Abstract

Mutations in the human SEPN1 gene, encoding selenoprotein N (SepN), cause SEPN1-related myopathy (SEPN1-RM) characterized by muscle weakness, spinal rigidity, and respiratory insufficiency. As with other members of the selenoprotein family, selenoprotein N incorporates selenium in the form of selenocysteine (Sec). Most selenoproteins that have been functionally characterized are involved in oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions, with the Sec residue located at their catalytic site. To model SEPN1-RM, we generated a Sepn1-knockout (Sepn1−/−) mouse line. Homozygous Sepn1−/− mice are fertile, and their weight and lifespan are comparable to wild-type (WT) animals. Under baseline conditions, the muscle histology of Sepn1−/− mice remains normal, but subtle core lesions could be detected in skeletal muscle after inducing oxidative stress. Ryanodine receptor (RyR) calcium release channels showed lower sensitivity to caffeine in SepN deficient myofibers, suggesting a possible role of SepN in RyR regulation. SepN deficiency also leads to abnormal lung development characterized by enlarged alveoli, which is associated with decreased tissue elastance and increased quasi-static compliance of Sepn1−/− lungs. This finding raises the possibility that the respiratory syndrome observed in patients with SEPN1 mutations may have a primary pulmonary component in addition to the weakness of respiratory muscles.—Moghadaszadeh, B., Rider B. E., Lawlor, M. W., Childers, M. K., Grange, R. W., Gupta, K., Boukedes, S. S., Owen, C. A., Beggs, A. H. Selenoprotein N deficiency in mice is associated with abnormal lung development.

Keywords: selenium, multiminicore myopathy, ryanodine receptor, alveolar enlargement, SEPN1-related myopathy

As a member of the selenoprotein family, selenoprotein N (SepN) contains selenium in the form of the amino acid selenocysteine (Sec) (1). Sec residues provide highly reactive oxidation-reduction (redox) centers to proteins because they are ionized at physiological pH (2). To date, genes for 25 selenoproteins have been identified in the human genome (3), and most of the selenoproteins that have been functionally characterized are involved in redox reactions with the Sec residue being located at the catalytic site (4, 5). SepN is ubiquitously expressed as an integral protein of the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum, with a higher expression in early development (6, 7).

Mutations in the SEPN1 gene that encodes SepN account for a subset of myopathies that are clinically similar, but pathologically distinguishable, including congenital muscular dystrophy with spinal rigidity (8), the classical form of multiminicore disease (9), desmin-related myopathy with Mallory body-like inclusions (10), and congenital fiber-type disproportion (11). Despite the pathological variability, patients with mutations in the SEPN1 gene present with relatively homogenous clinical features, and are considered a single clinical entity referred to as SEPN1-related myopathies (SEPN1-RMs; ref. 12). Myoblasts and fibroblasts obtained from patients with mutations in SEPN1 show an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS; ref. 13), suggesting a role for SepN in maintaining the redox status of the muscle. Since SepN is located at the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane, it has been suggested that it might regulate the function of the ryanodine receptor (RyR) calcium release channels in muscle by affecting their redox status (14).

In the present study, we describe a novel Sepn1−/− mouse line as a model of SEPN1-RM. Sepn1−/− mice presented with a mild muscular phenotype. Remarkably, the most significant phenotype in these animals was abnormal lung development. In humans, SepN deficiency is associated with a respiratory insufficiency syndrome that has traditionally been attributed to the weakness of respiratory muscles. Our findings in murine lungs suggest that SepN deficiency might directly affect lung function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All studies were performed with approval from the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) at Boston Children's Hospital. Sepn1−/− mice were developed by inGenious Targeting Laboratory (iTL; Ronkonkoma, NY, USA). Briefly, a homologous recombination-based technique was used to replace with neomycin (Neo) cassette, a 222-bp region of the Sepn1 gene, including exon 9 and 114 and 2 bp of intronic regions upstream and downstream of exon 9, respectively. The targeting vector was confirmed by restriction analysis and sequencing after each modification step. The targeting vector (10 μg) was linearized by NotI and then transfected by electroporation of iTL IC1 C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells. Recombinant embryonic stem clones were selected with G418 antibiotic and identified by PCR analysis. Secondary confirmation was performed by Southern blotting analysis after digestion with EcoRI. The following primers were used to create a 593-bp probe targeted against the 5′ external region: PB3, 5′-CCATTGCGGAGAAACTGACAGGTAC-3′; and PB4, 5′-GTGCACTGACACACAGCCTG-3′. The expected sizes were 13.9 kb for wild-type (WT) and 8.9 kb for Sepn1−/−. Targeted iTL IC1 (C57BL/6) embryonic stem cells were microinjected into Balb/c blastocysts. Resulting chimeras with a high percentage of black coat color were mated to WT C57BL/6 mice to generate F1 heterozygous offspring. Tail DNA was used for genotyping PCR assay, which consisted of a standard touchdown PCR using the following 3 primers: F1, located in exon 8, AGGACGGCAACATGATTGACAG; R, located in intron 9, TTTGGCATTGTCTTCTAGGCTC; and F2, located in the Neo cassette, GGAACTTCGCTAGACTAGTACGCGTG. The expected sizes were 682 bp for WT and 209 bp for Sepn1−/− mice.

Mice were fed 3 types of diets. The regular diet provided by the animal facility was 5P00 Prolab RMH 3000 (Labdiet; PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO, USA). Vitamin E (VitE)-deficient diet (5D4P) contained only 0.7 IU/kg vitE, and control diet (5D4R) was identical to 5D4P in every aspect but contained 75 IU/kg vitE (TestDiet, Richmond, IN, USA). Mice that were fed either the control or the vitE-deficient diet were used in experiments involving spontaneous activity monitor, treadmill exercising, muscle fiber type determination, and histological staining. Regular diet was used in all the other experiments.

Western blots

Snap-frozen tissues were homogenized in M–PER buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), using 0.5-mm zirconium oxide beads in a bullet blender (Next Advance Inc., Averill Park, NY, USA). Protein homogenates were resolved on 4–12% bis/tris gels (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Transferred proteins were probed with antibodies against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 6C5, 1:10,000 dilution; Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA, USA), and cleaved caspase-3 (1:500 dilution; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). The antibody against SepN was custom made by Invitrogen by injecting rabbits with the peptide KEGLRRGLPLLQP, which corresponds to the last 13 aa of the human SepN. Crude serum from immunized rabbits (7637) was used at 1:500 dilution. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used as secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:10,000 in combination with SepN antibody and at 1:5000 in combination with caspase-3 antibody. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used at 1:10,000 dilution in combination with GAPDH antibody. Western blot membranes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence on a Chemidoc XRS imaging system (Bio-Rad). Quantification of protein levels normalized to GAPDH was performed using the program Quantity One 4.2.1 (Bio-Rad).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Snap-frozen tissues were homogenized with RNase-free 0.5-mm zirconium oxide beads in a bullet blender (Next Advance), and RNA was extracted using RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Extracted RNA was converted to cDNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) samples were prepared in a 10-μl reaction volume containing 100 ng of cDNA, 5 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 0.5 μl FAM-labeled TaqMan gene expression assay Mm01188437_m1, and 0.5 μl VIC-labeled 18S control probe (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was performed and analyzed using the 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and Real-Time PCR System Sequence Detection1.4 software. The relative amount of Sepn1 expression was first normalized to 18S RNA expression and was calculated as fold changes relative to the 3-wk-old WT lung.

Determination of ROS in mice tissues

Chloromethyl-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), which is an indicator of ROS, was used as described previously in tissue homogenates (15, 16) with a few modifications. Briefly, tissues were homogenized in 50 mM phosphate buffer and centrifuged at 16,000 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for protein quantification and ROS measurement. Tissue homogenate supernatant (40 μg, 150 μl) was transferred into a microplate, and 50 μl of 50 μM DCFDA was added to the protein homogenate. The plate was placed in a Synergy-2 microplate reader (BioteK, Winooski, VT, USA), and the fluorescence was measured after 90 min incubation with an excitation and emission wavelength set at 485 and 530 nm, respectively. ROS in each sample were normalized to protein concentration.

Enzymatic assays (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were used to measure the activity of glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and thioredoxin reductase in tissue homogenates of WT and Sepn1–/– mice, following manufacturer's instructions.

Assessing SR calcium release

SR calcium stores were studied as described previously (17), with a few modifications. Briefly, flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles from two 2-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− mice were extracted, and fiber bundles were visualized under a dissection microscope and dissociated physically and enzymatically (2 h treatment with collagenase at 37°C). Myofibers from each mouse were then plated in five 35-mm dishes coated with laminin (Trevigen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and cultured in DMEM supplemented by 20% FBS at 37°C. The following day, dishes were treated individually for the calcium assay using the fluo4-NW kit (Invitrogen-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, after 2 PBS washes, each dish was incubated for 15 min with 500 μl of HBSS solution containing Fluo-4 and 1.2 mM calcium. The dish was then placed under the microscope, and myofibers were visualized using a FITC filter. The camera was set to take a video of the chosen field for 5 min (an image was taken every 500 ms for a total of 600 images). After 10 s of recording the video, 100 mM caffeine and 1 μM N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide (BTS) were added to the dish. Caffeine induced a massive release of calcium from SR, while BTS inhibited the myofiber contraction that would normally occur on calcium release. Fluorescence signals from each myofiber were recorded on a Nikon microscope using NIS Element software (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA). The calcium release was calculated as (Fmax − Frest)/Frest. A total of 36 WT and 41 Sepn1−/− myofibers were studied. In another set of experiments, 63 WT and 42 Sepn1−/− FDB myofibers isolated from four 6-wk-old mice were treated with a mixture of 25 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and 1 μM BTS in calcium-free HBSS medium. Calcium release was visualized and measured as described above. Independent 2-tailed t tests were used to compare WT and Sepn1−/−.

