Abstract

Background and Purpose

Overactive bladder (OAB) is often associated with abnormally increased detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) contractions. We used NS309, a selective and potent opener of the small or intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK or IK, respectively) channels, to evaluate how SK/IK channel activation modulates DSM function.

Experimental Approach

We employed single-cell RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, whole cell patch-clamp in freshly isolated rat DSM cells and isometric tension recordings of isolated DSM strips to explore how the pharmacological activation of SK/IK channels with NS309 modulates DSM function.

Key Results

We detected SK3 but not SK1, SK2 or IK channels expression at both mRNA and protein levels by RT-PCR and immunocytochemistry in DSM single cells. NS309 (10 μM) significantly increased the whole cell SK currents and hyperpolarized DSM cell resting membrane potential. The NS309 hyperpolarizing effect was blocked by apamin, a selective SK channel inhibitor. NS309 inhibited the spontaneous phasic contraction amplitude, force, frequency, duration and tone of isolated DSM strips in a concentration-dependent manner. The inhibitory effect of NS309 on spontaneous phasic contractions was blocked by apamin but not by TRAM-34, indicating no functional role of the IK channels in rat DSM. NS309 also significantly inhibited the pharmacologically and electrical field stimulation-induced DSM contractions.

Conclusions and Implications

Our data reveal that SK3 channel is the main SK/IK subtype in rat DSM. Pharmacological activation of SK3 channels with NS309 decreases rat DSM cell excitability and contractility, suggesting that SK3 channels might be potential therapeutic targets to control OAB associated with detrusor overactivity.

Keywords: Patch-clamp, contractility, apamin, single-cell RT-PCR

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB), which is often associated with involuntary contractions of detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) during the bladder filling phase, is a serious medical problem impairing human quality of life (Andersson and Wein, 2004; Wein and Rackley, 2006). Antimuscarinics, the present mainstay of OAB therapeutics, are only moderately effective and induce many adverse effects, including dry mouth, constipation and blurred vision (Andersson and Wein, 2004; Epstein et al., 2006). Therefore, there is a considerable need for alternative therapeutics for the treatment of OAB and associated detrusor overactivity (DO). We propose that activation of DSM small or intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK or IK, respectively) channels with selective openers could be a potential pharmacological approach to control DO.

During normal bladder function, DSM exhibits spontaneous phasic contractions driven by spontaneous action potentials (Heppner et al., 1997; Petkov et al., 2001a; Hashitani and Brading, 2003b; Herrera et al., 2003; Hristov et al., 2008; Hristov et al., 2011; Petkov, 2012). In DSM, Ca2+-activated K+ channels play a significant role in the maintenance of the resting membrane potential (RMP), the repolarization and after-hyperpolarization phases of the action potential (Heppner et al., 1997; Hristov et al., 2011; 2012; Petkov, 2012). Three subtypes of SK channels, namely SK1 (KCa2.1; KCNN1), SK2 (KCa2.2; KCNN2) and SK3 (KCa2.3; KCNN3), have been cloned in mammals (Kohler et al., 1996). IK (SK4; KCa3.1; KCNN4) channel, which was originally termed the Gardos channel, is another member of this group (Gardos, 1958). SK and IK channels are insensitive to the changes in the membrane potential and are exclusively activated by rises in the intracellular Ca2+. These channels are not inactivated at negative membrane potentials and can evoke a robust hyperpolarization response (Grgic et al., 2009). Despite their small conductance of 4–14 pS, SK channels are powerful modulators of electrical excitability and exhibit substantial physiological effects in various cell types (Wulff and Zhorov, 2008).

Using pharmacological approaches and genetically manipulated animal models, a significant contribution of the SK channels in controlling DSM function has been demonstrated (Herrera and Nelson, 2002; Herrera et al., 2003; Thorneloe et al., 2008). Although IK channel expression is reported in DSM of guinea pigs (Parajuli et al., 2012) and mice (Ohya et al., 2000), its functional role in regulating DSM excitability and contractility has remained largely unexplored. Previous findings showed that pharmacological inhibition of SK channels with apamin increased the amplitude and duration of spontaneous phasic contractions in animals and human DSM (Herrera et al., 2000; Imai et al., 2001; Buckner et al., 2002; Herrera and Nelson, 2002; Hashitani and Brading, 2003a,b; Hashitani et al., 2004; Darblade et al., 2006; Afeli et al., 2012b). On the other hand, overexpression of SK3 channels in murine DSM increased the whole cell currents and bladder capacity (Herrera et al., 2003). A loss of apamin sensitivity to DSM contractility was observed in SK2 channel knockout mice, indicating a contribution of the SK2 channel to the DSM function (Thorneloe et al., 2008). SK channels contribution in decreasing rat DSM contractility was also suggested in a bladder outlet obstruction-induced model of DO (Kita et al., 2010).

Here, we tested the hypothesis that pharmacological activation of SK/IK channels reduces rat DSM excitability and contractility. For this purpose, we used NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2, 3-dione 3-oxime), a selective and potent SK/IK channel opener (Strobaek et al., 2004). NS309 activates SK/IK channels by increasing their Ca2+ sensitivity (Strobaek et al., 2006). In conscious rats, i.v. application of NS309 reduced the DSM contractility and decreased the voiding frequency (Pandita et al., 2006), but the contribution of SK/IK channels to rat DSM function remains unclear. Recently, we demonstrated that SK channel pharmacological activation with SKA-31, another SK/IK channel opener (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2009), decreased guinea pig DSM excitability and contractility (Parajuli et al., 2012). Similarly, SK/IK channel activation with NS4591, another SK/IK channel activator, inhibited the carbachol and electrical field stimulation (EFS)-induced DSM contractions in rats, pigs and humans (Nielsen et al., 2011) and reduced bladder overactivity in rats (Hougaard et al., 2009). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports available for the effects of NS309 on rat DSM RMP and myogenic contractions. The study of the SK and IK channels roles in rat DSM function is important because the rat is a widely used experimental animal model.

The aim of this study was to explore if pharmacological activation of SK and IK channels with NS309, a selective and potent activator of SK and IK channels, can decrease DSM excitability and contractility. For this purpose, we used pharmacological approaches, molecular biology, electrophysiology and myography. Here, we demonstrate the expression of mRNA message for SK3 channels in rat DSM at a single-cell level, and that the pharmacological activation of this channel with NS309 decreases rat DSM cell excitability and contractility. Thus, our data reveal that DSM SK3 channels could be a promising therapeutic target to control impaired bladder function.

Methods

DSM strips preparation

In this study, we used 61 (53 males and 8 females) Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories Inc., Frederick, MD, USA) of average weight 342.4 ± 8.3 g. Rats were killed with CO2 inhalation following the procedures of the animal use protocol (#1747) reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of South Carolina. The urinary bladders were quickly removed and stored in dissection solution. Urinary bladders were cut open longitudinally from the lumen; and the urothelium, including lamina propria, was carefully removed; 5–7 mm long and 2–3 mm wide DSM strips were isolated for single cell preparation and isometric DSM tension recordings.

DSM single cell isolation

Rat DSM single cells were freshly isolated as described previously (Hristov et al., 2008; Chen and Petkov, 2009). Briefly, one to two small DSM strips were incubated in pre-warmed 2 mL dissection solution supplemented with 1 mg·mL−1 BSA, 1 mg·mL−1 papain (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 1 mg·mL−1dl-dithiothreitol for 20–25 min at 37°C. Tissues were then transferred to a pre-warmed 2 mL of dissection solution supplemented with 1 mg·mL−1 BSA, 0.5 mg·mL−1 collagenase (type II from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA), 0.5 mg·mL−1 trypsin inhibitor and 100 μM CaCl2 for 12–15 min at 37°C. The digested DSM tissues were washed several times with dissection solution supplemented with BSA and then were gently triturated with fire polished Pasture pipette to disperse DSM single cells. Freshly isolated DSM cells were used for patch-clamp recordings, single-cell reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) and immunocytochemistry experiments.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

DSM total RNA was extracted from fresh DSM isolated strips and enzymatically isolated DSM single cells as described previously (Chen and Petkov, 2009; Hristov et al., 2011; Afeli et al., 2012a; Parajuli et al., 2012). Briefly, 50–100 individual DSM cells were collected in RNAlater using an Axiovert 40CFL microscope with Nomarski interference contrast (Carl Zeiss, Microimaging GmbH, Germany), a glass micropipette and a MP-285/ROE micromanipulator (Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA, USA). Total RNA was isolated from DSM single cells and whole DSM tissues using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was prepared using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA) and Oligo d(T) primers. The cDNA product was amplified using GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega Co.), gene-specific primers (Table 1) and mastercycler gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). All gene-specific primers were designed using Gene runner software (version 3.01; Hastings Software, Inc. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY, USA) based on the completed rat mRNA sequences in Genebank. Rat brain tissue was used as the positive control, and omission of the reverse transcriptase (–RT) in RT-PCR reaction mixture was used for the negative control. PCR products were purified using the GenElute PCR Clean-Up Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) and sequenced at the University of South Carolina Environmental Genomics facility for sequence confirmation.

