Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a complex disease, leading to the damage of multisystems. The pathogen that triggers this sophisticated disease is still unknown since it was first reported in 1967. To increase our knowledge on the effects of genes in KD, we extracted statistically significant genes so far associated with this mysterious illness from candidate gene studies and genome-wide association studies. These genes contributed to susceptibility to KD, coronary artery lesions, resistance to initial IVIG treatment, incomplete KD, and so on. Gene ontology category and pathways were analyzed for relationships among these statistically significant genes. These genes were represented in a variety of functional categories, including immune response, inflammatory response, and cellular calcium ion homeostasis. They were mainly enriched in the pathway of immune response. We further highlighted the compelling immune pathway of NF-AT signal and leukocyte interactions combined with another transcription factor NF-κB in the pathogenesis of KD. STRING analysis, a network analysis focusing on protein interactions, validated close contact between these genes and implied the importance of this pathway. This data will contribute to understanding pathogenesis of KD.

1. Introduction

KD is a systemic vascular disease preferentially occurring in infants and children [1, 2]. It is characterized by the development of coronary artery aneurysms (CAA) which may result in fatal thrombosis and sudden cardiac failure. Clinical manifestations of KD include prolonged fever (1-2 weeks, mean 10-11 days), conjunctival infection, oral lesions, polymorphous skin rashes, extremity changes, and cervical lymphadenopathy, all of which comprise diagnostic criteria [3]. However, great majority of children failed to manifest typical characteristics. In addition to the diagnostic criteria, there are a broad range of nonspecific clinical features, including irritability, uveitis, aseptic meningitis, cough, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, gallbladder hydrops, urethritis, arthralgia, arthritis, hypoalbuminemia [4], liver function impairment, and heart failure [5, 6]. The peaked incidence at 9 to 11 months of age coincides with fading of maternal immunity, and symptoms partly similar to other infectious disorders suggest that some microorganisms may trigger this disease. Despite great efforts to identify the cause for nearly a half a century, the etiology of KD still remains unknown [7]. However, the role of genetic susceptibility to KD has long been evident through its striking predilection for children of Japanese ethnicity regardless of their country of residence; compared with Caucasian children, Japanese children have a relative risk of KD that is 10 to 15 times higher [8–10]. Siblings of KD children have a relative risk that is 6 to 10 times greater than that of children without a family history, and the parents of Japanese children with KD are twice as likely to have had KD themselves as children than other adults in the general Japanese population [11–14].

Candidate gene studies and genome-wide studies have been successively applied to explore the association between genetic effect and this mysterious disease [15, 16]. Many suspicious genes related to innate and acquired immune functions or to vascular remodeling have been studied [15, 17–19]. Genetic studies of KD were conducted not only to clarify the genetic background but also in the hope of providing clues about its etiology and pathogenesis. However, none of these studies have analyzed the internal association between these significant association genes and explored the possible pathogenic process in KD from overall level.

In this paper, we aim to extract statistically significant genes associated with KD (Up to September 2012, from all English databases) to explore their association and analyze their function in the pathogenesis of KD. This study is a systematic summary of previous research. Further studies on clinical validation will be summarized in our next study.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Extracting Genes with Statistical Significance

We performed a computerized search of Ovid, Google Scholar, and PubMed databases up to September 2012 and reviewed cited references to identify the relevant studies. Citations were screened at the title/abstract level and retrieved as full reports. Search keywords were “Kawasaki disease,” “Kawasaki syndrome,” “lymph node syndrome,” “mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome” combined with “polymorphism,” “gene,” “genetic,” “allele,” and “genotype”. The inclusion criteria of genes were those who have significant association with KD contributed to susceptibility, vascular lesions, resistance to initial IVIG treatment, late diagnosis of KD, and incomplete KD.

2.2. Data Analysis

DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/, version: 6.7) was used to process the bioinformatics analysis of these candidate gene markers, including gene classification (based on Biological Process Ontology and Molecular Function Ontology, resp.), enrichment analysis for significant gene ontology categories, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway mapping, and significant pathway computing. GeneGo MetaCore (http://www.genego.com/, version: 6.5) was used to analyze the pathways of these significant genes. The association between these statistically significant genes were analyzed using STRING (http://string-db.org/), a database of known and predicted protein interactions.

3. Results

3.1. Extracting Genes with Statistical Significance

The characteristics of the genes are presented in Table 1 (candidate genetic studies) and Table 2 (genome-wide studies).

Table 1.

Candidate gene studies identified genes associated with KD.

| Symbol | Region | Phenotype | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD40 | 20q12-q13.2 | KD | Taiwan | [20] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [20] | ||

| CD209 | 19p13 | KD | Taiwan | [21] |

| RETN | 19p13.2 | Incomplete KD | China | [22] |

| KD | United States | [23] | ||

| CAL | Japan | [24] | ||

| FCGR3B | 1q23 | IVIG nonresponse | United States | [23] |

| NOD1 | 7p15-p14 | KD | Japan | [25] |

| NLRP1 | 17p13.2 | KD | Japan | [25] |

| ITPKC | 19q13.1 | KD | Taiwan; Japan; China | [26–28] |

| CAL | Japan | [29] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | Japan | [29] | ||

| TGFBR2 | 3p22 | KD | European descent; Korea | [30, 31] |

| CAL | European descent; Korea | [30, 31] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | European descent | [30] | ||

| aortic root dilatation, | European descent | [30] | ||

| ABO | 9q34.2 | CAL | Japan | [32] |

| PELI1 | 2p13.3 | CAL | Korea | [33] |

| SMAD3 | 15q22.33 | KD | European descent; Taiwan | [30, 34] |

| CAL | European descent | [30] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | European descent | [30] | ||

| aortic root dilatation | European descent | [30] | ||

| TGFB2 | 1q41 | KD | European descent; Taiwan | [30, 34] |

| CAL | European descent | [30] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | European descent | [30] | ||

| aortic root dilatation, | European descent | [30] | ||

| CASP3 | 4q34 | CAL | Taiwan; Japan | [29, 35] |

| IVIG nonresponse | Japan | [29] | ||

| ANGPT1 | 8q23.1 | KD | Netherlands | [36] |

| VEGFA | 6p12 | KD | Netherlands; Taiwan; The Netherlands. | [36–38] |

| CAL | Japan | [39] | ||

| MICB | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [40] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [40] | ||

| MICA | 6p21.33 | KD | Taiwan | [40] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [41] | ||

| BAG6 | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [40, 42] |

| CAA | Taiwan | [42] | ||

| MSH5 | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [40] |

| VWA7 | 6p21.33 | KD | Taiwan | [40] |

| FCGR2B | 1q23 | IVIG nonresponse | Pacific Northwest | [43] |

| IL10 | 1q31-q32 | KD | Taiwan | [44, 45] |

| CAL | China; Korea; Taiwan | [18, 46, 47] | ||

| CCL5 | 17q11.2-q12 | CAL | India | [48] |

| TNFRSF1A | 12p13.2 | KD | China | [49] |

| CTLA4 | 2q33 | CAL (particularly in female patients) | Taiwan | [50] |

| MMP3 | 11q22.3 | CAL | Korea; US-UK, tested in Japan | [51, 52] |

| MMP12 | 11q22.3 | CAL | US-UK, tested in Japan | [52] |

| FGB | 4q28 | CAL | China | [53] |

| CCL3L1 | 17q21.1 | KD | USA; Japan | [54, 55] |

| IVIG nonresponse | Japan | [55] | ||

| CCR5 | 3p21.31 | KD | USA; The Netherlands (Dutch Caucasian); Korea | [54, 56, 57] |

| CAL | Japan | [55] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | Japan | [55] | ||

| PRRC2A | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [42] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [42] | ||

| ABHD16A | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [42] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [42] | ||

| ITPR3 | 6p21 | CAL | Taiwan | [58] |

| COL11A2 | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [59] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [59] | ||

| MBL2 | 10q11.2 | KD | China; Japan | [60, 61] |

| CAL | The Netherlands; The Netherlands | [62, 63] | ||

| Arterial stiffness | China | [64] | ||

| MMP11 | 22q11.23 | KD | Korea | [65] |

| MIF | 22q11.23 | CAL | Italy | [66] |

| IL1B | 2q14 | IVIG nonresponse | Taiwan | [17] |

| BTNL2 | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [67] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [67] | ||

