Abstract

Our study was to elucidate the mechanisms whereby BMS-345541 (BMS, a specific IκB kinase β inhibitor) inhibits the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and evaluate whether BMS can sensitize MCF-7 breast cancer cells (MCF-7 cells) to ionizing radiation (IR) in an apoptosis-independent manner. In this study, MCF-7 cells were exposed to IR in vitro and in vivo with or without pretreatment of BMS. The effects of BMS on the repair of IR-induced DSBs by homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) were analyzed by the DR-GFP and EJ5-GFP reporter assays and IR-induced γ-H2AX, 53BP1, Brca1 and Rad51 foci assays. The mechanisms by which BMS inhibits HR were examined by microarray analysis and quantitative reverse transcription PCR. The effects of BMS on the sensitivity of MCF-7 cells to IR were determined by MTT and clonogenic assays in vitro and tumor growth inhibition in vivo in a xenograft mouse model. The results showed that BMS selectively inhibited HR repair of DSBs in MCF-7 cells, most likely by down-regulation of several genes that participate in HR. This resulted in a significant increase in the DNA damage response that sensitizes MCF-7 cells to IR-induced cell death in an apoptosis-independent manner. Furthermore, BMS treatment sensitized MCF-7 xenograft tumors to radiation therapy in vivo in an association with a significant delay in the repair of IR-induced DSBs. These data suggest that BMS is a novel HR inhibitor that has the potential to be used as a radiosensitizer to increase the responsiveness of cancer to radiotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

It has been well established that ionizing radiation (IR) kills cancer cells primarily by induction of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and efficient repair of DSBs is required for the clonogenic survival of irradiated cells (1, 2). Our recent studies showed that IκB kinase β (IKKβ), but not IKKα, can regulate the repair of IR-induced DSBs in a nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) RELA-independent manner (3). This finding suggests that specific IKKβ inhibitors can be exploited as novel therapeutic agents to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to IR. Since IKKβ inhibitors can inhibit not only DSB repair but also NF-κB mediated induction of anti-apoptotic proteins (4–6), they are potentially more advantageous than other DSB repair inhibitors such as ATM and DNA-PK inhibitors to sensitize tumor cells to IR.

BMS is a potent and specific inhibitor of IKKβ (7). It binds to an allosteric binding site on the IKKβ catalytic subunits and can inhibit IκBα phosphorylation and degradation and therefore NF-κB activation induced by diverse stimuli (7). Our previous studies demonstrated that BMS can sensitize MCF-7 breast cancer cells (MCF-7 cells) to IR in vitro at least in part by inhibition of DSB repair (3). However, the mechanisms by which BMS inhibits DSBs are unknown, and whether it can sensitize tumor cells to IR in vivo has not been tested. Therefore, in the present study we elucidate the mechanisms whereby BMS inhibits the repair of DSBs and evaluate whether BMS can sensitize MCF-7 cells to IR not only in vitro but also in a mouse xenograft tumor model. Our investigations revealed that BMS selectively inhibited homologous recombinational (HR) repair of DSBs in MCF-7 cells, probably by down-regulation of several genes that participate in HR, which led to a significant increase in the DNA damage response (DDR) that sensitizes MCF-7 cells to IR-induced cell death in an apoptosis-independent manner. Furthermore, BMS treatment sensitized MCF-7 xenograft tumors to radiation therapy in vivo in an association with a significant delay in the repair of IR-induced DSBs. BMS has been shown to be relatively safe and appears not to cause significant normal tissue damage in vivo (8–10). These findings and our current data highlight the therapeutic potential of BMS as a novel tumor radiosensitizer that can be used to selectively increase the responsiveness of tumors to IR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Reagents

MCF-7 cells and H1299 and H1648 human lung cancer cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified incubator (95% air/5% CO2) at 37°C. IKKβ knockdown (IKK-β (−)) MCF-7 cells and MCF-7 cells stably transfected with a dominant-negative mutant IκBα (mIκBα or IκBα A32/36) were generated and obtained as we previously described (3). BMS-345541 (BMS), Hoechst-33342 (Hoe) and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Irradiation of Cells

Cells were exposed to various doses of IR in a J. L. Shepherd Model Mark I 137Cesium γ-irradiator (J. L. Shepherd, Glendale, CA) at a dose rate of 1.84 Gy/min. Cells were irradiated on a rotating platform.

NF-κB RelA DNA-binding Activity Assay and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

All of these assays were carried out as described previously (3). The sequences for all of the primers used in the qRT-PCR analyses are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR3034.1.S1).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells grown on a 4-chamber CultureSlide (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) after various treatments were fixed, permeabilized and stained as previously described (3). The following antibodies were used for the immunofluorescent staining: 1:1000 mouse anti-phospho-H2AX (γ-H2AX [Ser139], clone JBW301; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and rabbit anti-53BP1 (no. ab36823; Abcam, Cambridge, CA); 1:100 rabbit anti-RAD51 (no. ab213; Abcam); 1:50 rabbit antibody against Brca1 (no. ab16780; Abcam), phosphor-ATM (pATM [Ser1981]) (no. 200-301-400; Rockland Biochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) and phospho-Chk2 (pChk2 [Thr68]) (no. 2661, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); and 1:500 Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (no. A11004, Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) or FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (no. ab6717; Abcam). Approximately 200 nucleus images were acquired using a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope with an Apo 60×/1.4 oil DICIII objective and AxioVision (4.7.1.0) software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., GmbH, Jena, Germany). The numbers of γ-H2AX, 53BP1, Rad51, Brca1, pATM and pChk2 foci in each cell were accounted, averaged and expressed as foci/cell.

