Abstract

Responses of Ulva prolifera and Ulva linza to Cd2+ stress were studied. We found that the relative growth rate (RGR), Fv/Fm, and actual photochemical efficiency of PSII (Yield) of two Ulvaspecies were decreased under Cd2+ treatments, and these reductions were greater in U. prolifera than in U. linza. U. prolifera accumulated more cadmium than U. linza under Cd2+ stress. While U. linza showed positive osmotic adjustment ability (OAA) at a wider Cd2+ range than U. prolifera. U. linza had greater contents of N, P, Na+, K+, and amino acids than U. prolifera. A range of parameters (concentrations of cadmium, Ca2+, N, P, K+, Cl−, free amino acids (FAAs), proline, organic acids and soluble protein, Fv/Fm, Yield, OAA, and K+/Na+) could be used to evaluate cadmium resistance in Ulva by correlation analysis. In accordance with the order of the absolute values of correlation coefficient, contents of Cd2+ and K+, Yield, proline content, Fv/Fm, FAA content, and OAA value of Ulva were more highly related to their adaptation to Cd2+ than the other eight indices. Thus, U. linza has a better adaptation to Cd2+ than U. prolifera, which was due mainly to higher nutrient content and stronger OAA and photosynthesis in U. linza.

1. Introduction

Heavy metal contamination is an environmental problem in the margin sea [1]. As the economy in Asian countries continues to grow, the release of heavy metals and other contaminants has increased noticeably [2, 3]. Due to their acute toxicity, cadmium (Cd), lead, and mercury are among the most hazardous metals to the environment and living things [4].

Cd, an oxophilic and sulfophilic element, forms complexes with various organic particles and thereby triggers a wide range of reactions that collectively put the aquatic ecosystems at risk. Cadmium also poses a serious threat to human health due to its accumulation in the food chain [5, 6]. It has been classified as group (I) a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [7]. Cadmium toxicity may be characterized by a variety of syndromes and effects, including renal dysfunction, hypertension, hepatic injury, lung damage, and teratogenic effects [8]. To remove Cd pollutants, various treatment technologies, such as precipitation, ion exchange, adsorption, and biosorption, have been employed [9]. Biosorption is one of the promising techniques for removal of heavy metals. Biosorption utilizes the ability of biological materials to accumulate heavy metals from waste streams by either metabolically mediated or purely physicochemical pathways of uptake [10]. Among the biological materials investigated for heavy metal removal, marine macroalgae have high uptake capacities for a number of heavy metal ions [11, 12].

Green algae species of Ulvaceae, especially the members of the green algal genus Ulva, have been considered as monitors of heavy metals in estuaries [13–15]. Numerous studies have shown that green macroalgae such as Ulva lactuca are able to absorb Cd. These studies mainly focused on metabolism-independent Cd accumulation [6], synthetic surfactants exerting impact on uptake of Cd [12], effect of pH, contact time, biomass dosage and temperature on the Cd uptake kinetics [2], and induced oxidative stress by Cd [7]. However, little information is available regarding physiological responses of different Ulva species to increased Cd2+ concentrations.

In this study, Ulva prolifera and Ulva linza were studied for their responses to different Cd2+ concentrations. Their growth, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, osmotic adjustment ability, and accumulation of inorganic ions and organic solutes were investigated in indoor seawater culture systems. The specific objective of this study was to determine if there was species variation in Cd2+ adaptation, and what were the major physiological parameters involved in the adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Seaweed Collection, Cultivation, and Cd2+ Treatment

Green algae were collected from the sea in Dafeng (Ulva prolifera) and Lianyungang (Ulva linza), Jiangsu province, China. Upon arrival in the laboratory, the seaweeds were washed with distilled water and then cultured in 250 mL flasks containing 200 mL of sterilized artificial seawater (33.33 psu, pH 8.0) enriched with VSE medium [16] for 5 d. The composition of artificial seawater was (g L−1) HCO3 − 0.25, SO4 2− 3.84, Cl− 17.45, Ca2+ 0.76, Mg2+ 1.00, K+ 0.57, and Na+ 9.46. The composition of VSE nutrient solution was (mg L−1) NaNO3 42.50, Na2HPO4·12H2O 10.75, FeSO4·7H2O 0.28, MnCl2·4H2O 0.02, Na2EDTA·2H2O 3.72, vitamin B1 0.20, Biotin 0.001, and vitamin B12 0.001. After 5 d acclimation, healthy samples (0.5 g fresh weight) were cultured in 250 mL flasks with 200 mL medium as described earlier. CdCl2 was added to each flask at the following concentrations: 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, or 120 μmol L−1. After 7 d treatment, U. prolifera and U. linza were harvested and analyzed for selected parameters as described later. All experiments were performed in three replicates. During the preculture and the treatment, seaweeds were grown in a GXZ intelligent light incubator at temperature of 20 ± 1°C, light intensity of 50 μmol m−2 s−1, and photoperiod of 12/12 h. The culture medium was altered every other day.

2.2. Measurement of Relative Growth Rate (RGR)

Fresh weight was determined by weighing the algae after blotting by absorbent paper. RGR was calculated according to the formula RGR (% d−1) = [ln(M t/M 0)/t] × 100%, where M 0 and M t are the fresh weights (g) at days 0 and 7, respectively [17].

2.3. Measurement of Osmotic Adjustment Ability (OAA)

Saturated osmotic potential was measured by the freezing-point depression principle. Seaweeds were placed in double-distilled water for 8 h and then rinsed 5 times with double-distilled water. After blotting dry with absorbent paper, seaweeds were dipped into liquid nitrogen for 20 min. The frozen seaweeds were thawed in a syringe for 50 min, and the seaweed sap was then collected by pressing the seaweed in the syringe [18]. The π 100 was measured by using a fully automatic freezing-point osmometer (8P, Shanghai, China). OAA was calculated by the following equation:

| (1) |

whereby π 100 μ was the π 100 of control seaweeds, and π 100 s was the π 100 of Cd2+-stressed seaweeds.

2.4. Measurements of Chlorophyll (Chl) and Carotenoid (Car) Contents

Determination of Chl and Car was carried out by the method of Häder et al. [19]. Weighed 0.1 g fresh seaweeds were cut with scissors and extracted with 95% (v/v) ethanol (10 mL) in the dark for 24 h. The absorbance of pigment extract was measured at wavelengths of 470, 649, and 665 nm with a spectrophotometer. From the measured absorbance, concentrations of Chl a, Chl b, and Car were calculated on a weight basis.

2.5. Determination of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

A PHYTO-PAM Phytoplankton Analyzer (PAM 2003, Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) was used to determine in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence from chlorophyll in photosystem II (PSII) using different experimental protocols [19]. Before determination, samples were adapted for 15 min in the total darkness to complete reoxidation of PSII electron acceptor molecules. The maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) and the actual photochemical efficiency of PSII in the light (Yield) were then determined.

