Abstract

Free energy perturbation (FEP) theory coupled to molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) statistical mechanics offers a theoretically precise method for determining the free energy differences of related biological inhibitors. Traditionally requiring extensive computational resources and expertise, it is only recently that its impact is being felt in drug discovery. A review of computer-aided anti-HIV efforts employing FEP calculations is provided here that describes early and recent successes in the design of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. In addition, our ongoing work developing and optimizing leads for small molecule inhibitors of cyclophilin A (CypA) is highlighted as an update on the current capabilities of the field. CypA has been shown to aid HIV-1 replication by catalyzing the cis/trans isomerization of a conserved Gly-Pro motif in the N-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid (CA) protein. In the absence of a functional CypA, e.g., by the addition of an inhibitor such as cyclosporine A (CsA), HIV-1 has reduced infectivity. Our simulations of acylurea-based and 1-indanylketone-based CypA inhibitors have determined that their nanomolar and micromolar binding affinities, respectively, are tied to their ability to stabilize Arg55 and Asn102. A structurally novel 1-(2,6-dichlorobenzamido) indole core was proposed to maximize these interactions. FEP-guided optimization, experimental synthesis, and biological testing of lead compounds for toxicity and inhibition of wild-type HIV-1 and CA mutants have demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of HIV-1 infection in two cell lines. While the inhibition is modest compared to CsA, the results are encouraging.

Keywords: Free energy perturbation, computer-aided drug design, cyclophilin, HIV, reverse transcriptase, protease, inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

The in silico design of small molecules that bind to a biological target in order to inhibit its function has made great advancements in methodology in recent years for multiple computer-aided drug design (CADD) techniques [1–13]. However, medicinal chemists engaged in CADD often find that accurately predicting the binding affinities of potential drugs is an extremely difficult and time consuming task [14]. For example, virtual screening methods, such as docking ligands into a receptor, allow for a large number of compounds to be vetted quickly, but they often neglect important statistical and chemical contributions in favor of computational efficiency [15]. As a result, large quantitative inaccuracies of the relative and absolute free energies of binding generally occur [16]. While large and continual advances in computational power have helped to advance the field [17], additional improvements in algorithms and methods will be necessary if calculations are to become routine and prospective predictions interpreted with confidence [18, 19]. Free energy perturbation (FEP) simulations rooted in statistical mechanics provide an avenue to incorporate missing effects into the calculations, e.g., conformational sampling, explicit solvent, and shift of protonation states upon binding [20–22], but they generally require extensive computational resources and expertise [23–25]. Despite the challenge, FEP simulations for the identification of drug-like scaffolds and subsequent optimization of binding affinities have been successfully reported, such as the recent development of inhibitors for T4 lysozyme mutants [26, 27], fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase [28, 29], and neutrophil elastate [30]. Given the large body of work that is primarily concerned with using free energy calculations to guide structure-based drug design this review cannot be exhaustive. Instead a more manageable review of computer-aided efforts to design antiretroviral compounds by employing FEP simulations, including our current work developing leads for small molecule inhibitors targeting cyclophilin A (CypA), will be highlighted.

HIV-1

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a disease of pandemic proportions that has killed an estimated 25 million people worldwide and remains one of the leading world-wide causes of infectious disease related deaths [31]. HIV-1 also carries a significant social stigma as many countries lack laws protecting people living with HIV from discrimination [31]. Tragically, it is estimated that 33.3 million people are currently infected with HIV-1 worldwide and approximately 2.6 million people were newly infected in 2009 [32]. The implementation of multiple drug combinations of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996 significantly reduced HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. However, by the late 1990’s HIV-1 strains exhibiting resistance frequencies as high as 24 % to individual drugs in HAART emerged in urban areas and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant viruses was approximately 10 to 13 % in 2006 [33, 34]. While continued efforts to combat HIV-1 have identified multiple druggable targets [35], such as the co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4, Gag protein processing [36], and integrase [37], the majority of the 25 approved antiretroviral drugs (as of 2011) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are directed against two virally encoded enzymes essential to virus replication: protease and reverse transcriptase [32, 38–40].

Combating HIV-1 with CADD

The past several years have been witness to many great successes in developing HIV-1 inhibitors with computer-aided approaches, e.g., virtual screening [41–44], molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) [45–47], molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM-GB/SA) [48–50], and linear interaction energy (LIE) [51–53]. However, in keeping with the theme of this review, i.e., free energy perturbation calculations, not all studies can be highlighted. Fortunately, an excellent review by Liang and co-workers provides an extensive review of important achievements over the past five-years in the discovery of HIV-1 inhibitors utilizing CADD methods [54]. The method of interest here, FEP in conjunction with molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) statistical mechanics, offers a theoretically precise method for determining the free energy differences of related inhibitors. The accurate calculation of free energy changes is vital for the prediction of potentially active compounds in the inhibition of HIV-1. FEP/MD and FEP/MC simulations have played a substantial role in identifying and elucidating the mechanism of potent inhibitors of the HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase enzymes. A brief discussion of the methodology behind FEP and multiple HIV-1 inhibition studies employing the technique is given below.

FREE ENERGY PERTURBATION (FEP) METHODOLOGY

FEP simulations were reported over twenty years ago and early utilization primarily probed chemical and biochemical reactivity, e.g., the solvation of small molecules [55] and computing protein-ligand binding [56, 57]; however, it is only recently that its impact is being felt in drug discovery. The major challenge for implementing FEP as a routine technique in CADD is obtaining reliable ΔG estimates for complex biomolecular systems within a reasonable allocation of computer time and resources. Recent reviews on the topic and historical perspectives are available [9, 22, 25, 58–67]. FEP uses the Zwanzig expression (eq. 1) to relate the free energy difference by constructing a nonphysical path connecting the desired initial (0) and final (1) state of a system [68]. For relative free energies of binding, single or double topology perturbations [25] can be made to convert one ligand to another using the thermodynamic cycle shown in Fig. 1. In the single topology method, force field parameters, e.g., atomic partial charges, Lennard-Jones energy terms, force constants, and geometric changes describing the initial and final states, are linearly interpolated between 0 and 1. The double topology approach does not use interpolation of the force field parameters, but instead it interpolates the potential energy. In addition, both molecules, i.e., initial and final state, are present throughout the simulation while occupying the same volume. Both topology methods should in principle provide equally accurate results; however, for FEP methods it has been reported that the single topology approach is more efficient than the dual topology for all but very long simulations [69]. The < > brackets in eq. 1 indicate that the bracketed quantity is averaged over all the configurations X can adopt from ΔG(X→Y) and are weighted by their Boltzmann probabilities. Configurations of X are generated using a molecular simulation, e.g., molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo statistical mechanics, with the appropriate Boltzmann weights. A simple average of the exponential term is then performed over these configurations.

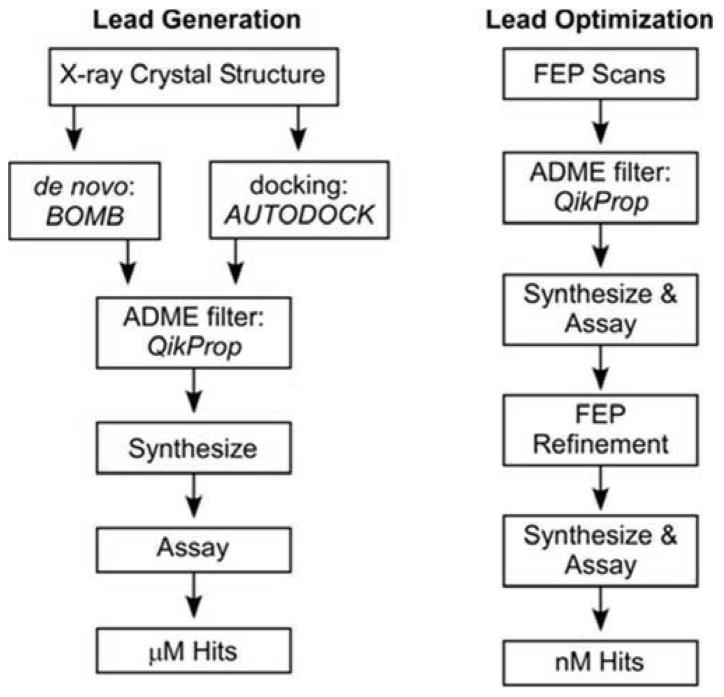

Fig. 1.

Thermodynamic cycle for relative free energies of binding. HIV is the receptor, and X and Y are different ligands.

| (1) |

The mutation of ligands or proteins can use double-wide or overlap sampling [58] in multiple FEP windows, usually 5 to 15. A window refers to an MC or MD simulation at one point along the mutation coordinate λ, which interconverts two ligands as λ goes from 0 to 1. Double-wide implies that two free energy changes are computed at each window, corresponding to a forward, λk+1, and backwards, λk−1, increment evaluated with a simulation conducted at the reference state, λk. The overlap sampling method is similar to double-ended sampling, which refers to performing both a λi → λj perturbation and its reverse, λj → λi, but to an intermediate point rather than the end points 0 and 1 [58]. In a recent FEP mutation of azole-based ligands bound to HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, a comparison between the efficiency and accuracy of the overlap and double-wide sampling choices was carried out by Jorgensen and coworkers [70]. The differences in the free energies of binding yielded an overall time for the FEP calculations that were cut roughly in half for the overlap sampling method (using 11 windows) compared to double-wide sampling (using 14 windows); however, some discrepancies in the computed ΔΔGbinding values between the overlap and double-wide sampling methods were reported. The spacing used between the windows, Δλ, was primarily 0.1 with the exception of λ = 0 – 0.2 and 0.8 – 1 where the spacing is 0.05, which addresses the fact that the free energy often changes most rapidly in these regions [70].

The total free energy change is computed by summing the incremental free energy changes in each window. The difference in free energies of binding for the ligands X and Y then comes from ΔΔGbind = ΔGX − ΔGY = ΔGF − ΔGC (Fig. 1). Two series of mutations are performed to convert X to Y unbound in water and complexed to the protein which yields ΔGF and ΔGC. A successful FEP protocol in drug discovery is to replace each hydrogen of a promising scaffold with 10 small groups that have been selected for difference in size, electronic character, and hydrogen-bonding patterns: Cl, CH3, OCH3, OH, CH2NH2, CH2OH, CHO, CN, NH2, and NHCH3 [9]. It should be noted that there are normal experimental issues that affect the accuracy of binding studies. In general, if a group of inhibitors have the same mechanism of action, the ratios of IC50 values should be the same as the ratios of Kis as long as the assays yielding the IC50 values are performed in the same way. The latter condition generally requires only using IC50 values from a single source for a given set of inhibitors [1].

