The soluble NTPDase1 from L. pneumophila was crystallized in six crystal forms and the structure was solved using a sulfur SAD approach.

Keywords: NTPDase, CD39, apyrase, nucleotidase, S-SAD

Abstract

Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (NTPDases) are a large class of nucleotidases that hydrolyze the (γ/β)- and (β/α)-anhydride bonds of nucleoside triphosphates and diphosphates, respectively. NTPDases are found throughout the eukaryotic domain. In addition, a very small number of members can be found in bacteria, most of which live as parasites of eukaryotic hosts. NTPDases of intracellular and extracellular parasites are emerging as important regulators for the survival of the parasite. To deepen the knowledge of the structure and function of this enzyme class, recombinant production of the NTPDase1 from the bacterium Legionella pneumophila has been established. The protein could be crystallized in six crystal forms, of which one has been described previously. The crystals diffracted to resolutions of between 1.4 and 2.5 Å. Experimental phases determined by a sulfur SAD experiment using an orthorhombic crystal form produced an interpretable electron-density map.

1. Introduction

NTPDases are a large class of nucleotidases. They catalyze the stepwise removal of the γ- and β-phosphates from nucleoside triphosphates and diphosphates, respectively. For this activity, they strictly require the presence of divalent metal ions. NTPDases have a ubiquitous distribution in the eukaryotic domain (Zimmermann et al., 2012 ▶). They usually reside in the lumen of the ER and Golgi, where they are attached to the membrane by a single-helix anchor and participate in the recycling of the lumenal UDP and GDP produced during protein-glycosylation reactions. In vertebrates, the family of NTPDases has diverged from the ubiquitous form (represented by NTPDase5 and NTPDase6) into two new subgroups characterized by two transmembrane helices close to the N- and C-termini. NTPDase4 and NTPDase7 are thought to reside in lysosomes, but their physiological function has not been well established. NTPDase1–3 and NTPDase8 are located on the cell surface. They are the best characterized NTPDases to date and their impact on vascular haemostasis (Sévigny et al., 2002 ▶; Robson et al., 2005 ▶; Kukulski et al., 2011 ▶), immunoregulation (Mizumoto et al., 2002 ▶; Sauer et al., 2012 ▶), nociception (Vongtau et al., 2011 ▶), development (Zimmermann, 2006 ▶; Massé et al., 2007 ▶) and other functions via their hydrolytic action on extracellular nucleotides has been well established. NTPDase genes have also been cloned from several parasites, including the protozoans Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma spp., Leishmania spp. and Trichomonas vaginalis, the flatworm Schistosoma mansoni and the bacterium Legionella pneumophila, or at least their activity on the cell surface has been demonstrated. The presence of two NTPDase genes in L. pneumophila is intriguing, as these genes are not normally found in bacteria and this might be the result of horizontal gene transfer facilitated by the close association of the parasite with its eukaryotic hosts. In parasites, the NTPDases are thought to serve as a means of suppressing the immune response by the host and in purine salvage (Sansom, 2012 ▶). Indeed, L. pneumophila NTPDase1 has been shown to be required for multiplication in the replicative vacuole (Sansom et al., 2007 ▶). We have previously determined the structure of the catalytic ectodomain (ECD) of Rattus norvegicus NTPDase1 and NTPDase2 and have been able to clarify the disulfide-reductive activation mechanism of the dormant NTPDases from T. gondii (Zebisch & Sträter, 2007 ▶; Zebisch & Sträter, 2008 ▶; Krug et al., 2012 ▶; Zebisch et al., 2012 ▶). Although considerable insight into the structure and function of NTPDases has been gained, several issues remain unresolved. These include the understanding of a domain rotation that is likely to occur in all NTPDases and that is regulated by the transmembrane helices of vertebrate NTPDase1–3 and NTPDase8 as well as the molecular determinants of nucleoside base and nucleoside disphosphate versus triphosphate specificity. We sought to establish a high-level bacterial expression system for L. pneumophila NTPDase1 (LpNTPDase1) to serve as a model NTPDase for functional and structural studies and to help to answer these questions. A structure of LpNTPDase1 has been published previously (Vivian et al., 2010 ▶). However, comparison with other NTPDase structures suggests that the structure presented is that of an open form, with the observed binding mode of a nucleotide analogue in the absence of a divalent metal ion being nonproductive. By using a periplasmic expression system for this secreted disulfide-linked enzyme and by using a C-terminal instead of an N-terminal His tag, we have been able to crystallize the protein in five additional crystal forms. An interpretable electron-density map was obtained from a sulfur SAD experiment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein preparation

