Abstract

Objective

To estimate differences in continuation of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) between U.S.-resident women obtaining pills in U.S. family planning clinics compared with over-the-counter in Mexican pharmacies.

Methods

In El Paso, Texas, we recruited 514 OCP users who obtained pills over-the-counter from a Mexican pharmacy and 532 who obtained OCPs by prescription from a family planning clinic in El Paso. A baseline interview was followed by three consecutive surveys over 9 months. We asked about date of last supply, number of pill packs obtained, how long they planned to continue use, and experience of side effects. Retention was 90%, with only 105 women lost to follow-up.

Results

In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, discontinuation was higher for women who obtained pills in El Paso clinics (25.1%) compared with those who obtained their pills without a prescription in Mexico (20.8% [hazard ratio 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1--2.3]). Considering the number of pill packs dispensed to clinic users, discontinuation rates were higher (hazard ratio 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2 -- 2.7) for clinic users who received 1-5 pill packs. However, there was no difference in discontinuation between clinic users receiving 6 or more pill packs and users obtaining pills without a prescription.

Conclusion

Results suggest providing OCP users with more pill packs and removing the prescription requirement would both lead to increased continuation.

INTRODUCTION

Almost half of women who initiate use of oral contraceptives (OCPs) discontinue the method during the first year of use (1). Among the reasons given for OCP discontinuation are the side effects experienced by pill users, as well as poor compliance with the regimen of taking one pill each day (2-4). Access issues also have been found to contribute to OCP discontinuation. A study of contraceptive use patterns in the US found that 10% of gaps in OCP use were attributable to difficulty paying for a method and lack of time for medical visits (5). Additionally, a study of Medicaid claims data from California showed that women given 13 pill packs had greater OCP continuation and fewer gaps in coverage than women who received three or fewer packs (6). Most recently, a clinical trial randomizing subjects to receive a 3- or 7-month supply of OCPs showed significantly higher continuation rates for women receiving more pill packs (51% vs. 35%) (7).

Another way to reduce access barriers would be to make OCPs available over-the-counter (8). Two surveys of US women found that between 40 and 60% of non-users said they would be more likely to use OCPs if they were available in a pharmacy without a prescription (9, 10).

The objective of this study is to estimate how both of these measures of access, the number of pill packs dispensed and providing over-the-counter access to the pill, are associated with OCP continuation. To simulate the latter measure, we take advantage of the natural experiment along the US-Mexico border, where US residents can access OCPs without a prescription in Mexican pharmacies for approximately US$5 per cycle (11). By comparing OCP continuation between users who obtained pills in US clinics and those who obtained them over the counter in Mexican pharmacies, we gain insight into what might be expected with regard to continuation if OCPs were made more easily accessible in the US.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Border Contraceptive Access Study was conducted in El Paso, Texas from 2006 through 2008. El Paso, Texas with a population of 800,000 people is located on the US-Mexico border directly across from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. The majority of the El Paso population is Hispanic/Latino and many residents regularly cross the border into Mexico for health services because of lower costs and convenience as well as social ties, cultural familiarity, and perceived quality of care (12-15).

Using convenience sampling, we recruited current OCP users aged 18 to 44 stratified into two groups: 1) El Paso residents who use OCPs and obtained their last pack at a family planning clinic in El Paso (target n=500); and 2) El Paso residents who use OCPs obtained their last pack over-the-counter (OTC) at a pharmacy in Mexico (target n=500). There were no inclusion criteria other than age, source of last pack, and residency in El Paso. Respondents were interviewed up to 4 times at 3-month intervals. Further information on recruitment strategies and the interview process is available in an earlier paper (11). For completing the baseline interview and each of the follow-up interviews, participants were offered a small compensation (up to $75 total). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Texas at Austin and University of Texas at El Paso.

The initial (or baseline) questionnaire collected information on the participant’s background (age, marital status, parity) as well as the month and year a participant obtained her last pill pack(s), the number of packs acquired at that time, where she got her packs, experience of side effects, the duration of her current OCP segment, and how long she planned on using OCPs as her method of contraception. In all subsequent interviews, women were asked about changes in their contraceptive practice during the prior three months, the source and number of pill packs obtained if she resupplied since the previous interview, and, again, how she long she planned to use OCPs. The second and third interviews were administered via telephone, while the final (fourth) interview was conducted in person.

