SUMMARY

To simulate transient B cell activation that is the likely initiator of T-dependent responses, we examined the molecular and functional consequences of a single-round of immunoglobulin M (IgM) signaling. This form of activation triggered early cytosolic signaling and the transcription factor NF-κB activation indistinguishably from conventional continuous IgM cross-linking, but did not induce G1 progression. However, single-round IgM signaling changed the expression of chemokine and chemokine receptor genes implicated in initiating T-dependent responses, as well as accentuated responsiveness to CD40 signaling. Several features of single-round IgM signaling in vitro were recapitulated in B cells after short-term exposure to antigen in vivo. We propose that transient BCR signals prime B cells to receive T cell help by increasing the probability of B-T encounter and creating a cellular environment that is hyper-responsive to CD40 signaling.

The B cell antigen receptor (BCR) is essential for cell survival and immune responses (Kraus et al., 2004; Niiro and Clark, 2002). The enigmatic nature of BCR-initiated survival signals has clarified through the demonstration of a key role for PI3-kinase (Srinivasan et al., 2009). Antigen binding to the BCR, which is mimicked by BCR cross-linking, activates Src kinases that phosphorylate immune receptor-based activation motifs of Igα and Igβ. Phosphorylated Igα, β recruit and activate the tyrosine kinase Syk, leading to phosphorylation of downstream effector molecules such as BLNK, BCAP and BAM32 that mediate activation of MAP- and PI3-kinases essential for cell proliferation and survival (Harwood and Batista, 2008; Kurosaki et al., 2009). Genetic mutations of these signaling proteins corroborate their essential role in B cell responses (Niiro et al., 2002; Shinohara and Kurosaki, 2006).

Cytosolic signaling occurs within minutes of BCR cross-linking, however, B cell proliferation is only evident after two days of activation (Proust et al., 1985). Because the BCR is rapidly capped and endocytosed in response to cross-linking (Gazumyan et al., 2006), the cell surface loses detectable IgM within a few minutes of activation. The continued need for anti-IgM to induce proliferation is therefore thought to reflect re-expression of surface Ig followed by immediate endocytosis in response to cross-linking. In this way signals persist despite undetectable cell surface Ig during most of the activation period. Because receptor re-expression is relatively slow and takes several hours to reach half-maximal levels (Ferrarini et al., 1976), signaling via re-expressed receptors may be different from that of initial receptor cross-linking. Thus, the cellular response to continuous BCR stimulation is a superposition of effects of initial BCR cross-linking, re-expressed BCR cross-linking and internalized BCR signaling. The contribution of each component to the ultimate outcome is not clear.

The question of duration and function of Ig signals has been previously addressed. DeFranco et al. identified a commitment stage that occurs 8–10 hours prior to onset of S phase, beyond which anti-IgM signaling is no longer required (DeFranco et al., 1985). Though the analysis was carried out before molecular signatures of cell cycle were readily available, it is likely that this step corresponds to the G1-S restriction point characterized by hyperphosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, release of the E2F family of transcription factors and consequent induction of S-phase genes (Blomen and Boonstra, 2007). In addition, they found that early steps of G1 progression, as assessed by increased cell size, were effectively activated by lower concentrations of anti-IgM than those required for cells to progress to the commitment stage. The molecular basis for this, and the intracellular events that occur between the initial phosphorylation cascade and progression through G1, remain unclear.

Much is known about signaling cascades activated by key B cell surface molecules. Anti-IgM signaling that culminates in cell proliferation is used as a surrogate for T-independent B cell responses, and CD40 activation is used to simulate B cells receiving T cell help. Additionally, signaling via co-receptors such as CD19, or inhibitory receptors such as CD22 or Fc receptors, has also been extensively examined. An aspect of B cell activation that is relatively understudied is the steps that lead up to T-dependent immune responses. BCR-bound antigens are taken up by B cells and processed for presentation on MHC class II (MHC-II) to activate antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Once activated, CD4+ T cells secrete cytokines and express CD40 ligand, both of which substantially impact subsequent B cell responses. However, it is not clear whether antigen uptake alters B cell physiology and, if so, with what consequence. It is also unclear how a B cell that has taken up antigen finds the right T cell, how long it has to do so or what happens if it does not.

In this paper we used a pulsed-activation protocol to examine molecular and functional consequences of a single-round of BCR signaling. We found that this restricted form of signaling activated early cytosolic pathways identical to those seen in cells treated continuously with anti-IgM, including MAP- and PI3 kinases and the first of two phases of NF-κB induction. However, these signals were insufficient for G1 progression or to rescue B cells from cell death. Pulsed activation up-regulated MHC-II expression on the cell surface and had long lasting effects on cell physiology that included induction of chemokine and chemokine receptor gene expression. Additionally, pulse-activated cells were hyper-responsive to CD40 signals. Several features of pulse activation, including hyper-responsiveness to CD40 were recapitulated in mice after short-term exposure of B cells in Vh186.2 mIgM-Tg mice to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl (NP) - BSA. We propose that a single round of BCR signaling primes B cells in multiple ways to receive T cell help.

RESULTS

We hypothesized that antigen uptake via the BCR, en route to T-dependent responses, may provide transient signals to B cells. In the most extreme form of transient signaling BCR cross-linking and endocytosis occur only once. To achieve this, we bound anti-IgM to spleen B cells at 4° C, removed unbound anti-IgM from the medium, and then initiated signaling by placing the cells at 37° C. We reasoned that this experimental protocol provided a single round of BCR-initiated signals because re-expressed receptors could not be re-cross-linked due to absence of anti-IgM in the medium. We shall refer to this as pulsed activation. In order to make the best comparisons, cells for continuous stimulation were also incubated with anti-IgM at 4° C, and then raised to 37° C without washing out unbound anti-IgM (Fig. S1A).

Signaling consequences of pulsed activation

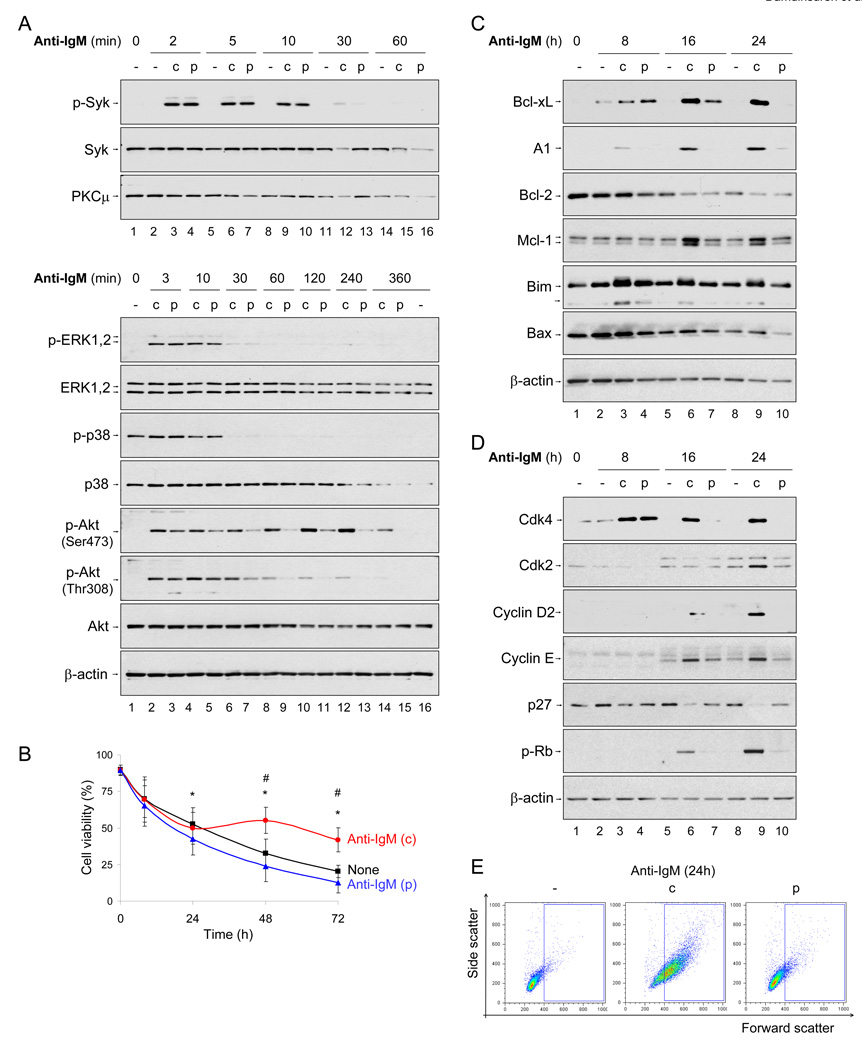

Cytosolic signaling was assayed in pulse (p) or continuously (c) activated cells by immunoblotting for phosphorylated proteins. Syk, ERK1, 2 and p38 activation was identical between the two forms of signaling (Fig. 1A). In contrast, Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 and Thr308 was induced transiently by pulsed signaling (Fig. 1A, lanes 3, 5, 7), but required continuous anti-IgM treatment to be effectively maintained beyond 60 min, particularly at Ser473 (Fig. 1A, lanes 8, 10, 12). Because Akt is activated downstream of PI3K, we infer that a pulse of BCR signaling activates, but does not maintain, PI3K activity. Thus, one of the signaling consequences of re-expressed receptors during continuous anti-IgM treatment is to maintain PI3K activity.

