Abstract

We develop optical trapping methodology to precisely measure the force generated by motor-proteins on single organelles of unknown size in cell extract. Native motor-complexes can now be interrogated functionally, overcoming limitations of assays with purified motors coated on artificial beads. Forces, number and activity of kinesin-1 is measured on motile lipid droplets isolated from liver of normal and fasted rats to detect a correlation between metabolic state and kinesin-1 activity.

Cytoskeletal motors transport organelles as cargo along actin and microtubule (MT) filaments1. A direct measure of motor-activity is the force generated to transport cargo, and can be measured by in vitro optical trapping of plastic beads coated with purified motors2-3. However, such simplified assays have severe limitations because the in vivo configuration of motors cannot be reproduced on the artificial surface of a bead. While in vivo optical trapping has been reported, there is disagreement in the forces measured between different in vivo reports4-7, and also between in vivo and in vitro reports. Issues related to centering of the optical trap and the variable size of organelles complicate interpretation of in vivo trapping (Supplement). An attractive “middle-path” is to probe force-generation of single organelles in cell extract8-9. Cell-extract assays could probe motors existing in a native-like state on real cellular cargos, and have multiple advantages (Supplement). Such assays may not exactly represent in vivo motility because motor-function can get modified, and cytosolic factors regulating motors may not be available in cell extract. Nevertheless, if quantitative optical trapping is possible in cell extract, it could significantly enhance our understanding of how motors work in cells.

The restoring force (FTRAP) on a cargo pulled out to distance (X) from the centre of a trap2 functioning as a linear spring of stiffness KTRAP is (Fig. 1a)

| (1) |

The maximum force exerted by motors (FMOTORS) is

| (2) |

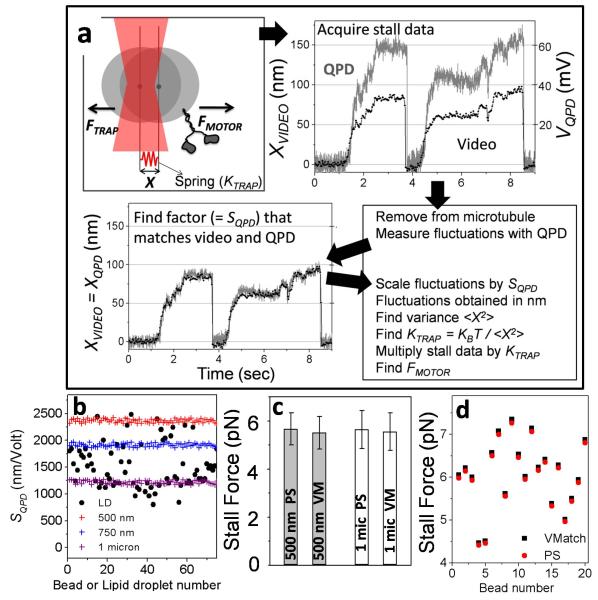

FIGURE 1. Video-matching (VMatch) method for quantitative optical trapping of cellular organelles.

(a) Top left The displacement (X) of a motor-driven cargo against an optical trap (red focused beam) is shown schematically. The trap works as a spring whose stiffness (KTRAP) must be determined to measure FMOTOR. The stall force record acquired simultaneously with a QPD and video camera for a plus-moving lipid droplet is shown. The two data sets are then matched to find the calibration factor of the QPD (= SQPD). This value of SQPD is used to calculate variance in position (<X2>) of the thermally fluctuating cargo in trap. KTRAP and FMOTOR are subsequently determined from <X2>.

(b) Variation in QPD calibration factor (SQPD) for beads of different mean diameters and LDs. SQPD is determined for beads by moving beads stuck to coverslip with a piezo stage. SQPD is determined for individual LDs using the VMatch method.

(c) The stall force of kinesin-1 coated on 0.5 micron and 1 micron diameter beads was measured by the power spectrum (PS) VMatch (VM) methods. We recorded 59 stalls from 40 beads of 500nm and 119 stalls from 82 beads of 1micron. Stall force on 0.5 micron beads was 5.67±1.1(VMatch) and 5.51±1.0(PS). Stall force on 1 micron beads was 5.74±0.9 (VMatch) and 5.68±1.1 (PS). All values are mean±sd. One-way ANOVA showed no significant difference at the 0.05 level [F(3,353) = 0.84; p = 0.47] between these values.