The cDNA coding for full-length LpNTPDase1 was kindly provided by Elisabeth L. Hartland (University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia). We cloned the cDNA corresponding to the mature protein sequence of LpNTPDase1 (Asp35–Ala393) into pET20b via the NcoI and XhoI restriction sites (shown in bold in the primer sequences below). For the construct expressing a C-terminal His6 tag, the primers 5′-GG TGT ACC ATG GAC ACT AAC CCC TGT G-3′ and 5′-CGA TAT CTC GAG AGC GCG GTG AAG CAC G-3′ were used. The expected protein sequence before scission of the signal peptide is thus MKYLLPTAAAGLLLLAAQPAMAM DTNPCEK HSCI…HRA LEHHHHHH, with the mature sequence shown in bold and the remaining artificial amino acids shown in italics.

To obtain a construct with an N-terminal His6 tag (Asn37–Ala393) the primers 5′-CG TGT ACC ATG GAC CAT CAT CAT CAT CAT CAT AAC CCC TGT GAA AAA CAC-3′ and 5′-GCA TAT CTC GAG TTA AGC GCG GTG AAG CAC GAC-3′ (His tag and stop codon shown in italics) were used. The calculated protein sequence before scission of the signal peptide is thus MKYLLPTAAAGLLLLAAQPAMAMDHHHHHH NPCEKHSCI…HRA, with the mature sequence shown in bold and the remaining artificial amino acids shown in italics.

The recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta cells. After an initial growth phase at 310 K, the temperature was reduced to 303 K and expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were harvested after 6 h (high cell density fermentation) or after incubation overnight (shaking culture). After harvesting the cells by centrifugation, the proteins could be purified from both the supernatant and the cells. The cleared culture medium was sterile-filtered and buffer-exchanged into lysis buffer (100 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl pH 8.0) using a UFP-10-C-6A hollow-fibre ultrafiltration cartridge (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, England). This solution was directly applied onto the first chromatography column, as described below.

To release the periplasmic protein from the cell pellet, 10 g of cells were resuspended in lysis buffer. Small amounts of DNase I and lysozyme were added together with PMSF and MgCl2 to final concentrations of 0.2 and 3 mM, respectively, and the suspension was stirred at 277 K for 30 min. For full cell disruption, the suspension was further processed by passage through an APV-2000 cell homogenizer (Invensys APV, Albertslund, Denmark). The lysed suspension was cleared by centrifugation at 31 000g for 10 min. The pellet contained large numbers of inclusion bodies. SDS–PAGE analysis showed that the inclusion bodies exclusively contained protein with an unprocessed pelB leader peptide (data not shown). The protein was then purified via a four-step protocol on ÄKTAexplorer or ÄKTAxpress chromatography systems using chromatography columns from GE Healthcare: immobilized metal-affinity chromatography (IMAC), desalting (DS), ion-exchange chromatography (IEC) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). For the first chromatography step, the imidazole concentration in the sample was adjusted to 25 mM by adding IMAC elution buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole pH 8.0) in a 1:20 ratio. After loading the sample at 2 ml min−1, the 5 ml HisTrap HP column was washed with 10–20 column volumes (CV) of equilibration buffer (100 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole pH 8). The protein was eluted with a steep linear gradient over 4 CV and was buffer-exchanged into 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 using a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column before loading onto a 5 ml HiTrap Q HP column. The IEC column was washed with 10 CV of loading buffer and the protein was eluted in a linear gradient to 1 M NaCl over 10 CV. Protein from the major peak was subjected to a HiLoad S200 16/60 pg SEC column equilibrated with 10 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0. For long-term storage (kinetic studies), the protein was stored at 253 K in this buffer supplemented with 50%(v/v) glycerol. For crystallization, the protein was buffer-exchanged into 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM NaN3, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0 using Vivaspin centrifugal concentrators with a molecular-weight cutoff of 10 kDa and was then stored on ice.

