Abstract

More than two billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) lack adequate access to essential medicines. In this paper, we make strong public health, human rights and economic arguments for improving access to medicines in LMIC and discuss the different roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders, including national governments, the international community, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). We then establish a framework of pharmaceutical firms’ corporate responsibilities - the “must,” the “ought to,” and the “can” dimensions - and make recommendations for actionable business strategies for improving access to medicines. We discuss controversial topics, such as pharmaceutical profits and patents, with the goal of building consensus around facts and working towards a solution. We conclude that partnerships and collaboration among multiple stakeholders are urgently needed to improve equitable access to medicines in LMIC.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical Products, Health Policy, Health Financing, Health Systems

Introduction

More than two billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) lack adequate access to essential medicines [1]. The problem is complex and views of stakeholder responsibilities to solve it differ.

Increasingly, demands are being placed on the pharmaceutical industry to contribute to improving access to medicines for poor patients in developing countries [2,3]. A consensus on what constitutes an appropriate portfolio of corporate responsibilities for access to medicines – under conditions of failing states and market failure – is in the interest of the world’s poor and of corporations that want to be part of the solution for one of the most pressing social issues of our time.

In this paper, we provide public health, human rights and economic arguments for improving access to medicines and discuss the different roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders. We then establish a framework of pharmaceutical firms’ corporate responsibilities and make recommendations for actionable business strategies for improving access to medicines. We aim to contribute to constructive dialogue on the responsibilities of the pharmaceutical industry and its activities of good corporate practice. We conclude that partnerships and collaboration among multiple stakeholders are urgently needed to improve equitable access to medicines in LMICs.

Improving Access to Medicines – Health, Human Rights and Economic Rationales

WHO’s Director General, Dr. Margaret Chan, asserts that, “much of the ill health, disease, premature death and suffering we see on such a large scale is needless, as effective and affordable interventions are available for prevention and treatment [4].” Essential medicines are such interventions. Used properly, essential medicines and vaccines could save up to 10.5 million lives each year and reduce unnecessary suffering [5].

However, a third of the world’s population (up to 50 percent in parts of Asia and Africa) lack access to essential medicines [6].Average availability of generic medicines is only 38 percent in the public sector in LMIC [7]. Although private sector availability is higher – on average 64 percent – medicines in private pharmacies are often not affordable [7]. Consuming 25-65 percent of total public and private spending on health and 60-90 percent of household expenditure on health in developing countries, [8] medicines pose an enormous economic burden on health systems and households. Unfortunately, spending on medicines is often not cost-effective: almost half of all medicines are inappropriately prescribed, dispensed, or sold and patients do not adhere to about 50 percent of the medicines they receive [5,9].

There is a strong human rights argument for improving access to medicines [10]. Given that morbidity and mortality can be reduced by ‘good governance’ and spending resources according to actual needs, [11] and that medicines are vital for good health, there is a moral imperative for evidence-based policies and fair distribution of resources to improve access to medicines for the poor and vulnerable.

Similarly, there is a strong economic argument for improving access to medicines in LMICs. Today, about 2.5 billion people struggle to meet their basic needs [12]. In a vicious circle of poverty and illness, poverty is a both cause and an effect of poor health [13] and lack of access to medicines. Since health of their bodies and minds is often the only asset of poor people, access to medicines becomes particularly crucial for them.

Experts concur on the dismal state of access to medicines in LMICs. There is less agreement on sources of the problem, and while there are strong public health, human rights and economic arguments for improving access to medicines in LMIC, there is little consensus on who is responsible for action.

Improving Access to Medicines – Responsibilities of Stakeholders

Primary Duty Bearer

The Nation State, supported by the international community, bears the primary responsibility for ensuring that the right to health is respected, protected, and fulfilled [10].

WHO holds the “failure of health systems” [4] responsible for the “unacceptably low” health outcomes across much of the developing world. If low-income countries devoted 15 percent of their national budgets to health and added appropriate development assistance, they could finance adequate primary health care for the poor [14]. However, governments of many developing countries continue to spend most resources on sectors other than health and education [15,16] and scarce resources on health are wasted or misallocated, [17] often as a result of politics or corruption. Nevertheless, governments can facilitate significant progress toward improving access to medicines, even under budget constraints. For example, governments can abolish import tariffs, duties, and sales taxes on medicines, which contribute little to government budgets, unfairly tax the poor, and increase end-user prices of medicines in the public sector, sometimes by more than 80 percent [7,18].