Neutral Comet Assay

Cells were either sham-irradiated or exposed to 15 Gy IR 1 h after pretreatment with vehicle or 5 μM BMS. Cells were collected at various times after irradiation and processed for neutral comet assay using a CometAssay® kit from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, MD) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 100 nucleus images were captured for each slide and processed by a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope as described before (3). The tail moments from the cells were measured by the TriTek CometScore™ software (Version 1.5.2.6; TriTek Corporation, Summerduck, VA).

HR Assay

HR was measured in MCF7/DR-GFP cells, according to the previous publication (11). As shown in Fig. 2A, transient expression of the rare cutting restriction enzyme I-SceI in MCF-7 cells that carry pDR-GFP produces a DSB in one of the two GFP mutant genes (SceGFP and iGFP). The DSB can be repaired by HR between the two GFP mutant genes, resulting in the restoration of a functional GFP gene and the expression of GFP proteins. Therefore, quantification of the percentage of GFP-positive cells after expression of I-SceI in MCF-7/DR-GFP cells can be used to measure the efficiency of HR-mediated DSB repair. Specifically, MCF-7/DR-GFP cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per 60 mm dish and transfected with 2.5 μg pCBASceI plasmid DNA on the following day by lipofectamine transfection (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The cells and the plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Maria Jasin at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. After 6 h of transfection, cells were incubated with 2.5 μM BMS and then harvested 72 h after transfection. Cells transfected with pEGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) were included as a calibration control for GFP-positive cells. Cells were analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to measure the percentage of green fluorescent cells relative to the total cell number. For each analysis, 20,000 cells were processed, and each experiment was repeated three times.

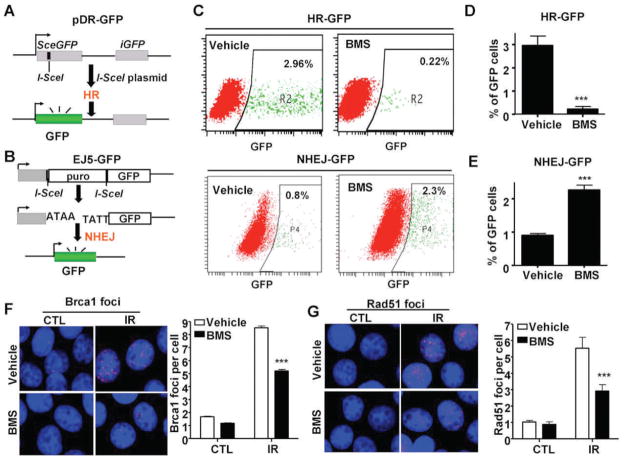

FIG. 2.

BMS selectively inhibits HR. Panel A: A diagram to illustrate the HR/DR-GFP reporter assay. Panel B: A diagram to illustrate the NHEJ/EJ5-GFP reporter assay. Panel C: Representative flow cytometric analyses of DSB repair by HR or NHEJ in MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or BMS. Panels D and E: Percentage of GFP positive cells repaired by the I-SceI-generated DSBs by the HR and NHEJ pathways according to the HR-GFP (or DR-GFP) and NHEJ-GFP (or EJ5-GFP) reporter assays, respectively, after the cells were treated with vehicle or 2.5 μM BMS. The data are presented as mean ± SE from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle. Panels F and G: BMS treatment inhibits IR-induced BRCA1 and Rad51 foci in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle or 5 μM BMS for 1 h before exposure to 2 Gy IR. IR-induced BRCA1 and Rad51 foci were analyzed by immunofluorescent staining 1 h after IR. The cells without exposure to IR were also included as a control (CTL). Representative photomicrographs of the immunofluorescent stainings are shown in the left (100× magnifications) and the average numbers (±SE) of foci/cell from three independent experiments are presented in the right. ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

NHEJ Assay

The NHEJ assay was carried out using the EJ5-GFP reporter assay developed by Stark et al. with some modifications (12). EJ5-GFP contains a promoter that is separated from a GFP coding region by a puro gene (Fig. 2B). The puro gene is flanked by two I-SceI sites that are in the same orientation. Once the puro gene is removed by NHEJ repair of the two I-SceI-induced DSBs, the promoter is rejoined to the rest of the coding cassette to restore the GFP gene. Therefore, analysis of the percentage of GFP-positive cells in MCF-7 cells after co-transfection of EJ5-GFP and I-SceI can be used to measure NHEJ activity. Specifically, 3 × 105 MCF-7 cells were co-transfected with 2 μg of the NHEJ reporter plasmid pim-EJ5-GFP (a generous gift from Dr. Jeremy M. Stark at the City of Hope) along with 2 μg of pCBASceI (from Dr. Maria Jasin) and 0.5 μg pDsRed2-ER (Clontech) that served as a transfection control using the Fugene 6 HD transfection kit according to the manufacture’s protocol (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were treated with vehicle or 2.5 μM BMS at 6 h post transfection and harvested 72 h later for analysis. The percentage of GFP-expressing cells which had repaired the DSBs generated by I-SceI in the reporters by NHEJ was determined by flow cytometry in the DsRed-positive cell population after excluding dead cells by PI staining.