| TPH2 | 12q21.1 | CAL | Korea | [68] |

| PDCD1 | 2q37.3 | KD | Korean | [69] |

| IL18 | 11q22.2-q22.3 | KD | Taiwan | [70, 71] |

| HLA-E | 6p21.3 | KD | Taiwan | [72] |

| CAL | Taiwan | [72] | ||

| TIMP4 | 3p25 | CAL | Korea | [73] |

| HLA-G | 6p21.3 | KD | Korea | [74] |

| CRP | 1q21-q23 | KD | China | [75] |

| Carotid stiffness and carotid intima-media thickness | China | [75] | ||

| TNF | 6p21.3 | KD | China | [75] |

| CAL | white | [76] | ||

| Intima-media thickness | China | [75] | ||

| IVIG nonresponse | China | [46] | ||

| MMP13 | 11q22.3 | CAL | Japan | [77] |

| HLA-B | 6p21.3 | KD | Korea | [78] |

| HLA-C | 6p21.3 | KD | Korea | [78] |

| CCR3 | 3p21.3 | KD | Netherlands (Dutch Caucasian) | [56] |

| CCR2 | 3p21.31 | KD | Netherlands (Dutch Caucasian) | [56] |

| TIMP2 | 17q25 | CAL | Japan | [79] |

| ACE | 17q23.3 | KD | Taiwan; Korea | [80, 81] |

| Coronary artery stenosis | Japan | [82, 83] | ||

| Myocardial ischemia | Japan | [82] | ||

| PLA2G7 | 6p21.2-p12 | IVIG nonresponse | Japan | [84] |

| IL1RN | 2q14.2 | KD | Taiwan | [85] |

| IL4 | 5q31.1 | KD | USA | [86] |

| KDR | 4q11-q12 | CAL | Japan | [39] |

| CD40LG | Xq26 | CAL: males affected | Japan | [87] |

| AGTR1 | 3q24 | Coronary artery stenosis and myocardial ischemia | Japan | [82] |

| CD14 | 5q31.1 | CAL | Japan | [88] |

| SLC11A1 | 2q35 | KD | Japan | [89] |

| LTA | 6p21.3 | KD | white | [76] |

| MTHFR | 1p36.3 | CAL | Japan | [90] |

| HP | 16q22.2 | late diagnosis of KD | Taiwan | [90] |

KD: kawasakidisease;CAL: coronary artery lesions; CAA: coronary artery aneurysms.

Table 2.

Susceptibility genes for KD identified with association at genome-wide significance.

| Gene | Locus | Methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCGR2A | 1q23 | GWAS | [91] |

| BLK | 8p23-p22 | GWAS | [92, 93] |

| CASP3 | 4q34 | Genome wide Linkage analysis | [94] |

| ITPKC | 19q13.1 | Genome wide Linkage analysis; linkage disequilibrium mapping | [94, 95] |

| CD40L | Xq26 | Genome wide Linkage analysis | [94] |

| CD40 | 20q12-q13.2 | GWAS | [92, 93] |

| HLA-DQB2 | 6p21 | GWAS | [92] |

| HLA-DOB | 6p21.3 | GWAS | [92] |

| NFKBIL1 | 6p21.3 | GWAS | [92] |

| LTA | 6p21.3 | GWAS | [92] |

| NAALADL2 | 3q26.31 | GWAS | [96] |

| ZFHX3 | 16q22.3 | GWAS | [96] |

| DAB1 | 1p32-p31 | GWAS | [97] |

| PELI1 | 2p13.3 | GWAS | [97] |

| COPB2 | 3q23 | GWAS | [98] |

| ERAP1 | 5q15 | GWAS | [98] |

| IGHV | 14q32.33 | GWAS | [98] |

| ABCC4 | 13q32 | Genome-wide linkage and association mapping | [99] |

GWAS: genome-wide association study.

3.2. Gene Ontology Analysis

Genes with statistical significance were submitted to functional analysis using DAVID software. Defense response, response to wounding, and inflammatory response were identified as significantly enriched (Enrichment Score = 15.91). Furthermore, DAVID analysis identified clusters of genes with annotations related to cellular calcium ion homeostasis, cell chemotaxis (enrichment Score: 3.75), and positive regulation of immune system process (Enrichment Score: 3.58) which is involved in autoimmune thyroid disease (hsa05320), asthma (hsa05310), type I diabetes mellitus (hsa04940), and allograft rejection (hsa04672). The functional annotation table can be available in supplementary material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/989307.

3.3. Enrichment Analysis

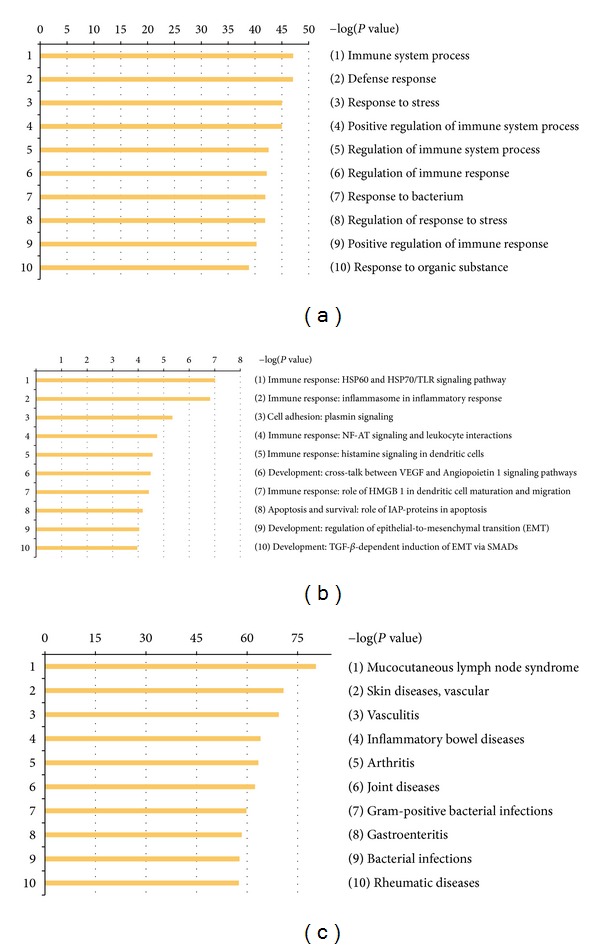

Enrichment analysis consists of matching genes in functional ontologies by GeneGo MetaCore (Figure 1). The probability of a random intersection between a set of gene list with ontology entities was estimated with the “P” value of the hypergeometric intersection. A lower “P” value means higher relevance of the entity to the dataset, which appears in higher rating for the entity. All maps were drawn by GeneGo. The height of the histogram corresponded to the relative expression value for a particular gene.

Figure 1.

Enrichment analysis of the genes by GeneGo MetaCore: (a) GO Processes, (b) Go Pathway Maps, (c) Go Diseases (by Biomarkers). MetaCore version 6.11 build 41105.

The most significant GeneGo Pathway Maps were (1) immune response: HSP60 and HSP70/TLR signaling pathway; (2) immune response: Inflammasome in inflammatory response; (3) cell adhesion: plasmin signaling; (4) immune response: NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions. In addition, there are other pathways including Role of HMGB1 in dendritic cell maturation and migration; histamine signaling in dendritic cells: plasmin signaling in cell adhesion; cross-talk between VEGF and angiopoietin 1 signaling pathways; regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT); TGF-beta-dependent induction of EMT via SMADs in Development; role of IAP-proteins in apoptosis pathway in apoptosis and survival, and so forth. Meanwhile, immune system process, defense response, and response to stress were the most significantly enriched GO processes of these genes. With the disease folders, representing over 112 human diseases annotated by GeneGo, these 76 genes were mainly related to autoimmune diseases and some kinds of vascular inflammatory diseases.