2.2. ABD-F analysis of sulfhydryl groups

To determine the content of free cysteine thiol groups, a modification of the ABD-F (7-fluoro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole-4-sulfonamide) labelling method was applied (Kirley, 1989 ▶). We used 5 mM TCEP [tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine] instead of tributylphosphine as a nonmercapto reductant in control reactions. BSA (one free cysteine, 17 disulfide bridges) was used as a standard. After electrophoresis, the gels were fixed in 10%(v/v) acetic acid, 40%(v/v) methanol (a frequently used staining solution, without Coomassie stain), photographed upon exposure to 366 nm UV light, stained with Coomassie and photographed under visible light again. We found that the low pH of the fixing solution greatly improved the fluorescence signal intensities.

2.3. Crystallization

Initial crystallization screening was carried out in 96-well crystallization plates using sparse-matrix crystallization screens and the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method by mixing 200 nl protein solution with an equal volume of crystallization buffer. Protein crystals were distinguished from salt crystals by UV fluorescence using a DUVI 204 instrument (RiNA GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Crystallization conditions were optimized in 12-well PVC (polyvinyl chloride) trays (Nelipak, Venray, Netherlands) using the hanging-drop (e.g. 1–2 µl protein solution plus 1–2 µl reservoir solution) vapour-diffusion method.

LpNTPDase1 crystallized in a variety of conditions. We were unable to reproduce crystals of this enzyme with an N- or C-terminal His tag using the previously published conditions (Vivian et al., 2010 ▶). However, crystallization in this crystal form (denoted here as crystal form I) was achieved using a high concentration of N-terminally His-tagged LpNTPDase1 (17 mg ml−1) in 30%(w/v) PEP 629 (pentaerythritol propoxylate 17/8 PO/OH), 100 mM HEPES–NaOH pH 7.7, 50 mM MgCl2.

Crystals of form II (monoclinic) appeared in 100 mM MES–NaOH pH 5.0–6.0, 10–20%(w/v) PEG 3350 at protein concentrations of between 4 and 6 mg ml−1. The crystal morphology often improved on the addition of 100–200 mM MgCl2. Under these conditions, crystals of form III (orthorhombic) were also obtained. Generally, this crystal form was favoured at an acidic pH of between 3.0 and 5.5. Crystallization in forms II and III was improved using microseeding. Crystals of forms II and III were cryoprotected by a stepwise increase of the PEG 3350 concentration to 20%(w/v) and the addition of glycerol or PEG 200 to 20%(v/v).

Crystals of form IV (hexagonal) appeared in 100 mM HEPES–NaOH pH 7.5, 1.4 M ammonium sulfate at a protein concentration of 6 mg ml−1. Before cooling, sodium malonate pH 7.5 was added stepwise to a concentration of 2 M. Crystals of the trigonal crystal form V were obtained in 14%(w/v) PEG 3350, 200 mM KBr, 100 mM MES–NaOH pH 6.4 using protein at 5 mg ml−1. For cryoprotection of these crystals, PEG 200 was added in a stepwise manner to 18%(v/v).

Crystal form VI was only obtained in the presence of the NTPDase inhibitor POM-1 [sodium polytungstate, Na6(H2W12O40), approximately 10 mM; Müller et al., 2006 ▶] in 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.3, 200 mM potassium/sodium tartrate, 18%(w/v) PEG 3350. To flash-cool these crystals, the PEG 3350 concentration was increased to 25%(w/v) and PEG 200 was added to 10%(v/v). Crystal forms II–IV were only obtained using the C-terminally His-tagged protein.

2.4. Data collection and processing

Data sets were collected on beamlines 14.1 and 14.2 at PSF/BESSY (Mueller et al., 2012 ▶). For the rod-shaped crystals of form VI, the multiplicity of the measured reflections could be increased by exposing several sections of the crystal. X-ray data sets were integrated using XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▶). Amplitudes were scaled and converted to structure factors using SCALA/CTRUNCATE (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Based on the L-test for twinning as implemented in SCALA (Evans, 2006 ▶), a large twinning fraction was predicted for crystal form IV and a minor twinning fraction was predicted for crystals of form V.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Protein preparation

L. pneumophila NTPDase1 is a secreted protein that is required for the intracellular multiplication of the parasite within the host cell (Sansom et al., 2007 ▶). The predicted mature sequence of LpNTPDase1 contains six cysteines, the last four of which form two disulfide bridges that are conserved among all NTPDases (Zimmermann et al., 2012 ▶). To mimic the natural expression pathway and to facilitate the oxidative formation of disulfides, we established a periplasmic expression system for LpNTPDase1. We observed strong periplasmic expression of the mature sequence of LpNTPDase1 cloned into the expression vector pET22b. The protein could be purified from the cleared medium and from lysed cells. We could reproducibly obtain more than 30 mg protein from a 10 g wet cell pellet and the same amount could be purified from the cleared culture supernatant.

