Abstract

Background

The importance of adverse reactions in terms of donor safety recently has received significant attention, but their role in subsequent donation behavior has not been thoroughly investigated.

Study Design and Methods

Six REDS-II blood centers provided data for this analysis. Summary minor and major adverse reaction categories were created. The influence of adverse reactions on donation was examined in two ways: Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were generated to determine the cumulative pattern of first return, and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for demographic and other factors positively and negatively associated with return were estimated using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Donors who had major reactions had longer times to return than donors with minor or no reactions. The AOR of returning for donors with major reactions was 0.32 (95% CI 0.28 – 0.37) and with minor reactions 0.59 (95% CI 0.56 – 0.62) when compared to donors who did not have reactions. Conversely, the most important factors positively associated with return were the number of donations in the previous year and increasing age. Subsequent return, whether a major, minor or no reaction occurred, varied by blood center. Factors that are associated with the risk of having adverse reactions were not substantial influences on the return following adverse reactions.

Conclusion

Having an adverse reaction leads to significantly lower odds of subsequent donation irrespective of previous donation history. Factors that have been associated with a greater risk of adverse reactions were not important positive or negative predictors of return following a reaction.

INTRODUCTION

The availability of the donated blood supply is dependent on members of the general population who choose to donate. Stability in the number of components available in the supply is largely attributable to repeat donation since nearly 72% of allogeneic donations are made by repeat donors in the United States.1 Previous studies have identified the factors associated with returning to donate blood, including the number of previous donations and specific demographic characteristics such as increasing age.2 One of the most potent predictors of return is a positive donation experience itself.3 In contrast to a positive donation experience, an adverse reaction to blood donation is a negative event known to impact subsequent blood donation.4 The epidemiology of donor adverse reactions has received significant attention in the last five years,5–8 and several studies have sought to quantify various aspects of impact of adverse reactions among other factors associated with returning to donate, focused on first-time donors 9 or the types of reactions experienced.4,10,11

We sought to expand the scope of previous studies to investigate the factors that are both positively and negatively associated with subsequent blood donation in both first-time and repeat donors. The study reported here extends previous findings by examining additional factors that may be associated with donor return following adverse events. A longitudinal research database consisting of all presenting blood donors at 6 US blood centers was analyzed to quantify the impact of minor and major reactions and other donor and donation characteristics on subsequent donation.

METHODS

The Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS-II) sites represent geographically and demographically diverse populations and collectively represent over 8% of annual blood collections in the United States. The REDS-II blood centers are: Blood Centers of the Pacific, in San Francisco, CA; BloodCenter of Wisconsin, in Milwaukee, WI; Hoxworth Blood Center, University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, OH; Institute for Transfusion Medicine, in Pittsburgh, PA; American Red Cross Blood Services, New England Region, in Dedham, MA; and American Red Cross Blood Services, Southern Region, in Atlanta, GA. These centers provided donation and deferral data that was processed into a common research database by the REDS-II Coordinating Center, Westat, Inc, Rockville, MD. Data collection was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the blood centers as well as the coordinating center.

Demographic characteristics(age, gender, race/ethnicity, blood type), donation procedure (whole blood, double red cell, and other apheresis collections including platelets or plasma apheresis with or without red cells) and other donation information (donation type, donation site, donation outcome, previous screening history) were collected on each blood donor by the REDS-II program continuously from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2009. Three of the REDS-II blood centers (Blood Centers of the Pacific, Hoxworth Blood Center, and Institute for Transfusion Medicine) collected additional research demographic information—such as height and weight—by incorporating these questions within the self-reported health history questions routinely asked to all blood donors. At the two American Red Cross blood centers and at the BloodCenter of Wisconsin the same research questions were administered to the donors via a supplemental questionnaire that was completed by the donors before or during the health history interview.

Additional variables not collected in the database were derived or calculated as necessary. Donations were classified as first-time or repeat based on the previous screening history. A presentation to donate was determined to be repeat presentation if the blood center had a blood unit number and infectious marker screening results from a previous donation by the same donor. If no previous screening test information was reported in the blood center’s database, the donation was classified as first-time. Previous red cell donation history was also considered as a factor for returning after an adverse reaction. Donor visits were categorized as single or double red cell donations depending on the type of product given (whole blood and apheresis collection with a single red cell component, or double red blood cell collections). Donations of whole blood and apheresis red blood cells were grouped together to calculate the number of red cell containing donations in the previous 12 months with double red blood cells donations counted as one red cell donation. Non-red cell-containing donations included plateletpheresis with or without concurrent plasma collection. The number of red cell and non-red cell donations given within the previous 12 months was calculated for each donation visit. Finally, estimated blood volume (EBV) was calculated using self-reported weight, height, and gender according to the formula of Nadler and colleagues12 and divided into five categories (<3.5, 3.5 to <4.0, 4.0 to <4.5, 4.5 to <5.0, and ≥5.0 L).

