Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-stimulated nuclear factor (NF) κB activation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Phosphorylation of NFκB inhibitory protein (IκB) leading to its degradation and NFκB activation, is regulated by the multimeric IκB kinase complex, including IKKα and IKKβ. We recently reported that 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) inhibits TNFα-regulated IκB degradation and NFκB activation. To determine the mechanism of 5-ASA inhibition of IκB degradation, we studied young adult mouse colon (YAMC) cells by immunodetection and in vitro kinase assays. We show 5-ASA inhibits TNFα-stimulated phosphorylation of IκBα in intact YAMC cells. Phosphorylation of a glutathione S-transferase-IκBα fusion protein by cellular extracts or immunoprecipitated IKKα isolated from cells treated with TNFα is inhibited by 5-ASA. Recombinant IKKα and IKKβ autophosphorylation and their phosphorylation of glutathione S-transferase-IκBα are inhibited by 5-ASA. However, IKKα serine phosphorylation by its upstream kinase in either intact cells or cellular extracts is not blocked by 5-ASA. Surprisingly, immunodepletion of cellular extracts suggests IKKα is predominantly responsible for IκBα phosphorylation in intestinal epithelial cells. In summary, 5-ASA inhibits TNFα-stimulated IKKα kinase activity toward IκBα in intestinal epithelial cells. These findings suggest a novel role for 5-ASA in the management of IBD by disrupting TNFα activation of NFκB.

Aminosalicylic acid is an important antiinflammatory agent used for management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 Sulfasalazine was introduced as an azo bond compound between 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and sulfapyridine for use in arthritis (1). It was not an effective therapeutic agent for arthritis, however it proved to be useful for IBD. The benefit has been principally attributed to the bacterial azo-cleavage product 5-ASA and not the sulfapyridine moiety (2). It has been suggested that the therapeutic value of 5-ASA and other amino salicylates is due to the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis (3). However, cumulative evidence suggests additional mechanisms are involved. For example, aspirin, a more effective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase activity, has not been therapeutic for IBD. Intestinal mucosal 5-ASA concentrations in the millimolar range correlate with a therapeutic effect (4). We, and others have recently reported that amino salicylates can inhibit signal transduction leading to nuclear factor (NF) κB activation (5, 6). Sodium salicylate and aspirin have also been found to inhibit NFκB activation in murine T and B cells (7). Interestingly, one group recently reported sulfasalazine to be effective at inhibiting NFκB activation by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α (8). However, it is known that sulfasalazine disrupts TNFα from its receptor (9).

TNFα-regulated transcriptional activation of NFκB plays a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD (10–12). Increased NFκB activation has been shown in inflamed mucosal epithelial cells, but not in adjacent uninvolved mucosa, in patients with IBD (13). Treatment with 5-ASA decreases TNFα levels in patients with IBD (14). The expression of cytokines, including TNFα and interferon (IFN) γ, is inhibited in colonic lymphocytes by 5-ASA (14).

Under normal conditions, NFκB is held in an inactive state in a cytoplasmic complex with its inhibitory protein (IκB). Proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, result in phosphorylation of IκBα on serine 32 and 36 (15), targeting IκB for ubiquitination and proteosome-mediated degradation. Thus, NFκB is released for nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activation (16, 17). Once in the nucleus, NFκB binds to cis elements enhancing transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules (18). Recently, additional novel mechanisms of activating NFκB by both IκB-dependent and IκB-independent pathways have been described (19–21).

TNFα-stimulated IκB phosphorylation is mediated by several intermediate signaling proteins. The multimeric protein kinase complex that directly phosphorylates IκB in response to TNFα signaling contains two catalytic subunits, IκB kinase (IKK) α and β (22, 23). Both recombinant and immunoisolated IKKα and IKKβ can stimulate IκB phosphorylation (15, 23). IKKα and IKKβ have been found to form both homodimers and heterodimers, and both isoforms can phosphorylate IκB bound to NFκB more efficiently than free IκB (24). Overexpression of dominant-negative mutants of either IKKα or IKKβ block TNFα-induced NFκB activation (25, 26). Thus, both IKKα and IKKβ contribute to the activity of the IKK complex and are able to induce IκB phosphorylation, degradation, and NFκB activation. Interestingly, IKK null mouse studies show specificity in cytokine signal transduction and limb development for IKKβ and IKKα, respectively (27, 28). The IKK complex also associates with upstream kinases, NFκB-inducing kinase (NIK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase-1 (MEKK1). Both NIK and MEKK1 are able to phosphorylate IKKα and IKKβ leading to their activation (29, 30). Recently, NIK was shown to preferentially activate IKKα by phosphorylation on serine-176 (31), whereas MEKK1 appears to regulate IKKβ phosphorylation (32).

