Significance

Familial xerocytosis in humans, which causes dehydration of red blood cells and hemolytic anemia, was traced to mutations in the mechanosensitive ion channel, PIEZO1. The mutations slowed inactivation and introduced a pronounced latency for activation. Loss of inactivation and increased latency for activation could modify groups of channels simultaneously, suggesting that they exist in common spatial domains. The hereditary xerocytosis mutants affect red cell cation fluxes: slow inactivation increases them, and increased latency decreases them. These data provide a direct link between pathology and mechanosensitive channel dysfunction in nonsensory cells.

Keywords: mechanical channels, PIEZO1 mutations, channel domains

Abstract

Familial xerocytosis (HX) in humans is an autosomal disease that causes dehydration of red blood cells resulting in hemolytic anemia which has been traced to two individual mutations in the mechanosensitive ion channel, PIEZO1. Each mutation alters channel kinetics in ways that can explain the clinical presentation. Both mutations slowed inactivation and introduced a pronounced latency for activation. A conservative substitution of lysine for arginine (R2456K) eliminated inactivation and also slowed deactivation, indicating that this mutant’s loss of charge is not responsible for HX. Fitting the current vs. pressure data to Boltzmann distributions showed that the half-activation pressure, P1/2, for M2225R was similar to that of WT, whereas mutations at position 2456 were left shifted. The absolute stress sensitivity was calibrated by cotransfection and comparison with MscL, a well-characterized mechanosensitive channel from bacteria that is driven by bilayer tension. The slope sensitivity of WT and mutant human PIEZO1 (hPIEZO1) was similar to that of MscL implying that the in-plane area increased markedly, by ∼6–20 nm2 during opening. In addition to the behavior of individual channels, groups of hPIEZO1 channels could undergo simultaneous changes in kinetics including a loss of inactivation and a long (∼200 ms), silent latency for activation. These observations suggest that hPIEZO1 exists in spatial domains whose global properties can modify channel gating. The mutations that create HX affect cation fluxes in two ways: slow inactivation increases the cation flux, and the latency decreases it. These data provide a direct link between pathology and mechanosensitive channel dysfunction in nonsensory cells.

Hereditary xerocytosis (HX) is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by dehydrated red blood cells (RBCs) and mild-to-moderate hemolytic anemia. Two familial HX mutations were identified recently in the gene encoding hPIEZO1, a mechanosensitive ion channel (MSC) (1).

Mouse PIEZO1 (mPIEZO1) cloned from Neuro2A cells contains ∼2,500 amino acids predicted to have 24–36 transmembrane domains. Using crosslinking and photobleaching techniques, PIEZO1 was shown to assemble as a homotetramer (2, 3) with no other cofactors. Currently it is not known whether the pore is central to the tetramer (intermolecular) or whether each subunit conducts (intramolecular). mPIEZO1 is a cation-selective channel with a reversal potential near 0 mV. The conductance is ∼70 pS and is reduced to 35 pS by increasing extracellular Mg+2 (3, 4). mPIEZO1, like other cationic MSCs, is inhibited by the peptide GsMTx4 (5) and nonspecifically by ruthenium red (2). Heterologous expression in HEK293 cells is efficient, and mechanical currents can be evoked in whole-cell mode or patches. In cell-attached patches at hyperpolarized potentials, mPIEZO1 activates with ∼30 mmHg of pipette suction and inactivates within ∼30 ms, a rate that slows with depolarization (2–4).

To explore the biophysical properties of human PIEZO1 (hPIEZO1) that produce HX, we cloned it from HEK293 cells and then duplicated the mutations identified with HX. The mutants had slower inactivation and developed a long latency for activation. We also observed that groups of channels could change kinetics together, implying that they normally exist in confining domains that can fracture with the applied force. We showed by coexpressing MscL from bacteria with hPIEZO1 and its mutants that both PIEZO1 and the mutants have similar dimensional changes during opening (6, 7). The half-maximal activation pressure (P1/2) for two mutants was shifted to lower pressures, making them more sensitive in absolute terms. The data suggest that mutant hPIEZO1s cause symptoms by excess cation influx (8) from slow inactivation or by delayed activation resulting from increased latency.