There were no major changes in donor eligibility criteria during the study period except for the implementation of a requirement for donors ages 16–19 year old to have an estimated blood volume of ≥3.5L since September 1, 2009 at blood centers C and F and a similar requirement for donors ages 16-to 22 years old at blood center B since July 28, 2008.

Donor Reaction Classification

The reaction classification approaches used by the 6 REDS-II centers were not identical. We created summary categories by grouping reactions together into either minor or major reactions (Table 1). We defined three groups for analysis: (a) donors with minor reactions such as dizziness, hyperventilation, pallor, bruising, etc.; (b) donors with major reactions such as any loss of consciousness for 60 seconds or greater or with complications, and more severe needle-related injuries such as arterial puncture or nerve irritation; and (c) donors who did not have reactions on an index whole blood donation in 2007. Some REDS-II centers consider any loss of consciousness as sufficient to classify a reaction as severe, making such reactions major for the purpose of our analysis. However, the majority of centers included in this analysis required loss of consciousness to be 60 seconds or greater or with complications to be classified as a severe reaction. The donation reaction definitions used at each center did not change during the study period.

Table 1.

Reaction classification use in the study of donor return following reaction by REDS-II blood centers during the time period, 2007–2009, and specific codes used by each center.

| REDS-II Blood Center | Study Classification | Blood Center Reactions Classification Codes | Detailed classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Minor | Mild/Moderate | Lightheaded, dizziness, restless, pallor, sighing, perspiration, tingling, queasiness, numbness, sensation, vomiting, hyperventilation |

| Major | Severe | Loss conscious, convulsion, rigidity, cardiac | |

| B | Minor | Mild Moderate | Pre Faint (no loss of consciousness) |

| Loss of consciousness (any duration, uncomplicated) | |||

| Major | Severe | Loss of consciousness (any duration, complicated) | |

| C and F | Minor | Allergic, Minor Reaction | |

| Citrate, Minor Reaction | |||

| Pre-Faint | |||

| Loss of Consciousness, Short (less than 1 minute) | |||

| Hematoma, Small (2 × 2 inches or less) | |||

| Other, Minor Reaction | |||

| Major | Allergic, Major Reaction | ||

| Citrate, Major Reaction | |||

| Loss of Consciousness, Long (1 minute or more) | |||

| Hematoma, Large (more than 2 × 2 inches) | |||

| Loss of Consciousness with Injury | |||

| Nerve Irritation | |||

| Other, Major Reaction | |||

| Prolonged Recovery (approximately 30 minutes or greater) | |||

| Arterial Puncture | |||

| D | Minor | Type I (Mild) | A feeling of warmth, pallor, perspiration(especially on forehead, upper lip, palms), dizziness or lightheadedness, sighing or yawning, hyperventilation without other signs or symptoms, nausea without vomiting |

| Type II (Moderate) | Progression of any or all symptoms of a slight reaction, bradycardia (slow pulse; less than 50 bpm), shallow respirations, anxiety, vomiting | ||

| Major | Type III (Severe) | Any or all symptoms of a moderate reaction, hyperventilation with neuromuscular excitability, variable color (from pale to cyanotic), incontinence of urine, fainting, convulsive movements, true convulsions | |

| E | Minor | Type I (Mild) | Weakness, dizziness, paleness, diaphoresis (extreme perspiration), nausea, hyperventilation |

| Type II (Moderate) | Vomiting without gross blood, brief period of unconsciousness (<60 seconds), mild tetany (muscle contractions) | ||

| Major | Type III (Severe) | Unconsciousness/unresponsiveness (>60 seconds), diaphoresis (extreme perspiration), convulsions, tetany, involuntary bowel or urine passage, multiple episodes of vomiting, tachycardia (>150 beats per minute), sustained bradycardia (<50 beats per minute) |

