Abstract

Glial proliferation and activation are associated with disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar dementia. In this study, we describe a unique platform to address the question of cell autonomy in transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) proteinopathies. We generated functional astroglia from human induced pluripotent stem cells carrying an ALS-causing TDP-43 mutation and show that mutant astrocytes exhibit increased levels of TDP-43, subcellular mislocalization of TDP-43, and decreased cell survival. We then performed coculture experiments to evaluate the effects of M337V astrocytes on the survival of wild-type and M337V TDP-43 motor neurons, showing that mutant TDP-43 astrocytes do not adversely affect survival of cocultured neurons. These observations reveal a significant and previously unrecognized glial cell-autonomous pathological phenotype associated with a pathogenic mutation in TDP-43 and show that TDP-43 proteinopathies do not display an astrocyte non-cell-autonomous component in cell culture, as previously described for SOD1 ALS. This study highlights the utility of induced pluripotent stem cell-based in vitro disease models to investigate mechanisms of disease in ALS and other TDP-43 proteinopathies.

Keywords: glia, motor neuron disease, disease modeling

Transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) is the major component of ubiquitinated cytoplasmic and nuclear inclusions in neurons and astroglia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and a subgroup of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-TDP) (1–3). These pathological hallmarks provide a unifying description of a range of conditions defined as TDP-43 proteinopathies (4). At present, >30 mutations in the TDP-43 gene (TARDBP) have been linked to familial ALS (fALS) (5), strongly suggesting a causative role for TDP-43 in the pathogenesis of ALS.

Accumulating evidence from experimental systems implicating non-cell-autonomous mechanisms in ALS has highlighted the importance of the glial cellular environment to motor neuron (MN) degeneration (1, 3, 6–9). In vivo rodent models of ALS with lineage-specific SOD1 expression have particularly influenced our understanding of the nonneuronal contribution to disease progression. Glial expression of mutant SOD1 cannot initiate MN disease on its own, but is necessary for disease progression (6, 7). Furthermore, astrogliosis precedes MN degeneration in some animal models and is a dominant feature of all human ALS pathology (4, 6, 10). Collectively, these observations highlight the need to better understand the nature of astroglial pathology in ALS. Combining developmental neurobiological principles of cell fate determination with human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines derived from patients carrying ALS disease-causing mutations may provide important insights into astroglia pathology.

We recently generated human MNs from iPSC lines derived from a fALS patient and demonstrated that the M337V TDP-43 mutation confers cell-autonomous toxicity to MNs (11). Moreover, quantitative Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis of M337V neuronal cultures revealed an increase in levels of soluble and detergent-resistant TDP-43 proteins without any detectable changes in nuclear TDP-43 immunohistochemistry, implicating cytoplasmic misaccumulation of TDP-43 in disease pathogenesis (11). Given that key features of the TDP-43 proteinopathies could be detected in iPSC-derived neurons, and noting recent independent confirmation in multiple patient lines (12), we addressed the possibility that astroglial TDP-43 pathology could be investigated by the same approach.

Here we describe the pathological effects of mutant TDP-43 in isolated functional astrocytes, generated by a direct astrocyte specification protocol from patient-derived M337V iPSC lines. We then investigate the influence of mutant astrocytes on neurons to determine whether non-cell-autonomous toxicity can be detected in cell culture.

Results

Generating Functional Astrocyte Populations from iPSC Lines.

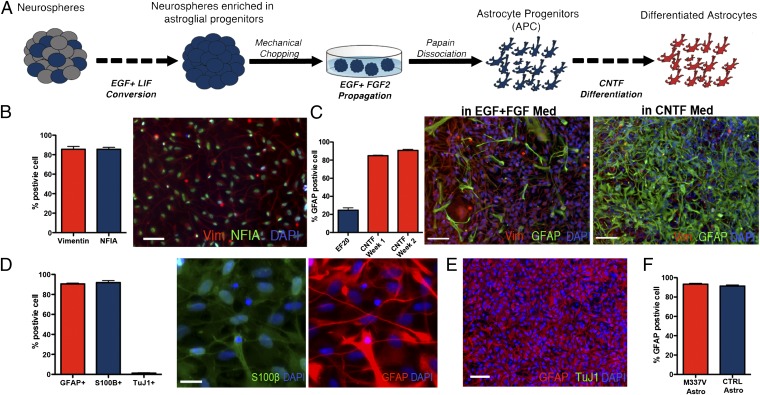

Astroglial populations from two TDP-43 M337V and two control (CTRL) iPSC lines were derived from neural precursors (NPCs) (Fig. 1A), generated as described (11). NPCs were cultured in suspension as neurospheres in medium containing epidermal growth factor (EGF) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) for 4–6 wk. In the absence of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), coapplication of EGF and LIF in prolonged culture promoted astroglial specification of NPCs (13, 14) and efficiently selected for neurospheres with a high content of astroglial progenitors. After this enrichment phase, neurospheres were expanded in EGF- and FGF2-containing medium before enzymatic dissociation to single cells. The resulting populations were positive for vimentin and nuclear factor 1A, two markers of astrocyte progenitor cells (APCs) (refs. 15 and 16; Fig. 1B), and could be propagated as a monolayer culture with EGF and FGF2. Less than 30% of cells in early passage APC cultures were positive for the astrocytic marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Subsequent differentiation over 14 d in the presence of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) increased the proportion of GFAP-positive cells with >90% of the cells coexpressing the astrocytic markers GFAP and S100β (Fig. 1 C and D). Fewer than 2% of cells were positive for the neuronal marker βIII tubulin, confirming the efficiency of this protocol in generating highly enriched APC populations.

