Abstract

Cross-sensitization in the pelvis may contribute to etiology of functional pelvic pain disorders such as interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS). Increasing evidence suggests the involvement of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors in the development of neurogenic inflammation in the pelvis and pelvic organ cross-sensitization. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that desensitization of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder can minimize the effects of cross-sensitization induced by experimental colitis on excitability of bladder spinal neurons. Extracellular activity of bladder neurons was recorded in response to graded urinary bladder distension (UBD) in rats pretreated with intravesical resiniferatoxin (RTX, 10−7 M). Colonic inflammation was induced by intracolonic instillation of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS). The duration of excitatory responses to noxious UBD during acute colonic inflammation (3 days post-TNBS) was significantly shortened in the group with RTX pretreatment (25.37±.5 s, n=49) when compared to the control group (35.1±4.2 s, n=43, p≤0.05). The duration of long-lasting excitatory responses, but not short-lasting responses of bladder spinal neurons during acute colitis was significantly reduced by RTX from 52.9±6.6 s (n=21, vehicle group) to 34.4±2.1 s (RTX group, n=21, p≤0.05). However, activation of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder prior to acute colitis increased the number of bladder neurons receiving input from large somatic fields from 22.7% to 58.2% (p≤0.01). The results of our study provide evidence that intravesical RTX reduces the effects of viscerovisceral cross-talk induced by colonic inflammation on bladder spinal neurons. However, RTX enhances the responses of bladder neurons to somatic stimulation, thereby limiting its therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Spinal neurons, Chronic pelvic pain, Intravesical vanilloids, Bladder pain syndrome

1. Introduction

Functional pelvic pain is a symptom of several disorders of the genitourinary tract including interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS). Bladder pain and enhanced pelvic sensitivity in patients with IC/BPS may be perceived as coming from the bladder itself, or could be a result of increased afferent input from an adjacent visceral or overlying somatic structure due to development of cross-organ sensitization (Brumovsky and Gebhart, 2010; Malykhina, 2007). The occurrence of cross-sensitization is stimulus and time dependent and is mainly under the control of the central (central sensitization) and autonomic (peripheral sensitization) nervous systems (Brumovsky and Gebhart, 2010). Second order neurons in the spinal cord receive inputs from primary sensory neurons located in the dorsal root ganglia innervating various visceral and somatic structures. Convergent spinal neurons have been identified in many species reaching 35–75% of all second order neurons and were proven to play a significant role in central mechanisms of cross-organ sensitization (Chandler et al., 2002; DeGroat, 1971; Qin et al., 2005). Our group previously demonstrated an enhanced excitability of second order neurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord with convergent colon/ bladder and bladder only inputs upon cross-sensitization in the pelvis induced by colonic inflammation (Qin et al., 2005). However, the mechanisms by which inflammation in the colon affects the electrophysiological properties of bladder spinal neurons are still unclear.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is a polymodal ion channel involved in nociceptive signaling and is expressed in many peripheral organs including the colon and urinary bladder with the highest level of expression in primary sensory neurons projecting to the pelvic viscera (Avelino and Cruz, 2006; Birder et al., 2001; Hwang et al., 2005). Activation of TRPV1 receptors by potent agonists such as resiniferatoxin (RTX) may increase action potential firing in sensory afferents along with enhanced sensitivity to peripheral noxious stimuli followed by a prolonged period of receptor desensitization (Caterina et al., 1997; Wong and Gavva, 2009). The ability of vanilloids to reduce pelvic pain was tested in patients with IC/BPS (Chen et al., 2005; Payne et al., 2005). The results of these clinical trials revealed a substantial number of patients who did not respond to the treatment, and often reported relocation of painful sites and/or an increase in overall abdominal pain after RTX treatment. It is possible that peripheral neurogenic inflammation together with central sensitization played a role in generation and maintenance of IC/BPS symptoms in these patients, especially bladder pain and urgency (Hanno et al., 2011). Recent studies showed that sensitization of one afferent pathway can lead to heterosynaptic facilitation and may alter processing of inputs from other neurons (Lamb et al., 2006), suggesting that intravesical RTX can potentially lead to viscerosomatic hypersensitivity due to convergence of visceral and somatic afferent pathways in the spinal cord.

The objective of the current study was to investigate the mechanisms and the role of TRPV1 in viscerovisceral and viscerosomatic cross-talk at the level of the lumbosacral spinal cord. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that desensitization of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder prior to the induction of experimentally induced cross-sensitization by transient colonic inflammation can reduce or inhibit hyperexcitability of bladder spinal neurons resulted from colon–bladder cross-talk. Additionally, we also aimed to compare the effects of acute vs. resolved colonic inflammation on excitability of bladder spinal neurons, as well as to determine the effects of intravesical RTX on the responsiveness of convergent spinal neurons receiving input from the urinary bladder and overlying somatic fields.

2. Results

2.1. Histological and biochemical evaluation of the distal colon and urinary bladder after intracolonic and intravesical treatments

Analysis of H&E stained cross-sections of the distal colon was performed to assess the structural changes in the colonic wall induced by TNBS instillation. Fig. 1A includes representative cross-sections from control and experimental groups of rats. No detectable structural changes in the colonic wall were observed in the control group (Fig. 1A, top panel). However, the presence of crypt segmentation, local infiltration and thickening of the muscle layer were detected at day 3 after TNBS treatment (Fig. 1A, middle panel) confirming the development of acute colitis. By day 30 post-TNBS, the cytoarchitecture of the colon did not significantly differ from the control group (Fig. 1A, bottom panel). The development of acute colitis at day 3 post-TNBS treatment was also confirmed by a 4.5-fold increase in MPO concentration in the distal colon without significant changes in the groups with vehicle (control) and intravesical RTX (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Histological evaluation of inflammation in the distal colon and expression of TRPV1 protein. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the distal colon from the following groups of animals: control (top panel), acute colonic inflammation (middle panel, TNBS – 3 days) and resolved inflammation (bottom pane, TNBS – 30 days, 4×). Please note that only group with acute colitis (3 days post-TNBS) showed significant tissue damage including sites of infiltration, thickening of the muscle layer, and disruption of the colonic crypts. (B) Western blotting with anti-TRPV1 antibody of the proteins isolated from the urothelium (Uro), detrusor smooth muscle (DSM), and distal colon (Colon). The amount of protein loaded per lane was 40 μg for all tissues. Alpha tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Normalized TRPV1/α-tubulin values in different groups of animals (N=4 in each group). Ctrl-vehicle in the bladder, RTX (B) – RTX in the bladder (3 days post-RTX), RTX(B)+TNBS(C) – RTX in the bladder followed by intracolonic TNBS (3 days post-TNBS treatment). * – p≤0.05 between the groups. (D) The levels of MPO in the distal colon in the control groups and 3 days after the induction of TNBS colitis (acute phase).