DEVELOPMENT OF HIV-1 INHIBITORS GUIDED BY FEP CALCULATIONS

HIV-1 PR

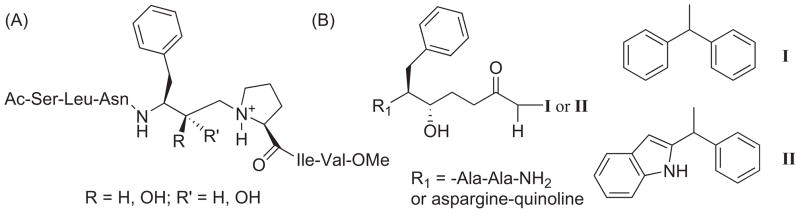

HIV-1 protease (PR) is responsible for the cleavage of the Gag and Gag-Pol precursor polyproteins into the structural and enzymatic proteins, leading to maturation and infectivity of virions [71]. HIV-1 PR inhibitors interfere in the late stage of viral replication to prevent the formation of infectious virus particles. FEP guided studies on HIV-1 PR inhibition began in the early 1990s [72], made possible by the determination of HIV-1 protein-inhibitor crystal structures [73, 74], and primarily focused on rationalizing the known binding affinities between closely related polypeptide-based inhibitors. For example, in 1991 Reddy et al. [75] used an FEP/MD approach to mutate the inhibitor ligand by deleting the hydrophobic residue valine of the JG-365 heptapeptide inhibitor Ac-Ser-Leu-Asn-(Phe-Hea-Pro)-Ile-Val-OMe made by Rich et al. [76] (Fig. 2A) to create the hexapeptide Ac-Ser-Leu-Asn-(Phe-Hea-Pro)-Ile-OMe (where Hea is hydroxyethylamine). The ‘alchemic’ mutation yielded a calculated difference in the binding free energy, ΔΔGbind, of 3.3 ± 1.1 kcal/mol (averaged for R and S) which was in good agreement with the experimental value of 3.8 ± 1.3 kcal/mol, obtained from Ki values for an equilibrium mixture of R and S configurations. Their computational work elucidated the observed differences between inhibition strengths of the ligands and demonstrated the viability of the FEP/MD methodology for future screening of lead inhibitors prior to synthesis.

Fig. 2.

(A) HIV-1 protease (R)-OH and (S)-OH heptapeptide inhibitor JG-365 [79] and (B) the mutation of compounds I → II by Reddy et al [80].

Also in 1991, Kollman and co-workers [77] sought to deduce the difference in binding affinities between the two diastereomeric forms of the JG-365 PR inhibitor (Fig. 2A), where the configurational S- and R-hydroxyl groups play major roles in binding. Mutation of the (S)-OH to (R)-OH group and the deletion of OH via FEP/MD simulations quantified hydrogen bonding interactions with the carboxylates of the catalytically important Asp diad at the active site. For example, relative free energy differences, ΔΔGbind, for the (S) to (R) inhibitor bound to HIV-1 PR with dianionic Asp25 and Asp125 residues, a protonated Asp25, and a protonated Asp125 were computed as 4.0 ± 0.4, 6.8 ± 0.2, and 2.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to the experimental value of 2.6 kcal/mol While the calculated energies were in good agreement with experimental data and the simulations elucidated the preferred protonation state, caveats were issued on the overall limitations of the method, e.g., potentially insufficient sampling of the microstates due to the short time lengths of the simulation (20 ps), unknown adequacy of the force field parameters, and geometric constraints on the X-ray structure during simulation. Subsequently in 1992 Tropsha and Hermans [78] utilized a slow-change FEP method to estimate the binding constants of the (S) and (R) isomers for the same inhibitor (Fig. 2A). They confirmed a strong preference for the (S) configuration by a computed value of 2.9 kcal/mol and also predicted a favorable protonated state for the Asp125 residue.

An FEP/MD study by Singh and co-workers [81] determined the relative binding free energies of two classes of HIV-1 PR polypeptide inhibitors: hydroxyethylene isostere (HEI), Ala-Ala-Phe[CH(OH)CH2]Gly-Val-Val-OMe, [82] and a reduced peptide inhibitor MVT-101, Ac-Thr-Ile-Nle-ψ [CH2-NH]-Nle-Gln-Arg-NH2 [73]. The mutation of the central hydroxyl group in HEI was changed from S to R and the computed ΔΔGbind of 3.37 ± 0.64 kcal/mol between the two diastereomers was in reasonable agreement with the experimental value of 2.6 kcal/mol. Mutation of Gly to Nle (norleucine) in HEI predicted an enhancement of the binding by 1.7 kcal/mol, while mutating a single Nle to Met in MVT-101, via the change of a methylene group to a sulfur, decreased the binding by 0.7 kcal/mol. The results suggested that Nle may useful for improving inhibition and were consistent with other inhibitors series where hydrophobic side chains contributed ca. 1 – 2 kcal/mol towards binding.

Reddy et al. [80] provided one of the first demonstrations of the viability of the FEP/MD approach to present an iterative structure-based design program for the accurate prediction of relative binding affinities that guided synthesis of inhibitor analogs for HIV-1 PR. The thermodynamic cycle perturbation given in Figure 1 was used to compute the relative change in the binding free energy difference, ΔΔGbind = ΔGC − ΔGF, from compound I to II (Fig. 2B). X–ray crystal structures with both compounds bound in the active site were solved and used as initial coordinates to compute the mutations of I → II and II → I where the phenyl ring was transformed into an indole ring and vice versa. The computed ΔΔGbind of −2.3 ± 0.6 and 1.9 ± 0.6 kcal/mol for the mutations of I → II and II → I, respectively, were in reasonable agreement with the experimental values of −1.3 ± 0.30 and 1.3 ± 0.30 kcal/mol. Further heterocyclic mutations of the phenyl and indole rings of I and II were performed with good success, i.e., error margin of 1 kcal/mol, to guide subsequent experimental synthesis, crystallography, and biological testing of potential HIV-1 PR inhibitors.

A structure-assisted drug design effort by Murcko and coworkers including FEP calculations contributed towards the discovery of the FDA-approved PR inhibitor amprenavir (formerly VX-478) [83–85]. Additional successful applications of the FEP method for the calculation of HIV-1 PR inhibition, including non-peptide inhibitors, have been reported by McCarrick and Kollman [86], Rao and Murcko [87], Varney et al. [88], Chen and Tropsha [89], and Wang et al. [90] and has laid the path for more recent accomplishments in FEP guided design of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

HIV-1 RT

HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) is a multifunctional enzyme that performs viral reverse transcription, which is the production of double stranded DNA from the single stranded viral RNA genome. Efforts for the inhibition of HIV-1 RT have resulted in the identification and development of three different classes of inhibitors: nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NtRTI) and the nucleoside and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI and NNRTI, respectively). NNRTIs work by binding to an allosteric pocket near the active site of the HIV reverse transcriptase’s polymerase, thereby inhibiting the enzyme’s activity [91], while NtRTIs and NRTIs are incorporated into the nascent DNA, causing premature termination [92]. Common single mutations of RT, e.g., L110I, K101E, K103N, V106A, Y181C, Y188C/L/H, G190A/S, P225H, and F227C/L, confer resistance to many NNRTIs. The effects of HIV-1 RT mutations on the activities of NNRTIs have been computationally studied via the transformation of active site residues using FEP/MC methodology [93–96]. For example, Udier-Blagović et al. [95] computed ΔΔG’s of −2.4 and −2.4 kcal/mol for FEP mutations of K103N and Y188L with a bound etravirine molecule relative to efavirenz that were in good agreement with experimental values of −2.00 ± 0.40 and −2.07 ± 0.23 kcal/mol, respectively; and they predicted ΔΔG’s of −0.9 and −2.6 kcal/mol for L100I and Y181C with a bound etravirine molecule relative to nevirapine that were also reasonably accurate compared to experimental values of −2.36 ± 0.42 and −1.36 ± 0.28 kcal/mol, respectively. The FEP based RT mutant studies [93–96] have emphasized that while the more rigid fused polycyclic cores of FDA-approved NNRTIs provide good potency against the wild-type (WT) HIV-1 RT, new compounds that include conformational flexibility and possess a small size are desirable for combating drug-resistant mutants [97].

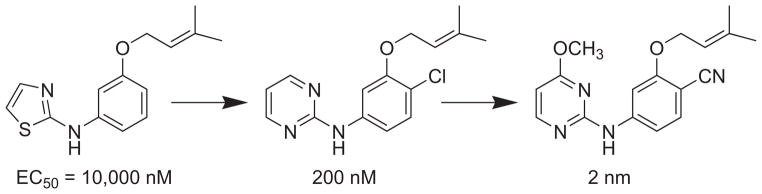

In addition to studying the binding affinities of known NNRTIs, Jorgensen and co-workers have utilized FEP/MC simulations to guide lead generation and optimization of novel micromolar anti-HIV molecules targeting RT since 2006 [98–100]. Initial NNRTI design began with two motifs, U-Het-NH-Ph and Het-NH-Ph-U, where U is an unsaturated, hydrophobic group and Het is an aromatic heterocycle. The program BOMB was used to construct thousands of NNRTI leads by adding user-selected substituents to the motifs in the same spirit as synthetic modifications. Hundreds of potential leads were narrowed down by using FEP/MC calculations to convert multiple heterocycles in the scaffolds including phenyl, pyrimidinyl, pyrazinyl, pyrrolyl, furanyl, oxazolyl, thiazolyl, trizaolyl and others. Compounds were screened in parallel prior to committing to synthesis and strong correlation with experiment highlighted the usefulness of the technique. As an example, an initial thiazole compound given in Fig. 3 yielded an EC50 of 10,000 nM for protection of human MT-2 cells from cytopathogenicity and was subsequently guided via FEP simulations to a 2 nM pyrimidine-based inhibitor [98–100].

Fig. 3.

FEP/MC guided optimization of a thiazole scaffold towards a low nM HIV-1 RT pyrimidine-based inhibitor [98–100].