Fig. 1.

Generation of astrocytes from iPSC lines. (A) iPSC-derived neurospheres were enriched for APCs by culturing in EGF/LIF-containing medium for 2–4 wk and then expanded in EGF/FGF2-containing medium. To obtain monolayer cultures, enriched neurospheres were dissociated by using papain and differentiated with CNTF. (B) APCs in monolayer cultures maintained a homogenous identity and morphology, featuring a high percentage of cells positive for the glial progenitors markers Vimentin (85.6 ± 2.9% SEM) and NFIA (79.8 ± 1.9% SEM; scale bar: 100 µm.) (C) APC presented 24.6 ± 2.6% SEM cells positive for GFAP during proliferation in EGF and FGF2; this percentage increased rapidly during the first 7 d of CNTF differentiation (84.9 ± 0.5% SEM), reaching a peak after 14 d (90.8 ± 1.1% SEM; scale bar: 100 μm). (D) Differentiation of monolayer APCs for 14 d in CNTF resulted in a population of astrocytes positive for GFAP (90.6 ± 0.7% SEM) and S100β (91.9 ± 1.9% SEM) (images represent the same field; scale bar: 25 µm.) A few neurons were found in the differentiated cultures (1.7 ± 0.4% SEM). (E) Representative field for a differentiated iPSC-derived astrocytes after 14 d of CNTF differentiation, labeled for GFAP (red) and TuJ1 (green), showing that the protocol gives rise to highly enriched cultures of astrocytes. (Scale bar: 100 μm). (F) M337V and CTRL iPSC lines showed comparable numbers of GFAP-positive cells postdifferentiation (M337V, 92.3 ± 1.0%; WT, 91.36 ± 1.0%; SEM).

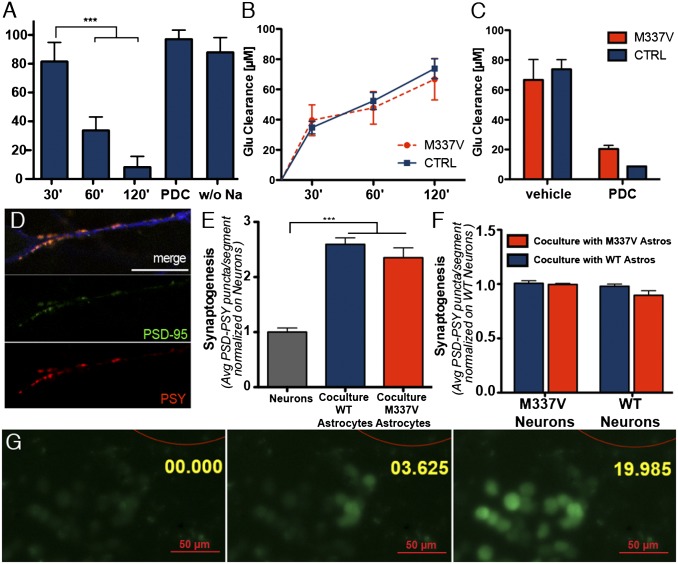

No difference was observed in the efficiencies of astrocyte differentiation in TDP-43 M337V and CTRL iPSC lines (Fig. 1F). The differentiated populations of iPSC-derived astrocytes were positive for the metabotropic glutamate transporter EAAT1 (Fig. S1) and could uptake l-glutamate from the medium in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 2A). l-glutamate uptake was blocked by the glutamate transporter inhibitor l-transpyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid or by removing sodium from the medium, consistent with the mechanism of action of EAAT1. No difference was observed in the l-glutamate clearance properties of mutant and CTRL astrocytes (Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

Functional characterization of iPSC-derived astrocytes. (A) l-glutamate uptake assay on iPSC-derived astrocytes. iPSC-derived astrocytes cleared l-glutamate in a time-dependent fashion. ***P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA). The uptake was abolished by either the absence of sodium or the presence of 2 mM L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (PDC; both negative CTRLs were run for 120 min). (B) M337V iPSC-derived astrocytes did not show a significant difference in glutamate clearance rate, compared with CTRL astrocytes (one-way ANOVA; P > 0.05 for all times considered). (C) Glutamate uptake fold increase. M337V and CTRL astrocytes were able to clear >75% of l-glutamate from the medium in 120 min, and uptake was inhibited equally by PDC. No significant difference was observed between the groups. (D) Representative immunofluorescence panels from synaptogenesis assay. Image shows representative neurite segment used for analysis, stained with TuJ1 (blue), PSY (red), and PSD-95 (green; scale bar: 15 µm). (E) iPSC-derived astrocytes significantly promoted synaptogenesis when cocultured with differentiating neurons. ***P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA). The increase in synaptogenesis was measured by scoring the number of PSY+/PSD-95+ puncta in 30-µm neurite segments (coculture M337V, 2.4 ± 0.2, SEM; coculture WT, 2.6 ± 0.1, SEM; neurons, 1.00 ± 0.08, SEM). No significant difference was observed in the behavior of M337V or CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes. Data represent the average of three independent experiments, each with two clones of M337V (M337V-1 and -2) iPSC and two independent CTRL lines (CTRL-1 and -2); data from different lines were pooled for graphical presentation. (F) Synaptogenesis assay with M337V or WT patterned neurons revealed that astrocyte promotion of synapse formation was independent from the genotype of cocultured neurons and that M337V astrocytes do not exert a negative effect on synaptic formation, even to mutant neurons. (M337V neurons on WT astrocytes, 0.90 ± 0.04, SEM; M337V neurons on M337V astrocytes, 0.98 ± 0.03 SEM; WT neurons on WT astrocytes, 1.00 ± 0.01 SEM; WT neurons on M337V astrocytes, 1.01 ± 0.02, SEM). (G) iPSC-derived astrocytes propagate calcium waves to adjacent cells upon mechanical stimulation. Red outline represents glass bead used for stimulation (200-µm diameter). Annotation represents time in seconds from stimulation.

