Abstract

Ebolavirus, a member of the Filoviridae family of negative-sense RNA viruses, causes severe haemorrhagic fever leading up to 90% lethality. Ebolavirus matrix protein VP40 is involved in the virus assembly and budding process. The RNA binding pocket of VP40 is considered as the drug target site for structure based drug design. High Throughput Virtual Screening and molecular docking studies were employed to find the suitable inhibitors against VP40. Ten compounds showing good glide score and glide energy as well as interaction with specific amino acid residues were short listed as drug leads. These small molecule inhibitors could be potent inhibitors for VP40 matrix protein by blocking virus assembly and budding process.

Keywords: Ebolavirus, VP40, High throughput virtual screening, Molecular docking

Background

The increased threat of terrorism necessitates an evaluation of the risk posed by various microorganisms as biological weapons. Especially, Filoviruses is one of such important microorganisms. Ebola virus and Marburg virus are category A bioweapon organisms. Biowarfare agents are considered as potential biological weapons because they pose a threat as lethal pathogens and because their use by terrorists might result in extreme fear and panic [1, 2].

The attraction for bioweapons in war and for use in terroristic attacks is attributed to their low production costs, the easy access to a wide range of disease-producing biological agents, their non-detection by routine security systems and their easy transportation from one location to another [3]. Biological weapons pose the most significant terrorism threat. They are relatively easy to produce and could result in deaths comparable to nuclear weapons [4].

Ebola hemorrhagic fever is an acute viral syndrome that leads to fever and an ensuing bleeding diathesis that is marked by high mortality in human and nonhuman primates. It is caused by Ebola virus, a lipid-enveloped, negative strand RNA virus that belongs to the viral family Filoviridae [5]. Case fatalities range historically between 53 and 90% [6].

Ebola virus infection in human causes severe disease for which there is presently no vaccine or other treatment [7]. Vaccination strategies based on single or multiple filovirus proteins have examined the protective capacity of Glycoprotein (GP) alone [8–15] or in association with Nucleoprotein (NP) or Viral protein (VP) [16–18]. The vaccine potential of other internal structural proteins has been investigated as well. VP24, VP30, and VP35, expressed by using recombinant venezuelan equine encephalitis vectors, elicit some immunological response in rodents, but no single VP could confer complete defence against lethal Ebola virus and Marburg virus challenges [19, 20].

VP40 plays an important role in virus assembly and budding, VP40 is the most abundant protein in viral particles; it is located under the viral bilayer to make structural integrity of the particles. VP40 matrix protein assembles and budding process take place at the plasma membrane, which requires lipid raft micro domains [21, 22]. VP40 is active not only in the lipid bilayer during the assembly process but also plays an important role either in viral or host cell RNA metabolism during its replication [23]. C-terminal domain of VP40 is required for membrane association [24, 25].

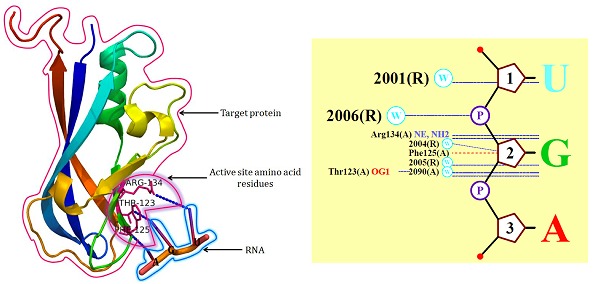

Crystal structure of VP40 is an octamer, forms a pore-like structure and binding with RNA. The protein-RNA interface is stabilized by 140 amino acids residues of VP40 (including Thr123, Phe125 and Arg134 amino acid residues of a fragment of N-terminal domain) and UGA of RNA. The monomeric structure having two domains, N-terminal and C-terminal domains are involved in membrane association. RNA binding pocket could serve as a target for antiviral drug development [23].

Matrix protein and Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) interactions have been reported for a number of enveloped viruses [26–29]. Matrix protein interacts with RNA in Thr123, Phe125 and Arg134 residues; these are the most important residues close to the interface of the N- and C-terminal domains in the monomeric conformation; which might implicate them in the transition process. VP40 octameric structure shows that the interfaces of the dimeric subunit are similar to the interface occupied by the N-and C-terminal domains in the closed conformation [30]. The aim of this study was to identify potential lead compounds against VP40 protein target using high throughput virtual screening and molecular docking approaches and subjecting the identified molecules for ADME analysis.