(d) The stall force of kinesin-1 was measured at single molecule limit on 20 different beads (0.5 micron mean diameter) by the PS and VMatch methods.

Here X = XSTALL when motors “stall” against the trap (Fig. 1a). KTRAP is determined from thermal fluctuations in position of a trapped object using the power spectrum (PS) or variance methods2-3. These fluctuations must be sampled at high bandwidth using a quadrant photodiode detector (QPD; Supplementary Fig 1). Both methods require (directly or indirectly) the size of trapped cargo to be known precisely. However, the size of organelles in cell extract is variable. KTRAP depends on this size, varying ~6-fold between R = 0.5 to 3 μm, which is the size-range for many cellular organelles5,8. Hence, the estimation of KTRAP for organelles becomes unreliable.

KTRAP can be found from the variance <X2> in thermal fluctuations using equipartition of energy2-3

| (3) |

Here kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is temperature in Kelvin. The position fluctuations (X) must be known in real distance units (nanometers). A calibration factor (SQPD) that converts the QPD voltage fluctuations (VQPD) to distance fluctuations (XQPD) is therefore required

| (4) |

SQPD must be determined precisely because the squared term in Eqn 4 amplifies small errors. A strong dependence of SQPD on size of the trapped object (Fig. 1b) precludes use of the variance method on organelles of unknown size.

Here we develop a simple method (Fig 1a) to determine SQPD precisely for individual organelles of unknown size in cell extract, and therefore extend quantitative force-measurement to cellular organelles. Motor-driven stalls of an organelle are recorded simultaneously with QPD (as a voltage signal) and a video CCD camera (as a movie). We then trap the organelle away from MT to measure its thermal fluctuations (VQPD) in the QPD. The movie of stalls is then video-tracked to obtain the displacement (XVIDEO) of organelle in real distance units. The QPD stall (acquired earlier) is multiplied by that factor which minimizes the root-mean-squared difference between QPD and video record. This factor is the precise value of SQPD for that specific trapped organelle. With SQPD determined, <X2>, KTRAP and FMOTORS can be easily obtained from Eqns 4, 3 and 2. Fig 1b plots the values of SQPD determined in this manner for lipid droplets (LDs) extracted from rat liver (see later). The extremely large variation on LDs arising from variable size is clear (compare to variation for bead of certain size).

Note that while a slow (30 frames/sec) camera undersamples thermal fluctuations2, it precisely determines the horizontal plateau-like stalled position of the organelle (usually >0.5 sec long; see Fig. 1a). Further, video tracking algorithms are largely insensitive to organelle size (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, XVIDEO is the correct displacement irrespective of organelle size. We call this the Video-Matching method (VMatch) for motor force measurement. VMatch can quantify not just force, but also step sizes and dynamics (attachment/detachment) of motor-complexes on organelles with kilohertz time resolution. However, VMatch cannot calibrate a trap inside a cell, where possible cargo-attachment to MTs/actin would measure a composite stiffness of the trap along with these unknown attachments.

To test VMatch, we measured force of purified kinesin-1 on beads of known sizes (diameter 0.49±0.01μm and 0.99±0.04μm) by PS and variance methods. PS method could be used because the bead size was known (this is not true for organelles). The measured mean and SD of stall force for kinesin-1 was statistically same across beads for both methods (Fig. 1c). Therefore, VMatch measures the force for purified kinesin-1 correctly, regardless of cargo size. The stall force obtained by PS and VMatch methods on 20 beads showed point-to-point agreement for every kinesin molecule (Fig. 1d).

