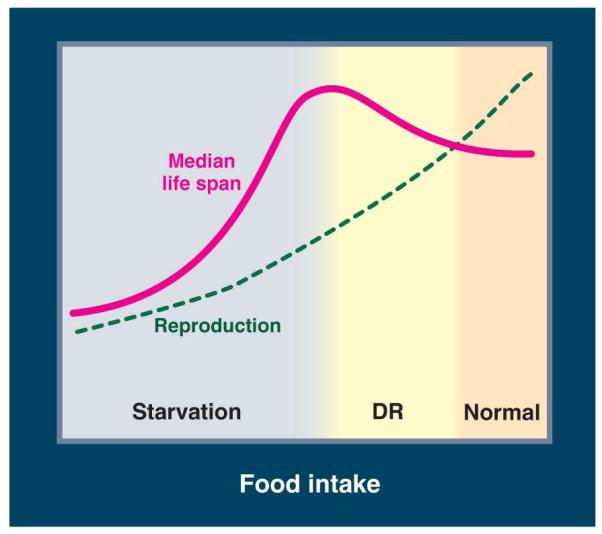

Abstract

Dietary restriction (DR) and reduced growth factor signaling both elevate resistance to oxidative stress, reduce macromolecular damage, and increase lifespan in model organisms. In rodents, both DR and decreased growth factor signaling reduce the incidence of tumors and slow down cognitive decline and aging. DR reduces cancer and cardiovascular disease and mortality in monkeys, and reduces metabolic traits associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer in humans. Neoplasias and diabetes are also rare in humans with loss of function mutations in the growth hormone receptor. DR and reduced growth factor signaling may thus slow aging by similar, evolutionarily conserved, mechanisms. We review these conserved anti-aging pathways in model organisms, discuss their link to disease prevention in mammals, and consider the negative side effects that might hinder interventions intended to extend healthy lifespan in humans.

1. Introduction

Aging is a complex process associated with accumulation of damage, loss of function and increased vulnerability to disease, leading ultimately to death. Despite the complicated aetiology of aging, simple genetic alterations can cause a substantial increase in healthy lifespan in laboratory model organisms (Fig. 1). Many of these longevity-extending mutations decrease the activity of nutrient-signalling pathways, suggesting that they promote a physiological state similar to that experienced during periods of food shortage in nature. Indeed, dietary restriction (DR), a reduction in food intake without malnutrition, extends the average and/or maximum life span of various organisms including yeast, flies, worms, fish, rodents and rhesus monkeys. In both rodents and monkeys, it also delays loss of function and reduces the incidence of major diseases (1) and in humans it causes a reduction in metabolic markers of several diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer (2). Hence, understanding the mechanisms responsible for lifespan-extension has the potential to reveal targets for drugs and therapies directed at broad-spectrum prevention of aging-related loss of function and disease. We discuss genetic alterations to nutrient-sensing pathways and nutritional interventions that extend lifespan and ameliorate age-related loss of function and disease, focusing on interventions and effects that are conserved in multiple organisms. We discuss the evidence for potentially protective and also for detrimental effects in humans.

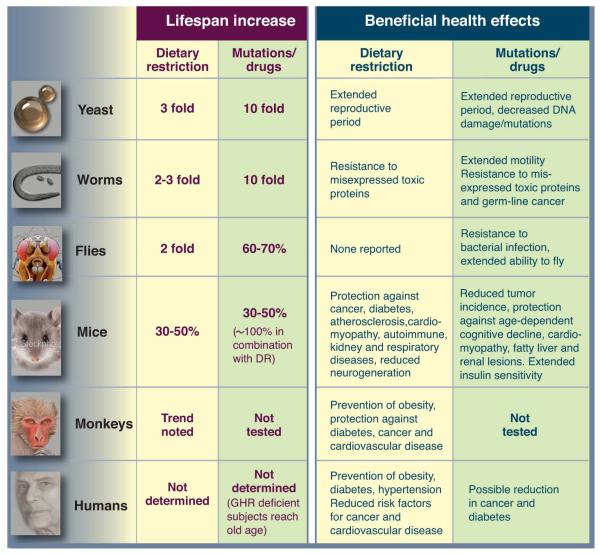

Figure 1.

