Abstract

A large body of evidence for G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) oligomerization has accumulated over the past 2 decades. The smallest of these oligomers in vivo most likely is a dimer that buries 1000-Å2 intramolecular surfaces and on stimulation forms a complex with heterotrimeric G protein in 2:1 stoichiometry. However, it is unclear whether each of the monomers adopts the same or a different conformation and function after activation of this dimer. With bovine rhodopsin (Rho) and its cognate bovine G-protein transducin (Gt) as a model system, we used the retinoid chromophores 11-cis-retinal and 9-cis-retinal to monitor each monomer of the dimeric GPCR within a stable complex with nucleotide-free Gt. We found that only 50% of Rho* in the Rho*-Gt complex is trapped in a Meta II conformation, while 50% evolves toward an opsin conformation and can be regenerated with 9-cis-retinal. We also found that all-trans-retinal can regenerate chromophore-depleted Rho*e complexed with Gt and FAK*TSA peptide containing Lys296 with the attached all-trans retinoid (m/z of 934.5[MH]+) was identified by mass spectrometry. Thus, our study shows that each of the monomers contributes unequally to the pentameric (2:1:1:1) complex of Rho dimer and Gt heterotrimer, validating the oligomeric structure of the complex and the asymmetry of the GPCR dimer, and revealing its structural/functional signature. This study provides a clear functional distinction between monomers of family A GPCRs in their oligomeric form.—Jastrzebska, B., Orban, T., Golczak, M., Engel, A., Palczewski, K. Asymmetry of the rhodopsin dimer in complex with transducin.

Keywords: G-protein-coupled receptor, heterotrimeric G protein, retinoids, retinal isomerization, membrane protein

Insights into the molecular architecture of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and their activation mechanisms have been gained steadily over the past 2 decades. These were derived initially from secondary structure predictions of GPCR overall topology (1, 2), through low-resolution 3-dimensonal structures (3) and then structures of native crystallized rhodopsin (Rho; ref. 4), photoactivated Rho (Rho*), and ligand-free and chromophore-bound opsin (5–9). This steady progress was complemented recently by various constructs in the presence of agonists and antagonists of thermostabilized receptors (10) and the fusion of modified GPCRs and fast folding soluble proteins (11).

GPCRs form homo- and heterodimeric and oligomeric structures (12) identified by imaging of native membranes (13, 14). Moreover, obligatory heterodimeric functional expression was documented primarily for family C GPCRs that contain large N-terminal domains (15). For the largest family A of GPCRs, however, the situation is more complex. Purified family A monomeric receptors can activate G proteins, both alone and when reconstituted into nanodiscs, where they apparently retain a monomeric structure (16, 17). However, lack of direct organizational proof complicates the interpretation of these last experiments. The nature of their diffusible ligands and rather crude assays employed lacked the sensitivity to distinguish between different oligomeric states, particularly because oligomers could rapidly form and break apart (18). Nonetheless, transgenic mouse experiments (19, 20), electron microscopic studies (21, 22), and some crystallographic structures (7, 23) support a vast number of different biochemical assays and spectroscopic approaches (24–26) indicating that family A GPCRs have an intrinsic propensity to dimerize/oligomerize.

The family A GPCR Rho has been a model for G-protein signaling for decades (27). This membrane protein has also offered opportunities to advance the structural and functional understanding of GPCR oligomerization. Thus, Rho photoactivated states can be readily monitored spectrophotometrically because inactive Rho with its 11-cis-retinylidene chromophore absorbs around 500 nm, whereas Rho*, the so-called metarhodopsin II (Meta II) formed in the all-trans-retinylidene configuration, absorbs at ∼380 nm (28). After chromophore release from Rho*, the resulting opsin can be recharged physiologically with 11-cis-retinal to regenerate light-sensitive Rho (24), or with the 9-cis-retinal analog to form isorhodopsin (isoRho), which absorbs at 485 nm (29). The isomeric state of chromophore can also be chemically analyzed after rapid hydrolysis with hydroxylamine in ethanolic solution and separation of the retinal isomers by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). In native membranes, all-trans-retinylidene is hydrolyzed, and all-trans-retinal slowly released from the binding pocket is recycled back to the 11-cis conformation by a series of enzymatic reactions termed the retinoid cycle. Notably, depletion of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and guanosine diphosphate (GDP) stabilizes the complex between Rho and its cognate G-protein transducin (Gt) for biochemical manipulation (30). Visualization of Rho*-Gt complexes with (unpublished results) and without the succinylated lectin, succinylated concanavalin A (sConA; ref. 21, 31) unequivocally indicates a pentameric assembly of the Rho*-Gt complex in which the photoactivated Rho dimer serves as a platform for binding the Gt heterotrimer, as predicted previously (32). The pentameric nature of this Rho*-Gt complex reveals that each Rho monomer in the complex must be differently arranged in its interaction with Gt. However, it is unclear whether the Rho monomers have separate functions in the pentameric complex. In this study, we demonstrate that photoactivated dimeric Rho is structurally and functionally in an asymmetric state in the Rho*-Gt complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) and 9-cis-retinal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) was obtained from Affymetrix (Maumee, OH, USA). Bradford Ultra was purchased from Novexin (Cambridge, UK). 11-cis-retinal was a generous gift from Dr. R. Crouch (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA). All-trans-retinal was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada).

Purification of Rho

Bovine rod outer segment (ROS) membranes were prepared from fresh retinas under dim red light, as described previously (33). These were solubilized in DDM and used for Rho purification by a ZnCl2-opsin precipitation method (34). ZnCl2 was removed by a 48-h dialysis in the presence of 0.2 mM DDM. Rho concentrations were measured with a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Cary 50; Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and quantified by using the absorption coefficient ε500nm = 40,600 M−1 cm−1 (35).

Purification of Gt

Gt was purified after extraction with hypotonic buffer from ROS membranes isolated from 200 dark-adapted bovine retinas as described previously (36). Briefly, ROS membranes were resuspended in 30 ml of isotonic buffer, composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 100 mM NaCl, and soluble proteins were removed by gentle homogenization, followed by centrifugation at 25,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. Gt was extracted from the pellet by 3 washes with 30 ml of hypotonic buffer, composed of 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT; membranes were pelleted after each wash by centrifugation at 25,000 g at 4°C for 30 min. All 3 wash supernatants were combined and centrifuged at 25,000 g for 60 min to remove remaining ROS membrane contaminants. Then 1 M HEPES (pH 7.5) was added to the final supernatant to reach a final concentration of 10 mM, and MgCl2 was added to achieve a 2 mM final concentration. The resulting sample in this equilibrating buffer was applied at a flow rate of 15 ml/h to a 10- × 100-mm column loaded with 5 ml of preequilibrated pentyl-agarose resin, and the column was washed with 10 column vol of equilibrating buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with a 50-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in the equilibrating buffer at a flow rate of 15 ml/h, and 1-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing Gt were pooled and concentrated by 30,000 normal molecular weight limit (NMWL) Centricon devices (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Gt was purified to homogeneity on a tandem Superdex 200 gel filtration column equilibrated with buffer composed of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT at 4°C (flow rate 0.4 ml/min with collection of 0.5 ml fractions). Fractions containing Gt were combined and concentrated by 30,000 NMWL Centricon devices (Millipore) to ∼10 mg protein/ml, as determined by the Bradford assay (37).

Purification and regeneration of Rho*-Gt and Rho*e-Gt complexes

The Rho*-Gt complex was purified by sConA affinity chromatography, as described previously (21). Briefly, the sConA affinity resin was prepared by coupling sConA (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) to CNBr-activated agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a density of 8 mg sConA/ml of resin. Purified Rho (200 μg) was diluted to ∼0.2 mg/ml and loaded onto the sConA column (400 μl) equilibrated with an equilibrating buffer (20 mM BTP, pH 6.9, containing 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM DDM). The resin was washed with 5 column vol of the same buffer and then illuminated for 10 min with a 150-W fiber light (Dolan Jenner Industries, Boxborough, MA, USA) delivered through a 480- to 520-nm bandpass filter. Purified native Gt (200 μg), diluted to ∼0.2 mg/ml with this equilibrating buffer, was applied to the column immediately after light exposure. Excess Gt was washed out with 10 column vol of the above buffer. To obtain the chromophore-depleted Rho*-Gt (Rho*e-Gt) complex, the Rho*-Gt complex bound to the column was first washed with 40 mM NH2OH in the equilibrating buffer. Excess NH2OH was washed out with 10 column vol of the equilibration buffer. Then Rho*-Gt or Rho*e-Gt complexes were either eluted from the column with the elution buffer (equilibration buffer containing 200 mM α-methyl-d-mannoside) or regenerated with a specified retinoid.