We next assayed motility of lipid droplets (Supplement) extracted from rat liver (inset, Fig. 2a) on MTs labeled at the minus-end8. Robust LD motility was observed (75% LDs moved when placed on MTs with the trap; online methods). An overwhelming majority of LDs (95% of motile fraction) moved towards plus-end of MTs (verified from multiple rats). LDs moved over long distance (Fig. 2a, Supplementary video 1) with velocity of 0.97±0.27 μm/sec (N = 90 LDs; mean±sd). Kinesin-1 is known to drive plus-directed motion of LDs5. We consistently detected kinesin-1 on LDs by Western blotting (inset, Fig. 2a; Supplement). Further, a specific peptide inhibitory to kinesin-1 reduced LD motility in dose-dependent manner, showing that LD motion is largely driven by kinesin-1 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

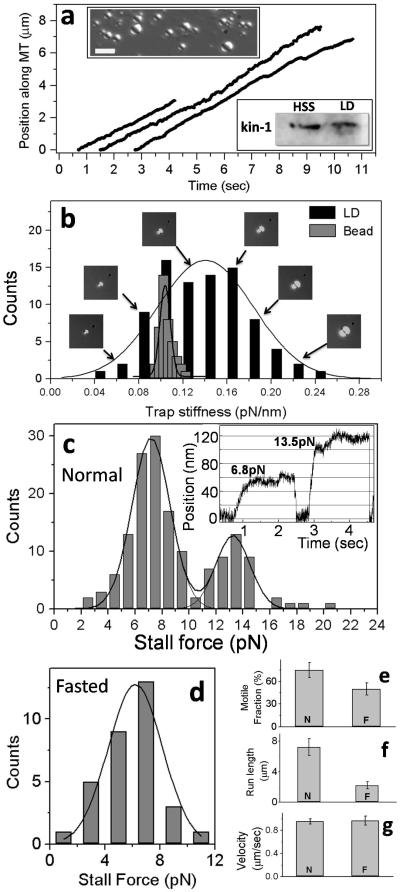

FIGURE 2. Motility and force measurement on lipid droplets extracted from rat liver.

(a) Representative video tracks of motile LDs in an in vitro motility assay at 1mM ATP. All LDs moved to MT plus-end. Inset DIC image of lipid droplets (refractile spheres) isolated from rat liver. Scale bar = 3 microns. Inset Western blot of proteins with kinesin-1 antibody using liver cytosol (HSS) and proteins extracted from purified LDs (LD). A specific band is detected for kinesin-1 at ~116kDa.

(b) Distribution of KTRAP for LDs (obtained by VMatch) and 1 micron beads (by PS method). Images of LDs that yielded specific values of KTRAP are also shown (arrows).

(c) Histogram of stall force for plus-moving LDs from normal liver using KTRAP determined individually for every LD by the VMatch method. Thick black line is a fit to sum of two unconstrained Gaussians (reduced χ2 = 2.42). Inset shows representative stalls of LDs corresponding to the 1st and 2nd peaks.

(d) Histogram of stall force for plus-moving LDs extracted from liver of rats fasted for 16-hrs. Thick black line is fit to a Gaussian. The peak position (6.2±1.7 pN; mean ± SD) likely represents single kinesin-1 force.

(e) Fraction of LDs moving on MTs from normal (N) and fasted (F) rats. There is significant reduction in motility upon fasting (p<0.001).

(f) Run length of plus runs for LDs from normal (N) and fasted (F) rats. There is significant reduction in run length upon fasting (p<0.0001).

(g) Velocity of LDs from normal (N) and fasted (F) rats. There is no change in velocity upon fasting (p=0.52)

We recorded 153 stalls from 87 LDs within a certain size range (roughly 0.4–2μm from visual comparison with beads of known size; insets Fig. 2a). A stall was counted8 when the LD showed velocity <10nm/sec for >0.5 sec. A histogram of KTRAP determined by VMatch for individual LDs over a range of sizes (Fig. 2b; representative LDs shown) exhibited large variation in KTRAP (SD = 0.05 pN/nm). This was in contrast to the narrow range of KTRAP for 1 micron beads obtained using the PS method (Superimposed histogram in Fig. 2b; SD = 0.006pN/nm for 1μm bead). Cargoes typically stall at XSTALL≈100nm in optical trap assays2,8,10. Using (FMOTORS = KTRAP · XSTALL), it is clear that the uncertainty in FMOTORS is low (~0.6pN) for beads but unacceptably high (~5pN) for LDs if an average value of KTRAP is used. This underscores the requirement of a method such as VMatch to measure KTRAP individually for every LD.

