Summary

Glial cells are crucial regulators of synapse formation, elimination, and plasticity [1, 2]. In vitro studies have begun to identify glial-derived synaptogenic factors [1], but neuronglia signaling events during synapse formation in vivo remain poorly defined. The coordinated development of pre- and postsynaptic compartments at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) depends on a muscle-secreted retrograde signal, the TGF-β/BMP Glass bottom boat (Gbb) [3, 4]. Muscle-derived Gbb activates the TGF-β receptors Wishful thinking (Wit) and either Saxophone (Sax) or Thick veins (Tkv) in motor neurons [3, 4]. This induces phosphorylation of Mad (P-Mad) in motor neurons, its translocation into the nucleus with a co-Smad, and activation of transcriptional programs controlling presynaptic bouton growth [5]. Here we show that NMJ glia release the TGF-β ligand Maverick (Mav), which likely activates the muscle activin-type receptor Punt to potently modulate Gbb-dependent retrograde signaling and synaptic growth. Loss of glial Mav results in strikingly reduced P-Mad at NMJs, decreased Gbb transcription in muscle, and in turn reduced muscle-to-motor neuron retrograde TGF-β/BMP signaling. We propose that by controlling Gbb release from muscle, glial cells fine tune the ability of motor neurons to extend new synaptic boutons in correlation to muscle growth. Our work identifies a novel glia-derived synaptogenic factor by which glia modulate synapse formation in vivo.

Results and Discussion

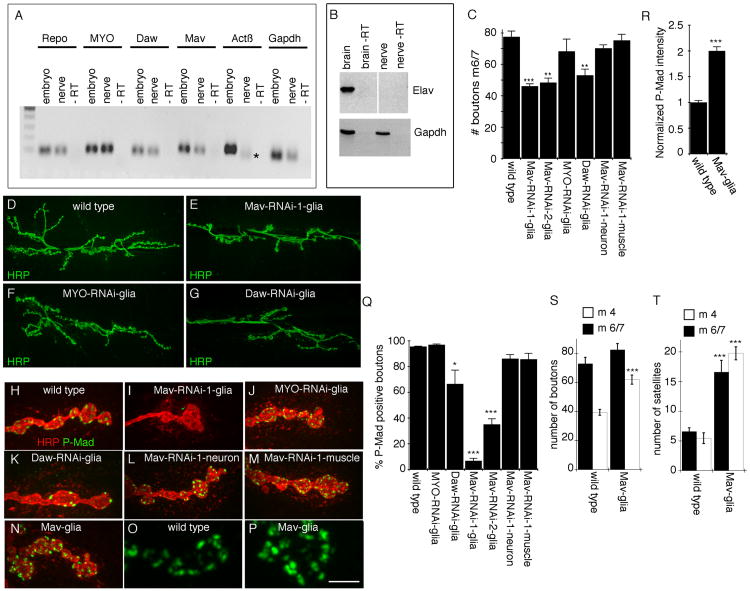

A TGF-β Signaling Pathway Is Activated by Peripheral Glia during Synapse Development

Given the prominent role of glia and TGF-β signaling during synaptic bouton formation at the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ), we sought to determine whether ligands of the TGF-β superfamily are expressed in peripheral glia at the larval stage by real-time PCR (Figures 1A and 1B). For this analysis, we isolated total RNA from segmental nerves in which the only cell bodies were peripheral glia and no neuronal RNAs were detected (Figure 1B). This analysis revealed the presence of several transcripts for TGF-β ligands in glia, including Myoglianin (MYO), Dawdle (Daw), and Maverick (Mav) (Figure 1A). In contrast, Activin β (Actβ) transcripts were not detected in nerves (Figure 1A). To explore a potential involvement of glia-derived TGF-β ligands in signaling synaptic development, we expressed RNAi transgenes targeting Daw, Mav, and MYO transcripts specifically in peripheral glia using the Gal4 driver Gli-Gal4 (rl82-Gal4) [6, 7]. Downregulating Mav and Daw, but not MYO, in NMJ glia substantially reduced NMJ size, as determined by counting the number of synaptic boutons at the third-instar larval stage (Figures 1C–1G). In the case of Mav, the number of branches was also reduced (the number of branches in Mav-RNAi glia is 9.13 ± 0.70 [n = 15] compared with 17.0 ± 0.50 [n = 18] in controls).

Figure 1. Glial Mav Regulates TGF-β Activation.

(A) Real-time PCR products from larval segmental nerve and embryonic RNA, showing that MYO, Daw, and Mav transcripts, but not Actβ transcripts, are detected in nerve glia. * indicates an unspecific product as determined by sequencing (n = 3).

(B) Reverse transcriptase PCR from larval brain and segmental nerve RNA, showing that the neuron-specific transcript elav is present in brain but not in segmental nerve RNA.

