Abstract

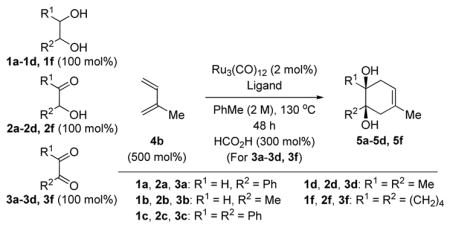

The ruthenium(0) catalyst generated from Ru3(CO)12 and tricyclohexylphosphine or BIPHEP promotes successive C-C coupling of dienes to vicinally dioxygenated hydrocarbons across the diol, hydroxyketone and dione oxidation levels to form products of [4+2] cycloaddition. A mechanism involving diene-carbonyl oxidative coupling followed by intramolecular carbonyl addition from the resulting allylruthenium intermediate is postulated.

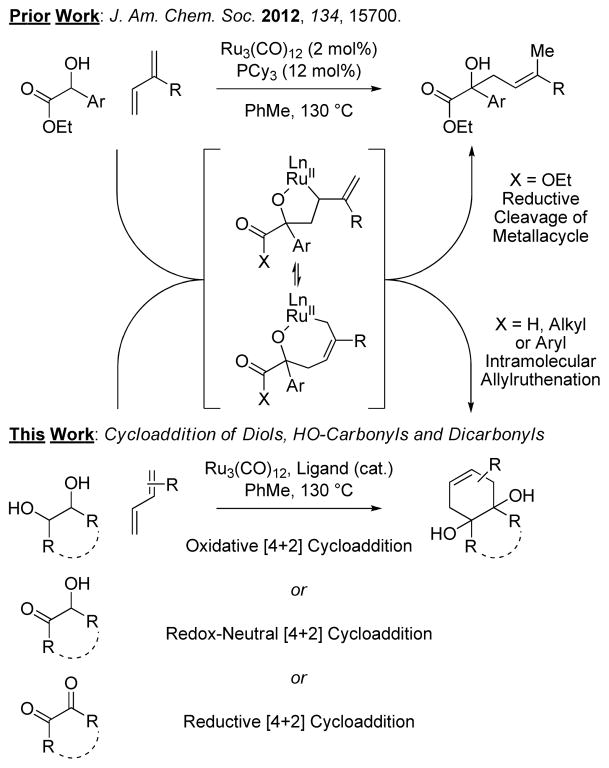

Vicinal diols are ubiquitous in Nature and are of interest vis-à-vis biomass conversion,1,2 yet there exist no examples of their direct catalytic C-C coupling. We have developed a broad family of transformations wherein hydrogen transfer between alcohols and π-unsaturated reactants produces organ-ometal-carbonyl pairs that combine to form products of addition.3 In the course of these studies, a ruthenium(0) catalyst recently was identified that promotes alcohol C-C coupling through an alternate mechanism, wherein alcohol dehydrogenation drives carbonyldiene oxidative coupling to form metallacyclic intermediates, as illustrated in couplings of α-hydroxy esters to isoprene or myrcene to form products of prenylation or geranylation, respectively.4 It was posited that the allylruthenium species arising transiently upon diene-carbonyl oxidative coupling might be intercepted via allylruthenation onto a tethered carbonyl moiety to form products of cycloaddition, suggesting the feasibility of utilizing diols as partners for C-C coupling. Here, we report that vicinal diols and their more highly oxidized forms (hydroxyketones and diones) engage in [4+2] cycloaddition with a diverse range of conjugated dienes – a powerful, new cycloaddition that may be conducted in reductive, redox-neutral or oxidative modes (Figure 1).5,6

Figure 1.

Cycloaddition of vicinally dioxygenated hydrocarbons through interception of an allylruthenium intermediate.