In total, we recruited 1046 OCP users who completed baseline interviews—514 women who obtained OCPs from Mexican pharmacies and 532 women who obtained OCPs from El Paso family planning clinics. Overall, 90% of participants completed the study, with only 105 women lost to follow-up. Of the 965 women who completed the second interview and were thus eligible for this analysis, 24 cases were dropped because of missing or incomplete data.

Sociodemographic characteristics, side effects of OCPs, and planned OCP use were calculated for clinic and OTC users separately. The statistical significance of differences between these groups was determined using Chi-square tests of the homogeneity of proportions. Next, following Westhoff et al. (16), we defined OCP discontinuation as having not taken any active OCP for more than seven days, and probed in each interview for any discontinuation. If the woman reported stopping, we asked for the date of discontinuation (month and year) as well as the reason for stopping. In addition to 13 precoded reasons for discontinuation, we probed with an open-ended question about why the respondent stopped taking OCPs. We recoded the reason for stopping into four categories: 1) stopped in order to become pregnant or because no longer needed contraception, 2) stopped to switch to another method, 3) became pregnant while using OCPs, and 4) stopped because of side effects or other problems with OCPs.

We separated exposure to the risk of discontinuation into separate segments corresponding to the intervals between interviews (approximately 90 days) for a maximum of three segments. How long a woman planned to continue using OCPs was updated at each successive interview. For women who had resupplied between interviews, we further divided their use segments on the date they reported last obtaining pill packs, and updated source of OCPs and number of packs accordingly.

We calculated Kaplan-Meier estimates of continuation for clinic and cross-border OTC users based on the elapsed time since the baseline interview. These quantities are estimated for all reasons for discontinuation, as well as for selected method-related reasons (3 and 4 above: method failure, side effects and other reasons). We focus on these two types of discontinuation since they are especially likely to lead to an unwanted pregnancy, unlike stopping to switch to another method or to become pregnant (1). Log-rank tests were used to assess equality of survivor functions.

We estimated three Cox proportional hazards models to test for differences in the risk of discontinuation for the selected method-related reasons between women who obtained their OCPs in El Paso clinics and those who obtained their OCPs over-the-counter in Mexico. In the first, the source of contraception is the only predictor of discontinuation. In the second, we also adjust for differences between women in the two arms of the study identified in a previous analysis (age, country of birth/country where education was completed, receipt of government assistance, US health insurance, and border-crossing frequency (11)), as well as three additional variables assessed in the baseline interview that could be expected to have a direct impact on a woman’s motivation to continue using OCPs: duration of use, experience of side effects attributable to the pill, and how long the woman reported she planned to use OCPs.

In a further effort to assess the impact of access and convenience on OCP continuation, we estimated a third model that divided the El Paso clinic users according to the number of pill packs they received the last time they resupplied. Users were separated into those receiving 1-5 packs and those receiving 6 or more packs, with source and number of packs updated on the basis of the information collected at successive interviews. If having to visit the clinic to resupply pill packs constitutes a significant barrier to use, we would expect to find higher rates of discontinuation among women provided fewer packs. However, since family planning clinics in El Paso were operating under severe budget constraints at the time of the study, clinic personnel were wary of giving out large numbers of packs to clients they felt might soon discontinue and waste the OCPs. Thus, the number of packs dispensed was likely based on the clinic personnel’s prognosis of continuation, and was therefore subject to indication bias (17).

We attempt to diminish any confounding resulting from indication by adjusting for characteristics found to be associated with the number of pill packs dispensed to clinic users as well as all the other predictors included in the second model. For all Cox proportional hazards models, estimates of the effects of risk factors were obtained using Efron’s method for handling tied event times(18). Additionally, we performed conventional diagnostic tests for non-proportional effects, outliers, and influential observations to check the robustness of our findings (19-20).

The target sample size for the study, 500 clinic users and 500 cross-border OTC users, was chosen with multiple analyses in mind since we planned to analyze knowledge of how to take the pill, use of preventive screening services, and prevalence of contraindications in addition to continuation. With a projected cumulative loss to follow-up of 19%, the target sample size would allow us to test for a ten percentage point one-sided difference between proportions (from 0.7 to 0.6) in the two cohorts of the study with power of 0.9, and an alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 (21).

RESULTS

Social and demographic characteristics for the OCP users eligible for this analysis are shown in Table 1 according to their source of OCPs at the baseline interview. In comparison with El Paso clinic users, cross-border OTC users were more likely to be older, have higher parity, born in Mexico, and completed their last year of schooling in Mexico. They were less likely to have US health insurance, and, not surprisingly, crossed the border more frequently. The cross-border OTC users also had been using OCPs for longer, and were less likely to report experiencing side effects at the baseline interview. However, the answers women gave to the question regarding how long they expected to use OCPs were distributed quite evenly between the two cohorts. Among the cross-border OTC users, the proportion reporting that they only planned to use OCPs for three months or less was higher while the proportion reporting that they planned to use OCPs for two years or more was lower compared with El Paso clinic users.