A) A model for the conserved nutrient signaling pathways that regulate longevity in various organisms and mammals (see text). The role of the TOR-S6K pathway in promoting aging appears to be conserved from yeast to mammals. By contrast, both the AC-PKA pathways and the and TOR-S6K pathway promote aging in yeast and mammals, whereas an insulin/IGF-I-like receptor accelerates aging in worm, flies, and possibly mice. Similar transcription factors (GIS1, MSN2/4, DAF-16, FOXO) affect either stress resistance or aging in all the major model organisms. Notably, in the multicellular worms, flies and mice, it is the function of these genes and pathways in particular cell types that affect aging and stress resistance, as depicted for mammals in panel B (see text). B) Deficiency in GH/IGF-I signaling leads to life span extension and increased stress resistance in various mouse cell types (see text).

2. Interpreting data on genetics, dietary restriction, and aging

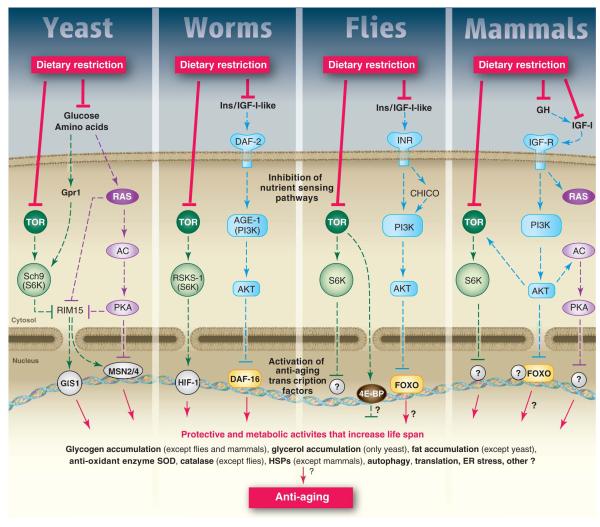

The role of particular genes in the response of lifespan to DR has been investigated by determining if a genetic alteration alters this response. Many, but not all, methods of DR allow exploration of the effects of a range of food intake in worms, flies, and probably mice (3). Lifespan rises to a maximum as the food intake is lowered, but can decline rapidly if the food supply is further reduced (Fig. 2).. Therefore, the effects of mutations should be examined over a broad range of food intakes, so that the degree of DR that maximizes life span can be determined and used in tests for genetic effects (3).

Figure 2.

Food level, fecundity and longevity. Median life span and fecundity are negatively affected by a very low nutrient concentration in higher eukaryotes. However, life span but not fecundity is optimized by DR.

Genetic analysis can only give an indication of underlying molecular mechanisms, and other approaches are required to establish the normal roles of particular gene products in extension of lifespan by DR. The idea that a single linear pathway may mediate the effects of DR is probably unrealistic. The matching of metabolism, growth, and reproduction to food intake are crucial aspects of the fitness of animals in nature, and parallel and redundant pathways appear to be involved. Different organisms can grow and reproduce at very different rates, and experience different degrees of food shortage in nature. The type of food and the way in which it is sensed are also highly variable. Thus responses of organisms to DR may differ to some extent in mechanism, extent and kind.

3. Nutrients sensing pathways, dietary restriction, and aging in yeast

Nutrient-sensing pathways

Aging in yeast is measured by monitoring the number of daughter cells generated by an individual mother cell (replicative life span, RLS) or by monitoring the survival of a population of non-dividing cells (chronological life span, CLS). In S. cerevisiae, glucose, amino acids and other nutrients can activate a pathway which includes Ras, adenylate cyclase (AC), and Protein Kinase A (PKA) or a pathway including the target of Rapamycin (TOR) and the serine threonine kinase Sch9 (Fig. 1A). Deletion or inactivation of various components of the Ras-AC-PKA pathway delays both replicative and chronological aging (Fig. 1A) (4, 5). The stress resistance transcription factors Msn2 and Msn4 are required for the effect of reduced Ras-AC-PKA on CLS extension (Fig. 1A) (4) and may mediate the extension of RLS (6). The other major pro-growth and pro-aging pathway in yeast is centered on Tor and Sch9 and partially overlaps with the Ras-AC-PKA pathway (Fig. 1A) (7). Deletion of SCH9, a gene with sequence similarity to those encoding AKT and ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) but more functionally related to S6 kinase, causes a 3-fold extension of CLS and a 5-fold extension when combined with the deletion of RAS2 (Fig. 1) (7). Deletion of SCH9 also causes one of the largest increases in RLS (8, 9) and deletion or inhibition of TOR1 extends both chronological and replicative life span (8, 9,Wei, 2009 #15), probably by causing the inactivation of the downstream Sch9 (Fig. 1A) (8, 10, 11). Tor and Sch9 lead to inactivation of the serine threonine kinase Rim15 and of the stress resistance transcription factor Gis1, both of which are required for maximum chronological life span extension (4). Analogously to Msn2 and Msn4, Gis1 increases the expression of MnSOD, an antioxidant required for the effect of sch9 deletion on chronological life span (Fig. 1A) (7). In agreement with these results, the level of superoxide and other oxidants increases during yeast aging and is reduced in long-lived mutants deficient in Ras-AC-PKA or Tor-Sch9 signaling (4). However, the overexpression of either SOD1 or SOD2 or of catalase in yeast does not result in a significant mean survival extension; and overexpression of both SOD1 and SOD2 extended survival by only 30%. Tor and Sch9 also promote age-dependent DNA damage/mutations in part by their effect on superoxide generation and in part by activating an error prone polymerase system (4).