Results

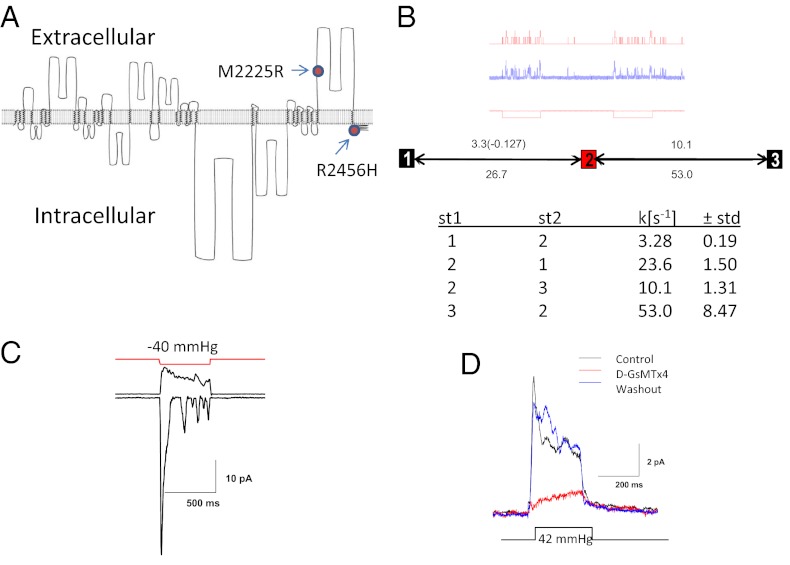

To understand the biophysical consequences of the HX mutations, we first cloned hPIEZO1 from HEK293 cells and then introduced the HX mutations at positions 2225 and 2456 (Fig. 1A). hPIEZO1 is 88% homologous to mPIEZO1. The HX mutation of M2225 is thought to reside on the extracellular side and R2456 on the intracellular side of the membrane (the full protein sequence is shown in Fig. S1). We characterized hPIEZO1’s electrophysiology by transfection into HEK293 cells. In cell-attached patches, hPIEZO1 had an open time of ∼40 ms when fit to a three-state linear model, shut-open-inactivated, with pressure sensitivity needed only in the shut-to-open rate constant (Fig. 1B). Cell-attached patches show little endogenous activity (5). Like mPIEZO1, inactivation slowed with depolarization (Fig. 1C), and activation was inhibited by GsMTx4 (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of cloned hPIEZO1. (A) A diagram showing the putative transmembrane domains of hPiezo1 and intracellular and extracellular regions. The HX mutation sites are shown where M2455R is thought to be extracellular and H2456 is intracellular. (B) Kinetic data and a fitted model for hPIEZO1 with three states (closed-open-inactivated). The theoretical fit to the model shown in red provided the kinetic rate constants shown in the table. The pressure dependence is shown in parenthesis. (C) Voltage-dependent inactivation. At depolarized voltages (+40 mV) there is slow inactivation, and at hyperpolarized voltages (−110 mV) there is rapid inactivation. (D) hPIEZO1 is inhibited by the D enantiomer of GsMTx4 (2 μM, +50 mV holding potential).

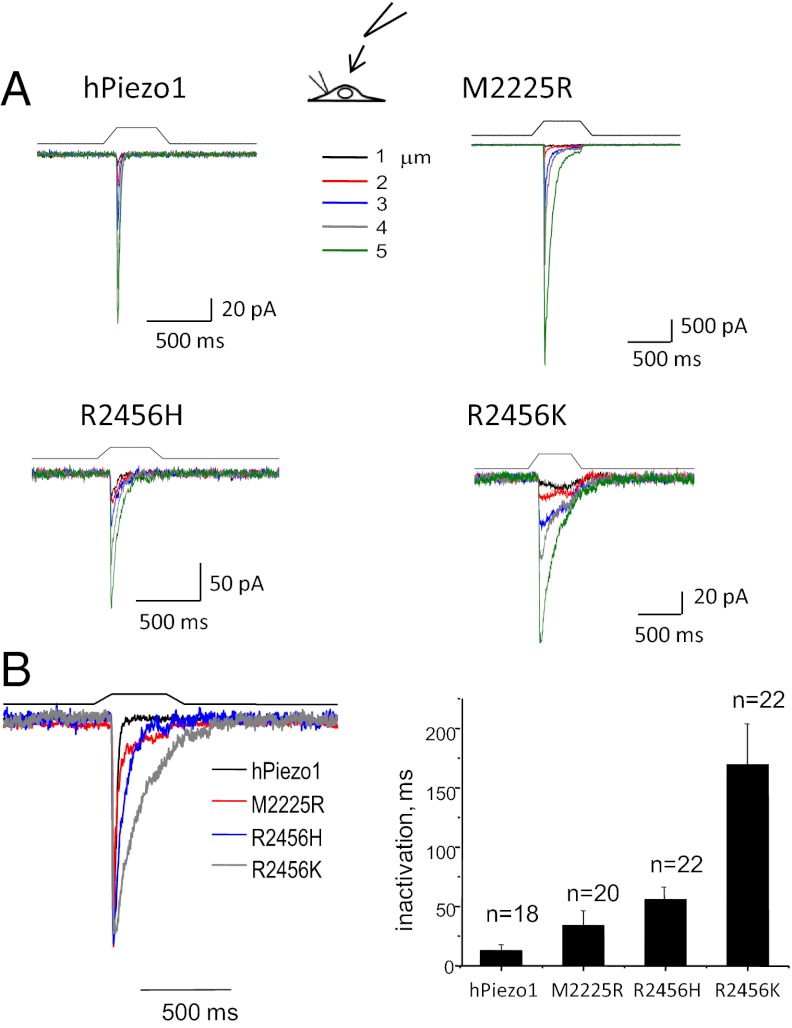

We evoked whole-cell mechanical currents by indenting the cells with a glass probe (2, 4, 9) (Fig. 2A). Both mutants, M2225R and R2456H, had slower inactivation kinetics than WT (Fig. 2), whereas GFP-transfected control cells produced no mechanically activated current (Fig. S2A). These results illustrate both transfection specificity and the “mechanoprotection” of the endogenous channels. We explored the generality of whole-cell mechanoprotection by comparing these results with cells transfected with DNA for TREK-1, a K+ selective MSC (10, 11). This transfection produced small whole-cell currents, but patches from the same cells had large currents (Fig. S2B) so that in the whole-cell configuration TREK-1 also was protected from stress, as we assume MSCs are in situ.

Fig. 2.