Microarray Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from MCF-7 cells after they were incubated with vehicle or 5 μM BMS for 6 h using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The quality and quantity of the extracted RNA were determined by the Agilent 2100 RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). All of the samples had RIN (RNA integrity number) of 9.8 or above. One hundred fifty ng of total RNA were amplified using the WT-Ovation™ PicoSL WTA System (NuGEN Technologies, Inc., San Carlos, CA), resulting in 6–10 folds of amplification. To prepare the samples for hybridization, 3,000 ng of the amplified samples were labeled with biotin using the NuGEN Encore™ BiotinIL Module. The gene expression profiling was performed using the HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip from Illumina (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions except that the hybridization was performed using 1,500 ng at 48°C per the Encore protocol. The hybridized slides were scanned using the iScan and were imported into Genespring GX11.5 (Agilent Technologies, CA). Raw data were log2 transformed and then normalized to the 75th percentile of all values on a chip. The vehicle- and BMS-treated samples were compared using t test to examine for differentially expressed genes. A list of genes with ≥2.0-fold change was generated first and was tested by Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction. Significant genes were selected with a cut-off of P < 0.05 and a fold-change >2.0.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

The selected genes were subsequently analyzed using IPA 5.0 (Ingenuity Systems Inc., Redwood, CA). Functions and pathways, which were predicted to be influenced by the differentially expressed genes, were ranked in order of significance and further analyzed by overlaying with DNA replication, recombination and repair.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out as previously reported (3), with the following primary antibodies: anti-Rad51 (no. ab213; Abcam), Brca1 (no. ab16780; Abcam), Oct1 (no. 8157, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), eEF2 (no. 2332, Cell Signaling Technology), p53 (no. 9282, Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-p53 (pp53 [Ser15]) (no. 9286, Cell Signaling Technology), and Actin (no. SC-1616, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

MTT Assay and Chou-Talalay Analysis

MCF-7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well. After overnight incubation, they were treated with vehicle or 2.5 or 5 μM BMS for 1 h, and then exposed to different doses (0, 1, 2 and 3 Gy) of IR. After 48 h culture, cell proliferation and viability were measured by MTT assay as previously described (13). To determine the interactive effect between BMS treatment and IR on MCF-7 cells, Chou-Talalay analysis was performed as previously described (14). Specifically, the dose-response curves and 50% effective dose values (ED50) were obtained for the individual treatments. The fixed ratios of BMS and IR and mutually exclusive equations were used to determine the combination indices (CI) according to the method of Chou-Talalay (14). Briefly, the combined dose-response curves were fitted to Chou-Talalay lines, which are derived from the law of mass action and described by the equation: log(fa/fu) = m log(D) − m log(Dm), in which fa is the fraction affected, fu is the fraction unaffected, D is the dose, Dm is the median-effect dose, and m is the coefficient signifying the shape of the dose-response curve. The CI values were calculated using the equation: CI = (D1/D×1) + (D2/D×2) + (D1) (D2)/[(D×1) (D×2)], where D×1 and D×2 are the BMS and IR doses, respectively, which are required to achieve a particular fa, and D1 and D2 are the doses of the 2 treatments (combined treatment) required for achieving the same fa. CI < 1, CI = 1 and CI > 1 indicate synergistic, additive, and antagonistic interactions, respectively.

Clonogenic Survival Assay

MCF-7 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1,000 cells/well. After overnight incubation, they were pretreated with vehicle or 2.5 μM BMS for 1 h and then exposed to various doses (0, 1, 2 and 3 Gy) of IR. The cells were allowed to grow for an additional 12 days to form colonies before staining with 0.1% crystal purple. Colonies with more than 50 cells were counted. Survival fraction was calculated according to the plating efficiency of control cultures without BMS treatment and IR.

Analyses of Apoptosis

MCF-7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 5 × 105/well. After overnight incubation, they were pretreated with vehicle or 5 μM BMS for 1 h and then exposed to 2 Gy of IR. They were harvested at various times after irradiation and resuspended in 1× binding buffer (BD Biosciences) at a concentration of 1 ×106 cells/ml. An aliquot (100 μl) of the cell suspension was incubated with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC (BD Biosciences) or PI (1 mg/ml) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After addition of 400 μL of the 1× binding buffer, 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed by a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) to quantify apoptotic cells (Annexin V-FITC positive cells or sub-G1/0 cells).

MCF-7 Xenograft Tumor Model

MCF-7 xenograft tumors were established in female NCr-nu athymic nude mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD), as previously described (15). The tumors were allowed to reach 100–150 mm3 and the animals with tumors in this size range were randomly divided into four different treatment groups: vehicle (3% Tween 80), BMS (50 mg/kg), vehicle plus IR and BMS plus IR. Vehicle or BMS were given to mice three times by oral gavage every other day on days 1, 3 and 5. Two hours after each treatment, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation to immobilize the mice before local irradiation. Each tumor was sham-irradiated or locally irradiated by 3 Gy X rays generated from a Seifert Isovolt 320 X-ray machine (Seifert X-Ray, Fairview Village, PA), operated at 250 kVp and 15 mA, with 3 mm aluminum added filtration (half-value layer, 0.85 mm3; dose rate, 4.49 Gy/min). The areas outside the tumor were shielded to achieve tumor-specific irradiation and to reduce damage to normal tissue. Animals for sham irradiation were placed on the irradiation stage exactly as those for irradiation, except that the X-ray machine was not turned on. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Immunohistochemistry

The athymic mice with MCF-7 xenograft tumors were pretreated with vehicle or BMS and then sham-irradiated as control or exposed to 3 Gy local IR as described above. One hour and 6 h after the exposure, the sham-irradiated and irradiated tumors were harvested after the mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and cervical dislocation and fixed immediately with 4% PFA. Paraffin-embedded xenograft tumor sections were prepared in a routine manner. After antigen retrieval and permeabilization, they were stained for the analysis of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci as described previously (3).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). For experiments in which only single experimental and control groups were used, group differences were examined by unpaired Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. All of these analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism from GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

