Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that mitochondria are locally coupled to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ release in myoblasts and to sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release in differentiated muscle fibers in order to regulate cytoplasmic calcium dynamics and match metabolism with cell activity. However, the mechanism of the developmental transition from ER to SR coupling remains unclear. We have studied mitochondrial sensing of IP3 receptor (IP3R)- and ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated Ca2+ signals in H9c2 myoblasts and differentiating myotubes, as well as the attendant changes in mitochondrial morphology. Mitochondria in myoblasts were largely elongated, luminally-connected and relatively few in number, whereas the myotubes were densely packed with globular mitochondria that displayed limited luminal continuity. Vasopressin, an IP3-linked agonist, evoked a large cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) increase in myoblasts, whereas it elicited a smaller response in myotubes. Conversely, RyR-mediated Ca2+ release induced by caffeine, was not observed in myoblasts, but triggered a large [Ca2+]c signal in myotubes. Both the IP3R and the RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c rise was closely associated with a mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m) signal. Every myotube that showed a [Ca2+]c spike also displayed a [Ca2+]m response. Addition of IP3 to permeabilized myoblasts and caffeine to permeabilized myotubes also resulted in a rapid [Ca2+]m rise, indicating that Ca2+ was delivered via local coupling of the ER/SR and mitochondria. Thus, as RyRs are expressed during muscle differentiation, the local connection between RyR and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites also appears. When RyR1 was exogenously introduced to myoblasts by overexpression, the [Ca2+]m signal appeared together with the [Ca2+]c signal, however the mitochondrial morphology remained unchanged. Thus, RyR expression alone is sufficient to induce the steps essential for their alignment with mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake sites, whereas the mitochondrial proliferation and reshaping utilize either downstream or alternative pathways.

Keywords: calcium signaling, mitochondria, sarcoplasmic reticulum, ryanodine receptor, development, mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM)

Introduction

Evidence for close associations and physical coupling between ER and mitochondria was first presented many years ago [1, 2]. The physiological relevance of the ER-mitochondrial associations first became apparent in the biosynthesis of phospholipids and in calcium signaling [2, 3]. A recent direction of these studies focused on the structural basis of the ER-mitochondrial interactions and identified proteinous tethers of various length between the ER membrane and outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) [4], which are likely to be composed of several proteins, including Mfn2 [5], the ERMES complex [6], an IP3R-chaperone-VDAC complex [7, 8], AMFR [9], and PACS-2 [10]. Another direction of the studies uncovered numerous new functions of the ER-mitochondrial interface, such as regulation of stress signaling and cell survival [11] and mitochondrial fission [12].

In the context of calcium signaling, the major role of the ER/SR-mitochondrial associations is to facilitate the propagation of IP3R and RyR-mediated Ca2+ release to the mitochondria. The mitochondrial handling of the ER/SR-derived Ca2+ exerts important feedback effects on cytoplasmic calcium signaling and results in [Ca2+]m rises that stimulate oxidative metabolism through the activation of the Ca2+-sensitive matrix dehydrogenases to meet the energy needs of the stimulated cells. A role for the ER/SR-mitochondrial interface in the propagation of the IP3R or RyR-mediated Ca2+ release to the mitochondria was first speculated because of the discrepancy between the low affinity of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and the large [Ca2+]m increases that occur during Ca2+ release-induced elevations of the bulk [Ca2+]c to <1μM [3, 13-15]. Strategically positioned close to the IP3R/RyR-mediated Ca2+ release, subdomains of the mitochondrial surface can be exposed to >10-fold higher local [Ca2+]c increase than the rise in global [Ca2+]c. This point has been directly proven very recently by Ca2+ sensors targeted to the mitochondrial side of the ER/SR mitochondrial interface [16, 17].

The SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer is particularly important in skeletal and cardiac muscle, where energy production must meet the large and continually changing demands of the contractions. The presence of close SR-mitochondrial associations secured by tethers is supported by beautiful ultrastructural studies [18-22]. Local SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer has also been documented in both cardiac myocytes and skeletal myotubes and muscle fibers [23-30]. An important puzzle remains the mechanism of the development of the SR-mitochondrial coupling during muscle differentiation. In myoblasts, the progenitor cells, mitochondria are locally coupled to IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER and RyRs are expressed at very low levels [31-33]. During differentiation RyR1 and RyR2 expression greatly increases in skeletal and cardiac muscle, respectively, which is critical for the excitation-contraction coupling [33-36]. This is likely to be parallelled the development of the excitation-oxidative metabolism coupling. At the same time, the IP3Rs take on different roles like regulating gene transcription, and regulating hypertrophy [37-40]. Here, we have studied the restructuring of mitochondria during myoblast differentiation and evaluated the role of RyR1 expression in the reorganization of the ER/SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling. We used H9c2 myoblasts that can be differentiated to myotubes under well controlled culture conditions and have been shown to display robust ER/SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer [32, 41-43].

Methods

Cell culture and transfections

H9c2 cells (obtained from ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were cultured and differentiated as described earlier [32]. For imaging experiments, cells were plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips and 2-4 days after plating were transfected with ratiometric organelle-targeted pericams (gifts from Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki) [44], or RyR1 (gift from Dr. Jianjie Ma) [45] using LipofectAmine (Invitrogen). Cells were observed 24-36 h after transfection.

Fluorescence Imaging of [Ca2+]

To measure [Ca2+]c in intact cells the cells were preincubated for 25 min in an extracellular medium (ECM) consisting of 121 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM Na-HEPES, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, pH7.4 and supplemented with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA).