To evaluate the effects of intravesical RTX on the expression of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder and distal colon, Western blotting with anti-TRPV1 antibodies was performed. The control group of rats underwent vehicle instillation in the bladder (N=4), the RTX group had intravesical RTX treatment (N=4, 3 days) and the RTX+TNBS group had RTX in the bladder followed by intracolonic TNBS (N=4, 3 days, acute colitis). Fig. 1B shows the results of the Western blot with anti-TRPV1 in the bladder urothelium, detrusor muscle, and distal colon. A band of 95–100 kDa corresponding to TRPV1 was observed in all tested tissues as previously reported (Birder et al., 2001; Charrua et al., 2009; Lazzeri et al., 2004). Alpha tubulin was run as a loading control and did not change among the groups. The normalized TRPV1/α-tubulin values for each tested tissue are presented in Fig. 1C. These results provide evidence for a significant decrease in TRPV1 expression after intravesical treatment with RTX in the urothelium and DSM without changes in the distal colon. Acute colitis (TNBS, 3 days), however, had no effect on the expression of TRPV1 in the urinary bladder, but increased the level of the protein in the distal colon by 2-fold (Fig. 1C, p≤0.05).

2.2. Effects of acute and resolved colitis on electrophysiological characteristics of bladder spinal neurons after pretreatment with intravesical RTX

In rats with acute experimental colitis noxious UBD (1.5 ml) changed the activity of 64/135 (47%) neurons, which was not significantly different from the percentage of neurons responding to UBD in animals pretreated with intravesical RTX (73/139, 52%). The same ratio between UBD responsive and non-responsive neurons was observed in groups with and without intravesical RTX upon resolution of acute experimental colitis. Histological analysis of the regional distribution of the UBD responsive neurons was done based on the location of lesions made at the end of electrophysiological recordings as previously described (Qin et al., 2005). Neither RTX treatment nor duration of experimental colitis (acute or resolved) affected the location sites of UBD responsive neurons that were detected in laminae I–III, V–VII, and X (data not shown).

On the basis of activity of UBD-responsive cells, bladder spinal neurons were divided into the following two groups: silent neurons with low spontaneous activity (<0.5 imp/s) and active neurons with high spontaneous activity (<0.5 imp/s). The ratio of active/total recorded neurons in rats with acute colitis was not different between animals instilled with either vehicle (38/43, 88%) or RTX (41/49, 84%) in the bladder. The same tendency was noted in the vehicle and RTX groups of rats with resolved experimental colitis. However, pretreatment with intravesical RTX significantly reduced the duration of excitatory responses from 35.1±4.2 s (vehicle, n=43) to 25.3±1.5 s (RTX, n=49, p≤0.05, Fig. 2A) in response to noxious UBD in the group with acute colitis. The duration of excitatory responses was not affected by RTX treatment in rats with resolved colitis (Fig.2B).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the duration of excitatory and inhibitory responses induced by UBD in bladder neurons. (A) Duration of excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) responses in the groups of animals with intravesical vehicle vs. intravesical RTX followed by acute experimental colitis. (B) Excitability of bladder spinal neurons recorded from rats with resolved TNBS-induced colitis. * – p≤0.05 between the groups.

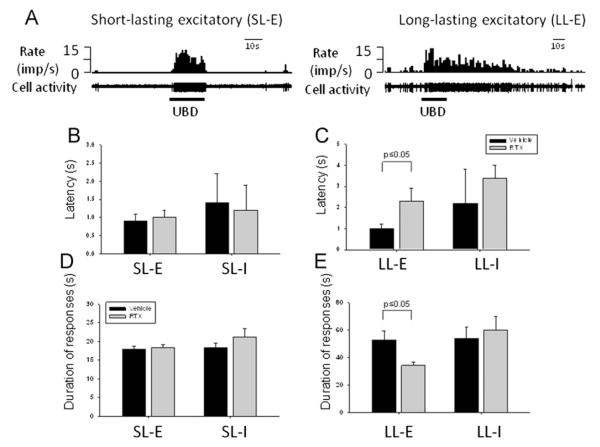

2.3. Short and long lasting responses of bladder neurons after experimental colitis

Based on the recovery time of neuronal activity to control levels following noxious UBD (1.5 ml), neurons excited by UBD were further subdivided into two groups: neurons with recovery time ≤5 s were classified as short-lasting (SL) and neurons with recovery time >5 s were classified as long-lasting (LL, Fig. 3). A quantitative comparison of these neurons showed that intravesical RTX did not change the latency (Fig. 3B) or duration (Fig. 3D) of bladder neurons with SL excitatory (SL-E) activity profile in rats with acute colitis. However, intravesical RTX significantly increased the latency period from 1.0±0.2 s (n=21, vehicle) to 2.3±0.6 s (RTX, n=21, p<0.05) in LL excitatory (LL-E) neurons during acute colitis (Fig. 3C). In addition, the mean duration of LL-E responses was substantially reduced from 54.9±6.6 s (vehicle) to 34.4±2.1 s (RTX, p<0.05, Fig. 3E) in the same group of animals. No differences in RTX and control groups were observed for LL-E and SL-E neurons in rats with resolved experimental colitis.

Fig. 3.

Short- and long-lasting excitatory and inhibitory responses of bladder spinal neurons in rats with and without intravesical RTX followed by acute colonic inflammation. (A) Examples of bladder neurons with short-lasting excitatory (SL-E) and long-lasting excitatory (LL-E) responses. In these panels top trace is the rate histogram and bottom trace shows raw recordings of cell acitivity. (B) Latency of short-lasting excitatory (SL-E) and inhibitory (SL-I) neurons in rats with intravesical RTX during acute experimental colitis. (C) Comparison of latency of long-lasting excitatory (LL-E) and inhibitory (LL-E) neurons in animals with acute colonic inflammation. (D) Duration of short-lasting excitatory and inhibitory bladder neurons in rats with colitis. (E) Duration of long-lasting excitatory and inhibitory bladder neurons in animals with acutely inflamed colon. Imp/s – number of action potentials per second.