Where capacity and efficacy in the public sector are still low, adopting strategies that place a greater workload on public institutions may prove detrimental [19]. Other actors must therefore assist to facilitate improvements.The international community, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the pharmaceutical industry share responsibilities for improving access to medicines. However, their contributions will only be as effective as national political and social constraints will allow [4].

Other Duty Bearers

International Community

International recommendations [11] and binding treaties [20] outline the roles of the international community in development assistance. In the Millennium Declaration, 147 heads of state and governments “recognize that, in addition to our separate responsibilities to our individual societies, we have a collective responsibility to uphold the principles of human dignity, equality and equity at the global level [21].”

Despite global commitment and unprecedented amounts of donor support, international efforts to improve medicines access leave much room for improvement. Programs that rely on donor funding are at risk when donor countries – themselves under financial pressure - fail to honor their commitments [22]. For decades, the international community has neglected programs for treatment of non-communicable diseases [23].International development assistance, which is often targeted at specific diseases rather than general health sector support [24], may actually hinder progress towards broader public health goals [25].

With respect to medicines access, international community efforts might benefit from coordination, a focus on strengthening health systems across vertical programs, and evaluation of the desired and undesired impacts of interventions [25].

Non-Governmental Organizations

Many NGOs play a vital role in development and in almost all aspects of health-related work for the poor. In contrast to governments (and pharmaceutical companies), NGOs tend to score highly among poor people on responsiveness and trust [26]. NGOs raise public awareness for health care issues affecting the poor, support policies that directly benefit the poor, supply medicines, and deliver care. NGOs have also been integral to promoting a rights-based approach to pharmaceutical policy [10] and pressing for more comprehensive corporate awareness of, and responsibility for, access to medicines [2].

However, like the international community, NGOs often focus on specific diseases, notably HIV/AIDS and little attention has been paid to access to medicines for other high-impact diseases and health system improvement [24].

In recognition of NGOs’ value, the Millennium Declaration recommends that greater opportunities be given to NGOs to contribute towards global health goals [21]. NGOs can play a critical role in campaigning for increased and better-coordinated resources for health care and promoting sustainable health systems, notably for chronic disease treatment. NGOs should continue to monitor, and hold accountable, country governments and pharmaceutical companies with respect to their responsibilities and commitments to improving access to medicines [10].

Pharmaceutical Industry

Finally, pharmaceutical companies, as the developers and manufacturers of medicines, play a key role in improving access to medicines. Millennium Development Goal 8 sets out the target for the international community “in co-operation with pharmaceutical companies, [to] provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries [27]. ”The corporate right-to-health obligation is laid out in the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “every individual and every organ of society… shall strive… to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and… to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance” [emphasis added] [28].

There is extensive debate on what the human rights focus should mean for pharmaceutical corporations, as organs of society.While some criticize today’s pharmaceutical business model for ensuring “maximum margins” by charging what the market can bear and by “defending patents unreservedly,” [2] investors and financial analysts who assess pharmaceutical companies expect nothing less [29].

The common good is best served when all actors in all social subsystems do their best in the area of their particular responsibility, without losing sight of the ties that bind them [30]. What is then the “particular responsibility” of the pharmaceutical industry, and how can corporations fulfill their social contract?

Responsibilities of the Pharmaceutical Industry – Evolving Paradigms

The role of a pharmaceutical company in a global economy is to research, develop and produce innovative medicines that improve quality of life, and it is their duty to do so in a profitable way. No other societal actor assumes this responsibility. A company can only realize sustained earnings if and when it uses its resources in a socially responsible, environmentally sustainable, and politically acceptable way. Given an increasing investor and consumer focus on corporate social responsibility, it is in the enlightened self-interest of a pharmaceutical company to be part of the solution to the access to medicines problem. Encouragingly, more companies participate in the bi-annual Access to Medicines Index which provides “pharmaceutical companies, investors, governments, academics, nongovernmental organizations and the general public with independent, impartial and reliable information on individual pharmaceutical companies’ efforts to improve global access to medicine [31].”

