Abstract

Viral breakthrough is related to poor adherence to medication in some chronic hepatitis B patients treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs). Our study aimed to examine how adherence to medication is associated with viral breakthrough in patients treated with NAs. A total of 203 patients (135 ETV and 68 LAM) were analyzed in this retrospective analysis. Physical examination, serum liver enzyme tests, and hepatitis B virus marker tests were performed at least every 3 months. We reviewed medical records and performed medical interviews regarding to patients' adherence to medication. Adherence rates <90% were defined as poor adherence in the present study. Cumulative viral breakthrough rates were lower in the ETV-treated patients than in the LAM-treated patients (P<0.001). Seven ETV-treated (5.1%) and 6 LAM-treated patients (8.8%) revealed poor adherence to medication (P=0.48). Among ETV-treated patients, 4 (3.1%) of 128 patients without poor adherence experienced viral breakthrough and 3 (42.8%) of 7 patients with poor adherence experienced viral breakthrough (P<0.001). Only 3 of 38 (7.8%) LAM-treated patients with viral breakthrough had poor adherence, a lower rate than the ETV-treated patients (P=0.039). Nucleoside analogue resistance mutations were observed in 50.0% of ETV- and 94.1% of LAM-treated patients with viral breakthrough (P=0.047). Viral breakthrough associated with poor adherence could be a more important issue in the treatment with especially stronger NAs, such as ETV.

Keywords: Adherence, Entecavir, Lamivudine, Hepatitis B, Viral Breakthrough.

INTRODUCTION

Two billion people have been exposed to hepatitis B virus (HBV), and 350-400 million people remain chronically infected worldwide. In Japan, the prevalence of HBV carriers is estimated at ~1% of the population, but HBV is a major health issue because it causes acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 1, 2.

Lamivudine (LAM) is a reverse-transcriptase inhibitor of HBV DNA polymerase that possesses excellent profile of safety and tolerability and causes inhibition of viral replication. LAM was the first nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) to be approved for antiviral treatment of hepatitis B patients 3, 4. Entecavir (ETV), a deoxyguanosine analogue, is a potent and selective inhibitor of HBV replication. The in vitro potency of ETV is 100- to 1,000-fold greater than that of LAM, and it has a selectivity index (concentration of drug required to reduce viable cell number by 50% [CC50] / concentration of drug required to reduce viral replication by 50% [EC50]) of approximately 8,000 5, 6. LAM (until 2005) and ETV (from 2006) have been used as first-line NAs for most patients with chronic hepatitis B in Japan. Most patients with chronic hepatitis B have been undergoing treatment for longer durations, and prolonged treatment is associated with increasing rates of viral breakthrough 7. It has been reported that not all cases are associated with resistance mutations 8, 9. We have also reported that some cases of viral breakthrough during ETV treatment were related to poor adherence to medication 10.

Adherence rates are usually lower in patients with long-term treatment regimens, such as for hypertension, than in patients with short-term regimens, such as for gastric ulcers 11. It has been reported that 74.8% of patients with hypertension were determined to have an adherence rate ≥80% 12, and that 55.3% of patients with chronic hepatitis B had an adherence rate >90% 8.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate whether drug adherence is related to viral breakthrough in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with LAM or ETV. We also investigated the pattern of poor adherence and suggested how adherence to medication could be improved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