Table 1.

Characteristics of users by source of OCPs

| Characteristics | Prescription (n = 474) |

OTC (n = 466) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, No. (%) | |||

| 18-24 years | 157 (33.1) | 100 (21.5) | |

| 25-34 years | 210 (44.3) | 200 (42.9) | [lt].001 |

| 35-44 years | 107 (22.6) | 166 (35.6) | |

| Parity, No. (%) | |||

| 0 live births | 86 (18.1) | 55 (11.8) | |

| 1 live birth | 79 (16.7) | 78 (16.8) | .02 |

| 2 or more live births | 309 (65.2) | 332 (71.4) | |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | |||

| Married/Cohabiting | 300 (63.3) | 320 (68.7) | .08 |

| Single | 174 (36.7) | 146 (31.3) | |

| Nativity/Education, No. (%) | |||

| US-born | 177 (37.3) | 97 (20.8) | |

| Mexican-born, US-educated | 163 (34.4) | 167 (35.8) | [lt].001 |

| Mexican-born and educated | 134 (28.3) | 202 (43.4) | |

| Border crossing frequency. No. (%) | |||

| Never/almost never | 239 (50.4) | 132 (28.3) | |

| Less than once per month | 77 (16.2) | 51 (10.9) | [lt].001 |

| 1-3 times per month | 101 (21.3) | 162 (34.8) | |

| Once per week or more | 57 (12.0) | 121 (26.0) | |

| Receives US government assistance, No. (%) | 363 (76.6) | 334 (71.7) | .09 |

| Has US health insurance, No. (%) | 113 (23.8) | 51 (10.9) | [lt].001 |

| Duration of OCP use prior to study, No. (%) | |||

| Short duration (less than 200 days) | 150 (31.7) | 107 (23.0) | |

| Medium duration (200-1500 days) | 210 (44.3) | 221 (47.4) | .01 |

| Long duration (greater than 1500 days) | 114 (24.1) | 138 (29.6) | |

| Side effects related to OCP use, No. (%) | |||

| Did not report side effects | 330 (69.6) | 362 (77.7) | |

| Reported side effects | 144 (30.4) | 104 (22.3) | .01 |

| Planned OCP use, No. (%) | |||

| 3 months or less | 9 (1.9) | 18 (3.9) | |

| 4-12 months | 22 (4.6) | 29 (6.2) | .05 |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 103 (21.7) | 125 (26.8) | |

| Two years or more | 267 (56.3) | 229 (49.1) | |

| Don’t know/Not sure | 73 (15.4) | 65 (14.0) | |

Of the 941 OCP users, 216 discontinued use during the approximately nine-month period of observation (see Table 2). Among those who discontinued use, 15% did so because of method failure, 19% stopped in order to become pregnant, and nearly 60% stopped because of side effects or other reasons. Only 14 women reported stopping OCPs in order to switch to another method of contraception. However, a larger proportion of participants switched source of OCPs during follow-up: 44 cross-border OTC users (as measured at the baseline interview) switched to another source for OCPs (20 became clinic users and 24 switched to another source such as a private doctor’s office--data not shown). Among women who were initially El Paso clinic users, 40 became cross-border OTC users and 27 switched to another source.

Table 2.

Discontinuation by source of OCs

| All OC Users | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription (n = 474) | OTC (n = 466) | P-Value | |

|

Discontinued OC use, No.

(%) |

119 (25.1) | 97 (20.8) | 0.12 |

| Discontinued OC Users | |||

| Prescription (n = 119) | OTC (n = 97) | P-Value | |

| Reason for OC | |||

| discontinuationa, No. (%) | |||

| Wanted to get pregnant | 21 (17.7) | 20 (20.6) | |

| Switched methods | 5 (4.2) | 9 (9.3) | 0.39 |

| Got pregnant | 18 (15.1) | 15 (15.5) | |

| Side effects/Other reasons | 75 (63.0) | 53 (54.6) |

Among those who discontinued OC use.