Alternatively, Rho itself was bound to the sConA affinity resin, and opsin was generated by light illumination (as described above), followed by a prolonged wash (200 column vol) with the equilibrating buffer, and eluted with the elution buffer. Opsin concentration was determined from its absorption at 280 nm using the extinction coefficient ε = 81,200 M−1 cm−1 (38).

Regeneration of Rho*-Gt and Rho*e-Gt complexes and opsin

To regenerate Rho*-Gt, Rho*e-Gt or opsin, a 2-fold molar excess of either 9-cis-retinal, 11-cis-retinal, or all-trans-retinal was used (see Results). An ethanolic solution of the selected retinoid diluted with equilibration buffer (final ethanol concentration <1%) was loaded on a column with specific bound complexes. The column then was closed for 1 h and kept at 4°C in the dark. Excess retinal then was washed out with 10 column vol of equilibrating buffer, and proteins were eluted. Fractions containing either Rho*-Gt, Rho*e-Gt, or chromophore-regenerated complexes were used for spectral analyses by UV absorption and/or biochemical analysis of retinoid components.

UV-visible spectroscopy

UV-visible absorption spectra of purified Rho*-Gt, Rho*e-Gt, or complexes regenerated with either all-trans-retinal, 9-cis-retinal, or 11-cis-retinal were measured at 20°C with a Cary 50 Varian spectrophotometer. To determine the presence of a Schiff base linkage vs. free retinal in the Rho*e-Gt complex regenerated with all-trans-retinal, we acidified the sample with H2SO4 to a final pH of 1.9. Retinylidene-lys296 has an absorption peak at 440 nm, whereas maximum absorption of free retinal is at 365 nm (39, 40).

Fluorescence measurements

A 2-fold molar excess of 11-cis-retinal or all-trans-retinal was added to freshly purified Rho*e-Gt or opsin (1 μM), diluted with buffer composed of 20 mM BTP (pH 6.9), 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM DDM, and then quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence was measured with a Perkin Elmer L55 Luminescence Spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA) at 20°C. Emission spectra at 0 and 10 min after chromophore addition were recorded between 310 and 450 nm after excitation at 295 nm with excitation and emission slit bands set at 5 and 10 nm, respectively. For time-resolved measurements, fluorescence emission spectra were recorded at 330 nm under conditions outlined above.

Dissociation of Rho*e-Gt or chromophore-regenerated complexes by GTPγS

Rho*e-Gt, Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt, Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt, or Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt complexes were all dissociated by adding 200 μM GTPγS while they were still bound to an sConA affinity column.

Retinoid analyses

Rho*-Gt, Rho*e-Gt, opsin, or chromophore-regenerated complexes (∼100 μg protein) were denatured for 30 min at room temperature with 50% CH3OH in the presence of 40 mM NH2OH. The resulting retinal oximes were extracted with 300 μl of hexane, and their isomeric composition was determined by normal-phase HPLC with an Ultrasphere-Si, 5 μm, 4.5- × 250-mm column (Beckman, San Ramon, CA, USA). Retinoids, eluted isocratically with 10% ethyl acetate in hexane at a flow rate of 1.4 ml/min, were detected by their absorption at 360 nm (41, 42). Retinoid oximes were quantified based on areas under corresponding chromatography peaks. Amounts of retinals were calculated based on a standard curve presenting the correlation between areas and peaks of synthetic standards for each retinal oxime isomer.

NaBH4 reduction of the Schiff base in Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt or Rho*

sConA resin with bound Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt (3 ml) was transferred from the column to a 50-ml tube as a 50% slurry. The secondary amine was produced by reduction of the Schiff base bond in Rho with excess of NaBH4 by a procedure described previously (43). Briefly, 6 mg of solid NaBH4 was added to a tube containing resin with bound regenerated Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex and, following 30 min incubation on ice, the resin was loaded into the column again. NaBH4 was washed out with 5 column vol of the equilibrating buffer, and Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt containing the reduced Schiff base bond was eluted from the resin. Its UV-visible spectrum showed a peak at 330 nm, indicating formation of secondary amine, a product of Schiff base chemical reduction. This protein was concentrated to ∼3 mg/ml and used for mass spectrometry (MS) analyses.

Alternatively, the control sample of Rho* with trapped endogenous all-trans-retinal was prepared as follows: ROS membranes (200 μl with ∼1 mg/ml Rho) were illuminated for 10 min at room temperature, and the Schiff base bond between isomerized all-trans-retinal and opsin was reduced with NaBH4. NaBH4 (40 mg/ml) was added to the membranes in 5-μl aliquots 5 times at 5-min intervals. Excess NaBH4 was removed by overnight dialysis against fresh H2O. Membranes were solubilized with 10 mM DDM and used for MS analyses.

MS identification of a Schiff base linkage in the Rho*e-Gt complex regenerated with all-trans-retinal

Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt (or free Rho*; 20 μg) was digested overnight with pepsin (10 μg; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) at pH 2.5 and room temperature after the pH had been lowered from 6.9 to 2.5 with 0.1% formic acid in H2O. Following this overnight procedure, the pH of the sample was adjusted to 7.4 with 10 μl of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and peptic fragments were acetylated by adding acetic anhydride (99.5%; Sigma) at a rate of 2.5 μl/10 min for 50 min. The resulting sample was used for MS analysis with an LXQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source that operated in a positive mode with the capillary temperature set to 350°C. The mass spectrometer was coupled to a HP 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Peptide separation was achieved by a 2-pump controlled reverse phase elution setup with an aqueous phase composed of 0.1% formic acid in H2O (phase A) and an organic phase composed of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (phase B). The sample (100 μl) was loaded onto a Luna 20- × 2.00-mm C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) equilibrated with 98% phase A and 2% phase B for 30 min. Peptides were eluted with the following gradients: 0 to 4 min, 98% phase A and 2% phase B; 4 to 38 min, 2% phase A and 98% phase B. Tandem MS (MS2) and triple MS (MS3) spectra were collected by using collision-induced dissociation with the normalized collision energy set to 35 kV. Spectra were analyzed and interpreted with Xcalibur software (ver. 2.1.0.1139; Thermo Scientific).

Preparation of retinoid-modified peptide standard

The 6-aa acetyl-FAKTSA peptide standard (the same that was identified in both Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex and free R*) was custom ordered (EZBbiolab, Westfield, IN, USA) and conjugated with retinal as follows: 1 mg peptide was dissolved in acetonitrile-methanol at a 1:1 ratio, mixed with 1 mg of all-trans-retinal and 1% acetic acid, and incubated 48 h at room temperature to form the Schiff base linkage, following reduction with NaHB4. Solid NaHB4 (∼2 mg) was added to the sample, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min on ice. Then 500 μl H20 was added to react with excess NaHB4. Acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide (wherein K* is the retinoid modified lysine) was extracted with chloroform, dried in a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific), and dissolved in 1:1 acetonitrile-methanol, and used immediately for MS analysis or stored at −20°C.