Methodology

All the computational analysis were carried out using Schrodinger suite version 9 [31]. Distance measuring and image capturing were carried out using PyMol viewer version 1.3 [32].

Protein structure:

X-ray crystal structure of the matrix protein VP40 at 1.6 Å resolution was retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1H2C) [33]. Protein preparation wizard was used in Schrodinger 2010. All the water molecules and RNA were removed from the original crystal structure before protein preparation process, to analyse the structure and the bond order assigned, hydrogen atoms were added and the geometry of all the hetero groups were corrected. Hydrogen bonds assignment tool was used to optimize the hydrogen bond network. Finally, impref optimized the position of hydrogen bonds and keeping all the atoms in place. Energy minimization was carried out using default constraint of the 0.3 Å of RMSD and the OPLS_2005 force field.

Receptor grid preparation:

Grids were generated by Receptor Grid Generation panel which defines receptor structure by excluding any other cocrystallized ligand that may be present, settle on the position and size of the active site was represented by receptor grids. Grid point's level for x, y, z axis (3.68, 19.15, 25.87) with in the grid parameters Thr123, Phe125 & Arg134 amino acid residues were present and grid generation was performed using OPLS_2005.

Compound database:

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) database contains more than one lakh of compounds and Asinex database contains 202122 structures, assembled from the collection of 1115000 Asinex platinum compounds. Single low energy conformation is stored for each of the 202122 database entries. 3D database entries were created following AsinexDB_Pt_flex, AsinexDB_flex and AsinexDB - Lipinski-filtered were cleaned using LigPrep, with expansion of stereo centers whose chirality was unspecified. This small molecules collection contains a high percentage of drug like compounds [34, 35].

High throughput virtual screening:

Virtual screening is the easiest method to identify and rank potential drug candidates from a database of compounds. Based on the active site of VP40, high throughput virtual screening was performed using the Traditional Chinese medicine and Asinex compound database. The compounds were subjected to Glide based three-tiered docking strategy in which all the compounds were docked by three stages of the docking protocol, High Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS), Standard Precision (SP) and Extra precision (XP). First stage of HTVS docking screens the ligands that are retrieved and all the screened compounds are passed on to the second stage of SP docking. The SP resultant compounds were then docked using more accurate and computationally intensive XP mode. Based on the glide score and glide energy, the protocol gives the leads in XP descriptor. Glide module of the XP visualizer analyses the specific interactions. Glide includes ligand-protein interaction energies, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, internal energy, π-π stacking interactions and root mean square deviation (RMSD) and desolvation.

ADME screening:

ADME properties were calculated using molsoft [36]. Molsoft predicts two properties, physically significant and pharmaceutically relevant descriptors. Molsoft program will predict the properties of the molecules, with a detailed analysis of principal descriptors and physiochemical properties. It also evaluates the acceptability of the analogues based on Lipinski's rule of 5 [37], which are essential for drug-like pharmacokinetic profile while using rational drug design.

Results & Discussion

The interaction between VP40 and RNA taken from PDBsum [38] is shown in (Figure 1), about 4Å encircled around the ligand (RNA) was considered for screening. The RNA interaction stabilizes the octameric structure, RNA acts solely as an adaptor in order to generate a confirmation of VP40 suitable to interact with an unknown regulatory protein, active in the virus life cycle. The octameric structure of VP40 provides the frame work for a precise functional analysis, additionally RNA presence of octameric structure VP40 infecting cells of RNA binding pocket is a new target for antiviral drug development. It has been learnt that there are three residues which are essential for RNA binding namely; Thr123, Phe125, Arg134. Three different levels of docking and scoring processes were used for this study starting with HTVS, followed by SP and finally with XP. VP40 protein target was docked with ASINEX and TCM database using Glide. HTVS selected 16,747 compounds based on Glide score. SP docking filtered by another Glide score criteria value (Glide score < -4.0 Kcal/mol) which led to 249 ligands. The final docking with XP ranked the 249 best-scored compounds and ten compounds were selected based on the Glide score. The ID's and H-Bond interactions of the top ten scored compounds are shown in (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Amino acids involved in RNA-VP40 interactions.