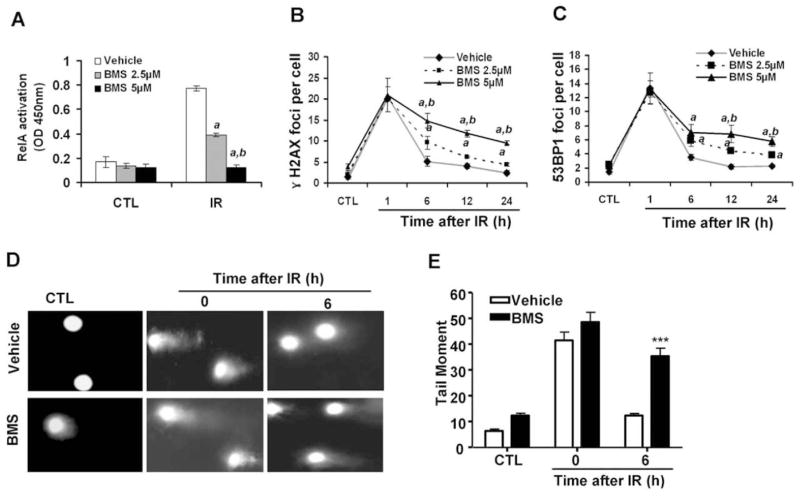

BMS Inhibits the Repair of IR-Induced DSBs in a Dose-Dependent Manner

BMS is a potent and specific IKKβ inhibitor (7) and can dose-dependently inhibit IR-induced NF-κB activation in MCF-7 cells, as shown in Fig. 1A. This inhibition was correlated with a dose-dependent reduction in the repair of IR-induced DSBs analyzed by the γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci assays 6, 12 and 24 h after irradiation (Fig. 1B and C) (16–18). This finding was validated by the neutral comet assay (Fig. 1D and E) (19), and confirmed that BMS can effectively inhibit the repair of IR-induced DSBs in MCF-7 cells. Similar findings were also observed in other tumor cell lines (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

BMS dose-dependently inhibits IR-induced NF-κB activation and the repair of IR-induced DSBs. MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), 2.5 or 5 μM BMS for 1 h before exposure to 2 Gy IR. The cells without exposure to IR were included as a control (CTL). Panel A: NF-κB activation by IR was determined at 1 h post IR by the NF-κB RelA DNA-binding activity assay. The data are presented as mean ± SE (n =3). Panels B and C: Analysis of DSBs at various time points after IR by γ-H2AX and 53BP1 immunofluorescent staining. The average numbers (±SE) of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci/cell from three independent experiments are presented in panels B and C, respectively. a, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; b, P < 0.001 vs. BMS 2.5 μM. Panels D and E: Analysis of DSBs by the neutral comet assay; representative photomicrographs of a neutral comet assay are shown in panel D (100× magnifications) and the average tail moments (±SE) from three independent experiments are presented in panel E. ***P < 0.001, 5 μM BMS vs. vehicle.

BMS Selectively Inhibits HR

DSBs can be repaired by HR and/or NHEJ (20, 21). To gain more insight into the mechanisms by which BMS inhibits DSB repair, we employed the DR-GFP and EJ5-GFP reporter assays to measure HR and NHEJ (11, 12), respectively (Fig. 2A and B). It was found that BMS treatment significantly decreased the percentage of GFP-positive cells in MCF-7/DR-GFP cells after expression of I-SceI in comparison with the cells without BMS treatment (Fig. 2C and D). In contrast, the percentage of GFP-positive cells in MCF-7 cells co-transfected with the EJ5-GFP and I-SceI plasmids was slightly increased after BMS treatment (Fig. 2C and E). These findings suggest that BMS can selectively inhibit the repair of DSBs induced by I-SceI by the HR pathway.

To determine whether BMS also inhibits the repair of IR-induced DSBs through the inhibition of HR, we compared the formation of IR-induced Rad51 and Brca1 foci in MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or BMS. The assembly of Rad51 nucleoprotein filament (or foci) represents an important step in the repair of DSBs by HR and Brca1 is required for the formation of Rad51 foci (21, 22). As shown in Fig. 2F and G, 1 h after exposure to IR vehicle-treated MCF-7 cells exhibited significant increases in the formation of Brca1 and Rad51 foci. The increases were diminished by the treatment with BMS, even though BMS-treated MCF-7 cells exhibited similar numbers of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci after irradiation at the same time point (Fig. 1B and C). These data provide further support that BMS can selectively inhibit HR.