Spontaneous activity monitor

An actimeter (LE8810; Harvard Apparatus, Holiston, MA, USA) was used to measure the spontaneous activity of the mice. The actimeter consisted of two horizontal infrared beams; one placed 3 cm above the bottom of the cage to detect movements, and one placed 7 cm above the bottom to detect rearing events. To encourage the animals to rear more often without the support of the cage walls, a piece of the food from the animal's usual food source was hung over the center of the cage at a height requiring full rearing and that would only be reached by the animal's nose. Each animal was placed in the activity monitor cage for 10 min, and the number of rearing events and traveled distance were quantified for that period of time.

Treadmill exercising

WT and Sepn1−/− mice (9 mo old) underwent a forced running exercise on a 2-channel mouse treadmill (AccuScan Instruments, Inc. Columbus, OH, USA) for 5 consecutive days before being euthanized. Exercises consisted of running 445 m over 50 min each day with increasing speed, as follows: 5 min at 5 m/min; 20 min at 8 m/min; 20 min at 10 m/min; and 5 min at 12 m/min. The last 4 min of the first running session was videotaped and analyzed. The number of times each mouse touched the electric bars in the back of the treadmill belt was used as a measure of fatigue.

Pathological evaluation and tissue collection

Animals were euthanized with CO2, followed by cervical dislocation, per the regulations of the IACUC at Boston Children's Hospital. The quadriceps, hamstring, gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), triceps, paraspinal, gluteus, and diaphragm muscles were removed and snap-frozen in isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen. Cross sections (8 μm) of isopentane-frozen muscles were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for gross histological evaluation. For NADH staining, frozen sections were incubated with nitro-blue tetrazolium (1 mg/ml) and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (0.4 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3) at 37°C for 30 min. Staining for myosin-ATPase was performed as described previously (18). Light microscopic images were captured using a SPOT Insight 4 Meg FW Color Mosaic camera and SPOT 4.5.9.1 software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI, USA) on a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope. For core quantification experiments, five 8-μm sections of TA muscle, each separated by 24 μm, were stained for NADH activity. To calculate the proportion of fibers containing cores, the total number of fibers containing cores was divided by the total number of NADH-positive fibers in all five sections. The proportion of core-containing fibers was compared between Sepn1−/− and WT groups using an independent 2-tailed t test.

For immunofluorescence studies, 8-μm frozen cross sections of quadriceps muscle were double stained as described previously (19) with rabbit anti-dystrophin antibody (ab15277, 1:100; Abcam) and mouse monoclonal antibodies against myosin heavy chain type 1 (Skeletal, Slow, clone NOQ7.5.4D, 1:100 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich) or type 2a (clone SC-71, 1:50 dilution) or 2b (clone BF-F3, 1:50 dilution; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA). Secondary antibodies included FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or IgM (both 1:100; Sigma-Aldrich) and AlexaFluor-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:50; Molecular Probes). Morphometric evaluation was performed as described previously (19).

For analysis of distal airspace size, immediately after euthanasia with CO2, a thoracotomy was performed, and the trachea was cannulated with a 22-gauge angiocatheter. The lungs were inflated with PBS to 25 cmH2O pressure, removed, and fixed in 10% saline-buffered formalin for 24 h. Midsagittal paraffin-embedded lung sections (8 μm) were stained with Gill's stain. For each mouse, images of 8 representative areas of stained lung sections were captured using a ×20 objective on a Nikon microscope. Scion Image software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD, USA) was used to measure mean alveolar chord length.

Ex vivo whole-muscle contractile studies

Immediately following euthanasia, the EDL and soleus muscles from WT or Sepn1−/− mice were carefully dissected, and 4-0 sutures were tied around the proximal and distal tendons. The muscles were placed into heated (30°C), oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Krebs Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4; K3753-1L; Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.2 g of calcium chloride and 1.8 g of sodium bicarbonate added per liter. Muscles were mounted onto a 4-channel Graz tissue bath apparatus (Harvard Apparatus) connected to a Powerlab data collection system using Chart 5 software (Harvard Apparatus). Muscles were stimulated by square pulses of 0.2 ms duration at a voltage and muscle length (L0) to elicit maximal isometric twitch force. The output stimulus was derived from a Hugo Sachs Elektronik type 215E13 voltage pulse generator (Harvard Apparatus) triggered at the desired frequency. Based on preliminary studies, the maximal isometric twitch response was elicited with a resting tension of 1.0 g and voltage set at 10 V. Each muscle was pretensioned to a force of 1 g and allowed to equilibrate for 10 min. Three test twitches at 1 Hz and 3 test tetanic contractions at 150 Hz were then performed to establish consistent contractile responses before any additional experimental procedures were performed. After an additional 10-min resting period, the muscle was subjected to a tension-frequency protocol at electrical stimulation frequencies of 1, 10, 20, 30, 50, 80, 100, 120, and 150 Hz, each spaced 1 min apart. The pretension force was reset to 1 g before each stimulus. The fatigue protocol consisted of 60 s of continuous stimulation at 60 and 100 Hz for EDL and soleus muscles, respectively. After completion of the tension-frequency protocol, the length of these muscles at a pretension of 1 g was measured, and the muscle tissue between the sutures was weighed after trimming off the suture and excess tissue. Estimated cross sectional area was calculated by dividing the mass of the muscle (g) by the product of its length (cm) and the density of muscle (1.06 g/cm3) (20) and expressed as square millimeters. Muscle output was expressed as stress (mN/mm2) determined by dividing force (mN) by muscle cross sectional area (mm2).

TUNEL assay

Apoptosis in lung sections was assessed by TUNEL assay using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Formalin-fixed lung sections were prepared from 1- and 3-mo-old mice as described above and were permeabilized with proteinase K. The TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei. Staining was evaluated using a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope using NIS Elements AR software. For each mouse, 3 representative fields were photographed using a ×40 objective, and TUNEL- and DAPI-positive nuclei were counted on each image. The number of apoptotic cells was assessed as the mean ratio of TUNEL-positive and DAPI-positive nuclei.

Respiratory mechanics

Ten 6-wk-old mice (5 WT and 5 Sepn1−/−) were used in this experiment. Respiratory mechanics were measured as described previously (21). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with a cocktail of 200 mg/kg body weight ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine, and 3 mg/kg acepromazine. A tracheostomy was performed, and an 18-gauge cannula was inserted and secured in the trachea using sutures. The animals were then connected via the cannula to a digitally controlled mechanical ventilator (FlexiVent device; Scireq, Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). Ventilator settings were f = 150/min, FiO2 = 0.21, tidal volume = 10 ml/kg body weight, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) = 3 cmH20. Mouse lungs were inflated to total lung capacity (TLC; 25 cmH2O) 3 times for volume history. Tissue resistance (G) and tissue elastance (H) at PEEP of 3 cmH2O were then measured, followed by stepwise quasi-static compliance (Cst) and volume-pressure curves.

RESULTS

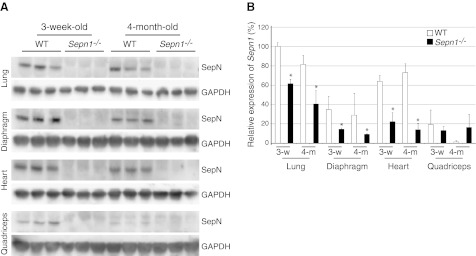

Sepn1−/− mice present no phenotype by gross examination

The Sec residue of SepN is encoded by exon 9 of both the human and murine genes. We developed a conventional knockout mouse model in which the Neo cassette replaced a 222-bp region of the mouse genome containing exon 9 of Sepn1. This results in a frame shift after aa 394, leading to a premature stop codon after residue 423. The resulting truncated protein is likely nonfunctional due to the absence of Sec, which usually is located at the catalytic site of selenoproteins. We confirmed the absence of the full-length protein in Sepn1−/− mice by Western blot, using protein isolated from different tissues (Fig. 1A). However, the antibody at our disposal was directed against the last 13 aa of SepN, and therefore this Western blot cannot determine whether the truncated polypetide corresponding to the first 8 exons is present or whether it is unstable and gets degraded. We did, however, confirm by qRT-PCR that the levels of Sepn1 transcript in most tissues of Sepn1−/− mice were significantly lower than those found in age-matched WT mice (Fig. 1B). This finding suggests that the deletion of exon 9 in Sepn1 results in the degradation of the mutant transcript through a nonsense-mediated decay pathway. Homozygous Sepn1−/− mice were viable and indistinguishable from WT animals by gross examination. Fifty-three litters obtained from heterozygous breeders resulted in 78 WT, 145 heterozygous Sepn+/−, and 78 homozygous Sepn1−/− animals, suggesting no developmental lethality for the latter. Homozygous Sepn1−/− mice could breed normally and produce normal size litters comparable to those found in WT × WT breeding (litter size: 23 Sepn1−/− litters, 7±2; 17 WT litters, 8±2.3; P>0.64). WT and Sepn1−/−animals had similar weights (at 3 mo: WT, 21.9±2.9 g; Sepn1−/−, 20.6±2.1 g; P>0.4).

Figure 1.

Confirmation of SepN deficiency by Western blot and qRT-PCR. A) Immunoblot showing the absence of SepN in the lung, diaphragm, heart, and quadriceps of Sepn1−/− mice. GAPDH was used as loading control. B) qRT-PCR of WT and Sepn1−/− corresponding to exon 2 of Sepn1 in lung, diaphragm, heart, and quadriceps. 18S RNA was used as internal control. Sepn1 expression in 3-wk-old WT mice was used as baseline. *P < 0.05.