Virtual screening was also used as an alternative to de novo design to generate leads prior to FEP optimization. Barreiro et al. [48, 101] docked a library of 70,000 commercially available compounds from the Maybridge catalog and 26 known NRRTIs into the HIV-1 RT binding site in order to identify potential leads. The docking program Glide 3.5, using its standard and extra-precision modes [102, 103], narrowed down the search to the top 100 compounds which were postscored using an MM-GB/SA method. The NNRTIs were successfully retrieved, however, assaying the top 20 scoring compounds from the library failed to produce any active anti-HIV compounds. The highest-ranking library compound, an inactive oxadiazole, was further pursued to seek constructive modifications using FEP/MC guided optimization. Chlorine scans, where hydrogens (particularly aryl hydrogens) on the scaffold are systematically mutated to chlorine, were performed in the solvated RT to seek auspicious sites for substitution. The most favorable ΔΔGbind sites were further mutated into 9 small groups, CH3, OCH3, OH, CH2NH2, CH2OH, CHO, CN, NH2, and NHCH3, and yielded a polychloro-analog (Fig. 4) with an EC50 value of 310 nM in an infected MT-2 human T-cell assay. As a point of reference nevirapine gave an EC50 value of 110 nM. Zeevaart et al. [70] further optimized the oxadiazole scaffold with an exhaustive FEP/MC scan to seek additional promising sites for substitution. The study guided the inactive scaffold towards a novel and highly potent NNRTI oxazole derivative with an EC50 of 13 nM (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

FEP/MC guided optimization of an inactive oxadiazole scaffold towards a low nM HIV-1 RT inhibitor [48, 70, 101].

The diverse set of HIV-1 RT inhibitor candidates developed by Jorgensen and co-workers, e.g., pyrimidinyl [100], triazinyl-amines [100], bicyclic heterocycles [104], and azole [70, 105] based compounds, has proven the FEP/MC method to be effective and consistent in rapidly progressing lead compounds towards low nanomolar, novel NNRTIs with good pharmacological properties. Approximate procedures such as linear response and MM-GB/SA were deemed not accurate enough to direct lead optimization. A review by Jorgensen is available on their most recent progress developing NNRTIs via a combined effort of FEP/MC simulations, experimental synthesis, and biological testing [9].

OUR ONGOING RESEARCH DEVELOPING HIV INHIBITORS TARGETING CYCLOPHILINS

The focus of this review will now shift to a discussion of our most recent studies and ongoing work utilizing FEP/MC to construct small molecule leads, based on mimics of cis proline, that display activity against cyclophilins in order to study their efficacy in preventing HIV-1 infection in various cell types.

Cyclophilins

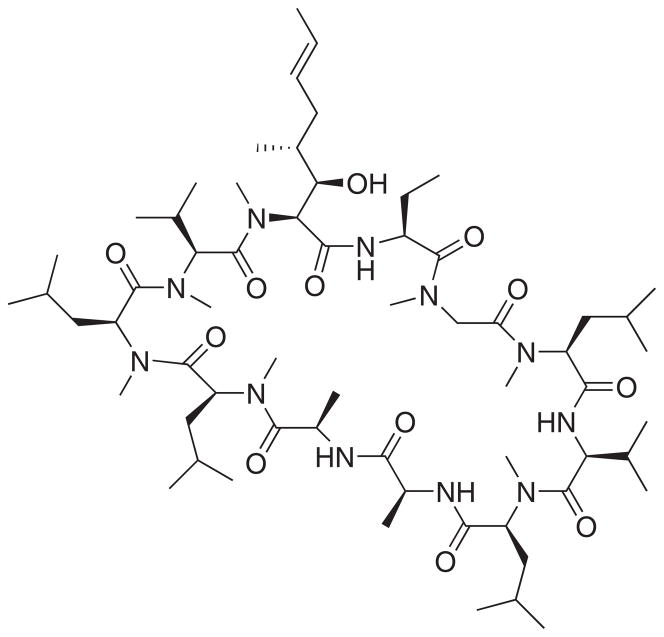

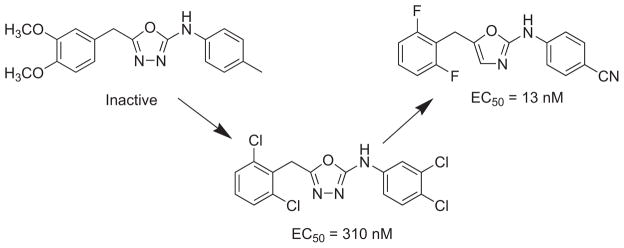

Cyclophilins (Cyps) belong to the family of cis-trans peptidyl prolyl isomerase (PPIase) enzymes whose main role is to catalyze the conversion of nascent protein strands containing cis-proline residues to the more stable trans-proline conformation (Fig. 5). This isomerization has been identified as the rate-limiting step in protein folding [106, 107]. Review of the biochemistry of the PPIases is well-represented in the literature with an emphasis on overall biological relevance [108, 109], foundational biochemistry [110, 111], mechanism [112], inhibitors [113–116], and possible therapeutic utility [117]. Eight human Cyps with molecular masses ranging from 18 to 150 kDa [107] and an additional 12 multidomain Cyps (masses up to 352 kDa) have been reported that contain a highly conserved active site, making specific inhibition of a particular family member difficult [118]. Older nomenclature employs a numeric suffix derived from the enzyme weight in kDa. As a result, a discrete cyclophilin may have multiple names: for example, cyclophilin A (CypA) is identical to cyclophilin 18. All Cyps contain a cis-trans PPIase domain with an 8-strand β-bundle and two associated α-helices, which binds a portion of the macrocyclic immunosuppressive drugs represented by cyclosporine A (CsA) (Fig. 6) [119–122]. This dimeric complex then binds a third partner, such as calcineurin. The identity of this third binding partner and the ensuing formation of an active or inactive ternary complex is dependent on the identity of bound ligand; this has been referred to as ligand specific protein binding and activation [123]. The ternary complex of CypA/CsA/calcineurin generates active pSer (pThr) 2B protein phosphatase which, in part, mediates the immunosuppressive properties of CsA.

Fig. 5.

Interconversion of cis-proline residues to the more stable trans-proline conformation.

Fig. 6.

Cyclosporine A (CsA).

Role of Cyps in HIV-1 Infection

Retroviruses are enveloped and package two copies of a singlestranded RNA genome into a viral core made up of capsid (CA) proteins. The capsid-associated core dissociates soon after penetration of the HIV-1 virus into the cell, allowing reverse transcription to be completed. While HIV-1 CA uncoating is not yet well understood, the process appears to be tightly regulated, most likely as a result of interactions with host cell proteins [124]. Mutations in CA that cause uncoating to occur more quickly or more slowly than wild-type (WT) virus have detrimental effects on reverse transcription, the formation of pre-integration complexes, and the nuclear import of viral DNA [125–127]. Cyclophilin A (CypA) has been demonstrated to bind to multiple HIV-1 proteins, particularly CA, and catalyzes the cis/trans isomerization of a conserved Gly-Pro motif within the cyclophilin-binding loop between helices 4 and 5 in the N-terminal [128–135]. Numerous studies have critically linked HIV-1 viral infectivity to the formation of these CA-CypA complexes [136–138]. In addition, HIV-1 CA has been shown to bind to cyclophilin B (CypB) [128]. Interestingly, CypB binds to G89A and P90A of HIV-1 Gag as well as simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Gag [139]. Its leader sequence that directs CypB to the endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for this difference in binding [139, 140]. While virions package CypA from the producer cell [128, 137], studies show that the interaction of CA with CypA in the target cell is important for infection [141–143]. CD147 (a type I transmembrane protein) has also been shown also to stimulate, in a CypA-dependent manner, an early step of HIV-1 replication [144, 145].

CypA binds to Gag in infected cells at a loop consisting of residues 85–93 in HIV-1 CA and approximately 10% of the molecules recruit the host protein into the virion [132, 146]. Upon binding to CA, CypA catalyzes the formation of the cis isoform of the bond between G89 and P90, which may result in destabilization of the core [132, 146]. It is thought that this process might protect HIV-1 from a host cell restriction factor that recognizes the trans conformation of CA [141, 147]. The interaction of HIV-1 CA and CypA can be disrupted by CsA (Fig. 6), a competitive inhibitor that binds to CypA at the same site that CA does [148, 149]. In the absence of functional CypA by the addition of CsA or by RNA interference in multiple human cell types, HIV-1 has reduced infectivity, which is cell type dependent [141–143, 150–152]. Three isoforms of CypA assemble within HIV-1 virions and one of these is located on the outer surface of HIV and may target heparans on the surface of the host cell facilitating attachment [153, 154]. The remaining two isoforms are associated within the viral membrane and may facilitate virion packaging; this would be consistent with the observed decrease in viral load from CsA. A deficiency of CypA also leads to the majority of the covalent bonds between these residues to be in the trans conformation [132].

Other laboratories have characterized different CA mutants in the CypA binding loop for the ability to infect cells in the presence or absence of CypA in many cell lines [141, 142, 150]. It has been shown that in HeLa cells, WT virus was modestly inhibited by CsA, whereas two mutants, A92E HIV-1 and G94D HIV-1, are dependent on CsA treatment for efficient infectivity in HeLa cells [141, 142, 150]. Two other mutants, G89V HIV-1 and P90A/A92E HIV-1 [142, 143], are CypA independent and will infect HeLa cells similarly in the presence or absence of CsA. These results have been observed in HeLa cells as well as CD4+ T cell lines. N74D HIV-1, a mutant that we recently selected for resistance to a restriction factor [155], appears to be hypersensitive to CsA treatment in HeLa cells (Z. Ambrose et al., submitted).

In contrast, WT, N74D, A92E, and G94D HIV-1 were all sensitive to CypA disruption by CsA in human primary monocytederived macrophages (Z. Ambrose et al., submitted). G89V and P90A/A92E HIV-1 were slightly affected by CsA in macrophages. These results suggest that N74D HIV-1 is hyperdependent on CypA for infection of both HeLa cells and macrophages. Additionally, it appears that CypA interactions with WT or N74D CA in macrophages are more critical for HIV-1 infection than in HeLa cells. This phenotype is recapitulated in GHOST cells, which are human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells expressing T cell receptors and coreceptors and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene under the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter [156]. Together, these results suggest that HeLa cells have a similar phenotype to the Jurkat CD4+ T cell line and GHOST cells have a similar phenotype to primary human macrophages.