2.6. Measurement of Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorous (P) Concentrations

Dried samples were ground in a mortar and pestle. Total N in seaweed tissue was analyzed by an N gas analyzer using an induction furnace and thermal conductivity. Total P in seaweed tissue was quantitatively determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES, Optima 2100 DV, PerkinElmer, USA) following nitric acid/hydrogen peroxide microwave digestion. The total amounts of N and P in the seaweed tissue were calculated by multiplying N and P contents in tissue as a proportion of dry weight by the total dry weight of the sample [20].

2.7. Measurement of Inorganic Elements

After 7 d, seaweeds were harvested, washed, and oven-dried at 65°C for 3 d. A 50 mg sample was ashed in a muffle furnace. The ash was dissolved in 8 mL of HNO3 : HClO4 (3 : 1, v : v) and diluted to 50 mL with distilled water. The contents of Cd, Na, K, Ca, and Mg were determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES, Optima 2100 DV, PerkinElmer, USA) [21]. To determine Cl content, the ash was dissolved in 100 mL distilled water and analyzed by potentiometric titration with silver nitrate (AgNO3) [18]. Total nitrate was measured as described previously [22] with nitrate extracted from the tissue by boiling fresh seaweeds (20 mg) in distilled water (400 μL) for 20 min. The nitrate concentrations in the samples were measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm.

2.8. Measurement of Organic Solutes

Soluble sugars (SS) determination was carried out by the anthrone method [23]. Water extract of fresh seaweeds was added to 0.5 mL of 0.1 mol L−1 anthrone-ethyl acetate and 5 mL H2SO4. The mixture was heated at 100°C for 1 min, and its absorbance at 620 nm was read after cooling to room temperature. A calibration curve with sucrose was used as a standard. Soluble proteins (SPs) were measured by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining [24]. Fresh seaweeds (0.5 g) were homogenized in 1 mL phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 5,000 g for 10 min. An aliquot of 0.5 mL of freshly prepared trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added and mixture centrifuged at 8.000 g for 15 min. The pellets were dissolved in 1 mL of 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH, and 5 mL of Bradford reagent was added. Absorbance was recorded at 595 nm using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Free amino acids (FAAs) were extracted and determined following the method of Zhou and Yu [23]. A total of 0.5 g fresh tissue was homogenized in 5 mL 10% (w/v) acetic acid, extracts were supplemented with 1 mL distilled water and 3 mL ninhydrin reagent, then boiled for 15 min and fast cooled, and the volume was made up to 5 mL with 60% (v/v) ethanol. Absorbance was read at 570 nm. The content of total free amino acids was calculated from a standard curve prepared using leucine. Proline (PRO) concentration was determined spectrophotometrically by adopting the ninhydrin method of Irigoyen et al. [25]. We first homogenized 300 mg fresh leaf samples in sulphosalicylic acid. To the extract, 2 mL each of ninhydrin and glacial acetic acid were added. The samples were heated at 100°C. The mixture was extracted with toluene, and the free toluene was quantified spectrophotometrically at 528 nm using L-proline as a standard. Organic acids (OAs) were extracted with boiling distilled water. The concentration of total OA was determined by 0.01 mmol L−1 NaOH titration method, with phenolphthalein as indicator [26].

2.9. Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed in three replicates. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Significant differences between means were determined by Duncan's multiple range test. Unless otherwise stated, differences were considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis on two-way variance analysis (ANOVA), and correlation coefficient was performed using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Cadmium Stress on RGR and OAA of U. prolifera and U. linza

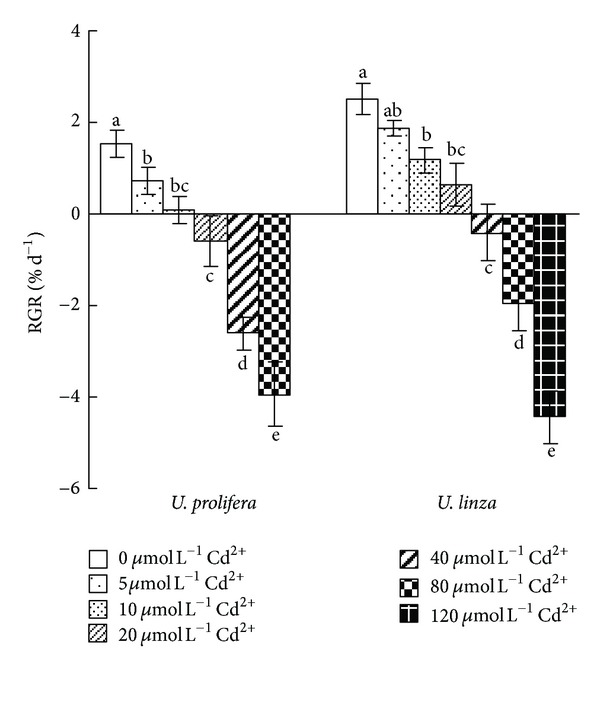

Compared to the control, treatments with 5 μmol L−1 Cd2+ for 7 d did not change RGR of U. linza, but significantly decreased RGR of U. prolifera. The RGR of both Ulva species was significantly decreased as Cd2+ concentration increased. After 7 d exposure to 10, 20, 40, 80; or 120 μmol L−1 Cd2+, RGR of U. linza decreased by 53, 75, 116, 177, and 277%, respectively; U. prolifera decreased by 93, 139, 271, and 357%, respectively. U. prolifera died at 120 μmol L−1 Cd2+ on day 7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 120 μmol L−1) on relative growth rate (RGR) in U. prolifera and U. linza.

The OAA of both species was enhanced by low Cd2+ concentration treatments. The enhancement occurred at 5 and 10 μmol L−1 for U. prolifera and 5, 10 and 20 μmol L−1 for U. linza (Figure 2). However, OAA was negative when U. prolifera was treated by 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, and U. linza treated by 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on osmotic adjustment ability (OAA) of U. prolifera and U. linza.