In the early stages of the CLS, the cells deplete glucose and accumulate ethanol, acetic acid or both, which have been shown to promote chronological aging (12, 13). Deletion of TOR1or SCH9 protects against aging in part by reducing respiration and promoting the depletion of ethanol and probably acetic acid and the accumulation of glycerol in the medium (11, 13). Since acetic acid and ethanol are non-fermentable carbon and energy sources for S. cerevisiae (yeast can grow in 2% ethanol or 2% acetate as carbon sources), their removal by mutations in the TOR-SCH9 pathways appears to extend CLS by generating the conditions normally generated by DR or incubation in water (11-13). In fact, the CLS extension caused by incubation onto agar plates lacking nutrients is reversed by adding 2% glucose (11). Notably, the CLS of TOR-SCH9 or RAS-AC-PKA deficient cells is also extended during incubation in water or on solid medium in which acetic acid and ethanol are either absent or present at very low concentrations (11, 13) indicating that, as described earlier, Tor-Sch9 and AC-PKA pathways can regulate life span by increasing cellular protection independently of their effect on extracellular carbon sources (Fig. 1). Although the regulation of ethanol, acetic acid, and glycerol release and uptake may be viewed as a “private” mechanism limited to aging in yeast, it is likely to point to “public” mechanisms relevant to aging and/or diseases in higher eukaryotes. For example, in mammals glycerol is important for gluconeogenesis during fasting and the build-up of lactic acid in the human blood can cause metabolic acidosis, toxicity, and even death.

Dietary restriction

In S. cerevisiae, starvation implemented by switching the cells from medium containing nutrients to water, causes a doubling of the CLS (7, 14). More moderate reductions of glucose in the growth medium from the standard 2% to 0.5 or 0.05% also extend both RLS and CLS, although it is not clear whether the same genetic pathways regulate RLS and CLS life span or whether they regulate life span extension in both water and in the reduced glucose media (5, 7, 8, 15). Effects of a 0.5% glucose DR on RLS are thought to involve decrease signaling of the Ras-AC-PKA and Tor-Sch9 pathways (Fig. 1), increased transcriptional activity of Msn2 and Msn4 and the consequent expression of Pnc1, a nicotinamide deaminase that regulates the activity of the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sir2 (6, 16). Altered translation and autophagy are thought to also contribute to replicative longevity (16).

Inhibition of both the Ras-AC-PKA and Tor-Sch9 pathways is implicated in DR-dependent extension of CLS as well (Fig. 1). In fact, the lack of the Rim15 protein kinase or the triple deletion of transcription factors MSN2, MSN4, and GIS1 reverse the effects of starvation or dietary restriction on longevity (7).

4. Nutrient-sensing pathways, dietary restriction and lifespan in the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans

Nutrient Sensing pathways

Mutations that extended lifespan were first discovered in C. elegans, and led to the discovery of the role of the IIS (insulin/Igf-like signaling pathway) in ageing (17). Increased lifespan from reduced IIS requires the Forkhead FoxO transcription factor daf-16 (Fig. 1A), which regulates genes involved in a wide range of defensive activities including cellular stress-response, antimicrobial activity, and detoxification of xenobiotics and free radicals (Fig. 1A). Extension of lifespan by reduced IIS also requires the heat shock factor hsf-1, which regulates expression of small heat shock proteins (17). Over-expression of hsf-1 itself extends worm lifespan. The nervous system and the gut, which includes white adipose tissue and performs various metabolic functions, have been implicated in extension of lifespan by reduced IIS in C. elegans (17). Regulation of insulin ligands by DAF-16 acts systemically to co-ordinate the rate of aging, with elevated DAF-16 levels in the intestine increasing activity of DAF-16 in other tissues. DAF-16 regulates ins-7 expression in the intestine and, when this regulation is blocked, increased FOXO levels in the intestine no longer affect FOXO activity elsewhere (17).