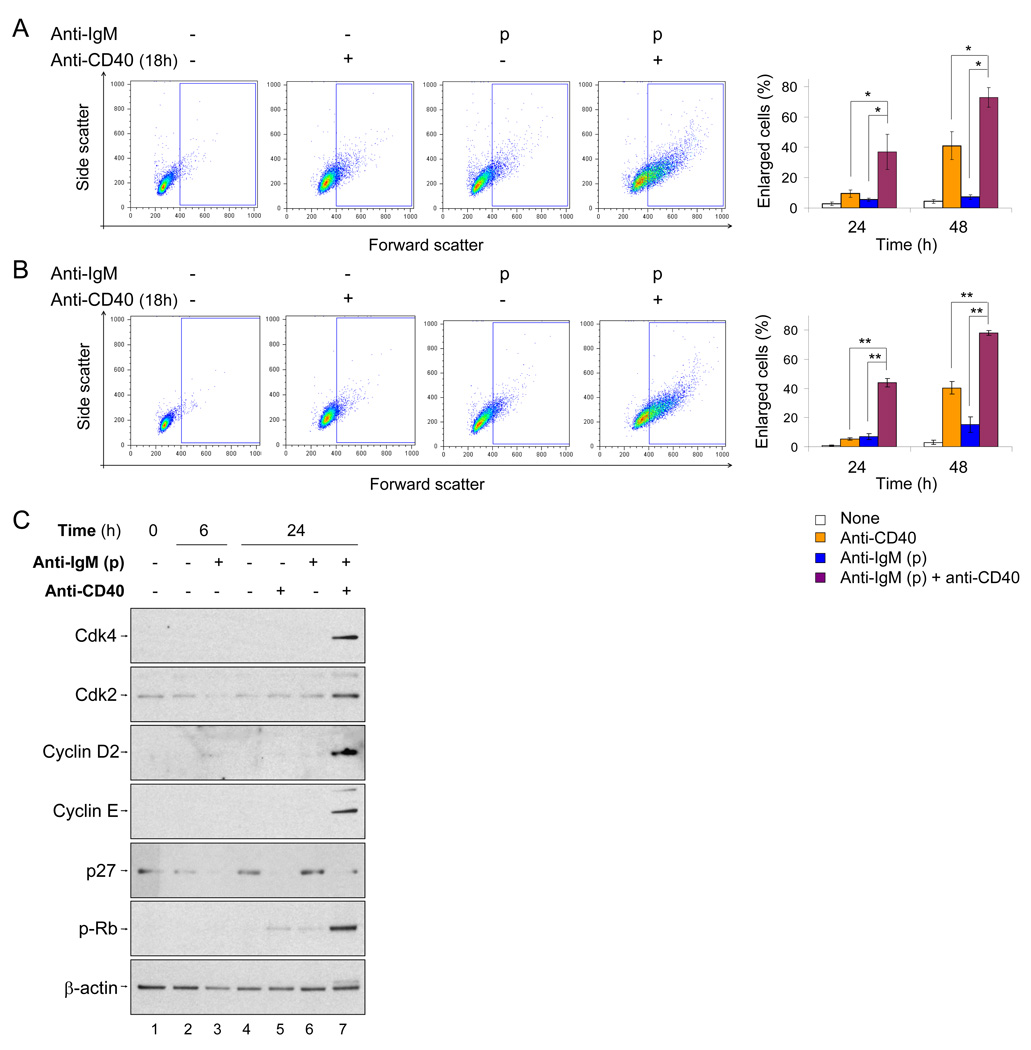

Fig. 1. Pulsed activation induces cell death without G1 progression.

Purified spleen B cells were activated according to the scheme shown in Fig. S1A. For pulsed (single-round) BCR activation, cells were incubated with F(ab')2 anti-IgM (10µg/ml) on ice for 30 minutes, washed with cold PBS, re-suspended in fresh cold medium and moved to a 37°C incubator. At various times thereafter viability was determined by propidium iodide (PI) exclusion with flow cytometry (B) or whole cell extracts (WCE) prepared for protein analyses (A, C and D). For continuous activation anti-IgM was bound to cells on ice for 30 minutes and then moved directly to 37°C without intermediate washing steps.

A) Early signal transduction in pulse (p) and continuously (c) activated cells. WCE prepared at times shown above the lanes were examined by immunoblotting. “p” prefix denotes the phosphorylated form of the kinase. Protein loading was normalized against PKCμ or β-actin. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

B) Cell viability (Y axis) after pulsed (p, blue line), continuous (c, red line) or no anti-IgM (black line) treatment was determined by PI exclusion at the times indicated (X axis). Data shown is the average of 9 independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) between experiments. * p=0.017, p=0.013 and p=0.034 between pulsed and no anti-IgM at 24, 48 and 72h time points, respectively. # p<0.001 between continuous and none anti-IgM treatment at 48 and 72h by Mann-Whitney U test.

C) Pro- and anti-apoptotic protein expression in activated B cells. WCE from pulse (p) or continuously (c) activated cells prepared at the indicated times were immunoblotted with antibodies against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, or BH3-only proteins. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

D) Molecular analysis of cell cycle progression. B cells were activated by pulse (p) or continuous (c) anti-IgM treatment, and cell cycle progression followed by analysis of molecular markers of G1 progression by immunoblotting of WCE. Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown.

E) G1 progression analysis by cell size. Live B cells were analyzed by forward and side scatter to estimate frequency of enlarged cells (Fig. S1B). Representative flow cytometry pattern at 24h time point is shown. The average of 6 independent experiments is shown in Fig. S1C.

Unlike continuous anti-IgM treatment, pulsed activation led to increased B cell apoptosis (Fig. 1B). To determine the cause of cell death, we examined expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic proteins over a 24h period (Fig. 1C). Bcl-2 protein was down-regulated during ex vivo incubation, while long-term induction of Bcl-xL, A1 and Mcl-1 required continuous activation with anti-IgM (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 6, 7 and 9, 10). Of the pro-apoptotic proteins examined, the amount of Bim increased transiently in response to pulsed activation (lane 4), whereas Bax was largely unaffected by either form of stimulation. Though Bim expression was highest in continuously activated cells, its effect was presumably offset by compensatory increase in Bcl-xL, A1 and Mcl-1 proteins. Taken together, these observations indicated that pulse activated cells died due to inefficient long-term induction of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins.

Pulsed stimulation is insufficient for G1 progression

Hallmarks of G1 progression include activation of cyclin D-Cdk4, 6 complexes in early-mid G1, hyperphosphorylation of Rb in late G1 and activation of cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes at the G1-S boundary (Piatelli et al., 2003). In addition, c-myc induction and down-regulation of p27Kip1 (p27) are considered essential to proceed through G1 (de Alboran et al., 2001; Soeiro et al., 2006). Although Myc mRNA induction was very similar between pulse- and continuously activated cells (Fig. S1D), most other signatures of G1 progression were impaired in pulse-activated B cells (Fig. 1D). We observed transient induction of Cdk4 (Fig. 1D, lane 4), and virtually no induction of cyclin D2, cyclin E and Cdk2 in response to pulse activation (Fig. 1D, lanes 4, 7, 10). Likewise, Rb hyperphosphorylation and p27 degradation occurred most effectively in continuously-activated cells (Fig. 1D, lanes 6, 9). In keeping with the lack of molecular signatures of G1 progression, pulse-activated cells remained small as estimated by flow cytometry (Fig. 1E, averaged data in Fig. S1C). We conclude that normal early cytosolic signaling and Myc mRNA induction are insufficient for G1 progression in pulse-activated cells.