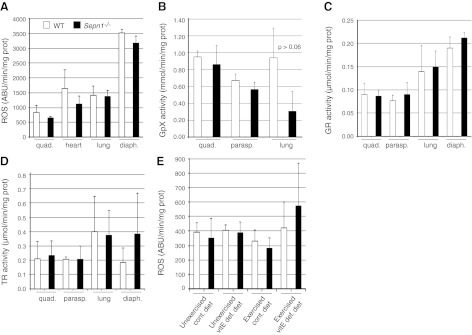

SepN-deficient mouse tissues do not show any changes in oxidation levels

Since most selenoproteins are involved in redox reactions, and SepN has been suggested to play a role in redox homoeostasis of the cell (13), we investigated whether a possible change occurred in oxidation levels of Sepn1−/− tissues, using CM-H2DCFDA as a fluorescent dye to detect ROS. As shown in Fig. 2A, the levels of ROS in quadriceps, heart, lung, and diaphragm were not significantly different between WT and Sepn1−/− mice. These data were confirmed by the observation of comparable levels of carbonylated proteins (marker of protein oxidation) and 4-hydroxynonenal-protein adducts (marker of lipid peroxidation) in WT and Sepn1−/− tissues (data not shown). We therefore measured the activity of key enzymes involved in detoxifying ROS, hypothesizing that an increase in the activity of these enzymes might compensate for any potential increase in ROS. Glutathione peroxidase reduces ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, while glutathione reductase and thioredoxin reductase reduce glutathione and thioredoxin, respectively, to provide reducing equivalents for peroxidase enzymes. We investigated the activity of these three enzymes in quadriceps, paraspinal muscle, lung, and diaphragm (Fig. 2B–D), but did not observe any significant difference between WT and Sepn1−/− tissues. This suggests that the absence of SepN is not associated with measurably increased oxidative stress in murine tissues.

Figure 2.

Quantification of oxidation in different tissues of WT and Sepn1−/− mice. A) ROS were measured in quadriceps of six 4-mo-old mice (3 WT and 3 Sepn1−/−), using CM-H2DCFDA as ROS indicator. B–D) Activity of glutathione peroxidase (B), glutathione reductase (C), and thioredoxin reductase (D) was measured in homogenates from quadriceps, paraspinal muscle, lung, and diaphragm of six 4-mo-old mice (3 WT and 3 Sepn1−/−), but no significant differences were found between WT and Sepn1−/− tissues. E) ROS were measured in quadriceps of 9-mo-old mice exposed to oxidative stress (7 WT and 7 Sepn1−/− mice for each condition). No significant difference was found in the amount of ROS between unstressed animals and those exposed to oxidative stress.

Induced oxidative stress leads to core lesions in SepN-deficient muscle

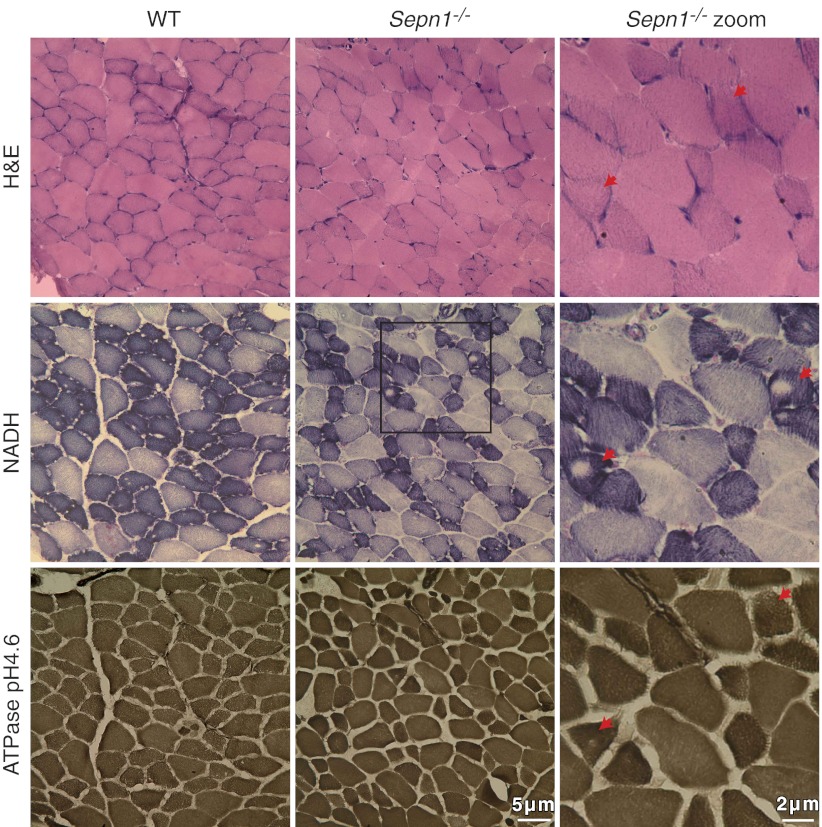

One of the most common pathological findings in patients with SEPN1 mutation is the presence of minicores, which correspond to areas of muscle depleted in mitochondria and characterized by a lack of staining of the mitochondrial enzyme NADH dehydrogenase. Histology of WT and Sepn1−/− muscles was assessed by H&E staining, and the presence of cores was investigated using NADH staining. WT and Sepn1−/− mouse muscles aged from 15 d to 1 yr showed no abnormalities, in particular, no core lesions. Although we did not observe any changes in oxidation levels of Sepn1−/− mouse tissues under baseline conditions, we hypothesized that inducing oxidative stress in these Sepn1−/− animals might exacerbate the effect of SepN deficiency and result in an observable phenotype. VitE is a powerful antioxidant that prevents the oxidation of lipids (22); therefore, to induce oxidative stress in the mice, we fed them a vitE-deficient diet for 8 mo starting at weaning, followed by 5 consecutive days of 50-min running sessions. No significant increase in ROS was detectable in quadriceps of either stressed WT or Sepn1−/− mice compared to their unstressed counterparts (Fig. 2E); however, few core lesions were visible in muscles of animals that underwent oxidative stress (Fig. 3).We quantified the number of cores in TA muscles by counting the number of NADH-positive fibers that contained cores. Table 1 shows the mean percentage of fibers with cores, based on the analysis of 5 TA sections for each mouse. While only a small proportion of fibers presented with core lesions, animals that were subjected to both vitE deficiency and running exercise showed the largest percentage of core-containing fibers (WT, 0.025±0.02; Sepn1−/−, 0.205±0.24). In this group of animals, Sepn1−/− TA sections had a significantly higher proportion of fibers containing cores compared to WT (P<0.04). We therefore concluded that oxidative stress caused by forced running and vitE deficiency, although transient and subtle, could lead to the manifestation of cores in muscle fibers. To better characterize the cores found in Sepn1−/− muscles, we stained serial sections of TA for NADH and myosin-ATPase activity (Fig. 3). NADH staining showed a few fibers containing core lesions and normal staining in these areas on myosin-ATPase stains characterized these areas as structured cores (i.e., mitochondrial distribution is affected but the organization of the contractile apparatus remains intact; ref. 23). Cores or core-like areas were not identified in the areas sampled for ultrastructural evaluation (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Muscle histology of WT and Sepn1−/− mice under oxidative stress at 9 mo of age. Serial sections of the TA muscle were stained with H&E, NADH, and ATPase (pH 4.6). Images with each stain were taken from the same area of the section, allowing the comparison of the same fibers with different staining methods. Right panel corresponds to a zoomed area from the middle panel. Red arrows indicate the myofibers that contain core lesions in NADH staining. Note that the same fibers do not present any cores with ATPase staining.

Table 1.

Percentage of muscle fibers containing cores in stressed and unstressed WT and Sepn1−/− mice

| Treatment group | WT | Sepn1−/− | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercised + vitE-deficient diet | 0.025 ± 0.02, n = 7 | 0.205 ± 0.24, n = 10 | 0.04 |

| Exercised + control diet | 0, n = 10 | 0.026 ± 0.04, n = 8 | 0.08 |

| Unexercised + vitE-deficient diet | 0.02 ± 0.02, n = 4 | 0, n = 4 | 0.18 |

| Unexercised + control diet | 0, n = 3 | 0, n = 3 | − |

Sepn1−/− mice exhibit fatigue resistance to forced running

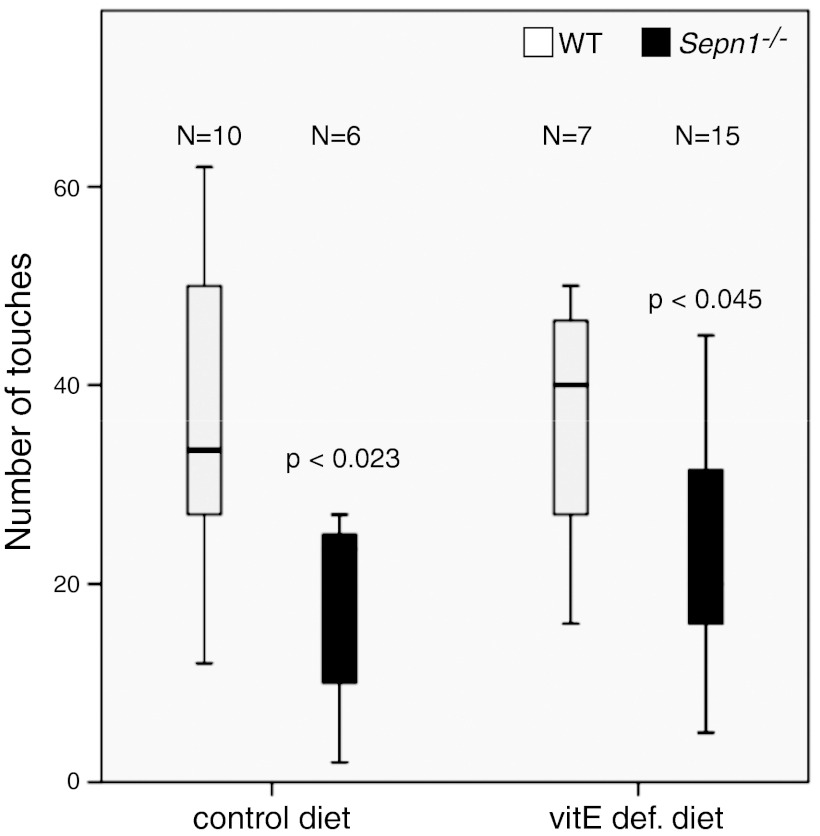

The primary goal of the running exercise described above was to subject the mice to an endurance type of exercise to study the effect of oxidative stress on the muscle. However, to have comparable treatment conditions, the exercise was set to an intermediate level of difficulty so that all the mice could complete each running session. We videotaped the last 4 min of the first running session to examine the running abilities of Sepn1−/− mice. We did not observe any obvious change in the way the mice were running; however, both WT and Sepn1−/− mice tended to touch the electric bars in the back of the treadmill belt as they were getting tired. As a measure of fatigue, we counted the number of times each mouse touched the electric bars. Remarkably, the Sepn1−/− animals touched the bars less often than WT animals both in control diet (P<0.023) and vitE-deficient diet (P<0.045) groups (Fig. 4), suggesting that SepN deficiency does not impair running abilities of the mice, and, in fact, it is associated with a slight fatigue-resistance phenotype in the context of forced running exercise.