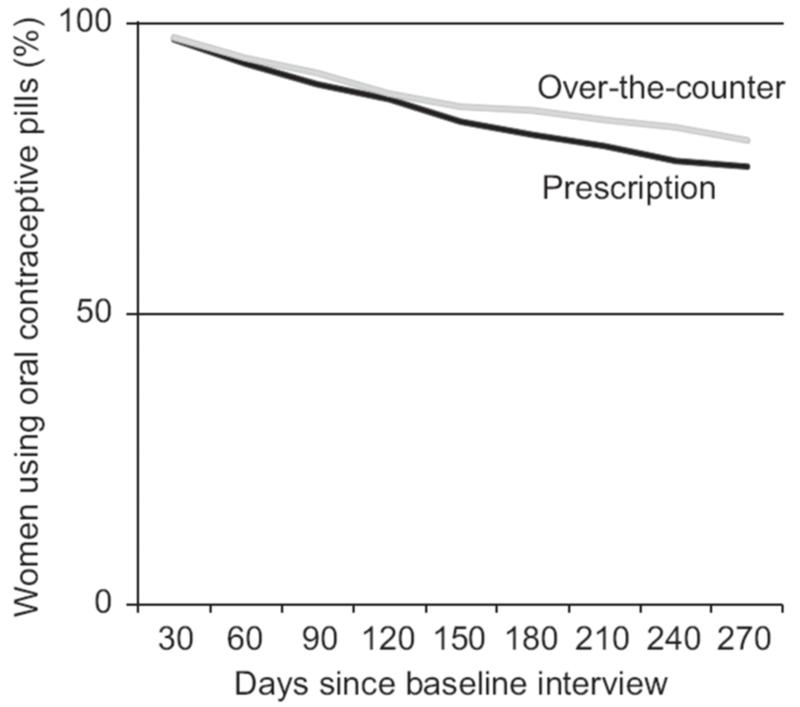

Life table estimates of continuation at nine months following the initial interview were nearly 5% higher for cross-border OTC users than for El Paso clinic users (see Figure 1). This difference was consistent for discontinuation for all reasons and discontinuation due to method-related reasons. The log-rank test for equality of survivor functions was rejected at p < 0.01 in both pairs of life tables.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survivor function of oral contraceptive pill (OCP) continuation by duration (days) and source of OCPs.

In the first Cox proportional hazard model with no covariates, the risk of discontinuation due to method-related reasons is significantly higher for El Paso clinic users compared with cross-border OTC users (1.48—95% C. I.: 1.07, 2.04). After adjusting for covariates in the second model, the estimated risk ratio increased slightly (1.58—95% C. I.: 1.11, 2.26).

The final Cox model of discontinuation for method-related reasons separated clinic users based on the number of pill packs they were given the last time they resupplied (Table 3). We found that about 35% of clinic users received six or more packs, and that clinic users who were both married and had children were especially likely to have been supplied with six or more packs (data not shown). Thus, this model adjusts not only for length of planned use, duration of use at baseline, side effects, and predictors of source but also for parity and marital status. Relative to cross-border OTC users, the adjusted rate of discontinuation is nearly identical for clinic users who received six or more packs, but 80% higher (hazard ratio 1.80, 95% CI: 1.22--2.65) for clinic users supplied with fewer than six packs. In this model, as we expected, length of planned use reported at baseline was strongly associated with the hazard of method-related discontinuation, but experience of side effects was not a significant predictors of this hazard. None of the other variables included in the model was significantly associated with discontinuation. Tests revealed no departure from the proportional hazards assumption in any of the models, and in particular no evidence of a non-proportional effect for the main variables of interest, source and number of packs (p>0.67).

Table 3.

OCP discontinuation risk for Prescription-Only versus OTC users: Discontinuation due to pregnancy, side effects, or other reasons

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Source/Number of pill packs | |

| Cross-Border Pharmacy | [lsqb]Reference[rsqb] |

| El Paso Clinic, 1-5 pill packs | 1.80 (1.22, 2.65) |

| El Paso Clinic, ≥ 6 pill packs | 1.11 (0.66, 1.87) |

| Planned OCP Use | |

| 3 months or less | 3.40 (1.71, 6.74) |

| 4-12 months | 2.04 (1.09, 3.80) |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 1.55 (0.99, 2.43) |

| Two years or more | [lsqb]Reference[rsqb] |

| Don’t know/Not sure | 1.25 (0.77, 2.03) |

| Side effects of OCP use | |

| Did not report side effects | [lsqb]Reference[rsqb] |

| Reported side effects | 1.37 (0.96, 1.96) |

Model also controls for duration of OCP use at baseline, parity/marital status, nativity/education, border crossing frequency, US government assistance, US health insurance, age groups.