Inhibition of TOR/S6 kinase pathway activity at several points, including TOR kinase itself and S6 kinase, a homolog of the pro-aging yeast SCH9, can increase lifespan in C. elegans (Fig. 1A) (17-19). Autophagy, a target of TOR signaling, is required for the increase in survival (19) and altered activity of several other targets of the TOR pathway, such as translation (20) and HIF-1 activity (21, 22) can independently extend lifespan. Reduced IIS and TOR activity thus can increase worm lifespan, through multiple parallel pathways that may interact.

Dietary restriction

Multiple methods of dietary restriction are used in C. elegans, including mutations that reduce pharyngeal pumping, removal of the bacterial food source, dilution of live or dead bacteria in solid or liquid cultures, peptone dilution and axenic culture (23). Reduced food intake may not be the only route by which DR extends lifespan, because diffusible substances from bacteria can reduce lifespan without reduced food intake (24). As in rodents, at least one method of DR, requiring heat shock factor-1, can protect against proteotoxicity associated with age-related disease (25).

Different methods of DR in C. elegans operate through both overlapping and non-overlapping mechanisms (23, 26). For instance, the key IIS effector DAF-16 is not required for extension of lifespan by eat mutations or some forms of bacterial dilution, but is required for another form of bacterial dilution and peptone dilution (26), again pointing to the possibility of parallel pathways, and redundancy between them (Fig. 2A).

As in yeast, the responses to DR in C. elegans involve nutrient-sensing pathways. The role of TOR has been tested only with eat mutants, which do not allow a range of food intakes to be investigated, and with inconsistent results (23). However, targets of the TOR pathway, such as autophagy and HIF-1 clearly contribute to the DR response (23). IIS also plays a role because some methods of DR require DAF-16, and in these cases the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is also required (Fig. 1A) (26).

Two other transcription factors, Pha-4 together with the co-factor SMK-1, and SKN-1, are required for the response to some, but not all, methods of DR in C. elegans (Fig. 1A) (23). Pha-4 is the single worm orthologue of the mammalian Foxa family of forkhead transcription factors, which in adulthood play key roles in metabolic homeostasis. A HECT E3 ubiquitin ligase acts upstream of Pha-4 (27). SKN-1 is the worm orthologue of the mammalian Nfe2l1 and Nfe2l2 transcription factors, which induce the Phase II detoxification pathway, as does SKN-1 in C. elegans. Increased activity of SKN-1can increase worm lifespan (28). sir-2.1, the worm orthologue of yeast SIR2, has also been implicated in the response DR, but the emerging consensus is that all forms of DR in C. elegans so far investigated can occur in the absence of sir-2.1 (23).

5. Nutrient-sensing pathways, dietary restriction and aging in the fruit fly Drosophila

Nutrient Sensing pathways

The finding that reduced IIS could extend lifespan in Drosophila established the evolutionarily conserved role of this pathway in aging (Fig. 1A) (20). It is not yet known whether, as in C. elegans, the single fly FOXO is required for this extension of lifespan (Fig. 1A).

Changes in gene expression in long-lived IIS mutants in Drosophila, C. elegans and mouse have implicated Phase 1 and 2 cellular detoxification and xenobiotic metabolism as evolutionarily conserved targets of IIS (20, 29). Long-lived IIS mutants in all 3 organisms are resistant to xenobiotics, and up-regulation of transcription factors that regulate xenobiotic metabolism can extend lifespan (20, 28, 29). This process is thus a candidate target for drug intervention, although potential deleterious effects of its up-regulation require investigation.

The nervous system has been implicated in extension of lifespan by reduced IIS in worm, fly and mouse. The Drosophila genome contains seven genes encoding Drosophila insulin-like peptides (dilps), and ablation of neuroendocrine cells in the brain that produce 3 DILPs extends lifespan (20). Negative feedback loops within the IIS pathway cause compensation between dilps, implying that they may act redundantly (30). Stress signaling and ablation of the germ line, reduce expression of one or more dilps in the neurosecretory cells and extend fly lifespan (31). Over-expression of dFOXO in the adult fly using inducible systems has also implicated the fat body (equivalent of mammalian white adipose tissue and liver) and/or gut (20), similar to C. elegans.