(C) Number of boutons at muscles 6 and 7 (segment A3) of third-instar larvae expressing Mav-RNAi, MYO-RNAi, or Daw-RNAi in NMJ glia (Gli-Gal4) and Mav-RNAi in neurons (C380-Gal4) or muscles (C57-Gal4), showing that downregulating Mav in NMJ glia reduces bouton number (from left to right, n = 22, 11, 14, 6, 9, 16, 17).

(D–G) Confocal images of third-instar larval NMJs labeled with anti-HRP in (D) wild-type control and animals expressing (E) Mav-RNAi, (F) MYO-RNAi, or (G) Daw-RNAi in NMJ glia.

(H–N) Confocal images of NMJ branches in preparations double labeled with anti-HRP and anti-P-Mad in (H) controls and (I–N) larvae expressing (I) Mav-RNAi, (J) MYO-RNAi, or (K) Daw-RNAi in glia; (L) Mav-RNAi in neurons (C380-Gal4); (M) Mav-RNAi in muscles (C57-Gal4); and (N) Mav in glia, showing that Mav downregulation in NMJ glia virtually eliminates P-Mad signal and that this signal is enhanced upon Mav overexpression in NMJ glia.

(O and P) High-magnification views of P-Mad staining at synaptic boutons in (O) control and (P) Mav overexpression in glia.

(Q) Percentage of P-Mad positive synaptic boutons in the indicated genotypes (from left to right, n = 18, 11, 14, 6, 12, 11, 12).

(R) Mean P-Mad signal intensity normalized to control in the indicated genotypes (n = 10 for each genotype).

(S and T) Quantification of the number of (S) boutons and (T) satellite boutons at abdominal segment 3 in muscles 6 and 7 (black bars) and 4 (white bars), in wild-type and Mav glia (from left to right, n = 12 and 17 in both S and T).

Error bars represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar represents 22 μm for (D)–(G), 4 μm for (H)–(N), and 2.5 μm for (O) and (P).

Glia-Derived Mav Is Required for TGF-β Signaling at Synaptic Sites

A classical readout of TGF-β pathway activation is Mad phosphorylation (P-Mad) [8]. At the Drosophila larval NMJ, TGF-β activation through P-Mad detection has been documented in both motor neuron nuclei [3] and synaptic boutons of the NMJ [9]. At synaptic boutons, P-Mad signal is organized into discrete puncta decorating synaptic boutons [9] (Figure 1H). Notably, downregulating Mav in peripheral glia with two different Mav-RNAi constructs targeting different regions of the Mav transcript virtually eliminated or severely reduced P-Mad immunoreactivity at synaptic sites (Figures 1I and 1Q). In contrast, downregulating MYO had no effect (Figures 1J and 1Q). A decrease in P-Mad signal was also observed by downregulating Daw in glia (Figure 1K), but this effect was much weaker (Figure 1Q).

To assess whether Mav was exclusively required in glia for activation of TGF-β signaling, we also expressed Mav-RNAi in either muscles or motor neurons. However, we observed no significant change in synaptic P-Mad levels as a result of these manipulations (Figures 1L, 1M, and 1Q). Thus, Mav is exclusively required in glia for activation of TGF-β signaling at synaptic sites. Further evidence for such requirement was obtained by examining the effect of overexpressing Mav in glia, which resulted in an increase of P-Mad signal intensity at the NMJ (Figures 1N–1P, and 1R). Although there was no significant increase in the number of synaptic boutons at muscles 6 and 7 (Figure 1S, black bars) in parallel with the increase in synaptic P-Mad intensity, the number of boutons at muscle 4 was significantly increased (Figure 1S, white bars). This increase was primarily due to an increase in the number of satellite boutons (small boutons emerging from normally sized synaptic boutons), which were significantly increased at muscles 6/7 and 4 (Figure 1T).

In contrast to glia, downregulating Mav in motor neurons or muscles did not significantly change NMJ size (Figure 1C). Interestingly, in vitro studies of the synaptogenic effects of Xenopus Schwann cells (SCs) led to the proposal that SC-derived TGF-β1 could promote synaptogenesis [10]. However, the exact source of the synaptogenic signal was not clear, and whether TGF-β1 plays a role in the intact organism remains to be determined [10]. Our observations provide direct evidence indicating that a glia-derived TGF-β ligand can influence both TGF-β signaling and synaptic growth in vivo at the NMJ.