In this study, we compared salicylate compounds for their activity against TNFα-stimulated IκB phosphorylation and degradation in intestinal epithelial cells. Our findings indicate that 5-ASA inhibits TNFα-stimulated IκB phosphorylation and degradation by directly inhibiting IKKα activity toward IκBα in intact intestinal cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Young adult mouse colon (YAMC) cells (gift of Robert Whitehead, Ludwig Institute, Melbourne, Australia), a conditionally immortalized murine colon cell line isolated from the H-2kb-tsA58 mouse expressing a heat-labile simian virus 40 large T antigen with an IFN-γ-inducible promoter, were grown on culture dishes as previously reported (33, 34). Briefly, cells were maintained in culture under permissive conditions at 33 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Confluent cell monolayers were serum-starved (0.5% fetal bovine serum) and IFN-γ-deprived under nonpermissive conditions at 37 °C for 24 h prior to all experiments. HeLa cells (gift of Jeff Holt, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, as detailed elsewhere (35). Confluent monolayers were serum-starved for 24 h prior to study.

Experimental Protocols

Cells were treated with murine TNFα (Pepro Tech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) for indicated times, or pretreated with 5-ASA, 4-aminosalicylic acid (4-ASA), aspirin, salicylic acid, or sulfasalazine for 30 min followed by TNFα. All inhibitors were from Sigma. The medium containing inhibitors was adjusted to pH 6.65. Butyric acid and mannitol were used as controls for pH and molarity, respectively. All experiments using 5-ASA were protected from light exposure. Cell monolayers were washed twice on an ice bath with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then scraped into cell lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mM orthovanadate, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, with leupeptin (10 μg/ml), aprotinin (10 μg/ml), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (18 μg/ml), and 1% Triton X-100). The scraped suspensions were centrifuged (14,000 × g, 10 min) at 4 °C, and the protein content was determined using DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of cellular lysate protein were separated by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-IκBα (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) or anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation of IKKα

Cells were prepared as above and then treated with murine TNFα in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Cellular lysates were prepared as above with the following modifications. One hundred micrograms of protein supernatant was precleared with 10% (v/v) Staphylococcus aureus cell suspension (Sigma) for 1 h at 4 °C. The suspension was centrifuged (14,000 × g, 1 min). The supernatant was incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-IKKα antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with 10% (v/v) S. aureus cell suspension overnight at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitate was recovered by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 1 min) and washed with ice-cold cell lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl. The immunoprecipitate was solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer (36) for Western blot analysis with anti-phosphoserine (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA), anti-IKKα, or anti-IKKβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. The immunoprecipitate and supernatants were also used for in vitro kinase assays as detailed below.

Western Blot Analysis

After SDS-PAGE, protein transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), was accomplished by semidry technique (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked overnight in a solution of 5% nonfat, dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween (TBS-T). Before immunoblotting, membranes were washed twice in TBS-T. Western blotting was performed using anti-phospho-IκBα antibody (1:3000), anti-IκBα antibody (1:3000), anti-IKKα antibody (1:4000), anti-IKKβ antibody (1:4000), or anti-phosphoserine antibody (1:500) for 2 h at room temperature in TBS-T. Next, membranes were washed three times in TBS-T for 10 min each. For Western blot analysis with anti-Flag, membranes were blocked in TBS-T containing 5% milk at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing three times in TBS-T for 5 min each, blotting was conducted using mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2 antibody (Sigma) at 1:750 dilution in TBS-T for 30 min at 22 °C. Secondary antibody incubations were carried out using anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:10,000), or anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:5000), in TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. After three 10-min washes with TBS-T, proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Where indicated, comparison between intensity of bands was detected by densitometric analysis using Gel-Pro Analyzer software for Macintosh (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD) and indicated as -fold change.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Recombinant Flag-IKKα or Flag-IKKβ (gift of Tularik, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) was resuspended in kinase buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM p-nitrophenol phosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM EDTA, 100 nM ATP with leupeptin (10 μg/ml), aprotinin (10 μg/ml), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (18 μg/ml)) and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in the presence or absence of various concentrations of inhibitors. The inhibitors were added to the reaction buffer for 30 min at 4 °C before the kinase reactions were initiated by incubation at 37 °C (6). Flag-IKKα or Flag-IKKβ was solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer (36) and separated by SDS-PAGE with phosphorylation detected by autoradiography. Western blot analysis with anti-Flag was used to verify equal protein loading. In vitro GST-IκBα phosphorylation assay was performed by incubating cellular lysates or autophosphorylated Flag-IKKα or Flag-IKKβ, as prepared above, in kinase buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40. Lysates were isolated from YAMC cells treated with either murine TNFα or murine EGF (gift of Stanley Cohen, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for various times. GST-IκBα fusion protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) conjugated to Glutathione Sepharose-4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added to the reaction mixture with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP at 37 °C for 30 min in the presence or absence of various concentrations of inhibitors. In some experiments, immunoprecipitated IKKα or the supernatant from the immunoprecipitation was used in the in vitro kinase assay with GST-IκBα. Inhibitors were added to the reaction buffer for 30 min at 4 °C before the kinase assays. GST-IκBα conjugated to beads or GST-IκBα was recovered by centrifugation and separated by SDS-PAGE for detection of phosphorylation by autoradiography. Western blot analysis with anti-IκBα or anti-Flag was used to verify equal protein loading.