Figure 4.

Quantification of running abilities. Mice (9 mo old) were fed either a control diet or a vitE-deficient diet and were subjected to a treadmill running session of 50 min for a total distance of 445 m. The last 4 min of the session was videotaped; as a measure of fatigue, the number of times each mouse touched the electric bars in the back of the treadmill belt was counted. Under both diets, the Sepn1−/− mice touched the bars less frequently, suggesting better running ability.

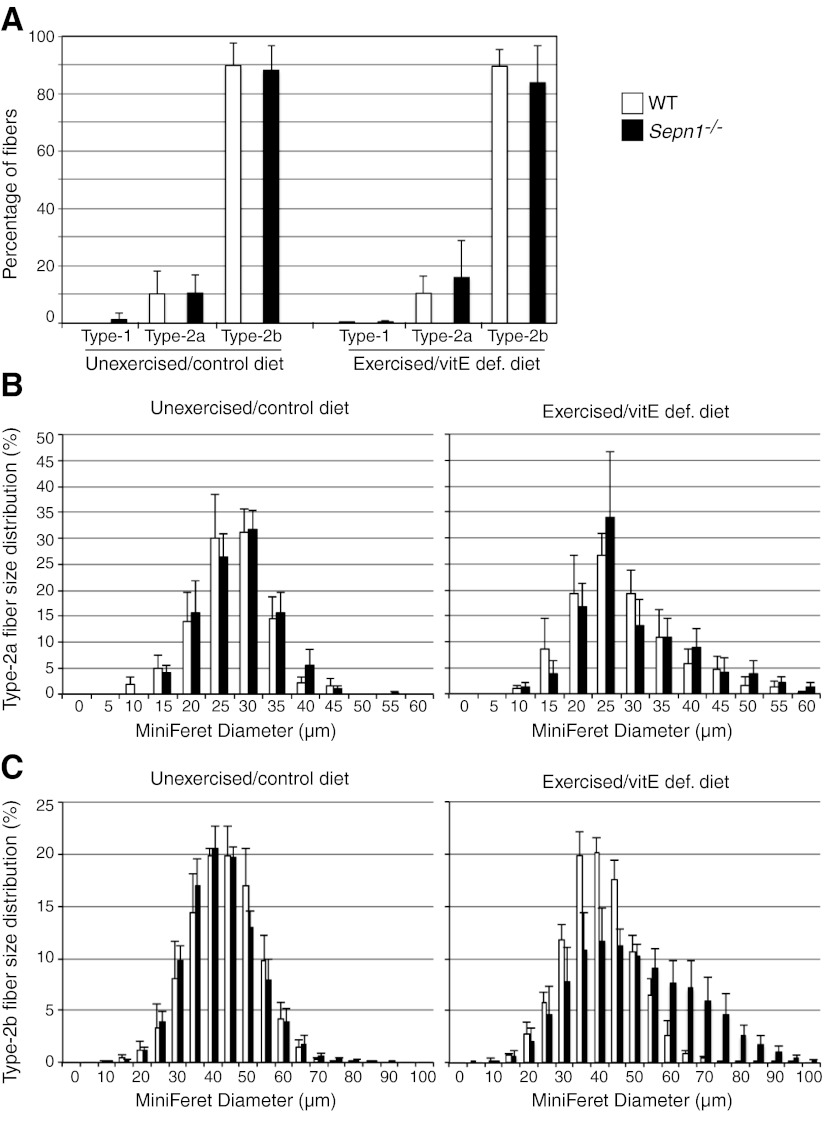

Sepn1−/− mice develop hypertrophy of type 2b myofibers in response to oxidative stress

We questioned whether the fatigue-resistance phenotype of Sepn1−/− mice could be explained by fast/slow fiber composition and/or the size of the fibers. To address this question, we quantified the proportion of type 1, 2a, and 2b fibers (Fig. 5A) in quadriceps of WT and Sepn1−/− animals by immunohistochemistry in unstressed and stressed (vitE deficiency + treadmill running) mice. Most limb muscles in adult mice (with the exception of the soleus) are predominantly composed of fast-twitch type 2b fibers; therefore, as expected, very few or no type 1 fibers were detected in our WT and Sepn1−/− quadriceps. In both stressed and unstressed groups, type 2a and 2b composed 10–15 and 85–90% of WT fibers, respectively. Similar proportions were found in Sepn1−/− fibers (Fig. 5A). When looking at the diameter of type 2a fibers, we observed no difference between WT and Sepn1−/− mice in both stressed and unstressed groups. Interestingly, when exposed to oxidative stress, type 2a fibers of both WT and Sepn1−/− mice shifted similarly toward larger size, indicative of myofiber hypertrophy (Fig. 5B). In the type 2b fiber population, however, hypertrophy was observed only in Sepn1−/− mice, with 31% of fibers being >60 μm, compared to only 4% in WT (Fig. 5C). This finding indicates that oxidative stress leads to hypertrophic type 2b fibers in Sepn1−/− mice. However, this cannot explain the improved fatigue-resistance of Sepn1−/− mice, because fatigue resistance was detected on the first day of running, prior to onset of myofiber hypertrophy.

Figure 5.

Quantification of size and proportion of different muscle fiber types. Immunostaining for dystrophin and myosin type 1, 2a, or 2b was performed in quadriceps muscles from 9-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− animals that were either unstressed (unexercised + control diet) or stressed (five 50-min treadmill sessions in 5 consecutive days + vitE deficiency since weaning). The different types of fibers were counted, and their MinFeret diameters were measured. A) Proportion of different fiber types. B) Type 2a fiber size as percentage of total number of 2a fibers. C) Type 2b fiber size as percentage of total number of 2b fibers.

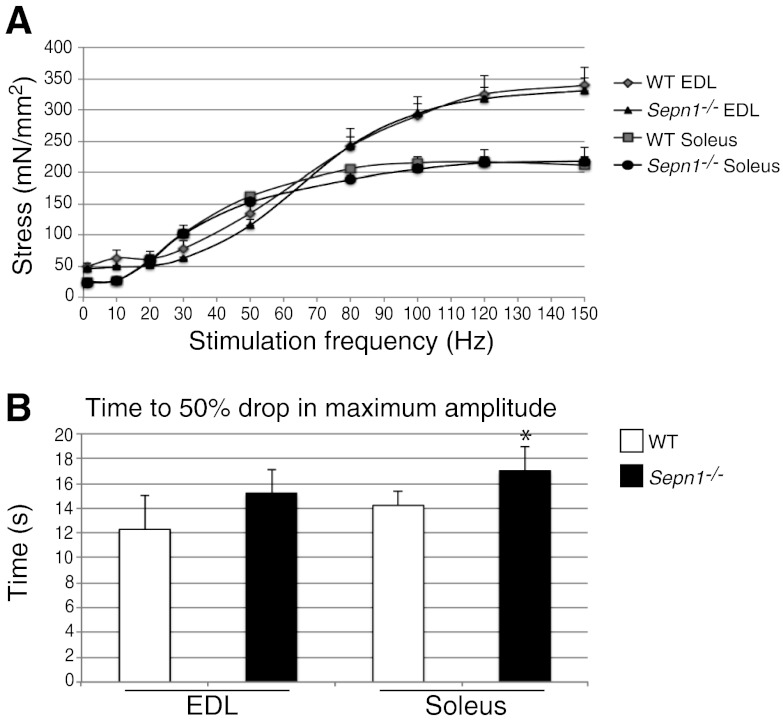

Isolated Sepn1−/− soleus muscle demonstrates increased fatigue resistance

Since the fiber type proportion and size could not explain the improved running ability of the Sepn1−/− mice, we studied the contractile properties of isolated EDL and soleus muscles in vitro. A tissue bath system was used to measure muscle tension at stimulation frequencies ranging from 1 to 150 Hz (Fig. 6A). EDL is composed of fast-twitch fibers, and the force it develops with increasing stimulation frequencies reached a plateau around 350 mN/mm2 of muscle in WT. Soleus, which is mostly composed of slow-twitch fibers, plateaued at 200 mN/mm2 of muscle. Remarkably, at every stimulation frequency, Sepn1−/− EDL and soleus responses were similar to those of WT muscles, suggesting that SepN deficiency does not affect the contractile function of either fast- or slow-twitch muscles. However, when testing the fatigue resistance of these muscles by 60 s of continuous stimulation, we observed a significantly longer time for stress to decrease to 50% of initial tetanic amplitude in Sepn1−/− soleus (17±1.9 s) compared to WT (14±1.2 s), which suggests that the Sepn1−/− soleus is more resistant to fatigue than its WT counterpart (Fig. 6B). The same trend was found in the EDL of Sepn1−/− and WT, but their difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Contractile function of isolated muscles. A) Isolated EDL and solei muscles from 4 untreated 4-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− mice were stimulated at frequencies ranging from 1 to 150 Hz. The resulting force was normalized to the size of each muscle and is reported on the graph. No significant differences were observed between WT and Sepn1−/− muscles. B) Isolated EDL and solei were stimulated for 60 s at 100 and 60 Hz respectively, to measure the fatigue in these muscles. Time to 50% drop in maximum amplitude of the contraction is shown. *P < 0.05.