Down-regulation of TOR pathway activity by over-expression of dTsc2 or of a dominant-negative form of the S6 kinase (32) or by rapamycin (Fig. 1A) extends lifespan, implying conservation of the effects of this pathway on lifespan between yeast, C. elegans and Drosophila. Extension of lifespan by rapamycin requires autophagy, reduced S6 kinase activity and 4E-BP, and is associated with reduced protein turnover, similar to C. elegans.

Dietary Restriction

DR in Drosophila is commonly implemented by quantitative reduction either of all dietary constituents (yeast, sugar and, sometimes, a source of complex carbohydrate) or of the yeast alone (33, 34). Flies do not compensate for food dilution by increasing food intake but increase the volume of their digestive tract, and in consequence accumulate higher levels of food labels (35). Per calorie removed from the food, reduction of yeast causes a much greater extension of lifespan than does reduction of sugar, and essential amino acids mediate the increase in lifespan (36). Volatiles from live yeast, without reduction in food intake, can shorten lifespan, similar to worms, and some olfactory mutants are long-lived (37).

TOR and IIS both mediate extension of lifespan by DR in Drosophila (Fig. 1A). Down-regulation of TOR pathway activity protects against shortening of lifespan by increased food intake (32). Similarly, loss of the single fly insulin receptor substrate CHICO caused a right shift in the response of lifespan to DR (23). As in C. elegans, deletion of dFOXO shortens lifespan, but the flies continue to respond to DR (38, 39). However, over-expression of dfoxo in the fat body and gut of adult females, like deletion of CHICO, right-shifts the response of lifespan to DR (38). Taken together, these findings imply that reduced IIS plays a role in the response of lifespan to DR, but that loss of FOXO can be compensated for by other pathways, as for DR in yeast CLS (Fig. 1A). The response to DR may be mediated through reduced expression or secretion, or increased degradation, of dilps. Indeed, transcript levels of dilp5 have been shown to respond to nutrition (39). One obvious candidate for compensation for loss of FOXO is the TOR pathway.

In rodents DR produces broad-spectrum protection against aging-related loss of function and pathology. In contrast, in Drosophila DR does not arrest at least some aspects of functional decline (40), nor does it produce a general increase in stress resistance (41).

6. Nutrient-sensing pathways, dietary restriction, aging and diseases in rodents

Nutrient-sensing pathways

Mutation in the growth hormone receptor (GHR) and mutations that cause GH/IGF-I deficiency represent the genetic interventions causing the longest life span extension in mammals (42) (Fig. 1). By contrast, decreased IGF-I receptor expression extends life span by 33% in female but not male mice and the effect in females may be specific to particular genetic backgrounds (43). Because mammalian orthologs of genes that affect aging in lower eukaryotes function downstream of IGF-IR but also other receptors, it will be important to determine the role of other growth factors and proteins regulated by GH in aging and diseases.

GH deficient mice display increased expression of antioxidant enzymes or increased stress resistance in muscle cells and fibroblasts and GH administration decreased antioxidant defenses in the mouse liver, kidney, muscle and heart (Fig. 1B). Disruption of 5 adenylyl cyclase (AC5), which is predominantly expressed in the heart and brain, also increases stress resistance and longevity in mice, although GH has not been linked to AC (Fig. 1A) (44). The longevity extension and stress resistance phenotypes are shared by yeast and mice with adenylyl cyclase deficiencies and implicate MnSODs although studies by others indicate that, as described for S. cerevisiae, overexpression of either CuZnSOD or MnSOD alone does not extend life span (45). (Fig. 1A) (4, 44). Disruption of PKA, downstream of adenylyl cyclase, also causes life span extension in mice (Fig. 1A) (46). In agreement with the results in yeast, worms and flies discussed earlier, inhibition of the mTOR pathway beginning at 600 days of age extends median and maximal lifespan of mice (47) and the deletion of ribosomal S6 protein kinase 1 (S6K1), a component of the mTOR signaling pathway, leads to increased life span and resistance to age-related pathologies, including bone, immune, and motor dysfunction and insulin resistance (48). when fed TOR by rapamycin beginning at middle age The connection between signal transduction pathways and stress resistance in mammals may involve transcription factors including the orthologs of the anti-aging transcription factors described in yeast, worms and flies (Fig. 1A). Systems other than antioxidant enzymes downstream of these transcription factors including heat shock proteins, autophagy proteins, apoptosis enzymes, and others may have key functions as mediators of life span extension. Another gene linked to IIS signaling and implicated in protection against diseases is SirT1, the mammalian orthologue of yeast deacetylase SIR2. Treatment of mice on a high fat diet with resveratrol, shown to activate SirT1, results in reduced mortality or protection against morbidity, possibly by activating a set of genes affected by DR, but resveratrol did not increase survival of mice fed a standard diet (49) (The literature on sirtuins, aging and diseases is extensive and has been reviewed in detail elsewhere).