We next sought to determine whether the iPSC-derived astrocytes promoted the formation of mature synapses. Astrocytes from either CTRL or mutant iPSC lines were cocultured with differentiating CTRL iPSC-derived ventral-spinal cord patterned neurons (11) for a period of 3 wk. Cultures were stained with antibodies against the presynaptic protein synaptophysin I (PSY) and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 to quantify the number of mature synapses in cocultures and isolated neuronal cultures (17–19). No difference between mutant and CTRL astrocytes was observed in promotion of PSY+/PSD-95+ synaptic puncta on CTRL neurons (Fig. 2 D and E). Moreover, similar numbers of PSY+/PSD-95+ synaptic puncta were found in M337V and WT neurons when cocultured with M337V or WT astrocytes, suggesting that synaptogenesis is independent of the genetic background of the neurons and the glia (Fig. 2F). Both genotypes of iPSC-derived astrocytes exhibited the potential to propagate calcium waves upon mechanical stimulation. (Fig. 2G and Movie S1). Calcium waves were also elicited when astrocytes were stimulated by local application of ATP (Movie S2), as described (20–22). This ATP-evoked increase in cytosolic calcium was abolished by application of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, an inhibitor of IP3-dependent calcium release (22) (Movie S3). These findings confirm functional equivalence between TDP43 mutant and CTRL astrocytes.

Characterization of TDP-43 in iPSC-Derived Astrocytes.

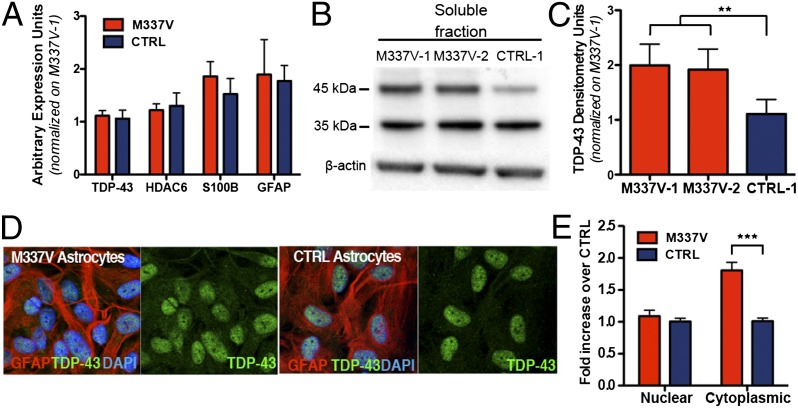

We then sought to investigate the consequence of M337V mutation on astrocyte mRNA expression, protein levels, and subcellular localization of TDP-43. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed no significant difference in the expression levels of TARDBP and HDAC6 (which is transcriptionally regulated by TDP-43 itself; ref. 23) (Fig. 3A). M337V and CTRL cultures also showed no difference in expression levels of astrocytic markers GFAP and S100β, further confirming that both genotypes can give rise to comparable astrocyte populations (Fig. 3A). Having established that the level of TDP-43 transcripts do not differ between M337V and CTRL astrocytes, we investigated whether the mutant astrocytes exhibit a cellular and biochemical signature (24) similar to that observed in MN cultures derived from the same iPSC lines (11). Immunoblot analysis showed that M337V astrocytes have significantly more soluble TDP-43 (Fig. 3 B and C), although they do not exhibit a corresponding increase in detergent-resistant TDP-43 (Fig. S2). Cytoplasmic accumulation and mislocalization of TDP-43 are also hallmarks of TDP-43 proteinopathies (25, 26), and glial inclusions are recognized in pathological material (27). Densitometric analysis of TDP-43 subcellular localization in iPSC-derived astrocytes by immunolabeling and confocal imaging revealed that M337V astrocytes exhibit significantly higher levels of cytoplasmic TDP-43 than CTRL astrocytes (Fig. 3 D and E). Interestingly, nuclear levels of TDP-43 in mutant astrocytes did not differ significantly from CTRLs, as reported for MNs (Fig. 3E) (11).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of TDP-43 in iPSC-derived astrocytes. (A) qRT-PCR expression analysis of iPSC-derived astrocytes shows no significant difference (P > 0.05 for all pairs; unpaired t test) in mRNA levels of TARDBP, HDAC6, S100β, or GFAP. Results are presented as expression fold increase normalized to M337V-1. (B) Representative Western blot from soluble TDP-43 analysis of M337V-1, -2, and CTRL-1 astrocytes. (C) Semiquantitative analyses of band signal intensity was accomplished by using ImageJ on three independent extractions (M337V-1 mean = 2.0 ± 0.4, SEM; M337V-2 mean = 1.9 ± 0.4, SEM; CTRL-1 mean = 1.1 ± 0.3, SEM). **P = 0.003 (repeated measures ANOVA). (D) Representative confocal images of TDP-43/GFAP immunolabeling used for densitometric analysis. (E) Densitometric quantification of TDP-43 localization by confocal microscopy showing a significant increase of cytoplasmic TDP-43 in M337V astrocytes; results are presented as densitometric signal fold increase normalized to the CTRL (n = 4 independent experiments). ***P < 0.001.

Ectopic Mutant TDP-43 Expression in CTRL Astrocytes Reproduces Cellular Phenotype of Patient-Derived M337V Astrocytes.

