Abstract

This investigation was motivated by physician reports that patient compliments often raise ‘red flags’ for them, raising questions about whether compliments are being used in the service of achieving some kind of advantage. Our goal was to understand physician discomfort with patient compliments through analyses of audiotaped surgeon-patient encounters. Using conversation analysis, we demonstrate that both the placement and design of compliments are consequential for how surgeons hear and respond to them. The compliments offered after treatment recommendations are neither designed nor positioned to pursue institutional agendas and are responded to in ways that are largely consistent with compliment responses in everyday interaction, but include modifications that preserve surgeons’ expertise. In contrast, some compliments offered before treatment recommendations pursue specific treatments and engender surgeons’ resistance. Other compliments offered before treatment recommendations do not overtly pursue institutionally-relevant agendas—for example, compliments offered in the opening phase of the visit. We show how these compliments may but need not foreshadow a patient’s upcoming agenda. This work extends our understanding of the interactional functions of compliments, and of the resources patients use to pursue desired outcomes in encounters with healthcare professionals.

Keywords: conversation analysis, compliments, orthopaedic surgery, medical interaction

Introduction

Pleasant words are as a honeycomb, sweet to the soul, and health to the bones.

Proverbs 16: 24

Many sources, including the Bible, suggest that compliments are a valuable source of support and succour. But, is that all they do? In some contexts and certainly in the popular imagination, compliments are also associated with a kind of Machiavellian strategy to manipulate or influence the other to one’s advantage. The multiple functions of compliments give them a slippery quality.

The idea that at least some compliments may be being used in the service of achieving some greater advantage appears to have some resonance in the institutional setting of medicine. While analysing audio-taped patient-surgeon interactions as part of a large field study of informed decision making in medicine, we noted a number of compliments given by patients to surgeons. When mentioned in passing to a physician colleague, he described how he considered compliments from patients to be a ‘red flag’, raising his suspicions about a patient’s underlying motive for what he deemed ‘buttering up’. The following description of the ‘exaggeration reaction patient’ from a chapter on the differential diagnosis of low back pain in a medical textbook on pain management (McCulloch et al. 2001: 393 emphasis added) outlines behaviours associated with a type of patient deemed difficult, and echoes our colleague’s sentiments:

Certain behavioural patterns become apparent after seeing a number of these patients. Some never appear for appointments in spite of weeks of notification. Others appear late for the appointment and do not apologise or state indifferently that the traffic was heavy. There may be an attempt to manipulate your feelings with a compliment about your reputation or your office. There may be an effort to play one doctor against another by making false statements about the other doctor.

These examples suggest that physicians are wary of at least some compliments. Yet need they be? This investigation sought to explore this issue in the context of surgical consultations.

Background

Although empirical work on complimenting in medicine is limited, there is a rich social science literature on compliments, especially within the realm of politeness theory as developed by Brown and Levinson (1987). Briefly, in the process of impression management (Goffman 1959, 1971), people invest in maintaining both their own face (their public identity) and that of others. Social life, however, requires people to carry out a variety of acts that could threaten face: for example, they must make requests or complain, but requests might make them appear needy, or complaints crabby. To accomplish these acts with the least damage to face, interactants use a number of so-called politeness strategies. Compliments have been considered one such strategy; they can reduce social distance and reinforce solidarity between a speaker and hearer, as well as mitigate the effects of a preceding face-threatening act by bestowing positive face onto the person being complimented (Holmes 1988). This suggests that compliments can be ‘action oriented’ above and beyond ‘praising’.

The understanding that individuals might deploy compliments for some advantage is supported by popular literature. For example, Carnegie (1936) claimed that compliments could be used to get people to do things for you or, as the title of his self-help book proclaims, they could help you ‘win friends and influence people’. In the academic literature, compliments have been shown to be used strategically in negotiations (Herbert 1989) or to stress solidarity and maintain rapport with others (Hobbs 2003, Holmes 1988). For Wall et al. (1989: 160), ‘therapeutic compliments’ – that is, praise or affirmation that therapists give to clients – can enhance manoeuvrability, empower clients and promote change in client behaviour. These examples show alternative activities in talk that may be accomplished via compliments, all of which have a somewhat strategic or purposeful essence.

In trying to grasp how flattering remarks do other actions, many authors have used data collection methods which do not describe actual language use in natural settings. Data collected via discourse completion tasks, role-plays, field observation and recall protocols may be constrained by subjects’ memory or experimental conditions, and may not include sufficient granularity to capture interactive features of talk-in-context (Sacks 1984, Golato 2005). As a result, the features of talk that enable some compliments to be used to show admiration while others are not, are left unexamined and unclear. To achieve this level of granularity, audio or video recordings of naturally occurring talk-in-interaction are needed.

Such recordings are the starting point of conversation analytic (CA) research, which aims to reveal how people achieve social order through systematic practices of talk-in-interaction (Heritage 1984, Clayman and Gill 2004). In CA, social actions are seen to be performed in and through talk. Participants design utterances and place them in sequences of talk to make their contributions recognisable as actions; they also draw on the design and placement of others’ utterances to make sense of them as actions and to determine what they call for them (as recipients) to do next. In other words, conversation analysts, like participants in conversation, analyse utterances in context to determine what social actions participants are doing in and through their talk (be it complaining, questioning, blaming, praising, and so on).

CA scholars have contributed some important studies on compliments and compliment responses in everyday interaction. Golato (2005) demonstrated that utterances that look like compliments (i.e. that bear the semantic and syntactic characteristics of a compliment) do not necessarily perform the interactional function or action of praising, commending or showing admiration for the recipient. When analysing compliments’ placement in larger sequences of talk, not simply their syntactic structure, Golato found that a speaker may place a compliment in a particular location in the stream of talk to reproach or criticise a recipient, to perform a hedging pre-request or to provide an account. Compliments may also figure in persuasive work, as when speakers compliment people who are not co-present to imply that a co-present person’s behaviour is problematic (Maynard 1998). In an analysis of a primary care medical visit, Gill (2005) showed how a patient used this procedure to exert pressure on her physician for a diagnostic test; the patient praised her former physician for having provided the test when she was concerned about particular symptoms, implying that the co-present physician should do the same.