In addition to aging, these pathways affect morbidity and disease-related mortality. In fact, approximately 47% of the long-lived mice that lack the growth hormone receptor-binding protein (GHR/BP) die without obvious evidence of lethal pathological lesions, whereas only about 10% of their normal siblings do so, in agreement with studies of GH deficient mice (42, 50). In particular, GHR-BP knockout mice display a lower incidence (-49%) and delayed occurrence of fatal neoplasms, increased insulin sensitivity, and a reduction in age-dependent cognitive impairment (42), protective effects which are generally also observed in GH deficient mice (50). The reduction in neoplastic diseases in GHR-BP deficient mice may be explained in part by the lower mutation frequency observed in the liver, kidney and intestine of GH deficient dwarf mice (51).

Protection against age-related pathology including bone fractures and cardiomyopathies is also observed in the long-lived AC5 deficient mice whereas reduced age-dependent tumors and insulin resistance is observed in the PKA deficient mice (4, 44, 46). It will be important to determine whether superoxide and error-prone polymerases, implicated in the Tor-Sch9- and age-dependent DNA damage/mutations in yeast, are mediators of the GH-IGF-I-dependent genomic instability and cancer in mammals.

Dietary restriction

DR increases the rodent lifespan by up to 60% in part by delaying the occurrence of many chronic diseases, and in part by slowing the rate of biological or physiological aging (1). As observed in GHR-BP KO mice, ~30% of animals on DR die without evidence of organ pathology severe enough to be recorded as a probable cause of death whereas only 6% of controls do so (52). The DR-dependent anti-aging effects in rodents are likely mediated in part by the attenuation of IIS (Fig. 1A). In particular, the reduction of IGF-I signalling could be responsible for the reduced spontaneous mutation frequency in the kidney and small intestine of GH deficient and dietary restricted mice (51). Part of this protection against age-dependent tumors appears to be mediated by Nrf2 (53), which is functionally related to the C. elegans pro-longevity protein SKN-1.

Among its many protective effects of DR described in mice, the most notable include those on increasing insulin sensitivity and on the attenuation of B amyloid deposition in a model for Alzheimer’s Disease (54). Severe dietary restriction or starvation may also be applicable to disease treatment. For example, fasting protects mice against high dose chemotherapy in part by reducing serum IGF-I signalling but does not protect cancer cells, since oncogene mutations prevent the activation of the stress resistance pathways in response to the reduction in glucose, IGF-I and other growth factors caused by nutrient deprivation (55).

However, DR can also impair normal and beneficial function such as immunity and wound healing. For example, the healing of skin wounds is slower in long-term DR mice compared to that in ad lib fed mice and is greatly accelerated by a short period of ad lib feeding before the wound is inflicted (56). Also, DR mice are more susceptible to infections by intact bacteria, virus, and worms, even though DR can delay the age-dependent decline in certain immune functions (57).

7. Nutrient-sensing pathways, dietary restriction, aging and diseases in primates

Nutrient sensing pathways

The hypothesis that reduction of GH-IGF-I signaling can delay aging and prevent diseases can also be tested in humans by following individuals that have deficiencies in the GH-IGF-I axis (Fig. 4A). In GH receptor (GHR) deficient individuals diabetes and cancer are rarely observed, yet they do not appear to have an advantage in reaching very old ages (58) (Fig. 4A). This may be explained by the increased mortality in infants and young GHR deficient individuals (59). In a survey of patients with congenital deficiency of IGF-I, cancer was reported to be absent whereas 9–24% of first and second-degree relatives developed malignancies (58). This report is suggestive but inconclusive because the mean age of the IGF-I deficient subjects was less than half that of the controls. Although GH and/or IGF-I deficiency promotes obesity and hyperlipedemia and treatment of GH deficient individuals with GH causes a beneficial effect on waist-hip ratio and dyslipidemia, the replenishment of GH increases intima media thickness and the number of atherosclerotic plaques, indicating that the obesity associated with GH or GHR deficiency may not be detrimental (60).

