Abstract

The development of imaging reagents is of considerable interest in the Alzheimer's disease (AD) field. Some of these, such as Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB), were designed to bind to the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), the major component of amyloid deposits in the AD brain. Although these agents were designed for imaging amyloid deposits in vivo, a major avenue of evaluation relies on postmortem cross validation with established indices of AD pathology. In this study, we evaluated changes in the postmortem binding of PiB and its relationship to other aspects of Aβ-related pathology in a series of AD cases and age-matched controls. We also examined cases of preclinical AD (PCAD) and amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), both considered early points in the AD continuum. PiB binding was found to increase with the progression of the disease, and paralleled increases in the less soluble forms of Aβ, including SDS-stable Aβ oligomers. Increased PiB binding and its relationship to Aβ was only significant in a brain region vulnerable to the development of AD pathology (the superior and middle temporal gyri) but not in an unaffected region (cerebellum). This implies that the amyloid deposited in disease affected regions may possess fundamental, brain region specific characteristics that may not as yet be fully appreciated. These data support the idea that PiB is a useful diagnostic tool for AD, particularly in the early stage of the disease, and also show that PiB could be a useful agent for the discovery of novel disease-related properties of amyloid.

Keywords: Mild Cognitive Impairment, Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease, Frontotemporal Dementia, Alzheimer's Disease, Amyloid-β Peptide, Amyloid-β Protein Precursor

Introduction

Late life neurologic disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) already consume a staggering amount of health care resources and this situation will worsen in the coming decades. Worldwide, the current number of individuals with AD is about 24 million, but could reach more than 80 million by the year 2040 [1]. AD is by far the best understood and most studied neurodegenerative disease. Although substantial advances have been made over the last decade, it is debatable how much closer we are to a clinically useful therapy. A long standing goal in the AD field has been to improve the accuracy of early detection, with the assumption that the ability to intervene earlier in the disease process will lead to a better clinical outcome. Major facets of this effort have been the continued development and improvement of AD biomarkers [2, 3], with a strong focus on developing imaging modalities [4].

Deposition of the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in the brain is a key factor in the diagnosis of AD, and is very likely critical to the development of the disease [5–7]. The Aβ found in human amyloid deposits is substantially modified, has variable N- and C-terminal ends, and exists in several states of varying solubility and aggregation [8–10]. It is now commonly accepted that soluble multimers of the Aβ peptide – often referred to as oligomeric Aβ – are the most toxic form of the peptide in the brain [11–14]. The relationships between the various soluble pools of Aβ, the precise identity of the toxic form(s) of Aβ, and the actual disease process are not understood and remain an intense area of investigation [10, 15].

A critical series of discoveries within the last decade has promoted the widespread use of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to identify amyloid pathology in vivo [16]. Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB, 2-[4'-(Methylamino)phenyl]-6-hydroxybenzothiazole; a derivative of the amyloid dye, thioflavin T [17]) is the most commonly used amyloid imaging agent. Increased 11C-PiB retention can be seen on PET scans in parts of the brain susceptible to Aβ deposition in AD [18]. There is a strong agreement between alterations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ levels and PiB retention in the brain [19], and a substantial effort is underway to determine the utility of PiB as a diagnostic and predictive tool for AD [20]. To date, studies on subjects that have come to autopsy after being recently imaged using PiB have been limited to relatively small numbers of cases. There is a general agreement between PiB retention and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease (CERAD) plaque score, and plaque numbers, in autopsy cases [21, 22], indicating that PiB retention is at least somewhat proportional to amyloid load.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, proceeding through several stages. Although the exact staging of the disease is still debated, there is almost certainly a preclinical or prodromal phase of the disease where some AD pathology is present in the absence of readily apparent clinical impairment (PCAD; [23]). After this stage, patients will pass through a state of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [24, 25] before progressing to early stage AD, defined by the presence of specific clinical features, including functional memory impairment. About 1/5th of otherwise cognitively normal elderly show PiB retention in one or more neocortical regions [26], and this is associated with a risk of later cognitive decline, indicating the presence of a possible stage of preclinical AD [27, 28]. Some of these cases can eventually be classified as amnestic MCI [29]. About 3/5th of MCI patients show elevated PiB binding in some part of the neocortex [27, 30], and higher levels of PiB binding are associated with faster rates of cognitive decline, increased incidence of conversion to AD, and a greater degree of cerebral atrophy [31, 32].

Mapping the quantitative relationship between the PiB retention signal on PET imaging and the amyloid pathology in the brain is an active area of research [21, 33–35]. Although we have made some advances in our understanding of what PiB retention means for late stage AD cases, there is considerably less information for the earlier stages of the disease process. This can be largely attributed to the relatively small number of these cases that come to autopsy, even in a large multicenter trial. One way to address this issue is by performing a cross sectional study on autopsy cases derived from different stages of the disease, and examining the relationship between postmortem PiB binding and neuropathology [33, 36]. Although there have been a small number of studies examining late stage AD cases (and MCI [37]) in this manner, to our knowledge there are no studies examining the relationship between PiB binding and neuropathology in PCAD, MCI, AD, and well-defined, cognitively normal control cases. In the present study, we analyzed postmortem PiB binding in two brain regions throughout this continuum of AD, and compared the results to other measures of Aβ neuropathology.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Neuropathological Assessment