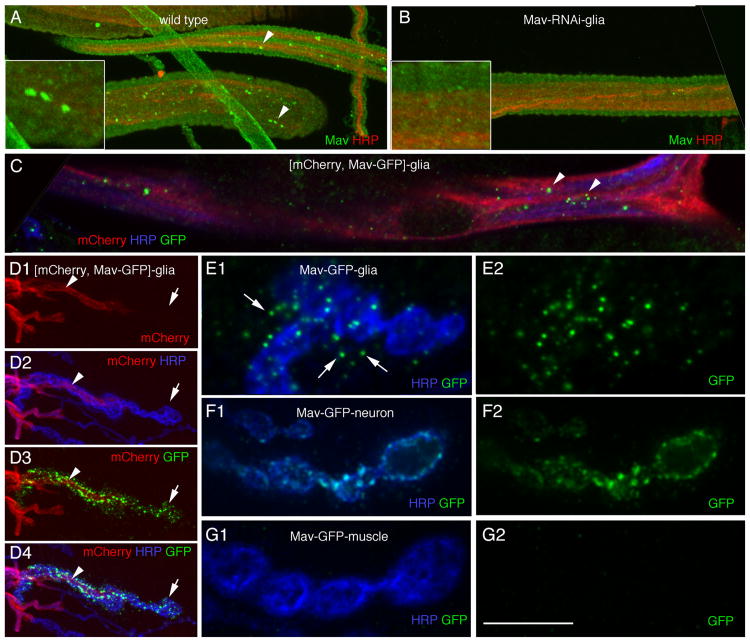

Peripheral Glia Can Secrete Mav

The requirement for peripheral glia in TGF-β pathway activation and synaptic bouton growth led us to predict that peripheral glia should be capable of releasing Mav. We generated an anti-Mav peptide antibody and found that it labeled bright puncta within peripheral glial cells (Figure 2A), consistent with our detection of Mav transcript in these cells (Figure 1A). This labeling was specific, because it was almost completely eliminated by expressing Mav-RNAi1 in peripheral glia (Figure 2B). To determine whether Mav could be released by peripheral glia, we generated transgenic flies expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Mav transgene and drove its expression in NMJ glia with the rl82-Gal4 driver. This transgene was likely to be functional, because it behaved just like the untagged Mav transgene. In particular, expressing the GFP-tagged transgene in glia induced a significant increase in the number of boutons and satellite boutons (the number of boutons at muscle 4 is 63.3 ± 3.7 when Mav-GFP is expressed in glia [n = 18], compared with 62.1 ± 3.1 when untagged Mav is expressed in glia [n = 17], and 39.5 ± 2.0 in controls [n = 12]; the number of satellite boutons at muscle 4 is 19.5 ± 1.5 when Mav-GFP is expressed in glia [n = 18], compared with 19.8 ± 1.1 when untagged Mav is expressed in glia [n = 17] and 5.5 ± 0.9 in controls [n = 12]). As with endogenous Mav, Mav-GFP became distributed in bright GFP puncta within glia in the segmental nerves (Figure 2C). In addition, Mav-GFP was prominent at glial extensions that interact with the NMJ (Figure 2D, arrowhead), showing that Mav-GFP is efficiently transported to these glial extensions. Notably, bright GFP puncta were also observed beyond the boundary of glial extensions (Figures 2D and 2E), indicating that Mav-GFP could be released by peripheral glial cells. Close observation of the Mav-GFP puncta outside the glial membrane extensions revealed their localization in close association with both synaptic boutons and the postsynaptic junctional region of the muscle (Figure 2E, arrows). In contrast, expressing Mav-GFP in neurons resulted in punctate and diffuse GFP staining within synaptic boutons, but no GFP signal was observed beyond the boundary of synaptic boutons (Figure 2F), showing that Mav-GFP is likely not released from synaptic boutons. Similarly, expressing Mav-GFP in muscles resulted in very dim GFP signal in muscle cells, but this signal did not localize to the NMJ (Figure 2G). Thus, Mav mRNA and protein are present in peripheral glia, glia can secrete transgenic Mav, and secreted Mav associates with synaptic boutons and muscles. Our previous studies demonstrated that peripheral glial membrane extensions at the NMJ are dynamic, extending and retracting processes that become associated with synaptic boutons and muscles [6]. Therefore, it is possible that glial membrane extensions might directly deposit Mav as they dynamically interact with boutons or muscles. Alternatively, glia-derived Mav may be released from these processes and diffuse to relatively distant sites.

Figure 2. Mav Is Present in Peripheral Glia and Can Be Secreted by Glia.

(A and B) Anti-Mav labeling of larval segmental nerves in anti-HRP and Mav double-labeled preparations in (A) wild-type and (B) larvae expressing Mav-RNAi-1 in peripheral glia, showing the presence of endogenous Mav in peripheral glia (arrowheads). Insets show high-magnification views of a segmental nerve region.

(C) Distribution of transgenic Mav-GFP in peripheral glia in a preparation also expressing mCherry in peripheral glia and double labeled with antibodies to HRP and GFP, showing punctate GFP label similar to endogenous Mav (arrowheads).

(D) Mav-GFP expressed in peripheral glia shows strong punctate GFP label within NMJ glial extensions (arrowhead) as well as associated with NMJ regions devoid of glial membranes (arrow).

(E–G) High-magnification views of NMJ branches labeled with anti-HRP and anti-GFP showing the distribution of Mav-GFP when expressed in (E) NMJ glia, (F) neurons, and (G) muscles. Only when Mav-GFP is expressed in glia is it observed outside of the producing cell.

