Abstract

Purpose

Recurrent or advanced stage cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is difficult to treat and available therapies have a high failure rate. Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy (EGFR) is associated with a facial rash that may potentiate radiation related cutaneous toxicities. The objective of this clinical trial was to assess the toxicity profile of erlotinib therapy combined with postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with advanced cSCC.

Methods

This study is a single-arm, prospective phase I open-label study of erlotinib with radiation therapy (XRT) to treat 15 patients with advanced cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Toxicity data were summarized and survival was analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

The majority of patients were male (87%) and presented with T4 disease (93%). The most common toxicity attributed to erlotinib was a grade 2–3 dermatologic reaction occurring in 100% of the patients, followed by mucositis (87%). Diarrhea occurred in 20% of the patients. The two year recurrence rate was 26.7% and mean time to cancer recurrence was 10.5 months. Two year overall survival was 65% and disease free survival was 60%.

Conclusions

Erlotinib and radiation therapy had an acceptable toxicity profile in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. The disease-free survival in this cohort was comparable to historical controls.

Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is one of the most common malignancies in the US with an incidence of 100 cases per 100,000 individuals. There has been an alarming increase in the incidence of cSCC over the past 20 years which may be due in part to increased detection but also increased sun exposure may be a factor1. The most common location for primary cutaneous SCCs is the head and neck, which represents 80–90% of lesions. These sites are also frequently the site of aggressive cSCCs.1,2 Advanced cSCC disease is associated with an overall poor prognosis, increased risk for metastasis, and high rate of recurrence. In a recent study of Stage III cSCC, the two year recurrence rate was 40%, and the overall 2-year survival for advanced stage lesions (T3-4) was approximately 50%.2 Recurrent cSCCs have metastatic rates that range from 25%–45% depending on the location, with ear and lip tumors having the highest metastatic potential1. Treatment of locally advanced or locoregional disease has consisted of more aggressive surgical resection with the addition of postoperative radiotherapy. In other cancer types with similar histological features, studies have shown some survival benefit when conventional or targeted chemotherapeutics have been added to radiotherapy as a radiosensitizer3.

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays an important role in the proliferation and survival of most cancer cell populations. Overexpression and growth signaling properties of EGFR have been demonstrated in mucosal head and neck SCC, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer. Over the past decade anti-EGFR therapy has been successfully applied to these tumor types as well as advanced cSCC. EGFR is thought to play a role in cSCC carcinogenesis, with some studies reporting an EGFR expression rate of 80–100%4. Erlotinib (Tarceva or OSI-774) is an inhibitor of EGFR that functions as a reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of the receptor’s intracellular tyrosine kinase which causes G1 cell cycle arrest, and results in reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis in preclinical studies. There have been limited reports that assess treatment in patients with advanced cSCC treated with either erlotinib or gefitinib, another EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI).5,6 EGFR TKIs have been evaluated as a combination treatment regime with chemoradiation in head and neck cancer.7,8 Because cSCCs have histological characteristics similar to head and neck cSCC and share high levels of EGFR expression9, it is likely that the combination of erlotinib with radiotherapy would potentially improve outcomes. However, radiotherapy in this setting necessarily results in significant cutaneous toxicity which may exacerbate follicular papulopustules commonly associated with EGFR therapies. To this end, we tested administration of erlotinib concurrently with radiotherapy after surgical resection in a single-arm, phase I study in advanced cSCC. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the safety and toxicity and as a secondary end point, determine the 2-year overall survival and time to recurrence.

Patients and Methods

This investigation was a single-institution, open-label, non-randomized, single-arm, phase I clinical trial. This study was approved by the Hospital Institutional Review Board. All patients signed the approved protocol and consent forms. Tumors were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines 7th edition. 10

Eligibility criteria

Patients were older than 19 years of age and had histologically proven stage III cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising from the head and neck. Immunocompromised patients and patients with a history of radiation to the affected area were excluded. Each patient had either T4 disease or histologically proven regional lymph node involvement. Patients were allowed to enroll after completion of the surgical resection contingent on concurrent erlotinib and radiation therapy beginning within 8 weeks of resection. Patients with prior non-cutaneous malignancies were not excluded unless they were less than two years from treatment. The following additional exclusion criteria were used: prior radiation therapy to the head neck, pregnant or lactating, history of head and neck mucosal cancers, or having a psychological condition where the patient was unable to understand the informed consent.