Figure 4.

A) Jaime Guevara, MD (left) and a GHR deficient subject in the mountains of Southern Ecuador (right) b) Composite photograph of a DR practitioner before starting DR with adequate nutrition (on the left: weight 180 lb or 81.6 kg; BMI 26.0 kg/m2), and after 7 years of DR (on the right: weight 134 lb, or 60.8 kg; BMI 19.4 kg/m2). Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol declined from 244 mg/dl and 176 mg/dl (pre-DR) to 165 mg/dl and 97 mg/dl respectively, while HDL cholesterol increased from 37 mg/dl to 57 mg/dl. Fasting blood glucose and blood pressure declined also from 87 mg/dl and 144/87 mmHg to 74 mg/dl and 94/61 mmHg, respectively.

An overrepresentation of heterozygote mutations in the IGF-1 receptor gene that reduces its activity was found among Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians compared to controls (61) and subjects carrying at least an A allele at IGF-IR have reduced concentration of free IGF-I in plasma and their representation is increased among long-lived people (62) indicating that specific mutations that down-regulate the GH and IGF-I signaling may promote human longevity. In summary, further studies in GH or IGF-I deficient individuals vs. age- and sex-matched relatives are necessary to begin to establish the role of GH and IGF-I signaling in cancer but also in diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. If the multiple beneficial effects of reduction in GH signaling on either aging or morbidity observed in mice are confirmed in humans, drugs that block the GH and possibly IGF-I receptors could be considered for the prevention of specific diseases particularly in subjects at a high risk.

Dietary restriction

Recent data from a 20 yr longitudinal study demonstrates that a long-term 30% DR started in adult rhesus monkeys significantly reduces age-related deaths (Fig. 3) (63). The incidence of neoplasia and CVD was 50% lower in the DR monkeys than in the control animals (63), and 16 of the initial 38 control monkeys but none of the DR monkeys developed diabetes or pre-diabetes. Many of the metabolic, hormonal and structural adaptations that take place in DR rodents, including a major reduction in body fat mass, higher insulin sensitivity, and reduced inflammation and oxidative damage are also observed in DR monkeys (1). In addition, immune senescence, sarcopenia and brain athrophy of the grey matter are attenuated in DR monkeys (1, 63). Because these primates are maintained in environments that minimize infectious diseases and traumatic events, the role of DR in the mortality of monkeys in their natural environments could be different from that observed by these studies.

Figure 3.

A) Mortality from age-related causes for control and DR rhesus monkeys. Monkeys were DR for 15-20 years. B) Mortality from all causes (adapted from (63)).

Nonetheless, human studies also show profound and sustained beneficial effects of DR against obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction that are in agreement with the metabolic and functional changes observed in DR rodents (Fig. 4B)(2). DR in humans results in some of the same hormonal adaptations related to longevity in CR rodents (e.g. reduction in triiodothyronine and insulin), and reduces cholesterol, C-reactive protein, blood pressure, and intima-media thickness of the carotid arteries, that are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (64). However, major differences in the effects of DR exist between rodents and humans. For example, DR decreases serum IGF-1 concentration by ~30-40% in rodents but does not reduce total and free IGF-1 levels in healthy humans, unless protein intake is also reduced (65) (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that a high protein diet is responsible for the different effect of DR in mice and humans and raise the possibility that protein restriction alone may provide some benefits.

Because extreme DR can lead to several detrimental health effects it will be crucial to determine whether chronic severe DR in humans increases susceptibility to infections and wound-related pathologies and mortality. Additional studies are warranted to evaluate the calorie intake and relative macro- and micronutrient composition needed for optimal health and successful aging.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Min Wei for the careful reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the American Federation for Aging Research grant and by NIH AG20642, AG025135 and GM075308 to VDL. Supported also by Grant Number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research), by Istituto Superiore di Sanitá/National Institutes of Health Collaboration Program Grant, grants from Ministero della Salute, a grant from the Longer Life Foundation (an RGA/Washington University Partnership), a grant from the Bakewell Foundation (VDL and LF), and a donation from the Scott and Annie Appleby Charitable Trust.

