduce peroxides in presence of thioredoxin. Methods Enzymol. 300, 219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang T. S., Jeong W., Choi S. Y., Yu S., Kang S. W., Rhee S. G. (2002) Regulation of peroxiredoxin I activity by Cdc2-mediated phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25370–25376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Graves J. A., Metukuri M., Scott D., Rothermund K., Prochownik E. V. (2009) Regulation of reactive oxygen species homeostasis by peroxiredoxins and c-Myc. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6520–6529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kang S. W., Chae H. Z., Seo M. S., Kim K., Baines I. C., Rhee S. G. (1998) Mammalian peroxiredoxin isoforms can reduce hydrogen peroxide generated in response to growth factors and tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6297–6302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woo H. A., Yim S. H., Shin D. H., Kang D., Yu D. Y., Rhee S. G. (2010) Inactivation of peroxiredoxin I by phosphorylation allows localized H2O2 accumulation for cell signaling. Cell 140, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zykova T. A., Zhu F., Vakorina T. I., Zhang J., Higgins L. A., Urusova D. V., Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2010) T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) phosphorylation of Prx1 at Ser-32 prevents UVB-induced apoptosis in RPMI7951 melanoma cells through the regulation of Prx1 peroxidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29138–29146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hoffert J. D., Pisitkun T., Wang G., Shen R. F., Knepper M. A. (2006) Quantitative phosphoproteomics of vasopressin-sensitive renal cells: regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at two sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7159–7164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Molina H., Horn D. M., Tang N., Mathivanan S., Pandey A. (2007) Global proteomic profiling of phosphopeptides using electron transfer dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2199–2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kang S. W., Rhee S. G., Chang T. S., Jeong W., Choi M. H. (2005) 2-Cys peroxiredoxin function in intracellular signal transduction: therapeutic implications. Trends Mol. Med. 11, 571–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood Z. A., Schröder E., Robin Harris J., Poole L. B. (2003) Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jarvis R. M., Hughes S. M., Ledgerwood E. C. (2012) Peroxiredoxin 1 functions as a signal peroxidase to receive, transduce, and transmit peroxide signals in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1522–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]