Abstract

Background

Very little is known about patient-family communication during critical illness and mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU), including the use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools and strategies during patient-family communication.

Objectives

The study objectives were to identify (1) which AAC tools families use with nonspeaking ICU patients and how they are used, and (2) what families and nurses say about patient-family communication with nonspeaking patients in the ICU.

Methods

A qualitative secondary analysis was conducted of existing data from a clinical trial testing interventions to improve nurse-patient communication in the ICU. Narrative study data (field notes, intervention logs, nurse interviews) from 127 critically ill adults were reviewed for evidence of family involvement with AAC tools. Qualitative content analysis was applied for thematic description of family and nurse accounts of patient-family communication.

Results

Family involvement with AAC tools was evident in 44% (n= 41/93) of the patients completing the parent study protocol. Spouses/significant others communicated with patients most often. Writing was the most frequently used tool. Main themes describing patient-family communication included: (1) Families as unprepared and unaware; (2) Family perceptions of communication effectiveness; (3) Nurses deferring to or guiding patient-family communication; (4) Patient communication characteristics; and (5) Family experience and interest with AAC tools.

Conclusions

Families are typically unprepared for the communication challenges of critical illness, and often “on their own” in confronting them. Assessment by skilled bedside clinicians can reveal patient communication potential and facilitate useful AAC tools and strategies for patients and families.

Keywords: critical care, family communication, patient communication, communication difficulty, augmentative and alternative communication

. . . my brother died in ICU at age 49 after a prolonged intubation. I know there were many things he tried to communicate through his eyes and the “mouthing of words” but was not successful. He was unable to use his hands and would often become frustrated at his inability to convey what he was trying to communicate. He left 2 teenage children and I often wonder what he would have said to them. [Email from a bereaved family member]

Family members are frequently described as communication partners and spokespersons for ICU patients who are unable to speak due to their need for mechanical ventilation (MV) and respiratory tract intubation.1–6 Yet as the e-mail note above so poignantly illustrates, communication impairment and communication difficulty are sources of distress for family members of critically ill patients.1, 2, 7

Supportive interpersonal interaction with family members can be therapeutic for ICU patients who are unable to speak8, 9 and may ameliorate the stress and trauma experienced by some family members during and after ICU hospitalization. Yet, ICU patients and their families often must overcome significant communication challenges. We know very little about how ICU patients and family members communicate and whether families are comfortable and proficient with the spectrum of augmentative and alternative communication tools and strategies. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) refers to all forms of communication, other than oral speech, that are used to express messages. AAC tools include equipment and aids such as writing implements, alphabet or picture communication boards, or electronic communication devices.10 This paper presents results of a qualitative content analysis of data from the parent study, a clinical trial testing interventions to improve nurse-patient communication in the ICU.11

Families commonly express feelings of loss, dismay, and frustration with the critically ill patient’s loss of voice,7 and prior qualitative research suggests that existing modes of communication between ICU patients and their families are insufficient and unsatisfying.1, 2,5,12, 13 Although nurses routinely advise families to speak to and encourage ICU patients,4, 14, 15 the involvement of families in assisted communication strategies with nonspeaking ICU patients has not been systematically investigated. In studies of family bedside presence in the trauma emergency room and neurological ICU settings4, 14 family members were noted to model their verbal responses to the patient in tone and content after the nurse. In our earlier study of weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU,15 20% (6/30) of the families were observed to initiate assistive communication tools such as writing tablets or “magic slates,” “homemade” communication boards, electronic email device, and/or individualized signals on their own (unpublished data). Families are traditionally the primary communication partners and facilitators of AAC for persons with communication disabilities in the home setting.16 The use of AAC tools in patient-family communication in the ICU has not been studied; but is critical to the development of evidence-based interventions to improve communication between family members and critically ill patients.

The purpose of this study was to describe family caregivers’ involvement with assisted communication tools with nonspeaking patients under different levels of patient-nurse communication training and intervention in the ICU. Research questions addressed in this study are

Which AAC tools do families use with nonspeaking ICU patients and how are they used?

What do families and nurses say about patient-family communication with nonspeaking patients in the ICU?