RESULTS

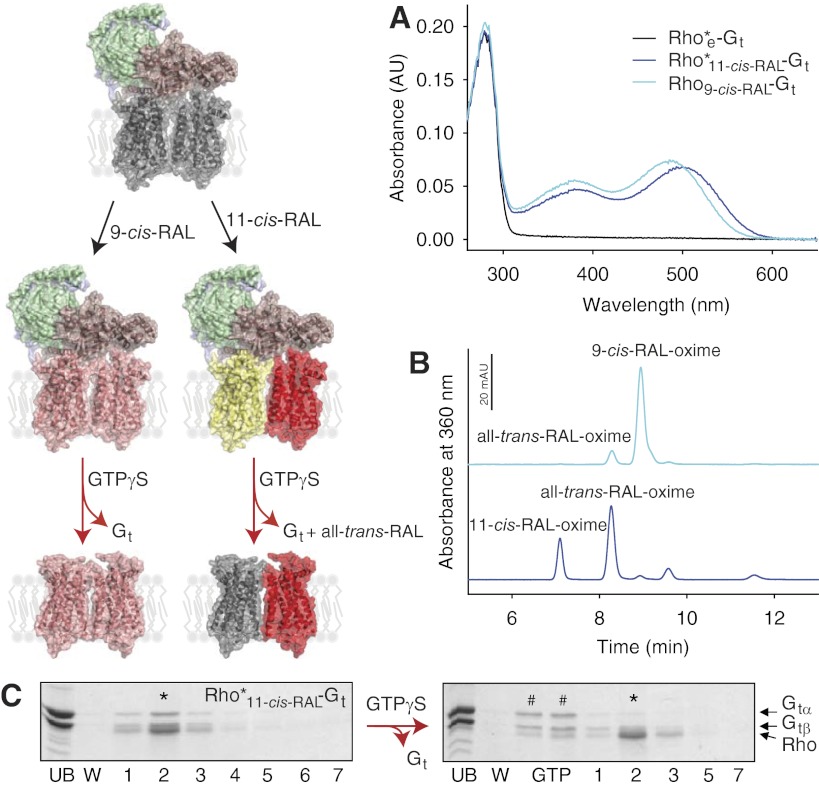

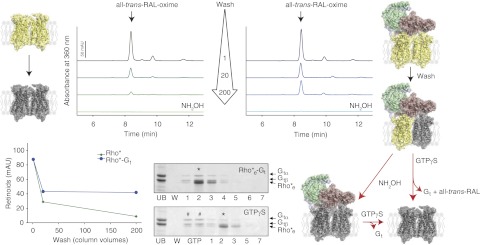

Gt prevents all-trans-retinal release from photoactivated Rho

Photoactivation of Rho results in sequential steps of 11-cis-retinylidene chromophore isomerization to all-trans-retinylidene, followed by Schiff base linkage hydrolysis and release of all-trans-retinal (44, 45). In its transient state, Rho* binds to the heterotrimeric G protein, transducin, promoting dissociation of GDP from Gtα and formation of the transitory Rho*-Gt complex. Although short-lived in nature, this Rho*-Gt complex can be trapped as a stable intermediate in the absence of nucleotides. Electron microscopy (EM) and single-particle reconstruction of this Rho*-Gt complex recently revealed its pentameric assembly with a Rho to Gt stoichiometry of 2:1 (21). This complex exhibits a UV-visible maximum absorption peak at 380 nm and contains only all-trans-retinal bound, indicating that Gt stabilizes the activated conformation of Rho and inhibits retinal release from the retinal-binding pocket. However, the chromophoric stoichiometry of this stabilized adduct has not been documented. To determine the effect of Gt on retinal release from the chromophore-binding pocket of photoactivated Rho, we prepared sConA resin that bound either the Rho* dimer or the Rho*-Gt complex. Extensive washing of resin bound-Rho* with buffer containing DDM resulted in nearly complete depletion of the chromophore (Fig. 1; retinoid analysis plots, left top and bottom panels, also modeled yellow-yellow Rho dimer transitioned to gray-gray Rho dimer, shown on the left). In contrast, chromophore release from the Rho*-Gt complex was only partial, with ∼50% of all-trans-retinal remaining trapped in the chromophore-binding pocket (Fig. 1; retinoid analysis plots, right top panel and bottom left panel, also modeled yellow-yellow Rho dimer coupled to Gt transitioned to yellow-gray Rho dimer coupled to Gt shown on the right), indicating a protective role of bound Gt. To achieve complete chromophore release from the Rho*-Gt complex, a wash with NH2OH was applied to promote Schiff base hydrolysis. The resulting chromophore-depleted Rho*e-Gt complex remained intact (Fig. 1; model of gray-gray Rho coupled to Gt) but sensitive to dissociation by GTPγS (Fig. 1; SDS-PAGE gels, bottom center, also model of gray-gray Rho coupled to Gt transitioned to gray-gray Rho dimer).

Figure 1.

Protection of the chromophore-protein linkage in the Rho*-Gt complex. Activated Rho (Rho*, yellow-yellow dimer on the left) and the Rho*-Gt complex (yellow-yellow dimer bound to Gt on the right), each bound to sConA resin, and washed with increasing volumes of equilibrating buffer and used for retinoid analyses. Similar levels of all-trans-retinal were detected in the initial Rho* and Rho*-Gt samples (top left panel, dark green line; and top right panel, dark blue line). Washing bound Rho*-Gt with 20 column vol of equilibrating buffer resulted in a decrease of all-trans-retinal to about half the original amount, which remained unchanged after additional washing with 200 column vol (depicted as a yellow-gray dimer bound to Gt). However, similar extensive washing of bound Rho* resulted in almost complete depletion of all-trans-retinal (left top and bottom panels, green lines; modeled as a gray dimer on the left). Complete chromophore release from Rho*-Gt was obtained only after a wash with NH2OH (right top panel, light blue line; modeled as a gray-gray dimer bound to Gt). Rho*e-Gt eluted from the sConA affinity resin and separated by SDS-PAGE contained both Rho*e and Gt (bottom central panel, top gel). Asterisk indicates the peak fraction, containing Rho*e-Gt. Functionality of this complex was evidenced by its dissociation with 200 μM GTPγS (bottom central panel, bottom gel). Pound signs indicate fractions containing dissociated Gt; asterisk indicates the peak fraction containing mostly Rho*e.