The samples used in this study were provided by the tissue repository of the Alzheimer's Disease Center at the University of Kentucky [15, 38, 39]. Some details of this case series, and their disease related enzymology, were recently reported [40]; salient characteristics will be briefly summarized here (mean ± s.d.). Postmortem interval was short (3.1 ± 1.0 hours) for the entire series. Controls (n = 9, 5M / 4F; age, 84.3 ± 5.1 years) had no history of ante-mortem cognitive impairment (MMSE: 28.4 ± 1.5; last MMSE: 0.7 ± 0.4 years); AD cases (n = 10, 4M / 6F; age, 83.4 ± 5.7 years) showed substantial cognitive impairment (MMSE, 9.9 ± 6.0; last MMSE: 2.4 ± 2.3 years). Prodromal or preclinical AD (PCAD) cases (n = 10, 1M / 9F; age, 85.6 ± 3.7 years) were defined as those that met the NIA-Reagan neuropathology criteria for likely AD, but exhibited no clinical signs of dementia (MMSE, 29.4 ± 0.7; last MMSE: 0.8 ± 0.5 years)[5, 23]. Amnestic MCI cases (n = 7, 3M / 4F; age, 89.0 ± 5.8 years) were defined as per Petersen et. al. [41]; MMSE scores (24.8 ± 3.1; last MMSE: 0.6 ± 0.3 years) were significantly lower (p < 0.04) in this group compared to the control group. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) cases (n = 6, 3M / 3F; age, 61.0 ± 14.6 years) were included as an additional neurodegenerative disease and served as a specificity control [42]. FTD, which typically occurs at a younger age than AD, results in a significant cognitive impairment (MMSE, 7.8 ± 9.0; p < 0.001; last MMSE: 4.6 ± 3.1 years) but does not typically show the same pattern of neuropathology as AD. Aβ deposition is not a feature of FTD [42]. FTD cases had either tau inclusions (n = 2), ubiquitin inclusions (n = 1), motor neuron degeneration in the absence of tau inclusions (n = 1), or no distinct histopathological lesions (n = 2). The details of the recruitment, inclusion criteria, and neuropsychological test battery have been described [43].

Brain weights were determined and a gross neuropathological evaluation carried out at the time of autopsy. We used one disease-affected brain region (the superior and middle temporal gyri, SMTG) and one unaffected region (the cerebellum). Tissue samples were dissected and frozen or formalin fixed. For histology, paraffin-embedded specimens were cut (8 μm) and stained with standard hematoxylin-eosin, modified Bielschowsky method, or Gallyas silver method. Braak staging [44] used both Gallyas and Bielschowsky-stained sections. Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), diffuse plaques (DPs; plaques without surrounding dystrophic, argyrophilic neurites), and neuritic plaques (NPs; plaques surrounded by dystrophic, argyrophilic neurites) were counted and averaged as described [15, 39, 45]. There was no cause of death pattern in any disease group. Human tissue collection and handling followed PHS guidelines established by the University of Kentucky IRB.

Biochemical Analyses

The amount of Aβ in tissue samples was determined using a three-step serial extraction procedure, followed by the quantitative measurement of Aβ by ELISA. This approach takes advantage of increasingly more denaturing conditions to extract Aβ that is progressively more insoluble. Details of the methodology and antibodies used are available elsewhere [9, 40, 46–49]. Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in standard PBS buffer (pH = 7.4, 1.0 ml/200 mg of tissue, with complete protease inhibitor cocktail, PIC; Amresco; Solon, OH) using an AHS200 PowerMax homogenizer. The supernatant was collected following centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was serially re-extracted by brief sonication in 2% SDS (w/v, with PIC) followed by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 30 mins at 14°C, and the supernatant collected. This pellet was then re-extracted by sonication in 70% formic acid (FA; v/v) centrifuged at 20,800 × g for 1 hour at 4°C, and the supernatant collected. Sample extracts were stored frozen at − 80°C until time of assay. Prior to ELISA, FA-extracted material was neutralized in TP buffer (1.0 M Tris-base, 0.5 M Na2HPO4), before further dilution in antigen capture (AC) buffer [0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 7), 0.4 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.4% Block Ace (Serotec; Raleigh, NC), 0.2% BSA, 0.05% CHAPS, and 0.05% NaN3]. PBS and SDS extracts were also diluted in AC buffer for ELISA [50]. Standard curves of synthetic peptides were prepared in AC buffer, and all standards and samples were run at least in triplicate. Capture was conducted using antibody Ab9 (human sequence Aβ1–16); Aβ40 was detected with biotinylated-Ab13.1.1 (end-specific for human Aβ40) and Aβ42 was detected with biotinylated-12F4 (end-specific for human Aβ42; Covance; Princeton, NJ). 384-well plates (Immulon 4HBX; Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA) were coated with 0.5 μg / well of antibody, and blocked with SynBlock (AbD Serotec; Raleigh, NC, as per the manufacturer's instructions). The total amount of Aβ was determined by summing the amounts of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in each fraction. Single-site assays for SDS-soluble, oligomeric Aβ were performed in a similar manner, except using antibody 4G8 (against Aβ17–24; Covance) for capture and biotinylated-4G8 for detection. Signals were compared against synthetic oligomeric Aβ [46, 49, 51]. After incubation with detection antibody, plates were incubated with 0.1 μg / ml of neutravidin-HRP (Pierce Biotechnologies; Rockford, IL) for 1–2 hours. Following development with 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine reagent (TMB; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories; Gaithersburg, MD), the reaction was stopped with 6% o-phosphoric acid and optical density determined at 450 nm using a BioTek multiwell plate reader.