Nonimmunosuppressant derivatives of CsA have also been found to be effective at cyclophilin inhibition and diminishing the HIV-1 viral load [129]. For example, DEBIO-25, a derivative of CsA that differs by a single amino acid side chain (Fig. 7), is predominately a CypB [140] inhibitor that has been demonstrated to reduce HIV-1 infection and replication in vitro and found to reduce infection and replication of HIV-2 without activating calcineurin when used in combination with existing antiretroviral therapeutic agents [157–159]. SCY-635 deviates from the structure of CsA by variation on the 3 and 4 amino acid residues (Fig. 7) and exhibits equipotent binding to CA as compared to CsA; this portion of the macrocycle is directed away from the prolyl isomerase active site toward calcineurin and like DEBIO-025 does not activate calpain [160]. In addition, CsA and analogs were found to not interact directly with HIV-1 proteins [129]. Three significant points should be emphasized: 1) immunosuppressive and anti-viral effects of CsA are possibly independent [161, 162], 2) inhibition of cyclophilin is a potentially useful strategy for reducing HIV-1 infectivity and replication in vivo, and 3) this antiviral effect may be synergistic with currently used therapies. Thus, by identifying novel CypA or CypB specific inhibitors, their capability for virus inhibition in different cell lines can be assessed and, in addition, any potential additive or synergistic effects with CsA and nonimmunosuppressive derivatives of CsA can also be gauged.

Fig. 7.

DEBIO-025 (left) and SCY-635 (right) derivatives of CsA.

HIV-1 Infectivity in Macrophages

Although HIV-1 can be effectively suppressed with highly active antiretroviral therapy [32, 163], it is not eradicated from the body. In addition, the emergence of HIV strains resistant to HAART has posed serious concerns for the viability of future treatments [164]. Most individuals discontinuing suppressive therapy have a rapid rebound in plasma viremia [165–169]. One explanation for this observation is the persistence of the virus in biological reservoirs. These reservoirs are maintained by infected cells harboring proviral DNA that may become transcriptionally active. Future antiretroviral therapies will need to be effective at targeting these long-lived cells.

Macrophages have been suggested as a possible reservoir for harboring latent virus in the host [170, 171]. Macrophages are antigen-presenting cells that are critical to the innate immune response against pathogens. As such, these cells both directly kill foreign pathogens and secrete cytokines in response to infection to activate other cells of the host immune system. These cells are primarily located in tissues where HIV-1 exposure and replication can occur (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract, female genital tract, lymphoid tissues, and brain) [172–177]. While HIV-1 is widely known to infect human CD4+ T cells, it can also efficiently infect macrophages in vitro and in vivo. In addition, HIV-1 infection of macrophages is different than infection of CD4+ T cells from viral entry to assembly and release [178]. Macrophages have unique features that can alter the replication lifecycle of the virus as compared to T cells. For example, macrophages are nondividing cells, which require the viral DNA (vDNA) to be actively transported into the nucleus through nuclear pore complexes for integration and completion of infection. This ability of HIV-1 to infect nondividing cells is the definition of a lentivirus and is not shared by other types of retroviruses [179]. In addition, assembly and release of HIV-1 particles appears to be different in macrophages as compared to T cells, with targeting of the viral proteins occurring in multivesicular bodies in macrophages instead of the plasma membrane as is the case in T cells [180, 181]. Therefore, HIV-1 infection of and replication in macrophages appears quite different than in T cells and may result in significant pathogenesis to the host [182]. In light of the sensitivity of HIV-1 to CypA disruption by CsA in human primary macrophages for WT and various mutants (Z. Ambrose et al., submitted), construction of novel small molecule inhibitors that display activity and selectivity towards the host CypA proteins (and potentially CypB) could be an effective strategy to combat HIV-1 infection of macrophages.

Small Molecule Inhibitors of Cyp A/B

Although small molecule inhibitors of PPIase enzymes have been identified for 15 years, the development of small-molecule inhibitors that possess nanomolar potency and high specificity for a particular Cyp is difficult given the complete conservation of all active site residues between the enzymes. It has only been shown recently that small molecules can differentiate between isoforms of cyclophilins, particularly CypA and CypB. These results have emanated primarily from the laboratories of Fisher [113, 183, 184] and Li [185–187]. Recent structural analysis of known human cyclophilins utilizing both X-ray crystal structures and homology modeling assuming an invariant Arg (Arg55 and Arg63 for CypA and CypB, respectively) have identified two specific locations near the catalytic site likely to confer isoform selectivity: the S2 pocket and the S1′ pocket. Unique residues on the S2 pocket exist for each isoform suggesting the potential for rationally developing selective inhibitors. Analysis of p-nitrophenyl tagged tetra-peptide-based ligands with isothermal calorimetry and 1H/1H TOSCY experiments were consistent with the hypothesis of isoform variation in the S2 pocket contributing to ligand selectivity for a given Cyp [188].

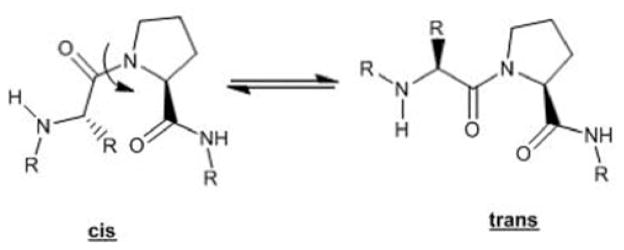

Variations of compound 1 (see Fig. 8) have been reported to have near equipotent activity in cyclophilin A inhibition compared to CsA [187]. Our recent computational study utilizing FEP/MC simulations [189] elucidated the origin of the experimentally observed nanomolar inhibition of CypA by acylurea-based compounds, 1a–1j, featuring variations of R1 and R2 λ where the 2-Cl,6-F-phenyl ring derivative (1a) was the best reported inhibitor with an IC50 of 2.6 nM for CypA inhibition. As a point of comparison CsA exhibits a 2.9 nM inhibition of CypA [113]. Table 1 provides the computed ΔΔGbind values with the correct binding affinity trend predicted when compared to the IC50 enzyme inhibition assay results. Uncertainties in the ΔΔGbind were calculated by propagating the standard deviation (σi) on the individual ΔGi values for each Δλ window. In carrying out the FEP mutations, the greatest accuracy was found by mutating larger substituents to smaller ones, e.g., Cl to F, and by carrying out a single mutation at a time. For example, the transformation of 1d → 1f was carried out by two sequential mutations of (1) R2 = F to H from 1f to yield 1e and from (2) R1 = Cl to F from 1d to 1e. Combining the results into the overall mutation of 1d → 1e ← 1f yielded a ΔΔGbind of −0.68 ± 0.09 kcal/mol compared to the experimental value of −0.56 kcal/mol (Table 1). However, the direct transformation of 1d → 1f via simultaneous mutations (i.e., R1 = Cl to F and R2 = H to F) gave a ΔΔGbind of −1.79 kcal/mol.

Fig. 8.

Chemical structures of acylurea-based (1) and aryl 1-indanylketone-based (2 and 3) Cyp inhibitors.

Table 1.

MC/FEP Results for the Mutation of Acylurea-based Inhibitors (1)a

| Compd | R1 | R2 | ΔΔGbind (calc) | ΔΔGbind (exptl)b | IC50, (nM)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Cl | F | −1.48 ± 0.07 | −3.05 | 1.52 ± 0.10 |

| 1a | F | Cl | 8.38 ± 0.26 | ||

| 1b | Cl | Cl | −1.37 ± 0.10 | −2.74 | 2.59 ± 0.20 |

| 1c | CN | H | −0.21 ± 0.16 | −0.78 | 71.2 ± 0.30 |

| 1c | H | CN | −1.67 ± 0.19 | ||

| 1d | Cl | H | −0.68 ± 0.09 | −0.56 | 103 ± 5 |

| 1d | H | Cl | 1.44 ± 0.10 | ||

| 1e | F | H | −0.13 ± 0.07 | −0.30 | 159 ± 7 |

| 1e | H | F | 0.51 ± 0.07 | ||

| 1f | F | F | 0 | 0 | 263 ± 24 |

| 1g | NO2 | H | 0.54 ± 0.30 | 0.51 | 620 ± 32 |

| 1g | H | NO2 | 2.62 ± 0.36 | ||

| 1h | OH | H | 1.67 ± 0.13 | > 2.15 | > 10,000 |

| 1h | H | OH | 1.56 ± 0.14 | ||

| 1i | NH2 | H | 0.05 ± 0.20 | > 2.15 | > 10,000 |

| 1i | H | NH2 | 0.07 ± 0.22 | ||

| 1j | H | H | 0.27 ± 0.09 | inactive | inactive |

Positive ΔΔGbind value (kcal/mol) means R1=R2=F (1f) was preferred and negative means new mutation is preferred.

Calculated from ΔΔGbind = RT ln [IC50(1x)/IC50(1f)] at 298 K.

Experimental IC50 values from ref. [187].

Our simulations determined that the binding affinity is tied to the ability of the inhibitor to stabilize Arg55 and Asn102 in CypA and the analogous Arg63 and Asn110 residues in CypB [189]. A breakdown of the total Coulombic and van der Waals interaction energies between 1a and the residues finds large values of −11.7 and −10.9 kcal/mol for Arg55 and Asn102, which is consistent with Hamelberg and McCammon’s findings that those two residues are essential in stabilizing the transition state conformation of the cistrans isomerization of the - Gly-Pro-ω angle in Ace-His-Ala-Gly-Pro-Ile-Ala-Nme [190]. The tandem amide forms multiple tight hydrogen bond interactions with the Arg and Asn residues located in the “saddle” region of the active site while the planar fluorene rings and 2,6-disubstituted phenyl moiety insert favorably into two adjacent hydrophobic sub-binding pockets. The binding mode of compound 1 as predicted by BOMB is consistent with previous motifs generated from AUTODOCK 3 and LigBuilder 2.0, where an rmsd of ca. 1.5 Å was found between the methods [187].