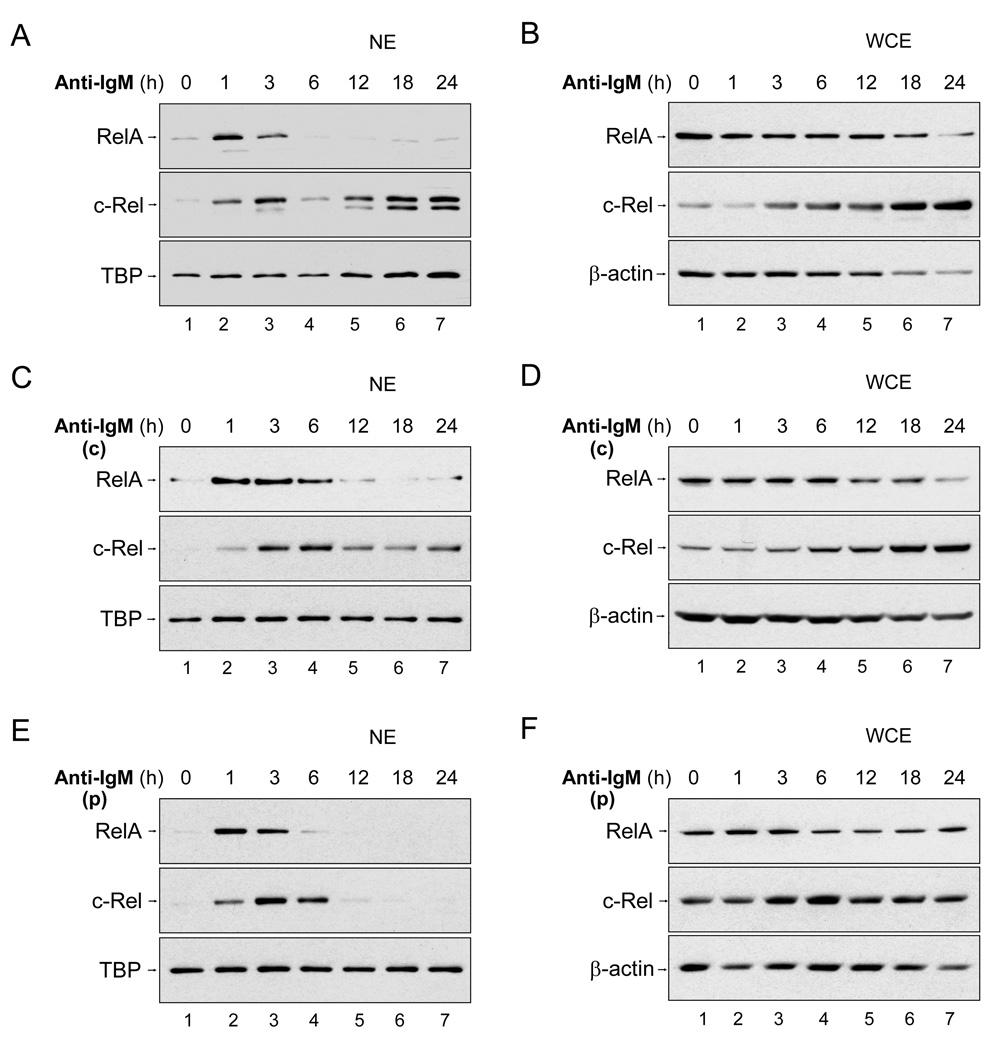

Pulsed stimulation induces phase 1 NF-κB

Bcl2l1 (encoding Bcl-xL) and Myc have been previously proposed to be NF-κB target genes (Duyao et al., 1990; Lee et al., 1999). Because both genes were induced in response to pulse activation, we examined NF-κB induction in pulsed- and continuously-stimulated cells. Addition of anti-IgM to splenic B cells maintained at 37° C resulted in rapid, but transient (~6h), activation of nuclear RelA (p65) and c-Rel (Fig. 2A). At longer time points we observed a second wave of nuclear c-Rel in the absence of RelA (Fig. 2A, lanes 5–7). We shall refer to these as Phase I and II NF-κB responses. Phase I coincided with reduced IκBα expression (Fig. S2A) indicating it was mediated by the canonical post-translational NF-κB activation pathway. Phase II was not associated with IκB degradation, but with increased total levels of cellular c-Rel (Fig. 2B, lanes 6–7). A qualitatively similar, though delayed, bi-phasic response occurred when cells were treated with anti-IgM at 4° C and then raised to 37° C according to the 'continuous' scheme in Fig. S1A (Fig. 2C, averaged data in Fig. S2D). Here the Phase I response peaked around 3–6h, and new c-Rel synthesis was evident beyond 18h of activation (Fig. 2D). Our interpretation is that an extended phase I overlapped with synthesis-dependent phase II to reduce the minima in c-Rel expression between the two phases.

Fig. 2. Pulsed activation induces only phase I NF-κB.

B cells were activated by anti-IgM using three schemes as described below. At various times after activation nuclear extracts (NE) or WCE were prepared as outlined in Experimental Procedures, assayed by immunoblotting using antibodies against NF-κB family members, RelA and c-Rel, as indicated. TATA-binding protein (TBP) and β-actin were used as the loading controls for NE and WCE, respectively.

A, B) Anti-IgM was added to B cells maintained at 37°C to imitate conventional continuous anti-IgM activation. At the indicated times protein extracts were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting. Analysis of corresponding WCE for IκB expression is shown in Fig. S2A.

C – F) B cells were treated with anti-IgM at 4°C for 30 min and then raised to 37°C with, or without, washing to remove excess unbound anti-IgM to initiate pulse (p, in E and F) or continuous (c, in C and D) activation (see scheme in Fig. S1A). Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments with each activation protocol. IκB expression in corresponding WCE is shown in Fig. S2B and C, and quantitation of bi-phasic c-Rel activation in Fig. S2D.

Pulsed activation resulted in only phase I NF-κB induction. Both RelA and c-Rel translocated rapidly, but transiently, to the nucleus of pulse-activated cells, whereas long-term c-Rel induction was not detected (Fig. 2E, F). As seen in cells treated continuously with anti-IgM, phase I induction in response to pulse-activation coincided with IκBα degradation (Fig. S2C). We conclude that BCR cross-linking induces two temporally distinct phases of NF-κB activation. Phase I, which involves RelA and c-Rel, and lasts approximately 6h, is the response to a single round of antigen receptor signaling; phase II is mediated by de novo c-Rel synthesis and requires continued stimulation by anti-IgM. Thus, transient Bcl-xL and Myc mRNA induction observed in response to pulse-activation, is likely to be the consequence of phase I NF-κB.