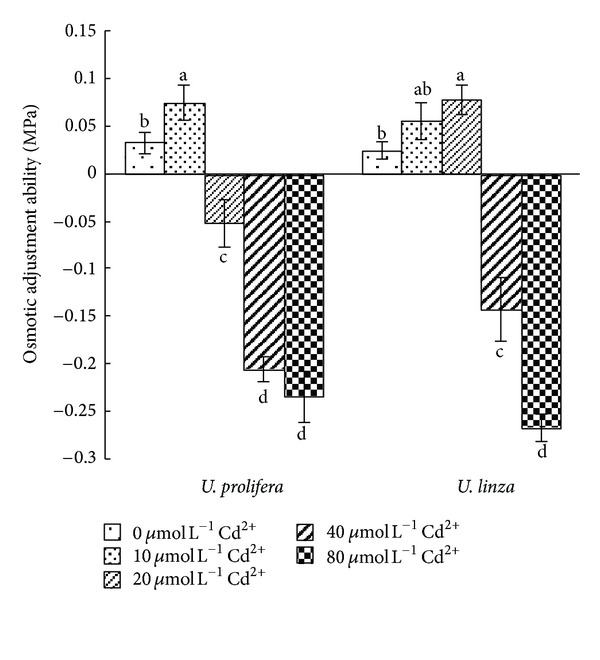

3.2. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Cadmium Content in U. prolifera and U. linza

Cadmium contents in U. prolifera and U. linza increased as Cd2+ concentrations increased (Figure 3). At 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1Cd2+, Cd contents in U. prolifera was 32, 78, 114, 140, and 165 times of the Cd2+ = 0 treatment, respectively, and 10, 26, 44, 65, and 79 times of its control treatment in U. linza, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on cadmium concentration of U. prolifera and U. linza.

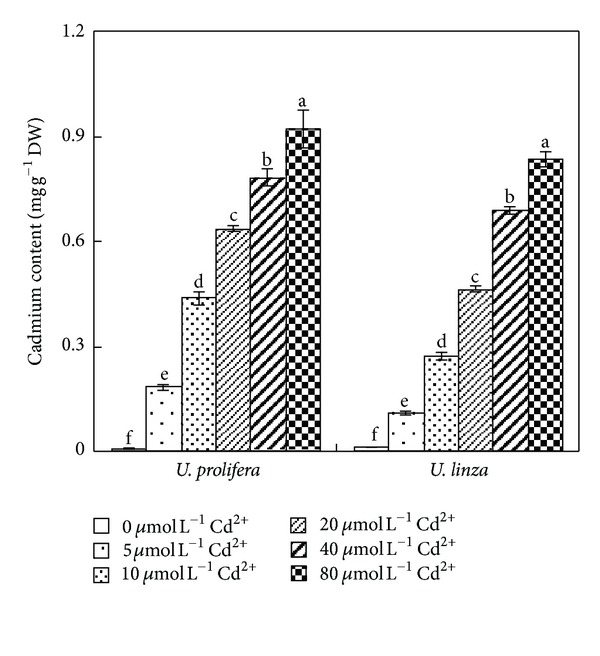

3.3. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Chl and Car Contents in U. prolifera and U. linza

Both Chl and Car contents decreased with the increased Cd2+ concentration. There was no significant change in Chl and Car when both species were treated by 5 and 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ for 7 d. However, significant declines in Chl and Car contents were observed when they were exposed to 20, 40, or 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+. Compared to the control treatment, Chl contents decreased by 18, 25, and 45% at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ in U. prolifera, respectively; and the decreases were 16, 20, and 39% in U. linza, respectively (Figure 4(a)). The Car content declined by 16, 29 and 54% at 20, 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ in U. prolifera, respectively; and by 13, 16, and 44% in U. linza, respectively (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on chlorophyll content (a) and carotenoid content (b) in U. prolifera and U. linza.