RESULTS

Salicylates Inhibit TNFα-stimulated IκBα Phosphorylation and Degradation

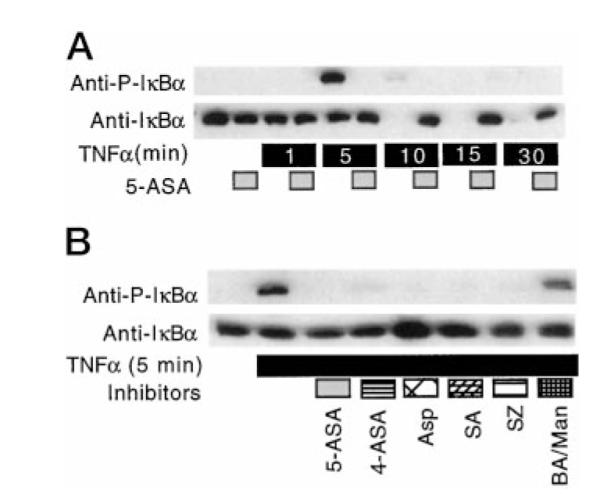

Because we have shown that TNFα-induced NFκB activation and IκB degradation are blocked by 5-ASA, we asked whether IκBα phosphorylation is also inhibited. YAMC cells were incubated with salicylates prior to the addition of TNFα for various times. To control for pH and molarity of the inhibitors, butyric acid (20 mM, pH 6.65) and mannitol (200 mM) were added to cells as indicated. Triton-soluble cellular lysates were studied by Western blot analysis with anti-IκBα and anti-phospho-IκBα antibodies as described under “Experimental Procedures.” TNFα treatment of YAMC cells increased IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, which was blocked by 5-ASA (Fig. 1A). Other salicylates show similar inhibitory effects on TNFα-induced IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). However, the combination of butyric acid and mannitol had no effect on IκBα phosphorylation. These results indicate the effect of 5-ASA is to inhibit NFκB activation upstream of IκB serine phosphorylation.

Fig. 1. Salicylates inhibit TNFα-stimulated IκBα phosphorylation and degradation.

YAMC cells were cultured with 5-ASA (50 mM) for 30 min followed by TNFα (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Cellular lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis with anti-phospho (P)-IκBα or anti-IκBα (A). Cells were cultured with 4-aminosalicylic acid (4-ASA, 50 mM), aspirin (5 mM), salicylic acid (5 mM), sulfasalazine (5 mM), or butyric acid (20 mM, pH 6.65) and mannitol (200 mM) for 30 min followed by TNFα (100 ng/ml) for 5 min (B). Twenty micrograms of cellular lysate protein was separated by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Each experiment was performed on at least three separate occasions. Shown in this and subsequent figures are representative images. ASA, aminosalicylic acid; Asp, aspirin; SA, salicylic acid; SZ, sulfasalazine; BA, butyric acid; Man, mannitol.