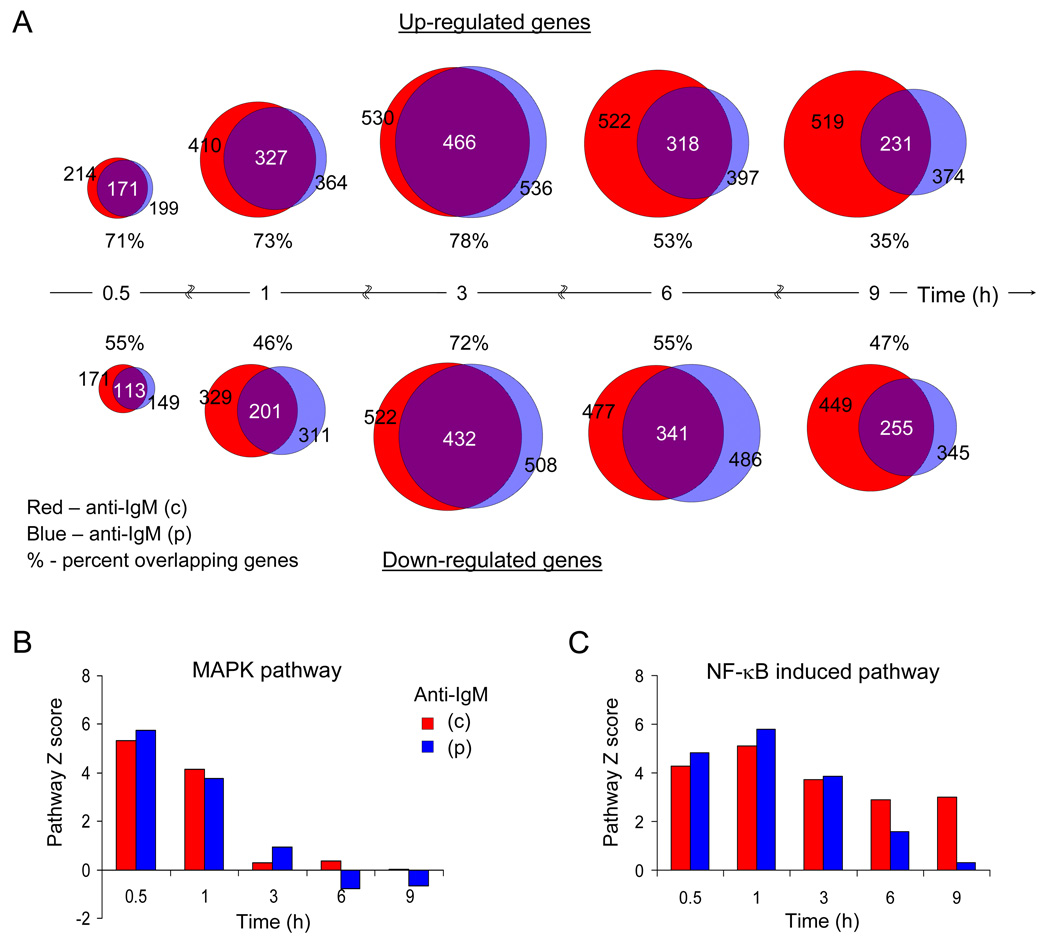

Gene expression in pulse-activated B cells

To gain insight into gene regulatory consequences of pulsed versus continuous anti-IgM stimulation, we compared mRNA profiles over a 9 hour time course using Illumina 22K oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Two features were readily evident. First, there was considerable overlap between up- and down-regulated genes in response to either form of stimulation (Fig. 3A). For up-regulated genes the maximum overlap occurred at early time points (0.5 to 3h), whereas down-regulated genes overlapped maximally at an intermediate time point (3h). Pulsed activation induced conventional immediate early genes such as Fos, Jun, Egr1 and Egr2, and additional genes involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements, plasma membrane components and cytosolic signaling molecules (Table S1A). Consistent with the similarity in early signaling events in pulse and continuously activated cells, Ingenuity pathway analysis of the RNA data set showed identical activation of the MAP kinase pathway (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the NF-κB pathway was transiently activated in pulsed cells (Fig. 3C), presumably reflecting the lack of phase II NF-κB induction. Second, pulsed-activation led to long term changes in gene expression that lasted up to 9h after the stimulus. Strikingly, many up- and down-regulated genes at the 9h time point were unique to each form of stimulation (Table S1B, C). We conclude that a single round of BCR signaling substantially alters the resting state of B cells for prolonged time periods.

Fig. 3. Pulse activation causes long-term changes in gene expression.

A) B cells were activated with pulsed or continuous anti-IgM according to the scheme in Fig. S1A. Total RNA isolated at the indicated times was converted to cDNA and hybridized to 22K Illumina arrays as detailed in Experimental Procedures. At each time point statistically significant genes that were up- (top row) or down-regulated (bottom row) in response to anti-IgM were compared between pulse- (p) or continuously (c) activated cells. Blue and red circles represent the mRNAs that are changed as a consequence of pulsed or continuous anti-IgM treatment, respectively; the size of circles is proportional to the numbers of genes in each pool as indicated, and the extent of overlap represents changes that were common to both forms of stimulation. The number of shared genes between the two forms of activation is shown in the overlap. The percentage of altered mRNAs shared between pulse- and continuously- activated cells is indicated below the circles. Data shown is derived from 3 independent experiments. See Table S1 for gene expression data.

B, C) The RNA data from part A was analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway analysis software. The pathway Z scores for MAPK associated and NF-κB-induced mRNAs relative to unactivated cells is shown (Y axis) as a function of time (X axis) for pulse (blue bars) and continuous (red bars) activation regimens.

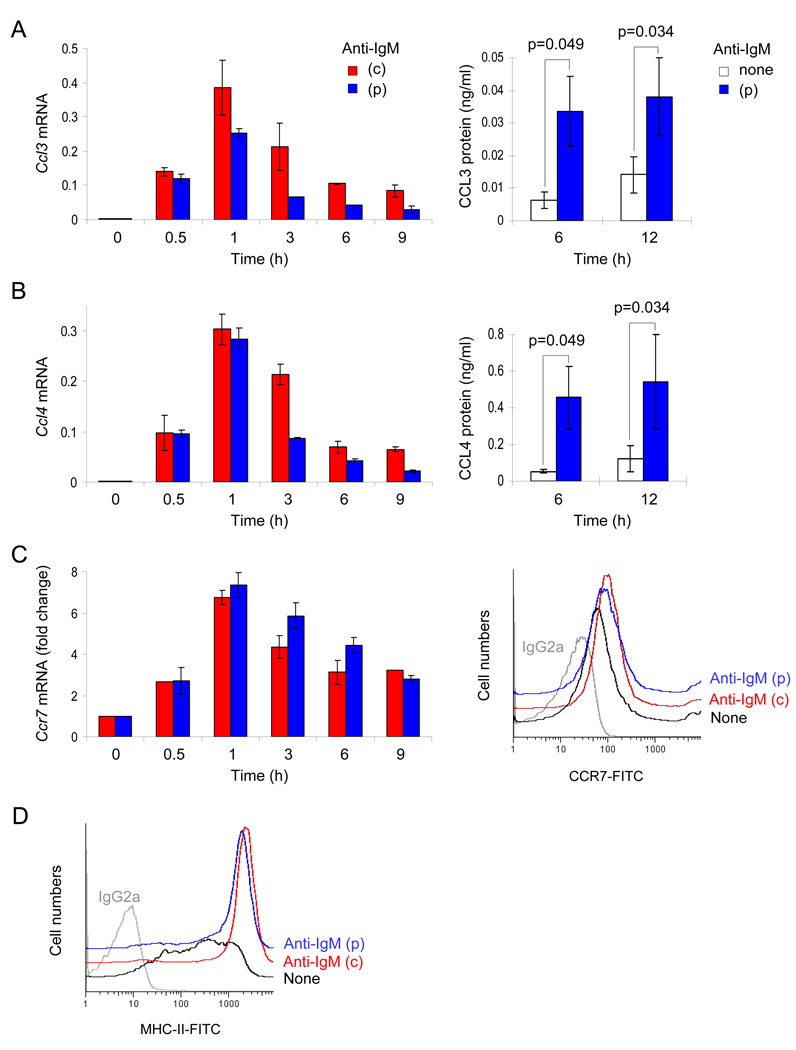

Functional consequences of pulse-activation

The diversity of gene expression changes induced by a single-round of BCR activation prompted us to look for genes that may affect B cell function. We first focused on possible targets of phase I NF-κB activation. Microarray analyses revealed that pulsed activation rapidly induced expression of the genes encoding chemokines CCL3 and CCL4, as well as the gene encoding the chemokine receptor CCR7 (Fig. S3). These genes were of particular interest because CCL3 and 4 are known chemo-attractants for CD4+ T cells (Bystry et al., 2001; Taub et al., 1993) and CCR7 has been implicated in the migration of activated B cells towards the T cell zone of the spleen (Reif et al., 2002). We confirmed the microarray data using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 4A–C, left panels). Additionally, these results were corroborated by ELISAs measuring chemokine protein in culture supernatants from pulse-activated cells (Fig. 4A and B, right panels), and by flow cytometry for cell surface CCR7 expression (Fig. 4C, right panel). One of the major functions of activated B cells is to present MHC-II-bound antigenic peptide to CD4+ T cells. MHC-II has been previously shown to be up-regulated by BCR cross-linking (Marshall-Clarke et al., 2003). We found that single-round BCR uptake was sufficient to increase surface MHC-II expression (Fig. 4D). We infer that pulsed activation increases the probability of B cell encounter with T cells and potentiates antigen presentation by elevating MHC-II expression.

Fig. 4. Pulse activation induces chemokines and cell surface receptors involved in B-T interaction.

A, B) B cells were activated with pulse (p) or continuous (c) anti-IgM stimulation. At various times after initiation of signaling, Ccl3 (A), Ccl4 (B) mRNA and secreted proteins were examined by qRT-PCR (see also Fig. S3) or ELISA, respectively. Ccl3 and Ccl4 mRNAs were normalized to Actin mRNA. Data shown is the average of 2 independent RNA time-course experiments with RT-PCR assays being carried out in duplicates. For analysis of secreted chemokines, culture medium from untreated or pulse-treated B cells were collected at 6 and 12h time points. CCL3 and CCL4 protein was detected by ELISA. Data shown is the average ±SD of 3 independent experiments. P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test.

C) Ccr7 mRNA expression was examined by qRT-PCR as described in parts A and B; Y axis indicates the fold increase in normalized Ccr7 mRNA expression compared to 0h. To detect cell surface expression of CCR7 protein, cells were harvested at 24h after activation and immunostained using CD197-FITC antibody. Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. Median fluorescence intensities (MFI) of CCR7 expression for unactivated (black), continuously (red) - and pulsed (blue) -activated cells were 56.5±7.7, 91±14.1 and 86±1.4, respectively.

D) Cell surface expression of MHC-II protein. Cells were harvested at 12h after pulsed- or continuous-activation, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. MFIs of MHC-II expression for unactivated (black), continuously (red) - and pulsed (blue) -activated cells were 269±74, 2320±179 and 1544±83, respectively.