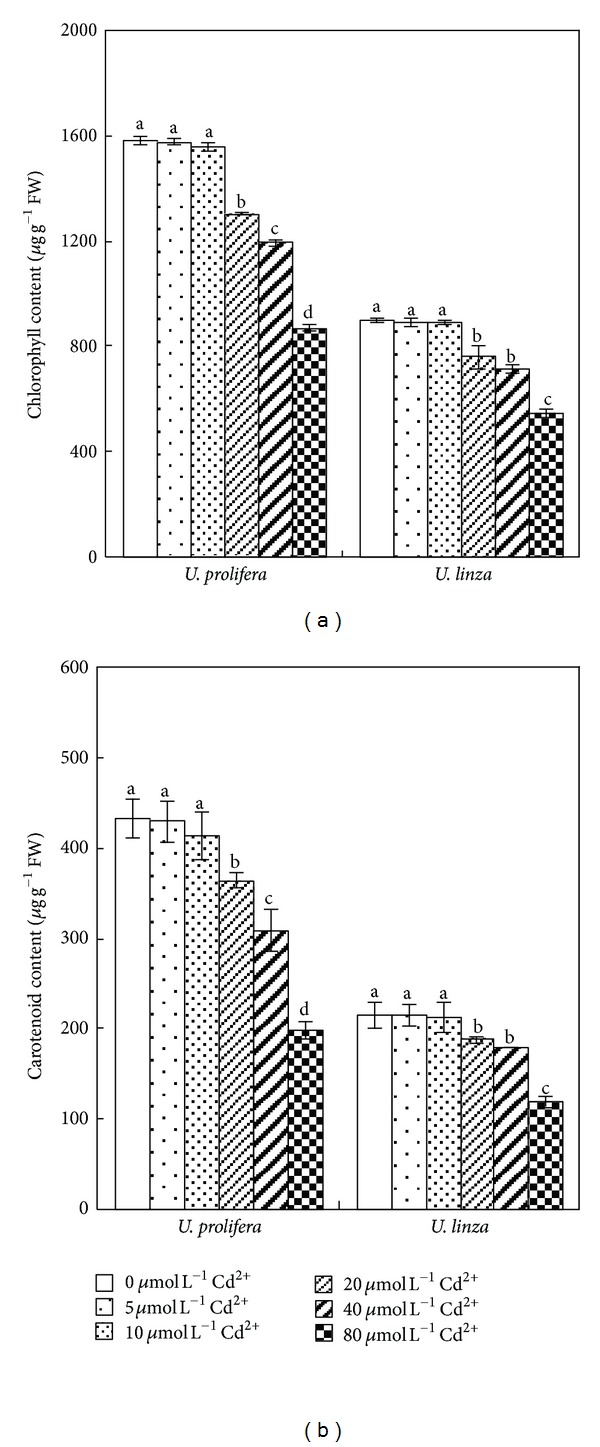

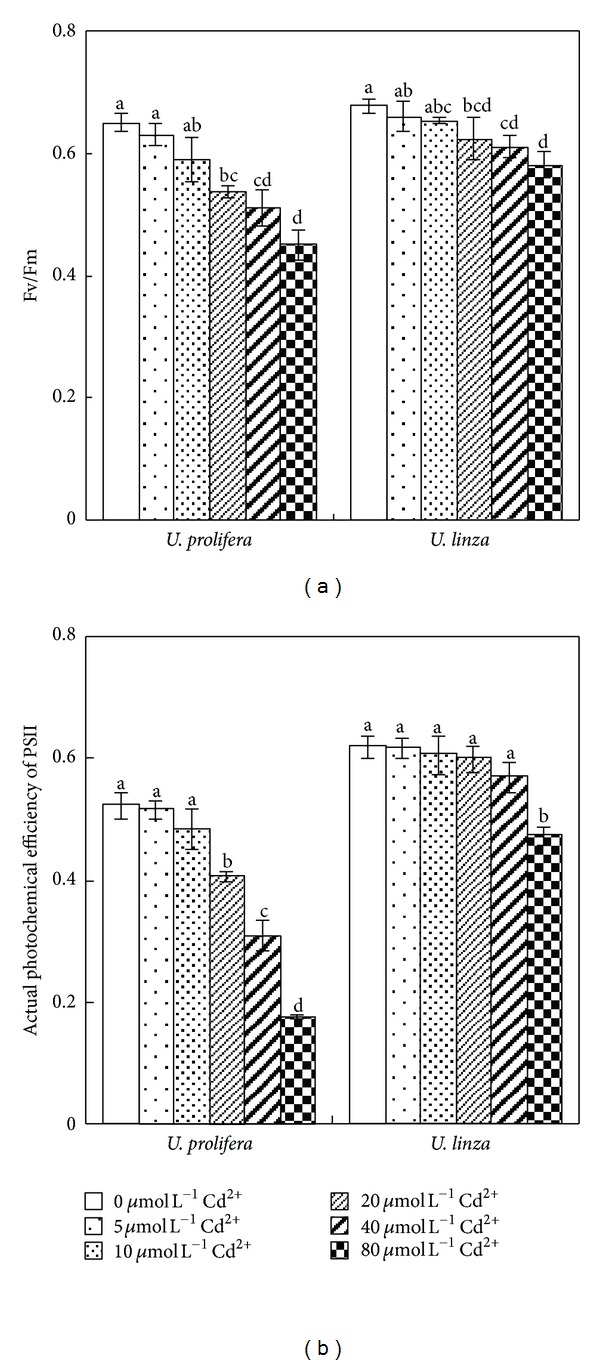

3.4. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters of U. prolifera and U. linza

Compared to the control treatment, Fv/Fm of U. prolifera and U. linza were not significantly affected by the treatments of 5 or 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+. However, Fv/Fm of both Ulva species fell significantly when Cd2+ concentrations reached 20 μmol L−1. In comparison with the control, Fv/Fm of U. prolifera decreased 17, 22, and 31% at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+; whereas Fv/Fm of U. linza decreased 9, 10, and 15% after exposure to 20, 40, or 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, respectively (Figure 5(a)). For actual photochemical efficiency of PSII (Yield) of U. prolifera, there was an obvious decrease when Cd2+ concentrations rose from 20 to 80 μmol L−1; whereas Yield of U. linza showed no significant decline until Cd2+ concentration was 80 μmol L−1 (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 30, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on Fv/Fm (a) and Yield (actual photochemical efficiency of PSII) (b) of U. prolifera and U. linza.

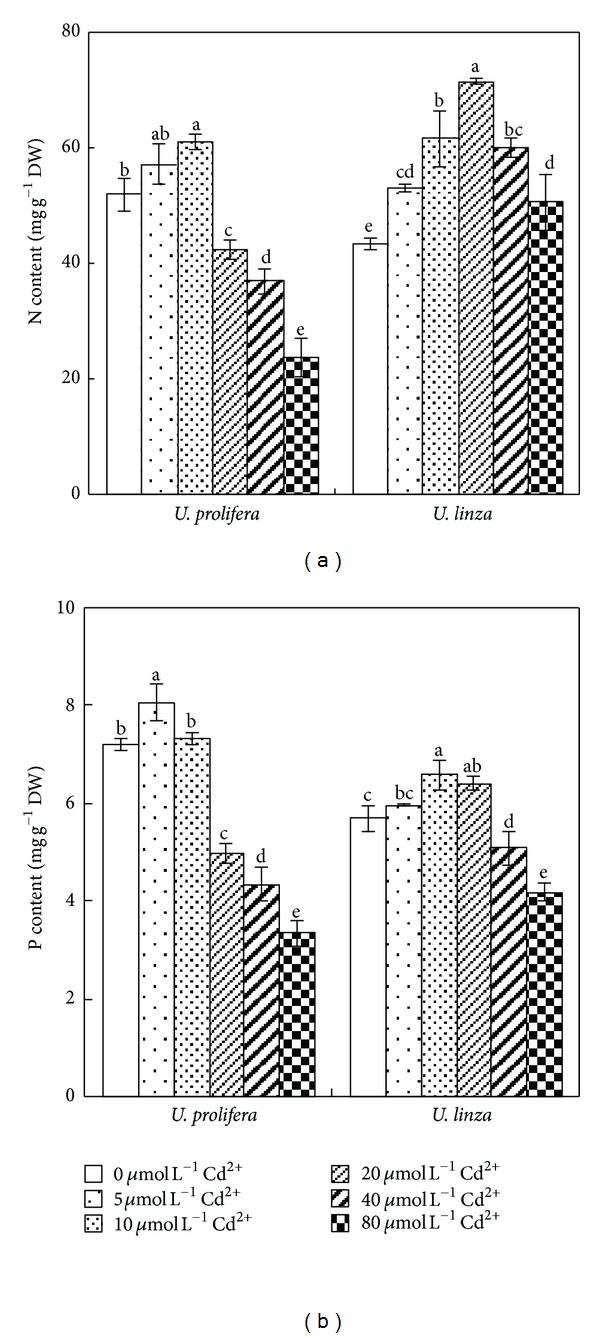

3.5. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Contents of N and P in U. prolifera and U. linza

Contents of N and P in both Ulva species showed a declining trend after an initial increase. The highest N content was recorded at 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ in U. prolifera and at 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+ in U. linza. N contents in U. linza in all Cd2+ treatments were higher than those of control; however, in U. prolifera, N contents at 20, 40, or 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ were significantly decreased compared to the control (Figure 6(a)).

Figure 6.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 μmol L−1) on contents of N (a) and P (b) of U. prolifera and U. linza.

U. prolifera had the highest P concentration at 5 μmol L−1 Cd2+; but the highest P concentration was observed when U. linza was treated by 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+. The P contents decreased 31, 40, and 54% at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ in U. prolifera, respectively. Compared to the control, the P concentration of U. linza at 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+ increased significantly, and then decreased by 11 and 27% under 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, respectively (Figure 6(b)).