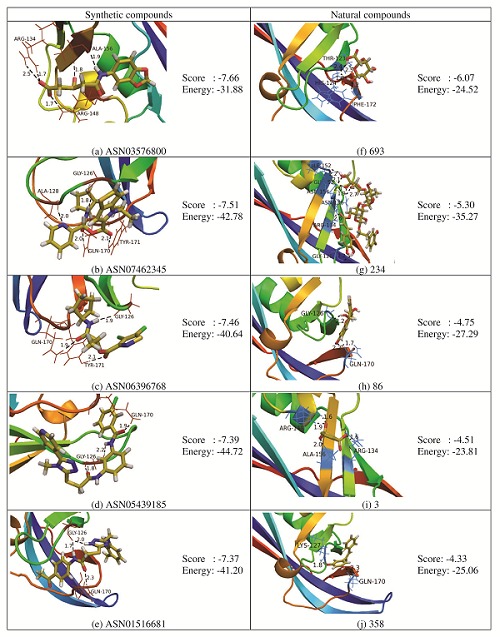

Figure 2.

Docking interaction of Lead compounds with matrix protein VP40 and their corresponding glide score and energy.

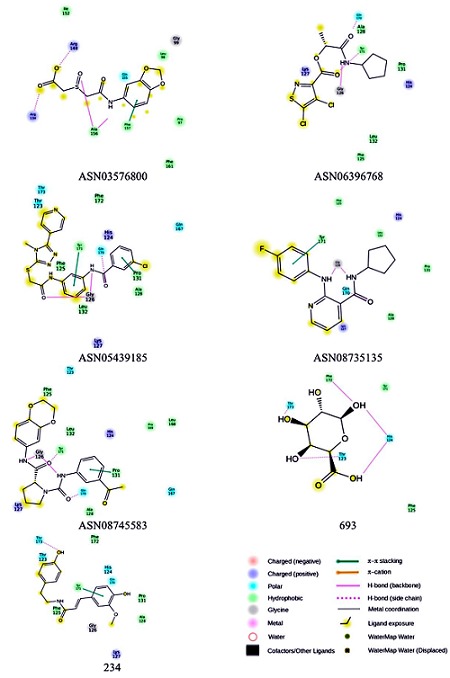

Docking results showed that ASN03576800, ASN06396768, ASN05439185, ASN08735135, ASN08745583 from ASINEX database and 693, 234 from TCM database ligands occupy the RNA binding region of VP40 with the almost similar conformation with a glide score of -7.66, -7.46, -7.39, -7.11, -6.95, -6.07 and -5.30 Kcal/mol. Maestro Ligand interaction 2-D diagram was used to understand the in-depth interaction pattern to the ligands and VP40.

Binding mode of ASN03576800 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

Docking results showed that the ligand ASN03576800 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -7.66 and the Glide energy is -31.88 Kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue Ala156 and side chain amino acid residues Arg134 and Arg148. Phe157 was involved in the π-π stacking interaction with ligand. Four hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues Pro97, Leu98, Ile152, Phe161 and one polar interaction with the amino acid residue Gln155 in the RNA binding region of VP40 were observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Docked conformation of ASN03576800, ASN06396768, ASN05439185, ASN08735135, ASN08745583, 693 and 234 compounds in the RNA binding region of VP40.

Binding mode of ASN06396768 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

The ligand ASN06396768 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -7.46 and the Glide energy is -40.64 Kcal/mol. Hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue Gly126 and side chain amino acid residues Gln170 and Tyr171. Two hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues Pro131 and Ala128, and two positive charge interactions with Lys127 and His124 residues were observed (Figure 3).

Binding mode of ASN05439185 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

Docking results showed that the ligand ASN05439185 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -7.39 and the Glide energy is -44.72 Kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue Gly126 and side chain amino acid residue Gln170. Pro131 and Tyr171 involved in the π-π stacking interaction with the ligand. Four hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues Phe125, Ala128, Leu132 and Phe172 formed and polar interactions with the residues Thr123, Thr173 and Gln167. His124 and Lys127 formed positive charge interaction with ligand were observed (Figure 3).