The abstracted genes involved in significant pathways are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pathways analyzed by GeneGo Meta core.

| Pathway categories | Pathways | Functions | Enrichment genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune response | (1) HSP60 and HSP70/TLR signaling pathway (2) Inflammasome in inflammatory response (3) NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions (4) Role of HMGB1 in dendritic cell maturation and migration (5) Histamine signaling in dendritic cells (6) CD16 signaling in NK cells (7) MIF in innate immunity response (8) Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (9) HMGB1 release from the cell (10) PGE2 signaling in immune response (11) Histamine H1 receptor signaling in immune response (12) Role of DAP12 receptors in NK cells |

Pro-inflammatory response and anti-inflammatory response; cellular and humoral immune response; NO production; apoptosis and antiapoptosis; secretion of leukotrienes and prostaglandins; proliferation and differentiation of eosinophils; chemotaxis; proliferation, differentiation, activation of T cell; cell necrosis; smooth muscle construction; vascular permeability; blood coagulation; cytoskeleton remodeling | CD14, HSP70, IL-10, TNF-α, IL-1β, CD40, MHC class I, IL-4, NOD1, CARD7, IL-18, TNF-R1, CD40L, IP3receptor, CCL5, HLA-E, PLA2, MIF, CCR5, MMP13, HLA-C, HLA-B, HLA-G, HLA-E, Stromelysin-1 |

|

| |||

| Cell adhesion | Plasmin signaling ECM remodeling |

Fibrinolysis; cell viability | TGF-β 2,VEGF-A, TGF-β receptor type 2, VEGFR-2, Fibrinogen, MMP-13, TIMP2, Stromelysin-1, MMP-13, MMP-12 |

|

| |||

| Development | (1) Cross-talk between VEGF and Angiopoietin 1 signaling pathways (2) Regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (3) TGF-β-dependent induction of EMT via SMADs (4) PEDF signaling (5) Glucocorticoid receptor signaling |

Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion; epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; proteasomal degradation; inhibition of angiogenesis; immune response | VEGF-A, VEGFR-2, Angiopoietin 1, IP3 receptor, TGF-β 2, IL-1β, TNF-α, TNF-R1, TGF-β receptor type 2, SMAD3, TGF-β, HSP70, MMP13 |

|

| |||

| Apoptosis and survival | (1) Role of IAP-proteins in apoptosis (2) Anti-apoptotic TNFs/NF-kB/Bcl-2 pathway |

Caspase dependent and independent apoptosis; apoptosis and antiapoptosis | TNF-α, TNF-R1, HSP70, caspase3, CD40L, CD40 |

|

| |||

| Transcription | NF-kB signaling pathway | Activate the transcription of target genes | TNF-α, TGF-β, TNF-R1, CD14 |

FDR = 0.01.

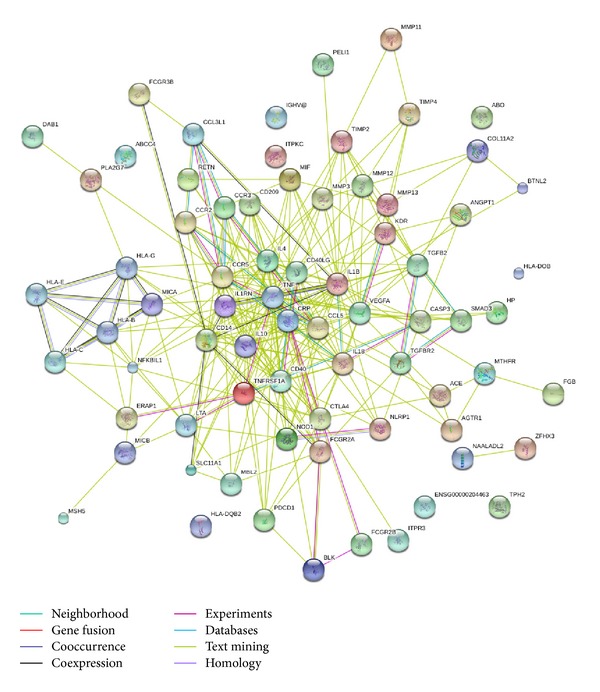

3.4. STRING Analysis

Now specifically, we are interested in finding functional associations among these genes. We broadcast our data to STRING (a database of known and predicted protein interactions), which responds by displaying a network of nodes (proteins) connected by colored edges representing functional relationships.

Figure 2 summarizes the network of predicted associations between proteins encoded by these genes. The results indicate that CASP3, IL18, BLK, FCGR2B, FCGR2A, CRP, CCR5, CCL5, CCR3, CCL3L1, TNFRSF1A, TNF, IL4, ERAP1, LTA, CD40, NOD1, CTLA4, NLRP1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2, VEGFA, KDR, and CCR2 are associated according to experimental evidence, with involvement in many signaling pathways; TNF was the key of nodes, linking to CRP, IL-4, CD40, CD40LG, IL-18, IL-10, and so on. They linked to many immune and inflammatory responses. All of these proteins (encoded by genes) are interrelated, forming a large network. However, many proteins are not linked to others, indicating that their functions are unrelated or unknown.

Figure 2.

STRING analysis of the relationship between genes. The network nodes represent the proteins encoded by the genes. Seven different colored lines link a number of nodes and represent seven types of evidence used in predicting associations. Among these significant genes, VWA7, PRRC2A, and ABHD16A were not identified. A red line indicates the presence of fusion evidence; a green line represents neighborhood evidence; a blue line represents cooccurrence evidence; a purple line represents experimental evidence; a yellow line represents text mining evidence; a light blue line represents database evidence [100, 101] and a black line represents coexpression evidence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Immune Response in the Pathogenesis of KD

KD has long been considered as an abnormal immune disease. The activation of immune system and the cascade release of inflammatory factors are the important features in KD. A large number of T cells (increased activated CD4 T cells, depressed CD8 T cells and CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells), large mononuclear cells, macrophages and plasma cells, with a smaller number of neutrophils, are observed in various organ tissues of fatal cases of acute KD [102–106]. Additionally, various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [107, 108], matrix metalloproteinases, nitric oxide production [109], autoantibody production [110, 111], and adhesive molecule expression [112, 113] are also overactivated in the acute stage of KD which are considered to facilitate vascular endothelial inflammation and then participate in the pathogenesis of KD and CAL formation. Go processes and DAVID analysis revealed that these genes are significantly enriched in immune responses which have the parallel results with clinical and laboratory findings. In addition, these genes are widely involved in other immune systemic and inflammatory diseases, for example, autoimmune thyroid disease, asthma, type I diabetes mellitus, allograft rejection, inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis, arthritis, and rheumatic disease. Furthermore, the signal pathway produced in GeneGo contains many immune response pathways that participate in inflammation, apoptosis, injury, and remodeling process, which have been listed in Table 3.

4.2. ECM-Remodeling and Plasmin Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of KD

In addition to the signal pathway of the immune response, ECM-remodeling and plasmin signaling pathway associated with cell adhesion were enriched in GeneGo MetaCore software (FDR < 0.01, P < 0.005).

Numerous studies suggest that they participated in the pathophysiological process of KD. Activation of the fibrinolytic system, vascular injury, and remodeling were the prominent outcome in these pathways. Activated plasmin in the plasmin signaling pathway which is a major fibrinolytic protease can directly degrade fibrinogen, laminin, and fibronectin [114]. On the cell surface, plasmin can activate a number of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) MMP1, MMP13 [115]. Other MMPs (MMP-9 and so on) were subsequently activated. Moreover, IL-1 β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ can stimulate the endothelial cells to produce more MMP-9. These MMPs degrade extracellular matrix proteins and components of basal membranes leading to the disruption of the internal elastic lamina and the trilaminar structure of the vascular wall [116–118]. Many examinations have showed that many MMPs were highly expressed in the acute stage of KD. MMPs are prominent during the remodeling process, contributing to the formation of coronary artery lesions [119], and consequently the intima proliferates and thickens, while in rare cases the vessel wall becomes stenotic or occluded by either stenosis or thrombosis. Endogenous tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) such as TIMP1, TIMP2, and TIMP3 can reduce excessive proteolytic ECM degradation by MMPs. The balance between MMPs and TIMPs controls the extent of ECM remodeling [120, 121]. One study indicated that MMPs and TIMPs were in a state of imbalance in KD patients [122]. Therefore, ECM-remodeling and plasmin signaling pathway may have played a certain role in the vascular damage in KD.

