Abstract

Differences in the pathogenicity of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) strains may be due, at least partially, to different expression patterns of some virulence genes. To investigate this hypothesis, the virulence gene expression patterns of 6 atypical EPEC strains isolated from healthy and diarrheic ruminants were compared using quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction after growing the bacteria in culture medium alone or after binding it to HeLa epithelial cells. Some virulence genes in strains from diarrheic animals were upregulated relative to their expression in strains from healthy animals. When bacteria were cultured in the presence of HeLa cells, the ehxA and efa1/lifA genes, previously associated with the production of diarrhea, were expressed at higher levels in strains from diarrheic animals than in strains from healthy animals. Thus, the expression levels of some virulence genes may help determine which atypical EPEC strains cause diarrhea in ruminants.

Résumé

Des différences dans la pathogénicité de souches atypiques d’Escherichia coli entéropathogènes (EPEC) peuvent être dues, au moins en partie, à différents patrons d’excrétion de quelques-uns des gènes de virulence. Pour étudier cette hypothèse, les patrons d’expression des gènes de virulence de six souches atypiques d’EPEC isolées de ruminants en santé et avec diarrhée ont été comparés par une épreuve quantitative en temps réel de réaction d’amplification en chaîne par la polymérase par transcription réverse après avoir fait croître la bactérie dans un milieu de culture seul ou après l’avoir liée à des cellules épithéliales HeLa. Quelques gènes de virulence dans des souches provenant d’animaux avec diarrhée étaient régulés à la hausse relativement à leur expression dans les souches provenant d’animaux en santé. Lorsque les bactéries étaient cultivées en présence de cellules HeLa, les gènes ehxA et efa1/lifA, précédemment associés avec la production de diarrhée, étaient exprimés à des niveaux plus élevés dans les souches provenant d’animaux diarrhéiques que dans les souches provenant d’animaux en santé. Ainsi les niveaux d’expression de certains gènes de virulence pourraient aider à déterminer quelles souches atypiques d’EPEC causent de la diarrhée chez les ruminants.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) are a cause of diarrhea in ruminants and humans, although these bacteria can also be isolated from healthy ruminants and humans (1,2). These bacteria cause a characteristic attaching and effacing (AE) lesion in the gut mucosa because of the intimate bacterial adhesion to the enterocytes and effacement of the brush border microvilli (2). Formation of AE lesions is governed by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE). This locus contains the eae gene, which encodes an outer membrane protein called intimin, necessary for intimate attachment to epithelial cells (2). The LEE also encodes a type III secretion system; EPEC-secreted proteins (Esp), such as EspA, which is essential for the delivery of proteins into the host cell; and LEE-encoded regulator (Ler), which positively regulates virulence factors (3,4). Additional non-LEE-encoded virulence factors have been described, such as Efa1/LifA, which is encoded by the pathogenicity island PAI OI-122, and enterohemolysin, which is encoded by large plasmids, such as pO157 (5,6).

Molecular characterization of atypical EPEC strains isolated from humans and ruminants has revealed a tremendous diversity of virulence genes among different strains (1,6,7). Therefore, it is possible that different atypical EPEC strains have different pathogenic potential and that only some of them can cause disease in humans and animals. It seems likely that only the atypical EPEC strains possessing certain virulence genes, such as efa1/lifA and ehxA, can cause disease (1,5,6). However, it is also possible that differences in pathogenicity among strains may be due, at least partially, to different expression patterns of some virulence genes. In support of this hypothesis, a previous study has found that expression of virulence genes differs among enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 strains depending on whether their genotype is predominant among human clinical cases or among bovines (8). Despite this evidence suggesting a link between expression profiles of virulence genes and pathogenicity, the authors are unaware of studies that compare levels of virulence gene expression among atypical EPEC strains isolated from healthy and diarrheic ruminants.

The aim of this study was to establish whether differences in virulence gene expression can be detected between atypical EPEC strains that share the same serotype and virulence gene profile, but differ in whether they were isolated from healthy or diarrheic ruminants.

Six strains were tested in this study in pairs, with one strain coming from a diarrheic ruminant and the paired strain coming from a normal ruminant. The strain pairs were as follows: O153:HNM strains (NM indicates non-motile) isolated from a diarrheic lamb and a healthy sheep, O26:HNM strains isolated from a diarrheic calf and a healthy cow, and O26:H11 strains isolated from a diarrheic lamb and a healthy goat. The genes analyzed were eae, espA, ler, efa1/lifA, and ehxA, which encode enterohemolysin. The strains used in this study have previously been characterized (1) and possess all 5 genes analyzed, except for the O26:HNM strains, which lack ehxA.