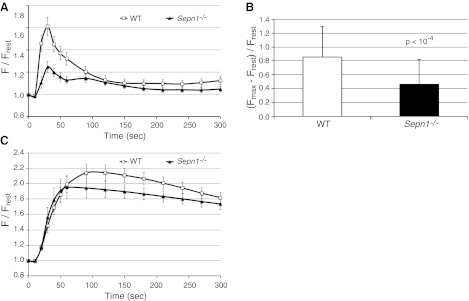

SepN deficiency decreases RyR sensitivity to caffeine

Certain mutations of the RyR gene (RYR1) have been shown to cause a muscle disease with pathological changes similar to those found in patients with SEPN1 mutations (24, 25). RyR is the major calcium release channel in the SR and is crucial for excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. In vitro studies on rabbit muscle have shown a physical interaction between SepN and RyR (14). Furthermore, changes in redox status of RyR have been shown to modulate its function (26), and therefore it has been hypothesized that SepN might be involved in calcium homoeostasis of the cell through the redox modulation of RyR (27). To test this hypothesis, we assessed the calcium store capacity of SR in WT and Sepn1−/− mice muscles ex vivo, using isolated myofibers obtained from FDB muscle. FDB is a very short muscle, which allows the dissection and culture of intact myofibers (28). Isolated FDB myofibers were loaded with the calcium indicator fluo-4, and stimulated with 100 mM caffeine, an efficient activator of RyR channel. The calcium release dynamic was similar in WT and Sepn1−/− myofibers on caffeine stimulation (Fig. 7A), but the amplitude of calcium release by Sepn1−/− myofibers (ΔF/Frest= 0.5±0.35) was significantly (P<10−4) lower when compared with WT (ΔF/Frest= 0.9±0.44) (Fig. 7B). To further investigate the effect of SepN deficiency on SR calcium release, FDB fibers were treated with CPA, which is an inhibitor of SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), resulting in an inhibition of calcium reuptake by SR and leading to an increase of cytosolic calcium. Interestingly, no significant difference was found between WT and Sepn1−/− myofibers in response to CPA in either dynamic or amplitude of calcium release (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that RyR channels in Sepn1−/− myofibers are less sensitive to caffeine, but SR calcium store is probably not altered.

Figure 7.

SR calcium release measurements in FDB myofibers. A) Measurement of calcium dynamics in FDB myofibers of WT and Sepn1−/− mice stimulated with caffeine. B) Comparison of maximum amplitude of calcium release between WT and Sepn1−/− myofibers, showing significantly reduced caffeine-activated calcium release in Sepn1−/− myofibers. C) Measurement of calcium dynamics in FDB myofibers of WT and Sepn1−/− mice stimulated with CPA. No significant difference was observed between WT and Sepn1−/− myofibers on CPA treatment, which suggests that SR calcium stores are not altered.

Sepn1−/− mice exhibit reduced spontaneous activity

In the context of forced exercise, we observed improved performance of Sepn1−/− mice. To compare the spontaneous activity of WT and Sepn1−/− animals, mice were observed during 10 min in a plexiglass activity monitor cage surrounded by two infrared frames. The lower frame allowed the measurement of mouse movements, while the upper frame allowed the quantification of rearing events. In a pilot study, we observed that the number of rearings seemed to be lower in Sepn1−/− mice. To further investigate rearing ability of the animals, a food pellet was hung over the center of the cage to encourage the mice to rear more often in the middle of the cage without the support of the cage walls. For this experiment, we used the same set of mice that was used to quantify core lesions in muscle. The exercised mice were subjected to 5 consecutive days of running for a total distance of 2225 m. These mice were placed in the activity monitor immediately before and after running on d 1, 3, and 5. Unexercised mice were studied in the same manner 3 times over 5 d, but they did not undergo any exercise. Among the different variables that were measured, the number of rearings and the total traveled distance seemed most relevant and are shown in Table 2. In unexercised WT and Sepn1−/− mice that were fed the control diet, no significant difference was found in the number of rearings and the distance traveled in the activity monitor. However, when fed a vitE-deficient diet, the WT mice were more active than Sepn1−/− animals, as indicated by a longer distance traveled (WT, 4260±731 cm; Sepn1−/−, 3209±796 cm; P<0.001) and increased number of rearings (WT, 131±27; Sepn1−/−, 100±42; P<0.03). It is noteworthy that this difference is not due to a decreased activity of Sepn1−/− animals but rather to an increased activity of the WT mice under vitE deficiency (Table 2). To look at the effect of treadmill training on the spontaneous activity of the mice, these variables were measured after 2 and 4 d of running (100 and 200 min cumulative exercise) followed by 24 h of rest (Table 2). Regardless of their genotypes, trained mice (100 or 200 min running) showed less spontaneous activity than their unexercised counterparts. When comparing WT and Sepn1−/− mice, there were again significant differences only under vitE deficiency. To look at the effect of fatigue on these mice, measurements were taken immediately after 50 min of exercise on d 1, 3, and 5 of running (cumulative running time of 50, 150, and 250 min; Table 2). The number of rearings and distance traveled by the exercised mice were significantly decreased compared to unexercised mice. When comparing the WT and Sepn1−/− within this group, once again, it appeared that there was only a significant difference in animals under vitE-deficient diet, and this difference was mainly due to more active WT mice.

Table 2.

Quantification of the spontaneous activity in WT and Sepn1−/− mice

| Diet | WT |

Sepn1−/− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rearing events | Distance (cm) | N | Rearing events | Distance (cm) | |

| Unexercised | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 138 ± 29 | 3321 ± 753 | 7 | 106 ± 42 | 3348 ± 509 |

| VitE-deficient | 11 | 131 ± 27 | 4260 ± 731 | 23 | 100 ± 42* | 3209 ± 796* |

| After 100 min exercise and 24 h rest | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 58 ± 26 | 2180 ± 696 | 7 | 63 ± 40 | 2218 ± 777 |

| VitE-deficient | 7 | 114 ± 25 | 3526 ± 686 | 15 | 52 ± 31* | 2258 ± 814* |

| After 200 min exercise and 24 h rest | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 72 ± 40 | 2323 ± 717 | 7 | 52 ± 18 | 2059 ± 545 |

| VitE-deficient | 7 | 96 ± 30 | 3039 ± 601 | 15 | 55 ± 34* | 2124 ± 817* |

| Immediately after 50 min exercise | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 59 ± 34 | 1942 ± 804 | 7 | 59 ± 36 | 2202 ± 1022 |

| VitE-deficient | 7 | 105 ± 40 | 2824 ± 437 | 15 | 58 ± 30* | 1759 ± 675* |

| 150 min cumulative exercise time, measured immediately after last 50 min | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 51 ± 28 | 1552 ± 852 | 7 | 67 ± 49 | 1928 ± 1031 |

| VitE-deficient | 7 | 102 ± 34 | 2695 ± 635 | 15 | 62 ± 39* | 1704 ± 654* |

| 250 min cumulative exercise time, measured immediately after last 50 min | ||||||

| Control | 10 | 71 ± 28 | 1895 ± 705 | 7 | 71 ± 34 | 2005 ± 989 |

| VitE-deficient | 7 | 98 ± 37 | 2567 ± 778 | 15 | 59 ± 33* | 1611 ± 775* |

Number of rearing events and traveled distance in the activity monitor cage were quantified and compared between WT and Sepn1−/− mice.

P < 0.05 vs. WT.