Methods

Research Design

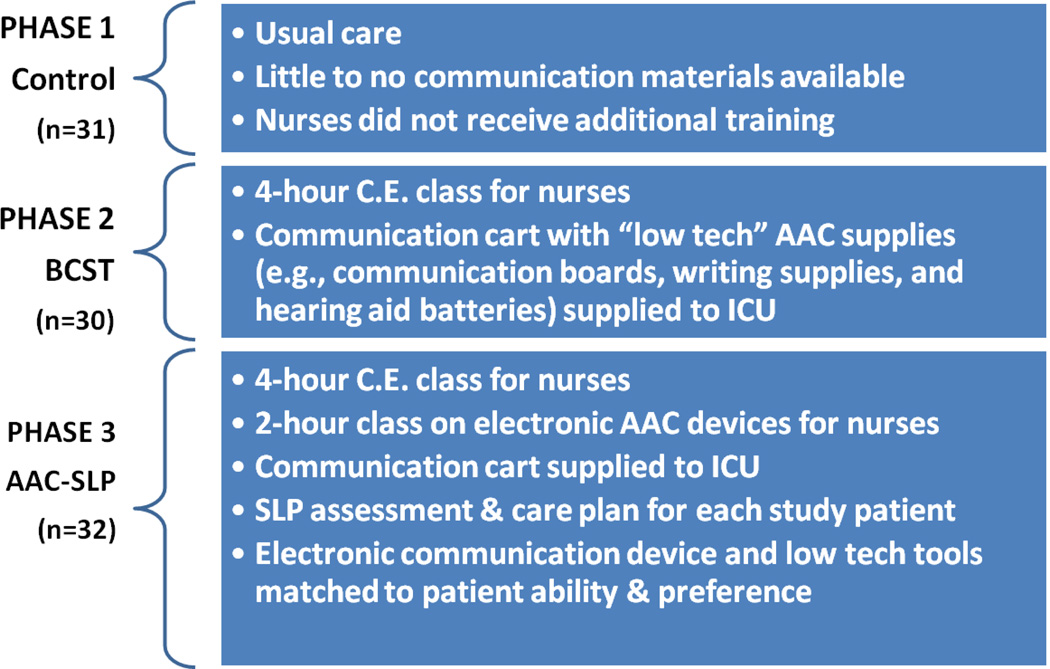

We conducted a qualitative secondary analysis of study records – field notes, intervention logs, and brief nurse interviews - from a clinical trial. The parent study design has been described in detail in previous publications.11, 17 Briefly, the parent study consisted of three sequential phases detailed in Figure 1. Ten ICU nurses with a minimum of 1 year critical care experience and no significant speech or hearing deficit were randomly selected to participate in each phase . Eligible patients were: (1) ≥ 18 years old; (2) nonvocal due to oral endotracheal tube or tracheostomy; (3) intubated for >48 hours; (4) able to understand English; and (5) scored 13 or above on Glasgow Coma Scale. Individuals who were reported to have a diagnosed hearing, speech or language disability that significantly interfered with communication prior to hospitalization were excluded. Eligible patients were enrolled and paired with a study nurse when he/she was scheduled to work two consecutive day shifts. Data collection primarily involved the observation and video recording of four nurse-patient communication sessions for each nurse-patent dyad enrolled in the study. Field notes were generated during patient enrollment in the study, during observational sessions, and during brief nurse interviews following observations. For patients in Phase 3, data sources also included the comprehensive evaluation notes made by the speech-language pathologist (SLP) during intervention sessions. University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to conduct qualitative secondary analysis of these documents.

Figure 1. Parent Study Intervention.

AAC = Augmentative and Alternative Communication; SLP = Speech Language Pathologist