Responsibilities of the Pharmaceutical Industry – Controversies around Profits and Patents

Although critics argue for the weakening of intellectual property rights, patents should not be the focus of the access to medicines debate. Patents provide desirable incentives and are a precondition for successful research and development of innovative drugs and vaccines. Access to pharmaceutical innovations for poor patients requires an intelligent mix of public and private research and incentives. The challenge is to find innovative strategies for the responsible use of patents under conditions of market failure. Creative ideas are emerging [32], for example, for the development of new antibiotics [33] and medicines for neglected diseases [34].

Patents are not the reason for lack of access to essential medicines that are already developed. In 65 LMICs where four billion people live, patenting is rare for products on WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines: only 17 of the 319 products were patentable, and only in 1.4% of instances (300 out of 20,735 essential medicine-country combinations) were essential medicines patented, mostly in larger markets [35]. However, lack of patents does not guarantee that generic medicines are available [7] or acceptable [36] in LMICs, confirming that all stakeholders must do their parts to improve availability, quality, perception, and use of generic products.

Responsibilities of the Pharmaceutical Industry – A Framework

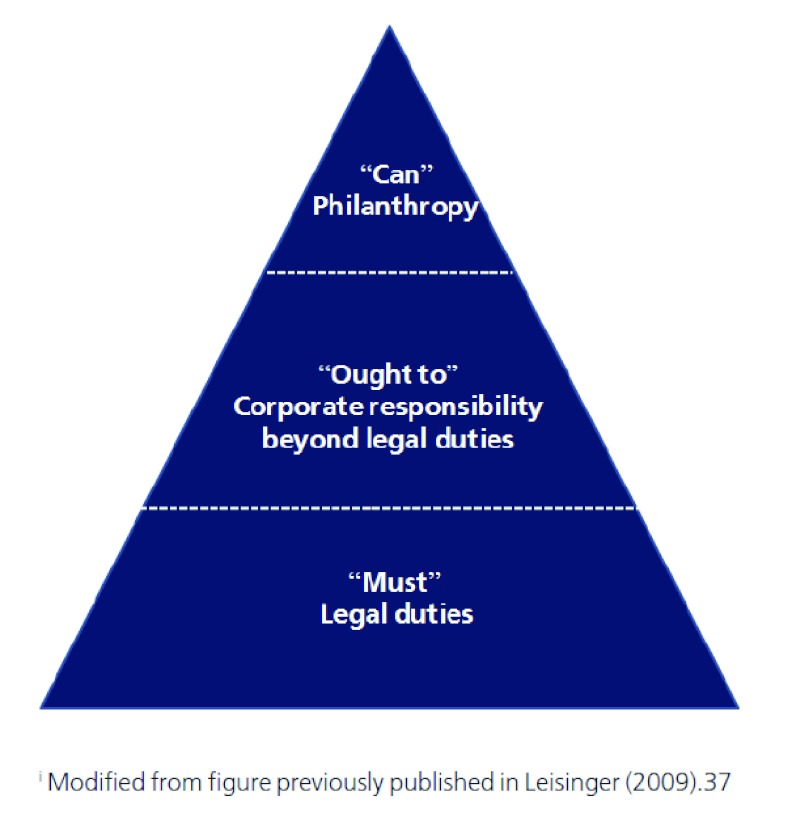

There are three levels of corporate responsibility: the “must,” the “ought to,” and the “can” dimensions [Figure 1] [37].Pharmaceutical firms “must” develop new medicines, make a profit, and comply with applicable laws and regulations. Voluntary corporate activities to improve access to medicines can be classified as either corporate responsibility (“ought to”) or philanthropy (“can”). Exactly which activities fall into each category may be debated, and given evolving paradigms, companies may increasingly consider access to medicines activities beyond legal duties consistent with business strategy.

Figure 1. The Hierarchy of Corporate Responsibilityi.