3.6. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Inorganic Elements of U. prolifera and U. linza

The Na+ content of U. prolifera grown at 5 or 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ was not significantly different from the control, and it increased by 42, 67, and 83% at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, respectively. However, in U. linza, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μmol L−1 Cd2+ had no significant influence on Na+ content, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ increased Na+ content by 36% (Table 1). The K+ content of U. prolifera grown at 5 or 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ remained unaffected compared to the control; it decreased significantly by 41, 45, and 62% at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, respectively. In U. linza, 5, 10, and 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+ had no significant influence on K+ content, whereas 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ decreased K+ content by 34 and 50%, respectively (Table 1). The Ca2+ content of U. prolifera grown at 5, 10, 20, or 40 μmol L−1 Cd2+ remained unaffected, but increased significantly (24%) at 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+. However, in U. linza, 5 and 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ had no significant influence on Ca2+ contents, whereas 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ increased Ca2+ content by 22, 39, and 50%, respectively (Table 1). The Mg2+ content of U. prolifera grown at 5, 10, 20, 40 or 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ remained unaffected. With increasing Cd2+ concentrations, Mg2+ contents of U. linza showed an increasing trend after an initial decline (Table 1). The Cl− contents appeared to have a declining trend with increasing Cd2+ concentration similarly to Mg concentrations. However, no obvious difference in Cl− contents among all Cd2+ treatments was noted in the two Ulva species (Table 1). Nitrate content in U. prolifera showed an uptrend with increasing Cd2+ concentration; however, with increasing Cd2+ concentrations, nitrate content of U. linza showed a decline trend after an initial increase. We also found that nitrate contents of U. linza were much more than those of U. prolifera under all treatments except for 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of different concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 30, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on inorganic ion content (mmol g−1 DW), K+/Na+ and Ca2+/Na+ of U. prolifera and U. linza.

| Cd2+ treatment | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Cl− | NO3 − | K+/Na+ | Ca2+/Na+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmol L−1 | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | |||

| U. prolifera | 0 | 0.12 ± 0.01 c | 0.64 ± 0.04 a | 0.20 ± 0.02 b | 0.82 ± 0.04 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 a | 0.34 × 10−3 ± 0.03 × 10−3 c | 5.01 ± 0.12 a | 1.70 ± 0.08 a |

| 5 | 0.13 ± 0.02 c | 0.62 ± 0.05 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 ab | 0.78 ± 0.05 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.49 × 10−3 ± 0.06 × 10−3 c | 4.86 ± 0.21 a | 1.66 ± 0.07 a | |

| 10 | 0.12 ± 0.01 c | 0.63 ± 0.04 a | 0.23 ± 0.02 ab | 0.76 ± 0.05 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.78 × 10−3 ± 0.06 × 10−3 b | 5.10 ± 0.14 a | 1.84 ± 0.12 a | |

| 20 | 0.17 ± 0.02 b | 0.38 ± 0.03 b | 0.23 ± 0.02 ab | 0.75 ± 0.04 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 b | 1.41 × 10−3 ± 0.08 × 10−3 a | 2.26 ± 0.15 b | 1.39 ± 0.10 b | |

| 40 | 0.20 ± 0.02 ab | 0.35 ± 0.03 b | 0.25 ± 0.02 ab | 0.79 ± 0.04 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 1.40 × 10−3 ± 0.11 × 10−3 a | 1.74 ± 0.11 c | 1.24 ± 0.08 bc | |

| 80 | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 0.24 ± 0.02 c | 0.26 ± 0.02 a | 0.73 ± 0.05 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 1.43 × 10−3 ± 0.04 × 10−3 a | 1.12 ± 0.08 d | 1.14 ± 0.07 c | |

|

| |||||||||

| U. linza | 0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 b | 0.74 ± 0.04 a | 0.18 ± 0.02 c | 0.78 ± 0.04 a | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.86 × 10−3 ± 0.08 × 10−3 d | 3.02 ± 0.15 a | 0.72 ± 0.09 a |

| 5 | 0.24 ± 0.03 b | 0.74 ± 0.04 a | 0.17 ± 0.02 c | 0.75 ± 0.03 ab | 0.12 ± 0.01 b | 1.21 × 10−3 ± 0.10 × 10−3 c | 3.10 ± 0.23 a | 0.73 ± 0.08 a | |

| 10 | 0.24 ± 0.02 b | 0.73 ± 0.04 a | 0.18 ± 0.01 c | 0.72 ± 0.04 ab | 0.10 ± 0.02 b | 1.89 × 10−3 ± 0.07 × 10−3 a | 3.04 ± 0.12 a | 0.75 ± 0.06 a | |

| 20 | 0.24 ± 0.01 b | 0.68 ± 0.03 a | 0.22 ± 0.02 b | 0.64 ± 0.03 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 2.07 × 10−3 ± 0.12 × 10−3 a | 2.85 ± 0.11 b | 0.83 ± 0.07 a | |

| 40 | 0.26 ± 0.02 b | 0.49 ± 0.03 c | 0.25 ± 0.02 ab | 0.68 ± 0.03 b | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 1.65 × 10−3 ± 0.05 × 10−3 b | 1.67 ± 0.07 c | 0.88 ± 0.08 a | |

| 80 | 0.34 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.02 d | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.72 ± 0.04 ab | 0.12 ± 0.02 b | 1.12 × 10−3 ± 0.11 × 10−3 c | 1.10 ± 0.05 d | 0.75 ± 0.06 a | |

The data in the same column are statistically different if labeled with different letters according to Duncan's multiple range test (P ≤ 0.05).

The K+/Na+ and Ca2+/Na+ ratios in U. prolifera were not influenced by 5 and 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+, but they showed declining trends at 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ (Table 1). In U. linza, 5 and 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ had no significant influence on the K+/Na+ ratio, whereas 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ decreased that ratio by 6, 45, and 64%, respectively. However, in U. prolifera, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ decreased the K+/Na+ ratio by 55, 65, and 78%. No Cd2+ treatment significantly changed the Ca2+/Na+ ratio in U. linza.

3.7. Effect of Cadmium Stress on Organic Solutes in U. prolifera and U. linza

With increasing Cd2+ concentration, soluble sugar (SS) content appeared to have an ascending trend after an initial decline in both Ulva species. In U. prolifera, 40 μmol L−1 Cd2+ did not change the SS content, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ increased SS concentration by 27% compared to the control. However, in U. linza, 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ increased SS content by 40 and 90%, respectively (Table 2). In U. prolifera and U. linza, 5 μmol L−1 Cd2+ significantly increased free amino acid (FAA) content by 25 and 16%, respectively. However, 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ had no obvious change on FAA contents of the two Ulva species. Treatments with 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ significantly decreased FAA content by 52, 79, and 87% in U. prolifera and by 2, 25, and 43% in U. linza (Table 2). Proline (PRO) content was greatly enhanced by Cd2+ treatments in both Ulva species. At 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+, PRO content was increased 154, 431, 715, 1031, and 1069%, respectively, in U. prolifera; and increased 147, 420, 726, 1040, and 1147%, respectively, in U. linza (Table 2). Organic acid (OA) content in U. prolifera was not affected at 5, 10 and 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+, and OA concentration in U. linza was not affected at 5, 10, 20, and 40 μmol L−1 Cd2+. Treatments with 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ decreased OA content by 29 and 47%, respectively, in U. prolifera, whereas in U. linza only 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ decreased OA content by 27% (Table 2). The soluble protein (SP) content in the two Ulva species was not affected at 5, 10 and 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+ and was decreased at 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+. Treatments with 40 and 80 μmol L−1 Cd2+ significantly decreased SP content by, respectively, 16 and 42% in U. prolifera and by 8 and 25% in U. linza (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of different concentration of Cd2+ (0, 5, 10, 30, 40, and 80 μmol L−1) on organic solute content of U. prolifera and U. linza.

