Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease most notably characterized by the misfolding of amyloid-β (Aβ) into fibrils and its accumulation into plaques. In this Article, we utilize the affinity of Aβ fibrils to bind metal cations and subsequently imprint their chirality to bound molecules to develop novel imaging compounds for staining Aβ aggregates. Here, we investigate the cationic dye ruthenium red (ammoniated ruthenium oxychloride) that binds calcium-binding proteins, as a labeling agent for Aβ deposits. Ruthenium red stained amyloid plaques red under light microscopy, and exhibited birefringence under crossed polarizers when bound to Aβ plaques in brain tissue sections from the Tg2576 mouse model of AD. Staining of Aβ plaques was confirmed via staining of the same sections with the fluorescent amyloid binding dye Thioflavin S. In addition, it was confirmed that divalent cations such as calcium displace ruthenium red, consistent with a mechanism of binding by electrostatic interaction. We further characterized the interaction of ruthenium red with synthetic Aβ fibrils using independent biophysical techniques. Ruthenium red exhibited birefringence and induced circular dichroic bands at 540 nm upon binding to Aβ fibrils due to induced chirality. Thus, the chirality and cation binding properties of Aβ aggregates could be capitalized for the development of novel amyloid labeling methods, adding to the arsenal of AD imaging techniques and diagnostic tools.

Keywords: Circular dichroism, birefringence, amyloid β, ruthenium red, plaques, Thioflavin S, histochemistry

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by the pathological accumulation of misfolded amyloid proteins, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) in extracellular amyloid plaques, and hyperphosphorylated tau as intracellular neurofibrillary tangles. The transition of monomeric Aβ to misfolded, fibrillar Aβ plays an important role in the pathology of AD.1 New technologies now allow the identification of such misfolded proteins in plaques, and more recently plaques and tangles, by using imaging/labeling compounds.2,3 The identification of additional and novel compounds that would allow facile staining of amyloid plaques will only advance these technologies. In this paper, we take advantage of two features of Aβ fibrils and plaques to develop novel imaging compounds: (i) their affinity for cationic species and (ii) their ability to imprint their chirality to bound compounds.

Amyloid binding compounds contain certain general features, which include planar aromatic and hydrophobic systems, cationic charge, and some conformational freedom to fit into the binding site of the Aβ fibril.4−11 Binding of these molecules to Aβ aggregates freezes their structure and changes their microenvironment, producing a change in their properties (e.g., fluorescence intensity, color, and polarization among others) that can be utilized for staining. Of the many aforementioned properties, cationic character is of great interest to us, since Aβ fibrils and plaques readily bind cationic dyes and metal ions. For example, several cationic dyes such as rosaline dyes (crystal violet and methyl violet), alcian blue, Thioflavin T, and thiazine red have demonstrated high affinity to amyloid plaques6,12,13 as wells as cations such as calcium, iron, and copper.14 Additionally, Aβ aggregates can also bind metal complexes such as the dye cuprolinic blue15 and, as we have previously demonstrated, ruthenium(II) dipyridophenazine complexes.16 Thus, binding of cationic compounds and metal complexes to Aβ plaques represent an exploitable research avenue.

Also of interest are the changes in the photophysical properties of molecular probes when bound to Aβ fibrils. Upon binding to Aβ fibrils, many molecules suffer restriction in their conformational or rotational freedom. This concept is of great importance in the design of Aβ aggregate binding agents.8 For example, the restriction of rotational freedom is the main reason for the light switching properties of Thioflavin T, one of the most used dyes for fluorescent labeling of Aβ deposits.4,5,8−11 In addition to fluorescence, binding of certain compounds to amyloid fibrils could result in birefringence. Birefringence occurs when the chirality of the Aβ fibrils is imprinted into the bound achiral dye, with a consequential change in the optical rotatory dispersion of the dye, which is termed the Cotton effect.17 Birefringence of the dye Congo red upon binding to Aβ fibrils and plaques is well-known,17 and combined to its strong amyloid affinity makes it a useful histological tool.12 This induced chirality can also be observed by circular dichroism, with the appearance of circular dichroic bands near the visible spectrum absorption maxima. Thus, both cationic binding and conformational restriction leading to chirality transfer can translate to novel amyloid binding and imaging tools.