For permeabilized cell experiments the cells were washed four times with a Ca2+-free ECM, and then permeabilized with 25-40 μg/ml digitonin for 7 min in an intracellular medium (ICM) composed of 120 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.2, supplemented with 2 mM MgATP, 10 μM EGTA/Tris, and 1 μg/ml each of antipain, leupeptin, pepstatin. The cells were washed 3 times with the same buffer without digitonin prior to imaging.

Intact cell and permeabilized cell fluorescence measurements were carried out in 0.25% BSA-ECM, and in ICM containing ∼300 nM [Ca2+] after adding 2 mM MgATP, 2 mM succinate, and protease inhibitors at 35°C.

Fluorescence imaging was carried out using an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope (40×, UApo340) fitted with a cooled CCD camera (Pluto, Pixelvision) and a high speed wavelength switcher (Lambda DG, Sutter Instruments) under computer control [46]. Pericam was excited at 415 and 495 nm. The data acquisition rate was 0.5 duplet/s.

Confocal imaging of mitochondrial morphology and dynamics

Cells were loaded with 200 nM MitoTracker Green (Molecular Probes) for 20 min in (2% BSA-ECM) at room temperature. To reduce movement of the mitochondria, cells were treated with 10 μM Nocodazole for 80-140 min. Experiments were performed in (0.25% BSA-ECM) at 35°C as a standard condition and at 23°C with 10 μM Nocodazole for the movement reducing condition. A BioRad Radiance 2100 confocal laser scanning system coupled to an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope with a 40×, NA 1.35 oil-immersion objective was used to record image series. The 488nm line of a Kr/Ar laser was used to excite the MitoTracker Green. Images were taken continuously at 512×512 resolution at a high digital zoom (0.1 μm/pixel) with a frame rate of 0.3 Hz. Two 64μm2 (80×80 pixels) regions containing stained mitochondria were selected for bleaching. Two images were recorded prebleach, followed by three bleaching images (or one for the 1-scan FLIP experiments) with the selected regions illuminated at 16.7 times the normal scanning intensity. For FRAP experiments the cell was scanned continuously for 5.5 min after bleaching; for FLIP only the scan immediately after bleaching is relevant. FRAP experiments were analyzed by normalizing the mean fluorescence values of the bleach regions first by their initial values (average of the two prebleach scans) and then by the normalized fluorescence of the entire cell (or as much of it as is in the field) throughout the run. The whole-cell normalization corrects for the continued photobleaching during the recovery period and for any drift in the focal plane. Finally, the data was normalized for the extent of bleaching yielding a percentage recovery curve. For FLIP the mean fluorescence of the box extending 2μm on each side outside the bleach spot (total area 80μm2) was measured. The relevant quantity (FLIP) is the ratio of the percentage loss of fluorescence of the FLIP area to that of the bleach spot measured at the scan immediately following the bleaching.

Statistics

Experiments were carried out with at least three different cell preparations. Traces represent single cell responses unless indicated otherwise. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. Significance of differences from the relevant controls was calculated by Student's t test.

Results

Restructuring of mitochondria during differentiation of H9c2 myoblasts

We have previously shown that H9c2 cells grown to confluency, upregulate expression of L type Ca2+ channels and RyRs and gradually convert to multinucleated myotubes [32]. We also demonstrated that in the myotubes, RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c oscillations are effectively propagated to the mitochondria utilizing local Ca2+ communication between SR and mitochondria [32, 42, 47]. To study how the SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling is established during differentiation in H9c2 myoblasts, we first evaluated mitochondrial morphology in both myoblasts and myotubes.

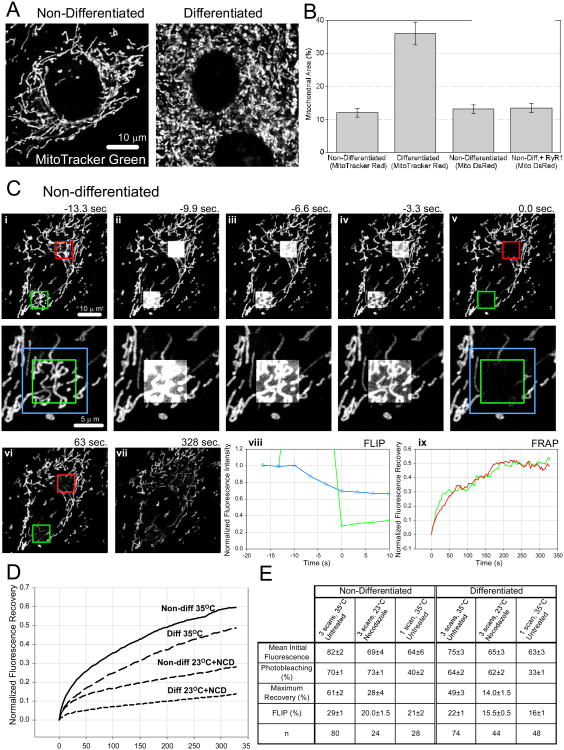

MitoTracker loading revealed mostly tubular mitochondria in myoblasts and mostly globular mitochondria in myotubes (Fig1A). The fraction of cellular cross-sectional area occupied by MitoTracker positive structure was almost 3-fold larger in the myotubes than in myoblasts (Fig1B). The connectivity and dynamics of the mitochondria were evaluated by region-of-interest photobleaching of MitoTracker and measurement of the concurrent loss of fluorescence in the adjacent region (FLIP) and the subsequent recovery of fluorescence in the photobleached area (FRAP). In order to separate the FRAP/FLIP due to instantaneous matrix continuity of the mitochondria from that caused by motility and fusion, the photobleaching experiments were also performed at lower (room) temperature and in the presence of the microtubule depolymerizing drug, nocodazole, thereby depriving the cells of the energy and cytoskeletal support essential for both motility and fusion. Myotubes showed decreased FLIP and FRAP relative to the myoblasts in both control and motility reducing conditions (Fig1DE). Collectively, these results indicate that the fraction of the cellular volume occupied by mitochondria is increased during H9c2 myoblast differentiation and the tubular mitochondria are reshaped or replaced by a much greater number of individual globular structures. These changes are associated with less dynamic mitochondria and specifically with a decrease in matrix continuity among the individual organelles.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial morphology and dynamics in H9c2 myoblasts and myotubes.