Virulence gene expression in enteropathogenic bacteria is regulated by environmental conditions (9), so expression was analyzed in the present study under 2 sets of conditions: after culturing the bacteria in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) and after co-culturing them in the same medium together with HeLa cells. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium was chosen because it provides a controlled environment with minimal variation in growth conditions, and it has also been shown to induce expression of LEE genes (8,10). The HeLa epithelial cells were used because growth in the presence of epithelial cells may better simulate the gastrointestinal tract environment than growth in DMEM (8). In the first set of conditions, strains were grown to exponential phase in DMEM, the bacteria were sedimented by centrifugation (5000 × g for 5 min) and the pellet was stored in RNA stabilization solution (RNA later; Invitrogen, Prat de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain) for subsequent RNA purification. In parallel, under the second set of conditions, HeLa cells were infected with “preactivated” bacteria, which had been grown to early- or mid-log phase at 37°C in DMEM (9), at a multiplicity of infection of 100:1. After 5 h of incubation, the HeLa cells were washed vigorously to remove nonadhering bacteria, and cells with adhered bacteria were collected in RNA stabilization solution until RNA isolation. Culturing of the atypical EPEC strains alone in DMEM or in the presence of HeLa cells was carried out at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Total bacterial RNA was extracted using a commercial RNA isolation kit (High Pure RNA Isolation kit; Roche Applied Science, Sant Cugat del Vallés, Barcelona, Spain) and cDNA was synthesized using a commercial kit (qScript cDNA SuperMix kit; Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was done using a RT-PCR thermocycler (7300 Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems, Tres Cantos, Madrid, Spain) and a commercial dye (FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix; Roche Applied Science). Samples were tested in duplicate. Previously published primers were used to amplify the eae, ler, and ehxA genes (11–13). In addition, primers were designed in the present study to amplify the espA gene (espAq-F: 5′-GATGCCTCATTCATATCAGC-3′ and espAq-R: 5′-TCGGTGTTTTTCAGGCT GC-3′) and efa1/lifA gene (efaF-RT: 5′-TGGTAGTCAGGTATACATCCGTATTTC-3′ and efaR-RT: 5′-GCTGAAAACCGGCACAAT-3′). Data were analyzed using Gene Expression’s CT Difference method and individual PCR efficiencies were determined using LinRegPCR, as previously described (14). The 16S rRNA housekeeping gene was used as the internal control (15). Genes whose expression in strains from diarrheic animals relative to their expression in strains from healthy animals that changed 0.5- to 1.5-fold, were classified as unchanged.

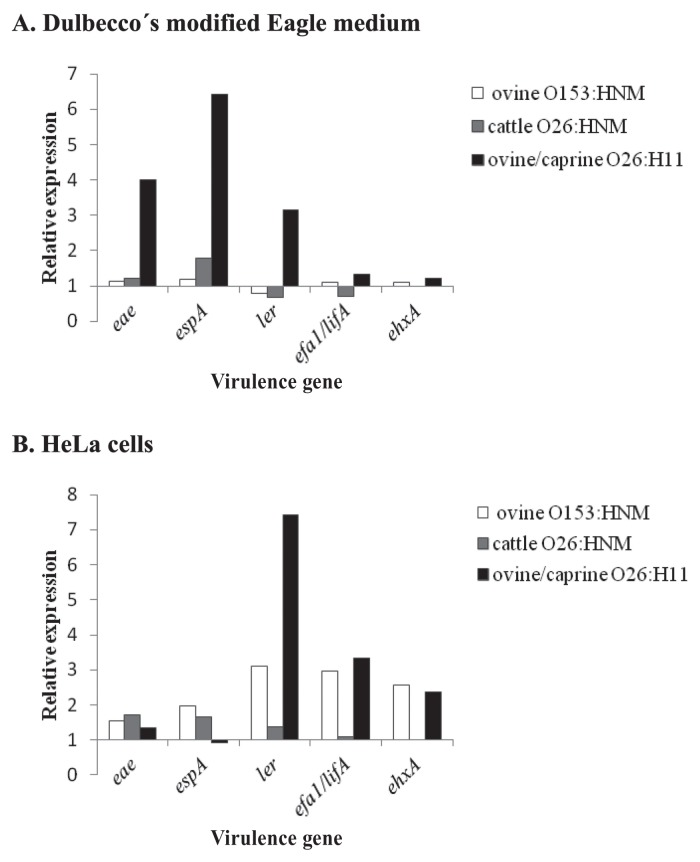

When cultured in DMEM, there was no difference in gene expression except for eae, espA, and ler in the pair of O26:H11 strains (Figure 1A). These 3 genes were expressed at levels 3- to 6-fold higher in bacteria isolated from a diarrheic lamb than from a healthy goat.