Table 1.

Primers used for the RT-PCR experiments

| Channels | Forward | Reverse | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SK1 | TCATGACCATCTGCCCTGGCAC | CCGGCTTTGGTCTGGCTTCTTC | 428 |

| SK2 | TGCGCTCATCTTCGGCATGTTC | AAGCCGGGCTGTCCATGTGAAC | 313 |

| SK3 | GCTATCCGCCAGTCATCTGCAC | CCTTATCGAGGCCGAACCTGAG | 480 |

| IK(SK4) | TGCCAGCCCATCGATTCTCTTC | TTCAACAAGGCGGAGAAACACG | 330 |

bp, base pairs.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed as previously described (Chen and Petkov, 2009; Hristov et al., 2011). Briefly, freshly isolated DSM cells were dropped on poly-l-lysine coated slides and allowed to settle for 1 h at room temperature. DSM cells were fixed with pre-warmed 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were washed two times with PBS, blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 10% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Once again, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies: anti-KCa2.1 (KCNN1, SK1); anti-KCa2.2 (KCNN2, SK2); anti-KCa2.3 (KCNN3, SK3) or anti-KCa3.1 (KCNN4, IK, SK4); 1:100; Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel) at 37°C for 1 h. Next, cells were washed two times with PBS and labelled with secondary antibodies (Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, at 1:100, PBS/3% normal donkey serum/0.01% Triton X-100; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h in the dark. After labelling, DSM cells were washed with PBS and incubated with phalloidin for 1 h in the dark. Cells were then washed two more times and incubated with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 15 min and washed again, then mounted onto slides with DABCO (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Control treatments were carried out by absorption of the primary antibody by a competing peptide for confirming the specificity of the primary antibody. Images at ×63 objective were acquired with an LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). The slides for each group were imaged with the same laser power, gain settings and pinhole for the controls and antibody treatment.

Electrophysiological recordings

The conventional and amphotericin-B perforated whole cell patch-clamp configurations were used to record whole cell currents and RMP, respectively, from freshly isolated rat DSM single cells; 0.2–0.5 mL of DSM cell suspension were dropped into a recording chamber, and cells were allowed to adhere to the glass bottom for ∼20 min. DSM cells were washed several times with bath solution to remove cell debris and poorly adhered DSM cells. Distinct, elongated, bright and shiny DSM cells (when viewed under phase-contrast Axiovert 40CFL microscope) were selected for patch-clamp recordings. Voltage-step depolarization-evoked whole cell SK currents (voltage clamp) and RMP (current clamp) were recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, Digidata 1322A and pCLAMP version 10.2 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). The recorded currents were filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filters 900CT/9L8L (Frequency Devices, Inc., Ottowa, IL, USA). The patch-clamp pipettes were prepared from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and pulled using a Narishige PP-830 vertical puller. The patch-clamp pipettes were polished with a Micro Forge MF-830 fire polisher (Narishige Group, Tokyo, Japan) to give a final tip resistance of 4–7 MΩ. To study if NS309 activates the SK channels, the influence of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) and IK channels was suppressed by paxilline, a selective BK channel inhibitor, and TRAM-34, a selective IK channel inhibitor, respectively. Whole cell K+ currents were recorded by holding the DSM cells at −70 mV, and voltage depolarization was applied from −40 to +40 mV for 200 ms in 10 mV increments, and then cells were repolarized back to −70 mV. All patch-clamp experiments were conducted at room temperature (22–23°C).

Isometric DSM tension recordings

Small DSM strips (5–7 mm long and 2–3 mm wide) devoid of urothelium and lamina propria were excised from rat urinary bladders. One end of the strip was attached to the bottom of a temperature-controlled (37°C) jacketed water bath (10 mL) containing physiological saline solution (PSS) aerated with 95% O2–5% CO2. The other end of the DSM strip was attached to an isometric force transducer. The DSM strips were initially stretched to ∼1 g force and washed with fresh PSS solution every 15 min during an equilibration period of 45–60 min. The effects of NS309 were examined on spontaneously and pharmacologically induced DSM contractions. All experiments with myogenic contractions were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX, a selective neuronal voltage-gated Na+ channel inhibitor, to block any potential neurotransmitter release. In the first experimental protocol, cumulative concentrations of NS309 (100 nM–30 μM) in the presence or absence of SK/IK channel inhibitors were applied in 10 min intervals. In the next experimental protocol, DSM phasic contractions were pharmacologically induced by either 1 μM carbachol, a cholinergic agonist, or by KCl (either 20 or 60 mM), a depolarizing agent. After stabilization of the spontaneous phasic or tonic contractions induced by carbachol or KCl, NS309 was applied to the bath solution. The effect of NS309 on nerve-evoked contractions was evaluated by applying EFS using a pair of platinum electrodes mounted in the tissue bath in parallel to the DSM strip. The EFS pulses were generated by a PHM-152I stimulator (MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA), and the EFS pulse parameters were as follows: 0.75 ms pulse width, 20 V pulse amplitude, 3 s stimulus duration; and polarity was reversed for alternating pulses. For EFS studies, after the equilibration period, DSM strips were subjected to increasing frequencies from 0.5–50 Hz at 3 min intervals. The DSM contraction amplitude at EFS frequency of 50 Hz under control conditions was taken to be 100%, and the data were normalized. The spontaneous, pharmacologically and EFS-induced phasic contractions were recorded using a Myomed myograph system (MED Associates, Inc.).

Solutions and drugs

Freshly prepared dissection solution had the following composition (in mM): 80 monosodium glutamate, 55 NaCl, 6 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2 and the pH adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH. PSS was prepared freshly and had the following composition (in mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4 and 11 glucose, and was aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2 to maintain pH of 7.4. Extracellular (bath) solution used for patch-clamp experiments contained (in mM): 134 NaCl, 6 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES and pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The patch-pipette solution for perforated patch-clamp had (in mM): 110 potassium aspartate, 30 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.05 EGTA and pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. The patch-pipette solution for conventional whole-cell patch-clamp contained (in mM): 134 KCl, 0.207 CaCl2, 5.53 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 HEDTA and pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. Free Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the pipette solution were calculated as 3 μM and 1 mM, respectively, using WEBMAXC Standard software (Stanford, CA, USA). Freshly dissolved amphotericin-B (200 μg·mL−1) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the pipette solution before the experiment and replaced every 1–2 h. TRAM-34, apamin, NS309 and TTX were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Apamin and carbachol were dissolved in double distilled water, while TRAM-34 and NS309 were dissolved in DMSO. The DMSO concentration in the bath solution did not exceed 0.1%. The drug/molecular target nomenclature used in the present study conforms to BJP's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Data analysis and statistics