References

- 1.Anderson RM, Shanmuganayagam D, Weindruch R. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37:47. doi: 10.1177/0192623308329476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana L, Klein S. JAMA. 2007 Mar 7;297:986. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piper MD, Partridge L. PLoS Genet. 2007 Apr 27;3:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabrizio P, Pozza F, Pletcher SD, Gendron CM, Longo VD. Science. 2001 Apr 13;292:288. doi: 10.1126/science.1059497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Science. 2000 Sep 22;289:2126. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medvedik O, Lamming DW, Kim KD, Sinclair DA. PLoS Biol. 2007 Oct 2;5:e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei M, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008 Jan;4:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaeberlein M, et al. Science. 2005 Nov 18;310:1193. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers RW, 3rd, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S. Genes Dev. 2006 Jan 15;20:174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1381406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Y, Shadel GS. Aging. 2009 Jan 28;1:131. doi: 10.18632/aging.100016. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei M, et al. PLoS Genet. 2009 May;5:e1000467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Cell Cycle. 2009 Apr 15;8:1256. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabrizio P, et al. Cell. 2005 Nov 18;123:655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longo VD, Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE, Valentine JS, Gralla EB. J Cell Biol. 1997 Jun 30;137:1581. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DL, Jr., McClure JM, Matecic M, Smith JS. Aging Cell. 2007 Oct;6:649. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaeberlein M, Burtner CR, Kennedy BK. PLoS Genet. 2007 May 25;3:e84. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panowski SH, Dillin A. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Aug;20:259. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Cell. 2003 Nov 14;115:489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen M, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008 Feb;4:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piper MD, Selman C, McElwee JJ, Partridge L. J Intern Med. 2008 Feb;263:179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Thomas EL, Kapahi P. PLoS Genet. 2009 May;5:e1000486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta R, et al. Science. 2009 May 29;324:1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1173507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mair W, Dillin A. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061206.171059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith ED, et al. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinkraus KA, et al. Aging Cell. 2008 Jun;7:394. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer EL, Brunet A. Aging Cell. 2009 Apr;8:113. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrano AC, Liu Z, Dillin A, Hunter T. Nature. 2009 Jul 16;460:396. doi: 10.1038/nature08130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tullet JM, et al. Cell. 2008 Mar 21;132:1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McElwee JJ, et al. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R132. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broughton S, et al. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broughton SJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Feb 22;102:3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405775102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapahi P, et al. Curr Biol. 2004 May 25;14:885. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman T, Partridge L. Proc Biol Sci. 1996 Jun 22;263:755. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bass TM, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Oct;62:1071. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong R, Piper MD, Blanc E, Partridge L. Nat Methods. 2008 Mar;5:214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0308-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grandison RC, Piper MD, Partridge L. Nature. 2009 Dec 2; doi: 10.1038/nature08619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Libert S, et al. Scienc. 2007 Feb 23;315:1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1136610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannakou ME, Goss M, Partridge L. Aging Cell. 2008 Mar;7:187. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Min KJ, Yamamoto R, Buch S, Pankratz M, Tatar M. Aging Cell. 2008 Mar;7:199. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhandari P, Jones MA, Martin I, Grotewiel MS. Aging Cell. 2007 Oct;6:631. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burger JM, Hwangbo DS, Corby-Harris V, Promislow DE. Aging Cell. 2007 Feb;6:63. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartke A. Endocrinology. 2005 Sep;146:3718. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ladiges W, et al. Aging Cell. 2009 Aug;8:346. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan L, et al. Cell. 2007 Jul 27;130:247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jang YC, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009 Nov;64:1114. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enns LC, et al. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison DE, et al. Nature. 2009 Jul 16;460:392. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selman C, et al. Science. 2009 Oct 2;326:140. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson KJ, et al. Cell Metab. 2008 Aug;8:157. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikeno Y, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009 May;64:522. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia AM, et al. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008 Sep;129:528. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimokawa I, et al. J Gerontol. 1993 Jan;48:B27. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.1.b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearson KJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 19;105:2325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712162105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel NV, et al. Neurobiol Aging. 2005 Jul;26:995. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raffaghello L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jun 17;105:8215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reed MJ, et al. Mech Ageing Dev. 1996 Jul 31;89:21. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(96)01737-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kristan DM. Age (Dordr) 2008 Sep;30:147. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shevah O, Laron Z. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2007 Feb;17:54. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gourmelen M, Perin L, Binoux M. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1991;377:115. doi: 10.1111/apa.1991.80.s377.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliveira JL, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Dec;92:4664. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suh Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Mar 4;105:3438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bonafe M, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Jul;88:3299. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colman RJ, et al. Science. 2009 Jul 10;325:201. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Apr 27;101:6659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fontana L, Weiss EP, Villareal DT, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Aging Cell. 2008 Oct;7:681. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]