CA studies have also shown that compliments may pose interactional difficulties for their recipients. When compliments do the work of praising, recipients face conflicting constraints – to agree with and/or accept the compliment on the one hand, while avoiding self-praise on the other (Pomerantz 1978). These constraints are ‘concurrently relevant but not concurrently satisfiable’ – in other words, to satisfy one preference means that the other preference goes unsatisfied (Pomerantz 1978: 81). Recipients of compliments solve this problem by incorporating features of both agreement and disagreement in their responses. The two primary ways of responding are: (1) evaluation shifts (praise downgrades such as scaled-down agreements and proposals that compliments were exaggerated); and (2) referent shifts (where the recipient of the compliment reassigns praise by shifting the credit away from him or herself to an other-than-self referent) (Pomerantz 1978). These patterns were observed in everyday interactions, and relatively little is known about the interactional constraints compliments pose for recipients in institutional settings like medicine.

In this paper, we analyse compliments that patients provide to co-present physicians (orthopaedic surgeons) in medical encounters. We focus on the different actions patients can do by designing or structuring their compliments in certain ways and positioning them in particular environments in the encounters, and how physicians respond. Specifically, we show that some compliments angle or press for surgeons to make certain medical decisions. We analyse how surgeons handle this pressure, and how they orient towards the special response constraints they are under as medical professionals – that is, experts whom patients are consulting to evaluate their medical problems. This paper aims to contribute to the understanding of compliments in three ways: (1) empirically, it provides further evidence that the action any compliment achieves is a function of the sequential context in which it occurs as well as its design, and reveals that surgeon-recipients orient to special interactional constraints when responding to compliments; (2) practically, it provides insight into the potential interactional functions of compliments, information that will be useful for healthcare professionals; and (3) conceptually, it provides insight into why physicians may be wary of compliments.

Data and method

Our data consisted of audiotapes of routine office visits between 59 older patients (≥ 60 years) and 39 orthopaedic surgeons. Ten patient-to-surgeon compliments were identified in seven of the 59 visits. These visits were recorded in a large Midwestern American city in 2003 and 2004 as part of a study on informed decision making in orthopaedic surgery1. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all participating institutions and patients and surgeons gave informed consent prior to their involvement. All names and identifying references have been changed to protect participants’ identities. We used conversation analysis (CA) to analyse the data (Heritage 1984, Sacks 1992, Schegloff 2007).

The motivation for many visits to physicians is to receive treatment for a health problem and, as such, they are goal-oriented encounters. Studies of general practice medical encounters have shown that they are organised in phases, where activities or tasks are done in a particular order (Byrne and Long 1976, Robinson 2003, Heritage and Maynard 2006). Physicians and patients mutually enter into an interactional project consisting of a progression through several activities: opening the consultation, establishing a medical problem as the reason for the visit, gathering information (history taking and/or physical exam), delivering a diagnosis, recommending treatment, and closing the consultation (Heritage and Maynard 2006, Robinson 2003). These activities are oriented to by patients and physicians, and inform their understanding and production of communicative behaviours: in other words, the participants understand individual courses of action using this broader structural organisation as a resource. Although this has been most frequently found to be the case in acute primary care encounters, others (e.g. Gill and Maynard 2006) have found that physicians and patients in non-acute visits orient towards this structure as well. Our data, which were gathered in a specialty care setting, exhibit this organisation. We therefore consider patient compliments in light of the activities and local sequential environment in which they occur, and contend that physicians’ understanding of compliments is informed by their placement either before or after the activity of treatment recommendation (i.e. before or after the ‘goal’ of the encounter has been achieved). This paper is therefore structured to first describe compliments that are offered after treatment recommendations, followed by those that precede them. We also consider the salient design features of each compliment to see how these contribute to what patients are doing with their compliments and what they invite in return, and to show how participants’ institutional identities as surgeons and as patients are relevant. Finally, we show that patients can use both compliment placement and design to pursue institutional ends, including desired treatments.

Compliments offered after treatment recommendations

Patients may offer compliments in the phase of the visit after surgeons have made (and patients have accepted) recommendations about how to treat their medical problems. This is an environment where they may be engaging in small talk and preparing to close the encounter, or may be discussing some aspect of the recommended treatment. For example, the compliment in Extract 1 occurs near the end of the consultation, after a decision about how to proceed with the patient’s treatment has been proposed and accepted, and during an extended spate of topicalised small talk (Hudak and Maynard 2007). The surgeon and patient have been discussing a teenager, ‘Bob’, whom they both know and on whom the surgeon has also operated. The patient assesses Bob as ‘a whole lot better’ and compliments the surgeon on doing a ‘great job’ (line 26). The surgeon treats this as praise of his performance, and reacts to the compliment in much the same way as participants in ordinary talk respond when they receive praise (Pomerantz 1978): he accepts the compliment while avoiding self-praise. However, he does maintain an orientation to his institutional status as an expert rather than fully reassigning the praise and thus without completely disclaiming the expertise with which the patient has credited him.

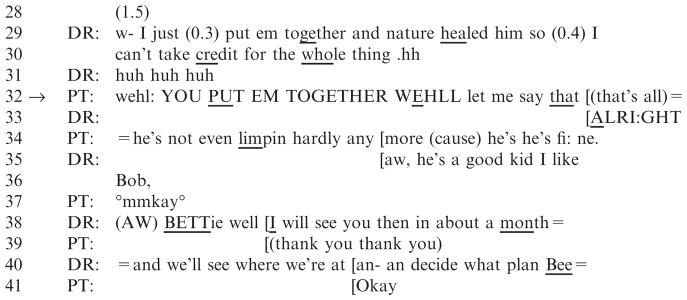

Extract 1.

10110008 (12:36.1-13:40.0)

Touched off by the surgeon’s reference to the local football team (line 1), the patient asks him whether he operated on one of the players: ‘did you put Bob T__________ back together by any chance’ (lines 3 and 5). An extended sequence of small talk follows, concerning Bob’s difficult social situation (lines 8–18) and future potential prospects (lines 18–23). At line 24, the patient’s ‘oh wehll’ prefaced positive assessment (‘oh wehll he’s a whole lot better than he wa:s’) is designed to counter the pessimistic stance displayed by the surgeon in lines 21 and 23. It provides a basis for her to compliment the surgeon on his role in Bob’s improvement, and thereby give him credit for what he has done (‘(yeah) yeah you did a great job’, line 26). In overlap with the compliment, the surgeon agrees with her assessment of Bob’s situation (°oh yeah yeah°, line 27).