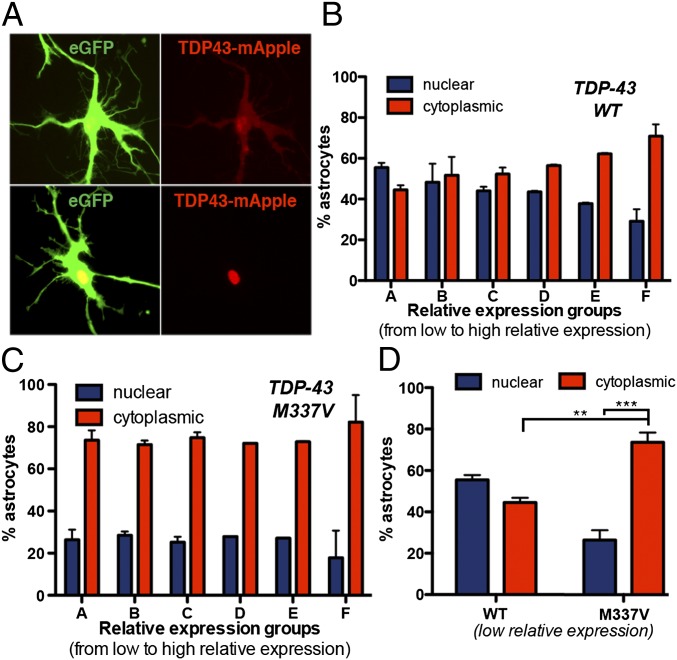

Previous studies demonstrated that ectopic expression of TDP-43 M337V in neurons is toxic and that cytoplasmic localization of TDP-43 is independently associated with an increased risk of death (28). To determine whether M337V TDP-43 was similarly toxic to astrocytes, CTRL iPSC astrocytes were first transfected with a plasmid encoding either WT or M337V TDP-43 fused to mApple, under the control of a constitutive promoter (Fig. 4A). Images were then analyzed for survival, localization, and relative expression levels of exogenous TDP-43 within transfected cells. The transfected astrocyte populations were divided in five different groups based on the relative expression levels of exogenous TDP-43 (Fig. S3). Within the different expression groups, the localization of exogenous TDP-43 was then analyzed. Astrocytes with prominent nuclear localization of transfected WT or M337V TDP43::mApple were grouped and compared with astrocytes with nuclear-and-cytoplasmic or exclusively cytoplasmic fluorescence. We noted a strong influence of expression levels on TDP-43 localization. Elevated expression levels were directly related to cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 (Fig. 4B), as reported (28). However, whereas WT TDP-43 displayed a dynamic range of localization correlating with expression levels, M337V TDP-43 showed an inherent bias toward cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 4C), even at low expression levels (Fig. 4D). These results confirm that the observed changes in localization of TDP-43 in iPSC-derived astrocytes are due to the presence of the M337V mutation on TARDBP.

Fig. 4.

Ectopic TDP-43 expression partially reproduces the iPSC phenotype. (A) Representative images of cytoplasmic and nuclear-only TDP43:mApple-transfected astrocytes showing the criteria for inclusion of astrocytes in either cytoplasmic (Upper) or nuclear (Lower). (B) Analysis of exogenous WT TDP-43 localization on stratified relative expression groups. The localization of WT TDP-43 was significantly related to relative expression levels [nuclear vs. cytoplasmic TDP-43: A, not significant (n.s.); B, n.s.; C, n.s.; D, P < 0.05; E, P < 0.01; F, P < 0.001). Data are pooled from three independent experiments. (C) Analysis of exogenous M337 TDP-43 localization on stratified relative expression groups. M337V TDP-43 remained localized mainly to the cytoplasm regardless of expression level (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic TDP-43: A–F, P < 0.001). Data are pooled from three independent experiments. (D) Comparison of ectopic TDP-43 localization in astrocytes from the lowest relative expression level groups (group A in B and C). At low expression levels, 73.6 ± 3.3% of astrocytes from the TDP43M337V:mApple group presented mainly or exclusively cytoplasmic localization of the protein, compared with 44.5 ± 1.6% in the TDP43WT:mApple. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

Survival Analysis on iPSC-Derived Astrocytes.