Scale bar represents 15 μm for (A)–(C), 12 μm for (D), and 5 μm for (E)–(G).

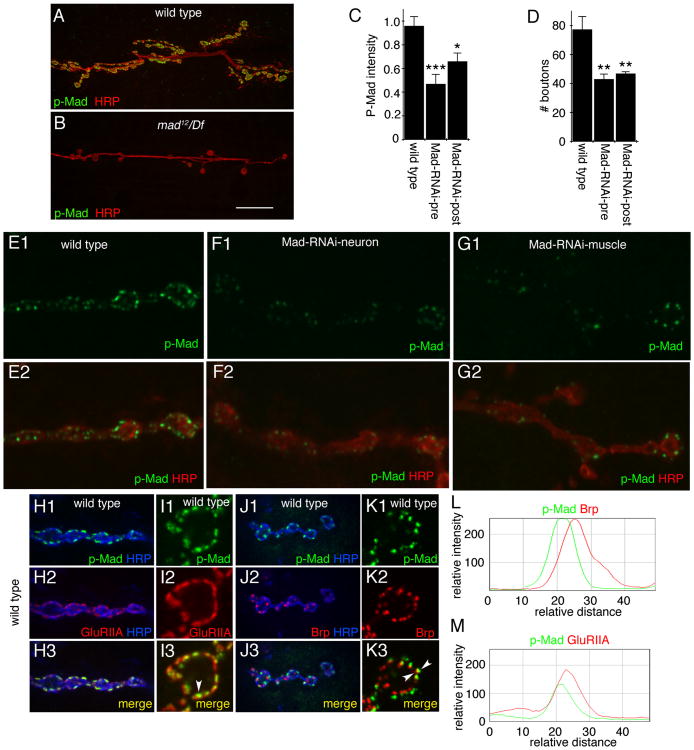

Synaptic TGF-β Signaling Is Activated Both Pre- and Postsynaptically

The finding that glia can release Mav, and that glia-derived Mav is required for TGF-β signaling at synaptic sites, raised the question as to which cells (neurons or muscles) respond to Mav. The synaptic P-Mad signal is virtually absent when Mav is downregulated in glia. However, whether the P-Mad signal is pre- or postsynaptic has been a matter of debate. One study reported that synaptic P-Mad partially colocalized with the presynaptic active zone marker Bruchpilot (BRP) while it did not colocalize with Discs-large (DLG), suggesting that P-Mad is presynaptic [11]. However, DLG is localized at the perisynaptic region within the pre- and postsynaptic compartments [12], and thus it is not expected to colocalize with the postsynaptic density. Another study reported that in wit mutants, the synaptic P-Mad signal was eliminated [13]. Given the role of Wit receptors in activating TGF-β signaling in motor neurons, it was concluded that P-Mad was presynaptic. However, whether Wit is also expressed in muscles is unknown. In a third report, the synaptic P-Mad signal was found to completely colocalize with a tagged glutamate receptor GluRIIA transgene, which suggested a postsynaptic P-Mad localization [9]. However, a comparison with endogenous GluRs was not done. To address this issue more directly, we first used a strong hypomorphic mad mutant, mad12, over a mad deficiency chromosome (mad12/Df) and examined P-Mad labeling at the NMJ. P-Mad immunoreactivity was completely eliminated in this mutant (Figures 3A and 3B), providing direct evidence for the specificity of the P-Mad signal we observe at the NMJ. We then downregulated Mad in either motor neurons or muscles by expressing Mad-RNAi and examined the intensity of the synaptic P-Mad signal. We found that downregulating Mad in either neurons or muscles resulted in a significant decrease in P-Mad signal intensity (Figures 3C and 3E–3G), suggesting both a presynaptic and postsynaptic localization of P-Mad. Importantly, the number of synaptic boutons was significantly reduced by downregulation of Mad in either neurons or muscles (Figure 3D), arguing strongly for a requirement for Mad function in both cell types.

Figure 3. Mad Is Activated in Both Pre- and Postsynaptic Cells at the NMJ.

(A and B) NMJs double labeled with antibodies to HRP and P-Mad in (A) wild-type and (B) mad12/Df, showing that P-Mad immunoreactivity at the NMJ is specific.

(C) P-Mad signal intensity in the indicated genotypes, showing that P-Mad signal is reduced by downregulating Mad in either neurons or muscles (from left to right: n = 11, 7, 8).

(D) Number of boutons in the indicated genotypes, showing that interfering with Mad function in either muscles or neurons reduces NMJ size (from left to right, n = 25, 24, 16).

(E–G) NMJ arbors double labeled with anti-HRP and P-Mad antibodies in (E) wild-type and larvae expressing Mad-RNAi in either (F) neurons or (G) muscles.

(H–K) NMJs double labeled with anti-HRP, anti-P-Mad, and (H and I) anti-GluRIIA or (J and K) anti-Brp, showing that P-Mad is completely encompassed by GluRIIA immunoreactivity and juxtaposed to Brp immunoreactivity. (I) and (K) are high-magnification views of a single bouton.