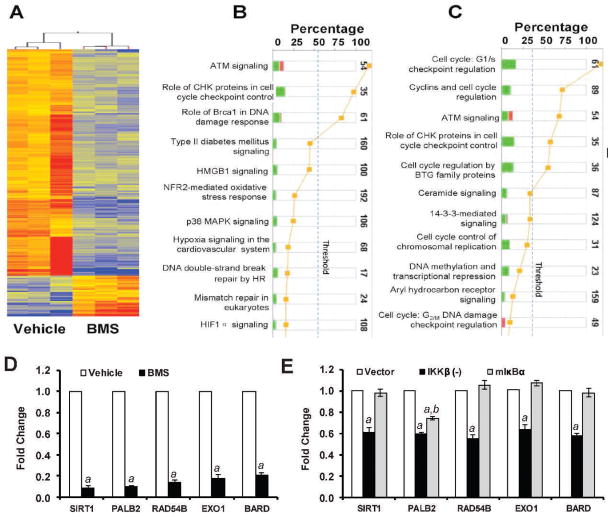

BMS Inhibits the Expression of Several Genes that are Involved in HR

To gain a better understanding of how BMS inhibits HR, we compared the gene expression profiles of MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or BMS by microarray assay. Genesping GX analysis revealed about 869 genes altered greater than twofold (P < 0.05) in the BMS-treated cells compared to vehicle-treated cells (supplementary material Table S2: http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR3034.1.S2). Among these genes, 146 were up-regulated and 723 were down-regulated as shown in Fig. 3A. Particularly, IPA identifies that BMS treatment compromised the DNA damage repair and response pathway (Fig. 3B) and the cell cycle control pathway (Fig. 3C). Very interestingly, 5 of the down-regulated genes in the DNA damage repair and response pathway (supplementary material Table S3: http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR3034.1.S3), BARD1, PALB2, EXO1, RAD54B and SIRT1, have been implicated in HR (23–26). Their down-regulation was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3D). It has been shown that Bard1 is required for proper localization of Brca1 to the sites of DSBs (25) and that Exo1 is required for the recruitment of RPA and Rad51 to DSBs (23), whereas Brca1/Brca2 and Palb2 act together to facilitate the assembly of Rad51 nucleoprotein filament (or foci) (26). In addition, it was reported recently that Sirt1 can promote HR repair of DSBs by interacting with the WRN helicase (24). Therefore, it is highly plausible that by down-regulating these HR genes, BMS may effectively inhibit the repair of DSBs by HR.

FIG. 3.

Effects of BMS on gene expression. Panel A: Heatmap of the 869 genes altered greater than twofold (P < 0.05) in the BMS-treated group vs. vehicle revealed by the microarray analysis. Red: up-regulated genes; blue: down-regulated genes. Panels B and C: Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) identifies the compromised DNA repair pathway (panel B) and the cell cycle control pathway (panel C). Stacked bar chart demonstrates IPA-generated activated canonical pathway. The height of the bar indicates the percentage of genes that changed in the pathway. Red: up-regulated genes. Green: down-regulated genes. Pathways with the P value (yellow dot) above the threshold (dash line) are significantly activated. Panel D: Validation of BMS-down-regulated genes that have been implicated in the HR pathways by real-time RT-PCR. Panel E: Effects of IKKβ knockdown by shRNA (IKKβ (−)) and NF-κB inhibition by ectopic expression of a dominant-negative mutant IκBα (mIκBα) on the expression of selective HR genes in MCF-7 cells. The data are presented in panels D and E as mean ± SE (n =3) of fold-changes compared to the vehicle-treated and vector-transfected cells, respectively, after normalization with the housekeeping gene GAPDH. a, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle or vector-transfected cells; b, P < 0.05 vs. IKKβ (−) cells.

To determine whether inhibition of IKKβ and NF-κB mediates BMS-induced suppression of HR gene expression, we examined the effects of IKKβ knockdown by shRNA and inhibition of NF-κB by a dominant-negative mutant IκBα (mIκBα) on the expression of BARD1, PALB2, EXO1, RAD54B and SIRT1 mRNA in MCF-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 3E, we found that knockdown of IKKβ by a specific IKKβ shRNA down-regulated the expression of BARD1, PALB2, EXO1, RAD54B and SIRT1 mRNA. In contrast, ectopic expression of mIκBα that inhibits NF-κB activity had no such effect (Fig. 3E). These findings suggest that inhibition of IKKβ may mediate BMS-induced suppression of HR gene expression, but in an NF-κB-independent manner. The mechanisms whereby IKKβ regulates these HR genes have yet to be determined.

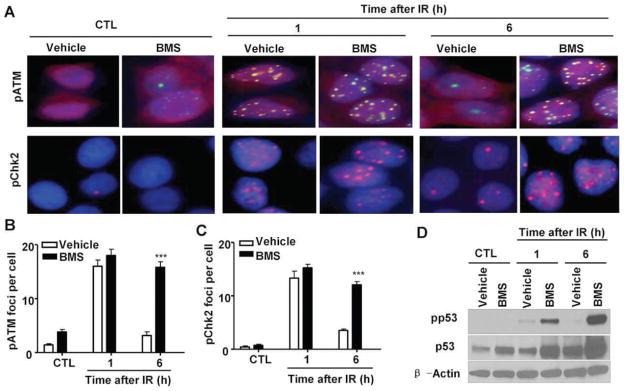

BMS Increases DNA Damage Response to IR

Cells respond to DNA damage by eliciting a series of cellular responses collectively termed the DNA damage response (DDR) (27). DDR can be initiated by IR through ATM that functions as a part of the DNA damage sensory machinery to detect DSBs (28). After the recruitment to the sites of DSBs, ATM is phosphorylated and activated. Activated ATM in turn phosphorylates a number of substrates, including Chk2 and p53, to induce cell-cycle arrest and facilitate DNA repair. If the damage cannot be repaired promptly and efficiently, it can lead to sustained activation of DDR and induction of cell death. Since BMS inhibits the repair of IR-induced DSBs in MCF-7 cells, we hypothesized that BMS may sensitize the cells to IR by augmenting DDR. To test this hypothesis, we examined the magnitude and duration of ATM and Chk2 phosphorylation/activation in MCF-7 cells after they were exposed to IR in the presence or absence of BMS by immunofluorescent staining. As shown in Figs. 4A–C, exposure to IR increased the numbers of pATM foci and pChk2 foci in MCF-7 cells and the increases were comparable in MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or BMS 1 h after IR when the formation of the foci reached the peak level. The numbers of pATM and pChk2 foci in vehicle-treated cells declined rapidly thereafter and were almost back to the basal levels at 6 h after irradiation, because these cells could efficiently repair IR-induced DSBs. In contrast, the numbers of pATM and pChk2 foci in BMS-treated cells remained significantly elevated 6 h after irradiation due to an inability of the cells to efficiently repair DSBs. Similar finding was also observed when we analyzed p53 phosphorylation as an additional indicator of DDR by Western blot (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that BMS treatment not only inhibits the repair of IR-induced DSBs in MCF7 cells but also elicits a stronger and more sustained DDR to IR.