3H-PiB binding to brain homogenates was carried out similar to the filtration assay of Klunk et al. [33], as per Rosen et al. [52]. Briefly, unfractionated PBS homogenate was diluted into a 96-well polypropylene plate in triplicate. Two hundred μl of 1nM 3H-PiB (custom synthesized by ViTrax Radiochemicals, Placentia, CA; a kind gift of Dr. Brian Ciliax, Emory University) was added to each of the first two wells, and 1 μM of an unlabeled competitor (BTA-1) was added to the third well to determine nonspecific binding (by subtraction). Femtomoles of 3H-PIB bound were calculated per wet weight of tissue after correcting for counting efficiency.

For the examination of Aβ and AβPP by Western blot, 10 μL of the FA fractions were dried under vacuum (Labconco Centrifugal Concentrator; Labconco; Kansas City, MO), then reconstituted in standard loading buffer. These samples, as well as 10 μl of the PBS and SDS extracts, were separated on 12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE with MES XT running buffer (BioRad; Hercules, CA). The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose. After transfer, the membranes were boiled in PBS for 5 minutes and blocked overnight in 1% BSA and 2% BlockAce (Serotec) in PBS. The membranes were probed with antibody 6E10 (against Aβ1–16; Covance; 2 μg/mL in PBS with 5% nonfat dry milk), followed by rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc.; Gilbertsville, PA). AβPP was detected using AbCT20, as described [40]. For AβPP SDS-PAGE, 25 μg of total protein from the SDS fraction was loaded per lane, and the gels were transferred to PVDF membranes instead of nitrocellulose. Reactive bands were visualized with Super Signal West Dura HRP Substrate (Pierce) and exposed to film overnight.

Statistical Analyses

We have used a similar systematic approach for the analysis of neuropathology and RNA oxidation across multiple brain regions in a group of AD cases [49]. Data were analyzed using SPSS®. Multivariate analyses (MANCOVA) were adjusted for age, postmortem interval, and gender. Post-hoc group comparisons were made using either Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons to a control group, or using Tukey's LSD method. Some between regional comparisons were performed using paired t-tests. The type I error rate for multiple comparisons between either correlations or paired t-tests was adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni Method [53].

Results

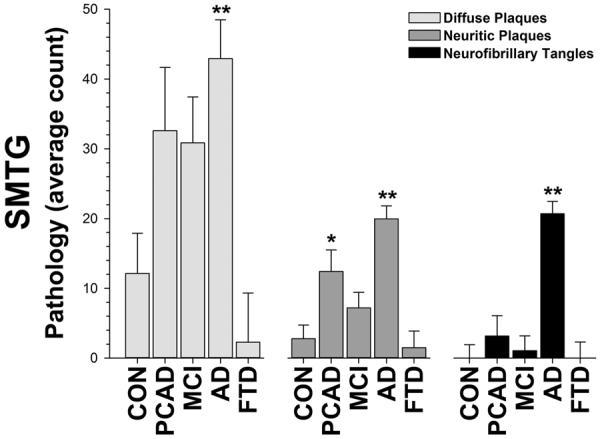

As expected, disease cases showed a substantial increase in pathology in the temporal neocortex (F[12,96] = 4.34, p<0.001; Figure 1). Diffuse plaques (F[4,32] = 6.83, p<0.001), neuritic plaques (F[4,32] = 13.93, p<0.001), and neurofibrillary tangles (F[4,32] = 22.71, p<0.001) all increased with disease state. MCI and PCAD cases were generally similar. These forms of neuropathology were not features of the FTD cases included this study. Although plaques and tangles were not commonly found in these FTD cases, substantial neurodegeneration and atrophy were present. For example, the overall brain weight of the FTD cases was significantly less than the control (p < 0.002), MCI (p < 0.04) and PCAD cases (p < 0.001), and trended lower (p < 0.06) when compared to the AD cases (Tukey's LSD; data not shown). We also evaluated indices of vascular pathology, including infarcts (as described in [54]) and congophilic angiopathy (CAA, as described in [55]). There were no differences between the total number of hemorrhagic, pale, lacunar, or micro infarcts in either the SMTG or cerebellum in this cohort, and arteriosclerosis was unremarkable. There were no significant group differences in the amounts of either parenchymal or meningeal CAA.

Figure 1. Standard Indices of Neuropathology.