(A) Confocal images of typical non-differentiated (left) and differentiated (right) H9c2 cells loaded with MitoTracker Green FM. The mitochondria of the non-differentiated cell are found predominantly in tubular structures versus the mix of short tubular and globular morphologies in the differentiated cell. (B) Comparison of the mitochondrial density in differentiated, non-differentiated and RyR1-expressing non-differentiated H9c2 cells measured as the fraction of the cell area occupied by mitochondria in confocal micrographs. (Values shown are mean ± SE from 25-30 cells per condition.) (C) Confocal images from a typical FLIP/FRAP experiment with MitoTracker Green stained non-differentiated H9c2 cells under standard conditions: (i) Prebleach, (ii-iv) during bleaching, (v) immediately after bleaching and (vi,vii) during recovery. A close-up of the lower bleaching region is shown (i-v, lower row). The area for FLIP measurement is the area inside the blue box and outside the bleaching area (green box). The loss of fluorescence in the FLIP area of mitochondria partly in the bleach area is visible. The photobleaching resulting from the continuous monitoring of the cell (vii) is evident. (viii) Quantitative analysis of FLIP for the lower region of this cell. (ix) Fluorescence recovery curves after normalization for this cell. (D) Comparison of the fluorescence recovery kinetics of differentiated and non-differentiated cells under standard conditions (solid line and long dash) and at 23 °C when treated with Nocodazole to reduce the movement of the mitochondria (medium dash and short dash). (E) Summary of FLIP/FRAP data comparing differentiated and non-differentiated H9c2. (Values shown are mean ± SE.)

Reorganization of ER/SR Ca2+ mobilization and Ca2+ transfer to the mitochondria during differentiation of H9c2 myoblasts

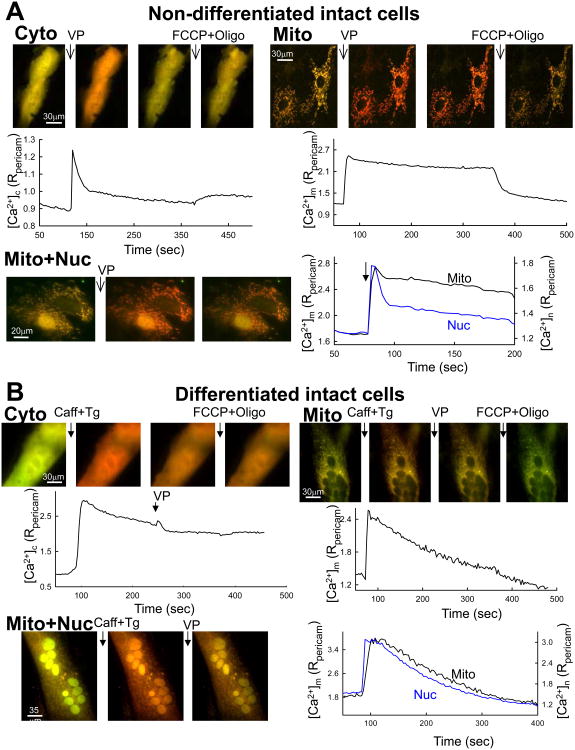

To evaluate the changes of calcium signaling, which takes place in parallel with the restructuring of the mitochondria, we monitored [Ca2+] specifically in the cytoplasm, nucleoplasm and the mitochondrial matrix with ratiometric pericams targeted to the specific compartments [44]. Previous studies used Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent dyes, which are complicated by the possibility of compartmentalization of the dyes to more than one organelle. The studies with pericams confirmed rapid and large [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m increases in myoblasts stimulated by vasopressin (VP), an IP3-linked stimulus of H9c2 cells (Fig2A upper). Due to the spatial overlap between cytoplasm and mitochondria, [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m could be monitored with pericams only in separate measurements. However, it was possible to record nuclear [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]n), a surrogate of [Ca2+]c, simultaneously with [Ca2+]m. This measurement showed that the VP-induced [Ca2+]m rise was tightly coupled to the [Ca2+]n rise in myoblasts (Fig2A lower). Similar studies were also performed in myotubes stimulated with caffeine and thapsigargin (Caff+Tg), a means to evoke concerted activation of the ryanodine receptors. Caff+Tg elicited a prompt and steep increase in both [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m (Fig2B upper). When [Ca2+]m was measured simultaneously with [Ca2+]n, the Caff+Tg-induced [Ca2+]n rise was closely followed by the [Ca2+]m increase (Fig2B lower).

Figure 2. IP3R- and RyR-mediated [Ca2+]c, [Ca2+]mand [Ca2+]nsignals in myoblasts and myotubes.