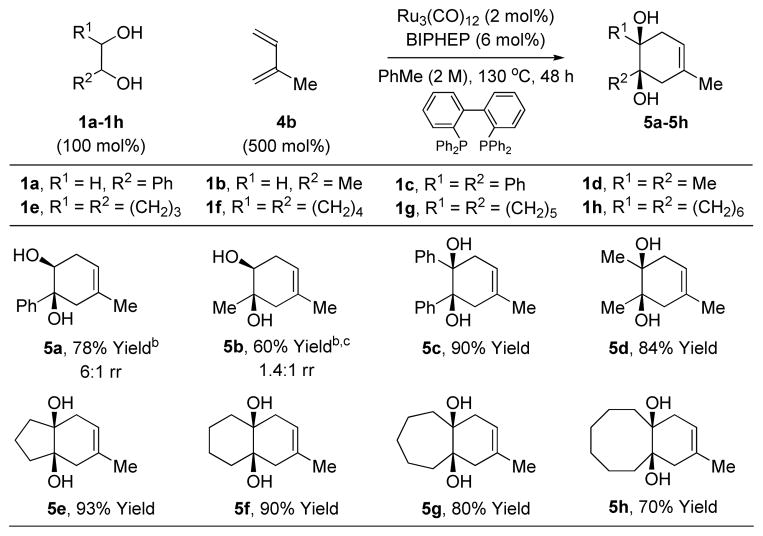

Following the mechanism postulated above, the phenethyl diol 1a was exposed to isoprene 4b in the presence of sub-stoichiometric quantities of Ru3(CO)12 and tricyclohexylphosphine, PCy3, at 130 °C in toluene solvent. Remarkably, the product of cycloaddition 5a was obtained in 78% isolated yield as a 6:1 mixture of regioisomers. Whereas PCy3 was the preferred ligand for terminal 1,2-diols 1a-1b, a screen of phosphine ligands revealed that the chelating phosphine ligand BIPHEP, 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-biphenyl, was the better for internal 1,2-diols 1c-1h. For internal diols 1c-1h, cis- or trans-diastereomers react with equal facility (Table 1).

Table 1.

Oxidative ruthenium catalyzed [4+2] cycloaddition of isoprene 4b with diols 1a-1h.a

|

Yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography.

PCy3 (12 mol%).

150 °C. See Supporting Information for further details and structural assignments.

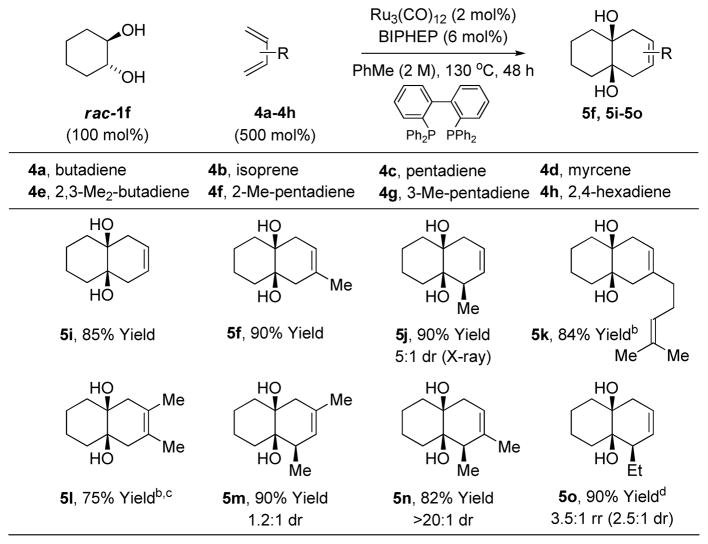

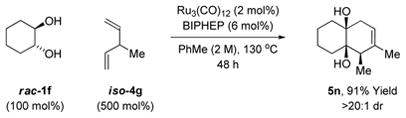

The scope of the diene partner is illustrated in cycloadditions of rac-cyclohexanediol 1f. Butadiene 4a and a range of substituted dienes 4b-4h participate in the ruthenium catalyzed cycloaddition to furnish decalins 5f, 5i-5o in excellent yield. A single substituent is tolerated at any position of the diene. For the dimethyl substituted butadienes 4e-4g, good to excellent yields of cycloadducts 5l-5o, respectively, are obtained. For the terminally disubstituted diene 4h, 2,4-hexadiene, substantial olefin isomerization in advance of cycloaddition is observed (Table 2). Indeed, Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed olefin isomerization has been documented.7 This phenomena is advantageous in terms of recruiting non-conjugated dienes as partners for cycloaddition. For example, rac-cyclohexanediol 1f was reacted with the non-conjugated diene iso-4g (eqn. 1). Remarkably, iso-4g and 4g produce cycloadduct 5n with roughly equal facility.

Table 2.

Ruthenium catalyzed [4+2] cycloaddition of rac-cyclohexanediol 1f with dienes 4a-4h.a

|

Yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography.