FIG. 4.

BMS enhances DNA damage response (DDR) to IR. MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle or 5 μM BMS for 1 h before exposure to 2 Gy IR. IR-induced phosphorylation of ATM and Chk2 were analyzed by immunofluorescent staining, and p53 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blot at 1 and 6 h after irradiation. The cells without exposure to IR were also included as a control (CTL). Panel A: Representative photomicrographs (100× magnifications) of phosphorylated ATM (pATM, green) and Chk2 (pChk2, red) immunofluorescent stainings and nucleic counterstaining with Hoechst-33342 (blue) are shown. Panels B and C: Average numbers (±SE) of pATM and pChk2 foci/cell are presented. ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle. Panel D: A representative analysis of the levels of phosphorylated p53 (pp53), total p53 and β-actin in MCF-7 cells by Western blots is shown. Similar results were also observed in two additional analyses.

BMS Sensitizes MCF-7 Cells to IR in an Apoptosis-Independent Manner

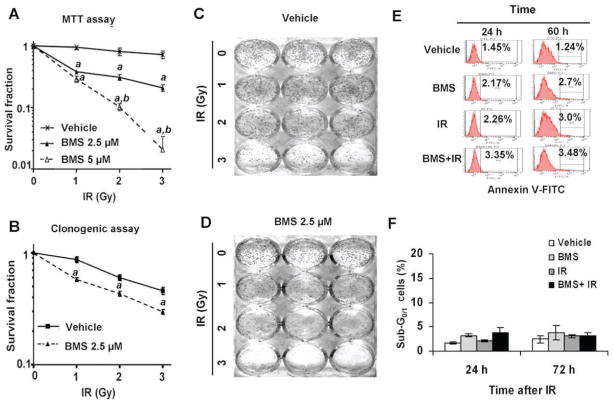

It has been well-established that IR kills cancer cells primarily by induction of DSBs and efficient repair of DSBs is required for the survival of irradiated cells (1, 2). Since BMS can inhibit the repair of IR-induced DSBs and augment DDR in MCF-7 cells, we hypothesized that BMS may sensitize the cells to IR. This hypothesis was confirmed by the finding that BMS pretreatment significantly reduced the proliferation and survival after MCF-7 cells were exposed to increasing doses of IR measured by MTT assay (Fig. 5A). The interaction between BMS and IR was synergistic (CI < 1) according to the Chou-Talalay analysis (14). In addition, the clonogenic survival assay demonstrated that MCF-7 cells treated with BMS were more sensitive to IR-induced clonogenic cell death than were the cells without BMS treatment (Fig. 5B–D).

FIG. 5.

BMS sensitizes MCF-7 cells to IR. Panel A: MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle, 2.5 or 5 μM BMS for 1 h before exposure to increasing doses (0, 1, 2 and 3 Gy) of IR. The survival and proliferation of the cells were measured by MTT assay 48 h after irradiation. The data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3) of survival fractions compared to unirradiated control cells. Panels B–D: MCF-7 cells were incubated with vehicle or 2.5 μM BMS for 1 h before exposure to increasing doses (0, 1, 2 and 3 Gy) of IR. The survival fractions of vehicle- or BMS-treated MCF-7 cells after exposure IR were analyzed by clonogenic assay and are presented in panel B as mean ± SE of three independent experiments. Representative photographs of a clonogenic assay are presented in panels C and D. Panel E: Representative analyses of apoptotic MCF-7 cells (annexin V-FITC positive cells) by annexin V-FITC staining and flow cytometry at 24 and 60 h after they were treated with vehicle, BMS (5 μM), IR (2 Gy) and BMS plus IR. Panel F: Analyses of apoptotic MCF-7 cells (sub-G0/1 cells) by PI staining and flow cytometry at 24 and 72 h after they were treated with vehicle, BMS (5 μM), IR (2 Gy) and BMS plus IR. The data are presented as mean ± SE (n =3) of percent sub-G1/0 cells. a, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; b, P < 0.001 vs. BMS 2.5 μM.

It has been assumed that inhibition of the IKK-NF-κB pathway increases the sensitivity of many types of tumor cells to IR and chemotherapy primarily via inhibition of the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (4, 6, 29, 30). To rule out this possibility, we analyzed apoptosis in irradiated MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or BMS by Annexin V staining and sub G0/1 cell analysis and found that MCF-7 cells were highly resistant to IR-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5E and F). This finding is in agreement with those reported previously (31), because MCF-7 cells are deficient in caspase 3 expression and insensitive to the induction of apoptosis by irradiation. Based on these findings, we assumed that BMS may sensitize MCF-7 cells to IR primarily via inhibition of the repair of DSBs in an apoptosis independent manner.