Non-differentiated (A) and differentiated (B) intact H9c2 cells were transfected with ratiometric pericam (pericam) targeted to the cytosol (Cyto), mitochondria (Mito) or to the nucleus and mitochondria (Mito+Nuc). Myoblasts were stimulated first with vasopressin (VP 100 nM) and myotubes with caffeine (Caff 10mM). To maximize the activation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release, thapsigargin (Tg 2μM) was added together with caffeine. To test for residual IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores in the myotubes, VP was also applied following the caffeine stimulus. At the end of the recording uncoupler (FCCP, 5 μM/oligomycin 5 μg/ml) was added to release Ca2+ from mitochondria. The images show the distribution of the pericam (490nm excitation in red, 415nm excitation in green); note the increase of the red and decrease of the green components upon [Ca2+] elevation. The graphs below/next to the images show the corresponding time course of the pericam ratio (495nm/415nm) recorded and averaged from the cells shown.

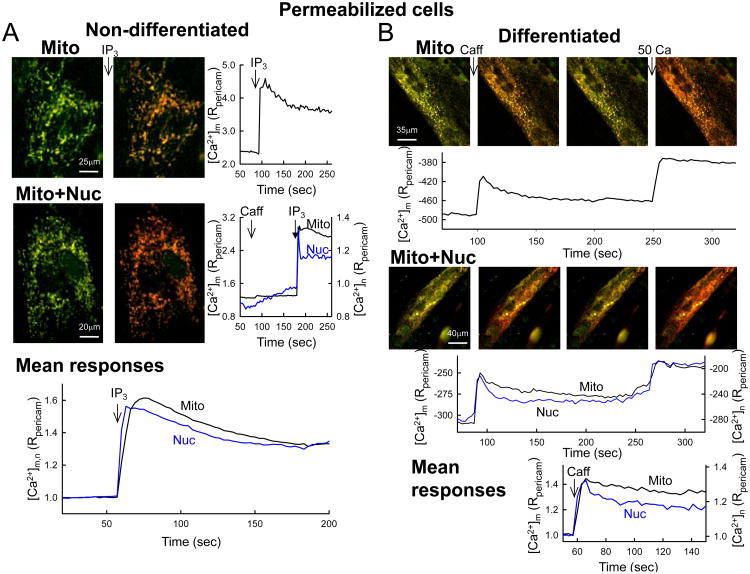

To more directly evaluate the coupling between IP3R or RyR and mitochondria, permeabilized adherent myoblasts and myotubes were used. In these paradigms, Ca2+ released through IP3Rs and RyRs is diluted in a greatly expanded (10,000-fold) cytoplasmic volume, therefore Ca2+ release can stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake only through local interactions [13]. In permeabilized myoblasts, IP3 induced a [Ca2+]m spike that appeared uniformly throughout the cells (Fig3A upper). When [Ca2+]m was monitored simultaneously with [Ca2+]n it became apparent that the IP3-induced [Ca2+]m rise closely followed the [Ca2+]n signal (Fig3A middle and lower). Furthermore, no caffeine induced [Ca2+]n or [Ca2+]m rise was observed in the myoblasts (Fig3A middle). By contrast, permeabilized myotubes responded to caffeine with a rapid [Ca2+]m rise that seemed to affect the entire mitochondrial population (Fig3B upper) and closely followed the [Ca2+]n rise (Fig3B middle and lower). RyRs have been proposed to also localize to and mediate Ca2+ uptake in the mitochondria [48]. In the present permeabilized cell paradigms, ER/SR Ca2+ depletion by Tg abolished the caffeine-induced [Ca2+]m signal. Therefore in our studies RyRs caused a [Ca2+]m rise by mediating ER/SR Ca2+ mobilization (see also [32]). These results show that a local communication between IP3Rs and mitochondria is complemented or replaced with an effective RyR-mitochondrial local Ca2+ coupling during myoblast differentiation. Although mitochondria undergo proliferation and shape changes at the same time, most of the individual mitochondria seem to gain access locally to RyR Ca2+ release.

Figure 3. IP3R- and RyR-dependent [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m signals in permeabilized myoblasts and myotubes.

Non-differentiated (A) and differentiated (B) cells transfected with pericams were digitonin-permeabilized in intracellular medium and treated as in Figure 2, except that only [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m (no [Ca2+]c) were recorded and IP3R/RyR were directly stimulated by IP3 (10 μM) and Caff (10 mM), respectively.

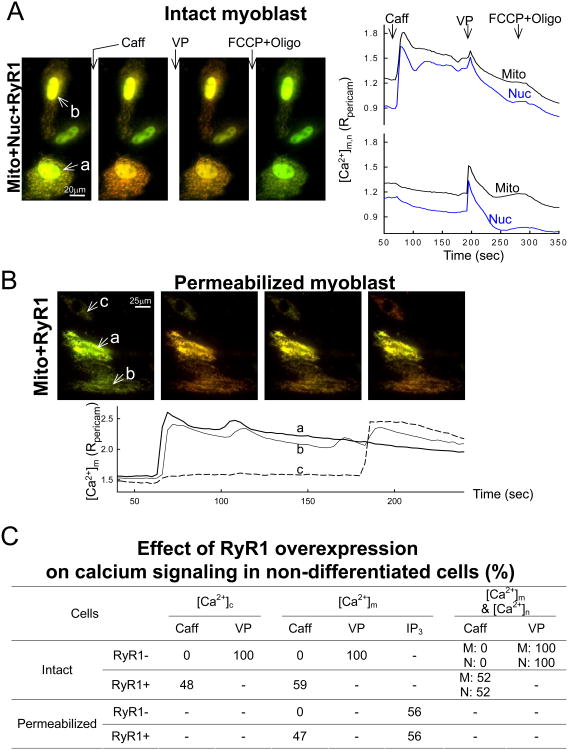

RyR1 expression in H9c2 myoblasts is sufficient to establish the RyR1-mitochondrial local Ca2+ transfer without restructuring the mitochondria