A histogram of stall force (Fig. 2c) showed peaks at 7.1±1.4 pN and 13.2±1.5 pN, indicating that the unitary kinesin force on LDs is ~7.1pN. This is within the in vitro range of stall force (5-8 pN) for purified kinesin-1 from different species2. The single kinesin-1 stall force for lipid droplets has SD comparable to stall force for kinesin-1 coated beads seen by us (SD~1.0pN; see caption of Fig. 1c) and others10. This SD largely reflects molecule-to-molecule variation between individual kinesin motors. A rough estimation of the diameter of LDs shows that the largest LDs are ~5 times (400%) larger than the smallest LDs (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the largest kinesin-coated bead is only 16% larger than the smallest bead (considering beads within 2σ; diameter = 0.99±0.04μm). Thus, VMatch measures kinesin’s force on LDs with precision comparable to beads in spite of the 25-fold larger size variation of LDs. Kinesin’s stall force has not been measured on organelles in cell extract before this work. Inside cells, conflicting values have been reported on LDs (1.1pN4, 2.6pN5,7 and ~3 and 6pN6).

LDs in liver are under constant lipolysis/re-esterification11 to generate very low density lipoprotein (VLDL). The observed kinesin motility could facilitate lipolysis5,12 by inducing fragmentation/dispersal of LDs. To investigate further we assayed force-generation and motility of LDs extracted from rats fasted for 16 hours, which leads to accumulation of lipid in the liver13. There was a complete absence of two-kinesin stalls in fasted-liver LDs (Fig. 2d), and the motile fraction (Fig. 2e) and run-length of LDs (Fig. 2f) was reduced. The single-kinesin stall force (Fig. 2d) and velocity of LDs (Fig. 2g) was unchanged. We observed that overall levels of kinesin-1 in liver remained unchanged on fasting (Supplementary Fig. 5). Since there are more LDs in the liver in fasted lipogenic state13, our results can be interpreted as less kinesin-1 per LD in fasted liver. However, other possibilities such as inactivation of LD-associated kinesin upon fasting exist, and remain to be investigated.

VMatch has several advantages over earlier published methods14-15 of trap calibration (detailed discussion in Supplement). For example, small cytosolic particles of irregular shape (unavoidable in cell extract) induce errors if they get trapped along with the cargo of interest (e.g. LD). When using VMatch, such particle could usually be excluded from the trap during the short time required for force measurement. This was not possible with other methods of trap calibration. In summary, we have developed a simple method to measure the force (and by extension the number and activity) of motors on single organelles in cell extract. This extends quantitative optical trapping beyond artificial motor-coated beads to real cellular cargoes.

ONLINE METHODS

Reagents

The Kif5B 914-930 amino acid peptide from rat “GHSAQIAKPIRPGQHP” was synthesized by BiotechDesk, India. Anti-ADRP mouse monoclonal antibody was purchased from Progen Biotechnik, Germany. Anti-KHC rabbit polyclonal antibody was a kind gift from Dr. Kristen Verhey (University of Michigan). S-200 Sephacryl HR beads were purchased from GE Bio-sciences. Protease Inhibitor Cocktail was purchased from Roche. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Animals

Sprague Dawley rats were bred and maintained by the animal house facility at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai. All animal protocols are approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) formulated by CPCSEA (Committee for the purpose of control and supervision of experiments on animals), India.