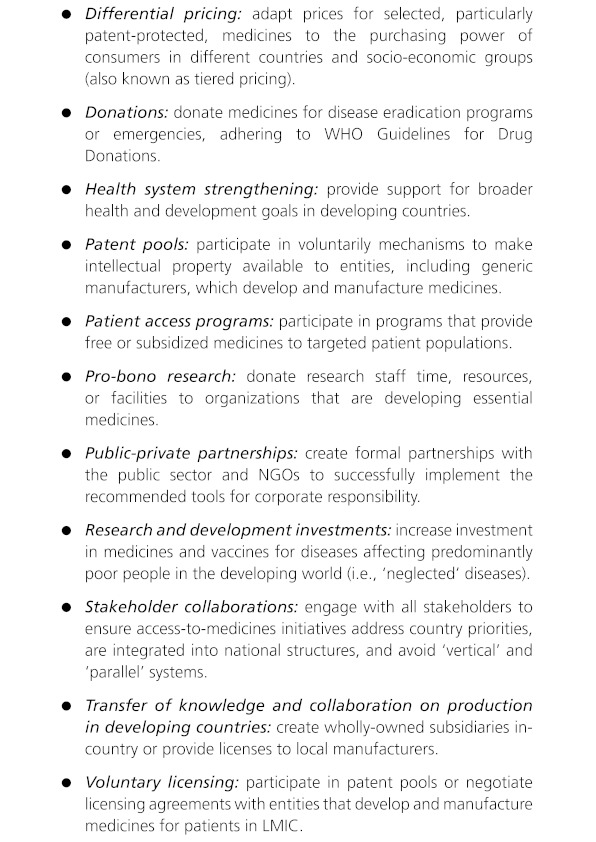

Research-based pharmaceutical companies have committed to improving access to medicines [38,39]. Figure 2 includes corporate activities recommended by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (IFPMA), [38] the UK Department for International Development (DFID) [40] and the United Nations [41] to improve access to essential medicines in LMIC and develop medicines for neglected diseases. While all of these corporate activities could be viewed as philanthropic (“can”) endeavors, many should also be considered as a part of a firms’ corporate responsibility (“ought to”) and business model.

Figure 2: Promising Corporate Responsibility Tools to Improve Access to Medicines.

However, there is no consensus among pharmaceutical companies on which activities they “ought to” pursue or prioritize. Nor is there evidence about which activities are the most effective. Differential pricing seems to be a promising strategy [42,43] since it satisfies corporate responsibility goals by improving access to medicines for the poor and, theoretically, maximizes profits through price discrimination. However, the success of differential pricing depends on the ability to regulate arbitrage, accurately forecast the market for medicines, and distribute medicines through a functioning health system [43].Several companies are applying differential pricing; it will be important to share successes and set-backs so that the industry can improve upon this strategy.

In addition to the “must,” “ought to,”and “can” activities, there are activities that industry “must not” engage in. An important example is inappropriate marketing. Industry must not use misleading, dishonest, or illegal promotional practices, such as promoting uses of medicines that will not benefit patients and misrepresenting results from the medical literature and clinical trials.

Given the human tragedy associated with inadequate access to medicines, strategies to improve access should be a corporate responsibility priority for the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical companies’ business models, and legitimacy, will increasingly depend on being perceived as a force for good in the fight against poverty-related illnesses and premature mortality. Corporate initiatives, however, cannot have their optimal impact if other stakeholders are not also doing their parts. The most sophisticated break-throughs in research and the most generous offers of low-priced medicines will make little difference for the poorest people if there is no basic health infrastructure to reach them [44]. Lack of health care infrastructure, insufficient workforce, logistic challenges, particularly in remote rural areas, and patient factors, such as misperceptions and stigma about disease and medicines, lack of health education, and poor adherence, necessitate extensive system investments. The pooling of resources, skills, experience, and goodwill across multiple stakeholders is necessary for sustainable solutions. Dialogue and collaborations are needed.

Access to Medicines - A Call for Joint Action

Consistent with encouraging multi-stakeholder discussions at the Third International Conference for Improving Use of Medicines, [45] we recommend the creation of “solution-stakeholder-teams” that include national governments, the international community, NGOs, pharmaceutical companies, and academics from multiple disciplines including medicine, public health, business, and ethics. Each team member brings unique perspectives and strengths to the development and implementation of collaborative strategies for sustainably improving access to medicines. Initial collaborations would focus on issues of common interest and win-win strategies. Examples include developing new antibiotics, increasing access to medicines for non-communicable diseases, and curbing sales of counterfeit and substandard medicines. While there are significant differences in opinion over the extent, depth, and breadth of pharmaceutical corporations’ actions to improve medicines access, there is basic agreement that differential pricing, donations, licenses, and pro bono research services are important elements.Formal evaluation of the impacts of joint interventions must be part of the solution-stakeholder-teams’ responsibilities [45].