In some neurons, neuronal responses to graded UBD (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 ml, 20 s for each distension) were examined. Analysis of neuronal responses to increasing volumes of UBD did not reveal significant differences during acute nor resolved experimental colitis (data not shown). Based on the threshold sensitivity of activated responses to applied UBD, lumbosacral spinal neurons were subdivided into two groups: low-threshold (LT) neurons that initially responded to a distending volume ≤0.5 ml and high-threshold (HT) neurons that responded to ≥1.0 ml of distending volume (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment with RTX did not affect the percentage of LT neurons activated by UBD. However, HT neurons with excitatory responses to UBD were more frequently recorded in rats pretreated with RTX (50/73, 69%) than in vehicle treated animals (32/64, 50%, p≤0.05, Fig. 4B). These changes were not observed between the groups with resolved colonic inflammation (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Responses of low thereshold (LT) and high threshold (HT) bladder neurons to increasing volumes of UBD in rats with experimental colitis. (A) A recording from a low threshold excitatory (LT-E) neuron during innocuous (0.5 ml), subnoxious (1.0 ml) and noxious (1.5 ml) UBD (top left panel). Top right panel shows the activity of high threshold excitatory (HT-E) neuron in response to graded UBD. Lower panel includes recordings from low threshold inhibitory (LT-I, left) and high threshold excitatory-inhibitory (HT-EI, right) spinal neurons. (B) Number of total LT and HT neurons in rats with acute colitis pretreated with intravesical RTX. Please note that pretreatment with RTX increased the number of HT neurons in this group (* – p≤0.05 to vehicle control). (C) Comparison of total population of LT and HT neurons in rats with resolved colitis.

2.4. Effects of RTX on electrophysiological activity of superficial and deeper bladder neurons

Spinal UBD-responsive neurons recorded at a depth of ≤300 μm from the dorsal surface of the spinal cord were classified as superficial neurons, whereas neurons below 300 μm (to 1200 μm) were classified as deeper neurons. Noxious UBD (1.5 ml) caused differential responses of superficial and deeper neurons to intravesical treatment. The same four patterns of neuronal responses (E, I, E–I, and I–E) were observed in both superficial and deep subpopulations of neurons. Nineteen out of 47 superficial tested neurons (40%) were excited by pretreatment with RTX in comparison to 7 out of 28 neurons (25%) in the group with vehicle instillation, however, this change did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05). Additionally, electrophysiological characteristics of these neurons were not affected by RTX treatment neither in the group with acute nor resolved colitis. Analysis of electrophysiological parameters of deeper excitatory neurons activated by UBD revealed a significant decrease in the duration of responses caused by RTX pretreatment in rats with acute colitis. The average duration of excitatory responses in deeper (laminae V–VII, X) gray matter was 35.8±4.6 s (n=36) in the vehicle group vs. 24.7±1.9 s in RTX group (n=30, p≤0.05). Spontaneous activity of bladder neurons, latency, and excitatory activity did not differ in animals with resolved colitis.

2.5. Intravesical RTX increased the number of bladder neurons with larger somatic field input

In rats with acute colitis, 56/64 (88%) bladder neurons responded to somatic field stimulation. In animals with intravesical RTX the proportion of convergent (receiving input from both visceral and somatic fields) neurons (67/73, 86%) was similar to the population in the vehicle group (Table 1). The same percentage of bladder neurons responded to somatic field stimulation in rats with resolved colitis (with and without RTX treatment). Fig. 5A shows examples of LT, WDR and HT neuronal responses. Somatic receptive fields were generally found on the scrotum, perianal region, lower back, hindlimb, and areas around the tail (Fig.5 B). In the group with acute experimental colitis, large somatic fields were found more frequently for viscerosomatic spinal neurons in rats pretreated with RTX in comparison to somatic fields mapped in vehicle treated animals (Fig. 5C). Out of 66 viscerosomatic convergent neurons in the group with vehicle, only 15 neurons (23%) were activated by stimulation of a large somatic area whereas after RTX the number of these neurons reached 58% (39 out of 67 recorded, p≤0.01, Fig. 5C). In the group with resolved colitis, RTX also increased the percentage of convergent neurons with large somatic field responses from 25% (15/60 neurons) to 39% (25/65). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig.5D).

Table 1.

Responses of bladder spinal neurons to somatic field stimulation in rats pretreated with intravesical RTX after acute and resolved experimental colitis.

| Groups | LT | WDR | HT | No response | Ratio (Responded/Tested) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute colitis | |||||

| Vehicle | 2 | 34 | 20 | 8 | 56/64 (87.5%) |

| Intravesical RTX | 5 | 33 | 29 | 6 | 67/73 (86.3%) |

| Resolved colitis | |||||

| Vehicle | 5 | 27 | 28 | 6 | 60/66 (90.9%) |

| Intravesical RTX | 2 | 30 | 33 | 9 | 65/74 (87.8%) |

LT – neurons with low threshold, WDR – wide dynamic range neurons and HT – neurons with high threshold to stimulation.

Fig. 5.

Intravesical RTX increases the number of urinary bladder spinal neurons with large somatic field input in rats with acute colonic inflammation. (A) Representative traces of low (top panel), wide dynamic (middle panel) and high (lower panel) threshold neurons responded to UBD and either innocuous (brush, Br) or noxious (pinch, Pi) stimulation of the somatic field. (B) Schematic presentation of the somatic field input from small (top) and large (bottom) area on the rat lower abdomen or hindquarter. (C) Number of bladder neurons responded to somatic stimulation in animals with intravesical instillation of a TRPV1 agonist during acute colitis. (D) Percentage of neurons responded to brush and pinch after resolved colonic inflammation.

3. Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of intravesical RTX on excitability and responsiveness of second-order spinal neurons with urinary bladder input upon development of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Analysis of electrophysiological characteristics of bladder neurons showed that intravesical RTX did not lead to the changes in ratio of responsive/non-responsive to UBD neurons in rats with acute colitis. In addition, neither RTX treatment nor duration of experimental colitis affected the location sites of UBD responsive neurons or their background activity. These observations provide evidence that TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder do not contribute to the responses of bladder spinal neurons to mechanical stimulation (UBD) during colon–bladder cross-talk, rather, they are involved in inflammation induced hyperexcitability of these neurons. Indeed, desensitization of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder prior to the onset of colonic inflammatory insult significantly reduced the duration and enhanced the latency period of excitatory responses in bladder neurons. Furthermore, intravesical RTX increased the number of high threshold excitatory neurons responded to UBD in rats with acute colitis.

TRPV1 receptors are predominantly expressed on afferent terminals coursing in the bladder wall and play a significant role in urinary bladder sensation and function. The bladder urothelium, however, appears to be a tissue which has a surprising number of conflicting reports associated with the expression of TRPV1 (Yu and Hill, 2011). Several previous studies identified urothelial expression of TRPV1 in rodents (Birder et al., 2001; Szallasi et al., 1993) and humans (Charrua et al., 2009; Lazzeri et al., 2004). Changes in the levels of urothelial TRPV1 were also observed in patients with transitional cell carcinoma (Lazzeri et al., 2005) and neurogenic overactive bladder (Apostolidis et al., 2005; Li et al., 2011). In contrast, other groups could not provide evidence for the presence of a PCR product, protein expression or functional TRPV1 channels in the urothelium (Everaerts et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2009; Yamada et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2011). In our study, we detected a significant decrease in TRPV1 protein in the urothelium after intravesical treatment with RTX which was previously shown by other groups and was linked to long lasting reduction in bladder pain and urgency (Apostolidis et al., 2005; Jeffry et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2003). Additionally, acute colonic inflammation alone significantly up-regulated the expression of TRPV1 in the distal colon with no effects on TRPV1 in the bladder as was recently reported by another group (Xia et al., 2012).

Differential effects of TRPV1 activation during mechanical (UBD) vs. inflammatory (colitis) visceral stimulation in our study were also observed by others but cannot be easily explained. On one side, TRPV1 null mice exhibited reduced responsiveness to bladder stretch under anesthesia, concomitant with a reduced stretch-evoked induction of c-fos expression in the spinal cord (Birder et al., 2001). Consistent with these findings, bladder and urothelial cells excised from TRPV1 null mice also showed reduced stretch- and hypotonic swelling-evoked ATP release, respectively (Birder et al., 2001). Additionally, intrathecal administration of RTX in rats reduced inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity without altering acute thermal sensitivity (Jeffry et al., 2009). On the other side, recombinant TRPV1 was not found to be activated by hypotonic swelling, and cutaneous mechanosensation was normal in TRPV1 null mice (Caterina et al., 2000). The variability in the reported data could be related to the co-assembly of TRPV1 with distinct TRPV subtypes (or other proteins) in the bladder and/or peripheral nerve terminals (Caterina et al., 2000). Alternatively, activation of TRPV1 on sensory neurons vs. urothelial afferents could potentially evoke distinct functional outcomes upon TRPV1 activation (Birder et al., 2002).

In our experiments, both RTX and UBD were applied directly to the urinary bladder while inflammation was induced at a different location – in the distal colon. The absence of dynamic changes in bladder neurons excited by graded UBD after intavesical RTX and significant reduction of neuronal excitability by RTX upon acute experimental colitis suggest that TRPV1 involvement in cross-organ sensitization is more pronounced when compared to mechanical stimulation of the urinary bladder. Our previous work described hyperexcitability of bladder responsive spinal neurons after acute colitis due to central sensitization as one of the mechanisms of pelvic organ cross-talk (Qin et al., 2005). Cross-sensitization between different organs is believed to develop as a result of initial pathological changes in one of the organs that sensitize neural fibers in the pelvis and subsequently lead to dysfunctions in neighboring organs (Malykhina, 2007; Pezzone et al., 2005). Cystometric evaluation of bladder function after TNBS inflammation was previously performed by three independent laboratories (Asfaw et al., 2011; Ustinova et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2012) and established that the severity of TNBS-induced colitis is the major factor underlying the development of colon/bladder cross-talk. The established criteria for direct evaluation of the severity of TNBS-induced colitis included assessment of disease activity index (DAI) (in vivo), histological confirmation of colonic damage (in vitro), and biochemical evaluation of MPO level (in vitro). These parameters were evaluated in our study and confirmed the presence of severe TNBS-colitis during acute phase, previously shown to cause the development of cross-sensitization between the colon and urinary bladder (Asfaw et al., 2011; Ustinova et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2012).

The suggested sequence of events in the development of cross-sensitization includes the following: 1—initial peripheral insult (inflammation, ischemia, trauma, infection etc.), 2—peripheral excitation/sensitization (afferent fibers and sensory neurons), 3—central sensitization (“amplification” in the spinal cord and brain), and 4—efferent input from the CNS to the pelvic viscera in response to activation of the afferent limb, which may either facilitate or inhibit nociceptive transmission (modified from (Brumovsky and Gebhart, 2010)). Several studies have shown that afferent input from the bladder and colon overlap onto the same primary sensory neurons (Christianson et al., 2007; Malykhina et al., 2006) as well as on the same second-order neurons within the spinal cord (Ness and Gebhart, 1988; Qin et al., 2005). Animal models of pelvic organ cross-sensitization revealed that acute cystitis lowers distal colonic sensory thresholds to colorectal distension in rats (Ustinova et al., 2006) and increases colorectal afferent sensitivity in mice (Brumovsky et al., 2009). Likewise, intracolonic application of TNBS leads to the development of a neurogenic bladder (Pezzone et al., 2005). The fact that urinary bladder denervation significantly abolishes the increased firing rate of bladder afferents induced by experimental colitis suggests that colonic inflammation modulates the sensitivity of afferent endings in the bladder by a neurogenic mechanism (Ustinova et al., 2006). Experiments with TNBS-induced colonic inflammation in mice also showed considerable urinary bladder hyperactivity demonstrated by more frequent micturition and substantial visceral and somatic hypersensitivity (Bielefeldt et al., 2006).