There follows a 1.5 second silence (line 28). After this delay, the surgeon responds to the compliment by lessening his role in the patient’s healing and reassigning the credit to ‘nature’ (‘w- I just (0.3) put em together and nature healed him so (0.4) I can’t take credit for the whole thing .hh’, lines 29–30). As a referent shift, this portion of his response is largely consistent with compliment responses in everyday talk (Pomerantz 1978) (we refer to such responses subsequently in this paper as ‘baseline’ responses). The patient then offers another version of her original compliment, one that specially underscores the surgeon’s role in the patient’s healing (‘wehl: YOU PUT EM TOGETHER WEHLL let me say that [(that’s all)’, line 32). By acquiescing with ‘ALRIGHT’ at line 33, the surgeon departs from the baseline compliment response format. He accepts her positive assessment, thereby reaffirming his institutional status as a medical expert. This modification of the baseline response format suggests that even though he has concluded his evaluation of the patient, he is still orienting to the type of encounter in which they are engaging and to the relevance of their respective institutional identities: he will be her surgeon.

The patient then provides evidence of the doctor’s ‘great’ work by reporting that Bob is not even limpin hardly any more (cause) he’s he’s fi: ne’ (line 34). In a preclosing move, the surgeon offers a figurative expression (Drew and Holt 1991), a positive assessment of Bob’s character (lines 35–36). The patient minimally acknowledges this with ‘mmkay’ (line 37) and the surgeon then moves to close the visit by making arrangements for the patient’s next appointment (lines 38–40).

In summary, the patient designs and places the compliment in a way that bids for it to be heard as a positive assessment of the surgeon’s performance in regard to a prior surgery and as an optimistic counter to his pessimistic stance. She places it after the treatment recommendation, in the context of small talk on a topic unrelated to her own medical problem, and she designs it as a specific assessment of the surgeon’s performance in a case unrelated to her own. The surgeon takes the compliment as praise. He provides a modified baseline response, disclaiming some credit for the other patient’s successful healing but preserving the expertise accorded to him as a surgeon. Thus, although the surgeon maintains an orientation to the overall purpose of this encounter, the praise comes off as ‘unmotivated’ in regard to the patient’s own medical treatment.

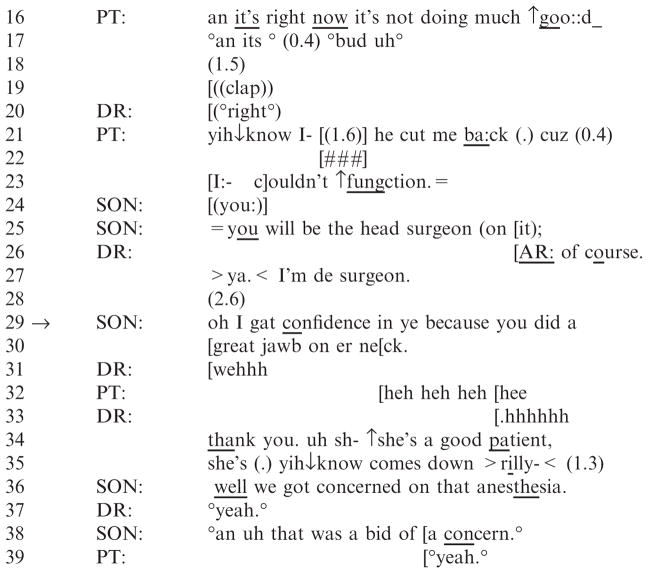

Our second example of a compliment in the post-treatment recommendation phase occurs in a visit with a different patient, after the surgeon has recommended treatment (back surgery) for the patient’s sciatica. This patient, who is accompanied by her adult son (Ken), has had multiple orthopaedic surgeries, including surgery on her neck and back performed by this surgeon. It is the son who compliments the surgeon. As in Extract 1, this compliment is also directed toward the surgeon’s past performance; here it serves to rectify a misunderstanding in the preceding talk and reassure the surgeon.

Prior to the talk shown in this extract, the surgeon detailed the surgical procedure he would be performing on the patient’s back. The patient and her son questioned him about aspects of the surgery and the projected recovery time. The son raised a concern about the anesthetic his mother had been given in a previous surgery (a knee replacement): she had difficulty coming out of it. The mother reported that she was, in fact, more concerned about the anesthetic than the upcoming surgery itself. The surgeon responded to these concerns by proposing that they should communicate with the anesthesiologist before the upcoming surgery.

The surgeon reaffirms the patient’s need for surgery (line 1, below) and Ken seeks confirmation that the surgery will benefit his mother by eliminating the number of medications she takes (lines 2–3, 6). The surgeon strongly confirms this (lines 7–8). The mother aligns with the proposal that surgery is necessary, complaining that her medication, at the dosage she can tolerate, is not helping (lines 16, 21, 23). In this environment of complaints about her situation, Ken seeks confirmation about the surgeon’s role in the operation: ‘you will be the head surgeon (on it)’ (line 25). When the surgeon responds defensively, Ken compliments his prior work.

The surgeon’s three-part confirmation at lines 26 and 27 (‘AR: of course. >ya.< I’m de surgeon’) has a defensive quality, in that it treats his role as head surgeon as something that should have been known or assumed2. Thus, it treats the son as having questioned, perhaps inappropriately, his role as head of the surgical team. The son treats this as a misunderstanding and corrects it: following a silence (line 28), he compliments the surgeon by invoking his prior, successful work on his mother’s neck. He reports, ‘oh I gat confidence in ye because you did a great jawb on er neck’. This appears to be a bid to reassure the surgeon that he was not casting doubt on his competence or questioning his role in the upcoming surgery.

The surgeon provides a modified baseline response to the compliment, as did the surgeon in Extract 1. He accepts it (‘thank you’, line 34), thus showing appreciation for the praise and preserving the expertise the son accorded him. He then gives credit to the mother for being a ‘good patient’ who recovers well (‘she’s (.) yih↓know comes down>rilly-<’, line 35), reassigning some of the credit to her. The matter would appear to be closed. However, the referent shift is apparently problematic for Ken. In lines 36 and 38 he retopicalises their concerns about this very issue, reminding the surgeon about the mother’s problems with anesthesia after the last surgery. He treats the surgeon as insufficiently attentive to his own role in making sure the patient came out of anesthesia without problems.

In these extracts the compliments functioned to praise their surgeon-recipients in environments where the surgeon’s efficacy or role was possibly called into question, either by the surgeon himself (Extract 1) or by the patient’s son (Extract 2). The surgeons took the compliments as praise, using the baseline response described by Pomerantz (1978) with a modification that preserved their medical expertise. This suggests that, compared to compliment recipients in non-institutional contexts, surgeons are orienting towards an additional, identity-specific, response dilemma that inheres in medical encounters: if they avoid self-praise entirely, they may risk discrediting themselves professionally in front of patients who are relying on their professional expertise. Our primary point is that although the compliments in Extracts 1 and 2 do more interactional work than simply offering praise, and although physicians orient towards their institutional status by preserving some credit for their actions deemed praiseworthy, the participants do not orient towards them as consequential for medical decision making.