The effect of HX mutations on whole-cell currents. The mutations were introduced at positions 2225 or 2456 (see sequence in Fig. S1). HEK293 cells were transfected with ∼1 μg of DNA and measured 24–48 h later. (A) Whole-cell currents as a function of depth of the indenting probe. The stimulus waveform is shown above the current trace. (B) (Left) Average of repeated current traces showing the slowing of inactivation for both M2225R and R2456H. These traces have been normalized for kinetic comparison. The conservative mutation that replaced arginine with lysine at position 2456 (R2456K) was intended to measure the effect of residue charge. Despite maintaining charge, the mutation completely removed inactivation, suggesting that this site may be part of a hinge domain. (Right) The bar graph shows the mean response ± SD.

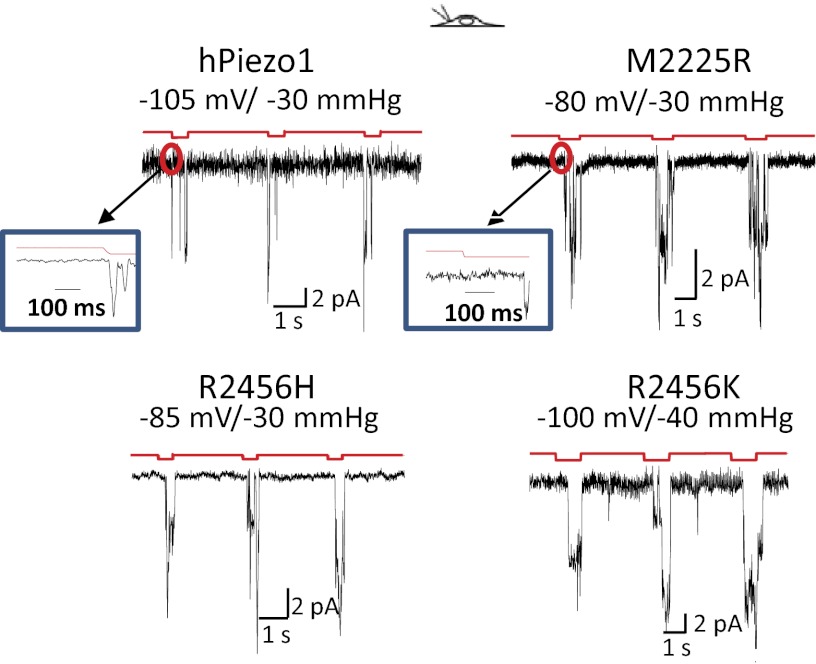

Single-channel recordings also showed kinetic differences between the mutants and WT (Fig. 3). A unique characteristic of the mutant channels, not seen in the WT, was a pronounced latency to activation (Fig. 3, compare Insets). For hundreds of milliseconds following the application of suction, there was no change in the current, followed by a sudden activation of many channels. We could not simulate this behavior with a Markov model even with many closed states, and we postulate that the latency reflects a stress-induced physical rupture of a domain containing the channels (see below).

Fig. 3.

hPIEZO1 mutations slow inactivation in cell-attached patches at single-channel resolution. M2225H and R2456H slow inactivation, and R24565 removes inactivation. (Insets) All three mutants introduced a profound latency for activation not seen in the WT.

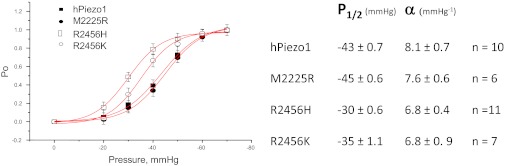

We measured the dose–response curve (current vs. pressure fit to a Boltzmann distribution) for hPIEZO1 and the mutant channels. R2456H and R2456K exhibited a leftward shift of 13 and 8 mmHg, respectively, in the P1/2, but M2225R was similar to the WT channel (Fig. 4A). The leftward shift may represent decreased stress within the resting channel protein or differences in local stress felt within a domain. In the case of TREK-1, it is known that transfection alone causes massive change to the cytoskeleton (12). In contrast to the changes we observed in P1/2, the slope sensitivity α (the maximum slope of Popen vs. pressure) was similar for WT and the hPIEZO1 mutants (7–8 mmHg−1). The constant α is proportional to the dimensional change between the closed and open conformations and suggests that the mutations did not affect the domains responsible for activation (13).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of mechanical sensitivities via peak current vs. suction and fit to a Boltzmann distribution. The mean values ± SD for P1/2 and α are shown in the table. The α is approximately the same for the four channels, indicating they have a similar dimensional change between closed and open orientations. Mutations at position 2456 shifted P1/2 but the mutation at 2225 did not.