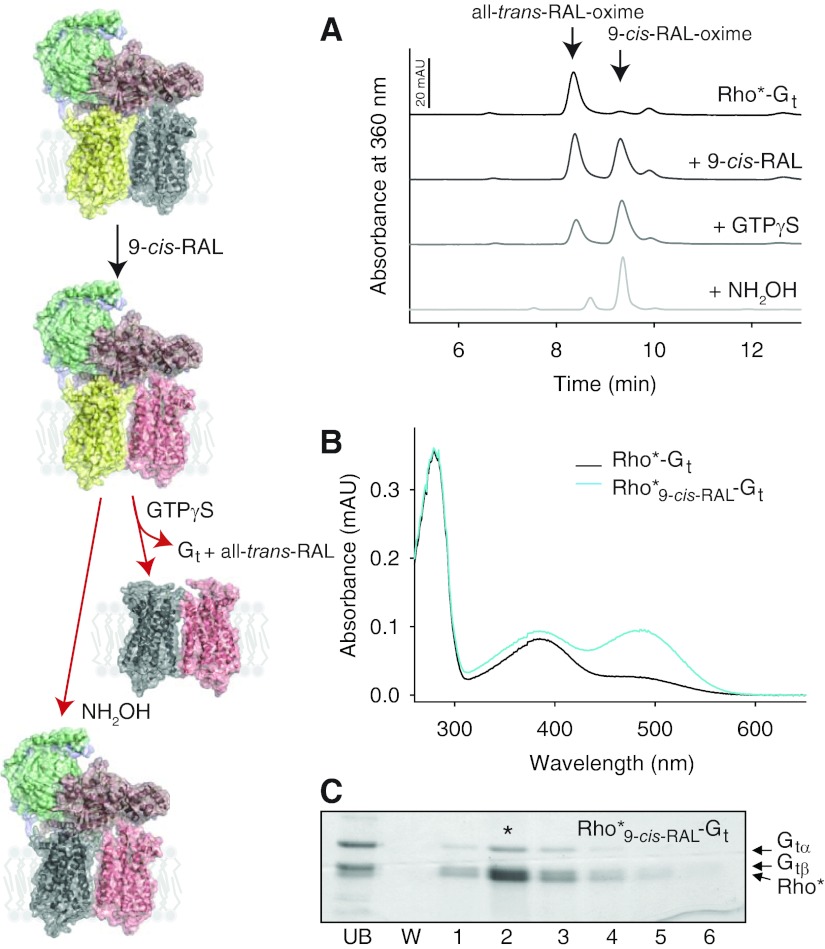

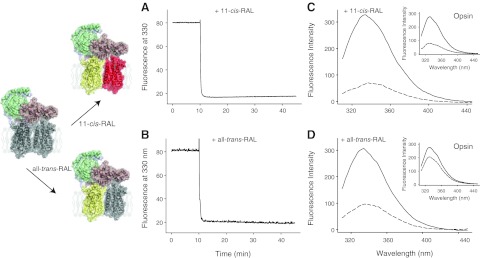

Binding of cis-chromophore to the Rho*e-Gt complex

To determine whether the chromophore-depleted Rho*e-Gt complex could be regenerated with 11-cis-retinal to form Rho or with 9-cis-retinal to form isoRho, the specific retinoid was added to Rho*e-Gt bound to the sConA resin and excess retinoid was washed out. Formation of Rho or isoRho still coupled to Gt was monitored immediately after their elution from the column by either UV-visible absorption spectroscopy or HPLC analyses of retinoids extracted from the regenerated complexes. Regeneration of Rho*e was documented by an increased maximum absorption at 485 or 500 nm after Rho*e-Gt (Fig. 2; model of gray-gray Rho dimer coupled to Gt) incubation with 9-cis-retinal or 11-cis-retinal, respectively (Fig. 2A). (The peak at ∼380 nm observed in both samples could result from a deprotonated form of the Schiff base). HPLC retinoid analyses of the complex regenerated with 9-cis-retinal (Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt) primarily identified 9-cis-retinal (95%) with only a small fraction of all-trans-retinal (5%), indicating that both Rho molecules of the dimer had been regenerated with 9-cis-retinal (Fig. 2B, light blue line; also model of pink-pink Rho dimer coupled to Gt). However, a ∼1:1 ratio of 11-cis-retinal (44%) and all-trans-retinal (56%) was identified in the Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt complex (Fig. 2B, dark blue line). Therefore, only one Rho of the dimer could be regenerated with 11-cis-retinal, whereas the second Rho monomer promoted the isomerization of the less stable 11-cis-retinal to all-trans-retinal, the conformation present in the active state of Rho (Fig. 2; model of yellow-red Rho dimer coupled to Gt). Both Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt (Fig. 2C) and Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt (not shown) remained functionally active after elution from their respective sConA columns, because both were sensitive to dissociation by GTPγS. After dissociation of the Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt complex and loss of protection ensured by bound Gt, all-trans-retinal was released from the chromophore binding pocket, resulting in the formation of the Rho*e-Rho dimer, where one Rho monomer is in an opsin-like conformation, and the second in a ground, 11-cis-retinal bound state (Fig. 2; model of gray-red Rho dimer).

Figure 2.

Regeneration of the Rho*e-Gt complex with either 11-cis-retinal or 9-cis-retinal. Rho*e-Gt was prepared by treatment of the Rho*-Gt complex with NH2OH (modeled as gray-gray dimer bound to Gt). While still bound to the column, chromophore-depleted Rho*e-Gt was regenerated with a 2-fold molar excess of either 11-cis-retinal (shown as a yellow-red dimer bound to Gt) or 9-cis-retinal (shown as pink-pink dimer bound to Gt). Excess retinoid was washed out, and regenerated complexes were eluted and analyzed by UV-visible absorbance measurements and retinoid oxime quantification. A) UV-visible absorption spectra of Rho*e-Gt, Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt and Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt are shown with black, dark blue, and light blue lines, respectively. B) Isocratic analyses of retinoid oximes extracted from Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt (dark blue line) and Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt (light blue line) complexes. Most of the 9-cis-retinal (95%) and a small fraction of all-trans-retinal (5%) were identified in the Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt complex, whereas a mixture of 11-cis-retinal (44%) and all-trans-retinal (56%) were found in the Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt complex. C) SDS-PAGE gel of Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt purified by sConA affinity chromatography (left panel). Asterisk inciates the eluted peak fraction containing both Rho and Gt. Functionality of this complex was evidenced by its dissociation with 200 μM GTPγS. Pound signs indicate fractions containing dissociated Gt. Asterisk indicates peak fraction eluted from the column containing mostly Rho.

Quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence by incorporation of 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinal into Rho*e-Gt or opsin

Here interactions between retinal and protein were monitored by recording changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of tryptophan. Addition of a 2-fold molar excess of either 11-cis-retinal or all-trans-retinal to the sample rapidly generated retinoid uptake signals for the chromophore-depleted samples of opsin (Fig. 3C, D; insets) and Rho*e-Gt complex (Fig. 3), manifested as quenched intrinsic protein fluorescence. These observations indicated formation of a complex between Rho*e in the Rho*e-Gt complex and either 11-cis-retinal or all-trans-retinal (Fig. 3; models of yellow-red Rho dimer coupled to Gt and yellow-gray Rho dimer coupled to Gt, respectively). Remarkably, while the fluorescence of free opsin was quenched by 11-cis-retinal, only a minor change in opsin intrinsic fluorescence was observed after addition of all-trans-retinal (Fig. 3C, D; insets). These results indicate a structural difference between retinal-free Rho*e in the Rho*e-Gt complex and opsin.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence changes in Rho*e-Gt complex evoked by addition of either 11-cis-retinal or all-trans-retinal. Quenching of the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence was measured on addition of a 2-fold molar excess of either 11-cis-retinal or all-trans-retinal to the chromophore-depleted Rho*e-Gt complex (shown as a gray-gray dimer bound to Gt; complex regenerated with 11-cis-retinal is modeled as yellow-red dimer bound to Gt, and the complex regenerated with all-trans-retinal is pictured as yellow-gray dimer bound to Gt). A, B) Time-dependent changes in Rho*e-Gt fluorescence emission were recorded at 330 nm with λex = 295 nm. After 10 min of recording, either 11-cis-retinal (A) or all-trans-retinal (B) was added, and the resulting rapid uptake signal was recorded. C, D) Fluorescence quenching of Rho*e-Gt was observed after uptake of either 11-cis-retinal (C) or all-trans-retinal (D), whereas marked fluorescence quenching of opsin itself was observed only after uptake of 11-cis-retinal (compare C, D, insets).

Asymmetry of Rho monomers in the Rho*-Gt complex

As described above, Gt bound to photoactivated Rho inhibited release of all-trans-retinal, trapping ∼50% of this isomerized endogenous chromophore in its binding pocket. This uneven protection of Rho monomers comprising the dimer demonstrates asymmetric properties of Rho molecules in the Rho*-Gt heteropentamer (Fig. 4; model of yellow-gray Rho dimer coupled to Gt). To investigate this phenomenon further, we incubated the Rho*-Gt complex with an excess of 9-cis-retinal and monitored product regeneration by UV-visible absorbance spectroscopy and retinoid analyses. The Rho*-Gt complex exhibited a UV-visible absorption spectrum with a major peak at ∼380 nm, whereas peaks at 380 and 485 nm were detected in the sample regenerated with 9-cis-retinal (Fig. 4B). Though only all-trans-retinal was detected in the Rho*-Gt complex (Fig. 4A; black spectrum and model of yellow-gray Rho dimer coupled to Gt), a mixture of all-trans-retinal and 9-cis-retinal with a 1:1 stoichiometry was detected in the Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt complex (Fig. 4A; very dark gray spectrum and model of yellow-pink Rho dimer coupled to Gt), indicating that bound Gt prevents release of all-trans-retinal from only one Rho molecule, while the second one eventually loses its chromophore and can be loaded with 9-cis-retinal. This result demonstrates functional and structural asymmetry of Rho dimer triggered by Gt binding. Regeneration of the Rho*-Gt with 9-cis-retinal did not affect the integrity of the complex (Fig. 4C). However, exposure of the regenerated Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt complex to 200 μM GTPγS promoted release of the endogenous all-trans-retinal originally trapped by Gt in the chromophore-binding pocket (Fig. 4A; dark gray spectrum and model of gray-pink Rho dimer). A significant reduction of all-trans-retinal but not 9-cis-retinal in the intact Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt complex was also achieved by treatment with NH2OH (Fig. 4A; light gray spectrum and model of gray-pink Rho dimer coupled to Gt).

Figure 4.