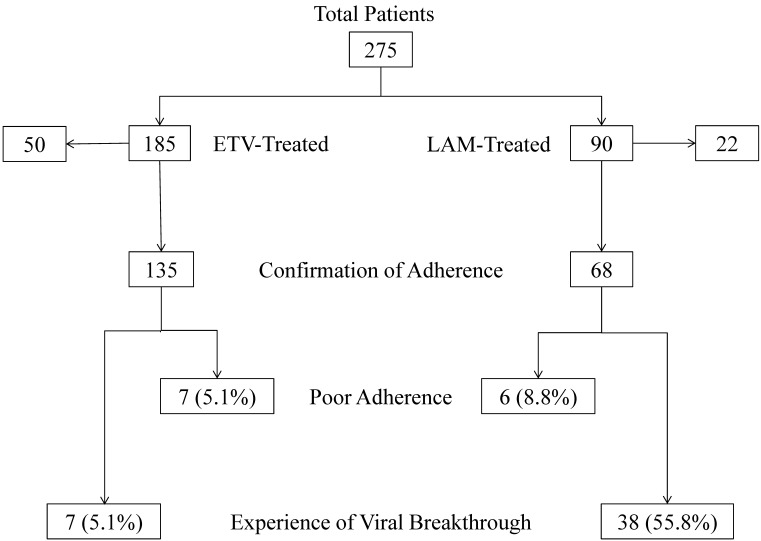

Two hundred seventy-five NA-treated naïve patients (185 ETV- and 90 LAM-treated patients), who were admitted to Chiba University Hospital between April 2000 and September 2011, were enrolled (Figure 1). Some of these patients had already been included in a previous report 10. Between November 2011 and April 2012, doctors performed medical interviews of those patients to determine their adherence to medication. Seventy-two patients (50 ETV- and 22 LAM-treated patients) were excluded from this retrospective analysis, because their adherence to medication could not be confirmed. One hundred thirty-five patients were administered 0.5 mg of ETV daily and 68 patients were administered 100 mg of LAM daily (Table 1). In all patients, serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBV DNA were positive. All patients had negative results for hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus antibodies. Physical examinations, serum liver enzyme tests, and HBV marker tests were performed at least every 3 months. The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chiba University, Graduate School of Medicine (No. 977).

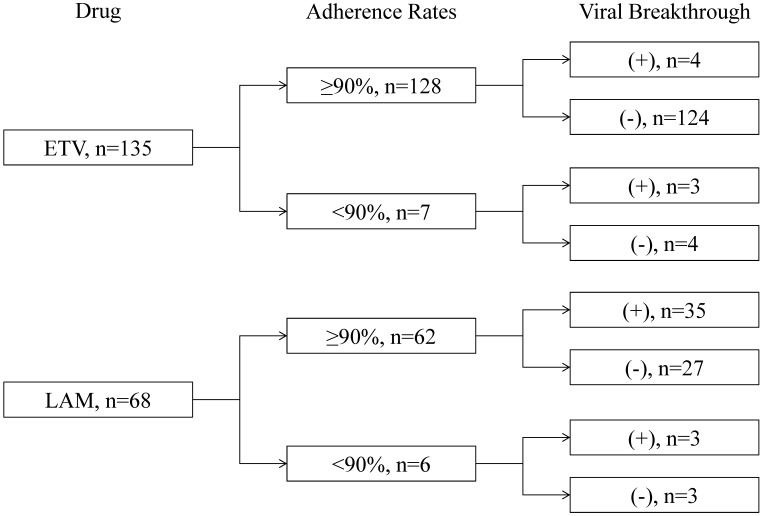

Figure 1.

Patients, adherence rates, and the prevalence of viral breakthrough in this study. ETV, entecavir; LAM, lamivudine.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| ETV | LAM | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 135 | 68 | |

| Age (years) | 51.7 ± 11.7 | 45.5 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male/female) | 83/52 | 49/19 | 0.135 |

| HBeAg (+/-) | 64/71 | 45/23 | 0.011 |

| Genotype (A/B/C/unknown) | 0/11/78/46 | 1/6/57/4 | 0.427 |

| HBV DNA (log IU/mL) (≤5.0/> 5.0/unknown) | 27/108/0 | 3/55/10 | 0.009 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 161 ± 195 | 353 ± 394 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (×104/mm3) | 16.3 ± 5.9 | 16.9 ± 7.0 | 0.556 |

| APRI | 2.49 ± 4.19 | 6.52 ± 6.98 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up period (months) | 26.9 ± 21.6 | 49.0 ± 39.7 | <0.001 |

ETV, entecavir; LAM, lamivudine; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; N.D., not determined; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase platelet ratio index. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Blood examinations

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, and platelet counts were reviewed in the present study. We also calculated the aspartate aminotransferase platelet ratio index [APRI: AST (IU/L)/ 35/platelet count (103/μL) x 100], which is significantly correlated with the staging of liver fibrosis, with a higher correlation coefficient than platelet count or AST level alone 13.

Detection of HBV markers

HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and anti-HBe antibody were determined by ELISA (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) or CLEIA (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan)14. HBV genotype was determined by ELISA (Institute of Immunology, Tokyo, Japan) 15. HBV DNA was measured by Roche Amplicor PCR assay (detection limits: 2.6 log IU/mL; Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan).

Follow-up period

The follow-up period ended when the NA was switched to another NA or another NA was added, or it was discontinued for various reasons.