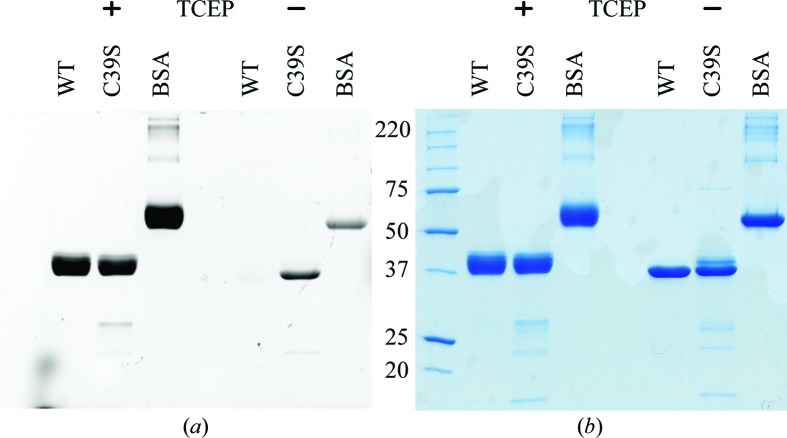

To establish whether the two N-terminal cysteines form a disulfide bridge or exist as free sulfhydryls, we used the ABD-F labelling method for free cysteines (Fig. 1 ▶). This analysis shows that LpNTPDase1 has no free cysteines. As the protein is a monomer on gel filtration and on nonreducing SDS–PAGE, residues Cys39 and Cys44 of the secreted LpNTPDase1 must therefore form a disulfide bridge. This is in contrast to the structure of LpNTPDase1 in crystal form I, in which Cys44 is modelled as a free cysteine and the protein model starts with Lys41 (Vivian et al., 2010 ▶). However, in at least one of the deposited structures (PDB entry 3aap) residual density is present around the N-terminus that might have allowed modelling of residues Cys39 and Glu40 and the disulfide bridge. We suspect that the incomplete formation of this disulfide in this structure was a consequence of the cytosolic expression.

Figure 1.

ABD-F labelling of free cysteines. (a) Inverted fluorescence image; (b) Coomassie-stained gel. 5 µg of wild-type LpNTPDase1, the C39S variant and BSA were subjected to reducing (plus TCEP) and nonreducing SDS–PAGE. Under reducing conditions all samples showed strong fluorescence. Under nonreducing conditions the wild type gives no signal, demonstrating that no free cysteine is present. However, the signal of the C39S variant is comparable to that of BSA (one free cysteine), indicating that a single free cysteine (i.e. Cys44) is present. The signal is slightly higher than that of BSA because the NTPDase has a higher molar concentration in the 5 µg loaded sample.