Treatment Regimen

The study design included a pre-treatment period with erlotinib (n=7) (150mg daily for 14 days) prior to surgical resection and concurrent erlotinib and radiotherapy following surgical resection. Patients underwent wide local excision and regional lymphadenectomy. However, patients with vertex lesions on scalp (n=2) or previously dissected lymphatic bed (n=7) did not undergo lymphadenectomy. Nine patients underwent composite resection and four had a parotidectomy. A selective neck dissection was performed in 10 patients. Surgical defects were reconstructed by primary closure or skin grafts (n=3), rotational flaps (n=1), or free flap transfer (n=11). Soft-tissue free flap reconstruction was performed using the radial forearm (n=5), latissimus (n=1), rectus (n=1), and anterolateral thigh (n=2) donor sites. In cases where bony reconstruction was required patients received an osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 (86.7) |

| Female | 2 (13.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 12 (80.0) |

| African American | 2 (13.3) |

| Asian | 1 (6.7) |

| Age (y), mean | 68.3 |

| T classification | |

| Tx | 1 (7.0) |

| T2 | 1 (7.0) |

| T4 | 13 (87.0) |

| N classification | |

| N0 | 7 (54.0) |

| N1 | 3 (20.0) |

| N2b | 5 (33.3) |

| Tumor site | |

| Scalp | 3 (20.0) |

| Lower lip | 3 (20.0) |

| Cheek/orbit | 2 (13.0) |

| Cheek/nose | 2 (13.0) |

| Parotid gland | 2 (13.0) |

| Ear | 1 (7.0) |

| Forehead | 1 (7.0) |

| Submandibular triangle | 1 (7.0) |

| Surgery type | |

| Parotidectomy | 4 (26.0) |

| Auriculectomy | 2 (13.0) |

| Orbital exoneration | 2 (13.0) |

| Complete resection | 9 (60.0) |

| Neck dissection | |

| Yes | 10 (67.0) |

| No | 5 (33.3) |

| Flap type | |

| Free flap | 11 (73.0) |

| Rotational flap | 1 (7.0) |

| None | 3 (20.0) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| ≤2 | 6 (40.0) |

| 2.1–3.9 | 5 (33.3) |

| ≥4 | 4 (27.0) |

| Tumor margins | |

| Negative | 9 (60.0) |

| Positive | 6 (40.0) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 3 (20.0) |

| Absent | 12 (80.0) |

| Extracapsular spread | |

| Present | 4 (27.0) |

| Absent | 11 (73.0) |

| Bone invasion | |

| Present | 3 (20.0) |

| Absent | 12 (80.0) |

Patients began erlotinib therapy 150mg a day concurrently with fractionated radiotherapy of 60– 66 Gy for 6 weeks within 8 weeks of resection. There was a mean of 26 days from surgical resection to radiotherapy start. All participants were followed for toxicities using NCI common toxicity criteria (v3.0). Treatment breaks or changes from the radiotherapy were avoided unless grade 3–4 toxicities developed. Participants were followed approximately every 3 months by members of the treatment team for a duration of 24 months. Seven patients missed 5 days or more of erlotinib therapy due to treatment toxicities with average of 8.7 days of treatment missed per patient. Five patients had an interruption in radiotherapy, with 3 of them secondary to treatment toxicity. Two interruptions were due to medical problems considered unrelated to the study treatment which included a myocardial infarction and syncope, and one patient needed re-simulation. Typically mucosal side effects were seen starting at week 3.

Dose limiting side effects of erlotinib (diarrhea and skin rash) were monitored and dose modifications were based on toxicity grade. Dose modifications were made in 50mg/day increments.