Salicylates Inhibit Kinase Activity toward IκBα in Vitro

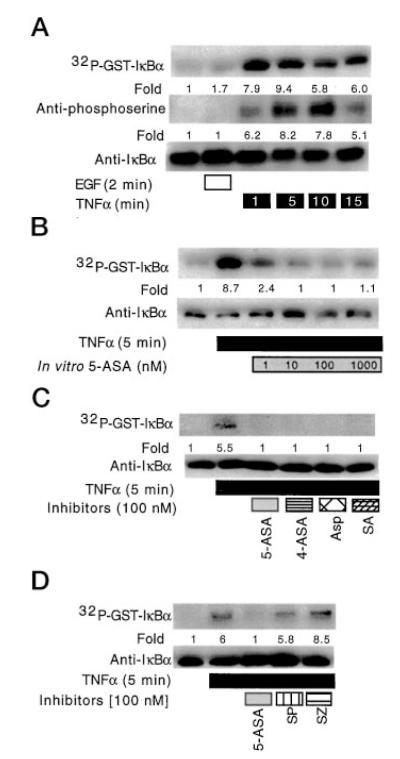

To determine whether the 5-ASA inhibitory effects on TNFα-stimulated IκBα phosphorylation extend to intracellular kinase activity, we established an in vitro kinase assay using GST-IκBα. Cellular lysates were prepared in kinase buffer from untreated, EGF-treated, or TNFα-treated YAMC cells for various times. Equal amounts of cellular lysate were incubated with GST-IκBα and [γ-32P]ATP at 37 °C for 30 min in the presence or absence of salicylates at various concentrations. The GST-IκBα conjugated to beads was precipitated, solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer, and separated by SDS-PAGE with phosphorylation detected by autoradiography. Equal loading was verified by Western blot analysis with anti-IκBα. Cellular lysates isolated from cells treated with TNFα, but not EGF, enhanced kinase activity toward GST-IκBα detected by [32P]ATP labeling and Western blot analysis with anti-phosphoserine compared with non-treated cellular lysates (Fig. 2A). Salicylates added to the cellular lysates show a concentration-dependent inhibition of GST-IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). At equimolar concentrations, 5-ASA, 4-ASA, aspirin, and salicylic acid show similar inhibitory effects on GST-IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). However, when directly compared with 5-ASA, neither the parent compound sulfasalazine nor the sulfapyridine product showed inhibition of this kinase activity toward GST-IκBα (Fig. 2D). In fact, sulfasalazine increases the in vitro kinase activity toward IκBα in cellular lysates. Taken together, these findings indicate various salicylates inhibit the kinase activity of TNFα-treated intestinal cell lysates toward IκBα.

Fig. 2. Salicylates inhibit kinase activity toward IκBα in vitro.

In vitro kinase assays were performed by incubating 0.5 μg of GST-IκBα conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose-4B as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Lysates were prepared in kinase buffer from untreated, EGF-treated (10 ng/ml), or TNFα-treated (100 ng/ml) YAMC cells (A). The kinase assay was initiated by incubation of lysates with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 5-ASA at various concentrations (B) or 100 nM other inhibitors (C), as indicated. For comparison lysates were incubated with sulfapyridine, 5-ASA, or the parent compound sulfasalazine at 100 nM (D). GST-IκBα conjugated to beads was precipitated and separated by SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated GST-IκBα was detected by autoradiography, or precipitates were studied by Western blot analysis with anti-phosphoserine or anti-IκBα antibodies, as indicated. The band densities were detected as described under Experimental Procedures” and indicated as -fold change compared with control in this and subsequent figures. SP, sulfapyridine; SZ, sulfasalazine.

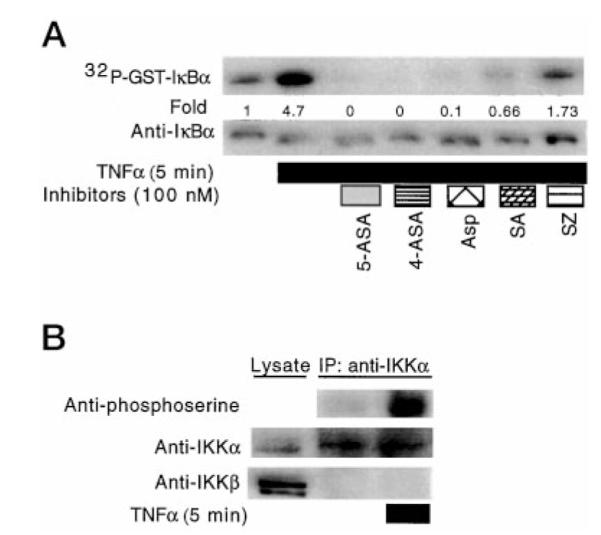

Salicylates Inhibit IKKα Phosphorylation of IκBα in Vitro

To determine the role of IKKα in GST-IκBα phosphorylation, we immunoisolated IKKα from lysates of YAMC cells treated with TNFα for in vitro kinase assays. Immunoprecipitated IKKα, GST-IκBα, and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated in kinase buffer, at 37 °C for 30 min, in the presence or absence of 5-ASA or other salicylate compounds. Fig. 3A shows 5-ASA, 4-ASA, and other salicylates inhibit phosphorylation of GST-IκBα by native IKKα isolated from TNFα-treated YAMC cellular lysates. To further characterize the regulation of kinase activity by 5-ASA, we immunoprecipitated IKKα or prepared cellular lysates for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis with antibodies against phosphoserine, IKKα, or IKKβ. TNFα treatment increased the phosphoserine content of IKKα in intact YAMC cells (Fig. 3B). Surprisingly, IKKβ was not detected in immunoprecipitates of IKKα from either TNFα-treated or untreated cells, even though it was clearly present in the cellular lysates.

Fig. 3. Salicylates inhibit IKKα phosphorylation of IκBα in vitro.

In vitro kinase assays were performed by incubating immunoprecipitated IKKα and GST-IκBα with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of 100 nM of the indicated salicylates as described under “Experimental Procedures.” GST-IκBα was prepared for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis with anti-IκBα. Phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography (A). Immunoprecipitated IKKα from cells treated with TNFα (100 ng/ml) or cellular lysate was separated by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis with antibodies to phosphoserine, IKKα, or IKKβ, as indicated (B).