Data Analysis

Although the focus of the analysis was the time period of 2007 – 2009, information from all four years of data collection (2006–2009) was used in this analysis. In order to predict the probability of return, whole blood allogeneic donation visits made in 2007 were identified as “index donations”. Data from 2006 provided information on the number of red cell containing and non-red cell donations within the previous 12 months. For the date of return, donors were followed forward at least two years since the index presentation. Any return to the blood center was included in the analysis regardless of whether the subsequent visit led to a successful donation of any type or deferral. Return visits up to December 31, 2009 were considered. All donors who did not return were censored on this date. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were generated to determine the time to first return and cumulative pattern of first return based on the three reaction categories (no reaction, minor reaction and major reaction). Unadjusted KM curves were developed for each blood center.

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for demographic and other factors known to be associated with return within a fixed time period following the index presentation were estimated using multivariable logistic regression (since the regression is based on 665,501 index donations, all main effect covariates were expected to be and were statistically significant at the p<0.0001 level). A fixed two-year period was used in order to ensure equivalent follow-up time for every donor. As with the KM analysis, any return to the blood center was included in the analysis. Adjusted ORs for the likelihood of returning were estimated for each factor relative to a reference group. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) that did not include a value of 1.0 for each OR were considered evidence of statistically significant differences between the levels of each explanatory variable. Interactions between having a reaction and demographic factors (age, gender, estimated blood volume, and donation history) were examined to assess whether any of these factors are associated with return following an adverse reaction. Interactions between having a reaction and blood center were also evaluated. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

During the period from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2007, there were a total of 665,501 index donation attempts by unique donors to the REDS-II blood centers. Out of these donations, 26,980 donors experienced reactions with 2,096 (0.3%) of all donors experiencing major reactions and 24,884 (3.7%) experiencing minor reactions (Table 2). Overall, 92% of reactions were classified as minor, leaving only a small proportion (8%) classified as major reactions. The frequency of major and minor reactions varied by center, with centers having large differences in major reactions (as great as 30-fold) and also minor reactions (over 4-fold).

Table 2.

Number of unique donors with major, minor, or no reactions on their index donation at each REDS-II center during the calendar year 2007.

| Blood Center | Major Reaction | Minor Reaction | No Reaction | Total Number of Index Donation Visits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| A | 374 | 0.42 | 4,884 | 5.45 | 84,417 | 94.14 | 89,675 |