Setting and Sample

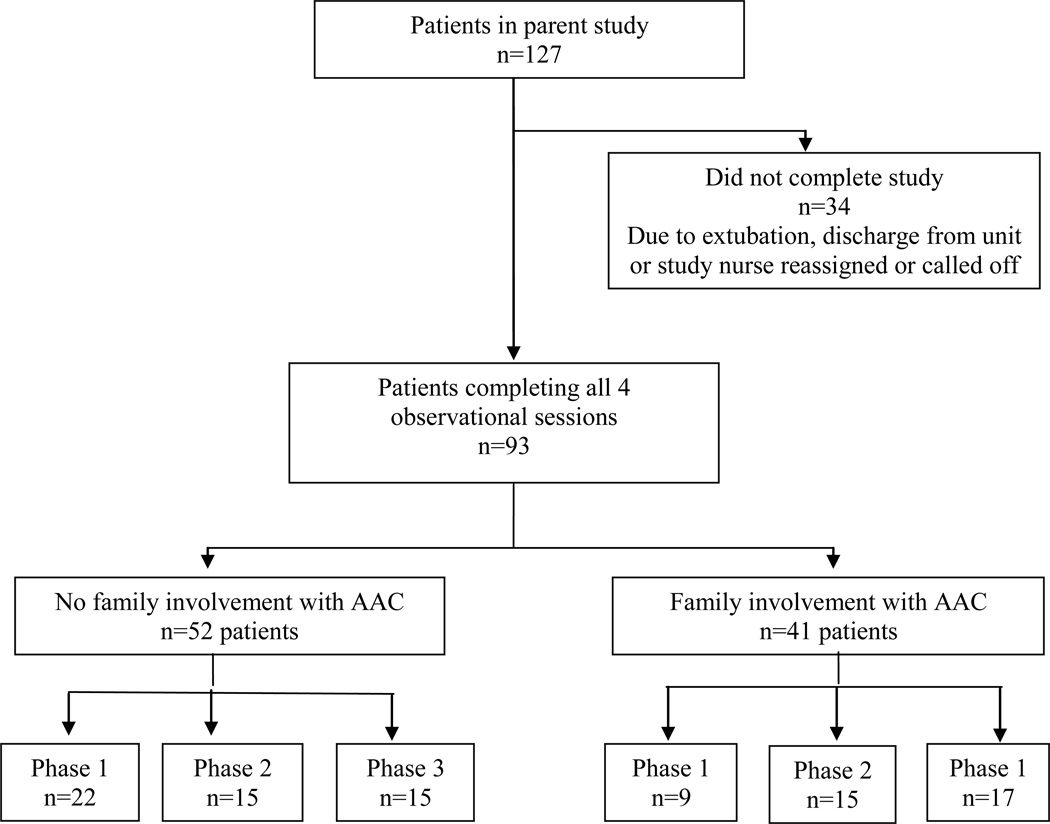

The parent study was conducted in the 32-bed medical ICU (MICU) and 22-bed cardiovascular-thoracic ICU (CT-ICU) at a large, tertiary medical center. Of the 127 patients who were enrolled in the parent study over the three different treatment conditions during a 4-year period (2004–2008), 93 patients completed all 4 observational sessions and comprised the sample for identification and quantification of AAC tool use. Narrative study data for all 127 patients enrolled in the parent study were reviewed for evidence of observations or comments about patient-family communication and family involvement with augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools. The final analytic sample focused primarily on documents from the 41 patients who had evidence of family involvement with AAC tools (Figure 2) with additional observations or comments about patient-family communication extracted from the documents of the other patients. Identification of these documents is described below.

Figure 2. Subsample Extraction.

AAC = Augmentative and Alternative Communication

Procedures

Observational data were collected in the parent study by one of 3 trained research assistants using a standardized observation tool established in previous research.18 Observers wrote detailed field notes documenting salient events pertaining to the setting, patient, nurse, the presence of family visitors, hospital environment or routine, reliability and availability of AAC equipment, interruptions,11, 18 Communication content and interactions were documented to supplement and enhance interpretation of the video recording. Nurse debriefing interviews used a semi-structured guide. After each session, data collectors began with a grand tour question, “Tell me about your interactions with this patient” followed by questions and probes about specific AAC tools or strategy and eliciting the nurse’s opinion about effectiveness of the technique. Nurses were asked specifically about family involvement in AAC communication strategies after the last video recorded session using the following questions, “Has the family been involved in AAC communication strategies? If so, how? How did they come to learn about [the strategy]?” “Did any messages or strategies come from the family?” Family members were not interviewed, however, observers recorded naturalistic family comments, particularly those about patient communication, when they occurred.

An AAC tool was defined as a physical object or device used to transmit or receive messages.19, 20 We defined family involvement with AAC tools as a family member’s use of or instruction in use of a low or high-tech communication tool or device during interaction with the patient. Of note, we included the following “unaided” strategies that, in this sample, involved partner (family) assistance or training: intentional eye-blinking systems and partner message scanning using Yes-No questions. We did not include head nods, gesture, and mouthing words because these are considered unaided communication strategies. 20 Thus, we focused on those strategies requiring physical objects, tools, or devices and/or family assistance or training.

For each patient in the initial parent study sample, the first author (LMB) reviewed the source documents in Microsoft Word format to identify and code the presence or absence of any family involvement with AAC, and to identify the specific family member(s) involved by relationship, e.g., adult child, spouse/significant other, sibling. A minimum of 5 source documents were available for each of the 93 patients who completed the parent study protocol; these typically consisted of a study enrollment note and field notes for each of the 4 observational sessions. One-third of the patients (n=31) had SLP evaluation/intervention reports. AAC tools and devices used by family members were then identified and categorized by the type of AAC tool; multiple uses of the same strategy within a patient case were coded only once. Similarly, for each AAC tool used, instances in which family members were the provider of the AAC tool were identified. This primary coding was subsequently reviewed by all three authors.

Qualitative content analysis was then applied to the text for simple description21, 22 of what families and nurses say about family-patient communication with nonspeaking patients in the ICU. The source documents containing evidence of family involvement with AAC or comments about family-patient communication were imported into Atlas.ti23 for data management and organization. Initial open coding of the documents was performed by the first author, and involved line-by-line examination of the text to identify the attributes and characteristics of family use of AAC strategies.24 A code list with definitions was then mutually generated by two authors (LMB and MBH) to ensure conceptual clarity and consistent application. During the iterative coding process, the dimensions and properties of codes that repeatedly appeared were more specifically defined (e.g., in terms of frequency, extent, intensity)24–26 and developed into a list of focused codes. Focused codes were eventually collapsed to identify themes. Codes and themes were compared within and across parent study phases to assess thematic strength and potential influences of the communication intervention on family AAC use. All documents were dual-coded by two authors (LMB and MBH); areas of coding disagreement were uncommon, and negotiated consensus was achieved without arbitration by a third investigator. Interpretive memos were also included in the analysis.25, 27 Traditional member-checking procedures for establishing the “trustworthiness” of the data28 were not feasible in this retrospective analysis. Instead, contextual perspectives for individual cases and review of the final themes were provided by a co-investigator (JAT) and other research staff who authored parent study source documents.