Definition of adherence to medication

To obtain information regarding adherence to medication, we reviewed medical records. We also interviewed patients about their adherence to medication. We expressed the rate of adherence to medication as a percentage calculated by the number of days of taking a pill divided by the follow-up period (days). Adherence rates <90% were defined as poor adherence in the present study.

Definition of viral breakthrough

Viral breakthrough was defined as an increase of ≥ 1 log IU/mL in serum HBV DNA level from nadir.

Sequence analysis of HBV DNA

The YMDD motif was analyzed by PCR-ELMA in sera of patients who had experienced viral breakthrough, as reported by Kobayashi et al 16. HBV polymerase/reverse transcriptase (RT) substitutions were also analyzed in sera of ETV-treated patients who had experienced viral breakthrough. Briefly, HBV DNA was extracted from 100 μL of sera using SepaGene (Sanko Junyaku, Tokyo, Japan). Nested PCR was performed using LA Taq polymerase (Takara Bio, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) under the following conditions: 5-min denaturation at 94oC, 35 cycles with denaturation at 94oC for 40 s, annealing at 58oC for 1 min, and extension at 68oC for 1.5 min 2. An 862 base-pair fragment (nt 242-1103) containing the polymerase RT domain was amplified on the PCR Thermal Cycler Dice Model TP600 (Takara Bio). The primers for the first PCR were 5'-CAG AGT CTA GAC TCG TGG-3' (sense, nt 242-258) and 5'-GGC GAG AAA GTG AAAGCC-3' (antisense, nt 1103-1086). The PCR product was sequenced using the primers: 5'-TGG CTC AGT TTA CTAGTG CC -3' (nt 668-687) and 5'-GGC ACT AGT AAA CTGAGC CA-3' (nt 687-668), and these primers were also used for the second PCR. To prepare the sequence template, PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-ITR (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), and then sequenced using the BigDye(R) Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). Sequences were performed with Applied Biosystems 3730xl (Life Technologies) 17.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were compared by Student's t-test or Welch's t-test. Categorical variables were compared by chi-square test or Fisher's exact probability test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate viral breakthrough rates. Baseline was taken as the date when the first dose of LAM or ETV was taken. Statistical significance was considered at a P-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of patients

Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. In ETV-treated patients, the age was higher, the prevalence of HBeAg-negative patients was higher, HBV DNA was lower, ALT levels were lower, and APRI was lower (ie., liver fibrosis was milder) than in LAM-treated patients. HBV genotype C was dominant in both groups. The follow-up period in ETV-treated patients was shorter than that in LAM-treated patients, based on the fact that ETV was a newer drug and many ETV-treated patients had started treatment more recently.

Adherence to medication, and viral breakthrough between ETV- and LAM-treated patients

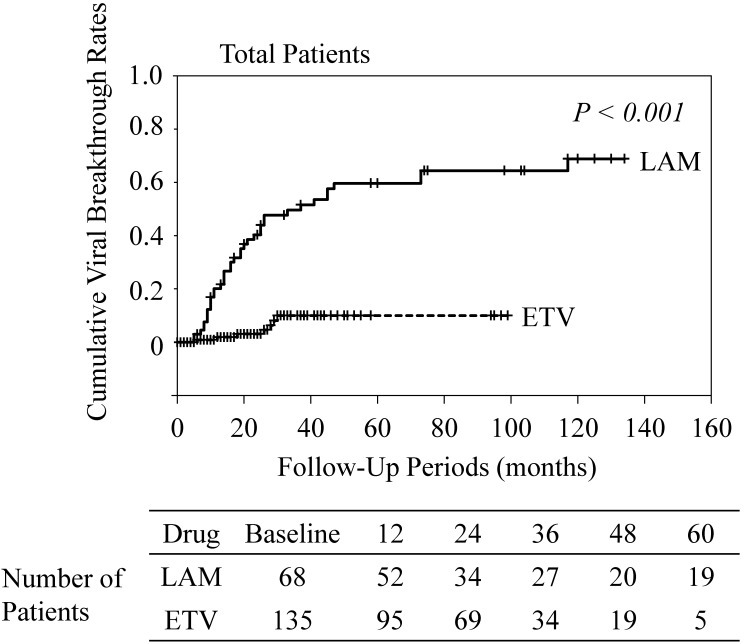

Most patients presented good adherence to medication in the present study. Seven ETV-treated (5.1%) and 6 LAM-treated patients (8.8%) had poor adherence (Figure 1). The number of patients with poor adherence was not significantly different between the ETV- and LAM-treated groups (P=0.48). The characteristics of the 13 patients with poor adherence are shown in Table 2. Cumulative viral breakthrough rates were lower in the ETV-treated patients than in the LAM-treated patients (P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Patients with poor adherence to medication.