| B | 367 | 0.62 | 1,223 | 2.05 | 57,978 | 97.33 | 59,568 |

| C | 309 | 0.18 | 6,960 | 3.96 | 168,453 | 95.86 | 175,722 |

| D | 81 | 0.02 | 580 | 1.25 | 45,628 | 98.57 | 46,289 |

| E | 295 | 0.39 | 1,037 | 1.38 | 73,792 | 98.23 | 75,124 |

| F | 670 | 0.31 | 10,200 | 4.65 | 208,253 | 95.04 | 219,123 |

| Total | 2,096 | 0.31 | 24,884 | 3.74 | 638,521 | 95.95 | 665,501 |

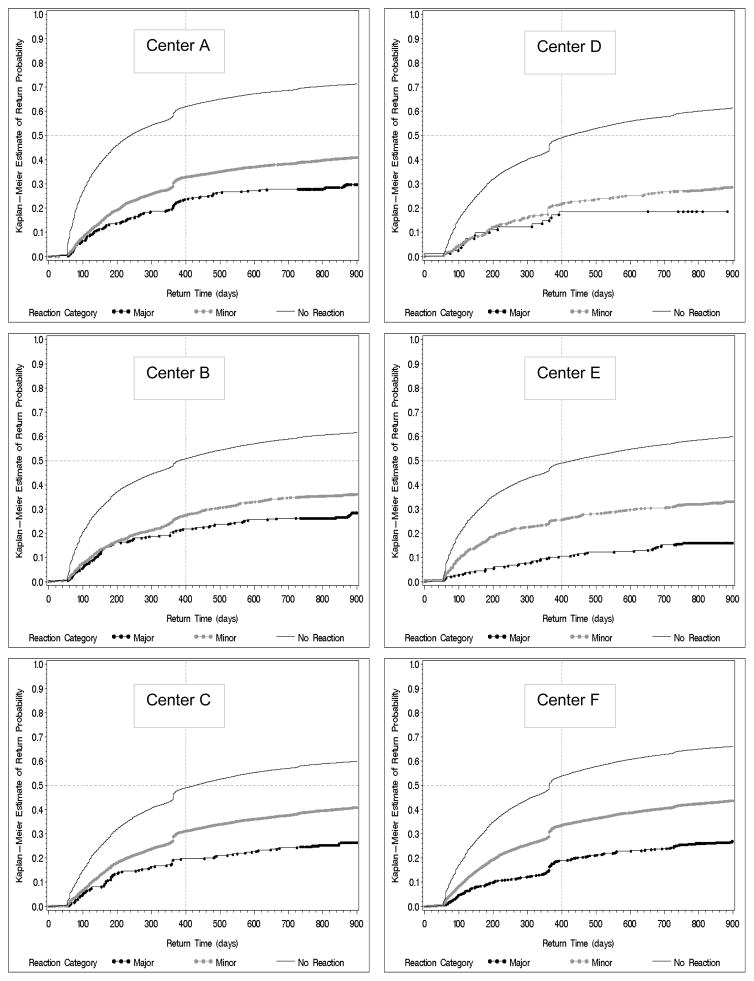

The severity of reaction is closely related to the likelihood of returning to try to donate again. Regardless of center, donors who experienced major reactions were less likely to return and had longer times to return than donors with minor reactions or donors who did not have reactions (Figure 1). Whether minor or major, a median return time for donors who had reactions could not be calculated because less than 50% of donors who had reactions returned during the follow-up period. No REDS-II center had more than 30% of persons with major reactions returning. Similarly for persons with minor reactions no more than 45% returned during follow-up. For donors without reactions, 60 to 70% returned during follow-up depending on the center. While the return curves showed a consistent relationship in terms of the number of donors returning according to the reaction category, differences between the centers were evident. Overall, Centers A and F had similar return patterns and proportions, whereas return for Center D was much lower for both minor and major reactions. Within the context of the set of factors that influence return to the blood center, multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the AOR of returning for donors with major reactions was 0.32 (95% CI 0.28 – 0.37) and for donors with minor reactions was 0.59 (95% CI 0.56 – 0.62) and when compared to donors who did not have reactions (Table 3). Other factors that were negatively associated with return include race/ethnicity other than white, donation sites other than fixed locations, and incomplete collections. In addition, the blood center itself was important with Centers D and E having significantly lower odds of donors returning compared to Center F. Low estimated blood volume (≤3.5L) was associated with significantly lower odds of return compared to donors with estimated blood volumes of 5 liters or more, but the overall effect was only a 10% reduction in the odds of returning.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan Meier time to first return curves for each REDS-II blood center (Centers A – F) showing the impact of minor (gray circles) and major reactions (black circles) on the time to return and cumulative number of donors returning compared to donors who did not have reactions. Dashed horizontal line represents the median return time and the dashed horizontal line show return proportions at 400 days following index donation.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis results of factors associated with return following adverse reactions in blood donors to REDS-II blood centers during the time period of 2007–2009. Logistic regression model includes all of the listed variables.

| Variable | Category | Adjusted ORs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction | Major | 0.32 (0.28–0.37) |

| Minor | 0.59 (0.56–0.62) | |

| No Reaction | 1.0 | |

| Blood Center | A | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) |

| B | 0.89 (0.79–1.00) | |

| C | 0.92 (0.82–1.03) | |

| D | 0.62 (0.50–0.78) | |

| E | 0.54 (0.47–0.61) | |

| F | 1.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) |

| Female | 1.0 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 1.0 |

| Asian | 0.85 (0.82–0.88) | |

| Black | 0.70 (0.68–0.71) | |

| Hispanic | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | |

| Other | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | |

| Age (in years) | 16–22yrs | 1.0 |

| 23–35 | 1.16 (1.14–1.18) | |

| 36–45 | 1.63 (1.60–1.66) | |

| 46–55 | 2.03 (1.99–2.07) | |

| 56–65 | 2.16 (2.11–2.21) | |

| 66+ | 1.99 (1.93–2.05) | |

| Donor Status | First-time | 1.0 |

| Repeat | 1.20 (1.18–1.22) | |

| Number of Red Cell Containing Donations in Last Year | 0 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 1.69 (1.67–1.72) | |

| 2 | 3.07 (3.01–3.13) | |

| 3 | 5.25 (5.09–5.41) | |

| 4 | 8.51 (8.08–8.97) | |

| 5 | 14.18 (12.97 – 15.51) | |

| Number of Donations of non-Red Cell components in the Last Year | 0 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 1.84 (1.67–2.02) | |