To determine whether pulse-activated B cells also altered their responsiveness to receive T cell help, naïve B cells were activated with a single-round of BCR cross-linking, and after 6h, treated with CD40 antibody for an additional 18 or 42h (Fig. S4A). Anti-CD40 treatment rescued untreated or pulse anti-IgM treated B cells from cell death (Fig. S4B). Moreover, cells that had been pulsed with anti-IgM 6h prior to anti-CD40 treatment, underwent blast formation 4-fold more effectively than naïve B cells at 24h (Fig. 5A). Higher blast formation was also apparent after 42h of anti-CD40 stimulation, but the synergistic effect was less pronounced (Fig. 5A, bar graph). We confirmed that this was a feature of mature follicular B cells using CD21+CD23int cells purified by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). Cells treated continuously with anti-IgM also responded more efficiently to anti-CD40 treatment (Fig. S4C). We used immunoblotting to examine molecular hallmarks of G1 progression. Compared to either stimulus alone, we found increased expression of Cdk2 and 4, cyclin D2 and E, and hyperphosphorylated Rb in pulse-activated cells that had been treated with anti-CD40 for additional 18h (Fig. 5C, lane 7 compared to lanes 5, 6). However, CD40 activation alone was sufficient to induce p27 degradation (Fig. 5C, lane 5). We conclude that a pulse of BCR signaling primes B cells to respond more effectively to CD40.

Fig. 5. Pulse activation primes B cells to respond to CD40 signals.

B cells were left untreated- or pulse-activated (p) at 0h. 6h later anti-CD40 was added to both cultures, and 18h later cells harvested to assay G1 progression by flow cytometry and molecular markers (Fig. S4A).

A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD40 responsiveness of pulse-activated cells gated on live cells. Enlarged cells compared to the starting naïve B cell population were scored as described in Fig. S1B. Bar graph shows the average of 8 independent blast formation experiments represented as the percentage of cells that fall in the enlarged cell gate. Bars represent average ± SD between experiments. * indicate p<0.001 between treatments by Mann-Whitney U test.

B) Sorted follicular B cells (Fig. S4D) were activated by pulse (p) anti-IgM and anti-CD40, and cell cycle progression followed by cell size using flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry pattern after 18h anti-CD40 treatment is shown. Bar graphs the average ±SD of 3 experiments. ** indicate p<0.01 between treatments by Mann-Whitney U test.

C) WCEs prepared from cells activated according to the scheme described above, were blotted with antibodies against the G1 phase markers. Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments.

In vivo B cell priming

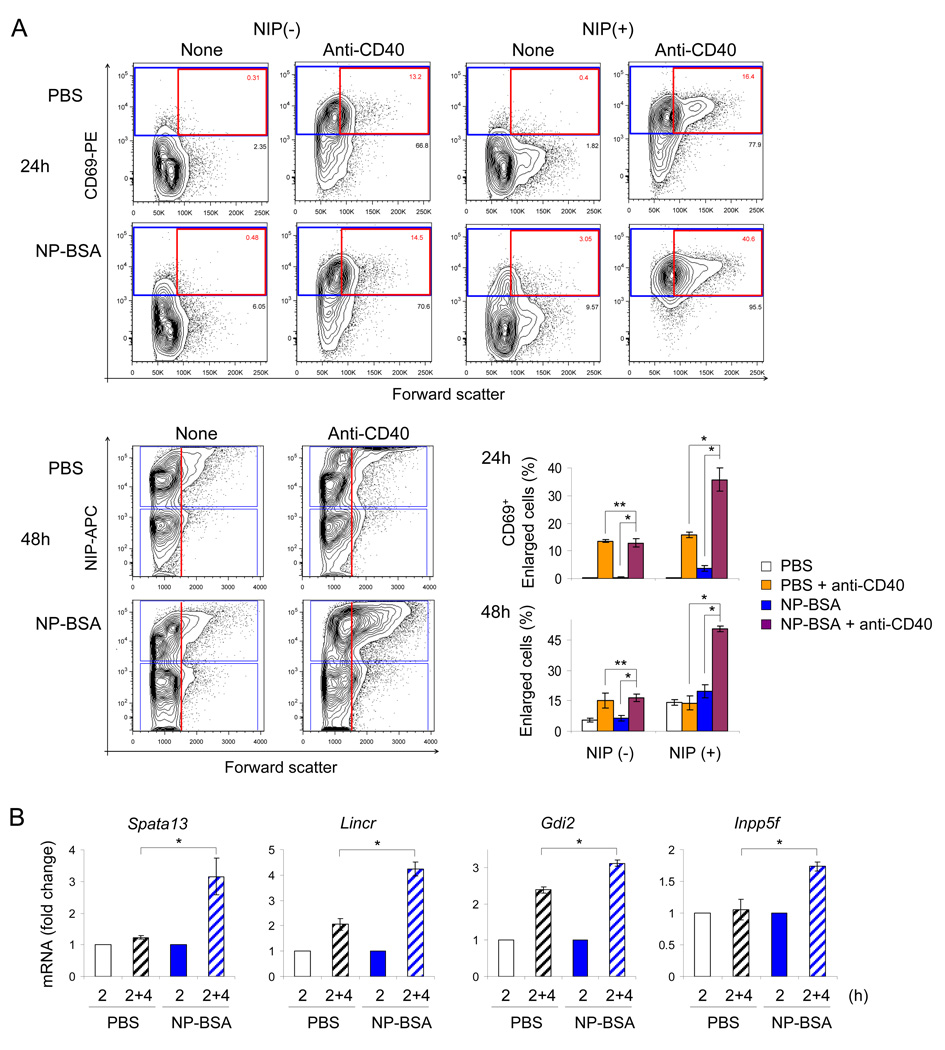

We extended our analysis to determine whether antigen-specific priming occurred in culture. For this we utilized mIgM-Tg mice which carry a Vh186.2 Ig heavy chain transgene that lacks secretory µ exons bred to a JH and Jκ-deficient background (Hannum et al., 2000). Approximately half the B cells (that express Vλ1) in this strain bind to the hapten NP. Compared to cells treated with anti-CD40 alone only antigen-specific B cells responded better after being primed with NP-BSA (see details in Fig. S5A–C). However, anti-IgM pulsing evoked comparable responses from NP-specific and non-specific B cells. We conclude that transient exposure to antigen enables B cells to respond more efficiently to subsequent CD40 activation.

Having ascertained that NP-specific B cells in mIgM-Tg mice could be primed ex vivo, we followed the scheme shown in Fig. S5D to test whether this occurred in vivo. Because mIgM-Tg mice lack secreted antigen-specific antibody, this strain permits direct exposure of B cells to defined amount of conjugated hapten in vivo. We injected mIgM-Tg mice intravenously with NP-BSA in PBS, or PBS alone; splenic B cells were isolated after 2h, incubated ex vivo for 4h to recapitulate the time duration between pulse activation and anti-CD40 treatment in the in vitro experiments, and then treated with anti-CD40. B cell activation was assessed by CD69 expression and cell size by flow cytometry.

At 24h anti-CD40 treatment induced CD69 expression on the majority of cells regardless of whether they were obtained from NP-BSA- or PBS-injected mice; this was true for antigen-specific (NIP(+)) and non-specific (NIP(−)) cells alike (Fig. 6A, top panels). However, the proportion of enlarged CD69+ cells with anti-CD40 was 2-fold higher only in the NIP-binding population in NP-BSA injected mice compared to PBS injected mice (Fig. 6A, averaged in top graph labeled 24h). Thus, 2h NP-BSA treatment in vivo selectively increased CD40 responsiveness of antigen-specific B cells. Because CD69 is considered an early activation marker, we used different gates to analyze the state of cells after 48h (Fig. 6A, bottom panels). Again we found that NP-BSA immunization selectively enhanced the response of antigen-specific B cells as judged by the proportion of enlarged cells; the difference between antigen-specific and non-specific cells in the same animal was readily apparent (Fig. 6A, averaged in bottom graph labeled 48h). Based on both assays we conclude that transient exposure to antigen in vivo heightens the response of B cells to subsequent CD40-initiated signals.

Fig. 6. In vivo B cell priming.

mIgM-Tg mice were injected intravenously with PBS alone (2 animals) or 250µg NP-BSA in PBS (3 animals), 2h later splenic B cells were isolated, incubated ex vivo for 4h, followed by anti-CD40 treatment. RT-PCR assays and flow cytometry analyses are performed at indicated time points (see experiment scheme in Fig. S5D).

A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of B cells at 24h (top panels) and 48h (bottom panels) after animal immunization and ex vivo culture with or without anti-CD40. Antigen-specific B cells were detected using fluoresceinated NIP ((4-hydroxy-3-nitro-2-iodophenyl)acetyl). For 24h analysis NIP(−) and NIP(+) alive B cells were further scored for CD69 expression and cell size by forward scatter. Cells that were not treated with anti-CD40 are marked ‘none’, and their origin from PBS-injected or NP-BSA-injected is indicated on the left. Gating for CD69+ cells is shown by the blue box and for enlarged cells by the red box. For 48h analysis cells were analyzed for antigen specificity (blue boxes) and cell size increase (red line). Graphs for the 24h or 48h time points show percent of enlarged, CD69+ cells (red box) or frequency of enlarged cells (falling to the right of the red line) among NIP-binding or not binding cells. Bar graphs represent the average ±SD between individual animals in each treatment arm. * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p>0.05 as determined by Mann-Whitney U test.