300 mol% diene.

150 °C.

The same products are generated in the same distribution using 1,5-hexadiene. See Supporting Information for further details and structural assignments.

|

(1) |

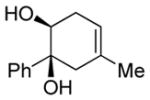

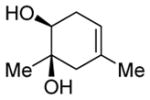

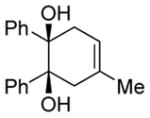

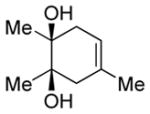

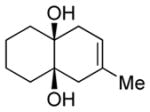

The cycloadditions of diols 1a-1h are oxidative processes wherein excess diene presumably serves as the hydrogen acceptor (Tables 1 and 2). The feasibility of cycloaddition from more highly oxidized congeners of diols 1a-1d and 1f were evaluated in reactions with isoprene 4b (Table 3). In the event, exposure of the α-hydroxycarbonyl compounds 2a-2d and 2f to standard conditions employing substoichiometric quantities of Ru3(CO)12 and either PCy3 or BIPHEP as ligand provided the cycloadducts 5a-5d and 5f in good to excellent yield. Whereas reactions of α-hydroxycarbonyl compounds 2a-2d and 2f are redox-neutral processes, cycloadditions of the corresponding dicarbonyl compounds 3a-3d and 3f are reductive processes requiring a stoichiometric hydrogen donor. For such dicarbonyl reactants, formic acid proved to be most effective reductant, and use RuH2CO(PPh3)3 as precatalyst was advantageous in certain cases.8 While glyoxals 3a and 3b failed to deliver any cycloadduct, the vicinal diketones 3c, 3d and 3f provided the anticipated products 5c, 5d and 5f in modest yields. Thus, ruthenium catalyzed [4+2] cycloaddition is achieved from the diol, hydroxycarbonyl and dicarbonyl oxidation levels.

Table 3.

Ruthenium catalyzed [4+2] cycloaddition of isoprene 4b with vicinally dioxygenated hydrocarbons 1a-1d, 1f, 2a-2d, 2f, and 3a-3d, 3f.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Cycloadduct | Reactant | Yield % |

| 1 |

|

Diol 1a | 78b |

| Hydroxyketone 2a | 75b | ||

| Dicarbonyl 3a | Trace | ||

| 2 |

|

Diol 1b | 60b,e |

| Hydroxyketone 2b | 72b | ||

| Dicarbonyl 3b | Trace | ||

| 3 |

|

Diol 1c | 90c |

| Hydroxyketone 2c | 98c | ||

| Dicarbonyl 3c | 70d | ||

| 4 |

|

Diol 1d | 84b |

| Hydroxyketone 2d | 61b | ||

| Dicarbonyl 3d | 35d,f | ||

| 5 |

|

Diol 1f | 90b |

| Hydroxyketone 2f | 68b | ||

| Dicarbonyl 3f | 54d,f | ||

Yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography.

PCy3 (12 mol%).

BIPHEP (6 mol%).

RuH2CO(PPh3)3 (6 mol%), BIPHEP (6 mol%).

150 °C.

HCO2H (300 mol%). See Supporting Information for further details and structural assignments.