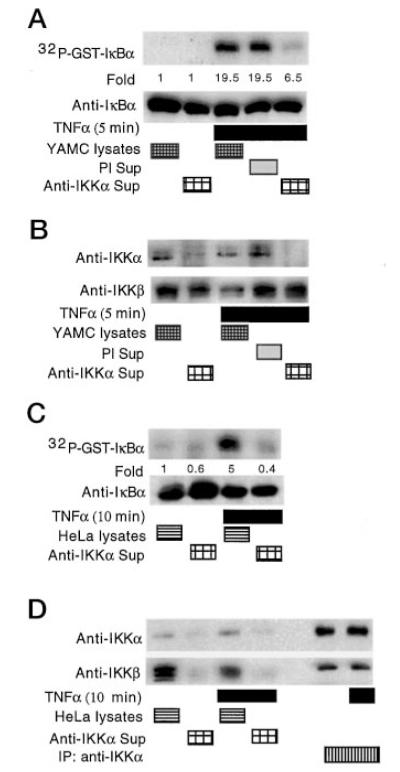

Because the role of IKK isozymes in regulating TNFα-stimulated IκB phosphorylation remains controversial, we tested the role of IKKα in IκBα phosphorylation using an immunodepletion assay. Supernatants recovered from the immunoprecipitation of IKKα were incubated with GST-IκBα for in vitro kinase assays. Immunodepletion of IKKα decreased by two-thirds the level of GST-IκBα phosphorylation compared with total cellular lysates isolated from TNFα-treated YAMC cells (Fig. 4A). However, no decrease in kinase activity was detected in supernatants precipitated with pre-immune serum. Surprisingly, the level of IKKβ present in the supernatants from precipitating IKKα were the same as total cellular lysates or preimmune immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4B). Because IKKβ has been shown to regulate TNFα-stimulated IκBα phosphorylation in HeLa cells (37), we performed an immunodepletion assay using these cells to address this apparent discrepancy and as a positive control for IKKα-IKKβ co-precipitation in our immunodepletion assay. Similar to our findings in YAMC cells, antibody to IKKα depleted IκB kinase activity from HeLa cell lysates (Fig. 4C). By contrast, however, IKKβ was depleted from the HeLa cell lysate by precipitation with anti-IKKα (compare Fig. 4D with Figs. 4B and 3B). These findings suggest IKKα is the predominant IκB kinase activated by TNFα in intestinal cells.

Fig. 4. Immunodepletion of IKKα from cellular lysates decreases IκBα phosphorylation in vitro.

Kinase assays were performed in vitro by incubating lysates from untreated or TNFα-treated (100 ng/ml) YAMC cells, or the supernatants (Sup) remaining after immunoprecipitation with either anti-IKKα or preimmune (PI) serum. GST-IκBα was added to the kinase reaction mixture with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP as before for detection of phosphorylation by autoradiography or IκBα by Western blot analysis (A). Cellular lysates or supernatants from the indicated immunoprecipitations were separated by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis with antibodies to either IKKα or IKKβ, as indicated (B). Kinase assays were performed using lysates or supernatants of immunoprecipitates from HeLa cells as above (C). HeLa cells were treated with TNFα and lysates, supernatants, or immunoprecipitates of IKKα studied for IKKα and IKKβ by Western blot analysis (D). Lane 5 was loaded with sample buffer only, to prevent any cross-contamination between immunoprecipitates and cellular lysates.

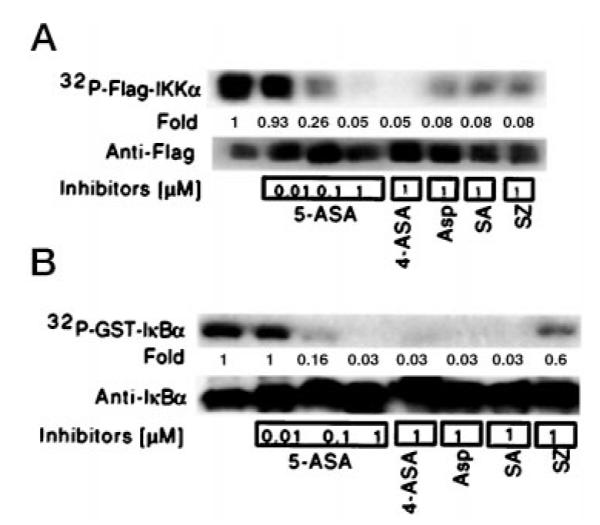

Salicylates Inhibit IKKα Autophosphorylation and Phosphorylation of GST-IκBα

To address the inhibitory effects of 5-ASA on IKKα autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of GST-IκBα, in vitro kinase assays were performed using recombinant Flag-tagged-IKKα alone or with GST-IκBα in the presence or absence of 5-ASA and other salicylates. All salicylates studied inhibited both IKKα autophosphorylation (Fig. 5A) and phosphorylation of GST-IκBα by recombinant IKKα (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Salicylates inhibit IKKα autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of IκBα.