Results

Family Involvement with AAC

Family involvement with AAC strategies was noted in approximately 44% (n= 41) of the parent study patients (Figure 2). This subsample of patients was 51% male and 90% Caucasian; other demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Spouses/significant others (n=22) and adult children (n=10) constituted the family members communicating with patients most often. Other family members using AAC included parents (n=7), siblings (n=3), and other (n=4, i.e., grandchild, aunt, niece, “caretaker”) and unknown (n=1). Six patients had more than one family member involved.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient sample

| Parent Study Phase |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics |

Total Patients (n=41) |

Phase 1 (n=9) |

Phase 2 (n=15) |

Phase 3 (n=17) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 21 (51.2) | 6 (66.7) | 7 (46.7) | 8 (47.1) |

| Male | 20 (48.8) | 3 (33.3) | 8 (53.3) | 9 (52.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 37 (90.2) | 6 (66.7) | 14 (93.3) | 17 (100) |

| African-American | 4 (9.8) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Age, mean (SD) | ||||

| 57.7 (16.4) | 62 (15.9) | 58.53 (15.7) | 54.65 (17.5) | |

| Hospital Unit, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiothoracic ICU | 25 (61) | 6 (66.7) | 11 (73.3) | 8 (47.1) |

| Medical ICU | 16 (39) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 9 (52.9) |

|

APACHE II, mean SD |

53.49(12.9) | 51.33 (11.6) | 54.4 (10.7) | 53.8 (15.7) |

|

CAM-ICU, positive

n(%) |

10 (24.4) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (26.7) | 4(23.5) |

Writing (pen and paper) was the most frequent family-patient AAC strategy used (n=26 patients). Ten patients used electronic speech generating devices with family (Table 2). Eleven patients and their families used two or more strategies. Novel communication tools and assisted strategies devised or provided by families included intentional, idiosyncratic eye-blinking systems (n=3 patients), homemade flashcards or message boards (n=2 patient), a home computer (n=1 patient), and a child’s toy (n=2 patients) (e.g., “Magna Doodle,” “Etch-A-Sketch”) (Table 2).

Table 2.

AAC tools and assisted strategies used by families

| AAC Tool | n (%)a | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication/letter boards | 8 (14) | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Writing (paper/pencil) | 26 (46) | 7 | 12 | 7 |

| Commercial writing board (wipeable/dry erase) |

3 (5) | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Writing cuff | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Electronic AAC device | 10 (16) | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Personal Computer | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Flashcards” or homemade message board |

2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Toy | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Assisted Strategies | ||||

| Eye blinking | 3 (5) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Tagged yes/no–Partner scan | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 57 | 10 | 22 | 25 |

Notes.

Percentages may exceed 100% due to rounding. Eleven patients had family member(s) who used more than one AAC tool/strategy.

Main Themes Describing AAC Tool Use in Patient-Family Communication in ICU

Five main themes describing family involvement with AAC tools were identified across all phases of the parent study: (1) Families as unprepared and unaware; (2) Family perceptions of communication effectiveness; (3) Nurses deferring to or guiding patient-family communication; (4) Patient communication characteristics; and (5) Family experience and interest with AAC tools. Some differences were identified across phases. While ineffectiveness of AAC tools was a common family complaint throughout the study phases, positive comments about the effectiveness of AAC tools were concentrated, primarily in the intervention phases. Interventionist (SLP) notes in Phase 3 provided a greater emphasis on patient communication characteristics. Not surprisingly, evidence of family interest with AAC tools was stronger in the intervention phases.

Unprepared and unaware

Families were generally unprepared for the patients’ inability to communicate easily and effectively.

The family were unaware of the lack of patient communication prior to surgery. They prepared for surgery via a website dedicated to lung transplant patients and they said that although they were prepared for many other things, they were unaware of the communication issue. Had they known, they could have better prepared themselves. [Enrollment Note]

In other instances, families did not initially recognize patients’ communication capabilities.

The family did not believe that the patient could mouth words. [The researcher] demonstrated her ability. The patient’s son said, “Well, maybe now we can talk to her.” [Observation note]

The patient signed his own consent (for study participation) and it seemed as though the family was surprised that he could write. . . [Observation note]

Family perceptions of communication effectiveness

Families indicated frustration over their limited success with naturalistic communication strategies such as mouthing words and writing, and were aware of patients’ frustration as well.

The patient’s daughter said, “I wish I had a better way to understand him. Sometimes it’s so frustrating when he has to repeat over and over. I can’t read his lips.” [Enrollment note]

While families generally had limited success with lip-reading and writing, some experienced moderate ease with these conventional, intuitive strategies.