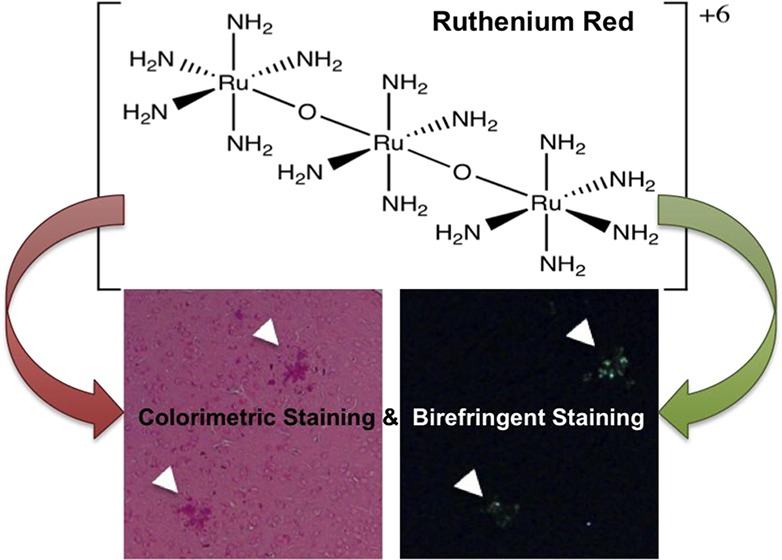

We aimed to determine if nonchiral cationic metal complexes would bind to amyloid plaques and exhibit such birefringence. Ruthenium red, a cationic complex of ammoniated ruthenium oxychloride, was selected, as it has been used to stain calcium-binding proteins in Western blots18,19 and as a contrast agent to visualize amyloid plaques by electron microscopy.13,15 This paper presents the first demonstration of ruthenium red colorimetric and birefringent staining of amyloid plaques. We demonstrated that ruthenium red histochemically labels plaques within the brains of the Tg2576 mouse model of AD. Furthermore, we showed that ruthenium red exhibits birefringence under a cross-polarizer microscope when bound to Aβ fibrils in vitro and murine amyloid plaques. This is of special interest, due to the wide usage of ruthenium red for labeling and staining, which will provide a facile, rapid, and inexpensive staining method of Aβ aggregates. Furthermore, its red color is an additional advantage for tissue examination. The novelty of this research resides in using ruthenium red as a colorimetric and birefringent staining agent for Aβ aggregates, which to our best knowledge are unexplored uses for ruthenium red. Furthermore, we expect that scientists commonly using this staining will become aware that amyloid aggregates could also be stained by ruthenium red, especially in tissues from organs subject to amyloidogenic depositions such as heart, liver, and pancreas.