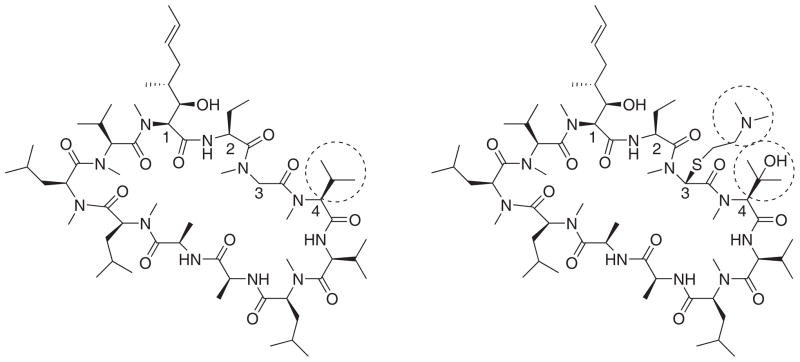

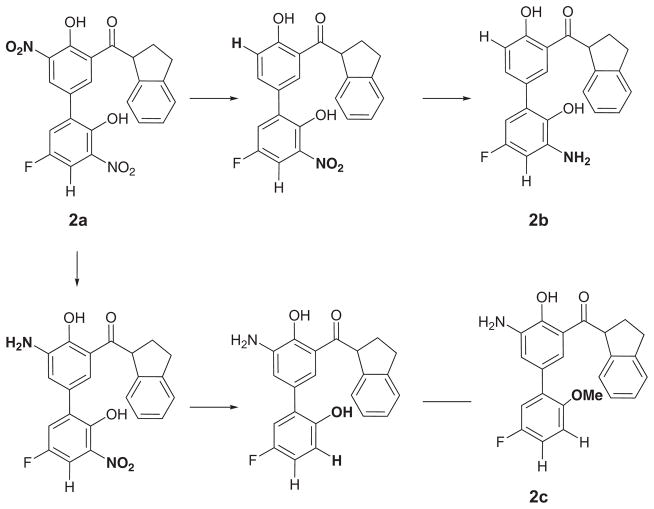

Selectivity Towards CypA

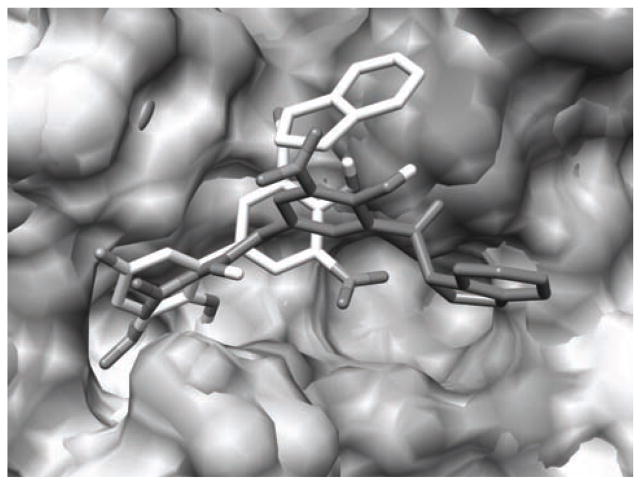

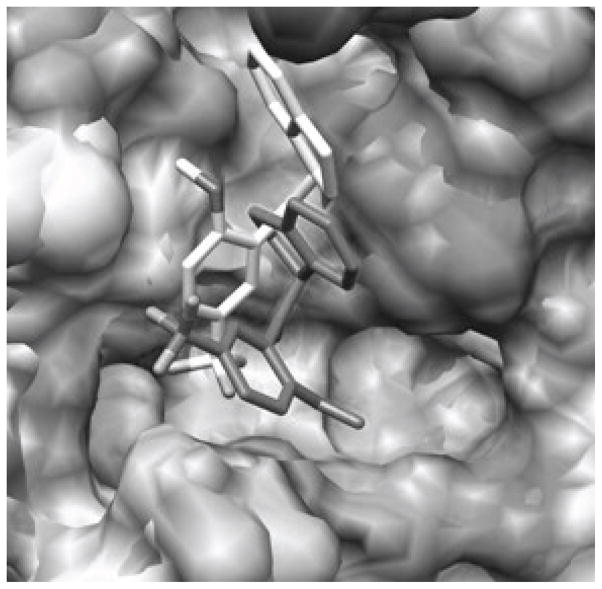

Compound 2a (R1 = NO2, R2 = OH, and R3 = NO2) is particularly interesting because its Ki value, as determined by a fluorescence quench assay, is reported to be 0.52 ± 0.15 μM in CypA and >100 μM in CypB implying a >200-fold selectivity between the cyclophilins from in vitro and in vivo experiments despite a completely conversed active site [113]. Compounds 2a, 2b (R1 = H, R2 = OH, and R3 = NH2), and 2c (R1 = NH2, R2 = OMe, and R3 = H) represent a parvalin series scaffold modified for selective CypA inhibition (Fig. 9). The requisite 2-hydroxyl and the dihydroindane ring have been proposed to mimic the prolyl acyl and the 3′-nitro biphenyl system adds potency. Accordingly, the 2a compound shows no inhibition at the B or C isoforms and is 4 times less active against isoform D. The reasons behind the selectivity have been difficult to rationalize from an experimental perspective. However, NMR studies have suggested that the active site of CypB may exhibit structural differences as compared to CypA during transition state catalysis [191]. Our FEP/MC simulations have indicated that 2 takes advantage of these subtle differences via different binding motifs that fine-tune their selectivity for CypA by exclusively weakening their nonbonded interactions with the catalytic Arg63 and Asn110 residues in CypB. Relative free energies of binding, ΔΔGbind, given in Table 2 for the 2a-2c inhibitors were computed in both CypA and CypB using the MC/FEP transformation sequence given in Figure 9 and were found to yield excellent agreement with the experimental free-energy differences derived from the Ki protease-free PPIase assay at pH 7.8 and 283K [113, 189]. Figure 10 shows two binding modes for 2a in the overlaid CypA and CypB active sites where the lighter colored structure is the preferred binding conformation in CypA and the darker structure is favored in CypB. It is clear from the figures that the major difference is the orientation of the indanyl ring: CypB prefers a binding motif where the indanyl ring is located in a hydrophobic sub-binding pocket, while CypA has the indanyl ring pointing up into a polar region with the adjacent carbonyl oxygen oriented towards His54 (although the nonbonded interactions between 2a and His54 are weak as the total energy is −1.7 kcal/mol).

Fig. 9.

Transformation sequence used in the FEP simulations for the aryl 1-indanylketone-based compounds (2).

Table 2.

MC/FEP Results for the Mutation of Aryl 1-indanylketone Inhibitors (2)

| Compd | ΔΔGbind (calc) | ΔΔGbind (exptl) a | Ki, (μM)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| CypA | |||

| 2a | −0.61 ± 0.55 | −0.67 | 0.52 ± 0.15 |

| 2b | −1.44 ± 0.69 | −0.98 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 2c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| CypB | |||

| 2a | 1.51 ± 0.64 | > 1.38 | > 100 |

| 2b | 0.19 ± 0.58 | 0.19 | 12 ± 5 |

| 2c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 ± 0.9 |

Calculated from ΔΔGbind = RT ln [Ki(2x)/Ki(2c)] at 283 K.

Experimental Ki values from ref. [113].

Fig. 10.

Overlaid CypA and CypB active sites with inhibitor 2a bound at the active sites as predicted by BOMB. Nearby waters removed for clarity. The lighter colored structure is the preferred binding conformation in CypA and the darker structure is favored in CypB.

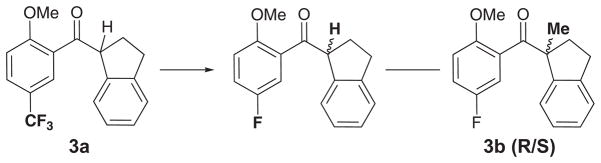

Further variations in the aryl 1-indanylketone scaffold included the substitution of the biphenyl ring with a single phenyl moiety (3 from Fig. 8) that also yielded selectivity between CypA and CypB. For example, compound 3a is ca. 10-fold more selective for CypA with a Ki value of 10 ± 2 μM compared to >100 μM in CypB. MC/FEP mutations were carried out for 3a and the enantiomeric 3b compounds as shown in Figure 11 and good agreement with the experimental ΔΔGbind values was found (Table 3). Figure 12 shows comparable binding modes for 3a in the overlaid CypA and CypB active sites with the indanyl ring pointing up into the polar active site saddle region in an orientation similar to that of 2a in CypA. AUTODOCK 4.2 calculations predicted binding poses for 3a in CypA and CypB similar to that of BOMB and the most favorable binding modes of 2a [189].

Fig. 11.

Transformation sequence used in the FEP simulations for the aryl 1-indanylketone-based compounds (3).

Table 3.

MC/FEP Results for the Mutation of Aryl 1-indanylketone Inhibitors (3)

| Compd | ΔΔGbind (calc) | ΔΔGbind (exptl)a | Ki, (μM)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| CypA | |||

| 3a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10 ± 2 |

| (S)-3b | 4.64 ± 0.24 | > 1.29 | > 100 |

| (R)-3b | −0.88 ± 0.21 | −0.16 | 7.5 ± 1.5 |

| CypB | |||

| 3a | 0.0 | 0.0 | > 100 |

| (S)-3b | 0.09 ± 0.21 | - | > 100 |

| (R)-3b | −0.34 ± 0.25 | < −0.52 | 40 ± 10 |

Calculated from ΔΔGbind = RT ln [Ki(3x)/Ki(3a)] at 283 K.

Experimental Ki values from ref [113].

Fig. 12.

Overlaid CypA and CypB active sites with inhibitor 3a bound at the active sites as predicted by BOMB. Nearby waters removed for clarity. The lighter colored structure is the preferred binding conformation in CypA and the darker structure is favored in CypB.