(L and M) Fluorescence intensity profiles across the midline of a bouton showing (L) shifted profiles between Brp and P-Mad and (M) a similar profile between GluRIIA and P-Mad.

Error bars represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar represents 25 μm for (A) and (B), 3 μm for (E)–(G), 7 μm for (H) and (J), and 2.5 μm for (I) and (K).

We also examined the localization of P-Mad in comparison with the endogenous localization of GluRIIA and BRP. Confirming previous reports with the GluRIIA transgene, we found that synaptic P-Mad was always present within the boundaries of endogenous GluRIIA clusters (Figures 3H, 3I, and 3M). In contrast, only partial colocalization between BRP and P-Mad was observed, and the signals appeared juxtaposed (Figures 3J–3L). However, given that active zones and postsynaptic GluR clusters are apposed to each other in close proximity (<40 nm), we note that light microscopy alone cannot resolve this issue. Nevertheless, the finding that downregulating Mad in either muscles or neurons leads to both P-Mad reduction and NMJ growth defects (Figures 3C and 3E–3G) is a strong indication that the signal is localized to both types of cells.

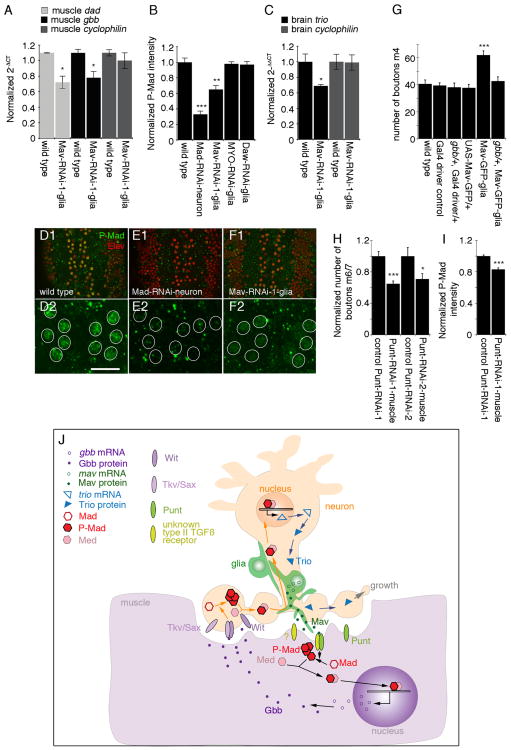

Glia-Derived Mav Activates Dad and Gbb Transcription in Muscle Cells

The finding that synaptic P-Mad can be attributed to muscles in addition to neurons, and that this signal is virtually eliminated by downregulating Mav in NMJ glia, provided compelling evidence that a TGF-β signal is activated in muscles as previously proposed [9]. To confirm this finding, we used an additional reporter of TGF-β pathway activation, the transcription of daughters against dpp (Dad), an inhibitory Smad that antagonizes TGF-β signaling [9, 14]. Real-time PCR from larval body wall muscle RNA demonstrated that dad transcript was significantly decreased upon expression of Mav-RNAi in glia (Figure 4A), providing additional support for a role of glia-derived Mav in activating TGF-β signaling in muscles.

Figure 4. Regulation of Retrograde Signaling by Glia-Derived Mav.

(A) Real-time PCR of larval muscle RNA, showing that dad and gbb transcripts are significantly decreased in muscle when Mav is downregulated in NMJ glia (n = 3).

(B) Normalized P-Mad intensity in motor neuron nuclei in the indicated genotypes, showing that Mav downregulation in glia results in a reduction in P-Mad levels in neurons (from left to right, n = 12, 11, 10, 8, 9).

(C) Real-time PCR of larval brain RNA, showing that Trio transcript is reduced in brain when Mav is downregulated in glia (n = 3).

(D–F) View of larval ventral ganglia shown at (D1–F1) low and (D2–F2) high magnification in preparations double labeled with anti-Elav and anti-P-Mad antibodies in (D) wild-type and larvae expressing (E) Mad-RNAi in neurons or (F) Mav-RNAi in peripheral glia.

(G) Number of boutons on muscle 4 (segment A3) in the indicated genotypes, demonstrating that removal of a single copy of gbb suppresses the effect of overexpressing Mav-GFP in glia (from left to right, n = 11, 12, 12, 13, 18, 12).

(H) Normalized number of boutons on muscles 6 and 7 in controls (UAS-Punt-RNAi/+) or in larvae expressing the Punt-RNAi constructs using C57-Gal4 (Punt-RNAi-muscle). Samples were normalized to their respective controls to allow direct comparisons (from left to right, n = 12, 13, 10, 12).

(I) Normalized P-Mad intensity in motor neuron nuclei in control and Punt-RNAi-1-muscle samples, showing reduction of P-Mad signal when Punt is downregulated in muscles (from left to right, n = 35, 34).