Biological Endpoints

Tumor biopsies were obtained at time of study enrollment for 5 patients at day zero and at the time of surgical resection (day 14) for patients receiving erlotinib pre-treatment when feasible. A total of 7 patients received treatment with erlotinib prior to resection. All patients had post-surgical therapy with erlotinib and radiotherapy. Assessment of paraffin-embedded tumor sections was done with routine H & E, CD31, Ki67, and bcl-2 staining. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed to examine the expression levels of EGFR, pEGFR, AKT, and pAKT as described previously and a manual scoring system was used. 4

Statistical Analysis

Adverse events were summarized by descriptive statistics (frequency, mean). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to evaluate overall survival and disease-free survival.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifteen patients were enrolled in the study between December of 2006 and June of 2009. Patient, clinical and tumor characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were 13 males and two females. Their median age was 68 years (range, 48–86 years). The majority of patients were Caucasian (80%); 13% were African American (both African American patients had disease arising from within a scar); and 7% Asian. Most patients presented with recurrent disease (80%) that failed previous surgical excision and the remainder had previously untreated disease (20%). Eight patients (53%) had local disease with the remaining presenting with local/regional disease (47%). Of the patients presenting with local/regional disease, eight had cervical lymph node metastases (n=8). Five patients had parotid metastases. For those patients with primary tumors (n=13), mean tumor size was 3.3 (±2.2) cm in largest dimension. The majority of primary lesions were classified as T4, with the exception of two patients who presented with regional metastatic disease (one staged as Tx and one as T2). Perineural invasion was present in 20% (n=3), extracapsular spread was seen in 27% (n=4/8 with cervical lymph nodes), and there was pathological evidence of bone invasion in 20% of patients (Table 1).

Adverse Events

The most commonly encountered side effect was dermatitis as all patients had either a grade 2 or 3 reaction with 47% of patients suffering from a grade 2 reaction and 53% experiencing a grade 3 reaction. Eleven patients (73%) were reported as having a grade 2–3 acneiform-type rash that was attributed to the erlotinib. Ten patients (67%) were reported as having a grade 2–3 dermatitis that was consistent with radiation-induced dermatitis. Patients with an intolerable grade 2–3 rash (n=3) received an erlotinib dose modification and oral antibiotics. The next most frequent toxicity was mucositis with 87% (n=13) experiencing a grade 2–3 reaction. Other grade 2–3 toxicities that were commonly reported in this study included esophagitis (40%) , fatigue(47%), nausea/vomiting (47%), dehydration(47%) , and diarrhea (20%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Side effect | Grade (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Dermatitis | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 |

| Radiation dermatitis | 3 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Tarceva dermatitis | 2 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 4 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Esophagitis | 2 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

Dose modifications occurred in 5 patients (33%). Seven patients missed 5 days or more of erlotinib therapy due to treatment toxicities with an average of 8.7 days missed per patient. Dose modifications were made for 5 of these patients and 2 discontinued therapy secondary to nausea and vomiting. Patients received dose modifications for the following severe side effects: rash (n=2), edema (n=1), dry mouth (n=1), and dehydration (n=1). One additional patient had an interruption in radiotherapy for 12 days, and this break was related to a myocardial infarction.