We believe that awarding “reputation capital” for companies that actively and collaboratively expand activities in the “ought to” and “can,” and curb activities in the “must not,” categories of corporate responsibility will eventually encourage more companies to engage in more activities to improve access to medicines for the poor. Indeed, a “must,” “ought to,” “can,” and “must not” approach may be valuable to define and assess fulfillment of responsibilities of each stakeholder in the complex pharmaceutical sector.

We close with a notion of Jeffrey Sachs: “Modern businesses, especially the vast multinational companies, are the repositories of the most advanced technologies on the planet and the most sophisticated management methods for large-scale delivery of goods and services. There is no solution to the problems of poverty, population, and environment without the active engagement of the private sector [46].”

Author Contributions

Klaus Leisinger wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors participated in the collection of additional research and references and contributed to the writing of this manuscript.Opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and not of the institutions they represent.

Acknowledgments

None

Funding Statement

The Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development (NFSD), a non-profit organization under the parent company of Novartis, provided funding for this project. Klaus Leisinger is Professor of Sociology, Chairman of the Board of NFSD. NFSD provided financial support to Laura Garabedian and Anita Wagner for their contributions to the development and writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: KML is Professor of Sociology, Chairman of the Board of the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development, a non-profit organization under the parent company of Novartis, LFG and AKW were supported in part by a grant from the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.Access to Essential Medicines. In: The World Medicines Situation 2004. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2004. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js6160e/9.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Investing for Life. Meeting Poor People’s Needs for Access to Medicines through Responsible Business Practices. Oxfam Briefing Paper No.109. Vol. 27. London: Oxfam International; 2007. Investing for Life. Meeting Poor People’s Needs for Access to Medicines through Responsible Business Practices. Oxfam Briefing Paper No.109 [internet. http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/bp109-investing-for-life-0711.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Access Campaign. MédecinsSansFrontières; 2012. http://www.msfaccess.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everybody’s Business. Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. WHO: Geneva; 2007. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fact Sheet: Access to Medicines internet. London: Department for International Development (DFID); 2006. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Pubs/files/atm-factsheet0106.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Equitable access to essential medicines: a framework for collective action. WHO: Geneva; 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_EDM_2004.4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2008;373(9659):240–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quick Jonathan D. Ensuring access to essential medicines in the developing countries: a framework for action. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73(4):279–83. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(03)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowry Ashna D K, Shrank William H, Lee Joy L, Stedman Margaret, Choudhry Niteesh K. A systematic review of adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1479–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1825-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Access to Essential Medicines as Part of the Right to Health. In: The World Medicines Situation 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2011. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s18772en/s18772en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.25 Questions and Answers on Health and Human Rights. Geneva: WHO; 2002. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/a76549.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S, Ravallion M. Absolute Poverty Measures for the Developing World 1981–2004. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 43. Vol. 104. 2007: 104(43; 1675. Absolute Poverty Measures for the Developing World 1981–2004; pp. 7–16762. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17942698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winslow C-EA. The Cost of Sickness and the Price of Health. Geneva: WHO; 1951. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/monograph/WHO_MONO_7.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachs J. Primary Health for All. Scientific American. 2008.

- 15.Abbasi K. The World Bank and world health. Healthcare strategy. 6. 1999;318(7188):933–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwatkin D R, Guillot M, Heuveline P. The burden of disease among the global poor. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):586–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02108-X. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=10470717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates R. Taxed to Death. Foreign Policy. 2006 http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2006/06/12/taxed_to_death.

- 19.Filmer D, Hammer J, Pritchett L. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 1874. Washington: World Bank; 1999. ealth Policy in Poor Countries: Weak Links in the Chain. [Google Scholar]