Clampfit 10.2 software (Molecular Device, Union City, CA, USA) was used to analyse patch-clamp data. To evaluate whole cell K+ currents, the mean values of the last 50 ms pulse of 200 ms depolarization step of average 6–10 files recorded every 1 min over an 8 to 10 min period before and after application of test compounds were calculated. Stable patch-clamp recordings over an 8 to 10 min period were used as controls, and continuous recordings over another 8 to 10 min period following application of test compounds were used to examine the effects of NS309 or SK/IK channel inhibitors on rat DSM whole cell currents or RMP. To analyse the effect of the compounds on spontaneous phasic contractions, a 5 min stable recording prior to the application of the compounds was analysed for the control, and another 5 min recording was analysed after application of each concentration of the compounds. Analysis of the DSM contraction parameters was performed with MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft, Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA). The DSM contractile activity was quantified by measuring the average maximal contraction amplitude, muscle integral force (the area under the curve of the phasic contractions), duration (defined as width of contraction at 50% of the amplitude), frequency (contractions per min) and tone (phasic contraction baseline curve). To estimate the relative changes in the phasic contraction parameters, the data were normalized and expressed as percentages with respect to control values. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 4.03 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Corel Draw Graphic Suite X3 software (Corel Co., Mountain View, CA, USA) was used for data presentation. The data are expressed as mean ± SE for the n (the number of DSM strips or cells) isolated from N (number of rats). Statistical analysis was performed using either two-tailed paired Student's t-test or two-way anova followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. A P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

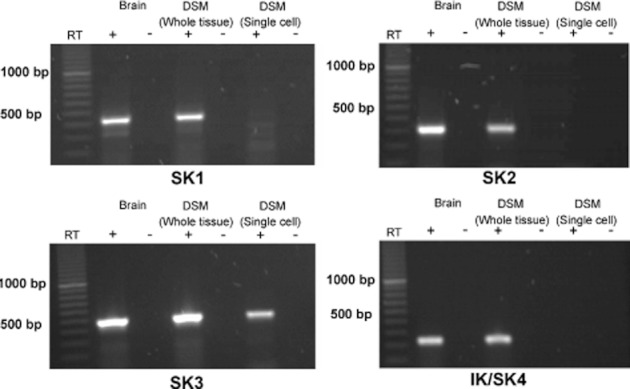

Rat DSM cells express mRNA message for SK3 channel

We detected expression of mRNA messages for SK1, SK2, SK3 and IK (SK4) channels in rat DSM whole tissue (Figure 1). Detection of mRNA messages from non-DSM cells such as fibroblasts, neuronal cells and vascular smooth muscle was avoided by performing RT-PCR experiments on freshly isolated single-DSM cells. Single-cell RT-PCR results showed mRNA messages only for SK3 channel expression. In contrast, mRNA messages were not detected for SK1, SK2 and IK (SK4) channels in freshly isolated DSM single cells (Figure 1). This suggests that the SK3 channel is the predominant SK channel subtype expressed in rat DSM cells. To further investigate the expression of SK/IK channel protein in freshly isolated DSM single cells, we performed immunocytochemistry using specific antibodies against the SK1-3 and IK channels.

Figure 1.

RT-PCR detection of mRNA messages for SK3 channels in DSM whole tissue and freshly isolated single cells. mRNA expression for the SK3 channel was detected in DSM whole tissue and freshly isolated DSM single cells, whereas no mRNA expression was observed for SK1, SK2 and IK (SK4) channels in DSM single cells. Rat brain was used as a positive control. Negative control experiments carried out with omission of RT-enzyme (−RT) in reaction mixtures showed no products. Illustrated gel images are representations of at least four independent RT-PCR experiments based on RNA extracted from four rats.

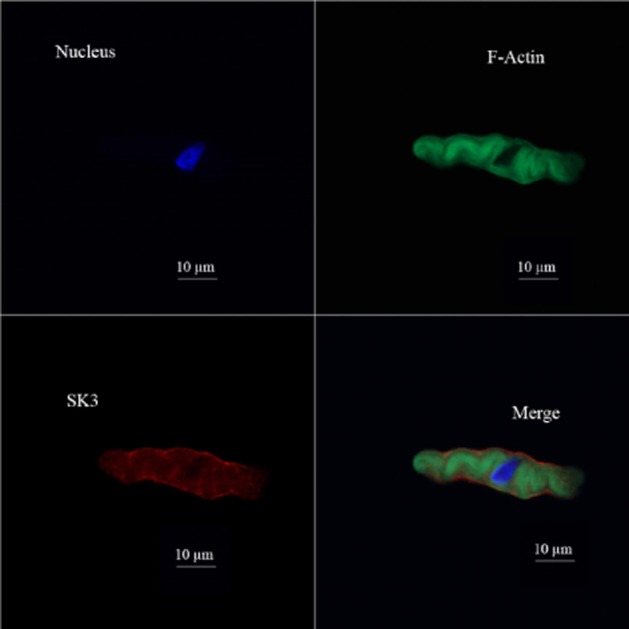

Rat DSM cells express protein for SK3 channel

We detected SK3, but not SK1, SK2 and IK/SK4, channels at the protein level in freshly isolated DSM cells using channel specific antibodies for each channel subtype. Immunocytochemistry results confirmed the expression of only SK3 channel protein in DSM single cells and demonstrated that the SK3 channel protein is specifically localized to the cell membrane (Figure 2). Next, using the patch-clamp technique, we explored how the pharmacological activation of SK3 channels with NS309 affects DSM cell excitability.

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical detection of SK3 channel in freshly isolated DSM single cells using SK3 channel-specific antibody. Red staining (lower left panel) indicates the detection of SK3 channel. Cell nuclei are shown in blue (upper left panel); F-actin is shown in green (upper right panel). The merged image (lower right panel) illustrates the overlap of all three images. Images were obtained by a confocal microscope at 63× oil objective and clearly demonstrate that the SK3 channel proteins were localized to the cell membrane. Illustrated confocal images are the representations of at least four independent experiments from four different rats.

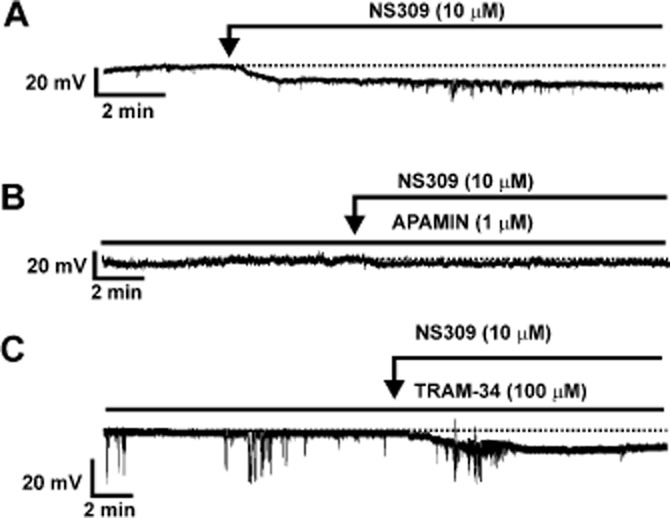

Pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 hyperpolarizes DSM cell RMP

The role of the SK/IK channels in the regulation of rat DSM cell RMP was examined using the current-clamp mode (I = 0) of amphotericin-B perforated whole cell patch-clamp technique. The advantage of using the perforated patch-clamp technique is that it preserves the native cell environment including intracellular Ca2+ signalling mechanisms. The average DSM cell's capacitance of all cells used in the patch-clamp experiments was 26.2 ± 0.9 pF (n = 161, N = 53) and did not change during the course of the experiments. We chose the 10 μM NS309 concentration for all patch-clamp experiments based on the EC50 of the concentration–response curve of NS309 for the spontaneous phasic contractions. Our results showed that 10 μM NS309 significantly hyperpolarized rat DSM cell RMP from a control value of −23.0 ± 2.9 to −26.6 ± 3.4 mV (n = 9, N = 5; P < 0.05, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Activation of SK channels with NS309 hyperpolarizes the rat DSM cell RMP. (A) A representative recording from a freshly isolated DSM cell in current-clamp mode illustrating that NS309 hyperpolarized DSM cell RMP. (B) A representative recording illustrating that pharmacological inhibition of SK channels with apamin prevented the NS309-induced hyperpolarizing effect on rat DSM cell RMP. (C) A representative recording illustrating that pharmacological inhibition of IK channels with TRAM-34, a selective inhibitor of the IK channels, did not change the NS309-induced hyperpolarizing effect on rat DSM RMP.