Sepn1−/− mice show abnormal lung development

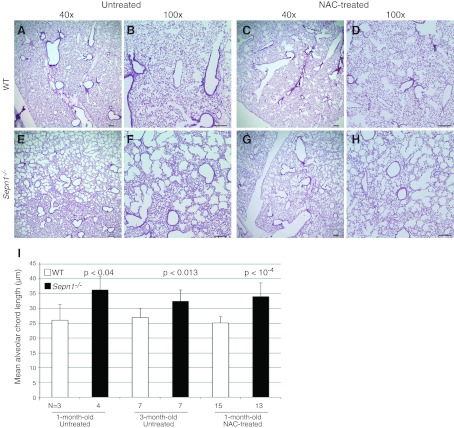

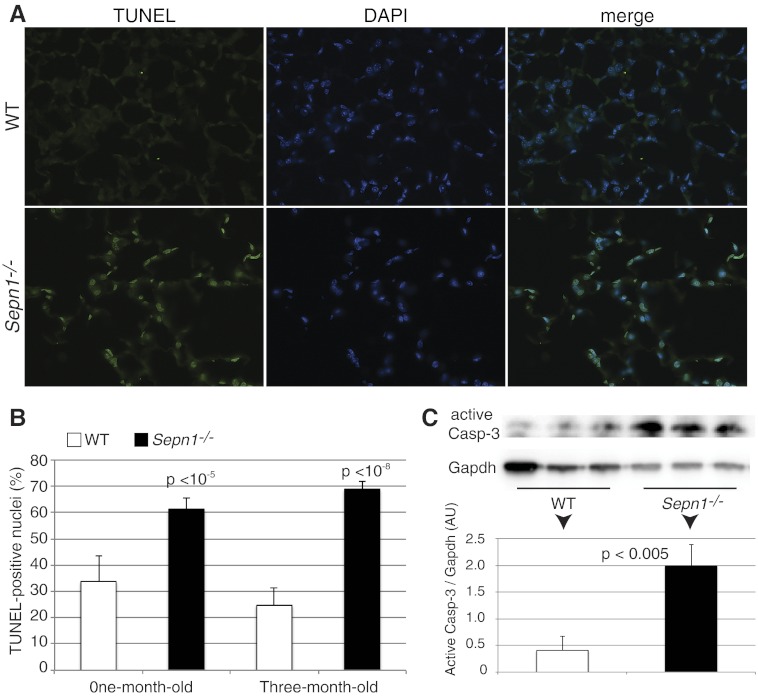

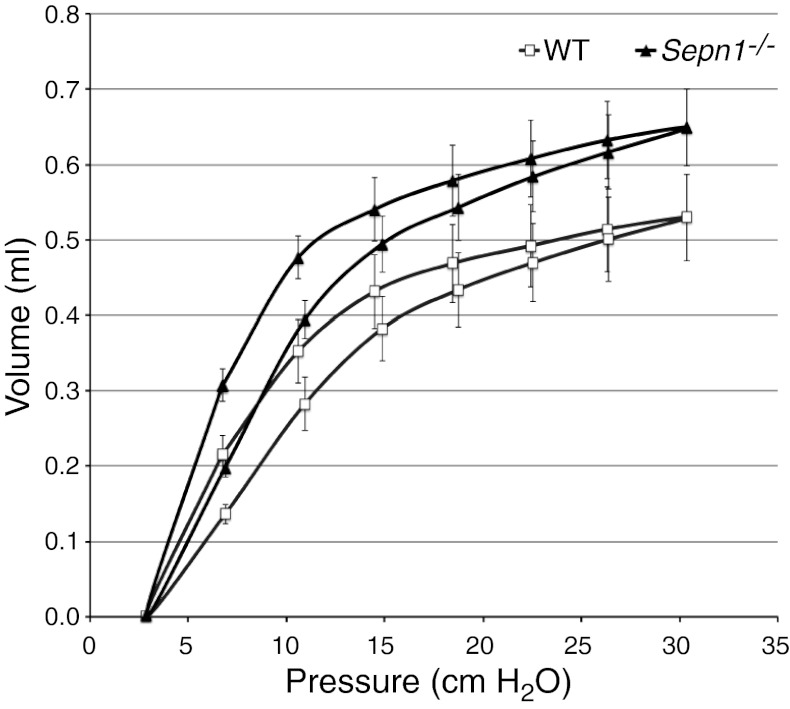

Even though mutations in SEPN1 cause primarily a muscle disease in humans, one cannot exclude the involvement of other tissues, especially since this protein has a ubiquitous expression (6, 7). When investigating the expression of Sepn1 in mice, we found that the highest expression of this gene both at RNA and protein levels was found in the lungs (Fig. 1). Therefore, we questioned whether Sepn1−/− mice might have a lung phenotype. Indeed, after examining various organs (lung, heart, brain, kidney, liver, spleen, ovary, and testicles), only the lungs showed abnormal histology in Sepn1−/− mice, characterized by enlarged alveoli (Fig. 8E, F). The alveolar spaces were quantified by measuring the mean alveolar chord length. Both 1- and 3-mo-old Sepn1−/− mice exhibited significantly increased mean alveolar chord lengths compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 8I). Interestingly, this phenotype was found in unstressed Sepn1−/− mice that were fed a regular diet and not subjected to any exercise. The same phenotype was found in animals submitted to oxidative stress (running + vitE-deficient diet) but was not more severe than the one observed in unstressed mice (data not shown). Since lung development in mice is complete around 10–12 wk of age, the presence of enlarged alveoli in animals as young as 1 mo is suggestive of abnormal lung development in Sepn1−/− mice. It has been shown that oxidative stress is a major contributor to alveolar destruction in adult mice with cigarette smoke-induced airspace enlargement (29, 30). Given the role of other selenoproteins in redox reactions, we hypothesized that the absence of SepN might result in the excessive oxidation of lungs and cause alveolar wall destruction and eventually lead to enlarged alveoli. We therefore treated heterozygous female breeders with 1% N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) in their drinking water 1 wk before starting the breeding and through the nursing period. The offspring continued to be treated with NAC throughout their lives and were euthanized at 3 mo of age; their lungs were studied as described above. NAC-treated Sepn1−/− animals showed the same magnitude of alveolar enlargement as untreated Sepn1−/−, suggesting that NAC supplementation did not prevent the abnormal lung development seen in Sepn1−/− animals (Fig. 8G–I). This result, taken together with the normal levels of ROS and normal activity of enzymes involved in pathways neutralizing ROS (Fig. 2), suggests no excessive oxidation in the lungs of Sepn1−/− animals and that SepN may not function as a ROS detoxifying enzyme in this physiological context. The enlargement of alveoli in murine models of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) usually occurs through the destruction of alveoli walls, which includes loss of alveolar epithelial and endothelial cells through the process of apoptosis (31). We investigated whether this is the case in Sepn1−/−; indeed, TUNEL staining of lung sections revealed an increase of 50% of TUNEL-positive nuclei in alveolar septal cells of Sepn1−/− mice compared to WT at both 1 and 3 mo of age (P<10−5 and P<10−8; Fig. 9A, B). This finding was also confirmed in lung homogenates by an increase in the activation of caspase-3, which is a marker of apoptosis (Fig. 9C). To test whether the alveolar enlargement observed in lung sections of Sepn1−/− mice was sufficient to cause abnormalities in respiratory mechanics in these animals, we compared tissue elastance and quasi-static lung compliance in 6-wk-old WT vs. Sepn1−/− mice in vivo, using a FlexiVent device. Sepn1−/− mice had reduced lung elasticity compared to WT lungs, as assessed by significantly lower H values (WT, 30.3±2.9 cmH2O/ml; Sepn1−/−, 21.8±1 cmH2O/ml; P<0.0002) and more compliant lungs, as assessed by significantly higher Cst values (WT, 0.047±0.004; Sepn1−/−, 0.063±0.007; P<0.002). Furthermore, compared with WT lungs, Sepn1−/− lungs had a left shift in their pressure-volume curves (Fig. 10). Thus, for a given pressure, the Sepn1−/− lungs inflated to a larger volume compared with WT lungs. Interestingly, baseline newtonian resistance (Rn), which reflects central airway resistance, was not significantly different between WT and Sepn1−/− lungs (WT, 0.38±0.1; Sepn1−/−, 0.42±0.1). These results demonstrate that SepN deficiency is associated with significant abnormalities in respiratory mechanics. Furthermore, the lung physiology results indicate that deficiency of SepN affects the distal airways (airspaces) rather than the proximal airways, which is consistent with our histological findings.

Figure 8.

Lung histology. A–H) H&E staining of lung sections from 3-mo-old WT (A–D) and Sepn1−/− (E–F) mice that were untreated (A, B, E, F) or NAC treated (C, D, G, H), viewed at ×40 (A, E, C, G),and ×100 (B, F, D, H). Scale bars = 20 μm. I) Quantification of alveolar chord length as a measure of alveolar enlargement in 1- and 3-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− mice.

Figure 9.

Measurement of apoptosis in WT and Sepn1−/− lungs. A) Representative images of TUNEL staining of 3-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− lung sections (left panel), corresponding nuclei stained with DAPI (middle panel), and merged image (right panel). B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive nuclei in the lungs of 1 and 3-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− mice. C) Levels of active caspase-3 were measured in lung homogenates using immunoblotting in 3-mo-old WT and Sepn1−/− lung homogenates, and the bands corresponding to caspase-3 were quantified and normalized to GAPDH.

Figure 10.

Quasi-static volume-pressure curves from 5 WT and 5 Sepn1−/− mice at 6 wk of life. Note the left shift of the volume-pressure curves in the Sepn1−/− animals, indicative of more compliant lungs in Sepn1−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

Although human SepN deficiency is associated with a primary muscle disease, we could not detect significant muscle weakness in unstressed Sepn1−/− mice. Interestingly, Sepn1−/− mice perform slightly better than WT animals in forced running exercises. This difference is not the result of exercise-induced changes, since fatigue measurements were performed on the first of the total of 5 running sessions, without prior training. Furthermore, the fact that Sepn1−/− animals subjected to vitE deficiency also performed better than WT littermates in forced running exercises, suggests that oxidative stress from vitE deficiency does not impair muscle performance in Sepn1−/− mice. However, spontaneous activity measurements revealed that WT mice were consistently more active than Sepn1−/− animals when subjected to vitE deficiency. Our behavioral and physiological data suggest that this difference may be due to behavioral alteration, rather than differences in muscle function. VitE is an essential nutrient that prevents the oxidation of lipids and its deficiency has been associated with neurological disease. Specifically, it has been shown that the lack of vitE is associated with an anxiety-related behavior in mice (32) and rats (33), which leads to altered open field activity in WT animals. It is remarkable that vitE deficiency does not affect the spontaneous activity of Sepn1−/− mice. This observation suggests that the response to increased oxidative stress consequent to vitE deficiency is altered by the absence of SepN.