Instrumentation and data acquisition

The instrument and detection system has been described earlier16, and has been used by us to quantify motor function on Dictyostelium discoideum endosomes8. Motion was observed at 37°C in a custom developed DIC microscope (Nikon TE2000-U) using a 100x, 1.4 NA oil objective. The microscope is housed in an acoustically protected room on an optical table with active isolation (Newport). Image frames were acquired at video rate (30 frames/sec, no binning) with a Cohu 4910 camera. Each pixel measured 98nm × 98nm. Image frames were digitized and saved as .AVI files using an image acquisition card (National Instruments). No Image processing hardware or software was used for image enhancement The position of LDs and beads was tracked frame by frame using custom written software17 in Labview (National Instruments). The tracking algorithm calculates position of the centroid of a cross-correlation image with sub-pixel resolution17. Sub-pixel resolution was confirmed by moving a bead stuck on the coverslip in steps of 10 nm using a piezo stage (Physik Instrumente) and tracking its position (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The optical trap and detection setup is also shown schematically (Supplementary Fig. 1a). A single-mode diode laser at 980nm (Axcel photonics) was used after expansion to fill the back-focal place of the objective2-3. The laser power at sample plane was typically 50-70mW. We have earlier shown that there is no optical damage at these powers8,18-19. This was confirmed because LDs which stalled in the trap moved away with normal velocity after being released. The expected heating at sample plane is negligible (< 1 degC) at this power2-3. A quadrant photo diode (QPD) was used to obtain stall force records and thermal fluctuations2-3. For optical trapping with beads of uniform size, SQPD was obtained from the voltage pattern generated by a bead stuck to a coverslip and moved in known distance increments across the trap with a piezo stage2. For stall force records data was anti-alias filtered at 1KHz and digitized at 2KHz. For variance measurement, thermal fluctuations were recorded at 40 KHz. For power spectrum measurements, the power in thermal fluctuations was plotted as a function of frequency2. This curve was fitted to a Lorentzian function (e.g., see Supplementary Fig. 1) to obtain a corner frequency (Fc), and KTRAP was determined using (KTRAP = 12π2 η Fc · R). For in vitro assays using motor-coated beads, the uniform bead radius (R) and viscosity of medium (η) were known, and the same R was used for all beads in the assay2. The Lorentzian power spectrum of thermal fluctuations (Supplementary Fig. 1b) shows that the optical trap functions as a linear spring for beads and LDs. The range of QPD linearity for 500nm beads was estimated to be ±160nm (inset, Supplementary Fig 1b). This range extends further for larger objects (such as large LDs) because of the larger diameter. However, only stalls within ±160nm were used. The drag force method2-3 was used to determine that the optical trap was linear out to ±160nm from the trap centre for 500nm beads (further for larger beads/LDs).

Purification of Rat Liver Lipid Droplets for Motility

Lipid droplets are a convenient organelle for isolation at large scale by density gradient ultracentrifugation because of their low density. Detailed protocols for isolation of pure LDs from adipose tissue20 and liver21 are available, and several proteomic studies22 to identify the LD proteome have used these protocols. A brief description of the protocol used by us follows. Male Sprague Dawley rats of 2-4 months were anesthesized using sodium thiopentone. The liver was perfused with ice-cold PBS through the hepatic portal vein and dissected out. Liver was homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer in 1M MEPS buffer (35mM PIPES, 5mM EGTA, 5mM MgSO4, 1M sucrose, pH 7.2) with 2X protease inhibitor (PI) cocktail, 4mM PMSF, 2μg/ml of pepstatin A and 4mM DTT. The liver was homogenized in 1M MEPS buffer at a ratio of 1:1.5 weight/volume. The homogenate was spun at 1800xg, 4°C for 10 min to pellet the debris and obtain a post nuclear supernatant (PNS). 1x PI cocktail, 4mMDTT and 2μg/ml of pepstatin was added to the PNS before loading on a Sephacryl S-200 column (40ml bed volume) to separate organelles from cytosolic protein fraction. The first 4 ml of eluate was collected, supplemented with 1X PI cocktail, 4mM DTT and adjusted to 1.4M sucrose using 2.5M MEPS (2.5M indicates molarity of sucrose). This eluate was loaded at the bottom of a step gradient consisting of 2ml each of 1.4M, 1.2M and 0.5M MEPS. The gradient was spun in a SW41 Beckman rotor tube at 120000xg at 4°C for 1hr. The topmost 0.5M MEPS fraction contained LDs, and was collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen as 40ul aliquots to be used for motility. This gradient largely removes cellular particles (debris), though some small debris remains. We took care to reject stalls in which debris is visually observed in the trap. We checked this for every droplet before and after the trapping. Purified organelles were identified as LDs on the basis of their high buoyancy, refractile spherical appearance and abundance of ADRP23, a specific marker for LDs.