Asymmetry of Rho monomers in the Rho*-Gt complex. The Rho*-Gt complex prepared on an sConA affinity resin (modeled as a yellow-gray dimer bound to Gt) was regenerated with 9-cis-retinal (shown as a yellow-pink dimer bound to Gt), followed by either dissociation with GTPγS (depicted as a gray-pink dimer) or treatment with NH2OH (modeled as a gray-pink dimer bound to Gt). UV-visible absorbance spectra and retinoid composition of those complexes then were analyzed. A) Isocratic analyses of retinoid oximes extracted from Rho*-Gt (black line), regenerated with 9-cis-retinal, Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt (very dark gray line), Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt treated with either GTPγS (dark gray line) or with NH2OH (light gray line) are shown. Although only all-trans-retinal was detected in the Rho*-Gt complex, a mixture of all-trans-retinal and 9-cis-retinal with a 1:1 stoichiometry was found in the Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt complex. Treatment of Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt with GTPγS resulted in significant reduction in all-trans-retinal, and an even further reduction was obtained after a wash with NH2OH. B) UV-visible absorption spectra of Rho*-Gt and regenerated Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt are shown by black and light blue lines, respectively. C) SDS-PAGE gel of Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt purified by sConA affinity chromatography. Asterisk indicates the peak fraction containing both Rho* and Gt.

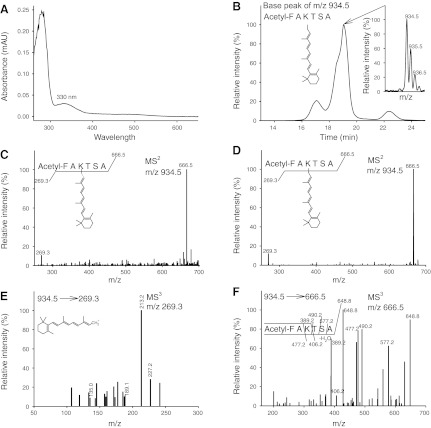

All-trans-retinal forms a Schiff base linkage when added to the Rho*-Gt complex

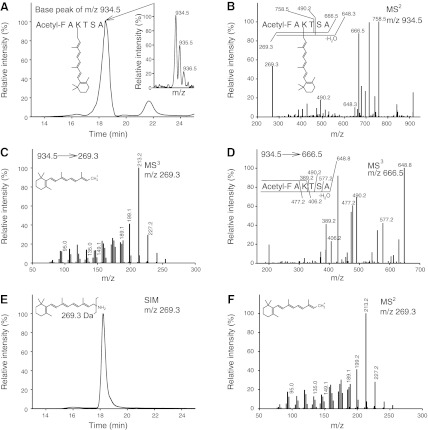

In dark-state Rho, 11-cis-retinal, and, in the Rho-activated state, all-trans-retinal, are covalently attached to Lys296 in the chromophore-binding pocket. However, other than this main retinal-binding site, secondary binding sites exist on the surface of opsin where retinal can bind noncovalently (46). As previously reported (47), all-trans-retinal added to detergent-solubilized opsin does not form a Schiff base linkage with Lys296 but, rather, attaches noncovalently. In the present study, we investigated whether a Schiff base bond is formed between added all-trans-retinal and Lys296 of chromophore-depleted Rho*e in the Rho*e-Gt complex. First, the Schiff base bond in the regenerated Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex was stabilized by reduction with NaBH4, resulting in creation of a stable secondary amine from n-retinylidene Schiff base exhibiting a UV absorption peak at 330 nm (Fig. 5A). This sample was acidified and digested with pepsin, and then the products were acetylated and analyzed by MS. This procedure resulted in the identification of an acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide containing Lys296 with the attached all-trans retinoid (m/z of 934.5 [MH]+; Fig. 5B). The MS2 of this singly charged ion led to the identification of 2 major ions, one with m/z 269.3, corresponding to the anhydroretinol moiety, and the other with m/z 666.5, corresponding to the peptide alone (Fig. 5C). The same result was obtained with a Rho* sample prepared by illumination of ROS membranes, which, following NaBH4-Schiff base reduction, carried endogenous all-trans-retinal (Fig. 5D). Fragmentation of the m/z 269.3 product revealed its identity as an anhydroretinol carbocation (Fig. 5E), whereas fragmentation of the second m/z 666.5 product produced a MS3 spectrum that corresponded to the retinoid-free acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide (Fig. 5F). To further test this interpretation, we generated a synthetic standard acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide. This synthetic peptide exhibited a MS identical to that of the proposed acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide (Fig. 6A) as identified peptide. The MS2 of this singly charged ion also yielded 2 major ions, one with m/z 269.3, corresponding to the retinoid, and the other with m/z 666.5, corresponding to the peptide alone (Fig. 6B). Fragmentation of the m/z 269.3 ion was identical to the same ion in both the acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide standard (Fig. 6C) and the retinylamine retinoid standard (Fig. 6E, F, respectively). Fragmentation of m/z 666.5 was identical to the same ion present in the acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide standard (Figs. 5F and 6D, respectively). These results clearly demonstrate that Gt bound to the chromophore-depleted Rho*e dimer stabilizes the active conformation of Rho, allowing access of exogenous all-trans-retinal to the retinal-binding pocket and reformation of a Schiff base linkage with Lys296.

Figure 5.

MS identification of the peptide forming a Schiff base linkage with retinal in the Rho*-Gt complex regenerated with all-trans-retinal. Analysis of peptic, acetylated fragments of the Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex (or free Rho*) with a NaHB4-reduced Schiff base bond identified a retinal-bound acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide containing Lys296 (where K* is lysine modified with retinoid). A) UV-visible absorbance spectrum of the Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex with a NaHB4-reduced Schiff base linkage shows an absorption maximum peak at 330 nm. B) Base peak of m/z 934.5 was detected after loading acetylated peptic fragments resulting from digestion of a Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt sample. This m/z 934.5 single-charged species was eluted from a Luna 20- × 2.00-mm C18 column (Phenomenex) in 18 to 19 min. Inset: isotopic distribution in the single-charged peptic peptide ion. C, D) MS2 of the m/z 934.5 singly charged ion identified as acetyl-FAK*TSA in Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt and free Rho* in ROS membranes, respectively. Major ions observed at m/z 269.3 (for retinoid) and at m/z 666.5 (for acetyl-FAKTSA peptide) were identical with those identified in the acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide standard (Fig. 6B) and retinylamine retinoid standard (Fig. 6E). E) Fragmentation of the m/z 269.3 ion derived from the m/z 934.5 parent ion obtained from a Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt sample indicates a retinoid ion (see structural formula). F) Fragmentation of m/z 666.5 ion derived from the m/z 934.5 parent ion obtained from the Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt complex indicates an acetyl-FAKTSA peptide.

Figure 6.

MS characterization of the acetyl-FAK*TSA peptide and retinylamine retinoid standards used to analyze MS data in Fig. 5. A) Base peak of m/z 934.5 representing the [MH]+ ion of the acetylated-retinoid modified peptide standard with the acetyl-FAK*TSA sequence, prepared in order to confirm peptide identification from Rho*all-trans-RAL-Gt and Rho* samples. Inset: isotopic distribution of the m/z 934.5 peak with an elution time of 18 to 19 min. B) MS2 spectra of m/z 934.5. Representative ions resulting from collision-induced differentiation are attributed to the retinoid ion with m/z 269.3 and the acetylated peptide acetyl-FAKTSA at m/z 666.5. Several other ions shown were identified as collision induced dissociation (CID) products originating from the acetyl-FAKTSA peptide fragment. C) Fragmentation of m/z 269.3 originating from the MS2 of m/z 934.5 described in B. D) Fragmentation of m/z 666.5 originating from the MS2 of m/z 934.5 described in B. E) Selected ion monitoring (SIM) for m/z 269.3 of the retinoid standard (retinylamine) eluted from Luna 20- × 2.00-mm C18 column (Phenomenex). F) MS2 spectra of m/z 269.3 from the SIM experiment with the retinoid standard shown in E.

DISCUSSION

Convincing evidence indicates that GPCR dimerization and activation are intricately associated. The functional consequences of GPCR dimerization have been revealed by studies showing intercommunication between 2 protomers in these dimers (19, 48–50). Whereas such cooperation can be relatively easily proven for heterodimers, it is more challenging for homodimeric GPCRs.