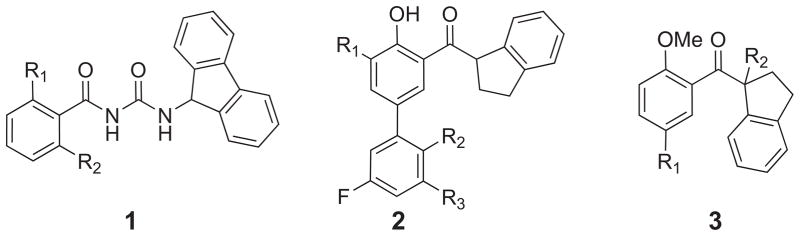

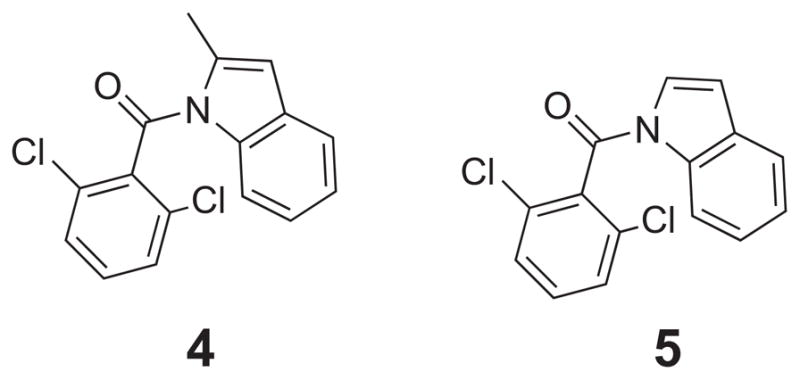

Lead Generation and Optimization of New Cyclophilin Inhibitors

New compounds are proposed in this study that build upon the FEP/MC modeling of the acyl urea, 1, and keto indane, 2 and 3, series of compounds. The analysis of the differential binding of the biphenyl keto indane to either CypA or CypB suggests a suboptimal binding of the indane into the S1 pocket of CypA with a preferential orientation of the indane ring in a hydrophobic pocket formed adjacent to Arg55 and formed by Ala 101, Asn 149, and Gly150. The 2-methyl indole 4 and indole 5 compounds (Fig. 13) are proposed to address the following two items: 1) the twisted ketones from the Fischer group [113, 183, 184] utilize a dihydroindane system with the proposal that this twist mimics the acyl-prolyl conformation and 2) the 2,6-dichlorobenzamide of compound 1 has also been suggested to mimic this same acyl-prolyl orientation. In addition, the methyl group in 4 should further hinder rotation. Variations proposed on these initial compounds include traditional analog design examining the role of the di-ortho substitution, and the effect of hetaryl ring variation. Structure based drug design strategies include incorporation of an acidic functional group to explore the possibility of these compounds binding in the electropositive pocket formed by His54 and Arg55, as well as the possibility of bridging from this electropositive pocket to the S2 pocket. Implementation of cyclic amine compounds to mimic the normal proline ring was anticipated as exploiting the normal binding preferences for this area. Utilizing either non-substituted or trans-4-hydroxy substituted variations will allow well established variations on the proline ring to be exploited in this system.

Fig. 13.

1-(2,6-dichlorobenzamido) indole cores 4 and 5.

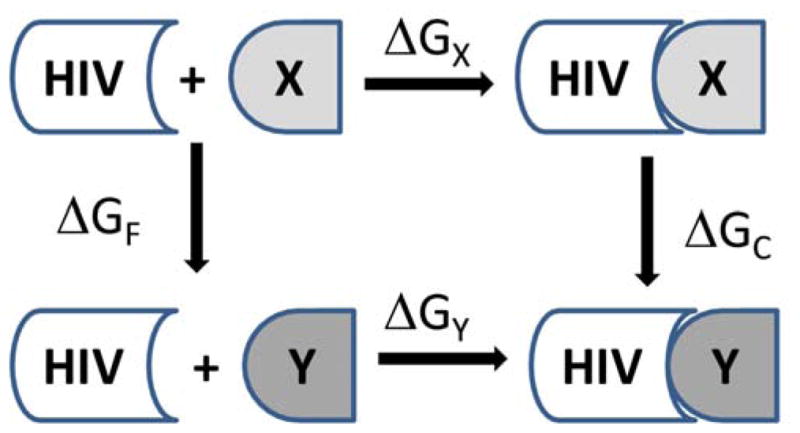

The general approach to be taken for the calculation of new inhibitors is illustrated in Fig. 14, which was adapted from a recent review from Jorgensen [9]. Lead generation and optimization begins by using our computational models of CypA and CypB and the program BOMB to grow desired analogues in the binding site by adding layers of substituents to a core such as urea. BOMB utilizes scoring functions in a similar fashion to docking programs to predict energies. The use of a docking program, such as AUTODOCK, will validate poses and suggest different starting positions. FEP/MC refinements are carried out and include chlorine and methyl scans on all hydrogens located on the cores; promising sites are investigated with additional small group substituents. An ADME filter, QikProp [192], is then utilized to further filter favorably predicted compounds prior to synthesis with appropriate pharmacokinetic and physicochemical characteristics, for example octanol/water partition coefficient (log Po/w), aqueous solubility (log S), brain/blood partition coefficient (log BB), Caco-2 and MDCK cell permeabilities, and the occurrence of unstable functionalities and metabolites.

Fig. 14.

Schematic outline for proposed structure-based computational and experimental lead discovery and optimization effort.

Our FEP/MC calculations of 4 → 5 in CypA found the relative free energy of binding, ΔΔGbind, for the mutation where the methyl group is transformed into a H atom, to be −1.29 kcal/mol. A negative value for ΔΔGbind indicates that the hydrogen on the indole ring is preferred and distorts the acyl geometry less. A negative ΔΔGbind value of −1.47 kcal/mol was also computed for the 4 → 5 MC/FEP mutation in CypB which further emphasizes the preference for the H atom. The discrepancy in the binding affinity can be attributed to space requirements for the methyl group within the active site that resulted in an unfavorable docking motif for 4 as compared to 5; the BOMB program predicted a ~ 4–5 kcal/mol energetic preference for 5 in both cyclophilins.

Additional variations of 4 and 5 in CypA and CypB were computed using the FEP/MC calculations where the 2,6-dichlorophenyl ring had the Cl atoms mutated to multiple combinations of Cl, F, and H atoms. The results are given in Table 4 and indicate that a single Cl or no Cl atoms on the phenyl ring should yield an improved free energy of binding in CypA. A positive ΔΔGbind value (kcal/mol) means R1 = R2 = Cl was preferred, and a negative value means the new mutation is preferred. In the present calculations the R1 and R2 positions are not equivalent as they do not interconvert during the MC simulation requiring separate simulations for each “conformer.” If only one equivalent position is energetically preferred, then a penalty of RT ln 2 (0.6 kcal/mol) can be expected for loss of one rotameric state upon binding. For example, R1 = Cl and R2 = F is favored by −0.24 kcal/mol in CypA as compared to R1 = R2 = Cl in compound 4 (Table 4); the R1 substituent points into the hydrophobic pocket and R2 points towards the bulk phase water. However, the opposite conformation of R1 = F and R2 = Cl is not as favorable as two Cl atoms on the phenyl moiety with an overall ΔΔGbind of 0.33 kcal/mol. Interestingly, the calculations predicted a potential preference for the R1 = R2 = H derivative in CypA over CypB, e.g., ΔΔGbind values of −2.02 and 1.76 kcal/mol for compound 5, respectively, which could indicate a potential compound for selective inhibition between the cyclophilins.

Table 4.

ΔΔGbind (kcal/mol) MC/FEP Results for Mutation of the Indole Derivatives 4 and 5

| R1 | R2 | 4 (CypA) | 5 (CypA) | 4 (CypB) | 5 (CypB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl | Cl | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cl | F | −0.24 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.44 |

| F | Cl | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.74 |

| F | F | 0.41 | −0.27 | 0.66 | 0.90 |

| Cl | H | 0.80 | −0.79 | 0.89 | 0.20 |

| H | Cl | −1.06 | −1.54 | −0.91 | 2.06 |

| H | H | −1.68 | −2.02 | 0.52 | 1.76 |

Positive ΔΔGbind value means R1 = R2 = Cl was preferred, and negative means new mutation is preferred. R1 signifies that the substituent is pointing in towards the enzyme and R2 is pointing out towards the aqueous solvent environment.

Chemical Synthesis

As a preliminary assessment of the predictive capabilities of the FEP/MC method on HIV inhibition, experimental synthesis and biological testing of the R1 = R2 = Cl derivative, 5, was carried out. Compound 5 was prepared with a variation of the procedure of Itahara et al. [193]. Indole (234.3 mg, 2.0 mmol) was dissolved into 5.0 mL of THF (anhydrous, SureSeal) and cooled to 0 °C. A 0.6 M solution of NaHMDS (3.5 mL, 2.2 mmol) was added slowly and a slight yellow solution formed. This mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 35 min. Neat 2,6-dichlorobenzoyl chloride (0.286 mL, 2.0 mmol) was added in one portion at 0 °C, and resulted in a green mixture, this was then warmed to 23 °C, and stirred for an additional 12 h. The resultant mixture was taken up into 25 mL of hexanes and 25 mL of NH4Cl (sat, aq). The aqueous layer was washed an additional 2 times with 25 mL portions of hexanes. The combined organic layers were washed 2 times with NaCl (sat, aq), dried (Na2SO4), decanted, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford 0.70 g of a dark oil. This oil was dissolved into 1.0 mL of EA and loaded onto a silica gel column and eluted with a 10:1 isocratic gradient of Hex:EA. Appropriate fractions were combined and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure; the resultant solid was recrystallized from hexanes to give 301.0 mg of white needles (51 %).

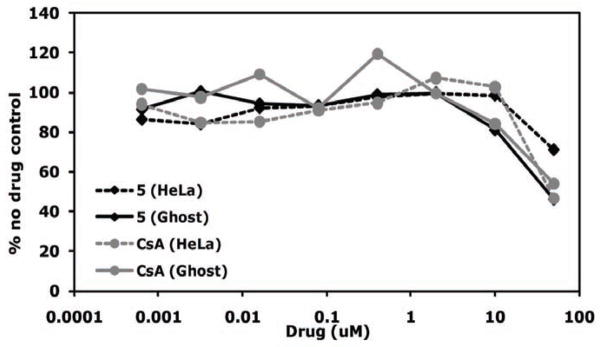

Toxicity of CypA Inhibitors

Because HeLa and GHOST cells are adherent cell lines and easier to use than primary T cells or macrophages, initial screening of 5 as a potential CypA inhibitor was performed in these cell lines. Multiple concentrations (0.00064 – 50 μM) of CsA and 5 were tested for cellular toxicity in HeLa and GHOST cells in duplicate with the XTT cell viability assay (Fig. 15). Only viable cells cleave tetrazolium salt XTT into an orange formazan dye, which can be quantified by an ELISA plate reader [194]. CsA, which leads to significant toxicity at 10 μM and above (Z. Ambrose, unpublished data), was run in parallel as a control. A similar pattern of toxicity was seen between CsA and 5 in each cell line. CsA was significantly toxic at 50 μM in HeLa cells and at 10 μM in GHOST cells, as expected. 5 showed no toxicity up to 50 μM in HeLa cells and showed significant toxicity only at 50 μM (46% viability) and slight toxicity at 10 μM (81% viability) in GHOST cells.

Fig. 15.

Toxicity of CypA inhibitors in HeLa and GHOST cells. Cells were incubated in duplicate in the presence or absence of 5-fold dilutions of inhibitor. Cell viability was measured by the XTT assay on an ELISA plate reader. Duplicate O.D. values were averaged and the value for cells in the absence of drug was set at 100%. Data are plotted as a percentage of the no drug control. Graphs are representative of 2 independent experiments.