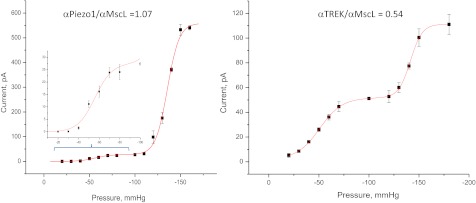

To provide an absolute measure of α, we cotransfected cells with MscL (14), a bacterial MSC known to be activated by bilayer tension and previously calibrated (7, 15, 16). The plots of peak current vs. pressure curves were fit to the sum of two Boltzmanns, one for the channel under test and one for MscL (Fig. 5). We performed this operation for hPIEZO1 (Fig. 5), two PIEZO1 mutants (Fig. S3), and TREK-1 (Fig. 5). The ratio of α for hPIEZO1 to MscL was 1.15 ± 0.14, n = 5, equivalent to a change of ∼6–20 nm2 in the in-plane area (6, 7) (assuming that both populations felt the same tension). The α was similar in the two mutant hPIEZO1 channels. However, for TREK-1, the α ratio was only 0.54 implying that this channel had a smaller dimensional change or that the local tension was about half that of the bilayer containing MscL, i.e., they resided in a different mechanical domain(s). These measurements provide an absolute measure of energetics of eukaryotic MSC gating.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the bacterial channel MscL with Piezo1 or TREK using cotransfection. (Left) Current vs. suction for hPIEZO1 and MscL in the same patch. (Inset) An expanded view of the hPIEZO1 response curve. (Right) The same measurement but using TREK-1. In contrast to hPIEZO1, TREK-1 had a lower ratio of α channel/MscL indicating either that TREK-1 has smaller dimensional changes or that the local tension around TREK-1 is smaller, as might occur if TREK-1 were in a different domain from PIEZO1.

Why did the mutations slow inactivation? R2456H resides near the cytoplasmic end of the C-terminal transmembrane span (Fig. 1A) and might be in the membrane electric field. To investigate whether the loss of charge associated with this mutation might account for the loss of inactivation, we substituted lysine for the arginine found in the WT. The resulting R2456K mutation did not inactivate and also exhibited slow deactivation (channel closing after removal of the stimulus) (Fig. 2 A and B). Residue charge did not appear to be involved. Interestingly, it is known that arginine can be modified posttranslationally, and the data from R2456K suggest such a biological change could shift the channel kinetics from phasic to tonic (17–19).