- 20.General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI).International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations (UN); 1966. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.General Assembly Resolution 55/2. United Nations Millennium Declaration. UN; 2000. http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leach-Kemon Katherine, Chou David P, Schneider Matthew T, Tardif Annette, Dieleman Joseph L, Brooks Benjamin P C, Hanlon Michael, Murray Christopher J L. The global financial crisis has led to a slowdown in growth of funding to improve health in many developing countries. Health Aff. 2011;31(1):228–35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaglehole Robert, Bonita Ruth, Horton Richard, Adams Cary, Alleyne George, Asaria Perviz, Baugh Vanessa, Bekedam Henk, Billo Nils, Casswell Sally, Cecchini Michele, Colagiuri Ruth, Colagiuri Stephen, Collins Tea, Ebrahim Shah, Engelgau Michael, Galea Gauden, Gaziano Thomas, Geneau Robert, Haines Andy, Hospedales James, Jha Prabhat, Keeling Ann, Leeder Stephen, Lincoln Paul, McKee Martin, Mackay Judith, Magnusson Roger, Moodie Rob, Mwatsama Modi, Nishtar Sania, Norrving Bo, Patterson David, Piot Peter, Ralston Johanna, Rani Manju, Reddy K Srinath, Sassi Franco, Sheron Nick, Stuckler David, Suh Il, Torode Julie, Varghese Cherian, Watt Judith, Lancet NCD Action Group, NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=21474174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravishankar N, Gubbins P, Cooley RJ, Leach-Kemon K, Michaud CM, Jamison DT, Murray CJL. Financing of global health: tracking development assistance for health from 1990-2007. Lancet. 2009;373(9681):2113–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrett L. The Challenge of Global Health. Foreign Affairs. 2007;86(1):14–38. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narayan D. Voices of the Poor. Can Anyone Hear Us? Washington DC: Oxford University Press/World Bank; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Millennium Development Goals Report (MDG Goal #8, target#4) New York: UN; 2008. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/The%20Millennium%20Development%20Goals%20Report%202008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UN; 1948. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beynon K, Porter A. Vformance and ProspectsValuing Pharmaceutical Companies: A Guide to the Assessment and Evaluation of Assets, Performance and Prospects. Cambridge: Woodhead; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donaldson T, Dunfee TE. Ties that Bind: A Social Contracts Approach to Business Ethics. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Access to Medicines Index. 2012 http://www.accesstomedicineindex.org/content/about-us.

- 32.Health Impact Fund. 2012 http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/igh/pilot.html.

- 33.Innovative Medicines Initiative.NewDrugs4BadBugs (ND4BB) 2012 http://www.imi.europa.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/Future_Topics/IMI_AntimicrobialResistance_Draft20120116.pdf.

- 34.Johnson L. Gates Foundation, Drug Companies Push to Eliminate 10 Tropical Diseases. Huffington Post (Jan 21st) 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/30/gates-foundation-eliminate-tropical-disease-effort_n_1242491.html.

- 35.Attaran Amir. How do patents and economic policies affect access to essential medicines in developing countries. Health Aff. 2004;23(3):155–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel Aarti, Gauld Robin, Norris Pauline, Rades Thomas. Health Policy Plan. 2009;25(1):61–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leisinger K. Corporate Responsibilities for Access to Medicines. Journal of Business Ethics. 2009;85(S1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA. Principal Focus and Action of the Research-Based Pharmaceutical Industry in Contributing to Global Health. Geneva: International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA); 2008. http://www.lmi.no/dm_documents/final_industry_focus_and_actions_eng_4wcng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39. IFPMA Developing World Health Partnerships Directory. IFPMA; 2012. http://www.ifpma.org/resources/partnerships-directory.html. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Increasing People’s Access to Essential Medicines in Developing Countries: A Framework for Good Practices in the Pharmaceutical Industry. A UK Government Policy Paper. London: DFID, Department of Health, Department of Trade and Industry; 2005. Increasing People’s Access to Essential Medicines in Developing Countries: A Framework for Good Practices in the Pharmaceutical Industry. http://www.accesstomedicineindex.org/sites/www.accesstomedicineindex.org/files/publication/dfid_2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Douste-Blazy P, editor. Innovative Financing for Development. New York: UN; 2009. http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/documents/InnovativeFinForDev.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Report of the Workshop on Differential Pricing and Financing of Essential Drugs internet. Geneva: WHO and World Trade Organization; 2001. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2951e/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yadav P. Differential Pricing for Pharmaceuticals: Review of Current Knowledge, New Findings and Ideas for Action. London: DFID; 2010. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/prd/diff-pcing-pharma.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development. 2012 www.novartisfoundation.org/platform/apps/project/view.asp?MenuID=245&ID=539&Menu=3&Item=44.12.

- 45.Role of the pharmaceutical industry in medicines access and use.Summary of discussions at the Third International Conference for Improving Use of Medicines, ICIUM2011. Antalya, Turkey: ICIUM2011 Scientific Committee; 2011. http://www.inrud.org/ICIUM/Conference-Recommendations.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sachs JD. Common Wealth. Economics for a Crowded Planet. New York: The Penguin Press; 2008. p. 52. [Google Scholar]