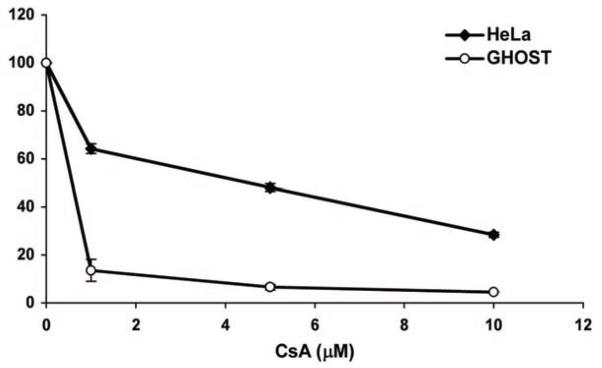

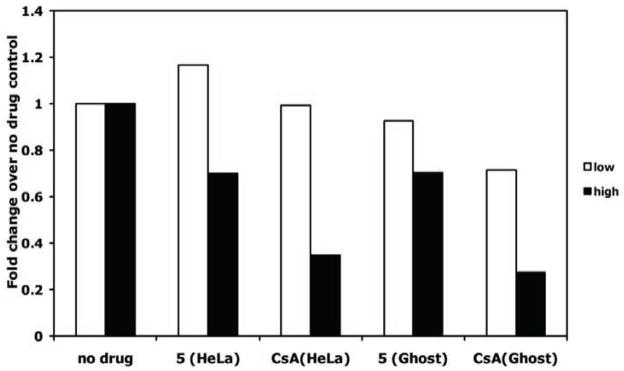

HIV-1 Inhibition by CypA Inhibitors in HeLa and GHOST Cells

In HeLa cells, inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity is not affected by CsA concentrations less than 5 μM (Fig. 16). However, much lower concentrations of CsA can reduce viral infectivity in GHOST cells, similar to what is seen in macrophages (Z. Ambrose, submitted). Therefore, we decided to test concentrations of the potential CypA inhibitor in both cell lines at a nontoxic concentration of 10 μM and at a lower concentration of 0.2 μM (Fig. 17). As expected, 10 μM CsA led to HIV-1 inhibition by approximately 70% in both HeLa and GHOST cells, whereas 0.2 μM led to no reduction in viral infectivity in HeLa cells and 30% reduction in GHOST cells. Compound 5 showed no appreciable inhibition of HIV-1 in HeLa or GHOST cells at 0.2 μM but showed 30% inhibition in both cell lines at 10 μM.

Fig. 16.

Inhibition of HIV-1 in HeLa and GHOST cells with different concentrations of CsA. Cells were infected with HIV-1 in duplicate in the presence or absence of 0, 1, 5, and 10 mM CsA. Infectivity after 48 hours was measured by luciferase activity and the duplicates averaged. Infections in the absence of CsA was set to 100%. Error bars represent standard deviations. Representative of 3 independent experiments.

Fig. 17.

Inhibition of HIV-1 by CypA inhibitors in HeLa and GHOST cells. Cells were infected with HIV-1 in duplicate in the presence or absence of the highest concentration that did not cause significant toxicity: 10 mM for both compounds. Cells were also incubated with 50-fold lower drug (0.2 μM). Infectivity after 48 hours was measured by luciferase activity and the duplicates averaged. Averaged luciferase values for each drug concentration were divided by the averaged value of no drug control cells, giving a fold-change in infectivity over no drug control.

CONCLUSIONS

Free energy perturbation simulations rooted in statistical mechanics have been successful in guiding drug lead generation and optimization for multiple therapeutic targets despite the technical challenges and limitations associated with the method. A review was provided herein detailing the use of FEP/MD and FEP/MC calculations in the identification and development of HIV-1 protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Early FEP simulations carried out ‘alchemical’ mutations of peptide based inhibitors of HIV-1 PR to elucidate structural relationships tied to binding affinity and drug resistance. Multiple FEP-based studies highlighted that in designing future inhibitors, improved main-chain interactions alone were insufficient for enhancing binding to HIV-1 PR and hydrophobic interactions were an essential component to be considered. Technical advances and a greater understanding of FEP calculations from the HIV-1 PR studies laid the path for more recent accomplishments in FEP guided design of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. A diverse set of novel HIV-1 RT inhibitors, e.g., pyrimidinyl [100], triazinyl-amines [100], bicyclic heterocycles [104], and azole [70, 105] based NNRTI compounds, have been reported and proven the FEP/MC method to be an effective and efficient CADD practice.

In addition, a discussion was provided of our ongoing work utilizing FEP/MC to construct small molecule leads that display activity against cyclophilins in order to prevent HIV-1 infection and replication in various cell types. Our most recent study [189] explored nanomolar to micromolar binding affinities for a varied set CypA and CypB inhibitors based on acyl urea, 1, and aryl 1-indanylketone, 2 and 3, small molecule scaffolds originally reported by Li [187] and Fischer [113]. The computed values were in close agreement with experimental values derived from IC50 and Ki enzyme assay results. The binding affinity and selectivity of the compounds were determined to be primarily the result of favorable nobonded stabilization of conserved Arg and Asn active site residues in CypA and CypB. Given the proposed interactions of 1 – 3 with the cyclophilins, a brief series of hybrid structures were computed and prepared that explored retention of the 2,6-dichlorobenzimide as an S1′ and prolyl acyl mimic, and exploring hydrophobic S2 variations that would more synthetically accessible and arguably more chemically and biochemically stable than a ketodihydroindole or an acyl urea. FEP/MC calculations predicted a preference for compounds based on 2-methyl indole 4 and indole 5 cores. The computationally favored compound 5 was prepared and screened initially for overt toxicity and then for HIV-1 inhibition. 5 showed a dose-dependent inhibition of HIV-1 infection in both HeLa and GHOST cells. While the effect was not as dramatic as that seen for CsA and was not greater in the more sensitive GHOST cell line, the results are encouraging and modification to the structure of this compound could lead to greater activity and, hopefully, similar or less cellular toxicity. From a broader health perspective, novel compounds displaying selective inhibition of CypA or CypB could potentially be extended to treatments of other diseases beyond HIV, including HCV [159, 195–201], multiple cancers [202], e.g., breast [203, 204], pancreatic [205], and non-small cell lung cancers [206], and inflammatory diseases [207], such as rheumatoid arthritis [208].

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

Cyclophilin protein modeling setup

Initial Cartesian coordinates for the protein-ligand structures were generated with the molecule growing program BOMB starting from the PDB files 1awq [209] for CypA and 1cyn [210] for CypB; the existing complexed ligands were removed and replaced by cores such as formaldehyde to grow the desired analogues in the binding site. The present models include one active site, the inserted ligand, and all crystal structure residues. Terminal residues were capped with acetyl or N-methylamine groups. The system was then subjected to conjugate-gradient energy minimization in order to relax the contacts between protein residues and the ligand. The total charge of the system was set to zero by adjusting the protonation states of a few residues furthest away from the center of the system. The entire system was solvated with 25-Å caps containing 1250 and 2000 TIP4P water molecules [211] for the protein complexes and unbound ligands, respectively; a half-harmonic potential with a force constant of 1.5 kcal mol−1 A−2 was applied to water molecules at a distance greater than 25 Å. The MC/FEP calculations were executed with MCPRO [212]. The energetics of the systems were classically described with the OPLS-AA force field for the protein and OPLS/CM1A for the ligands [213]. For the MC simulations, all degrees of freedom were sampled for the ligands, while TIP4P water molecules only translated and rotated; bond angles and dihedral angles for protein side chains were also sampled, while the backbone was kept fixed after the conjugate-gradient relaxation. Each mutation window for the unbound ligands in water consisted minimally of 20 million (M) configurations of MC equilibration followed by 40M configurations of averaging. For the bound calculations, the equilibration period was minimally 5 M configurations of solvent only moves, followed by 10 M configurations of full equilibration, followed by 20 M configurations of averaging. All MC simulations were carried out at 25 °C. Our recent QM/MM study of catalytic antibody 4B2 used a similar computational setup and produced close agreement with experimental rate data [214].

Docking Calculations

In some cases AUTODOCK 4.2 [215] was used to dock the full inhibitors (not cores) into the crystal structures for verification of the binding conformations predicted by BOMB. AutoDockTools (ADT) was used to prepare, run, and analyze the docking simulations. The rigid roots of each ligand were defined automatically and the amide bonds were made non-rotatable. Polar hydrogens were added and Gasteiger charges assigned; non-polar hydrogens were subsequently merged. A grid was centered on the catalytic active site region and included all amino acid residues within a box size set at x = y = z = 40 Å. AutoGrid 4 was used to produce grid maps with the spacing between the grid points at 0.375 Å. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) was chosen to search for the best conformers. During the docking process, 50–100 conformers was considered for each compound. The population size was set to 150 and the individuals initialized randomly. The maximum number of energy evaluation was set up to 2500000; default docking parameters were primarily used, for example: maximum number of generations to 27000, maximum number of top individual that automatically survived set to 1, mutation rate of 0.02, crossover rate of 0.8, step sizes are 2 Å for translations, 50° for quaternions, and 50° for torsions, and a cluster tolerance of 2 Å is employed. The lowest energy clusters were utilized in the structural analysis of predicted docked poses.

EXPERIMENTAL MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, culture conditions, and viruses

293T, HeLa and GHOST cells were cultured at 37° C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), and 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.3 mg/ml of L-glutamine (Invitrogen).

HIV-1NL4-3 luciferase reporter virus pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) was made by transfection of 293T cells with the pNLdE-luc reporter construct [155] and pL-VSV-G plasmid [216], using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus was harvested and titered on GHOST cells.

Cell viability assay

2 × 103 HeLa or GHOST cells were plated in sterile, tissue culture-treated flat-bottom 96-well plates the night before the experiment. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in duplicate with 5-fold dilutions of each synthesized drug and CsA (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH). Drug stocks were made in DMSO and were diluted more than 400-fold in medium. Multiple wells with medium without drug were used as controls. The XTT assay (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used by addition of XTT labeling reagent for 4 hours, followed by addition of the electron-coupling reagent overnight. The plate was read on a SpectroMax ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 570 nM.