3.2. Crystallization

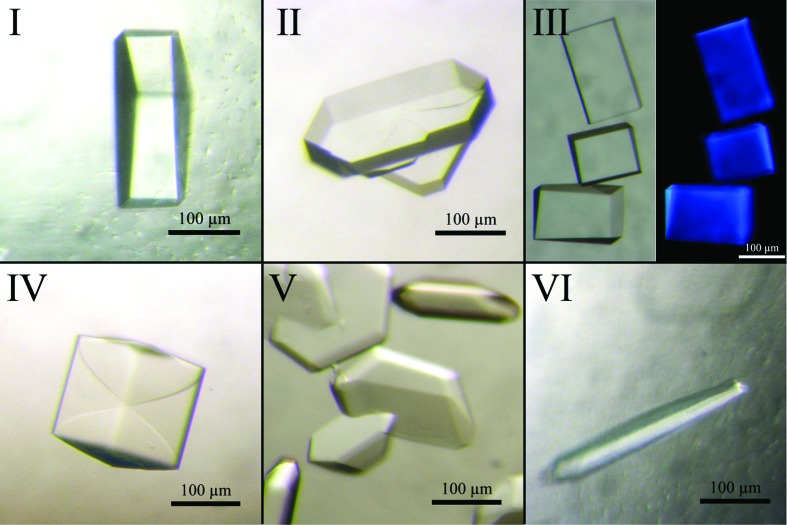

Using protein with a C-terminal or an N-terminal His6 tag, we obtained crystallization hits in many different conditions. The initial crystallization conditions were optimized by varying the pH, the types and concentrations of salt and the precipitant in the reservoir solution. The crystallization morphology improved greatly using microseeding. Crystal seeds proved to be stable in the reservoir solution and initial stocks had to be diluted up to 400 000-fold. As confirmed by X-ray diffraction (see below), crystals could be obtained in six different crystal forms (Fig. 2 ▶). Notably, crystals of the previously characterized form I could only be obtained using protein carrying an N-terminal His6 tag. Crystal forms II, III and IV were only obtained using protein with a C-terminal His6 tag. Crystals of form VI often formed long and hollow hexagonal tubes which were filled at only one end of the crystal.

Figure 2.

Crystal forms obtained for LpNTPDase1. Crystal form I corresponds to the crystal form described in a previous paper. Crystal forms IV and V showed partial twinning. Crystals of form VI only formed in the presence of the NTPDase inhibitor POM-1. Generally, crystals showed a high fluorescence upon UV radiation (shown for crystal form III).

3.3. Data collection and preliminary crystallographic analysis

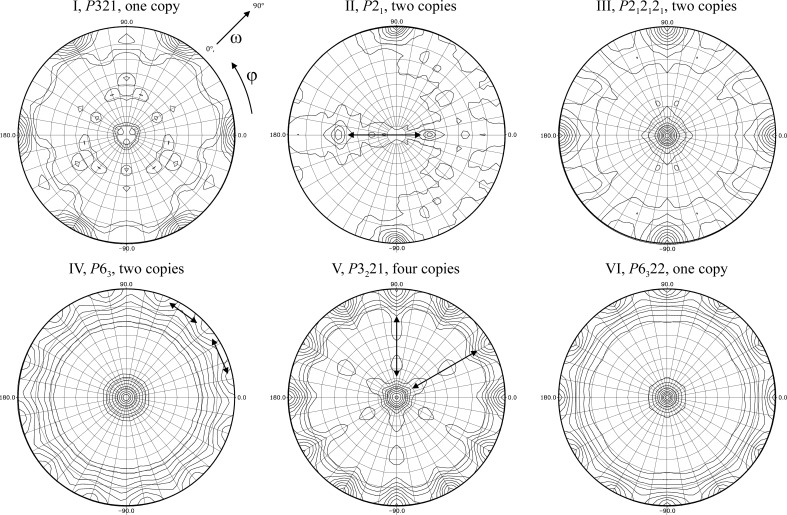

The crystals of LpNTPDase1 generally diffracted very well, with crystal forms I, II and III achieving the highest resolution (Table 1 ▶). Using the MATTHEWS_COEF program from the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) and a calculated molecular weight of 41.8 kDa, we estimated the number of monomers per asymmetric unit (Table 1 ▶). Crystal forms II, III and IV appeared to contain two copies per asymmetric unit. The previously described crystal form I and crystal form VI each contained one copy in the asymmetric unit. Crystal form V, which has the largest volume of the asymmetric unit, is likely to contain four copies. We did not observe peaks in the native Patterson functions (data not shown). We tested whether a dimeric arrangement with rotational C 2 symmetry of the expected two or four monomers in space groups II to V revealed itself in a self-rotation function. A C 2-symmetrical dimer should be visible in the κ = 180° sections, but the NCS peaks may coincide with crystallographic evenfold symmetry axes. The self-rotation functions were calculated using the CCP4 program POLARRFN (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Indeed, peaks corresponding to noncrystallographic evenfold symmetry axes could be identified for crystal forms II, IV and V (Fig. 3 ▶). Based on the similar length of the c axis and the similarity of the self-rotation functions, it seems likely that crystal forms IV and VI are related such that the NCS axes of form IV have become crystallographic twofolds in form VI. This could be owing to a conformational change induced or stabilized by POM-1 binding.