In vitro kinase assays were performed by incubating recombinant Flag-tagged-IKKα and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of various salicylates at the indicated concentrations (A). Phosphorylated IKKα was detected by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Western blot analysis with anti-Flag was used to verify equal protein loading. Autophosphorylated recombinant Flag-tagged IKKα was incubated with GST-IκBα and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of the indicated salicylates (B). GST-IκBα conjugated to beads was recovered, and phosphorylation and gel loading were detected as before.

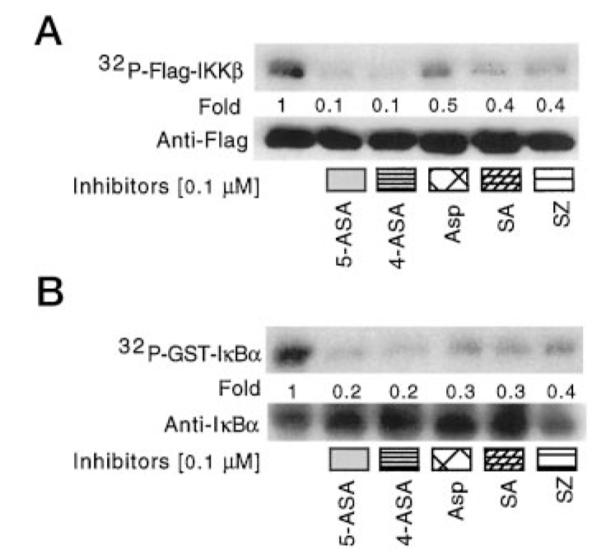

Salicylates Inhibit IKKβ Autophosphorylation and Phosphorylation of GST-IκBα

Because it has recently been shown that aspirin and salicylic acid inhibit IKKβ autophosphorylation (6) and since we only recovered IKKα in our intestinal cell immunoprecipitates phosphorylating IκBα, we asked if 5-ASA and the other salicylates studied inhibit IKKβ autophosphorylation or phosphorylation of IκBα. Recombinant Flag-tagged IKKβ was incubated in phosphorylation buffer with [γ-32P]ATP and various salicylates, then separated by SDS-PAGE for detection by autoradiography or Western blot analysis with anti-Flag or anti-IκBα antibodies. Both autophosphorylation of IKKβ and IκBα phosphorylation by IKKβ were inhibited by the salicylates (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Salicylates inhibit IKKβ autophosphorylation and IκBα phosphorylation in vitro.

Recombinant Flag-tagged IKKβ was incubated alone (A) or with GST-IκBα (B), as in Fig. 5, with the indicated concentration of salicylate. Recombinant proteins were prepared as before for detection of phosphorylation by autoradiography or by Western blot analysis with anti-Flag (for IKKβ) or anti-IκBα.

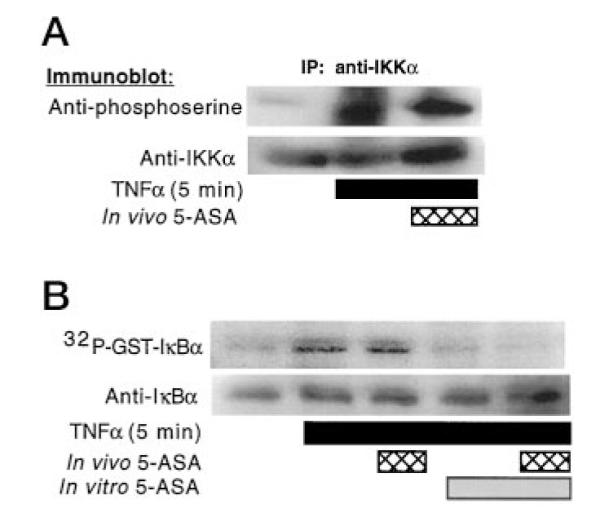

5-ASA Does Not Inhibit TNFα-stimulated Kinase Activity toward IKK in Intact YAMC Cells

To determine whether 5-ASA inhibits generalized kinase activity leading to phosphorylation of IKKα, YAMC cells were treated with TNFα in the presence or absence of 5-ASA. Triton-soluble lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-IKKα for Western blot analysis with anti-phosphoserine. Treatment of YAMC cells does not inhibit TNFα-stimulated IKKα serine phosphorylation (Fig. 7A), which indicates that 5-ASA inhibition in the NFκB pathway is downstream of phosphorylation of IKKα. In addition, this shows specificity of kinase inhibition. To verify that this serine-phosphorylated IKKα isolated from YAMC cells had increased kinase activity, immunoprecipitated IKKα was separated for use in a kinase assay. Immunoisolated IKKα from YAMC cells treated with TNFα in the presence of 5-ASA was divided for an in vitro kinase assay with GST-IκBα in the presence or absence of 5-ASA. Serine-phosphorylated IKKα recovered from YAMC cells treated with TNFα in the presence of 5-ASA still phosphorylated IκBα (Fig. 7B). However, this phosphorylation was inhibited by the addition of 5-ASA to the kinase assays. These findings clearly indicate that the specific inhibitory effect of 5-ASA in this TNFα signal transduction pathway is at the level of the IκB kinase.