Virus inhibition assay

2 × 104 HeLa or GHOST cells were plated in 24-well plates the night before the experiment. Cells were infected in duplicate with HIV-1 at a multiplicity of infection of 0.02 in the presence or absence of CypA inhibitors, including CsA. Two wells of cells were left uninfected and without drug background controls for the assay. After 2 hours of incubation, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and new medium with or without drug was replaced. Cell lysates were harvested 48 hours later with Glo Lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and measured for luciferase activity with the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega) on a Wallac microbeta luminometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Chemical synthesis

All reactions were conducted in dry glassware and under an atmosphere of argon unless otherwise noted. Melting points were determined on a MelTemp apparatus and are uncorrected. All proton NMR spectra were obtained with a 500 MHz Oxford spectrospin cryostat, controlled by a Bruker Avance system, and were acquired using Bruker Topsin 2.0 acquisition software. Acquired FIDs were analyzed using MestReC 3.2. Elemental analyses were conducted by Atlantic Microlabs and are ± 0.4 of theoretical. All 1H NMR spectra were taken in CDCl3 unless otherwise noted and are reported as ppm relative to TMS as an internal standard. Coupling values are reported in Hertz.

2,6-dichlorobenzamido-1H-indole (5): MP: 125–127 °C, MP lit [193]: 131–131 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.67 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.52 (m, 4H) 7.40 (m, 1 H) 6.84 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 0.2 Hz, 1H) consistent with the literature [193]. Elemental analysis calculated (%): C 62.09, H 3.13, N 4.83, Cl 24.44; found C 61.65, H 3.08, N 4.77, Cl 24.00.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is expressed to Auburn University and the Alabama Supercomputer Center for support of this research (O. A.). This project was supported by Grant 1 UL1 RR024153 (Z. A.) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/.

References

- 1.Jorgensen WL. The Many Roles of Computation in Drug Discovery. Science. 2004;303:1813–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1096361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michel J, Foloppe N, Essex JW. Rigorous free energy calculations in structure-based drug design. Mol Inf. 2010;29:570–8. doi: 10.1002/minf.201000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noy E, Senderowitz H. Molecular simulations for the evaluation of binding free energies in lead optimization. Drug Dev Res. 2010;72:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinbrecher T, Labahn A. Towards Accurate Free Energy Calculations in Ligand Protein-Binding Studies. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:767–85. doi: 10.2174/092986710790514453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durrant JD, McCammon JA. Computer-aided drug-discovery techniques that account for receptor flexibility. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:770–4. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht D. Applications of machine learning and computational intelligence to drug discovery and development. Drug Dev Res. 2010;72:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woods CJ, Malaisree M, Hannongbua S, Mulholland AJ. A waterswap reaction coordinate for the calculation of absolute proteinligand binding free energies. J Chem Phys. 2011;134:054114/1–/13. doi: 10.1063/1.3519057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis RA. Computer-aided drug design 2007–2009. Chem Modell. 2010;7:213–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorgensen WL. Efficient Drug Lead Discovery and Optimization. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:724–33. doi: 10.1021/ar800236t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitera JW. Current developments in and importance of highperformance computing in drug discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2009;12:388–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato M, Braun-Sand S, Warshel A. Challenges and progresses in calculations of binding free energies - what does it take to quantify electrostatic contributions to protein-ligand interactions? In: Stroud RM, Finer-Moore J, editors. Computational and Structural Approaches to Drug Discovery. 2008. pp. 268–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Åqvist J, Luzhkov VB, Brandsdal BO. Ligand Binding Affinities from MD Simulations. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:358–65. doi: 10.1021/ar010014p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massova I, Kollman PA. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspectives in Drug Discovery and Design. 2000;18:113–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michel J, Essex JW. Prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity by free energy simulations: Assumptions, pitfalls and expectations. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2010;24:639–58. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klebe G. Virtual ligand screening: strategies, perspectives and limitations. Drug Discovery Today. 2006;11:580–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider G. Virtual screening: an endless staircase? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:273–6. doi: 10.1038/nrd3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vacek G, Mullally D, Christensen K. Trends in High-Performance Computing Requirements for Computer-Aided Drug Design. Curr Comput Aided-Drug Des. 2008;4:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drie JH. Computer-aided drug design: The next 20 years. J Comput-Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilson MK, Zhou HX. Calculation of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. Annu Rev BioPhys BioMol Struct. 2007;36:21–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chodera JD, Mobley DL, Shirts MR, Dixon RW, Branson K, Pande VS. Alchemical free energy methods for drug discovery: progress and challenges. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2011;21:150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mobley DL, Dill KA. Binding of Small-Molecule Ligands to Proteins: “What You See” Is Not Always “What You Get”. Structure. 2009;17:489–98. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simonson T, Archontis G, Karplus M. Free Energy Simulations Come of Age: Protein-Ligand Recognition. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:430–7. doi: 10.1021/ar010030m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christ CD, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. Basic ingredients of free energy calculations: A review. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:1569–82. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pohorille A, Jarzynski C, Chipot C. Good Practices in Free-Energy Calculations. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:10235–53. doi: 10.1021/jp102971x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kollman PA. Free energy calculations: Applications to chemical and biochemical phenomena. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2395–417. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng Y, Roux B. Calculation of Standard Binding Free Energies: Aromatic Molecules in the T4 Lysozyme L99A Mutant. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:1255–73. doi: 10.1021/ct060037v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyce SE, Mobley DL, Rocklin GJ, Graves AP, Dill KA, Shoichet BK. Predicting Ligand Binding Affinity with Alchemical Free Energy Methods in a Polar Model Binding Site. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:747–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erion MD, Dang Q, Reddy MR, et al. v. Structure-Guided Design of AMP Mimics That Inhibit Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase with High Affinity and Specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15480–90. doi: 10.1021/ja074869u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy MR, Erion MD. Calculation of Relative Binding Free Energy Differences for Fructose 1,6-Bisphosphatase Inhibitors Using the Thermodynamic Cycle Perturbation Approach. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6246–52. doi: 10.1021/ja0103288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinbrecher T, Hrenn A, Dormann KL, Merfort I, Labahn A. Bornyl (3,4,5-trihydroxy)-cinnamate - An optimized human neutrophil elastase inhibitor designed by free energy calculations. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:2385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2010 www.unaids.org.

- 32.Hazuda D, Iwamoto M, Wenning L. Emerging Pharmacology: Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Integration. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:377–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shet A, Berry L, Mohri H, et al. Tracking the Prevalence of Transmitted Antiretroviral Drug-Resistant HIV-1: A Decade of Experience. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:439–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219290.49152.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richman DD, Morton SC, Wrin T, et al. The prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18:1393–401. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131310.52526.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore JP, Stevenson M. New targets for inhibitors of HIV-1 replication. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:40–9. doi: 10.1038/35036060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F, Goila-Gaur R, Salzwedel K, et al. PA-457: A potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13555–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234683100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prada N, Markowitz M. Novel integrase inhibitors for HIV. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1087–98. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.501078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehellou Y, Clercq ED. Twenty-Six Years of Anti-HIV Drug Discovery: Where Do We Stand and Where Do We Go? J Med Chem. 2010;53:521–38. doi: 10.1021/jm900492g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flexner C. HIV drug development: the next 25 years. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:959–66. doi: 10.1038/nrd2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbaro G, Scozzafava A, Mastrolorenzo A, Supuran CT. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: Current State of the Art, New Agents and Their Pharmacological Interactions Useful for Improving Therapeutic Outcome. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1805–43. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirchmair J, Distinto S, Liedl KR, et al. Development of anti-viral agents using molecular modeling and virtual screening techniques. Infectious Disorders: Drug Targets. 2011;11:64–93. doi: 10.2174/187152611794407782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vadivelan S, Deeksha TN, Arun S, et al. Virtual screening studies on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors to design potent leads. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:851–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curreli F, Zhang H, Zhang X, et al. Virtual screening based identification of novel small-molecule inhibitors targeted to the HIV-1 capsid. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nichols SE, Domaoal RA, Thakur VV, Tirado-Rives J, Anderson KS, Jorgensen WL. Discovery of Wild-Type and Y181C Mutant Non-nucleoside HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors Using Virtual Screening with Multiple Protein StructuRes. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:1272–9. doi: 10.1021/ci900068k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang W, Kollman PA. Free energy calculations on dimer stability of the HIV protease using molecular dynamics and a continuum solvent model. J Mol Biol. 2000;303:567–82. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Morin P, Wang W, Kollman PA. Use of MM-PBSA in reproducing the binding free energies to HIV-1 RT of TIBO derivatives and predicting the binding mode to HIV-1 RT of efavirenz by docking and MM-PBSA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5221–30. doi: 10.1021/ja003834q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ode H, Neya S, Hata M, Sugiura W, Hoshino T. Computational Simulations of HIV-1 Proteases-Multi-drug Resistance Due to Nonactive Site Mutation L90M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7887–95. doi: 10.1021/ja060682b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barreiro G, Guimaraes CRW, Tubert-Brohman I, Lyons TM, Tirado- Rives J, Jorgensen WL. Search for Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Using Chemical Similarity, Molecular Docking, and MM-GB/SA Scoring. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:2416–28. doi: 10.1021/ci700271z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guimarães CRW, Cardozo M. MM-GB/SA Rescoring of Docking Poses in Structure-Based Lead Optimization. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:958–70. doi: 10.1021/ci800004w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wittayanarakul K, Hannongbua S, Feig M. Accurate prediction of protonation state as a prerequisite for reliable MM-PB(GB)SA binding free energy calculations of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:673–85. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansson T, Åqvist J. Estimation of Binding Free Energies for HIV Proteinase Inhibitors by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Protein Eng. 1995;8:1137–44. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.11.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hultén J, Bonham NM, Nillroth U, et al. Cyclic HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors Derived from Mannitol: Synthesis, Inhibitory Potencies, and Computational Predictions of Binding Affinities. J Med Chem. 1997;40:885–97. doi: 10.1021/jm960728j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sham YY, Chu ZT, Tao H, Warshel A. Examining methods for calculations of binding free energies: LRA, LIE, PDLD-LRA, and PDLD/S-LRA calculations of ligands binding to an HIV protease. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 2000;39:393–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan JJ, Cong XJ, Hu LM, Wang CX, Jia L, Liang XJ. Therapeutic strategies underpinning the development of novel techniques for the treatment of HIV infection. Drug Discovery Today. 2010;15:186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jorgensen WL, Ravimohan C. Monte Carlo simulation of differences in free energies of hydration. J Chem Phys. 1985;83:3050–4. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong CF, McCammon JA. Dynamics and design of enzymes and inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:3830–2. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bash PA, Singh UC, Langridge R, Kollman PA. Free energy calculations by computer simulation. Science. 1987;236:564–8. doi: 10.1126/science.3576184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]