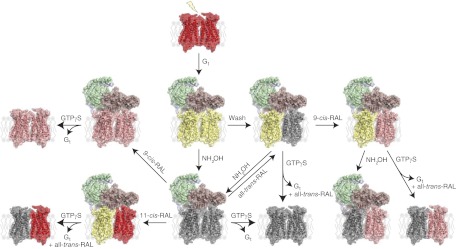

Here we studied the properties of dimeric Rho, a prototypic member of family A GPCRs. In native membranes, Rho exists as densely packed dimers organized in rows (13). Although the functional relevance of Rho's dimeric nature is highly debated, we have shown by EM and single-particle reconstruction that, in response to light, a Rho dimer is required for binding to a single G protein (21). Until now it has been unclear whether both Rho monomers within the activated dimer are structurally and functionally equivalent. Therefore, by unequivocally tracing each Rho monomer with an isomeric variant of the chromophore, we probed the symmetry of a Rho dimer within the stable Rho*-Gt complex. This strategy indicated that each monomer in the Rho dimer coupled to Gt exhibited different conformational properties (Fig. 7). Only one Rho, most likely the one hosting the C terminus of Gtα, is stabilized in its active Meta II state with its chromophore, all-trans-retinal, trapped in the retinal-binding pocket. But at the same time, all-trans-retinal is released from the second Rho, which eventually decays to opsin and free retinal (Fig. 7; yellow-gray Rho dimer bound to Gt). Interestingly, this chromophore-free Rho*e molecule can be regenerated with 9-cis-retinal without affecting the integrity and activity of the whole Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt complex. As evidenced by HPLC retinoid analysis, such a regenerated complex retained both all-trans-retinal and 9-cis-retinal in a 1:1 stoichiometry, demonstrating unambiguously that 2 Rho molecules are bound to 1 Gt, which influences their functional and structural distinction (Fig. 7; yellow-pink Rho dimer bound to Gt). Stabilized by Gt, a Rho monomer can lose its chromophore only after complex dissociation with GTPγS, or its hydrolysis can be effected by treatment of the intact complex with the strong nucleophile NH2OH, resulting in formation of the chromophore-depleted Rho*e-Gt complex (Fig. 7; gray-gray Rho dimer bound to Gt). Such a complex is still active and can be regenerated with different isomeric variants of chromophore. Interestingly, HPLC analysis of retinoids extracted from the Rho*e-Gt complex after incubation with 11-cis-retinal resulted in a mixture of 11-cis-retinal and all-trans-retinal in ∼1:1 ratio, indicating that only one Rho molecule in the dimer was regenerated with 11-cis-retinal, whereas the other was bound to all-trans-retinal (Fig. 7; yellow-red Rho dimer bound to Gt). The only possible explanation of this unexpected discovery is that one of the Rho monomers is stabilized by Gt in its active Meta II-like state even after chromophore depletion. Consequently, the rigid constraints of this protein force the isomerization of 11-cis-retinal to its all-trans conformer, because only the latter can fit the chromophore-binding pocket of Meta II-like Rho. This protein-forced retinal isomerization, however, was not observed for the more stable 9-cis-retinal, which regenerated both Rho molecules of the Rho*e-Gt complex (Fig. 7; pink-pink Rho dimer bound to Gt).

Figure 7.

Asymmetry of Rho* dimer within Rho*-Gt complex. The Rho*-Gt complex is formed by binding of a fully activated Rho dimer to Gt. After light illumination, 11-cis-retinal of ground state Rho (shown as red-red dimer) isomerizes to all-trans-retinal (yellow-yellow dimer), allowing binding of the heterologous Gt trimer (Gtα is depicted in salmon, Gtβ in green, and Gtγ in light blue). This binding prevents chromophore release from one Rho in the dimer, introducing dimer asymmetry in the Rho*-Gt complex (shown after a wash as a yellow-gray dimer bound to Gt). Release of chromophore from the Gt-protected Rho molecule can be promoted by NH2OH, resulting in formation of the chromophore-free Rho*e-Gt complex (modeled as a gray-gray dimer bound to Gt). This complex then can be either dissociated with GTPγS (shown as gray-gray dimer) or regenerated. 9-Cis-retinal regenerates both Rho monomers in the dimer (shown as a pink-pink dimer bound to Gt). However, 11-cis-retinal regenerates only one Rho monomer, while the second Rho promotes isomerization of 11-cis-retinal to its all-trans conformer, resulting in formation of an asymmetric dimer (indicated by a yellow-red dimer bound to Gt). Both complexes regenerated with either 9-cis- or 11-cis-retinal can be dissociated with GTPγS (shown as pink-pink or gray-red models, respectively). But regeneration with all-trans-retinal results in its uptake by only one Rho monomer (shown as a yellow-gray dimer bound to Gt), and the second Rho can be regenerated with 9-cis-retinal (shown as yellow-pink dimer bound to Gt). All-trans-retinal can be released from such complexes by either NH2OH (modeled as a gray-pink dimer bound to Gt) or GTPγS (imaged as a gray-pink dimer).

Another key finding here is that chromophore-depleted Rho*e bound to Gt could uptake exogenous all-trans-retinal into its empty retinal-binding pocket and reform a Schiff base linkage between this retinal and its reactive lysine K296. But as shown previously (47), all-trans-retinal does not reenter the chromophore-binding pocket of free opsin, presumably because the conformational equilibrium is shifted toward the inactive conformation. Moreover, all-trans-retinal can enter only one of the two retinal-free Rho*e molecules in the Rho*e-Gt complex, implying that, unlike the Rho monomer in the opsin conformation, only the Rho* monomer stabilized by Gt in the Meta II-like state can provide access to all-trans-retinal (results not shown; Fig. 7; yellow-gray Rho dimer bound to Gt).

Rho's agonist and antagonist ligands are covalently linked to the opsin moiety, thus allowing an excess of free ligand to be washed out (51). Indeed, the chromophore-opsin interaction gives rise to specific absorption spectra characteristic of both the chromophore and the activated state of the receptor. Thus the switch from agonistic (cis-retinoid) to antagonistic (all-trans-isomer) retinoid can be readily monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy, whereas the presence of chromophore in the binding site can be followed by fluorescence spectroscopy that reveals the quenching of fluorescence emanating from the specific Trp residues involved in retinoid binding (47, 52). Moreover, because of the high absorption coefficient of the chromophore, its isomeric nature can be determined by chemical analysis using HPLC and MS even on small sample sizes. Finally, this methodology can be applied to unmodified Rho/opsin-transducin complexes isolated from native sources, e.g., bovine eyes. All these advantages over other family A GPCR systems enabled us to study the nature of each Rho monomer within Gt-bound pentameric complex and the dimeric complex without Gt. The results also provide direct evidence for a different conformational arrangement of Rho monomers within the dimer after assembly with Gt.