Fig. 7. 5-ASA does not inhibit TNFα-stimulated kinase activity toward IKKα in intact YAMC cells.

YAMC cells were treated with TNFα (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of 5-ASA (50 mM). Triton-soluble lysates were prepared for immunoprecipitation with anti-IKKα for Western blot analysis with anti-phosphoserine or anti-IKKα (A). Cells were treated with TNFα in the presence (in vivo) or absence of 5-ASA (50 mM). IKKα was immunoprecipitated for an in vitro kinase assay with GST-IκBα as in Fig. 3. Where indicated, 5-ASA (100 nM) was added in vitro. Phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography and IκBα identified by Western blot analysis, as in Fig. 2 (B).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that 5-ASA and other salicylates specifically inhibit TNFα-induced IκB kinase activity in intact intestinal epithelial cells. Whereas in vitro kinase assays show these compounds block IκBα phosphorylation by either IKKα or IKKβ, immunodepletion of IKKα from lysates of TNFα-treated cells shows a 66% reduction in kinase activity toward IκB. Consistent with these findings, 5-ASA does not inhibit IKKα serine phosphorylation by its upstream kinases in intact cells. Thus, inhibition of IKKα activity toward IκBα may function as an important therapeutic mechanism for 5-ASA in inflammatory bowel disease by blocking TNFα-stimulated IκBα degradation and NFκB activation in intestinal epithelial cells.

TNFα has been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD in humans, as well as a number of animal models (38, 39). It has been proposed that the effects of TNFα are mediated via inflammatory cells present in the submucosa of the intestinal epithelial monolayer. However, little attention has been directed toward the effects of TNFα on the intestinal epithelial cells. A recent report showed an increased nuclear localization of NFκB in the epithelial cells at sites of mucosal inflammation (13). These findings suggest an effect of increased mucosal TNFα levels in IBD may be to stimulate NFκB-induced cytokine production by intestinal epithelial cells. Similar effects have been proposed to support roles for TNFα in the pathogenesis of other chronic inflammatory conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis, arthritis, chronic hepatitis, and psoriasis (40–43).

Although both IKKα and IKKβ directly phosphorylate IκBα, these display distinct modes of regulation when overexpressed in mammalian cells. Overexpression of IKKβ leads to constitutive phosphorylation of IκB, whereas overexpression of IKKα does not phosphorylate IκB unless cells are stimulated by TNFα (22, 25). However, in HeLa cells IKKβ, not IKKα, is the target of TNFα signal transduction and is essential for IKK activation (37). On the basis of our findings combined with those of Gaynor and colleagues on salicylates (6), we suggest that both IKKα and IKKβ are targets for 5-ASA inhibition of NFκB activation. In the present study, we find that 5-ASA inhibits phosphorylation of IκBα by either IKKα or IKKβ. In agreement with this observation, 5-ASA also inhibited autophosphorylation of either kinase. Interestingly, we observed inhibition of IκB phosphorylation in vitro by 5-ASA at picomolar concentrations compared with the reported micromolar concentrations required for aspirin inhibition of IKKβ (6). Because immunoprecipitating antibodies for mouse IKKβ are not readily available, we used an immunodepletion assay to assess the relative contributions of IKKα and IKKβ in TNFα-stimulated phosphorylation of IκBα. Our findings suggest that the majority of kinase activity is contributed by IKKα since immunodepletion of cellular extracts reduced most of the kinase activity toward IκBα. Even with prolonged exposure, no IKKβ was detected in these immunoprecipitates, despite readily detectable β form in the cellular lysates. Since our immunodepletion assay using HeLa cells showed both IKKα and IKKβ were precipitated by anti-IKKα antibody, it appears likely that the assay is sufficient to detect complex formation, if present, in intestinal cells. Definitive evidence regarding the absolute contribution of IKKα and IKKβ in TNFα signal transduction in intestinal cells requires further study. However, these findings indicate the relative contribution of IκB kinase isozyme activity toward IκB varies between cell types.

It is noteworthy that salicylates also deplete intracellular ATP concentrations (44). However, this seems unlikely to be the mechanism of 5-ASA inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation in intact cells. First, the TNFα-induced serine phosphorylation of IKKα occurs in these experiments despite 5-ASA in the media. Also, we have previously shown that 5-ASA does not inhibit EGF-induced mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphorylation (5). The findings in that report show 5-ASA also inhibits TNFα-stimulated MAP kinase (ERK1/ERK2 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase) phosphorylation. Together, these observations suggest either IKK is an upstream regulator of MAP kinase or, more likely, 5-ASA inhibits at least one other kinase such as Raf-1 or MEK-1.