| Case | Drug | Adherence rate (%) |

Age (years) |

Gender | Genotype | HBeAg | HBV DNA (log IU/mL) |

ALT (IU/L) |

APRI | HBeAg- seronegative |

HBV DNA negativity |

VT | Duration of treatment before VT (months) |

Resistance mutations |

Treatment after VT | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ETV | 50 | 55 | F | B | - | 3.8 | 16 | 0.33 | N.A. | + | + | 6 | - | ETV | good |

| 2 | ETV | 75 | 49 | M | C | + | 7.3 | 107 | 1.60 | + | + | + | 28 | + | LAM+ADV | good |

| 3 | ETV | 85 | 38 | M | C | + | 6.9 | 59 | 2.80 | - | + | + | 29 | N.D. | ETV | good |

| 4 | ETV | 80 | 39 | M | C | + | 5.8 | 51 | 0.63 | + | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | ETV | good |

| 5 | ETV | 85 | 37 | F | C | + | 6.9 | 160 | 2.25 | + | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | ETV | good |

| 6 | ETV | 85 | 66 | M | N.D. | + | 7.7 | 68 | 0.95 | - | - | - | N.A. | N.A. | ETV | good |

| 7 | ETV | 85 | 38 | M | C | + | 6.5 | 478 | 7.94 | - | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | ETV | good |

| 8 | LAM | 50 | 47 | F | C | + | 6.5 | 455 | 2.54 | + | + | + | 45 | - | LAM | good |

| 9 | LAM | 80 | 36 | M | C | + | 7.0 | 110 | 4.25 | + | + | + | 41 | + | LAM+ADV | good |

| 10 | LAM | 85 | 23 | M | C | + | >7.6 | 161 | 3.53 | - | + | + | 11 | - | cessation | flare |

| 11 | LAM | 85 | 32 | M | C | + | >7.6 | 343 | 1.30 | + | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | LAM | good |

| 12 | LAM | 85 | 54 | F | C | - | 4.1 | 196 | 2.68 | N.A. | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | LAM | good |

| 13 | LAM | 85 | 36 | M | C | + | 6.7 | 1576 | 15.78 | + | + | - | N.A. | N.A. | LAM | good |

Cases 2 and 3 had already been included in a previous report.10 HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid, ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase platelet ratio index; VT, viral breakthrough; ETV, entecavir; LAM, lamivudine; ADV, adefovir; F, female; M, male; N.D., not determined; N.A., not available; HBeAg-seronegative, conversion to HBeAg-seronegative after administration of a nucleoside analogue; HBV DNA negativity, achieving HBV DNA negativity after administration of a nucleoside analogue; flare, fluctuating ALT after treatment after VT.

Figure 2.

Cumulative viral breakthrough rates. ETV, entecavir; LAM, lamivudine.

Viral breakthrough in HBeAg-positive and -negative patients

Among the LAM-treated patients, cumulative viral breakthrough rates in HBeAg-positive patients at baseline (n=45; 25.0% at 1 year, 55.1% at 3 years, and 67.0% at 5 years) were similar to those in HBeAg-negative patients at baseline (n=23; 9.5% at 1 year, 38.2% at 3 years, and 44.4% at 5 years; P=0.16). Among the ETV-treated patients, cumulative viral breakthrough rates in HBeAg-positive patients at baseline (n=64; 2.2% at 1 year, 18.1% at 3 years, and 18.1% at 5 years) were also similar to those in HBeAg-negative patients at baseline (n=71; 1.6% at 1 year, 1.6% at 3 years, and 1.6% at 5 years; P=0.050).