Results and Discussion

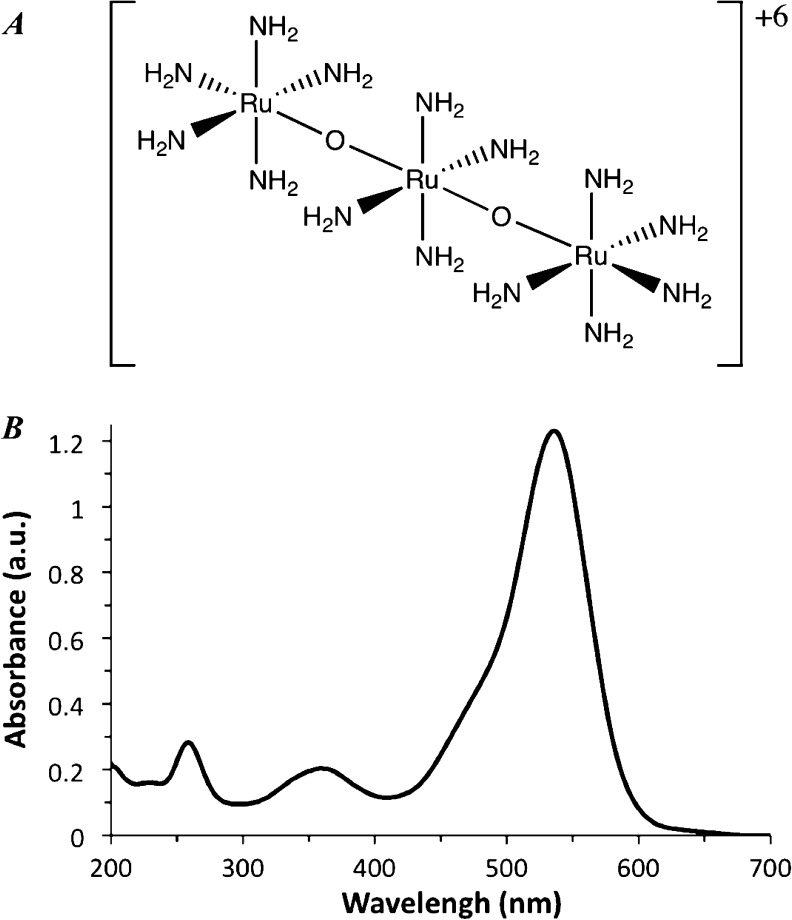

Ruthenium red is a triad of ruthenium cations joined by oxygen atoms in a nearly linear conformation (Figure 1A). The ruthenium atoms are octahedrally coordinated, with amine groups occupying positions not coordinated by the bridging oxygens. In the X-ray structure, two ruthenium octahedra are eclipsed and the third is rotated by 33°.20 Raman experiments support a similar structure in solution, although it is likely that when dissolved the amine group adopts a more staggered conformation. Nonetheless, for practical purposes, ruthenium red can be considered as a hexacationic molecular cylinder. The intense red color of ruthenium red comes from its visible absorption spectrum with a strong band centered at ca. 540 nm, and results in the transmission of red light (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Ruthenium red structure and absorption spectrum. (A) Ruthenium red schematic representation showing atom connectivity. (B) UV–vis spectrum of ruthenium red in aqueous solution.

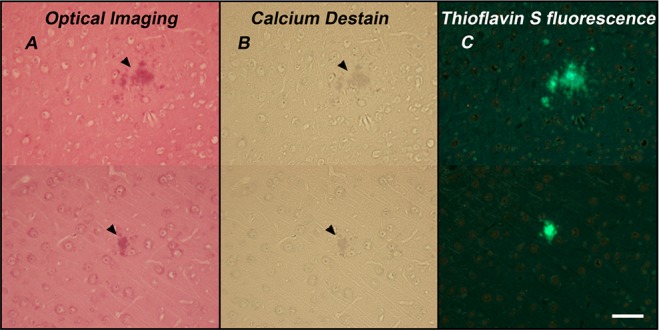

Our studies demonstrate that ruthenium red reversibly stains Aβ plaques in brain sections from the Tg2576 Alzheimer’s disease mouse model (Figure 2). Ruthenium red staining of amyloid plaques was verified with Thioflavin S (ThioS) fluorescent staining of the same plaques (Figure 2C). Neurons in the dentate cellular layer of the hippocampus and the Purkinje layer of the cerebellum were also stained (data not shown). Addition of a 250 mM calcium chloride solution to the tissue readily removes ruthenium red, as indicated by the loss of the red coloration (Figure 2B). The displacement of ruthenium red from its binding site in the Aβ plaques by the calcium cations is consistent with binding by electrostatic interactions.

Figure 2.

Optical microscopy of ruthenium red stained brain tissues. (A) Optical image of 13 month old Tg2576 mice (n = 1) tissue section stained with ruthenium red. Arrowheads point to stained amyloid plaques. (B) Destaining of ruthenium red by Ca2+ (250 mM solution). (C) ThioS stained amyloid plaques in the same tissue sections. All images were from the somatosensory cortex. The magnification is 20×, and scale bar is 50 μm. Representative images from n = 5 Tg2576 mice stained.

The binding of ruthenium red to Aβ plaques can be rationalized in terms of electrostatic and hydrogen bonding between the tetra- and penta-amine groups of ruthenium red to negatively charged groups, such as carboxylic acids, on the Aβ peptides.21 Furthermore, the pH of the buffer (7.4) is above the isoelectric point of the Aβ peptide (∼5.5), and thus, at the physiological pH of 7.4, the plaques are negatively charged and prone to react with ruthenium red. Since ruthenium red could also bind to imidazole nitrogens on histidine amino acids,22 these residues in Aβ may also be involved in binding ruthenium red. Other potential binding agents in the Aβ plaques could involve species such as calcium binding proteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans, which have already reported to bind ruthenium red.13,18,19,23−28 A chemical method for desulfation of proteoglycans29 did not alter ruthenium binding to plaques (data not shown). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of in vitro produced Aβ fibrils (not containing proteoglycans) show good contrast when stained with ruthenium red, indicating good binding of ruthenium red to the aggregates (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Further experiments are needed to unambiguously determine the binding sites of ruthenium red to Aβ fibrils and plaques; however, this will likely be related to negatively charged amino acids at physiological pH such as Glu and Asp.