DISCUSSION

We observed lower rates of OCP discontinuation for cross-border OTC users than for El Paso clinic users both in life table analyses and hazard models that adjusted for user characteristics and contraceptive goals and experience. Only when the comparison was restricted to clinic users who were dispensed six or more pill packs when they last resupplied was continuation among clinic users comparable to that of the cross-border OTC users. Beyond source of contraception, the only other significant predictor of discontinuation was a woman’s report of how long she intended to use OCPs, suggesting that planned duration of use is an important piece of information clinicians should consider.

The location of the study in El Paso, Texas, afforded us the opportunity to compare the experience of users who accessed the pill over the counter in a setting where this option had been available for a considerable length of time, and was, in addition to family planning clinics, a regular source of OCPs for low-income women, especially those without private health insurance. However, a limitation of this natural experiment, in addition to convenience sampling, is that the increase in access provided by moving OCPs over-the-counter in the US would be greater than that now available to El Paso residents who have to cross the border in order to get to a pharmacy where a prescription is not required. On the other hand, it is possible that once OCPs were available without a prescription in the U.S., the price might be set higher than that prevailing in Mexican pharmacies. Also, while detailed baseline and follow-up questionnaires permitted us to capture extensive data on the number of pill packs dispensed to clinic users, how long a woman planned on using the pill, whether she had previously experienced side effects, and the month and year of discontinuation, responses to these questions may have been subject to recall failure and social desirability bias (22). Still, any such bias would likely affect both groups equally.

Cross-border OTC users and clinic users differed on a number of characteristics, some of which could be expected to be associated with OCP continuation. Duration of use, age, marital status, insurance, and parity are among the variables that have been found to be associated with OCP discontinuation in previous studies (1, 23-25). However, our concern that the women who elected to get their OCPs in Mexico might have been more motivated to continue using the pill than El Paso clinic users was alleviated by the similarity between the two groups of women in their reports of how long they planned to use the pill. Indeed, on this basis, clinic users would be expected to have lower rates of discontinuation than cross-border OTC users. One difference between the women that could explain higher discontinuation among clinic users is the greater proportion of women reporting that they had experienced side effects. Nonetheless, after adjusting for prospective measures of both planned use and side effects, the hazard ratios still showed significantly lower discontinuation for method-related reasons for cross-border OTC users.

While we cannot rule out the possibility that the lower discontinuation rate of clinic users receiving six or more packs was due to indication bias, this bias seems unlikely to have played an important role. In theory, clinicians could have access to additional information regarding a woman’s motivation, knowledge of how to take OCPs correctly, and previous experience with this method (18), but we did not find any significant association between women’s reports of how long they plan to take the pill and the number of packs dispensed to clinic users, suggesting that clinicians either do not ask women about their plans or are unwilling to trust what women tell them about planned duration of use. Moreover, the size of the effect is consistent with the findings from a recent clinical trial (7). It is also consistent with the findings from a large observational study using California claims data (6), but our observational study includes a number of controls that were not available in the California study.

These results provide evidence suggesting that removing the prescription requirement for OCPs, in addition to making it easier for women to initiate OCP use, would not have an adverse impact on continuation and might well improve it. Moreover, either by way of dispensing a larger number of pill packs or by way of over-the-counter provision, access appears to have a greater impact on continuation than side effects, consistent with other prospective studies (26). The large effect of the number of pill packs dispensed to clinic users in the final model suggests that the need for repeated clinic visits for resupply is an impediment to continuation. Also, while estimated continuation rates for cross-border OTC users and clinic users receiving six or more packs were similar, this should not be taken to imply that increasing the number of pill packs is a substitute for changing the prescription status of OCPs. Both would likely expand access but only moving OCPs over-the-counter would leave the need for clinic or doctor’s visits up to women, and provide the user with the possibility of sending someone else to pick up her OCPs for her (11).

Given the parallel findings from an RCT and a large observational study (6, 7), increasing the number of packs dispensed at clinics and pharmacies would clearly be an important step to increase the convenience of OCP use. While this would not require Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, it would require changes on both the part of providers and insurances. For example, some state Medicaid programs limit birth control to 30- or 90-day supplies (27), as do many private insurances. The only potential down-side of providing more pill packs is product wastage if a significant number of packs are not used.