Plaques (diffuse and neuritic) and neurofibrillary tangles are significantly elevated in the brains of AD patients and, to a lesser degree, in cases of PCAD and MCI. The neuropathological burden based on these measures was similar between PCAD and MCI, and FTD cases were similar to control cases. Dunnett's test, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

We first evaluated the amount of Aβ and AβPP by immunoblot (Figure 2). The full length AβPP levels did not change noticeably between disease and nondisease groups (however, we have previously reported a modest relationship between CTFβ and β-secretase activity in these cases [40]). There were several notable differences between the appearance of the Aβ peptide in the different soluble fractions. First, there was substantially less Aβ in the cerebellum as compared to the SMTG in both the PBS and SDS fractions. In contrast, there was a strong, positive Aβ signature in the FA fraction in the cerebellum in the AD cases that was comparable to that of the SMTG. Second, there was only a faint monomeric Aβ band detectable in the PBS fraction from the SMTG, whereas there were multiple higher molecular weight bands in the SDS fraction, and a wide range of dissociated immunopositive fragments in the FA fraction. These most likely correspond to both oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ species, and were clearly elevated in the AD cases. Within the SDS fraction, there were multiple distinct bands of oligomeric Aβ species that could also be seen in the MCI and PCAD cases. We did not detect a distinct overabundance of any single prominent band, such as Aβ*56 [56], although there were certainly bands within this size range. There was little, if any, Aβ detected in either the control or FTD cases. In general, these data were in broad agreement with the immunoassay data (described below).

Figure 2. Aβ and AβPP in a Disease-Affected (SMTG) and Unaffected (Cerebellum) Region.

(A) The Aβ peptide can be detected at various levels on immunoblot. A synthetic Aβ42 standard was run on the first lane of each gel; full length AβPP can be seen in both the PBS and SDS fractions, between the 188 and 62 kDa markers. Although there is some minor variation in full length AβPP, there are no consistent differences (see below). A faint band corresponding to monomeric Aβ can be seen in a few cases in the SMTG, but not in the cerebellum. A substantially stronger signal – especially for monomeric Aβ – can be seen in the SDS fraction, along with a variety of higher molecular weight, oligomeric forms of the peptide. SDS-soluble Aβ can be seen in the AD, MCI, and PCAD cases, and is mostly absent from the control and FTD cases. As with the PBS fraction, very little SDS-soluble Aβ can be detected in the cerebellum (this is a sensitivity issue, as more Aβ can be measured in the SDS fraction in the AD cases by ELISA; c.f., Figure 3). There was a large amount of FA-soluble Aβ in both the SMTG and cerebellum in AD cases; a large portion of this signal appears as a smear, representing a wide range of Aβ species that have been dissociated from relatively insoluble fibrillar material. (B) The expression of full length AβPP is not remarkably different between control and disease cases. Lysate from H4 cells overexpressing human AβPP695ΔNL was run as a marker in the first lane. All immunoblots were probed and developed for the same amount of time, and βActin levels did not vary noticeably between samples (Supplementary Figure 1).

We next collected quantitative measurements of Aβ by ELISA from both brain regions (Figure 3). The total amount of Aβ found in the disease cases was increased in both the SMTG (SDS: F[4,32] = 63.01, p<0.0001; FA: F[4,32] = 7.00, p<0.001) and cerebellum (SDS: F[4,31] = 11.49, p<0.001; FA: F[4,31] = 4.5, p<0.006). There were no disease-related differences between the amounts of aqueous (PBS) soluble Aβ in either region (SMTG: F[4,32] = 1.39, n.s.; cerebellum: F[4,31] = 2.07, n.s.). The disease-related increase in the SMTG relative to the cerebellum was larger in the SDS fraction (F[4,29] = 32.37, p<0.0001) but not in the FA fraction (F[4,29] = 0.97, n.s.). The largest values were from the AD cases, with smaller increases observed in the PCAD and MCI cases. The PCAD and MCI groups were not significantly different from each other. There was ~8 times more SDS-soluble Aβ in the SMTG compared to the cerebellum in the AD group as compared to the controls (t[9] = 6.77, p<0.01), whereas there was no difference between the amounts of FA-soluble Aβ in the same cases (t[9] = −0.63, n.s.). Effects were similar for both Aβ40 and Aβ42 (Supplementary Table 1). There was significantly more oligomeric Aβ in the SMTG (F[4,32] = 5.00, p<0.003), but not in the cerebellum (F[4,31] = 1.15, n.s.), in disease. When compared to the cerebellum, oligomeric Aβ was higher in the SMTG in the AD (t[9] = 7.09, p<0.01), PCAD (t[9] = 3.32, p<0.04), and MCI (t[5] = 4.03, p<0.03) cases. PiB binding was similarly elevated in the SMTG (F[4,32] = 7.08, p<0.001). PiB binding was minimal in the cerebellum, and did not show a strong disease-related increase (F[4,31] = 2.2, p<0.1) in this region. There were no significant differences between the FTD cases and controls.

Figure 3. Soluble Aβ, Oligomeric Aβ, and Fibrillar Aβ.