Overall Survival and Recurrence

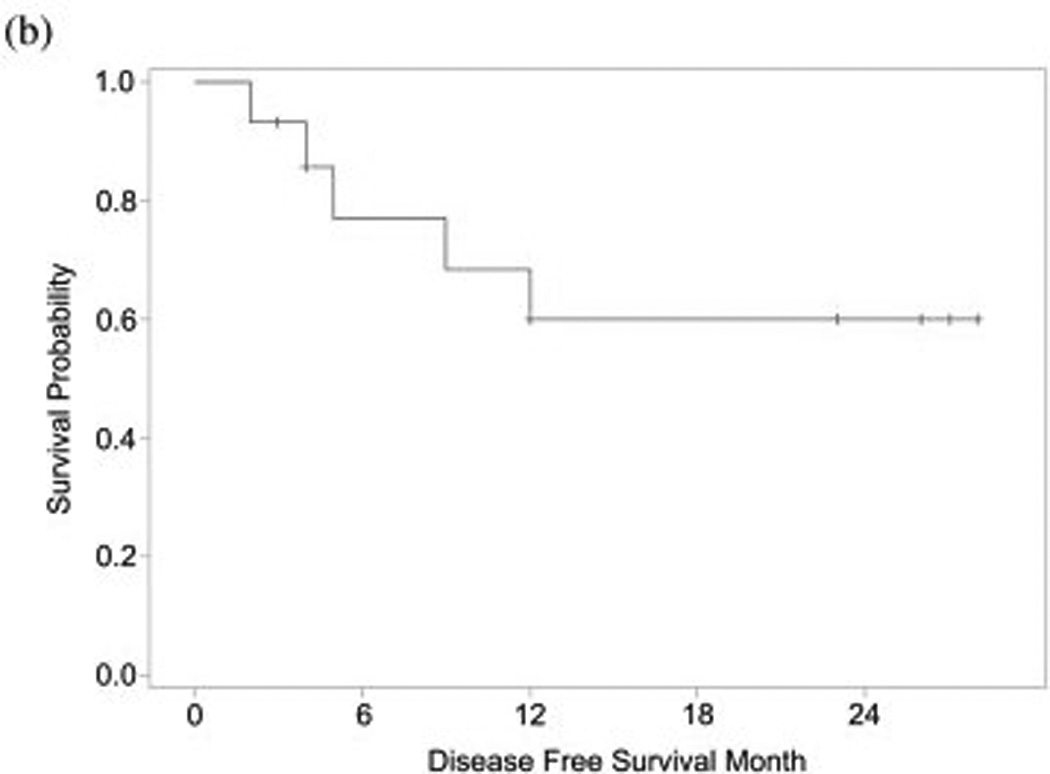

The mean follow-up time was 21.7 months and median time to cancer recurrence was 10.5 months (range, 1–14 months). The two-year recurrence rate was 26.7%. The one year survival was 83% and 2-year survival was 65%. The disease-free survival rate at 1-year was 73% and at 2-years was 60% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Overall and (b) disease-free survival for patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with erlotinib and radiation therapy.