Extract 2.

10770002 (7.38-8.24)

Compliments offered before treatment recommendations

Placement during visit openings

Patients may compliment surgeons in the opening moments of medical encounters, before the surgeons have evaluated the patients or made treatment recommendations. This is a local environment where activities may include not only greetings, but also patient accounts for ‘how I came to be here’. As we will show, compliments can figure in these accounts or can be part of an exchange of pleasantries during the greeting exchange. Thus, to the extent that the compliments are tied to aspects of the opening sequences, they have a local rationale that grounds their deployment. Patients may use compliments in the opening sequences to establish their general expectations for excellent medical care, though not necessarily particular modes of treatment. And as we will show, patients may later re-invoke these compliments in subsequent efforts to exert pressure for particular types of treatments.

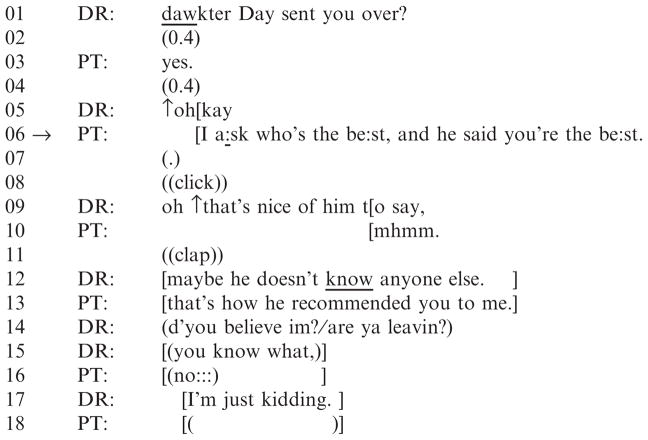

In the moments just prior to Extract 3, the surgeon and patient greeted each other and identified themselves. In line 1, the surgeon asks the patient if ‘Dr. Day’ is the identity of the referring physician. The patient confirms, and reports a complimentary assessment Dr. Day made of the present surgeon: he is ‘the best’ (line 6).

Extract 3.

10890009 (0:28-0.39)

This compliment emerges as part of the patient’s account for the present visit: she explains that she asked for ‘the best’ surgeon (line 6), and that this one was named. Thus, at the very beginning of the visit she casts herself as a person with high expectations who actively seeks out superlative care. Note that the patient indicates that the actual source of the compliment is the other doctor. In this aspect of its design, the footing the patient adopts (Goffman 1981), the compliment differs from the two we have considered thus far; in Extracts 1 and 2, the complimenters drew upon their own knowledge of the surgeons’ expertise and committed to positive stances of their own in regard to it. In the present case, the patient does not draw upon first-hand knowledge to take a stance of her own (this is her first consultation with this surgeon). Rather, via the compliment she shows that she has arrived at the consultation with both a desire for ‘the best’ care and an expectation that she will receive it (as a result of the referring physician’s recommendation). By designing the compliment in this way and placing it in the opening moments in the visit, the patient may put subtle pressure on the surgeon to meet these general expectations.

The surgeon’s response is consistent with the modified baseline response pattern shown in Extracts 1 and 2, suggesting that he is orienting towards the compliment as praise. In line 9, he offers a positive assessment of the referring doctor’s remark (‘oh ↑that’s nice of him to say’), thus gratefully acknowledging the other doctor’s assessment of him but not agreeing with the compliment per se. Next, the surgeon orients towards the characterisation of him as ‘the best’, first by disagreeing with it (playfully raising the possibility that he is the best by default – i.e. because he is the only one known to this referring doctor; line 12). In so doing, he uses humour to bring into question and therefore deflect the referring physician’s positive characterisation. Then he modifies this baseline response by relenting on the inference that he is only best by default (‘I’m just kidding’, line 17). This works to preserve some of the expertise accorded to him. Thus, the surgeon orients to his institutional identity and the nature of this encounter, one in which the patient is seeking the benefits of his professional expertise.

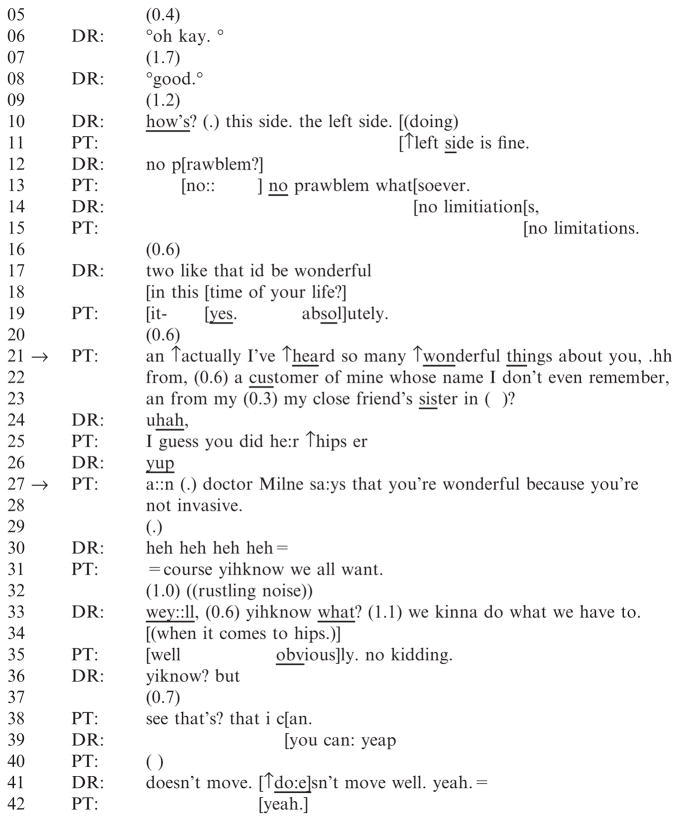

In Extract 4, the patient also offers a compliment in the opening moments of the visit and adopts a footing (Goffman 1981) where she is expressing others’ views rather than her own. She reports that she has ‘heard wonderful things’ about the surgeon from ‘lots of people’, a compliment that she will re-invoke and elaborate upon later in the visit (in Extract 5) to angle for a particular form of treatment. Here, the surgeon treats her remark as praise, using the modified baseline response form described above. However, he initially has some difficulties responding to the compliment, the nature of which suggests trouble with the compliment’s placement in this sequential environment.