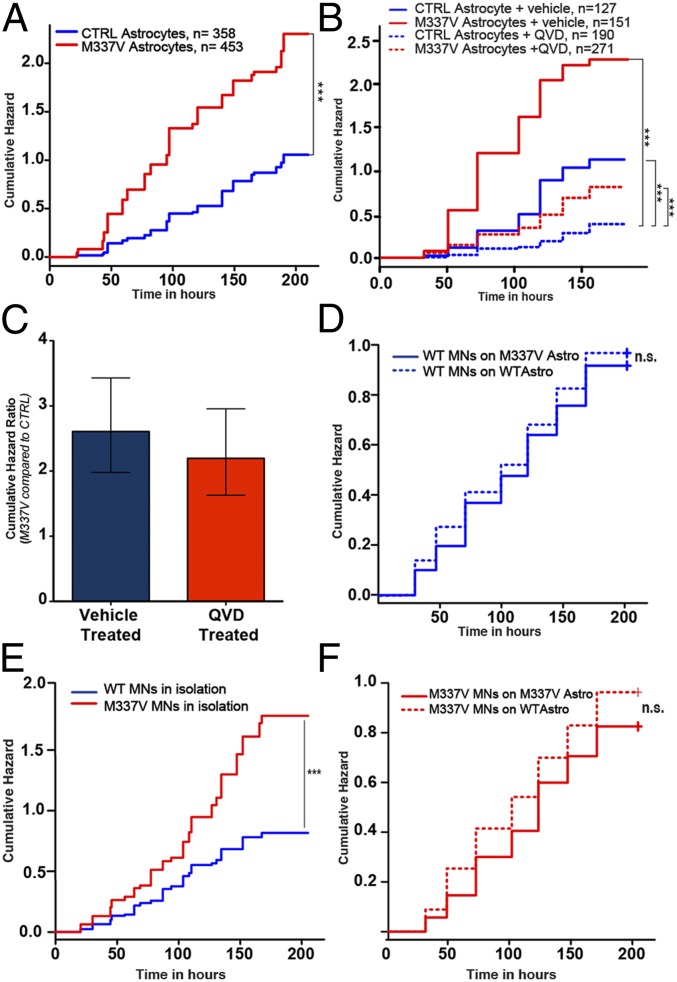

We next asked whether the accumulation of soluble and cytoplasmic TDP-43 was accompanied by a reduction in survival as assessed by longitudinal live fluorescence microscopy as described (11, 28). M337V and CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes were transfected with a plasmid that constitutively expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and imaged every 24 h for 10 d. Astrocyte death was marked by loss of fluorescence or dissolution of the cell itself (Fig. S4). These criteria are at least as specific as traditional markers of particular cell death pathways (29), have the advantage of detecting all forms of cell death in a single assay, and are therefore more sensitive. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to plot cumulative hazard curves depicting the risk of death for M337V and CTRL astrocytes (Fig. 5A). Cox proportional hazards analysis was then applied to calculate the relative risk over four independent experiments, demonstrating a cumulative hazard ratio (HR) of 2.5 (P = 2 × 10−16; log-rank test) for M337V astrocytes, indicating a 2.5-fold greater risk of death associated with the TDP-43 M337V mutation in comparison with CTRLs.

Fig. 5.

Survival analysis on iPSC-derived astrocytes and MN-astrocyte cocultures. (A) Real-time survival analysis of M337V iPSC-derived astrocytes and CTRLs. Mutant astrocytes showed increased cumulative risk of death associated with M337V TDP-43 under basal conditions (HR = 2.5, P = 2 × 10−16; CTRL taken as baseline; ***P < 0.001). (B) Real-time survival analysis of M337V and CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes in the presence of 10 µM QVD-oph. The inhibition of caspase activation reduced the risk of death in M337V and CTRL astrocytes (with CTRL+vehicle as a reference, in M337V+vehicle, HR = 2.61, P = 8.13 × 10−12; M337V+QVD, HR = 0.72, P = 0.0145; CTRL+QVD, HR = 0.33, P = 5.07 × 10−11; ***P < 0.001). (C) Comparison between cumulative HR of M337V astrocytes in QVD- and vehicle-treated groups. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (D) Real-time survival analysis of WT iPSC-derived MNs plated on either M337V or CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes. Mutant astrocytes were not toxic to cocultured WT MNs (with WT MNs on WT astrocytes as a reference, in WT MNs on M337V astrocytes, HR 0.98; P = 0.68). (E) Real-time survival analysis of MNs cultured in isolation (n = 3), demonstrating cell-autonomous toxicity of mutant TDP43 (with WT as a reference, in M337V, HR = 2.02; P = 8.91 × 10−7). (F) Longitudinal analysis of M337V MNs plated on either WT or M337V astrocytes. Both WT and M337V astrocytes improved the survival of M337V MNs. M337 astrocytes had no detectable toxicity to cocultured MNs. All graphs represent pooled data from three independent experiments.

Having established that the M337V mutation reduces the survival of astrocytes under basal conditions, we then investigated the mechanism of this toxicity. To determine whether the observed cell death was due to increased apoptosis, the effect of pan-caspase inhibitor QVD-oph was measured (30). Treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor decreased the cumulative HR of M337V and CTRL astrocytes. QVD-treated CTRL astrocytes showed a cumulative HR of 0.33 (P = 5.07 × 10−11; log-rank test) compared with the vehicle-treated group. On the M337V background, the QVD-treated group showed a HR of 0.72 (P = 0.0145; log-rank test, compared with vehicle-treated CTRL astrocytes), and the vehicle-treated M337V group showed a HR of 2.66 (P = 8.13 × 10−12; log-rank test, compared with vehicle-treated CTRL astrocytes) (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the presence of caspase inhibitor decreased the risk of death more than threefold in both genotypes. However, when the M337V and WT QVD-treated groups were compared directly, the M337V astrocytes still displayed a significantly greater HR than WT astrocytes (2.19; P = 2.32 × 10−7; log-rank test). The comparison of HRs between M337V and CTRL astrocytes with QVD or vehicle-only treatment revealed that caspase inhibition failed to significantly lower mutant TDP43-specific toxicity (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, survival analysis performed within the transfected astrocyte populations described earlier revealed that cytoplasmic localization of mutant TDP-43 was associated with a 223% increase in the risk of death (HR = 2.23; P = 0.0002). These results suggest that cytoplasmically mislocalized M337V TDP-43 significantly increases the risk of death of astrocytes.

Analysis of MN–Astrocyte Cocultures.