(J) Model of glia-derived Mav signaling. Mav is secreted by glia and binds to the type II receptor Punt, which together with an unknown type I TGF-β receptor phosphorylates postsynaptically localized Mad. P-Mad dimerizes with the co-Smad Medea (Med) and translocates into the muscle nucleus, where it activates Gbb transcription. Muscle Gbb is released by muscles and retrogradely activates Wit and Tkv or Sax receptors in presynaptic terminals. This leads to presynaptic phosphorylation of Mad, which in a complex with Med translocates into motor neuron nuclei and activates Trio transcription. Trio is transported to presynaptic endings, where it regulates synaptic bouton growth.

Error bars represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar represents 10 μm for (D2)–(F2) and 25 μm for (D1)–(F1).

It has been previously reported that the transcription of the Glass bottom boat (Gbb) retrograde ligand is also regulated by TGF-β pathway activation [15]. Interestingly, downregulating Mav in glia resulted in a significant decrease in muscle gbb transcript levels (Figure 4A). In contrast, cyclophilin control transcript levels were not affected (Figure 4C). This observation raised the possibility that glial cells could modulate the intensity of the retrograde signal. To test this model, we examined P-Mad levels in the nuclei of motor neurons (a readout for retrograde TGF-β pathway activation). Expression of Mad-RNAi in motor neurons led to a drastic decrease in P-Mad immunoreactivity at motor neuron nuclei, demonstrating that the P-Mad signal at this site is specific (Figures 4B, 4D, and 4E). Most importantly, and consistent with our model, P-Mad immunoreactivity levels were significantly decreased in the nuclei of larval motor neurons when Mav-RNAi, but not MYO-RNAi or Daw-RNAi, was expressed in peripheral glia (Figures 4B, 4D, and 4F).

Finally, we also examined the levels of a TGF-β target gene in motor neurons, Trio [5]. Trio is a Rac-activating protein that contributes to cytoskeletal remodeling during synaptic growth. Previous studies demonstrated that upon activation of motor neuron TGF-β signaling by muscle Gbb, trio transcription is upregulated [5, 16]. Real-time PCR revealed that trio transcript levels were significantly reduced in RNA isolated from larval brains when Mav-RNAi was expressed in peripheral glia (Figure 4C). In contrast, cyclophilin control transcript levels were unchanged by this manipulation (Figure 4C). These results provide strong evidence that glia-derived Mav also modulates motor neuron TGF-β signaling. This modulation might occur through direct interaction of Mav with TGF-β receptors in motor neurons, or by regulating the levels of Gbb in muscles, leading to a change in Gbb release.

In support of the above model, we found that Mav function in NMJ development depended on Gbb. As noted, overexpressing Mav in glia results in a significant increase in the number of boutons (Figures 1S and 4G). In contrast,no change in bouton number was observed in gbb/+ heterozygous larvae (Figure 4G). Notably, the increase in bouton number observed upon overexpression of Mav in glia was completely suppressed in gbb/+ heterozygous larvae (Figure 4G). These results point to a role of Gbb in mediating the response to glia-derived Mav during NMJ development.

We also found evidence pointing to Punt as the likely receptor mediating the muscle response to glia-derived Mav. Downregulating Punt in muscle using two different RNAi lines targeted to different regions of Punt and the C57-Gal4 driver resulted in a substantial decrease in bouton number compared with the driver control (Figure 4H). In addition, downregulating Punt in muscle decreased the levels of P-Mad immunoreactivity in motor neuron nuclei (Figure 4I).

In summary, our studies provide direct in vivo evidence that glial cells secrete a TGF-β ligand, Mav, that influences the magnitude of Gbb-mediated muscle-to-motor neuron retrograde signaling. By controlling TGF-β signaling in both muscles and neurons, glial cells are well positioned to integrate the coordinated development of pre- and postsynaptic compartments.

It is interesting to note, however, that there could be partial redundancy between the two activin-type ligands, Mav and Daw, because glial knockdown of either leads to decreased NMJ growth (Figure 1C) and synaptic P-Mad (Figure 1Q), although the effect of Mav downregulation is substantially more severe. However, only glial knockdown of Mav affected levels of motor neuron nuclear P-Mad (Figure 4B), suggesting that the pathways activated by the two ligands diverge [15]. This divergence could result from the use of different receptor isoforms. For example, the activins Actb and Daw can have different effects on the same tissues, as a result of differential interactions with alternative Baboon isoforms [15, 17]. Nevertheless, this work identifies a novel glial synaptogenic factor and provides compelling evidence for a critical role for glia in modulation of synapse assembly at the NMJ in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

Drosophila Strains

We used Gli-Gal4 (rl82-Gal4) [18], C57-Gal4 and C380-Gal4 [19], UAS-mCD8-GFP [20], UAS-mCD8∷mCherry (gift from Mary Logan), UAS-Mad-RNAi (ID 12635, Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center [VDRC]), UAS-MYO-RNAi (ID 33132, VDRC), UAS-Daw-RNAi (ID 105309, VDRC), UAS-Mav-RNAi-1 (generous gift from Tzumin Lee), UAS-Mav-RNAi-2 (ID 1901R-4, National Institute of Genetics, Japan), UAS-Punt-RNAi-1 (ID 107071, VDRC), UAS-Punt-RNAi-2 (ID 848, VDRC), and gbb1[21]. We also generated UAS-Mav and UAS-Mav-GFP by subcloning wild-type (WT) Mav (or Mav-GFP) cDNA into the pUAST vector. Transgenic constructs were transformed into w1118 flies by BestGene Inc.