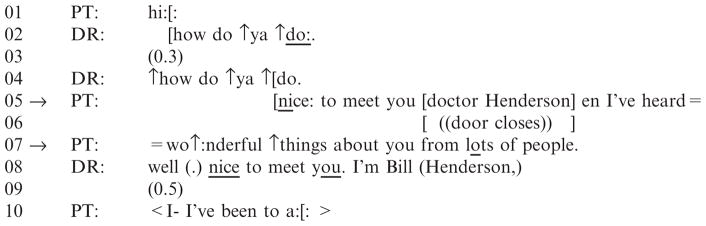

Extract 4.

11400004 (0:33-1.07)

Extract 5.

1140004 (4:55-5:44)

Following an exchange of greetings (lines 1–4), the patient offers a pleasantry (‘nice: to meet you doctor Henderson’) to which she appends a compliment (‘en I’ve heard wo↑:nderful ↑things about you from lots of people’, lines 5 and 7). By reporting having heard positive assessments of him from multiple third parties, she suggests that she has arrived with high expectations for the care she will receive; but as in Extract 3, she does not reveal a stance of her own. Note that in contrast to Extract 3, the patient here provides no account for passing along this compliment at this moment in the conversation, and in contrast to Extracts 1 and 2, the compliment does not address a problem with the immediately preceding talk (which would also serve as an account for its presence). The patient casts herself as the unmotivated recipient of several positive comments about this surgeon and leaves open the question of why she may be complimenting him at this precise moment in the encounter.

The surgeon treats responding to the compliment portion of her utterance as a problematic matter. With the ‘well’ preface he projects that his response will deviate from what the preceding turn invited and then he attends to completing the exchange of pleasantries and producing an introduction before responding to the compliment. He responds to the first component of the patient’s turn (‘nice: to meet you doctor Henderson’) with ‘well (.) nice to meet you.’ and he introduces himself: ‘I’m Bill (Henderson)’ (line 8). Note that he had already received evidence that the patient was aware of his identity: she used his name and passed along compliments about him in line 5 and 7. The surgeon’s redundant self-introduction at this moment further delays the production of a compliment-response.

After an additional delay (line 9), the patient begins an utterance but the surgeon interrupts with a response to the compliment: ‘I know ↑people’s ↑hips:::’ (line 11). Consistent with the baseline response format, he downgrades the terms of the compliment, suggesting that ‘lesser amounts of credit are justified’ (Pomerantz 1978: 98). However, he modifies this by retaining credit for an area of medical expertise, ‘people’s hips’. This move allows him to avoid self-praise in a general sense, without downgrading his professional skills – expertise for which the patient is consulting him. He laughs, in a potential attempt to treat the discrepancy between the characterisation of himself as ‘generally wonderful’ and his own characterisation as someone who ‘knows hips’ as laughable (or perhaps as ‘delicate’ in that he has problematised the patient’s characterisation of him (see Haakana 2001)). The patient does not join in this laughter but rather, moves into the problem presentation phase of the visit (lines 13–14).

In summary, the compliments in Extracts 3 and 4 are designed and placed to show patients’ expectations for excellent care, not simply to offer praise. The surgeon in Extract 3 treats this as unproblematic and provides a modified baseline response. However, there is some evidence that the surgeon in Extract 4 orients towards the compliment as problematic, above and beyond having to handle the special constraints that may be inherent when medical professionals are complimented during medical encounters. The surgeon treats the positioning of the compliment in this local sequential environment as troublesome – perhaps owing to the fact that (1) the patient did not provide a verbal account for the compliment’s presence (compare to ‘I a:sk who’s the be:st’, Extract 3); or (2) that she did not position it in a sequential location that would otherwise indicate what the compliment ‘is doing here’ (e.g. countering a pessimistic stance, as in Extract 1). This is perhaps a classic example of the ‘red flag’ phenomenon described in the introduction where, for no apparent reason, a patient gives a compliment. In response, the surgeon prioritises the completion of the other actions before responding to the compliment. Later in this consultation, the patient re-invokes the compliment and adds crucial design elements to angle for a particular type of treatment, non-invasive surgery. We turn to that portion of the visit now, and then consider another example of a compliment that presses for a particular approach to treatment.

Placement during the information-gathering phase: pressing for treatment

The final compliments we consider (Extracts 5 and 6) occur in local environments where the official business of the medical encounters is fully underway, but where the surgeons have not yet made treatment recommendations. The surgeons are gathering information from the patients about their health problems. In both cases, the compliments angle for particular ways of treating the problems under consideration. The surgeons respond by resisting these compliments, and thus resist being pressured in regard to the patients’ treatment.

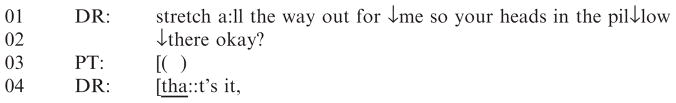

Extract 6.

10770002 (1:29-4.33)

Extract 5 occurs in the same visit that began in Extract 3; it occurs approximately five minutes into the consultation, during the physical exam. The patient has a problem with her right hip. The surgeon has just begun the exam, starting with the patient’s unaffected (left) hip, and has not yet provided a treatment recommendation. However, when he indicates that he may be positively inclined toward surgery, the patient re-invokes her earlier compliment (from Extract 4, lines 5 and 7) adding important design elements that place non-invasive treatment in a positive light and bid for the surgeon to consider this treatment modality. The surgeon rejects the terms of the compliment, and thus resists accepting the implication that non-invasive treatment3 would be appropriate for her.

After the patient lies on the examination table, the surgeon asks her to assess the condition of her left hip (lines 10, 12, 14). The patient indicates that it is fine (lines 11, 13, 15). The surgeon then solicits the patient’s perspective about treating her right hip, with ‘two like that id be wonderful in this time of your life?’ (lines 17–18). This is delivered as a candidate perspective for her to confirm. In addition to conveying a candidate version of her perspective, this may be a way to show his own positive disposition toward surgery.