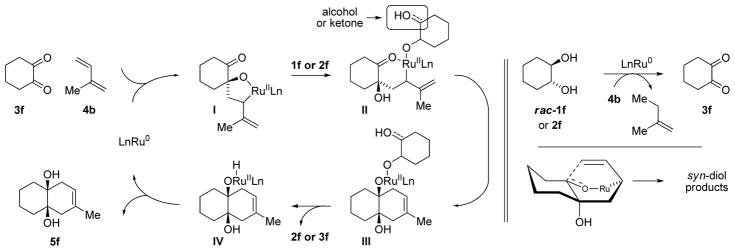

A general catalytic mechanism has been proposed, as illustrated in the cycloaddition of rac-cyclohexanediol 1f and isoprene 4b (Scheme 1). It is well established that exposure of Ru3(CO)12 to chelating phosphine ligands provides complexes of the type Ru(CO)3(diphosphine).9 Hence, intervention of a discrete, mono-metallic catalyst is anticipated. The Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed oxidation of alcohols employing olefins and alkynes as hydrogen acceptors has been described.10,11 Further, mechanistically related Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed secondary alcohol aminations involving dehydrogenation of 1,2-diols12a and α-hydroxy esters12c are known. These data suggest the present Ru3(CO)12-phosphine catalyst system is capable of converting 1,2-diol 1f to the hydroxyketone 2f and, ultimately, the corresponding 1,2-dione 3f using diene 4b as the hydrogen acceptor.10 The diol rac-1f, which is introduced as the isomerically pure trans-stereoisomer, appears as a mixture of cis- and trans-diastereomers when recovered from the reaction mixture, suggesting dehydrogenation of 1f is reversible. Small quantities of hydroxyketone 2f also can be recovered from reaction mixtures. Oxidative coupling of 1,2-dione 3f and diene 4b to form oxametallacycle I finds precedent in the work of Chatani and Murai on Pauson-Khand type reactions of 1,2-diones,13 and our own work on the prenylation of substituted mandelic esters.4 Protonolytic cleavage of oxametallacycle I by 1f or 2f to form the allylruthenium complex II triggers intramolecular allylruthenation to form the ruthenium(II) alkoxide III. Finally, β-hydride elimination forms ruthenium hydride IV and OH reductive elimination delivers the product 5f and returns ruthenium to its zero-valent form to close the cycle.14

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism and stereochemical model for the cycloaddition of rac-cyclohexanediol 1f and isoprene 4b.

The assignment of regio- and stereochemistry merit discussion. Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of cycloadduct 5j revealed the cis-diastereomer. Additionally, the 1H NMR spectral characteristics of cycloadducts 5i and 5l are consistent with the indicated meso-stereoisomers, not the corresponding C2-symmetric stereoisomers. The stereochemical assignment of other cycloadducts was made in analogy to compounds 5j, 5i and 5l. A model accounting for the observed syn-diastereoselectivity is presented has been postulated, which involves intramolecular allylruthenation through a boat-like transition structure. Finally, aromatization of cycloadduct 5a via acid catalyzed double dehydration enabled the regiochemical assignment of this cycloadduct (see supporting information). Indeed, a systematic investigation of diol cycloaddition-aromatization is now underway in our laboratory.

In summary, since the advent of the photocycloaddition in 190815a and the Diels-Alder reaction in 1928,15b several distinct and powerful classes of cycloaddition reactions have been developed, including diverse metal catalyzed processes.16 However, despite decades of intensive investigation, reductive and oxidative variants of cycloaddition reactions remain highly uncommon.5,6 Here, we report a powerful and conceptually novel strategy for the [4+2] cycloaddition of dienes with 1,2-diols and their higher vicinally dioxygenated congeners. This work demonstrates that merged redox-construction events17 can be exploited in succession to form multiple C-C bonds, enabling generation of complex polycyclic frameworks in the absence of premetallated reagents. The development of related transformations and application of this methodology to the direct modification of abundant renewable polyols is ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0038), the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM069445) and the Government of Canada’s Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (L.M.G.) are acknowledged for partial support of this research. Firmenich is acknowledged for unrestricted partial financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data. Single crystal X-ray diffraction data for compound 5j. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For recent reviews of the conversion of biomass to commodity chemicals, see: Ragauskas AJ, Williams CK, Davison BH, Britovsek G, Cairney J, Eckert CA, Frederick WJ, Jr, Hallett JP, Leak DJ, Liotta CL, Mielenz JR, Murphy R, Templer R, Tschaplinski T. Science. 2006;311:484. doi: 10.1126/science.1114736.Sheldon RA. Catal Today. 2011;167:3.Gallezot P. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1538. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15147a.Dapsens PY, Mondelli C, Perez-Ramirez J. ACS Catal. 2012;2:1487.

- 2.For selected examples of catalytic diol deoxydehydration to form olefins, see: Gable KP, Juliette JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2625.Cook GK, Andrews MA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9448.Ziegler JE, Zdilla MJ, Evans AJ, Abu-Omar MM. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:9998. doi: 10.1021/ic901792b.Ziegler JE, Zdilla MJ, Evans AJ, Abu-Omar MM. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:9998. doi: 10.1021/ic901792b.Vkuturi S, Chapman G, Ahmad I, Nicholas KM. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:4744. doi: 10.1021/ic100467p.Ahmad I, Chapman G, Nicholas KM. Organometallics. 2011;30:2810.