Correlative data

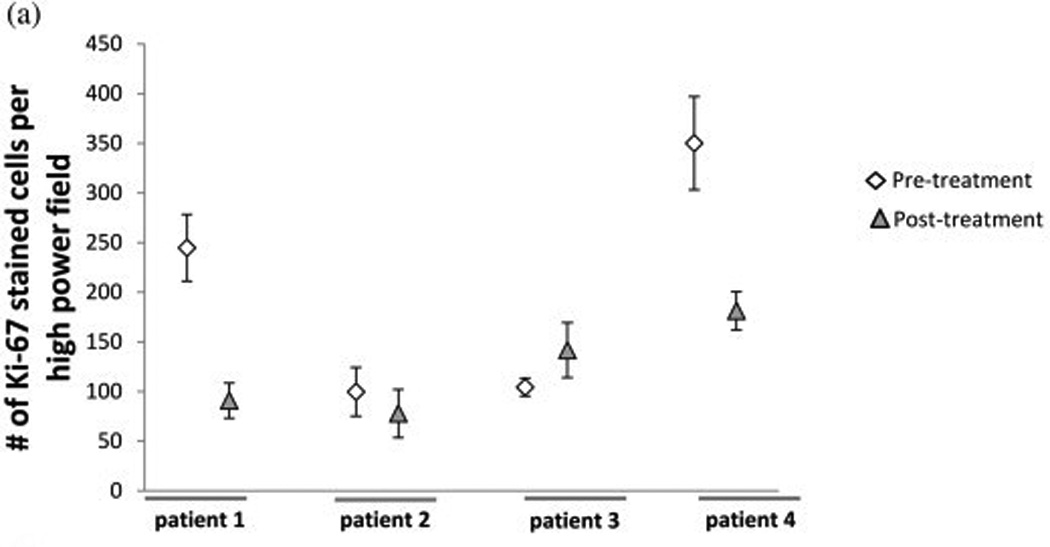

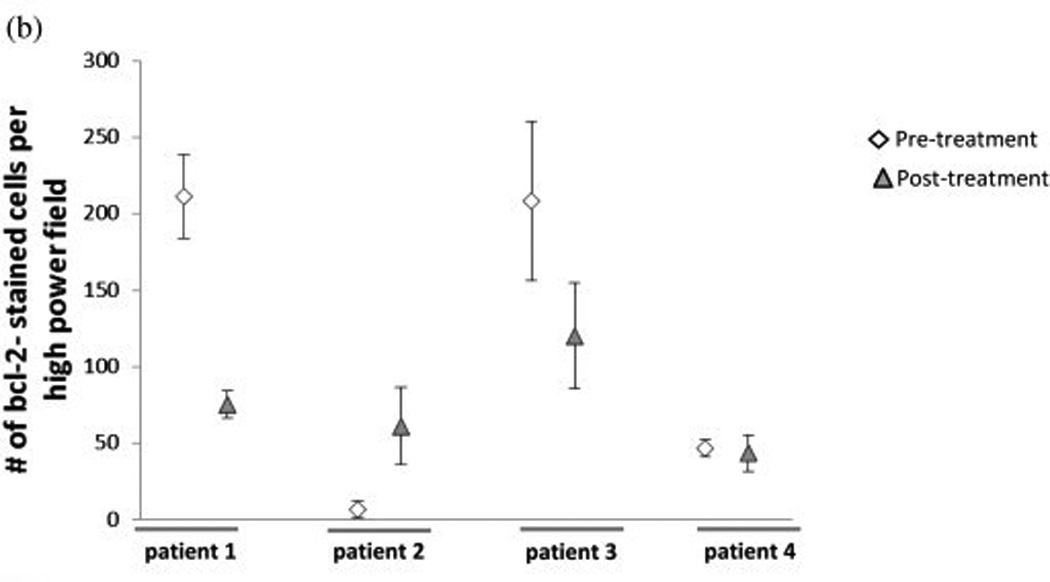

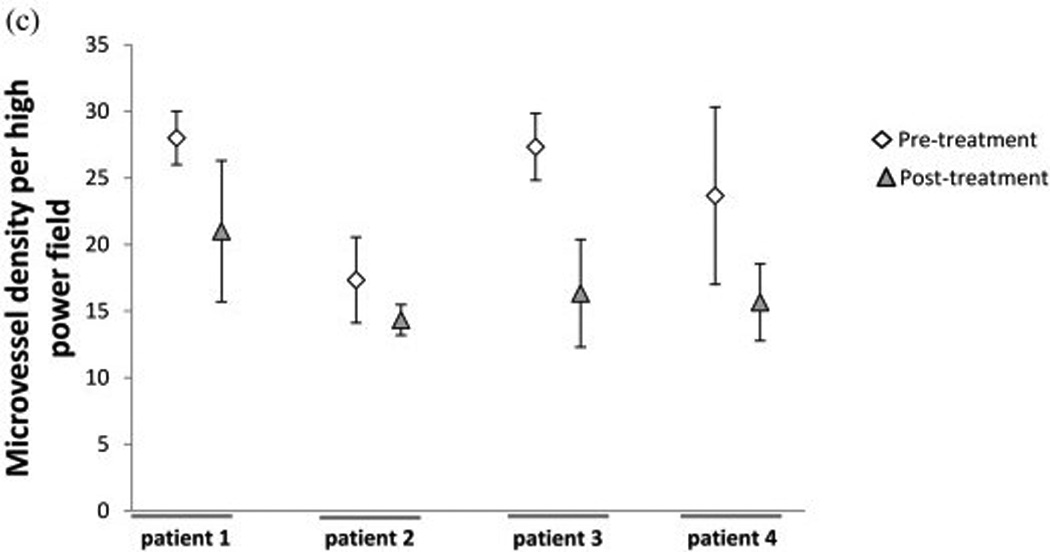

Four out of the seven patients that had pre-surgical tarceva treatment had adequate tissue samples for molecular analysis. Erlotinib pre-treatment and post-treatment samples were analyzed for ki67, CD31, and bcl-2 by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Of the four pre-treatment and post- treatment samples analyzed for ki67 staining there was a decrease of this marker in two patient samples after pre-treatment with erlotinib. There was no appreciable difference in the other two patients (Figure 2a). One patient with a decrease in ki67 also had a decrease in bcl2. One other patient had a decrease in bcl-2 staining following erlotinib treatment; one showed an increase in bcl-2 staining and the other exhibited no appreciable difference (Figure 2b). There was a decrease in microvessel density for all four patients following pre-treatment with erlotinib (Figure 2c). Immunofluorescent analysis was done to determine pre- and post-treatment EGFR, pEGFR, AKT, and pAKT expression. The correlative immunofluorescence findings are summarized in table 3. AKT, pAKT, and EGFR decreased across tumor after 14 days of therapy. However, no consistent change in pEGFR was detected.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis using (a)Ki67, (b)bcl-2, and (c)CD31 staining of patient slides before and after erlotinib treatment

Table 3.