| 2 | 2.86 (2.36–3.46) | |

| 3 | 4.00 (2.93–5.46) | |

| 4 | 10.51 (6.01–18.37) | |

| 5 or more | 9.44 (6.83–13.03) | |

| Donation Site | Fixed | 1.0 |

| High School | 0.74 (0.73–0.76) | |

| College | 0.68 (0.67–0.70) | |

| Other Mobile | 0.71 (0.70–0.72) | |

| Outcome | Completed donation | 1.0 |

| Incomplete | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | |

| Other | 0.88 (0.85–0.90) | |

| EBV | ≤ 3.5 | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

| 3.5 ≤ 4 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |

| 4 ≤ 4.5 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | |

| 4.5 ≤ 5 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | |

| 5+ | 1.0 | |

| ABO/Rh | A+ | 0.92 (0.91–0.94) |

| A− | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | |

| AB+ | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | |

| AB− | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | |

| B+ | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | |

| B− | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | |

| O+ | 1.0 | |

| O− | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) |

On the other hand, factors positively associated with return were the number of previous donations and increasing age. Donors who gave red cell containing donations three times in the previous year were 5.3 times (95% CI, 5.1 – 5.4) more likely to return compared to donors with no red cell containing donation in the previous year. Four or five red cell containing donations lead to even higher odds ratios for return, AOR = 8.5 (95% CI 8.14 – 9.0) and AOR = 14.2 (95%CI 13.0 – 15.5), respectively. Results for donations of other components were similar with donors who gave 4 non red cell containing donations the most likely to return AOR = 10.5 (95%CI 6.0 – 18.4), with 5 or more non red cell containing donations closely following AOR = 9.4 (95%CI 6.8 – 13.0). Increasing age was also associated with increased likelihood of return with donors over 45 years old 2 times more likely to return than donors 16–22 years old. Donor blood type had a minor effect on return rate.

We examined interactions between reaction categories and several variables associated with syncopal reactions to determine if donors at higher risk for syncopal reactions were even less likely to return to donate blood following a reaction. Results after inclusion of interactions in the multivariable logistic regression models between adverse reactions and donor characteristics were with one exception not significant or marginally significant: age interaction (p>0.05), donor status interaction (p>0.05), gender interaction (p=0.02), estimated blood volume interaction (p=0.02), and center interaction (p<0.0001). The marginally significant interaction factors associated with return behavior after a donation with a minor or major reaction are substantively the same as associations for subsequent donations after an index donation without reaction (data not shown), hence deemed clinically not significant.