Our experiments on the effects of intravesical RTX on viscerosomatic spinal neurons revealed that pretreatment with RTX increased the number of bladder neurons receiving input from larger somatic field during acute colitis. This was an unexpected observation considering the fact that we did not use any stimulation of somatic field in vivo prior to electrophysiological recordings. It is well established that noxious stimulation of the viscera may trigger increased responses from referred somatic sites, which is generally attributed to viscerosomatic convergence at the level of the spinal cord (Cervero, 1983). In our previous study, large somatic fields were found more frequently for viscerosomatic spinal neurons in rats with inflamed colon compared with somatic fields mapped in control animals (Qin et al., 2005). Those neurons belonged to a subpopulation of wide-range dynamic neurons however, in the control group the majority of neurons were high threshold activated cells (Qin et al., 2005). In addition, other studies also demonstrated enhanced responses to the stimulation of the abdominal wall or hindpaw after acute irritation or inflammation of the colon, urinary bladder, ureter, or uterus (Bon et al., 2003; Jaggar et al., 2001; Wesselmann et al., 1998).

One of the explanations for the observation that RTX increased the number of bladder neurons with larger somatic input in the present study could be the involvement of TRPV1 in “nocigenic inhibition”. Nocigenic inhibition is the inhibition of neural, behavioral, or reflex responses to a nociceptive test stimulus produced by another, conditioning, nociceptive stimulus (Ness and Gebhart, 1991b; Ness and Gebhart, 1991a). In the early 1990s, Ness and Gebhart (1991a) examined whether a noxious visceral stimulus (i.e. colorectal distension) would inhibit neuronal or reflex responses to noxious cutaneous stimuli. Indeed, increased inhibition of responses to cutaneous nociception was produced by lengthening the duration of the noxious conditioning colorectal distension before the onset of noxious test skin heating. This nocigenic inhibition was sustained after the termination of colorectal distension and was evident in both intact and spinalized rats (Ness and Gebhart, 1991a). Experimentally induced cystitis also decreased thresholds to stimulation of the hindpaw. However, inflammation in the lower extremities causes enhanced responses to colorectal distension (somato-visceral sensitization) (Bielefeldt et al., 2006). It is possible, that in our experiments desensitization of bladder TRPV1 reduced excitability of bladder spinal and, possibly, dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons while simultaneously sensitized convergent neurons with overlying somatic fields. Additionally, viscerosomatic convergent neurons could belong to a different class of spinal neurons. It was previously reported that class 2 neurons (i.e. excited by both noxious and non-noxious cutaneous convergent neurons) were uniformly inhibited by noxious stimuli applied in cutaneous receptive fields whereas class 3 neurons (excited only by noxious stimuli) were not (Ness and Gebhart, 1991b).

The analysis of neuronal excitability and electrophysiological characteristics of bladder spinal neurons during resolved experimental colitis did not reveal any differences upon RTX application. The effects of RTX in our model of pelvic-organ cross-talk were noticeable only for the duration of acute inflammation. Previously published data suggest that intrathecal RTX administration in comparison to intravesical RTX may be more efficient in potentiating long-term analgesia when it comes to excitability of second order neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. A study by Jeffry et al. (2009) established that intrathecal RTX in rats caused a localized, selective ablation of TRPV1-expressing central sensory nerve terminals leading to longer lasting analgesia (Jeffry et al., 2009). These effects were observed in the absence of changes in the expression of TRPV1 in DRG neurons and on their peripheral terminals. Additionally, other experiments showed that RTX-induced loss of receptor binding affinity had partially recovered in the bladder after intravesical RTX but not in the spinal cord after intrathecal RTX administration suggesting that peripheral and central terminals of capsaicin-sensitive neurons have a differential sensitivity to vanilloids (Goso et al., 1993).

4. Conclusions

The results of our study provide evidence that desensitization of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder prior to the development of bladder/colon cross-sensitization reduces the effects of pelvic organ cross-talk on excitability of bladder projecting neurons but increases the responses from cells with convergent bladder/somatic input. Differential effects of intravesical RTX should be considered upon applications of vanilloids in chronic conditions associated with pelvic pain. Novel therapeutic approaches simultaneously targeting both peripheral and central cites of pain control may provide better clinical outcomes in patients with chronic pelvic pain.

5. Experimental procedures

5.1. Animals and experimental groups

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Malvern, PA, 250–300 g, 9–10 weeks of age) were used in this study. Rats were housed two per cage, with free access to food and water and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. All protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania and University of Oklahoma Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and adhered to the guidelines for experimental pain in animals published by the International Association for the Study of Pain. Animals were divided into two experimental groups: 1—control (vehicle instillation in the urinary bladder, N=20); 2—resiniferatoxin (RTX, TRPV1 agonist, 10−7 M, N=20) instillation in the urinary bladder. Due to technical difficulties with catheterization of the male bladder for RTX instillations, we performed a midline laparotomy under sterile conditions for intravesical administration of RTX. Rats were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed on a warming pad inside the designated hood to minimize the investigator’s exposure to the anesthetic. After a midline abdominal incision, the bladder was exposed with Q-tips, and urine was withdrawn via needle inserted into the bladder followed by instillation of 0.5 ml of RTX solution. The bladder was covered by gauze soaked in sterile saline and RTX was left in the bladder for 30 min. After this time, RTX was withdrawn and the urinary bladder was washed with sterile warm saline 3 times before it was placed back into the abdominal cavity. The control group of rats was instilled with vehicle (0.9% NaCl) for the same period of time. The wound was closed in layers and animals were allowed to recover from the surgery on a warm blanket.