BMS Sensitizes MCF-7 Xenograft Tumors to IR

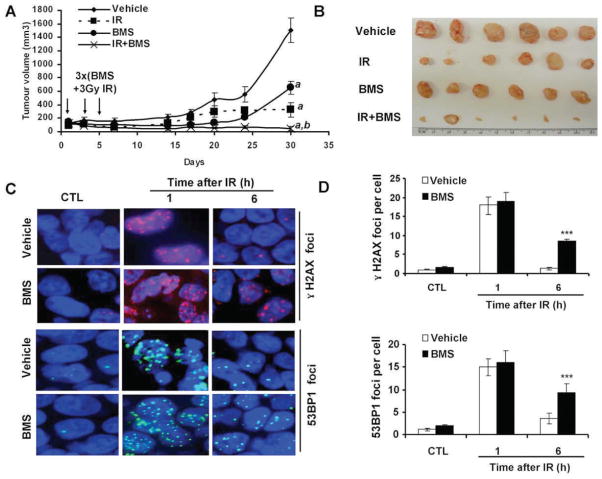

Since BMS can sensitize MCF-7 cells to IR in vitro, next we examined whether BMS can also sensitize MCF-7 cells to IR in vivo in a xenograft tumor mouse model. As shown in Fig. 6A, MCF-7 xenograft tumors grew rapidly in nude mice if the mice and tumor were not treated with BMS and irradiation. These untreated mice had to be humanly euthanized 30 days after the initiation of the experiment to reduce unnecessary pain associated with large tumors (>1,500 mm3). Exposure of the tumors to 3 fractionated and local X-ray irradiations or the administration of BMS to the mice slightly retarded the growth of the tumors (P < 0.001). However, the growth of the tumors was more significantly inhibited by the combined treatment with BMS and IR than of those treated with either BMS or IR alone (P < 0.001). This finding was confirmed when the tumors were dissected and compared at the end of the experiment (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

BMS sensitizes mouse xenograft tumor to IR. Panel A: The growth curves of MCF-7 xenograft tumors in mice after three treatments with vehicle, BMS (50 mg/kg, i.p.), local IR (3 Gy), or BMS + IR on days 1, 3 and 5 after the tumors had been established in the mice. The data are presented as mean ± SE of tumor volumes from 6 tumors/group. a, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; b, P < 0.001 vs. BMS or IR. Panel B: The picture to illustrate the tumor mass at the end of the study presented in panel A. Panel C: Representative photomicrographs (100× magnifications) of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 immunofluorescent staining. Panel D: average γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci/cell in tumor tissues harvested from the mice treated with vehicle or BMS (50 mg/kg, i.p.) before (CTL) or 1 and 6 h after exposure to 3 Gy local IR. The data are presented panel D as mean ± SE (n= 3 tumors/group) of 100 nuclei/tumor.

To examine whether the increased inhibition of MCF-7 tumor growth by the combined treatment with BMS and IR can be partially attributed to BMS-mediated inhibition of DSB repair, we analyzed the numbers of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci in tumors from control untreated mice and those at 1 and 6 h after exposure of the tumors to IR from mice pretreated with BMS or vehicle. As expected, tumors without exposure to IR exhibited very few γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci (Fig. 6C and D). The numbers of these foci increased in a similar degree at 1 h after irradiation in the tumors from BMS- or vehicle-treated mice. At 6 h after irradiation, the majority of the foci had disappeared in the tumors from vehicle-treated mice due to a rapid repair of IR-induced DSBs. However, the tumors from BMS-treated mice exhibited a significant delay in the repair of the DNA damage (P < 0.001). This observation confirms that BMS treatment also inhibits tumor cell repair of IR-induced DSBs in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Ionizing radiation is one of the most widely used therapeutic modalities for cancer. Unfortunately, some tumor cells are inherently more resistant to IR or can acquire radioresistance shortly after radiotherapy, in part due to activation of the IKK NF-κB pathway (29). Therefore, inhibition of the IKK NF-κB pathway has the potential to increase the therapeutic index of radiotherapy (29). Among various inhibitors of the IKK NF-κB pathway, IKKβ inhibitors have emerged as the most promising anti-tumor agents and novel tumor sensitizers for IR and chemotherapy (32). However, the mechanisms of their action have not been well studied, but are presumably attributed to the inhibition of NF-κB activity, which can increase tumor cell apoptosis by reducing the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (4, 6, 29, 30). The results from our recent studies revealed that IKKβ inhibitors, including BMS, can also inhibit the repair of IR-induced DSBs (3). More importantly, in the present study we showed that BMS could selectively inhibit HR most likely via down-regulation of several genes that participate in HR. This could lead to sensitization of MCF-7 cells to IR by augmenting IR-induced DDR but would be independent of the induction of apoptosis.

It has been suggested that tumor cells may preferentially depend on HR to repair DSBs compared with normal cells (34). Therefore, tumor cells may be more sensitive to the inhibition of the HR pathway by BMS than normal tissues. This suggestion is in agreement with the findings that BMS is a relatively safe agent that does not cause noticeable normal tissue damage in vivo (8–10), but is highly toxic to some tumor cells (34–36) and can selectively sensitize MCF-7 cells (3), but not mouse bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells, to IR in vitro (data not shown). In addition, our previous studies showed that BMS is almost equally potent as are the commonly used DNA-PK inhibitor NU7026 and ATM inhibitor KU55933 in inhibition of the repair of IR-induced DSBs (3). Furthermore, since BMS can inhibit not only the repair of DSBs, but also NF-κB-mediated induction of anti-apoptotic proteins (4–6), it is potentially more advantageous than these other DSB repair inhibitors as a tumor radiosensitizer.

However, the mechanisms by which BMS can selectively inhibit HR by down-regulating the expression of various HR genes remain to be elucidated. Since our previous studies showed that NF-κB-RelA is dispensable for IKKβ-dependent regulation of DSB repair (3), BMS may regulate HR gene expression by a non-IκB/NF-κB target of IKKβ (37). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that knockdown of IKKβ by a specific IKKβ shRNA down-regulated the expression of selective HR genes. In contrast, ectopic expression of a nondegradable IκBα mutant that inhibits NF-κB activity had no such effect. We anticipate that the identification of the specific IKKβ substrate(s) required for DSB repair and elucidation of the mechanisms by which BMS regulates the expression of HR genes and DSB repair will likely reveal novel targets for cancer therapy, which will be investigated in our future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Maria Jasin at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for providing us with the MCF-7/DR-GFP cells and pCBASceI plasmid DNA and Dr. Jeremy M. Stark at the City of Hope for the NHEJ reporter plasmid pim-EJ5-GFP. This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01CA86688 and R01CA122023) and the Arkansas Research Alliance Scholarship from the Arkansas Science & Technology Authority to DZ and by NIH (R37CA71382) and the Veterans Administration to MH-J.