| Cd2+ treatment | SS | FAA | PRO | OA | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmol L−1 | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mmol g−1 DW | mg g−1 DW | |

| U. prolifera | 0 | 0.15 ± 0.02 b | 1.03 ± 0.05 b | 0.13 × 10−3 ± 0.02 × 10−3 e | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 42.15 ± 2.33 a |

| 5 | 0.15 ± 0.02 b | 1.29 ± 0.12 a | 0.33 × 10−3 ± 0.02 × 10−3 d | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 41.38 ± 2.76 a | |

| 10 | 0.12 ± 0.01 bc | 1.10 ± 0.04 ab | 0.69 × 10−3 ± 0.04 × 10−3 c | 0.19 ± 0.02 a | 40.45 ± 1.86 a | |

| 20 | 0.10 ± 0.01 c | 0.49 ± 0.11 c | 1.06 × 10−3 ± 0.07 × 10−3 b | 0.16 ± 0.02 a | 38.39 ± 2.75 ab | |

| 40 | 0.14 ± 0.01 b | 0.22 ± 0.05 d | 1.47 × 10−3 ± 0.09 × 10−3 a | 0.12 ±0.01 b | 35.53 ± 2.63 b | |

| 80 | 0.19 ± 0.01 a | 0.13 ± 0.06 d | 1.52 × 10−3 ± 0.12 × 10−3 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 c | 24.35 ± 1.88 c | |

|

| ||||||

| U. linza | 0 | 0.10 ± 0.01 cd | 1.23 ± 0.03 b | 0.15 × 10−3 ± 0.05 × 10−3 f | 0.11 ± 0.02 a | 39.27 ± 1.22 a |

| 5 | 0.10 ± 0.01 cd | 1.43 ± 0.09 a | 0.37 × 10−3 ± 0.02 × 10−3 e | 0.12 ± 0.01 a | 38.89 ± 2.37 ab | |

| 10 | 0.07 ± 0.01 d | 1.21 ± 0.10 b | 0.78 × 10−3 ± 0.03 × 10−3 d | 0.13 ± 0.01 a | 38.52 ± 2.67 ab | |

| 20 | 0.10 ± 0.01 c | 1.20 ± 0.06 b | 1.24 × 10−3 ± 0.08 × 10−3 c | 0.14 ± 0.02 a | 37.13 ± 1.89 ab | |

| 40 | 0.14 ± 0.02 b | 0.97 ± 0.06 c | 1.71 × 10−3 ± 0.07 × 10−3 b | 0.12 ± 0.01 a | 35.95 ± 2.41 b | |

| 80 | 0.19 ± 0.01 a | 0.76 ± 0.08 d | 1.87 × 10−3 ± 0.15 × 10−3 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 29.34 ± 1.87 c | |

Different letters in the same column indicate statistical difference according to Duncan's multiple range test (P ≤ 0.05). “SS, FAA, PRO, OA, and SP” in the table indicate the content of soluble sugar, free amino acid, proline, organic acid, and soluble protein, respectively.

3.8. Correlation Analysis between RGR and Other Physiological and Biochemical Indexes under Cadmium Stress

Correlation analysis indicated that RGR of both Ulva species was insignificantly related to contents of Chl, Car, Na+ and Mg2+, and the Ca2+/Na+ ratio. In contrast, RGR was highly negative correlated with the contents of Cd2+, Ca2+, SS, and PRO, and highly positive correlated with the contents of N, P, K, Cl, FAA, OA and SP, K+/Na+ ratio, OAA, Fv/Fm, and Yield (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between RGR and other indices for U. prolifera and U. linza.

| Index | Correlation coefficient |

|---|---|

| Chl content | 0.072 |

| Car content | 0.198 |

| Fv/Fm | 0.830** |

| Yield | 0.858** |

| Cd2+ content | −0.899** |

| N content | 0.561** |

| P content | 0.687** |

| OAA | 0.766** |

| Na+ content | −0.138 |

| K+ content | 0.881** |

| Ca2+ content | −0.677** |

| Mg2+ content | 0.060 |

| Cl− content | 0.444** |

| K+/Na+ | 0.627** |

| Ca2+/Na+ | −0.079 |

| SS content | −0.617** |

| FAA content | 0.828** |

| PRO content | −0.841** |

| OA content | 0.731** |

| SP content | 0.752** |

*Significant at 5% level, **significant at 1% level (two-tailed, n = 18).

4. Discussion

Plant growth can be suppressed by Cd [7, 17]. It was reported that Ulva lactuca was sensitive to cadmium, as obviously shown by growth reduction and lethal effects at 40 μmol L−1 Cd2+ within 6 days [27]. In the study presented here, U. prolifera and U. linza, the dominant free-floating Ulva species of green tide bloom in the Yellow Sea of China [28], showed sensitivity to Cd2+ (reduction in RGR, Fv/Fm, and Yield). Furthermore, this reduction was found to be more pronounced in U. prolifera than U. linza. After 7 d, U. prolifera died at 120 μmol L−1 Cd2+, whereas U. linza was still alive (Figures 1 and 4). This result indicated that U. linza had better adaptation to Cd2+ toxicity than U. prolifera.

It is known that marine macroalgae can concentrate heavy metals to a large extent [2, 29]. In this study, Cd accumulation in U. prolifera and U. linza increased significantly in response to increased Cd2+ concentrations. However, U. prolifera accumulated more Cd than U. linza (Figure 3). In general, plant accumulation of a given metal is a function of uptake capacity and intracellular binding sites [30]. The cell walls of plant cells contain proteins and different carbohydrates that can bind metal ions. After the binding sites in the cell wall become saturated, intracellular Cd accumulation mediated by metabolic processes may lead to cell toxicity [31].