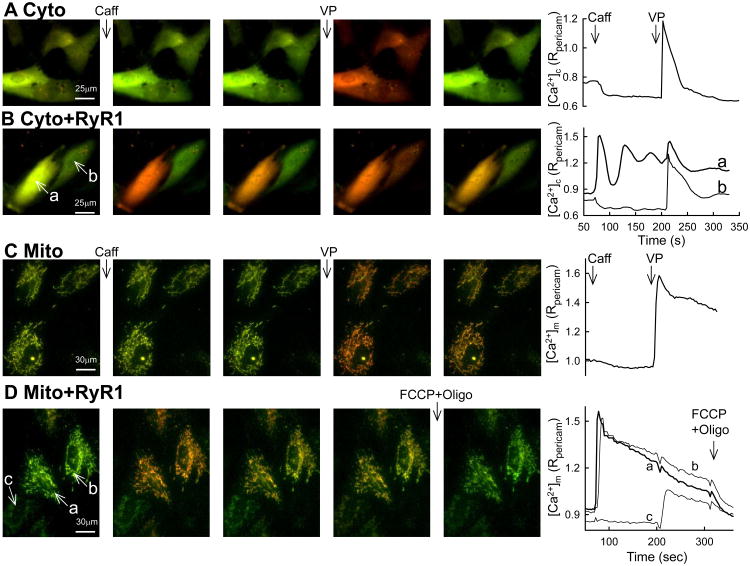

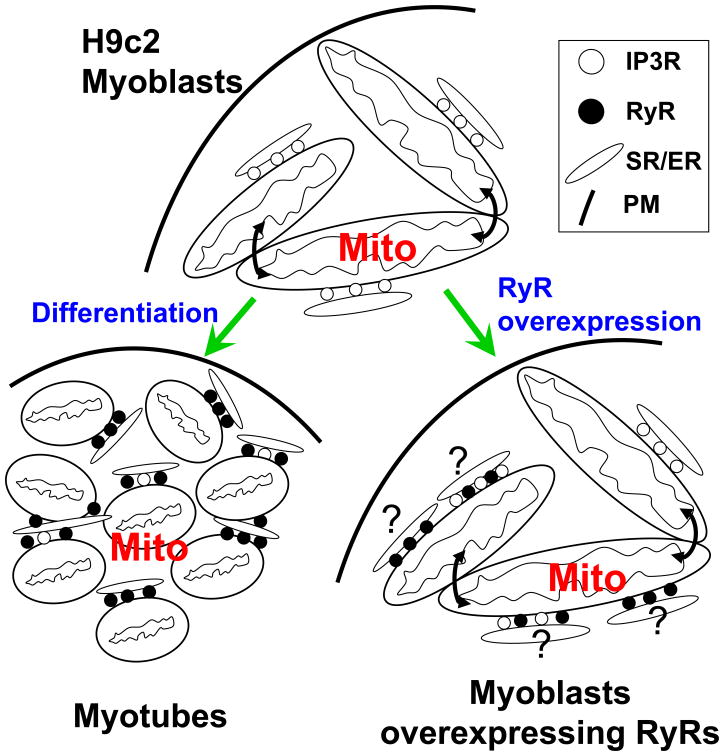

The above results have illustrated that differentiation of the H9c2 myoblasts is a complex process that involves reorganization of the calcium signaling, reshaping of the organelles and changes in dynamics. To determine the specific role of RyR expression in the mitochondrial changes, myoblasts were co-transfected with RyR1 [45] and/or pericams targeted to one or more subcellular compartment. Previously, we have determined that differentiating H9c2 cells express both cardiac and skeletal muscle L type channels and express RyRs that are more similar to human RyR1 than RyR2 [32]. RyR1 expression for 24-72h did not cause a change in cell morphology (Fig4AB) or mitochondrial morphology or density (Fig4CD, Fig1B). Longer overexpression time was not feasible, because the cells reached confluency and undergone spontaneous differentiation. In ∼50% of the RyR1+pericam-transfected cells that showed pericam fluorescence, Caff evoked [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m spikes (Fig4BD) but no response to Caff occurred in cells transfected only with pericam (Fig4AC). Thus, the efficacy of coexpression was ∼50% for the cells transfected with both RyR1 and pericam. When [Ca2+]m was recorded simultaneously with [Ca2+]n a close temporal coupling was confirmed between Ca2+ release and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Fig5A). Notably, cells showing different mitochondrial elongation state had similar relationship between the magnitude of the Caff-induced [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m increases (SFig1), indicating that the overexpressed RyR1s can effectively couple to mitochondria of varying morphology. Measurements of NAD(P)H fluorescence showed that the Caff-induced [Ca2+]m signal resulted in activation of the Ca2+-sensitive mitochondrial matrix dehydrogenases (SFig2), providing evidence for stimulation of oxidative metabolism by the overexpressed RyR1s. When the RyR1+mt-pericam transfected myoblasts were permeabilized, stimulation by Caff again evoked a rapid and steep [Ca2+]m rise (Fig5B). When the results for all the transfected myoblasts were combined, it appeared that intact myoblasts without RyR1 transfection never showed a Caff-induced [Ca2+]c, [Ca2+]n or [Ca2+]m rise but always responded to VP (Fig5C). Furthermore, without RyR1 transfection, none of the permeabilized myoblasts gave a [Ca2+]m response to Caff but 56% displayed an IP3-induced [Ca2+]m signal. By contrast, among the RyR1-transfected myoblasts, 48% showed a [Ca2+]c and 59% showed a [Ca2+]m rise, and strikingly, in the simultaneous recordings there was perfect coincidence of Caff-induced [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m signals (52%, Fig5C Intact RyR+). In the permeabilized myoblast condition, again approximately half of the transfected cells displayed a Caff-induced [Ca2+]m rise (Fig5C Permeabilized RyR+). Notably, the VP-induced [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m responses were preserved in the intact cells, which responded to Caff (SFig3). Also, IP3 could evoke a [Ca2+]m signal in similar fractions of the RyR1+ and RyR1- myoblasts (56% of each, Fig5C), further indicating that the expression of RyR1 did not cause loss of the IP3 receptors. Together, these results strongly support that every single myoblast that expressed RyR1 and showed RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release, also displayed delivery of a fraction of the released Ca2+ to the mitochondria. Since the mitochondrial morphology did not show much change in the RyR1 expressing cells, the expressed RyR1s seem to be able to use the preexisting ER-mitochondrial associations for efficient transfer of Ca2+, or can rapidly trigger the formation of new associations where the RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release can locally stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (see scheme in Fig6).