B) Induction of pulse anti-IgM specific genes. B cells were purified from spleen of NP-BSA or PBS injected mice 2h after immunization. RNA was isolated immediately after purification (labeled 2) or after 4 additional hours of culture in RPMI 1640 media (labeled 2+4) and assayed by qRT-PCR. The four genes were selected based on their inducibility at 9h after pulsed anti-IgM activation in vitro (Fig. S5E). The level of mRNA expression after 4h in vitro culture (hatched bars) was compared to freshly isolated cells from PBS-injected controls (white bars) or NP-BSA-injected animals (blue bars), with PCR assays being carried out in duplicates. Bars represent average ±SD within each group. * indicates p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney U test.

To obtain additional evidence of in vivo priming we sought a molecular read-out of pulse-versus continuous anti-IgM activation. From our microarray analyses we picked and confirmed several candidate genes that were selectively induced in pulse-activated cells (Fig. S5E). We then used RNA obtained from B cells of NP-BSA injected mice to evaluate antigen-induced activation of these genes. We found that all 4 genes were induced in response to transient NP-BSA exposure (Fig. 6B). The close correspondence between pulse-activated cells in vitro and transiently antigen-activated cells in vivo leads us to propose that short-term NP-BSA encounter induced several hallmarks of pulse-activation. Taken together with the functional evidence, we conclude that transient antigen exposure in vivo primes B cells to receive T cell help via CD40.

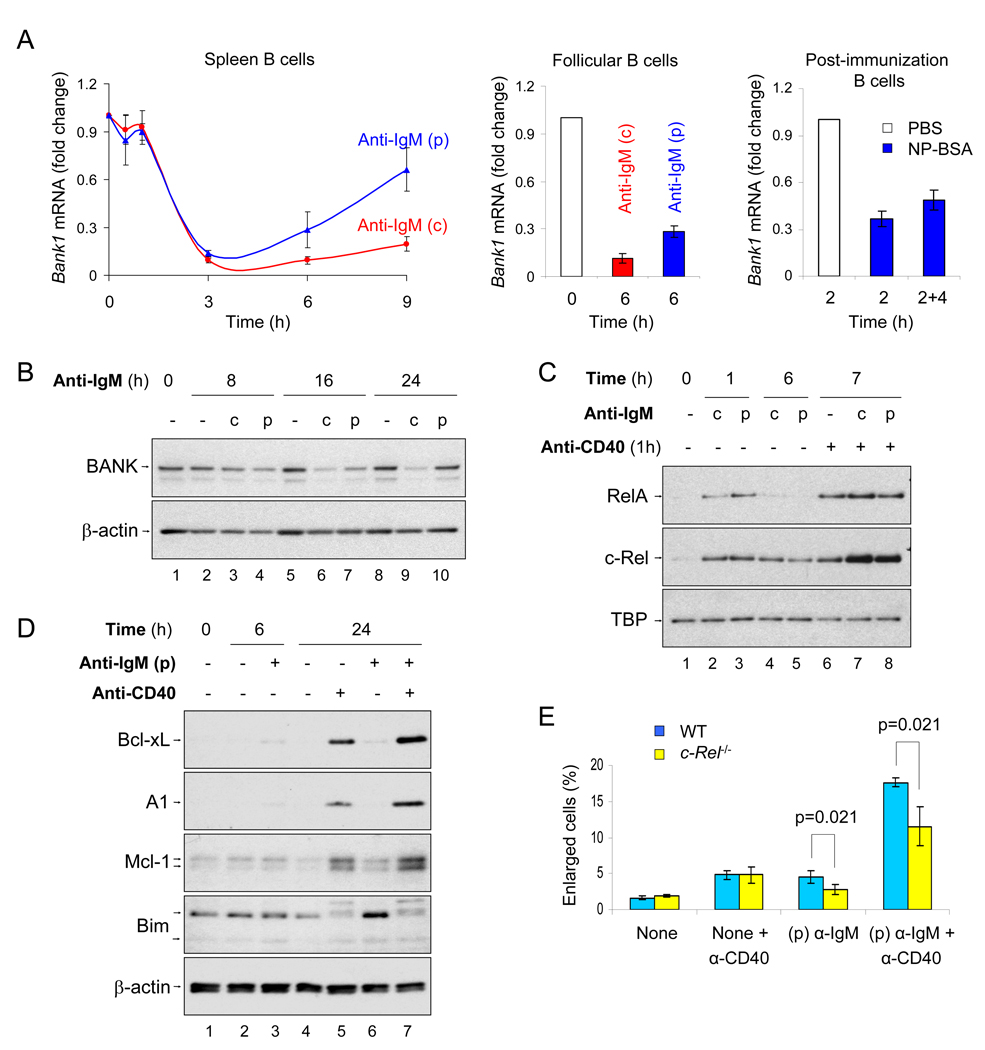

Mechanism of B cell priming

To identify possible mechanisms of increased CD40 responsiveness, we screened the microarray data for regulators of CD40 signaling. We found that mRNA of the gene encoding the B cell-specific adapter, BANK, a negative regulator of CD40 (Aiba et al., 2006), was reduced by 90% within 3h of pulsed- or continuous anti-IgM treatment; thereafter, the amounts remained low in continuously activated cells but gradually increased in pulse activated cells (Fig. 7A, left panel; see microarray data in Fig. S6A). Down-regulation of Bank1 mRNA also occurred in pulsed anti-IgM activated follicular mature B cells (Fig. 7A, middle panel) and in spleen B cells from NP-BSA immunized mIgM-Tg mice (Fig. 7A, right panel). To determine whether BANK protein expression was similarly affected by BCR cross-linking, we assayed whole cell extracts by immunoblotting with BANK antibody. BANK protein expression was reduced by both forms of BCR activation at the 8 and 16h time points (Fig. 7B, lanes 3, 4, 6 and 7; averaged in Fig. S6B), but re-accumulated only in pulse-activated cells at 24h (Fig. 7B, lanes 8–10). We suggest that reduced BANK expression in response to a single-round of BCR activation may contribute to enhanced CD40 responsiveness.

Fig. 7. Mediators of pulsed activation-induced CD40 hyper-responsiveness.

A) Down-regulation of Bank1 by pulsed-activation. Spleen B cells (left panel) or follicular B cells (middle panel) were activated by pulse (p) or continuous (c) anti-IgM stimulation. At various times after initiation of signaling, Bank1 mRNA expression was examined by qRT-PCR. The RNA data shown is the average ±SD of 3 independent RNA time-course experiments. Bank1 mRNA from antigen immunized mIgM-Tg mice was quantitated with RT-PCR (right panel). B cells purified from mIgM-Tg mice injected with PBS alone for 2h (labeled 2) or NP-BSA for 2h, and B cells from NP-BSA immunized animals that were cultured ex vivo for an additional 4h without stimulation (labeled 2+4). The data shown in the average ±SD of two PBS injected mice and three NP-BSA immunized mice.

B) BANK protein expression was examined in B cells left untreated (−) or after pulse (p) or continuous (c) anti-IgM activation. Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments (averaged in Fig. S6B).

C) Up-regulation of c-Rel by pulsed activation. Pulse (p)- or continuous (c) anti-IgM treatment was initiated at 0h; 6 hours later anti-CD40 was added for an additional 1h. NE were prepared at the indicated times from anti-IgM-treated cells or after the additional hour of anti-CD40 treatment as indicated. RelA and c-Rel nuclear induction was analyzed by immunoblotting. Data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments (averaged in Fig. S6C).

D) WCE were prepared 6h after pulse activation of spleen B cells with anti-IgM, as well as after further incubation for 18h in the presence or absence of anti-CD40 as indicated, and analyzed for pro- and anti-apoptotic protein expression. Data shown is representative of 2 independent experiments.

E) Untreated or pulsed anti-IgM - activated B cells from WT (C57BL/6J) and c-Rel-deficient mice were activated with anti-CD40 6h after administration of pulse. 12h after anti-CD40 addition the proportion of enlarged cells was quantitated by flow cytometry (see Fig. S1B). The average ±SD of 4 experiments is shown. P value was calculated by Mann-Whitney U test.