Figure 1.

Expression of virulence genes in strains of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheic ruminants relative to their expression in strains isolated from healthy ruminants. A — Strains grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. B — Strains grown in contact with HeLa cells. NM — nonmotile.

When virulence gene expression was compared between strains from diarrheic and healthy hosts after being cultured in contact with HeLa cells, the eae and espA genes were expressed at similar levels between strains, whereas ler, ehxA, and efa1/lifA were expressed at levels 2- to 7-fold higher in O153:HNM and O26:H11 strains isolated from diarrheic animals (Figure 1B). The presence of the ehxA and efa1/lifA genes has been previously associated with diarrhea caused by atypical EPEC in children and neonatal ruminants (1,5,6). In addition, the results of this study suggest that overexpression of these genes may also determine whether atypical EPEC strains can cause diarrhea in neonatal ruminants. Our results on the expression of the eae and espA genes in the pair of O26:H11 strains grown in contact with epithelial cells are not in agreement with those results obtained using the same strains grown in DMEM or with the results of Vanaja et al (8), who found an association between overexpression of LEE genes in E. coli O157:H7 strains grown in DMEM and virulence. It is possible that these differences may be due to the influence of environmental conditions on bacterial gene expression. Thus explaining how Jandu et al (16) were able to find differences in gene expression when E. coli O157:H7 strains were cultured in the presence and absence of epithelial cells.

In summary, the results of this study show that some virulence genes are upregulated in strains isolated from diarrheic animals relative to their expression in strains isolated from healthy animals. Thus, the expression levels of some virulence genes may help determine which atypical EPEC strains cause diarrhea in ruminants. Since this is a preliminary study involving a small number of strains, further studies are required to confirm the role of virulence gene expression in the production of diarrhea by atypical EPEC strains in neonatal ruminants.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from Banco Santander-Universidad Complutense (INBAVET 920338).

References

- 1.Horcajo P, Domínguez-Bernal G, de la Fuente R, et al. Comparison of ruminant and human attaching and effacing Escherichia coli (AEEC) strains. Vet Microbiol. 2012;155:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott SJ, Sperandio V, Girón JA, et al. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator controls expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6115–6126. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6115-6126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garmendia J, Frankel G, Crepin VF. Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic E. coli infections: Translocation, translocation, translocation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2573–2585. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2573-2585.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afset JE, Bruant G, Brousseau R, et al. Identification of virulence genes linked with diarrhea due to atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by DNA microarray analysis and PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3703–3711. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00429-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scaletsky ICA, Aranda KRS, Souza TB, Silva NP, Morais MB. Evidence of pathogenic subgroups among atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3756–3759. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01599-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutin L, Kaulfuss S, Herold S, Oswald E, Schmidt H. Genetic analysis of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serogroup O103 strains by molecular typing of virulence and housekeeping genes and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1552–1563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1552-1563.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanaja SK, Springman AC, Besser TE, Whittam TS, Manning SD. Differential expression of virulence and stress fitness genes between Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains with clinical or bovine-biased genotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:60–68. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01666-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Finlay BB. Expression of attaching/effacing activity by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on growth phase, temperature, and protein synthesis upon contact with epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:966–973. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.966-973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe H, Tatsuno I, Tobe T, Okutani A, Sasakawa C. Bicarbonate ion stimulates the expression of locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded genes in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3500–3509. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3500-3509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chassagne L, Pradel N, Robin F, et al. Detection of stx1, stx2, and eae genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli using SYBR Green in a real-time polymerase chain reaction. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirier K, Fauche SP, Béland M, et al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 survives within human macrophages: Global gene expression profile and involvement of the Shiga toxins. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4814–4822. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00446-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashid RA, Tabata TA, Oatley MJ, et al. Expression of putative virulence factors of Escherichia coli O157:H7 differs in bovine and human infections. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4142–4148. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00299-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schefe JH, Lehmann KE, Buschmann IR, Unger T, Funke-Kaiser H. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis: Current concepts and the novel “gene expression’s CT difference” formula. J Mol Med. 2006;84:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spano G, Beneduce L, Terzi V, Stanca AM, Massa S. Real-time PCR for the detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy and cattle wastewater. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2005;40:164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jandu N, Ho NKL, Donato KA, et al. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 gene expression profiling in response to growth in the presence of host epithelia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]