Aspirin and salicylic acid were recently reported to inhibit IKKβ activity, but not IKKα activity, toward IκBα in Jurkat cells and in vitro using recombinant proteins (6). Somewhat at odds with that study, we found 5-ASA and other salicylates inhibit both IKKα and IKKβ autophosphorylation and their phosphorylation of IκBα. Based on our observation that picomolar concentrations of 5-ASA were sufficient to inhibit IκBα phosphorylation by either cellular lysates from TNFα-treated cells or immunoprecipitated IKKα, we propose that 5-ASA inhibits IKKα at clinically relevant concentrations. If NFκB inhibition is an important target for 5-ASA in IBD, it is likely that cellular permeability is the limiting factor requiring millimolar concentrations for therapeutic benefit. As such, the specific interaction of 5-ASA inhibiting IKKα kinase represents an area for further investigation. Potentially, development of more cell-permeable inhibitors of IKKα may prove useful in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

We have found 5-ASA inhibits TNFα-stimulated IKKα kinase activity toward IκBα consequently inhibiting NFκB activation in intestinal epithelial cells. Such action could disrupt critical signal transduction pathways necessary for production of inflammatory mediators in IBD. Although the clinical relevance of this effect remains to be shown, these findings suggest development of more cell-permeable 5-ASA-like agents may represent an important area for novel therapeutic development in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Rothe and Tularik Inc. for recombinant IKKα and IKKβ and Steve Hanks and Peter Dempsey for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK02212, T32 DK07673, and DK56008 and by a research grant from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; 4-ASA, 4-aminosalicylic acid; YAMC, young adult mouse colon; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α; GST, glutathione S-transferase; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IFN, interferon; NF, nuclear factor; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; TBS-T, Tris-buffered saline with Tween; MAP, mitogen-activated protein; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MEKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase; IKK, IκB kinase; NIK, NFκB-inducing kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinals RS. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;17:246–259. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(88)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan AKA, Piris J, Truelove SC. Lancet. 1977;2:892–898. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peskar BM, Dreyling KW, May B, Schaarschmidt K, Goebell H. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1987;32:51S–56S. doi: 10.1007/BF01312464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peppercorn M, Goldman P. Gastroenterology. 1973;64:240–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiser GC, Yan F, Polk DB. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:602–609. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin M-J, Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. Nature. 1998;396:77–80. doi: 10.1038/23948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp E, Ghosh S. Science. 1994;265:956–958. doi: 10.1126/science.8052854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl C, Liptay S, Adler G, Schmid RM. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1163–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanahan F, Niederlehner A, Carramanzana N, Anton P. Immunopharmacology. 1990;20:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(90)90037-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartor RB. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 1995;24:475–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Hampe J. Gut. 1998;42:477–484. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neurath MF, Becker C, Barbulescu K. Gut. 1998;43:856–860. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogler G, Brand K, Vogl D, Page S, Hofmeister R, Andus T, Knuechel R, Baeuerle PA, Scholmerich J, Gross V. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:357–369. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casellas F, Papo M, Guarner F, Antolin M, Armengol JR, Malagelada J-R. Clin. Sci. 1994;87:453–458. doi: 10.1042/cs0870453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella VJ, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thanos D, Maniatis T. Cell. 1995;80:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes PJ, Karin M. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Meco MT, Dominguez I, Sanz L, Dent P, Lozano J, Municio MM, Berra E, Hay RT, Sturgill TW, Moscat J. EMBO J. 1994;13:2842–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson L, Szabo C, Salzman AL. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:106–114. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Peet GW, Pullen SS, Schembri-King J, Warren TC, Marcu KB, Kehry MR, Barton R, Jakes S. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30736–30741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M. Science. 1998;281:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li JW, Young DB, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woronicz JD, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel DV. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y, Baud V, Delhase M, Zhang P, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. Science. 1999;284:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda K, Takeuchi O, Tsujimura T, Itami S, Adachi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Yoshikawa K, Terada N, Akira S. Science. 1999;284:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Q, Lee FS. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8355–8358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nemoto S, Didonato JA, Lin A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7336–7343. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling L, Cao Z, Goeddel DV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3792–3797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano H, Shindo M, Sakon S, Nishinaka S, Mihara M, Yagita H, Okumura K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3537–3542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaiser GC, Polk DB. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehead RH, VanEeden PE, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Jat PS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:587–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbott DW, Holt JT. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2732–2742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James SP. In: Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Bench to Bedside. Targan SR, Shanahan F, editors. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1994. pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiocchi C, Podolsky DK. In: Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Kirsner JB, Shorter RG, editors. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1995. pp. 252–280. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontoyiannis D, Pasparakis M, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F, Kollias G. Immunity. 1999;10:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larrea E, Garcia N, Qian C, Civiera MP, Prieto J. Hepatology. 1996:210–217. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan X, Hsueh W, Gonzalez-Crussi F. Am. J. Pathol. 1993;142:1858–1865. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ettehadi P, Greaves MW, Wallach D, Aderka D, Camp RDR. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994;96:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cronstein BN, Van de Stouwe M, Druska L, Levin RI, Weissmann G. Inflammation. 1994:323–325. doi: 10.1007/BF01534273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]