When high-resolution structures of vertebrate (4) and invertebrate (53) Rho molecules and structures of GPCR-interacting proteins, such as G proteins (54), arrestins (55), and GRKs (56, 57) became available, it transpired that GPCRs, as well as their partner proteins, share striking structural similarity (average root-mean-square deviation <2 Å). Along with structural information, physiological findings also support the functional hetero-oligomerization of GPCRs. For example, the mGluR family of receptors' activation mechanism involves a change in quaternary structure of two obligatory monomers coupled to each other by a disulfide bridge (58, 59); the GABAB receptor functional unit is an obligate heterodimer composed of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits (60–62); and obligate heterooligomers of taste receptors exist for sweet and umami responses (63, 64). These were the first examples that unequivocally established dimerization and its functional importance. Mindful that the function of all GPCRs depends on intermolecular interactions with G proteins, GRKs, and arrestins along with additional evidence that GPCRs have a propensity to form homo- and heterooligomers, it seems logical that dimerization is not a unique characteristic of only a few receptors but rather a property of a whole subclass of GPCRs. Modeling studies also indicated that the Rho dimer offers a geometrically compatible platform for the binding of partner proteins, such as Gt or arrestin, because each of the latter exhibit a “footprint” larger than that of a Rho monomer (32, 65, 66). The Rho-Gt-induced fit model implies that activation could involve the relaxation of a somewhat more rigid structure constituting the inactive state of the receptor, following a further increase of its rigidity on Gt binding (67). This process occurs differentially within GPCR monomers, as shown in this work; thus, each Rho* provides a different platform for an interaction with Gt. This interpretation agrees with the recent structural model for the photoactivated Rho*-Gt complex featured in a low-resolution 3-dimensional map obtained by EM-single particle reconstruction (21, 31). Its molecular envelope accommodated two Rho molecules together with one Gt heterotrimer, consistent with a heteropentameric structure of this complex as shown by the present biochemical approach. This evidence sharply contrasts with that derived from crystal structures of an active state complex comprised of agonist-occupied monomeric β2-adrenergic receptor-T4L-lyzosome fusion, nucleotide-free Gs heterotrimer, and a nanobody, which provides the most unexpected structure, with a major displacement of the entire α-helical domain of Gα relative to the Ras-like GTPase domain (68). The latter is a rigid body type of displacement, where one subdomain dives into the lipid bilayer with an averaged angle between subdomains of ∼130°, whereas the distance between the α-helical subdomains of Gt and Gs was found to be ∼40 Å (68). Thus, for the two domains to superpose, a full ∼180° rotation of the Gsα-α-helical subdomain alone is required. Therefore, the relevance of this monomeric GPCR structural model to general GPCR physiology, in our view, remains an open question.

Together with our EM structural data, the results presented here unambiguously demonstrate that after light activation, a single Gt heterotrimer binds to a Rho dimer (21, 31). In the Rho*-Gt complex thus formed, each Rho monomer is structurally different, and only one is stabilized in the active Meta II state by bound Gt, while the other evolves into an opsin-like conformation. Although the physiological role of this dimer asymmetry has yet to be clarified, regulation of the clearance of excess all-trans-retinal produced under bright light conditions, where Rho*-Rho* dimer would be at a significantly higher level as compared to Rho-Rho* as a mechanism protecting rod cells, is an intriguing possibility. The concept of Rho dimer asymmetry agrees also with possible cross-communication between GPCR protomers within a dimer. Rho and Rho* share the same recognition mode for Gt (69). Therefore it is possible that precoupled Rho-Gt complexes exist in the dark. Taking into account that only one Rho molecule within the dimer can provide binding determinants for Gtα, a possibility of asymmetric Rho activation arises. In such situations, photoexcitation of chromophore and its isomerization in the Rho monomer that does not physically interact with Gtα, would induce conformational changes in the precoupled Rho monomer, leading to conformational evolution toward the Meta II state, needed to form the active Rho*-Gt complex (70, 71). Therefore, this tandem mechanism could be critical to avoid loss of energy, enhance the efficiency of receptor activation, and result in desensitization. Because the in vitro assay of Gt activation is highly aberrant and can result in markedly slower activation rates than those observed in vivo, these concepts now can be tested experimentally using electrophysiological methods.

In any case, our present findings open a new avenue toward understanding the functional role of Rho dimerization in complex with transducin as well as GPCR dimerization in complex with G proteins in general.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Leslie T. Webster, Jr. and members of the K.P. laboratory for helpful comments on this manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants EY008061 and EY019478. K.P. is John Hord Professor of Pharmacology.