We next sought to determine whether mutant M337V astrocytes exert a non-cell-autonomous toxic effect on MNs, similar to that described for mutant SOD1 rodent astrocytes (1, 8, 9, 31, 32). To this end, we first verified the utility of survival analysis by longitudinal microscopy for detecting non-cell-autonomous toxic effects of glia on WT MNs derived from human iPSCs by coculturing HB9:GFP-transfected WT MNs on murine primary astroglia overexpressing either hSOD1WT or hSOD1G93A. This experiment, as predicted from previous studies (8), revealed an increased toxic non-cell-autonomous effect exerted by hSOD1G93A glia compared with hSOD1WT counterparts on WT MNs (Fig. S5), confirming that a longitudinal microscopy-based survival analysis approach is capable of detecting astrocyte toxicity in human iPSC-derived MN cocultures. Next, we plated HB9:GFP-transfected iPSC-derived MNs from both genotypes on a monolayer of either mutant or CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes and compared their survival by real-time longitudinal microscopy as described (11). We first tested the effect of CTRL and mutant astrocyte background on the survival of WT MN cultures. The cumulative risk of death of WT MNs cultured on mutant astrocytes was not significantly different from that of WT MNs cultured on WT astrocytes, suggesting that mutant astrocytes are not toxic to WT MNs (Fig. 5D).

We next determined the survival of mutant M337V MNs in astrocyte coculture experiments. First, we confirmed that mutant MNs cultured in isolation demonstrated greater cell-autonomous vulnerability than CTRL MNs, as previously shown (Fig. 5E) (11). Using real-time survival analysis, we found that mutant astrocytes did not exert non-cell-autonomous toxic effects, even on MNs carrying the M337V TDP-43 mutation (Fig. 5F). Indeed, when cocultured with astrocytes of either genotype, the previously observed cell-autonomous vulnerability of isolated mutant MNs was no longer evident. These results suggest that, independent of the genetic background of glia, astrocyte coculture rescues the survival difference associated with the TDP-43 M337V mutation in motor neuronal cultures and that iPSC-derived TDP-43 mutant astrocytes do not exert an in vitro toxic effect on neurons.

Discussion

The present study describes a platform to study the glial component of TDP-43 proteinopathies and its effect on cocultured neurons. We efficiently generated near-homogenous populations of astrocytes from both CTRL and mutant iPSC lines and cocultured astrocytes and MNs from different genetic backgrounds to study potential non-cell-autonomous contributions to ALS pathology.

We exploited developmental progliogenic signaling pathways to generate enriched and scalable astroglial progenitors. Propagating NPCs with LIF and EGF, but without FGF2, promoted glial commitment and expansion and resulted in efficient APC fate specification within 6 wk (33–36). A number of methodologies derive astroglia from pluripotent cells with varying levels of function and purity (37–40). The protocol described here achieves functional astrocyte differentiation without serum supplementation, presenting a more chemically defined and comparatively faster alternative to other methods (37). The resulting astroglial populations have low numbers of neuronal cells (<2%), enabling the study of astroglial survival, function, and biochemistry in near-homogenous populations. This homogeneity has a clear benefit over methodologies that yield glial populations with greater neuronal differentiation (38) or those that require longer periods of time. Highly enriched astrocyte populations can also be generated by prolonged culture (3–9 mo) of neural progenitors with gradual temporal loss of neurogenic potential, similar to the neurogenic–gliogenic switch during development (39, 40).

M337V-expressing astrocytes displayed cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 with elevated levels of soluble TDP-43 protein, which was not due to an increase in TARDBP mRNA. There was no increase in detergent-resistant TDP-43 in M337V mutant astrocytes, but their survival was significantly reduced under basal conditions. The effects on survival were replicated in CTRL iPSC-derived astrocytes transiently transfected with M337V mutant TDP-43. These features are comparable to earlier findings in isolated MN cultures (12) and, together with the increased stability of mutant TDP-43 reported in isogenic stable cell lines (41), suggest that the M337V mutation affects TDP-43 protein levels via a posttranslational mechanism. It is also of interest that in the astrocyte populations analyzed, TDP-43 does not seem to negatively autoregulate its own mRNA, as reported in established stable lines (42). Mutant astrocytes, unlike mutant MNs derived from the same lines, do not show increased levels of detergent-resistant TDP-43 levels. The reason for this finding is unclear but suggests different cell-specific processing of protein accumulation. Along with accumulation of soluble TDP-43, mutant astrocytes displayed inherent mislocalization of cytoplasmic TDP-43. Increased cytoplasmic TDP-43 levels were not accompanied by a corresponding depletion of nuclear TDP-43, further supporting the idea that the additional TDP-43 is due to increased stability and/or slower clearance. Interestingly, the loss of TDP-43 nuclear localization has been linked to neuronal degeneration in TDP-43 proteinopathies in animal models (43) and cellular systems (44, 45). The absence of TDP-43 nuclear clearance in M337V iPSC-derived MNs (11) and astrocyte cultures suggests that loss of nuclear TDP-43 is a later event in the disease process.

Survival analysis of M337V iPSC-derived astrocytes revealed a significantly greater risk of death compared with WT astrocytes under basal conditions. This result represents a unique report of cell-autonomous astrocyte toxicity in a mutant iPSC line. These findings are consistent with the idea that—at least initially or in part—reactive astrogliosis observed in ALS might not be simply a response to neuronal injury but a consequence of direct mutation-mediated astrocyte toxicity. Treatment of mutant and CTRL astrocytes with pan-caspase inhibitor resulted in a three to fourfold improvement in cell survival on both genetic backgrounds. However, when QVD-treated M337V and CTRL astrocytes were compared directly, they still had a significant difference in their survival, as measured by Cox proportional hazards analysis. This result suggests that the difference in survival between M337V and CTRL astrocytes can be attributed to caspase-independent mechanisms. Indirect support for this possibility is based on the absence of TDP-43 aggregates or significant increase of TDP-43 cleavage products in mutant astrocytes, both of which are associated with caspase activity (46, 47). Although further studies are required to gain a better understanding of the mechanism of M337V TDP-43 toxicity on astrocytes, the ectopic M337V and WT TDP-43 expression studies on isogenic WT astrocytes reported here demonstrate that the M337V mutation confers an inherent bias toward cytoplasmic localization. In turn, the observation that cytoplasmic localization is associated with an increased risk of death offers an interesting correlation between the increased cytoplasmic TDP-43 of iPSC-derived astrocytes and their lower survival, compared with CTRLs. Importantly, these experiments involved isogenic human astrocytes, so the differences in mislocalization and toxicity can be attributed specifically to the presence of a disease-associated mutation in TDP-43, and not to potential influences of differences in genetic background.