Sandwich ELISA (soluble Aβ): The total amount of Aβ was increased in AD in both the SMTG and cerebellum in the SDS and FA fractions; PBS-soluble Aβ was not elevated in disease. Increases in PCAD and MCI cases were modest relative to controls, and were most apparent in the FA fraction isolated from the SMTG. FTD cases were essentially indistinguishable from control cases. Data shown are corrected for age and PMI. Similar results were obtained in separate evaluations of Aβ40 and Aβ42 (c.f. Supplementary Table 1). Single-Site ELISA (oligomeric Aβ): Oligomeric Aβ was only significantly higher in the SMTG and not within the cerebellum. Values for PCAD and MCI cases were intermediate between control and AD cases; FTD cases were slightly lower than controls, although this was not a significant difference. PiB Binding (fibrillar Aβ): Fibrillar Aβ, as defined by PiB binding, was significantly higher in the SMTG than in the cerebellum. Values for PCAD and MCI cases were intermediate between control and AD cases; FTD cases were not significantly different from control cases and, similar to oligomeric Aβ, were slightly lower. Dunnett's test, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

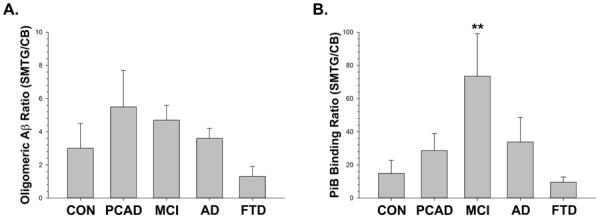

Although we could detect clear differences in postmortem PiB binding between the SMTG and cerebellum, they were significant in the AD group (t[9] = 6.61, p<0.01), but only marginally significant for the PCAD (t[9] = 2.60, unadjusted p<0.03) and MCI (t[5] = 2.84, unadjusted p<0.04) groups. For amyloid imaging in vivo, values for cortical PiB retention are typically standardized to values obtained from the cerebellum in the same patient [16]. We therefore performed a similar comparison in our case series, by standardizing the SMTG value to the cerebellum from the same case (Figure 4). Since the oligomeric Aβ measures exhibited a pattern comparable to PiB binding, we did the same analysis in these cases. There were no differences between disease states when the amount of oligomeric Aβ in the SMTG was standardized in this manner (F[4,31] = 0.86, n.s.). The postmortem PiB binding ratio was significantly different in disease when the SMTG values were corrected to the cerebellum (F[4,31] = 5.70, p<0.001). When the data were analyzed in this way, the MCI group was notably higher than the other groups, an effect attributable to the very low levels of cerebellar PiB binding in this subgroup.

Figure 4. Correcting PiB Binding Values to the Cerebellum Distinguishes MCI Cases.

(A) There were no differences between disease states when the amount of oligomeric Aβ in the SMTG was standardized to the amount found in the cerebellum. (B) There was a significant difference detected for disease when PiB binding in the SMTG was corrected to the amount in the cerebellum. Interestingly, the most prominent effect of this standardization was to amplify the difference between the MCI cases as compared to the other groups. Dunnett's test, ** = p < 0.01.

Finally, we wanted to determine how PiB binding related to other aspects of Aβ pathology in this case series (Figure 5). Postmortem PiB binding was strongly correlated with the total plaque number (R2 = 0.51, p<0.0001; not shown). Whereas plaque counts are a reasonable means to determine disease status, it is likely that Aβ positive area is a stronger correlate of PiB binding [21]. Oligomeric Aβ was only correlated with SDS soluble Aβ42 (R2 = 0.16, p<0.01; not shown). PiB binding was significantly correlated with both SDS- (p<0.001) and FA- (p<0.05) soluble Aβ, but not with PBS-soluble Aβ (p<0.12). These forms of the peptide are less soluble by definition (they require either a harsh detergent or acid to solubilize), and also show the most consistent increases with disease. In both cases, the strongest correlation was with Aβ42 (SDS: R2 = 0.46, p<0.001; FA: R2 = 0.21, p<0.002). PiB binding was also significantly correlated with the amount of oligomeric Aβ (R2 = 0.22, p<0.01). PiB binding was not significantly correlated with any of these forms of Aβ (including either Aβ40 or Aβ42) in the cerebellum (oligomeric Aβ, p<0.3; PBS-soluble Aβ, p<0.4; SDS-soluble Aβ, p<0.15; FA-soluble Aβ, p<0.1; data not shown). This was somewhat surprising, as at least two of these forms of Aβ (SDS- and FA-soluble) did show significant changes in the cerebellum with disease, and were higher in the AD cases (Figure 3; c.f. Supplementary Table 1). We did not detect a relationship (p<0.5) between any aspect of cerebrovascular pathology (including CAA score) and post-mortem PiB binding in this case series.

Figure 5. PiB Binding Correlates with Less Soluble Forms of Aβ in the SMTG.

(A) The amount of postmortem PiB binding was significantly correlated with oligomeric Aβ (p<0.01). (B) PiB binding was not correlated with Aβ extractable in PBS, the most soluble form of the peptide. However, PiB binding was significantly correlated with Aβ extractable in either SDS (C; p<0.001) or FA (D; p<0.05). These correlations were not found in the cerebellum, and there was no detectable relationship between CAA and PiB binding in this case series (not shown).