To explore if NS309-induced DSM cell membrane hyperpolarization was mediated via activation of the SK channels, we examined the effect of 1 μM apamin. Apamin (1 μM) per se did not significantly change the DSM cell RMP. In the absence of apamin, DSM cell RMP was −28.3 ± 4.0 mV, and it was −29.6 ± 3.5 mV in the presence of apamin (n = 8, N = 5; P > 0.05). In the presence of 1 μM apamin, NS309 did not have a hyperpolarizing effect on DSM cell RMP. As shown in Figure 3B, DSM cell RMP was −25.2 ± 3.3 mV in the presence of apamin alone, and it was −27.6 ± 3.1 mV in the presence of both apamin and NS309 (n = 9, N = 6; P > 0.05, Figure 3B).

To explore if NS309-induced DSM cell membrane hyperpolarization was mediated via activation of IK channels, we examined the effect of TRAM-34 on DSM cell RMP. Our data showed that 100 μM TRAM-34 per se did not change the DSM cell RMP. In the absence of TRAM-34, DSM cell RMP was −20.0 ± 2.4 mV and −19.1 ± 2.2 mV in its presence (n = 7, N = 7; P > 0.05). Under conditions of IK channel inhibition with TRAM-34, 10 μM NS309 still significantly hyperpolarized the DSM cell RMP from −23.4 ± 2.4 to −26.2 ± 2.7 mV (n = 11, N = 7; P < 0.05, Figure 3C). In the presence of both 1 μM apamin and 100 μM TRAM-34, DSM cell RMP was −23.8 ± 4.0 mV and the subsequent addition of 10 μM NS309 did not have a significant effect on RMP (–25.6 ± 4.8 mV) (n = 5, N = 3; P > 0.05).

Taken together, our current-clamp data showed that NS309 hyperpolarized rat DSM RMP via activation of SK but not IK channels.

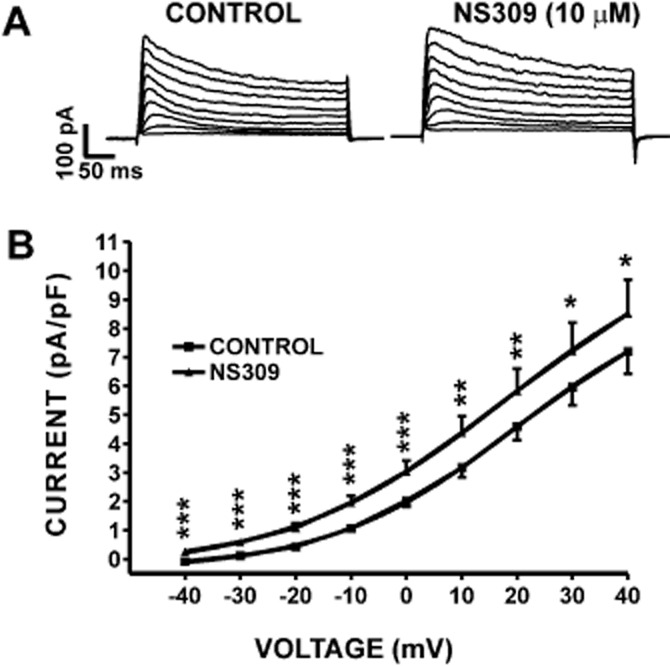

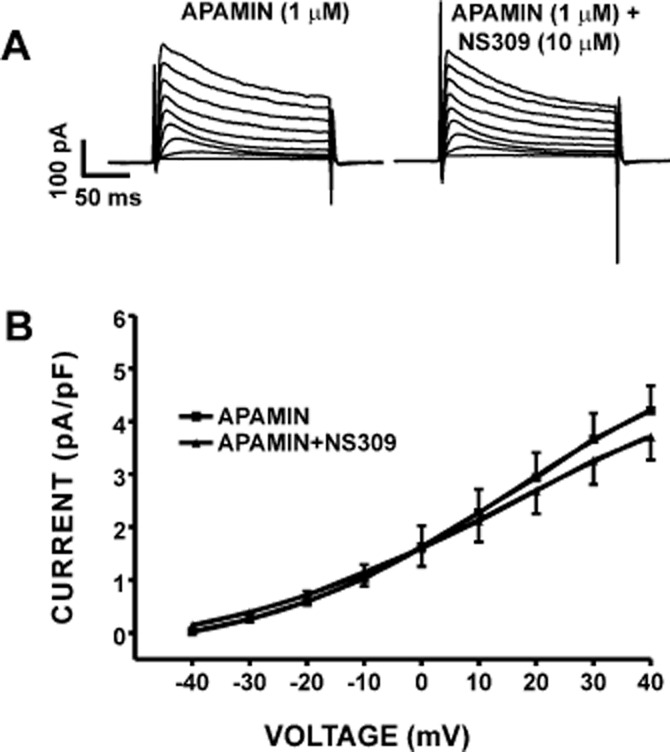

NS309 increases the whole cell SK currents in freshly isolated DSM cells

In this experimental series, we performed conventional whole cell patch-clamp experiments and examined the effect of NS309 on whole cell K+ currents in freshly isolated DSM cells. The conventional whole cell patch-clamp technique allowed us to control the intracellular Ca2+ concentration at 3 μM free Ca2+ during the experiments. NS309 (10 μM) activated the whole cell K+ currents evoked by depolarizing voltages in the presence of BK and IK channel blockers paxilline (300 nM) and TRAM-34 (1 μM) respectively (Figure 4). Current–voltage relationships showed that NS309 significantly increased the whole cell K+ currents (n = 12, N = 8; P < 0.05; Figure 4B). To explore if NS309 increased K+ currents were mediated via activation of SK channels, we also performed experiments by pretreating DSM cells with 1 μM apamin and examining the effects of NS309 (Figure 5A). Inhibition of SK channels with 1 μM apamin prevented the NS309 effect on the whole cell K+ currents. Current–voltage relationships showed that NS309 did not affect the whole cell K+ currents significantly in the presence of 1 μM apamin (n = 8, N = 6; P > 0.05; Figure 5B). These results provide evidence that NS309-induced whole cell K+ currents were due to activation of the SK channels. Thus, our voltage-clamp data support the RMP data, which collectively suggest that in DSM cells NS309 selectively acts on the SK channels to decrease the DSM cell excitability. Next, we examined how the pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 modulates rat DSM contractility.

Figure 4.

Pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 increased whole cell K+ current in freshly isolated DSM cells. (A) Representative conventional voltage-clamp recordings illustrating that NS309 (10 μM) increased the whole cell SK current in the voltage range from −40 to +40 mV. (B) Current–voltage relationships illustrating the effect of NS309 on the whole cell SK current (n = 12, N = 8; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005). SK currents were recorded in the presence of paxilline and TRAM-34, respective inhibitors of the BK and IK channels.

Figure 5.

Pharmacological inhibition of SK channels with 1 μM apamin abolished the activating effect of NS309 on the whole cell K+ current in freshly isolated DSM cells. (A) Representative conventional voltage-clamp recordings illustrating that blocking the SK channels with 1 μM apamin decreased the whole cell K+ current. In the presence of 1 μM apamin, 10 μM NS309 did not affect the whole cell K+ currents. (B) Current–voltage relationships depicting a lack of NS309 effect when the SK channels were blocked with 1 μM apamin (n = 8, N = 6; P > 0.05). SK currents were recorded in the presence of paxilline and TRAM-34.