At the first possible completion point, in overlap with the second component of the surgeon’s turn, the patient provides an enthusiastic confirmation (‘yes. absolutely.’, line 19). She then projects an informing with ‘actually’ (Clift 2001) and re-invokes – in an upgraded fashion – the compliment she gave during the opening moments of the visit (see Extract 4): ‘I’ve ↑heard so many ↑wonderful things about you’ (line 21). By positioning the compliment in this sequential environment (where the issue of treatment has emerged and where signs may point to his positive inclination toward surgery), she provides for the surgeon to hear the compliment as a positive assessment of his treatment skills. As in Extract 4, she expresses this as others’ positive views, but here she reveals the sources: one is ‘a customer’ whose name she claims not to remember, and a second is another unnamed acquaintance, ‘my close friend’s sister’ (lines 22–23). By downgrading the kind of relationship she had with the tellers (professional and not well-acquainted) she upgrades the compliment; that is, even non-intimates are mentioning how ‘wonderful’ the surgeon is. Additionally she shares an important detail about the second source: the surgeon ‘did he:r ↑hips’ (line 25). In this way she builds a connection to her own case by revealing that at least one (if not two) acquaintances whom he treated for the same condition she has, hip problems, were so happy with their care they told her about it.

She continues, identifying a third compliment-source, this time by name (line 27). It is her internist, ‘Dr. Milne’. Here she adds another component to the compliment’s design, the reason for the praise: ‘you’re not invasive’. In this way, she puts a particular type of treatment (non-invasive) in a positive light. This also places new response constraints on the surgeon. If he were to accept the compliment he would also be implicitly accepting the characteristic that has been ascribed to him (‘non-invasiveness’). This could then be heard as a de facto acceptance of a non-invasive approach to all surgeries, including this patient’s surgery. However, to reject the compliment could entail rejecting the opinion of a medical colleague and calling this colleague’s knowledge into question.

The surgeon resists. He chuckles (line 30), not only delaying a response but treating the action as delicate (Haakana 2001). The patient evidently takes this as an indication that he recognised what she is angling for with her compliment. At line 31, she displays recognition that she now knows that he knows what she was working towards, framing it as an admission (‘=course yihknow we all want’). At the same time, she suggests that a preference for non-invasive treatment is normative, one that ‘all’ patients have.

After another delay (silence; an extended ‘wey::ll’, which projects that his response will be nonconforming; a pause; and ‘yihknow what?’, lines 32–33) the surgeon rejects the terms of the compliment. He reports that the type of surgery patients have is dictated by their condition: ‘we kinna do what we have to. (when it comes to hips.)’ (lines 33–34). Thus, he deftly resists weighing in on a non-invasive approach for this patient without committing to any particular treatment recommendation. Note that by using ‘we’, he frames this as an approach that is used by other orthopaedic surgeons and thus casts it as an institutional rather than personal stance. The patient backs down sharply, portraying it as something she already knew (‘well obviously. no kidding.’, line 35). They then resume the physical exam.

To summarise, in Extract 5, the patient re-invokes her initial compliment while her condition is still under consideration, modifying the design to angle for a particular mode of treatment. By rejecting the terms upon which the new compliment was based, that he is non-invasive, the surgeon resists being pressured in regard to the patient’s treatment. He portrays the type of treatment surgeons provide as a function of the particular medical problem at hand – that is, dictated by that problem, rather than as a matter of choice. Yet, the way he handles the compliment still allows for the contingency that non-invasive surgery may be an option for this patient.

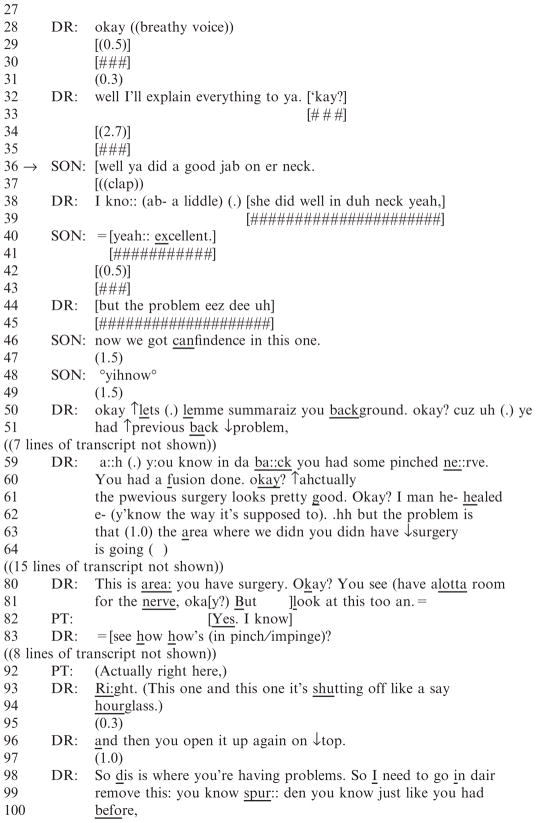

Extract 6 occurs in the same visit as Extract 2. As previously noted, this patient has had multiple orthopaedic surgeries, including prior surgery on her neck and a lumbar spine procedure that released pinched nerves. Both surgeries were performed by this particular surgeon. Her last visit to him (two weeks before) was for sciatica in her left leg, a symptom that is typically produced by the compression of lumbar nerves. At that time, the surgeon recommended medication to control the pain and indicated that she should return to him if her condition worsened. Her visit today is earlier than anticipated because, according to the patient, the medication was ineffective. As they discuss this, her son (Ken) uses a compliment to angle for a more aggressive approach to his mother’s sciatica.

Just prior to line 1, the patient accounted for the timing of her visit by claiming that her medication for the nerve pain was ‘not doing anything’ and that she could not function. The surgeon asked her about the location of the pain, and after responding that it is just on her left side she underscored how much it is affecting her daily life, claiming ‘there’s times where I could barely walk’ and that the pain can occur even when she is sitting down. The surgeon acknowledged her expressions of suffering. He continues gathering information about the pain (line 1) and the patient works to legitimise her earlier-than-anticipated visit and press for a new type of intervention.

The surgeon asks the patient whether her back or leg pain is worse and she indicates that her leg is worse, re-emphasising that nothing has helped ease it (‘↑nothings doin anything’, line 9), and that the pain is even set off by commonplace activities such as showering and the touch of her clothing (lines 14, 16, 18). She concludes by requesting a re-evaluation: ‘so yelemme know: hhh (0.8) what’s ↑wha::t (an what) we’re gonna do’ (lines 18 and 20). The surgeon does not take up this request immediately. He provides a receipt token (‘okay’ line 22) and there ensues an 8.5 second silence, where shuffling sounds suggest that he is going through records.4 The patient then reports that her son, ‘Ken’, was not present at her last visit (line 25). This may serve as an account for the treatment advice she did receive, as it suggests that Ken’s absence was somehow important in regard to her care. The surgeon provides another acknowledgment, ‘okay’, and there is silence before he says ‘well I’ll explain everything to ya.’ (line 32). The surgeon thus treats the importance of Ken’s absence at the last visit as a problem of non-shared knowledge, and projects an upcoming explanation. There is more silence (line 34).