To test CD40-induced NF-κB responses in pulse-activated B cells, anti-CD40 was added 6h after pulse activation, and an hour later nuclear RelA and c-Rel were assayed by immunoblotting. Phase I RelA activation, that was evident at 1h in both continuous- and pulse-activated cells, was down-regulated by 6h (Fig. 7C, compare lanes 2, 3 to 4, 5); nuclear c-Rel levels decreased more slowly remaining higher than background at 6h (Fig. 7C, lanes 4, 5). 1h anti-CD40 treatment of control, continuous- and pulse-activated cells showed comparable RelA induction in all three samples but 2-fold enhanced c-Rel expression in anti-IgM-pre-treated cells (Fig. 7C, lanes 6–8 and averaged in Fig. S6C). Accordingly, expression of c-Rel-dependent anti-apoptotic gene products, such as Bcl-xL and A1 proteins, was also increased in response to CD40 treatment of pulse-activated cells (Fig. 7D).

To determine if c-Rel played a role in B cell priming, splenic B cells from c-Rel-deficient mice were pulse activated, treated with anti-CD40 and cell blasting was estimated by flow cytometry. CD40 activation led to fewer enlarged cells in BCR-primed B cells from c-Rel-deficient mice compared to normal mice (Fig. 7E). Importantly, this was not because c-Rel-deficient B cells responded less effectively to anti-CD40 because comparable blast formation was seen after extended times in normal un-primed or Rel−/− B cells (data not shown). We conclude that c-Rel contributes to priming naïve B cells to receive T cell help; this may occur, at least in part, via the induction of anti-apoptotic protein expression.

DISCUSSION

T-dependent humoral responses require interaction between relatively rare antigen-specific B and T cells. Moreover, subsequent T cell help is directed predominantly at antigen-specific B cells to minimize by-stander B cell activation (Parker, 1993). The molecular mechanisms that determine these critical aspects of B cell responses are not clear. Here we show that the shortest possible signal via the BCR pre-disposes B cells to participate in T-dependent responses by increasing the probability of encounter with CD4+ T cells, up-regulating MHC-II expression and inducing hyper-responsiveness to CD40 signaling. In vitro we delivered such a signal by binding anti-IgM, or NP-BSA, to spleen B cells at 4°C, removing excess unbound anti-IgM or antigen, and incubating the cells at 37°C. We based this scheme on the idea that receptors re-expressed after initial capping and endocytosis would no longer find antigen (or anti-IgM) in the extracellular milieu for continued binding and signaling. We substantiated these findings in vivo by exposing B cells in mIgM-Tg mice to a single dose of antigen in PBS, reasoning that such a protocol would deliver signals purely to B cells without confounding effects of adjuvant. Remarkably, this form of antigen exposure yielded B cells that had several characteristics of pulse-activated cells, including changes in gene expression and hyper-responsiveness to CD40 signaling. Hence, although the exact duration of antigen exposure to B cells in vivo is not known, it appears that a single dose of soluble antigen recapitulates a pulsed in vitro scheme better than a continuous one. These observations indicate that the proposed model of partial activation and priming is physiologically relevant in vivo.

This priming effect was transient, being maintained for 6h, but not 12h, after pulsed activation in vitro (data not shown). We propose that one mechanism by which pulsed-activation makes B cells hyper-responsive to CD40 is by rapidly down-regulating BANK, a negative regulator of CD40 signals. However, BANK down-regulation was not sufficient to prime B cells because BANK-deficient B cells were also primed by pulsed anti-IgM treatment in vitro (B.D., R.S., data not shown). Alternatively, BANK-deficient cells may have activated compensatory mechanisms to reduce CD40 responsiveness. Additional studies are needed to distinguish between these possibilities. Down-regulation of BANK by pulsed-activation was transient, and Bank1 mRNA expression was almost fully restored 9h after the pulse. The kinetics of BANK re-expression may, therefore, define the period a B cell remains in a state of heightened responsiveness to CD40. It is noteworthy that BANK amounts remained low in cells stimulated continuously with anti-IgM, suggesting that the duration of the primed state may vary with the kind of signal received by B cells.

Although many aspects of BCR signaling in pulse-activated cells were indistinguishable from the well-studied continuous forms of anti-IgM signaling, the form and duration of Akt activation was substantially different. In particular, we noticed that Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 continued to increase with conventional anti-IgM treatment over a 4h time course, whereas Thr308 phosphorylation decreased after 1h (though it remained discernibly higher than in pulse-activated cells). Ser473 phosphorylation has been recently shown to be mediated by the rictor-TORC2 complex (Jacinto et al., 2006); importantly, its absence results in the selective defect of FoxO1 and FoxO3a down-regulation and enhanced apoptosis of mouse embryo fibroblasts. It is therefore intriguing to speculate that continued increase of Ser473 phosphorylation in response to continuous anti-IgM treatment may be required to maintain B cell viability by down-regulating FoxO proteins. In pulse-activated B cells Ser473 phosphorylation is rapidly lost, which could explain the observd increase in cell death. Lack of persistent Akt activation may also contribute to absence of blast formation in pulse-activated cells by affecting GLUT1 expression (Dufort et al., 2007).

Taken together our observations lead to the following working model for initiation of T-dependent immune responses. A single-round of antigen binding and uptake by BCR initiates long-term changes directed towards effective B-T collaboration. First, MHC-II molecules are up-regulated to allow antigenic peptides to be presented to T cells. Second, phase I NF-κB induces target genes such as the chemokine receptor CCR7 that enables antigen-bearing B cells to move into splenic T-rich zone; concurrently CCL3 and CCL4 chemokine expression serves to attract CD4+ T cells to the antigen-primed B cells (Bystry et al., 2001; Okada and Cyster, 2006; Reif et al., 2002). Together, these changes in chemokines and their receptors increase the chance of antigen-primed B cells encountering CD4+ T cells of the right specificity. Third, if an appropriate T cell is found, its activation via peptide-MHC-II results in expression of CD40 ligand. Because antigen-primed B cells are particularly responsive to receive CD40 signals, having down-regulated BANK and up-regulated c-Rel, CD40 ligand-bearing T cell help is directed selectively towards these cells. Thereby, by-stander B cell activation is reduced. Our studies also suggest that the primed state is transient. At the molecular level priming is lost when chemokines and chemokine receptors are down-regulated, and/or BANK is up-regulated, after cessation of BCR signaling. Cumulatively, these mechanisms minimize activation in response to sporadic BCR stimulation while maximizing the possibility of T-dependent B cell activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice and antigen administration

All experimental mice were 8–12 weeks old. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Rel−/− mice were provided by the laboratory of Dr. Hsiou-Chi Liou (Cornell University Medical College). mIgM-Tg mice carrying the Vh186.2 Ig heavy chain bred to Jκ-deficient mice has been previously described (Hannum et al., 2000) were injected with PBS or NP-BSA (250µg/animal, with conjugation ratio of NP to BSA of 26) into tail vein and 2h later the mice were euthanized for B cell purification.

Mice were treated humanely in accordance with federal government guidelines and their use was approved by the respective institutional animal care and use committees.

B cell isolation and culture

Primary B lymphocytes were isolated using Auto-MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) or RoboSep (StemCell Technologies) magnetic purification techniques by negative selection. B cell purity was 90–95% based on flow cytometric analysis with CD19 staining. Isolated B cell pools contained in average 57.1±9.1% of follicular, 9.1±3.4% of marginal, 5.2±2.4% of T1 and 6.4±3.4% of T2 B cells.

Follicular B cells were purified from negatively isolated spleen B cells by flow cytometry (FACSAria, Beckton Dickinson) using published gating strategy (Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2009). Representative sorting gates and follicular B cell purity (90%) are shown in Fig. S4D.

Purified B cells (2×106/ml) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 55nM β-mercaptoethanol, 2mM L-glutamine and 100IU penicillin and 100µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C.

For pulsed anti-IgM treatment experiments, B cells were incubated with 10µg/ml goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab’)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at 4°C for 30 min. Unbound anti-IgM was removed from the medium by washing and centrifuging the cells at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in chilled complete medium and shifted to 37°C by placing in an incubator or in water-bath. For continuous anti-IgM treatment experiments, B cells were stimulated with 10µg/ml anti-IgM at 4°C for 30 min, then incubated at 37°C. For “priming” experiments, pulse- or continuously activated B cells were incubated for 6h after which 5µg/ml monoclonal anti-CD40 (BD Pharmigen) was added and the cells further incubated for various time periods depending on the assay.

Immunoblotting

For analysis of NF-κB components, 3µg nuclear extracts prepared as described (Stadanlick et al., 2008) were separated by SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes using semi-dry transfer and the membrane probed with anti-p65 (RelA), -c-Rel antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) substrate (Thermo Scientific). TATA binding protein (Abcam) was used to normalize between nuclear extracts.