Table 1. Data-collection statistics for the six crystal forms of LpNTPDase1.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Crystal form | I | II | III | IV | V | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position of His tag | N | C | C | C | C | N |

| X-ray source | BL14.1, BESSY | BL14.2, BESSY | BL14.2, BESSY | BL14.2, BESSY | BL14.2, BESSY | BL14.1, BESSY |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9181 | 1.21435 | 1.9 | 0.9181 | 0.9181 | 0.9181 |

| Space group | P321 | P21 | P212121 | P63 | P3221 | P6322 |

| Unit-cell parameters | ||||||

| a (Å) | 103.88 | 62.51 | 79.97 | 155.99 | 129.71 | 143.69 |

| b (Å) | 103.88 | 86.19 | 84.31 | 155.99 | 129.71 | 143.69 |

| c (Å) | 75.40 | 72.22 | 102.11 | 79.22 | 162.56 | 75.17 |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 | 107.13 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| γ (°) | 120 | 90 | 90 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 15.8 | 14.6 | 23.0 | 25.1 | 66.0 | 17.5 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 28.89–1.40 (1.48–1.40) | 29.21–1.40 (1.48–1.40) | 32.51–2.02 (2.13–2.02) | 34.17–1.99 (2.10–1.99) | 29.36–2.50 (2.65–2.50) | 29.38–1.70 (1.84–1.70) |

| Unique reflections | 92381 (13418) | 138132 (15705) | 43436 (5681) | 74335 (10249) | 55117 (7966) | 50327 (7103) |

| Average multiplicity | 6.2 (6.1) | 4.5 (3.1) | 14.2 (7.3) | 5.7 (4.5) | 6.3 (6.3) | 14.5 (4.3) |

| Anomalous multiplicity | 3.2 (3.1) | 2.3 (1.6) | 7.4 (3.8) | 2.9 (2.3) | 3.3 (3.2) | 7.6 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 96.2 (75.1) | 94.4 (86.0) | 99.1 (94.1) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.3 (97.7) |

| Anomalous completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 85.5 (61.5) | 94.2 (85.2) | 97.5 (85.3) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.4 (97.7) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 16.2 (2.2) | 21.0 (3.7) | 41.3 (10.8) | 6.9 (2.3) | 11.8 (2.2) | 18.1 (2.3) |

| R merge (%) | 5.2 (74.0) | 3.6 (23.3) | 4.3 (15.7) | 13.7 (44.8) | 8.6 (76.9) | 10.3 (56.1) |

| R meas (all) (%) | 6.1 (89.8) | 4.3 (33.0) | 4.7 (18.0) | 16.0 (57.5) | 10.2 (91.9) | 12.1 (74.0) |

| R p.i.m. (all) (%) | 2.4 (36.2) | 1.8 (18.4) | 1.2 (6.5) | 6.5 (26.0) | 4.0 (36.3) | 3.0 (35.0) |

| R anom (%) | 2.3 (36.2) | 1.8 (21.2) | 1.5 (6.2) | 5.5 (30.8) | 3.7 (33.8) | 5.9 (35.1) |

| Molecules per asymmeric unit | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Solvent content (%) | 56 | 41 | 40 | 45 | 48 | 54 |

Figure 3.

Self-rotation functions of the six crystal forms using diffraction data from 20 to 3 Å resolution. The κ = 180° sections are shown (searching for twofold axes). For all stereographic projections the axes are x = a (horizontal axis with ϕ = 0° in the equator plane), y = c* × a (at ϕ = 90°) and z = c* (towards the north pole). ω describes the deviation of an axis from the c* direction and ϕ the angular deviation from the x axis in the equator plane as indicated in the projection for crystal form I. Peaks that are related by a combination with a perpendicular evenfold symmetry axis are indicated by double arrows. Crystal form I, P321: only crystallographic peaks can be found, most likely because only a single protein is present in the asymmetric unit. Crystal form II, P21: two perpendicular twofold NCS axes are visible (double arrows, at ω = 56.4, ϕ = 180° and ω = 33.6, ϕ = 0°) with a height of 47% of the origin peak. Both NCS axes are also oriented perpendicular to the crystallographic 21 axis, i.e. the NCS peaks are related by a combination of the crystallographic and NCS axes. Crystal form III, P212121: no clear peaks are visible in addition to the three crystallographic twofold axes. Either no noncrystallographic rotational symmetry exists or a twofold axis runs almost parallel to a crystallographic axis. Based on the solvent content (Table 1 ▶), it is highly unlikely that there is only one monomer per asymmetric unit. Crystal form IV, P63: strong twofold NCS peaks (peak height 88% of the origin peak) are found at ω = 90.0, ϕ = 11 + n × 30°. The twofold axes in the equator plane are related by either the sixfold symmetry or a combination of the twofold NCS axis with the perpendicular sixfold axis. Crystal form V, P3221: the expected crystallographic peaks are the same as in crystal form I. Additional strong NCS peaks (peak height 83%) are visible at ω = 0.0° and at ω = 90.0, ϕ = 30 + n × 60° (double arrows). Again, these peaks are related by a combination with the crystallographic dyads. Crystal form VI, P6322: only the crystallographic peaks are visible, which is in agreement with the presence of a single monomer in the asymmetric unit (Table 1 ▶).