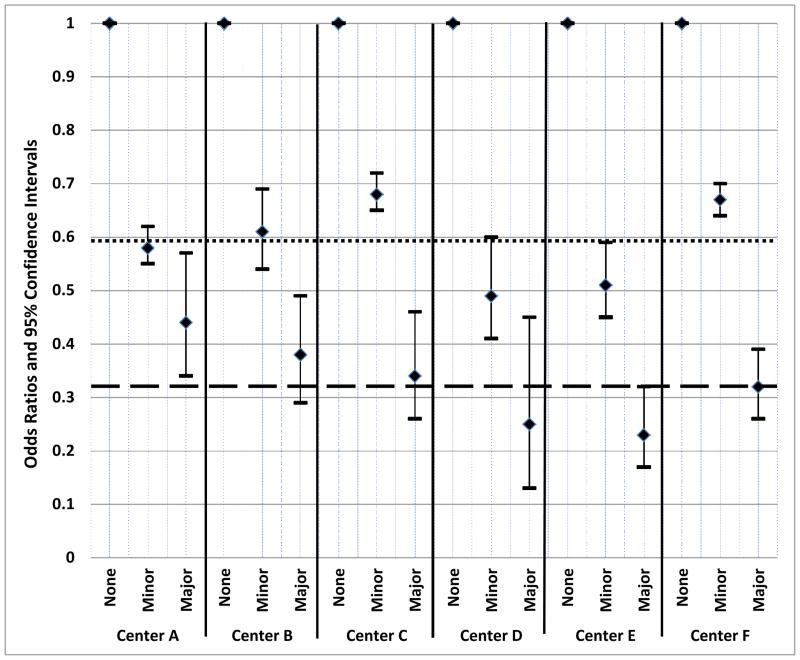

The most important interaction we identified was the blood center interaction. The Kaplan Meier curves showed different return patterns by center, and the overall multivariable logistic regression results showed that blood center was an important factor associated with donor return. To further investigate the influence of blood center on return following adverse reaction, we examined the odds of returning following minor or major reactions by center to assess the differential adverse reaction effect by center (i.e. the adverse reaction by center interaction). The odds ratios and associated confidence intervals for minor or major reactions compared to no reaction by center are displayed graphically (Figure 2). Only one center (A) has a major reaction effect differing from the average major reaction effect across all centers (AOR=0.32, as shown in Table 3) as evidenced by its confidence interval not overlapping the value 0.32. Two centers (C and F) have minor reaction effects differing from the average minor reaction effect (AOR=0.59).

Figure 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis results for minor and major reactions at each REDS-II blood center during the time period of 2007–2009. Donors who did not have reactions are the reference group within each center. Logistic regression model includes gender, race/ethnicity, age, donor status, number of red cell donations in last year, number of non-red cell donations in last year, donation site, successful collection, estimated blood volume and donor blood type as covariates in the model. The horizontal dashed line represents the overall adjusted odds ratio for major reactions (AOR=0.32) across all centers and the horizontal dotted line represents the overall adjusted odds ratio for minor reactions across all centers (AOR=0.59).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the impact of adverse reactions and other factors on subsequent blood donation visits. Having a minor adverse reaction led to significantly lower odds of subsequent visit, with major reactions leading to even lower odds of return. Factors that have been associated with substantially increased risk of adverse reactions, such as gender, donation history, estimated blood volume, and younger age, were not the most important positive or negative predictors of return following a reaction. As intuitively expected, the number of previous donations was the most important predictor positively associated with subsequent visits. Likewise, increasing age was positively associated with subsequent visits.

Our overall results for the REDS-II centers are remarkably similar to the system-wide results reported for the American Red Cross. Notari and colleagues reported that the odds of return following minor reactions in first-time donors was 0.64, and for major reactions was 0.33.9 A similar analysis focused on young donors (16–19 years of age) found that any donation complication led to decreased odds of return of 0.40 in 16 year olds.5 In our multivariable analysis we were able to include many additional predictors of return such as donation site, procedure outcome, and number of prior donations in the last 12 months. However, while these are important predictors of return, they do not appear to be confounders of the relationship between having a reaction and subsequent blood donation because of the similarity in the odds ratios we and the ARC investigators have reported. Of note, two of the centers in REDS-II are ARC centers. These two centers contributed approximately 60% of the data included in our analysis and approximately 7% of the included in the previous analysis by Notari and colleagues.

Part of the reason for investigating the role of adverse reactions in donor return was to examine whether the known risk factors for adverse reactions are associated with return following adverse reactions. Although gender, race/ethnicity, estimated blood volume and donation history have been associated with syncopal reactions, return following adverse reaction is not substantially associated with these characteristics. While we documented a significant negative association for return after a reaction among donors with estimated blood volumes of <3.5L relative to donors with EBV ≥5L, the magnitude of the effect was modest. Thus while EBV of <3.5L appears to be one of the most important risk factors for reaction, lower EBV is only a minor contributor in the list of factors positively or negatively associated with return.

This analysis has limitations. The most notable limitation is the classification of specific types of reactions into the broad categories of minor and major reactions. The vast majority of minor reactions are nonsyncopal reactions. In contrast, very high proportions of major reactions include syncope or are prolonged-recovery vasovagal reactions.6,13 Because centers do not use identical coding schemes, some of the results, particularly when considering center to center differences, may be a result of the reaction classifications. For example, Center A considers any loss of conscious as sufficient to be a major reaction. This classification of any loss of consciousness likely contributes to the overlapping confidence intervals for the AORs and the lack of significant difference in the odds of returning by minor or major reaction categories at this center, and may explain why this center was the only one to have a significantly higher rate of return for persons experiencing major reactions compared to the combined effect observed for all centers.

Adoption of uniform coding schemes for adverse reactions across blood collection would improve the ability to synthesize data from different centers. However, even when the coding system is the same, such as within a single blood collection organization, differences in the rates of reactions and the severity of reactions are evident according to center.5,6 As has been previously discussed in an Editorial in Transfusion, “this phenomenon is due to a combination of inconsistent definitions of what constitutes a reaction; different reporting criteria across agencies; and variability in how individual phlebotomists interpret, recognize, and report adverse events.”14 The reasons why reaction rates and severity classifications can be as variable as they are merits further study.