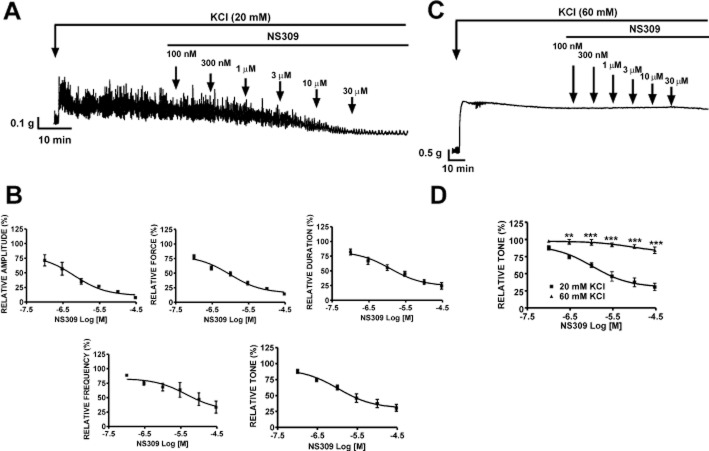

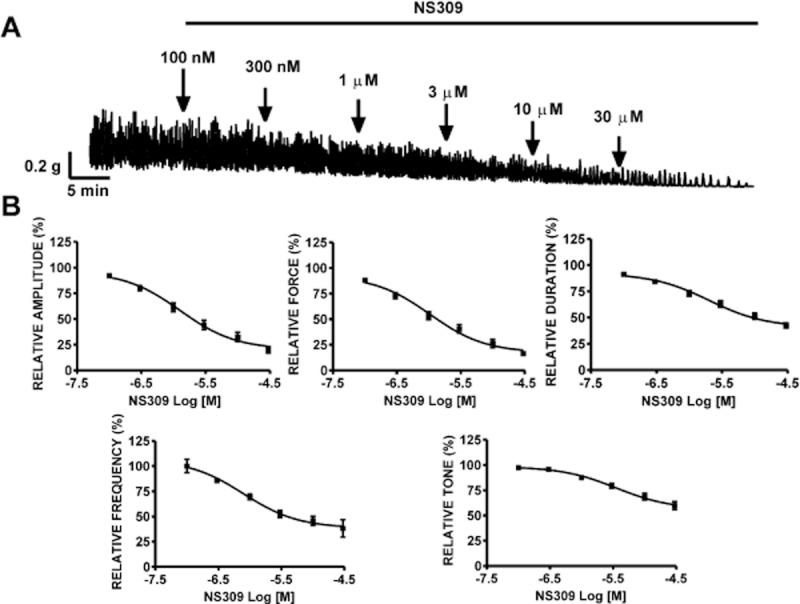

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on spontaneous phasic contractions in DSM-isolated strips

The effects of SK channel activation with NS309 in rat DSM-isolated strips were studied by isometric DSM tension recordings. NS309 significantly inhibited the spontaneous phasic contractions of rat DSM isolated strips in a concentration-dependent manner (0.1–30 μM; Figure 6A). At the highest applied NS309 concentration (30 μM), there was a significant inhibition of DSM spontaneous phasic contractions: the contraction amplitude was decreased by 80.0 ± 3.1%, muscle integral force by 83.7 ± 2.3%, contraction duration by 58.0 ± 2.9%, contraction frequency by 61.8 ± 8.6% and muscle tone by 40.2 ± 4.0% (n = 17, N = 9; P < 0.001). The concentration–response curves of NS309 for all contraction parameters of the spontaneous contractions are shown in Figure 6B. The EC50 values for NS309-induced inhibition of phasic contraction parameters were in the range of 1–4 μM.

Figure 6.

NS309 inhibited spontaneous phasic contractions of rat DSM isolated strips. (A) A representative recording showing the spontaneous phasic contractions of rat DSM strip and the concentration-dependent inhibitory effects of NS309. Subsequent concentrations of NS309 were applied cumulatively at points indicated by the arrows. NS309 inhibited the spontaneous phasic contractions in a concentration-dependent manner (0.1–30 μM). (B). Cumulative concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effects of NS309 on the contraction amplitude, muscle integral force, contraction duration, contraction frequency and muscle tone (n = 17, N = 9). All recordings were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX.

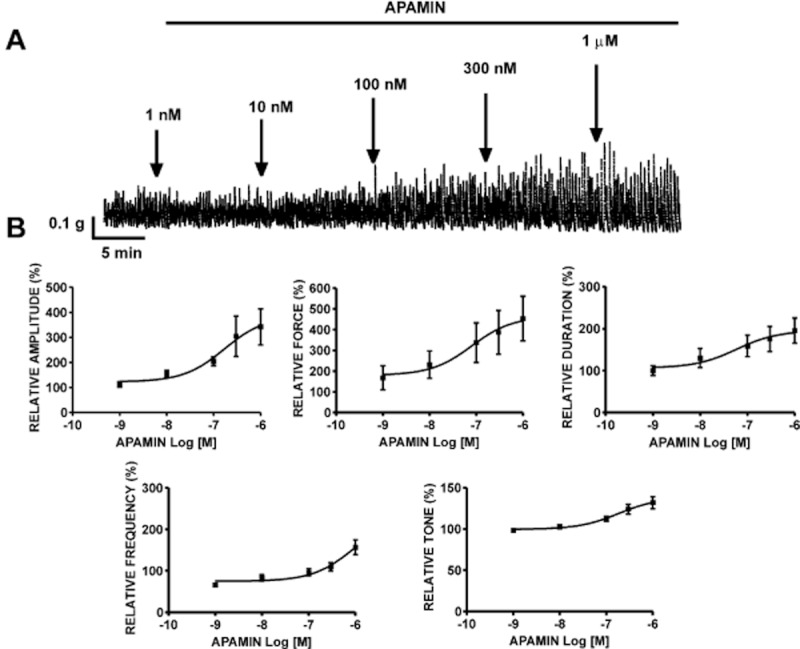

Effect of SK channels pharmacological inhibition on the spontaneous phasic contractions in DSM isolated strips

We next evaluated the functional importance of SK channels in rat DSM using the selective SK channel inhibitor, apamin. Rat DSM isolated strips exhibiting spontaneous phasic contractions were treated with apamin (1 nM–1 μM). Apamin caused a concentration-dependent increase in the phasic contractions, indicating that the apamin-sensitive SK channels are involved in the regulation of rat DSM contractility. At the highest concentration of apamin tested (1 μM), the contraction amplitude was increased by 242.4 ± 72.3%, muscle integral force by 353.9 ± 107.1%, contraction duration by 95.7 ± 29.7%, contraction frequency by 57.2 ± 17.9% and muscle tone by 32.0 ± 7.3% (n = 6, N = 4; P < 0.05; Figure 7A). Figure 7B shows the concentration–response curves of apamin-induced increase in all DSM contraction parameters. We next explored the potential functional role of IK channels in rat DSM contractility, using TRAM-34. The concentration–response curves for TRAM-34 (1–100 μM) on DSM spontaneous phasic contractions showed no significant change in any of the contraction parameters (n = 4, N = 4; P > 0.05). These findings further support our RT-PCR and patch-clamp results and suggest that IK channels do not play a functional role in regulating rat DSM spontaneous phasic contractions.

Figure 7.

Effects of SK channel inhibitor apamin on rat DSM spontaneous contractions. (A) A representative recording of DSM spontaneous phasic contractions demonstrating the contractile effect of cumulative administration of apamin (1 nM–1 μM). (B) Cumulative concentration–response curves for the effects of apamin on contraction amplitude, muscle integral force, contraction duration, contraction frequency and muscle tone (n = 6, N = 4). All recordings were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX.

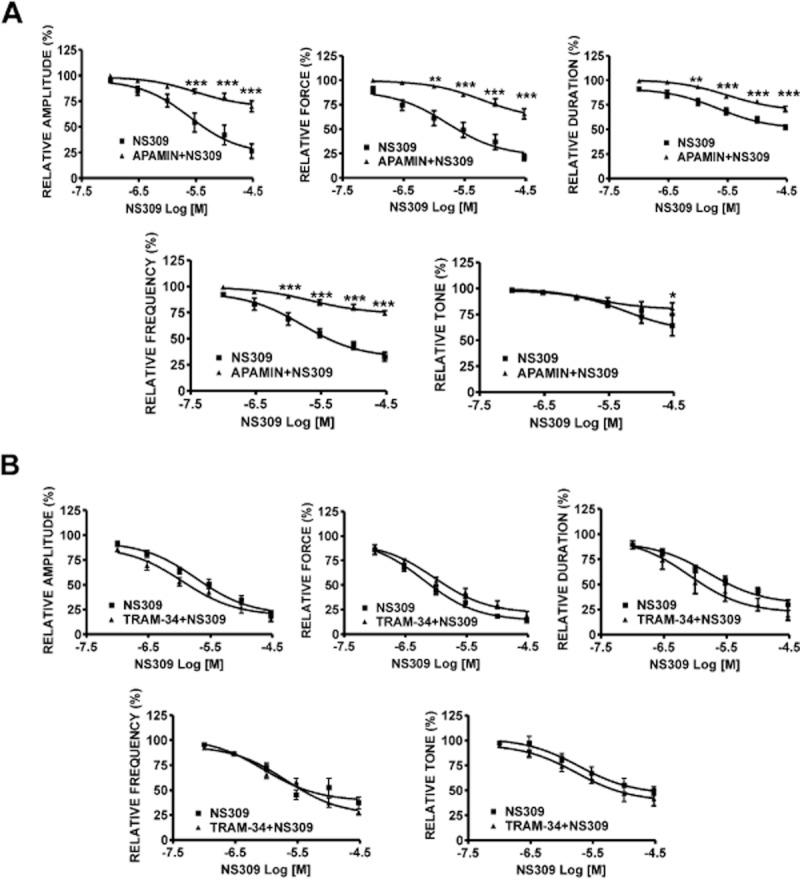

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on DSM contractility are mediated by the SK channels