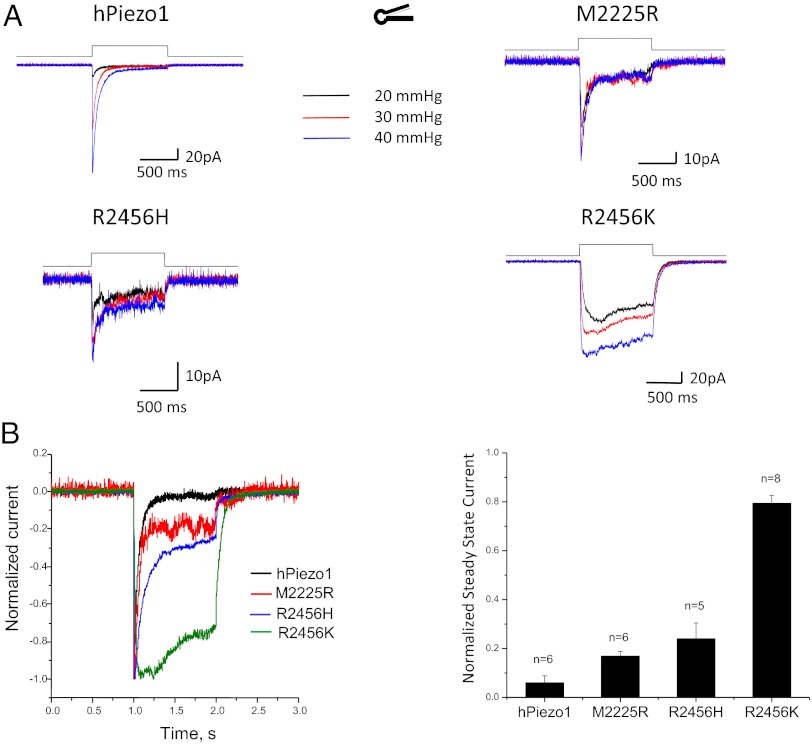

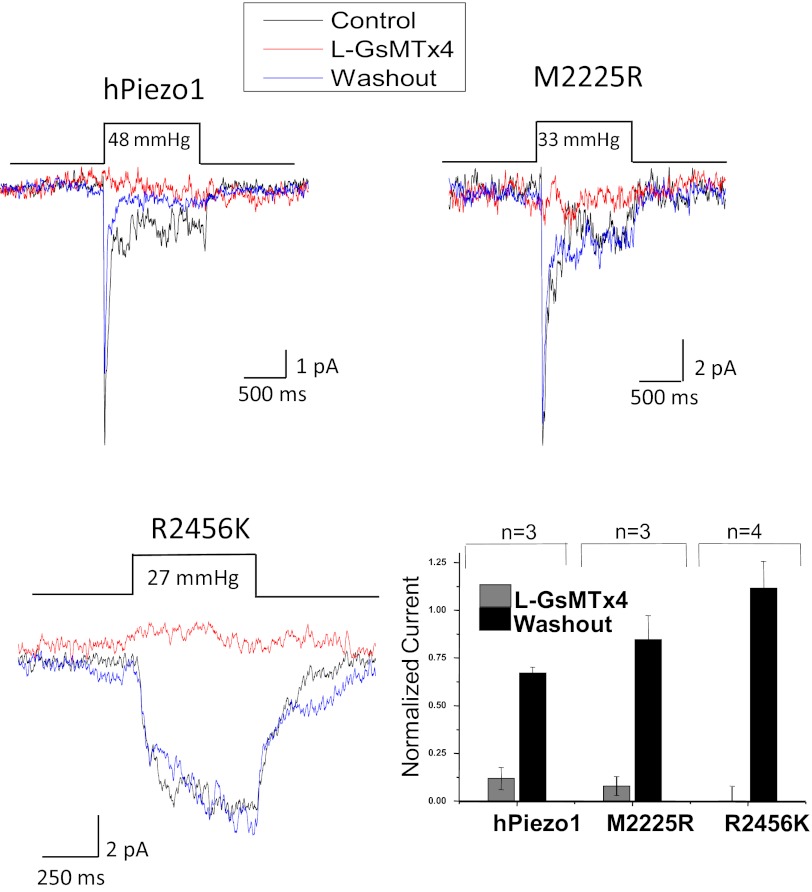

We observed some kinetic differences between cell-attached and excised patches suggesting that the cytoskeleton contributes to stress at the channel (20). In cell-attached mode, M2225R inactivated more slowly than in outside-out (O/O) patches (compare Fig. 6 and Fig. S4). The cell-attached response for a multichannel patch illustrating the loss of inactivation for mutant channels is shown in Fig. S4. Fig. 6 A and B shows data from O/O patches in which inactivation was restored almost completely in M2225R and was restored partially in R2456H. However, differences in the peak/steady-state current ratios remained, showing that the substitutions were not functionally identical. Fig. 6B shows a normalized average response, illustrating that the ratio of peak to steady-state current (an approximate assay for the relative rates of inactivation and recovery) is greater for mutants than for WT. We observed some small differences in activation kinetics between cell-attached and excised patches, but hPIEZO1 inactivated in both patch modes, and R2456K did not inactivate in either one (Fig. 6 A and B). GsMTx4 inhibited the WT and mutant channels in O/O patches (Fig. 7). Because the non-inactivating mutant R2456K was inhibited by GsMTx4, the peptide’s ability to inhibit channel activity does not appear to involve the protein region needed for hPEIZO1 inactivation.

Fig. 6.

Response of O/O patches. (A) The difference between WT and mutants. M2225R and R2456H have partially restored inactivation; R2456H remains slow; R2456K does not inactivate at all. (B) The traces normalized for kinetic comparison. The ratio of peak to steady-state current (bar graph with SD) illustrates that, even with the partial restoration of inactivation, M2225R and R2456H transfer more permeant charge than WT during an opening because of the longer open time. Deactivation (closure upon release of stress) was fast in patches from WT but was slow in mutants.

Fig. 7.

The peptide L-GsMTx4 (10 μM) reversibly inhibits mutant hPIEZO1 channels in O/O patches from cells transfected with the indicated channels. The bar graph shows the average ± SEM from the indicated number of patches. Note that R2456K did not inactivate but was inhibited, implying that the peptide does not act upon the inactivation domain.

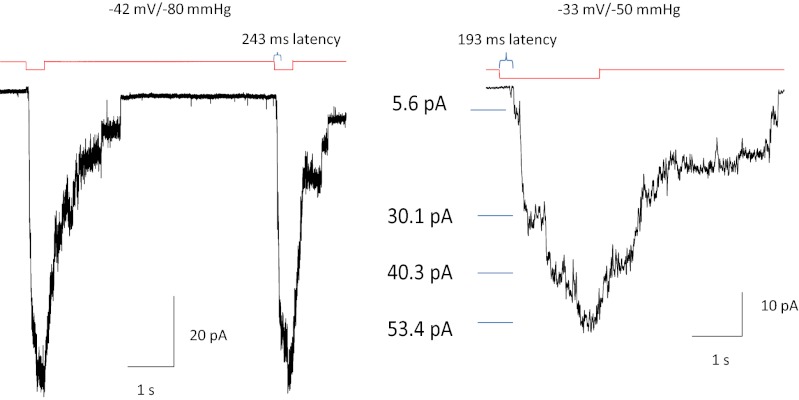

Both HX mutations were near the C terminal of hPIEZO1, so we examined the functionality of the whole region by removing it with a stop codon at position 2218 (G2218Stop). Fig. 8 shows that the truncation mutant behaved like R2456K, exhibiting a long latency, slowed or complete loss of inactivation, and very slow deactivation. Because the activation kinetics, other than latency, were largely unaffected, we conclude that the C-terminal region functions as an independent unit responsible for channel closure by inactivation or deactivation and that residue R2456 is a key locus in that region.

Fig. 8.

Removal of the C terminus with a stop codon at position 2218 of hPIEZO1 leads to a non-inactivating form of the channel with pronounced latency, loss of inactivation, and extremely slow deactivation. The slow deactivation might represent the rate for mutant monomers to reassociate. A and B show the currents from many channels in cell-attached patches, and B shows the loss of inactivation in an expanded view. The unitary conductance at −33mV was 73 pS (0.5 mM Mg2+ in pipette).

Discussion

We have characterized hPIEZO1 in an effort to understand its involvement in xerocytosis (1). The single point mutations slowed inactivation and introduced a long latency followed by activation of groups of channels (Fig. 8B). Might these changes lead to the symptoms of HX? One possibility is that they alter the mechanical sensitivity of the channel and thus change the flux of ions that accompanies mechanical stress, particularly as the RBC pass through capillaries. The relationship between cation leakage and hemolytic anemia has been observed for band 3 protein mutations (8). Although these pathways are different, band3 and PIEZO1 mutations may produce hemolytic anemia by the same mechanism.

An important feature of PIEZO1 that may contribute to the clinical presentation is its ability to pass calcium. The net cation flux through hPIEZO1 channels depends on the open time. All the mutations we tested had slower inactivation rates. R2456H had a leftward shift in activation so that it turned on at a lower stress, but M2555R did not. The slowing of the inactivation may be more important than the channel sensitivity to stress. A second, nonexclusive possibility is that because of the latency, mutant channels do not activate when needed during capillary transit.