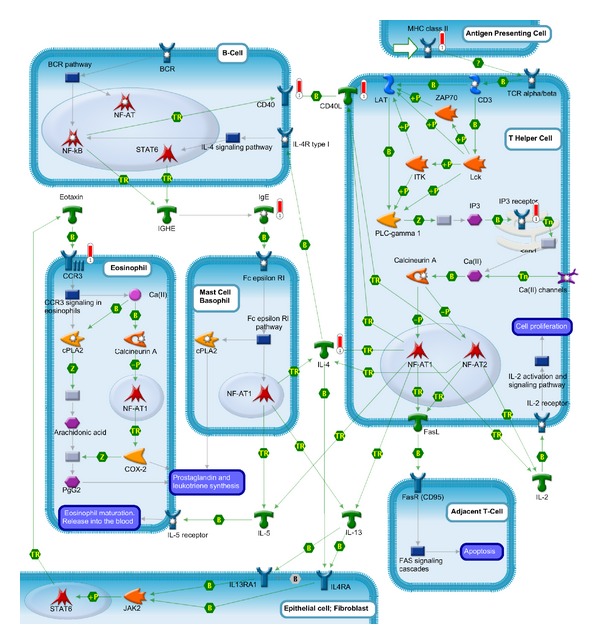

4.3. NF-AT Signaling and Leukocyte Interactions

NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions (P value = 2.28 × 10−5) in the immune response cause our great concern. In this pathway, the activation of NFAT proteins is induced by the engagement of receptors that are coupled to the calcium/calcineurin signals, such as the antigen receptors that are expressed by T cells (TCR) and B cells (BCR), the Fc-epsilon receptors (e.g, Fc epsilon R1) that are expressed by mast cells and basophil cells or receptors coupled to heterotrimeric G-proteins (e.g., CCR3 on eosinophils) [123, 124] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions have been enriched by GeneGo.

The NFAT signal is activated in T cell and can promote the expression of the immune-related genes. Antigen presenting cells present antigenic peptides to the T helper cell via major histocompatibility complex, class (II) (MHC class II). MHC class II can upregulate the expression of CD4+T cells and downregulate the expression of CD8+T cells which has been confirmed in acute phase of KD. Then, MHC class II peptides activate the T-cell receptor (TCR alpha/beta-CD3 complex) that starts a signal leading to the increase in cytosolic Ca(II) through both the transient release of calcium from intracellular stores and the influx of calcium through Ca(II) channels. That leads to activation of the calcium-regulated phosphatase, Calcineurin A. The activated Calcineurin A cleaves an inhibitory phosphate residue from the transcription fator NF-AT (e.g., NF-AT1 and NF-AT2). Consequently, NF-AT is transported into the nucleus, where it cooperates with other transcription factors for promoter binding and thereby induces the expression of cytokines and many other T-cell-activation-induced proteins. NF-AT in T cells is critical for the expression of a number of immunologically important genes, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, as well as several related membrane-bound proteins such as CD40 Ligand (CD40L) and Fas Ligand (Fasl) [125–127].

IL-4 plays an important role in cell-to-cell activation to activate NFAT signal to release leukotrienes and prostaglandins. Activated by NFAT signal in T cell, IL-4 activates nearby B cells that express corresponding receptor, IL-4R. In conjunction with BCR, IL-4 signaling pathway leads to the activation of several transcription factors, including nuclear factor kappa-B(NF-κB), signal transducer, and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), that regulate immunoglobulin class switching and the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) by some B cells [128–130]. IgE in turn activates NF-AT1 translocation and function in mast cells and basophils through the IgE receptor (Fc epsilon R1) leading to production of an array of cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [131, 132]. Fc epsilon R1 pathway also leads to activation of the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (Cpla2) that contributes to the secretion of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, the main mediators of inflammatory response [133]. IL-4 and IL-13, in turn, activate epithelial cells and/or fibroblasts to release eosinophil-activating cytokines, such as chemokine ligand 11 (Eotaxin). These cytokines recruit eosinophils to the inflammatory focus in the tissue and induce intracellular signaling, mainly via chemokine receptor 3 (CCR3) activation, which leads to the leukotrienes and prostaglandins synthesis and also can use NF-AT1 transcription complex to activate cytokines and chemokines. IL-4 plays an important role in the interaction between the leukocytes and induces the release of variety of inflammatory mediators.

Additionally, CD40L activates nearby B cells that express corresponding receptor CD40. IL-2 binds to IL-2 receptors at the T Cells surface to drive clonal expansion of the activated cell that induces autocrine proliferation [124]. Fasl activates the adjacent T Cells via binding to its receptors; FasR (CD95) [134] mediates apoptosis through the FAS signaling cascades (apoptosis). Fas-Fas ligand system has been considered to be involved in inducing apoptosis in KD resulting in marked decrease of peripheral blood lymphocytes [135].

4.3.1. What Is the NFATs?

NFATs are nuclear factors of activated T cells. The NFAT family consists of five members: NFAT1, NFAT2, NFAT3, NFAT4, NFAT4, and NFAT5. Four (except NFAT5) of these proteins are regulated by calcium signaling and four (except NFAT3) are expressed in the immune system [124]. They are initially identified as Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors that regulate gene transcription in response to intracellular Ca2+signals. NFAT family members are expressed by almost every cell type, including the immune system and nonimmune cells, contributed to the regulation of immune response, as well as development and differentiation. In the immune system, NFATs have pivotal roles in the development and function of immune organs and regulate numerous physiological processes. With the best described effects on T cell activation and phenotype, NFATs also regulate gene expression in other immune cells such as B cells [136], mast cells [137, 138], eosinophils [139], basophils [140] and NK cells [141], macrophage [142], and dendritic cells [143]. They can regulate the release of various cytokines in immune cells. In nonimmune cells, they regulate development and differentiation in a variety of organ systems [134]. It has been examined that they control gene expression during remodeling and are activated by growth factors [144, 145] or histamine [146] in the endothelium, contributing to cell growth, remodeling of smooth muscle cells [147–149], and vascular development and angiogenesis [150–152] (including the isoforms c1 and c3) and are activated in response to inflammatory processes [153] and high intravascular pressure [154] in the vascular system. The isoforms NFATc3 and NFATc4 are active during pathophysiological conditions that affect the cardiovascular system, including atrial fibrillation [155, 156] and hypertrophy [157]. Loss of specific NFAT isoforms has been found to result in cardiovascular, skeletal muscle, cartilage, neuronal, or immune system defects [158–162]. Therefore, we can conclude that the Ca2+/NFAT pathway plays a wide range role in inflammatory processes, immune responses, and the remodeling of vascular tissues. All of these physiological processes occur in KD. It is suggested that the Ca2+/NFAT pathway may involve in the pathological processes of KD.

4.3.2. The Upstream Adjustment Signals of NFAT Signal

NFATs are mainly Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors that regulate gene transcription in response to intracellular Ca2+ signals. Four (except NFAT5) of these proteins are regulated by calcium signaling. Activity of NFATs is regulated by phosphorylation. Inactive NFATs are highly phosphorylated and localized in the cytoplasm. Intracellular Ca2+ signals activate the calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase calcineurin (CaN), which dephosphorylates NFATs and induces translocation to the nucleus.

Inositol-trisphosphate 3-kinase C (ITPKC) is a negative regulator of the Ca2+/NFAT pathway. NF-AT signaling was first mentioned to be associated with regulation of ITPKC in the KD. ITPKC is a kinase of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) which is a second messenger molecule that releases calcium from the endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum. First identified by genome-wide study and following confirmation by candidate genetic studies in both Japanese, Taiwanese and US children, ITPKC was considered to be associated with KD which confers both susceptibility to KD and the risk for CAL and IVIG resistance [26, 94, 95, 163], which has been thought to be involved in the Ca2+-dependent NFAT signaling pathways in T cells. It has been considered that C allele of rs28493229 in ITPKC can reduce the splicing efficiency of the ITPKC mRNA, inducing the hyperactivation of Ca2+-dependent NFAT signal in T cells, leading to a reduction in the phosphorylation of IP3 to IP4, resulting in the increase of IP3 levels. This would result in an increase of calcium levels and excessive activation of the NFAT signal, thus leading to immune dysregulation.