To study the effects of desensitization of TRPV1 receptors upon the development of pelvic organ cross-sensitization, animals were treated with intracolonic 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS, 50 mg/kg) at day 3 post-RTX treatment to induce colonic inflammation. Rats were fasted for 24 h before the instillation procedure to provide better access to the colonic lumen. Animals were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane (VEDCO Inc., St. Joseph, MO), a 5–6 cm long polyethylene catheter attached to a 1 cc syringe was inserted into the rat colon for enema administration. After instillation procedure, an animal was held by the tail to avoid any spill of instilled liquid. The severity of developed colonic inflammation was assessed by disease activity index (DAI) in vivo followed by histological evaluation of the distal colon in vitro as previously described (Noronha et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2010). Briefly, the disease activity index (DAI) was calculated for each rat by determining the daily weight, presence of occult blood (detected with hemoccult strips, Smith Kline Diagnostics, San Jose, CA) or gross blood in feces, and stool consistency. Each of the parameters was assigned a score based on previously published criteria, which was used to calculate the average DAI for each animal. The scores ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 being no weight loss, normal stool consistency, and no rectal bleeding; 1—weight loss of less than 5%, stool consistency close to normal, occult blood-positive test in less than 25% of fecal pellets; 2—weight loss of 5–10%, soft stool, occult blood-positive test in 50% of fecal pellets; 3—10% to 15% of weight loss, mild diarrhea, occult blood-positive test in >50% of fecal pellets, and 4—weight loss exceeded 20% with severe diarrhea and gross bleeding. Only rats with DAI 3.0–3.5 during acute phase of colitis (3 days post-TNBS) were used for this study. Animals from experimental groups were sacrificed at 2 time points – at day 3 and day 30 post-TNBS treatment which correspond to the acute and resolved phases of TNBS-induced colonic inflammation, respectively.

5.2. Animal preparation for neuronal recordings

For electrophysiological experiments, animals in all experimental groups were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.). The left jugular vein was cannulated and an infusion of pentobarbital (15–25 mg/kg/h) was used to maintain anesthesia throughout the experiments. The right carotid artery was cannulated to monitor blood pressure. A tracheotomy was performed and a tube was inserted into the trachea for artificial ventilation with a volume-cycled respirator (55–60 strokes/min, 3.0–4.0 ml stroke volume). Paralysis was established by an injection of pancuronium bromide (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) and maintained with supplemental doses (0.2 mg/kg, i.p.). Body temperature was maintained between 36–38 °C using a thermostatically controlled heating blanket and overhead infrared lamps.

5.3. Distension protocols for the urinary bladder

Distensions were used to activate afferent fibers from the urinary bladder. After the urinary bladder was exposed with a midline abdominal incision, tubing (PE240, Clay Adams brand, purchased from Becton Dickinson) was placed into a small opening on the dome of the bladder and sutured in place. The urethra was ligated below the bladder neck. Urine was constantly evacuated via the open end of the tubing. The urinary bladder was distended manually at a rate of 0.2–0.4 ml/s. Release time of 1–3 s was required for the volume to return to zero. A series of isovolumic distensions of the urinary bladder (UBD, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 ml, 20 s) were produced. These volumes are used to grade the distension stimuli in the urinary bladder from the innocuous to noxious range as previously described. The search stimulus consisted of an injection of 1.0–1.5 ml to determine if spinal neurons received either high or low threshold inputs from the urinary bladder. Neuronal responses to UBD were repeated 2 or 3 times to characterize cells with urinary bladder input. At least 1 min elapsed between each distension volume.

5.4. Electrophysiological recordings from lumbosacral bladder neurons

A laminectomy exposed the lumbosacral spinal cord (L6–S2) for extracellular single-unit action potential recordings. After the rat was suspended with vertebral clamps, the dura mater of exposed spinal segments was removed. A small well was made with dental impression material and filled with agar (3–4% in saline) to improve recording stability and to protect the dorsal surface of the spinal cord from dehydration. Carbon-filament glass microelectrodes were used for single-unit recordings in an area from midline to 0–2 mm lateral to midline, and 0–1.2 mm in depth from the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. Recordings were made from neurons with spontaneous discharges having amplitudes that were large enough for analysis. Sometimes a burst of discharges that immediately disappeared could be recorded when the microelectrode was close to a neuron. This phenomenon made it possible to find and study responses of neurons without background activity. Every spinal neuron encountered during searching was examined for responses to somatic and visceral stimuli. Signals were displayed on an oscilloscope for continuous monitoring and also stored in a computer with Spike-2 software (Cambridge, UK) for off-line analysis. After the testing protocol for a spinal neuron with bladder input was completed, an electrolytic lesion (50 μA DC) was made at some recording sites. At the end of the experiment, the lumbosacral spinal cord was removed and placed in 10% buffered formalin solution. Frozen sections (55–60 μm) were viewed to find lesion sites in the gray matter of the spinal cord. Locations were drawn on cross sections traced from the cytoarchitectonic scheme of the spinal cord as previously described (Qin et al., 2005).

5.5. Testing of somatic receptive fields

Bladder spinal neurons identified by UBD were then tested for responses to innocuous somatic stimulation using a camelhair brush or a blunt probe, and to noxious pinch of the lower abdominal skin and/or muscle performed with blunt forceps. Neurons were categorized as follows: wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons responded to brushing the hair and skin and had greater responses to noxious pinching of the somatic field; high-threshold (HT) neurons responded only to noxious pinching of the somatic field; low-threshold (LT) neurons responded primarily to brushing. The sizes of somatic fields were measured and classified as small (long axis≤4 cm, unilateral hindquarter) and large (>4 cm, bilateral hindquarter). Outlines and descriptions of receptive fields were recorded manually for all neurons examined.

5.6. Histology

The urinary bladder and distal colon were isolated from all animals for histological evaluation of inflammatory changes in the distal colon and expression of TRPV1 receptors in the urinary bladder after RTX pre-treatment. Both organs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by paraffin embedding and processed for H&E staining. Small pieces of fresh tissue were snap frozen for MPO analysis using MPO ELISA kit (Alpco, Salem, NH, USA) as previously described (Lei and Malykhina, 2012). Images were captured and analyzed using Fluoview FV1000 software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

5.7. Western blotting

In order to determine whether intravesical RTX affected TRPV1 expression in the urothelium only or in the detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) as well, the urothelium was peeled off from the detrusor with fine forceps under the microscope. The urothelium, DSM, and distal colon were isolated and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 25% glycerol, 62.5 mM Tris–HCl, 1x protease inhibitors (Roche, complete mini) and phosphotase inhibitors (Roche, PhosSTOP). 10% SDS was added to the samples, vortexed and boiled for 4 min. The extracts were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and supernatants with the total protein were collected. Protein concentration in each sample was detected using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The amount of protein loaded per lane was 40 μg for all tissues. Proteins were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with ODYSSEY blocking buffer for 45 min at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, goat polyclonal anti-TRPV1 (VR1, Santa Cruz, sc-12498), at 1:200 and with mouse anti-α-tubulin (Santa Cruz, sc-5286) at 1:200 in the buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBS–T wash buffer (containing 0.1% Tween-20), membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies, ECL Plex goat-anti-mouse IgG-Cy3 (GE Healthcare, PA43009) at 1:2500 and donkey anti-goat Delight 649 conjugated (Rockland, #605-743-125) at 1:8000 for 1 h at room temperature. This step was necessary to stain the proteins with fluorescent dyes necessary for quantitative analysis and comparison on a multimode scanner Typhoon 8600 (Amersham Biotech., Sunnyvale, CA). Data were analyzed using Image-Quant software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