Hydrostatic pressure has been shown to change RBC shape, membrane composition and volume, and to alter the blood flow in small vessels. An influx of Ca2+ might alter the stiffness of RBCs (21). The short open-channel lifetime of WT hPIEZO1 restricts significant ion fluxes to the immediate vicinity of the channel, and it is unclear whether such localization is significant. Thus, HX mutations might cause pathology either by too little or too much activation.

The experiments presented in this paper provide molecular details of hPIEZO1 function. Our measurements of α indicate that the dimensional changes associated with opening are similar to those reported for MscL, equivalent to 6–20 nm2 of in-plane area or an ∼1-nm change in mean radius for a 10-nm diameter channel. If the dimensional changes associated with gating were not global but instead were movements of smaller regions, then there must be a proportionately larger movement to generate the equivalent free energy described by the Boltzmann curves. For the 2D model most commonly used for MSC gating, the free energy available for gating is T∆A where T is bilayer tension and ∆A is the change of area between the closed and open states. These dimensional constraints must be met for any molecular model of hPIEZO1 gating. Because MscL is known to be gated by bilayer tension, we might suppose the same is true for hPIEZO1. If, however, hPIEZO1 were gated by cytoskeleton stress in parallel with the bilayer, the stress on the channel will be decreased because the mean tension is shared. In this case the dimensional changes of hPIEZO1 would have to be larger than MscL to explain the comparable sensitivity. This particular constraint of the dimensional changes does not apply to all MSCs. TREK-1 is half as sensitive as hPIEZO1.

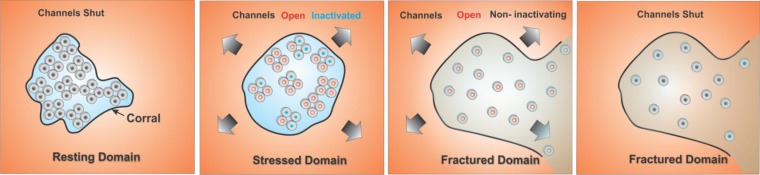

We were surprised that hPIEZO1 appeared to be in discrete physical domains separated from the common bilayer. Channel openings of multiple channels appeared suddenly following a long latency. The channels also often exhibited a collective loss of inactivation (figure 2 in ref. 4 and Fig. 8). As expected for the random sampling of the cell surface by the patch pipette, we occasionally did observe some patches that appeared to have several domains. In contrast to the mutants, WT hPIEZO1 channels activated without a measurable latency, so the domains of normal resting cells must be able to transmit the applied stimulus coming from the bilayer to the domain interior rapidly without spending time to reform the domain boundary. The collective loss of inactivation and introduction of latency has been observed previously with endogenous MSCs (4, 22). Extreme latencies (with durations in minutes) have been observed for whole-cell mechanically activated currents from heart cells (23). This transition between phasic and tonic kinetics probably represents global changes in the mechanical properties of the domains. However, with high and/or repeated stress the domain boundary can rupture, making the local tension closer to that of the mean bilayer. The modulation of ion channels by lipid microdomains has been described for other channels (24), and the clustering of channels has been noted for many channels such as in the endplate (25).

To simplify the discussion of how domain properties can alter channel kinetics, we made the cartoon model shown in Fig. 9. In this model, the resting domain boundary is folded so there is little line tension, and the external stress is transmitted rapidly to the interior, causing the channels to open and inactivate (second panel from the left). With excessive simulation, the domain ruptures allowing channels to diffuse into the external bilayer (third panel from the left). This diffusion might allow hPIEZO1 tetramers to dissociate, and, if we postulate that inactivation requires interchannel interactions, this dissociation would account for the observed collective loss of inactivation. The forces required for domain rupture are unknown but clearly are less than the lytic limit of the bilayer because the patch remained intact. The actual domains might be cytoskeletal lattices, caveolae, rafts, or other structures, and high-resolution imaging of labeled channels may permit the domains to be visualized (20).

Fig. 9.

Cartoon model of how domains might affect channel behavior. We arbitrarily modeled the domain as a cytoskeletal corral. The panel at the far left shows closed WT channels (black) in a domain with a flexible boundary that can transmit external stress without delay. In this domain the channels exist as tetramers. The second panel from the left shows the expansion of the flexible boundary with external tension causing channels to open (red) and to inactivate (blue). The panel third from the left shows what happens when high forces rupture the domain boundary. The channels diffuse outward into the bulk bilayer where the tension is sufficient to activate them, but the tetramers can dissociate. We postulate that inactivation requires channel–channel interactions so the diffusing channels do not inactivate quickly. The right panel shows deactivation in a ruptured domain after tension is removed. In this model, HX mutations would decrease the interchannel-binding energy, allowing easier dissociation. Although the cartoon shows the domain as a corral, the domain may be a lipid phase, caveolae, cytoskeletal structures, or even channel aggregates.