In order to determine whether the inhibitory effects of NS309 were mediated by SK or IK channels, we pre-incubated the muscle strips with either 1 μM apamin or 100 μM TRAM-34. The inhibitory effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) on all contraction parameters was antagonized by 1 μM apamin (n = 6, N = 4; P < 0.05; Figure 8A). In another set of experiments, rat DSM isolated strips were pre-incubated with TRAM-34. The concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effects of NS309 were not significantly different in the presence or absence of TRAM-34 (n = 6, N = 4; P > 0.05; Figure 8B). These results confirm the lack of functional IK channel expression, which is consistent with our findings from RT-PCR and patch-clamp data.

Figure 8.

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on spontaneous phasic contractions of rat DSM isolated strips in the presence or absence of SK or IK channel inhibitors. (A) Cumulative concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effects of NS309 in the absence or presence of 1 μM apamin in rat DSM isolated strips. The concentration-dependent DSM relaxation induced by NS309 was greatly attenuated in the presence of 1 μM apamin (n = 6, N = 4; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005). (B) Cumulative concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effects of NS309 in the absence or presence of 100 μM TRAM-34 in rat DSM isolated strips. NS309-induced inhibitory response was not affected in the presence of TRAM-34 (n = 6, N = 4; P > 0.05). All recordings were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX.

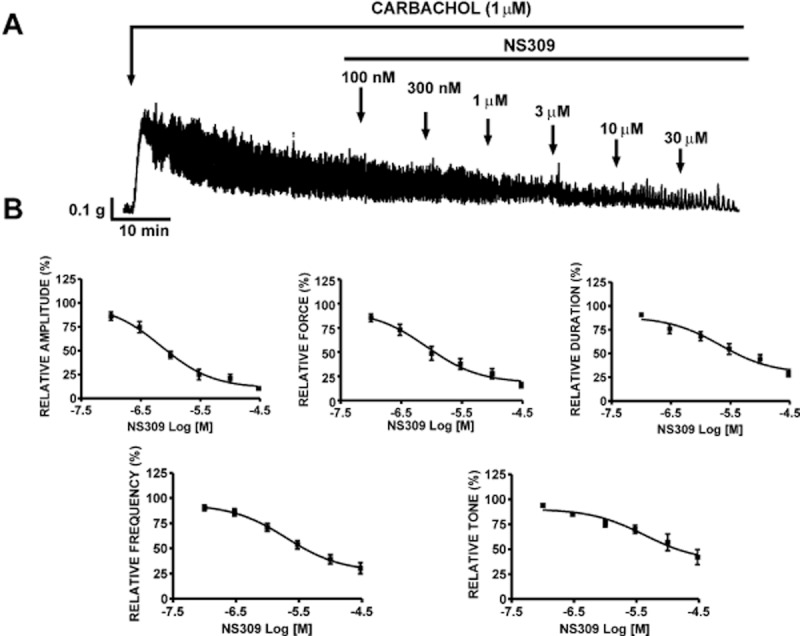

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on DSM contractile responses induced by carbachol

We next evaluated the effects of SK channel activation with NS309 on muscarinic receptor-mediated contractions in rat DSM-isolated strips. DSM contractions were evoked by the muscarinic receptor agonist, carbachol (1 μM). NS309 effectively suppressed the carbachol-induced contractions in a concentration-dependent manner (0.1–30 μM; Figure 9A). NS309 (30 μM) decreased the contraction amplitude by 89.8 ± 2.1%, muscle integral force by 84.6 ± 2.9%, contraction duration by 70.6 ± 3.8%, contraction frequency by 69.6 ± 5.6% and muscle tone by 57.8 ± 7.5% (n = 5, N = 5; P < 0.05; Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

Relaxant effects of NS309 on carbachol (1 μM)-induced contractions in DSM isolated strips. (A) A representative recording of carbachol-induced phasic contractions and the inhibitory effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) in a DSM isolated strip. (B) Cumulative concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effects of NS309 on carbachol-induced contractions of DSM isolated strips (n = 5, N = 5). All recordings were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX.

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on KCl-induced phasic and tonic contractions in DSM-isolated strips

In this experimental series, DSM phasic contractions were elicited under conditions of mild depolarization with 20 mM KCl. After the DSM contractions were stabilized, increasing concentrations of the NS309 were added cumulatively to obtain concentration–response curves. NS309 suppressed 20 mM KCl-induced phasic contractions in a concentration-dependent manner (0.1–30 μM; Figure 10A). NS309 (30 μM) decreased the contraction amplitude by 92.3 ± 1.2%, muscle integral force by 85.6 ± 1.5%, contraction duration by 75.4 ± 5.5%, contraction frequency by 66.5 ± 10.4% and muscle tone by 69.3 ± 5.3% (n = 5, N = 5; P < 0.05; Figure 10B). To determine if the inhibitory effect of NS309 was consistent with activation of K+ channels, we examined the effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) on DSM isolated strips under conditions of elevated extracellular K+ (60 mM KCl). NS309 (30 μM) did not change significantly the 60 mM KCl-induced muscle tone (n = 5, N = 4; P > 0.05; Figure 10C and D). We observed no inhibitory effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) on 60 mM KCl-induced tonic contractions as compared with the significant inhibitory effects on the 20 mM KCl-induced tonic contractions in DSM isolated strips (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Relaxant effects of NS309 on KCl-induced contractions in DSM isolated strips. (A) A representative original recording of 20 mM KCl-induced phasic contractions and the inhibitory effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) in a DSM isolated strip. (B) Cumulative concentration–response curves for the inhibitory effect of NS309 after pre-contraction of DSM strips with 20 mM KCl (n = 5, N = 5; P < 0.05). (C) A representative original recording illustrating no inhibitory effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) on 60 mM KCl-induced tonic contractions of a DSM isolated strip. (D) Cumulative concentration–response curves showing no effect of NS309 (0.1–30 μM) on the 60 mM KCl-induced tonic contraction (n = 5, N = 4; P > 0.05 vs. control) and significant difference with the NS309 effects on the 20 mM KCl-induced tonic contraction in DSM isolated strips (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005). All recordings were performed in the presence of 1 μM TTX.

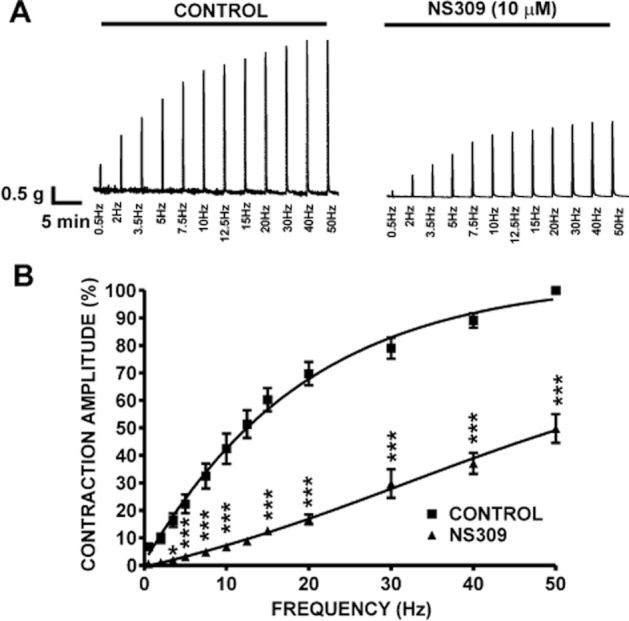

Inhibitory effects of NS309 on EFS-induced contractions in DSM-isolated strips

Next, we examined the effects of NS309 on the nerve-evoked contractions elicited by EFS (stimulation frequency 0.5–50 Hz). Pharmacological activation of SK channels with 10 μM NS309 significantly reduced the amplitude of the EFS-induced contraction in DSM-isolated strips (n = 6, N = 4; P < 0.05; Figure 11). At the highest EFS frequency of 50 Hz, 10 μM NS309 inhibited the amplitude of EFS-induced contraction by 50.2 ± 5.2% (n = 6, N = 4; P < 0.05; Figure 11A and B). These findings suggest that pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 significantly suppresses the nerve-evoked contractions of rat DSM isolated strips.