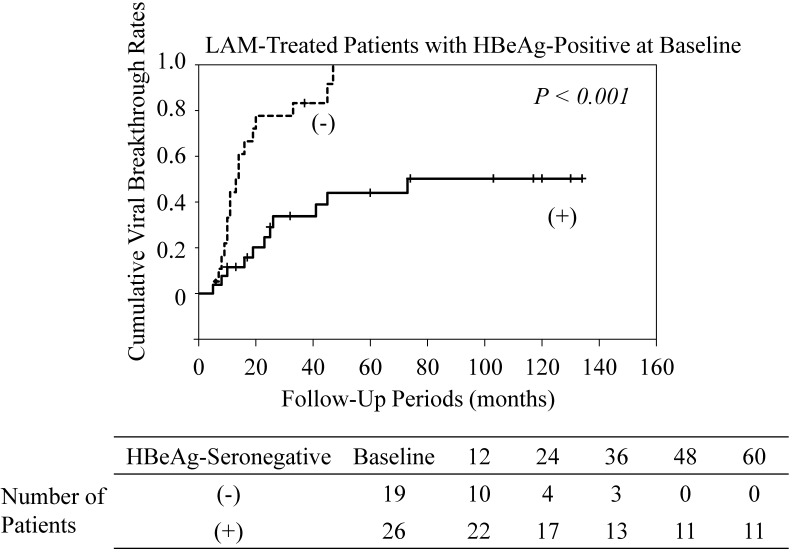

Among the LAM-treated patients who were HBeAg-positive at baseline, cumulative viral breakthrough rates in patients who converted to HBeAg-seronegative were lower than those in patients who maintained HBeAg seropositivity (P<0.001) (Figure 3). All LAM-treated patients who did not become HBeAg-seronegative experienced viral breakthrough. Among the ETV-treated patients who were positive for HBeAg at baseline, conversion to HBeAg seronegativity did not affect the rate of viral breakthrough (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cumulative viral breakthrough rates in lamivudine (LAM)-treated patients with HBe antigen (HBeAg)-positive at baseline. (-), maintaining HBeAg seropositivity; (+), conversion to HBeAg-seronegative.

There were no differences in HBV viral loads at study entry between HBeAg-positive patients with and without viral breakthrough. There were also no differences in HBV viral loads between HBeAg-negative patients with and without viral breakthrough.

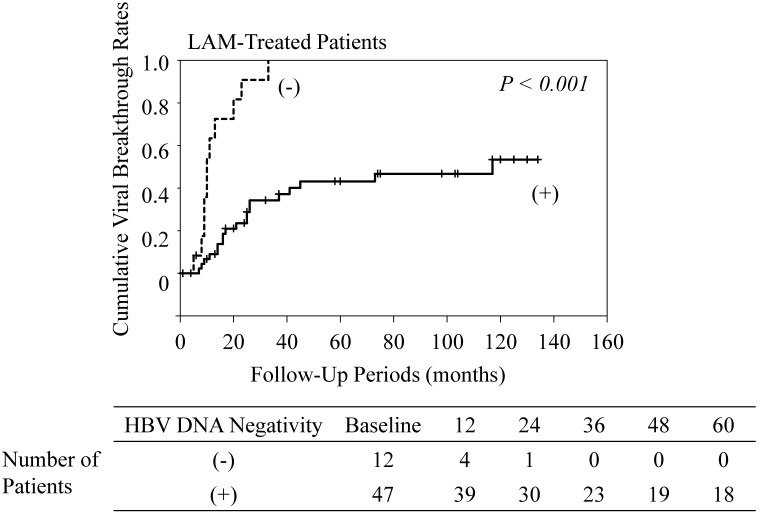

Viral breakthrough in patients who achieved, and did not achieve HBV DNA negativity

Among the LAM-treated patients, cumulative viral breakthrough rates in patients who did not achieve HBV DNA negativity were higher than in those who achieved HBV DNA negativity (P<0.001) (Figure 4). All patients who did not achieve HBV DNA negativity experienced viral breakthrough. In contrast, among the ETV-treated patients, cumulative viral breakthrough rates in patients who did not achieve HBV DNA negativity were similar to the rates in those who achieved HBV DNA negativity (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Cumulative viral breakthrough rates in lamivudine (LAM)-treated patients who achieved HBV DNA negativity and those who did not. (-), maintaining HBV DNA positivity; (+), achieving HBV DNA negativity. HBV DNA negativity was unknown in 9 patients because of lack of data.