Motility assays

Tubulin (5-10mg/ml) was purified from goat brain as described8,16,24. Western blots using anti-MAP antibodies showed no detectable contamination from microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) after purification. Taxol stabilized microtubules were polymerized in BRB80 buffer containing 1mM GTP, 20μM Taxol for 45min at 37°C. For determining direction of LD motion, polarity labeled MTs were prepared using biotinylated seeds and magnetic avidin-coated beads as described16. Motility was observed in flow chambers of ~10μl volume prepared by sticking poly-L-Lysine coated coverslips to a microscope slide using two strips of double stick tape.

LD motility was observed using motility mix containing 38μl of LD fraction and 2μl of 20X ATP regenerating system (20mM ATP, 20mM MgCl2, 40mM creatine phosphate, and 40 U/ml creatine kinase). The final ATP concentration was 1mM. Motility mixture was introduced in a flow chamber containing MTs. Each slide was observed for 20 min or less. Extremely robust motion was observed; 75% of LDs (N = 160 tested from multiple rats) moved when placed on MTs using an optical trap. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first in vitro reconstitution of lipid droplet motility on MTs. We tested the possibility that motors are lost from the LDs, or are recruited non-specifically from the cytosol to LDs during the purification procedure. To do this, we incubated LDs in an ionic buffer and then recovered LDs by flotation. This treatment had no effect of the motility of LDs – the frequency and velocity of motion for treated LDs was statistically identical to untreated LDs. Thus, plus-directed motion appears to be driven by endogenously associated motors on LDs.

Conventional kinesin (kinesin-1) was purified from fresh goat brain through a nucleotide dependent microtubule affinity procedure25. No dynein or dynactin was detected in the purified sample as determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-dynein intermediate chain antibody and anti-p150 glued antibody. Kinesin-1 motility was assayed at single-molecule level as described elsewhere10 using beads of 500nm or 1 micron size.

Specificity of kinesin attachment to lipid droplets

We tested whether kinesin-1 is lost from LDs during purification, or spurious kinesin-1 gets attached non-specifically to LDs through electrostatic interactions when LDs come in contact with cytosol. This was done by treating LDs with an ionic buffer. If kinesin-1 is retained after such treatment, it is unlikely to be lost during purification (since this is a harsher treatment than the purification process). Further, this also tests whether the kinesin-1 driving motion is actually cytosolic contamination because contaminating kinesin-1 should be lost upon incubation in ionic buffer. This approach has been used earlier22 to remove contaminating proteins in proteomic analysis of LDs. LDs were incubated in 100mM sodium carbonate for 30 min on ice, separated by flotation and washed twice in motility buffer. Such LDs were then tested for motility, and no difference was found upon comparison with motility of untreated LDs.

Kinesin inhibition studies

For kinesin inhibition assays, LDs were incubated with the rat Kif5B 914-930 amino acid tail-domain peptide (KTD) for 15 min. Motility was observed at the end of the incubation with KTD present in the motility buffer. LDs were trapped and placed on MTs. The fraction of motile LDs was scored. A dose-dependent reduction in motility with KTD was seen (Supplementary Fig. 4). A similar construct is known26 to reduce the enzymatic activity of Drosophila melanogaster kinesin-1 without affecting its MT binding properties. We have separately verified that KTD blocks purified kinesin-1 driven in vitro motion of beads. The KTD peptide did not have any effect on the plus or minus directed motion of Dictyostelium discoideum endosomes8 which are driven by cytoplasmic dynein and a different kinesin (DdUnc104). Additional control experiments with non-specific peptide did not show any effect on LD or kinesin-1 bead motility.