. . . sometimes [the husband] understood her [the patient] well and sometimes not. The “sometimes not” was when she mouthed too quickly to be understood. He said that he thought he understood her mouthing more often than not. [Observation note]

The [patient’s] mom reads his lips but cannot understand his writing. [Nurse interview]

Families’ reported satisfaction with lip reading occurred in the context of having additional, successful alternatives readily available, such as writing.

The visitors tell me that they are “getting good at lip reading” and can understand the patient fairly well when she mouths words. If not, the patient will write. [Observation note]

Her husband stated … that when he was unable to comprehend the message she mouthed, he would offer her a tablet and pen to write. He was able to understand those messages for the most part. [Enrollment note]

Writing and alphabet boards were not effective strategies for many families, however, primarily due to patients’ upper extremity edema or limited mobility, unavailability of the patient’s glasses, or an existing handwriting style that tended to be illegible.

The husband said the (communication) board was already in the room when they arrived the day before. Unfortunately, he said, the patient was too weak to pick out the letters. [Enrollment note]

[The patient’s] family said that he had tried to write but because he had no glasses and his writing was so illegible, he became frustrated and did not ask for the paper and pencil. . .[Enrollment note]

The patient had been printing notes but found it difficult to hold a pen. His hands were edematous and stiff. . . [Enrollment Note]

In some instances, family concerns extended beyond mere frustration with communication effectiveness to concerns about the patients’ safety and the vulnerability imposed by the inability to speak:

. . . The family found (the patient) with no call bell in reach. They know that the patient cannot speak; she needs access. [Observation note]

Nurses deferring to or guiding patient-family communication

Nurses typically deferred to families’ knowledge of and relationship with the patient in planning communication strategies and, sometimes, in interpreting non-vocal messages from the patient. This deference to and reliance on family interpretation was juxtaposed with an uncertainty about the accuracy of family interpretation.

Nurse: They (the family) made their own (communication) cards. They got photographs for him to look at. They’re not doing YES-NO questions, and 3 choices [referring to Written Choice technique]. They have a different relationship with him. They’re not as open to the [PARENT study] strategies, because they know him, and don’t need to use the strategies. . . They’ll try to tell me what he’s saying. It’s not always clear to me that they’re right, but they know him, I’ll take their word for it. [Nurse interview]

In other instances, however, nurses expressed concerns about the impact of families’ communication attempts on patients’ clinical progress, particularly with respect to cardiac status and weaning from mechanical ventilation. In these situations, nurses took an active role in directing families’ choice of communication strategies:

The nurse goes on to inform the son that the patient is trying to communicate but that she (the nurse) is trying not to have the patient write--just use YES-NO questions because the patient is experiencing a number of PVCs (premature ventricular complexes). [Observation note]

RN: (to family visitor) Do not try to make her talk. She is weaning (from the ventilator) at this time and this is the lowest setting she has been on. She has an issue with getting herself upset and is being medicated to keep her calm. She needs to relax. She is doing well right now and this is a good sign. All of us would be anxious if we could not talk. I understand. However, you need to limit your questions to yes or no answers. We need to progress to extubation. [Observation note]

Nurses recognized that some family members had difficulty communicating with their loved one in the ICU and encouraged them to interact and talk normally with the patient. For example, a nurse encouraged sisters who were having difficulty striking up a conversation with a patient to “Pretend that you two are on a bus and discuss something.” In another instance, a nurse facilitated a telephone conversation between a mechanically ventilated patient and her brother by reading the patient’s handwritten messages to the brother.

Prior patient communication characteristics

Family reports of prior patient communication and personality styles reflected their expectations of communication content and frequency.

Daughter: Well, he’s not much of a communicator. . . I just mean he doesn’t talk much. [Observation note]

[The patient’s] husband stated . . . that she had always been a “talker” and that being unable to communicate was frustrating for both of them. [Enrollment note]

[The patient’s] sister feels that the ICU staff hasn’t interacted enough with the patient and this has partially caused the patient’s deterioration in the hospital. She comments to me that the patient is a “big talker,” and this withdrawn, ambivalent attitude is new to her. [Enrollment note]

When asked if he used a hammer to pound a nail (a delirium screening question), the patient said he couldn’t but his son could. [The patient’s] son said he was always “cantankerous.” [Enrollment note]

Families also reported that limited literacy and pre-existing visual/auditory impairments affected patients’ baseline ability to read, write, or engage in extensive verbal interaction.

The husband says (a bit defensively), that the patient has difficulty with longer words in reading, but can read . . . [Observation note]

[The patient’s] wife called his hearing impairment “selective” prior to admission but admitted she thought it more profound now. She wondered if he “needed the wax cleaned out of his ears”. [Enrollment note]

Family experience and interest with AAC

In general, patients and their families had minimal familiarity with use of augmentative and assistive communication (AAC) tools and strategies. Prior familiarity with AAC rarely translated into a feasible communication strategy for families and patients.