Real-Time PCR

Three independent extractions of total RNA were isolated from dissected third-instar peripheral nerves, body wall muscles, or larval brain; extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen); and purified using an RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Sensiscript RT (QIAGEN) for nerve RNA or SuperScript III enzyme for brain and BWM RNA with oligo (dT) 12-18 primer (Invitrogen). The following TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems) were used: Repo (ID Dm02134815_g1), MYO (ID Dm01820708_g1), Daw (ID Dm01814209_g1), Mav (ID Dm01825561_g1), Activin β (ID Dm01831511_m1), Gapdh (ID Dm01841185_m1), Dad (ID Dm02134937_m1), Gbb (ID Dm01843010_s1), Trio (ID Dm01795013_m1), Cyclophilin 1 (ID Dm01813702_m1), and RpL32 (ribosomal protein L32 [ID Dm02151827_ g1] was our endogenous control gene for brain and body wall muscles). PCR protocol was 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for1 min. Real-time curves were monitored using -RT as negative controls and WT embryos as positive control for the primers. Data were analyzed via the delta-delta Ct method [22]. PCR products were run on agarose gel (see Figure 1A) and sequenced to verify gene identity. As a negative control, cDNA from brain and nerve was PCR amplified with either Elav (forward: CGCATGCTGGCGTAGGCACACC; reverse: CGAAAGTTG TAGGTTTGGACACGG) or Gapdh (forward: ACTCGACTCACGGTCGTTTC; reverse: GCCGAGATGATGACCTTCTT) primers.

Immunolabeling and Confocal Microscopy

Third-instar Drosophila larval body wall muscles were dissected in calciumfree saline [23] and fixed for 10 min with nonalcoholic Bouin's fixative unless otherwise noted. Larval brains were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 hr. Primary antibodies were anti-P-Mad (1:100, Cell Signaling), anti-Elav (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]), anti-GluRIIA (1:3, DSHB), anti-DLG (1:20,000 [24]), anti-GFP (1:200, Molecular Probes), nc82 (anti-Brp, 1:100, DSHB), anti-Mav (1:50, see below), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or Texas red-conjugated anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Secondary antibodies conjugated to DyLight 488, 594, or 649 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used at 1:200. Samples were imaged using an Intelligent Imaging Innovations Everest spinning-disk confocal system with a PlanApo 63× 1.4 NA oil lens and analyzed with ImageJ (1.45I) software.

Generation of Mav Antibody

Affinity-purified chicken anti-Mav antibody was generated by 21st Century Biochemicals using a peptide encompassing amino acids 371–389 of Mav-PA(C-PLTNAQDANFHHDKIDEA-N-amide).

Quantifications

Samples used for quantification were processed simultaneously and confocaled in the same imaging session using identical acquisition parameters. The percentage of P-Mad-positive boutons was quantified for type 1b boutons from preparations double labeled with anti-HRP and P-Mad antibodies by counting the number of boutons containing P-Mad signal and expressing it as a percentage of total bouton number. To analyze the P-Mad subcellular localization, we used samples in which we knocked down Mad in muscle or motor neurons. We used Volocity software (5.5.1) to detect positive puncta and calculated P-Mad intensities normalized to HRP volume and subsequently normalized to WT. To measure synaptic P-Mad fluorescence intensity, NMJs (muscles 6 and 7, segment A3) from ten different larvae of each genotype, we blindly chose WT control or glial Mav overexpression animals. The P-Mad puncta within boutons were then manually selected and the mean intensity of the P-Mad label was quantified using ImageJ (1.45I). The data are shown as P-Mad fluorescence mean intensity.

The intensity of motor neuron nuclei P-Mad signal was quantified in confocal slices in the dorsal region of the CNS cell cortex containing motor neuron cell bodies in preparations double labeled with anti-Elav and P-Mad antibodies. Total intensity of P-Mad signal was measured within the Elavpositive boundary, which marks the motor neuron nuclei, using ImageJ (1.45I). Intensities were normalized to WT controls.

Branch number was measured at muscles 6 and 7 (abdominal segment 3) starting at the primary neurite, where the axon first meets the muscle, and scoring each neurite after a branch point. For example, if a single neurite branched into a “Y” formation, it was scored as a 3.