Footnotes

- DDM

- n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- EM

- electron microscopy

- GDP

- guanosine diphosphate

- GPCR

- G-protein-coupled receptor

- Gt

- G-protein transducin

- GTP

- guanosine triphosphate

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- HPLC

- high-performance liquid chromatography

- isoRho

- isorhodopsin

- Meta II

- metarhodopsin II

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS2

- tandem mass spectrometry

- MS3

- triple mass spectrometry

- NMWL

- normal molecular weight limit

- Rho

- rhodopsin

- Rho*

- photoactivated rhodopsin

- Rho*e-Gt

- chromophore-depleted Rho*-Gt

- Rho9-cis-RAL-Gt

- Rho*e-Gt regenerated with 9-cis-retinal

- Rho*9-cis-RAL-Gt

- Rho*-Gt regenerated with 9-cis-retinal

- Rho*11-cis-RAL-Gt

- Rho*e-Gt regenerated with 11-cis-retinal

- ROS

- rod outer segment

- sConA

- succinylated concanavalin A

REFERENCES

- 1. Argos P., Rao J. K., Hargrave P. A. (1982) Structural prediction of membrane-bound proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 128, 565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baldwin J. M., Schertler G. F., Unger V. M. (1997) An alpha-carbon template for the transmembrane helices in the rhodopsin family of G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 272, 144–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Unger V. M., Hargrave P. A., Baldwin J. M., Schertler G. F. (1997) Arrangement of rhodopsin transmembrane alpha-helices. Nature 389, 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Hori T., Behnke C. A., Motoshima H., Fox B. A., Le Trong I., Teller D. C., Okada T., Stenkamp R. E., Yamamoto M., Miyano M. (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choe H. W., Kim Y. J., Park J. H., Morizumi T., Pai E. F., Krauss N., Hofmann K. P., Scheerer P., Ernst O. P. (2011) Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature 471, 651–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park J. H., Scheerer P., Hofmann K. P., Choe H. W., Ernst O. P. (2008) Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature 454, 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salom D., Lodowski D. T., Stenkamp R. E., Le Trong I., Golczak M., Jastrzebska B., Harris T., Ballesteros J. A., Palczewski K. (2006) Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 16123–16128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakamichi H., Okada T. (2006) Local peptide movement in the photoreaction intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 12729–12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deupi X., Edwards P., Singhal A., Nickle B., Oprian D., Schertler G., Standfuss J. (2012) Stabilized G protein binding site in the structure of constitutively active metarhodopsin-II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 119–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lebon G., Warne T., Tate C. G. (2012) Agonist-bound structures of G protein-coupled receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 482–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katritch V., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. (2012) Diversity and modularity of G protein-coupled receptor structures. Trend Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 17–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palczewski K. (2010) Oligomeric forms of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Trend Biochem. Sci. 35, 595–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fotiadis D., Liang Y., Filipek S., Saperstein D. A., Engel A., Palczewski K. (2003) Atomic-force microscopy: rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature 421, 127–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ianoul A., Grant D. D., Rouleau Y., Bani-Yaghoub M., Johnston L. J., Pezacki J. P. (2005) Imaging nanometer domains of beta-adrenergic receptor complexes on the surface of cardiac myocytes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 196–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kniazeff J., Prezeau L., Rondard P., Pin J. P., Goudet C. (2011) Dimers and beyond: the functional puzzles of class C GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 130, 9–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bayburt T. H., Leitz A. J., Xie G., Oprian D. D., Sligar S. G. (2007) Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14875–14881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whorton M. R., Jastrzebska B., Park P. S., Fotiadis D., Engel A., Palczewski K., Sunahara R. K. (2008) Efficient coupling of transducin to monomeric rhodopsin in a phospholipid bilayer. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4387–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lambert N. A. (2010) GPCR dimers fall apart. Sci. Signal. 3, pe12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rivero-Muller A., Chou Y. Y., Ji I., Lajic S., Hanyaloglu A. C., Jonas K., Rahman N., Ji T. H., Huhtaniemi I. (2010) Rescue of defective G protein-coupled receptor function in vivo by intermolecular cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 2319–2324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang N., Kolesnikov A.V., Jastrzebska B., Mustafi D., Sawada O., Maeda T., Genoud C., Engel A., Kefalov V.J., Palczewski K. (2013) Knock-in E150K opsin mutant mice, a model for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, exhibit structural disorganization of photoreceptor internal membranes. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 121–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jastrzebska B., Ringler P., Lodowski D. T., Moiseenkova-Bell V., Golczak M., Muller S. A., Palczewski K., Engel A. (2011) Rhodopsin-transducin heteropentamer: three-dimensional structure and biochemical characterization. J. Struct. Biol. 176, 387–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krebs A., Villa C., Edwards P. C., Schertler G. F. (1998) Characterisation of an improved two-dimensional p22121 crystal from bovine rhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 282, 991–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park P. S., Lodowski D. T., Palczewski K. (2008) Activation of G protein-coupled receptors: beyond two-state models and tertiary conformational changes. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48, 107–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jastrzebska B., Golczak M., Fotiadis D., Engel A., Palczewski K. (2009) Isolation and functional characterization of a stable complex between photoactivated rhodopsin and the G protein, transducin. FASEB J. 23, 371–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bulenger S., Marullo S., Bouvier M. (2005) Emerging role of homo- and heterodimerization in G-protein-coupled receptor biosynthesis and maturation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fotiadis D., Jastrzebska B., Philippsen A., Muller D. J., Palczewski K., Engel A. (2006) Structure of the rhodopsin dimer: a working model for G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 252–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palczewski K. (2006) G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 743–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okada T., Ernst O. P., Palczewski K., Hofmann K. P. (2001) Activation of rhodopsin: new insights from structural and biochemical studies. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spalink J. D., Reynolds A. H., Rentzepis P. M., Sperling W., Applebury M. L. (1983) Bathorhodopsin intermediates from 11-cis-rhodopsin and 9-cis-rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80, 1887–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bornancin F., Pfister C., Chabre M. (1989) The transitory complex between photoexcited rhodopsin and transducin. Reciprocal interaction between the retinal site in rhodopsin and the nucleotide site in transducin. Eur. J. Biochem. 184, 687–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vahedi-Faridi A., Jastrzebska B., Palczewski K., Engel A. (2012) 3D imaging and quantitative analysis of small solubilized membrane proteins and their complexes by transmission electron microscopy. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Electron Microsc. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfs091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang Y., Fotiadis D., Filipek S., Saperstein D. A., Palczewski K., Engel A. (2003) Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21655–21662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papermaster D. S. (1982) Preparation of retinal rod outer segments. Methods Enzymol. 81, 48–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okada T., Tsujimoto R., Muraoka M., Funamoto C. (2005) Methods and results in X-ray crystallography of bovine rhodopsin. In G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Structure, Function, and Ligand Screening (Haga T., ed) pp. 245–261, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wald G., Brown P. K. (1953) The molecular excitation of rhodopsin. J. Gen. Physiol. 37, 189–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goc A., Angel T. E., Jastrzebska B., Wang B., Wintrode P. L., Palczewski K. (2008) Different properties of the native and reconstituted heterotrimeric G protein transducin. Biochemistry 47, 12409–12419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Surya A., Foster K. W., Knox B. E. (1995) Transducin activation by the bovine opsin apoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5024–5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kito Y., Suzuki T., Azuma M., Sekoguti Y. (1968) Absorption spectrum of rhodopsin denatured with acid. Nature 218, 955–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kropf A., Hubbard R. (1970) The photoisomerization of retinal. Photochem. Photobiol. 12, 249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Hooser J. P., Garwin G. G., Saari J. C. (2000) Analysis of visual cycle in normal and transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol. 316, 565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garwin G. G., Saari J. C. (2000) High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of visual cycle retinoids. Methods Enzymol. 316, 313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bownds D., Wald G. (1965) Reaction of the rhodopsin chromophore with sodium borohydride. Nature 205, 254–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jastrzebska B., Palczewski K., Golczak M. (2011) Role of bulk water in hydrolysis of the rhodopsin chromophore. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 18930–18937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wald G., Hubbard R. (1957) Visual pigment of a decapod crustacean: the lobster. Nature 180, 278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heck M., Schadel S. A., Maretzki D., Hofmann K. P. (2003) Secondary binding sites of retinoids in opsin: characterization and role in regeneration. Vision Res. 43, 3003–3010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schadel S. A., Heck M., Maretzki D., Filipek S., Teller D. C., Palczewski K., Hofmann K. P. (2003) Ligand channeling within a G-protein-coupled receptor. The entry and exit of retinals in native opsin. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24896–24903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Han Y., Moreira I. S., Urizar E., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2009) Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Damian M., Martin A., Mesnier D., Pin J. P., Baneres J. L. (2006) Asymmetric conformational changes in a GPCR dimer controlled by G-proteins. EMBO J. 25, 5693–5702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maurice P., Kamal M., Jockers R. (2011) Asymmetry of GPCR oligomers supports their functional relevance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32, 514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bownds D. (1967) Site of attachment of retinal in rhodopsin. Nature 216, 1178–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matthews R. G., Hubbard R., Brown P. K., Wald G. (1963) Tautomeric forms of metarhodopsin. J. Gen. Physiol. 47, 215–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Murakami M., Kouyama T. (2008) Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin. Nature 453, 363–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lambright D. G., Sondek J., Bohm A., Skiba N. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B. (1996) The 2.0 A crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 379, 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Granzin J., Wilden U., Choe H. W., Labahn J., Krafft B., Buldt G. (1998) X-ray crystal structure of arrestin from bovine rod outer segments. Nature 391, 918–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lodowski D. T., Tesmer V. M., Benovic J. L., Tesmer J. J. (2006) The structure of G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK)-6 defines a second lineage of GRKs. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16785–16793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Singh P., Wang B., Maeda T., Palczewski K., Tesmer J. J. (2008) Structures of rhodopsin kinase in different ligand states reveal key elements involved in G protein-coupled receptor kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14053–14062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tateyama M., Abe H., Nakata H., Saito O., Kubo Y. (2004) Ligand-induced rearrangement of the dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor 1alpha. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 637–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kunishima N., Shimada Y., Tsuji Y., Sato T., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Nakanishi S., Jingami H., Morikawa K. (2000) Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature 407, 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaupmann K., Malitschek B., Schuler V., Heid J., Froestl W., Beck P., Mosbacher J., Bischoff S., Kulik A., Shigemoto R., Karschin A., Bettler B. (1998) GABA(B)-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature 396, 683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jones K. A., Borowsky B., Tamm J. A., Craig D. A., Durkin M. M., Dai M., Yao W. J., Johnson M., Gunwaldsen C., Huang L. Y., Tang C., Shen Q., Salon J. A., Morse K., Laz T., Smith K. E., Nagarathnam D., Noble S. A., Branchek T. A., Gerald C. (1998) GABA(B) receptors function as a heteromeric assembly of the subunits GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2. Nature 396, 674–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. White J. H., Wise A., Main M. J., Green A., Fraser N. J., Disney G. H., Barnes A. A., Emson P., Foord S. M., Marshall F. H. (1998) Heterodimerization is required for the formation of a functional GABA(B) receptor. Nature 396, 679–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chandrashekar J., Hoon M. A., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2006) The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature 444, 288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang A. L., Chen X., Hoon M. A., Chandrashekar J., Guo W., Trankner D., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2006) The cells and logic for mammalian sour taste detection. Nature 442, 934–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Filipek S., Krzysko K. A., Fotiadis D., Liang Y., Saperstein D. A., Engel A., Palczewski K. (2004) A concept for G protein activation by G protein-coupled receptor dimers: the transducin/rhodopsin interface. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 3, 628–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Modzelewska A., Filipek S., Palczewski K., Park P. S. (2006) Arrestin interaction with rhodopsin: conceptual models. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 46, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Orban T., Jastrzebska B., Gupta S., Wang B., Miyagi M., Chance M. R., Palczewski K. (2012) Conformational dynamics of activation for the pentameric complex of dimeric G protein-coupled receptor and heterotrimeric G protein. Structure 20, 826–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rasmussen S. G., DeVree B. T., Zou Y., Kruse A. C., Chung K. Y., Kobilka T. S., Thian F. S., Chae P. S., Pardon E., Calinski D., Mathiesen J. M., Shah S. T., Lyons J. A., Caffrey M., Gellman S. H., Steyaert J., Skiniotis G., Weis W. I., Sunahara R. K., Kobilka B. K. (2011) Crystal structure of the beta2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fanelli F., Dell'orco D. (2008) Dark and photoactivated rhodopsin share common binding modes to transducin. FEBS Lett. 582, 991–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Neri M., Vanni S., Tavernelli I., Rothlisberger U. (2010) Role of aggregation in rhodopsin signal transduction. Biochemistry 49, 4827–4832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Filizola M., Wang S. X., Weinstein H. (2006) Dynamic models of G-protein coupled receptor dimers: indications of asymmetry in the rhodopsin dimer from molecular dynamics simulations in a POPC bilayer. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 20, 405–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]