[The patient’s grandson] sustained a massive head injury ten years ago and now uses an AAC device. The patient is also familiar with that device and her grandson’s use of eye blinks. The daughter states, however, that she is unable to decode her mother’s eye blinks even though she instructed her mother that one blink means yes’ and two mean no’. [Enrollment note]

I. . . learned that [the patient] was proficient in sign language. He had a large book lying on the side counter about American Sign Language. When I asked if his family members knew sign language also and used it to communicate with him, he shook his head ‘no.’ [Observation note]

Family members did express interest in AAC. In addition, several family members and patients generated creative solutions for overcoming communication challenges:

The son shows me a “magna-doodle” (toy) which he bought to help his father to communicate, stating “He is so frustrated not being able to communicate. . .” [Enrollment note]

The husband had provided the erasable writing board and pen immediately following her lung transplant. She was able to use it from the time she was admitted to the ICU. They also had an Etch-a-Sketch (toy). [Observation note]

The family indicated that [the patient] taught them how to actively participate by eye scanning and blinks. . . they needed two of them to complete the task, one to scan and read her blinks and the other to write the letters down. [Enrollment note]

Availability of communication materials at the bedside influenced family use of AAC strategies during phases 2 and 3 of the parent study.

. . . when [the husband] was unable to comprehend the message she mouthed, he would offer her a tablet and pen to write. He was able to understand those messages for the most part. He said that there had been a [communication] board in the room at one point and that he used it. He didn’t know where it was now so he relied on either mouthing or writing. [Observation note]

Family interest in and use of AAC varied. Some families reported minimal use.

. . . I also asked [patient’s family member] if he had personally used any of the AAC devices such as the letter board, which is in the patient’s room. He said he had not, but just tended to rely on the patient’s mouth. [Observation note]

There were several letter boards (study tools), the procedure boards lying on the monitor. I asked and the wife said she found them in a drawer in the room. She had used them rarely but found them rather effective. [Enrollment note]

[Father] states, “That device made it a lot easier;” “[the Dynamite™] is phenomenal.” [Observation note]

Yet, most families clearly desired the highest level of communication possible with their critically ill patient. In reviewing AAC strategies with the SLP, a patient’s wife commented, “This is all nice and all but if he can use a speaking valve, that’s what we want.”

Discussion

Most research about family interactions in the ICU focuses on family information needs and/or communication with health care providers.3, 6, 29–40 This study shifts the lens on family communication in the ICU to focus specifically on family-patient communication and the problems associated with family-patient communication in the context of critical illness, the patient’s loss of voice, and other communication impairments. The problem of communication difficulty among critically ill patients is receiving increased attention as a symptom and as a condition of mechanical ventilation during critical illness.41–44 The questions addressed in this study are novel and have not been considered by other research in the field.

Family involvement with AAC strategies will become a more central focus of patient-family centered care and provider-patient communication in the ICU given the release of new Joint Commission hospital accreditation standards.45 These Patient-Centered Communication Standards require clinical care providers to identify patient communication needs and implement a plan to address and accommodate existing or acquired communication impairments. Additionally, these standards explicitly recommend the use of a mixture of low, medium, and high tech AAC devices and strategies to address the communication needs of patients with sensory or communication impairments, and recommend ensuring the availability of these resources 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.45 (An overview of the Joint Commission initiatives in advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-and family-centered care can be found at: http://www.jointcommission.org/Advancing_Effective_Communication/.) The Society for Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) also recognizes that the psychosocial needs of critically ill patients who often cannot communicate are often overlooked, which compromises the delivery of patient-centered care in the ICU.46 SCCM draws attention to the benefits of family support and participation in care.46

Families are typically unprepared for the communication hallenges of critical illness.7 Resources that families used to prepare for surgery did not describe communication difficulties that result from intubation and mechanical ventilation in the post-operative period. Preoperative SLP consultation can be effective in planning post-operative communication services for patients who will be temporarily nonspeaking.47 Assessment by skilled clinicians at the bedside can reveal patient communication potential and serve to demonstrate useful assistive communication strategies to families.

Family discomfort and lack of proficiency with communication strategies may add to patient feelings of stress and frustration, rather than promoting improved outcomes. No published study has evaluated family perception of communication difficulty, or the effect of interventions to improve patient communication on family caregivers and their communication with critically ill relatives. Clearly, more research is needed to provide evidence-based strategies to aid family caregivers in this setting.

Nurses in this study maintained or assumed that YES-NO questions were the least stressful family-patient communication method during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV). While this perspective is consistent with previous qualitative research describing clinicians’ perspectives on family visitation during weaning from PMV,15 these claims have not been empirically tested or validated. This perspective is also consistent with previous observational studies documenting nurses’ control of the timing, topic and duration of communication in the ICU.17, 48–50 Communication with family members may be more stressful because patients want to communicate novel or emotional messages to family members (such as, “I love you,; Did you pay the gas bill?” etc) that are not amenable to standard YES-NO questions or a “medical needs” topic list.