Recent in vitro and in vivo models convincingly demonstrated that astrocytes mediate, at least in part, disease progression in SOD1 fALS models (1, 8, 9, 31, 32). This finding, in turn, led to the concept of non-cell-autonomous neurodegeneration. However, SOD1 fALS cases, unlike the great majority of sporadic ALS (sALS) and fALS cases, do not show TDP-43 pathology and are not therefore classified as TDP-43 proteinopathies (26). Understanding whether the TDP-43 mutation carrying astrocytes have a comparable neurotoxic effect is thus of great interest. Our previous iPSC-based study showed that the M337V mutation impairs survival in isolated MNs cultured under basal conditions (11). In this study, we used the same longitudinal microscopy–based approach to examine the survival of MNs cocultured with either M337V or CTRL astrocytes. We detected no significant difference in survival of CTRL MNs plated on mutant astrocytes and equivalent MNs cocultured with CTRL astrocytes. Importantly, we show, using the same longitudinal microscopy-based methodology, that murine glia overexpressing hSOD1G93A are toxic to human iPSC-derived MNs, confirming the ability of this experimental system to address cellular autonomy in iPSC-based models as has previously been shown in other xeno-cultures (1, 8).

Notwithstanding the necessity of further validation of our results in independent human iPSC lines, our results suggest a potential difference in the consequence of astroglial–neuronal interaction, at least when modeled under basal conditions in vitro, between SOD1 and TDP-43 fALS. Interestingly, astrocytes derived from postmortem sALS and SOD1MT fALS patient material have a non-cell-autonomous toxic effect on mouse ES cell-derived MNs, extending the concept of toxicity mediated by reactive astroglia to include sporadic MN disease (9). Reactive astrogliosis is defined by a number of phenotypic changes in astrocytes (7), and the extent of mechanistic overlap between the SOD1MT fALS and sALS astroglia-mediated MN toxicity remains to be independently confirmed. It is also important to note that non-cell-autonomous toxicity of human sporadic or, indeed, SOD1MT iPSC-derived astrocytes has, to date, not been reported. One potential explanation is that in vitro differentiation of astrocytes from human iPSCs, as in our study, in the absence of degenerating neurons does not capture some of the as-yet-uncharacterized mutation-specific or more general reactive properties of in vivo astroglia. Nevertheless, the platform described here is ideal to study both the reactive properties of in vitro-generated astrocytes and the potential differences between astrocytes generated from sALS and other fALS iPSC lines.

In conclusion, this study established a platform to address the biological consequence of somatic mutations on human iPSC-derived astroglia and to dissect the contribution of glial–neuronal cross-talk in neurodegenerative processes. The application of the platform to study the non-cell-autonomous component of TDP-43 proteinopathies and the description of a previously unrecognized cell-autonomous TDP-43 toxic effect on astrocytes further highlight the potential of using patient-derived iPSCs to gain a deeper understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Astrocytes from iPSC Lines.

Generation of neurospheres from iPSC lines and their patterning to acquire MN progenitor identity were as described (11). Neurospheres were mechanically chopped at the beginning of the enrichment phase and cultured in NSCR EL20 medium for 2–4 wk. After enrichment, the spheres were propagated in EGF and FGF2 containing medium and passaged mechanically by chopping them every 2 wk. Details on establishment of monolayer cultures, dissociation of spheres, media composition, and functional characterization of the astrocytes are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Survival Analysis.