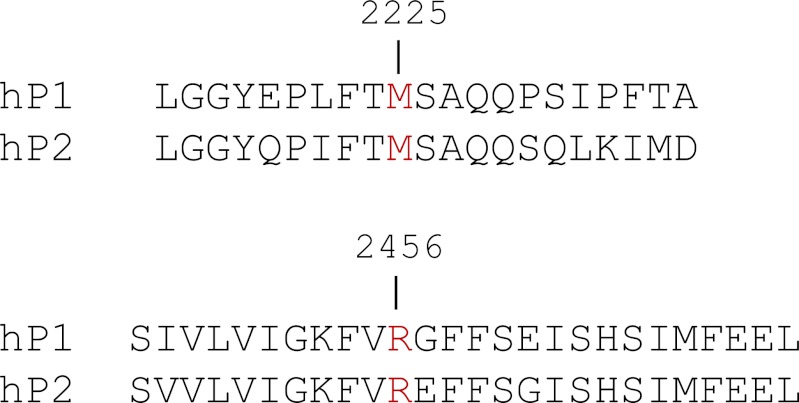

As for the physiological utility of hPIEZO1 in the circulation, the role of hPIEZO1 can be acutely tested in animals using the specific inhibitor GsMTx4 (Fig. 7) (5, 26). A transgenic mouse in which the WT channel has been replaced with the non-inactivating mutant R2456K would make a very interesting test system. hPIEZO1 is one member of the larger PIEZO family (2, 3), and the two HX sites analyzed in this study are conserved in Piezo2 (Fig. 10). Piezo2 is highly expressed in dorsal root ganglia neurons, where its function has been associated with nociception (27). If that channel behaves like hPIEZO1, a transgenic mouse with the same mutations might create a model for chronic pain. Xerocytosis provides an example of how the altered biophysical properties of MSCs can create pathology and illuminates the potential role of these channels in nonsensory tissues.

Fig. 10.

Sequence comparison between human Piezo1 and Piezo2. The amino acids in Piezo1 involved in xerocytosis also are found in Piezo2. This homology suggests that mutations at these sites in Piezo2 lead to a loss or slowing of inactivation and potential increase in nociception.

Experimental Procedures

Electrophysiology.

The bath solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes (pH 7.3, adjusted with NaOH). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 150 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.25 EGTA, 10 Hepes (pH 7.3), or, alternatively 150 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 Hepes (pH 7.3). Patch pipettes had resistances of 2–5 MΩ. For studies of TREK-1, CsCl was replaced with KCl. The mechanical stimulus for patches was suction applied with a high-speed pressure clamp (HSFC-1; ALA Scientific Instruments) and controlled by QuBIO software (www.qub.buffalo.edu). HEK293 cells were transfected with 250 ng cDNA using Fugene (Roche Diagnostic) and were tested 24–48 h later. GsMTx4 was synthesized, folded, and purified as previously described (26, 28) and was applied to cells through an ALA perfusion system controlled by QuBIO (www.qub.buffalo.edu). All experiments were done at room temperature.

Whole-cell and patch-clamp experiments were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) controlled by QuBIO, sampled at 10 kHz, and filtered at 2 kHz. The dose–response data for two different types of channels in a single patch were fit using the sum of two Boltzmann equations, one for each type of channel:

|

where Imi is the maximum available current for each channel type i, Pi is the pressure at half activation, αi is the slope sensitivity, and A is an instrumental offset. Whole-cell mechanical stimulation used indentation with a fire-polished glass pipette (tip diameter 2–4 μm) positioned at an angle of 45° to the coverslip. A computer-controlled micromanipulator (MP-285; Sutter Instruments Co.) with LabVIEW software provided coarse positioning of the probe to ∼30 μm from the cell. From there, a further rapid downward trapezoidal waveform of indentation was driven by a piezoelectric stage (P-280.20 XYZ NanoPositioners; Physik Instrumente). We define the mechanical threshold as the depth at which the probe visibly deformed the cell. The probe velocity was 0.56 μm/ms during the upward and downward movements, and the steady indentation was held constant for 400 ms. The stimulus was repeated with 0.5-μm increments every 6 s. The holding potential generally was −60 mV.

Molecular Cloning of HEK hPIEZO1.

Total RNA was extracted from HEK293 cells using Quick-RNA MicroPrep (Zymo Research) and was converted to cDNA using the SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). The hPIEZO1 gene was first amplified for 30 cycles using primers 5′-atggagccgcacgtgctcgg-3′ and 5′-ctactccttctcacgagtcc-3′ (designed from NM_001142864). A second round of amplification for 30 cycles used primers with 5′ linkers containing the Nt BbvCI sequence 5′-tcagcaagggctgagg-3′ and 5′-tcagcggaagctgagg-3′. The vector internal ribosome entry site 2 (IRES2)-EGFP was modified to include NtBbvCI sites according to the ligation-independent cloning method using nicking DNA endonuclease (29). Both the hPIEZO1 PCR product and the modified IRES2-EGFP were cut with NtBbvCI in one tube. After 8 h, the enzymes were deactivated by heating to 80 °C for 30 min and then were allowed to cool to room temperature. The DNA was transformed into Dh5Alpha cells (Invitrogen). The amplified DNA sequence of the WT hPIEZO1 cDNA was validated to ensure absence of unwanted mutations introduced by PCR amplification.

Mutagenesis of hPIEZO1.