The combination of 8 mo of vitE deficiency and 5 consecutive days of endurance running did not result in significant increase of ROS in either WT or Sepn1−/− muscles, suggesting that the induced oxidative stress was neutralized by antioxidant machinery of the cell. However, given the appearance of core lesions only in muscles of animals exposed to oxidative stress, it is conceivable that a local increase of ROS, probably too transient to be detected in our experiments, has contributed to the formation of core lesions. Although great heterogeneity was found among the cores detected in different animals, muscles of stressed Sepn1−/− animals showed significantly higher number of cores compared with their WT counterparts, suggesting that the SepN-deficient muscle is probably more prone to damage by oxidative stress. The neutralization of ROS in muscles of stressed animals and the overall small number of cores detected in Sepn1−/− animals exposed to oxidative stress suggests that more dramatic oxidative stress might result in more extensive core lesions. A recent study on another Sepn1−/− mouse model, lacking exon 3 of Sepn1, also showed that the unstressed Sepn1−/− mouse presents no macroscopic phenotype (34). However, a forced swimming test over a period of 3 mo resulted in spinal rigidity and reduced motility and formation of cytoplasmic inclusions in muscles, but no core lesions were detected in those Sepn1−/− mice. These results support our findings that Sepn1−/− mice develop a muscular phenotype only after undergoing physical stress. The fact that we observed core lesions in our Sepn1−/− mouse while cytoplasmic inclusions were detected in the other mouse model (34), could be explained by the type of stress that the mice were subjected to (running and vitE deficiency vs. forced swimming). Remarkably, Rederstorff et al. (34) reported a switch toward slower and smaller fibers in paravertebral muscles in exercised mice, with no changes in the quadriceps. In our study, we evaluated the quadriceps and did not observe any significant shift in the proportion of different fiber types, but both our WT and Sepn1−/− showed hypertrophy of type 2a fibers, while only Sepn1−/− animals displayed hypertrophy of 2b fibers when exposed to oxidative stress.

Two independent studies have reported zebrafish knockdown models of sepn1, showing abnormal sarcomeric organization of the muscle resulting in reduced motility of the fish (14, 35). The requirement of SepN for the normal function of RyR calcium release channels in zebrafish was further corroborated by the observation of physical interaction between SepN and RyR in rabbit muscle (14). In normal muscle, SERCA channels actively pump calcium from cytosol to SR, resulting in higher calcium concentration in SR compared to cytosol. On muscle excitation, calcium is released from SR to cytosol through RyR channels, resulting in the activation of myosin-ATPase and muscle contraction. Calcium is then pumped back to SR to prepare the muscle for the next cycle of contraction. In our study, we observed reduced SR calcium release in Sepn1−/− isolated myofibers on stimulation with caffeine, which could suggest lower SR calcium store in Sepn1−/− myofibers. However, treatment with the SERCA inhibitor CPA, resulted in similar calcium release in WT and Sepn1−/− myofibers, ruling out any changes in SR calcium store capacity. These results suggest that RyR channels in SepN-deficient muscles are less sensitive to caffeine in the context of our ex vivo experiments. Further studies are necessary to understand whether SepN regulates RyR function in physiological conditions.

Pulmonary emphysema in the adult lung is characterized by destruction of alveolar walls and enlargement of the distal airspaces. This is usually caused by 4 interrelated factors: oxidative stress; inflammation; protease-antiprotease imbalance, leading to destruction of the lung extracellular matrix; and apoptosis of alveolar septal cells (36–38). In the previous report of a Sepn1−/− murine model, there is no mention of a lung phenotype (34). Our Sepn1−/− model, however, displayed a strikingly abnormal lung phenotype, characterized by a robust increase in the size of the distal airspaces associated with increased rates of apoptosis of alveolar septal cells in the absence of lung inflammation. Interestingly, this phenotype develops in unchallenged Sepn1−/− animals in the absence of any induced oxidative stress and occurs during the first 4 wk of postnatal life. When we analyzed the mice at 3 mo of age, we did not observe any progression of the lung phenotype in the Sepn1−/−, and the increased rate of apoptosis of the alveolar septal cells persisted but was not significantly greater than the rate of septal cell apoptosis detected at 1 mo of age. It is possible that at 3 mo of age, compensatory mechanisms (such as proliferation of alveolar septal cells) increase in the Sepn1−/− lung and thereby prevent progression of the abnormal distal airspace size. We did not identify which alveolar septal cell types were undergoing apoptosis in the lungs of Sepn1−/− mice. These studies, and studies of the effects (if any) of SepN on the composition of the lung extracellular matrix will be future directions for our laboratory. As shown in Fig. 8, the severity of the lung pathology is somewhat heterogeneous and some areas of Sepn1−/− lungs are normal. Although the Sepn1−/− mice performed very well in treadmill running exercises, we questioned whether the enlargement of alveoli was associated with alterations in respiratory mechanics. In vivo respiratory mechanic assessment clearly demonstrated higher lung compliance and lower lung elasticity in the Sepn1−/− mice, correlating well with the pathological findings. This demonstrates that the alveolar enlargement associated with SepN deficiency leads to significant alterations in respiratory mechanics (consistent with airspace enlargement) but not to the extent that it impairs the exercise capacity of these animals.

Based on the involvement of other selenoproteins in redox reactions, one can hypothesize that SepN deficiency induces oxidative stress that results in increased apoptosis of alveolar septal cells in the lungs. However, this does not seem to be the case, since the measurement of ROS in lung homogenate samples showed similar levels in WT and Sepn1−/−. Furthermore, treatment of Sepn1−/− mice with NAC, which is a precursor of glutathione involved in detoxifying ROS in cells, did not rescue the lung phenotype in our Sepn1−/− mice. This finding suggests that the abnormal lung development in Sepn1−/− mice may not be caused by an increase in ROS generation in the lungs. However, it is conceivable that SepN deficiency might result in local increases in oxidative stress in alveolar septal cells that are sufficient to promote apoptosis of these cells but are too small and/or transient to be detected by our assays. Eight of the 25 selenoproteins in humans (including SepN) have been shown to be located at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ER lumen has a more oxidizing environment compared to the cytosol, enabling the folding and maturation of proteins transiting through the ER (39, 40). Several ER selenoproteins have been shown to play a role in the quality control of protein folding in the ER, and the deficiency of some of them results in ER stress (accumulation of unfolded protein; ref. 41). ER stress has also been associated with lung emphysema and, in some cases, can lead to alveolar enlargement through apoptosis of alveolar cells (42–44). Further studies are necessary to characterize the role of SepN in the ER; however, one can hypothesize that the Sec residue in SepN might play a role in redox reactions occurring during protein folding in the ER, and SepN deficiency might lead to an ER-stress-mediated apoptosis of lung cells. Patients with SEPN1 mutations present with weakness of mostly axial muscles and a respiratory insufficiency that has always been assumed to be due to respiratory muscle weakness (45). Although these muscles are likely to contribute to the respiratory difficulties seen in patients with SEPN1-RM, our findings in Sepn1−/− mice suggest that SepN deficiency might lead to a direct defect in lung architecture. Measurements of the severity of airspace enlargement in patients with pulmonary emphysema is usually performed using CT-scan analysis of lung density (46, 47), which involves exposure to radiation that is not always accepted by clinicians, especially in younger patients. However, in the light of this study, clinicians might be encouraged to investigate the involvement of the lungs in patients with SEPN1 mutations. There are currently studies in planning stages aiming at treating SEPN1-RM patients with NAC. Based on our findings and those of Rederstorff et al. (34), we hypothesize that NAC treatment might slightly improve the muscle phenotype, but the lack of improvement of lung phenotype in our mice suggests that patients might not see any beneficial effect regarding their respiratory syndrome, assuming that their condition is in part caused by abnormal lung development.

In summary, our results confirm previous studies showing that SepN-deficient mouse muscles are more susceptible to stress and that SepN plays a role in calcium homeostasis. Furthermore, our study indicates that deficiency in SepN leads to abnormal lung development in mice, a novel finding that has implications for patients with SEPN1 mutations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicholas Marinakis, Cynthia Hsu, Kiyomi Cho, and Kyle Schoppel for assistance with mouse experiments; Jennifer L. Cusick and Takahiro Nakajima for help with the analysis of lung sections, and Pankaj Agrawal and Vandana Gupta for their critical advice and assistance in performing enzyme and TUNEL assays. The authors also thank Suzanne White and Lena Liu (Histopathology Core Facility, Beth Israel Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA).

This work was supported by a generous grant from the Lee and Penny Anderson Family Foundation, and by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, grants R01 AR044345, K08 AR059750, R21 HL111835, and PO1 HL105339; the Muscular Dystrophy Association, grant MDA 201302; the William Randolph Hearst Foundation; and the BWH-Lovelace Respiratory Research Consortium.