Figure 4. RyR-and IP3R-dependent [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m signals in myoblasts overexpressing RyR1.

Fluorescence imaging of [Ca2+]m (A,B) and [Ca2+]c (C,D) in non-differentiated intact cells transfected with pericam only (A,C) or co-transfected with RyR1 cDNA from rabbit skeletal muscle (B,D). RyR and IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signals were stimulated sequentially using Caff (10 mM) and VP (100 nM), respectively. The time course traces on the right are either the means recorded from the cells shown on the field (for the mono-transfections A,C) or correspond to the letter-labeled individual cells (for the co-transfections B,D).

Figure 5. RyR-and IP3R-dependent [Ca2+]m signal generation in myoblasts overexpressing RyR1.

Simultaneous recording of [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m in non-differentiated intact cells (A) or [Ca2+]m in permeabilized non-differentiated cells (B) co-transfected with pericam(s) and RyR1. Imaging was carried out 24-36 h after transfection. RyR was activated by Caff (10 mM), while IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signals were stimulated using VP (100 nM) in intact, or directly by IP3 (10 μM) in the permeabilized cells. The table (C) summarizes the results of the imaging experiments studying the [Ca2+]c, [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m responses to Caff and VP/IP3 in RyR1 overexpressing and control cells. Note the obligatory correlation of the Caff-induced [Ca2+]n and [Ca2+]m signals.

Figure 6. Scheme showing the effect of myogenic differentiation and RyR1 expression on ER/SR-mitochondrial calcium signaling in H9c2 myoblasts.

For the sake of simplicity, RyRs are depicted at the SR-mitochondrial interface but in skeletal and cardiac muscle RyRs are localized on the far side of the terminal cisternae associated with the mitochondria [18].

Discussion

The most important findings of this study are that (1) an effective SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling appears in differentiating myoblasts in parallel with RyR1 expression, and (2) expression of RyR1 in myoblasts by itself is sufficient to recruit mitochondria to RyR-mediated Ca2+ release without initiating the gross mitochondrial restructuring occurring during differentiation of myoblasts to myotubes. Thus, the mitochondrial biogenesis and restructuring during myoblast differentiation do not provide any critical factors for the interaction with RyR1.

It is well known that skeletal muscle shows high mitochondrial density relative to myoblasts and mitochondria have been visualized in adult cardiac and skeletal muscle as discrete structures lacking membrane continuity [49, 50]. We showed that in H9c2 cells a large increase in mitochondrial density occurs during differentiation. The increase is noticeable even before fusion of the cells occurs to form multinucleated myotubes (not shown). At the same time we observed the replacement of tubular mitochondria with globular ones, indicating that the balance between fusion-fission is shifted towards fission as the myoblasts differentiate. This result is in line with the observation that Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission is required for myogenic differentiation [51]. The reshaping of mitochondria results in lesser continuity in the intramitochondrial compartments. The motility of the individual organelles is also decreased perhaps resulting from the increase in mitochondrial density. Thus, the apparent trend is that the mitochondria have less content mixing interactions as the myoblasts differentiate, and in turn, have less chance to use the quality control mechanisms proposed to be provided by fusion. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in mouse lacking the outer mitochondrial membrane fusion proteins, Mfn1/2, has been reported [52], but so far, mitochondrial fusion has not been directly demonstrated in either skeletal or cardiac muscle.

Previous studies have implicated calcium in the control of several aspects of the structural events during muscle differentiation, including myofibrillogenesis and cell fusion e.g. [53]. Ca2+ has also been described as a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis e.g. [54], motility [46] and may initiate a decrease in the long tubular structures through the activation of the mitochondrial fission protein, Drp1 [55]. Thus, Ca2+ channels and transporters are likely of relevance for muscle differentiation and reorganization of the mitochondria.