Discussion

Although it is often said that the cerebellum is spared in AD, this is not completely correct. The cerebellum does not display NPs or NFTs, but does contain substantial deposits of diffuse amyloid [57]. The Aβ peptide was readily detectable in the cerebellum, albeit at lower levels than in a disease-affected neocortical region (the SMTG). For instance, in the AD cases there was far more SDS-soluble Aβ in the SMTG as compared to the cerebellum. On immunoblots, SDS-stable oligomeric Aβ was also visible (Figure 2), and was observed to increase with disease progression on immunoassay (Figure 3). However, the FA-soluble Aβ appeared remarkably similar on immunoblots – and the amount determined by immunoassay was essentially identical – in the two brain regions. This suggests that the Aβ extracted from the cerebellum mostly originated from the diffuse Aβ deposits, but that these were nonetheless largely composed of relatively insoluble Aβ. It is unclear why NPs are not found in the cerebellum, since the amount of aggregated Aβ peptide is comparable to that found in the SMTG. It is likely that the cerebellum possesses physiological properties that protect against NP formation. The highly insoluble Aβ17–42 species [58], abundant in the cerebellum, may be related to this observation. However, the presence of Aβ17–42 cannot fully account for our data, as our sandwich ELISA and immunoblots are based on capture or detection using antibodies raised against Aβ1–16. The enzyme neprilysin, a major factor in the removal of Aβ from the brain [59], is inversely related to the number of NPs and Aβ in the neocortex [40, 60]. Neprilysin expression and activity are higher in the cerebellum in AD cases [40, 61]. One possibility could be that higher neprilysin activity is related to the lack of NPs in the cerebellum, without affecting the amount of Aβ in diffuse deposits, although the mechanism for this is not clear.

We found significant quantities of higher order Aβ multimers (oligomeric Aβ) in the neocortex that increased with disease progression, and these were considerably less abundant in the cerebellum. Similarly, PiB binding, thought to mostly reflect Aβ in a fibrillar state, was increased in the SMTG but not in the cerebellum. However, in later stage AD, the amount of aggregated Aβ was similar between the SMTG and cerebellum. This implies that at least some higher order Aβ structures do not form solely in a concentration-dependent manner, and that other processes must be involved. Differences between the amounts of oligomeric Aβ in the neocortex and the cerebellum are well known [62, 63], and the role of these species in AD neuropathology has been explored in some detail in recent years [64, 65]. It has also been suggested that the most toxic form of the Aβ peptide is a dimeric form [12], although it is likely that other species contribute to the pathology given the broad population that can be detected on immunoblot. Interestingly, we found correlations between PiB binding and oligomeric, SDS- and FA-soluble Aβ in the SMTG but not in the cerebellum. This further indicates that the Aβ deposited in the cerebellum is different from the Aβ deposited in the neocortex in some fundamental way, and that the diffuse amyloid deposits in the cerebellum are not strongly related to PiB binding. There are both high (nM) and low (μM) affinity PiB binding sites on synthetic and biological Aβ fibrils [33]. The low affinity site is more abundant in synthetic fibrils, fibrillar Aβ from transgenic mice, and the Aβ found in the brains of aged non-human primates [52, 66]. A large proportion of the PiB binding under our assay conditions (1 nM 3H-PiB) is to the high affinity site [33]. It is possible that these differences between the SMTG and cerebellum reflect an underlying difference in the disease process that could be useful in elucidating unknown, or at least unappreciated, aspects of AD. At a minimum, a comparison between the cerebellum and a neocortical region such as the SMTG might be ideal for determining the molecular identity of the high density, high affinity PiB binding site in the AD brain. The identification and mapping of this site could represent an important step towards the development of new imaging agents.