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests were run for comparisons of experiments in which a single experimental sample was processed in parallel with a WT control. In cases where multiple experimental groups were compared to a single control, a one-way ANOVA was performed with Dunnett's post hoc test. Error bars in all graphs represent ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Freeman and Budnik lab for helpful discussions. We also thank Tzumin Lee for sharing UAS-Mav-RNAi1 flies prior to publication, Mary Logan for sharing UAS-mCD8∷mCherry flies, and Kristi Wharton for gbb1 mutant flies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 MH070000 to V.B. and NS053538 to M.F.

References

- 1.Eroglu C, Barres BA. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–231. doi: 10.1038/nature09612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman MR, Doherty J. Glial cell biology in Drosophila and vertebrates. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCabe BD, Marqués G, Haghighi AP, Fetter RD, Crotty ML, Haerry TE, Goodman CS, O'Connor MB. The BMP homolog Gbb provides a retrograde signal that regulates synaptic growth at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 2003;39:241–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marqués G, Haerry TE, Crotty ML, Xue M, Zhang B, O'Connor MB. Retrograde Gbb signaling through the Bmp type 2 receptor wishful thinking regulates systemic FMRFa expression in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:5457–5470. doi: 10.1242/dev.00772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball RW, Warren-Paquin M, Tsurudome K, Liao EH, Elazzouzi F, Cavanagh C, An BS, Wang TT, White JH, Haghighi AP. Retrograde BMP signaling controls synaptic growth at the NMJ by regulating trio expression in motor neurons. Neuron. 2010;66:536–549. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuentes-Medel Y, Logan MA, Ashley J, Ataman B, Budnik V, Freeman MR. Glia and muscle sculpt neuromuscular arbors by engulfing destabilized synaptic boutons and shed presynaptic debris. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auld VJ, Fetter RD, Broadie K, Goodman CS. Gliotactin, a novel transmembrane protein on peripheral glia, is required to form the blood-nerve barrier in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:757–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross JJ, Shimmi O, Vilmos P, Petryk A, Kim H, Gaudenz K, Hermanson S, Ekker SC, O'Connor MB, Marsh JL. Twisted gastrulation is a conserved extracellular BMP antagonist. Nature. 2001;410:479–483. doi: 10.1038/35068578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudu V, Bittig T, Entchev E, Kicheva A, Jülicher F, González-Gaitán M. Postsynaptic mad signaling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Curr Biol. 2006;16:625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Z, Ko CP. Schwann cells promote synaptogenesis at the neuromuscular junction via transforming growth factor-beta1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9599–9609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2589-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connor-Giles KM, Ho LL, Ganetzky B. Nervous wreck interacts with thickveins and the endocytic machinery to attenuate retrograde BMP signaling during synaptic growth. Neuron. 2008;58:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sone M, Suzuki E, Hoshino M, Hou D, Kuromi H, Fukata M, Kuroda S, Kaibuchi K, Nabeshima Y, Hama C. Synaptic development is controlled in the periactive zones of Drosophila synapses. Development. 2000;127:4157–4168. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higashi-Kovtun ME, Mosca TJ, Dickman DK, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Importin-beta11 regulates synaptic phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic, and thereby influences synaptic development and function at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5253–5268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3739-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuneizumi K, Nakayama T, Kamoshida Y, Kornberg TB, Christian JL, Tabata T. Daughters against dpp modulates dpp organizing activity in Drosophila wing development. Nature. 1997;389:627–631. doi: 10.1038/39362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis JE, Parker L, Cho J, Arora K. Activin signaling functions upstream of Gbb to regulate synaptic growth at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Dev Biol. 2010;342:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentes-Medel Y, Budnik V. Ménage à Trio during BMP-mediated retrograde signaling at the NMJ. Neuron. 2010;66:473–475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen PA, Zheng X, Lee T, O'Connor MB. The Drosophila Activin-like ligand Dawdle signals preferentially through one isoform of the type-I receptor Baboon. Mech Dev. 2009;126:950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sepp KJ, Auld VJ. Conversion of lacZ enhancer trap lines to GAL4 lines using targeted transposition in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;151:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.3.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budnik V, Koh YH, Guan B, Hartmann B, Hough C, Woods D, Gorczyca M. Regulation of synapse structure and function by the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg. Neuron. 1996;17:627–640. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressiblecell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wharton KA, Cook JM, Torres-Schumann S, de Castro K, Borod E, Phillips DA. Genetic analysis of the bone morphogenetic protein-related gene, gbb, identifies multiple requirements during Drosophila development. Genetics. 1999;152:629–640. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jan LY, Jan YN. Properties of the larval neuromuscular junction in Drosophila melanogaster. J Physiol. 1976;262:189–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh YH, Popova E, Thomas U, Griffith LC, Budnik V. Regulation of DLG localization at synapses by CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation. Cell. 1999;98:353–363. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81964-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]