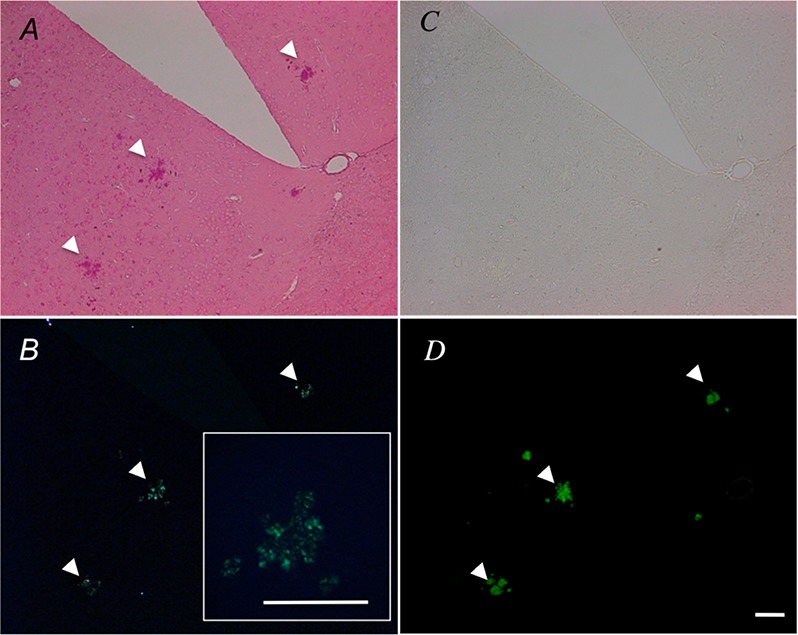

We next aimed to identify if the chirality of the Aβ fibrils could be transferred to bound ruthenium red, exhibiting birefringence. Ruthenium red stained plaques (red) in the bright field image (Figure 3A) and these same stained structures exhibited green birefringence under cross-polarization (Figure 3B). To the best of our knowledge, green birefringence from amyloid plaques stained with ruthenium red has not been reported to date. Fluorescence of the amyloid binding dye ThioS (Figure 3D) correlated with the same ruthenium red birefringent structures (Figure 3B). This confirms that the birefringence of ruthenium red is due to its interaction with amyloid plaques. Additionally, when the brain sections were imaged using cross-polarizers, green birefringence was only observed from ruthenium red stained amyloid plaques and not from the surrounding peripheral tissue or neurons stained with ruthenium red (Figure 3B vs A). Unstained Aβ plaque-containing tissue shows no birefringence under cross-polarized light (data not shown), again confirming that the observed birefringence arises due to the interaction of ruthenium red with Aβ plaques. Moreover, it is important to consider that ruthenium 360, a different ammoniated ruthenium compound, is a common impurity found in ruthenium red. To verify the role of ruthenium 360 in the staining and birefringence observed in tissue sections, some murine brain sections were stained specifically with this dye. Cross-polarized microscopy images of brain tissue stained with ruthenium 360 are completely black, while those stained with ruthenium red showed the expected green birefringence (Supporting Information, Figure S2). This also confirms that ruthenium red is responsible for the red staining and the green birefringence of Aβ plaques in tissue.

Figure 3.

Polarized optical microscopy of tissue sections stained with ruthenium red. Representative (A) bright field and (B) crossed polarized microscope images of ruthenium red stained 13 month old Tg2576 brain tissues with 10× magnification. (inset: 20× magnification of central plaque). (C) Bright field and (D) fluorescence microcopy image of ThioS amyloid plaques stained in successive brain sections. Arrows show positively identified plaques. The scale bar represents 100 μm. All images were from the anterior olfactory nucleus.