It is here that Ken compliments the surgeon for his performance on his mother’s prior neck surgery: ‘well ya did a good jab on er neck.’ (line 36). With this compliment, the son pursues a new approach to the mother’s treatment. That is, by coming in at this moment and praising the mother’s prior treatment (which involved surgical intervention and resulted in a positive outcome), he augments her call for different – and possibly more aggressive – treatment of the sciatica. Features of the compliment’s design provide for this hearing; it has a well-preface, which projects that he will take a contrastive stance, and it specifically compliments the surgeon’s work on the mother’s neck. Using these features, Ken implicitly contrasts the surgeon’s prior (successful) performance on the mother’s neck with his current performance in regard to the sciatica. In addition, the footing (Goffman 1981) that Ken adopts portrays this as his own point of view. In an environment where Ken’s knowledge of his mother’s problem has been made relevant, by offering this compliment, he claims some epistemic authority in the matter and grounds his ability to make this contrast.

The surgeon treats the compliment as problematic. Initially, he provides a baseline compliment response: he agrees with ‘I kno::’ and then credits the mother for doing ‘well’ (line 38). Ken agrees, upgrading the evaluative term for his mother’s results from ‘well’ to ‘excellent’ (line 40). However, the surgeon then begins to work to claim more credit than he has been given for the way he has treated the patient’s pinched nerves. In line 44, he projects resistance to the compliment’s implications (‘but the problem eez dee uh’). Ken continues, adding another component to the compliment: ‘now we got canfindence in this one’ (line 46). This upgrades his bid for the surgeon to approach the pinched nerves as he did the neck. The surgeon does not respond, even after a silence and the son’s ‘yihnow’, which invites uptake (lines 47–48).

At line 50, the surgeon works to resist the suggestion implicit in the compliment – that he has provided suboptimal care for the patient’s sciatica – by building a defence of the way he has handled the problem in the past. He refers to her history of previous back problems, and after a brief digression where Ken jokes that they should get a ‘discount’ for surgery (not shown here), he reminds them that the patient had previous surgery for pinched nerves and that this was successful (lines 59–62). But he alludes to ‘a problem’ with the area where they did not operate (lines 62–63). Note that his self-repair (from ‘we didn’ to ‘you didn have surgery’) takes some of the responsibility for what areas were treated off the surgical team and thus treats this matter as problematic.

A few turns later, he refers to the area on her back where she was treated, asserting that the nerve is not pinched in the area he operated on (line 80). He contrasts this to the untreated area: ‘bu look at this too an. see how how’s (in pinch/impinge)?’ (lines 81 and 83). The patient agrees and claims her own independent knowledge of the problem (line 82) and access to the observations (line 92). The surgeon continues reporting that some nerves remain compressed (‘(This one and this one it’s shutting off like a say hourglass.)’, lines 93–94). Attributing her ‘problems’ to this area, he provides his treatment recommendation: more surgery, ‘just like you had before’ (lines 99–100).

In summary, the patient’s son works to affect the surgeon’s treatment decision by complimenting him on his treatment of his mother’s neck, thereby implying that the treatment of her sciatica has been inadequate and that a new, more aggressive, approach should be taken. In response, the surgeon defends himself, underscoring the effectiveness of his prior treatment. He recommends more surgery, but manages this so that he is not ‘relenting’ to the son’s pressure for surgery as much as proposing to complete the process of surgically releasing the patient’s pinched nerves.

What we wish to highlight with the preceding extracts (3–6) is that not all compliments produced before treatment recommendations portend or suggest an agenda. However, the fact that some compliments do precede an overt patient agenda (e.g. Extract 4) and are thus retrospectively hearable as having hinted at that agenda, may render any compliment given prior to treatment as potentially ‘suspicious’. Given that medical encounters are goal-oriented, and that the goal has generally not been accomplished until a treatment recommendation for the patient’s problem has been made, compliments given before the treatment recommendation may be particularly prone to interpretive ambiguity and may alert surgeons to attend to the possible institutional import of a social activity like complimenting.

Discussion

Our goal was to explore why physicians may be suspicious of at least some patient compliments. By using conversation analysis to understand the interactional function of patient compliments in their sequential context in actual patient-surgeon interactions, we have shown how compliments do various kinds of interactional work: some are oriented to by surgeons as purposeful and clearly angling for particular treatments, while others are either ambiguous at the time of their offering with respect to an institutional agenda, or best characterised as praise which is not consequential for the patients’ care. As a whole, this work provides insight into why physicians may be suspicious of compliments, and sheds light on how patients may use a compliment as a resource to participate in medical decision making.

Both a compliment’s placement and design are relevant features to analyse, in order to understand how surgeons may orient to this ordinary social activity as a pursuit of an institutional end as a patient’s efforts to affect decision making by angling for a desired treatment. We showed how compliments produced after treatment recommendations were not designed to angle for particular treatments and how these compliments were responded to unproblematically by surgeons. In contrast, we also showed how compliments can be used before treatment recommendations to pursue institutional goals, particular modes of treatment, and how these were treated as problematic in some cases: surgeons resisted these compliments. For example, we described how surgeons displayed recognition that some compliments were not just ‘nice things’ that were being said about them but that they contained characterisations that, if accepted or rejected, would have particular implications. By resisting these compliments, surgeons show that what the compliment is doing is problematic for them in more than an everyday, baseline way. It is reasonable to presume that it may be experienced as disingenuous, perhaps even manipulative, to a surgeon when a patient uses a compliment to get his or her wishes for treatment on the table. When actions other than complimenting are packaged as compliments, physicians are in the position of needing to decipher what precisely it is the patient is doing with that compliment in real time as talk proceeds. While this is generally true for conversation (recipients need to determine what action is being done by any given utterance and what is required from them in return), it could be that when such patient initiatives regarding their medical care are clothed as complimentary remarks, surgeons feel particularly jarred by this contrast.

We also analysed compliments that occur before treatment recommendations, but which do not, by design, clearly angle for particular treatments. These compliments are produced in the opening phase of the interactions, an environment that endows them with potential ambiguity as to their institutional import. Following one such compliment (Extract 4), the patient subsequently produces another compliment – in fact she essentially re-invokes her earlier compliment – in order to angle for a particular treatment (Extract 5). This retrospectively allows the patient’s initial compliment to be hearable as hinting at or foreshadowing an agenda. However, not all compliments produced prior to treatment recommendations hint at specific patient agendas, as the compliment provided at the beginning of the consultation in Extract 3 shows.