Another limitation of the study is that we did not account for potential center-specific preferential recruitment practices focused on converting selected whole blood donors to component donations such as apheresis platelets and plasma or double red cell collections. These recruitment strategies could lead to increased return. Furthermore it is possible that donors who experienced reactions and were recruited for apheresis donation were more inclined to return to donate than whole blood donors who experienced reactions, but were re-recruited for whole blood donation.

Our data regarding the return behavior is applicable to the reactions seen with whole blood donation but not with automated collection methods. The epidemiology of adverse reactions for automated collection procedures is different than for whole blood donations15,16 therefore return behavior following reactions by automated collections methods may be different.

A further limitation with regard to reactions included in this analysis is that we were unable to separate out needle-related injuries from vasovagal reactions because of the way data were provided to the study coordinating center. Interestingly, while needle-related injuries are less common than vasovagal reactions (0.7 injuries per 10,000 whole blood donations compared to >258 per 10,000 donations)17 and so the majority of reactions included in this analysis are systemic rather than local in etiology, interview studies of donors show that needle-related injuries are far more likely to be reported but do not impact donor return to nearly the same degree as systemic reactions.4 Nonetheless, our analysis combines both types of adverse events together to report on the overall impact of adverse reactions during the blood collection process. It is possible that the results would be different if we were able to independently look at factors associated with return in donors with needle-related and vasovagal adverse events.

In addition, certain types of reactions may lead to indefinite deferral at some centers. In particular, severe reactions including those where an injury has occurred or with specific signs or symptoms such as chest pain may lead blood centers to request that donors who experience such reactions not try to donate again. In this regard, the medical policy and counseling at individual centers may be variable. In our analysis, all donors were assumed to potentially be eligible to donate again because we could not identify the specific reactions where donors were informed they were no longer eligible to donate. However, because the most severe types of reactions are the least common, it is unlikely the analysis is substantially biased by the inclusion of these reactions in the data. Moreover, the Kaplan Meier curves establish that a substantial proportion of donors who experience major reactions are still willing to present to donate again.

While identifying risk factors for adverse reactions and introducing interventions to reduce their occurrence are predominantly focused on donor safety, the occurrence of reactions does lead to reduced blood donation. It is natural to extend the focus of this analysis to the question of how many potential donations were lost from the blood supply because of the occurrence of adverse reactions. Among the 665,501 index donations given by unique donors, we observed 2096 major reactions, 24,884 minor reactions, and 638,521 presentations without reactions, with 402,374 donors returning within 2 years (60.5% return rate). Using the regression model, we projected had there been no adverse reactions among the 665,501 index donations (donors) we would have observed 406,190 donors returning within 2 years (61.0% return rate). Translating these 2 year return rates into annual donation rates, we project had there been no adverse reactions there would have been 1.6% additional donations obtained per year.

The broader effort currently underway at blood centers to reduce the risk of adverse reactions by deferring potential young donors who have EBV ≤3.5L, and through the adoption of interventions such as providing water before donation and encouraging muscle exercises13,18 are likely to change the composition of the blood donor pool and pre-donation donor preparation. These changes in turn may change the factors associated with returning to donate. However, these changes would not be expected to modify the consequences of adverse reactions on subsequent donation.

In this study, we confirmed that adverse reactions lead to reduced future blood donation using a large multicenter database. Both minor and major adverse reactions reduce the likelihood of future return. Adverse reactions are only one factor associated with return. There are many characteristics of donors and previous donation history that are either positively or negatively associated with return. These patterns were evident across the REDS-II centers. Adoption of uniform approaches for coding adverse reactions would make center to center comparisons easier to achieve. Yet, different recruitment patterns and secondarily donor care may contribute to different blood donor return rates. The representativeness of our results of the impact of adverse reactions and other factors on subsequent donation at centers outside of REDS-II likely can be assumed to hold because of the diverse representation of participating blood centers and in particular the different adverse reaction classification approaches used by the REDS-II centers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI contracts N01-HB-47168, -47169, -47170, -47171, -47172, -47174, -47175, and -57181

The authors thank the staff at the REDS-II blood centers. Without their help, this study would not have been possible.