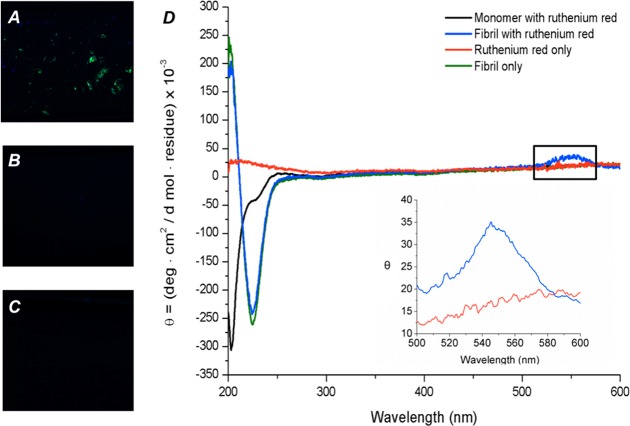

To demonstrate that this birefringence was specific to Aβ aggregates, and not from other protein components within amyloid plaques, we performed in vitro experiments on synthetic Aβ fibrils. Synthetic Aβ fibrils were grown in vitro, stained with ruthenium red, and then visualized under cross-polarization, showing green birefringence (Figure 4A). Monomeric Aβ and ruthenium red by themselves show no birefringence as observed in Figure 4B, C. Birefringence suggests that the achiral ruthenium red gain some chirality due to the interaction with the fibrils, and therefore we used circular dichroism to demonstrate such dichroism. An induced circular dichroic band at 550 nm was observed by circular dichroism when ruthenium red was bound to Aβ aggregates (Figure 4D). This band is consistent with the UV–vis spectrum of ruthenium red in the same region (Figure 1). The circular dichroism spectra of ruthenium red, Aβ monomer, and Aβ aggregates alone show no peak at 550 nm, which confirms that this peak arises due to the interaction of these two species. The fact that the induced dichroic band at 550 nm is not present in the circular dichroism spectrum of ruthenium red alone in buffer solution can be explained due to the lack of chirality of ruthenium red. Of note, Aβ fibrils demonstrate β-sheet structure via circular dichroism, with a maximum at ca. 200 and a minimum at 218 nm, while the monomeric Aβ demonstrates a random coil structure with a minimum at 200 nm via circular dichroism. The appearance of the 550 nm induced dichroic band together with the spectral features consistent with β-sheet structure is a validation of the ruthenium red binding to β sheet structures of amyloid.

Figure 4.

Birefringence and circular dichroism of in vitro prepared Aβ fibrils stained with ruthenium red. Cross-polarized microscope images of (A) in vitro grown Aβ fibrils, (B) monomeric Aβ in the presence of ruthenium red (10× magnification), and (C) ruthenium red in the absence of Aβ peptide. (D) Circular dichroism spectrum of in vitro grown Aβ fibril (green line), in vitro grown Aβ with ruthenium red (blue line), prefibrillar monomeric Aβ with ruthenium red (black line), and ruthenium red in buffer solution (red line). Inset: Circular dichroism spectral region from 500 to 600 nm obtained with additional acquisitions and with in-program line smoothing.

This birefringence and induced dichroic shift can be explained by induced chirality on ruthenium red when bound to Aβ fibrils. The left-handed twist of β-sheets within Aβ fibrillar structures results in an overall and intrinsic left-handed chirality.30 Consequently, Aβ plaques are composed in great part of Aβ fibrils with intrinsic chirality, which thus gets imprinted in the nonchiral ruthenium red molecules. This induced dichroism, also termed the Cotton effect,17 has been observed when ruthenium red binds to the ordered structure of DNA.31

Transition metal complexes present an interesting and relatively unexplored alternative for new amyloid-binding molecules with potential application to Aβ aggregates labeling and inhibition. The advantages of metal complexes include formation of stable complexes, the tuning of ligand affinities, and good photostability, among others.22 One caveat of the use of ruthenium red in living systems is that it alters calcium uptake via several mechanisms,32−34 and at high concentrations can cause seizures and paralysis.35 However, it has been used in vivo for imaging cancer cells, and for cancer and ischemia therapy.22,36−39

In conclusion, we clearly demonstrate ruthenium red binding and birefringence upon binding to amyloid plaques via ionic interaction with birefringence due to induced chirality. Such staining is important as it introduces novel, inorganic, metal–ligand chemistry into the field of Alzheimer’s disease brain imaging.