Increased expression of RyR is dispensable for the early events of muscle differentiation, including the upregulation of L-type Ca2+channels, SERCA pumps and junction formation between SR and external membranes [56, 57] However, expression of RyR1 and RyR2 in skeletal and cardiac muscle, respectively, is obligatory for the appearance of excitation-contraction coupling [33-35]. Since a priority in the muscle is to synchronize oxidative energy production to the needs of contraction, recruitment of mitochondria to the RyRs could be a process initiated by some metabolic factors originating with contraction. However, RyR-mitochondrial local Ca2+ coupling also appears in myotubes differentiated from myoblast cell lines, which typically show little contractile activity [42]. It could also be possible that proliferation and reshaping of the mitochondria leads to an interaction with the newly expressed RyRs, however our study shows that this is not the case, as we found RyR1 expression by itself to be sufficient for establishing a local SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ coupling. Thus, both the elongated myoblast mitochondria and the globular myotube mitochondria are competent to respond to RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release. The simplest explanation is that the RyR1s are targeted to the sites where ER is close to mitochondria. An alternative is that the expressed RyR1s provide a signal that leads to recruitment of the mitochondria (see scheme in Fig6). Although RyRs have not been implicated in forming the proteinous links between SR and mitochondria, IP3Rs have been proposed to serve as anchorage sites for ER-mitochondrial contacts [8, 58, 59]. However, an argument against RyR1 initiating a physical linkage is that in the muscle the RyRs are not on the mitochondria-facing surface of the SR [18, 24]. Thus, RyRs are unlikely to recruit mitochondria by forming a scaffold for an SR-mitochondrial physical coupling. It is possible however, that the RyRs serve as a source of a local Ca2+ signal that inhibits the motility of adjacent mitochondria through Miro1 [60-62], and in turn, favors to the formation of new ER/SR-mitochondrial tethers that would promote the RyR1-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Jianjie Ma, Manju Bhat & Zui Pan for the RyR1 vector and advice and Drs. Atsushi Miyawaki and Loren Looger for the vectors encoding Ca2+ sensing fluorescent proteins. This work was supported by an NIH grant (DK051526) to G.H. and by an AHA grant (SDG 0435236N) to G.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shore GC, Tata JR. Two fractions of rough endoplasmic reticulum from rat liver. I. Recovery of rapidly sedimenting endoplasmic reticulum in association with mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1977;72:714–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.72.3.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rusinol AE, Cui Z, Chen MH, Vance JE. A unique mitochondria-associated membrane fraction from rat liver has a high capacity for lipid synthesis and contains pre-Golgi secretory proteins including nascent lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27494–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA, Pozzan T. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science. 1998;280:1763–6. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnoczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–10. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science. 2009;325:477–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T, Rizzuto R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:901–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang HJ, Guay G, Pogan L, Sauve R, Nabi IR. Calcium regulates the association between mitochondria and a smooth subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1489–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmen T, Aslan JE, Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Thomas L, Wan L, Xiang Y, Feliciangeli SF, Hung CH, Crump CM, Thomas G. PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. Embo J. 2005;24:717–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang B, Nguyen M, Chang NC, Shore GC. Fis1, Bap31 and the kiss of death between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. Embo J. 2011;30:451–2. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M, DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J, Voeltz GK. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csordas G, Thomas AP, Hajnoczky G. Quasi-synaptic calcium signal transmission between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Embo J. 1999;18:96–108. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–7. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell. 1995;82:415–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacomello M, Drago I, Bortolozzi M, Scorzeto M, Gianelle A, Pizzo P, Pozzan T. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Mol Cell. 2010;38:280–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csordas G, Varnai P, Golenar T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, Balla T, Hajnoczky G. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franzini-Armstrong C. ER-Mitochondria Communication. How Privileged? Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:261–8. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00017.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys J. 1999;77:1528–39. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boncompagni S, Rossi AE, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Polishchuk RS, Dirksen RT, Protasi F. Mitochondria are linked to calcium stores in striated muscle by developmentally regulated tethering structures. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1058–67. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi T, Martone ME, Yu Z, Thor A, Doi M, Holst MJ, Ellisman MH, Hoshijima M. Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1005–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzini-Armstrong C, Boncompagni S. The evolution of the mitochondria-to-calcium release units relationship in vertebrate skeletal muscles. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:830573. doi: 10.1155/2011/830573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shkryl VM, Shirokova N. Transfer and tunneling of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1547–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma VK, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, Sheu SS. Transport of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in rat ventricular myocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32:97–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1005520714221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi J, Ma C, Li Y, Weisleder N, Rios E, Ma J, Zhou J. Mitochondrial calcium uptake regulates rapid calcium transients in skeletal muscle during excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32436–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.217711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisner V, Parra V, Lavandero S, Hidalgo C, Jaimovich E. Mitochondria fine-tune the slow Ca(2+) transients induced by electrical stimulation of skeletal myotubes. Cell Calcium. 2010;48:358–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brini M, De Giorgi F, Murgia M, Marsault R, Massimino ML, Cantini M, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Subcellular analysis of Ca2+ homeostasis in primary cultures of skeletal muscle myotubes. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:129–43. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Perez C, Hajnoczky G, Csordas G. Physical coupling supports the local Ca2+ transfer between sarcoplasmic reticulum subdomains and the mitochondria in heart muscle. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32771–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803385200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi AE, Boncompagni S, Wei L, Protasi F, Dirksen RT. Differential Impact of Mitochondrial Positioning on Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake and Ca2+ Spark Suppression in Skeletal Muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00194.