There is a ‘medicalness’ or institutional import to many patient compliments in the sense that they often assess surgeons’ expertise or skills. Some of these are problematic for surgeons in the same way as compliments in everyday talk; their responses display features found in compliment-responses in everyday talk (Pomerantz 1978). However, even when responding to a compliment in a baseline way, surgeons orient towards characterisations contained in them that have institutional import, modifying their responses so as to preserve/reproduce their status as experts in the medical context. For example, the general characterisation of being ‘wonderful’ in the compliment ‘I’ve heard wo↑:nderful ↑things about you’ (Extract 4) is heard by the surgeon as institutionally relevant: as an assessment of his medical expertise rather than any other potentially relevant way in which he may have been considered wonderful. In his response, the surgeon reveals this orientation but also narrows his range of expertise by reporting ‘I know ↑people’s ↑hips:::’ – a downgrade (and therefore a baseline compliment response) but one that is modified to display an orientation to his status as an expert whose advice is being sought. In other words, the surgeon scales back the compliment but does not completely disclaim his expertise.

An appreciation for patient compliments contributes significantly to the understanding of interactions between patients and medical professionals with regard to treatment decisions. In this respect, this work reveals a practice patients use to participate in medical decision making and how physicians respond to those attempts. In other words, these findings reveal something of the dynamic that is involved when patients come to a consultation with an idea of what treatment they would prefer and physicians do not necessarily concur. For patients, a compliment can be a resource that allows their preferences or wishes to be known in situations where they do not feel entitled to express them directly (or to overtly participate in the decision-making process). The problem is not with the compliment but with the underlying interactional environment in which patients feel constrained in expressing their wishes and desires. If the types of contributions patients feel entitled to make are limited, things like compliments – an apparently safe kind of action for patients – can be used as resources to get issues on the table. Viewed from this perspective, this paper offers insight into patients’ use of compliments in medical interaction and may allow surgeons an alternate understanding of them: rather than treating compliments negatively as ‘red flags’ to be regarded with suspicion, surgeons could examine compliments for what they may reveal about patient preferences or desires in relation to their healthcare. Surgeons should be alert to the potential institutional import of compliments and to the ways they might create opportunities to explore needs, like expectations or preferences, that patients may be less able or willing to articulate more directly. Explorations and discussions of this nature could be of great benefit to patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided in part by grants from the National Institute of Aging (R01 AGO18781) and the Agency for Health Care Research & Quality (R03 HSO15579-01A1). The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the above organisations is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

The 59 cases in the data set were drawn from 282 visits that were in turn selected from a larger study of 886 on the basis of the presence of a discussion of an invasive orthopaedic procedure (see Levinson et al. 2008).

The patient’s reference to ‘he’ in line 21 is ambiguous, but is likely to refer to the present surgeon. The surgeon’s defensive posture may stem from this hearing (i.e. Ken’s question might seem to question his role in her current care, given that his mother ‘couldn’t function’ on her previous regimen).

Later in this visit, we find out that it is not so much that the surgeon is non-invasive in his surgery but rather that he uses a surgical approach for the patient’s condition that involves a single incision, and this is perhaps less invasive than traditional approaches.

There is ongoing, concurrent activity in the course of the interaction (see # at lines 8, 10, 13, etc.). The surgeon’s utterances in these locations suggest he is shuffling through the patient’s chart and radiology documents such as x-rays, MRI results and so on.

References

- Brown P, Levinson S. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne PS, Long B. Doctors Talking to Patients: a Study of the Verbal Behaviours of Doctors in the Consultation. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie D. How to Win Friends and Influence People. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Clayman SE, Gill VT. Conversation analysis. In: Bryman A, Hardy M, editors. Handbook of Data Analysis. London: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clift R. Meaning in interaction: the case of ‘actually’. Language. 2001;77:245–91. [Google Scholar]

- Drew P, Holt E. Figures of speech: figurative expressions and the management of topic transition in conversation. Language in Society. 1998;27:495–522. [Google Scholar]

- Gill V, Halkowski T, Roberts F. Accomplishing a request without making one: a single case analysis of a primary care visit. Text. 2001;21:55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gill V. Patient ‘demand’ for medical interventions: exerting pressure for an offer in a primary care clinic visit. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2005;38:451–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gill V, Maynard D. Explaining illness: patients’ proposals and physicians’ responses. In: Heritage J, Maynard D, editors. Communication in Medical Care: Interaction between Primary Care Physicians and Patients. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Relations in Public. New York: Harper and Row; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Golato A. Compliments and Compliment Responses: Grammatical Structure and Sequential Organisation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2005. [Studies in Discourse and Grammar 15] [Google Scholar]

- Haakana M. Laughter as a patient’s resource: dealing with delicate aspects of medical interaction. Text. 2001;21:187–219. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RK. Sex-based differences in compliment behavior. Language in Society. 1989;19:201–24. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J. Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in Medical Care: Interaction Between Primary Care Physicians and Patients. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs P. The medium is the message: politeness strategies in men’s and women’s voice mail messages. Journal of Pragmatics. 2003;35:243–62. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J. Paying compliments: a sex preferential politeness strategy. Journal of Pragmatics. 1988;12:445–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hudak PL, Maynard DW. Defining the domain of ‘topical small talk’ in clinical settings. Toronto, Canada: Department of Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Hudak P, Feldman J, Frankel R, Kuby A, Bereknyei S, Braddock C. Racial disparities in communication between orthopaedic surgeons and patients. Medical Care. 2008;46:410–16. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815f5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard D. Praising versus Blaming the Messenger: Moral Issues in Deliveries of Good and Bad News. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 1998;31:359–395. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch J, Snook D, Weiner BK. Differential diagnosis of low back pain. In: Tollison C, Satterthwaite J, Tollison J, editors. Practical Pain Management. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz A. Compliment responses: notes on the cooperation of multiple constraints. In: Schenkein J, editor. Studies in the Organisation of Conversational Interaction. New York: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients’ participation. Health Communication. 2003;15:27–57. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H. Notes on methodology. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H. In: Lectures on Conversation. Jefferson G, editor. I and II. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff E. Sequence Organization in Interaction: a Primer in Conversation Analysis. Los Angeles: University of California; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wall MD, Amendt JH, Kleckner T, du Ree B. Therapeutic compliments: setting the stage for successful therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1989;15:159–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1989.tb00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]