Methods

Materials

Thioflavin S (ThioS) was obtained from VWR, ruthenium red (ammoniated ruthenium oxychloride) from Sigma, and ruthenium 360 from EMD Millipore. Vectashield without DAPI was purchased from Vector Laboratories. All water used in experiments was purified to 18 MΩ using an ion exchanger and reverse osmosis unit (Purlab Ultra, Elga, Lowell, MA).

Transgenic Mice

Mouse brain tissues from 13 month old Tg2576 (n = 10) and control (n = 6) mice were obtained from Dr. Kelly T. Dineley. All animal procedures and protocols were in accordance to University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) animal use protocols and IACUC approval. The animal colony was maintained as described previously.40 Mice were euthanized with ketamine (10 mg/mL)/xylazine (1.5 mg/mL) and transcardially perfused with PBS, pH 7.4, followed by 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde fixative in PBS, pH 7.4. Whole brains were removed, postfixed overnight at 4 °C, sucrose protected, and stored at −80 °C. The brains were then postfixed again in 4% paraformaldehyde/saline overnight prior to paraffin embedding. The brains were sectioned sagittally at 5 μm by the Texas A&M Histology Core and used for the following experiments.

Histochemistry

Slides were deparaffinized by twice immersion in xylenes for 5 min each, followed by rehydration through decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95%, 80%, and 70%) for 1 min each and ending in water.

Ruthenium red staining

Ruthenium red (0.05% w/v) was prepared by dissolving 0.025 g into 50 mL of PBS (100 mM, pH 7.4),18 with brief sonication. Rehydrated slides were immersed in this ruthenium red solution for 10 min, washed in 100 mM PBS for 5 min, coverslipped with Vectashield (without DAPI), and imaged using light microscopy.

Ruthenium Red Destaining

Ruthenium red was destained with a CaCl2 solution (250 mM or higher) for 20 min and washed in 100 mM PBS for 5 min. For subsequent staining with ThioS, the Ca2+ was removed by immersion in 250 mM EDTA for 10 min and then rinsed in ddH2O for 3 min.

Thioflavin S (ThioS) Staining

ThioS staining was performed as previously described.41 The ThioS solution (0.0125%) was prepared by dissolving 0.0125 g of ThioS in 100 mL of 40:60% PBS/ethanol. Slides were stained with this ThioS solution and resolved in 50% PBS/ethanol for 3 min each. The slides were washed twice in 100 mM PBS for 15 min each, then in ddH2O, coverslipped in Vectashield (without DAPI), and viewed using fluorescence microscopy.

Ruthenium 360 Staining

Ruthenium 360 was prepared by dissolving 1 mg of the material into 1 mL of ddH2O. Rehydrated slides were immersed in ruthenium 360 diluted to 0.5 mg/mL for 10 min, washed in ddH2O for 5 min, and coverslipped with Vectashield (without DAPI).

Ruthenium Red Birefringence of Murine Plaques and Fibrillar Aβ

Slides were stained with ruthenium red as described above. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with polarizers, under crossed polarization. Ruthenium 360 stained brain sections on slides were imaged in a similar fashion.

For images of in vitro grown Aβ fibrils, 100 μM samples were prepared in PBS buffer. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C and with orbital shaking at 900 rpm in an Eppendorf Thermoshaker, samples were centrifuged at 16 000g for 30 min. The excess supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in a minimal amount of buffer. For samples with ruthenium red, a minimal volume of concentrated ruthenium red stock solution was added to the suspension to obtain a final concentration of 0.05% (w/v). Rectangular capillary tubes (Vitrotubes) were used to hold the samples for imaging.

Ruthenium Red Induced Circular Dichroism with Aβ Fibrils

Circular dichroism spectra were obtained using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter with 0.4 cm quartz cuvettes containing pH 7.4 PBS (100 mM phosphate, 300 mM NaCl), Aβ (100 μm), and ruthenium red (0.05% w/v). The molar residual ellipticity was calculated from the measured ellipticity using the following equation:

where θ is the measured ellipticity in mdeg, m is the molar mass of the peptide in g/mol, c is the concentration of the peptide in mg/mL, l is the path length of the cuvette in cm, and nr is the number of residues.42 Aβ fibrils were incubated as reported above.16

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Two microliters of Aβ sample (100 μM) was deposited on a glow discharged copper grid (Ted Pella 01811) and allowed to adsorb for 1 min. The sample was then wicked dry and washed with 50 μL of water. Then 3 μL of a 0.025% solution of ruthenium red was applied to the grid, and the staining was allowed to proceed for 1 min until the sample was wicked dry. The samples were then imaged on a JEOL 1230 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Rachel Petrofes Chapa for some of the ruthenium red staining experiments and critical reading of the manuscript. We also wish to thank Marci Kang and Lesley O’Leary for assistance with circular dichroism measurements.