- 3.For recent reviews on C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Bower JF, Krische MJ. Top Organomet Chem. 2011;43:107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_5.Hassan A, Krische MJ. Org Proc Res Devel. 2011;15:1236. doi: 10.1021/op200195m.Moran J, Krische MJ. Pure Appl Chem. 2012;84:1729. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-11-10-18.

- 4.Leung JC, Geary LM, Chen TY, Zbieg JR, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15700. doi: 10.1021/ja3075049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For selected examples of metal catalyzed oxidative (dehydrogenative) cycloadditions, see: Nakao Y, Morita E, Idei H, Hiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3264. doi: 10.1021/ja1102037.Stang EM, White MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14892. doi: 10.1021/ja2059704.Masato O, Ippei T, Masashi I, Sensuke O. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18018.

- 6.For selected examples of metal catalyzed reductive cycloadditions, see: Herath A, Montgomery J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14030. doi: 10.1021/ja0660249.Chang HT, Jayanth TT, Cheng CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4166. doi: 10.1021/ja0710196.Williams VM, Kong JR, Ko BJ, Mantri Y, Brodbelt JS, Baik MH, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16054. doi: 10.1021/ja906225n.Jenkins AD, Herath A, Song M, Montgomery J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14460. doi: 10.1021/ja206722t.Ohashi M, Taniguchi T, Ogoshi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14900. doi: 10.1021/ja2059999.Wei CH, Mannathan S, Cheng CH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10592. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205115.

- 7.For selected examples of Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed olefin isomerization, see: Kaspar J, Spogliarich R, Graziani MJ. Organomet Chem. 1985;281:299.Hilal Hikmat S, Shukri Khalaf, Jondi WJ. Organomet Chem. 1993;452:167.Jun CH, Lee H, Park JB, Lee DY. Org Lett. 1999;1:2161.Alvila L, Pakkanen TA, Krause O. J Mol Catal. 1993;84:145.

- 8.The precatalyst RuH2CO(PPh3)3 may reductively eliminate elemental hydrogen or transfer hydrogen to the diene to furnish the zero-valent ruthenium species required for diene-carbonyl oxidative coupling.

- 9.For example, exposure of Ru3(CO)12 to dppe in benzene solvent provides Ru(CO)3(dppe): Sanchez-Delgado RA, Bradley JS, Wilkinson G. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1976:399.

- 10.(a) Blum Y, Reshef D, Shvo Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1541. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shvo Y, Blum Y, Reshef D, Menzin M. J Organomet Chem. 1982;226:C21. [Google Scholar]; (c) Meijer RH, Ligthart GBWL, Meuldijkb J, Vekemans JAJM, Hulshof LA, Mills AM, Kooijmanc H, Spek AL. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1065. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For mechanistically related Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of ketones mediated by isopropanol, see: Johnson TC, Totty WG, Wills M. Org Lett. 2012;14:5230. doi: 10.1021/ol302354z.

- 12.For mechanistically related Ru3(CO)12 catalyzed secondary alcohol amination via alcohol mediated hydrogen transfer, see: Baehn S, Tillack A, Imm S, Mevius K, Michalik D, Hollmann D, Neubert L, Beller M. ChemSusChem. 2009;2:551. doi: 10.1002/cssc.200900034.Pingen D, Müller C, Vogt D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8130. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002583.Zhang M, Imm S, Bahn S, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104309. Also see reference 4.

- 13.(a) Chatani N, Tobisu M, Asaumi T, Fukumoto Y, Murai S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7160. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tobisu M, Chatani N, Asaumi T, Amako K, Ie Y, Fukumoto Y, Murai S. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12663. [Google Scholar]

- 14.A Diels-Alder mechanism involving pericyclic [4+2] cycloaddition of a ruthenium-bound enediolate can be excluded as β-hydroxy ketones were found to participate in the cycloaddition. A detailed account of this process will be reported in due course.

- 15.(a) Ciamician G, Silber P. Chem Ber. 1908;41:1928. [Google Scholar]; (b) Diels O, Alder K. Ann. 1928;460:98. [Google Scholar]

- 16.For a review of metal catalyzed cycloadditions, see: Lautens M, Klute W, Tam W. Chem Rev. 1996;96:49. doi: 10.1021/cr950016l.

- 17.For a review of “redox economy”, see: Baran PS, Hoffmann RW, Burns NZ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806086.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.