Immunofluorescence staining

| Patient no. | EGFR | pEGFR | AKT | pAKT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| 1 | ++ | ++ | + | 0 | ++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| 2 | +++ | + | 0 | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| 3 | +++ | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| 4 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | +++ | + |

Abbreviation: EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor.

Discussion

This is the first description of an EGFR TKI combined with radiotherapy for advanced cSCC. Current treatment regimens following surgical resection of cSCC include postoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination. The ongoing TROG 05.01 is currently investigating the treatment of advanced head and neck cSCC in patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy versus patients receiving postoperative carboplatin and radiotherapy. Because radiotherapy for cutaneous cancer delivers results in significant dermal toxicity, there has been significant concern over additive toxicities associated with the acneiform rash commonly associated with EGFR therapies and often occurs in the same distribution as radiotherapy for head and neck cutaneous malignancies. This clinical trial demonstrated an acceptable toxicity profile using post-operative adjuvant erlotinib treatment in combination with radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. The most commonly encountered toxicities were dermatitis, mucositis and diarrhea. The two-year overall survival rate was 65% and the two-year disease-free survival rate was 60%. Following completion of the combination treatment regimen, 73% of patients did not have recurrence of their disease within two years.

It is important to note that although the margin positivity in our patients was high (40%), reports on cSCC margin positivity range from 6%–73% 2. The risk factors for patients with cSCC having positive margins include advance stage and location of disease. In a previous study on outcomes of patients with advanced cSCC we reported a margin positivity rate of 42% similar to what we found in the present study11.

EGFR TKIs given concurrently with radiotherapy have been studied in mucosal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) which has been considered to be biologically similar to cSCC.12 Several studies have investigated the tolerability and safety profile of a combined EGFR TKI and radiotherapy treatment regime in HNSCC. These show the addition of gefitinib to either radiotherapy or chemotherapy increases the incidence of grade 3 mucositis and diarrhea.13 We found similar results with the current study. The toxicity incidence of other studies using this same combination treatment regime is summarized in Table 4. The toxicity associated with combined treatment with erlotinib remains similar to that of other cutaneous lesions of the head and neck. Given that the endpoint of this study was safety and toxicity, rather than survival, it was logical to include this patient group to expand the numbers of patients that would be at risk for cutaneous toxicity associated with combined eroltinib and radiation.

Table 4.

EGFR TKI + radiation therapy treatment for HNSCC

| Study (reference) | Treatment side effect (grade: percentage) | Survival (percentage at 2 y) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatitis | Mucositis | Diarrhea | Overall | Progression-free | ||