Family members’ expectations of patient communication were consistent with past patterns and characteristics of the patient. This finding confirms the importance of an individualized approach to planning for AAC during critical illness and confirms individual variation in communication frequency and AAC tool preference.51 Additionally, our study results demonstrate that families carry important information regarding limited literacy and pre-existing visual/auditory impairments that are critical to effective AAC planning and strategy selection. The degree to which data on baseline communication function are routinely collected from families of mechanically ventilated ICU patients is unclear, however, this is an area of concern in the new TJC hospital accreditation standards.

Although AAC communication materials were available to patients in the two intervention phases of the parent study, in the absence of direct instruction and ongoing encouragement regarding how to use communication materials with seriously ill communication impaired patients, families often failed to use AAC in order to understand their critically ill loved ones’ messages and instead, just “made do.” Families’ limited interest in and use of AAC may have been due to having had limited exposure to various AAC strategies/devices, their potential for enhancing communication, and how to use them effectively. Our data indicate that families tended to rely on communication strategies which were more familiar and more readily available. Experience with deaf family members and/or American Sign Language did not translate into useful communication strategies during critical illness for patients. Families are likely to benefit from simple instruction and encouragement on how to use communication materials and basic assistive communication strategies in the ICU. Nurses and SLPs should make sure communication materials are available for family visitation to maximize all communication options for nonspeaking patients and their families.

There are several limitations in using an existing data sample.52–54 As the parent study focus involved nurse-patient communication, the data collection strategies were not designed with patient-family communication in mind; this may impact the comprehensiveness and validity of the findings, which should be considered primarily as hypothesis-generating. In addition to the 41 families identified in our study documents, other families may also have used AAC tools but were unobserved by nurses or our research team. That is, our dataset only includes observations at 5 time points over a 3 day period (enrollment and morning and afternoon observations during two days of observation) and does not represent the full extent of family involvement in assisted communication. We did not observe patient-family communication that occurred during evening visiting hours. Moreover, since these data were gleaned from a clinical trial in which a variety of communication strategies were available and/or presented to nonspeaking patients, we may have observed more AAC use than is currently typical in ICUs.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that while families experience difficulties in communicating with critically ill, nonspeaking ICU patients, their use of AAC tools and assisted strategies is limited, even when these resources are relatively available. Given these observations and the absence of discussion of the topic in the literature, it is likely that this is an unrecognized problem and may possibly contribute to both family and patient stress. Recent studies show that family members experience psychological symptoms such as anxiety, traumatic stress, and depression during and after a loved one’s critical illness.55–58 Indeed, family members are at risk for post traumatic stress disorder particularly if the patient dies.56, 59, 60 The relationship between patient communication difficulty and/or ability during critical illness and family outcomes following ICU discharge or death has not been explored. We hypothesize that interventions to improve family member knowledge and competency in the use of simple AAC materials and techniques might moderate or alleviate stress for families in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants from National Institute for Nursing Research 5K24-NR010244 and National Institute for Child Health and Human Development 5R01 HD043988 (M.B. Happ, Principal Investigator). Dr. Broyles is currently supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 10-014) from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA. Dr. Tate is an NIMH Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the Clinical Research Training Program in Geriatric Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh Department of Psychiatry (T32 MH19986; PI: Reynolds).

Acknowledgments, Disclaimers: The authors thank Jill V. Radtke, MSN, RN and Brooke Baumann, MS, SLP-CCC for their contributions to data collection and management. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

Institutions where work performed: University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System