ABBREVIATIONS

- REDS-II

Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study-II

- A.O.R

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Interval

The Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS) - II is presently the responsibility of the following persons:

Blood Centers

American Red Cross Blood Services, New England Region

R. Cable, J. A. Rios, R. J. Benjamín

American Red Cross Blood Services, Southern Region/Emory University

J.D. Roback

BloodCenter of Wisconsin

J. L. Gottschall, A. E. Mast

Hoxworth Blood Center, University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center

R.A. Sacher, S.L. Wilkinson, P.M. Carey

Regents of the University of California/Blood Centers of the Pacific/BSRI

E.L. Murphy, M.P. Busch, B. Custer

The Institute for Transfusion Medicine (ITxM)/LifeSource Blood Services

D. J. Triulzi, R. M. Kakaiya, J. Kiss

Central Laboratory

Blood Systems Research Institute

M.P. Busch, P.J. Norris

Coordinating Center

Westat, Inc.

J Schulman, M.R. King, D.J. Wright, T.L. Simon, S.H. Kleinman, P.M. Ness

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH

S. Glynn, T.H. Mondoro

Steering Committee Chairman

R.Y. Dodd

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Brian Custer: None

Jorge Rios: None

Karen Schlumpf: None

Ram Kakaiya: None

Jerome Gottschall: None

David Wright: None

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Brian Custer, Blood Systems Research Institute, and UCSF, San Francisco, CA

Jorge A. Rios, New England Region, American Red Cross Blood Services, Dedham, MA

Karen Schlumpf, Westat, Rockville, MD

Ram M. Kakaiya, Lifesource/Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Chicago, IL

Jerome L. Gottschall, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

David J. Wright, Westat, Rockville, MD

References

- 1.Whitaker BI, Green J, King MR, et al. The 2007 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey. Rockville, Maryland: The United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlumpf KS, Glynn SA, Schreiber GB, et al. Factors influencing donor return. Transfusion. 2008;48:264–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Germain M, Glynn SA, Schreiber GB, et al. Determinants of return behavior: a comparison of current and lapsed donors. Transfusion. 2007;47:1862–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman BH, Newman DT, Ahmad R, Roth AJ. The effect of whole-blood donor adverse events on blood donor return rates. Transfusion. 2006;46:1374–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eder AF, Hillyer CD, Dy BA, et al. Adverse reactions to allogeneic whole blood donation by 16-and 17-year-olds. Jama. 2008;299:2279–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamel H, Tomasulo P, Bravo M, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to blood donation. Transfusion. 2010;50:556–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiltbank TB, Giordano GF, Kamel H, et al. Faint and prefaint reactions in whole-blood donors: an analysis of predonation measurements and their predictive value. Transfusion. 2008;48:1799–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rios JA, Fang J, Tu Y, et al. The potential impact of selective donor deferrals based on estimated blood volume on vasovagal reactions and donor deferral rates. Transfusion. 2010;50:1265–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notari EPt, Zou S, Fang CT, et al. Age-related donor return patterns among first-time blood donors in the United States. Transfusion. 2009;49:2229–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.France CR, France JL, Roussos M, Ditto B. Mild reactions to blood donation predict a decreased likelihood of donor return. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;30:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.France CR, Rader A, Carlson B. Donors who react may not come back: analysis of repeat donation as a function of phlebotomist ratings of vasovagal reactions. Transfus Apher Sci. 2005;33:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadler SBHJ, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery. 1962:51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomasulo P, Kamel H, Bravo M, et al. Interventions to reduce the vasovagal reaction rate in young whole blood donors. Transfusion. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03074.x. (Early Online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.France CR, Menitove JE. Mitigating adverse reactions in youthful donors. Transfusion. 2008;48:1774–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin RJ, Dy BA, Kennedy JM, et al. The relative safety of automated two-unit red blood cell procedures and manual whole-blood collection in young donors. Transfusion. 2009;49:1874–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan S, Ziman A, Smeltzer B, et al. Moderate and severe adverse events associated with apheresis donations: incidences and risk factors. Transfusion. 2010;50:478–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eder AF, Dy BA, Kennedy JM, et al. The American Red Cross donor hemovigilance program: complications of blood donation reported in 2006. Transfusion. 2008;48:1809–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman B, Tommolino E, Andreozzi C, et al. The effect of a 473-mL (16-oz) water drink on vasovagal donor reaction rates in high-school students. Transfusion. 2007;47:1524–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]