Footnotes

- BTS

- N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide

- CM-H2DCFDA

- chloromethyl-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- CPA

- cyclopiazonic acid

- Cst

- quasi-static compliance

- EDL

- extensor digitorum longus

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- FDB

- flexor digitorum brevis

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H

- elastance

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- NAC

- N-acetyl cysteine

- Neo

- neomycin

- PEEP

- positive end-expiratory pressure

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- Sec

- selenocysteine

- SEPN1-RM

- SEPN1-related myopathy

- SepN

- selenoprotein N

- SERCA

- sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- SR

- sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TA

- tibialis anterior

- TLC

- total lung capacity

- vitE

- vitamin E

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Lescure A., Gautheret D., Carbon P., Krol A. (1999) Novel selenoproteins identified in silico and in vivo by using a conserved RNA structural motif. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 38147–38154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacob C., Giles G. I., Giles N. M., Sies H. (2003) Sulfur and selenium: the role of oxidation state in protein structure and function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 4742–4758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kryukov G. V., Castellano S., Novoselov S. V., Lobanov A. V., Zehtab O., Guigo R., Gladyshev V. N. (2003) Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science 300, 1439–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behne D., Kyriakopoulos A. (2001) Mammalian selenium-containing proteins. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 21, 453–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moghadaszadeh B., Beggs A. H. (2006) Selenoproteins and their impact on human health through diverse physiological pathways. Physiology (Bethesda) 21, 307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petit N., Lescure A., Rederstorff M., Krol A., Moghadaszadeh B., Wewer U. M., Guicheney P. (2003) Selenoprotein N: an endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein with an early developmental expression pattern. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1045–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castets P., Maugenre S., Gartioux C., Rederstorff M., Krol A., Lescure A., Tajbakhsh S., Allamand V., Guicheney P. (2009) Selenoprotein N is dynamically expressed during mouse development and detected early in muscle precursors. BMC Dev. Biol. 9, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moghadaszadeh B., Petit N., Jaillard C., Brockington M., Roy S. Q., Merlini L., Romero N., Estournet B., Desguerre I., Chaigne D., Muntoni F., Topaloglu H., Guicheney P. (2001) Mutations in SEPN1 cause congenital muscular dystrophy with spinal rigidity and restrictive respiratory syndrome. Nat. Genet. 29, 17–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferreiro A., Quijano-Roy S., Pichereau C., Moghadaszadeh B., Goemans N., Bonnemann C., Jungbluth H., Straub V., Villanova M., Leroy J. P., Romero N. B., Martin J. J., Muntoni F., Voit T., Estournet B., Richard P., Fardeau M., Guicheney P. (2002) Mutations of the selenoprotein N gene, which is implicated in rigid spine muscular dystrophy, cause the classical phenotype of multiminicore disease: reassessing the nosology of early-onset myopathies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 739–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferreiro A., Ceuterick-de Groote C., Marks J. J., Goemans N., Schreiber G., Hanefeld F., Fardeau M., Martin J. J., Goebel H. H., Richard P., Guicheney P., Bonnemann C. G. (2004) Desmin-related myopathy with Mallory body-like inclusions is caused by mutations of the selenoprotein N gene. Ann. Neurol. 55, 676–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clarke N. F., Kidson W., Quijano-Roy S., Estournet B., Ferreiro A., Guicheney P., Manson J. I., Kornberg A. J., Shield L. K., North K. N. (2005) SEPN1: associated with congenital fiber-type disproportion and insulin resistance. Ann Neurol. 59, 546–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schara U., Kress W., Bonnemann C. G., Breitbach-Faller N., Korenke C. G., Schreiber G., Stoetter M., Ferreiro A., von der Hagen M. (2008) The phenotype and long-term follow-up in 11 patients with juvenile selenoprotein N1-related myopathy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 12, 224–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arbogast S., Beuvin M., Fraysse B., Zhou H., Muntoni F., Ferreiro A. (2009) Oxidative stress in SEPN1-related myopathy: from pathophysiology to treatment. Ann. Neurol. 65, 677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jurynec M. J., Xia R., Mackrill J. J., Gunther D., Crawford T., Flanigan K. M., Abramson J. J., Howard M. T., Grunwald D. J. (2008) Selenoprotein N is required for ryanodine receptor calcium release channel activity in human and zebrafish muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 12485–12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paraidathathu T., de Groot H., Kehrer J. P. (1992) Production of reactive oxygen by mitochondria from normoxic and hypoxic rat heart tissue. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 13, 289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koike K., Kondo Y., Sekiya M., Sato Y., Tobino K., Iwakami S. I., Goto S., Takahashi K., Maruyama N., Seyama K., Ishigami A. (2010) Complete lack of vitamin C intake generates pulmonary emphysema in senescence marker protein-30 knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 298, L784–L792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Summermatter S., Thurnheer R., Santos G., Mosca B., Baum O., Treves S., Hoppeler H., Zorzato F., Handschin C. (2012) Remodeling of calcium handling in skeletal muscle through PGC-1alpha: impact on force, fatigability, and fiber type. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 302, C88–C99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Round J. M., Matthews Y., Jones D. A. (1980) A quick, simple and reliable histochemical method for ATPase in human muscle preparations. Histochem. J. 12, 707–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lawlor M. W., Read B. P., Edelstein R., Yang N., Pierson C. R., Stein M. J., Wermer-Colan A., Buj-Bello A., Lachey J. L., Seehra J. S., Beggs A. H. (2011) Inhibition of activin receptor type IIB increases strength and lifespan in myotubularin-deficient mice. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 784–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mendez J., Keys A. Density and composition of mammalian muscle. Metabolism 9, 184–188 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quintero P. A., Knolle M. D., Cala L. F., Zhuang Y., Owen C. A. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinase-8 inactivates macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha to reduce acute lung inflammation and injury in mice. J. Immunol. 184, 1575–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Traber M. G., Sies H. (1996) Vitamin E in humans: demand and delivery. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 16, 321–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neville H. (1973) Central core fibers: structured and unstructured. In Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Muscle Diseases (Kakulas B. A., ed) Vol. 1, pp. 497–511, Excerpta Medica, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreiro A., Monnier N., Romero N. B., Leroy J. P., Bonnemann C., Haenggeli C. A., Straub V., Voss W. D., Nivoche Y., Jungbluth H., Lemainque A., Voit T., Lunardi J., Fardeau M., Guicheney P. (2002) A recessive form of central core disease, transiently presenting as multi-minicore disease, is associated with a homozygous mutation in the ryanodine receptor type 1 gene. Ann. Neurol. 51, 750–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Treves S., Jungbluth H., Muntoni F., Zorzato F. (2008) Congenital muscle disorders with cores: the ryanodine receptor calcium channel paradigm. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aracena-Parks P., Goonasekera S. A., Gilman C. P., Dirksen R. T., Hidalgo C., Hamilton S. L. (2006) Identification of cysteines involved in S-nitrosylation, S-glutathionylation, and oxidation to disulfides in ryanodine receptor type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40354–40368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arbogast S., Ferreiro A. (2010) Selenoproteins and protection against oxidative stress: selenoprotein N as a novel player at the crossroads of redox signaling and calcium homeostasis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ravenscroft G., Nowak K. J., Jackaman C., Clement S., Lyons M. A., Gallagher S., Bakker A. J., Laing N. G. (2007) Dissociated flexor digitorum brevis myofiber culture system–a more mature muscle culture system. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 64, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rahman I., Biswas S. K., Kode A. (2006) Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airway diseases. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 533, 222–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boutten A., Goven D., Boczkowski J., Bonay M. (2010) Oxidative stress targets in pulmonary emphysema: focus on the Nrf2 pathway. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 14, 329–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kasahara Y., Tuder R. M., Taraseviciene-Stewart L., Le Cras T. D., Abman S., Hirth P. K., Waltenberger J., Voelkel N. F. (2000) Inhibition of VEGF receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 1311–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Desrumaux C., Risold P. Y., Schroeder H., Deckert V., Masson D., Athias A., Laplanche H., Le Guern N., Blache D., Jiang X. C., Tall A. R., Desor D., Lagrost L. (2005) Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) deficiency reduces brain vitamin E content and increases anxiety in mice. FASEB J. 19, 296–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okura Y., Tawara S., Kikusui T., Takenaka A. (2009) Dietary vitamin E deficiency increases anxiety-related behavior in rats under stress of social isolation. BioFactors 35, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rederstorff M., Castets P., Arbogast S., Laine J., Vassilopoulos S., Beuvin M., Dubourg O., Vignaud A., Ferry A., Krol A., Allamand V., Guicheney P., Ferreiro A., Lescure A. (2011) Increased muscle stress-sensitivity induced by selenoprotein N inactivation in mouse: a mammalian model for SEPN1-related myopathy. PLoS One 6, e23094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Deniziak M., Thisse C., Rederstorff M., Hindelang C., Thisse B., Lescure A. (2007) Loss of selenoprotein N function causes disruption of muscle architecture in the zebrafish embryo. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 156–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fishman A. P., Elias J. A. (2008) Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, McGraw-Hill Medical, New York [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fischer B. M., Pavlisko E., Voynow J. A. (2011) Pathogenic triad in COPD: oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and inflammation. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 6, 413–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aoshiba K., Yokohori N., Nagai A. (2003) Alveolar wall apoptosis causes lung destruction and emphysematous changes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 28, 555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sitia R., Molteni S. N. (2004) Stress, protein (mis)folding, and signaling: the redox connection. Sci STKE 2004, pe27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malhotra J. D., Kaufman R. J. (2007) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress: a vicious cycle or a double-edged sword? Antioxid. Redox Signaling 9, 2277–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shchedrina V. A., Zhang Y., Labunskyy V. M., Hatfield D. L., Gladyshev V. N. (2010) Structure-function relations, physiological roles, and evolution of mammalian ER-resident selenoproteins. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 12, 839–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tagawa Y., Hiramatsu N., Kasai A., Hayakawa K., Okamura M., Yao J., Kitamura M. (2008) Induction of apoptosis by cigarette smoke via ROS-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-homologous protein (CHOP). Free Rad. Biol. Med. 45, 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malhotra D., Thimmulappa R., Vij N., Navas-Acien A., Sussan T., Merali S., Zhang L., Kelsen S. G., Myers A., Wise R., Tuder R., Biswal S. (2009) Heightened endoplasmic reticulum stress in the lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of Nrf2-regulated proteasomal activity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 180, 1196–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44. Geraghty P., Wallace A., D'Armiento J. M. (2011) Induction of the unfolded protein response by cigarette smoke is primarily an activating transcription factor 4-C/EBP homologous protein mediated process. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 6, 309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scoto M., Cirak S., Mein R., Feng L., Manzur A. Y., Robb S., Childs A. M., Quinlivan R. M., Roper H., Jones D. H., Longman C., Chow G., Pane M., Main M., Hanna M. G., Bushby K., Sewry C., Abbs S., Mercuri E., Muntoni F. (2011) SEPN1-related myopathies: clinical course in a large cohort of patients. Neurology 76, 2073–2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dirksen A. (2008) Is CT a new research tool for COPD? Clin. Respir. J. 2(Suppl. 1), 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grydeland T. B., Dirksen A., Coxson H. O., Eagan T. M., Thorsen E., Pillai S. G., Sharma S., Eide G. E., Gulsvik A., Bakke P. S. (2010) Quantitative computed tomography measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness are related to respiratory symptoms. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]