Binding mode of ASN08735135 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

The ligand ASN08735135 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -7.11 and the Glide energy is -33.52 Kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue Gly126 and side chain amino acid residue Gln170. Tyr171 was involved in the π-π stacking interaction with the ligand. Phe125, Ala128, Pro131 and Leu132 formed hydrophobic interactions. His124 and Lys127 formed positive charge interactions with the ligand (Figure 3).

Binding mode of ASN08745583 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

The ligand ASN08745583 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -6.95 and the Glide energy is -42.55 Kcal/mol. Two hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue Gly126 and side chain amino acid residues Gln170 and Tyr171. Pro131 was involved in the π-π stacking interaction with the ligand. Five hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues Pro125, Ala128, Leu132, Leu168 and Pro169 were observed. Thr123 and Gln167 formed polar interactions and His124 and Lys127 formed the positive charge interactions with the ligand (Figure 3).

Binding mode of 693 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

Docking results showed that the ligand 693 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -6.07 and the Glide energy is -24.52 Kcal/mol. Five hydrogen bond interactions were identified with the backbone amino acid residue His124, Phe172 and side chain amino acid residue Thr123, Thr173. Phe125 and Tyr171 involved in the hydrophobic interaction with the ligand were observed (Figure 3).

Binding mode of 234 with the RNA binding region of VP40:

The ligand 234 occupied the RNA binding region of VP40 with a Glide score of -5.30 and the Glide energy is -35.27 Kcal/mol. One hydrogen bond interaction was identified with the side chain amino acid residue Thr173. Tyr171 was involved in the π- π stacking interaction with the ligand. Four hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues Phe125, Ala128, Pro131 and Phe172 were observed. Thr123, His124 and Gln170 formed polar interactions and Lys127 formed the positive charge interactions with the ligand (Figure 3).

The Ebola virus matrix protein VP40 associates with the assembly and budding process of enveloped viruses. VP40 contains two short sequence motifs (PPXY and PTAP) at its Nterminus whose presence have been implicated in virus particle release by interacting with cellular factors [23]. Matrix protein/RNP interactions have been reported for a number of enveloped viruses [26–29]. This process may generally involve interactions with viral RNA, such as corona virus M/mRNA1 recognition, which seems to be crucial for the M-NP association [39]. In addition, other studies implicated that the matrix proteins interfere with the cellular RNA metabolism [40, 41]. The dimer interface is stabilized by the interaction with ssRNA segment. The RNA mainly interacts with Arg134, Phe125 [23]. Arg134, Phe125 are the most important residues in the interaction and both are positioned next to each other and exposed close to the interface of the N-terminal domains in the monomeric conformation it might play them in the transition process. VP40 is a monomer in solution and it is containing two domains [30] and interaction with cellular budding factors [42–44] with C-terminal domain is instrumental for membrane association [25].

The compound FGI106, (Quino[8,7-h]quinoline- 1,7diamine,N,N-bis[3-(dimethylamino) propyl]-3,9-dimethyltetrahydrochloride) is reported as an inhibitor of Ebola virus replication without its specificity towards any of the potent target proteins [45, 46]. Ribavirins, which function as host and virus proteins, aryl methyldiene rhodanine derivative, termed “LJ001”, LJ001 intercalates into lipid bilayers, probably via the phenyl ring on its nonpolar end and positions the pharmacophore on the opposite polar end for activity. It is possible that an activation of the thioxo functionality occurs to cause damage in the lipid environment of the virus or cell. The actual efficacy of LJ001 for the prophylactic, postexposure, or therapeutic treatment of enveloped viral diseases probably will depend on formulation and pharmacological considerations as well as on the pathogenic profile of the virus [47]. SAH hydrolase inhibitor is to boost the immune response by stimulating interferon production. SAH inhibitors induced IFN- α given immediately reduce the Ebola and Zaire resulted only in a 2-day in the onset of illness and death [48]. Cyanovirin-N (CV-N) is a protein that is produced by cyanobacteria and it binds to high-mannose oligosaccharides, treatment for 6 days delayed the onset of illness and prolonged the time of survival – however, it failed to protect mice from death [49].

Predicted ADME properties:

Physically significant descriptors and pharmaceutically relevant properties of the ten lead compounds were analyzed using molsoft. Molecular weight, log P Octanol/water partition coefficient, H-bond donors, H-bond acceptors, Mol Log S and their positions according to Lipinski's rule of five were included as significant descriptors Table 1 (see supplementary material). The ten selected compounds were in the acceptable range of Lipinski's rule of five, indicating their potential for use as druglike molecules [37].