For all other immunoblottings 10µg whole-cell extracts prepared in RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz) were used. Antibodies detecting phospho-Syk (Y319), Syk, phospho-ERK1, 2 (T202/Y204), ERK1, 2, phospho-p38 (T180/182), p38, phospho-Akt (S473), phospho-Akt (T308), Akt, Bcl-xL, Bax, p27, phospho-Rb (S807/811), IκBα, IκBβ (Cell Signaling), Cdk2, Cdk4, Cyclin D2, Cyclin E, PKCμ (Santa Cruz), A1 (R&D Systems), Mcl-1 (Rockland Immunochemicals), Bim (BD Biosciences), Bcl-2 (Stressgen), and β-actin (Sigma) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. BANK antibody was gift from Dr. Tomohiro Kurosaki (RIKEN Research Center for Allergy and Immunology, Japan). ImageJ software (NIH) was used to quantitate band intensities from un-saturated films.

RNA extraction and Real-Time PCR

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and the SuperScript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed in duplicates using the ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems). Expression of Ccl3, Ccl4, Ccr7, Bank1, Spata13, Lincr, Gdi2, and Inpp5f mRNA was normalized to Actin mRNA on same PCR plate. The primers used in this study were designed using PrimerQuest online tool (Integrated DNA Technologies). Primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Experimental Procedure.

Flow cytometry

Cell viability was measured by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide (10µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich). Cell size was estimated based on forward scatter profile of viable cells (Fig. S1A).

CCR7, MHC-II, CD69 and NP specific Ig cell surface staining was done using rat CD197-FITC (AbD Serotec), mouse I-Ab, CD69-PE antibodies (BD Pharmingen) and NIP-haptenated PE (NIP-PE), and APC (NIP-APC) reagents, and rat or mouse IgG2a antibodies with corresponding fluorophore (BD Pharmingen), as isotype control. Briefly, cells were incubated with Fc block and then stained for 30 min with the antibodies in flow cytometry buffer (0.5% BSA in PBS), followed by washing in excess amount of the buffer.

All measurements from in vitro experiments were carried out using a FACSCalibur and from in vivo experiments were performed using an LSR II (Beckton Dickinson) and data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

ELISA

Detection of CCL3 and 4 in culture medium was done using DuoSet ELISA Development kits for mouse CCL3 (MIP-1α) and CCL4 (MIP-1β) (R&D Systems) according supplier’s protocol. Briefly, 96-well flat-bottomed plates were coated with 0.4µg/ml or 2µg/ml capture antibodies, respectively for CCL3 and CCL4. The captured CCL proteins were detected with 0.1µg/ml of the appropriate biotinylated goat anti-mouse CCL and streptavidin-HRP.

Illumina Oligonucleotide microarray

Total RNA (0.5g) was used to generate biotin labeled single-stranded RNA using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Briefly, total RNA was converted into single-stranded cDNA with reverse transcriptase using an oligo-dT primer containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter site and then copied to produce double-stranded cDNA molecules. The double stranded cDNA was used in an overnight in vitro transcription reaction where single-stranded RNA (cRNA) was generated and labeled by incorporation of biotin-16-UTP. A total of 0.75µg of biotin-labels cRNA was hybridized at 58°C for 16h to Illumina's Sentrix MouseRef-8 Expression BeadChips (Illumina). The arrays were washed, blocked and the labeled cRNA was detected by staining with streptaviden-Cy3. The arrays were scanned using an Illumina BeadStation 500X Genetic Analysis Systems scanner and the image data extracted using Illumina BeadStudio software.

Microarray analysis

Microarray data was analyzed using DIANE 6.0 program. Raw microarray data were subjected to filtering and Z normalization and tested for significant changes as previously described (Cheadle et al., 2003). Individual genes with Z ratios >1.5, p value <0.05 and fdr <0.3 were considered significantly changed. Ingenuity Systems Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity Systems) was used to identify top network functions involving differentially expressed genes. The data set has been deposited in GEO (accession number …).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Kokkonen for sorting of follicular B cells, Drs. T. Kurosaki and Y. Aiba for providing reagents, Drs. J. Cerny, A. Roy, S. Gerondakis, D. Parker, P. Gearhart, S. Fugmann and R. Wersto for comments on the manuscript, and V. Martin for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, and by NIH grant R01-AI43603 to MJS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aiba Y, Yamazaki T, Okada T, Gotoh K, Sanjo H, Ogata M, Kurosaki T. BANK negatively regulates Akt activation and subsequent B cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomen VA, Boonstra J. Cell fate determination during G1 phase progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:3084–3104. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystry RS, Aluvihare V, Welch KA, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. B cells and professional APCs recruit regulatory T cells via CCL4. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1126–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle C, Vawter MP, Freed WJ, Becker KG. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alboran IM, O'Hagan RC, Gartner F, Malynn B, Davidson L, Rickert R, Rajewsky K, DePinho RA, Alt FW. Analysis of C-MYC function in normal cells via conditional gene-targeted mutation. Immunity. 2001;14:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFranco AL, Raveche ES, Paul WE. Separate control of B lymphocyte early activation and proliferation in response to anti-IgM antibodies. J Immunol. 1985;135:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufort FJ, Bleiman BF, Gumina MR, Blair D, Wagner DJ, Roberts MF, Abu-Amer Y, Chiles TC. Cutting edge: IL-4-mediated protection of primary B lymphocytes from apoptosis via Stat6-dependent regulation of glycolytic metabolism. J Immunol. 2007;179:4953–4957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyao MP, Buckler AJ, Sonenshein GE. Interaction of an NF-kappa B-like factor with a site upstream of the c-myc promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4727–4731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini M, Corte G, Viale G, Durante ML, Bargellesi A. Membrane Ig on human lymphocytes: rate of turnover of IgD and IgM on the surface of human tonsil cells. Eur J Immunol. 1976;6:372–378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazumyan A, Reichlin A, Nussenzweig MC. Ig beta tyrosine residues contribute to the control of B cell receptor signaling by regulating receptor internalization. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1785–1794. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. Germinal center initiation, variable gene region hypermutation, and mutant B cell selection without detectable immune complexes on follicular dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:931–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood NE, Batista FD. New insights into the early molecular events underlying B cell activation. Immunity. 2008;28:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus M, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky N, Rajewsky K. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/beta heterodimer. Cell. 2004;117:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T, Shinohara H, Baba Y. B Cell Signaling and Fate Decision. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HH, Dadgostar H, Cheng Q, Shu J, Cheng G. NF-kappaB-mediated up-regulation of Bcl-x and Bfl-1/A1 is required for CD40 survival signaling in B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9136–9141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Clarke S, Tasker L, Heaton MP, Parkhouse RM. A differential requirement for phosphoinositide 3-kinase reveals two pathways for inducible upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and CD86 expression by murine B lymphocytes. Immunology. 2003;109:102–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Bahlburg A, Bandaranayake AD, Andrews SF, Rawlings DJ. Reduced c-myc expression levels limit follicular mature B cell cycling in response to TLR signals. J Immunol. 2009;182:4065–4075. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiro H, Clark EA. Regulation of B-cell fate by antigen-receptor signals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:945–956. doi: 10.1038/nri955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiro H, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Clark EA. The B lymphocyte adaptor molecule of 32 kD (Bam32) regulates B cell antigen receptor signaling and cell survival. J Exp Med. 2002;195:143–149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Cyster JG. B cell migration and interactions in the early phase of antibody responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker DC. T cell-dependent B cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:331–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatelli MJ, Tanguay D, Rothstein TL, Chiles TC. Cell cycle control mechanisms in B-1 and B-2 lymphoid subsets. Immunol Res. 2003;27:31–52. doi: 10.1385/IR:27:1:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proust JJ, Chrest FJ, Buchholz MA, Nordin AA. G0 B cells activated by anti-mu acquire the ability to proliferate in response to B cell-activating factors independently from entry into G1 phase. J Immunol. 1985;135:3056–3061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif K, Ekland EH, Ohl L, Nakano H, Lipp M, Forster R, Cyster JG. Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature. 2002;416:94–99. doi: 10.1038/416094a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Kurosaki T. Genetic analysis of B cell signaling. Subcell Biochem. 2006;40:145–187. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-4896-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeiro I, Mohamedali A, Romanska HM, Lea NC, Child ES, Glassford J, Orr SJ, Roberts C, Naresh KN, Lalani el N, et al. p27Kip1 and p130 cooperate to regulate hematopoietic cell proliferation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6170–6184. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02182-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan L, Sasaki Y, Calado DP, Zhang B, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Kutok JL, Kearney JF, Otipoby KL, Rajewsky K. PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell. 2009;139:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadanlick JE, Kaileh M, Karnell FG, Scholz JL, Miller JP, Quinn WJ, 3rd, Brezski RJ, Treml LS, Jordan KA, Monroe JG, et al. Tonic B cell antigen receptor signals supply an NF-kappaB substrate for prosurvival BLyS signaling. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1379–1387. doi: 10.1038/ni.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub DD, Conlon K, Lloyd AR, Oppenheim JJ, Kelvin DJ. Preferential migration of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta. Science. 1993;260:355–358. doi: 10.1126/science.7682337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.