Isolation of lipid droplets for immunodetection of kinesin and ADRP

For Western blotting, LDs are isolated as mentioned before with some modifications. Liver was lysed and PNS was prepared in 1M MEPS buffer (1M indicates sucrose molarity). PNS was adjusted to 1.4M sucrose-containing MEPS using 2.5M MEPS. Now, 7ml of 1.4M PNS was loaded at the bottom of sucrose step gradient containing 7ml each of 1.4M, 1.2M and 0.5M sucrose in MEPS (total volume 28ml). The topmost fraction of 0.5 M MEPS (~5ml) was collected and concentrated to 500μl for Western blotting. This fraction was enriched in lipid droplets, as confirmed by the detection of adipocyte differentiation related protein (ADRP), a specific marker for LDs in the liver23 by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 3) and also by immunofluorescence on individual LDs. To doubly validate the LD isolation procedure, a similar experiment using fat pads from rats was also done. Here we detected abundant perilipin (marker for adipose LDs12) in the top fraction. High speed supernatant (HSS) to detect cytosolic proteins in Western blots was prepared by spinning PNS for 30 min at 4deg C, 500000xg in a Beckman MLA 130 rotor. The pellet was discarded and supernatant (HSS) was collected.

Western Blotting

Total protein was stripped from purified LDs using a 2-D cleanup kit (ReadyPrep; Bio-Rad). Protein amount was quantified using a BCA kit (Sigma). For detection of ADRP, 25μg of total protein from LDs, 40μg of protein from endosome fraction and 50μg of protein from HSS were loaded in separate lanes and subjected to SDS-PAGE. For kinesin-1 detection 60μg of LD protein and 50μg of HSS protein was loaded. Protein was transferred to PVDF membrane, followed by blocking in 5% milk. Membranes were probed with ADRP and kinesin-1 antibodies at 1:1000 dilution for 1 hr. Secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit HRP conjugated antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used at 1: 20,000 dilution. The blots were developed using the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank A. Rai and R. Jha for discussions and help, and K. Verhey (University of Michigan) for kinesin-1 antibody. RM acknowledges funding through an International Senior Research Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust, UK (grant WT079214MA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Vale RD. Cell. 2003;112:467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman KC, Block SM. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75(9):2787. doi: 10.1063/1.1785844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice SE, Purcell TJ, Spudich JA. Methods Enzymol. 2003;361:112. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)61008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welte MA, Gross SP, Postner M, et al. Cell. 1998;92:547. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shubeita GT, Tran SL, Xu J, et al. Cell. 2008;135(6):1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sims PA, Xie XS. Chemphyschem. 2009;10(9-10):1511. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leidel C, Longoria RA, Gutierrez FM, et al. Biophys J. 2012;103(3):492. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soppina V, Rai AK, Ramaiya AJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(46):19381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers SL, Tint IS, Fanapour PC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(8):3720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vershinin M, Carter BC, Razafsky DS, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(1):87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons GF, Wiggins D, Brown AM, et al. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(Pt 1):59. doi: 10.1042/bst0320059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welte MA. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 5):991. doi: 10.1042/BST0370991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Sasabe N, Ohshima K, et al. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(9):2571. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M004648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeulen Karen C., van Mameren Joost, Stienen Ger J., et al. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006;77:13704. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolic-Nørrelykke Simon F., Schäffer Erik, Howard Jonathon, et al. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006;103101:77. [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES IN ONLINE METHODS

- 16.Soppina V, Rai Arpan., Mallik R. Biotechniques. 2009;46:297. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter BC, Shubeita GT, Gross SP. Physical Biology. 2005;2:60. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/2/1/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallik R, Carter BC, Lex SA, et al. Nature. 2004;427:649. doi: 10.1038/nature02293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallik R, Petrov D, Lex SA, et al. Current Biology. 2005;15:2075. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brasaemle DL, Wolins NE. Chapter 3. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006:15. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0315s29. Unit 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ontko JA, Perrin LW, Horne LS. J Lipid Res. 1986;27(10):1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brasaemle DL, Dolios G, Shapiro L, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Wei E, Quiroga AD, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(12):1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castoldi M, Popov AV. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;32(1):83. doi: 10.1016/S1046-5928(03)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroer TA, Sheetz MP. J Cell Biol. 1991;115(5):1309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaan HY, Hackney DD, Kozielski F. Science. 2011;333(6044):883. doi: 10.1126/science.1204824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.