Figure 11.

Pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 significantly reduced the EFS-induced contractions in rat DSM isolated strips. (A) Representative recordings of EFS-induced contractions (stimulation frequency 0.5–50 Hz) in the absence of NS309 (control) and 30 min after application of 10 μM NS309. (B) Frequency–response curves illustrating a significant decrease in the amplitude of EFS-induced contractions after application of 10 μM NS309 (n = 6, N = 4; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we identified the SK3 channel subtype at both mRNA and protein levels as the only channel expressed in rat DSM single cells among all SK/IK channel subtypes. Pharmacological activation of DSM SK channels with NS309 hyperpolarized the DSM cell RMP, increased the whole cell SK currents in freshly isolated DSM cells and effectively inhibited the spontaneous, pharmacologically and EFS-induced contractions of rat DSM-isolated strips.

Identification of specific SK channel subtypes responsible for channel function is not possible using a pharmacological approach due to the lack of subtype selective SK channel modulators (Hougaard et al., 2007). For this reason, we performed the single-cell RT-PCR experiments to identify the mRNA expression for all known SK (1–3) and IK (SK4) channels in rat DSM (Figure 1). We detected mRNA expression for only SK3 channels out of all known SK (1–3) and IK (SK4) channel isoforms in freshly isolated rat DSM single cells. We confirmed the expression of only SK3 channels at the protein level in freshly isolated DSM single cells (Figure 2). The immunocytochemical detection of SK3 channel protein in DSM single cells further indicated that only mRNA messages for SK3 channels came from DSM cells, whereas mRNA messages for SK1, SK2 and IK channels detected in whole DSM tissues (Figure 1) most likely came from non-DSM cells such as neuronal, fibroblasts, ICC-like or vascular smooth muscle cells. Molecular expression of SK and IK channels has been demonstrated in DSM of mice (Ohya et al., 2000) and guinea pigs (Parajuli et al., 2012). Unlike previous findings in mice and guinea pigs, we detected mRNA expression for only the SK3 channel but not for SK1, SK2 and IK channels in rat DSM single cells. Recently, our research group has demonstrated that SK, SK3 in particular, but not IK channels contribute to the regulation of human DSM function (Afeli et al., 2012b). These results suggest that expression of SK and IK channels may be attributed to species differences. Furthermore, our patch-clamp and functional studies at both cellular and tissue levels demonstrated that NS309-induced inhibition of DSM excitability and contractility was mediated by selective activation of SK channels. Therefore, our single-cell RT-PCR and immunocytochemistry results combined with patch-clamp and functional studies on DSM contractility suggest that NS309-induced decrease in DSM cell excitability and contractility is exclusively due to activation of the SK3 channels.

In the present study, we reported that activation of SK channels with NS309 hyperpolarized the RMP by ∼3 mV (Figure 3) and significantly increased the whole cell SK currents (Figure 4). Both effects were not observed in the presence of apamin (Figures 3 and 5). Furthermore, small but statistically significant SK current activation was also observed at a holding potential in the range of −40 to −30 mV, which is close to the RMP values in DSM (Petkov et al., 2001b). This clearly explains the hyperpolarization effect caused by NS309 in DSM cells. Using KATP channel activators, we have previously demonstrated that a modest negative shift of the RMP is sufficient to cause a substantial inhibition of the spontaneous phasic contractions in guinea pig DSM (Petkov et al., 2001b). Our present findings are consistent with this mechanism because SK channel activation with NS309 caused a modest DSM cell membrane hyperpolarization, and this modulation dramatically reduced the spontaneous phasic contractions (Figures 3 and 6). We have also shown that such a small change in the RMP due to an activation of SK channels can cause a robust inhibition of the spontaneous and pharmacologically induced phasic contractions in guinea pig DSM (Parajuli et al., 2012).

We systematically evaluated all parameters of both spontaneous phasic contractions and pharmacologically induced contractions in rat DSM isolated strips, including contraction amplitude, muscle integral force, contraction frequency, contraction duration and muscle tone to address how the pharmacological activation of SK channels modulates the DSM contractility. The underlying cause of DSM spontaneous phasic contractions is the spontaneous action potential and associated increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Hashitani et al., 2004; Petkov, 2012). We demonstrated that NS309 caused DSM cell membrane hyperpolarization and thus dramatically decreased the DSM spontaneous phasic contractions amplitude, muscle integral force, contraction frequency, contraction duration and muscle tone with EC50 in the range of 1–4 μM (Figure 6). These inhibitory effects of NS309 were blocked by pretreatment of DSM isolated strips with apamin, a selective SK channel inhibitor but not by TRAM-34, a selective IK channel inhibitor.

The functional role of IK channels in physiological and pathological bladder conditions has remained obscure. Our single-cell RT-PCR (mRNA level), immunocytochemistry (protein level), isometric DSM tension recordings and patch-clamp data indicate that IK channels are not expressed in rat DSM and do not play any functional role in regulating DSM excitability and contractility. Therefore, it is clear that all inhibitory effects of NS309 in rat DSM excitability and contractility were due to SK but not IK channel activation.

The urinary bladder is innervated with parasympathetic neurons, which release acetylcholine and ATP. When these neurons are stimulated during the bladder-emptying phase, they induce forceful phasic contractions (Andersson and Arner, 2004; Brading, 2006). Our results showed that phasic contractions evoked by 1 μM carbachol, a muscarinic agonist, were significantly suppressed by NS309 (Figure 9). This suppression of muscarinic receptor agonist-induced phasic contractions with NS309 can be attributed to the activation of SK channels that lead to membrane hyperpolarization and attenuation of Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Similarly, the phasic contractions evoked by 20 mM KCl were also significantly inhibited by NS309 (Figure 10A and B). Unlike an earlier study (Morimura et al., 2006), our data do not provide evidence that NS309 inhibitory effects on rat DSM contractility were due to block of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The lack of NS309 effects on 60 mM KCl-induced tonic contractions (Figure 10C and D) confirmed that NS309 inhibitory effects attribute to the opening of K+ channels, presumably the SK channels as also shown by our patch-clamp data (Figures 5). Moreover, as illustrated in Figure 8A, the inhibitory effects of NS309 on DSM spontaneous phasic contractions were significantly inhibited by pretreatment of the DSM strips with apamin. Collectively, our results clearly demonstrate that the observed NS309 inhibitory effects on DSM contractility are not mediated by inhibition of the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

SK channels are suggested to have a prominent role as a negative-feedback element on extracellular Ca2+ influx-mediated DSM contractility (Andersson and Arner, 2004; Herrera et al., 2005; Petkov, 2012). Furthermore, during an action potential, SK channel activation hyperpolarizes the cell membrane for several hundreds of milliseconds (Stocker et al., 2004). In the present study, SK channel activation with NS309 hyperpolarized rat DSM cell RMP and thus resulted in a drastic inhibition of the spontaneous phasic contractions (Figures 3 and 6). In addition, as shown in Figure 7, pharmacological blockade of SK channels with apamin increased DSM spontaneous phasic contraction amplitude, muscle integral force and contraction duration which is consistent with previous findings in other species (Herrera et al., 2000; Herrera and Nelson, 2002; Hashitani and Brading, 2003b; Herrera et al., 2003; Herrera et al., 2005). Most importantly, apamin antagonized the NS309 inhibitory effects on rat DSM contractility (Figure 8A). Our results support the concept that SK channel pharmacological activation decreases DSM excitability and contractility (Petkov, 2012).