Ulva species are widely distributed in the coastal intertidal zones where had full change on salinity level. Thus, many Ulva species have strong OAA to cope with variable and heterogeneous environments. Similarly to a number of other stresses, heavy metal toxicity can decrease cell water content and lower the cell water potential (ψ w) through increased net concentrations of solutes (osmotic adjustment), which is a common response to water stress and an important mechanism for maintaining cell water content and, thus, turgor [18, 32]. In our experiments, OAA of U. linza had positive values in the treatments with 5, 10, or 20 μmol L−1 Cd2+, whereas U. prolifera had positive OAA only at 5 and 10 μmol L−1 Cd2+ (Figure 2). When OAA values in Ulva were positive, that is, OAA contributed to maintaining turgor, Ulva could continue growing, and RGR was positive. However, when OAA in Ulva was negative resulting in turgor loss, the growth was stopped, and RGR was negative. Correlation analysis also showed that RGR was positively related to OAA, suggesting that OAA played an important role in maintaining algal growth. Also, good osmotic adjustment enabled plants to maintain high photosynthetic activity (Figure 5).

Cadmium is a nonessential element for plant growth, and it inhibits uptake and transport of many macro- and micronutrients, inducing nutrient deficiency [7, 17]. Contradictory data can be found in the literature on the effects exerted by Cd2+ on terrestrial plant. Cadmium was reported to reduce uptake of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, Ni, and Na in many crop plants [33], whereas other authors found reduced K uptake but unchanged P uptake or even an increase in K content of several crop varieties under Cd2+ stress [34, 35]. Obata and Umebayashi [36] reported that Cd2+ treatment increased Cu content in the roots of pea, rice, and maize, but unchanged Cu content in cucumber and pumpkin plants. With Cd2+ stress, Maksimović et al. [37] observed a reduction in the maize root influx and root-shoot transport of Cu, Zn, and Mn, a reduction in the root-shoot transport of Fe, but an increase in Fe influx and Ca and Mg transport. In this study, the response of total N and P concentrations in tissues of the two Ulva species to Cd2+ treatments was positively related to their Cd resistance. We found that the treatment with low concentration of Cd2+ enhanced N and P contents, but high concentrations of Cd2+ (≥20 μmol L−1) decreased N and P contents in both Ulva species. The maintenance of total N and total P was more pronounced in less Cd-sensitive U. linza than Cd-sensitive U. prolifera (Figure 6). This suggests that the maintenance of a normal level of total N content upon challenge with Cd is likely to be a feature in relative Cd-resistant marine macroalga, similarly to terrestrial plants [38]. In Ulva, we found that the contents of K+, Ca2+, and Cl− were related to RGR, especially K+reduction caused Ulva growth reduction significantly (Table 1). Thus, the K+/Na+ ratio in both Ulva species decreased significantly with increasing Cd2+ treatment concentrations, and Cd2+-sensitive U. prolifera showed a greater K+/Na+ decline than Cd2+-sensitive U. linza (Table 1).

We measured a decline in soluble sugar (SS) concentration at low Cd2+ treatment concentrations and an increase at high Cd2+ concentrations in both Ulva species. Moreover, the SS increase of U. linza is more marked than that of U. prolifera. In other studies, the decline in SS concentration corresponded with the photosynthetic inhibition or stimulation of respiration rate, affecting carbon metabolism and leading to production of other osmotica [39]. The accumulating soluble sugars in plants growing in presence of Cd2+ could provide an adaptive mechanism via maintaining a favorable osmotic potential under adverse conditions of Cd2+ toxicity [40].

Soluble protein (SP) content in organisms is an important indicator of metabolic changes and responds to a wide variety of stresses [41]. In this work, SP contents in U. prolifera and U. linza declined with increasing Cd2+ treatment concentrations. Free amino acid (FAA) contents in both Ulva species first increased and then declined, with such a decline more pronounced in U. prolifera than in U. linza. The decreased protein content together with the increased free amino acid content suggest that the protein synthesizing machinery was impaired due to the Cd2+ effect [42].

PRO accumulation in plant tissues in response to a number of stresses, including drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, ultraviolet radiation, or heavy metals, is well documented [43]. In this study, even though PRO content was increased in Cd2+-treated Ulva, its absolute amount was relatively low. Under assumed localization of inorganic ions in the vacuole and organic solutes in the cytoplasm, FAA and PRO may be mainly in the cytoplasm, accounting for about 5%–10% volume in mature cells [44]. A small amount of FAA and PRO accumulating in the cytoplasm can increase concentration significantly and play an important role in balancing vacuolar osmotic potential [44]. It has often been suggested that PRO accumulation may contribute to osmotic adjustment at the cellular level [39]. In addition, PRO as a compatible solute may protect enzymes from dehydration and inactivation [18].

In conclusion, exposing U. prolifera and U. linza to different concentrations of Cd2+ resulted in the changes in growth, pigment content, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, Cd accumulation, OAA, and concentration of N, P, main inorganic ions, and organic solutes. These changes make U. linza better adapted to withstanding Cd2+ stress in comparison with U. prolifera. Our results highlight the role of osmotic adjustment in Ulva during Cd2+ stress as an important mechanism enabling Ulva to maintain photosynthetic activity and, thus, growth under Cd2+ stress.

Authors' Contribution

H. Jiang and B. Gao both contributed equally to this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank professor Zed Rengel, University of Western Australia, for his helpful comments on this study. Also, they thank professor Jianjun Chen, University of Florida, for his good revision on this paper. This work was supported by Open Foundation of Key Laboratory of Exploitation and Preservation of Coastal Bio-resources of Zhejiang Province (2010F30003), the National Key Project of Scientific and Technical Supporting Programs funded by Ministry of Science and Technology of China (no. 2009BADA3 B04-8). The authors also acknowledge members of our laboratory for assistance in this work.