5.8. Chemicals and drugs

All chemicals and drugs were obtained from Sigma with the exception of isoflurane (VEDCO Inc., St. Joseph, MO) and TRPV1 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

5.9. Data analysis

To analyze neuronal responses, unit activity was stored and evaluated on rate histograms (1 s per bin). Spontaneous activity of neurons was determined as the average number of action potentials per second (imp/s) in the 10 s period prior to the onset of a stimulus. Based on this classification, neurons were divided into two groups: silent neurons with low spontaneous activity (<0.5 imp/s) and active neurons with high spontaneous activity (>0.5 imp/s). Spinal neurons receiving urinary bladder input demonstrated four patterns of responses to UBD classified as excitatory (E), inhibitory (I), excitatory–inhibitory (E–I), and inhibitory–excitatory (I–E). Excitatory or inhibitory responses to visceral stimuli (imp/s) were calculated by subtracting spontaneous activity from the mean of 10 s of the maximal activity during a stimulus. Based on the recovery time of neuronal activity to control levels following noxious UBD (1.5 ml), neurons were further subdivided into the following groups: neurons with recovery time ≤5 s were classified as short-lasting (SL) and neurons with recovery time >5 s were classified as long-lasting (LL). UBD-responsive neurons recorded at a depth of ≤300 μm from the dorsal surface of the spinal cord were classified as superficial neurons, whereas neurons below 300 μm (down to 1200 μm) were classified as deeper neurons. Latency of responses was measured as a delay in time from the beginning of UBD applied to the bladder to the time of the first action potentials recorded in UBD-responsive spinal neurons.

Data are presented as means±SE (N reflects the number of animals per group and n—number of neurons recorded in each group). Threshold volume of UBD for neuronal responses was calculated by extrapolation of least-squares regression line derived from the stimulus—response curve. Statistical significance of neuronal activity was assessed by two-way repeated measures (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the numbers of neurons in different categories. p≤0.05 was considered significant in all tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Doctors Jay Farber and Kennon Garrett for the expert discussion of the data, and Dr. Shaohua Chang and Antonio N. Villamor for excellent technical assistance. Preliminary results of this work were presented in an abstract form at the AUA 2010 meeting. This study was supported by the NIH/NIDDK Grants nos. DK077699 (A.P.M.) and DK 077699-S2 (A.P.M).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DAI

disease activity index

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- DSM

detrusor smooth muscle

- E

excitatory

- E–I

excitatory–inhibitory

- HT

high-threshold

- IC/BPS

interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

- I

inhibitory

- I–E

inhibitory–excitatory

- LL

long-lasting

- LL-E

long-lasting excitatory

- LT

low-threshold

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- RTX

resiniferatoxin

- SL

short-lasting

- SL-E

short-lasting excitatory

- TNBS

2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- UBD

urinary bladder distension

- WDR

wide dynamic range

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.003.