References

- 1.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin SA, Lord CJ, Ashworth A. DNA repair deficiency as a therapeutic target in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu L, Shao L, An N, Wang J, Pazhanisamy S, Feng W, et al. IKKbeta regulates the repair of DNA double-strand breaks induced by ionizing radiation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baud V, Karin M. Is NF-kappaB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bednarski BK, Ding X, Coombe K, Baldwin AS, Kim HJ. Active roles for inhibitory kappaB kinases alpha and beta in nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated chemoresistance to doxorubicin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1827–35. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HJ, Hawke N, Baldwin AS. NF-kappaB and IKK as therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:738–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke JR, Pattoli MA, Gregor KR, Brassil PJ, MacMaster JF, McIntyre KW, et al. BMS-345541 is a highly selective inhibitor of I kappa B kinase that binds at an allosteric site of the enzyme and blocks NF-kappa B-dependent transcription in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1450–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillooly KM, Pattoli MA, Taylor TL, Chen L, Cheng L, Gregor KR, et al. Periodic, partial inhibition of IkappaB Kinase beta-mediated signaling yields therapeutic benefit in preclinical models of rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:349–60. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend RM, Postelnek J, Susulic V, McIntyre KW, Shuster DJ, Qiu Y, et al. A highly selective inhibitor of IkappaB kinase, BMS-345541, augments graft survival mediated by suboptimal immunosuppression in a murine model of cardiac graft rejection. Transplantation. 2004;77:1090–4. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000118407.05205.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntyre KW, Shuster DJ, Gillooly KM, Dambach DM, Pattoli MA, Lu P, et al. A highly selective inhibitor of I kappa B kinase, BMS-345541, blocks both joint inflammation and destruction in collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2652–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, Stark JM. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng A, Luberto C, Meier P, Bai A, Yang X, Hannun YA, et al. Sphingomyelin synthase as a potential target for D609-induced apoptosis in U937 human monocytic leukemia cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;292:385–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–81. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Nan L, Yu D, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Antisense anti-MDM2 oligonucleotides as a novel therapeutic approach to human breast cancer: in vitro and in vivo activities and mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3613–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mah LJ, El-Osta A, Karagiannis TC. gammaH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia. 2010;24:679–86. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noon AT, Shibata A, Rief N, Lobrich M, Stewart GS, Jeggo PA, et al. 53BP1-dependent robust localized KAP-1 phosphorylation is essential for heterochromatic DNA double-strand break repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:177–84. doi: 10.1038/ncb2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilch DR, Sedelnikova OA, Redon C, Celeste A, Nussenzweig A, Bonner WM. Characteristics of gamma-H2AX foci at DNA double-strand breaks sites. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81:123–9. doi: 10.1139/o03-042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olive PL, Banath JP. The comet assay: a method to measure DNA damage in individual cells. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:23–9. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:712–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moynahan ME, Jasin M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:196–207. doi: 10.1038/nrm2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharyya A, Ear US, Koller BH, Weichselbaum RR, Bishop DK. The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is required for subnuclear assembly of Rad51 and survival following treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23899–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolderson E, Tomimatsu N, Richard DJ, Boucher D, Kumar R, Pandita TK, et al. Phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates homologous recombination repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1821–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl M, Csernok A, Aydin S, Kreienberg R, Wiesmuller L, Gatz SA. Role of SIRT1 in homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:383–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westermark UK, Reyngold M, Olshen AB, Baer R, Jasin M, Moynahan ME. BARD1 participates with BRCA1 in homology-directed repair of chromosome breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7926–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7926-7936.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang F, Fan Q, Ren K, Andreassen PR. PALB2 functionally connects the breast cancer susceptibility proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1110–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavin MF, Kozlov S. ATM activation and DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:931–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tichy A, Vavrova J, Pejchal J, Rezacova M. Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) as a central regulator of radiation-induced DNA damage response. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2010;53:13–7. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2016.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Sethi G. Targeting transcription factor NF-kappaB to overcome chemoresistance and radioresistance in cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805:167–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakanishi C, Toi M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang XH, Edgerton S, Thor AD. Reconstitution of caspase-3 sensitizes MCF-7 breast cancer cells to radiation therapy. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1675–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee DF, Hung MC. Advances in targeting IKK and IKK-related kinases for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5656–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoms J, Bristow RG. DNA repair targeting and radiotherapy: a focus on the therapeutic ratio. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Amiri KI, Burke JR, Schmid JA, Richmond A. BMS-345541 targets inhibitor of kappaB kinase and induces apoptosis in melanoma: involvement of nuclear factor kappaB and mitochondria pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:950–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchs O. Transcription factor NF-kappaB inhibitors as single therapeutic agents or in combination with classical chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2010;3:98–122. doi: 10.2174/1874467211003030098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez-Guerra M, Roue G, Perez-Galan P, Alonso R, Villamor N, Montserrat E, et al. p65 activity and ZAP-70 status predict the sensitivity of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells to the selective IkappaB kinase inhibitor BMS-345541. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2767–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chariot A. The NF-kappaB-independent functions of IKK subunits in immunity and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.