Conclusions

Since, no potent inhibitors are available against Ebola virus, molecular docking studies were performed to identify small molecule inhibitors of the lipid bilayer interaction during the viral assembly and budding process. HTVS screened compounds from ASINEX and TCM database were subjected to SP docking which resulted in 159 compounds. These compounds were further taken for XP docking. Using XP docking, based on the glide score, glide energy and H-bond interactions with the amino acid residues of RNA binding site, 10 compounds were shortlisted. ADME properties test of the hit molecules indicated that all the 10 compounds were within the acceptable range of Lipinski's Rule of Five. This suggests that the ten compounds could be potential inhibitors of the VP40 matrix protein. Out of the ten compounds, ASN03576800 (2-[2- (1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylamino)-2-oxoethyl]sulfinylacetic acid) has a good glide score and glide energy (-7.46 & -50.30 kcal/mol). The ligand has a good contact with the specific amino acid residue Arg134 and other residues like Gly126 and Thr173 with the hydrogen bond distances of 2.0, 1.9 and 2.1 Å. The ligand ASN03576800 could be a potent inhibitor for Ebola virus matrix protein VP40 in process of viral assembly and budding process.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

TT acknowledges SRM University and DRDO, India for their financial support.

Footnotes

Citation:Tamilvanan & Hopper, Bioinformation 9(6): 286-292 (2013)

References

- 1.Borio L, et al. JAMA. 2002;287:2391. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray M, et al. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas RM, et al. ASM News. 1998;64:383. [Google Scholar]

- 4. http://www.csis-scrs.gc.ca/eng/miscdocs/tabintr_e.html.

- 5.Adrian M, et al. Biol Res Nurs. 2003;4:268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Towner JS, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000212. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. www.physorg.com/news134840607.html.

- 8.Sullivan NJ, et al. Nature. 2000;408:605. doi: 10.1038/35046108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hevey M, et al. Vaccine. 2001;20:586. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao M, et al. J Virol. 2002;76:9176. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9176-9185.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riemenschneider J, et al. Vaccine. 2003;21:4071. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellquist-Riemenschneider JL, et al. Virus Res. 2003;92:187. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SM, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:786. doi: 10.1038/nm1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, et al. Vaccine. 2006a;24:2975. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D, et al. Virology. 2006B;353:324. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swenson DL, et al. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:27. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warfield KL, et al. Vaccine. 2004;22:3495. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swenson DL, et al. Vaccine. 2005;23:303. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hevey M, et al. Virology. 1998;251:28. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson JA, et al. Virology. 2001;286:384. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geisbert TW, et al. Virus Res. 1995;39:129. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bavari S, et al. J Exp Med. 2002;195:593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomis-Rüth FX, et al. Structure. 2003;11:423. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruigrok RW, et al. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:103. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timmins J, et al. Virology. 2001;283:1. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaptur PE, et al. J Virol. 1991;65:1057. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1057-1065.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coronel EC, et al. J Virol. 2001;75:1117. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1117-1123.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stricker R, et al. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1031. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt AP, et al. J Virol. 2002;76:3952. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3952-3964.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dessen A, et al. EMBO J. 2000;19:4228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. http://www.schrodinger.com.

- 32. http://www.pymol.org.

- 33.Berman HM, et al. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:899. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. http://tcm.cmu.edu.tw/

- 35. http://www.asinex.com.

- 36. http://www.molsoft.com/

- 37.Lipinski CA, et al. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskowski RA, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narayanan K, et al. J Virol. 2000;74:8127. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8127-8134.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed M, et al. J Virol. 1998;72:8413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8413-8419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Von KC, et al. E Mol Cell. 2000;6:1243. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harty RN, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:13871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250277297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timmins J, et al. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:493. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin-Serrano J, et al. Nat Med. 2001;7:1313. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arthur JG, et al. Antiviral chemistry & chemotherapy. 2005;16:283. doi: 10.1177/095632020501600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aman MJ, et al. Antiviral Research. 2009;83:245. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mike CW, et al. PNAS. 2009;107:3157. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jahrling PB, et al. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:S224. doi: 10.1086/514310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrientos LG, et al. Antiviral Research. 2003;58:47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.