| Hainsworth (11) | 3: 27 | 3: 16 | 76 | 58 | ||

| Cohen (6) | Radiation | EGFR | 80 | 77 | ||

| 2: 38 | 2: 14 | 2: 14 | ||||

| 3: 29 | 3: 4 | 3: 75 | ||||

| 4: 4 | 4: 0 | |||||

| Kao (22) | Radiation | EGFR | 55* | 37 | ||

| 2: 64 | 2: 50 | 2: 57 | 2: 7 | |||

| 3: 7 | 3: 7 | 3: 7 | 3: 0 | |||

| 4: 0 | 4: 0 | 4: 0 | 4: 0 | |||

| Chen (23) | Radiation | EGFR | 80 | 65 | ||

| 2: 30 | 2: 22 | 2: 35 | 2: 26 | |||

| 3: 13 | 3: 0 | 3: 52 | 3: 13 | |||

| 4: 0 | 4: 0 | 4: 4 | 4: 0 | |||

| Current study | Radiation | Tarceva | 65 | 60 | ||

| 2: 33 | 2: 33 | 2: 47 | 2: 13 | |||

| 3: 33 | 3: 33 | 3: 40 | 3: 7 | |||

| 4: 0 | 4: 0 | 4: 0 | 4: 0 | |||

Abbreviations: EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; HNSCC = head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma; TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Although there are several studies investigating this treatment regimen in HNSCC, there is limited data evaluating the efficacy and safety as well as treatment response with anti-EGFR inhibitors alone in cutaneous SCC and none on combined treatment with radiotherapy14. Addressing toxicity of these agents is important because they have overlapping cutaneous toxicity profiles. There have been some small case studies reporting a positive response in patients with advanced cSCC treated with EGFR TKIs (gefitinib5 or erlotinib6) and recently there was a prospective study published that examined the efficacy and tolerability of gefitinib monotherapy for cSCC.14 This study showed that gefitinib was well tolerated and demonstrated a response rate of 18% (CR) and 27% (PR). This study also showed that 23% of patients were taken off the study for treatment related side adverse events, which is consistent with our data. This is the only published clinical trial of treatment of cSCC with EGFR TKIs and currently to our knowledge there is no data on combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for these patients.

Targeted EGFR therapies result in cutaneous toxicities that have some overlap with radiotherapy. Anti-EGFR therapy is commonly associated with cutaneous toxicities as EGFR is found to be highly expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis and hair follicles.15 The most common cutaneous toxicities reported include follicular eruptions, alopecia, and fissures on palms and soles of patients undergoing treatment. In our study, the most common side effect was a rash, with a grade 2–3 rash appearing in 100% of patients with 33% of patients experiencing a grade 3 radiation-induced dermatitis and 33% experiencing a grade 3 erlotinib induced rash. This is consistent with toxicity of erlotinib (150mg/day) administered as monotherapy, which has cutaneous toxicities ranging from 60%–79%.16,17 It has been reported that the efficacy of cetuximab correlates with the skin toxicity. Rash is reported as an indicator of clinical benefit; however we found no correlation between the grade of tarceva rash and clinical outcome.14,17 Radiotherapy treatment alone induces mucositis, and dermatitis in the affected field. The incidence of grade 3 dermatitis at 60–66 cGy used in this trial was as expected in 6–52% range.18–20 There were 33% patients with treatment breaks secondary to radiation toxicity were in this study in comparison to the 8–29% reported in the literature from radiotherapy treatment alone.20

In previous clinical trials with single agent erlotinib treatments the most commonly observed adverse events were rash, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, stomatitis, vomiting and headache.14,17 The dose limiting side effects of erlotinib are known to be diarrhea and skin rash.16 In the current study, 100% of patients suffered a grade 2–3 cutaneous reaction and the next highest toxicity was mucositis (87%) followed by fatigue (47%), nausea/vomiting (47%), and dehydration (47%). The incidence of grade 3 mucositis in the current study was 60%, a percentage that is higher than that usually reported for radiotherapy alone (20–52%).19,20 Similarly, we had 9 patients (60%) with high-grade esophagitis, a percentage that is higher than that reported for radiotherapy alone which usually ranges from 20– 30%.18,20 Hair loss is also a commonly encountered adverse side effect of anti-EGFR therapy and radiotherapy and we did not observe significant changes.16 Fissures have been demonstrated to be a side effect of cetuximab and erlotinib therapy with some studies reporting an incidence of up to 30% in patients, and paronychia has been observed in up to 40% of patients undergoing anti-EGFR therapy.16 No patients experienced painful fissures or paronychia.

EGFR overexpression has been associated with a worse prognosis and no correlation has been proved between EFGR expression and treatment response.21 We were able to do EFGR, pEGFR, AKT, and pAKT immunofluorescent analysis on 4 patient samples before and after treatment. We saw changes consistent with EGFR down regulation. Immunohistochemistry showed that there was a decrease in microvessel density in all 4 patients. There was no change in the pre- and post-treatment analysis of BCL2. Molecular correlative data in the current study is very limited and does not provide an opportunity to make any conclusions, however, the variability of the available results are consistent with previous reports that do not identify consistent pathway down-regulation.4 Even though the number of patient samples available to do the correlative studies was low, it is possible that with more samples and patients we could have identified a marker for high-risk patients, which is population in which we would expand this study.