Correlation between adherence to medication and viral breakthrough

We also compared viral breakthrough rates according to adherence to medication. Among 62 LAM-treated patients who did not have poor adherence, 35 patients (56.4%) experienced viral breakthrough (Figure 5). Among 6 LAM-treated patients with poor adherence, 3 patients (50.0%) experienced viral breakthrough. In LAM treatment, poor adherence did not contribute to viral breakthrough (P=0.89). However, among 128 ETV-treated patients who did not have poor adherence, 4 patients (3.1%) experienced viral breakthrough. Among 7 ETV-treated patients with poor adherence, 3 patients (42.8%) experienced viral breakthrough. In the treatment with ETV, poor adherence contributed to viral breakthrough (P<0.001).

Figure 5.

Association between adherence to medication and viral breakthrough.

Resistance mutations

Resistance mutations were analyzed in some patients who experienced viral breakthrough. They were analyzed in 34 LAM-treated patients and 4 ETV-treated patients (Table 3). Thirty-two LAM-resistant patients had 10 YVDD, 17 YIDD, and 5 YV/IDD motifs, and 2 ETV-resistant patients had two YVDD motifs. Resistance mutations were not observed in 2 LAM-treated patients (5.8%) and 2 ETV-treated patients (50.0%) (P=0.047).

Table 3.

Patients with viral breakthrough.

| ETV | LAM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence rate | ≥90% | <90% | ≥90% | <90% |

| Resistance mutation (+) | 1 | 1 | 31 | 1 |

| L180M | 1 | 1 | N.D. | N.D. |

| T184A | 1 | 0 | N.D. | N.D. |

| S202G | 0 | 1 | N.D. | N.D. |

| M204V | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| M204I | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| M204V/I | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| M250V | 0 | 0 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Resistance mutation (-) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

ETV, entecavir; LAM, lamivudine; N.D., not determined. Numbers of amino acid positions were according to Refs. 2 and 10.

DISCUSSION

The current study found that ETV-treated patients were not likely to acquire any resistance mutations and experience an ALT flare. Therefore, patients with poor liver residual function, such as liver cirrhosis, were likely to be administered ETV rather than LAM. Unexpectedly, HBsAg loss was observed in 3 of 28 LAM-treated patients without viral breakthrough (10.7%) and in 3 of 118 ETV-treated patients without viral breakthrough (2.5%). Long-term treatment with these drugs might result in HBsAg loss, although several reports have stated that one-year treatment with peg-interferon led to more HBsAg loss than these drugs 18-25.

In the current study, adherence to medication of most patients was excellent. The reasons for this might be as follows: (1) Our setting was a University Hospital, and this may have strengthened their will to succeeded with the treatment; (2) some patients with poor adherence might have been excluded because they did not see a doctor during the interview period; and (3) the rate of adherence to medication was based on patient self-assessment. A previous report showed that adherence might be underestimated by the Medication Event Monitoring System, a system that automatically records whenever a drug bottle is opened, and might be overestimated by pill counting and at interviews 26. We classified the adherence rate as good at 90% or more, and as poor at less than 90%. However, we could not prove any significant influence of this classification on viral breakthrough as well as resistance mutation.

In the 13 patients with poor adherence (Table 2), we examined the reasons for their failure to take the pills. All 13 patients displayed some carelessness about taking pills. Two ETV-treated patients did not see a doctor and could not take pills continuously for a certain period of time, which particularly appeared to affect their viral breakthrough.

In LAM-treated patients, conversion of HBeAg to seronegative and achieving HBV DNA negativity was one of the important factors for successful treatment (Figures 3 & 4). In contrast, among ETV-treated patients, maintaining HBeAg seropositivity or HBV DNA positivity was not associated with viral breakthrough in the present study. Because of the stronger effect of ETV, it has been reported that long-term ETV treatment leads to a viral response in the vast majority of patients with detectable HBV DNA after 48 weeks 27. Moreover, in the current study, poor adherence to medication was a major factor of viral breakthrough in the ETV-treated patients, but not in the LAM-treated patients. Ha et al. 9 also reported that medication non-adherence is likely to be a more important contributor to treatment failure than antiviral resistance, especially with new anti-HBV agents such as ETV and tenofovir. In LAM-treated or ETV-treated patients, viral breakthrough without resistance mutations might occur to some degree because of poor adherence to medication. In the present study, in LAM-treated patients, emergence of viral breakthrough with resistance mutations was common. Therefore, viral breakthrough due to poor adherence to LAM might not be important, compared with ETV-treated patients. However, in ETV-treated patients, viral breakthrough with resistance mutations was rare, and therefore, viral breakthrough due to poor adherence to ETV might be important.