References

- 1.Engstrom A, Soderberg S. The experiences of partners of critically ill persons in an intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2004;20(5):299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dreyer A, Nortvedt P. Sedation of ventilated patients in intensive care units: relatives' experiences. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(5):549–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White DB, Braddock CH, 3rd, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam P, Beaulieu M. Experiences of families in the neurological ICU: a"bedside phenomenon". J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36(3):142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CM. The identification of family members' contribution to patients' care in the intensive care unit: a naturalistic inquiry. Nurs Crit Care. 2005;10(1):6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hupcey JE. Looking out for the patient and ourselves--the process of family integration into the ICU. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(3):253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Happ MB. Interpretation of nonvocal behavior and the meaning of voicelessness in critical care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jablonski RS. The experience of being mechanically ventilated. Qual Health Res. 1994;4(2):186–207. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafsteindottir TB. Patient's experiences of communication during the respirator treatment period. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1996;12(5):261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(96)80693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. [Retrieved August 17, 2011];Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 2011 from http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Happ MB, Sereika S, Garrett K, Tate JA. Use of quasi-experimental sequential cohort design in the Study of Patient-Nurse Effectiveness with Assisted Communication Strategies (SPEACS) Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riggio RE, Singer RD, Hartman K, Sneider R. Psychological issues in the care of critically-ill respirator patients: differential perceptions of patients, relatives, and staff. Psychol Rep. 1982;51(2):363–369. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson V, Forsberg A, Bergbom I. Relatives' experiences of visiting a conscious, mechanically ventilated patient--a hermeneutic study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26(2):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse JM, Pooler C. Patient-family nurse interactions in the trauma-resuscitation room. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11:240–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Happ MB, Swigart V, Tate JA, Arnold RM, Sereika SM, Hoffman LA. Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Heart Lung. 2007;36:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beukelman DR, Mirenda P. Augmentative communication: Management of severe communication disorders in children and adults. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Happ MB, Sereika S, Garrett K, et al. Nurse-patient communication interactions in the ICU. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(2):e28–e40. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Happ MB, Roesch TK, Garrett K. Electronic voice-output communication aids for temporarily nonspeaking patients in a medical intensive care unit: a feasibility study. Heart Lung. 2004;33(2):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Report: Augmentative and alternative communication. ASHA. 1991;33(Supp 5):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd L, Quist R, Windsor J. A proposed augmentative and alternative communication model. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 1990;6(3):172–183. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan DL. Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken. Qual Health Res. 1993;3:112–121. doi: 10.1177/104973239300300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayring P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2000;1(2):105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 23.ATLAS.ti. 5.0 ed. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(4):371–375. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lofland J, Lofland LH. Analyzing social settings - a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3rd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cresswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auerbach SM, Kiesler DJ, Wartella J, Rausch S, Ward KR, Ivatury R. Optimism, satisfaction with needs met, interpersonal perceptions of the healthcare team, and emotional distress in patients' family members during critical care hospitalization. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(3):202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azoulay E, Pochard F. Communication with family members of patients dying in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin in Crit Care. 2003;9(6):545–550. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Van Zuuren F, Duijnstee M, Grypdonck M. The needs and experiences of family members of adult patients in an intensive care unit: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(4):501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swigart V, Lidz C, Butterworth V, Arnold R. Letting go: family willingness to forgo life support. Heart Lung. 1996;25(6):483–494. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, Fields J. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs Res. 2001;50(2):105–115. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheunemann L, McDevitt M, Carson S, Hanson L. Systematic review: Controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care. Chest. 2010 doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lautrette A, Ciroldi M, Ksibi H, Azoulay E. End-of-life family conferences: rooted in the evidence. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S364–S372. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237049.44246.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. NEJM. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azoulay E, Sprung CL. Family-physician interactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2323–2328. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145950.57614.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Jourdain M, Bornstain C, Wernet A, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(4):438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee Char SJ, Evans LR, Malvar GL, White DB. A randomized trial of two methods to disclose prognosis to surrogate decision makers in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(7):905–909. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyd EA, Lo B, Evans LR, Malvar G, Apatira L, Luce JM, et al. "It's not just what the doctor tells me:" factors that influence surrogate decision-makers' perceptions of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(5):1270–1275. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8a217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson JE, Meier DE, Litke A, Natale DA, Siegel RE, Morrison RS. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1527–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000129485.08835.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patak L, Gawlinski A, Fung NI, Doering L, Berg J. Patients' reports of health care practitioner interventions that are related to communication during mechanical ventilation. Heart Lung. 2004;33:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell GB, Happ MB. Symptom identification in the chronically critically ill. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2010;21(1):64–79. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c932a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puntillo KA, Arai S, Cohen NH, Gropper MA, Neuhaus J, Paul SM, et al. Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying*. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2155–2160. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f267ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. 2010 Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/ARoadmapforHospitalsfinalversion727.pdf.

- 46.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costello J. AAC intervention in the intensive care unit: The children's hospital Boston model. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 2000;16(3):137–153. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salyer J, Stuart BJ. Nurse-patient interaction in the intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1985;14(1):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall DS. Interactions between nurses and patients on ventilators. Am J Crit Care. 1996;5(4):293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashworth P. Care to Communicate: An investigation into problems of communication between patients and nurses in intensive therapy units. London: Whitefriars Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beukelman DR, Garrett KL, Yorkston KM, editors. Augmentative Communication Strategies for Adults with Acute or Chronic Medical Conditions. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parry O, Mauthner NS. Whose data are they anyway? Practical, legal and ethical issues in archiving qualitative research data. Sociology. 2004;38(1):139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heaton J. Reworking Qualitative Data. London: SAGE Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L. The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qualitative Health Research. 1997;7(3):408–424. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert P-E, Cheval C, Coloigner M, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20(1):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, Fontaine DK, Puntillo KA. Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(4):1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cf6d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, O'Toole E, Hickman RL., Jr Depression among white and nonwhite caregivers of the chronically critically ill. J Crit Care. 2010;25(2):364, e311–e369. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kross EK, Gries CJ, Curtis JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder following critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24:875–887. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]