The role of EGFR inhibitors combined with radiotherapy has been investigated in several cancer types and as a single agent in the treatment of advanced cSCC. It has been shown that treatment with EGFR inhibitors soon after surgery can inhibit the repopulation of cells without impairing wound healing.22 Radiotherapy plus cetuximab has been proven effective at treating SCC of the head and neck.19 Cetuximab has also been shown to be effective as single agent therapy in the treatment of refractory skin cancer.23 However, we are the first to report on the combined use of erlotinib and radiotherapy for cSCC. Despite concern that erlotinib has significant cutaneous toxicities that would compound by dermal radiation targeting; our data on combination treatment in stage III and recurrent cSCC suggests that postoperative radiotherapy and erlotinib in advanced cSCC has an acceptable toxicity profile. Our overall survival rate was comparable to our historical controls and our disease-free survival was higher than expected when compared to our historical controls.2

Footnotes

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by OSI Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 29;344(13):975–983. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean NR, Sweeny L, Magnuson JS, et al. Outcomes of recurrent head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of skin cancer. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/972497. 972497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann M, Krause M. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in radiotherapy: radiobiological mechanisms, preclinical and clinical results. Radiother Oncol. 2004 Sep;72(3):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeny L, Dean NR, Magnuson JS, et al. EGFR expression in advanced head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck. 2011 Jul 7; doi: 10.1002/hed.21802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltaci M, Fritsch P, Weber F, et al. Treatment with gefitinib (ZD 1839) in a patient with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Jul;153(1):234–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WL R. Squamous carcinoma of the skin responding to erlotinib: Three cases 2007; ASCO Annual meeting; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen EE, Haraf DJ, Kunnavakkam R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinib added to chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jul 10;28(20):3336–3343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saarilahti K, Bono P, Kajanti M, et al. Phase II prospective trial of gefitinib given concurrently with cisplatin and radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jun;39(3):269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeny L, Dean NR, Magnuson JS, et al. EGFR expression in advanced head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck. 2012 May;34(5):681–686. doi: 10.1002/hed.21802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lardaro T, Shea SM, Sharfman W, Liegeois N, Sober AJ. Improvements in the staging of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Aug;17(8):1979–1980. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirshams M, Razzaghi M, Noormohammadpour P, Naraghi Z, Kamyab K, Sabouri Rad S. Incidence of incomplete excision in surgically treated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and identification of the related risk factors. Acta medica Iranica. 2011;49(12):806–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peereboom DM, Shepard DR, Ahluwalia MS, et al. Phase II trial of erlotinib with temozolomide and radiation in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2010 May;98(1):93–99. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Burris HA, 3rd, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy/gefitinib followed by concurrent chemotherapy/radiation therapy/gefitinib for patients with locally advanced squamous carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2009 May 15;115(10):2138–2146. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis CM, Glisson BS, Feng L, et al. A Phase II Study of Gefitinib for Aggressive Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Jan 18; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li T, Perez-Soler R. Skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2009 Apr;4(2):107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11523-009-0114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe E, Garcia Muret MP, Marcuello E, Capdevila J, Pallares C, Alomar A. Description and management of cutaneous side effects during cetuximab or erlotinib treatments: a prospective study of 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Sep;55(3):429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarwala SS, Siu LL. Multicenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 1;22(1):77–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006 Feb 9;354(6):567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A, et al. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: first report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000 Aug 1;48(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veness MJ. Treatment recommendations in patients diagnosed with high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Australas Radiol. 2005 Oct;49(5):365–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano D, Gule MK, Rosenthal DI, et al. Early postoperative epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition: Safety and effectiveness in inhibiting microscopic residual of oral squamous cell carcinoma in vivo. Head Neck. 2012 Feb 24; doi: 10.1002/hed.22961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalapurakal SJ, Malone J, Robbins KT, Buescher L, Godwin J, Rao K. Cetuximab in refractory skin cancer treatment. J Cancer. 2012;3:257–261. doi: 10.7150/jca.3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]