HEK-293 hPIEZO1 mutants M2225R, R2456H, and R2456K were made using the QuikChange XL site-mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Primers used were M2225R forward, agccgctgttcaccaggagcgcccagcag; M2225R reverse, ggctgctgggcgctcctggtgaacagcgg; R2456H forward, tcggcaagttcgtgcacggattcttcagc; R2456H reverse, tctcgctaagaatccgtgcacgaacttgc; R2456K forward, tcggcaagttcgtgaagggattcttcagcgagatc; R2456K reverse, ctcgctgaagaatcccttcacgaacttgccgatgacc; G2218Stop forward, caccctgaagctgggctaatatgagccgctgttcacc; and G2218Stop reverse, ggtggacagcggctcatattagcccagcttcagggtg.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steve Besch for help in the Boltzmann analysis, Joanne Pazik and Lynn Zeigler for expert technical assistance on the molecular biology, Julia Doerner from David Clapham’s laboratory for sharing the eukaryotic vector for expression of the MscL channel, and Drs. Sidney Simon and Seth Alper for extensive editing. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, and the Children’s Guild of Buffalo.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence for human PIEZO1 has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Reference Sequence data bank (accession number KC602455).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1219777110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1. Zarychanski Y, et al. (2012) Mutations in the mechanotransduction protein PIEZO1 are associated with hereditary xerocytosis. Blood 120(9):1908–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Coste B, et al. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330(6000):55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coste B, et al. Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature. 2012;483(7388):176–181. doi: 10.1038/nature10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottlieb PA, Bae C, Sachs F. Gating the mechanical channel Piezo1: A comparison between whole-cell and patch recording. Channels (Austin) 2012;6(4):282–289. doi: 10.4161/chan.21064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae C, Sachs F, Gottlieb PA. The mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 is inhibited by the peptide GsMTx4. Biochemistry. 2011;50(29):6295–6300. doi: 10.1021/bi200770q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang CS, Anishkin A, Sukharev S. Gating of the large mechanosensitive channel in situ: Estimation of the spatial scale of the transition from channel population responses. Biophys J. 2004;86(5):2846–2861. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sukharev SI, Sigurdson WJ, Kung C, Sachs F. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113(4):525–540. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce LJ, et al. Monovalent cation leaks in human red cells caused by single amino-acid substitutions in the transport domain of the band 3 chloride-bicarbonate exchanger, AE1. Nat Genet. 2005;37(11):1258–1263. doi: 10.1038/ng1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb PA, Sachs F. Piezo1: Properties of a cation selective mechanical channel. Channels (Austin) 2012;6(4):214–219. doi: 10.4161/chan.21050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedman A, et al. The mechano-gated K(2P) channel TREK-1. Eur Biophys J. 2009;38(3):293–303. doi: 10.1007/s00249-008-0318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel A, Honore E. The TREK two P domain K+ channels. J Physiol. 2002;539(Pt 3):647. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.014829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauritzen I, et al. Cross-talk between the mechano-gated K2P channel TREK-1 and the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(7):642–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markin VS, Sachs F. Thermodynamics of mechanosensitivity. Phys Biol. 2004;1(1-2):110–124. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/1/2/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doerner JF, Febvay S, Clapham DE. Controlled delivery of bioactive molecules into live cells using the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature communications. 2012;3:990. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinac B. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels as a paradigm for mechanosensory transduction. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28(6):1051–1060. doi: 10.1159/000335842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moe P, Blount P. Assessment of potential stimuli for mechano-dependent gating of MscL: Effects of pressure, tension, and lipid headgroups. Biochemistry. 2005;44(36):12239–12244. doi: 10.1021/bi0509649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedford MT, Richard S. Arginine methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Mol Cell. 2005;18(3):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: Who, what, and why. Mol Cell. 2009;33(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch-Nolte F, et al. ADP-ribosylation of membrane proteins: Unveiling the secrets of a crucial regulatory mechanism in mammalian cells. Ann Med. 2006;38(3):188–199. doi: 10.1080/07853890600655499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suchyna TM, Markin VS, Sachs F. Biophysics and structure of the patch and the gigaseal. Biophys J. 2009;97(3):738–747. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barshtein G, Bergelson L, Dagan A, Gratton E, Yedgar S. Membrane lipid order of human red blood cells is altered by physiological levels of hydrostatic pressure. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(1 Pt 2):H538–H543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Mechanogated channels in Xenopus oocytes: Different gating modes enable a channel to switch from a phasic to a tonic mechanotransducer. Biol Bull. 1997;192(1):121–122. doi: 10.2307/1542583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bett GC, Sachs F. Whole-cell mechanosensitive currents in rat ventricular myocytes activated by direct stimulation. J Membr Biol. 2000;173(3):255–263. doi: 10.1007/s002320001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dart C. Lipid microdomains and the regulation of ion channel function. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 17):3169–3178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan NC, Ma JJ, Peng HB. Mechanosensitivity of nicotinic receptors. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464(2):193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suchyna TM, et al. Bilayer-dependent inhibition of mechanosensitive channels by neuroactive peptide enantiomers. Nature. 2004;430(6996):235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature02743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SE, Coste B, Chadha A, Cook B, Patapoutian A. The role of Drosophila Piezo in mechanical nociception. Nature. 2012;483(7388):209–212. doi: 10.1038/nature10801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostrow KL, et al. cDNA sequence and in vitro folding of GsMTx4, a specific peptide inhibitor of mechanosensitive channels. Toxicon. 2003;42(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, Zhang Z, Zhang XA, Luo Q. A ligation-independent cloning method using nicking DNA endonuclease. Biotechniques. 2010;49(5):817–821. doi: 10.2144/000113520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.