Encouraged by the good diffraction propensity, we tested the feasibility of de novo sulfur SAD phasing of the structure. We chose a wavelength of 1.9 Å at the tuneable-wavelength beamline 14.2 at PSF/BESSY. Sulfur SAD experiments had previously been conducted successfully at this wavelength (Lakomek et al., 2009 ▶). An LpNTPDase1 crystal of the orthorhombic form III was positioned 90 mm (almost at the minimum distance) from the detector to allow the collection of high-resolution spots. Other well diffracting high-symmetry crystal forms were obtained at a later stage.

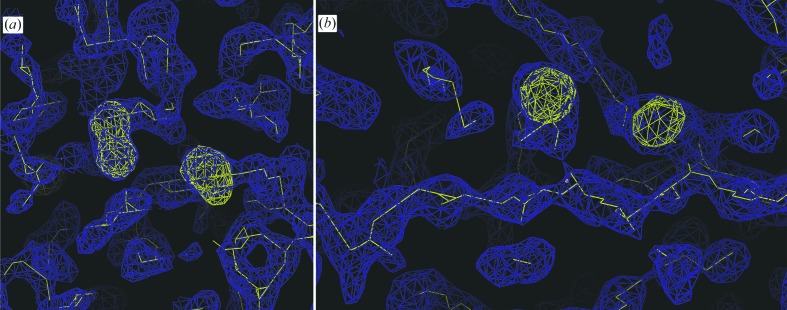

A data set was collected to high multiplicity. 1000 frames were recorded with an oscillation of 1° per frame and an exposure time of 6 s. Care was taken not to overload any reflections. Most likely owing to progressive radiation damage, it proved to be advantageous in the following steps to truncate the data set after 400 frames. The data set had moderate anomalous multiplicity but a very high signal-to-noise ratio (Table 1 ▶). The ratio between R anom and R p.i.m. fell to below 1.0 at 2.1 Å resolution, indicating that significant phase information was available to high resolution (Lakomek et al., 2009 ▶). The scaled data set was subjected to a SAD experiment in autoSHARP (Vonrhein et al., 2007 ▶), searching for 16 sites per monomer (nine methionines, six cysteines and one active-site sulfate were expected, with two monomers per asymmetric unit). 35 sites were found by SHELXD (Sheldrick, 2008 ▶), of which 32 were used for phasing. The phasing power for acentric reflections was 0.66 before density modification and dropped below 1.0 at a resolution of 3.0 Å. The figure of merit (FOM) for the phases of acentric reflections was 0.25 for the complete data set and 0.08 in the highest resolution shell. After density modification by SOLOMON, traceable electron density was obtained (Fig. 4 ▶). Model building and structural refinement are now in progress. Notably, it was not necessary to perform NCS averaging using operators derived from the anomalous peaks.

Figure 4.

Experimental electron density after solvent flattening drawn in blue and contoured at 1.5σ. Anomalous sites calculated using the initial phases are shown in yellow and contoured at 4σ. (a) The two adjoining peaks with elongated shape may represent the two canonical disulfide bridges of NTPDase1 in the C-terminal domain. (b) Two spherical anomalous peaks lying close to a stretch of electron density that is likely to represent a β-strand. This could be the MDM sequence in the C-terminal domain of the protein that participates in active-site formation. The figures were prepared using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶).