Supporting Information Available

Additional TEM and cross-polarized microscopy images as described in the text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors acknowledge the Texas A&M Health Science Center, Department of Neuroscience and Experimental Therapeutics startup funds (I.V.J.M.) and the Welch Foundation grant C-1743 (A.A.M.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Contributions

⊥ These authors contributed equally.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hardy J.; Selkoe D. J. (2002) The Amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Saji H. (2012) Molecular approaches to the treatment, prophylaxis, and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease:Novel PET/SPECT imaging probes for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 118, 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. R.; Cisek K.; Funk K. E.; Naphade S.; Schafer K. N.; Kuret J. (2011) Research towards tau imaging. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 26, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterov E. E.; Skoch J.; Hyman B. T.; Klunk W. E.; Bacskai B. J.; Swager T. M. (2005) In vivo optical imaging of amyloid aggregates in brain: Design of fluorescent markers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 44, 5452–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond S.; Skoch J.; Hills I.; Nesterov E.; Swager T.; Bacskai B. (2008) Smart optical probes for near-infrared fluorescence imaging of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 35, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchtler H.; Waldrop F. S.; Meloan S. N. (1983) Application of thiazole dyes to amyloid under conditions of direct cotton dyeing: Correlation of histochemical and chemical data. Histochem. Cell Biol. 77, 431–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek K.; Kuret J. (2012) QSAR studies for prediction of cross-β sheet aggregate binding affinity and selectivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 1434–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutharsan J.; Dakanali M.; Capule C.; Haidekker M.; Yang J.; Theodorakis E. (2010) Rational design of amyloid binding agents based on the molecular rotor motif. ChemMedChem 5, 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulatskaya A. I.; Maskevich A. A.; Kuznetsova I. M.; Uversky V. N.; Turoverov K. K. (2010) Fluorescence quantum yield of thioflavin T in rigid isotropic solution and incorporated into the amyloid fibrils. PLoS One 5, e15385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voropai E. S.; Samtsov M. P.; Kaplevskii K. N.; Maskevich A. A.; Stepuro V. I.; Povarova O. I.; Kuznetsova I. M.; Turoverov K. K.; Fink A. L.; Uverskii V. N. (2003) Spectral Properties of Thioflavin T and Its Complexes with Amyloid Fibrils. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 70, 868–874. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs M. R. H.; Bromley E. H. C.; Donald A. M. (2005) The binding of thioflavin-T to amyloid fibrils: localisation and implications. J. Struct. Biol. 149, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark G. T.; Johnson K. H.; Westermark P. (1999) Staining methods for identification of amyloid in tissue. Methods Enzymol. 309, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young I. D.; Willmer J. P.; Kisilevsky R. (1989) The ultrastructural localization of sulfated proteoglycans is identical in the amyloids of Alzheimer’s disease and AA, AL, senile cardiac and medullary carcinoma-associated amyloidosis. Acta Neuropathol. 78, 202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell M. A.; Robertson J. D.; Teesdale W. J.; Campbell J. L.; Markesbery W. R. (1998) Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 158, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow A. D.; Lara S.; Nochlin D.; Wight T. N. (1989) Cationic dyes reveal proteoglycans structurally integrated within the characteristic lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 78, 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N. P.; Torres V.; Jain D.; Martí A. A. (2011) Sensing amyloid-β aggregation using luminescent dipyridophenazine Ruthenium(II) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11121–11123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benditt E. P.; Eriksen N.; Berglund C. (1970) Congo red dichroism with dispersed amyloid fibrils, an extrinsic cotton effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 66, 1044–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienaert I.; De S. H.; Parys J. B.; Missiaen L.; Vanlingen S.; Sipma H.; Casteels R. (1996) Characterization of a cytosolic and a luminal Ca2+ binding site in the type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27005–27012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima A.; Osman B. A. H.; Takashima M.; Kikuchi A.; Kohchi S.; Satoh E.; Tamba M.; Matsuda M.; Okamura N. (2009) CABS1 is a novel calcium-binding protein specifically expressed in elongate spermatids of mice. Biol. Reprod. 80, 1293–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de C.T. Carrondo M. A. A. F.; Griffith W. P.; Hall J. P.; Skapski A. C. (1980) X-ray structure of [Ru3 O2 (NH3)14]6+, cation of the cytological reagent ruthenium red. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 627, 332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling C. (1970) Crystal-structure of ruthenium red and stereochemistry of its pectin stain. Am. J. Bot. 57, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M. J. (2003) Ruthenium metallopharmaceuticals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 236, 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- El-Saggan A. H.; Uhrik B. (2002) Improved staining of negative binding sites with ruthenium red on cryosections of frozen cells. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 21, 457–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunoff D. (1972) Vital staining of mast cells with ruthenium red. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 20, 938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi A.; Marcellini M.; Spagnoli L. G. (2000) Aging influences development and progression of early aortic atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 20, 1123–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabba R. P.; Lulai E. C. (2002) Histological analysis of the maturation of native and wound periderm in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber. Ann. Bot. 90, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis E. R.; Wang Y. M.; Michael D. J.; Caron M. G.; Wightman R. M. (2000) Differential quantal release of histamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine from mast cells of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will T.; Tjallingii W. F.; Thönnessen A.; van Bel A. J. E. (2007) Molecular sabotage of plant defense by aphid saliva. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10536–10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry G.; Siedlak S. L.; Richey P.; Kawai M.; Cras P.; Kalaria R. N.; Galloway P. G.; Scardina J. M.; Cordell B.; Greenberg B. D. (1991) Association of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 11, 3679–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fändrich M. (2007) On the structural definition of amyloid fibrils and other polypeptide aggregates. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpel R. L.; Shirley M. S.; Holt S. R. (1981) Interaction of the ruthenium red cation with nucleic acid double helices. Biophys. Chem. 13, 151–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S. Y.; Beutner G.; Kinnally K. W.; Dirksen R. T.; Sheu S. S. (2011) Single Channel Characterization of the Mitochondrial Ryanodine Receptor in Heart Mitoplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21324–21329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L.; De Smedt H.; Droogmans G.; Wuytack F.; Raeymaekers L.; Casteels R. (1990) Ruthenium red and compound 48/80 inhibit the smooth-muscle plasma-membrane Ca2+ pump via interaction with associated polyphosphoinositides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1023, 449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S.; Ryu S. Y.; Sheu S. S. (2011) Distinctive characteristics and functions of multiple mitochondrial Ca2+ influx mechanisms. Sci. China Life Sci. 54, 763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia R. (1985) Effects of drugs on neurotransmitter release: Experiments in vivo and in vitro. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 9, 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Rivas G.; Carvajal K.; Correa F.; Zazueta C. (2006) Ru360, a specific mitochondrial calcium uptake inhibitor, improves cardiac post-ischaemic functional recovery in rats in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 149, 829–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carry M. M.; Mrak R. E.; Murphy M. L.; Peng C. F.; Straub K. D.; Fody E. P. (1989) Reperfusion injury in ischemic myocardium: protective effects of ruthenium red and of nitroprusside. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2, 335–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo V. M.; Dresdner K. P.; Wolney A. C.; Keller A. M. (1991) Postischaemic reperfusion injury in the isolated rat heart: effect of ruthenium red. Cardiol. Res. 25, 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R.; Lisa F. d.; Raddino R.; Visioli O. (1982) The effects of ruthenium red on mitochondrial function during post-ischaemic reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 14, 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rivera J.; Denner L.; Dineley K. T. (2011) Rosiglitazone reversal of Tg2576 cognitive deficits is independent of peripheral gluco-regulatory status. Behav. Brain Res. 216, 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovronsky D. M.; Zhang B.; Kung M. P.; Kung H. F.; Trojanowski J. Q.; Lee V. M. Y. (2000) In vivo detection of amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7609–7614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary L. E. R.; Fallas J. A.; Hartgerink J. D. (2011) Positive and negative design leads to compositional control in AAB collagen heterotrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5432–5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.