Autopsy studies of patients subject to PiB neuroimaging are still relatively uncommon [21, 33–36], and there has been relatively little examination of earlier stage cases of disease of the type reported here. The longitudinal study of these individuals, and the integration of PiB neuroimaging data with established pathologies and other potential biomarkers, will be critical for developing a reliable clinical protocol for AD diagnosis and monitoring [20]. It is intriguing that our data show that PiB may have some benefit in distinguishing MCI cases from not only normal elderly controls, but possibly from preclinical AD cases as well. We emphasize that this is a study in a relatively small number of cases, and demonstrating the true utility of PiB binding as an agent for identifying MCI will require a much larger cohort. These findings are particularly important given the latest recommendations from the National Institute of Aging (NIA) /Alzheimer's Association which focus on the use of imaging and CSF measures to define MCI [67]. These recommendations emphasize the use of subjects from longitudinal studies and incorporation of CSF and/or imaging studies to define MCI as being caused by AD pathology. Similarly, both imaging and CSF play a larger role in the defining of AD in the latest NIA guidelines [68]. Data from the present study contribute to both of these efforts by demonstrating the utility of imaging probes for both clinical imaging as well as ex vivo analysis in the laboratory setting to understand the pathological processes involved in AD. This has the potential to not only advance our understanding of the disease at the molecular level, but could also lead to better imaging reagents in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AG005119 (M.P.M, J.N.K., H.L., M.S.M.), AG029885 (J.N.K), AG025771 (J.N.K), NS058382 (M.P.M.), HL086341 (R.L.W.), the CART foundation (M.P.M., D.M.N., H.L.), and the Hibernia National Bank/Edward G. Schlieder Chair (J.N.K.). We thank the staff of the UK Alzheimer's Disease Core Center (AG028383) and the patients and families that participated in our program. Thanks to Ela Patel and Dr. Huaichen Liu for providing the histopathology data. Special thanks to the late Dr. William R. Markesbery, who was a major contributor to the design and implementation of this study, and the expert editing assistance of Paula Thomason.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- [1].Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Trojanowski JQ, Vandeerstichele H, Korecka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter WZ, Weiner MW, Jack CR, Jr., Jagust W, Toga AW, Lee VM, Shaw LM. Update on the biomarker core of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative subjects. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2010;6:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR, Jr., Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klunk WE. Amyloid imaging as a biomarker for cerebral beta-amyloidosis and risk prediction for Alzheimer dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32(Suppl 1):S20–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].NIA Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer's disease: a critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Atwood CS, Martins RN, Smith MA, Perry G. Senile plaque composition and posttranslational modification of amyloid-beta peptide and associated proteins. Peptides. 2002;23:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Murphy MP, Beckett TL, Ding Q, Patel E, Markesbery WR, St Clair DK, LeVine H, 3rd, Keller JN. Abeta solubility and deposition during AD progression and in APPxPS-1 knock-in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Murphy MP, LeVine H., 3rd Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:311–323. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, Liu H, Davis DG, Mendiondo MS, Abner EL, Markesbery WR. Clinicopathologic correlations in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort: neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1136–1146. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c5efb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sojkova J, Resnick SM. In vivo human amyloid imaging. Current Alzheimer research. 2011;8:366–372. doi: 10.2174/156720511795745375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Y, Klunk WE, Debnath ML, Huang GF, Holt DP, Shao L, Mathis CA. Development of a PET/SPECT agent for amyloid imaging in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;24:55–62. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:1:055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergstrom M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausen B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Langstrom B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Price JC, Mathis CA. Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009;73:1193–1199. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Apostolova LG, Hwang KS, Andrawis JP, Green AE, Babakchanian S, Morra JH, Cummings JL, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jack CR, Jr., Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. 3D PIB and CSF biomarker associations with hippocampal atrophy in ADNI subjects. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1284–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko S, Bi W, Paljug WR, Debnath ML, Hope CE, Isanski BA, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST. Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131:1630–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sojkova J, Driscoll I, Iacono D, Zhou Y, Codispoti KE, Kraut MA, Ferrucci L, Pletnikova O, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, O'Brien RJ, Wong DF, Troncoso JC, Resnick SM. In vivo fibrillar beta-amyloid detected using [11C]PiB positron emission tomography and neuropathologic assessment in older adults. Archives of neurology. 2011;68:232–240. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr., Buckles VD, Roe CM, Xiong C, Grundman M, Hansen LA, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Smith CD, Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR, Kaye J, Kurlan R, Hulette C, Kurland BF, Higdon R, Kukull W, Morris JC. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, Ritchie K, Rossor M, Thal L, Winblad B. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Ziolko SK, James JA, Snitz BE, Houck PR, Bi W, Cohen AD, Lopresti BJ, DeKosky ST, Halligan EM, Klunk WE. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Archives of neurology. 2008;65:1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Ng S, Moss SA, Maruff P, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2007;130:2837–2844. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2009;66:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Darby D, Maruff P, Savage G, Ng S, Ackermann U, Cowie TF, Currie J, Chan SG, Jones G, Tochon-Danguy H, O'Keefe G, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Abeta deposits in older non-demented individuals with cognitive decline are indicative of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1688–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Wilson IA, Nagren K, Helin S, Bruck A, Oikonen V, Kailajarvi M, Scheinin M, Viitanen M, Parkkola R, Rinne JO. PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:1603–1606. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260969.94695.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ewers M, Insel P, Jagust WJ, Shaw L, Trojanowski JJ, Aisen P, Petersen RC, Schuff N, Weiner MW. CSF Biomarker and PIB-PET-Derived Beta-Amyloid Signature Predicts Metabolic, Gray Matter, and Cognitive Changes in Nondemented Subjects. Cerebral cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Koivunen J, Scheinin N, Virta JR, Aalto S, Vahlberg T, Nagren K, Helin S, Parkkola R, Viitanen M, Rinne JO. Amyloid PET imaging in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a 2-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2011;76:1085–1090. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318212015e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Ikonomovic MD, Lefterov IM, Koldamova RP, Abrahamson EE, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Huang GF, Shao L, DeKosky ST, Price JC, Mathis CA. Binding of the positron emission tomography tracer Pittsburgh compound-B reflects the amount of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease brain but not in transgenic mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10598–10606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2990-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Freeman SH, Raymond SB, Augustinack JC, Johnson KA, Irizarry MC, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Dekosky ST, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, Growdon JH. Molecular imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B confirmed at autopsy: a case report. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:431–434. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Leinonen V, Alafuzoff I, Aalto S, Suotunen T, Savolainen S, Nagren K, Tapiola T, Pirttila T, Rinne J, Jaaskelainen JE, Soininen H, Rinne JO. Assessment of beta-amyloid in a frontal cortical brain biopsy specimen and by positron emission tomography with carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.noc80013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Svedberg MM, Hall H, Hellstrom-Lindahl E, Estrada S, Guan Z, Nordberg A, Langstrom B. [(11)C]PIB-amyloid binding and levels of Abeta40 and Abeta42 in postmortem brain tissue from Alzheimer patients. Neurochemistry international. 2009;54:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Wuu J, Mathis CA, Scheff SW, Mufson EJ, DeKosky ST. Precuneus amyloid burden is associated with reduced cholinergic activity in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:39–47. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182231419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schmitt FA, Wetherby MM, Wekstein DR, Dearth CM, Markesbery WR. Brain donation in normal aging: procedures, motivations, and donor characteristics from the Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies (BRAiNS) Project. Gerontologist. 2001;41:716–722. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, Davis DG, Poduska JW, Patel E, Mendiondo MS, Markesbery WR. Modeling the Association between 43 Different Clinical and Pathological Variables and the Severity of Cognitive Impairment in a Large Autopsy Cohort of Elderly Persons. Brain Pathol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Holler CJ, Webb RL, Laux AL, Beckett TL, Niedowicz DM, Ahmed RR, Liu Y, Simmons CR, Dowling AL, Spinelli A, Khurgel M, Estus S, Head E, Hersh LB, Murphy MP. BACE2 Expression Increases in Human Neurodegenerative Disease. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, 3rd, Schneider JA, Grinberg LT, Halliday G, Duyckaerts C, Lowe JS, Holm IE, Tolnay M, Okamoto K, Yokoo H, Murayama S, Woulfe J, Munoz DG, Dickson DW, Ince PG, Trojanowski JQ, Mann DM. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schmitt FA, Davis DG, Wekstein DR, Smith CD, Ashford JW, Markesbery WR. “Preclinical” AD revisited: neuropathology of cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2000;55:370–376. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Markesbery WR, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Davis DG, Smith CD, Wekstein DR. Neuropathologic substrate of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Beckett TL, Niedowicz DM, Studzinski CM, Weidner AM, Webb RL, Holler CJ, Ahmed RR, LeVine H, 3rd, Murphy MP. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on amyloid-beta pathology in mouse skeletal muscle. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Das P, Howard V, Loosbrock N, Dickson D, Murphy MP, Golde TE. Amyloid-beta immunization effectively reduces amyloid deposition in FcRgamma−/− knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8532–8538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08532.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].McGowan E, Pickford F, Kim J, Onstead L, Eriksen J, Yu C, Skipper L, Murphy MP, Beard J, Das P, Jansen K, Delucia M, Lin WL, Dolios G, Wang R, Eckman CB, Dickson DW, Hutton M, Hardy J, Golde T. Abeta42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron. 2005;47:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Weidner AM, Bradley MA, Beckett TL, Niedowicz DM, Dowling AL, Matveev SV, Levine H, 3rd, Lovell MA, Murphy MP. RNA Oxidation Adducts 8-OHG and 8-OHA Change with Abeta(42) Levels in Late-Stage Alzheimer's Disease. PloS one. 2011;6:e24930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Head E, Pop V, Sarsoza F, Kayed R, Beckett TL, Studzinski CM, Tomic JL, Glabe CG, Murphy MP. Amyloid-beta peptide and oligomers in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of aged canines. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:637–646. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].LeVine H., 3rd Alzheimer's beta-peptide oligomer formation at physiologic concentrations. Anal Biochem. 2004;335:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rosen RF, Walker LC, Levine H., 3rd PIB binding in aged primate brain: Enrichment of high-affinity sites in humans with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand J Statist. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Steinhorn SC, Abbott RD, Markesbery W, Davis D, Nelson J, Hardman J, Masaki K, Vogt MR, Launer L, White LR. AD lesions and infarcts in demented and non-demented Japanese-American men. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:98–103. doi: 10.1002/ana.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Petrovitch H, Ross GW, He Q, Uyehara-Lock J, Markesbery W, Davis D, Nelson J, Masaki K, Launer L, White LR. Characterization of Japanese-American men with a single neocortical AD lesion type. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;29:1448–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Larner AJ. The cerebellum in Alzheimer's disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 1997;8:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000106632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gowing E, Roher AE, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Chaney M, Little SP, Ball MJ. Chemical characterization of A beta 17–42 peptide, a component of diffuse amyloid deposits of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:10987–10990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Shirotani K, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Hama E, Lee HJ, Saido TC. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang S, Wang R, Chen L, Bennett DA, Dickson DW, Wang DS. Expression and functional profiling of neprilysin, insulin-degrading enzyme, and endothelin-converting enzyme in prospectively studied elderly and Alzheimer's brain. J Neurochem. 2010;115:47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yasojima K, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Relationship between beta amyloid peptide generating molecules and neprilysin in Alzheimer disease and normal brain. Brain Res. 2001;919:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chromy BA, Chang L, Morgan TE, Yu J, Venton DL, Krafft GA, Finch CE, Klein WL. Vaccination with soluble Abeta oligomers generates toxicity-neutralizing antibodies. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:595–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochemistry international. 2002;41:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Mc Donald JM, Savva GM, Brayne C, Welzel AT, Forster G, Shankar GM, Selkoe DJ, Ince PG, Walsh DM. The presence of sodium dodecyl sulphate-stable Abeta dimers is strongly associated with Alzheimer-type dementia. Brain. 2010;133:1328–1341. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Maeda J, Ji B, Irie T, Tomiyama T, Maruyama M, Okauchi T, Staufenbiel M, Iwata N, Ono M, Saido TC, Suzuki K, Mori H, Higuchi M, Suhara T. Longitudinal, quantitative assessment of amyloid, neuroinflammation, and anti-amyloid treatment in a living mouse model of Alzheimer's disease enabled by positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10957–10968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0673-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jack CR, Jr., Albert MS, Knopman DS, McKhann GM, Sperling RA, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.