As stated above, the previous structure of LpNTPDase1 is that of an open form with a nonproductive binding mode of the nucleotide mimic (Vivian et al., 2010 ▶; Zimmermann et al., 2012 ▶). It appears likely that catalytically competent closed forms of LpNTPDase1 exist which show an active-site arrangement similar to previous NTPDase structures from other species (Zebisch & Sträter, 2008 ▶; Krug et al., 2012 ▶; Zebisch et al., 2012 ▶). A comparison of high-resolution protein structures in open and closed forms will provide a basis for the description of the anticipated domain-closure motion in unprecedented detail. The crystallization of the bacterial NTPDase in five new crystal forms, often with several copies in the asymmetric unit, is expected to give rise to 11 potentially independent observations of the protein. The chance is therefore high that new insights into enzyme dynamics will be provided, for example by obtaining a closed form. Crystal form VI might provide new information on NTPDase inhibition by polyoxometallates. The observation of a strong anomalous signal in crystal form VI (Table 1 ▶) substantiates the notion that the metal cluster has indeed bound. We are planning soaking trials in order to obtain complex structures with various nucleotide analogues in order to study the determinants of base specificity and specificity for the phosphate-tail length.

Acknowledgments

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is acknowledged for financial support of this project under grant STR 477/10. We thank PSF/BESSY of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin and EMBL/DESY (Hamburg) for beam time and travel support and the staff for support at the beamlines. We would like to thank Johann Moschner, Christian Roth and Michael Zahn for their support.

References

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kirley, T. L. (1989). Anal. Biochem. 180, 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krug, U., Zebisch, M., Krauss, M. & Sträter, N. (2012). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3051–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kukulski, F., Bahrami, F., Ben Yebdri, F., Lecka, J., Martín-Satué, M., Lévesque, S. A. & Sévigny, J. (2011). J. Immunol. 187, 644–653. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lakomek, K., Dickmanns, A., Mueller, U., Kollmann, K., Deuschl, F., Berndt, A., Lübke, T. & Ficner, R. (2009). Acta Cryst. D65, 220–228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Massé, K., Bhamra, S., Eason, R., Dale, N. & Jones, E. A. (2007). Nature (London), 449, 1058–1062. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mizumoto, N., Kumamoto, T., Robson, S. C., Sévigny, J., Matsue, H., Enjyoji, K. & Takashima, A. (2002). Nature Med. 8, 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mueller, U., Darowski, N., Fuchs, M. R., Förster, R., Hellmig, M., Paithankar, K. S., Pühringer, S., Steffien, M., Zocher, G. & Weiss, M. S. (2012). J. Synchrotron Rad. 19, 442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Müller, C. E., Iqbal, J., Baqi, Y., Zimmermann, H., Röllich, A. & Stephan, H. (2006). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 5943–5947. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robson, S. C., Wu, Y., Sun, X., Knosalla, C., Dwyer, K. & Enjyoji, K. (2005). Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 31, 217–233. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sansom, F. M. (2012). Parasitology, 139, 963–980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sansom, F. M., Newton, H. J., Crikis, S., Cianciotto, N. P., Cowan, P. J., d’Apice, A. J. & Hartland, E. L. (2007). Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1922–1935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sauer, A. V., Brigida, I., Carriglio, N., Hernandez, R. J., Scaramuzza, S., Clavenna, D., Sanvito, F., Poliani, P. L., Gagliani, N., Carlucci, F., Tabucchi, A., Roncarolo, M. G., Traggiai, E., Villa, A. & Aiuti, A. (2012). Blood, 119, 1428–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sévigny, J., Sundberg, C., Braun, N., Guckelberger, O., Csizmadia, E., Qawi, I., Imai, M., Zimmermann, H. & Robson, S. C. (2002). Blood, 99, 2801–2809. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vivian, J. P., Riedmaier, P., Ge, H., Le Nours, J., Sansom, F. M., Wilce, M. C., Byres, E., Dias, M., Schmidberger, J. W., Cowan, P. J., d’Apice, A. J., Hartland, E. L., Rossjohn, J. & Beddoe, T. (2010). Structure, 18, 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vongtau, H. O., Lavoie, E. G., Sévigny, J. & Molliver, D. C. (2011). Neuroscience, 193, 387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vonrhein, C., Blanc, E., Roversi, P. & Bricogne, G. (2007). Methods Mol. Biol. 364, 215–230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Zebisch, M., Krauss, M., Schäfer, P. & Sträter, N. (2012). J. Mol. Biol. 415, 288–306. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zebisch, M. & Sträter, N. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 11945–11956. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zebisch, M. & Sträter, N. (2008). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 6882–6887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, H. (2006). Eur. J. Physiol. 452, 573–588. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, H., Zebisch, M. & Sträter, N. (2012). Purinergic Signal. 8, 437–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]