In conclusion, our data reveal that pharmacological activation of SK channels with NS309 decreases rat DSM cell excitability by hyperpolarizing the RMP and inhibits the spontaneous, pharmacologically and EFS-induced DSM contractions. Only SK3 channel expression at both mRNA and protein levels was detected in isolated DSM single cells. Therefore, selective pharmacological activation of SK3 channels could be a promising option for therapeutic control of OAB.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Xiangli Cui for conducting some of the patch-clamp experiments. We also thank to Drs John Malysz and Wenkuan Xin, Mr Qiuping Cheng, Mr Serge Afeli and Ms Amy Smith for the critical evaluation of the manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of HealthDK084284, DK083687 to Georgi V Petkov and by a fellowship from the American Urological Association Foundation Research Scholars Program and the Allergan Foundation to Shankar P Parajuli.

Glossary

- BK channel

large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- DO

detrusor overactivity

- DSM

detrusor smooth muscle

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- IK channel

intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- KV channel

voltage-gated K+ channel

- NS309

6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2, 3-dione 3-oxime

- OAB

overactive bladder

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- RMP

resting membrane potential

- SK channel

small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afeli SA, Hristov KL, Petkov GV. Do beta3-adrenergic receptors play a role in guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle excitability and contractility? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012a;302:F251–F263. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00378.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afeli SA, Rovner ES, Petkov GV. SK but not IK channels regulate human detrusor smooth muscle spontaneous and nerve-evoked contractions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012b;303:F559–F568. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00615.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE, Arner A. Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:935–986. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE, Wein AJ. Pharmacology of the lower urinary tract: basis for current and future treatments of urinary incontinence. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:581–631. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brading AF. Spontaneous activity of lower urinary tract smooth muscles: correlation between ion channels and tissue function. J Physiol. 2006;570(Pt 1):13–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner SA, Milicic I, Daza AV, Coghlan MJ, Gopalakrishnan M. Spontaneous phasic activity of the pig urinary bladder smooth muscle: characteristics and sensitivity to potassium channel modulators. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:639–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Petkov GV. Identification of large conductance calcium activated potassium channel accessory beta4 subunit in rat and mouse bladder smooth muscle. J Urol. 2009;182:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darblade B, Behr-Roussel D, Oger S, Hieble JP, Lebret T, Gorny D, et al. Effects of potassium channel modulators on human detrusor smooth muscle myogenic phasic contractile activity: potential therapeutic targets for overactive bladder. Urology. 2006;68:442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein BJ, Gums JG, Molina E. Newer agents for the management of overactive bladder. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardos G. The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958;30:653–654. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grgic I, Kaistha BP, Hoyer J, Kohler R. Endothelial Ca2+-activated K+ channels in normal and impaired EDHF-dilator responses – relevance to cardiovascular pathologies and drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:509–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF. Electrical properties of detrusor smooth muscles from the pig and human urinary bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2003a;140:146–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF. Ionic basis for the regulation of spontaneous excitation in detrusor smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2003b;140:159–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF, Suzuki H. Correlation between spontaneous electrical, calcium and mechanical activity in detrusor smooth muscle of the guinea-pig bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:183–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate action potential repolarization in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):C110–C117. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Nelson MT. Differential regulation of SK and BK channels by Ca2+ signals from Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in guinea-pig urinary bladder myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;541(Pt 2):483–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions by ryanodine receptors and BK and SK channels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R60–R68. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Pozo MJ, Zvara P, Petkov GV, Bond CT, Adelman JP, et al. Urinary bladder instability induced by selective suppression of the murine small conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK3) channel. J Physiol. 2003;551(Pt 3):893–903. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Etherton B, Nausch B, Nelson MT. Negative feedback regulation of nerve-mediated contractions by KCa channels in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R402–R409. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00488.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard C, Eriksen BL, Jorgensen S, Johansen TH, Dyhring T, Madsen LS, et al. Selective positive modulation of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:655–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard C, Fraser MO, Chien C, Bookout A, Katofiasc M, Jensen BS, et al. A positive modulator of KCa2 and KCa3 channels, 4,5-dichloro-1,3-diethyl-1,3-dihydro-benzoimidazol-2-one (NS4591), inhibits bladder afferent firing in vitro and bladder overactivity in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:28–39. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov KL, Cui X, Brown SM, Liu L, Kellett WF, Petkov GV. Stimulation of beta3-adrenoceptors relaxes rat urinary bladder smooth muscle via activation of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1344–C1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00001.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov KL, Chen M, Kellett WF, Rovner ES, Petkov GV. Large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate human detrusor smooth muscle function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C903–C912. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00495.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov KL, Parajuli SP, Soder RP, Cheng Q, Rovner ES, Petkov GV. Suppression of human detrusor smooth muscle excitability and contractility via pharmacological activation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1632–C1641. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00417.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Okamoto T, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka H, Koike K, Shigenobu K, et al. Effects of different types of K+ channel modulators on the spontaneous myogenic contraction of guinea-pig urinary bladder smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:323–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita M, Yunoki T, Takimoto K, Miyazato M, Kita K, de Groat WC, et al. Effects of bladder outlet obstruction on properties of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat bladder. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1310–R1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00523.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler M, Hirschberg B, Bond CT, Kinzie JM, Marrion NV, Maylie J, et al. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science. 1996;273:1709–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimura K, Yamamura H, Ohya S, Imaizumi Y. Voltage-dependent Ca2+-channel block by openers of intermediate and small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in urinary bladder smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:237–241. doi: 10.1254/jphs.sc0060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JS, Rode F, Rahbek M, Andersson KE, Ronn LC, Bouchelouche K, et al. Effect of the SK/IK channel modulator 4,5-dichloro-1,3-diethyl-1,3-dihydro-benzoimidazol-2-one (NS4591) on contractile force in rat, pig and human detrusor smooth muscle. BJU Int. 2011;108:771–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S, Kimura S, Kitsukawa M, Muraki K, Watanabe M, Imaizumi Y. SK4 encodes intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2000;84:97–100. doi: 10.1254/jjp.84.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandita RK, Ronn LC, Jensen BS, Andersson KE. Urodynamic effects of intravesical administration of the new small/intermediate conductance calcium activated potassium channel activator NS309 in freely moving, conscious rats. J Urol. 2006;176:1220–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli SP, Soder RP, Hristov KL, Petkov GV. Pharmacological activation of small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels with naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine decreases guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle excitability and contractility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:114–123. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov GV. Role of potassium ion channels in detrusor smooth muscle function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov GV, Bonev AD, Heppner TJ, Brenner R, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Beta1-subunit of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel regulates contractile activity of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2001a;537(Pt 2):443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov GV, Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Herrera GM, Nelson MT. Low levels of K(ATP) channel activation decrease excitability and contractility of urinary bladder. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001b;280:R1427–R1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan A, Raman G, Busch C, Schultz T, Zimin PI, Hoyer J, et al. Naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-31), a new activator of KCa2 and KCa3.1 potassium channels, potentiates the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor response and lowers blood pressure. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:281–295. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker M, Hirzel K, D'Hoedt D, Pedarzani P. Matching molecules to function: neuronal Ca2+-activated K+ channels and afterhyperpolarizations. Toxicon. 2004;43:933–949. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobaek D, Teuber L, Jorgensen TD, Ahring PK, Kjaer K, Hansen RS, et al. Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1665:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobaek D, Hougaard C, Johansen TH, Sorensen US, Nielsen EO, Nielsen KS, et al. Inhibitory gating modulation of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels by the synthetic compound (R)-N-(benzimidazol-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphtylamine (NS8593) reduces afterhyperpolarizing current in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1771–1782. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneloe KS, Knorn AM, Doetsch PE, Lashinger ES, Liu AX, Bond CT, et al. Small-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel 2 is the key functional component of SK channels in mouse urinary bladder. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1737–R1743. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00840.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wein AJ, Rackley RR. Overactive bladder: a better understanding of pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. J Urol. 2006;175(3 Pt 2):S5–S10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H, Zhorov BS. K+ channel modulators for the treatment of neurological disorders and autoimmune diseases. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1744–1773. doi: 10.1021/cr078234p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]