REFERENCES

- Apostolidis A, Brady CM, Yiangou Y, Davis J, Fowler CJ, Anand P. Capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in urothelium of neurogenic human bladders and effect of intravesical resiniferatoxin. Urology. 2005;65:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw TS, Hypolite J, Northington GM, Arya LA, Wein AJ, Malykhina AP. Acute colonic inflammation triggers detrusor instability via activation of TRPV1 receptors in a rat model of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Am. J. Physiol. 2011;300:R1392–R1400. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avelino A, Cruz F. TRPV1 (vanilloid receptor) in the urinary tract: expression, function and clinical applications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2006;373:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Lamb K, Gebhart GF. Convergence of sensory pathways in the development of somatic and visceral hypersensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;291:G658–G665. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00585.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA, Kanai AJ, de Groat WC, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Burke NE, Dineley KE, Watkins S, Reynolds IJ, Caterina MJ. Vanilloid receptor expression suggests a sensory role for urinary bladder epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13396–13401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231243698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA, Nakamura Y, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Barrick S, Kanai AJ, Wang E, Ruiz G, de Groat WC, Apodaca G, Watkins S, Caterina MJ. Altered urinary bladder function in mice lacking the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nn902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon K, Lichtensteiger CA, Wilson SG, Mogil JS. Characterization of cyclophosphamide cystitis, a model of visceral and referred pain, in the mouse: species and strain differences. J. Urol. 2003;170:1008–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000079766.49550.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky PR, Feng B, Xu L, McCarthy CJ, Gebhart GF. Cystitis increases colorectal afferent sensitivity in the mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 2009;297:G1250–G1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00329.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky PR, Gebhart GF. Visceral organ cross-sensitization – an integrated perspective. Auton. Neurosci. 2010;153:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F. Somatic and visceral inputs to the thoracic spinal cord of the cat: effects of noxious stimulation of the biliary system. J. Physiol. 1983;337:51–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Qin C, Zhang J, Foreman RD. Differential effects of urinary bladder distension on high cervical projection neurons in primates. Brain Res. 2002;949:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02969-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrua A, Reguenga C, Cordeiro JM, Correiade-Sa P, Paule C, Nagy I, Cruz F, Avelino A. Functional transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 is expressed in human urothelial cells. J. Urol. 2009;182:2944–2950. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TY, Corcos J, Camel M, Ponsot Y, Tu le M. Prospective, randomized, double-blind study of safety and tolerability of intravesical resiniferatoxin (RTX) in interstitial cystitis (IC) Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:293–297. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JA, Liang R, Ustinova EE, Davis BM, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA. Convergence of bladder and colon sensory innervation occurs at the primary afferent level. Pain. 2007;128:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGroat WC. Inhibition and excitation of sacral parasympathetic neurons by visceral and cutaneous stimuli in the cat. Brain Res. 1971;33:499–503. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaerts W, Vriens J, Owsianik G, Appendino G, Voets T, De RD, Nilius B. Functional characterization of transient receptor potential channels in mouse urothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 2010;298:F692–F701. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00599.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goso C, Piovacari G, Szallasi A. Resiniferatoxin-induced loss of vanilloid receptors is reversible in the urinary bladder but not in the spinal cord of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;162:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90594-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, Dmochowski RR, Erickson D, Fitzgerald MP, Forrest JB, Gordon B, Gray M, Mayer MM, Newman D, Nyberg L, Jr, Payne CK, Wesselmann U, Faraday MM. AUA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. J. Urol. 2011;185:2162–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Oh JM, Valtschanoff JG. Expression of the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons supports different roles of the receptor in visceral and cutaneous afferents. Brain Res. 2005;1047:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar SI, Scott HC, James IF, Rice AS. The capsaicin analogue SDZ249-665 attenuates the hyper-reflexia and referred hyperalgesia associated with inflammation of the rat urinary bladder. Pain. 2001;89:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffry JA, Yu SQ, Sikand P, Parihar A, Evans MS, Premkumar LS. Selective targeting of TRPV1 expressing sensory nerve terminals in the spinal cord for long lasting analgesia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Rivas DA, Shenot PJ, Green B, Kennelly M, Erickson JR, O’Leary M, Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for refractory detrusor hyperreflexia: a multicenter, blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:358–363. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb K, Zhong F, Gebhart GF, Bielefeldt K. Experimental colitis in mice and sensitization of converging visceral and somatic afferent pathways. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;290:G451–G457. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00353.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri M, Vannucchi MG, Spinelli M, Bizzoco E, Beneforti P, Turini D, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) expression changes from normal urothelium to transitional cell carcinoma of human bladder. Eur. Urol. 2005;48:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri M, Vannucchi MG, Zardo C, Spinelli M, Beneforti P, Turini D, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Immunohistochemical evidence of vanilloid receptor 1 in normal human urinary bladder. Eur. Urol. 2004;46:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Q, Malykhina AP. Colonic inflammation up-regulates voltage-gated sodium channels in bladder sensory neurons via activation of peripheral transient potential vanilloid 1 receptors. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012;24:575, e257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Sun Y, Simard JM, Chai TC. Increased transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) signaling in idiopathic overactive bladder urothelial cells. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:606–611. doi: 10.1002/nau.21045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malykhina AP. Neural mechanisms of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Neuroscience. 2007;149:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malykhina AP, Qin C, Greenwood-van MB, Foreman RD, Lupu F, Akbarali HI. Hyperexcitability of convergent colon and bladder dorsal root ganglion neurons after colonic inflammation: mechanism for pelvic organ cross-talk. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2006;18:936–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Characterization of neurons responsive to noxious colorectal distension in the T13-L2 spinal cord of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1988;60:1419–1438. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.4.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Interactions between visceral and cutaneous nociception in the rat. II. Noxious visceral stimuli inhibit cutaneous nociceptive neurons and reflexes. J. Neurophysiol. 1991a;66:29–39. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Interactions between visceral and cutaneous nociception in the rat. I. Noxious cutaneous stimuli inhibit visceral nociceptive neurons and reflexes. J. Neurophysiol. 1991b;66:20–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noronha R, Akbarali H, Malykhina A, Foreman RD, Greenwood-van MB. Changes in urinary bladder smooth muscle function in response to colonic inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. 2007;293:F1461–F1467. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XQ, Gonzalez JA, Chang S, Chacko S, Wein AJ, Malykhina AP. Experimental colitis triggers the release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in the urinary bladder via TRPV1 signaling pathways. Exp. Neurol. 2010;225:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne CK, Mosbaugh PG, Forrest JB, Evans RJ, Whitmore KE, Antoci JP, Perez-Marrero R, Jacoby K, Diokno AC, O’Reilly KJ, Griebling TL, Vasavada SP, Yu AS, Frumkin LR. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for the treatment of interstitial cystitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J. Urol. 2005;173:1590–1594. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154631.92150.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzone MA, Liang R, Fraser MO. A model of neural cross-talk and irritation in the pelvis: implications for the overlap of chronic pelvic pain disorders. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1953–1964. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Malykhina AP, Akbarali HI, Foreman RD. Cross-organ sensitization of lumbosacral spinal neurons receiving urinary bladder input in rats with inflamed colon. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1967–1978. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Conte B, Goso C, Blumberg PM, Manzini S. Characterization of a peripheral vanilloid (capsaicin) receptor in the urinary bladder of the rat. Life Sci. 1993;52:L221–L226. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustinova EE, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA. Colonic irritation in the rat sensitizes urinary bladder afferents to mechanical and chemical stimuli: an afferent origin of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;290:F1478–F1487. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00395.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesselmann U, Czakanski PP, Affaitati G, Giamberardino MA. Uterine inflammation as a noxious visceral stimulus: behavioral characterization in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;246:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GY, Gavva NR. Therapeutic potential of vanilloid receptor TRPV1 agonists and antagonists as analgesics: recent advances and setbacks. Brain Res. Rev. 2009;60:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia CM, Gulick MA, Yu SJ, Grider JR, Murthy KS, Kuem-merle JF, Akbarali HI, Qiao LY. Up-regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in primary afferent pathway regulates colon-to-bladder cross-sensitization in rat. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Gordon E, Lin Z, Lozinskaya IM, Chen Y, Thorneloe KS. Functional TRPV4 channels and an absence of capsaicinevoked currents in freshly-isolated, guinea-pig urothelial cells. Channels (Austin) 2009;3:156–160. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.3.8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Ishida Y, Kajita K, Shimada S. Differential localizations of the transient receptor potential channels TRPV4 and TRPV1 in the mouse urinary bladder. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009;57:277–287. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Hill WG. Defining protein expression in the urothelium: a problem of more than transitional interest. Am. J. Physiol. 2011;301:F932–F942. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00334.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Hill WG, Apodaca G, Zeidel ML. Expression and distribution of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in bladder epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. 2011;300:F49–F59. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00349.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.