Caspase-3 (CASP3) is a key molecule of activation-induced cell death (AICD) [164]; it is profoundly related to the apoptosis of immune cells. It has also been reported to cleave the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, type 1 (ITPR1) in apoptotic T cells (ITPR1 is a receptor for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), a substrate for ITPKC in T cells [165]). Thereby, it is a positive regulatory factor of NFAT signal. Additionally, the mutation of CASP3 (rs113420705) can reduce the binding of NFAT to the DNA surrounding the SNP. Its gene variant (4q34-35, rs113420705) has been identified contributing to KD susceptibility in Euro-American triads and Taiwanese [35, 166]. Other studies [167, 168] also stated that CASP3 plays an important role in the execution phase of apoptosis of immune cells in KD.

Calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., CsA, FK506) have been extensively used as immunosuppressive agents to improve graft survival and to treat autoimmune diseases [127]. They act by blocking calcineurin enzymatic activity. CsA has been an effective [169–171] therapeutic drug in the treatment of IVIG resistance patients in KD.

4.3.3. The Downstream of Adjustment Signals of NFAT Signal: NF-κB (Nuclear Factor Kappa-B)

NF-κB is another transcription factor of eukaryotes, which is evolutionarily related to the NF-AT family of transcription factors. It is activated in response to signals that lead to cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and other events. It takes part in expression of numerous cytokines and adhesion molecules which are critical elements involved in the regulation of immune responses.

NF-κB plays pivotal roles in the immune and inflammatory responses by regulating the interaction between CD40 and CD40L in T cells and B cells. NF-κB can be activated by IL-4 signaling pathway in B cells to induce the expression of CD40 which has been illustrated above. CD40 plays a crucial role as a costimulatory molecule in the cooperation between T and B cells. It is important in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases in humans and animal models such as autoimmune thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, allergic encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, collagen-induced arthritis, and autoimmune type of diabetes mellitus [172–174]. CD40 signaling leads to isotype switching and autoantibody production in B cells and in T-cell priming, altering TCR expression through the expression and nuclear translocation of recombinases, which increases the risk of developing autoimmunity [173]. CD40 engagement in both T or B cells leads to the production of cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-2, TNF-α, IFN-α, and CD80, developing an environment which is conducive to autoimmune diseases [172–174].

Additionally, the interaction between CD40 and CD40L regulated by NF-κB can regulate the expression of numerous biomolecules in other cells. They can enhance the expression of cytokines (such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, lymphotoxin-α, and transforming growth factor-β by B cells; the synthesis of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) by dendritic cells and eosinophils and the synthesis of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells), chemokines (monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-8, MCP-1, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1,-2,-3,-9,-11, and -13) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells, macrophages, endothelial and smooth muscle cells endothelial), adhesion molecules (E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in endothelial cells and fibroblasts), platelet-activating factor [175], prostaglandin E2 [176], vascular endothelial growth factor [177, 178], and NO [172]. which are involved in the pathophysiology of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

NF-κB may participate in the pathogenesis of vasculitis of KD in acute stage. Some studies have indicated that NF-κB is excessively activated in the acute phase of KD and the inhibition of NF-κB can reduce the generation of inflammatory cytokines which plays important roles in vascular damage of KD [179, 180]. NF-κB signaling pathway is a complex system; it perhaps involves in immune damage of KD in different levels. Activation of NF-κB can be used as the trigger of key links of the inflammatory response and induce the cascade release of inflammatory response factor, eventually leading to inflammatory pathological damage.

4.4. The NF-AT Signaling and Leukocyte Interactions and NF-κB Signaling Together May Be Involved in the Pathogenetic Process of KD

Given the important role of NFAT signaling and NF-κB signaling in the activation of immune system and the regulating of vascular remodeling, we speculate that the interaction between NFAT signaling and NF-κB signaling together may also be involved in the pathogenesis of KD.

Initially due to exposure to some inflammatory stimuli or certain pathogens, antigen presenting cells present antigenic peptides to the T-cell receptors via MHC class II leading to the stimulation of PLC-gamma 1 and hydrolyzation of PIP2. The second messengers IP3 in the T cells start a signal leading to the increase in cytosolic Ca(II) through both the transient release of calcium from intracellular stores and influx of calcium through Ca(II) channels. The high calcium levels lead to activation of the calcium-regulated phosphatase, Calcineurin A. The activated Calcineurin A cleaves an inhibitory phosphate residue from the transcription fator NF-AT (e.g., NF-AT1 and NF-AT2). Consequently, NF-AT is transported into the nucleus, where it cooperates with other transcription factors for promoter binding and activates T cells inducing the expression of a number of immunologically important genes including IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, CD40 Ligand (CD40L), and Fas Ligand (Fasl). Through the leukocyte interactions, other immune cells were activated and release other inflammatory cytokines, such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins. In B cells and T-cell, CD40 signaling leads to isotype switching, autoantibody production, and altering TCR expression. CD40 signaling can also enhance the expression of cytokines, chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases, adhesion molecules, platelet-activating factors, prostaglandin E2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and NO. in other cells. The combined effect of these factors causes the vascular damage and formation of coronary artery lesions in KD. The process of NFAT signal in regulating development and differentiation was also excessively induced by the pathological damage of vasculature and then contributed to the remodeling of vascular system.

IL-4, CD40, and CD40L, which are enriched in the pathway of NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions and play a crucial role in the immune response and remodeling process, are located in the center position of the network (analysed by STRING) and are closely linked with the other factors. It further demonstrate the importance of this pathway.

5. Conclusions

KD is a complex disease. Many studies have shown that it is associated with a variety of gene polymorphism. Through GeneGo and DAVID analysis, we speculated that NF-AT signaling and leukocyte interactions combined with another transcription factor NF-κB may play an important role in pathological damage of KD. Their importance needs our follow-up clinical validation.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material was made by the software of DAVID (The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery). It provides a comprehensive set of functional annotation tools for investigators to understand biological meaning behind large list of genes. The Supplementary Material contains the gene ontology analysis and the pathway analysis (KEGG pathway) of my genes which has been presented in Table 1 (candidate genetic studies), Table 2 (genome-wide studies). Gene ontology analysed the gene function from molecular function, biological process, cellular component. KEGG pathway showed the biological pathways and diseases these genes involved in.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (no. BK2010032), Jiangsu province health department (H201127), and Suzhou Science and Technology Bureau (SYS201144). Additionally, the authors would like to thank the Systems Biology Center of Soochow University of China for their technical support.