In conclusion, viral breakthrough associated with poor adherence could be an important issue in the treatment with strong nucleoside analogues, such as ETV.

Acknowledgments

We are all thankful to our colleagues at the liver unit of our hospitals who cared for the patients described herein.

Funding

This work was supported by grants for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (TK and SN), grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (TK and OY), and a grant from Chiba University Young Research-Oriented Faculty Member Development Program in Bioscience Areas (TK).

Contributors

HK, TK, FI, and OY designed the study. HK, TK, MA, TC, HM, KF, FK, FI, FN and OY saw patients and conducted the interview. HK, TK, WS, and SN analyzed the data. HK and TK drafted the paper and all authors approved the paper.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ETV

entecavir

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- NA

nucleos(t)ide analogue

- LAM

lamivudine

References

- 1.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu S, Fukai K, Imazeki F. et al. Initial virological response and viral mutation with adefovir dipivoxil added to ongoing Lamivudine therapy in Lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1207–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1423-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dienstag JL, Perrillo RP, Schiff ER. et al. A preliminary trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1657–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NW. et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Innaimo SF, Seifer M, Bisacchi GS. et al. Identification of BMS-200475 as a potent and selective inhibitor of hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1444–1448. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ono SK, Kato N, Shiratori Y. et al. The polymerase L528M mutation cooperates with nucleotide binding-site mutations, increasing hepatitis B virus replication and drug resistance. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:449–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI11100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto Y, Suzuki F, Hirakawa M. et al. Clinical and virological effects of long-term (over 5 years) lamivudine therapy. J Med Virol. 2010;824:684–691. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chotiyaputta W, Peterson C, Ditah FA. et al. Persistence and adherence to nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;54:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha NB, Ha NB, Garcia RT. et al. Medication nonadherence with long-term management of patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2423–31. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamezaki H, Kanda T, Wu S. et al. Emergence of entecavir-resistant mutations in nucleos(t)ide-naive Japanese patients infected with hepatitis B virus: virological breakthrough is also dependent on adherence to medication. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1111–1117. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.584898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288:2880–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bramley TJ, Gerbino PP, Nightengale BS. et al. Relationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:239–245. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishibashi H, Maruyama H, Takahashi M. et al. Assessment of hepatic fibrosis by analysis of the dynamic behaviour of microbubbles during contrast ultrasonography. Liver Int. 2010;30:1355–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu S, Kanda T, Imazeki F. et al. Hepatitis B virus e antigen downregulates cytokine production in human hepatoma cell lines. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:467–476. doi: 10.1089/vim.2010.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usuda S, Okamoto H, Iwanari H. et al. Serological detection of hepatitis B virus genotypes by ELISA with monoclonal antibodies to type-specific epitopes in the preS2-region product. J Virol Methods. 1999;80:97–112. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi S, Shimada K, Suzuki H. et al. Development of a new method for detecting a mutation in the gene encoding hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase active site (YMDD motif) Hepatol Res. 2000;17:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanda T, Jeong SH, Imazeki F. et al. Analysis of 5' nontranslated region of hepatitis A viral RNA genotype I from South Korea: comparison with disease severities. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan HL, Leung NW, Hui AY. et al. A randomized, controlled trial of combination therapy for chronic hepatitis B: comparing pegylated interferon-α2b and lamivudine with lamivudine alone. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:240–250. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaw YF, Jia JD, Chan HL. et al. Shorter durations and lower doses of peginterferon alfa-2a are associated with inferior hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates in hepatitis B virus genotypes B or C. Hepatology. 2011;54:1591–1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.24555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buster EH, Flink HJ. et al. Sustained HBeAg and HBsAg loss after long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with peginterferon α-2b. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:459–467. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong VW, Wong GL, Yan KK. et al. Durability of peginterferon alfa-2b treatment at 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:1945–1953. doi: 10.1002/hep.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papadopoulous VP, Chrysagis DN, Protopapas AN. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b as monotherapy or in combination with lamibudine in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: a randomised study. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR56–CR61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcellin P, Bonino F, Lau GK. et al. Sustained response of hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients 3 years after treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2169–2179. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG. et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:968–977. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A. et al. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: adaptation is not needed for the majority of naïve patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011;54:443–451. doi: 10.1002/hep.24406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]