References

- 1.Zhu L, Xu J, Wang F, Lee B. An assessment of selected heavy metal contamination in the surface sediments from the South China Sea before 1998. Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 2011;108(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sari A, Tuzen M. Biosorption of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution using green alga (Ulva lactuca) biomass. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2008;152(1):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.06.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu B, Yang X, Gu Z, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Lv Y. The trend and extent of heavy metal accumulation over last one hundred years in the Liaodong Bay, China. Chemosphere. 2009;75(4):442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodeiro P, Cordero B, Barriada JL, Herrero R, Sastre De Vicente ME. Biosorption of cadmium by biomass of brown marine macroalgae. Bioresource Technology. 2005;96(16):1796–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volesky B, Holan ZR. Biosorption of heavy metals. Biotechnology Progress. 1995;11(3):235–250. doi: 10.1021/bp00033a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster EA, Murphy AJ, Chudek JA, Gadd GM. Metabolism-independent binding of toxic metals by Ulva lactuca: cadmium binds to oxygen-containing groups, as determined by NMR. BioMetals. 1997;10(2):105–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar M, Kumari P, Gupta V, Anisha PA, Reddy CRK, Jha B. Differential responses to cadmium induced oxidative stress in marine macroalga Ulva lactuca (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) BioMetals. 2010;23(2):315–325. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajialigol S, Taher MA, Malekpour A. A new method for the selective removal of cadmium and zion ions from aqueous solution by modified clinoptilolite. Adsorption Science and Technology. 2006;24(6):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheng PX, Ting YP, Chen JP, Hong L. Sorption of lead, copper, cadmium, zinc, and nickel by marine algal biomass: characterization of biosorptive capacity and investigation of mechanisms. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2004;275(1):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Sikaily A, Nemr AE, Khaled A, Abdelwehab O. Removal of toxic chromium from wastewater using green alga Ulva lactuca and its activated carbon. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2007;148(1-2):216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karthikeyan S, Balasubramanian R, Iyer CSP. Evaluation of the marine algae Ulva fasciata and Sargassum sp. for the biosorption of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions. Bioresource Technology. 2007;98(2):452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masakorala K, Turner A, Brown MT. Influence of synthetic surfactants on the uptake of Pd, Cd and Pb by the marine macroalga, Ulva lactuca . Environmental Pollution. 2008;156(3):897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Say PJ, Burrows IG, Whitton BA. Enteromorpha as a monitor of heavy metals in estuaries. Hydrobiologia. 1990;195:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malea P, Rijstenbil JW, Haritonidis S. Effects of cadmium, zinc and nitrogen status on non-protein thiols in the macroalgae Enteromorpha spp. from the Scheldt Estuary (SW Netherlands, Belgium) and Thermaikos Gulf (N Aegean Sea, Greece) Marine Environmental Research. 2006;62(1):45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin A, Shen S, Wang G, et al. Comparison of chlorophyll and photosynthesis parameters of floating and attached Ulva prolifera . Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2011;53(1):25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yarish C, Chopin T, Wilkes R, Mathieson AC, Fei XG, Lu S. Domestication of Nori for northeast America: the Asian experience. Bulletin of Aquaculture Association of Canada. 1999;1:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia JR, Li YJ, Lu J, Chen B. Effects of copper and cadmium on growth, photosynthesis, and pigment content in Gracilaria lemaneiformis . Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2004;73(6):979–986. doi: 10.1007/s00128-004-0522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Q, Liu Z, Chen G, Gao Y, Li Q, Wang J. Comparison of osmotic regulation in dehydrationand salinity-stressed sunflower seedlings. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 2010;33(7):966–981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Häder DP, Lebert M, Helbling EW. Effects of solar radiation on the Patagonian macroalga Enteromorpha linza (L.) J. Agardh—Chlorophyceae. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B. 2001;62(1-2):43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamer K, Fong P. Nitrogen enrichment ameliorates the negative effects of reduced salinity on the green macroalga Enteromorpha intestinalis . Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2001;218:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu FB, Dong J, Qiong QQ, Zhang GP. Subcellular distribution and chemical form of Cd and Cd-Zn interaction in different barley genotypes. Chemosphere. 2005;60(10):1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilliam MB, Sherman MP, Griscavage JM, Ignarro LJ. A spectrophotometric assay for nitrate using NADPH oxidation by Aspergillus nitrate reductase. Analytical Biochemistry. 1993;212(2):359–365. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Q, Yu B. Changes in content of free, conjugated and bound polyamines and osmotic adjustment in adaptation of vetiver grass to water deficit. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2010;48(6):417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72(1-2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irigoyen JJ, Emerich DW, Sanchezdiaz M. Water-stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Plant Physiology. 1992;84(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song J, Feng G, Tian CY, Zhang FS. Osmotic adjustment traits of Suaeda physophora, Haloxylon ammodendron and Haloxylon persicum in field or controlled conditions. Plant Science. 2006;170(1):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markham JW, Kremer BP, Sperling KR. Cadmium effects on growth and physiology of Ulva lactuca . Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen. 1980;33(1–4):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu D, Keesing JK, Dong Z, et al. Recurrence of the world’s largest green-tide in 2009 in Yellow Sea, China: Porphyra yezoensis aquaculture rafts confirmed as nursery for macroalgal blooms. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2010;60(9):1423–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumann HA, Morrison L, Stengel DB. Metal accumulation and toxicity measured by PAM—Chlorophyll fluorescence in seven species of marine macroalgae. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2009;72(4):1063–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benavides MP, Gallego SM, Tomaro ML. Cadmium toxicity in plants. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2005;17(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu S, Tang CH, Wu M. Cadmium accumulation by several seaweeds. Science of the Total Environment. 1996;187(2):65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milone MT, Sgherri C, Clijsters H, Navari-Izzo F. Antioxidative responses of wheat treated with realistic concentration of cadmium. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2003;50(3):265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanità Di Toppi L, Gabbrielli R. Response to cadmium in higher plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 1999;41(2):105–130. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nocito FF, Pirovano L, Cocucci M, Sacchi GA. Cadmium-induced sulfate uptake in maize roots. Plant Physiology. 2002;129(4):1872–1879. doi: 10.1104/pp.002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciecko Z, Kalembasa S, Wyszkowski M, Rolka E. The effect of elevated cadmium content in soil on the uptake of nitrogen by plants. Plant, Soil and Environment. 2004;50(7):283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obata H, Umebayashi M. Effects of cadmium on mineral nutrient concentrations in plants differing in tolerance for cadmium. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1997;20(1):97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maksimović I, Kastori R, Krstić L, Luković J. Steady presence of cadmium and nickel affects root anatomy, accumulation and distribution of essential ions in maize seedlings. Biologia Plantarum. 2007;51(3):589–592. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghnaya T, Slama I, Messedi D, Grignon C, Ghorbel MH, Abdelly C. Effects of Cd2+ on K+, Ca2+ and N uptake in two halophytes Sesuvium portulacastrum and Mesembryanthemum crystallinum: consequences on growth. Chemosphere. 2007;67(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.John R, Ahmad P, Gadgil K, Sharma S. Effect of cadmium and lead on growth, biochemical parameters and uptake in Lemna polyrrhiza L. Plant, Soil and Environment. 2008;54(6):262–270. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma S, Dubey RS. Effect of cadmium on soluble sugars and enzymes of their metabolism in rice. Biologia Plantarum. 2001;44(1):117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh PK, Tewari RK. Cadmium toxicity induced changes in plant water relations and oxidative metabolism of Brassicajuncea L. plants. Journal of Environmental Biology. 2003;24(1):107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jana S, Choudhuri MA. Synergistic effects of heavy metal pollutants on senescence in submerged aquatic plants. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 1984;21(1–4):351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delmail D, Labrousse P, Hourdin P, Larcher L, Moesch C, Botineau M. Differential responses of Myriophyllum alterniflorum DC (Haloragaceae) organs to copper: physiological and developmental approaches. Hydrobiologia. 2011;664(1):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munns R, Tester M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59:651–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]