Switching an OCP product over-the-counter would require FDA approval, and would involve considerations of OTC use beyond continuation. Future analyses from the Border Contraceptive Access Study will report on the differences between cross-border OTC and clinic users with respect to the prevalence of contraindications and use of preventive screening services. As part of an OTC switch application, the FDA would require an actual use study, which would provide additional evidence concerning the impact of over-the-counter access on OCP effectiveness that would complement our results from this natural experiment drawn from the border setting of El Paso, Texas.

Acknowledgements

Funded by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD047816).

The authors thank Sandra G. García, Leticia Fernández, and the late Charlotte Ellertson for contributing to the design of the project and helping to write the original proposal, Victor Talavera for project management, and Kari White for analysis and database management.

Footnotes

Conference Presentations

Presented at Reproductive Health 2010, Atlanta, GA, September 23, 2010. Preliminary versions were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, May 2, 2009 and at the XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference, Marrakech, Morocco, October 1, 2009.

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joseph E. Potter, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station G1800, Austin, TX 78712.

Sarah McKinnon, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Kristine Hopkins, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Jon Amastae, Department of Languages and Linguistics, University of Texas at El Paso.

Michele G. Shedlin, College of Nursing, New York University.

Daniel A. Powers, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Daniel Grossman, Ibis Reproductive Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaughan B, Trussell J, Kost K, Singh S, Jones R. Discontinuation and resumption of contraceptive use: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008 Oct;78:271–83. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter L. Oral contraceptive compliance and its role in the effectiveness of the method. In: Cramer J, Spilker B, editors. Patient compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. Raven Press; New York: 1991. pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg MJ, Burnhill MS, Waugh MS, Grimes DA, Hillard PJA. Compliance and Oral Contraceptives: A Review. Contraception. 1995;52:137–41. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(95)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: a prospective evaluation of frequency and reasons. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Sep;179:577–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. US women’s one-year contraceptive use patterns, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007 Mar;39:48–55. doi: 10.1363/3904807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster DG, Parvataneni R, de Bocanegra HT, Lewis C, Bradsberry M, Darney P. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed, method continuation, and costs. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Nov;10:1107–14. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000239122.98508.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connell K, Roca C, Westhoff CL. The impact of pack supply on oral contraceptive continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2010 Aug;82:185–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trussell J, Stewart F, Potts M, Guest F, Ellertson C. Should oral contraceptives be available without prescription? Am J Public Health. 1993 Aug;83:1094–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landau SC, Tapias MP, McGhee BT. Birth control within reach: a national survey on women’s attitudes toward and interest in pharmacy access to hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2006 Dec;74:463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, Amastae J, Potter JE. Perceptions of the safety of oral contraceptives among a predominately Latina population in Texas. Contraception. 2010;81:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter JE, White K, Hopkins K, Amastae J, Grossman D. Clinic versus over-the-counter access to oral contraception: choices women make in El Paso, Texas. AJPH. 2010;100:1130–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastida E, Brown HS, Pagan JA. Persistent Disparities in the Use of Health Care Along the US-Mexico Border: An Ecological Perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 Nov;98:1987–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amastae J, Fernandez L. Transborder use of medical services among Mexican American students in a U.S. border university. Journal of Borderland Studies. 2006;21:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez L, Howard C, Amastae J. Education, race/ethnicity and out-migration from a border city. Population Research and Policy Review. 2007 Feb;26:103–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter J, Moore A, Byrd T. Cross-Border Procurement of Contraception: Estimates from a Postpartum Survey in El Paso, Texas. Contraception. 2003;67:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westhoff C, Heartwell S, Edwards S, Zieman M, Cushman L, Robilotto C, et al. Initiation of oral contraceptives using a quick start compared with a conventional start: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;109:1270–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000264550.41242.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias - Effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA. 2007 Jan;297:278–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efron B. The Efficiency of Cox’s Likelihood for Censored Data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:557–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenfeld D. Partial Residuals for the Proportional Hazards Regression Model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart GS, Grimes DA. Social desirability bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception. 2009;80:108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost JJ, Darroch JE. Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008 Jun;40:94–104. doi: 10.1363/4009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. Factors associated with contraceptive use and nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007 Jun;39:90–9. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trussell J, Vaughan B. Contraceptive Failure, Method-Related Discontinuation And Resumption of Use: Results from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999 Mar-Apr;31:64–72. 93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westhoff CL, Heartwell S, Edwards S, Zieman M, Stuart G, Cwiak C, et al. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: do side effects matter? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007 Apr;196:6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley JS, Ashner D, Elam L. State Medicaid: Outpatient Prescription Drug Policies: Findings from a National Survey, 2005 Update. The Kaiser Family Foundation; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]