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robert V, Gurlini P, Tosello V, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Di Lisa F, Pozzan T. Beat-to-beat oscillations of mitochondrial [Ca2+] in cardiac cells. Embo J. 2001;20:4998–5007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianchi K, Vandecasteele G, Carli C, Romagnoli A, Szabadkai G, Rizzuto R. Regulation of Ca2+ signalling and Ca2+-mediated cell death by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:586–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szalai G, Csordas G, Hantash BM, Thomas AP, Hajnoczky G. Calcium signal transmission between ryanodine receptors and mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15305–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brillantes AM, Bezprozvannaya S, Marks AR. Developmental and tissue-specific regulation of rabbit skeletal and cardiac muscle calcium channels involved in excitation-contraction coupling. Circ Res. 1994;75:503–10. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeshima H, Iino M, Takekura H, Nishi M, Kuno J, Minowa O, Takano H, Noda T. Excitation-contraction uncoupling and muscular degeneration in mice lacking functional skeletal muscle ryanodine-receptor gene. Nature. 1994;369:556–9. doi: 10.1038/369556a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flucher BE, Andrews SB, Daniels MP. Molecular organization of transverse tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum junctions during development of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:1105–18. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.10.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takekura H, Flucher BE, Franzini-Armstrong C. Sequential docking, molecular differentiation, and positioning of T-Tubule/SR junctions in developing mouse skeletal muscle. Dev Biol. 2001;239:204–14. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama H, Bodi I, Maillet M, DeSantiago J, Domeier TL, Mikoshiba K, Lorenz JN, Blatter LA, Bers DM, Molkentin JD. The IP3 receptor regulates cardiac hypertrophy in response to select stimuli. Circ Res. 2010;107:659–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harzheim D, Movassagh M, Foo RS, Ritter O, Tashfeen A, Conway SJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Increased InsP3Rs in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum augment Ca2+ transients and arrhythmias associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11406–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905485106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zima AV, Bare DJ, Mignery GA, Blatter LA. IP3-dependent nuclear Ca2+ signalling in the mammalian heart. J Physiol. 2007;584:601–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell JA, Carrasco MA, Adams DS, Drouet B, Rios J, Muller M, Estrada M, Jaimovich E. IP(3) receptor function and localization in myotubes: an unexplored Ca(2+) signaling pathway in skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3673–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pacher P, Csordas P, Schneider T, Hajnoczky G. Quantification of calcium signal transmission from sarco-endoplasmic reticulum to the mitochondria. J Physiol. 2000;529 Pt 3:553–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pacher P, Thomas AP, Hajnoczky G. Ca2+ marks: miniature calcium signals in single mitochondria driven by ryanodine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2380–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032423699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Comelli M, Domenis R, Bisetto E, Contin M, Marchini M, Ortolani F, Tomasetig L, Mavelli I. Cardiac differentiation promotes mitochondria development and ameliorates oxidative capacity in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagai T, Sawano A, Park ES, Miyawaki A. Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3197–202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051636098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhat MB, Zhao J, Zang W, Balke CW, Takeshima H, Wier WG, Ma J. Caffeine-induced release of intracellular Ca2+ from Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Effects on full-length and carboxyl-terminal portion of Ca2+ release channels. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:749–62. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi M, Weaver D, Hajnoczky G. Control of mitochondrial motility and distribution by the calcium signal: a homeostatic circuit. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:661–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pacher P, Hajnoczky G. Propagation of the apoptotic signal by mitochondrial waves. Embo J. 2001;20:4107–21. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beutner G, Sharma VK, Giovannucci DR, Yule DI, Sheu SS. Identification of a ryanodine receptor in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21482–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vendelin M, Beraud N, Guerrero K, Andrienko T, Kuznetsov AV, Olivares J, Kay L, Saks VA. Mitochondrial regular arrangement in muscle cells: a “crystal-like” pattern. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C757–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00281.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birkedal R, Shiels HA, Vendelin M. Three-dimensional mitochondrial arrangement in ventricular myocytes: from chaos to order. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1148–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00236.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Palma C, Falcone S, Pisoni S, Cipolat S, Panzeri C, Pambianco S, Pisconti A, Allevi R, Bassi MT, Cossu G, Pozzan T, Moncada S, Scorrano L, Brunelli S, Clementi E. Nitric oxide inhibition of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission is critical for myogenic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1684–96. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen H, Vermulst M, Wang YE, Chomyn A, Prolla TA, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion is required for mtDNA stability in skeletal muscle and tolerance of mtDNA mutations. Cell. 2010;141:280–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porter GA, Jr, Makuck RF, Rivkees SA. Reduction in intracellular calcium levels inhibits myoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28942–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruton JD, Aydin J, Yamada T, Shabalina IG, Ivarsson N, Zhang SJ, Wada M, Tavi P, Nedergaard J, Katz A, Westerblad H. Increased fatigue resistance linked to Ca2+-stimulated mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle fibres of cold-acclimated mice. J Physiol. 2010;588:4275–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15803–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C, Allen PD. Role of ryanodine receptors in the assembly of calcium release units in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:831–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park MY, Park WJ, Kim DH. Expression of excitation-contraction coupling proteins during muscle differentiation. Mol Cells. 1998;8:513–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szabadkai G, Simoni AM, Bianchi K, De Stefani D, Leo S, Wieckowski MR, Rizzuto R. Mitochondrial dynamics and Ca2+ signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mendes CC, Gomes DA, Thompson M, Souto NC, Goes TS, Goes AM, Rodrigues MA, Gomez MV, Nathanson MH, Leite MF. The type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor preferentially transmits apoptotic Ca2+ signals into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saotome M, Safiulina D, Szabadkai G, Das S, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G. Bidirectional Ca2+-dependent control of mitochondrial dynamics by the Miro GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Schwarz TL. The mechanism of Ca2+ -dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136:163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macaskill AF, Rinholm JE, Twelvetrees AE, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Muir J, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Attwell D, Kittler JT. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61:541–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.