References

- 1.Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children. Japanese Journal of Allergology. 1967;16(3):178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns JC. Commentary: translation of Dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki’s original report of fifty patients in 1967. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2002;21(11):993–995. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayusawa M, Sonobe T, Uemura S, et al. Revision of diagnostic guidelines for Kawasaki disease (the 5th revised edition) Pediatrics International. 2005;47(2):232–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo HC, Liang CD, Wang CL, Yu HR, Hwang KP, Yang KD. Serum albumin level predicts initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment failure in Kawasaki disease. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99(10):1578–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns JC, Glodé MP. Kawasaki syndrome. The Lancet. 2004;364(9433):533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YC, Hou CP, Kuo CM, Liang CD, Kuo HC. Atypical Kawasaki disease: literature review and clinical nursing. Journal of Nursing. 2010;57(6):104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowley AH, Baker SC, Orenstein JM, Shulman ST. Searching for the cause of Kawasaki disease—cytoplasmic inclusion bodies provide new insight. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6(5):394–401. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura Y, Yashiro N, Uehara R, et al. Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Japan: results of the 2009-2010 nationwide survey. Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;22(3):216–221. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uehara R, Belay ED. Epidemiology of kawasaki disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States. Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;22(2):79–85. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holman RC, Curns AT, Belay ED, et al. Kawasaki syndrome in Hawaii. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2005;24(5):429–433. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160946.05295.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uehara R, Yashiro M, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H. Kawasaki disease in parents and children. Acta Paediatrica. 2003;92(6):694–697. doi: 10.1080/08035320310002768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagawa H, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, et al. Results of the nationwide epidemiologic survey of Kawasaki disease in 1995 and 1996 in Japan. Pediatrics. 1998;102(6, article E65) doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R, et al. Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Japan: results of the 2007-2008 nationwide survey. Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;20(4):302–307. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uehara R, Yashiro M, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H. Parents with a history of Kawasaki disease whose child also had the same disease. Pediatrics International. 2011;53(4):511–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onouchi Y. Molecular genetics of Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2009;65(5, part 2):46R–54R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dba60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onouchi Y. Genetics of Kawasaki disease: what we know and don't know. Circulation Journal. 2012;76(7):1581–1586. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weng KP, Hsieh KS, Ho TY, et al. IL-1B polymorphism in association with initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment failure in Taiwanese children with Kawasaki disease. Circulation Journal. 2010;74(3):544–551. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weng KP, Hsieh KS, Hwang YT, et al. IL-10 polymorphisms are associated with coronary artery lesions in acute stage of Kawasaki disease. Circulation Journal. 2010;74(5):983–989. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng KP, Ho TY, Chiao YH, et al. Cytokine genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to Kawasaki disease in Taiwanese children. Circulation Journal. 2010;74(12):2726–2733. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo HC, Chao MC, Hsu YW, et al. CD40 gene polymorphisms associated with susceptibility and coronary artery lesions of Kawasaki disease in the Taiwanese population. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:5 pages. doi: 10.1100/2012/520865.520865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu HR, Chang WP, Wang L, et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) promoter-336 A/G (rs4804803) polymorphism associated with susceptibility of Kawasaki disease. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:5 pages. doi: 10.1100/2012/634835.634835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R, He B, Gao F, Liu Q, Yi Q. Association of the resistin gene promoter region polymorphism with Kawasaki disease in Chinese children. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/356362.356362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrestha S, Wiener H, Shendre A, et al. Role of activating FcγR gene polymorphisms in Kawasaki disease susceptibility and intravenous immunoglobulin response. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2012;5(3):309–316. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.962464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniuchi S, Masuda M, Teraguchi M, et al. Polymorphism of Fcγ RIIa may affect the efficacy of γ-globulin therapy in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2005;25(4):309–313. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onoyama S, Ihara K, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Genetic susceptibility to Kawasaki disease: analysis of pattern recognition receptor genes. Human Immunology. 2012;73(6):654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin MT, Wang JK, Yeh JI, et al. Clinical implication of the C allele of the ITPKC gene SNP rs28493229 in kawasaki disease: association with disease susceptibility and BCG scar reactivation. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011;30(2):148–152. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f43a4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onouchi Y. Identification of susceptibility genes for Kawasaki disease. Japanese Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2010;33(2):73–80. doi: 10.2177/jsci.33.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng Q, Chen C, Zhang Y, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2290692 in the 3′UTR of ITPKC associated with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease in a Han Chinese population. Pediatric Cardiology. 2012;33(7):1046–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onouchi Y, Suzuki Y, Suzuki H, et al. ITPKC and CASP3 polymorphisms and risks for IVIG unresponsiveness and coronary artery lesion formation in Kawasaki disease. Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2013;13(1):52–59. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu C, Jain S, Hibberd ML, et al. Transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway in patients with Kawasaki disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2011;4(1):16–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.940858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi YM, Shim KS, Yoon KL, et al. Transforming growth factor beta receptor II polymorphisms are associated with Kawasaki disease. Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;55(1):18–23. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2012.55.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamura K, Ihara K, Ikeda K, Nagata H, Mizuno Y, Hara T. Histo-blood group gene polymorphisms as potential genetic modifiers of the development of coronary artery lesions in patients with Kawasaki disease. International Journal of Immunogenetics. 2012;39(2):119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2011.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JJ, Hong YM, Yun SW, et al. Assessment of risk factors for Korean children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Cardiology. 2012;33(4):513–520. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo H-C, Onouchi Y, Hsu Y-W, et al. Polymorphisms of transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway and Kawasaki disease in the Taiwanese population. Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;56(12):840–845. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo HC, Yu HR, Juo SHH, et al. CASP3 gene single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs72689236) and Kawasaki disease in Taiwanese children. Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;56(2):161–165. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breunis WB, Davila S, Shimizu C, et al. Disruption of vascular homeostasis in patients with Kawasaki disease: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;64(1):306–315. doi: 10.1002/art.33316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breunis WB, Biezeveld MH, Geissler J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene haplotypes in Kawasaki disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(5):1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/art.21811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsueh KC, Lin YJ, Chang JS, et al. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor C-634 G polymorphism in Taiwanese children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Cardiology. 2008;29(2):292–296. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kariyazono H, Ohno T, Khajoee V, et al. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor gene polymorphisms with coronary artery lesions of Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2004;56(6):953–959. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000145280.26284.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh YY, Chang CC, Hsu CM, Chen SY, Lin WH, Tsai FJ. Major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related gene polymorphisms: associated with susceptibility to kawasaki disease and coronary artery aneurysms. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2011;15(11):755–763. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang FY, Lee YJ, Chen MR, et al. Polymorphism of transmembrane region of MICA gene and Kawasaki disease. Experimental and Clinical Immunogenetics. 2000;17(3):130–137. doi: 10.1159/000019132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsieh YY, Lin YJ, Chang CC, et al. Human lymphocyte antigen B-associated transcript 2, 3, and 5 polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with susceptibility of Kawasaki disease and coronary artery aneurysm. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2010;24(4):262–268. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha S, Wiener HW, Olson AK, et al. Functional FCGR2B gene variants influence intravenous immunoglobulin response in patients with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(3):677.e1–680.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsueh KC, Lin YJ, Chang JS, et al. Association of interleukin-10 A-592C polymorphism in Taiwanese children with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2009;24(3):438–442. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.3.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsieh KS, Lai TJ, Hwang YT, et al. IL-10 promoter genetic polymorphisms and risk of Kawasaki disease in Taiwan. Disease Markers. 2011;30(1):51–59. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J, Li CR, Li YB, et al. The correlation between Kawasaki disease and polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-10 gene promoter. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2003;41(8):598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin HS, Kim HB, Kim BS, et al. The IL-10 (-627 A/C) promoter polymorphism may be associated with coronary aneurysms and low serum albumin in Korean children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2007;61(5):584–587. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180459fb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaudhuri K, Singh Ahluwalia T, Singh S, Binepal G, Khullar M. Polymorphism in the promoter of the CCL5 gene (CCL5 G-403A) in a cohort of North Indian children with Kawasaki disease. A preliminary study. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2011;29(1, supplement 64):S126–S130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang GB, Li CR, Yang J, Wen PQ, Jia SL. A regulatory polymorphism in promoter region of TNFR1 gene is associated with Kawasaki disease in Chinese individuals. Human Immunology. 2011;72(5):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuo HC, Liang CD, Yu HR, et al. CTLA-4, position 49 A/G polymorphism associated with coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2011;31(2):240–244. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park JA, Shin KS, Youn WK. Polymorphism of matrix metalloproteinase-3 promoter gene as a risk factor for coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2005;20(4):607–611. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.4.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimizu C, Matsubara T, Onouchi Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase haplotypes associated with coronary artery aneurysm formation in patients with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;55(12):779–784. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao J, Wang HY, Wu NJ, Zhang SH. Relationship between fibrinogen Bβ-148C/T polymorphism and coronary artery lesions in children with Kawasaki disease. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2010;12(7):518–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burns JC, Shimizu C, Gonzalez E, et al. Genetic variations in the receptor-ligand pair CCR5 and CCL3L1 are important determinants of susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;192(2):344–349. doi: 10.1086/430953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mamtani M, Matsubara T, Shimizu C, et al. Association of CCR2-CCR5 haplotypes and CCL3L7 copy number with kawasaki disease, coronary artery lesions, and IVIG responses in Japanese children. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011458.e11458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breunis WB, Biezeveld MH, Geissler J, et al. Polymorphisms in chemokine receptor genes and susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;150(1):83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jhang WK, Kang MJ, Jin HS, et al. The CCR5 (-2135C/T) polymorphism may be associated with the development of kawasaki disease in Korean children. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2009;29(1):22–28. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang YC, Lin YJ, Chang JS, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism rs2229634 in the ITPR3 gene is associated with the risk of developing coronary artery aneurysm in children with Kawasaki disease. International Journal of Immunogenetics. 2010;37(6):439–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2010.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheu JJ, Lin YJ, Chang JS, et al. Association of COL11A2 polymorphism with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease and development of coronary artery lesions. International Journal of Immunogenetics. 2010;37(6):487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2010.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang J, Li CR, Li YB, Huang HJ, Li RX, Wang GB. Correlation between mannose-binding lectin gene codon 54 polymorphism and susceptibility of Kawasaki disease. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2004;42(3):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sato S, Kawashima H, Kashiwagi Y, Fujioka T, Takekuma K, Hoshika A. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms with Kawasaki disease in the Japanese. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;12(4):307–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biezeveld MH, Kuipers IM, Geissler J, et al. Association of mannose-binding lectin genotype with cardiovascular abnormalities in Kawasaki disease. The Lancet. 2003;361(9365):1268–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Biezeveld MH, Geissler J, Weverling GJ, et al. Polymorphisms in the mannose-binding lectin gene as determinants of age-defined risk of coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(1):369–376. doi: 10.1002/art.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheung YF, Ho MHK, Ip WK, Fok SFS, Yung TC, Lau YL. Modulating effects of mannose binding lectin genotype on arterial stiffness in children after Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2004;56(4):591–596. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000139406.22305.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ban JY, Kim SK, Kang SW, Yoon KL, Chung JH. Association between polymorphisms of matrix metalloproteinase 11 (MMP-11) and Kawasaki disease in the Korean population. Life Sciences. 2010;86(19-20):756–759. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simonini G, Corinaldesi E, Massai C, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor-173 polymorphism and risk of coronary alterations in children with Kawasaki disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2009;27(6):1026–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsueh KC, Lin YJ, Chang JS, Wan L, Tsai FJ. BTNL2 gene polymorphisms may be associated with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease and formation of coronary artery lesions in Taiwanese children. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;169(6):713–719. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park SW, Ban JY, Yoon KL, et al. Involvement of tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) gene polymorphisms in susceptibility to coronary artery lesions in Korean children with Kawasaki disease. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;169(4):457–461. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chun JK, Kang DW, Yoo BW, Shin JS, Kim DS. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) gene polymorphisms lodged in the genetic predispositions of Kawasaki disease. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;169(2):181–185. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsueh KC, Lin YJ, Chang JS, et al. Influence of interleukin 18 promoter polymorphisms in susceptibility to Kawasaki disease in Taiwan. Journal of Rheumatology. 2008;35(7):1408–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen SY, Wan L, Huang YC, et al. Interleukin-18 gene 105A/C genetic polymorphism is associated with the susceptibility of Kawasaki disease. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2009;23(2):71–76. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin YJ, Wan L, Wu JY, et al. HLA-E gene polymorphism associated with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease and formation of coronary artery aneurysms. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(2):604–610. doi: 10.1002/art.24261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ban JY, Yoon KL, Kim SK, Kang S, Chung JH. Promoter polymorphism (rs3755724, -55C/T) of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4 (TIMP4) as a risk factor for Kawasaki disease with coronary artery lesions in a Korean population. Pediatric Cardiology. 2009;30(3):331–335. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim JJ, Hong SJ, Hong YM, et al. Genetic variants in the HLA-G region are associated with Kawasaki disease. Human Immunology. 2008;69(12):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheung YF, Huang GY, Chen SB, et al. Inflammatory gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to kawasaki disease and its arterial sequelae. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e608–e614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Quasney MW, Bronstein DE, Cantor RM, et al. Increased frequency of alleles associated with elevated tumor necrosis factor-α levels in children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2001;49(5):686–690. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ikeda K, Ihara K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Genetic analysis of MMP gene polymorphisms in patients with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2008;63(2):182–185. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815ef224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oh JH, Han JW, Lee SJ, et al. Polymorphisms of human leukocyte antigen genes in Korean children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Cardiology. 2008;29(2):402–408. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Furuno K, Takada H, Yamamoto K, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 and coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151(2):155.e1–160.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu SF, Chang JS, Peng CT, Shi YR, Tsai FJ. Polymorphism of angiotensin-1 converting enzyme gene and Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Cardiology. 2004;25(5):529–533. doi: 10.1007/s00246-003-0662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoon HS, Hae SK, Sohn S, Young MH. Insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme gene in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2006;21(2):208–211. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukazawa R, Sonobe T, Hamamoto K, et al. Possible synergic effect of angiotensin-I converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism and angiotensin-II type-1 receptor 1166A/C gene polymorphism on ischemic heart disease in patients with Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Research. 2004;56(4):597–601. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000139426.16381.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takeuchi K, Yamamoto K, Kataoka S, et al. High incidence of angiotensin I converting enzyme genotype II its Kawasaki disease patients with coronary aneurysm. European Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;156(4):266–268. doi: 10.1007/s004310050597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minami T, Suzuki H, Takeuchi T, Uemura S, Sugatani J, Yoshikawa N. A polymorphism in plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase is involved in resistance to immunoglobulin treatment in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2005;147(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu SF, Chang JS, Wan L, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ. Association of IL-1Ra gene polymorphism, but no association of IL-1β and IL-4 gene polymorphisms, with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2005;19(3):99–102. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burns JC, Shimizu C, Shike H, et al. Family-based association analysis implicates IL-4 in susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Genes and Immunity. 2005;6(5):438–444. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Onouchi Y, Onoue S, Tamari M, et al. CD40 ligand gene and Kawasaki disease. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;12(12):1062–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nishimura S, Zaitsu M, Hara M, et al. A polymorphism in the promoter of the CD14 gene (CD14/-159) is associated with the development of coronary artery lesions in patients with kawasaki disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;143(3):357–362. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ouchi K, Suzuki Y, Shirakawa T, Kishi F. Polymorphism of SLC11A1 (formerly NRAMP1) gene confers susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;187(2):326–329. doi: 10.1086/345878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsukahara H, Hiraoka M, Saito M, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics International. 2000;42(3):236–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khor CC, Davila S, Breunis WB, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies FCGR2A as a susceptibility locus for Kawasaki disease. Nature Genetics. 2011;43(12):1241–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Onouchi Y, Ozaki K, Burns JC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three new risk loci for Kawasaki disease. Nature Genetics. 2012;44(5):517–521. doi: 10.1038/ng.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee YC, Kuo HC, Chang JS, et al. Two new susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease identified through genome-wide association analysis. Nature Genetics. 2012;44(5):522–525. doi: 10.1038/ng.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Onouchi Y, Tamari M, Takahashi A, et al. A genomewide linkage analysis of Kawasaki disease: evidence for linkage to chromosome 12. Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;52(2):179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Onouchi Y, Gunji T, Burns JC, et al. ITPKC functional polymorphism associated with Kawasaki disease susceptibility and formation of coronary artery aneurysms. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(1):35–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Burgner D, Davila S, Breunis WB, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel and functionally related susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000319.e1000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim JJ, Hong YM, Sohn S, et al. A genome-wide association analysis reveals 1p31 and 2p13.3 as susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease. Human Genetics. 2011;129(5):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsai FJ, Lee YC, Chang JS, et al. Identification of novel susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease in a han Chinese population by a genome-wide association study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016853.e16853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khor CC, Davila S, Shimizu C, et al. Genome-wide linkage and association mapping identify susceptibility alleles in ABCC4 for Kawasaki disease. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2011;48(7):467–472. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.086611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choi IH, Chwae YJ, Shim WS, et al. Clonal expansion of CD8+ T Cells in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159(1):481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Furuno K, Yuge T, Kusuhara K, et al. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in patients with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145(3):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fujiwara H, Hamashima Y. Pathology of the heart in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 1978;61(1):100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Amano S, Hazama F, Kubagawa H. General pathology of Kawasaki disease. On the morphological alterations corresponding to the clinical manifestations. Acta Pathologica Japonica. 1980;30(5):681–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brown TJ, Crawford SE, Cornwall ML, Garcia F, Shulman ST, Rowley AH. CD8 T lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrate coronary artery aneurysms in acute Kawasaki disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;184(7):940–943. doi: 10.1086/323155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rowley AH, Shulman ST, Mask CA, et al. IgA plasma cell infiltration of proximal respiratory tract, pancreas, kidney, and coronary artery in acute Kawasaki disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;182(4):1183–1191. doi: 10.1086/315832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Galeotti C, Bayry J, Kone-Paut I, Kaveri SV. Kawasaki disease: aetiopathogenesis and therapeutic utility of intravenous immunoglobulin. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2010;9(6):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kimura J, Takada H, Nomura A, et al. Th1 and Th2 cytokine production is suppressed at the level of transcriptional regulation in Kawasaki disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2004;137(2):444–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kuo HC, Wang CL, Liang CD, et al. Association of lower eosinophil-related T helper 2 (Th2) cytokines with coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2009;20(3):266–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang CL, Wu YT, Lee CJ, Liu HC, Huang LT, Yang KD. Decreased nitric oxide production after intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in patients with Kawasaki disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2002;141(4):560–565. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.127505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fujieda M, Karasawa R, Takasugi H, et al. A novel anti-peroxiredoxin autoantibody in patients with Kawasaki disease. Microbiology and Immunology. 2012;56(1):56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chun JK, Lee TJ, Choi KM, Lee KH, Kim DS. Elevated anti-α-enolase antibody levels in Kawasaki disease. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2008;37(1):48–52. doi: 10.1080/03009740701607075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kobayashi T, Kimura H, Okada Y, et al. Increased CD11b expression on polymorphonuclear leucocytes and cytokine profiles in patients with Kawasaki disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;148(1):112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mitani Y, Sawada H, Hayakawa H, et al. Elevated levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and serum amyloid-A late after Kawasaki disease: association between inflammation and late coronary sequelae in Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2005;111(1):38–43. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151311.38708.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bonnefoy A, Legrand C. Proteolysis of subendothelial adhesive glycoproteins (fibronectin, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor) by plasmin, leukocyte cathepsin G, and elastase. Thrombosis Research. 2000;98(4):323–332. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morgan H, Hill PA. Human breast cancer cell-mediated bone collagen degradation requires plasminogen activation and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Cancer Cell International. 2005;5(article 1) doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Imai K, Shikata H, Okada Y. Degradation of vitronectin by matrix metalloproteinases-1, -2, -3, -7 and -9. FEBS Letters. 1995;369(2-3):249–251. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00752-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shapiro SD. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of extracellular matrix: biological consequences. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1998;10(5):602–608. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Netzel-Arnett S, Mitola DJ, Yamada SS, et al. Collagen dissolution by keratinocytes requires cell surface plasminogen activation and matrix metalloproteinase activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(47):45154–45161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sakata K, Hamaoka K, Ozawa S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in vascular lesions and endothelial regulation in Kawasaki disease. Circulation Journal. 2010;74(8):1670–1675. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Verstappen J, von den Hoff JW. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): their biological functions and involvement in oral disease. Journal of Dental Research. 2006;85(12):1075–1084. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hannas AR, Pereira JC, Granjeiro JM, Tjäderhane L. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in the oral environment. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2007;65(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00016350600963640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Senzaki H, Masutani S, Kobayashi J, et al. Circulating matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in patients with Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2001;104(8):860–863. doi: 10.1161/hc3301.095286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Serfling E, Berberich-Siebelt F, Avots A, et al. NFAT and NF-κB factors-the distant relatives. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2004;36(7):1166–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2005;5(6):472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: form and function. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80(4):1483–1521. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Macián F, López-Rodríguez C, Rao A. Partners in transcription: NFAT and AP-1. Oncogene. 2001;20(19):2476–2489. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lee M, Park J. Regulation of NFAT activation: a potential therapeutic target for immunosuppression. Molecules and Cells. 2006;22(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Benekli M, Baer MR, Baumann H, Wetzler M. Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins in leukemias. Blood. 2003;101(8):2940–2954. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Silver K, Cornall RJ. Isotype control of B cell signaling. Science’s STKE. 2003;2003(184, article pe21) doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.184.pe21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mizuno T, Rothstein TL. B cell receptor (BCR) cross-talk: CD40 engagement enhances BCR-induced ERK activation. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(6):3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kawakami T, Galli SJ. Regulation of mast-cell and basophil function and survival by IgE. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(10):773–786. doi: 10.1038/nri914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lorentz A, Klopp I, Gebhardt T, Manns MP, Bischoff SC. Role of activator protein 1, nuclear factor-κB, and nuclear factor of activated T cells in IgE receptor-mediated cytokine expression in mature human mast cells. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2003;111(5):1062–1068. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Leslie CC. Regulation of the specific release of arachidonic acid by cytosolic phospholipase A2. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2004;70(4):373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(2):S67–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kim HY, Lee HG, Kim DS. Apoptosis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Kawasaki disease. Journal of Rheumatology. 2000;27(3):801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Winslow MM, Gallo EM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR. The calcineurin phosphatase complex modulates immunogenic B cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Monticelli S, Solymar DC, Rao A. Role of NFAT proteins in IL13 gene transcription in mast cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(35):36210–36218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ullerås E, Karlberg M, Westerberg CM, et al. NFAT but not NF-κB is critical for transcriptional induction of the prosurvival gene A1 after IgE receptor activation in mast cells. Blood. 2008;111(6):3081–3089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Seminario MC, Guo J, Bochner BS, Beck LA, Georas SN. Human eosinophils constitutively express nuclear factor of activated T cells p and c. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;107(1):143–152. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Schroeder JT, Miura K, Kim HH, Sin A, Cianferoni A, Casolaro V. Selective expression of nuclear factor of activated T cells 2/c1 in human basophils: evidence for involvement in IgE-mediated IL-4 generation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109(3):507–513. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Aramburu J, Azzoni L, Rao A, Perussia B. Activation and expression of the nuclear factors of activated T cells, NFATp and NFATc, in human natural killer cells: regulation upon CD16 ligand binding. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;182(3):801–810. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yarilina A, Xu K, Chen J, Ivashkiv LB. TNF activates calcium-nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)c1 signaling pathways in human macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(4):1573–1578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Capuano G, et al. CD14 regulates the dendritic cell life cycle after LPS exposure through NFAT activation. Nature. 2009;460(7252):264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature08118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hofer E, Schweighofer B. Signal transduction induced in endothelial cells by growth factor receptors involved in angiogenesis. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2007;97(3):355–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hadri L, Pavoine C, Lipskaia L, Yacoubi S, Lompré AM. Transcription of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase type 3 gene, ATP2A3, is regulated by the calcineurin/NFAT pathway in endothelial cells. Biochemical Journal. 2006;394(1):27–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Boss V, Wang X, Koppelman LF, Xu K, Murphy TJ. Histamine induces nuclear factor of activated T cell-mediated transcription and cyclosporin A-sensitive interleukin-8 mRNA expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54(2):264–272. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wamhoff BR, Bowles DK, Owens GK. Excitation-transcription coupling in arterial smooth muscle. Circulation Research. 2006;98(7):868–878. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216596.73005.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boss V, Abbott KL, Wang XF, Pavlath GK, Murphy TJ. The cyclosporin A-sensitive nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) proteins are expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. Differential localization of NFAT isoforms and induction of NFAT-mediated transcription by phospholipase C-coupled cell surface receptors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(31):19664–19671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.de Frutos S, Spangler R, Alò D, González Bosc LV. NFATc3 mediates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling with α-actin up-regulation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(20):15081–15089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702679200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Graef IA, Chen F, Crabtree GR. NFAT signaling in vertebrate development. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2001;11(5):505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Schulz RA, Yutzey KE. Calcineurin signaling and NFAT activation in cardiovascular and skeletal muscle development. Developmental Biology. 2004;266(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Horsley V, Pavlath GK. NFAT: ubiquitous regulator of cell differentiation and adaptation. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;156(5):771–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Bochkov VN, Mechtcheriakova D, Lucerna M, et al. Oxidized phospholipids stimulate tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells via activation of ERK/EGR-1 and Ca++/NFAT. Blood. 2002;99(1):199–206. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]