For survival analysis, differentiated astrocytes were plated on 96-well Matrigel-coated plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and transfected with pGW1-mApple (Fig. 2G) or cotransfected with pGW1-EGFP and pGW1-TDP43:mApple (Fig. 2 H and I) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For analysis of cocultures, dissociated MNs from patterned neurospheres were plated on 96-well Matrigel-coated astrocyte plates after transfection, as described (11). A robotic microscope system was used to perform the imaging (28, 29). Following transfection, cells were imaged at 24-h intervals for 10 d, and survival was determined by using algorithms developed in MatLab and ImageJ. Details on transfections, survival analysis software, and procedures used are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by Euan MacDonald Centre (S.C.), Fidelity Foundation (S.C.), Motor Neurone Disease Association (S.C., T.M., and C.E.S.), Medical Research Council (C.E.S.), Wellcome Trust (S.C. and C.E.S.), the Heaton-Ellis Trust (C.E.S.), ALS Association (S.F., M.A.C., and H.P.P), National Institutes of Neurological Disease and Stroke (S.J.B., S.F., and T.M), National Institutes on Aging (S.F.) and a National Institutes of Health grant (8DP1NS082099-06) to T.M.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 4439.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300398110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Di Giorgio FP, Boulting GL, Bobrowicz S, Eggan KC. Human embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons are sensitive to the toxic effect of glial cells carrying an ALS-causing mutation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchetto MCN, et al. Non-cell-autonomous effect of human SOD1 G37R astrocytes on motor neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ince PG, et al. Molecular pathology and genetic advances in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: An emerging molecular pathway and the significance of glial pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(6):657–671. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0913-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sreedharan J, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319(5870):1668–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffer D, Cordera S, Cavalla P, Migheli A. Reactive astrogliosis of the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1996;139(Suppl):27–33. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas MR, Johnson JA. Astrogliosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Role and therapeutic potential of astrocytes. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7(4):471–481. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Giorgio FP, Carrasco MA, Siao MC, Maniatis T, Eggan K. Non-cell autonomous effect of glia on motor neurons in an embryonic stem cell-based ALS model. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(5):608–614. doi: 10.1038/nn1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haidet-Phillips AM, et al. Astrocytes from familial and sporadic ALS patients are toxic to motor neurons. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(9):824–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargas MR, Pehar M, Díaz-Amarilla PJ, Beckman JS, Barbeito L. Transcriptional profile of primary astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutant SOD1. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(16):3515–3525. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilican B, et al. Mutant induced pluripotent stem cell lines recapitulate aspects of TDP-43 proteinopathies and reveal cell-specific vulnerability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):5803–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egawa N, et al. Drug screening for ALS using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(145):145ra104. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanalkumar R, Vidyanand S, Lalitha Indulekha C, James J. Neuronal vs. glial fate of embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors (ES-NPs) is determined by FGF2/EGF during proliferation. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;42(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namihira M, et al. Committed neuronal precursors confer astrocytic potential on residual neural precursor cells. Dev Cell. 2009;16(2):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mi H, Barres BA. Purification and characterization of astrocyte precursor cells in the developing rat optic nerve. J Neurosci. 1999;19(3):1049–1061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deneen B, et al. The transcription factor NFIA controls the onset of gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. Neuron. 2006;52(6):953–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullian EM, Harris BT, Wu A, Chan JR, Barres BA. Schwann cells and astrocytes induce synapse formation by spinal motor neurons in culture. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25(2):241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diniz LP, et al. Astrocyte-induced synaptogenesis is mediated by transforming growth factor beta signaling through modulation of D-serine levels in cerebral cortex neurons. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(49):41432–41445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullian EM, Sapperstein SK, Christopherson KS, Barres BA. Control of synapse number by glia. Science. 2001;291(5504):657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guthrie PB, et al. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999;19(2):520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fanelli A, et al. Temporal and spatial analysis of astrocyte calcium waves. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:6038–6041. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Changes in intracellular calcium and glutathione in astrocytes as the primary mechanism of amyloid neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23(12):5088–5095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05088.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiesel FC, et al. Knockdown of transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) downregulates histone deacetylase 6. EMBO J. 2010;29(1):209–221. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumann M, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 11):2922–2931. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arai T, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351(3):602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwong LK, Uryu K, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y. TDP-43 proteinopathies: Neurodegenerative protein misfolding diseases without amyloidosis. Neurosignals. 2008;16(1):41–51. doi: 10.1159/000109758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishihira Y, et al. Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Two pathological patterns shown by analysis of distribution of TDP-43-immunoreactive neuronal and glial cytoplasmic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(2):169–182. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barmada SJ, et al. Cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 is toxic to neurons and enhanced by a mutation associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2010;30(2):639–649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrasate M, Finkbeiner S. Automated microscope system for determining factors that predict neuronal fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(10):3840–3845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409777102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Léveillé F, et al. Suppression of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway by synaptic activity. J Neurosci. 2010;30(7):2623–2635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5115-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamanaka K, et al. Mutant SOD1 in cell types other than motor neurons and oligodendrocytes accelerates onset of disease in ALS mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(21):7594–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802556105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamanaka K, et al. Astrocytes as determinants of disease progression in inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(3):251–253. doi: 10.1038/nn2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viti J, Feathers A, Phillips J, Lillien L. Epidermal growth factor receptors control competence to interpret leukemia inhibitory factor as an astrocyte inducer in developing cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3385–3393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda S, et al. Potentiation of astrogliogenesis by STAT3-mediated activation of bone morphogenetic protein-Smad signaling in neural stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(13):4931–4937. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02435-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajan P, Panchision DM, Newell LF, McKay RDG. BMPs signal alternately through a SMAD or FRAP-STAT pathway to regulate fate choice in CNS stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(5):911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tropepe V, et al. Distinct neural stem cells proliferate in response to EGF and FGF in the developing mouse telencephalon. Dev Biol. 1999;208(1):166–188. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juopperi TA, et al. Astrocytes generated from patient induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulate features of Huntington’s disease patient cells. Mol Brain. 2012;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emdad L, D’Souza SL, Kothari HP, Qadeer ZA, Germano IM. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells into functional astrocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(3):404–410. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krencik R, Weick JP, Liu Y, Zhang Z-J, Zhang S-C. Specification of transplantable astroglial subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(6):528–534. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu B-Y, et al. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ling S-C, et al. ALS-associated mutations in TDP-43 increase its stability and promote TDP-43 complexes with FUS/TLS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(30):13318–13323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008227107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayala YM, et al. TDP-43 regulates its mRNA levels through a negative feedback loop. EMBO J. 2011;30(2):277–288. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igaz LM, et al. Dysregulation of the ALS-associated gene TDP-43 leads to neuronal death and degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(2):726–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI44867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishimura AL, et al. Nuclear import impairment causes cytoplasmic trans-activation response DNA-binding protein accumulation and is associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 6):1763–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winton MJ, et al. Disturbance of nuclear and cytoplasmic TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) induces disease-like redistribution, sequestration, and aggregate formation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(19):13302–13309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800342200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y-J, et al. Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(18):7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang C, et al. The C-terminal TDP-43 fragments have a high aggregation propensity and harm neurons by a dominant-negative mechanism. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.